Volume 40 Number 3

Introduction of pressure injury preventive measures and improvement initiatives for patients undergoing prolonged surgery at a government hospital in the United Arab Emirates

Asha Ali Abdi, Ashwaq Ali, Fatima El-Ahmed

Keywords pressure injury, risk assessment, hospital-acquired pressure injury, prolonged surgery, preventive measures

For referencing Abdi A et al. Introduction of pressure injury preventive measures and improvement initiatives for patients undergoing prolonged surgery at a government hospital in the United Arab Emirates. WCET® Journal 2020;40(3):24-36.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.3.24-36

Abstract

Objectives

- Initiate and implement an appropriate risk assessment tool to identify high-risk prolonged surgery patients at risk of developing pressure injuries (PIs).

- Initiate education and training regarding PI prevention and management in the operating theatre (OT).

- Establish resource individuals in the OT.

- Enable early identification of high-risk patients and implementation of preventative measures.

Methods A retrospective data analysis was conducted from Safety Intelligence (SI) 2016–2017 gathering baseline information of all skin injuries, particularly PIs reported in the OT. Upon completion of a needs analysis, a continuous quality improvement and learning model, Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA), was initiated. Comparative data from Quarter 1 (Q1) 2016 to Quarter 4 (Q4) 2018 pre- and post-implementation were analysed.

Results Within a period of 9 months from April to December 2018, 99 patients were referred to the wound care team, with an average operation time of 7 hours. Two cases of PI were reported in Q2 and Q4 2018. The contributing factors discovered upon review of the root cause analysis were related to poor nutrition, extended immobilisation, prolonged surgery time (more than 17 hours), presence of multiple comorbidities e.g. chronic renal failure, diabetes, hypoalbuminaemia and haemodynamic instability. Improvement outcomes were achieved by adhering to the new system and practices.

Conclusion Preventing PIs are part of patient safety and quality of care which needs collaborative and proactive teams with a sense of responsibility and accountability.

Introduction

Hospital-acquired pressure injuries (HAPIs) are one of the major challenges encountered by any healthcare facility, particularly in the critical care setting1. This significant problem highlights the increasing incidence of morbidity and mortality, including lengthening of hospital stays, and contributes a substantial financial burden to any healthcare system1. As defined by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP)2, a PI is “a localized damage to the skin and underlying soft tissue usually over a bony prominence or related to a medical or other device due to intense and/or prolonged pressure or pressure in combination with shear”. Evidence shows that 95% of these PIs are preventable, and reduction of these is considered an eminent priority for any healthcare organisation1.

One of the high-risk clinical areas of PI development for an ambulatory patient is in the operating theatre (OT). It was emphasised that patients undergoing an operation which lasts for more than 3 hours are at high risk of PI occurence3. In addition, any injuries over a bony prominence in the body that developed within 72 hours after prolonged and direct pressure during and/or after any surgical procedure are considered a PI incident. Furthermore, a medical device-related PI is a “Pressure injury that results from the use of devices designed and applied for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. The resultant pressure injury generally closely conforms to the pattern or shape of the device”3. If this pattern of injury occurs during the surgical procedure, it is considered a PI as well4. Studies reveal that the incidence and prevalence rates of HAPIs secondary to prolonged surgical procedures range from 5–53.4% and 9–21% respectively4.

This incidence rate is likely related to the intraoperative fixed position, type of anaesthesia, length of surgery, and patient factors such as age, gender, and history of diseases such as diabetes and heart failure5. The risk of skin damage is much higher in surgical patients than in non-surgical patients due to being immobile during the procedures and lacking awareness of pressure sensation during anaesthesia6. Also, anaesthesia decreases autonomic nervous system function which, in turn, enlarges vessels and decreases tissue perfusion, especially over bony prominences; this increases with longer surgery time and the use of general anaesthesia7.

At the same time, there is no validated risk assessment measures for surgical patients which has been formally established8. Several instruments are available to screen patients at high risk. However, according to an analysis of the predictive validity of the Braden Scale applied to surgical patients, the absence of risk factors related to surgery in this scale – i.e. surgery time or the position of the patient – makes its predictive validity to be low6–8. Other instruments include the Munro Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Scale for Perioperative Patients – Adults (the Munro Scale) and the Scott Triggers tool. The Munro Scale includes 15 items to comprehensively assess the risk factors for PIs during the pre-, intra- and postoperative phases9–10. The Scott Triggers tool includes four items of age, serum albumin level, estimated surgery time, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score11.

One component of electronic health records (EHRs) is the pre-anaesthesia evaluation of the condition of a surgical patient written by the anaesthesiologist which is used to formulate an effective anaesthetic plan. This evaluation typically includes the type of surgery, serum albumin level and ASA score, which are also items on the Scott Triggers tool. Other data in the pre-anaesthesia evaluation are type of anaesthesia, laboratory test results such as haemoglobin and creatinine levels, and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes which are important to establish the profile, or model of risk factors, for predicting the development of PIs in surgical patients.

Although researchers have scrutinised individual prevention methods – e.g. repositioning, type of OT mattress used – the effectiveness of implementing a multidimensional approach has not been extensively evaluated8. Hence, it is essential for an institution to prevent and reduce the incidence of HAPIs, especially in the OT, and be able to provide safe and effective quality of care that is comparable to local and international benchmarks. Proper padding and pressure-relieving devices should be utilised. A support surface is required to redistribute pressure. The use of foam pads has not been as effective as protective devices, as they easily compress under heavy body areas and result in ‘bottoming out’.

Wound Care Service: an identified need

The Wound Care Service (WCS) at our medical city was initiated in early 2017 by two nurses. In 2018, three additional nurses joined the team to address and further enhance wound management delivered in the inpatient clinical areas. As mandated by SEHA – the Abu Dhabi Health Services Company, the owner/operator of all public hospitals and clinics across the United Arab Emirates, UAE – and the Department of Health (DOH), PI prevention and management are the primary goal of our team. Specific guidelines and key performance indicators (KPIs) known as Jawda (the Arabic word for quality) were published to serve as a guide in data collection and monitoring processes12.

In the first quarter (Q1) of 2018, three HAPI cases were reported after undergoing oral and maxillofacial (OMF) surgeries which lasted from 8–14 hours. This led to an in-depth inter-professional team investigation and initiation of root cause analysis (RCA) to determine contributing factors of these incidences. A retrospective data analysis was conducted from our institutional incident reporting system, Safety Intelligence (SI), between 2016 and 2017 to gather baseline information of all skin injuries – including rashes, irritation, ecchymosis, lacerations, burns, abrasions, skin tears – and PIs reported in the OT.

