Volume 40 Number 3

Successful treatment of an ileal conduit fistula with negative pressure: report of a case

Mengxiao Jiang, Huiming Lu, Meichun Zheng, Baojia Luo and Huiying Qin

Keywords negative pressure, dual tube, fistula of ileal conduit, urostomy

For referencing Jiang M et al. Successful treatment of an ileal conduit fistula with negative pressure: report of a case. WCET® Journal 2020;40(3):19-23.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.3.19-23

Abstract

Aim To present the management of a patient who developed a fistula from a uretero-ileostomy anastomosis of the ileal conduit by applying intra-conduit negative pressure through a dual tube.

Case report The patient was a 73-year-old man diagnosed with bladder cancer who underwent a radical cystectomy and formation of an ileal conduit in our centre. A fistula occurred in the ileal conduit less than 1 week after the surgery. Urine leaked continuously into the pelvic cavity which put the patient at risk of fluid and electrolyte imbalances. A further operation to suture the fistula to contain the leakage was suggested. To save the patient from a further operation, intra-conduit negative pressure through a dual tube was attempted to assist with management of the fistula. This conservative treatment promoted successful closure of the fistula.

Method It is clinically challenging to manage a urinary fistula associated with an ileal conduit in a conservative way. This is because the fistula is deep within the body cavity and it is almost impossible for the fistula to heal spontaneously. The literature reveals previous conservative treatment has been mostly unsuccessful. Surgical suturing of the fistula is the most used method but is not always an ideal choice. By applying intra-conduit negative pressure through a dual tube system to the ileal conduit, the aim was to facilitate closure of the fistula.

Conclusion In this case report the application of intra-conduit negative pressure through a dual tube to contain a fistula from a uretero-ileostomy anastomosis of an ileal conduit was found to be safe and effective. This method of conservative treatment is worth promoting.

Introduction

Bladder cancer is a highly prevalent disease associated with high recurrence and mortality1. Radical cystectomy is the gold standard treatment for both muscle invasive bladder cancer and recurrent high grade non-muscle invasive bladder cancer2. After radical cystectomy, surgeons mostly choose the formation of an ileal conduit or urostomy for urinary diversion3. It is reported that 15–16% of patients will develop a fistula within the conduit after urinary diversion4,5. Urinary fistula of an ileal conduit is a complex and serious complication that often occurs in the early postoperative period2,5. The occurrence of this complication will not only prolong the hospital stay of patients, but also increases the mortality rate5.

Management of a urinary fistula within an ileal conduit is difficult6. One management option to deal with this complication is further surgery to suture the fistula; however, operating twice on the patient in a short time can cause too much trauma. Doctors and ET nurses often feel very conflicted as to whether to operate a second time, especially when a patient’s physical and psychological condition may not be robust enough to tolerate secondary surgery. Further, the patient may refuse a second operation. In addition to surgical treatment, the literature reveals that other conservative management strategies such as percutaneous nephrostomy or a fenestrated conduit catheter usually fail to close the fistula5.

Negative pressure therapy is widely used to treat fistulas as it facilitates and accelerates drainage of fluid which increases the likelihood of the fistula healing7–9. Through a literature review, the authors found positive results in several patients with a fistula of an ileal conduit following the application of negative pressure therapy10,11. While these previous studies revealed that negative pressure therapy maybe a good clinical choice for managing a urinary fistula within an ileal conduit, these relevant reports are too few and more studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of the treatment. Moreover, clinicians must be aware that ileal conduits are very vulnerable to secondary trauma during the negative therapy processes from the amount of negative pressure applied and catheter-related damage to the conduit5. In this case report, the authors present the outcome of the application of intra-conduit negative pressure in a patient with a fistula in a uretero-ileostomy anastomosis of an ileal conduit. The authors further demonstrate how to use a dual tube to decrease the treatment risk.

