Volume 41 Number 1

Comprehensive treatment, including topical care, for severe facial burn

Beihua Xu, Yajuan Weng and Suping Bai

Keywords dressing, Wound care, burn, Aquacel Ag

For referencing Xu B et al. Comprehensive treatment, including topical care, for severe facial burn. WCET® Journal 2021;41(1):16-20

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.1.16-20

Abstract

Background The face is the area central to a person’s identity that provides our most expressive means of communication. Facial burns are extremely serious medical problems. Topical interventions are currently the cornerstone of treatment of facial burns.

Case The authors report a 45-year-old woman who presented with a 1-hour old, 90% total body surface area (TBSA), including a mixture of deep II° and III° burns to her face. A silver impregnated dressing was used to care for the facial burn wounds.

Conclusion The silver impregnated dressing AQUACEL® Ag Hydrofiber® was found to be useful in nursing the facial burn wounds in this case.

Introduction

Burn injuries are an important health problem worldwide. In the USA, burns result in 45,000 admissions per year, of which more than 25,000 admissions are to hospitals with specialised burn centres1.

The head and neck area has been identified as the site most frequently affected by thermal injuries1. Facial burns are extremely serious due to the abundance of nerves and blood vessels2. In addition, complications such as facial scar hyperplasia, minor mouth deformity, upper eyelid ectropion and reduced or total lack of facial expressions can occur, resulting in psychological trauma and increased treatment costs3. Adequate facial burn care can improve the physical function and burned tissue recovery and relieve the psychological burden of patients4. A wide variety of agents are available for treatment of burn wounds, including ointments, creams and biological and non-biological dressings5.

Currently, there is no consensus on the optimal topical interventions for burn wound coverage to prevent or control infection or to enhance wound healing and minimise life-long scarring. Here, the authors report the case of a 45-year-old female case with a 1-hour old, 90% total body surface area (TBSA), including a mixture of deep II° and III° flame burns, cared for with a silver impregnated dressing with a satisfactory effect.

Background

The patient suffered flame burns due to ignition of a gas leakage. She stayed at home alone for 1 hour post-injury, refusing treatment, although there was no evidence of altered mental status at the time of injury. On arrival at her home, her family called emergency services, and she was sent to hospital.

Physical examination showed a body temperature of 36.2°C, a heart rate of 90 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, and a blood pressure of 168/104mmHg. The medical history surrounding the current facial burn wound was presented by the patient herself. The pain in burn wounds reached a score of 0–3/10 on the Visual Analogue Scale6. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item (GAD-7) Scale7 showed a score of 18, which meant the patient exhibited signs of severe anxiety. She had slightly fidgety and cold extremities and was thirsty, yet no fever or tachycardia or confusion. Her current and past medical history found no heart disease or lung disease or epidemiological history of COVID-19.

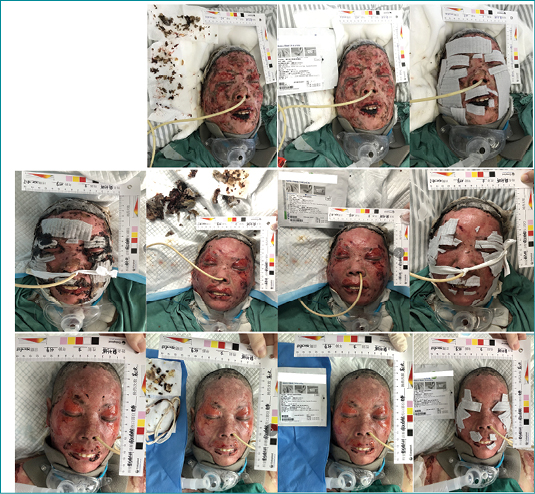

The overall percentage of burnt skin on the patient’s body was estimated by the Rule of 9s8. Burns spanned the face (4% II°) (upper row, Figure 1 shows the facial wound image on admission), neck (3% II°), anterior trunk (12% II°), posterior trunk (13% II°), bilateral upper arms (4% II°, 3% III°), bilateral forearms (3% II°, 3% III°), bilateral hands (2% II°, 1% III°), buttocks (4% II°), bilateral thighs (11% II°, 10% III°), bilateral legs (13% III°), and feet (4% III°), a total of 56% II° and 34% III°. The only unburned area seen was genitalia skin. There were small amounts of purulent secretions near the eyes, and the left auricle skin was intact; however, there was crust was inside the auricle. The skin of the right auricle was ruptured, and there was blood and purulent secretions in the auricle and ear canal. Though the skin condition around both eyes was poor, the eyeballs were not injured.

