Volume 40 Number 4

A quality improvement project comparing two treatments for deep-tissue pressure injuries to feet and lower legs of long-term care residents

Autumn Henson and Laurie Kennedy-Malone

Keywords pressure injury, deep-tissue pressure injury, lower-extremity injury, long-term care, offloading, polymeric membrane dressings, skin barrier film

For referencing Henson A and Kennedy-Malone L. A quality improvement project comparing two treatments for deep-tissue pressure injuries to feet and lower legs of long-term care residents. WCET® Journal 2020;40(4):30-35

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.4.30-35

Abstract

Objective To retrospectively examine clinical outcomes from a feasibility study that compared two treatment options for deep-tissue pressure injuries (DTPIs), including the clinical indicators increasing the risk of deteriorating DTPIs among long-term care residents.

Methods A retrospective chart audit of 40 DTPIs from 33 long-term care residents in two long-term care facilities were conducted to compare 1: polymeric membrane dressings (PMDs) with offloading; and 2: a skin barrier film with offloading.

Results Of the 13 DTPIs treated with PMDs, only 23% deteriorated to a stage 3 or 4 pressure injury (PI), whereas of the 27 DTPIs treated with skin barrier film, 41% deteriorated to a stage 3 or 4 PI. The clinical factors found to increase the risk of developing and deteriorating DTPIs included weight loss, hypoalbuminemia, debility, dementia, coronary artery disease, and cerebrovascular disease.

Conclusions The PMD group’s DTPIs evolved into fewer open PIs despite having higher percentages of clinical indicators for DTPIs. The project findings support the use of PMD dressings for DTPIs; however, more robust research is warranted.

Introduction

A pressure injury (PI) is pressure-related damage to a local area of skin and the underlying tissue, generally over a bony prominence.1 These injuries present a significant challenge for the staff of long-term care facilities (LTCFs) and affect their residents’ quality of life, escalating healthcare costs, readmissions, risk of infection, pain, depression, and death.2,3 Deep-tissue pressure injuries (DTPIs) are PIs that occur under intact skin, which are thought to first develop in the deep tissues of the body and then appear on the skin surface4 as nonblanchable red, purple, or maroon discoloration or a blood-filled blister.1

Despite current treatment, these injuries often rapidly become open wounds.4 Typically, DTPI treatment aims to prevent further damage and avoid devolution to stage 3 or 4 PI.4 However, there is limited research on DTPI treatment, so this quality improvement project was implemented to retrospectively analyse the findings of a feasibility study that compared a drug-free polymeric membrane dressing (PMD) with the use of a skin barrier film among residents in two LTCFs with DTPIs on their feet and lower legs. The PMD is a foam dressing designed to reduce inflammatory factors and edema related to skin damage while requiring infrequent dressing changes.5 The PMD was chosen because of its easy accessibility and supply in the study LTCFs. Skin barrier films come in multiple forms and comprise a transparent coating to protect skin from trauma and moisture.6 The previous DTPI treatments used in the two facilities were a skin barrier film and offloading; despite using the skin barrier film twice a day, the facilities continued to see deteriorating DTPIs, prompting the feasibility study.

Along with the current treatment concerns regarding DTPIs, research is ongoing to ascertain whether there are clinical indicators that influence the evolution of DTPIs into open wounds. In LTCFs, most residents have multiple comorbidities that influence PI risk, including DTPIs.7 Further studies are needed to conclusively establish the clinical indicators that potentially contribute to DTPIs so they can be mitigated.

Background and Clinical Problem

The prevalence of DTPIs has increased threefold since 2006, presumably because of the classification of DTPIs, which were defined in 2007. This increased the awareness of DTPIs.4 Changes in regulations and improvements in prevention and treatment have not reduced their incidence, and the number and cost of all PIs continue to increase.8 In addition to causing pain and suffering for LTCF residents, DTPIs cost LTCFs as much as $3.3 billion annually.9

The most common location for a DTPI is on the heel. Heels are mostly bony prominences covered by a thin layer of skin with little padding or protection from pressure.10,11 Further, other medical conditions, such as respiratory and/or cardiovascular issues, increase the time residents spend supine, and they often require the head of the bed to be elevated, which places additional pressure on the feet and legs.10-13 The same pressure mechanisms damage the soft tissues of the lateral areas of the foot and toes; because of chronic lateral positioning, these areas often experience sustained, unrelieved pressure.11

Shearing is a common risk factor to consider in the evolution of DTPIs.13,14 The layers of skin stretched against a surface with friction and pressure result in damage on the surface and deeper internal tissues.14 Shearing risk includes passive repositioning of residents, elevating the head of the bed, and involuntary active movements involving spasms or tremors from medical conditions, which increase the constant positioning/pressure of the feet against the mattress.14 The risk of pressure and shearing consequently increases the risk of deterioration of DTPIs of the feet and lower legs.4,14,15

In addition to the lack of standard treatment for DTPIs, there is concern about whether DTPI deterioration could be affected by certain clinical indicators. In many LTCFs, a large percentage of residents with limited mobility and debility have a higher risk of developing a PI. As residents age, the number of medical conditions they encounter increases.7 Published studies show that medical conditions such as anemia, diabetes mellitus, fecal or urinary incontinence, vascular disease, or malnutrition increase the risk of developing PIs and (more recently) DTPIs.3,4,7,16 Of these risk factors, anemia has been most commonly associated with an increased risk of DTPIs.3,4 A review by Gefen et al13 notes that variables such as fever, uncontrolled cardiovascular disease, or respiratory acidosis could also increase the risk of DTPIs. Accordingly, this project not only compared two different treatment options for DTPIs, but also considered the resident’s clinical indicators and their potential influence on DTPI deterioration.

