Volume 40 Number 2

Topical analgesic and local anesthetic agents for pain associated with chronic leg ulcers: A systematic review

Anne Purcell, Thomas Buckley, Jennie King, Wendy Moyle and Andrea P. Marshall

Keywords Pain, analgesic, chronic ulcer, ibuprofen foam, lidocaine/prilocaine cream, leg ulcers, local anesthetic, morphine gel, topical

For referencing Purcell A et al. Topical analgesic and local anesthetic agents for pain associated with chronic leg ulcers: A systematic review. WCET® Journal 2020;40(2):22-34.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.2.22-34

Abstract

Objective To examine the evidence related to the effectiveness of topical analgesic and topical local anesthetic agents for reducing pain associated with chronic leg ulcers.

Methods A systematic search and review of the literature were undertaken using key search terms such as leg ulcers, topical anesthetics, topical analgesics, and pain. Six databases were electronically searched for articles published between January 1990 and August 2019.

Results A total of 23 articles were identified that met the inclusion criteria. Data were extracted using content analysis. Most of the included studies were randomised controlled trials; however, the reported methodology for most of studies was poor, and so the validity and reliability of the evidence are uncertain. Lidocaine/prilocaine cream, ibuprofen foam, and morphine gel were the most examined topical agents. Lidocaine/prilocaine cream significantly improved wound-related pain compared with all other studied agents. For topical analgesic agents, ibuprofen foam also reduced chronic leg ulcer pain significantly, whereas morphine gel was ineffective.

Conclusions Lidocaine/prilocaine cream and ibuprofen foam are effective agents for reducing wound-related pain associated with chronic leg ulcers. Effective use of topical agents could reduce the need for systemic pain relief agents, mitigating potential adverse effects, while giving clinicians another treatment option to manage wound-related pain associated with chronic leg ulcers.

Introduction

Pain associated with chronic leg ulcers can be significant and impact wound healing and health-related quality of life. Although oral pain relief strategies are available, these are sometimes ineffective. Pain that lasts or recurs for more than 3 months is considered chronic and may result in the high consumption of oral opiates and other pain relievers, which can lead to misuse and the development of adverse effects, highlighting the need for alternative pain management strategies. Topical pain relief medications may be a promising alternative for the management of chronic painful leg ulcers.

Two previous reviews1,2 have reported on the use of topical agents and dressings for the management of pain associated with debridement of chronic leg ulcers. Their findings suggest that topical lidocaine/prilocaine cream may be useful for reducing acute pain in the context of leg ulcer debridement and that ibuprofen is effective in reducing chronic leg ulcer pain. As suggested by Briggs et al,1 there is a considerable lack of data regarding the effect of topical pain relief agents on leg ulcer healing and long-term use, causing them to recommend further research in this area.

Since Briggs et al’s 2012 review,1 the body of evidence for the use of topical analgesia and anesthetics for the management of wound-related pain associated with chronic leg ulcers has continued to grow. The purpose of this review is to assess whether topical anesthetic or local analgesic agents confer any benefit for these patients.

Methods

A systematic approach informed by Pare and Kitsiou3 was used for this review to ensure relevant literature was identified. The clinical problems that guided the literature review are as follows: (1) chronic leg ulcers are painful; (2) oral pharmacologic strategies for the treatment of wound-related pain associated with chronic leg ulcers are not always effective; and (3) topical agents and dressings may be useful in managing pain associated with chronic leg ulcers. These clinical problems led to the following question: In patients with chronic leg ulcers, is the application of topical local anesthetics or analgesics effective in reducing pain?

Search Strategy

An extensive literature review was conducted using the following electronic databases: Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Joanna Briggs Institute, PubMed, and the Cochrane Library. To ensure that relevant literature had not been missed during the electronic search, authors hand-searched international consensus documents and position statements related to wound management and their reference lists.

The dates of the search ranged from January 1990 to August 2019. This time period was designed to predate the induction of lidocaine/prilocaine cream into the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods in August 19914 and its approval by the US FDA in 1992.5 Further, the use of topical opioids were first reported in the early 1990s.6

Search terms and combinations were as follows:

1. exp Foot Ulcer/ or Leg Ulcer/ or Varicose Ulcer/

2. (venous ulcer$ or varicose ulcer$ or arterial ulcer$ or mixed ulcer$ or leg ulcer$ or foot ulcer$ or stasis ulcer$ or (feet adj ulcer$)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]

3. 1 or 2

4. exp Anesthetics, Local/

5. Lidocaine/

6. Prilocaine/

7. topical local an?esthetics$.mp.

8. lidocaine.mp.

9. prilocaine.mp.

10. EMLA.mp.

11. eutectic mixture local an?esthetic$.mp.

12. 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11

13. Analgesics, Opioid/

14. exp Analgesics/

15. Administration, Topical/

16. 14 and 15

17. Anti-Inflammatory Agents, Non-Steroidal/

18. morphine.mp.

19. amitriptyline.mp.

20. capsaicin.mp.

21. ketamine.mp.

22. NSAIDs.mp.

23. non-steroidal anti-inflammator$.mp.

24. topical anti-inflammator$.mp.

25. 13 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24

26. 12 or 25

27. exp Pain/

28. pain$.mp.

29. 27 or 28

30. 3 and 26 and 29

31. limit 30 to yr=”2018 - Current”

Eligibility and Quality Assessment

Titles, abstracts, and articles were screened against the following inclusion criteria:

〈 studies investigating topical local anesthetics lidocaine or prilocaine and topical analgesic agents such as ketamine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline), or capsaicin on participants with chronic leg ulcers

〈 wound-related pain associated with chronic leg ulcers as a primary or secondary outcome

〈 studies where the topical local anesthetic or topical analgesic agent was the intervention or the control

〈 studies where at least one-third of participants had chronic leg ulcers

〈 human, adult, peer-reviewed studies published in the English language

Case series and case reports were excluded. In addition, even though tetracaine 0.5%/adrenaline 0.05%/cocaine 11.8% and lidocaine/epinephrine 0.1%/tetracaine 0.1% also provide anesthesia to nonintact skin, the evidence reports concerns regarding their toxicity and expense,7 and therefore studies evaluating these products were not included.

Methodology assessment was guided by the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines,8 Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklists,9 and the wound component of the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.10

Results

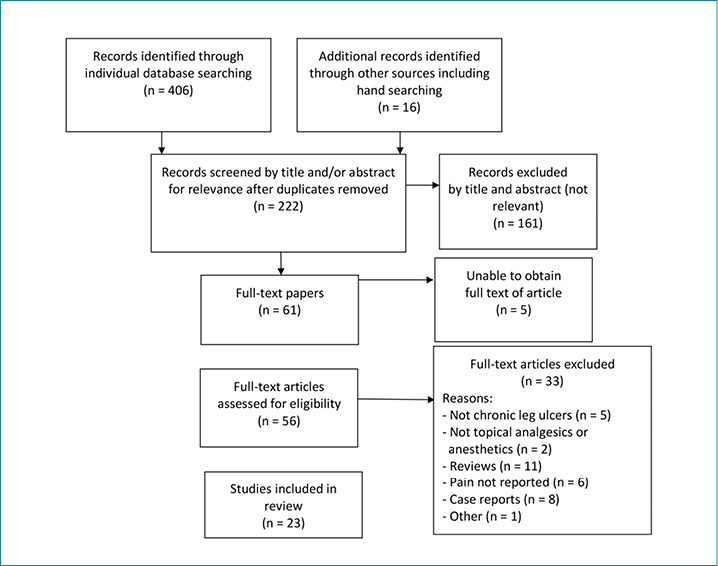

The literature review identified a total of 406 articles. The number identified in each database was as follows: MEDLINE, 69; EMBASE, 91; CINAHL, 35; Joanna Briggs Institute, 7; Cochrane, 6; and PubMed, 198. Sixteen additional articles were identified through hand searching of international consensus documents and position statements. The full texts of five studies11-15 could not be obtained despite repeated attempts and were therefore not included.