Further intensive examination showed burns of varying degree with the epidermal layer; these were moist, mostly hyperaemic and blanching with significant swelling. Vibrissa and hair on the scalp were partially scorched. Besides deep II° to III° burns, the patient was also diagnosed with inhalation injury and (hypovolaemic) burn shock.

Clinical management

Upon the diagnoses, the patient was placed on a suspended bed, with a room temperature of 25°C and humidity 60%. The standard wound care regimen for burn wounds in the authors’ hospital of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics was implemented for all burn wounds sustained. On day 1 (the next day after admission), and on days 4, 7, 11 and 18, the patient received excision, debridement and allografts to affected burn tissue with the exception of the face.

Assessment and management of facial burn wounds

Regarding the facial burns, the patient received initial treatment in the form of a thorough face wash with sterile 0.9% saline and removal of debris. The face was then dried with sterile gauze. Hair in the burned area was shaved off with electric clippers to facilitate wound assessment and management.

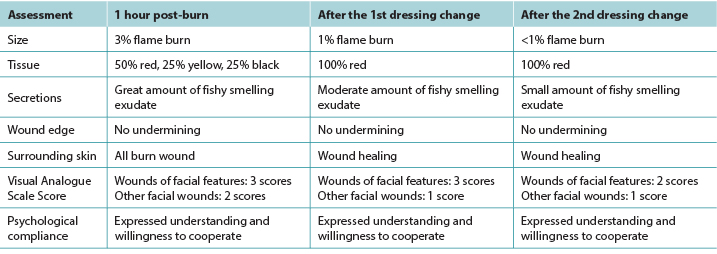

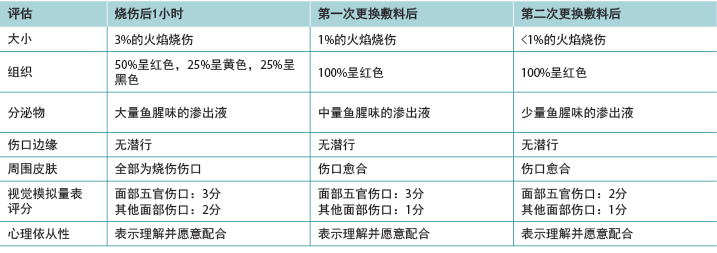

The wound care specialty team, including enterostomal therapists (ETs) and wound care nurses, collectively assessed the patient’s facial burns and identified several salient issues as indicated in Table 1. The wound care specialty team confirmed that the priorities of nursing care for this case were improving the skin integrity of burned skin through the application of an appropriate dressing to facilitate wound healing and minimise scarring, decreasing wound exudate and associated burn pain, and liaising with allied health professionals to assist in preventing malnutrition from hypermetabolism and trauma-induced anxiety. ET/wound care nurses alone would not be able to address pain, hypermetabolism or anxiety. The management of burn wounds is multidisciplinary.

Table 1. Assessment of patient’s facial wound

The first facial dressing was on day 0 (admission). The aim was to debride all non-viable burned tissue, to control the infection, and to implement effective exudate management. Before commencing the dressing procedure the patient was informed of the purpose of the facial wound care and the processes involved. Sterile gauze soaked in sterile water for injection was used to apply wet compresses to the face to moisten and clean the wound and facilitate easy removal of the gauze from the face to reduce the patient’s pain and discomfort. Conservative sharp wound debridement with sterile sharp instruments and forceps was then undertaken to clear facial eschar and necrotic tissue. Next, gauze was used to re-clean the facial wound. Finally, a silver dressing (AQUACEL® Ag Hydrofiber®, ConvaTec Ltd., UK) was chosen as the primary interface dressing. In order to permit eyelid movement, the eyelids were not covered with Aquacel® Ag sheets. The next day the patient’s facial wound dressings were fixed to the wound without displacement. A small amount of black exudate on the dressing was found. The patient had no complaints (upper row, Figure 1). The dressings were checked every day.