The treatment of DTPIs generally falls into one of two categories: offloading and application. In a Cochrane systematic review, McGinnis and Stubbs17 studied heel pressure-reducing devices for offloading in the treatment of heel ulcers. According to their results, there is no single device available that meets all of the criteria for comfort in the prevention and treatment of heel ulcers by removing pressure with offloading. There also is a need for further research into relieving heel pressure and treating PIs with offloading.17 Van Leen et al18 reviewed pressure-reducing techniques for PI treatment in a longitudinal study in a Dutch LTCF. Offloading the feet and lower legs led to a statistically significant decrease in PIs from 16.6% to 5.5%, with the most benefit for patients with medium to high risk of PIs. Over the years of the study, 57.8% of the patients at medium to high risk of PI with documented offloading of feet and legs (as well as educational intervention) were less likely to develop a PI.18

The other category of treatment is the application of dressings. A randomised controlled study by Sullivan19 evaluated the treatment of DTPIs with dressings and demonstrated that 74% of DTPIs decreased in size or resolved with the use of a self-adherent, multilayered, silicone-based border foam dressing. Of the 128 DTPIs in this study, only one opened to deeper tissue, and the other injuries either did not open or opened to the dermis with a mean healing time of 17.8 days. Essentially, the multilayered foam dressings decreased deterioration and improved resolution time.19

Campbell et al16 evaluated the use of padded-heel dressings to treat heel wounds. The treatment group showed 100% improvement among the 20 participants, whereas only 13 of 20 wounds in the control group closed. The study also demonstrated that the treatment group required less time and financial expense to heal.16

The National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel recommends the use of offloading and preventive dressings on residents who are at high risk of developing heel ulcers.20 Levy et al15 observed that prophylactic dressings applied to the heels decreased the risk of DTPIs by reducing stress and shear. Ultimately, the use of dressings to protect skin and offload pressure and shearing is widely recommended, although comparison studies are limited and warranted.

Methods

The purpose of this project was to retrospectively compare, analyse, and evaluate the documented deterioration of DTPIs to open PI among residents using two different treatments. The secondary purpose was to determine the prevalence of clinical indicators known to contribute to the development of DTPIs in the PMD group versus the skin barrier film group.

This project sought to answer the following research questions:

(1) Do PMDs and foot offloading reduce deterioration of DTPIs for residents 55 years or older better than skin barrier film with offloading?

(2) What was the prevalence of various clinical indicators among residents who developed a DTPI on their foot and/or lower extremity, and would a change in treatment have an impact on the evolution of the DTPI?

Study Initiation and Ethics

An analysis of administrative data collected by the quality assurance and performance improvement team from two LTCFs during 2014 and 2015 showed that 36% of DTPIs evolved into open stage 3 or 4 PIs when treated with offloading and the twice-daily application of a skin barrier film. This finding was the catalyst to perform a feasibility study comparing the skin barrier film with PMDs for DTPIs that developed between October 2015 and May 2017 in the two facilities. The PMD was chosen because it was new to the facilities’ formulary lists, was easily accessible, and had evidence of benefit for other types of wounds.

This retrospective comparative analysis project conducted in fall 2017 examined the outcomes for the 33 residents with a total of 40 DTPIs included in the feasibility study. Researchers conducted a systematic chart audit comparing the treatments of PMD or skin barrier film for the sample of residents with DTPIs and based on the type of treatment used from October 2015 to May 2017. Charts were included in the project if the resident had a DTPI to the feet and lower legs, were at least 55 years old, and were treated with either PMDs or skin barrier film with offloading.

During the feasibility study, each resident in each group had an ongoing order for offloading to the DTPI. The residents chosen for the PMD group either provided consent for the new treatment or permission was granted by the resident’s responsible party. Treatment with PMD included cutting the PMD to a size slightly larger than the DTPI as well as the application of a transparent medical dressing to cover the PMD once applied. The dressing was changed twice a week. The skin barrier film wipes were applied twice daily, and skin was allowed to dry following the application. The university’s institutional review board deemed the current project exempt. The LTCFs’ corporate holding company, administrative leadership teams, and medical providers’ board members approved the project.

Setting and Participants

The two participating LTCFs are Medicare and Medicaid approved, with private pay residents and a bed capacity of approximately 90 and 110 residents, respectively. They are in the southeastern US. These facilities provide short- and long-term care services that include rehabilitation and complex medical care for residents with reduced physical and mental functioning and multiple comorbidities such as PIs and DTPIs.