Case Presentation

A 73-year-old man in otherwise good health underwent a radical cystectomy and formation of an ileal conduit for muscle invasive bladder cancer. On the 5th postoperative day, the left pelvic drainage tube drained out 1350ml of faint yellow drainage, while the urinary stoma only drained out 700ml of urine. Urinary leakage of the intra-abdominal portion of the ileal conduit was suspected. Examination of fluid from the left pelvic drain confirmed the suspicion and presence of urine as creatinine was confirmed. The level of creatinine present in the drainage fluid was high at 4396.μmol/L – normal range of serum creatinine is 60–110μmol/L. A CT scan of the abdomen showed the fistula was located where the right transplanted ureter entered the ileal conduit.

Careful examination of the ileal conduit was also undertaken and a large amount of mucus was found to have accumulated in the ileal conduit. The doctor flushed the ileal conduit to clear the mucus away. However, although the ileal conduit was no longer obstructed from mucus, the urine still leaked into the pelvic cavity continuously. On the 6th postoperative day, the left pelvic drainage increased to 1890ml, while the urine draining out from the stoma decreased to 410ml. Urine leakage increased the risk of pelvic infection and water electrolyte imbalance; both clinical problems needed to be managed properly as soon as possible. A further operation to suture the fistula closed was suggested. However, taking the trauma of further surgery, the economic cost and the patient’s will into consideration, it was decided to attempt implementation of conservative treatment first.

Negative pressure therapy

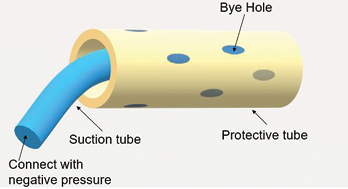

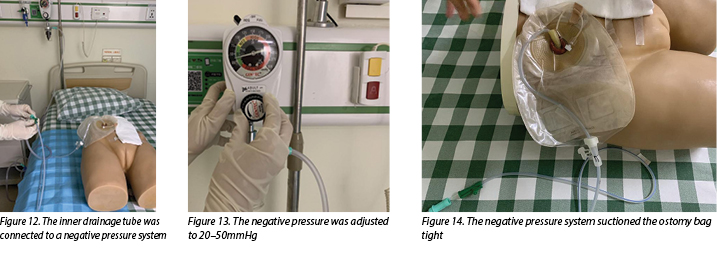

The negative pressure system used was constructed by a doctor and an ET nurse. The authors chose this therapy with the aim of achieving two goals. Firstly to stop urine draining continuously into the pelvic cavity and secondly to promote the closure of fistula. A well-known contraindication is to apply negative pressure therapy to organs because the risk of traumatising organs is high. To avoid adverse events such as bleeding, ischaemia and catheter-related ileal conduit perforation from happening, the authors applied negative pressure to the ileal conduit through a dual tube (Figure 1). The dual tube consisted of a rigid tube and a soft tube. The rigid tube could conduct negative pressure well; however, it may cause mechanical damage to the ileal conduit. The soft tube was unable to sustain negative pressure but could protect the ileal conduit from catheter-related injuries by isolating the rigid tube from coming into contact with the ileal conduit. The steps used to construct and apply the therapeutic negative pressure system are listed as follows.

Figure 1. An illustration of a dual tube

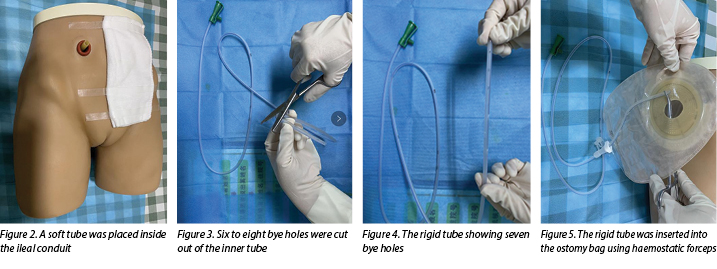

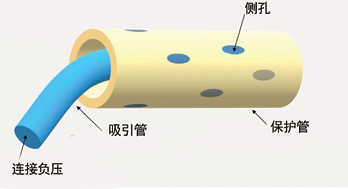

- Select a soft and protective medical latex tube as the outer tube. A soft tube is routinely placed inside the ileal conduit during operation and, as this tube had not been removed when the urinary fistula occurred in our case, it was used as the outer tube (Figure 2).

