Volume 40 Number 2

Skin manifestations with COVID-19: the purple skin and toes that you are seeing may not be deep tissue pressure injury

Joyce Black and Joyce Cuddigan

Keywords COVID-19, purple skin, deep tissue pressure injury

For referencing Black J and Cuddigan J. Skin manifestations with COVID-19: the purple skin and toes that you are seeing may not be deep tissue pressure injury. WCET® Journal 2020;40(2):18-21

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.2.18-21

Abstract

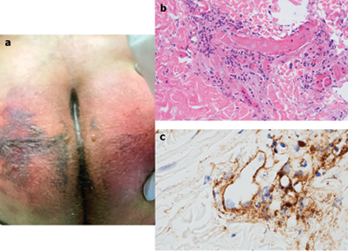

Many reports are occurring concerning areas of purpuric/purple skin and purple toe lesions in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) (Figure 1). Wound care providers are being asked if these skin lesions are forms of Deep Tissue Pressure Injury and/or “skin failure”. Early reports of COVID-19 related skin changes included rashes, acral areas of erythema with vesicles or pustules (pseudo-chilblain), other vesicular eruptions, urticarial lesions, maculopapular eruptions, and livedo or necrosis.1-4 The pattern and presentation of skin manifestations with COVID-19 is more than rashes. The purpose of this paper is to guide the wound care clinician in determining if the “purple skin” being seen is a deep tissue pressure injury or a cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19.

Background

The true incidence of COVID-19 related skin injury is unknown at this time; however, NPIAP board members practicing in COVID-19 hotspots and others who are submitting inquiries to the NPIAP Website are reporting purple discoloration of the skin and soft tissue not exposed to pressure. One form is being referred to as a novel phenomenon called “COVID toes” (i.e. deep red or purple appearance of the toes). Clinicians are requesting guidance from NPIAP regarding the differential diagnosis of these injuries from pressure injuries.

Literature Review

Acute respiratory failure and a systemic coagulopathy are critical aspects of the morbidity and mortality seen with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome-associated with coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2).5 Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, it appeared that the primary risk of death from the disease was severe pneumonia followed by a cytokine storm. While much of the pathogenesis of the corona viruses is unknown, there are increasing cases of complications due to hypercoagulation and microvascular occlusion including stroke and pulmonary embolism.6-7 This accelerated clotting process appears to also involve the skin.

COVID-19 enters cells via the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors, which are broadly expressed in vascular endothelium, respiratory epithelium, alveolar monocytes, and macrophages.8 Later in the disease course, COVID-19 replicates in the lower respiratory tract, and generates a secondary viremia, followed by extensive attack against target organs that express ACE2, such as the heart, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, and vast distal vasculature. This process of viral spreading correlates with the clinical deterioration, mainly taking place around the second week following disease onset.

Magro and colleagues5 reported on five cases with an exceptionally high proportion of aberrant coagulation in severe cases of critically ill adult patients with COVID-19. Their COVID-19 patients exhibited a hypercoagulable state, featuring prolonged prothrombin time, elevated levels of D-dimer and fibrinogen, and near normal activated partial thromboplastin time. Two patients progressed to overt disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). DIC has been described before; Tang et al.9 reported that 71.4% of non-survivors and 0.6% of survivors of COVID-19 showed evidence of overt DIC.

Figure 1 right buttock on day 1

Figure 1 right buttock, sacrum and coccyx on day 3. Photos used with permission of Beaumont Health, Royal Oak MI

Two of the cases with biopsy results from Magro’s5 work are presented here with permission of the author and publisher. They examined skin and lung tissues from five patients with severe COVID-19 characterised by respiratory failure (n=5) and purpuric skin rash (n=3). The purpuric skin lesions showed a pauci-inflammatory thrombogenic vasculopathy, with deposition of Complement 5b-9 and Complement 4d in both grossly involved and normally appearing skin. A pattern of tissue damage consistent with complement-mediated microvascular injury was noted in the lung and/or skin of the five individuals with severe COVID-19. One of the three patients with skin change had a lacey, livedoid rash on the lower extremities; it is not included in this paper.