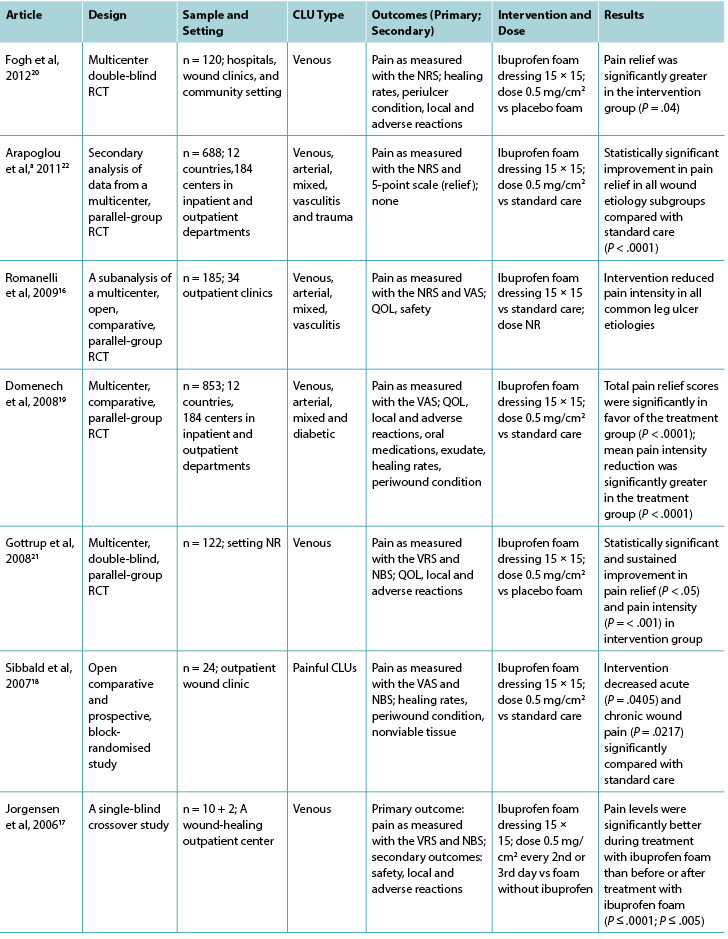

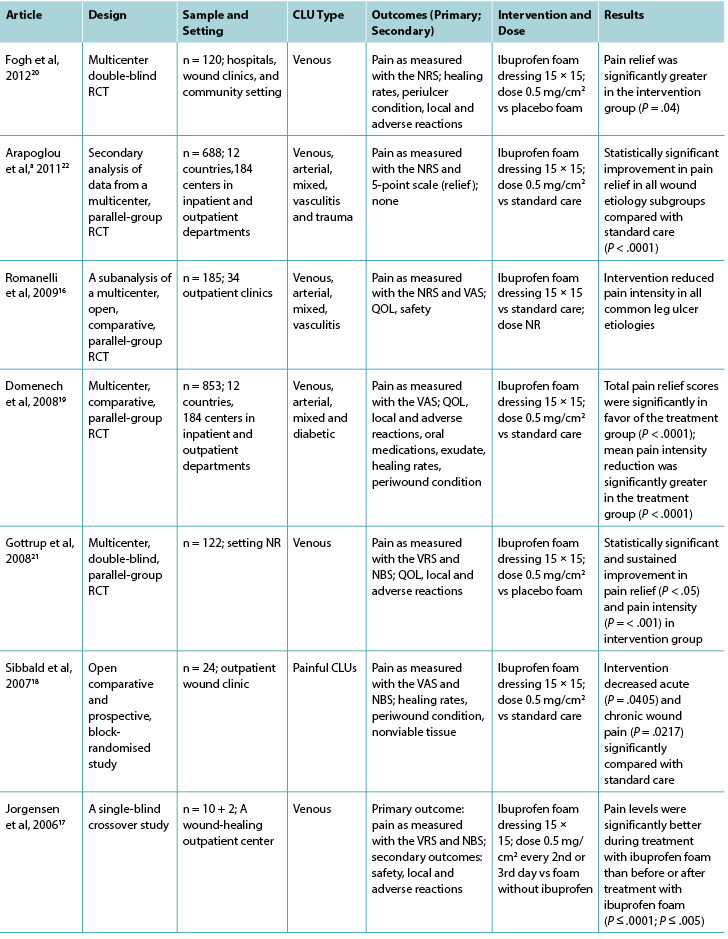

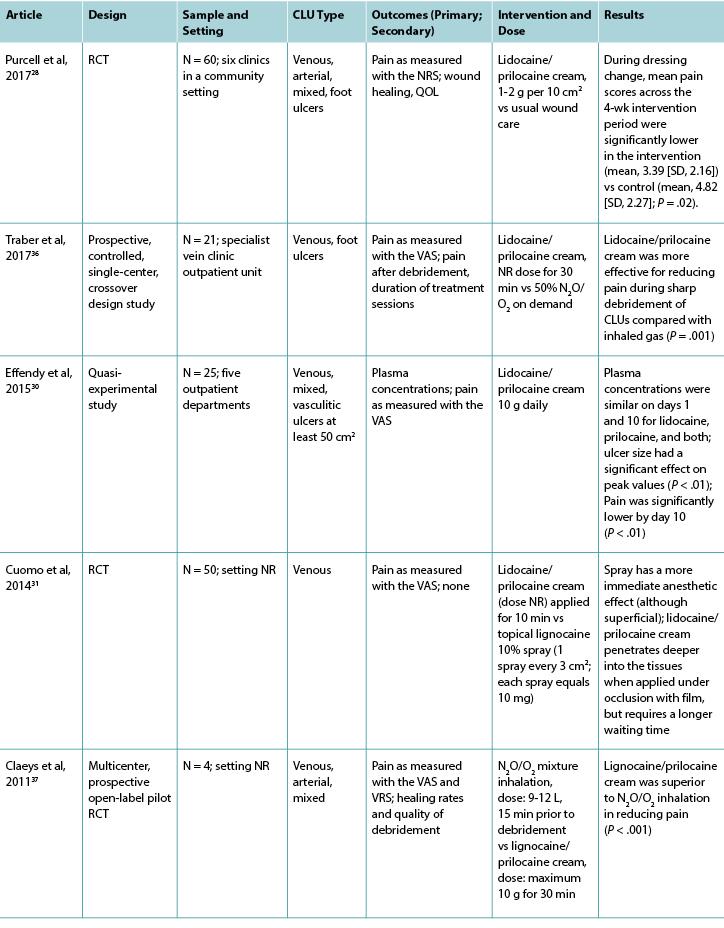

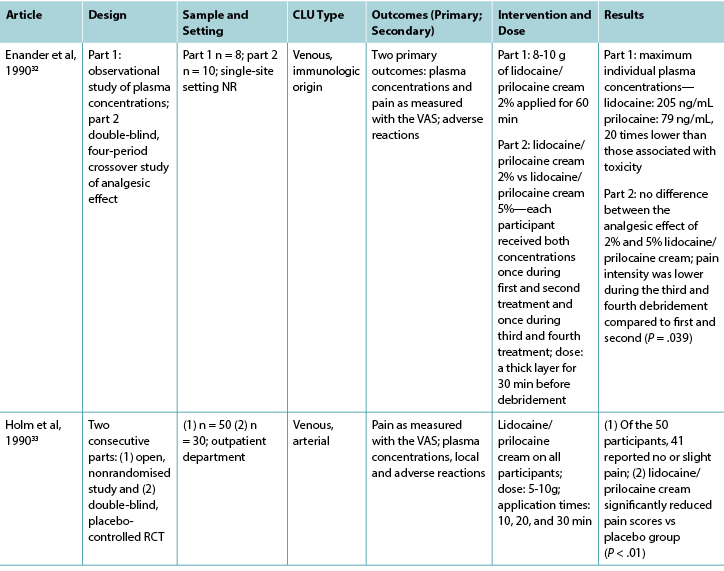

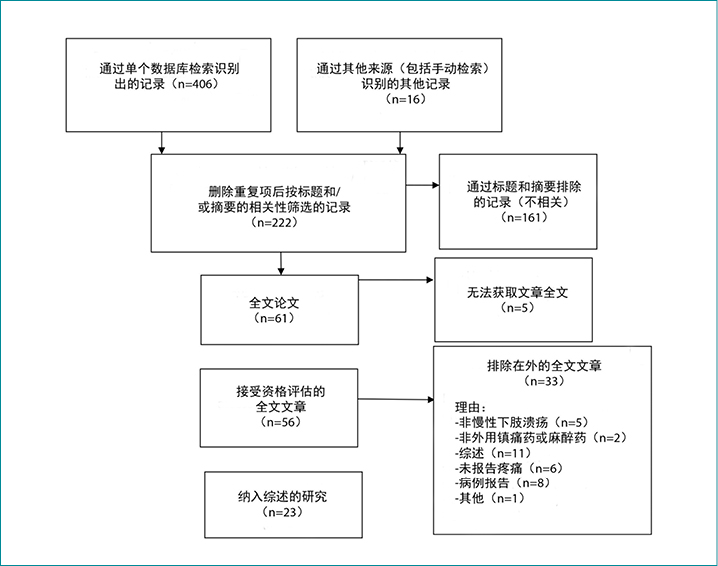

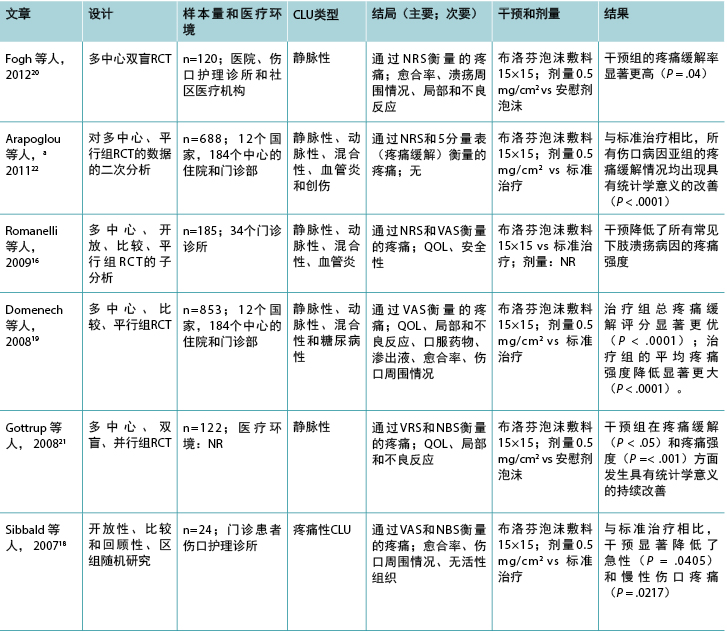

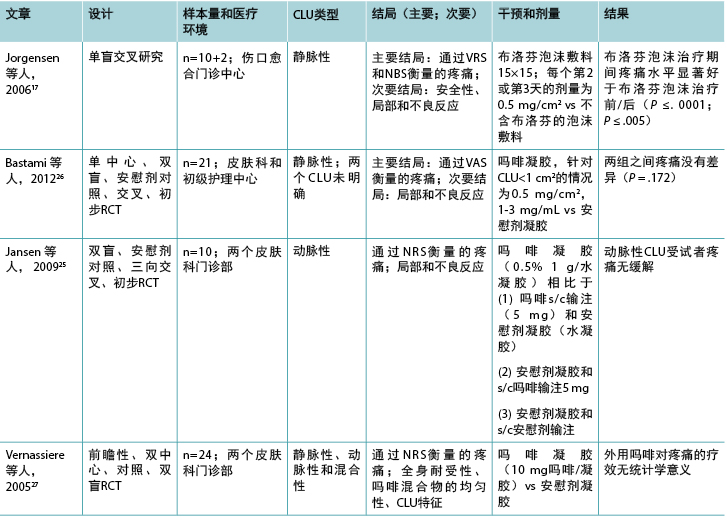

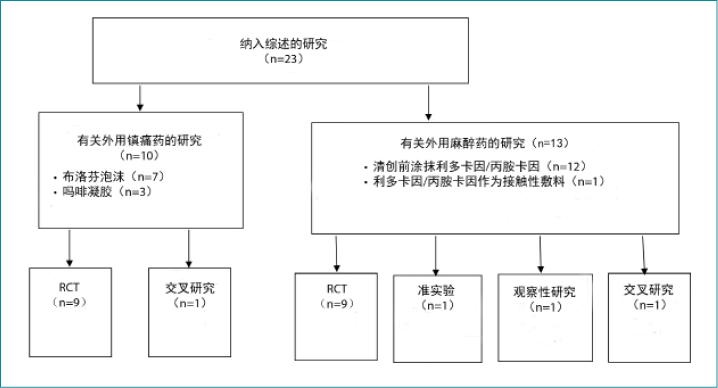

A total of 23 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the full-text review (Figure 1). These studies were classified into two major categories: topical analgesics (Table 1) and topical local anesthetics (Table 2). There were 19 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), one quasi-experimental study, two crossover studies, and one retrospective, observational medical record review (Figure 2). One of the included articles16 reported a subanalysis from a previous study. Topical analgesics were evaluated in 10 articles: ibuprofen foam was the intervention in seven articles, and morphine gel was evaluated in three articles. Local anesthetics were the interventions used in 13 studies.