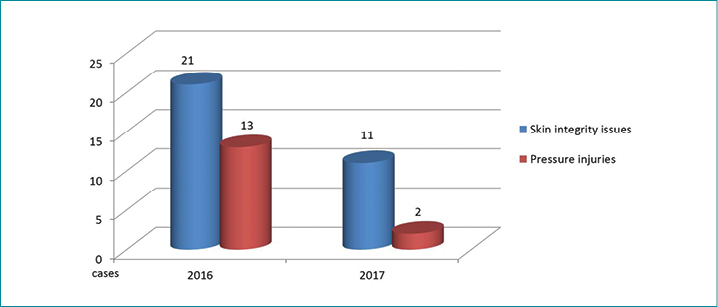

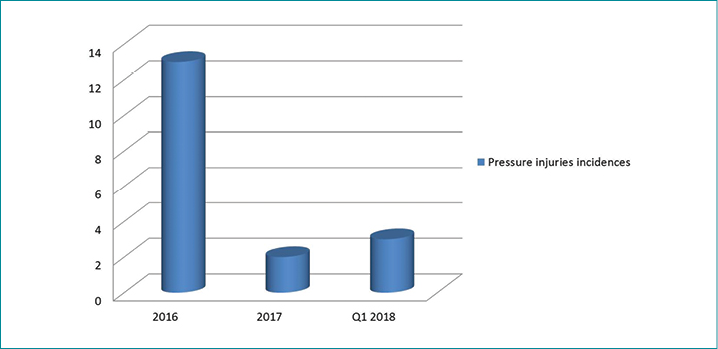

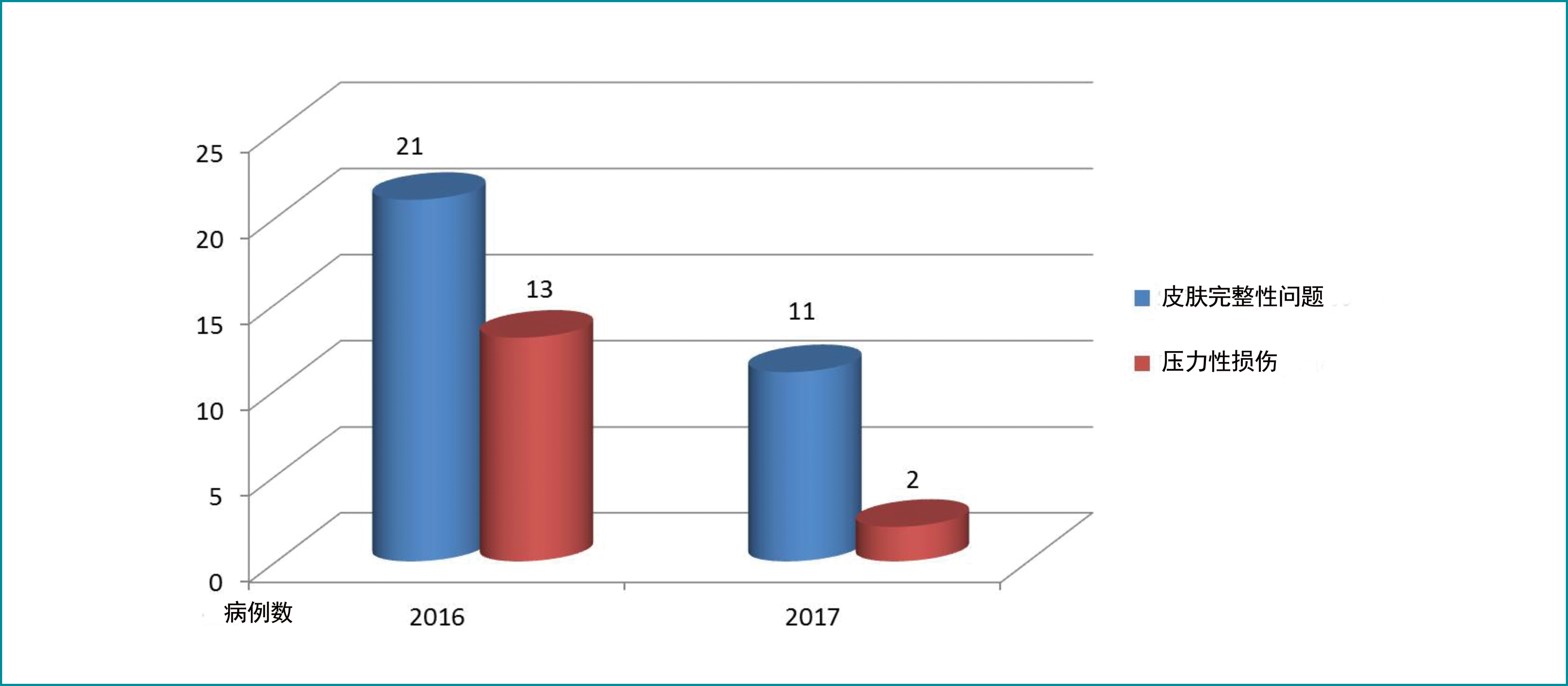

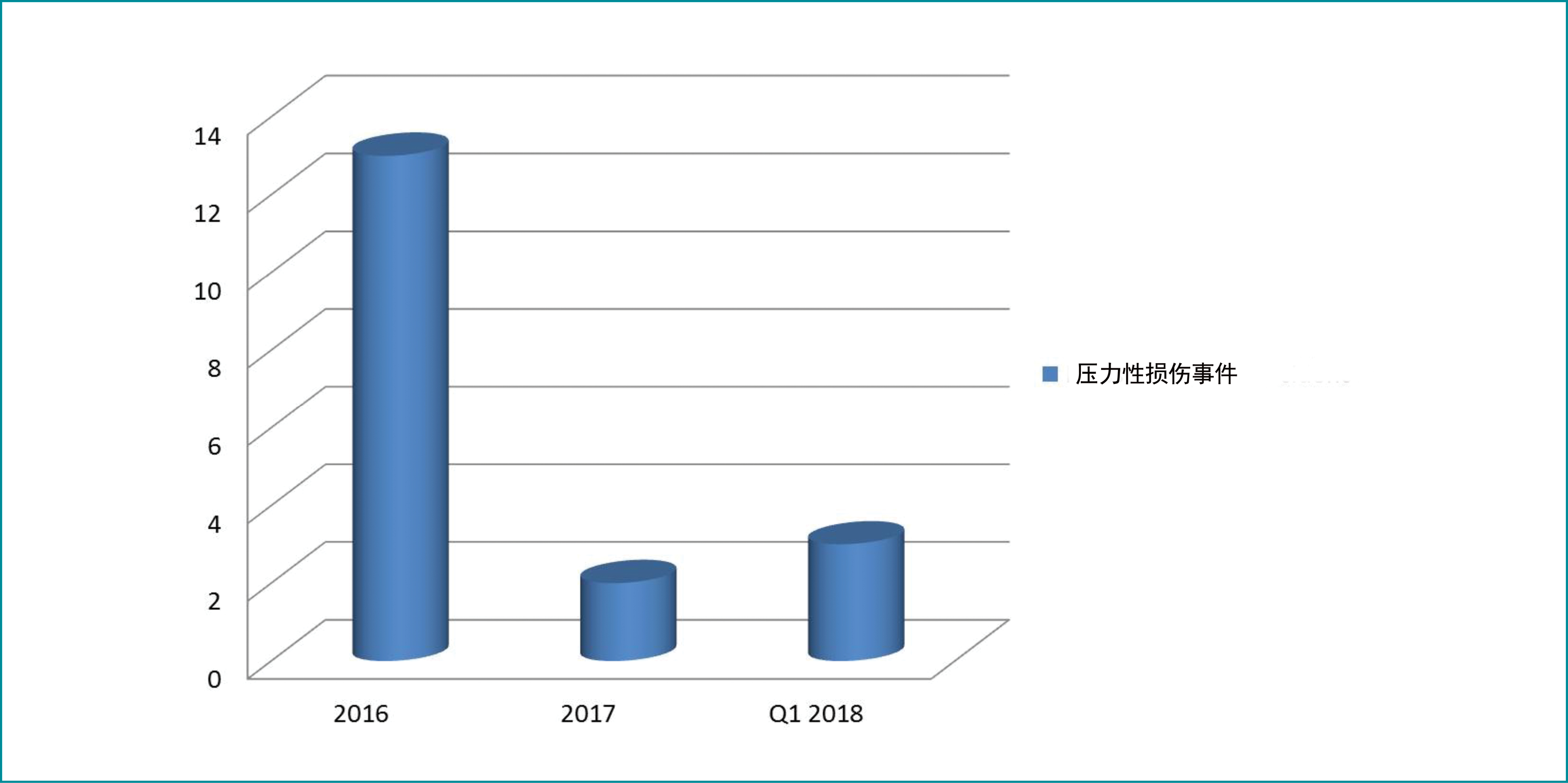

In 2016, there were 21 reported cases of impaired skin integrity, of which 13 were reported PI cases, while 11 incidents of skin injury, two of which were PIs, were logged in the SI reporting system in 2017 (Figure 1). Furthermore, from 2016 to Q1 of 2018, a total of 18 PI incidents were reported in the OT (Figure 2).

Figure 1. OT SI report 2016 versus 2017

Figure 2. PI incident as raw data reported in SI – Q1 2016 to Q1 2018 in the OT

In conjunction with the extensive effort towards patient safety and quality of care at our institution, this quality improvement initiative was chosen to increase PI risk awareness, particularly in the OT. We aimed to identify common contributing factors and evaluate current practice and procedures in coordination with members of the inter-professional OT team – OT nurse leaders/staff/ surgeons – and higher hospital management with representation from nursing, quality and education departments.

Quality improvement goals and objectives

The goal was to reduce the incidence of PIs secondary to prolonged surgery. The following objectives were formulated in order to address the rising HAPI incidence secondary to prolonged surgeries in the OT. Specifically, this study aimed to:

- Identify factors contributing to the development of PIs in the perioperative phase of the surgical population.

- Implement PI preventive measures through:

- Early identification of high-risk patients and adoption of specific and appropriate risk assessment tools.

- Initiation of in-service education and training to all OT staff regarding PI prevention and management.

- Formulation of guidelines and policies related to PI prevention and management specific to perioperative patients.

- Empowerment of OT staff who will serve as resource individuals, and monitoring improvements/progress related to PI incidences.

Project methods

Planning and implementation

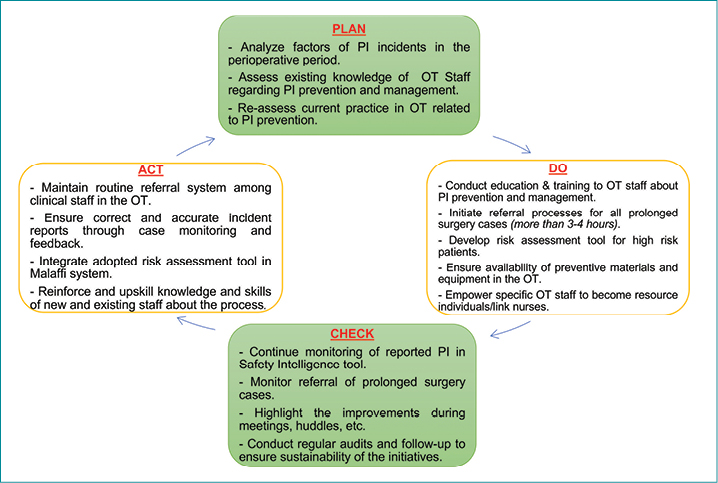

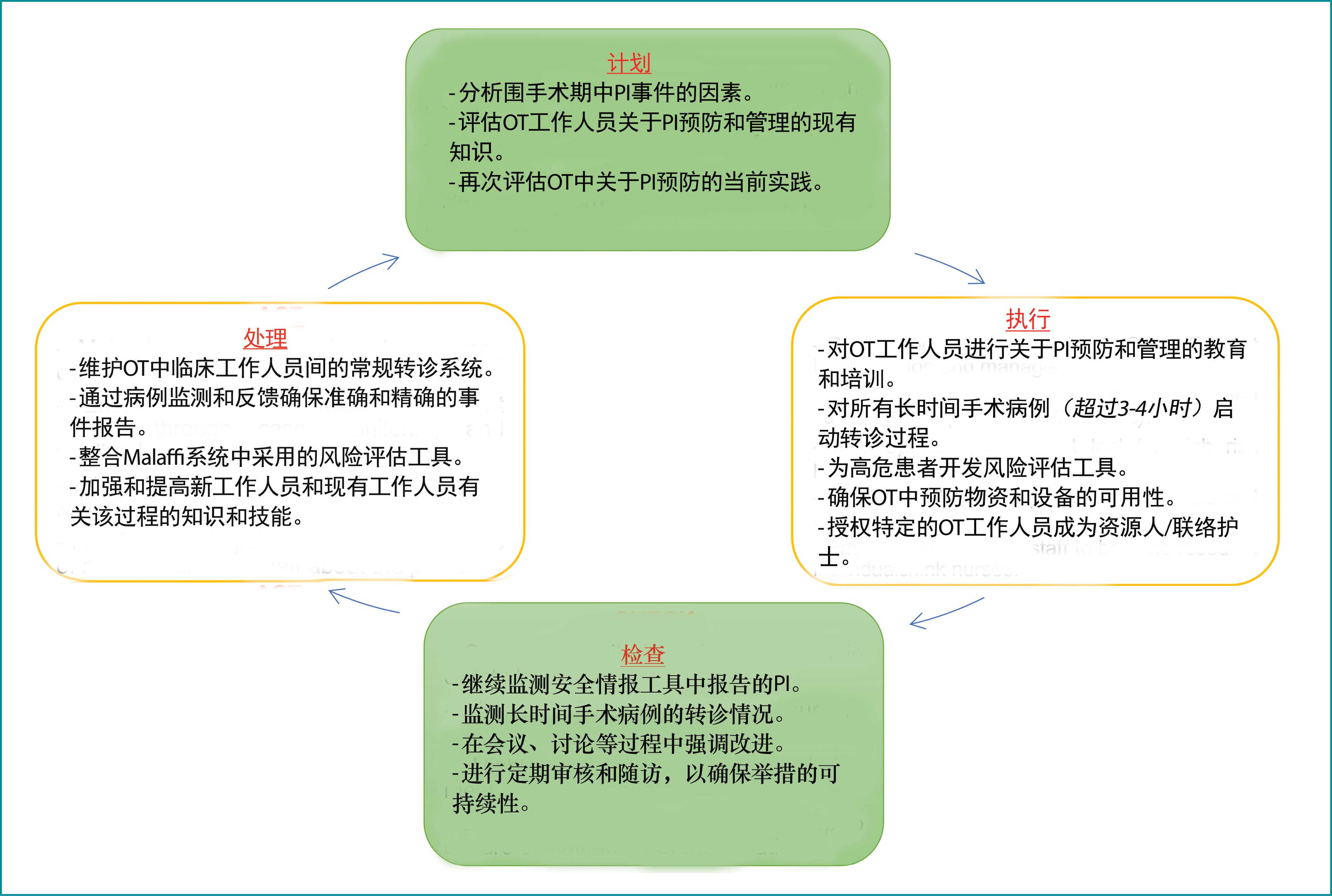

After completion of a needs analysis, the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) methodology was applied. This four-step quality improvement and management process is typically used for continuous advancement of people and systems within an organisation13–15. PDCA is a successive cycle which starts off small to test potential effects on processes, then gradually leads to larger and more targeted changes13. This framework has been utilised in most of SEHA as a quality program for continuous quality improvement activities (Figure 3).