- Select a rigid tube such as a medical sputum aspiration tube as the inner tube.

- Cut six to eight bye holes out of the inner tube (Figures 3–4).

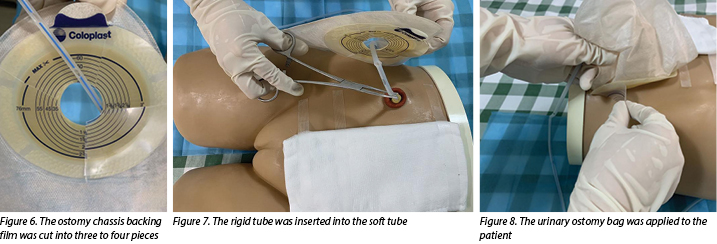

- Insert the rigid tube into the ostomy bag with haemostatic forceps (Figure 5), cut the ostomy chassis backing film into three to four pieces(Figure 6).

- The doctor then inserts a rigid tube into the soft tube (Figure 7). The insertion depth of the inner tube should be 1cm shorter than the outer tube.

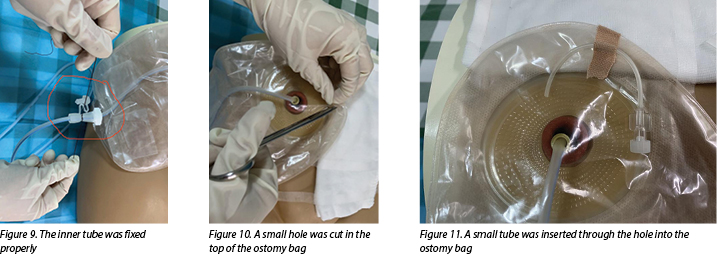

- Apply a urinary ostomy bag to the ostomy skin barrier or base plate (Figure 8) and fix the inner tube properly (Figure 9).

