Volume 40 Number 4

Parastomal hernia: improving quality of life, restoring confidence and reducing the fear. The importance of the role of the stoma nurse specialist

Sarah Russell

Keywords quality of life, exercise, education, Parastomal hernia, stoma nurse

For referencing Russell S. Parastomal hernia: improving quality of life, restoring confidence and reducing the fear. The importance of the role of the stoma nurse specialist. WCET® Journal 2020;40(4):36-39

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.4.36-39

Abstract

This article provides an overview of qualitative comments regarding parastomal hernia (PSH) taken from a survey of ostomy patients in the UK in 2018. This article also considers the importance of the role of the stoma nurse specialist in improving quality of life (QoL), reducing fear, and restoring confidence in patients with a stoma and/or a PSH.

Introduction

A parastomal hernia (PSH) is a common complication after stoma surgery. The true incidence is not known, but prevalence is estimated to be approximately 25–30% at 12 months post-surgery1 and 50% or higher after 2 years, and many clinicians feel that PSH may be inevitable in time1–5. In general, there is a lack of quality research about the history, risk factors and causes of PSH and a lack of consensus about prevention and treatment3, although clinical trials, in particular the CIPHER study, are underway to address this issue.

Although not conclusive, key risk factors for PSH development are generally considered as male gender, age (over 60), surgical complications/technique, having an end colostomy, previous steroid or chemotherapy treatment, obesity (BMI >25), smoking, COPD/respiratory condition and weak abdominal muscles6–10. Previous studies show a trend towards physical inactivity after stoma formation, with the fear of a PSH being a major deterrent to living an active life11. Other studies (by the author of this paper) showed that 40% of patients reported becoming less physically active after stoma surgery but, in those with a diagnosed PSH, this increased significantly to 53%12,13.

Comments from patients from these studies concluded that ‘making the hernia’ worse or a lack of advice about living with a PSH were significant factors in reduced quality of life (QoL) and physical inactivity13. Patients generally (confirmed by comments below) report feeling fearful and unsure of activities they can safely do to reduce their risk of developing a PSH, and are unclear of what to do when they have a diagnosis of PSH, leading to a sense of fear and vulnerability. Patients often anecdotally report being told not to do abdominal exercises, to be cautious of exercise and lifting, and to ‘be careful’ in case they develop a PSH, further compounding the issue and leading to a cycle of fear, activity avoidance and reduced QoL.

Qualitative patient comments

Survey responses were gathered from 1,500 people with stomas in the UK in 2018. The following comments are taken directly from the survey comments:

I’m scared to do too much exercise as it makes my stoma/hernia sore and I don’t know how much I can push myself.

Personally, I wish I had been advised about hernias and how to prevent them from the beginning, prevention being better than cure.

I’d love to know do’s and don’ts of exercise with a hernia.

I think more information is needed in this area. Both with reference to abdominal exercises, and also how to engage in more vigorous activities safely.

The most I was told was no heavy lifting for 6 weeks, nothing more than a full kettle. But after that? Who knows... after care should include visits to physios with stoma knowledge and experience.

I am scared to do exercise in case I get a hernia.

It would be good to be advised on what exercises one should or shouldn’t do in order to improve one’s health/strength or avoid injury/hernia.

Too often patients are not being advised of do’s and don’ts after a hernia repair resulting in a hernia returning, physical rehabilitation after surgery should be standard practice.

I would like to know how to strengthen my stomach muscles without risking provoking a serious hernia.

I am VERY angry that I was given NO information on how to prevent or minimize a hernia until I insisted. I only found out about how I could help myself by referring to the internet. Unfortunately, too late to support my ever-growing hernia.

I worry about getting hernia, it is difficult to know when exercise is too much

These comments, which are representative of the most common responses, indicate a common theme of fear and misinformation, and a palpable desire for better advice about PSH and safe exercise/rehabilitation after stoma surgery. These comments, together with findings from other studies11, show a clear trend towards ‘fear avoidance’14 in patients with stomas, but more particularly those diagnosed with a PSH.

How can the stoma nurse specialist help?

The stoma nurse specialist is in a unique position to be able to re-educate and support, reducing patients’ feelings of anxiety and fear, ultimately improving confidence, activity levels and QoL15. In this section we suggest three ways this can be done:

- Using a person-centred approach.