Figure 3. PDCA cycle

Resources

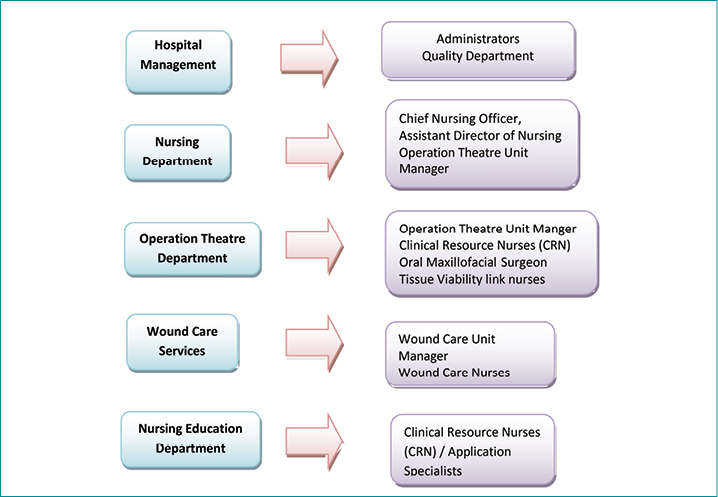

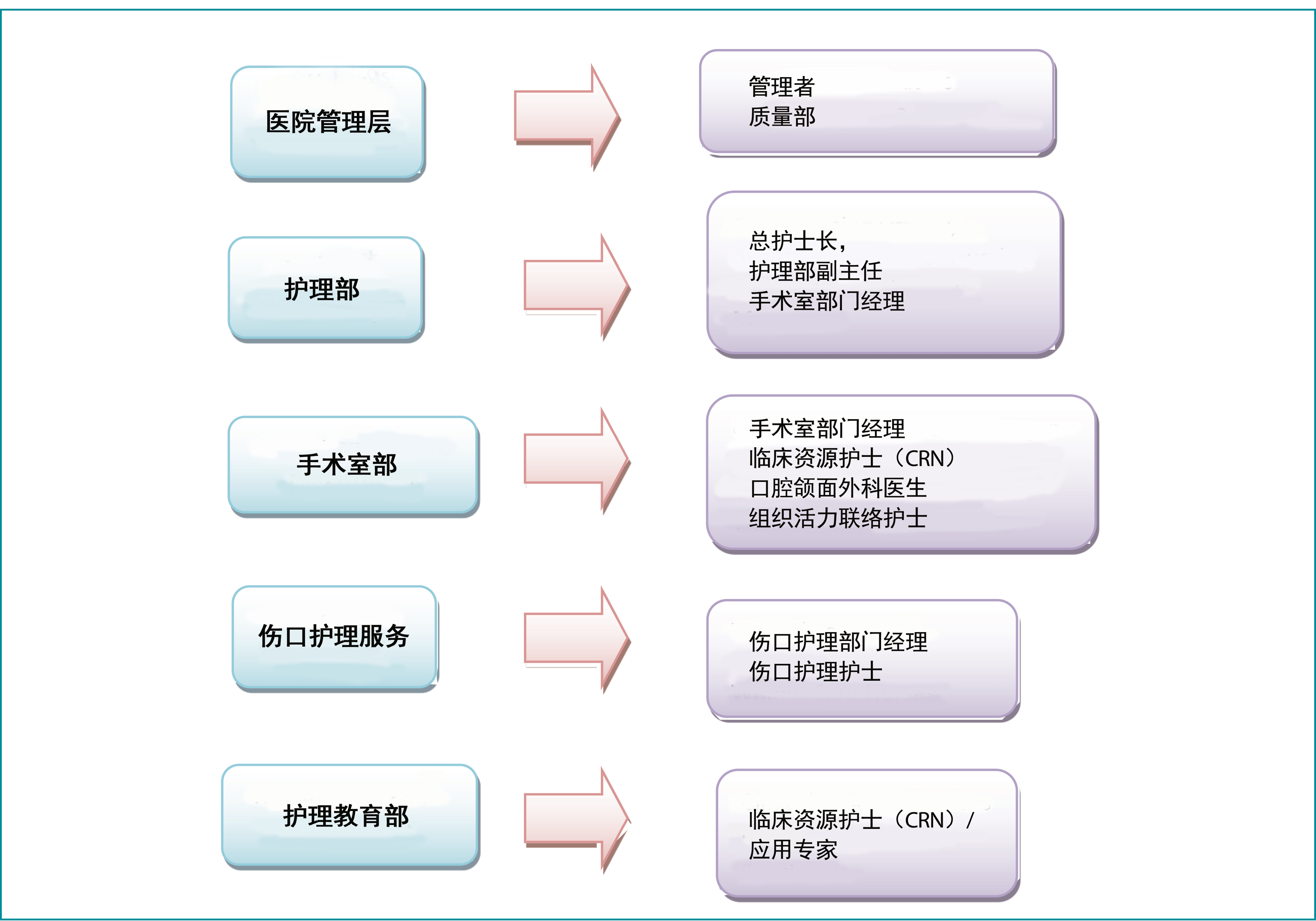

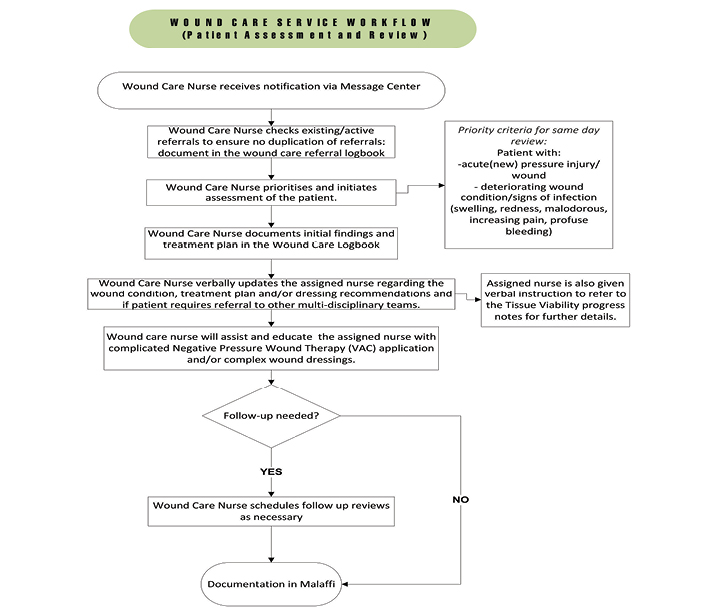

Human resources: several department meetings and consultations with hospital stakeholders were conducted to identify their respective roles and responsibilities for improving the process of preventing PI incidents for all prolonged surgery cases (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Human resources involved

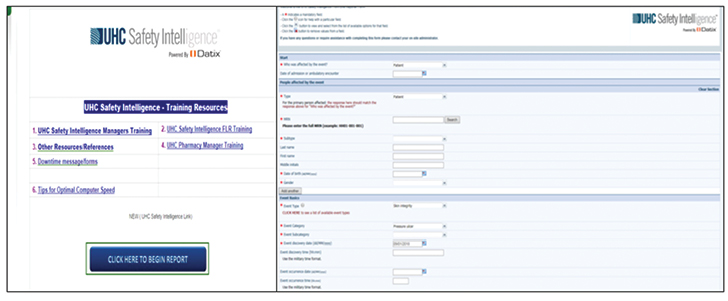

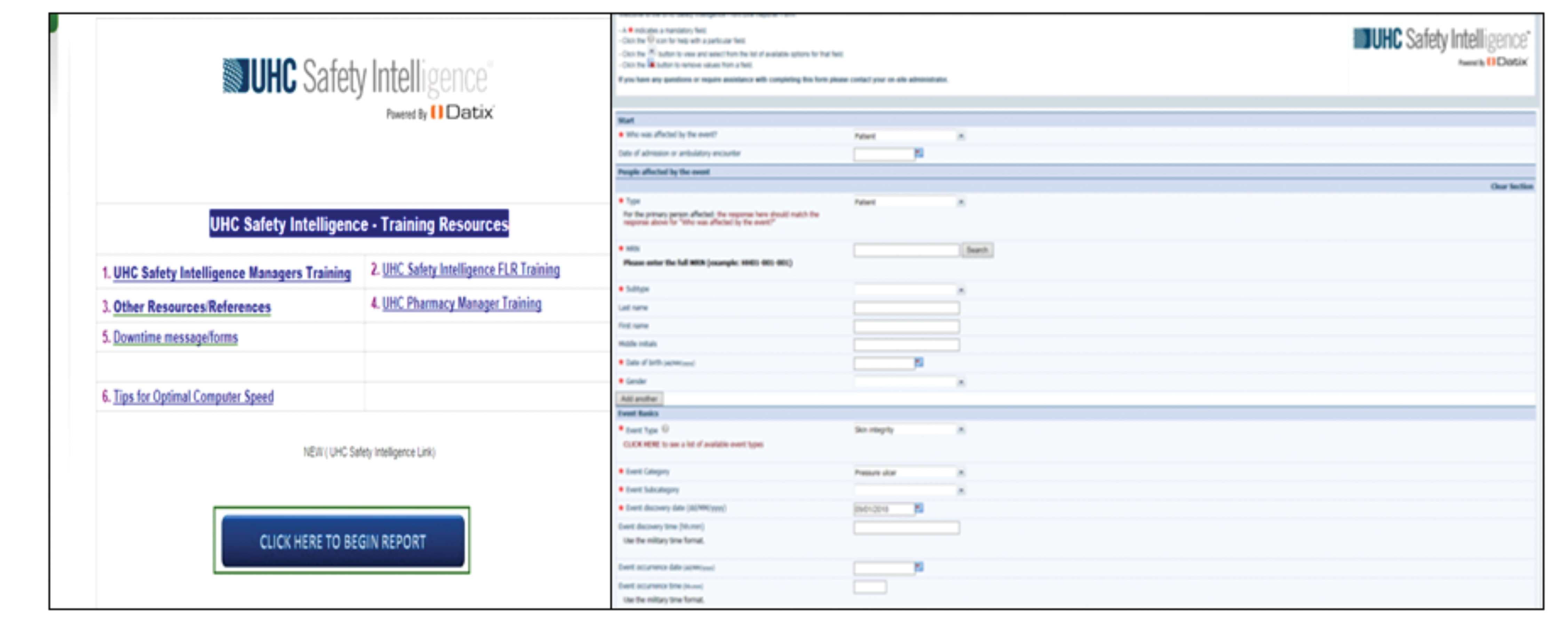

Devices/tool utilised: during the incidence review and data collection period, the approved online incidence reporting tool – the UHC Safety Intelligence (UHC-SI), a real-time, web-based event reporting system – was utilised16 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The UHC-SI tool

Implementation process

PI prevention is vital and is often neglected in the perioperative setting5. A questionnaire was conducted for OT staff to identify the main gaps. Results of RCA from Q1 2018 SI incidences revealed alarming deficits in terms of staff knowledge (PI risk assessment, staging and prevention), system/process (lack of guidelines, risk assessment tool, documentation and resources), appropriate OT table surface, and preventive dressings.

The best practice framework developed by Nelson et al.17 was adopted in the implementation stage of Q1 to achieve the required outcomes in the prevention of HAPIs. This best practice framework was further utilised as a model for Q1 interventions that targets the process of development in four areas – leadership, staff, information, and information technology (IT) – to support the clinician in the process of changing the old practice and adopting best practice of PI prevention and general performance improvement17.

Perioperative nurses should be educated about the risk factors of PI development and safety measures that can be implemented to prevent this injury from occurring18. An appropriate and validated risk assessment tool should be utilised by perioperative nurses to identify patients who are at high risk for developing a PI18–19. All perioperative team members are responsible for the safe positioning of surgical patients. Circulating nurses coordinate the positioning of patients during intraoperative periods of care at our hospital18–20.