Data were extracted, deidentified, audited for the inclusion criteria, and given to the principal investigator by chart auditors. The sample was developed based on resident treatment, with the skin barrier group comprising 23 residents with 27 DTPIs, and the PMD group, 10 residents with 13 DTPIs.

Data Collection and Outcome Measures

Trained medical records experts from each facility extracted previously recorded data from the electronic medical record program called the Electronic Charting System. The data collectors were trained by the principal investigator as to what specific data to extrapolate and code for data entry. The data collectors received standardised training from the investigator to ensure the accuracy of the data collection and the systematic retrieval of the information. Data were retrieved from the electronic medical record on each resident for every DTPI documented. The generated data reports were deidentified and transferred into a private, secure PDF file by the data collectors. The PDF file was then coded and converted into a Microsoft Excel form and organised into a secure database and stored in a password-protected file for retrieval by the principal investigator for analysis.

Data extracted from the medical charts consisted of both demographics and clinical indicators. Demographics included resident age, sex, and ethnicity. The clinical indicators included laboratory test results (anemia and hypoalbuminemia screening), chronic diseases/comorbidities, health history, functional status, and Braden Scale scores.

The Braden Scale is an assessment tool used to determine the risk of developing a PI. The Braden Scale scoring ranges from less than 9 to 32. The lower the Braden Scale score, the higher the risk of developing a PI.21 Residents with albumin levels less than 3.2 g/dL (reference range, 3.5-5.2 g/dL) demonstrated hypoalbuminemia, which may reflect a decrease in nutrition status in certain patient populations.7 Anemia was identified as a hemoglobin level below the reference range of 12 to 15 g/dL. Chronic diseases and comorbidities were identified with a diagnosis or International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision code and included peripheral vascular disease, dementia, coronary artery disease, and/or cerebrovascular disease.

Further data included history of previous PI and recent orthopedic history such as any fracture or surgery to the lower half of the body. In addition, information on the resident’s level of activities of daily living support and any history of chronic involuntary movements was retrieved. Weight changes were also noted, that is, whether each resident had weight gain or weight loss prior to the identification of the DTPI(s).

Any diagnosis of peripheral vascular disease noted in the residents’ chart was captured in the data collection. Because no residents had a documented ankle-brachial pressure index to confirm diagnosis, residents with peripheral artery disease were excluded. In addition, residents with previously diagnosed diabetic or arterial ulcers were excluded.

The outcome variables included DTPI deterioration and PI stage at the time of opening, if applicable.

Statistical Analysis

The Microsoft Excel Descriptive Statistics Tool (Redmond, Washington) was used to analyse the data from the two groups. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample. Independent χ2 tests were used to compare each group with the clinical outcomes of opening or not opening. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

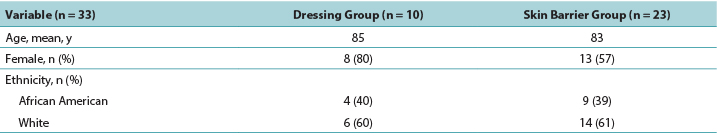

The majority of participants were White women with a mean age of 84 years. The PMD group was slightly older than the skin barrier film group (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics of Residents with deep-tissue pressure injury by treatment group

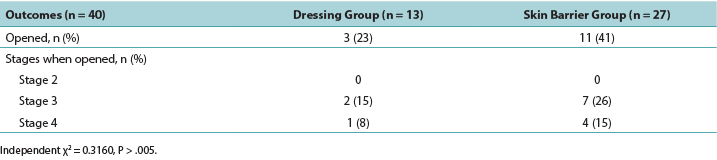

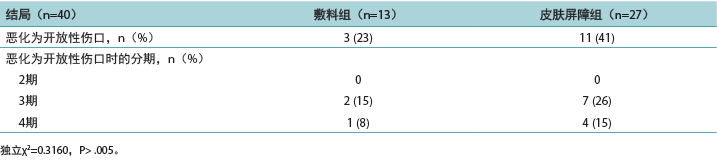

A simple statistical analysis compared the primary outcome measure between groups; according to the independent χ2 test, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .3160). In the PMD group, 23% of the DTPIs deteriorated to an open PI, whereas 41% of the DTPIs in skin barrier film group opened to a stage 3 or 4 PI. Of the DTPIs that opened, only two of the PMD group wounds opened to a stage 3 PI, and only one opened to a stage 4 PI. Of the DTPIs in the skin barrier film group, seven DTPIs opened to a stage 3 PI, and four opened to a stage 4 PI (Table 2).