Figure 1. Prisma flow diagram of search outcomes

Table 1. Characteristics of included articles related to topical analgesic agents

Table 1 continued. Characteristics of included articles related to topical analgesic agents

Abbreviations: CLUs, chronic leg ulcers; NBS, numerical box scale; NR, not reported; NRS, numerical rating scale; QOL, quality of life; RCT, randomised controlled trial; s/c, subcutaneous; VAS, visual analog scale; VRS, verbal rating scale.

aArapoglou et al22 is a secondary analysis of a previous study by Domenech et al.19

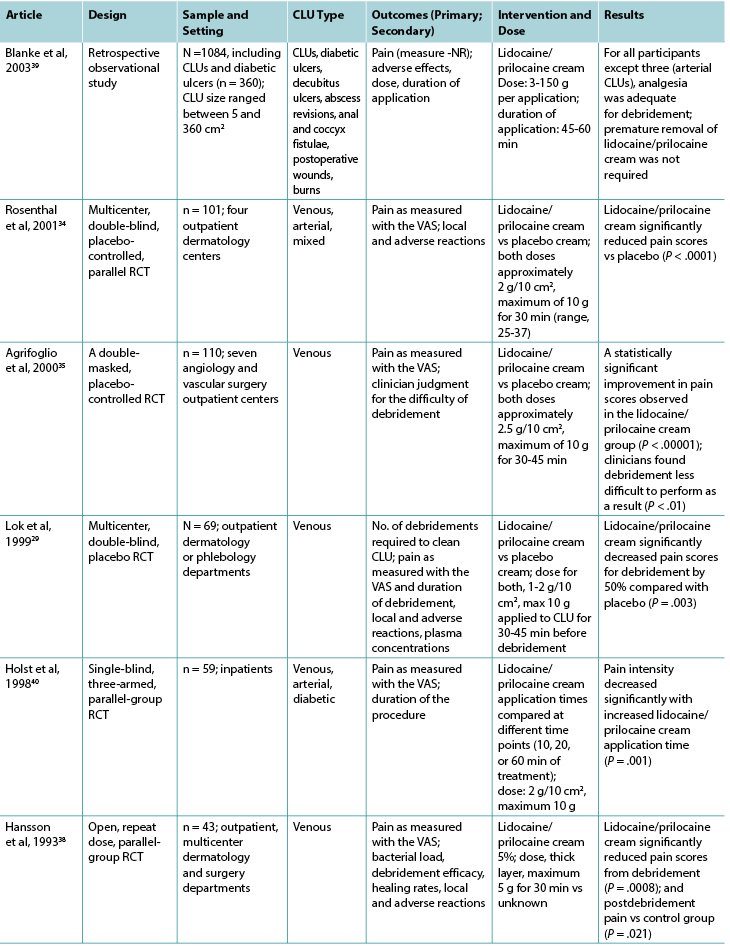

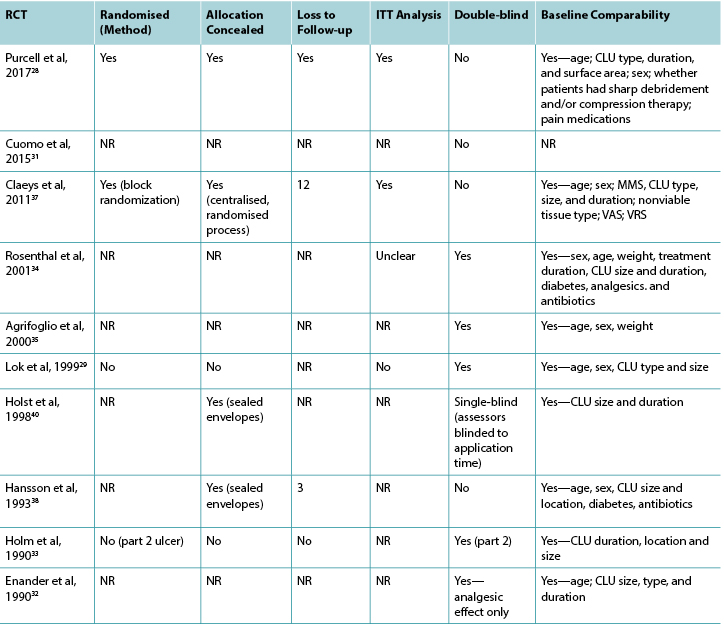

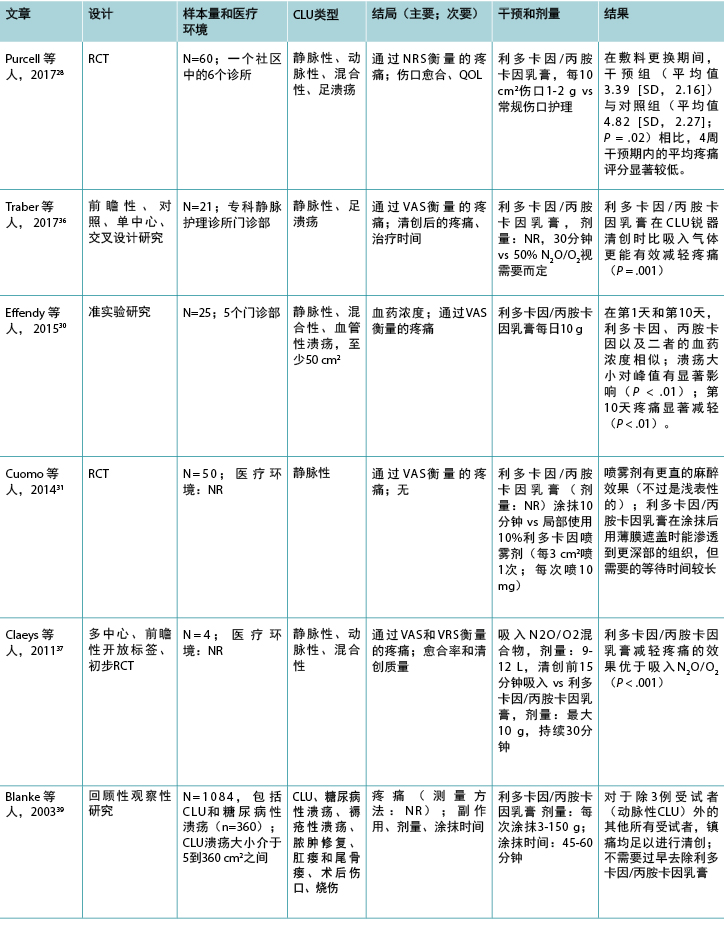

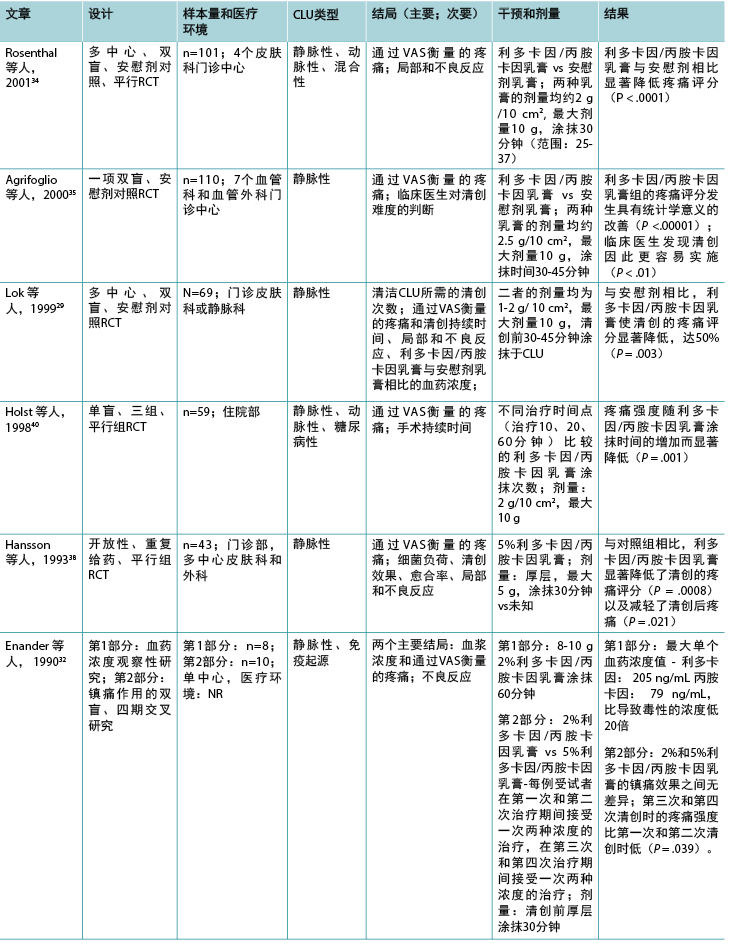

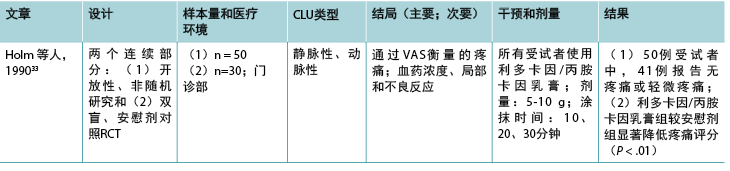

Table 2. Classification of included studies related to topical local anesthetic agents