In order to respond to gaps identified, our team focused on establishing awareness through assessments of staff knowledge of PI prevention and management21–25. A patient trace was conducted in one of the elective cases undergoing OMF surgery. This allowed us to follow and understand the processes in the pre-, intra- and postoperative care provided to all surgical patients. In addition, accurate assessment, referral in the electronic documentation platform Malaffi – an Abu Dhabi innovative and unified health information exchange platform that facilitates a more patient-centric approach to healthcare provision – and efficient incident reporting were reinforced during the morning huddle, staff meetings and mandatory training. Coordination with the Nursing Education Department (NED) involved the clinical resource nurse (CRN) and application specialist investigating and formulating a risk assessment tool specific to the OT that could be incorporated in Malaffi. Detailed implementation processes were laid out as follows:

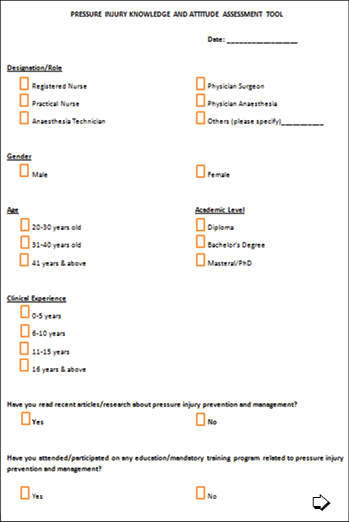

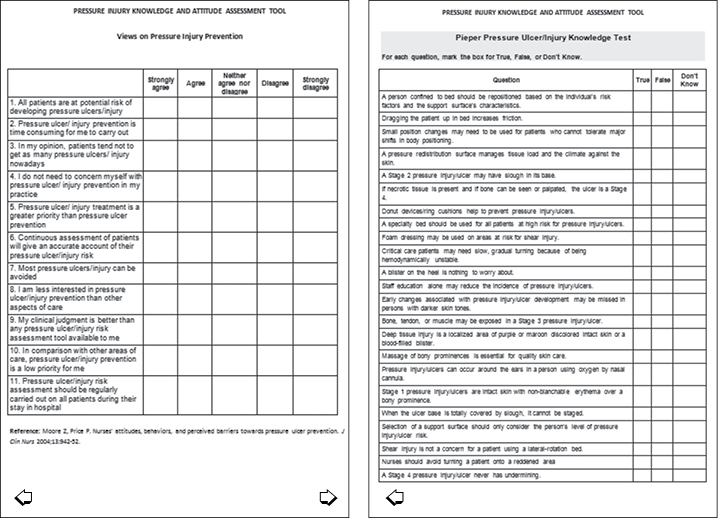

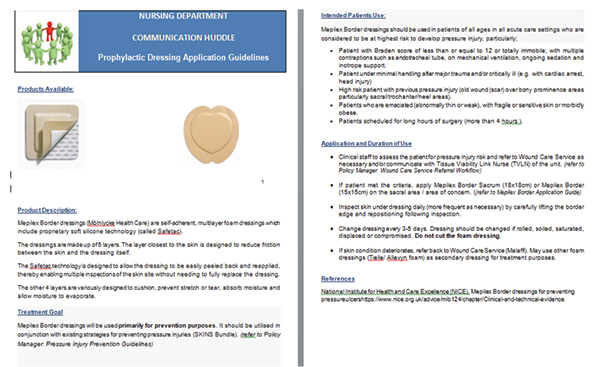

Knowledge assessment and mandatory PI education

Initial evaluations of PI knowledge among OT staff were completed using the Pieper Pressure Injury Knowledge Assessment Survey22–23. Discrepancies in terms of the concepts of PI prevention – use of rings/doughnuts, massaging bony prominences areas – and inaccurate staging were observed24. These gaps were addressed during the two mandatory education sessions conducted in the months of April and May 2018. An additional communication huddle guide was prepared emphasising the Surface/Skin assessment, Keep moving, Incontinence and Nutrition management (SKIN bundle), and the use of preventative dressings was communicated during daily pre-meetings.

Patient tracer and process evaluation

Prior to implementation, the actual process of the perioperative journey was observed by conducting a patient tracer. One patient under OMF who was electively admitted and booked for more than 10 hours of surgery was followed initially from the day surgery unit. Observation was continued from the pre-holding area in the OT until the patient reached surgical ICU postoperatively. Major findings included the lack of a standardised PI risk assessment tool, inconsistent implementation of referral system/consultation to the WCS, and inadequate pressure relieving equipment and supplies available in the OT. These findings were incorporated into the major action plan and communicated with the respective departments.

Early identification of high-risk patients and referral process

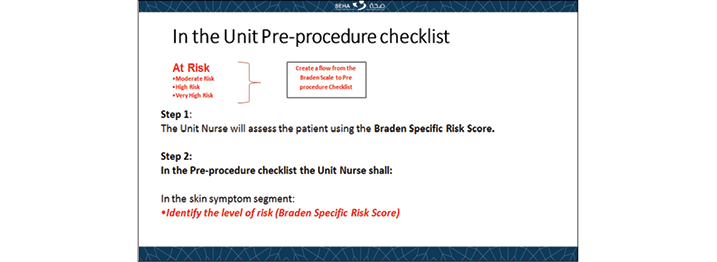

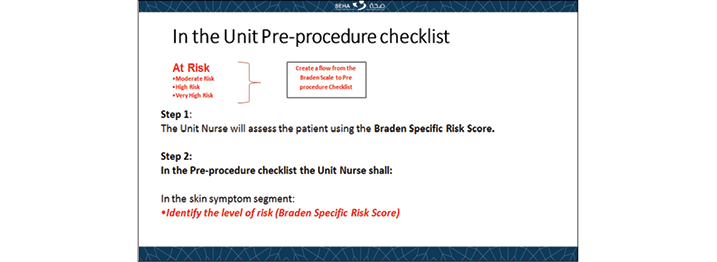

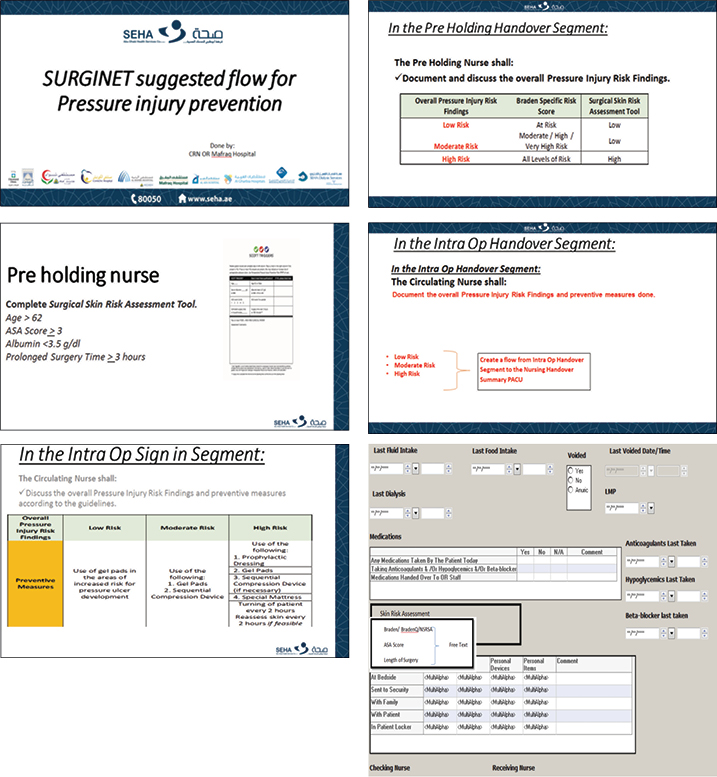

Clinical staff are requested to refer all patients to the WCS who are at risk of developing a PI – using risk assessment scores – and who are undergoing surgical procedures of more than 3 hours. These patients can be referred at any time or immediately after their surgery via the Malaffi. Through this system, OT staff are encouraged to complete accurate skin assessment/re-assessment prior to, during and after surgery by using a newly developed risk assessment tool with an emphasis on clear documentation which is to be reflected in the electronic documentation, the Surginet – MQM Nurse Assess Skin.

Risk assessment tool and recruitment of unit resources

Performing early risk assessment and appropriate interventions can prevent PI development18–25. Due to the lack of a specific PI risk assessment tool to identify the risk status of patients undergoing prolonged surgery in our institution, the project team – in coordination with the OT CRNs – reviewed the possibility of adopting an existing risk assessment scale relevant to the operative period. Multiple discussions and meetings were held to review any existing PI risk assessment tools for the OT.