Table 2. Wound outcomes

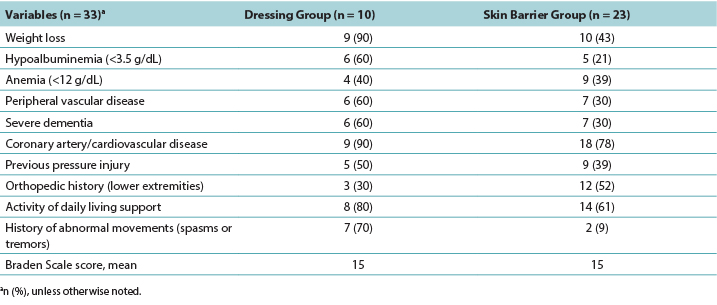

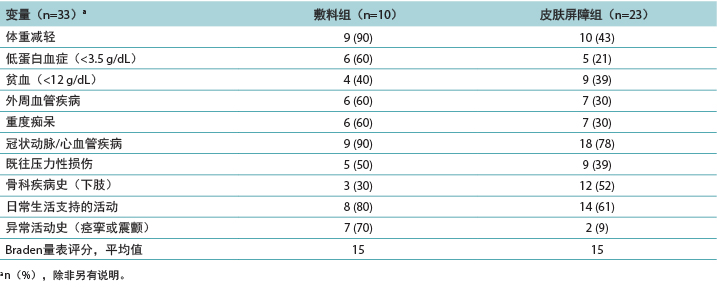

Descriptive data were generated for the clinical indicators that increased the risk of developing a DTPI (Table 3). The PMD group had more residents with known clinical indicators for DTPIs. The number of residents needing two people to assist in their activities of daily living was a significant factor, representing 80% of the PMD group and 61% of the skin barrier film group. Residents in both groups had an average Braden Scale score of 15, indicating at least a moderate risk of developing a DTPI. Weight loss and lower albumin scores were implicated, especially for the PMD group, with 90% seeing weight loss and 60% hypoalbuminemia. The residents with severe dementia (PMD, 60%; skin barrier film, 30%) also demonstrated a higher risk of DTPI, as well as residents with a diagnosis of coronary artery disease or cerebrovascular disease (PMD, 90%; skin barrier film, 78%). To investigate shearing, data were collected on residents who had abnormal lower extremity movement such as tremors or spasms. In the PMD group, this clinical indicator may have contributed to the development of DTPIs in 70% of the residents. Interestingly, anemia was an indicator for DTPIs (PMD, 40%; skin barrier film, 39%), although not to the significance level noted in other studies.

Table 3. Clinical Indicators of Residents with deep-tissue pressure injury by treatment group

Discussion

This retrospective project concluded that skin barrier film and offloading did not prevent the deterioration of DTPIs. Only three DTPIs evolved into an open wound in the PMD group, compared with 11 of the DTPIs in the skin barrier film group. Although this project did not have the statistical power to demonstrate significance, results indicate a possible benefit to changing the current treatment from the skin barrier film with offloading to PMDs with offloading.

This project found a higher risk of deteriorating DTPIs in the residents with more clinical indicators, in accordance with previous studies.7,16 Many of the LTCF residents’ medical conditions continue to be significant indicators, including weight loss, lower albumin levels, abnormal movements such as spasms or tremors, coronary artery disease, and cerebrovascular disease.4,16 Indicators such as anemia, previous orthopedic surgeries or fractures, peripheral vascular disease, and severe dementia were associated with a moderate risk of deteriorating DTPIs; previous studies found these were high-risk indicators.4,7,16 Interestingly, the PMD group had more clinical indicators for DTPI deterioration on average and yet had better outcomes. This demonstrates that treatment and management can outweigh the effects of clinical indicators for DPTI progression.

Limitations

The convenience sample size was small because of the total number of residents with diagnosed DTPI during the feasibility study period. Although all of the data collectors were trained by one person at the same time, there was no interrater reliability testing. Further, the diagnosis of DTPI was extracted by the data collectors based on provider diagnosis, because an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision code for DTPI was not established until 2019. Finally, it is important to note that PMDs may not be available in all healthcare settings, limiting the generalisability of the findings.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Offloading and repositioning of LTCF residents continue to be the recommended treatment for DTPIs. However, complications related to deteriorating DTPIs affect LTCF residents and strain the healthcare system. This project compares two different treatments for DTPIs, while considering the clinical indicators that may increase the risk of DTPI deterioration. Although further evidence is needed to address the cost-effectiveness of these treatments, PMD likely reduced the deterioration of DTPIs. Therefore, PMDs may be attractive to facilities striving to deliver efficient healthcare for their residents, especially those with high-risk residents.

Conclusions

Although prevention is crucial, once a DTPI has developed, having a fast and reliable treatment option to prevent further deterioration is of the utmost importance. By addressing DTPIs with offloading and screening for clinical indicators of deterioration, along with a preventive treatment such as PMD, the trajectory for these injuries could be vastly improved.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

一项比较长期护理住院患者足部和小腿深部组织压力性损伤的两种治疗方法的质量改进项目

Autumn Henson and Laurie Kennedy-Malone

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.4.30-35

摘要

目的 回顾性分析一项可行性研究的临床结局,包括长期护理住院患者DTPI恶化风险增加的临床指标,其中该研究比较了深部组织压力性损伤(DTPI)的两种治疗方案。

方法 对两个长期护理机构中33例长期护理住院患者的40例DTPI进行回顾性病历审查,以比较1:聚合物膜敷料(PMD)与减压;和2:皮肤屏障膜与减压的效果。

结果 13例接受PMD治疗的DTPI中,仅23%恶化为3期或4期压力性损伤(PI),而27例接受皮肤屏障膜治疗的DTPI中,41%恶化为3期或4期PI。发现以下临床因素会增加发生DTPI和DTPI恶化的风险:体重减轻、低蛋白血症、虚弱、痴呆、冠状动脉疾病和脑血管疾病。