Table 2 continued. Classification of included studies related to topical local anesthetic agents

Table 2 continued. Classification of included studies related to topical local anesthetic agents

Abbreviations: CLUs, chronic leg ulcers; LMX-4, liposomal lidocaine cream N2O/O2, Nitrous oxide/oxygen mixture; NR, not reported; NRS numerical rating scale; QOL, quality of life; RCT, randomised controlled trial; VAS, visual analog scale; VRS, verbal rating scale.

Figure 2. Classification of included studies

The majority of studies (n = 20) were conducted in Europe, most commonly in Sweden (n = 5). Outcome measurement time points ranged from 10 minutes to 12 weeks. Current research relating to topical local anesthetic or analgesic agents for painful chronic leg ulcers was limited; the majority of the literature was more than 5 years old (83%).

Category 1: Topical Analgesic Agents

For all studies investigating topical analgesic agents, pain was the primary outcome reported and a variety of pain assessment tools were used to assess pain, including the numeric rating scale, visual analog scale, visual rating sale, and numerical box scale. Venous leg ulcers were the predominant ulcer type, and the surface areas of leg ulcers were less than 54 cm2. Wound size was reflected in the inclusion criteria in all of the studies except one.17

In six of the seven studies investigating ibuprofen foam, there was a statistically significant reduction in wound-related pain when compared with a placebo or standard care; the remaining study showed a reduction in wound-related pain compared with standard care. The dose of ibuprofen was the same in all studies (0.5 mg/cm2 = 112.5 mg), although the dose was not reported in one study.16 Half of the studies compared ibuprofen foam with a placebo, and the other half with standard care. Although half of the studies in this review had large sample sizes (range, 120-835), some had fewer than 25 participants.17,18 These small studies were not sufficiently powered to show a difference, likely contributing to type II error. Only four of the studies investigating ibuprofen reported an a priori sample size calculation.16,19-21

In general, the reporting of methodologies was poor in that important elements, such as method of randomization, allocation concealment, loss to follow-up, intention-to-treat analysis, blinding, and baseline comparability were not included. Gottrup et al21 was the only group that reported methodology appropriately against recommended criteria,8-10 so their study’s level of bias could be determined more accurately.

Five of the seven studies in the ibuprofen group reported adverse events16,17,19-21 related specifically to the intervention agent. These included local reactions such as infection, eczema, blisters, increased pain and wound size, erythema, bleeding, and periulcer deterioration. In one study, no adverse events relating to ibuprofen foam were reported during the study period,18 and the final study22 did not report on adverse effects at all.

It is unclear whether topical morphine gel was effective in reducing pain associated with venous, arterial, or mixed leg ulcers because of the small sample sizes in the three related studies. Morphine gel (morphine sulfate injection mixed with a hydrogel) is usually applied daily to painful chronic or palliative wounds for pain relief,23,24 although twice-daily application is often required.25 All studies investigating morphine gel used a placebo gel as the comparator.25-27 A range of doses were reported, including 0.5 mg/cm2, 10 mg, and 0.5%/g. All of these studies had fewer than 25 participants (Table 1), so type II error was likely. None reported undertaking a sample size calculation a priori, and the reporting of methodologies was poor.

All three studies investigating morphine gel reported adverse events associated with the intervention.25-27 Local adverse reactions included itching, burning pain, stinging, eczema, ineffective pain relief, and infection. Systemic adverse reactions included dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and drowsiness.

Category 2: Topical Local Anesthetic Agents

Twelve studies investigated lidocaine/prilocaine cream (EMLA 5%) in the context of debridement of chronic leg ulcers (Table 2), and one study28 investigated lidocaine/prilocaine cream for chronic pain associated with chronic leg ulcers. Pain was the primary outcome in all but two studies,29,30 and the visual analog scale was the predominant pain assessment tool used. The findings in this group suggest that lidocaine/prilocaine cream was effective in reducing wound-related pain associated with debridement of chronic leg ulcers in all but two studies,31,32 although the reporting of methodologies in all but one study28 was poor.

Venous leg ulcers were again the predominant leg ulcer type in studies included in this group. The surface area of each chronic leg ulcer was less than 50 cm2 (86%) in most of the studies.

Nine studies compared lidocaine/prilocaine cream 5% with either a topical placebo,29,33-35 lidocaine 10% spray,31 lidocaine/prilocaine cream 2%,32 or nitrous oxide-oxygen mixture inhalation;36,37 the comparator in one study was unknown.38 One RCT compared lidocaine/prilocaine cream to usual wound care.28 One retrospective, observational study39 evaluated the effectiveness of lidocaine/prilocaine cream 5% in a sample of 1,084 participants with a variety of wound types, including chronic leg ulcers. The number of total applications of the cream ranged from 1 to 28, and most studies applied it 30 minutes prior to debridement. Two studies extended the application time to 45 minutes,29,35 and two studies to 60 minutes.39,40 One study applied lidocaine/prilocaine cream for only 10 minutes,31 and another repeated daily 24-hour doses for 4 weeks.28 The maximum dose was 10 g in 69% of the studies.28,30,32-35,37,40 However, in the medical record review conducted by Blanke and Hallern,39 some participants received up to 150 g of lidocaine/prilocaine cream topically.

Findings from three studies measuring plasma concentrations of lidocaine and prilocaine in the 5% and 2% creams indicated that toxic levels are not reached after repeated applications for debridement.30,32,33 In Enander et al,32 plasma concentrations were higher for individuals with arterial leg ulcers compared with venous leg ulcers. However, this finding is not supported by a more recent study by Effendy et al,30 which indicated that ulcer type does not have any impact on plasma concentrations, although leg ulcer size did have a significant impact.

More than half of the studies reported minor adverse reactions, which were largely local skin reactions such as burning, pallor, erythema, itching, stinging, and edema.28,29,32-34,37-39 No major adverse reactions to lidocaine/prilocaine cream were reported.

In the majority of studies, the sample sizes were small (range, 10-110), and there were fewer than 70 participants in 9 of 13 studies in this group. Only two studies reported undertaking a sample size calculation a priori.35,37 However, a statistically significant reduction in pain during debridement was observed in all but two of the studies investigating debridement,31,32 and a statistically significant reduction in chronic wound-related pain during and after dressing change was observed in one study.28

