Volume 40 Number 2

Therapeutic patient education; A multifaceted approach to healthcare

Laurence Lataillade and Laurent Chabal

Keywords Wound care, Therapeutic patient education, person-centred care, stomal therapy

For referencing Lataillade L and Chabal L . Therapeutic patient education; A multifaceted approach to healthcare. WCET® Journal 2020;40(2):35-42.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.2.35-42

Abstract

This contribution presents a literature review of therapeutic patient education (TPE) in addition to providing a summary of an oral presentation given by two wound care specialists at a European Congress. It relates this to models of care in nursing science and to other research that contributes to this approach at the core of healthcare practice.

Therapeutic patient education: an introduction to its practical application in patients with stomas and/or wounds

Up until 1970, educational approaches were rare and limited to a few isolated interventions such as the ‘manual for diabetics’. In 1972, Leona Miller, an American doctor, demonstrated the positive effects of patient education. Using a pedagogical approach, she enabled patients from under-resourced areas of Los Angeles living with diabetes to control their pathology and improve their independence by relying on less medication1.

In 1975, Professor Jean Philippe Assal, a diabetologist from Geneva, Switzerland, adopted this concept and created a department for the treatment and education of diabetes at Geneva University Hospitals. He created an innovative, interdisciplinary team consisting of nurses, physicians, dieticians, psychologists, caregivers, art therapists and physiotherapists, all with the goal of encouraging patient engagement in their learning2. The team was inspired by person-centred theories developed by Carl Rogers3, work by Kübler-Ross on the grief process4, contributions from Geneva on education science in adult learning, and work on the conceptions of learners of didactics and epistemology of science in Geneva.

Since then, therapeutic education of patients (TPE) has been developed for patients with different chronic diseases and disorders, such as asthma, pulmonary insufficiency, cancer, inflammatory bowel disease and, in particular, for patients with stomas and/or wounds. The aim of TPE is to assist patients and caregivers to better understand the nature of the disease a person has, the treatment strategies required and to help patients achieve a greater level of individual autonomy in how they manage and cope with their disease.

Definition of therapeutic patient education (TPE)

According to the World Health Organization (1998), TPE is education managed by healthcare providers trained in the education of patients, and is designed to enable a patient (or a group of patients and families) to manage the treatment of their condition and prevent avoidable complications, while maintaining or improving quality of life. Its principal purpose is to produce a therapeutic effect additional to that of all other interventions – pharmacological, physical therapy, etc. Therapeutic patient education is designed therefore to train patients in the skills of self-managing or adapting treatment to their particular chronic disease, and in coping processes and skills. It should also contribute to reducing the cost of long-term care to patients and to society. It is essential to the efficient self-management and to the quality of care of all long-term diseases or conditions, although acutely ill patients should not be excluded from its benefits.

Thus, “TPE should enable patients to acquire and maintain abilities that allow them to optimally manage their lives with their disease. It is therefore a continuous process that should be integrated into healthcare”5.

The premise of TPE as a healthcare approach is that it places the patient(s) or the caregiver(s) at the centre of the healthcare provider patient relationship, acknowledging them as an integral partner in healthcare processes6–8. The cornerstone of this approach is that the patient has knowledge, skills and experiences that must be valued, encouraged, stimulated and/or explored. As for health practitioners, they need to recognise and highlight the patient’s knowledge about themselves and capabilities, which requires the health practitioner to adapt their own position to care provision and education. Healthcare providers often tend to talk to patients about their disease rather than train them in daily management processes to assist patients to better manage their condition5. As Gottlieb explains9,10, it is more than a change in behaviour but a paradigmatic change that implores the practitioner to rely on the patient’s strengths rather than remedying their deficiencies and going further than Orem’s Model11 proposed.

TPE is a model of education and support for people living with one or more chronic diseases. The goal is to support the person being cared for by engaging them with their care by means of an educational program which makes sense for them and, in doing so, reduces the risk of complications12 and improves their quality of life. The tools of TPE promote a true collaboration between the patient and the healthcare practitioner. This requires a holistic, integrative and interdisciplinary approach13.

What is the objective of TPE? What position should practitioners adopt?

The goal for practitioners who employ TPE is to enable their patients to become independent in their care processes and to improve their quality of life. Nevertheless, patient goals are not always the same at every juncture. For example, the sudden arrival of the disease, such as a colonic cancer and the formation of a stoma, which is often a consequence thereof, have a major impact on the patient’s life. The ostomy patient goes through many emotional processes that are often profound and intense which sometimes overwhelms them completely.

Therapeutic patient education aims to support the patient in the stages and process of this emotional adjustment so that they can better adapt14 to and accommodate their disease and stoma in their day-to-day life. The goal is for the patient to acquire skills for managing their stoma and treatment as well as psychosocial skills to integrate their stoma into their daily life.

The challenge for practitioners is to reconcile these two types of learning in the TPE program while taking into account the difficulties encountered by the patient and their learning needs. A therapeutic relationship based on mutual trust and partnership is an indispensable condition for this educational process. In the framework of this alliance, the emphasis is placed on a relationship of moral equivalence between the patient and practitioner15.

The first educational stage within the TPE framework constitutes encouraging and making space for the patient to express themselves in order to reveal and agree on their particular needs which may not always be evident to either the patient or the health practitioner.

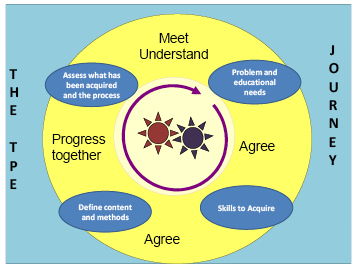

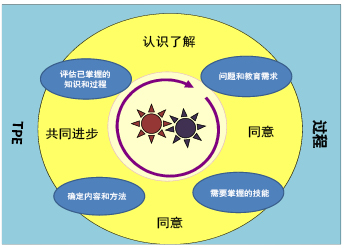

Figure 1. The TPE journey schema

In the TPE journey schema (the proposed Geneva TPE model), loosely translated from Lasserre Moutet et al.16 (Figure 1), the schema describes the following concepts:

- The two cog wheels in the middle represent the patient and the practitioner, both engaged in active movement. They both possess a specific knowledge base of their own. The practitioner possesses scientific knowledge, clinical skills and their clinical experience with other patients who have faced similar healthcare conditions; the patient possesses their individual lived experience with their disease and their treatment in addition to their own knowledge. Although this relationship is, by nature, asymmetric, it is nevertheless not ranked in terms of knowledge. The practitioner is a mediator who supports the patient in the process of transforming their knowledge to better understand their disease, consequences of the disease process and remedial medical interventions. For these gears to work, the rhythm must be adjusted. The first part of the TPE journey is especially important in upholding this engagement: the patient and practitioner must agree on the problem, revealing the reality of the situations that the patient encounters on a daily basis. For the practitioner, this involves developing a genuine interest in the patient and their life story with their disease.