结论 尽管PMD组拥有DTPI临床指标的百分比更高,但该组的DTPI发展为开放性PI的例数较少。项目的结果支持使用PMD敷料治疗DTPI;但是,需要进行更可靠的研究。

引言

压力性损伤(PI)是通常在骨突起部位上对局部皮肤区域和皮下组织造成的压力相关性损伤。1 这些损伤给长期护理机构(LTCF)的工作人员带来重大挑战,影响其住院患者的生活质量,包括增加医疗费用、再入院、感染风险、疼痛、抑郁和死亡。2,3 深部组织压力性损伤(DTPI)是发生在完整皮肤下的PI,研究认为它首先发生在身体的深部组织中,然后在皮肤表面4表现为不褪色的红色、紫色或褐红色变色区域或充血的水泡1。

尽管目前会对其进行治疗,但这些损伤通常会迅速变成开放性伤口。4 一般情况下,DTPI治疗旨在预防发生进一步损伤并避免恶化为3期或4期PI。4 但是,关于DTPI治疗的研究有限,所以实施此质量改进项目,以便回顾性分析一项可行性研究的研究结果,该研究比较了无药物聚合物膜敷料(PMD)和皮肤屏障膜在两个LTCF中的住院患者中的应用,这些患者的足部和小腿发生DTPI。PMD为泡沫敷料,设计用来减少炎性因子和与皮肤损伤相关的水肿,而且不需要频繁更换敷料。5 之所以选择PMD,是因为它在研究LTCF中容易获得和供应。皮肤屏障膜以多种形式提供,包含一种透明涂层,避免皮肤遭受创伤和接触水分。6 先前在两个机构中使用的DTPI治疗方法为皮肤屏障膜和减压;尽管皮肤屏障膜每天使用两次,但是机构随后发现DTPI恶化,因此导致需要进行可行性研究。

基于对当前DTPI治疗方法的担忧,正在进行研究,以确定是否存在影响DTPI发展为开放性伤口的临床指标。在LTCF中,大多数住院患者患有影响PI风险(包括DTPI)的多重合并症。7 还需要进一步的研究来最终确定可能导致DTPI的临床指标,从而缓解这些临床指标的影响。

背景和临床问题

自2006年以来,DTPI的患病率增长了三倍,这可能是由于在2007年定义了DTPI的分类。对该疾病的分类提高了人们对DTPI的意识。4 法规的变化以及预防和治疗的改善并未降低其发病率,所有PI的数量和费用仍在不断增加。8 除了给LTCF住院患者带来疼痛和痛苦之外,LTCF针对DTPI每年的费用高达33亿美元。9

DTPI最常出现在足跟处。足跟主要是由一层薄薄的皮肤覆盖的骨突起部位,很少有衬垫或压力保护。10,11 此外,呼吸和/或心血管问题等其他医疗状况,增加了住院患者的仰卧时间,而且他们经常需要抬高床头,这给足部和腿部增加了额外的压力。10-13 此类压力机制会损伤足部和脚趾外侧区域的软组织;由于长期处于侧卧位,这些区域经常承受持续、未减轻的压力。11

剪切是在DTPI发展过程中需要考虑的一个常见风险因素。13,14 皮肤层受到表面摩擦力和压力的拉扯,导致表面和更深层内部组织损伤。14 剪切风险包括被动调整住院患者的体位、抬高床头和非自愿主动活动,涉及医疗状况引起的痉挛或震颤,这会增加足部持续紧靠床垫的体位状态/足部压力。14 因此,压力和剪切风险增加了足部和小腿DTPI恶化的风险。4,14,15

除了缺乏标准的DTPI治疗方法外,人们还担心DTPI恶化是否可能受到某些临床指标的影响。在许多LTCF中,大量活动受限且虚弱的住院患者发生PI的风险更高。随着住院患者年龄的增长,他们遇到的医疗状况越来越多。7 已发表的研究表明,贫血、糖尿病、大小便失禁、血管疾病或营养不良等疾病会增加发生PI和(更近期)DTPI的风险。3,4,7,16 在这些风险因素中,贫血最常与DTPI的风险增加相关。3,4 Gefen等人13的一项综述指出,发热、未控制的心血管疾病或呼吸性酸中毒等变量也可能增加DTPI的风险。因此,本项目不仅比较了两种不同的DTPI治疗方案,还考虑了住院患者的临床指标及其对DTPI恶化的潜在影响。

DTPI治疗一般分为两类:减压和敷用敷料。在一份Cochrane系统评价中,McGinnis和Stubbs17研究了对足跟溃疡进行减压治疗的足跟减压装置的效果。根据他们的结果,没有一种器械可在通过使用减压装置消除压力来预防和治疗足跟溃疡的过程中,满足所有舒适度标准。还需要进一步研究如何缓解足跟压力和通过减压治疗PI。17 Van Leen等人18在一个荷兰LTCF进行的一项纵向研究中回顾了用于PI治疗的减压技术。足部和小腿减压导致PI发病率从16.6%下降到5.5%,这具有统计学意义,中高PI风险的患者具有最大受益。在多年的研究中,中高PI风险的患者中,57.8%记录有足部和腿部减压(以及教育性干预),他们发生PI的可能性较低。18