- Using strength-based language.

- Implementing an appropriate therapeutic rehabilitation exercise programme

Providing clear, evidence-based advice about PSH (reduction of risk as well as PSH management), in line with clinical guidelines published by the Association of Stoma Care Nurses (ASCN) UK6 is without question. Modifiable risk factors, as stated in the ASCN guidelines, can be sensitively discussed with patients, in particular weight loss and smoking cessation. This advice should also include the introduction of – or signposting to – an appropriate therapeutic rehabilitation programme before or after surgery. This could be in the form of booklets, online videos, appropriate cancer or stoma rehabilitation classes or 1:1 instruction. Stoma nurses should ensure educational materials are made available such as those produced by charities (Ileostomy Association and Macmillan) and stoma bag manufacturers, and those highlighted in the ASCN clinical guidelines. Ideally, they should also be able to demonstrate suitable exercises to their patients. However, the way in which this advice and information is delivered, and the language used, may have a profound effect on how a patient feels about PSH16. It’s important that patients don’t feel guilt or shame, nor that they somehow caused their hernia.

Person-centred approach

A person-centred approach takes a holistic view of a patient, considering not only their medical condition, but their psychological and social needs as well as personal preferences, hobbies and interests17,18. It places any medical condition or disability in the context of the whole person. This is important when discussing PSH with a patient. Consider the effect that unintentionally cautious advice may have on the person.

In this case study example, Patient A (a 75-year-old man with a colostomy) had been told to avoid playing golf in case it made his PSH worse. This advice was given quickly in the clinic, almost as a throw away comment and was given with kindness and in good faith but had the effect of being devastating. Golf was Patient A’s life. He was the chairman of the golf club and had played his whole life. He had even chosen to buy a house backing onto the golf course. It was his vital lifeline for his social life and his mental and physical wellbeing. To be told not to play ever again was confusing and damaging for his physical and mental wellbeing.

Instead, a person-centred approach would have meant providing modifications to enable him to play golf more safely, for example doing abdominal core exercises, showing the correct technique when lifting his clubs, using a buggy on the course, and wearing of support garments if he felt it was helpful.

Strength-based language

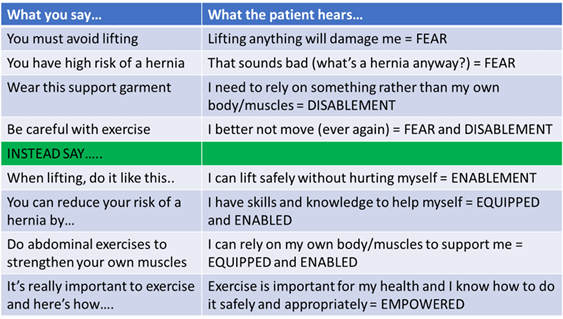

Strength-based language emphasises people’s strengths, abilities and opportunities, instead of their challenges, conditions or perceived deficiencies16. It focuses on providing advice about what someone can do, rather than the things they should avoid (Figure 1). However, it is easy to fall into unintentional negative language when attempting to provide caring, cautious advice.

Figure 1. Some examples of strength-based language (created by the author)

When discussing PSH with a patient, using ‘strength-based’ language would mean using positive language and focussing on patient-centred modifications, emphasising things they CAN do rather than things they CAN’T. This enables patients, giving them the confidence to self-manage their PSH, empowering them and reducing their fear.

This simple change can make a fundamental difference to the way in which a patient adapts to life with a stoma or PSH, and could be the key to them moving out of the ‘fear avoidance’ cycle, reducing fear and improving QoL.

Therapeutic rehabilitation exercise programme

Finally, the implementation of an appropriate therapeutic exercise-based rehabilitation programme can be a powerful tool to help patients restore confidence in their body, reduce fear, and improve QoL19–21.

This recommendation is in line with UK ASCN clinical guidelines6. These guidelines state that appropriate ‘core’ exercises can be commenced as soon as 3–4 days post-surgery. If possible, they can also be implemented BEFORE surgery as a form of ‘prehabilitation’. Suitable exercises are illustrated in the UK ASCN clinical guidelines. Other suitable programmes and exercises could be sourced from hospital physiotherapists, stoma charities or stoma bag manufacturers. The me+recovery programme from ConvaTec22 is a three-phase programme, approved by ASCN, the Royal College of Nursing and the Association of Coloproctology GB and Ireland. It provides a range of exercises suitable for anyone at any stage of surgical recovery.