- On the basis of this common understanding, educational needs, practical skills and competencies to be acquired by the patient will be elucidated in order for the patient to be able to overcome their difficulties or resolve their day-to-day problems.

- Once the goals are defined in conjunction with the patient, the strategies employed will lead the patient to encounter new ideas, to experience a new perspective on their situation, and to find alternatives to organise their daily life.

- Finally, the journey and the changes made will be evaluated jointly in order to make adjustments and continue the process.

This four-step approach can be carried out during one or more consultations.

What kind of therapeutic education should we use for patients with stomas?

Patients with stomas are confronted with physical changes and, often, a chronic disease17,18 which restricts their ability to envision a new reality for their life. One of the key roles of the stomal therapy nurse is to help the patient engage in suitable learning that will allow them to adapt, step by step, to a new life balance.

Whether the stoma is temporary or permanent, it is a shock and affects every aspect of the patient’s life: social and professional life, emotional and family life, personal identity and self-esteem. In situations where the stoma is temporary, it is often seen as a major obstacle in the person’s life for the period of time with which they live with the stoma. Once the intestine is reconnected, some patients dread that they will need a new stoma, which is indeed a possibility.

With the goal of patient independence with respect to the management of their care needs or, when this is not possible for the ostomy patient, for caregivers, stomal therapy nurses integrate TPE as a continuous process of comprehension of the patient’s lived experience and create a partnership, teaching and informing the patient throughout all stages of treatment – pre-operative, postoperative, rehabilitation, home care and short- or long-term follow-up.

This patient’s education focuses on different themes depending on the patient’s needs. For example, organisational aspects related to the stoma (care, changing the appliance, balanced digestion, food safety, etc.) which necessitate self-care. Some self-adjustment difficulties, such as a distorted self-image, low self-esteem and additional psycho-emotional implications19–21 and difficulty talking about the disease or stoma with their social circle, or resuming sexual activity, will most likely require the development of psychosocial coping skills and competencies to facilitate adaptation. The practitioner can thus apply their knowledge, clinical know-how and interpersonal skills to find appropriate teaching strategies for the patient or caregiver’s learning styles, all the while respecting/integrating patient’s limits, fears, and any resistance in order to lead them through each step of the process. Ultimately, successful integration of these processes will allow patients to perform their own self-care and adapt to their life with the ostomy and sometimes their chronic disease.

What stages do ostomy patients go through and how can we help them overcome them?

According to Selder22, the lived experience of a chronic disease is akin to a journey through a disturbed reality that is full of uncertainty and which, ultimately, leads to a restructuring of that reality.

In order to mobilise the patient’s resources, by working on their resilience23,24, consilience (coping skills)25 and empowerment26 skills, practitioners must take it upon themselves to meet the person and understand their representations, values and beliefs27,28 in order to incorporate them into their healthcare. These aspects, which are very much linked to the socio-cultural and religious context that the individual has assimilated, must also be considered in order to integrate them into the care provided to them29,30.

According to Bandura31,32, patients’ sense of self-efficacy relies on four aspects: personal mastery, modelling, social learning, and their physiological and emotional state. This generates three types of positive effects in patients with a good level of self-efficacy: the first relates to the choice of behaviours adopted, the second on the persistence of behaviours adopted, and the third on their great resilience in the face of unforeseen events and difficulties. Nurses who practise TPE will be able to mobilise, through their healthcare interventions, these four aspects of TPE for the purpose of inducing these three types of effects in the patient.

According to Diclemente et al.33, behavioural life changes can only be carried out in stages. In stomal therapy, these patient-centred approaches begin in the pre-operative stage where explanations are provided to the patient (and family where possible) on the potential need for the stoma, the surgical procedure and postoperative care (WCET® recommendation 3.1.2, SOE=B+29), even though the ostomy has not yet been confirmed. These recommendations have been adopted by the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society® (WOCN®)34.

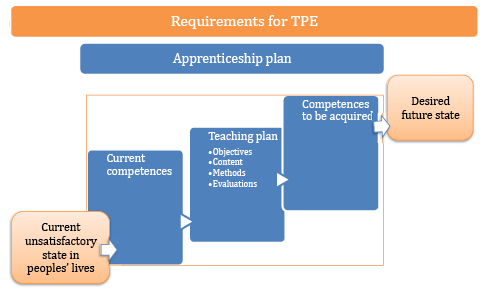

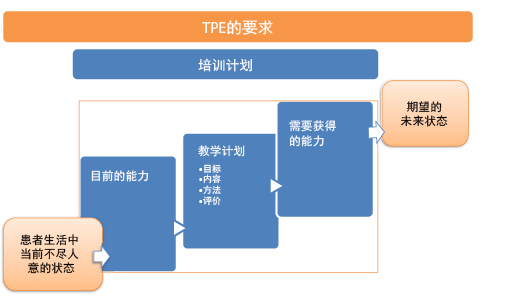

The schema, adapted and loosely translated from Martin and Savary35, describes the main steps of the learning process that need to be met and nurtured (Figure 2). Depending on the age of the patient, the knowledge, tools, and processes employed in adult education, TPE requirements may be necessary components to mobilise in order to attain them36,37. Other strategies will need to be adopted for younger populations, particularly with respect to adolescents38,39.