另一类治疗为敷用敷料。Sullivan19的一项随机对照研究评价了使用敷料治疗DTPI的效果,结果表明,在使用一种自粘性、多层、硅酮有边型泡沫敷料后,74%的DTPI病变尺寸缩小或消退。在该研究的128例DTPI中,仅一例为更深部组织开放性损伤,其他例损伤为非开放性损伤或真皮层开放性损伤,平均愈合时间为17.8天。本质上,多层泡沫敷料减少了恶化并加快了消退时间。19

Campbell等人16评价了使用足跟衬垫敷料治疗足跟伤口的效果。治疗组的20名参与者显示了100%的改善,而对照组的20例伤口中,仅13例出现闭合。该研究还表明,治疗组伤口愈合所需的时间和资金花费更少。16

美国压力性损伤咨询委员会建议对高足跟溃疡患病风险的住院患者使用减压和预防性敷料。20 Levy等人15观察到敷在足跟上的预防性敷料通过减少压力和剪切力降低了DTPI的风险。最终,广泛建议使用敷料来保护皮肤、减轻压力和减少剪切力,不过比较研究尚且有限,有必要进行此类研究。

方法

本项目的目的是回顾性比较、分析和评价记录在案的、在住院患者中使用两种不同治疗方法时DTPI恶化为开放性PI的情况。次要目的是确定在PMD组和皮肤屏障膜组之间,已知会导致发生DTPI的临床指标的患病率。

本项目试图回答以下研究问题:

(1) 对于55岁或55岁以上的住院患者,PMD和足部减压减少DTPI恶化的效果是否优于皮肤屏障膜与减压?

(2) 在发生足部和/或下肢DTPI的住院患者中,各种临床指标的患病率是多少?治疗方法的变化是否会对DTPI的发展产生影响?

研究启动与伦理

对质量保证和性能改进团队从两个LTCF收集的2014年和2015年期间的给药数据进行分析,结果显示,接受减压和每天两次敷用皮肤屏障膜治疗时,36%的DTPI发展成了3期或4期开放性PI。这项结果促使我们进行了可行性研究,该研究比较了皮肤屏障膜和PMD治疗于2015年10月至2017年5月在两个机构中发生的DTPI的效果。之所以选择PMD,是因为它在机构的处方集目录中属于新治疗方案、容易获得,并且有证据表明它对其他类型的伤口有益。

在2017年秋天开展的本回顾性比较分析项目分析了可行性研究中纳入的33例住院患者、共40例DTPI的结局。研究人员进行了系统性病历审查,根据2015年10月至2017年5月使用的治疗类型,比较了DTPI住院患者样本接受PMD或皮肤屏障膜治疗的效果。如果住院患者足部和小腿患有DTPI、年龄至少55岁,且接受过PMD或皮肤屏障膜与减压治疗,则将其病历纳入本项目中。

在可行性研究期间,各组的每例住院患者均按序接受DTPI的减压治疗。选择进入PMD组的住院患者提供了接受此新治疗方法的同意书,或研究获得了该住院患者的责任方的许可。PMD治疗包括将PMD的尺寸裁剪至略大于DTPI部位,以及敷用透明医用敷料覆盖先前敷用的PMD。该敷料每周更换两次。皮肤屏障膜湿巾每天敷用两次,且在敷用后让皮肤干燥。大学的机构审查委员会认为本项目可豁免批准。LTCF的企业控股公司、行政领导团队和医疗服务提供方的委员会成员批准了本项目。

设置和参与者

两个参与研究的LTCF均获得医疗保险(Medicare)和医疗补助(Medicaid)批准,私人付款的住院患者和床位数在两个机构中分别有大约90例和110例。两个机构位于美国东南部。这些机构提供短期和长期护理服务,包括生理和心理功能减退且患有多重合并症(例如PI和DTPI)的住院患者的康复和综合医疗护理。

由病历审查人提取数据、进行去标识化、审查是否符合纳入标准并发送给主要研究者。基于住院患者的治疗来制定样本,皮肤屏障组包含23例住院患者、27例DTPI,PMD组包含10例住院患者、13例DTPI。

数据收集和结局测量

每个机构中经过培训的病历专家从称为“电子病历系统”的电子病历程序中提取先前记录的数据。主要研究者给数据收集员进行了有关需外推和编码以进行数据输入的特定数据的培训。数据收集员接受了来自研究者的标准化培训,可确保数据收集和系统信息检索的准确性。从电子病历中检索针对每例住院患者记录的每例DTPI相关的数据。数据收集员对生成的数据报告进行去标识化处理并转移保存至私密、安全的PDF文件中。然后对PDF文件编码,转换为Microsoft Excel表格,整理到一个安全数据库中并存储到密码保护的文件中,以供主要研究者检索进行分析。