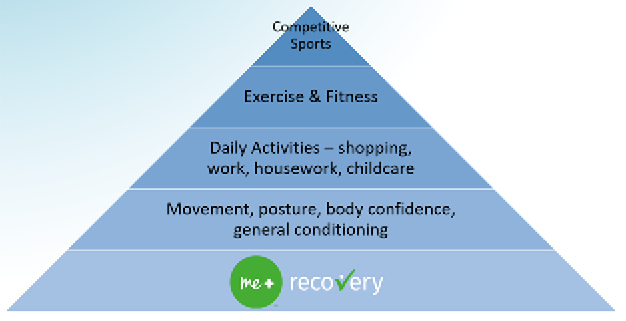

Through such simple exercise programmes, patients can regain normal movement patterns, improve core and pelvic floor function and control, and learn to move with more confidence20. Core abdominal exercises can give people a sense of control and stability and can be key in living with both a stoma and/or PSH. Suitable core abdominal exercises for people with a stoma involve simple tightening of the deep core and pelvic floor muscles and movements such as pelvic tilts and knee rolls whilst lying on their back. These exercises have their foundation in clinical Pilates and are similar to post-natal exercises. The goal is to gain control, connection and function of the deep core muscles and pelvis. Figure 2 shows how this foundation phase is important for all, restoring function, confidence, movement and physical fitness.

Figure 2. The foundation phase of the me+recovery programme from ConvaTec22

A suitable therapeutic exercise rehabilitation programme should include a range of rehabilitation exercises that can be done immediately post-surgery. It should also have options to progress as the patient improves and regains condition. This also helps with motivation and engagement. It should also offer a wide range of adaptations and modifications for patients who wish to exercise in a chair, when standing, or on a bed19-21.

In line with person-centred care, each patient should also have the opportunity to choose the exercises that they feel are most appropriate for their physical condition, goals and lifestyle. The programme should therefore be presented in a positive way where the patient feels they have a choice, and they feel empowered and motivated.

Conclusion

PSH may well be inevitable for many patients and the reality of living with a stoma and PSH can be difficult to cope with. Once diagnosed with PSH, many patients become less active, fearful and have reduced QoL.

An appropriate therapeutic exercise programme can be a powerful tool in rebuilding self-confidence and physical strength and should be encouraged and introduced to all patients. Appropriate core abdominal exercises – such as in the me+recovery programme – are safe for stoma patients to potentially reduce their risk of PSH and also for those who have already developed a PSH.

The stoma care nurse specialist is in a unique position to have a significant influence on how a patient adapts and copes with life with a stoma and/or a PSH. Using a person-centred approach and strength-based language, along with providing evidence-based advice and introduction of a therapeutic exercise programme, it is possible to reduce fear, increase confidence, and improve QoL for the stoma patient.

Conflict of Interest

The author is an employee of ConvaTec UK.

Funding

This article was funded by ConvaTec UK.

造口旁疝:改善生活质量、恢复信心和减少恐惧。造口专科护士角色的重要性

Sarah Russell

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.4.36-39

摘要

本文概述了2018年英国的一项造口患者调查中有关造口旁疝(PSH)的定性评论。本文还考虑了造口专科护士的角色在改善造口和/或PSH患者的生活质量(QoL)、减少恐惧和恢复信心方面的重要性。

引言

造口旁疝(PSH)是一种常见的造口术后并发症。真实的发病率尚未知,但是术后12个月时的患病率估计约为25–30%1,术后2年为50%或更高,而且许多临床医生认为随着时间的推移,PSH可能是不可避免的1-5。总体而言,仍缺乏关于PSH历史、风险因素和原因的优质研究,而且缺乏关于预防和治疗的共识3,不过涉及这一问题的临床试验(特别是CIPHER研究)正在进行中。

尽管尚无定论,但是一般认为发生PSH的关键风险因素包括性别为男性、年龄(超过60岁)、手术并发症/技术、末端结肠造口术、既往类固醇/化疗治疗、肥胖症(BMI>25)、吸烟、COPD/呼吸系统疾病和腹肌无力6-10。先前的研究表明,造口形成后,存在身体活动不足的趋势,对PSH的恐惧是积极生活的一个主要妨碍因素11。其他研究(由本文作者所著)表明,40%的患者报告在造口术后身体活动减少,但在诊断为PSH的患者中,这一比例显著上升至53% 12,13。