The second dressing change occurred on day 5. We found the wound bed had less necrotic tissue, exudate and odour were less, and the periwound skin had improved as per Table 1. The facial contour was more discernible because there was less swelling. The dressings were slowly removed to enable reassessment of the facial wound. The nursing regimen was repeated as for the first dressing. On day 6, the patient’s facial wound was observed, and only a small amount of exudate was found in the auricle. A sterile dry cotton ball was placed in the auricle. The patient was inspected and the dressing replaced as needed (middle row, Figure 1). The dressings were checked every day.

The clinical characteristics and improved condition of the facial wounds before the third dressing change on day 12 are listed in Table 1. The wound management regimen was assessed as being effective as the burn wounds continued to improve. Less dressing product was being applied, thereby exposing more of the face (lower row, Figure 1). The wound management goals of care remained the same: debriding to the maximum extent, controlling the infection, and implementing effective exudate management. The dressing regimen remained unchanged. There was a small amount of dry scab in the auricle, therefore the sterile dry cotton ball was not needed. The dressings were checked every day.

Figure 1. Face wound images

Upper: images before and after the 1st dressing change

Middle: images before and after the 2nd dressing change

Lower: images before and after the 3rd dressing change

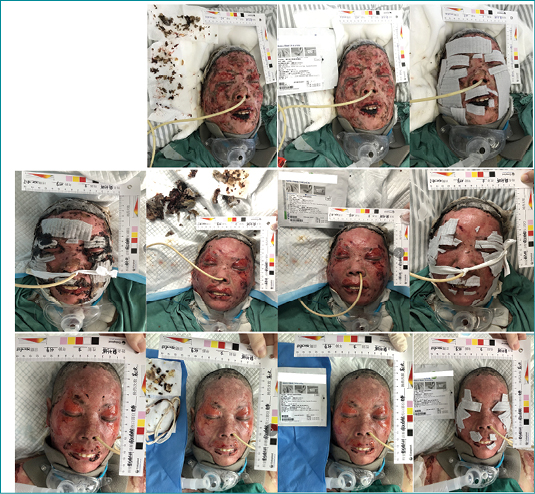

After the three facial wound dressing changes, the patient’s facial wounds had healed significantly (Figure 2).

Figure 2. After the three dressing changes

Discussion

Approximately two-thirds of communication is non-verbal, mediated principally by facial expression that also allows for individual identity. The healing of facial wounds is of great significance to patients, and effective intervention can reduce the chance of disfigurement. It is necessary to customise a personalised nursing plan according to the specific injury and condition of the patient’s wound.

Facial wound healing is affected by patient-related factors, the characteristics of the wound, and associated cellular repair processes with overlapping problems of microcirculation, local immunity, and dressing methods. The desired result is healing with minimal scarring and no functional defects2.

In this case, most facial tissue was lost from heat coagulation of the protein within the tissue from the gas explosion and resultant flames. The extent of tissue loss, however, was progressive and resulted from the release of local mediators, changes in blood flow, tissue oedema, and infection. Multiple difficulties for wound care were observed. First, assessment of facial wounds with cultures found Gram-positive bacterial (Staphylococcus aureus and extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii) infections. Second, the patient on admission was in a period of extensive tissue dissolution. The necrotic tissue was dissolving, and there was massive amounts of bloody and purulent exudate on the local area. The exudate spread to the concave parts of the face, and the eyes and ears of the patient were likely to be further compromised. Third, facial blood vessels and nerves are richer than other areas of the body. Carelessness during the administration of wound healing interventions can easily result in severe sequelae such as scar hyperplasia, decreased or loss of facial features. Fourth, the newly deposited granulation tissue was friable and prone to bleeding when touched. Fifth, the TBSA was large and deep and, in response, the body was hypermetabolic which resulted in prolonged wound healing. And last, in this accident, her son was also injured. The patient was less worried about her own condition and more about her son’s.

An effective dressing should be cheap, alleviate pain, prevent infection, be easy to handle, permit easy and early mobilisation, have no toxicity, cause no allergic reactions, and facilitate wound healing with a cosmetically acceptable scar.

Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, silver impregnated antimicrobial dressing is a soft, sterile, non-woven pad or ribbon dressing composed of sodium carboxymethylcellulose and 1.2% ionic silver which allows for a maximum of 12mg of silver for a 4x4 inch dressing. The silver in the dressing kills wound bacteria held in the dressing9. Caruso et al. compared the effect of Aquacel® Ag and that of silver sulphadiazine in the treatment of partial-thickness burns and observed that there was less pain and less anxiety during dressing changes with Aquacel® Ag and also that fewer analgesics and narcotics were used in patients treated with Aquacel® Ag10. Hindy11 concluded that Aquacel® Ag was found to be comparable to moist exposed burn ointment (MEBO), particularly allowing more rapid healing, and was psychologically less traumatic for those who cannot tolerate strong odour of dressings.

In this case, the dressing facilitated facial wound healing. However, these dressings are expensive, and the cost of each dressing change was not cheap, however, Robinson et al.12 reported that a cost-benefit study of the hydrofibre dressing demonstrated a significant saving of clinical time, owing to the fact that the largest component in the cost-benefit equation was staff time. The patient in this case attached great importance to family, had a high degree of compliance, and was willing to communicate so that pain and psychological problems could be identified and resolved in a timely manner.

A complication in this case was the amount of exudate from autolysing necrotic tissue which could not be estimated in advance, thereby limiting protective measures. Therefore, more clinical factors and potential for such complications to arise should be considered in the assessment and ongoing evaluation of wound healing to allow for more proactive measures to facilitate wound healing and meet nursing goals. The cost of dressing for wounds is high, and the affordability of patients and their families should be considered in the subsequent nursing process.

But still there are possible solutions. According to hospital policy, the manufacturer of the dressing is supposed to negotiate with medical insurance department to cover part of the fee. In practice, wound care nurses may be able to cut the dressings if this is in accordance with manufacturer guidelines. The cutting of the dressing into pieces instead of applying the dressing in one piece is mainly for two reasons. First, the facial contour is irregular, and cut dressings fit the size and shape of the burn wound better. Second, cutting the dressings reduces the fees for patients. In this case, it was identified that cutting the dressings did not incur any adverse effects or compromise wound healing of the facial burn.

Facial features are more sensitive to pain due to abundance of nerves2. In this case scenario, wound debridement and dressing changes caused pain which can easily cause poor coordination of patient care and place a heavy psychological burden on nursing staff, and slow down the process of facial wound care. By digitally assessing the location, nature and duration of wound pain, individualised pain care measures are formulated according to the characteristics of the patient, with psychological intervention as the mainstay. Before each dressing change, the authors discussed the procedure with the patient and told her the actions that indicated pain such as opening her mouth or nodding. During the dressing procedure, the patient was informed of the current dressing procedure steps, the site where debridement would be performed, and how much necrotic tissue was likely to be removed, so that the patient was psychologically prepared to cooperate with the dressing procedure. The dressing procedure was suspended when the patient sent a signal of pain.

The environment directly affects the psychological activities of patients, and creating a beautiful and comfortable environment has a good impact on the psychology of patients. The ward environment was clean and bright, with a temperature of 25°C and a humidity of 60%.

Establishing a good nurse–patient relationship is the key to the effectiveness of psychological care. Using polite language, being sincere, natural, gentle, calm, having friendly conversations yet being serious about the dressing process, always being optimistic and having a cheerful mood, paying attention to the attitude of dealing with others and your appearance, having a good demeanour and posture are all conducive to building respect, trust and cooperation.

Psychological support was applied everyday, providing psychological comfort, persuasion and guidance to patients to achieve the purpose of treatment. The authors strived for the close cooperation of family members and friends.

Conclusion

Burn injuries are an important health problem worldwide. Facial burns are extremely serious due to the abundance of nerves and blood vessels. This case study reports a case of a 45-year-old female case with a 1-hour old, 90% TBSA, including a mixture of deep II° and III° flame burns, cared for with a silver impregnated dressing, AQUACEL® Ag Hydrofiber®, with a satisfactory effect. Further studies are needed in order to find the ideal dressing for facial burn management.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient’s family, the surgical team and the nursing staff involved in the surgery and care.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was funded by grant from Guiding Program for Science and Technology of Changzhou Health Commission (WZ201905, to Beihua Xu).