Cases

Case 1

A 32-year-old male with a medical history of obesity-associated sleep apnea and anabolic steroid use, currently taking testosterone, presented with a 1-week history of fever and cough. He became progressively more dyspneic with fevers to 40°C, ultimately becoming ventilator dependent from acute respiratory failure. Chest x-ray showed bilateral airspace opacities. He had an elevated d-dimer of 1024ng/ml (normal range 0-229) on presentation, which peaked at 2090ng/ml on hospital day 19, and a persistently elevated INR of 1.6-1.9, but a normal PTT and platelet count. Serum complement levels were elevated for CH50 at 177 CAE Units (normal range 60-144), C4 of 42.6 mg/dL (normal range 12-36), and high normal range for C3 at 178 mg/dL (normal range 90-180 mg/dL). Over this patient’s continuing three-plus weeks on ventilator support he completed courses of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, followed by the experimental anti-CoV agent remdesivir (5mg/kg IV daily for 10 days).

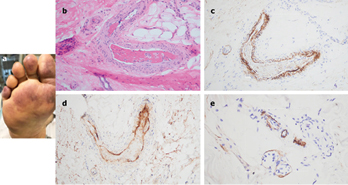

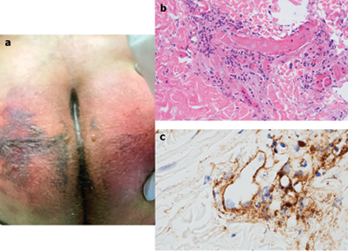

After only four days on ventilator support, retiform purpura with extensive surrounding inflammation was noted on his buttocks (Fig. 2 A). Skin biopsy showed a striking thrombogenic vasculopathy accompanied by extensive necrosis of the epidermis and adnexal structures, including the eccrine coil (Fig 2b). There was a significant degree of interstitial and perivascular neutrophilia with prominent leukocytoclasia. IHC showed striking and extensive deposition of C5b-9 within the microvasculature (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2

Case 2

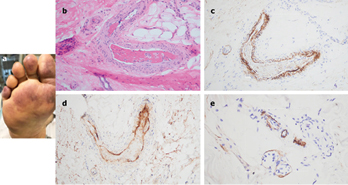

A 66-year-old female, with no significant past medical history, was brought to the ED after nine days of fever, cough, diarrhea, and chest pain. She was hypoxemic, with diffuse bilateral patchy airspace opacities, without effusions, on chest x-ray. She was admitted and treated with hydroxychloroquine and prophylactic anticoagulation with enoxaparin. Three days later she became confused, increasingly hypoxemic with rising serum creatinine levels and was intubated. Renal replacement was initiated. On hospital day 10, thrombocytopenia (platelets 128 × 109/L) and a markedly elevated d-dimer of 7030ng/ml, but normal INR and PTT, were noted. The next day dusky purpuric patches appeared on her palms and soles bilaterally (Fig. 3 A). A skin biopsy of one lesion showed superficial vascular ectasia and an occlusive arterial thrombus within the deeper reticular dermis in the absence of inflammation (Fig. 3B). Extensive vascular deposits of C5b-9 (Fig. 3C), C3d, and C4d (Fig. 3D) were observed throughout the dermis, with marked deposition in an occluded artery. A biopsy of normal-appearing deltoid skin also showed conspicuous microvascular deposits of C5b-9 (Fig. 3E). Sedative infusions were discontinued that day, unmasking a comatose state. Computerised tomographic imaging of the head revealed multifocal supra- and infra-tentorial infarctions, with complete infarction of the area supplied by the left middle cerebral artery.

Figure 3

The skin lesions have multiple appearances and patterns associated with microvascular occlusion of vessels in the skin. Some skin lesions can appear with a livedoid or lace-like pattern most commonly on the extremities and others can be more purpuric in nature. Rarely, patients have the appearance of purpura fulminans and frank necrosis or skin infarct. Purpura fulminans is a rare but life-threatening disorder, characterised by hemorrhagic infarction of the skin caused by disseminated intravascular coagulation and dermal vascular thrombosis. This disturbance has traditionally been cited to develop from bacterial endotoxin (typically meningococcus) and mediated by various factors, including the inflammatory cytokines interleukins, interferon and tumor necrosis factor-alpha and consumption of natural anticoagulants. Purpura fulminans has more than 50% mortality from multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.10

From the data available now, at least a subset of sustained, severe COVID-19 may define a type of catastrophic microvascular injury syndrome mediated by activation of complement pathways and an associated procoagulant state.

Clinical guidance for differentiating these injuries from pressure injuries

Purple areas on non-pressure loaded surfaces lack a pressure-shear etiology and should not be classified as pressure injuries. They may resemble purpura fulminans which is consistent with the histopathology noted above and has been reported in other systemic infections. They may also resemble other dermatological conditions associated with microvascular injury and thrombosis such as retiform purpura, livedo reticularis and cutaneous vasculitis.

