Volume 41 Number 1

Nurses specialised in wound, ostomy, and continence care: self-care during the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic

Janet L Kuhnke, Cathy Harley and Tracy Lillington

Keywords self-care, well-being

For referencing Kuhnke JL et al. Nurses specialised in wound, ostomy, and continence care: self-care during the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. WCET® Journal 2021;41(1):12-15

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.1.12-15

Abstract

Nurses specialised in wound, ostomy and continence (NSWOCs) who are working during a pandemic require engagement in self-care. Nurses across all sectors – clinical practice, education, leadership, policy, research and service – are each deeply aware of the burden of COVID-19, and provide the best care when they engage in self-care activities. Recent COVID-19 studies evaluating the mental health and well-being of staff working in the pandemic are of concern as staff are burdened by pandemic demands. Mental health and well-being, as well as skin and eye care, are essential. This paper talks about the Canadian perspective.

Introduction

In recent weeks, I read and re-read the 2020 article by Ramalho and colleagues1 and was moved by this paper where they so eloquently stated:

Health professionals, especially the nursing staff, are world renowned for their heroism, their struggle, and their self-sacrifice in caring for others. However, it is fundamental that self-care prevails at this time of pandemic, because it is necessary that professionals have their health preserved in order to collaborate with effective care for society (p. 8).

This article seeks to remind us of the human side to the pandemic and the importance of health workers and nurses deliberately engaging in self-care. The Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions created a 2020 ‘In Memoriam’ site to honour staff working in the healthcare sector in Canada who have died from COVID-19 while in the line of duty2. At the time of writing, 40 healthcare workers names are listed.

Background

The Government of Canada provides regular COVID-19 statistical updates for Canadians, nurses, healthcare professionals and workers. Wide-ranging information provided is vital in nationwide efforts to prevent and manage the pandemic3. To date, there have been a total of 801,057 cases, 45,711 cases are active, and a total of 20,702 persons have died, of which 73% are persons from long-term care and retirement home settings3. Provinces and territories, in turn, have established websites and communiques to relay to the public the current COVID-19 situation, assessment and testing centre availability, and progress with vaccine availability and administration rates.

Nursing During a Pandemic

Nursing’s contribution and expertise is highly visible during these challenging times4. Providing care to patients and families is demanding and can be traumatic. Fernandez and colleagues stated that, in response to the pandemic, nurses play a pivotal role, of which maintaining self-care is part5. Nurses and employers are reminded of the demands of providing compassionate care, especially during a crisis. Crane and Ward remind nurses that self-healing and self-care can help to maintain a balance between physical, emotional, mental and spiritual health6. Self-care for nurses crosses all sectors, including clinical practice, education, leadership, policy, research and service; each are deeply aware of the burden of COVID-19. For some nurses, conducting self-care may be a challenge as they manage demands of home, school and their ever-changing practice settings. This is especially true for those nurses specialised in wound, ostomy and continence (NSWOCs). NSWOCs and wound clinicians, in the beginning months of the pandemic, responded, adapted and moved from face-to-face wound, ostomy and continence clinics to a virtual platforms; however, some clinics were not considered an essential service, adding to the demand to provide skin and wound care services7.

The International Council of Nurses states that, when providing care during the pandemic, some nurses have experienced attacks – emotionally, physically and verbally8. In response, the Canadian Nurses Association have developed supportive resources and videos for nurses on topics such as mental health, vulnerable populations, ethics and staying healthy while working during a pandemic9.

Self-care is essential10, especially as nurses continue to respond to growing COVID-19 case numbers and to the families and communities who have experienced deep loss. Many nurses come to the profession due to their caring and compassionate nature, and thereby put the needs of patients ahead of their own6. However, recent COVID-19 studies evaluating the mental health and well-being of staff working in the pandemic are of concern. Rossi and colleagues report that healthcare workers in Italy involved in the pandemic were exposed to elevated level of stress and traumatic events; for this group, negative mental health outcomes were expressed11. Liu and colleagues report healthcare professionals who worked in intensive care during COVID-19 were committed to care delivery and were also physically and emotionally exhausted. When working in this crisis, healthcare staff showed their resilience and the spirit of “professional dedication” to overcome difficulties12. In addition, Lia et al., in a large study (n=1257) across 34 hospitals, reported that physicians and nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 experienced mental health issues that led to depression, anxiety, insomnia and distress, when compared to providers not caring for those with COVID-1913.