根据这些研究中患者的评论得出结论,“导致疝”恶化或缺乏与PSH共处相关的建议是生活质量(QoL)下降和身体活动不足的重要因素13。患者通常(通过以下评论证实)报告称,他们感到恐惧,不确定自己可以安全地进行哪些活动来降低患PSH的风险,并且不清楚在诊断出PSH时该做什么,因此产生了恐惧感和脆弱感。患者经常报告称,传闻不能做腹部运动,要谨慎运动和提举,要“小心”患PSH,这进一步加剧问题,并造成恐惧、回避身体活动和QoL下降的循环。

定性患者评论

在2018年,从英国的1,500名造口患者中收集调查回答。以下评论直接取自调查评论:

我害怕做太多的运动,这会使我的造口/疝酸痛,而且我不知道我可以做多大量的运动。

就我个人而言,我希望能获得关于疝的建议,以及关于从一开始就如何预防的建议,毕竟,预防胜于治疗。

我想知道存在疝的患者该做和不该做的运动有哪些。

我认为需要这方面的更多信息。包括腹部运动,以及如何安全地从事更剧烈的活动。

我听到最多的是,6个星期内不要提举重物,重量不能超过一个装满水的水壶。但是6个星期后呢?谁知道……术后护理应该包括找有造口知识和经验的理疗师就诊。

我害怕做运动,因为我不想体内出现疝。

最好向患者提供建议,说明应该做哪些或不应该做哪些运动,以便改善健康/力气或避免受伤/疝。

很多时候,在疝修补术后都没有告知患者该做什么和不该做什么,导致疝复发,术后身体康复应该是标准操作。

我想知道如何在没有出现严重疝的风险的情况下,增强我的腹肌。

我很生气,在我坚持询问之前,对于如何预防疝或尽可能减少出现疝的风险,什么信息也没告诉我。我通过参考互联网上的信息才终于了解到可以帮助自己的一些操作。但是,得到信息的时间太晚,无法解决我一直在扩大的疝。

我担心出现疝,很难知道什么情况下属于运动过度

这些评论代表了最常见的回答,表明恐惧和错误信息是共同主题,并且表明了对造口术后提供关于PSH和安全运动/康复的更好建议的明显诉求。这些评论,以及其他研究的研究结果11,显示造口患者有“回避恐惧”14的明显趋势,尤其是那些诊断为PSH的患者。

造口专科护士如何提供帮助?

造口专科护士处于能够进行再教育和提供支持的独特位置,使患者减少焦虑和恐惧感,最终增强信心、提高活动水平和改善QoL15。在本部分中,我们建议可以通过以下三种方式来实现这一点:

• 采用以人为本的方法。

• 使用正能量的语言。

• 实施适当的治疗性康复运动计划

根据英国造口护理护士协会(ASCN)发布的临床指南6,提供关于PSH(风险降低以及PSH管理)的明确的循证建议是毫无问题的。可以与患者小心地讨论ASCN指南中所述的可改变风险因素,尤其是减重和戒烟。这一建议还应包括介绍或指示术前或术后的适当治疗性康复计划。可以采取小册子、在线视频、适当的癌症或造口康复课程或一对一指导的形式。造口护士应确保提供教育资料,如慈善机构(回肠造口术协会和麦克米伦癌症支持组织)和造口袋制造商产出的资料,以及ASCN临床指南中强调的资料。理想情况下,他们还应该能够向患者演示适合的运动。然而,提供这些建议和信息的方式以及所使用的语言可能会给患者对PSH的感受带来深远的影响16。重要的是,不要让患者感到内疚或羞耻,也不要让他们感到是自己因某种原因导致自己出现了疝。

以人为本的方法

以人为本的方法采取整体视角看待患者,不仅考虑患者的医疗状况,还考虑患者的心理和社会需求,以及个人喜好、爱好和兴趣17,18。这种方法在考虑整个人时不放过任何医疗状况或残疾状况。这在与患者讨论PSH时非常重要。请考虑无意中提供的谨慎建议可能对患者造成的影响。