Purple areas on pressure loaded surfaces (whether prone or supine) require further investigation. Deeper soft tissue may also be damaged because of pressure-shear, particularly in the buttocks, sacrum and coccyx when positioned supine or on the face, knees, and other high-risk body parts when positioned prone. We would recommend that discolored areas on any body surface subjected to pressure loading or shear be palpated to detect differences in tissue consistency and temperature to rule out concomitant deep tissue pressure injury. Theoretically, the same COVID-19 related vascular changes may be occurring in underlying soft tissue (e.g., muscle), rendering those tissues less tolerant of the damaging effects of pressure and shear. The histological specimens presented in the above case studies show clotting. Histological specimens of deep tissue pressure injuries showed frank necrosis of skin, fat, and muscle.11 The histological appearance of Deep Tissue Pressure Injury (DTPI) is not the same as the COVID-19 skin changes.

COVID toes: A deep red appearance may be due to vascular inflammation. A deep purple appearance may be indicative of microthrombi. Patients receiving vasopressors may also develop purple toes; however this is a result of vasoconstriction and ischemia. In the absence of pressure and/or shear, these injuries should not be diagnosed as pressure injuries.

Summary

The purpuric or non-blanchable purple skin lesions seen with COVID-19 are not consistent with DTPI, because they lack pressure induced injury to underlying soft tissue cells and the skin changes likely represent tissue ischemia due to clotting. High risk patients who have been immobile, hypotensive, and hypoxic are at high risk for developing deep tissue pressure injury, however these pressure injuries would be seen on pressure bearing skin and soft tissue. While the term, purpura fulminans, may be correct, other terms have been proposed for this phenomena such as retiform purpura, livedo reticularis and cutaneous vasculitis. Further study is required before the pathophysiologic link of COVID-19 to purpura and other cutaneous manifestations can be fully elucidated. After confirming that the skin change is not due to pressure, wound care providers should not label these skin changes as DTPI, but rather potential skin manifestations from COVID-19.

Research continues to evolve on the entire disease state of COVID-19. Wound care clinicians can aid in the completeness of these investigations by bringing the changes in the skin to the attention of those researchers to understand the pathophysiology. Treatments of these skin-related conditions have also to date not been investigated. In order to enhance our understanding of COVID-19 skin manifestations, consider submitting case reports to the American Academy of Dermatology COVID-19 Dermatology Registry at https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coronavirus/registry.12

This NPIAP White Paper is intended for wide public distribution. Please share with your contacts who may benefit from this information. This content (unless otherwise specified) is copyrighted to the NPIAP

Acknowledgements

The NPIAP gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following individuals.

Authors: Dr Joyce Black, University of Nebraska Medical Center; Dr. Janet Cuddigan, University of Nebraska Medical Center on behalf of the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Reviewers

This White Paper was reviewed by the NPIAP Board of Directors. Feedback on content was provided by Dr Virginia Capasso, Massachusetts General Hospital; Dr Jill Cox, Rutgers University; Dr Barbara Delmore, NYU Langone Health; Dr William Padula, The Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics, University of Southern California; Dr Joyce Pittman, University of Southern Alabama; Dr Lee Ruotsi, Saratoga Hospital Medical Group – Wound Healing; Dr Sharon Sonenblum, Georgia Institute of Technology; and Dr Ann Tescher, Mayo Clinic.

Consultation and guidance

NPIAP appreciates the guidance provided by Dr Ashley Wysong Chairman of the Department of Dermatology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center and Dr Laura Edsberg, Director of the Center for Wound Healing Research at Daemen College in Amherst NY.

Case studies and figures

Figures 2 and 3 used with permission of Dr Jeffrey Laurence of Cornell University. Elsevier, the publisher, grants permission to make all its COVID-19-related research that is available on the COVID-19 resource centre - rights for unrestricted research re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source.

Photos in Figure 1 were used with permission of Beaumont Health, Royal Oak MI.