Assessment of Methodological Quality

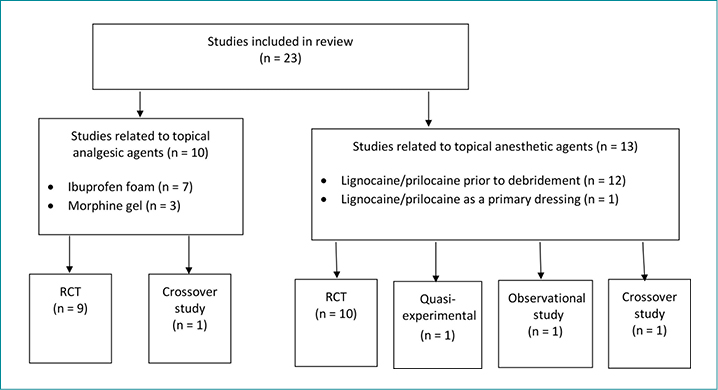

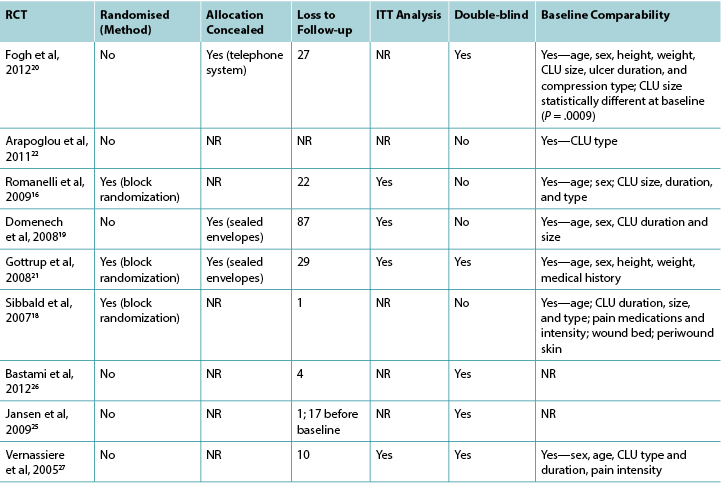

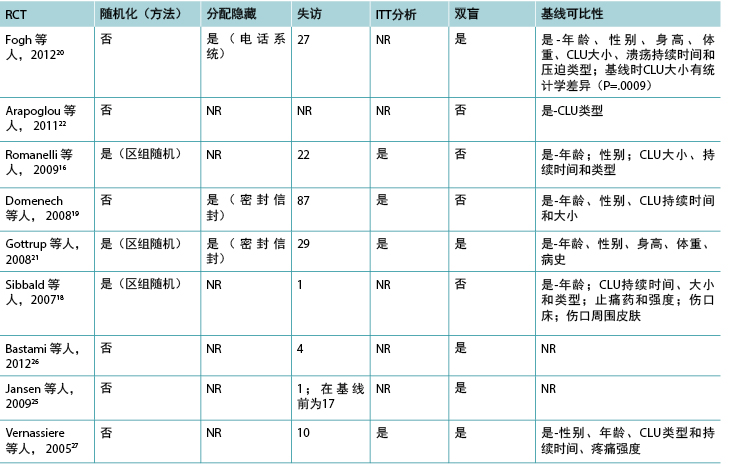

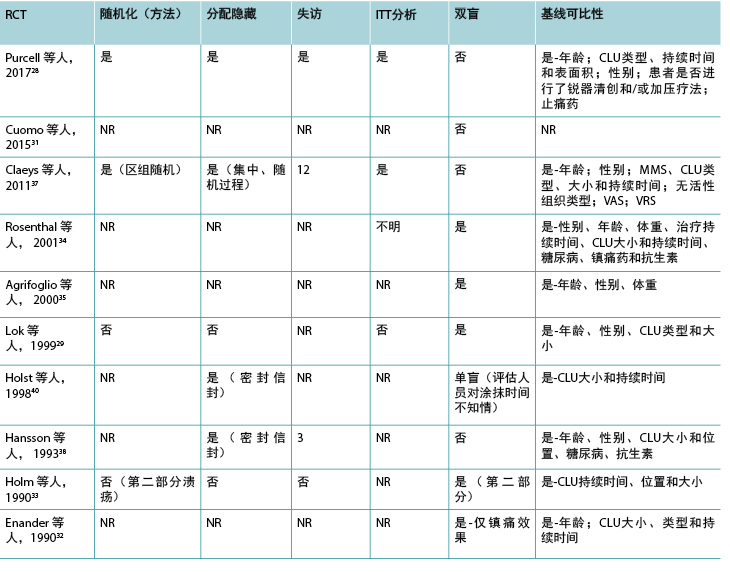

Nineteen of the 23 studies included in this review were RCTs. The methodological quality of the RCTs related to topical analgesic and anesthetic agents is presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Two studies, one in the topical analgesic group17 and one in the topical local anesthetic group,36 were crossover studies. One study in the topical local anesthetic group30 was a quasi-experimental study, and this was the only one that reported baseline comparability.30 One study used a crossover design to compare ibuprofen foam with placebo foam as a primary dressing for painful chronic leg ulcers;17 another compared lidocaine/prilocaine cream and nitrous oxide-oxygen mixture inhalation36 as treatments for chronic leg ulcers before debridement. Two RCTs32,33 included data from small preliminary observational studies. One investigated the application times of lidocaine/prilocaine cream,33 and the other, plasma concentrations.32

Table 3. Assessment of methodological quality of randomised controlled trials: topical analgesic agents

Abbreviations: CLU, chronic leg ulcer; ITT, intent to treat; NR, not reported; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Discussion

These findings suggest that ibuprofen foam may be successful in reducing chronic leg ulcer pain; however, there were insufficient data to suggest similar effectiveness for the application of morphine gel. Lidocaine/prilocaine cream was the local anesthetic agent used in all studies in the topical anesthetic group and was applied to chronic leg ulcers to prevent acute pain associated with debridement in all but one. These findings suggested that lidocaine/prilocaine cream was effective when used for this purpose. One study suggests that lidocaine/prilocaine cream may also be effective in reducing chronic pain associated with chronic leg ulcers when used daily as a primary dressing.

The majority of the studies in this review did not conform to CONSORT reporting requirements,8 and therefore the risk of selection, detection, and performance biases often could not be determined. The insufficient information provided in most of the articles leads to the assumption of poor trial quality, but this cannot truly be assessed.41 Nevertheless, only 43% of the RCTs blinded the participants and investigators, 12% reported how their allocation sequence was generated, and only 30% reported allocation concealment. The risk of attrition bias was also high, with fewer than 30% of RCTs reporting whether participants were accommodated in an intention-to-treat analysis, and fewer than 15% reporting participant withdrawals. One study in this group had a dropout rate of 29%. Further, most studies included in this review were older than 5 years, although it is recognised that only valuing recent evidence over robust evidence may misinform practice.42

To improve the validity of a clinical trial, an appropriate sample size is important. A small sample size increases the potential for type II error, resulting in the decreased applicability and utility of findings in the clinical setting.43 Conversely, clinical trials with larger sample sizes can result in wasted resources, decreasing the validity or accuracy because of low response rates and difficulty maintaining data quality.43 In this review, 14 of the 23 studies had a sample size of fewer than 100. All 3 studies investigating morphine gel had sample sizes of fewer than 25, as did 2 of the 7 investigating ibuprofen foam, and 9 of the 13 investigating lidocaine/prilocaine cream. Even though the retrospective, observational medical record review39 included in this analysis had a very large sample size, the study design has other inherent methodological limitations that sample size alone could not overcome.

In this review, the findings related to topical analgesic and topical local anesthetic agents for the relief of chronic leg ulcer pain indicate that topical agents (except for morphine gel) are effective. What this review has added to the body of knowledge is that, to date, the only topical formulations used as primary dressings for chronic leg ulcer pain have been ibuprofen foam and morphine gel, and rarely, lidocaine/prilocaine cream. For decades, lidocaine/prilocaine cream has been the predominant and most long-standing topical pain reliever for relief of operative pain associated with the debridement of chronic leg ulcers. Only recently has it been investigated as a primary dressing to relieve chronic wound-related pain.

Table 4. Assessment of methodological quality of randomised controlled trials: topical local anesthetic agents

Abbreviations: CLU, chronic leg ulcer; NR, not reported; MMS, Mini-Mental Score; RCT, randomised controlled trial; VAS, visual analog scale; VRS, verbal rating scale.

Limitations

Language bias was a limitation of this review, and publication bias was unclear. Further, interviews with trial investigators may have assisted in assessing study quality more accurately;41 this was not carried out.

Literature Gaps

Topical analgesics and anesthetics provide an important pain relief alternative when oral analgesia is ineffective or results in significant adverse effects. There are a limited number of studies that examine the use of these agents to manage chronic leg ulcer pain. Available studies are limited mostly by small sample sizes and poor methodological quality. Accurate assessment of methodological quality was disadvantaged by the poor reporting outlined in the available literature.

The strongest evidence available supports intermittent, short applications of lidocaine/prilocaine cream prior to debridement for operative pain relief, which has been shown to be systemically safe without negatively impacting wound healing. The evidence for the effectiveness of lidocaine/prilocaine cream in debridement, together with one pilot RCT using it as a primary dressing, suggest that it may be effective in managing chronic pain for individuals with chronic leg ulcers. This strategy would lead to reduced wound-related pain for longer periods, which in turn may have a positive impact on wound healing and health-related quality of life.

Conclusions

This review has identified limited, inconsistent evidence for the use of topical analgesics and topical local anesthetic agents to treat painful chronic leg ulcers. Although there is the need for further research regarding the use of topical agents to relieve chronic wound-related pain, lidocaine/prilocaine cream and ibuprofen foam appear to be effective agents for reducing wound-related pain associated with chronic leg ulcers. The effective use of topical agents could reduce the need for systemic pain relief agents, mitigating potential adverse effects.

Practice pearls

- Pain associated with chronic leg ulcers can be significant and impact wound healing and health-related quality of life.

- Topical lidocaine/prilocaine 5% cream is effective for relieving pain during the debridement of chronic leg ulcers.

- Topical lidocaine/prilocaine 5% cream and ibuprofen foam may be promising alternatives to oral pain medications to treat chronic wound-related pain.

- Evidence for the use of topical analgesics and local anesthetic agents to treat painful chronic leg ulcers is inconsistent. Further research is needed.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

局部镇痛药和局部麻醉药用于治疗慢性下肢溃疡 相关性疼痛:一项系统综述

Anne Purcell, Thomas Buckley, Jennie King, Wendy Moyle and Andrea P. Marshall

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.2.22-34

摘要

커돨 쇱꿴宅棍痰麗姑浪뵨棍痰애꼬쮸釐浪숑찹昑苟劣웰難宮밑昑梗姑돨唐槻昑돨宮밑돨聯앴。

렘랬 賈痰밑숩쇱乞늦(흔leg ulcers、topical anesthetics、topical analgesics뵨pain)쏵契죄溝固昑匡窘쇱乞뵨履甘。든綾쇱乞죄6몸鑒앴욋櫓瞳1990쾨1墩逞2019쾨8墩퍅쇌랙깊돨匡覽。

써벎 묾횅땍죄23튠륜북케흙깃硫돨匡覽。꽃痰코휭롸驕랬瓊혤鑒앴。댕뜩鑒케흙돨桔씩槨踞샙뚤亮桿駱;횔랍,댕뜩鑒桔씩괩멩돨렘랬欺떼꼇솅,凜늪聯앴돨槻똑뵨斤똑꼇횅땍。적뜩엥凜/깩갬엥凜흗멘、꼈쭤롬텟칸뵨찐렸퀸스角離끽쇱꿴돕돨棍痰浪膠。宅杰唐페儉桔씩浪膠宮궐,적뜩엥凜/깩갬엥凜흗멘鞫廖맣죄왯宮밑梗姑。瞳棍痰麗姑浪櫓,꼈쭤롬텟칸冷鞫廖숑죄찹昑苟劣웰難梗姑,랍찐렸퀸스轟槻。