Figure 2. TPE requirements

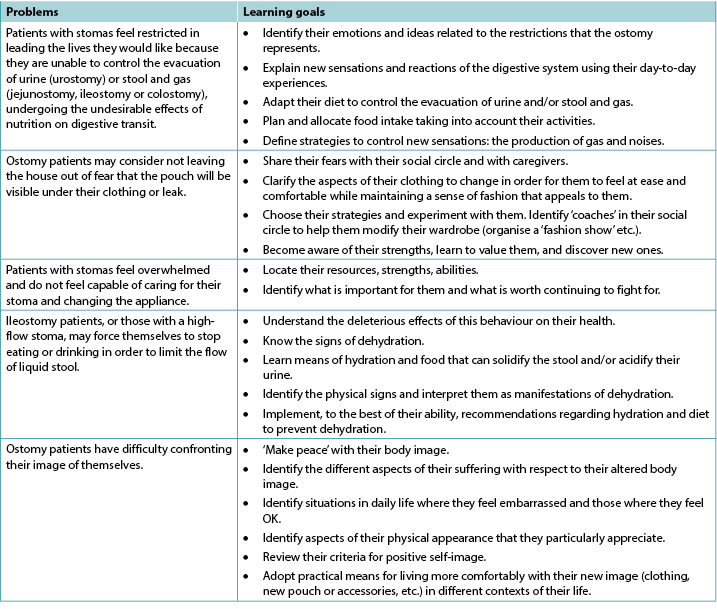

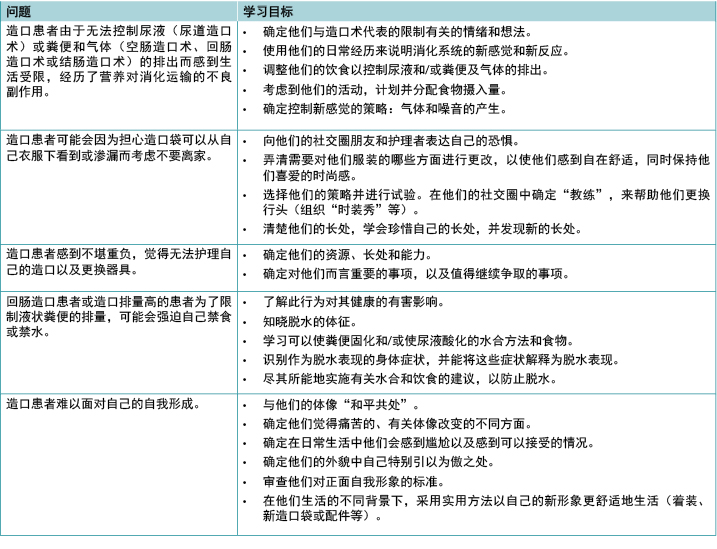

Examples of problems and goals in the therapeutic education of patients with stomas

These problems and instructional goals may apply for patients with incontinent ostomies, which are reflective of the most encountered scenarios (Table 1).

Table 1

In the case of patients with other, less common types of ostomy, like those with continent ostomies or nutritional support ostomies40,41, some of these items are still applicable and/or will need to be adapted to their particular situation; additional and more specific problems may apply. This is also the case for patients with enterocutaneous fistulae42.

In some situations, whether due to disgust, refusal, denial and/or disability (motor function, cerebral, psycho-emotional or psychiatric), the ostomy patient may not be able to undergo some or all of these processes of learning and empowerment43. This can be a short-term, medium-term or sometimes long-term problem. In these instances, recourse to a caregiver, whether a practitioner or a close relative, should be envisaged and organised. The educational process necessary for their empowerment must be carried out in a relatively similar manner with a view on promoting patient enabling to the maximum extent possible that allows the ostomy patient to return home. To the latter must be added supportive communication and management of and potential changes to interpersonal relationships and, potentially, to intimate relationships between the patients and their partners. Such changes can be generated by applying the principles of TPE, and this type of care and will need to be regularly re-evaluated and taken into consideration with a holistic approach to the patient and their respective situations.

These processes are even more complicated for patients who live alone at home, and even more so if they are elderly, as this can call their discharge home into question as well as their ability to remain at home. The need for strong communication relays and networks to be implemented in these circumstances recalls the advice offered within the 2012 American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) report45,46.

Lastly, the ostomy patient will occasionally find themselves with more than one stoma, all of which may be permanent (Figures 3 and 4). From our experience, these complex situations are more frequent than they were previously and are often related to malignant pathology.

Figure 3. Example of a person with a permanent left colostomy and a trans-ileal cutaneous ureterostomy (Bricker’s intervention) with purple urine bag syndrome47.

Figure 4. Example of a postoperative patient several days later with a temporary colostomy and a protective ileostomy. Digestive continuity would be restored in 9 months over two interventions, commencing with the downstream ostomy before the upstream ostomy, over an interval of a few weeks.

Insights and further information relating to patients with chronic wounds

Contrary to some preconceptions, stomal therapy is not solely concerned with the care of ostomy patients, even though the usage of the original term enterostomal therapist (ET)48 may lead to confusion. Indeed, the full Enterostomal Therapist Nursing Education Program (ETNEP)49 includes providing healthcare for people with wounds, people with continence disorders, those with enterocutaneous fistulae and, in some schools, for those with mastectomies. That said, wound care specialisation has become a specialist service unto itself and many ETs or stomal therapy nurses collaborate closely with wound specialists. It is important to note that these aspects of patient education are specified in the European curriculum for nurses specialising in wound care (Units 3 & 4)50–52.

In the literature, in reference to education provided to patients with wounds, knowledge has been described as a process of self-management, particularly among individuals living with a chronic disease such as a leg ulcer53. For education to be effective, the patient must acquire a perceived benefit from the changes that their involvement in the preventive activities proposed could generate. Physical, or emotional, benefits will reinforce the positive effects of the advice given54.

The benefit of using a multimedia teaching approach lies in the combination of methods for transmitting information. This helps resolve the problems encountered by the patient but also reinforces the information they are provided with55,56.

Numerous Cochrane Systematic Reviews have been carried out regarding patients with venous ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers and pressure injuries. They have revealed that:

- For patients with leg ulcers, there is not enough research available to assess strategies for supporting patients that would increase their adherence /compliance, despite the fact that compliance with compression is recognised as an important factor in preventing leg ulcer recurrence57.

- In relation to diabetic patients, there is not enough evidence to say that education – in the absence of other preventive measures – is sufficient to reduce the occurrence of foot lesions and foot/lower limb amputations58.