面部严重烧伤的综合治疗,包括局部护理

Beihua Xu, Yajuan Weng and Suping Bai

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.1.16-20

摘要

背景 面部是个人身份的核心区域,提供了我们最具表现力的交流方式。面部烧伤是极其严重的医疗问题。局部干预是目前治疗面部烧伤的基石。

病例 作者报告了一例45岁的女性患者,患者就诊时距烧伤事故发生时间1小时,全身烧伤面积(TBSA)达90%,包括面部深II度和III度混合烧伤。使用了银浸渍敷料对面部烧伤伤口进行护理。

结论 本例患者使用银浸渍敷料AQUACEL® Ag Hydrofiber®对面部烧伤伤口进行护理,效果良好。

引言

烧伤是世界范围内的一个重大健康问题。在美国,每年有45000例次患者因烧伤入院,其中超过25000例次患者在设置专业烧伤治疗中心的医院住

院1。

调查发现,头颈部区域是最常发生烧伤的区

域1。由于面部有大量的神经和血管,面部烧伤是极为严重的医疗问题2。此外,还可能出现面部瘢痕增生、轻微口唇畸形、上睑外翻、面部表情减少或完全丧失等并发症,这会造成心理创伤,并增加治疗费用3。面部烧伤的充分护理可以改善患者的身体机能和烧伤组织的恢复,从而减轻患者的心理负担4。治疗烧伤伤口的药物种类繁多,包括软膏、乳膏和生物敷料及非生物敷料5。

目前,对于在覆盖烧伤伤口后既能预防或控制感染或者促进伤口愈合,又能最大限度地减少终生瘢痕形成的最佳局部干预治疗,尚无共识。在本文中,作者报告了一例45岁的女性病例,患者就诊时间距烧伤事故发生时间1小时,全身烧伤面积(TBSA)达90%,包括深II度和III度混合火焰烧伤,对其使用了银浸渍敷料进行护理,效果令人满意。

背景

患者因煤气泄漏着火而发生火焰烧伤。烧伤后独自在家待了1小时,拒绝治疗,但无证据表明受伤时精神状态有所改变。患者家属到家后拨打了急救电话,随后患者被送往医院。

体检显示患者体温36.2°C,心率90次/分,呼吸频率20次/分,血压168/104 mmHg。本次面部烧伤伤口的相关病史是由患者本人提供。根据视觉模拟量表,烧伤伤口的疼痛评分为0-3/10分6。根据七项广泛性焦虑障碍量表(GAD-7)7,评分为18分,这意味着患者表现出严重焦虑的症状。患者有轻微的烦躁不安、四肢发冷和口渴,但没有发热或心动过速或意识模糊。在患者的当前病史和既往病史中均没有发现心脏病、肺部疾病或COVID-19流行病学史。

根据九分法8估计出患者全身皮肤烧伤的总百分比。烧伤部位包括面部(4%,Ⅱ度)(上排,图1为入院时的面部伤口图片)、颈部(3%,Ⅱ度)、前躯干(12%,Ⅱ度)、后躯干(13%,Ⅱ度)、双侧上臂(Ⅱ度4%、Ⅲ度3%)、双侧前臂(II度3%、III度3%)、双侧手部(II度2%、III度1%)、臀部(II度4%)、双侧大腿(II度11%、III度10%)、双侧下肢(III度13%)、足部(III度4%),共计达56%的II度烧伤和达34%的III度烧伤。唯一未见烧伤的部位是外阴部皮肤。眼部附近有少量脓性分泌物,左耳廓皮肤完整,但耳廓内有痂皮。右耳廓皮肤破裂,耳廓及耳道内有血液和脓性分泌物。虽然双眼周围皮肤状况较差,但眼球并未受伤。

进一步深入检查发现,表皮层有不同程度的烧伤;这些烧伤部位潮湿,大多充血,并有明显的肿胀发白。鼻毛和头皮上的头发部分被烧焦。除深Ⅱ度至Ⅲ度烧伤外,患者还诊断出吸入性损伤和(低血容量性)烧伤休克。