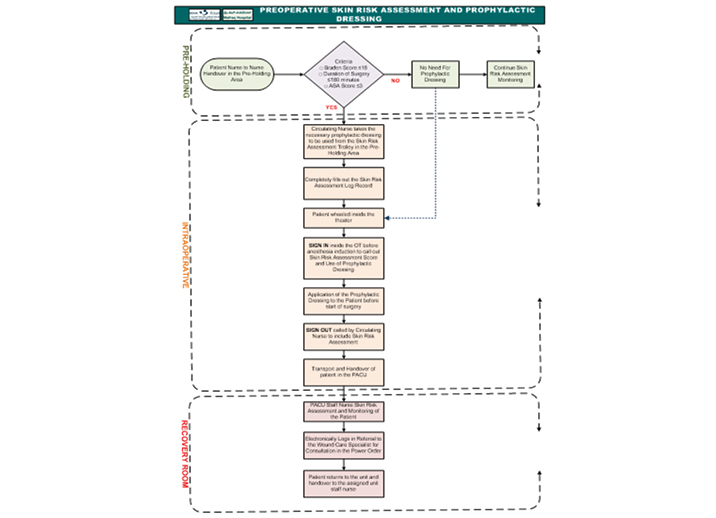

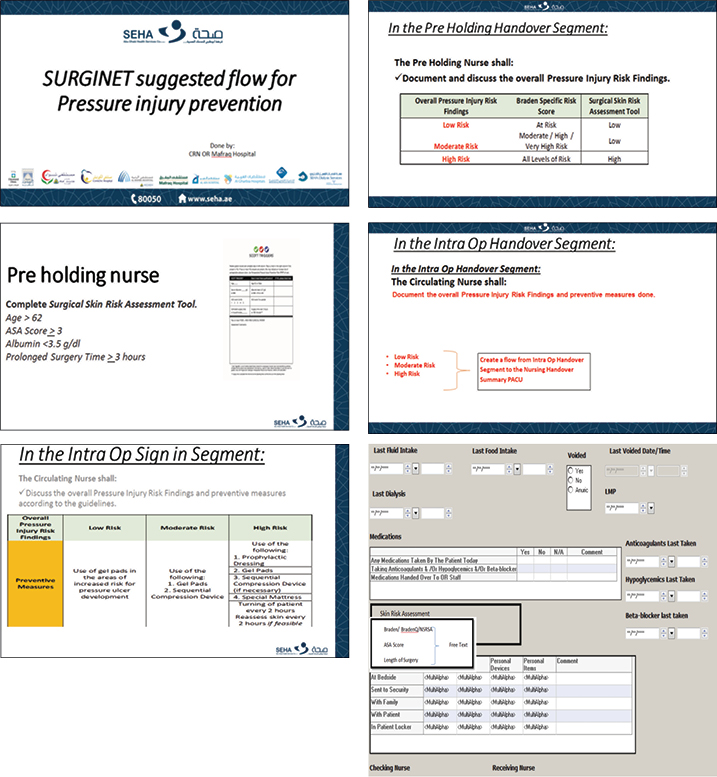

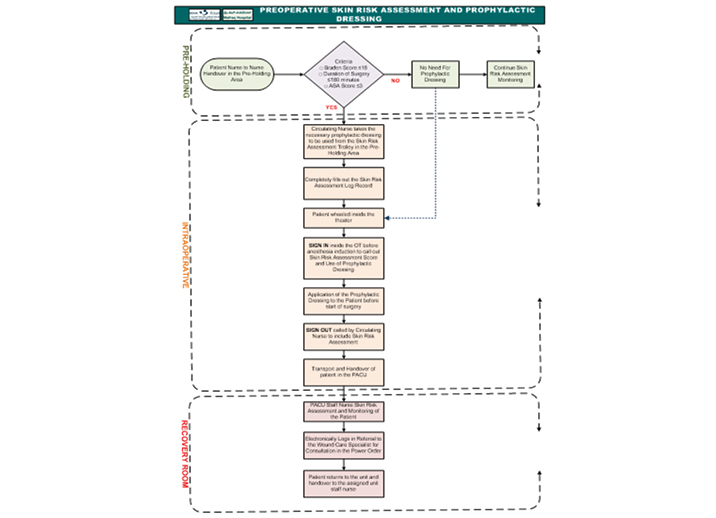

It was decided to incorporate the Scott Triggers tool as part of the skin risk assessment tool. The elements of the Scott Triggers11 tool are: age >62; an ASA score >3; albumin <3.5g/dl; and prolonged surgery time >3 hours. The ASA score is a “global score that assesses the physical status of patients before surgery”10. The CRNs initiated and submitted a proposal to trial the Scott Trigger tool to the Perioperative Nursing Advisory Council Committee. An aim was to investigate the possibility of integrating the tool in the electronic clinical documentation system Surginet, with a further goal of standardising to all other SEHA business entities (see Appendix 3A & 3B). Upon identification of risk using the Scott Triggers tool, a bundled preventive approach or POP program (Prophylactic/Prevention dressing, Offloading devices/equipment and Position changing) would be initiated by OT staff. Completion of the process included accurate hand over between OT or post-anaesthesia care unit (PACU) staff to the receiving unit, with continued referral to the WCS as necessary. Furthermore, two staff from the OT department were nominated to be active members of the tissue viability link nurses group. These individuals will serve as a resource for information in promoting, reinforcing and monitoring PI preventive practices in the OT.

Introduction of preventive dressings and requisition of OT table mattresses

In addition to existing preventative protocols, the project team extended the use of preventive dressings for identified high-risk individuals in the OT. Although wound dressings are not routinely used to prevent PIs, evidence demonstrates that a non-woven, multilayer, polyurethane foam dressing may reduce the effect of shear forces18. Process guidelines were initiated in the OT (see Appendix 4) to keep the preventive dressing materials in a designated cabinet in the pre-holding area. Prophylactic dressing application over bony prominences such as the sacrum and trochanters can be applied in the pre-holding area or prior to sedation and positioning in the OT table to prevent the development of PIs (see Appendix 5).

Inadequate access to pressure relieving equipment and devices was one of the major findings during the tracer exercise. As observed, the operating table, with its hard surface, is only cushioned by gel padding and toppers. Pressure relieving and redistributing devices are widely accepted methods of preventing the development of PIs for people considered at risk26. This equipment may be used in a variety of ways in the OT. Custom-made cushions for the OT tables are necessary to provide adequate support during extended surgeries. These issues have been raised with our facilities’ nurse leaders and cordially communicated with the materials management department for the provision of appropriate foam mattress and additional gel paddings.

Data analysis

The data collected from the SI between 2016 and Q1 2018 were used as a benchmark for the OT improvement project. After initiating the various strategies and methodologies, the team recognised there was a gradual improvement in the incident reports received from Q2–Q4 2018. These outcomes were achieved with the commitment and consistency of all departments adhering to the new system and practices, which included:

- Proper hand over and concurrent skin assessment.

- Identification of high-risk patients.

- Implementation of appropriate prevention measures.

- Earlier referral to the WCS.

Barriers identified by the group

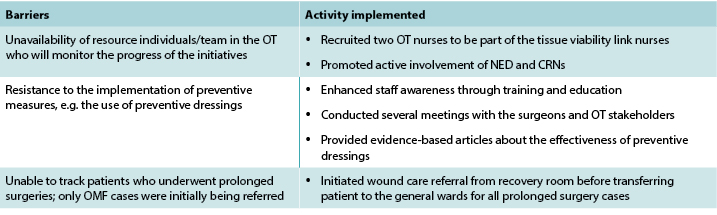

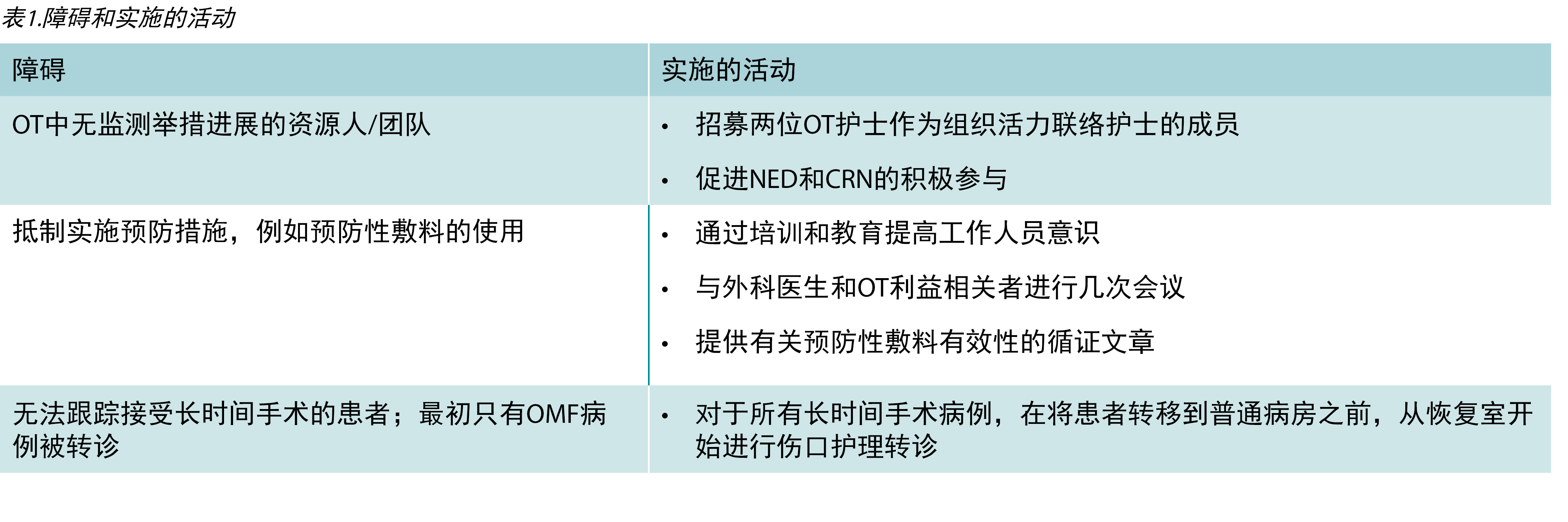

Changing clinical practice can be a challenging process. Throughout the process of the improvement project, the team encountered important barriers and implemented activities to address these. These are outlined in detail in Table 1.

Table 1. Barriers and activities implemented

Project tools

The tools and processes used for the successful completion of quality improvement initiatives are outlined in the appendices:

- Appendix 1 displays the tool used for assessing OT staff knowledge.

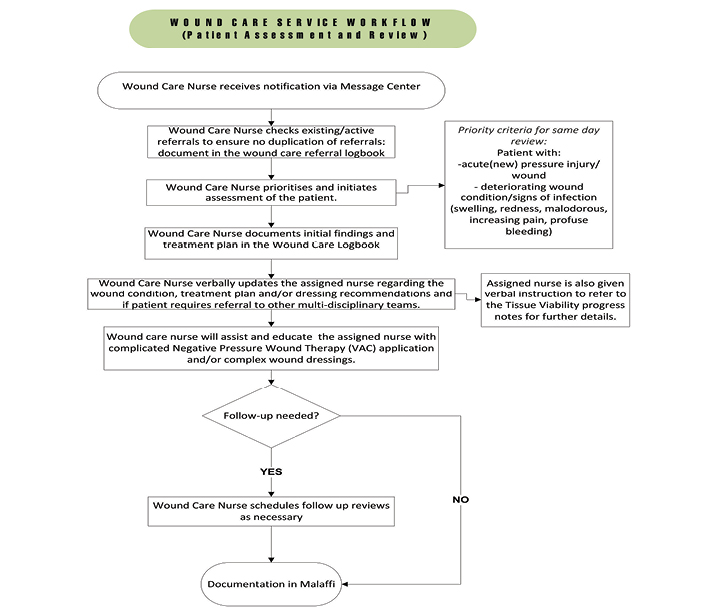

- Appendix 2 (A & B) outlines the referral system to the WCS in the Mafraq Hospital.

- Appendix 3 (A & B) outlines the proposed pre-operative skin risk assessment form.

- Appendix 4 shows the pre-operative skin risk assessment flow chart utilised in the OT.

- Appendix 5 outlines the communication huddle regarding the appropriate use of prophylactic dressings in clinical settings.

Evaluation and Outcomes

Evaluation of the process

In accordance with the sudden increase of PIs reported in the OT from UHC-SI, the WCS decided to reduce these preventable cases of HAPIs. Both quantitative and qualitative data were evaluated to determine the impact of implementing system and process changes in our institution.

Qualitative outcomes

Valuable feedback was received from OT staff and nurse leaders following implementation of this quality improvement initiative. The focus was on the efficiency of the prophylactic dressing, the effectiveness of posters on the OT communication board in alerting staff, and the usefulness of education sessions to reinforce knowledge of all OT staff. Moreover, the reduction of PIs in the OT showed great achievement that positively affected the total number of HAPIs.

Quantitative outcomes

Quantitative data were gathered through incident reports via the SI unit. In addition, the total number of patients who underwent extended surgery time (>3 hours) were gathered through daily referrals. All data were compared between 2016 to Q1 2018 versus Q2–Q4 2018 data to evaluate the effectiveness of the initiative and to be able to identify significant changes between the two data sets.