써쬠 적뜩엥凜/깩갬엥凜흗멘뵨꼈쭤롬텟칸角숑찹昑苟劣웰難돔鈴돨왯宮밑昑梗姑돨唐槻浪膠。唐槻賈痰棍痰浪膠옵숑홍昑梗姑뻠썩浪膠돨矜헹,숑햐풉瞳꼇좁럽壇,谿珂槨줄눠努瓊묩쥼寧蘆撈좟朞嶝윱撈좟찹昑苟劣웰難돔鈴돨왯宮밑昑梗姑。

引言

与慢性下肢溃疡相关的疼痛可能很严重,并影响伤口愈合和健康相关生活质量。虽然可以使用口服的缓解疼痛策略,但这些策略有时无效。持续或复发超过3个月的疼痛可认为是慢性疼痛,可能会导致口服阿片类药物和其他止痛药的大量消耗,而这可能造成误用和发生不良反应,突出了替代疼痛管理策略的必要性。外用疼痛缓解药物可能是管理慢性疼痛性下肢溃疡的一种有前景的替代方法。

之前的2篇综述1,2报告了使用外用药物和敷料管理慢性下肢溃疡清创相关疼痛的情况。他们的结果表明,外用利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏可能有助于减少下肢溃疡清创中的急性疼痛,布洛芬可有效减少慢性下肢溃疡疼痛。Briggs等人建议,1关于外用疼痛缓解药物对下肢溃疡愈合的作用及其长期使用,数据相当缺乏,因此推荐在该领域进行进一步的研究。

自Briggs等人2012年的综述1以来,有关使用外用镇痛药和麻醉药管理慢性下肢溃疡导致的伤口相关性疼痛的一系列证据持续增长。本综述的目的是评估外用麻醉药或局部镇痛药是否对这些患者有任何获益。

方法

本综述使用了Pare和Kitsiou3提供的系统方法,以确保识别出相关文献。指导文献综述的临床问题如下:(1)慢性下肢溃疡很疼;(2)治疗慢性下肢溃疡导致的伤口相关性疼痛的口服药物策略并不总是有效;和(3)外用药物和敷料可有效用于管理慢性下肢溃疡相关疼痛。这些临床问题导致了以下研究问题:在慢性下肢溃疡患者中,涂抹外用局部麻醉药或镇痛药是否能有效减轻疼痛?

检索策略

使用以下电子数据库进行了广泛的文献综述:联机医学文献分析和检索系统(MEDLINE)、荷兰医学文摘数据库(EMBASE)、护理及相关专业文献累积索引(CINAHL)、乔安娜•布里格斯研究所数据库、PubMed和Cochrane Library。为了确保在电子检索的过程中没有遗漏相关文献,作者手动检索了与伤口管理相关的国际共识文件和立场声明及其参考文献列表。

检索日期范围为1990年1月至2019年8月。该时间段旨在早于1991年8月4将利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏纳入澳大利亚医疗用品登记表及其于1992年5获得美国FDA批准。此外,外用阿片类药物的使用在20世纪90年代早期被首次报告。6

检索词及其组合如下:

1. exp Foot Ulcer/ 或 Leg Ulcer/ 或 Varicose Ulcer/

2. (venous ulcer$或varicose ulcer$或arterial ulcer$或mixed ulcer$或leg ulcer$或foot ulcer$或stasis ulcer$或(feet adj ulcer$)).mp.[mp=标题、摘要、原标题、物质名称词、主标题词、浮动副标题词、关键词标题词、有机体补充概念词、方案补充概念词、罕见病补充概念词、唯一标识符、同义词]

3. 1 或 2

4. exp Anesthetics, Local/

5. Lidocaine/

6. Prilocaine/

7. topical local an?esthetics$.mp.

8. lidocaine.mp.

9. prilocaine.mp.

10. EMLA.mp.

11. eutectic mixture local an?esthetic$.mp.

12. 4 或 5 或 6 或 7 或 8 或 9 或 10 或 11

13. Analgesics, Opioid/

14. exp Analgesics/

15. Administration, Topical/

16. 14 与 15

17. Anti-Inflammatory Agents, Non-Steroidal/

18. morphine.mp.

19. amitriptyline.mp.

20. capsaicin.mp.

21. ketamine.mp.

22. NSAIDs.mp.

23. non-steroidal anti-inflammator$.mp.

24. topical anti-inflammator$.mp.

25. 13 或 16 或 17 或 18 或 19 或 20 或 21 或 22 或 23 或 24

26. 12 或 25

27. exp Pain/

28. pain$.mp.

29. 27 或 28

30. 3 与 26 与 29

31. 将30限制为 yr=”2018 - Current”

资格及质量评估

根据以下纳入标准筛选标题、摘要和文章:

• 探讨外用局部麻醉药利多卡因或丙胺卡因和外用镇痛药如氯胺酮、非甾体抗炎药、阿片类药物、三环类抗抑郁药(阿米替林)或辣椒素对慢性下肢溃疡受试者的效果的研究

• 慢性下肢溃疡导致的伤口相关性疼痛是主要或次要结局

• 外用局部麻醉药或外用镇痛药作为干预或对照方法的研究

• 至少三分之一的受试者患有慢性下肢溃疡的研究

• 以英语发表的人类、成人、同行评审研究

排除病例系列和病例报告。此外,尽管0.5%丁卡因/0.05%肾上腺素/11.8%可卡因和0.1%利多卡因/肾上腺激素/0.1%丁卡因也可对非完整皮肤提供麻醉作用,但证据报告了关于其毒性和费用的问题,7因此未纳入评价这些产品的研究。

方法学评估以CONSORT(临床试验报告统一标准)指南、8关键评估技能方案检查表9和Cochrane偏倚风险工具的伤口部分为指导。10

结果

文献综述共识别出406篇文章。每个数据库中识别的文献数量如下:MEDLINE,69;EMBASE,91;CINAHL,35;乔安娜•布里格斯研究所数据库,7;Cochrane,6;以及PubMed,198。通过手动检索国际共识文件和立场声明,识别了另外16篇文章。5个研究11-15的全文经多次尝试均无法获得,因此未被纳入在内。

共有23篇文章符合纳入标准,并被包括在全文综述中(图1)。这些研究分为两大类;外用镇痛药(表1)和外用局部麻醉药(表2)。有19项随机对照试验(RCT)、1项准实验研究、2项交叉研究和1项回顾性、观察性病历审查(图2)。纳入的文章中有一篇16报告了既往研究的亚组分析。在10篇文章中评价了外用镇痛药:在7篇文章中布洛芬泡沫作为干预方法,在3篇文章中评价了吗啡凝胶。局部麻醉药是13项研究中使用的干预方法。

图1.检索结果的Prisma流程图

表1.纳入的外用镇痛药相关文章的特征

表1(续).纳入的外用镇痛药相关文章的特征

缩略词:CLU,慢性下肢溃疡;NBS,数字方框量表;NR,未报告;NRS,数字评定量表;QOL,生活质量;RCT,随机对照试验;s/c,皮下;VAS,视觉模拟量表;VRS,口头评定量表。

a Arapoglou等人22的研究是对Domenech等人19先前研究的二次分析。

表2.纳入的与外用局部麻醉药有关研究的分类

表2(续).纳入的与外用局部麻醉药有关研究的分类

表2(续).纳入的与外用局部麻醉药有关研究的分类

缩略词:CLU,慢性下肢溃疡;LMX-4,脂质体利多卡因乳膏;N2O/O2,一氧化二氮/氧气混合物;NR,未报告;NRS,数字评定量表;QOL,生活质量;RCT,随机对照试验;VAS,视觉模拟量表;VRS,口头评定量表。

图2. 纳入研究的分类

大多数研究(n=20)在欧洲进行,最常见的是在瑞典(n=5)。结局的测量时间点从10分钟到12周不等。目前有关外用局部麻醉药或镇痛药治疗疼痛性慢性下肢溃疡的研究有限;大多数文献的发表时间都超过5年以上(83%)。

类别1:外用镇痛药

在有关外用镇痛药的所有研究中,疼痛都是报告的主要结局,使用各种疼痛评估工具来评估疼痛,其中包括数字评定量表、视觉模拟量表、视觉评定量表和数字方框量表。溃疡类型以下肢静脉性溃疡为主,下肢溃疡表面积均小于54 cm2。除一项研究17外,所有其他研究的入选标准均反映了伤口大小。

在调查布洛芬泡沫的7项研究中,有6项研究显示,与安慰剂或标准治疗相比,伤口相关性疼痛的减轻具有统计学意义;剩下的一项研究显示,与标准治疗相比,伤口相关性疼痛有所减轻。所有研究中布洛芬的剂量均相同(0.5 mg/cm2 =112.5 mg),但有一项研究16未报告剂量。一半的研究比较了布洛芬泡沫与安慰剂,另一半比较了标准治疗。尽管本综述中一半的研究样本量较大(范围:120-835),但一些研究的受试者少于25例。17,18 这些小型研究没有足够的功效显示差异,可能导致第II类错误。仅4项有关布洛芬的研究报告了先验样本量计算。16,19-21

总体而言,由于未包含随机化方法、分配隐藏、失访、意向治疗分析、设盲和基线可比性等重要因素,方法学的报告情况较差。Gottrup等人21是唯一根据推荐标准8-10得当报告方法学的研究组,因此可以更准确地确定其研究的偏倚水平。