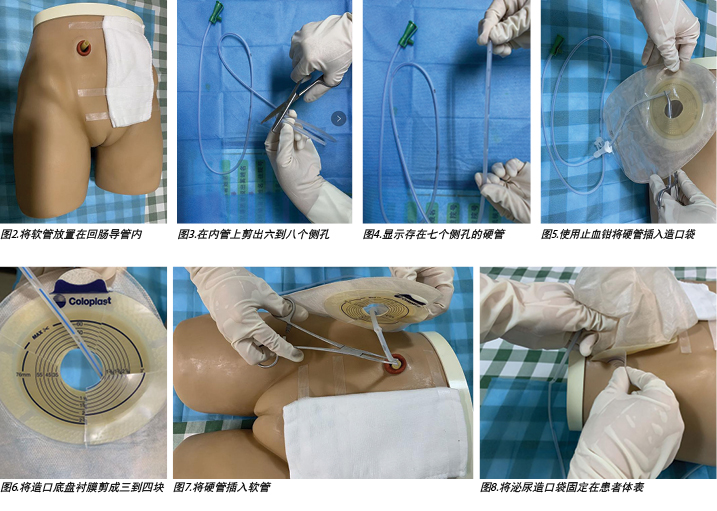

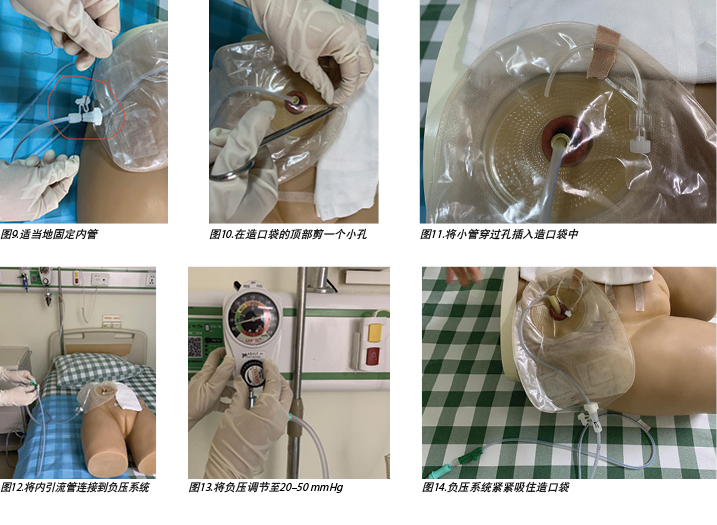

- Cut a small hole in the top of the ostomy bag (Figure 10), and insert a small tube through the hole into the ostomy bag to make the negative pressure semi-closed (Figure 11).

- Connect the inner drainage tube to a negative pressure system (Figure 12) and adjust the negative pressure to 20–50mmHg (Figure 13). In this case, wall suction was used, but a commercial negative pressure therapy machine is also suggested.

- After doing this, observe the negative pressure system suctioning the ostomy bag tight and, at the same time, urine should be immediately sucked out from the ileal conduit (Figure 14).

During the negative pressure therapy process, the patient’s fluid and electrolyte balance was closely monitored, the ileal conduit was cleared of mucus twice a day, and the patient was instructed to do passive activities while in bed. A nutritionist and psychotherapist were invited to join the medical, ET and nursing team to help improve the nutritional and psychological status of the patient.

After 12 days of negative pressure therapy treatment, the left pelvic drainage decreased to 210ml and the creatinine level of the drainage output was 73.7μmol/L, which indicated that urine was no longer leaking into the pelvic cavity. The negative pressure therapy was stopped 2 days later. It was pleasing to note that, following cessation of suction of the urine, there was no increase in pelvic drainage. The patient recovered well and was discharged from the hospital soon after. After a follow-up period of 3 months, no further anastomotic insufficiency was noted.

Discussion

While not a medical emergency, a fistula within an ileal conduit is a complication that is very difficult to manage conservatively. Up till now, the treatment of this type of fistula occurrence has still been in exploratory stages. Conservative management strategies such as percutaneous nephrostomy and fenestrated conduit catheters have been tried to manage these situations, but are reported to have a high failure rate5. Percutaneous nephrostomies are commonly used for urinary diversion, resulting in successful drainage of urine12; however, this method of urinary diversion does not aid fistula healing. Similarly, placing a fenestrated drainage tube or fenestrated catheter into an ileal conduit is also ineffective. While this method may increase the patency of urine drainage it does not prevent urine from leaking into the pelvic cavity, nor does it promote development of granulation tissue around the fistula to assist with fistula closure.

Proper drainage of urine and promotion of the growth of granulation tissue are keys factors for healing fistulas of this nature. Negative pressure systems can help stimulate the formation of granulation tissue and remove excess exudate away from the wound site13. Thus, negative pressure therapy may be a useful alternative for the treatment of urinary fistula. Continuous suction leads to the absorption of leaking urine and intestinal mucus that can cause infection and disturb fluid and electrolyte balance of the patient. In addition, stimulation of angiogenesis and granulation tissue formation increases the chance of fistula healing.

Although negative pressure appears to work well in promoting the closure of fistulas, it should be used and applied with caution to fistulas within an ileal conduit. Adverse events such as bleeding, ischaemia and intestinal perforation may occur due to using negative pressure therapy to exposed organs14. Safety is more important than a curative effect. Although no adverse events have been reported in previous studies10,11,15, this does not mean the therapy is safe and without risk. Some measures must be taken to decrease the treatment risk for the patient. Inserting a protective disc over the exposed organs could offer protection from local ischaemia, while still providing effective drainage16.