临床管理

诊断后,将患者放置在悬浮床上,室温为25°C,湿度为60%。对所有持续的烧伤伤口,实施了作者所在医院针对烧伤伤口的标准伤口护理方案,即使用广谱静脉注射抗生素。第1天(入院后第二天)以及第4、7、11、18天,患者除面部外,其他部位均接受了切除术、清创术和累及烧伤组织的同种异体移植。

面部烧伤伤口的评估和管理

对于面部烧伤,患者接受了初始治疗,即用0.9%无菌生理盐水彻底清洗面部,并清除碎屑。然后用无菌纱布擦干面部。使用电动剪刀将烧伤区域的毛发剃掉,以方便伤口评估和管理。

伤口护理专业小组(包括造口治疗师[ET]和伤口护理护士)共同评估了患者的面部烧伤情况,并确定了表1所示的几个突出问题。伤口护理专业小组确认,本病例的护理重点是通过应用适当的敷料改善烧伤皮肤的皮肤完整性,以促进伤口愈合并最大限度地减少瘢痕形成,以及减少伤口渗出液和相关的烧伤疼痛,并与综合医疗保健人员联系,协助预防因高代谢和创伤诱发焦虑而导致的营养不良。仅靠ET/伤口护理护士将无法解决疼痛、高代谢或焦虑的问题。烧伤伤口的管理是多学科协作的过程。

第一次使用面部敷料是在第0天(入院时)。目的是清除所有坏死的烧伤组织,控制感染,并实施有效的渗出液管理。在开始进行敷料使用操作之前,已告知患者面部伤口护理的目的和所涉及的过程。使用注射用无菌水浸泡的无菌纱布对面部进行湿敷,以润湿和清洁伤口,并便于将纱布从面部轻松取下,进而减轻患者的疼痛和不适。然后用无菌锐利器械和手术镊进行保守性锐器清创,以清除面部焦痂和坏死组织。接着,用纱布重新清洁面部伤口。最后,选择含银敷料(AQUACEL® Ag Hydrofiber®,ConvaTec Ltd.,英国)作为接触性敷料。为了使得眼睑能够活动,没有使用Aquacel® Ag敷料片覆盖眼睑。第二天,患者面部伤口敷料固定在伤口处,未发生移位。发现敷料上有少量黑色渗出液。患者没有任何抱怨(如图1上排所示)。每天检查敷料的情况。

在第5天第二次更换敷料。我们发现伤口床上的坏死组织、渗出液和恶臭味均减少,伤口周围皮肤有所改善,见表1。由于肿胀减少,面部轮廓更加明显。慢慢移除敷料,以便再次评估面部伤口的情况。护理方案与第一次使用敷料时相同。在第6天观察患者面部伤口,发现耳廓内仅有少量渗出液。在耳廓内放置了一个无菌干棉球。对患者进行检查,并根据需要更换敷料(如图1中排所示)。每天检查敷料的情况。

깊1.뻤諒돨충꼬왯팀뮌

图1.面部伤口图片

上排:第一次更换敷料前后的图片

中排:第二次更换敷料前后的图片

下排:第三次更换敷料前后的图片

在第12天第三次更换敷料前,面部伤口的临床特征和改善情况见表1。因为烧伤伤口的持续好转,评估伤口管理方案为有效。所使用的敷料产品更少,因此有更大的面部面积暴露出来(如图1下排所示)。伤口管理的护理目标保持不变:最大限度地进行清创,控制感染,并实施有效的渗出液管理。敷料方案保持不变。耳廓内有少量干痂,因此不需要使用无菌干棉球。每天检查敷料的情况。

三次更换面部伤口的敷料后,患者的面部伤口已明显愈合(图2)。

图2.三次更换敷料后

讨论

大约三分之二的交流通过非语言方式进行,主要是通过面部表情来表达的,这也使得个人的身份得以确立。面部伤口的愈合对患者意义重大,有效的干预措施能降低毁容的几率。我们需要根据患者伤口的具体损伤和情况定制个性化的护理方案。