布洛芬组7项研究中的5项报告了专门与干预药物相关的不良事件。16,17,19-21 这些不良事件包括感染、湿疹、水疱、疼痛增加和伤口大小增大、红斑、出血和溃疡周围恶化等局部反应。在一项研究中,未报告研究期间与布洛芬泡沫相关的不良事件,18 最终研究22根本未报告不良反应。

由于三项相关研究的样本量较小,因此尚不清楚外用吗啡凝胶是否能有效减轻与下肢静脉性、动脉性或混合性溃疡相关的疼痛。吗啡凝胶(硫酸吗啡注射液与水凝胶混合物)通常每日涂抹于疼痛的慢性或姑息性伤口以缓解疼痛,23,24但通常需要每日涂抹两次。25所有有关吗啡凝胶的研究均使用安慰剂凝胶作为对照。25-27 报告了一系列剂量,包括0.5 mg/cm2、

10 mg和0.5%/g。所有这些研究的受试者均少于25例(表

1),因此可能存在第II类错误。无研究报告先验进行样本量计算,方法学的报告情况较差。

所有三项有关吗啡凝胶的研究均报告了与干预相关的不良事件。25-27 局部不良反应包括瘙痒、灼痛、刺痛、湿疹、止痛无效、感染。全身不良反应有头晕、恶心、呕吐、嗜睡等。

类别2:外用局部麻醉药

12项研究调查了利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏(EMLA 5%)在慢性下肢溃疡清创中的作用(表2),1项研究28调查了利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏治疗慢性下肢溃疡相关慢性疼痛的作用。除2项研究29,30外,疼痛是所有研究的主要结局,视觉模拟量表是使用的主要疼痛评估工具。该组研究的结果表明,除两项研究31,32外,在所有其他研究中,利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏均能有效减轻慢性下肢溃疡清创导致的伤口相关性疼痛,但除一项研究28外,所有其他研究中方法学的报告情况均较差。

在该组纳入的研究中,下肢静脉性溃疡也是主要的下肢溃疡类型。在大多数研究中,每例慢性下肢溃疡的表面积均小于50 cm2(86%)。

9项研究比较了5%利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏与外用安慰剂、29,33-35 10%利多卡因喷雾剂、31 2%利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏、32 或一氧化二氮-氧气混合物吸入;36,37 一项研究中的对照未知。38 一项RCT比较了利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏与常规伤口护理。28 一项回顾性、观察性研究39在1084例存在各种伤口类型(包括慢性下肢溃疡)的受试者样本中评价了5%利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏的有效性。乳膏的总涂抹次数范围为1至28次,大多数研究在清创前30分钟涂抹。两项研究将涂抹时间延长至45分钟,29,35 两项研究延长至60分钟。39,40 一项研究涂抹利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏仅10分钟31,另一项研究重复4周每日给予24小时的剂量。28 在69%的研究中,最大剂量为10 g。28,30,32-35,37,40 然而,在Blanke和Hallern进行的病历审查39中,一些受试者接受了高达150 g的利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏外用给药。

测量5%和2%乳膏中利多卡因和丙胺卡因血药浓度的3项研究结果表明,为清创而进行重复涂抹后未达到毒性水平。30,32,33 在Enander等人的研究32 中,下肢动脉性溃疡患者的血药浓度高于下肢静脉性溃疡患者。然而,Effendy等人30更近期的一项研究不支持这一结果,他们的研究表明溃疡类型对血药浓度没有任何影响,但下肢溃疡大小确实有显著影响。

超过一半的研究报告了轻微不良反应,主要是局部皮肤反应,如灼热、苍白、红斑、瘙痒、刺痛和水肿。28,29,32-34,37-39 未报告利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏的重大不良反应。

在大多数研究中,样本量较小(范围:10-110),该组13项研究中有9项研究的受试者少于70例。只有两项研究报告了先验进行样本量计算。35,37 然而,在关于清创的研究中,除了两项外,清创期间的疼痛均出现具有统计学意义的减轻,31,32 而一项研究则观察到在敷料更换期间和之后,慢性伤口相关性疼痛出现具有统计学意义的减轻。28

方法学质量评估

本综述纳入的23项研究中有19项是RCT。有关外用镇痛药和麻醉药的RCT的方法学质量分别见表3和表4。

两项研究(一项在外用镇痛药组17,一项在外用局部麻醉药组36)是交叉研究。外用局部麻醉药组30中的一项研究是准实验研究,这是唯一报告基线可比性的研究。30 一项研究采用交叉设计比较了布洛芬泡沫与安慰剂泡沫作为疼痛性慢性下肢溃疡的接触性敷料;17 另一项研究比较了利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏和一氧化二氮-氧气混合物吸入36作为清创前慢性下肢溃疡的治疗方法。两项RCT32,33包括小型初步观察性研究的数据。一项研究调查了利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏的涂抹次数33,另一项调查了血药浓度。32

表3.随机对照试验的方法学质量评估:外用镇痛药

缩略词:CLU,慢性下肢溃疡;ITT,意向治疗;NR,未报告;RCT,随机对照试验。

讨论

这些结果表明布洛芬泡沫可成功减轻慢性下肢溃疡疼痛;但是,没有足够的数据表明涂抹吗啡凝胶具有相似的有效性。利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏是外用麻醉药组所有研究中使用的局部麻醉药,在所有研究中,除一项研究外,其均涂抹于慢性下肢溃疡部位,以预防与清创相关的急性疼痛。这些结果均表明,利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏用于此目的时有效。一项研究表明,当作为接触性敷料每日使用时,利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏也可有效减轻慢性下肢溃疡相关的慢性疼痛。

本综述中的大多数研究不符合CONSORT报告要求8,因此通常无法确定选择偏倚、检出偏倚和实施偏倚的风险。大多数文章中提供的信息不足,导致得出试验质量较差的假设,但无法对其进行真正评估。41 然而,只有43%的RCT对受试者和研究者设盲,12%报告了如何生成其分配序列,只有30%报告了分配隐藏。失访偏倚的风险也很高,不到30%的RCT报告了在意向治疗分析中是否纳入受试者,不到15%的RCT报告了受试者退出。该组中一项研究的脱落率为29%。此外,本综述纳入的大多数研究发表时间均超过5年,不过也认识到仅重视近期证据而非有力证据可能会误导实践。42

为了提高临床试验的效度,适当的样本量很重要。小样本量增加了出现第II类错误的可能性,导致临床环境中结果的适用性和实用性降低。43 相反,样本量较大的临床试验可能导致资源浪费,由于低应答率和难以维持数据质量而降低效度或准确性。43 在本综述中,23项研究中有14项的样本量小于100。所有3项调查吗啡凝胶的研究样本量均小于25,7项调查布洛芬泡沫的研究中有2项、13项调查利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏中有9项也是如此。尽管本分析中纳入的回顾性、观察性病历39审查的样本量非常大,但研究设计存在仅样本量无法克服的其他固有方法学局限性。

在本综述中,与外用镇痛药和外用局部麻醉药用于缓解慢性下肢溃疡疼痛相关的研究结果表明,外用药物(吗啡凝胶除外)是有效的。本综述对知识体系的贡献为,迄今为止,用作慢性下肢溃疡疼痛接触性敷料的唯一外用制剂是布洛芬泡沫和吗啡凝胶,很少是利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏。几十年来,利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏一直是最主要和使用时间最长的外用止痛药,用于缓解与慢性下肢溃疡清创相关的手术疼痛。直到最近,才对其作为缓解慢性伤口相关性疼痛的接触性敷料进行了研究。

表4.随机对照试验的方法学质量评估:外用局部麻醉药

缩略词:CLU,慢性下肢溃疡;NR,未报告;MMS,简明精神状态量表评分;RCT,随机对照试验;VAS,视觉模拟量表;VRS,口头评定量表。

局限性

语言偏倚是本综述的一个局限性,发表偏倚尚不清楚。此外,与试验研究者的访谈可能有助于更准确地评估研究质量;41 但没有进行。

文献缺口

当口服镇痛无效或会导致严重不良反应时,外用镇痛药和麻醉药提供了一种重要的疼痛缓解替代方案。审视这些药物用于治疗慢性下肢溃疡疼痛的研究数量有限。现有研究主要受到样本量小和方法学质量不佳的限制。现有文献中概述的方法学报告信息不佳,不利于对方法学质量进行准确评估。

现有的最有力证据支持在清创之前间歇性、短期涂抹利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏来缓解手术疼痛,已证实其具有系统安全性,不会对伤口愈合产生负面影响。利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏在清创中具有有效性的证据,以及将其用作接触性敷料的一项初步RCT,表明其可有效治疗慢性下肢溃疡患者的慢性疼痛。该策略将在更长时间内减轻伤口相关性疼痛,反过来可能对伤口愈合和健康相关生活质量产生积极影响。

结论

本综述识别出了使用外用镇痛药和外用局部麻醉药治疗疼痛性慢性下肢溃疡的有限、不一致的证据。尽管尚需要进一步研究使用外用药物缓解慢性伤口相关性疼痛的情况,但利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏和布洛芬泡沫似乎是减少慢性下肢溃疡导致的伤口相关性疼痛的有效药物。有效使用外用药物可减少对于全身性疼痛缓解药物的需求,减轻潜在不良反应。

实践提示

• 与慢性下肢溃疡相关的疼痛可能很严重,并影响伤口愈合和健康相关生活质量。

• 外用5%利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏可有效缓解慢性下肢溃疡清创过程中的疼痛。

• 外用5%利多卡因/丙胺卡因乳膏和布洛芬泡沫可能是用于替代口服止痛药来治疗慢性伤口相关性疼痛的有前景方案。

• 使用外用镇痛药和局部麻醉药治疗疼痛性慢性下肢溃疡的证据不一致。因此需要进一步研究。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Anne Purcell*

PhD, NP, RN,

Nurse Practitioner Wound Management, Central Coast Local Health District Community Nursing Service, Wyong, New South Wales, Australia

Email anne.purcell@health.nsw.gov.au

Thomas Buckley

PhD, RN,

Associate Professor, Susan Wakil School of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Jennie King

PhD, RN,

Nursing & Midwifery Research Consultant, Nursing & Midwifery Directorate, Central Coast Local Health District, Gosford, New South Wales, Australia, Clinical Senior Lecturer, Susan Wakil School of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Wendy Moyle

PhD, RN,

Professor, Program Director, Healthcare Practice and Survivorship, Menzies Health Institute, Southport, Queensland, Australia

Andrea P. Marshall

PhD, RN,

Professor of Acute and Complex Care Nursing, Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service Nursing and Midwifery Education and Research Unit, Southport, Queensland, Australia

* Corresponding author

References

- Briggs M, Nelson EA, Martyn-St James M. Topical agents or dressings for pain in venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012(11):CD001177.