- Finally, as for pressure injuries, the authors have noted that the idea of patient involvement remains vague and includes a significant number of factors which vary and include a wide range of interventions and possible activities. At the same time, they clarify that this involvement in care, such as the respect of the rights of the patient, are important values which could play a role in their healthcare. This involvement could have the benefit of improving their motivation and knowledge in relation to their health. In addition, such involvement could entail an increase in their ability to manage their disease and to take care of themselves, thus improving their sense of security and enabling them to have better results when it comes to improving their health59.

As for patients with cancerous wounds, the European Oncology Nursing Society recommendations note the existence of scales for the evaluation of symptoms for the typology of these wounds, allowing for early detection of associated complications, as well as the reduction of care-related costs and of equipment used in healthcare, all the while improving patient involvement. Indeed, some of the tools described could be suggested to patients for them to use to assist with managing their condition60. In order for this to happen, education on their use will be necessary, despite the fact that these people may have lost confidence in themselves, their treatment, and their healthcare teams; even though their disease may have improved, their wounds still serve as visible stigmas of their disease.

Conclusion

Therapeutic education is the cornerstone of interventions conducted with individuals with chronic disease, or in chronic conditions, with the goal of health-related promotion, prevention and education. It is a fundamental activity that cuts across all the fields of the specialisation in stomal therapy. As every situation is unique, therapeutic education enables practitioners to develop skills in this area to improve the provision of care. It also incites us to innovate, be creative, adapt, and to think outside the box in order to find other interventional strategies; it also requires us to show humility, which may lead us to ask for help via our professional networks nationally and/or internationally.

According to Adams61, TPE remains a vast area of interventions in which the utility of educational interventions in improving healthcare impacts are still under discussion. However, the results of studies are still too limited to support their evidence. For other authors, the efficacy has, to date, been borne out by the research. For many hospitals, it is reportedly a cost-saving measure, as it enables shorter hospital stays and reduces the number of complications62–66.

Lastly, while the educational process starts at the hospital, it is followed up in both outpatient and home care services. In this sense, the implementation and maintenance of communication relays will be primordial in ensuring continuity of care, coherence and coordination of the processes undertaken as well as those of future stages that will be collaboratively decided upon. The involvement of family caregivers in these processes, with the consent of the patient and their relatives, is important. They serve as resources that cannot be neglected, even though their involvement may generate other issues that must be accounted for.

The training of healthcare professionals, particularly nurses, in the application of TPE will reinforce their expertise and efficiency67 in patient education, with the knowledge that every situation will push them to find new strategies and skills to overcome the challenges faced.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The wound section was partially based on notes taken during the University Conference Model (UCM) session68 on the subject. This session took place at the 2017 Congress of the European Wound Management Association (EWMA) in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and was presented by Julie Jordan O’Brien, Clinical Nurse Specialist Tissue Viability and Véronique Urbaniak, Advanced Practice Nurse69.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

患者治疗教育;一种多面性医疗保健方法

Laurence Lataillade and Laurent Chabal

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.2.35-42

摘要

本文提供了对两位伤口护理专家在欧洲大会上所做口头演讲的总结,并介绍了对患者治疗教育(TPE)的文献综述。本文将患者治疗教育与护理学中的护理模型,以及其他处于医疗保健实践的核心且为这种方法做出贡献的研究相关联。

患者治疗教育:在有造口和/或伤口患者中的实际应用介绍

在1970年以前,教育方法一直很少见,并且仅限于一些孤立的医疗干预,例如“糖尿病患者手册”。1972年,美国医生Leona Miller展示了患者教育的积极效果。通过教学法,她使洛杉矶资源贫乏地区的糖尿病患者可以控制病况,并通过减少药物依赖提高自己的独立性1。

1975年,瑞士日内瓦的糖尿病专家Jean Philippe Assal教授采用了这一概念,在日内瓦大学医院成立了糖尿病治疗和教育部门。他组建了一个创新的跨学科团队,由护士、医师、营养师、心理学家、护理者、艺术治疗师和理疗师组成,其目的是鼓励患者参与他们的学习2。该团队的灵感来自Carl Rogers以人为本的理论3、Kübler-Ross有关悲伤过程的研究4、日内瓦在成人学习教育科学方面的成果,以及日内瓦有关教学法和科学认识论的学习者概念的研究。

从那时起,针对患有不同慢性疾病和病症(如哮喘、肺功能不全、癌症和炎症性肠病)的患者,尤其是有造口和/或伤口的患者,开发了患者治疗教育(TPE)。TPE的目的是帮助患者和护理者更好地了解患者所患疾病的性质和所需的治疗策略,并帮助患者在管理和应对疾病的过程方法上,获得更高水平的个体自主性。

患者治疗教育(TPE)的定义

根据世界卫生组织(1998年)的说法,TPE是一项教育,由接受过患者教育培训的医疗保健提供者管理,旨在使患者(或一组患者和家属)能够管理其疾病治疗,并预防可避免的并发症,同时维持或改善生活质量。其主要目的是产生除所有其他干预(药物治疗、物理疗法等)的疗效之外的额外治疗效果。因此,患者治疗教育还旨在训练患者在自我管理或根据自身特定的慢性疾病调整治疗方面的技能,以及应对过程和技能。它还应有助于降低患者和社会的长期护理成本。它对于高效的自我管理,以及对所有长期疾病或病情的护理质量至关重要,不过不应将急性病患者从其受益群体中排除。

因此,“TPE应使患者获得并维持使他们能够在患病情况下最佳地管理自己的生活的能力。因此这是一个连续的过程,应融入医疗保健中”5。

TPE作为医疗保健方法的前提是,它将患者或护理者置于医疗保健提供者和患者关系的中心,承认他们是医疗保健过程中不可或缺的一部分6-8。这种方法的基石是患者具有必须得到重视、鼓励、刺激和/或探索的知识、技能和经验。对于医疗执业者来说,他们需要认可并强调患者对自身和自身能力的了解,这要求医疗执业者调整个人立场来提供护理和教育。医疗保健提供者通常倾向于与患者谈论他们的疾病,

而不是在日常管理过程中训练患者,以此助其更好地控制病情5。正如Gottlieb的解释9,10,这不仅仅是行为上的改变,更是一种范式上的改变,它要求执业者依靠患者的长处,而非纠正患者的不足,并且超越了Orem提出的“模式”11理论。

TPE是对患有一种或多种慢性疾病的人进行教育和支持的模式。目的是通过被护理者可理解的教育计划使其参与对自身的护理,从而达到支持被护理者的效果,并在这个过程中,减少患并发症的风险12,和改善他们的生活质量。TPE工具促进患者与医疗保健执业者之间的真正合作。这就需要一种整体、综合和跨学科的方法13。

TPE的目标是什么?执业者应该采取什么样的立场?