以一个病例研究为例,患者A(一位75岁的男性,行结肠造口术)被告知不要打高尔夫,以防造成PSH恶化。诊所快速给出了这一建议,几乎是作为漫不经心的意见,在给出建议时带着善意和真诚,但是产生了毁灭性的影响。高尔夫是患者A的生命。他是高尔夫俱乐部的主席,打了一辈子高尔夫。他甚至选择背靠着高尔夫球场买房子。这是他的社交生活和身心健康的关键生命线。被告知从此不能再打高尔夫让他非常困惑,对他的身心健康造成了损害。

相反,以人为本的方法意味着提供一些改变,使他能够更安全地打高尔夫,例如做腹部核心运动,展示挥杆时的正确技术,在球场上使用高尔夫球车,如果觉得有帮助就穿上支撑服。

正能量的语言

正能量的语言强调人们的优势、能力和机会,而不是他们面临的挑战、存在的疾病或觉察的缺陷16。这样的语言侧重于提供建议,告诉患者可以做的事情,而不是他们应该避免的事情(图1)。然而,在试图提供关爱、谨慎的建议时,很容易无意中使用消极的语言。

图1.正能量语言的一些示例(作者创建)

当与患者讨论PSH时,使用“正能量”的语言意味着使用积极的语言,并侧重于以患者为本做出改变,强调他们能做的事情,而不是他们不能做的事情。这会给患者赋能,使患者有信心自我管理自己的PSH,增强他们的能力并减少他们的恐惧。

这一简单的改变可以从根本上改变患者适应有造口或PSH的生活方式,也可能是他们走出“回避恐惧”的循环、减少恐惧和改善QoL的钥匙。

治疗性康复运动计划

最后,实施适当的治疗性运动康复计划是帮助患者恢复对自己身体的信心、减少恐惧和改善QoL的有力工具19-21。

该建议符合英国ASCN临床指南6。这些指南指出,适当的 “核心”运动快则可以在术后3-4天开始。如有可能,“核心”运动也可以在术前作为一种“预康复”来实施。英国ASCN临床指南中说明了适合的运动。其他适合的计划和运动可以从医院理疗师、造口慈善机构或造口袋制造商处获得。康维德22的me+recovery计划是一项三阶段计划,获得了ASCN、英国皇家护理学院和大不列颠及爱尔兰肛肠协会的批准。它提供了一系列适合任何患者在手术恢复的任何阶段进行的运动。

通过这些简单的运动计划,患者可以恢复正常的活动模式,改善核心和盆底功能及控制,学会更加自信地活动20。腹部核心运动可以给人一种控制感和稳定感,可能是与造口和/或PSH共处的关键。适合造口患者进行的腹部核心运动包括简单地收紧深层核心肌肉和盆底肌,以及仰卧时进行骨盆倾斜和膝滚翻等运动。这些运动以临床普拉提为基础,类似于产后运动。其目标是获得深层核心肌肉和骨盆的控制、连接和功能。图2显示了这个基础阶段对所有人的重要性,包括恢复功能、信心、活动和身体健康。

图2.康维德公司22me+recovery计划的基础阶段

一个适合的治疗性运动康复计划应该包括一系列可以在术后立即进行的康复运动。随着患者的病情好转和状态恢复,这个计划也应该有进阶的选项。这也有助于激励和参与。这个计划还应该为希望在椅子上、站立时或在床上运动的患者提供广泛的改良和改变19-21。

根据以人为本的护理,每位患者也应有机会选择自己认为最适合其身体状况、目标和生活方式的运动。因此,该计划应以积极的方式呈现,让患者感到自己有选择的余地,并感到有力量和动力。

结论

对于许多患者而言,PSH可能是不可避免的,而且可能也难以应对与造口和PSH共处的现实。一旦诊断为PSH,许多患者的活动量会减少,感到恐惧,生活质量下降。

适当的治疗性运动计划可以成为重建自信和体力的强大工具,应予以鼓励并将其介绍给所有患者。适当的腹部核心运动(例如在me+recovery计划中)可以安全地使造口患者有可能降低出现PSH的风险,对于已经出现PSH的患者也是安全的。