从病历中提取的数据由人口统计学数据和临床指标组成。人口统计学数据包括住院患者年龄、性别和种族。临床指标包括实验室测试结果(贫血和低蛋白血症筛查)、慢性疾病/合并症、健康史、功能状态和Braden量表评分。

Braden量表是一种用于确定PI发生风险的评估工具。Braden量表评分从不到9分到32分不等。Braden量表评分越低,PI发生风险越高。21 白蛋白水平低于3.2 g/dL(参考范围,3.5 -

5.2 g/dL)的住院患者表现为低蛋白血症,这可能反映出某些患者人群的营养状况下降。7 贫血确定为血红蛋白水平低于12至15 g/dL的参考范围。慢性疾病和合并症通过诊断或《国际疾病分类》(第10版)代码确定,包括外周血管疾病、痴呆、冠状动脉疾病和/或脑血管疾病。

其他数据包括既往PI史和近期骨科疾病史,例如下半身的任何骨折或手术。此外,检索关于住院患者进行日常生活支持的活动水平和任何长期非自愿活动史的信息。还记录了体重变化,即每例住院患者在确定DTPI之前是否有体重增加或体重减轻。

数据收集中记录了住院患者病历中记录的任何外周血管疾病的诊断结果。由于所有住院患者均没有确认诊断的踝肱压力指数记录,所以患有外周动脉疾病的住院患者被排除在外。此外,既往确诊的糖尿病或动脉溃疡住院患者也被排除在外。

结局变量包括DTPI恶化和变为开放性伤口时的PI分期(如适用)。

统计分析

使用Microsoft Excel描述性统计工具(华盛顿州雷德蒙)分析两组的数据。使用描述性统计描述样本。使用独立χ2检验比较各组恶化为开放性伤口或未恶化为开放性伤口的临床结局。P < .05被认为具有统计学意义。

结果

大多数参与者为白人女性,平均年龄为84岁。PMD组的年龄略大于皮肤屏障膜组(表1)。

表1.按治疗组统计的深部组织压力性损伤住院患者的人口统计学数据

一项简单的统计分析比较了两组之间的主要结局指标;根据独立χ2检验,差异不具有统计学意义(P=.3160)。在PMD组中,23%的DTPI恶化为开放性PI,而在皮肤屏障膜组中,41%的DTPI恶化为3期或4期开放性PI。在恶化为开放性伤口的DTPI中,PMD组的伤口中仅有两例恶化为3期开放性PI,仅有一例恶化为4期开放性PI。在皮肤屏障膜组的DTPI中,七例DTPI恶化为3期开放性PI,四例恶化为4期开放性PI(表2)。

表2.伤口结局

为增加DTPI发生风险的临床指标生成了描述性数据(表3)。

PMD组具有已知的DTPI临床指标的住院患者更多。需要两个人协助完成日常生活活动的住院患者数量是一个重要因素,占PMD组的80%和皮肤屏障膜组的61%。两组住院患者的平均Braden量表评分为15分,这表示发生DTPI的风险至少为中度。这与体重减轻和白蛋白分数较低有关,尤其是对于PMD组,该组90%发生体重减轻,60%患有低蛋白血症。患有重度痴呆(PMD组,60%;皮肤屏障膜组,30%)的住院患者也显示DTPI风险较高,确诊为冠状动脉疾病或脑血管疾病的住院患者也是如此(PMD组,90%;皮肤屏障膜组,78%)。为了研究剪切,收集了发生震颤或痉挛等异常下肢活动的住院患者的数据。在PMD组中,该临床指标可能导致70%的住院患者发生DTPI。有趣的是,尽管贫血没有达到其他研究中提及的显著性水平,但它是DTPI的一个指标(PMD组,40%;皮肤屏障膜组,39%)。

表3.按治疗组统计的深部组织压力性损伤住院患者的临床指标

讨论

本回顾性项目得出结论,皮肤屏障膜和减压未能防止DTPI恶化。在PMD组中,仅三例DTPI发展成开放性伤口,相比之下,皮肤屏障膜组中有11例DTPI发展成开放性伤口。虽然本项目没有统计功效来证明显著性,但结果表明,将当前的治疗方法从皮肤屏障膜与减压变为PMD与减压可能会带来受益。

本项目发现临床指标较多的住院患者发生DTPI恶化的风险更高,与既往研究一致。7,16 许多LTCF住院患者的医疗状况仍然是重要指标,包括体重减轻、白蛋白水平降低、异常活动 (如痉挛或震颤)、冠状动脉疾病和脑血管疾病。4,16 贫血、既往骨科手术或骨折、外周血管疾病和重度痴呆等指标与中度DTPI恶化风险相关;既往研究发现这些为高风险指标。4,7,16 有趣的是,平均而言,PMD组有更多DTPI恶化的临床指标,但却有更好的结局。这表明治疗和管理可以超过临床指标对DPTI进展的影响。