执业者使用TPE的目标是,使自己的患者在护理过程中变得独立,并改善他们的生活质量。然而,每个特定时刻的患者目标并非一成不变。例如,突然出现的疾病(例如结肠癌)和造口的形成(通常是治疗疾病导致的结果)对患者的生活产生重大影响。造口患者会经历许多情绪过程,这些情绪过程通常深刻强烈,有时会完全淹没患者。

患者治疗教育的目的是在这种情绪调节的阶段和过程中,为患者提供支持,以使他们能够在其日常生活中更好地适应14并接纳其疾病和造口。目标是让患者掌握管理其造口和治疗所需的技能,以及在日常生活中接纳其造口的社会心理技能。

执业者面临的挑战是,在兼顾患者遇到的困难和学习需求的同时,在TPE计划中协调这两种类型的学习。建立在相互信任和伙伴关系基础上的治疗关系,是该教育过程必不可少的条件。在这一联合的框架中,重点放在患者和执业者之间的道德对等关系上15。

TPE框架内的第一个教育阶段,包含鼓励患者表达自我并为患者表达自我提供空间,以便揭示对患者或医疗执业者而言可能并不总是不言自明的患者特殊需求,并就这些需求达成一致。

图1. TPE过程图式

在从Lasserre Moutet等人16的研究中粗略翻译而成(图1)的TPE过程图式(建议的日内瓦TPE模型)中,该图式描述了以下概念:

1. 中间的两个齿轮分别代表患者和执业者,他们都在参与过程的有效运转。他们都拥有自己的特定知识库。执业者拥有科学知识、临床技能和针对有类似病情的其他患者的临床经验;患者除了拥有个人知识外,还拥有关于其疾病和治疗的个人生活经验。尽管这种关系本质上是不对称的,但在知识层面上未进行等级分类。执业者是调解人,在患者转变知识的过程中为其提供支持,以便患者更好地了解自己的疾病、疾病过程的后果以及补救性医疗干预。为了让这些齿轮运转,必须调整节奏。TPE过程的第一部分对于维持这种参与度尤为重要:患者和执业者必须就问题达成一致,揭示患者每天会遇到的现实情况。对于执业者来说,这涉及到对患者及其有关疾病的生活故事产生真正的兴趣。

2. 在这种共识的基础上,将阐明患者需要掌握的教育需求、实践技能和能力,以使其能够克服遇到困难,或解决日常问题。

3. 一旦与患者共同确定了目标,即可采用策略,引导患者了解新想法,体验对自身处境的新视角,并找到替代方案来组织自己的日常生活。

4. 最后,为了进行调整并继续该过程,将对TPE过程和所带来的变化进行共同评价。

可在一次或多次咨询期间执行此四步法。

对于造口患者,我们应使用哪种治疗教育?

造口患者面临着身体变化,并且多数患有慢性疾病17,18,这限制了他们照见自己新的生活现实的能力。造口治疗护士的关键作用之一是,帮助患者进行适当的学习,让他们逐步适应新的生活平衡方式。

无论造口是暂时性的还是永久性的,都会打击患者,并影响患者生活的方方面面:社交和职业生活、情感和家庭生活以及人格同一性和自尊。在暂时性造口的情况下,在患者有造口的时期,造口常常被视为患者生活的一大主要障碍。在肠实现重新连接后,一些患者还会担心自己会需要新的造口,不过这确实是有可能的。

抱着在患者护理需求管理方面实现患者独立性的目标,或在造口患者、护理者无法实现这一点的情况下,造口治疗护士要将TPE整合为理解患者生活经验的持续过程,并建立合作伙伴关系,在术前治疗、术后、康复、居家护理,以及短期或长期随访等所有阶段中教导患者和告知患者相关知识。

该患者的教育根据患者的需求侧重于不同的主题。例如,造口相关的、需要自我护理的组织方面(护理、更换器具、均衡消化、食品安全性等)。患者的一些自我调节困难,例如畸形的自我形象、低自尊等心理情感影响19-21,以及难以在自己的社交圈谈论自身疾病或造口,或难以恢复性生活,很可能需要培养社会心理应对技能和能力,来加快适应。因此,执业者可以运用自己的知识、临床技能和人际交往技能,找到适合患者或护理者学习方式的教学策略,同时始终尊重/考虑患者的极限、恐惧感以及任何抵触情绪,以引导他们完成TPE过程的每一步。最终,这些过程的成功整合将使患者能够对自己进行自我护理,并适应与造口(有时还存在慢性疾病)的共处。

造口患者会经历哪些阶段?我们如何帮助他们克服困难?

根据Selder22的理论,慢性疾病患者的生活经历类似于一个穿过充满不确定性的混乱现实的旅程,该旅程最终导致对该现实的重构。

为了动员患者的资源,执业者必须借助自己的适应力23,24、融会贯通(应对技能)25和赋权技能26,自己承担起与患者会面并理解他们的陈述、价值观和信念的工作27,28,以便将患者纳入自己的医疗保健。这些方面与个人适应的社会文化和宗教背景息息相关,也必须予以考虑,以便将其整合在为患者提供的护理中29,30。

根据Bandura的理论31,32,患者的自我效能感取决于四个方面:个人控制感、模仿、社会学习以及他们的生理和情绪状态。这会在具有良好自我效能水平的患者中产生三种类型的积极影响:第一种与所采取行为的选择有关,第二种与所采取行为的持久性有关,第三种与面对不可预见的事件和困难时的强大适应力有关。实施TPE的护士将能够通过其医疗保健干预,来动员TPE的这四个方面,以达到在患者身上引发这三类积极影响的目的。