造口护理专科护士处于独特的位置,对患者如何适应和应对与造口和/或PSH共处的生活有重要影响。采用以人为本的方法、正能量的语言以及提供循证建议和引入治疗性运动计划,有可能减少造口患者的恐惧,增强其信心并改善其QoL。

利益冲突

作者是ConvaTec UK的雇员。

资助

本文章由ConvaTec UK资助。

Author(s)

Sarah Russell

MSc

Clinical Exercise Specialist, UK

Email sarah@sarah-russell.co.uk

References

- Anderson RM, Klausen TW, Danielsen AK, Vinther A, Gögenur I, Thomsen T. Incidence and risk factors for parastomal bulging in patients with ileostomy or colostomy: a register-based study using data from the Danish Stoma Database Capital Region. Colorectal Dis 2018;20(4):331–340.

- Antoniou SA, Agresta F, Garcia-Alamino JM, Berger D, Berrevoet F, Brandsma HT, et al. European Hernia Society guidelines on prevention and treatment of parastomal hernias. Hernia 2017;22(1):1–16.

- ACPGBI Parastomal Hernia Group. Prevention and treatment of parastomal hernia: a position statement on behalf of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. Colorectal Dis 2018;20(52):5–19.

- Randall J, Lord B, Fulham J, Soin B. Parastomal hernias as the predominant stoma complication after laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2012;22(5):420–423.

- Sohn YJ, Moon SM, Shin US, Jee SH. Incidence and risk factors of parastomal hernia. J Korean Soc Coloproctol 2012;28(5):241–246.

- Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK. Stoma Care National Clinical Guidelines UK 2016. Available from: sath.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Stoma-Care-Guidelines.pdf

- Kojima K, Nakamura T, Sato T, Matsubara Y, Naito M, Yamashita K , et al. Risk factors for parastomal hernia after abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer. Asian J Endosc Surg 2017;10(3):276–281.

- Thompson MJ, Trainor B. Incidence of parastomal hernia before and after a prevention programme. Gastrointest Nurs 2005;3(2):23–27.

- North J. Early intervention, parastomal hernia and quality of life: a research study. Br J Nurs 2014;23(5):S14–S18.

- Thompson MJ. Parastomal hernia: incidence, prevention and treatment strategies. Br J Nurs 2008;17(2):S16, S18–20.

- Beeken RJ, Haviland JS, Taylor C, Campbell A, Fisher A, Grimmett C, et al. Smoking, alcohol consumption, diet and physical activity of people with a stoma, stoma-related concerns, and desire for lifestyle advice: a United Kingdom survey. BMC Public Health 2019 [cited 2020 Jul 31]. Available from: bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-019-6913-z

- Russell S. Physical activity and exercise after stoma surgery: overcoming the barriers. Br J Nurs 2017;26(5):S20–S26.

- Russell S. Parastomal hernia and physical activity. Are patients getting the right advice? Br J Nurs 2017;26(17):S12–S18.

- Leeuw M, Goossens M, Linton SJ, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen J. The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence. J Behav Med 2007;30(1):77–94.

- Bland C, Young K. Nurse activity to prevent and support patients with a parastomal hernia. Gastrointest Nurs 2015;13(10):16–24.

- Resources for Integrated Care. Using person-centred language; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 31]. Available from: resourcesforintegratedcare.com/sites/default/files/Using_Person_Centered_Language_Tip_Sheet.pdf

- Royal College of General Practitioners. About person-centred care; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 31]. Available from: rcgp.org.uk/clinical-and-research/our-programmes/about-person-centred-care.aspx

- Social Care Institute for Excellence. Person-centred care; n.d. [cited 2020 Jul 31]. Available from: scie.org.uk/prevention/choice/person-centred-care

- Hubbard G, Beeken RJ, Taylor C, Watson AJM, Munro J, Goodman W. A physical activity intervention to improve the quality of life of patients with a stoma: a feasibility study protocol. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2019;5(1):78.

- Bullo V, Bergamin M, Gobbo S, Sieverdes JC, Zaccaria M, Neunhaeuserer D, et al. The effects of Pilates exercise training on physical fitness and wellbeing in the elderly: a systematic review for future exercise prescription. Prev Med 2015;75:1–11.

- Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, May AM, Schwartz AL, Courneya KS, et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019;51(11):2375–2390.

- ConvaTec. The me+ recovery programme; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 31]. Available from: meplus.convatec.co.uk/