COVID-19的皮肤表现:肉眼可见的紫色皮肤和脚趾可能不是深部组织压力性损伤

Joyce Black and Joyce Cuddigan

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.2.18-21

摘要

目前许多报告涉及COVID-19(SARS-CoV-2)确诊患者的紫癜样/紫色皮肤和紫色脚趾病变区域(图1)。伤口护理人员遇到这样的询问:这些皮损是否是深部组织压力性损伤和/或“皮肤衰竭”的形式。COVID-19相关皮肤改变的早期报告包括皮疹、肢端红斑区伴水疱或脓疱(假性冻疮)、其他小疱疹、荨麻疹病变、斑丘疹和青斑或坏死。1-4 COVID-19皮肤表现的模式和症状不仅仅是皮疹。本文旨在指导伤口护理临床医生确定观察到的“紫色皮肤”是深部组织压力性损伤还是COVID-19的皮肤表现。

背景

COVID-19相关皮肤损伤的真实发生率目前尚不清楚;然而,在COVID-19热点地区执业的NPIAP董事会成员和向NPIAP网站提交咨询的其他人员报告了皮肤和软组织在没有受到压力的情况下出现的变紫表现。其中一种是被称为“COVID脚趾”(即脚趾呈深红色或紫色)的新现象。临床医生正在向NPIAP寻求关于鉴别诊断这类损伤与压力性损伤的指导。

文献综述

急性呼吸衰竭和全身性凝血障碍是冠状病毒2(SARS-CoV-2)相关性严重急性呼吸窘迫综合征的发病率和死亡率的关键方面。5在COVID-19大流行的早期,因疾病而死亡的主要风险似乎是重症肺炎,其次是细胞因子风暴。虽然有关冠状病毒发病机制的很多信息尚不清楚,但由于血液高凝状态和微血管闭塞(包括脑卒中和肺栓塞)导致的并发症病例越来越多。6-7 这种加速凝血过程似乎也累及皮肤。

COVID-19通过血管紧张素转换酶2(ACE2)受体进入细胞,该受体广泛表达于血管内皮素、呼吸道上皮、肺泡单核细胞和巨噬细胞。8 病程后期,COVID-19在下呼吸道复制,并产生继发性病毒血症,随后广泛攻击表达ACE2的靶器官,如心脏、肾脏、胃肠道和广阔的远端血管。这种病毒传播过程与临床恶化有关,主要发生在发病后第二周左右。

Magro及其同事们5报告了COVID-19危重症成人患者重症病例中5例异常凝血比例尤其高的病例。他们的COVID-19患者表现出血液高凝状态,特点为凝血酶原时间延长,D-二聚体和纤维蛋白原水平升高,活化部分凝血活酶时间接近正常。2例患者进展为显性弥散性血管内凝血(DIC)。之前也有过DIC的说明;Tang等人9报道,71.4%的COVID-19非存活者和0.6%的COVID-19存活者表现出显性DIC症状。

图1 右侧臀部,第1天

图1 右侧臀部、骶骨和尾骨,第3天。照片使用经Beaumont Health(美国密歇根州罗亚尔奥克)的许可

在获得作者和出版商许可的情况下,本文介绍了Magro5研究中拥有活检结果的两个病例。他们检查了5例表现为呼吸衰竭(n=5)和紫癜样皮疹(n=3)的重症COVID-19患者的皮肤和肺组织。紫癜样皮损表现为少炎性血栓形成性血管病变,在严重受累和正常外观的皮肤中均有补体5b-9和补体4d沉积。在5例重症COVID-19患者的肺和/或皮肤中均观察到与补体介导的微血管损伤一致的组织损伤模式。3例发生皮肤改变的患者中,1例下肢出现带有花边的青斑样皮疹;本文未纳入。

病例

病例1

1例32岁男性患者,有肥胖相关性睡眠呼吸暂停病史和合成代谢类固醇用药史,目前正在服用睾酮,表现为持续1周的发热和咳嗽病史。患者进展为呼吸困难恶化,发热至40°C,最终因急性呼吸衰竭依赖呼吸机通气。胸部x线检查显示双侧气腔混浊。患者就诊时d-二聚体水平升高,达到1024 ng/ml(正常范围:0-229),住院第19天达到峰值2090 ng/ml,国际标准化比值(INR)持续升高,达到1.6-1.9,但部分凝血活酶时间(PTT)和血小板计数正常。血清补体水平升高,CH50为177 CAE单位(正常范围:60-144),C4为42.6 mg/dL(正常范围:12-36),C3水平达到正常范围的高值,为178 mg/dL (正常范围:90-180 mg/dL)。在该患者继续接受3周以上的呼吸机支持期间,他完成了羟氯喹和阿奇霉素疗程,随后接受抗CoV试验药物瑞德西韦(每日静脉注射5 mg/kg,持续10天)。