In the dual tube model discussed here, the outer tube acted as a protective disc, thereby protecting the ileal conduit from mechanical injury and decreasing the risk of ischaemia and haemorrhage that may be caused by negative pressure. An animal experiment showed negative pressure between 50–170mmHg caused a significant decrease in the microvascular blood flow in the intestinal loops16. The authors, therefore, adjusted the negative pressure to 20–50mmHg in this case to avoid ischaemia occurring. Compared with intestinal fistula, it was less likely that the suction tube would be obstructed when in a urinary fistula, so there was less need to adjust the negative pressure to more than 50mmHg. Moreover, keeping the negative pressure semi-closed was also a protective method to avoid ischaemia by stopping the tube from being tightly suctioned to intestinal tissue for long periods.

There are currently very few recommendations on the use of negative pressure therapy for the management of urinary fistula. As the patient did not have coagulation defects, the authors felt that, under close clinical observation, it would be worth trying very gentle negative pressure through a dual tube approach to aid urinary fistula healing. During the therapy process, it is necessary to regularly check whether the suction tube is displaced or obstructed, monitor the amount of the pelvic drainage and urine discharged in the collecting system of the device daily, and be alert for complications such as bleeding, ischaemia, infection and fluid and electrolyte imbalances. Urinary leakage at the anastomotic site of an ileal conduit can lead to periureteral fibrosis and scarring, thus predisposing to stricture formation6. Surgical follow-up to evaluate anastomotic status is also needed.

Summary

Fistula occurrence at the site of an ileal conduit is a serious complication after urostomy formation. How to promote the closure of urinary fistula quickly and effectively in a conservative way has been problematic and concerning for urologists and ET nurses for a long time. In this case report the authors have shared their successful experience with the application of negative pressure through a dual tube system to manage this complication. The treatment in this instance was found to be safe and effective. It is worth further exploration as the authors believe more patients could benefit from it.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

使用负压成功治疗回肠导管瘘:病例报告

Mengxiao Jiang, Huiming Lu, Meichun Zheng, Baojia Luo and Huiying Qin

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.3.19-23

摘要

目的 介绍对一例因回肠导管的输尿管-回肠吻合口出现瘘管的患者,通过双管法施加导管内负压进行的治疗。

病例报告 患者是一例确诊为膀胱癌的73岁男性,在本中心行根治性膀胱切除术和回肠导管形成术。术后不到1周回肠导管中出现瘘管。尿液不断漏入盆腔,使患者处于水电解质紊乱的危险中。建议行进一步手术,缝合瘘管以控制渗漏。为了使患者免于行进一步手术,尝试通过双管施加导管内负压来进行瘘管的辅助治疗。这种保守治疗促成了瘘管的成功闭合。

方法 以保守方式治疗与回肠导管相关的尿瘘在临床上具有挑战性。这是因为瘘管位于体腔深处,几乎不可能自发愈合。文献显示先前的保守治疗大多不成功。外科手术缝合瘘管是最常用的方法,但不一定始终是理想的选择。通过双管系统向回肠导管施加导管内负压,目的是促进瘘管的闭合。

结论 本病例报告发现,通过双管施加导管内负压来控制回肠导管的输尿管-回肠吻合口引起的瘘管是安全有效的。这种保守治疗方法值得推广。

引言

膀胱癌是一种患病率极高的疾病,具有高复发率和高死亡 率1。根治性膀胱切除术是治疗肌层浸润性膀胱癌和复发性高级别非肌层浸润性膀胱癌的金标准2。根治性膀胱切除术后,外科医生大多选择行回肠导管形成术或尿道造口术进行尿流改道3。据报告,15-16%的患者在尿流改道后,导管内会出现瘘管4,5。回肠导管的尿瘘是一种复杂且严重的并发症,常发生在术后早期2,5。这种并发症的发生不仅会延长患者的住院时间,而且会增加死亡率5。