根据Diclemente等人的观点33,行为生活的改变只能分阶段进行。在造口治疗中,这些以患者为中心的方法始于术前阶段,在该阶段,需要向患者(及可能的家属)提供有关可能需要造口、具体手术操作和术后护理的说明(WCET®建议3.1.2,SOE=B+29),即使尚未确认进行造口术。这些建议已被伤口造口失禁护士协会®(WOCN®)34采用。

根据Martin和Savary的研究35粗略翻译和改编而成的图式描述了学习过程中需要满足和培养的主要步骤(图2)。取决于患者的年龄,成人教育所采用的知识、工具和过程,为达到这些要求,TPE要求可能是动员患者的必要组成部分36,37。对于相对年轻的人群,特别是青少年,将需要采取其他策

略38,39。

图2. TPE的要求

造口患者治疗教育中的问题和目标示例

这些问题和教学目标可能适用于失禁造口患者,这反映了最常遇到的情形(表1)。

表1

对于其他不太常见类型的造口患者,例如可控性或营养支持造口患者40,41,其中一些问题和教学目标仍适用,和/或需要进行改编以适应其特殊情况;其他更具体的问题可能适用。肠外瘘患者也是如此42。

在某些情况下,出于厌恶、拒绝、否定和/或无能力(运动功能、大脑、心理情感或精神病),造口患者可能无法完成学习和赋权的某些或全部过程43。这可能是短期、中期问题,有时还会成为长期的问题。在这些情况下,应当想到并安排向护理者(执业者或近亲)求助。必须以相对类似的方式,进行赋权所需的教育过程,以期在最大程度上加快使造口患者返家的过程。对此必须增加支持性沟通,以及人际关系的管理和可能的改变,以及可能情况下,患者及其伴侣之间的亲密关系的管理和可能的改变。可通过应用TPE的原理来产生此类改变,并且将需要对这种类型的护理进行定期重新评估,并采用针对患者及其各自情况的整体方法加以考虑。

对于独自居住的患者而言,这些过程甚至更加复杂,对于年老的患者而言则还要更复杂,因为这可能导致对这些患者出院回家,以及独自生活的能力产生质疑。在这种情况下需要保证强大的通信中继和网络,使我们想起了2012年美国退休人员协会(AARP)报告中的所提建议45,46。

最后,偶尔情况下,造口患者会有多个造口,这些造口可能都是永久性的(图3和4)。根据我们的经验,这些复杂的情况比过去更加频繁,并且通常与恶性病变相关。

图3.永久性左侧结肠造口术和经回肠经皮输尿管造口术(Bricker术)患者示例,伴有紫色尿袋综合征47。

图4.暂时性结肠造口术和保护性回肠造口术数天后的术后患者示例。经过从下游造口开始,然后是上游造口的两次干预后,将在9个月内恢复消化系统的连续性。

有关慢性伤口患者的见解和额外信息

与某些先入之见相反,尽管使用原始术语造口治疗师(ET)48可能导致概念混淆,但造口治疗并不仅仅与造口患者的护理有关。实际上,完整的造口治疗师护理教育计划(ETNEP)49包含为存在伤口、排便功能障碍、肠外瘘的人提供医疗保健,在一些学院还包含为经过乳房切除术的人提供医疗保健。即便如此,伤口护理专业方向本身已成为专科服务,许多ET或造口治疗护士与伤口护理专科人员开展了密切合作。需要注意的重要一点是,在欧洲的课程中,这些方面的患者教育专门针对伤口护理专科护士(第3和4单元)50-52。

在文献中,关于为有伤口的患者提供的教育,所教导的知识被描述为自我管理的过程,特别是在患有下肢溃疡等慢性疾病的患者中53。为了使教育有效,患者必须从他们参与提议的预防性活动而可能产生的改变中得到可感知的受益。无论是身体还是情绪方面的受益,其均会增强所提建议的积极效果54。

使用多媒体教学方法的好处在于可结合多种传输信息的方法。这有助于解决患者遇到的问题,而且也可以增强向患者提供的信息55,56。

对于静脉性溃疡、糖尿病足溃疡和压力性损伤的患者,已进行了许多Cochrane系统评价。他们发现:

- 对于下肢溃疡患者,尽管事实是,对加压疗法的依从性是防止下肢溃疡复发的重要因素,但尚无足够的研究评估可以增加患者依从性的患者支持策略57。

- 对于糖尿病患者,没有足够的证据表明,在没有其他预防措施的情况下,教育足以降低足部病变和足截肢/下肢截肢的发生率58。

- 最后,对于压力性损伤,作者指出,患者参与的想法仍然含糊不清,且包括许多因素,这些因素各不相同,还包含范围较广的干预和可能的活动。同时他们澄清,这种对护理的参与(例如尊重患者权利)是重要的价值观,可以在他们的医疗保健中发挥作用。这种参与可能具有提升他们在个人健康方面的动力和知识的受益。此外,这种参与可能会涉及提高他们管理自身疾病和照顾自己的能力,从而提升他们的安全感,并使他们在改善健康方面取得更好的结果59。

对于有癌性伤口的患者,欧洲肿瘤护理学会的建议指出,有一些量表可用于评估这些伤口类型的症状,从而可及早检出相关并发症,以及减少与护理相关的费用和用于医疗保健的设备数量,同时提高患者的参与度。确实,可以向患者建议使用所述的一些工具,让他们使用工具来帮助控制病情60。为了促成这种情况发生,尽管这些患者可能已经对自己、自身的治疗和自己的医疗团队失去了信心,但仍有必要向其提供有关使用工具的教育。即使他们的病情可能已有所好转,但伤口仍然是其疾病不可磨灭的痕迹。

结论

治疗教育是对患有慢性疾病或有慢性病症的个人进行干预的基石,其目标是带来健康相关的改善、进行预防和提供教育。这是一项基本活动,横跨了造口治疗专业方向的所有领域。由于每种情况都是独特的,因此治疗教育使执业者可以发展该领域的技能,从而改善护理的提供水平。它也促使我们进行创新、发挥创造力、不断适应和打破常规进行思考,以找到其他干预策略;它也要求我们举止谦逊,因为我们可能需要通过国内和/或国际专业网络寻求帮助。

根据Adams61的研究,TPE在干预方面仍有诸多前景,其中教育干预在改善医疗保健影响方面的效用仍在讨论中。但研究结果仍太有限,无法支持他们的证据。对其他作者而言,到目前为止,其有效性已被研究证实。在许多医院中,据报告这是一种节省成本的措施,出于它可以缩短患者住院时间,并减少患者并发症的数量62-66。