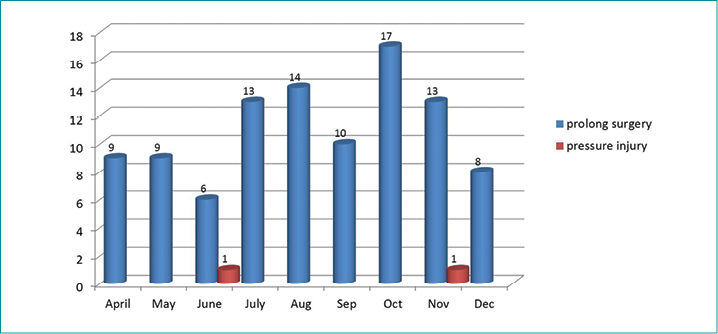

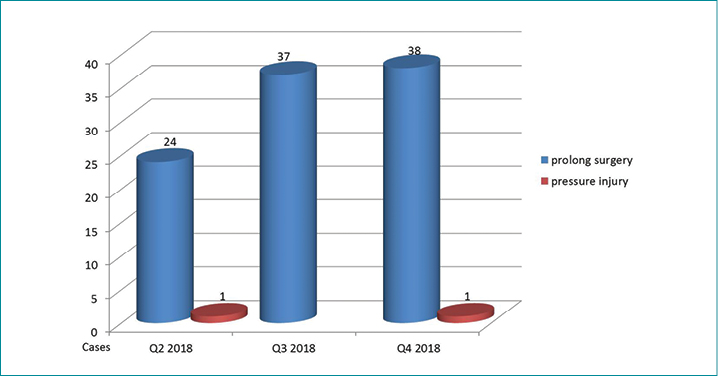

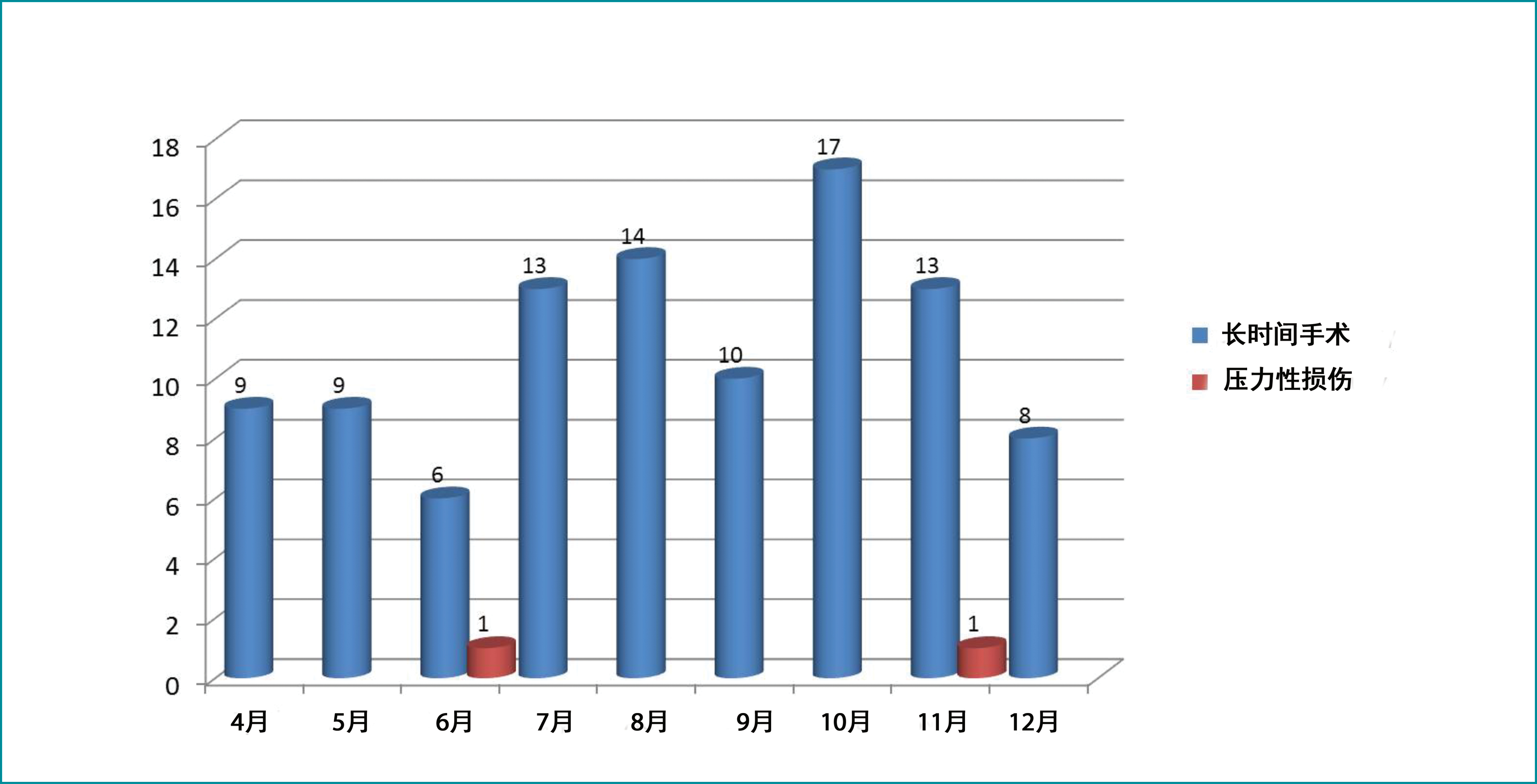

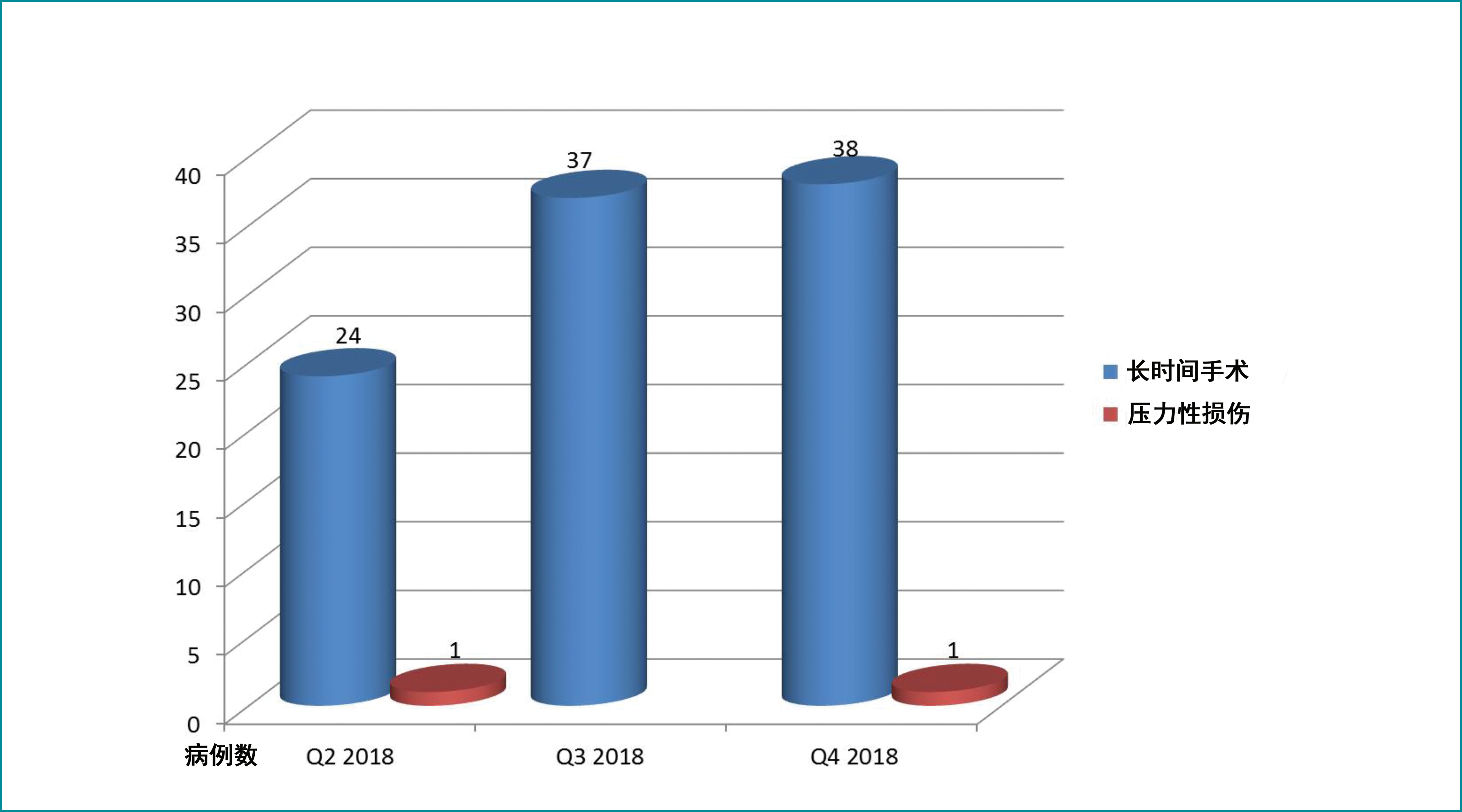

After collecting all reported skin integrity incidence data from 2016 to Q1 2018, monthly data of referrals related to prolonged surgery were generated at the beginning of April 2018. An average of 9–11 patients were initially referred monthly to the WCS for follow-up. A total incidence of two cases were reported; one in the month of June 2018 and one in November 2018 which were in addition to the three cases reported from Q1 2018 (Figures 6 & 7).

Figure 6. Monthly referrals versus OT PI incidents 2018

Figure 7. Quarterly referrals versus OT PI incidents 2018

Within a 9-month period, 99 patients were referred to the WCS. Each of these patients, on average, had spent 7 hours on the operating table. Two cases of PI were reported – in Q2 and Q4 2018. The contributing factors discovered through RCA were poor nutrition, immobilisation, prolonged surgery time (more than 17 hours), presence of multiple comorbidities (chronic renal failure, diabetes), hypoalbuminaemia, haemodynamic instability, and inadequate skin assessment.

Reflection on lessons learned and stimulus for future work

On reflection of the initiation, implementation and outcomes of the quality improvement project, it would be important to:

- Ensure the availability and utilisation of a validated perioperative risk assessment tool is incorporated in the clinical documentation system in all public hospital facilities.

- Include more surgeons and allied healthcare staff from other disciplines in the mandatory education sessions related to the prevention of PIs.

- Conduct regular monthly audits for OT staff to evaluate and ensure continuous implementation of strategies related to the prevention of PIs.

Conclusion

The goal of any healthcare improvement project is to implement realistic action plans that can lead to measurable outcomes and enrich healthcare services offered to patients. As a team, our aim was to decrease HAPI, which required collaboration and commitment with various stakeholders – higher management, patients and healthcare practitioners – through proper communication of common challenges and pressing needs in the clinical setting. At our organisation, the support of key nurses in the perioperative area resulted in a new perspective and attitude towards PI prevention.