回肠导管内的尿瘘治疗困难6。解决这种并发症的一种治疗方法是进一步手术缝合瘘管;但是,在短时间内对患者进行两次手术会导致过多的创伤。医生和ET护士经常对是否要进行二次手术感到非常矛盾,特别是当患者的身体和心理状况可能不够强健,无法承受二次手术时。此外,患者可能会拒绝二次手术。除外科手术治疗外,文献还显示其他保守治疗策略(例如经皮肾造口术或有孔导管)通常无法闭合瘘管5。

负压疗法被广泛用于治疗瘘管,因为它可以促进和加速液体引流,从而增加瘘管愈合的可能性7–9。通过文献综述,作者发现,在施用负压疗法后,几例回肠导管瘘患者均获得了积极的结果10,11。虽然这些先前的研究表明负压疗法可能是治疗回肠导管内尿瘘的良好临床选择,但相关报告太少,需要更多的研究来证实该治疗的安全性和有效性。此外,临床医生必须意识到,回肠导管在负压疗法过程中极易受到施加的负压量造成的继发性创伤和对回肠导管造成的治疗导管相关损伤5。在本病例报告中,作者介绍了对回肠导管的输尿管-回肠吻合口内存在瘘管的患者施加导管内负压的结局。作者进一步论证了如何使用双管来降低治疗风险。

病例介绍

一位在其他方面健康状况良好的73岁男性,因肌层浸润性膀胱癌行根治性膀胱切除术和回肠导管形成术。术后第5天,左侧盆腔引流管排出1350 ml淡黄色的引流液,而泌尿造口仅排出700 ml尿液。怀疑回肠导管的腹内段漏尿。检查左侧盆腔引流的液体证实了这一怀疑,并确认了尿肌酐的存在。引流液中存在的肌酐水平高达4396.μmol/L,而血清肌酐的正常范围为60–110 μmol/L。腹部CT扫描显示瘘管位于右侧移植输尿管进入回肠导管的位置。

还仔细检查了回肠导管,发现大量粘液蓄积在回肠导管内。医生冲洗回肠导管,清除粘液。然而,尽管回肠导管不再因粘液堵塞,尿液仍持续地漏入盆腔。术后第6天,左侧盆腔引流量增加至1890 ml,而造口排尿量减少至410 ml。漏尿增加了盆腔感染和水电解质紊乱的风险;这两个临床问题均需要尽快得到妥善治疗。建议行进一步手术,通过缝合闭合瘘管。然而,考虑到行进一步手术的创伤、经济成本和患者意愿,决定先尝试实施保守治疗。

负压疗法

所用负压系统由一名医生和一名ET护士构建。作者选择这种疗法是为了实现两个目标。一是阻止尿液持续流入盆腔,二是促进瘘管闭合。对器官施用负压疗法是众所周知的禁忌症,因为器官受到创伤的风险很高。为了避免出血、局部缺血和治疗导管相关性回肠导管穿孔等不良事件的发生,作者通过双管对回肠导管施加负压(图1)。双管由硬管和软管组成。硬管可以很好地传导负压;然而,它可能对回肠导管造成机械损伤。软管不能承受负压,但可以通过隔离硬管与回肠导管接触来保护回肠导管免受治疗导管相关性损伤。用于构建和应用治疗性负压系统的步骤如下。