最后,在医院开始教育过程的同时,门诊和家庭护理服务也在进行跟进。从这个意义上讲,通信中继的实施和维护将是确保护理连续性、开展的过程的连贯性和协调性,以及将协作决定的未来阶段的这些方面的基础。在患者及其亲属的同意下,居家护理者参与这些过程很重要。他们的参与尽管可能产生其他必须解决的问题,但仍是不可忽视的资源。

对专业医护人员(尤其是护士)进行有关应用TPE的培训,将增强他们在患者教育方面的专业知识和效率67,他们会了解到,每种情况都会促使他们寻找新的策略和技能来克服所面临的挑战。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

伤口小节的内容部分是基于有关该主题的University Conference Model(UCM)小组会议68期间所做的笔记。本次小组会议在荷兰阿姆斯特丹的2017年欧洲伤口管理协会(EWMA)大会上举行,演讲者为组织活性临床专科护士Julie Jordan O’Brien和高级临床专科护士Véronique Urbaniak69。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Laurence Lataillade

Clinical Specialist Nurse and Stomatherapist, Geneva University Hospitals

Laurent Chabal*

Stomal Therapy Nurse and Lecturer, Geneva School of Health Sciences, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland. Haute École de Santé Genève, HES-SO Haute École Spécialisée de Suisse Occidentale, Vice-President of WCET® 2018–2020

* Corresponding author

References

- Miller LV, Goldstein J. More efficient care of diabetic patients in a county-hospital setting. N Engl J Med 1972;286:1388–1391.

- Lacroix A, Assal JP. Therapeutic education of patients – new approaches to chronic illness, 2nd ed. Paris: Maloine; 2003.

- Rogers C. Client-centered therapy, its current practice, implications and theory. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1951.

- Kübler-Ross E. On death and dying. London: Routledge; 1969.

- World Health Organization. Therapeutic patient education, continuing education programmes for health care providers. Report of a World Health Organization Working Group; 1998. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/145294/E63674.pdf

- Stewart M, Belle Brown J, Wayne Weston W, MacWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient-centered medicine: transforming the clinical method. Oxon: Radcliffe; 2003.

- Kronenfeld JJ. Access to care and factors that impact access, patients as partners in care and changing roles of health providers. Research in the sociology of health care. Bingley: Emerald Book; 2011.

- Dumez V, Pomey MP, Flora L, De Grande C. The patient-as-partner approach in health care. Academic Med: J Assoc Am Med Coll 2015;90(4):437–1.

- Gottlieb LN, Gottlieb B, Shamian J. Principles of strengths-based nursing leadership for strengths-based nursing care: a new paradigm for nursing and healthcare for the 21st century. Nursing Leadership 2012;25(2):38–50.

- Gottlieb LN. Strengths-based nursing care: health and healing for persons and family. New York: Springer; 2013.

- Orem DE. Nursing: concepts of practice. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book Inc; 1991.

- The Official Website of the Disabled Persons Protection Commission; 2018. Available from: http://www.mass.gov/dppc/abuse-prevention/types-of-prevention.html

- Finset A, editor. Patient education and counselling journal. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2019. Available from: https://www.journals.elsevier.com/patient-education-and-counseling/

- Roy, C. The Roy adaptation model. New Jersey: Pearson; 2009.

- Price P. How we can improve adherence? Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2016;32(S1):201–5.

- Lasserre Moutet A, Chambouleyron M, Barthassat V, Lataillade L, Lagger G, Golay A. Éducation thérapeutique séquentielle en MG. La Revue du Praticien Médecine Générale 2011;25(869):2–4.

- Ercolano E, Grand M, McCorkle R, Tallman NJ, Cobb MD, Wendel C, Krouse R. Applying the chronic care model to support ostomy self-management: implications for nursing practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2016;20(3):269–74.

- World Health Organization. Non-communicable diseases; 2020. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/noncommunicable_diseases/en/

- Price B. Explorations in body image care: Peplau and practice knowledge. J Psychiatric Mental Health Nurs 1998;5(3):179–186.

- Segal N. Consensuality: Didier Anzieu, gender and the sense of touch. New York: Rodopi BV; 2009.

- Anzieu D. The skin-ego. A new translation by Naomi Segal (The history of psychoanalysis series). Oxford: Routledge; 2016.

- Selder F. Life transition theory: the resolution of uncertainty. Nurs Health Care 1989;10(8):437–40, 9–51.

- Cyrulnik B, Seron C. Resilience: how your inner strength can set you free from the past. New York: TarcherPerigee; 2011.

- Scardillo J, Dunn KS, Piscotty R Jr. Exploring the relationship between resilience and ostomy adjustment in adults with permanent ostomy. J WOCN 2016;43(3): 274–279.

- Wilson EO. Consilience: the unity of knowledge. New York: Knopf; 1998.

- Zimmerman MA. Empowerment theory, psychological, organizational and community levels of analysis. In Rappaport J, Seidman E, editors. Handbook of community psychology. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2000. p. 43–63.

- Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Behav 1988;15(2):175–183.

- Knowles SR, Tribbick D, Connel WR, Castle D, Salzberg M, Kamm MA. Exploration of health status, illness perceptions, coping strategies, psychological morbidity, and quality of life in individuals with fecal ostomies. J WOCN 2017;44(1):69–73.

- Zulkowski K, Ayello EA, Stelton S, editors. WCET international ostomy guideline. Perth: Cambridge Publishing, WCET; 2014.

- Purnell L. The Purnell Model applied to ostomy and wound care. JWCET 2014;34(3):11–18.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol Rev 1977;84(2):191–215.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Psychological review. San Francisco: Freeman WH; 1997.

- Diclemente CC, Prochaska JO. Toward a comprehensive, transtheoretical model of change: stages of change and addictive behaviours. In Miller WR, Heather N, editors. Treating addictive behaviours. processes of change. New York: Springer; 1998. p. 3–24.

- Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society – Guideline Development Task Force. WOCN® Society clinical guideline management of the adult patient with a fecal or urinary ostomy – an executive summary. J WOCN 2018;45(1):50–58.