In summary, the prevention of HAPIs entails increasing awareness among stakeholders about the importance of early identification of at-risk patients and initiation of preventive measures. Engagement of an inter-professional approach towards quality improvements will ensure a long-lasting impact to both the patient and healthcare system.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

在阿拉伯联合酋长国一家公立医院为接受长时间手术的患者引入压力性损伤预防措施和改进举措的研究

Asha Ali Abdi, Ashwaq Ali, Fatima El-Ahmed

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.3.24-36

摘要

目的

-

发起并实施适当的风险评估工具,用于识别处于压力性损伤(PI)患病风险下的高危长时间手术患者。

- 在手术室(OT)发起有关PI预防和管理的教育和培训。

- 在OT中建立资源人。

- 实现对高危患者的尽早识别并实施预防措施。

方法 对2016年到2017年安全情报(SI)收集的所有皮肤损伤的基线信息(尤其是OT中报告的PI)进行了回顾性数据分析。在完成需求分析后,启动了一个持续质量改进和学习模型,即计划-执行-检查-处理(PDCA)。分析了2016年第1季度(Q1)至2018年第4季度(Q4)实施前后的对比数据。

结果 2018年4月至12月的9个月内,99例患者转诊至伤口护理组,平均手术时间为7小时。在2018年第2季度和第4季度中报告了两例PI。回顾根本原因分析后,发现导致因素与营养不良、长时间卧床不活动、手术时间长(超过17小时)、存在多种合并症(如慢性肾功能衰竭、糖尿病、低蛋白血症和血流动力学不稳定)有关。通过坚持新的系统和实践,取得了改进结果。

结论 预防PI是患者安全和护理质量的一部分,需要具有责任心和责任感、协作、积极主动的团队。

引言

医院获得性压力性损伤(HAPI)是任何医疗机构都会遇到的重大挑战之一,尤其是在重症护理环境中1。这一重大问题凸显发生率和死亡率的不断增加,包括住院时间延长,并对所有医疗系统造成了巨大的经济负担1。根据美国国家压疮顾问小组(NPUAP)的定义2,PI是“由于强大压力和/或长期压力或压力与剪切力的共同作用导致的、通常位于骨突之上或者与医疗器械或其他器械相关的、皮肤和下层软组织的局部损伤”。证据表明,这些PI中有95%是可预防的,因此减少这些PI被视为所有医疗机构的当务之急1。

门诊患者发生PI的高危临床区域之一是手术室(OT)。需要强调的是,接受持续3小时以上手术的患者发生PI的风险很高3。另外,在任何外科手术过程中和/或之后长时间直接施加压力后72小时内,发生在身体骨突上方的任何损伤均被视为PI事件。此外,医疗器械相关性PI是“由于使用设计用于诊断或治疗目的的器械而导致的压力性损伤。所造成的压力性损伤通常与器械的图案或形状非常吻合”3。如果在外科手术过程中出现这种模式的损伤,则也将其视为PI4。研究表明,长时间外科手术引起的HAPI的发生率和患病率分别为5–53.4%和9–21%4。

这种发生率可能与术中固定体位、麻醉类型、手术时间长短以及患者因素(例如年龄、性别)和病史(例如糖尿病和心力衰竭)有关5。外科手术患者的皮损风险要比非外科手术患者高得多,这是因为患者在手术过程中不能活动并且在麻醉过程中缺乏对压觉的意识6。此外,麻醉会降低自主神经系统功能,这反之会扩大血管并减少组织灌注,尤其是在骨突上方;这种效果随着手术时间的延长和全身麻醉的使用而增加7。

与此同时,尚未为外科手术患者正式建立已确认的风险评估量度8。几种工具可用于筛查高危患者。然而,通过对应用于外科手术患者的Braden量表的预测效度进行分析,该量表中缺乏与外科手术相关的风险因素,即患者的手术时间或体位,这使得其预测效度较低6-8。其他工具包括Munro围术期成人患者压疮风险评估量表(Munro量表)和斯卡特触发点工具。Munro量表包括15个项目,用于综合评估术前、术中和术后阶段发生PI的风险因素9-10。斯卡特触发点工具包括四个项目:年龄、血清白蛋白水平、估计的手术时间和美国麻醉医师学会(ASA)评分11。

电子健康记录(EHR)的一个组成部分是由麻醉医师填写的对手术患者麻醉前状况的评价,用于制定有效的麻醉计划。这种评价通常包括手术类型、血清白蛋白水平和ASA评分,这些也是斯卡特触发点工具上的项目。麻醉前评价中的其他数据包括麻醉类型、实验室测试结果(例如血红蛋白和肌酐水平)和合并症(例如高血压和糖尿病),这些对确立用于预测外科手术患者PI发生情况的风险因素的概况或模型非常重要。

尽管研究人员仔细审查了各种预防方法,例如重新调整体位、所用OT床垫的类型,但实施多维方法的有效性尚未得到广泛评价8。因此,对于医疗机构而言,预防和降低HAPI发生率(尤其是在OT中),并且能够提供与地方和国际基准相当的安全有效的护理质量至关重要。应利用适当的衬垫和泄压装置。需要一个支撑面来进行压力的再分布。泡沫衬垫的使用不如保护装置有效,因为它们在沉重的身体区域下容易压缩并导致“触底”。

伤口护理服务:已识别的需求

我们医疗城的伤口护理服务(WCS)于2017年初由两名护士发起。2018年,另外三名护士加入团队,力求处理并进一步加强住院患者临床区域中提供的伤口管理。根据SEHA(阿布扎比健康服务公司,阿拉伯联合酋长国(UAE)所有公立医院和诊所的所有者/运营者)和卫生部(DOH)的指令,PI预防和管理是我们团队的首要目标。为此发布了称为Jawda(阿拉伯语表示“质量”)的具体指南和关键性能指标(KPI),用作数据收集和监测过程的指导12。

2018年第一季度(Q1),3例患者在接受了持续8-14小时的口腔颌面(OMF)手术后报告了HAPI。这导致深度跨专业团队启动了调查和根本原因分析(RCA),以确定这些事件的导致因素。我们对本机构事件报告系统、安全情报(SI)在2016年到2017年收集的所有皮肤损伤的基线信息(包括皮疹、刺激、瘀斑、撕裂、烧伤、擦伤、皮肤撕裂伤)和OT中报告的PI,进行了回顾性数据分析。

2016年,报告皮肤完整性受损21例,其中PI病例报告有13例,2017年,SI报告系统中记录的皮肤损伤事件有11例,其中PI有2例(图1)。此外,从2016年到2018年第1季度,OT中报告的PI事件共18例(图2)。

图1.2016年和2017年OT SI报告

图2.2016年第1季度至2018年第1季度OT中的PI事件(作为SI中报告的原始数据)

结合本机构对患者安全和护理质量的广泛努力,我们选择了这项质量改进举措,以提高PI风险意识,尤其是在OT中。我们旨在与跨专业OT团队成员(OT护士长/工作人员/外科医生)以及由护理、质量和教育部门代表组成的更高级别医院管理层协调,以确定共同的导致因素并对当前的实践和程序进行评价。

质量改进目标和目的

目标是降低长时间手术引起的PI的发生率。制定以下目标是为了解决OT中长时间手术引起的HAPI发生率上升。具体而言,本研究旨在:

- 识别导致手术人群在围手术期中发生PI的因素。

- 通过以下方式实施PI预防措施:

- 尽早识别高危患者和采用适合的特定风险评估工具。

- 对所有OT工作人员启动有关PI预防和管理的在职教育和培训。

- 针对围手术期患者,制定关于PI预防和管理的指南和政策。

- 授权将担任资源人的OT工作人员,并监测与PI事件相关的改进/进展。

项目方法

计划和实施

需求分析完成后,应用计划-执行-检查-处理(PDCA)法。这一四步法质量改进和管理过程通常用于组织内人员和系统的持续提升13-15。PDCA是一个连续的循环,从小规模开始,测试对过程的潜在影响,然后逐步引向更大、更具针对性的变革13。该框架已被SEHA的大多数成员用作持续质量改进活动的质量计划(图3)。

图3.PDCA循环

资源

人力资源:举行了几次部门会议并与医院利益相关者进行了磋商,确定他们相应的角色和职责,以改进预防所有长时间手术病例的PI事件的过程(图4)。

图4. 涉及的人力资源

使用的器械/工具:在发生率审查和数据收集期内,使用了获批准的在线发生率报告工具–UHC安全情报(UHC-SI),一个基于网络的实时事件报告系统16(图5)。

图5.UHC-SI工具

实施过程

PI预防至关重要,但在围手术期环境中经常被忽略5。对OT工作人员进行问卷调查,以确定主要差距。2018年第1季度SI事件的RCA结果显示,在工作人员知识(PI风险评估、分期和预防)、系统/过程(缺乏指南、风险评估工具、文件记录和资源)、适宜的OT手术台表面和预防性敷料方面存在严重不足。

在第一季度的实施阶段采用了Nelson等人17开发的最佳实践框架,以实现HAPI预防中要求的结局。该最佳实践框架被进一步用作第一季度干预的模型,其针对四个领域(领导力、工作人员、信息和信息技术[IT])的发展过程,目的是支持临床医生改变旧的实践并采用PI预防和总体绩效改进的最佳实践17。

围手术期的护士应接受关于PI发生的风险因素和可实施用于预防这种损伤发生的安全措施的教育18。围手术期护士应使用适当且经过确认的风险评估工具来识别有发生PI高风险的患者18-19。所有围手术期团队成员负责手术患者的安全体位。巡回护士在我院术中护理期内协调患者的体位18-20。

为了应对所识别的差距,我们的团队致力于通过评估工作人员有关PI预防和管理的知识来建立其的意识21-25。在行OMF手术的其中一例择期病例中进行了患者跟踪。这使我们能跟踪和了解向所有手术患者提供的术前、术中和术后护理中的过程。此外,在晨会、工作人员会议和强制性培训过程中加强了准确评估、在电子文档平台Malaffi(阿布扎比市一个创新和统一的卫生信息交流平台,促进更加以患者为中心的医疗保健服务)中的转诊和高效的事件报告。与护理教育部(NED)的协调涉及临床资源护士(CRN)和应用专家,他们研究制定可纳入Malaffi的、针对OT的风险评估工具。详细的实施过程安排如下:

知识评估和强制性PI教育

使用Pieper压力性损伤知识评估调查完成了对OT工作人员间PI知识的初始评价22-23。发现PI预防的概念(使用环形/甜甜圈形垫子、按摩骨突区)存在差异且分期不准确24。这些差距在2018年4月和5月进行的两次强制性教育课程中得到了解决。另外还准备了一份沟通会议指南,强调表面/皮肤评估、保持移动、失禁和营养管理(皮肤护理组合),并在每日预会中说明了应使用预防性敷料。

患者跟踪程序和过程评价

在实施前,通过进行患者跟踪程序来观察围手术期过程的实际过程。对一例择期入院并预约了超过10小时手术的行OMF患者,从门诊外科病房开始对其进行跟踪。术后,从OT中的准备区域继续开始观察,直到患者到达外科ICU。主要发现包括缺乏标准化的PI风险评估工具、对WCS转诊系统/会诊的实施不一致、以及OT中可用的泄压设备和用品不足。这些发现已纳入主要行动计划,并与相应部门沟通。

高危患者的尽早识别和转诊过程

要求临床工作人员将所有存在发生PI风险(使用风险评估评分判断)和进行的外科手术超过3小时的患者转诊至WCS。这些患者可在任何时间或手术后立即通过Malaffi进行转诊。通过该系统,鼓励OT工作人员在术前、术中和术后通过使用最新开发的风险评估工具完成准确的皮肤评估/再评估,该工具强调进行清晰的文件记录,而这些文件记录将会反映在电子文档(Surginet–MQM Nurse Assess Skin)中。

风险评估工具和部门资源的招募

进行早期风险评估和适当的干预可以预防PI发生18-25。由于缺乏专门的PI风险评估工具来确定本机构中接受长时间手术的患者的风险状态,因此项目团队与OT CRN合作,审查了采用与手术期相关的现有风险评估量表的可能性。召开了多次讨论和会议,审查OT现有的所有PI风险评估工具。