接受呼吸机支持仅四天后,在其臀部观察到网状紫癜伴广泛性周围炎症(图2A)。皮肤活检显示明显的血栓形成性血管病变,伴有表皮和附件结构(包括小汗腺曲管)广泛性坏死(图2b)。存在程度明显的间质和血管周围中性粒细胞增多,伴显著的白细胞碎裂。IHC显示C5b-9在微血管内惊人的广泛沉积(图2C)。

图2

病例2

一例66岁女性患者,无重大的既往病史,在发热、咳嗽、腹泻和胸痛9天后被送往急诊室。她患有低氧血症,胸部x线检查显示双侧弥漫性斑片状气腔阴影,无积液。她入院并接受羟氯喹和依诺肝素预防性抗凝治疗。3天后,患者出现意识模糊、低氧血症加重伴血清肌酐水平升高,并接受插管。随后开始肾脏替代治疗。住院第10天,观察到血小板减少

(血小板计数:128×109/L)和d-二聚体水平明显升高,达到 7030 ng/ml,但INR和PTT正常。次日双侧掌跖出现暗紫癜样斑片(图3A)。1处皮损的皮肤活检示:浅表血管扩张,深部真皮网状层内可见闭塞性动脉血栓,无炎症(图3B)。整个真皮中观察到C5b-9(图3C)、C3d、C4d(图3D)的广泛血管内沉积,在闭塞的动脉中明显沉积。外观正常的三角肌皮肤活检也显示明显的C5b-9微血管沉积(图3E)。患者当天停止镇静剂输注,暴露昏迷状态。头部计算机断层扫描成像显示多发性幕上和幕下梗死,左侧大脑中动脉供血区域完全梗死。

图3

皮损有多种与皮肤血管中微血管闭塞有关的外观表现和模式。一些皮损可表现为青斑样或花边样形态,最常见于四肢,另一些则可能更偏向紫癜性。罕见情况下,患者表现为暴发性紫癜和明显坏死或皮肤梗死。暴发性紫癜是一种罕见但危及生命的疾病,其特点为弥散性血管内凝血和真皮血管血栓形成引起的皮肤出血性梗死。传统上认为这种疾病是由细菌内毒素(通常是脑膜炎球菌)引起的,并由各种因子介导,包括炎性细胞因子白细胞介素、干扰素和肿瘤坏死因子α,以及天然抗凝剂的消耗。暴发性紫癜因多器官功能障碍综合征导致的死亡率超过50%。10

从当前的可用数据来看,至少有一部分持续的重症COVID-19可定义为一种由补体通路激活和相关促凝血状态介导的灾难性微血管损伤综合征。

鉴别这些损伤与压力性损伤的临床指导

无压力负荷的表面上出现的紫色区域缺乏压力-剪切力病因,不应归类为压力性损伤。这些紫色区域可能类似于暴发性紫癜,这与上述组织病理学结果一致,并已在其他全身性感染中报告。它们也可能类似于与微血管损伤和血栓形成相关的其他皮肤病,如网状紫癜、网状青斑和皮肤血管炎。

压力负荷表面上出现的紫色区域(俯卧或仰卧位)需要进一步研究。更深部的软组织也可能因为压力-剪切力而受到损伤,特别是仰卧位时的臀部、骶骨和尾骨,或俯卧位时的面部、膝关节和其他高危身体部位。我们建议对承受压力负荷或剪切力的所有体表变色区域进行触诊,以检测组织一致性和温度的差异,从而排除伴随的深部组织压力性损伤。理论上,相同的COVID-19相关血管改变可能会发生在底层软组织(例如肌肉)中,使得这些组织对压力和剪切力损伤作用的耐受性降低。上述病例研究中的组织学标本显示存在凝血。深部组织压力性损伤的组织学标本则显示皮肤、脂肪和肌肉明显坏死。11 深部组织压力性损伤(DTPI)的组织学表现与COVID-19相关皮肤改变不尽相同。

COVID脚趾:深红色外观可能是由于血管炎症所致。深紫色外观可能表明存在微血栓。接受血管加压药的患者也可能出现脚趾发紫;然而,这是血管收缩和缺血的结果。在没有压力和/或剪切力的情况下,不应将这些损伤诊断为压力性损伤。