- Martin JP, Savary E. Formateur d’adultes: se professionnaliser, exercer au quotidien. 6th ed. Lyon: Chronique Sociale; 2013.

- Lataillade L, Chabal L. Therapeutic patient education (TPE) in wound and stoma care: a rich challenge. ECET Bologna, Italy [Oral presentation]; 2011.

- Merriam SB, Bierema LL. Adult learning: linking theory and practice. Indianapolis: Jossey-Bass; 2013.

- Mohr LD, Hamilton RJ. Adolescent perspectives following ostomy surgery, J WOCN 2016;43(5): 494–498.

- Williams J. Coping: teenagers undergoing stoma formation. BJN 2017;26(17):S6–S11.

- Stroud M, Duncan H, Nightingale J. Guidelines for enteral feeding in adult hospital patients. Gut 2003;52(7):vii1–vii12.

- Roveron G, Antonini M, Barbierato M, Calandrino V, Canese G, Chiurazzi LF, Coniglio G, Gentini G, Marchetti M, Minucci A, Nembrini L, Nari V, Trovato P, Ferrara F. Clinical practice guidelines for the nursing management of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and jejunostomy (PEG/PEJ) in adult patients. An executive summary. JWCON 2018;45(4):32–334

- Brown J, Hoeflok J, Martins L, McNaughton V, Nielsen EM, Thompson G, Westendrop C. Best practice recommendations for management of enterocutaneous fistulae (ECF). The Canadian Association for Enterostomal Therapy; 2009. Available from: https://nswoc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/caet-ecf-best-practices.pdf

- Jukes M. Learning disabilities: there must be a change in attitude. BJN 2004;13(22):1322.

- Wendorf JH. The state of learning disabilities: 507 facts, trends and emerging issues. 3rd ed. New York: National Center for Learning Disabilities, Inc; 2014.

- Reinhard SC, Levine C, Samis S. Home alone: family caregivers providing complex chronic care. AARP Public Policy Institute; 2012.

- Reinhard SC, Ryan E. From home alone to the CARE act: collaboration for family caregivers. AARP Public Policy Institute, Spotlight 28; 2017.

- Peters P, Merlo J, Beech N, Giles C, Boon B, Parker B, Dancer C, Munckhof W, Teng H.S. The purple urine bag syndrome: a visually striking side effect of a highly alkaline urinary tract infection. Can Urol Assoc J 2011;5(4):233–234.

- Erwin-Toth P, Krasner DL. Enterostomal therapy nursing. Growth & evolution of a nursing specialty worldwide. A Festschrift for Norma N. Gill-Thompson, ET. 2nd ed. Perth: Cambridge Publishing; 2012.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®, Education Committee; 2020. Available from: http://www.wcetn.org/the-wcet-education

- Pokorná A, Holloway S, Strohal R, Verheyen-Cronau I. Wound curriculum for nurses: post-registration qualification wound management – European qualification framework level 5. J Wound Care 2017;26(2):S9–12, S22–23.

- Prosbt S, Holloway S, Rowan S, Pokorná A. Wound curriculum for nurses: post-registration qualification wound management – European qualification framework level 6. J Wound Care 2019;28(2):S10–13, S27.

- European Wound Management Association. EQF level 7 curriculum for nurses; 2020. Available from: https://ewma.org/it/what-we-do/education/ewma-wound-curricula/eqf-level-7-curriculum-for-nurses-11060/

- Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Peel J, Baker DW. Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Educ Couns 2003;51(3):267–275.

- Van Hecke A, Beeckman D, Grypdonck M, Meuleneire F, Hermie L, Verheaghe S. Knowledge deficits and information-seeking behaviour in leg ulcer patients, an exploratory qualitative study. J WOCN 2013;40(4):381–387.

- Ciciriello S. Johnston RV, Osborne RH, Wicks I, Dekroo T, Clerehan R, O’Neill C, Buchbinder R. Multimedia education interventions for customers about prescribed and over-the-counter medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2013. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008416/full

- Moore Z, Bell T, Carville K, Fife C, Kapp S, Kusterer K, Moffatt C, Santamaria N, Searle R. International best practice statement: optimising patient involvement in wound management. London: Wounds International; 2016.

- Weller CD, Buchbinder R, Johnston RV. Intervention for helping people adhere to compression treatments for venous leg ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2013. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008378.pub2/abstract

- Dorrestelijn JA, Kriegsman DMW, Assendelft WJJ, Valk GD. Patient education for preventing diabetic foot ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2014. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001488.pub5/abstract

- O’Connor T, Moore ZEH, Dumville JC, Patton D. Patient and lay carer education fort preventing pressure ulceration in at-risk populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2015. Available from: http://www.cochrane.org/CD012006/WOUNDS_patient-and-lay-carer-education-preventing-pressure-ulceration-risk-populations

- Probst S, Grocott P, Graham T, Gethin G. EONS recommendations for the care of patients with malignant fungating wounds. London: European Oncology Nursing Society; 2015.

- Adams R. Improving health outcomes with better patient understanding and education. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2010;3:61–72.

- Lagger G, Pataky Z, Golay A. Efficacy of therapeutic patient education in chronic diseases and obesity. Patient Educ Couns 2010;79(3):283–286.

- Kindig D, Mullaly J. Comparative effectiveness – of what? Evaluating strategies to improve population health. JAMA 2010;304(8):901–902.

- Friedman AJ, Cosby R, Boyko S, Hatt on-Bauer J, Turnbull G. Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: a systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. J Canc Educ 2011;26(1):12–21.

- Jensen BT, Kiesbye B, Soendergaard I, Jensen JB, Ammitzboell Kristensen S. Efficacy of preoperative uro-stoma education on self-efficacy after radical cystectomy; secondary outcome of a prospective randomised controlled trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2017;28:41–46.

- Rojanasarot S. The impact of early involvement in a post-discharge support program for ostomy surgery patients on preventable healthcare utilization. J WOCN 2018;45(1):43–49.

- Knebel E, editor. Health professions education: a bridge to quality (quality chasm). Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

- European Wound Management Association; 2020. Available from: http://ewma.org/what-we-do/education/ewma-ucm/

- European Wound Management Association Conference; 2017. Available from: http://ewma.org/ewma-conference/2017-519/