局限性

由于可行性研究期间诊断出DTPI的住院患者总数较少,便利样本量较小。尽管所有数据收集员均由同一个人在同一时间进行培训,但是没有进行评分者间信度测试。此外,由于针对DTPI的《国际疾病分类》(第10版)代码直到2019年才确定,数据收集员基于医疗服务提供方诊断来提取DTPI诊断数据。最后,需要注意的重要一点是,PMD可能不在所有医疗环境中均可用,这限制了研究结果的普遍性。

对临床实践的启示

减压和调整LTCF住院患者体位仍然是DTPI的建议治疗方法。但是,与DTPI恶化有关的并发症会影响LTCF住院患者并给医疗系统造成压力。本项目比较了两种不同的DTPI治疗方法,同时考虑了可能增加DTPI恶化风险的临床指标。尽管需要更多证据来考虑这些治疗方法的成本效益,但PMD可能会减少DTPI的恶化。因此,PMD可能对致力于为其住院患者提供有效医疗保健的机构具有吸引力,尤其是那些有高风险住院患者的机构。

结论

虽然预防是关键,但一旦DTPI发生,有一个快速且可靠的治疗方案来防止进一步恶化至关重要。通过减压和筛查恶化的临床指标来处理DTPI,以及采用预防性治疗(例如PMD),可以大大改善这些损伤的病程。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Autumn Henson*

DNP, GNP-BC, WCC Nurse Practitioner, Physicians Eldercare, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Laurie Kennedy-Malone

PhD, GNP-BC, FAANP, FGSA Professor of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

* Corresponding author

References

- National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel. NPIAP Pressure Injury Stages. 2016. https://cdn.ymaws.com/npiap.com/resource/resmgr/online_store/npiap_pressure_injury_stages.pdf. Last accessed June 15, 2020.

- Peart J. The aetiology of deep tissue injury: a literature review. Br J Nurs 2016;25(15):840-3.

- Honaker J, Brockopp D, Moe K. Suspected deep tissue injury profile. Adv Skin Wound Care 2014;27(3):133-40.

- Preston A, Rao A, Strauss R, Stamm R, Zalman D. Deep tissue pressure injury. Am J Nurs 2017;117(5):50-7.

- Gefen A. The future of pressure ulcer prevention is here: detecting and targeting inflammation early. EWMA 2018;19(2):7-13.

- Kestrel Health Information. Liquid skin protectors/sealants. WoundSource. 2019. www.woundsource.com/print/product-category/skin-care/liquid-skin-protectantssealants. Last accessed June 6, 2020.

- Ahn H, Cowan L, Garvan C, Lyon D, Stechmiller J. Risk factors for pressure ulcers including suspected deep tissue injury in nursing home facility residents. Adv Skin Wound Care 2016;29(4):178-90.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Nursing Home Data Compendium 2015 Edition. 2015. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/nursinghomedatacompendium_508-2015.pdf. Last accessed June 6, 2020.

- Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. AHRQ’s Safety Program for Nursing Homes: On-Time Pressure Ulcer Prevention. 2016. www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/long-term-care/resources/ontime/pruprev/index.html. Last accessed June 6, 2020.

- Grothier L. Management of residents with heel located pressure damage. J Community Nurs 2013;27(5):42-6.

- Levy A, Gefen A. Computer modeling studies to assess whether a prophylactic dressing reduces the risk for DTI in the heels of supine residents with diabetes. Ostomy Wound Manage 2016;62(4):42-52.

- Santamaria N, Gerdtz M, Sage S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of soft silicone multi-layered foam dressings in the prevention of sacral and heel pressure ulcers in trauma and critically ill patients: the border trial. Int Wound J 2013;12(3):302-8.

- Gefen A, Farid K, Shaywitz I. A review of deep tissue injury development detection and prevention: shear savvy. Ostomy Wound Manage 2013;59(2):26-35.

- Cutting K. Improving patient outcomes: bridging the gap between science and efficacy. Br J Nurs 2016;25(6):S28-S32.

- Levy A, Frank M, Gefen A. The biomechanical efficacy of dressings in preventing heel ulcers. J Tissue Viability 2015;24(1):1-11.

- Campbell N, Campbell D, Turner A. A retrospective quality improvement study comparing use versus nonuse of a padded heel dressing to offload heel ulcers of different etiologies. Ostomy Wound Manage 2015;61(11):44-52.

- McGinnis E, Stubbs N. Pressure-relieving devices for treating heel pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;12(2):1-31.

- Van Leen M, Schols J, Hovius S, Halfens R. A secondary analysis of longitudinal prevalence data to determine the use of pressure ulcer preventive measures in Dutch nursing homes, 2005-2014. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(09):10-20.

- Sullivan R. Use of a soft silicone foam dressing to change the trajectory of destruction associated with suspected deep tissue pressure ulcers. Medsurg Nurs 2015;24(4):237-42.

- National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel. Pressure injury prevention points. 2016. https://npiap.com/page/PreventionPoints#:~:text=Inspect%20all%20of%20the%20skin,elbows%20and%20beneath%20medical%20devices. Last accessed June 15, 2020.

- Kalowes P, Messina V, Li M. Five-layered soft silicone foam dressing to prevent pressure ulcers in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care 2016;25(6):e108-19.