总结

COVID-19观察到的紫癜样或压不褪色紫色皮损与DTPI不一致,因为它们对底层软组织细胞没有压力诱导的损伤,皮肤改变可能代表凝血引起的组织缺血。卧床、低血压和低氧血症的高危患者发生深部组织压力性损伤的风险较高,但这些压力性损伤可见于承受压力的皮肤和软组织。虽然暴发性紫癜这个术语可能是正确的,但也有人对这种现象提出了其他术语,如网状紫癜、网状青斑和皮肤血管炎。尚需要进一步的研究才能充分阐明COVID-19与紫癜及其他皮肤表现的病理生理联系。在确认皮肤改变不是由压力引起后,伤口护理人员不应将这些皮肤改变标记为DTPI,而应标记为COVID-19的潜在皮肤表现。

关于COVID-19整个疾病状态的研究仍在继续进行。伤口护理临床医生可以提请研究人员关注皮肤改变,从而帮助完成这些研究,以了解相关的病理生理学。迄今为止,尚未对这些皮肤相关疾病的治疗进行研究。为了增进我们对COVID-19皮肤表现的理解,考虑向美国皮肤病学会COVID-19皮肤病登记中心提交病例报告,网址: https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coronavirus/registry.12

这份NPIAP白皮书旨在向公众广泛分发。请与您可能从本信息中受益的联系人分享。本内容版权(除非另有规定)归NPIAP所有。

鸣谢

NPIAP衷心感谢以下人员的贡献。

作者:Joyce Black博士,内布拉斯加大学医学中心;Janet Cuddigan博士,内布拉斯加大学医学中心,代表美国压力性损伤咨询委员会。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

审稿人

本白皮书由NPIAP董事会审阅。以下人员对内容提供了反馈:马萨诸塞州总医院的Virginia Capasso博士、罗格斯大学的Jill Cox博士、纽约大学朗格尼医疗的Barbara Delmore博士、南加州大学伦纳德•舍弗卫生政策与经济学中心的William Padula博士、南阿拉巴马大学的Joyce Pittman博士、萨拉托加医院伤口愈合医疗组的Lee Ruotsi博士、佐治亚理工学院的Sharon Sonenblum博士、梅奥诊所的Ann Tescher博士。

咨询和指导

NPIAP感谢内布拉斯加大学医学中心皮肤科主席Ashley Wysong博士和纽约州阿默斯特德门学院伤口愈合研究中心主任Laura Edsberg博士提供的指导。

病例研究及图片

图2和图3经康奈尔大学Jeffrey Laurence博士许可使用。出版商Elsevier授予许可,允许对其在COVID-19资源中心中提供的所有COVID-19相关研究在承认原始来源的情况下,拥有以任何形式或通过任何方式进行不受限制地研究重复使用和分析的权利。

图1中的照片经美国密歇根州罗亚尔奥克的Beaumont Health许可使用。

Author(s)

Joyce Black

PhD, RN CWCN, FAAN

University of Nebraska Medical Center

Joyce Cuddigan*

PhD, RN, FAAN

University of Nebraska Medical Center on behalf of the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel

Email jcuddiga@unmc.edu

* Corresponding author

References

- Bouaziz JD et al. Vascular Skin Symptoms in COVID-19: A French Observational Study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Apr 27. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16544. Online ahead of print.

- Guan WJ et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med, 2020 Apr 30;382(18):1708-1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. Epub 2020 Feb 28.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous Manifestations in COVID-19: A First Perspective. 2020 Mar 26. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16387. Online ahead of print.

- Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020.

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, Nuovo G, Salvatore S, Harp J, Baxter-Stoltzfus A Laurence J. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: A report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020 Apr 15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007 [Epub ahead of print]

- Oxley, TJ et al. Large-Vessel Stroke as a Presenting Feature of Covid-19 in the Young. New Eng J Med April 28, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787

- Poissy J. et al. Pulmonary Embolism in COVID-19 Patients: Awareness of an Increased Prevalence. Circulation. 24 Apr 2020. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.120.047430.

- Cao W and Li T. COVID-19: towards understanding of pathogenesis. Cell Res 30, 367–369 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-020-0327-4.

- Tang N et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768.

- Betrosian AP, Berlet T, Agarwal B. Purpura Fulminans in Sepsis. J Med Sciences 332 (6) 2006, 339-345.

- Edsberg L et al. (2018, March 2) Histology of Deep Tissue Pressure Injury: What can be learned from cadavers. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Conference, Las Vegas NV.

- American Academy of Dermatology (2020, May 12). COVID-19 Dermatology Registry. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coronavirus/registry.