面部伤口愈合受患者相关因素、伤口特征以及相关细胞修复过程的影响,并与微循环、局部免疫、敷料方法等问题重叠。预期结果是愈合时极少形成瘢痕,且无功能缺陷2。

在本病例中,大部分面部组织丢失是因煤气爆炸和由此产生的火焰导致组织内蛋白质热凝固而发生的。但组织丢失的程度是进行性的,是局部介质释放、血流量改变、组织水肿和感染所致。本文观察到了伤口护理的多种困难。首先,使用培养物对面部伤口进行评估,发现革兰氏阳性菌(金黄色葡萄球菌和广泛耐药鲍曼不动杆菌)感染。其次,患者入院时正处于组织大量溶解期。坏死组织正在溶解,局部有大量血性、脓性渗出液。渗出液蔓延至面部凹陷部位,患者的眼睛和耳朵很可能进一步受损。第三,面部的血管和神经较身体的其他部位更为丰富。在伤口愈合干预措施的实施过程中,如果未妥善实施,则易导致严重的后遗症,例如瘢痕增生、面部特征减少或丧失。第四,新沉积的肉芽组织非常脆弱,触碰后易出血。第五,TBSA面积大且烧伤度深,因此身体出现高代谢,导致伤口愈合时间延长。最后,在这次事故中,患者的儿子也受伤了。患者不太担心自己的病情,更担心儿子的病情。

有效的敷料应价格低廉、能减轻疼痛、防止感染、易于操作、允许患者进行简单的早期活动、无毒性、不引起过敏反应、并且有助于伤口愈合,且留下的瘢痕在美观上可接受。

银浸渍羧甲基纤维素钠抗菌敷料是由羧甲基纤维素钠和1.2%银离子组成的柔软、无菌、无纺布敷料片或带状敷料,4x4英寸的敷料中银的含量最高达到12 mg。敷料中的银可杀灭敷料中存在的伤口细菌9。Caruso等人比较了Aquacel® Ag和磺胺嘧啶银治疗部分皮层烧伤的效果,观察到使用Aquacel® Ag在更换敷料时的疼痛感和焦虑感更小,而且使用Aquacel® Ag治疗的患者所用的镇痛药和麻醉药更

少10。Hindy11得出结论称,Aquacel® Ag与美宝湿润烧伤膏(MEBO)效果相当,特别是可以实现更快速的愈合,对于无法忍受敷料浓烈气味的患者而言,心理上的创伤更小。

在本病例中,敷料促进了面部伤口愈合。然而,这种敷料价格昂贵,每次更换敷料的费用并不便宜。但是Robinson等人12报告称,对亲水纤维敷料的成本收益研究表明大大节省了临床时间,而成本收益公式中占比最大的就是工作人员的时间。本病例患者十分重视家属,依从性高,愿意沟通,因此能够及时发现并解决疼痛和心理问题。

本病例的一个并发症是自溶性坏死组织导致了大量的渗出液,这一点无法提前估计,从而限制了保护措施的实施。因此,在对伤口愈合情况进行评估和持续评价时,应考虑更多的临床因素以及出现此类并发症的可能性,以便采取更积极的措施来促进伤口愈合和实现护理目标。伤口敷料的费用较高,在后续的护理过程中应考虑患者及其家属的承受能力。

但仍有可能的解决方案。根据医院的政策,敷料的制造商应该与医保部门协商,报销部分费用。在实际操作中,如果符合制造商的指南,伤口护理护士可以剪裁敷料。将敷料剪裁成小片而不是使用一整块敷料主要出于以下两个原因:第一,面部轮廓不规则,剪裁后的敷料会更贴合烧伤伤口的大小和形状;第二,剪裁敷料可以减少患者的费用。在本病例中,发现剪裁敷料未对面部烧伤产生任何不良影响,也不会影响伤口愈合。

面部五官由于神经丰富而对疼痛更为敏感2。在本病例中,伤口清创和更换敷料造成疼痛,容易导致患者护理配合不佳,给护理人员带来沉重的心理负担,从而减缓面部伤口护理的进程。通过对伤口疼痛的部位、性质和持续时间进行数字化评估,根据患者的特征制定个性化的疼痛护理措施,以心理干预措施为主要手段。在每次更换敷料前,作者都会与患者讨论敷料更换过程,并告诉患者通过张嘴或点头等动作表示疼痛。在更换敷料的过程中,告知患者当前的敷料更换操作步骤、待清创的部位,以及可能切除的坏死组织的数量,以便患者在心理上做好配合敷料更换过程的准备。当患者发出疼痛信号时,暂停敷料更换过程。