决定纳入斯卡特触发点工具作为皮肤风险评估工具的一部分。斯卡特触发点11工具的要素:年龄>62;ASA评分>3;白蛋白水平<3.5g/dl;和长时间手术>3小时。ASA评分是一个“评估患者术前身体状况的整体评分”10。CRN发起并向围手术期护理咨询理事会委员会提交了试用斯卡特触发点工具的提案。目的是研究将该工具集成到电子临床文档系统Surginet中的可能性,进一步的目标是标准化应用至所有其他SEHA企业实体(参见附录3A & 3B)。使用斯卡特触发点工具识别风险后,OT工作人员将启动组合式预防措施或POP计划(预防性药物/预防性敷料、减压器械/设备和体位改变)。过程的完成包括OT或麻醉后恢复室(PACU)工作人员与接收部门之间准确地移交,并在必要时继续转诊至WCS。此外 ,两名OT部门的工作人员被提名为组织活力联络护士组的积极成员。这些个体将充当有关促进、加强和监控OT中PI预防实践的信息资源。

引入预防性敷料和请购OT手术台床垫

除了现有的预防性方案外,项目团队还将预防性敷料的使用扩大至OT中已识别的高危个体。虽然不将伤口敷料常规用于预防PI,但证据表明,多层无纺布聚氨酯泡沫敷料可以减少剪切力的影响18。在OT中启动了过程指南(参见附录4),将预防性敷料材料存放在准备区域内规定的柜子中。应用于骨突上方(例如骶骨和转子)的预防性敷料可在准备区域中或镇静以及在OT手术台中定位前施用,以预防PI的发生(参见附录5)。

跟踪活动期间的主要发现之一是无法充分获取泄压设备和器械。据观察,手术台表面很硬,仅垫有凝胶垫料和顶部垫料。泄压和压力再分布器械是广泛接受的方法,用于预防风险人群发生PI26。这种设备可在OT中以多种方式使用。必须使用为OT手术台定制的垫子,以便在长时间手术过程中提供充分的支持。这些问题已向本院的护士长提出,并与材料管理部门进行了友好沟通,以供应适宜的泡沫床垫和额外的凝胶衬垫。

数据分析

从SI收集的2016年至2018年第1季度的数据被用作OT改进项目的基准。在启动了各种策略和方法后,研究团队发现在2018年第2季度到第4季度收到的事件报告中存在逐渐改进。这些结局是在所有部门致力于遵循新系统和实践并始终一致的坚持下实现的,其中包括:

- 正确移交患者并同时进行皮肤评估。

- 识别高危患者。

- 实施适当的预防措施。

- 尽早转诊至WCS。

小组识别的障碍

改变临床实践可能是一个具有挑战性的过程。在改进项目的整个过程中,团队遇到了重大的障碍,并实施了一些活动来解决这些障碍。这些在表1中详细概述。

表1.障碍和实施的活动

项目工具

附录中概述了用于成功完成质量改进举措的工具和过程:

- 附录1展示了用于评估OT工作人员知识的工具。

- 附录2(A & B)概述了马弗拉克医院的WCS转诊系统。

- 附录3(A & B)概述了建议的术前皮肤风险评估表。

- 附录4显示了OT中使用的术前皮肤风险评估流程图。

- 附录5概述了有关在临床环境中适当使用预防性敷料的沟通会议。

评价和结局

过程评价

由于UHC-SI报告的OT中的PI突然增加,WCS决定减少这些可预防的HAPI病例。本研究同时评价了定量和定性数据,以确定在本机构实施系统和过程变更的影响。

定性结局

在实施这项质量改进举措后,收到了来自OT工作人员和护士长的宝贵反馈。重点是预防性敷料的效率、OT沟通板上的海报在提醒工作人员方面的有效性,以及教育课程对增强所有OT工作人员的知识的有用性。而且,OT中PI的减少显示出巨大的成就,对HAPI的总数产生了积极的影响。

定量结局

经SI部门通过事件报告收集定量数据。此外,通过每日转诊收集进行长时间手术(>3小时)的患者总数。将2016年至2018年第1季度的所有数据与2018年第2季度至第4季度的数据进行比较,以评价该举措的有效性,并能够确定两个数据集之间的重大变化。

在收集了2016年至2018年第1季度所有报告的皮肤完整性发生率数据后,于2018年4月初生成了与长时间手术相关的月度转诊数据。最初平均每月有9-11例患者转诊至WCS进行随访。报告的总发生率为两例;除2018年第1季度报告的三例外,2018年6月和2018年11月各1例(图6 & 7)。

图6. 2018年的月度转诊和OT PI事件

图7. 2018年的季度转诊和OT PI事件

在9个月内,99例患者转诊至WCS。这些患者在手术台上进行手术的时间平均为7个小时。2018年第2季度和第4季度报告了两例PI。通过RCA发现的导致因素是营养不良、卧床不活动、长时间手术(超过17小时)、存在多种合并症(慢性肾功能衰竭、糖尿病)、低蛋白血症、血流动力学不稳定和皮肤评估不充分。

经验教训的反思和对未来工作的激励

在反思质量改进项目的启动、实施和结局时,重要的是:

- 确保所有公立医院机构的临床文档系统中包含经过确认的围手术期风险评估工具的选择和对其的利用。

- 让更多其他学科的外科医生和联合医疗保健人员参加与PI预防相关的强制性教育课程。

- 每月对OT工作人员进行一次定期审核,以评价和确保PI预防相关策略的持续实施。

结论

任何医疗保健改进项目的目标都是实施可以带来可衡量的结局,并丰富为患者提供的医疗保健服务的现实行动计划。作为一个团队,我们的目标是减少HAPI,这需要通过适当沟通临床环境中的共同挑战和迫切需求,从而与不同利益相关者(更高管理层、患者和医疗保健医生)达成协作和承诺。在本组织中,围手术期领域关键护理人员的支持使我们对PI预防有了新的看法和态度。

总之,HAPI预防需要提高利益相关者对早期识别高危患者和启动预防措施的重要性的意识。采用跨专业方法实现质量改进将确保对患者和医疗保健系统产生长期影响。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者在本研究中未收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Asha Ali Abdi

RN, BSN, MSc Healthcare Management, IIWCC

Mafraq Hospital, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Emailashaaliabdi22@gmail.com ashaaliabdi22@gmail.com

Ashwaq Ali*

RN, Diploma, IIWCC

Mafraq Hospital, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Email ashwaqalinuuh@gmail.com

Fatima El-Ahmed

RN, BSN, IIWCC

Mafraq Hospital, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Email fatimekasem2018@gmail.com

* Corresponding author

References

- Graves N, Birrell F, Whitby M. Effect of pressure ulcers on length of hospital stay. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2005;26(3):293–297.

- National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP). Pressure injury stages. Available from: http://www.npuap.org/resources/educational-and-clinical-resources/npuap-pressure-injury-stages/

- Pressure ulcers get new terminology and staging definitions, Nursing: March 2017 - Volume 47 - Issue 3 - p 68-69 doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000512498.50808.2b.

- Black J. The operating room. 2015 National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Available from: http://www.npuap.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/2.-Patients-in-the-OR-J-Black.pdf

- Wensing M, Bosch M, Grol R. Developing and selecting interventions for translating knowledge to action. CMAJ 2010;182:E85–8.

- Walton-Geer PS. Prevention of pressure ulcers in the surgical patient. AORN J 2009;89(3):538–552.

- Girouard K, Harrison MB, VanDenKerkof E. The symptom of pain with pressure ulcers: a review of the literature. OWM 2008;54:30‑40,42.

- He W, Liu P, Chen HL. The Braden Scale cannot be used alone for assessing pressure ulcer risk in surgical patients: a meta-analysis. Ostomy Wound Manage 2012;58(2):34–40.

- Hwang HY, Shin YS, Cho HS, Yeo JS. Risk factors of pressure sore in patients undergoing general anaesthesia. Korean J Anaesthesiol 2007;53(1):79–84.

- Munro CA. The development of a pressure ulcer risk-assessment scale for perioperative patients. AORN J 2010;92(3):272–287.

- Scott SM. Progress and challenges in perioperative pressure ulcer prevention. J WOCN 2015;42(5):480–5.

- Department of Health (DOH) / Health Authority of Abu Dhabi (HAAD). HAAD JAWDA quality performance KPI profile. 2015. Available from: https://www.haad.ae/HAAD/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=j73CZWI86MU%3D&tabid=1450

- Chandrakanth K. Plan Do Check Act (PDCA) improving quality through agile accountability. Available from: https://www.agilealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/PDCA.pdf

- World Health Organization. Bridging the “Know–Do” gap. Meeting on Knowledge Translation in Global Health. 2005 October 10–12; Geneva (Switzerland).

- Kitson A, Staus SD. The knowledge-to-action cycle: identifying the gaps. CMAJ 2010;182(2):E73–7.

- Al Mafraq Hospital. Policy Manager: UHC Safety Intelligence Policy. 2012 July. Available from: http://portal.seha.ae/mafraq/DMS/Quality%20and%20OHS/INCIDENT%20MANAGEMENT%20POLICY.pdf

- Nelson EC. Success characteristics of high performing microsystems: learning from the best. In Nelson EC, Batalden PB, Godfrey MM, editors. Quality by design: a clinical microsystems approach. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 2007.

- World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS). Consensus Document. Role of dressings in pressure ulcer prevention. Wounds Int 2016;29:9–12. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.17422.77123

- McKibbon KA, Lokker KA, Lokker C, et al. A cross-sectional study of the number and frequency of terms used to refer to knowledge translation in a body of health literature in 2006: a Tower of Babel? Implement Sci 2010;5:16.

- Delmore B, Lebovits S, Suggs B, Rolnitzky L, Ayello EA. Risk factors associated with heel pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients. J WOCN 2015;42(3):242–8.

- Straus SE, Tetroe JM, Graham ID. Knowledge translation is the use of knowledge in health care decision making. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:6–10.

- Delmore B, Ayello EA, Smart H, Sibbald RG. Assessing pressure injury knowledge using the Pieper-Zulkowski pressure ulcer knowledge test. Adv Skin & Wound Care 2018;31(9):406–12.

- Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Lavia J, Hill S, Squires J. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci 2012;7:50.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Translating Research Into Practice (TRIP) Y II. 2001 [cited 2018 Aug 10]. Available from: https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/translating/tripfac/ trip2fac.pdf.

- Lewis-Byers K, Thayer D. An evaluation of two incontinence skin care protocols in a long-term care setting. OWM 2002;48(12):44–51.

- Huang HY, Chen HL, Xu XJ. Pressure-redistribution surfaces for prevention of surgery-related pressure ulcers: a meta-analysis. OWM 2013;59(4):36–8.

Appendix 1. Knowledge Assessment Tool

Appendix 2A. Wound Care service referral workflow

Appendix 2b. Wound care service patient assessment and workflow

Appendix 3A. OT Pre-operative skin risk assessment

Appendix 3b. Proposed modification in pre-operative checklist with addition of skin risk assessment in malaffi

Appendix 4. Preoperative skin risk assessment flow chart

Appendix 5. Communication huddle regarding the use of prophylactic dressing

附录1. 知识评估工具

附录2A. 伤口护理服务转诊工作流

附录2B. 伤口护理服务患者评估和工作流

附录3A. OT术前皮肤风险评估

附录3B.对术前检查表的建议修改以及MALAFFI中皮肤风险评估的增加

附录4. 术前皮肤风险评估流程图