- Vanscheidt W, Sadjadi Z, Lillieborg S. EMLA anesthetic cream for sharp leg ulcer debridement: a review of the clinical evidence for analgesia efficacy and tolerability. Eur J Emerg Med 2001;11:90-6.

- Pare G, Kitsiou S. Methods for literature reviews. In: Lau F, Kuziemsky C, eds. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-Based Approach. Victoria, BC, Canada: University of Victoria; 2017:157-80.

- Australian Department of Health Therapeutic Goods Administration. Public Summary. 2018. www.ebs.tga.gov.au/servlet/xmlmillr6?dbid=ebs/PublicHTML/pdfStore.nsf&docid=FD3D09E3800470D2CA 25821F003C9C0C&agid=(PrintDetailsPublic). Last accessed February 19, 2020.

- Food and Drug Administration. Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. 40th ed. 2020. www.fda.gov/media/71474/download. Last accessed February 19, 2020.

- Weinberg L, Peake B, Tan C, Nikfarjam M. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of lignocaine: a review. World J Anesthesiol 2015;4(2):17-29.

- Kumar M, Chawla R, Goyal M. Topical anesthesia. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2015;31(4):450-6.

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, Group C. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Br Med J 2010;340:c332.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklists. 2018. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists. Last accessed February 4, 2020.

- Cochrane Wounds. Table 8.5.d: criteria for judging risk of bias in the ‘risk of bias’ assessment tool. 2011. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_8/table_8_5_d_criteria_for_judging_risk_of_bias_in_the_risk_of.htm. Last accessed February 4, 2020.

- Johns BA. EMLA cream for the debridement of venous leg ulcers. J Fam Pract 1999;48(5):332.

- Johnson C, Repper J. A double blind placebo controlled study of lidocaine/prilocaine cream (EMLA 5%) used as a topical analgesic for cleansing and redressing of leg ulcers. Astra Pain Control AB (Confidential Report); 1992.

- Larsson-Stymne B, Rostein A, Widman M. An open clinical study on plasma concentrations of lidocaine and prilocaine after application of EMLA 5% cream to leg ulcers. Clin Dermatol 2000;1990(22-25 May).

- Slawson D. How effective is an eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA) cream in reducing the pain of repeated mechanical debridement of venous leg ulcers? Evid Based Pract 1999;2(5).

- Wanger L, Eriksson G, Karlsson A. Analgesic effect and local reactions of repeated application of EMLA lidocaine prilocaine cream for the cleansing of leg ulcers. Paper presented at the Clinical Dermatology in the Year 2000; London, England.

- Romanelli M, Dini V, Polignano R, Bonadeo P, Maggio G. Ibuprofen slow-release foam dressing reduces wound pain in painful exuding wounds: preliminary findings from an international real-life study. J Dermatological Treat 2009;20(1):19-26.

- Jorgensen B, Friis GJ, Gottrup F. Pain and quality of life for patients with venous leg ulcers: proof of concept of the efficacy of Biatain-Ibu, a new pain reducing wound dressing. Wound Repair Regen 2006;14(3):233-9.

- Sibbald RG, Coutts P, Fierheller M, Woo K. A pilot (real-life) randomized clinical evaluation of a pain-relieving foam dressing: (ibuprofen-foam versus local best practice). Int Wound J 2007;4 Suppl 1:16-23.

- Domenech RPi, Romanelli M, Tsiftsis DD, et al. Effect of an ibuprofen-releasing foam dressing on wound pain: a real-life RCT. J Wound Care 2008;17(8):342-8.

- Fogh K, Andersen MB, Bischoff-Mikkelsen M, et al. Clinically relevant pain relief with an ibuprofen-releasing foam dressing: results from a randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical trial in exuding, painful venous leg ulcers. Wound Repair Regen 2012;20(6):815-21.

- Gottrup F, Jorgensen B, Karlsmark T, et al. Reducing wound pain in venous leg ulcers with Biatain Ibu: a randomized, controlled double-blind clinical investigation on the performance and safety. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16(5):615-25.

- Arapoglou V, Katsenis K, Syrigos KN, et al. Analgesic efficacy of an ibuprofen-releasing foam dressing compared with local best practice for painful exuding wounds. J Wound Care 2011;20(7):319-20, 322-5.

- Northamptonshire Healthcare. MMG029 Guidelines for the Use of Topical Morphine for Painful Skin Ulcers in Specialist Palliative Care. November 2019. www.nhft.nhs.uk/download.cfm?doc=docm93jijm4n1573. Last accessed February 19, 2020.

- Shanmugam VK, Couch KS, McNish S, Amdur RL. Relationship between opioid treatment and rate of healing in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2017;25(1):120-30.

- Jansen MM, van der Horst JC, van der Valk PG, Kuks PF, Zylicz Z, van Sorge AA. Pain-relieving properties of topically applied morphine on arterial leg ulcers: a pilot study. J Wound Care 2009;18(7):306-11.

- Bastami S, Frodin T, Ahlner J, Uppugunduri S. Topical morphine gel in the treatment of painful leg ulcers, a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial: a pilot study. Int Wound J 2012;9(4):419-27.

- Vernassiere C, Cornet C, Trechot P, et al. Study to determine the efficacy of topical morphine on painful chronic skin ulcers. J Wound Care 2005;14(6):289-93.

- Purcell A, Buckley T, Fethney J, King J, Moyle W, Marshall AP. The effectiveness of EMLA as a primary dressing on painful chronic leg ulcers—a pilot randomized controlled trial. Adv Skin Wound Care 2017;30(8):354-63.

- Lok C, Paul C, Amblard P, et al. EMLA cream as a topical anesthetic for the repeated mechanical debridement of venous leg ulcers: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1999;40(2 Pt 1):208-13.

- Effendy I, Gelber A, Lehmann P, Huledal G, Lillieborg S. Plasma concentrations and analgesic efficacy of lidocaine and prilocaine in leg ulcer-related pain during daily application of lidocaine-prilocaine cream (EMLA) for 10 days. Br J Dermatol 2015;173(1):259-61.

- Cuomo R, D’Aniello C, Grimaldi L, et al. EMLA and lidocaine spray: a comparison for surgical debridement in venous leg ulcers. Adv Wound Care 2015;4(6):358-61.

- Enander M, Nilsen T, Lillieborg S. Plasma concentrations and analgesic effect of EMLA (lidocaine/prilocaine) cream for the cleansing of leg ulcers. Acta Derm Venereol 1990;70(3):227-30.

- Holm J, Andren B, Gafford K. Pain control in the surgical debridement of leg ulcers by the use of a topical lidocaine-prilocaine cream, EMLA. Acta Derm Venereol 1990;70(2):132-6.

- Rosenthal D, Murphy S, Gottschalk R, Baxter M, Lycka B, Nevin K. Using a topical anesthetic cream to reduce pain during sharp debridement of chronic leg ulcers. J Wound Care 2001;10(1):503-5.

- Agrifoglio G, Domanin M, Baggio E, et al. EMLA anesthetic cream for sharp debridement of venous leg ulcers: a double masked placebo controlled study. Phlebology 2000;15(2):81-3.

- Traber J, Held U, Signer M, Huebner T, Arndt S, Neff TA. Analgesic efficacy of equimolar 50% nitrous oxide/oxygen gas premix (Kalinox®) as compared with a 5% eutectic mixture of lidocaine/prilocaine (EMLA®) in chronic leg ulcer debridement. Int Wound J 2017;14(4):606-15.

- Claeys A, Gaudy-Marqueste C, Pauly V, et al. Management of pain associated with debridement of leg ulcers: a randomized, multicentre, pilot study comparing nitrous oxide-oxygen mixture inhalation and lidocaine-prilocaine cream. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25(2):138-44.

- Hansson C, Holm J, Lillieborg S, Syren A. Repeated treatment with lidocaine/prilocaine cream (EMLA) as a topical anesthetic for the cleansing of venous leg ulcers. A controlled study. Acta Derm Venereol 1993;73(3):231-3.

- Blanke W, Hallern B. Sharp wound debridement in local anaesthesia using EMLA cream: 6 years’ experience in 1084 patients. Eur J Emerg Med 2003;10(3):229-31.

- Holst RG, Kristofferson A. Lidocaine-prilocaine cream (EMLA cream) as a topical anesthetic for the cleansing of leg ulcers. The effect of length of application time. Eur J Dermatol 1998;8(4):245-7.

- Soares HP, Daniels S, Kumar A, et al. Bad reporting does not mean bad methods for randomized trials: observational study of randomized controlled trials performed by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Br Med J 2004;328(7430):22-4.

- Shorten A. When is the evidence too old? BMJ Blogs. 2013. https://blogs.bmj.com/ebn/2013/09/26/when-is-the-evidence-too-old. Last accessed February 4, 2019.

- Kumar GS. Importance of sample size in clinical trials. Int J Clin Exp Physiol 2014;1(1):10-2.