环境直接影响患者的心理活动,营造优美舒适的环境对患者的心理有良好的影响。病房环境干净明亮,温度为25°C,湿度为60%。

建立良好的护士患者关系是实现有效心理护理的关键因素。使用礼貌用语,态度诚恳、自然、温和、沉着,进行友好交谈,对敷料更换过程严谨认真,始终保持乐观开朗的心情,注意待人接物的态度和自己的外表,有良好的举止和姿态,这些都有利于建立护士患者之间的尊重、信任和合作关系。

日常应用心理支持,为患者提供心理安慰、劝说和引导,以达到治疗的目的。作者努力争取患者家属和朋友的密切合作。

结论

烧伤是世界范围内的一个重大健康问题。由于面部有大量的神经和血管,面部烧伤是极为严重的医疗问题。本病例研究报告了一例45岁的女性病例,就诊时间距烧伤事故发生时间1小时,TBSA达90%,包括深II度和III度混合火焰烧伤,对其使用了银浸渍敷料AQUACEL® Ag Hydrofiber®进行护理,效果令人满意。为了找到面部烧伤管理的理想敷料,还需要进一步的研究。

致谢

我们在此衷心感谢患者家属、手术团队及参与手术和护理的护理人员。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

本研究获得了常州市卫生健康委员会科学技术指导项目的研究基金(WZ201905,Beihua Xu

Author(s)

Beihua Xu

Registered Nurse, Wound Care Nurse

Wound Care Clinic, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (The First People’s Hospital of Changzhou), Jiangsu Province,

P. R. China

Yajuan Weng* MNurs Sci, MBusAdmin

Registered Nurse, Enterostomal Therapist, Chief Nurse Executive

Education Committee Chairperson WCET®

Wound Care Clinic, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (The First People’s Hospital of Changzhou), Jiangsu Province,

P. R. China

Email faith830406@hotmail.com

Suping Bai*

Registered Nurse, Enterostomal Therapist, Chief Nurse

Department of Burn and Plastic Surgery, Affiliated Hospital of Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, Jiangsu Province, P. R. China

Email bosuping@163.com

* Corresponding authors

References

- American Burn Association. Burn incidence and treatment in the United States; 2016 [cited 2016 Aug 17]. Available from: www.ameriburn.org/ resources_factsheet.php

- Singer AJ, Boyce ST. Burn wound healing and tissue engineering. J Burn Care Res 2017;38:e605–e613.

- Jeschke MG, van Baar ME, Choudhry MA, Chung KK, Gibran NS, Logsetty S. Burn injury. Nature Rev 2020;6:11.

- Spence RJ. The challenge of reconstruction for severe facial burn deformity. Plastic Surg Nurs 2008;28:71–76; quiz 77–78.

- Palmieri TL, Greenhalgh DG. Topical treatment of pediatric patients with burns. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002(8):529–34.

- Raghavan R, Sharma PS, Kumar P. Abacus VAS in burn pain assessment. Clin J Pain 1999;15:238.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–1097.

- Thom D. Appraising current methods for preclinical calculation of burn size: a pre-hospital perspective. Burns 2017;43:127–136.

- Caruso DM, Foster KN, Hermans MH, Rick C. Aquacel Ag in the management of partial-thickness burns: results of a clinical trial. J Burn Care Rehab 2004;25:89–97.

- Caruso DM, Foster KN, Blome-Eberwein SA, et al. Randomized clinical study of Hydrofiber dressing with silver or silver sulfadiazine in the management of partial-thickness burns. J Burn Care Res 2006;27:298–309.

- Hindy A. Comparative study between sodium carboxymethyl-cellulose silver, moist exposed burn ointment, and saline-soaked dressing for treatment of facial burns Annal Burn Fire Disaster 2009;22:131–137.

- Robinson BJ. The use of a hydrofibre dressing in wound management. J Wound Care 2000;9:32–34.