图1.双管示意图

• 选择柔软、具有保护作用的医用乳胶管作为外管。手术过程中,软管常规放置在回肠导管内,由于我们的病例出现尿瘘时,该软管尚未被取出,所以被用作外管(图2)。

• 选择医用吸痰管等硬管作为内管。

• 在内管上剪出六到八个侧孔(图3-4)。

• 使用止血钳将硬管插入造口袋(图5),将造口底盘衬膜剪成三到四块(图6)。

• 然后医生将硬管插入软管(图7)。内管的插入深度应比外管短1 cm。

• 将泌尿造口袋贴在造口底盘上(图8),适当地固定内管(图9)。

• 在造口袋的顶部剪一个小孔(图10),将小管穿过孔插入造口袋中,形成半封闭的负压(图11)。

• 将内引流管连接到负压系统(图12),并将负压调节至20–50 mmHg(图13)。在本病例中,使用了壁式引流器,但也建议使用商用负压治疗机。

• 这一步完成后,观察负压系统是否紧紧吸住造口袋,同时尿液应立即从回肠导管中吸出(图14)。

在负压疗法过程中,密切监测患者的水电解质平衡状况,每天两次清除回肠导管中的粘液,并指导患者在卧床时进行被动活动。邀请一名营养师和心理治疗师加入医疗、ET和护理团队,帮助改善患者的营养和心理状态。

负压疗法治疗12天后,左侧盆腔引流量减少至210 ml,引流输出的肌酐水平为73.7 μmol/L,这表明尿液不再漏入盆腔。2天后负压疗法停止。令人高兴的是,注意到在停止吸尿后,盆腔引流量没有增加。患者恢复良好并在不久后出院。经过3个月的随访,没有发现进一步的吻合口功能不全。

讨论

虽然不是医疗紧急事故,但是回肠导管内瘘是一种通过保守方式非常难以进行治疗的并发症。到目前为止,这类瘘管事件的治疗仍处于探索阶段。已尝试使用保守的治疗策略(例如经皮肾造口术和有孔导管)来管理这些情况,但报告称失败率较高5。经皮肾造口术常用于尿流改道,带来尿液的成功引流12;但是,这种尿流改道方法不能帮助瘘管愈合。类似地,将有孔引流管或有孔治疗导管放入回肠导管内也无效。虽然这种方法可以增加尿液引流的通畅性,但不能防止尿液漏入盆腔,也不能促进瘘管周围肉芽组织的生长,进而辅助瘘管闭合。

适当的尿液引流和促进肉芽组织的生长是这种性质的瘘管愈合的关键因素。负压系统可以帮助刺激肉芽组织的形成,并清除伤口部位多余的渗出液13。因此,负压疗法可能是治疗尿瘘的一种有效替代方法。持续吸引会将可能导致感染并扰乱患者的水电解质平衡的漏尿和肠粘液吸收。此外,对血管新生和肉芽组织形成的刺激会增加瘘管愈合的机率。

虽然负压在促进瘘管闭合方面效果良好,但对于回肠导管内瘘应谨慎应用。因为对暴露的器官使用负压疗法,可能发生诸如出血、局部缺血和肠穿孔等不良事件14。安全比疗效更重要。尽管以前的研究中未报告任何不良事件10,11,15,但这并不意味着该疗法安全且没有风险。必须采取一些措施来降低患者的治疗风险。在暴露的器官上插入一个保护盘可以防止局部缺血,同时仍能提供有效的引流16。

在本文讨论的双管模型中,外管充当一个保护盘,从而保护回肠导管不受机械损伤,并降低因负压而可能引起的局部缺血和出血的风险。一项动物实验显示,50-170 mmHg之间的负压导致肠袢中微血管血流量明显减少16。因此,作者在本病例中将负压调节至20–50 mmHg,以避免发生局部缺血。与肠瘘相比,在尿瘘的情况下,吸引管堵塞的可能性较小,因此不太需要将负压调节到50 mmHg以上。此外,保持负压半封闭也是一种保护方法,可通过阻止管长时间紧吸至肠组织来避免局部缺血。

目前关于使用负压疗法治疗尿瘘的建议很少。作者认为,既然患者没有凝血不良,在密切的临床观察下,值得尝试通过双管法施加非常温和的负压来帮助尿瘘愈合。在治疗过程中,需要定期检查吸引管是否移位或堵塞,每天监测盆腔引流量和器械的收集系统中排出的尿量,警惕出血、局部缺血、感染、水电解质紊乱等并发症。回肠导管的吻合口处漏尿可导致输尿管周围纤维化和瘢痕形成,从而容易形成狭窄6。还需要手术随访以评价吻合状态。

总结

回肠导管部位出现瘘管是尿道造口形成后的一种严重并发症。如何以保守的方式快速有效地促进尿瘘的闭合一直是一个难题,也是泌尿科医师和ET护士长期以来关注的问题。在本病例报告中,作者分享了他们通过双管系统施加负压治疗这种并发症的成功经验。研究结果表明在此情况下的治疗是安全有效的。它值得进一步研究,因为作者相信更多的患者可以从中受益。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者在本研究中未收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Mengxiao Jiang

MD

Department of Urology Surgery; Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China; Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Medicine

Huiming Lu

BD

Department of Urology Surgery; Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China; Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Medicine

Meichun Zheng

BD

Department of Colorectal Surgery; Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China; Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Medicine

Baojia Luo

MD

Department of Colorectal Surgery; Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China; Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Medicine

Huiying Qin*

MD

Department of Nursing Division, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China; Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Medicine

Email qinhy@sysucc.org.cn

* Corresponding author

References

- Sanli O, Dobruch J ,Knowles MA, et al. Bladder cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2017;3:17022. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.22

- Wei ST, Lamb BW, Kelly JD. Complications of radical cystectomy and orthotopic reconstruction. Adv Urol 2015;2015(3):1-7. doi:10.1155/2015/323157.

- Kotb A F. Ileal conduit post radical cystectomy: modifications of the technique. J Ecancermedicalscience 2013;7:301.

- Teixeira SC, Ferenschild FT, Solomon MJ, et al. Urological leaks after pelvic exenterations comparing formation of colonic and ileal conduits. Eur J Surg Oncol 2012;38(4):361–366.

- Brown KG, Koh CE, Vasilaras A, et al. Clinical algorithms for the diagnosis and management of urological leaks following pelvic exenteration. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014;40(6):775–781.

- Farnham SB, Cookson MS. Surgical complications of urinary diversion. World J Urol 2004;22(3):157–167.

- Bobkiewicz A, Walczak D, Smolinski S, et al. Management of enteroatmospheric fistula with negative pressure wound therapy in open abdomen treatment: a multicentre observational study. Int Wound J 2017;14(1):255–264.

- Ruiz-Lopez M, Titos A, Gonzalez-Poveda I, et al. Negative pressure therapy as palliative treatment for a colonic fistula. Int Wound J 2014;11(2):228–229.

- Loaec E, Vaillant PY, Bonne L, et al. Negative-pressure wound therapy for the treatment of pharyngocutaneous fistula. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2014;131(6):351–355.

- Yetişir F, Salman AE, Aygar M, et al. Management of fistula of ileal conduit in open abdomen by intra-condoit negative pressure system. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014;5(7):385–388.

- Denzinger S, Luebke L, Burger M, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy in ureteroileal anastomotic leakage after surgical therapy of bladder cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2007;5(1):41.

- Ahmad I, Pansota MS. Comparison between double J (DJ) ureteral stenting and percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN) in obstructive uropathy. Pakistan J Med Sci 2013;29(3):725–729.

- Wolvos T. The evolution of negative pressure wound therapy: negative pressure wound therapy with instillation. J Wound Care 2015;24(4 Suppl):15–20.

- Ontario HQ. Negative pressure wound therapy: an evidence update. Ontario Health Technology Assessment 2010;10(22):1.

- Heap S, Mehra S, Tavakoli A, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy used to heal complex urinary fistula wounds following renal transplantation into an ileal conduit. Am J Transplant 2010;10(10):2370–2373.

- Lindstedt S, Hlebowicz J. Blood flow response in small intestinal loops at different depths during negative pressure wound therapy of the open abdomen. Int Wound J 2013;10(4):411–417.