Personal Eye and Skin Care

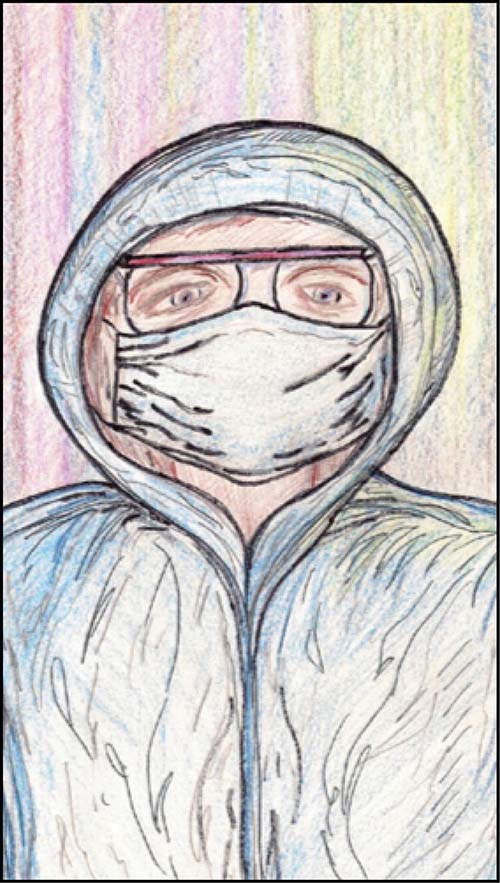

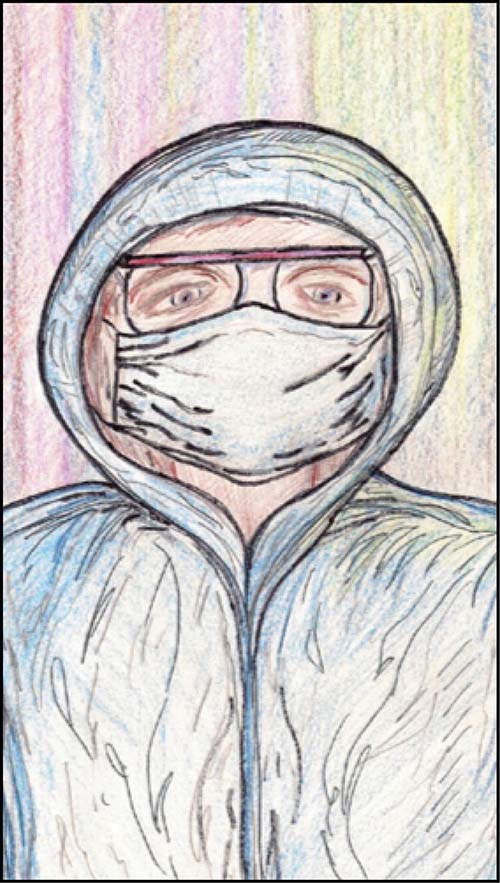

The peak Canadian body representing NSWOCs, the Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence, Canada (NSWOCC), created a personal protective equipment (PPE) toolkit in support of nurses’ prevention and management of skin damage, thereby promoting self-care14,15. During the pandemic, there has been an increase in the prolonged use of mandatory PPE14. As a result, nurses have experienced facial pressure injuries16. This impact on the skin of the face and head causes discomfort, adding to a reduction of enthusiasm for an already extensive workload; this can lead to anxiety. The ‘face of COVID-19’ was sketched in reflection by the lead author and in response to reading about COVID-19, viewing images on television, and in speaking to peers (Figure 1). In addition, excessive handwashing to reduce the risk of contamination leads to dermatitis, erosion and irritation, and maceration, creating a bleak outlook on working in the healthcare environment17. Furthermore, nurses may be prone to eye strain when spending long hours in front of computer screens conducting telehealth activities18.

Figure 1. The ‘face of COVID-19’.

The crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has also placed a strain on NSWOCs as they navigate new ways to provide safe and effective wound, ostomy and continence care. This has included the use of telehealth in order to provide skin and wound services19. This poses challenges such as the ability to develop a trusting relationship and rapport with the patient and family that typically occurs during patient visits, being unable to palpate a wound, or having to support vulnerable persons through an ostomy change using a phone or virtual platforms.

In relation to keeping your eyes safe a few tips are suggested17. In consultation with your health or eye-specialist, establish best practices in eye care when working on computers for extended periods of time. For example:

- to interrupt visual fatigue, adhere to the 20:20:20 rule, i.e. for every 20 minutes of screen time, look at an object 20 feet (6m) away for 20 seconds;

- if you are online for over 2 hours, a 15-minute break is recommended; and

- stay >50cm from the computer screen, and consider anti-fatigue spectacles, lenses with anti-reflection coatings, blue-blocking lenses, and eye lubricants17.

Self-Care Matters

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines self-care as a broad concept; they highlight that it is especially important that nurses practise self-care activities during a pandemic20. The WHO reminds us that feeling pressure and stress are to be expected when working in a pandemic. They recommend that, during work, it is important to take breaks, stay hydrated, eat sufficient and healthy foods, engage in activity, and be in contact with trusted peers and friends. Yet some nurses may experience avoidance by friends and family, often due to fear of the virus21.

Clancy and colleagues emphasise the importance of keeping nurses and staff healthy during a pandemic. They state healthcare staff and nurses need to engage in self-care to mitigate fatigue. Nurses live with the pressure to keep working despite the threat of illness, becoming exhausted, and potentially bringing the COVID-19 virus home to their family members. As healthcare professionals it is our responsibility to incorporate self-care in our professional practice, aiding us to provide care to others and maintain our health. We must make the effort to take care of ourselves physically and psychologically. Self-care allows us to maintain motivation, energy and empathy towards patients, families and communities that we serve.

The Canadian Association of Mental Health reminds us it is normal to feel stressed and anxious during the COVID-19 pandemic22. Furthermore, nurses are ethically responsible to conduct activities to maintain individual health and well-being physically, mentally, spiritually and psychologically6.

The Canadian Nurses Association outlines several key strategies on staying healthy during a pandemic:

- take care of your body, physically and emotionally, and avoid substances such as vaping, alcohol, caffeine;

- keep your mind healthy and engage in journalling, reading, sharing with others and drawing;

- stay virtually connected with friends, family, neighbours, your manager and peers;

- of note is the recommendation to set boundaries with blogs, newsfeeds and ‘breaking-news’ alerts as they can become daunting;

- follow trusted and credible COVID-19 sources such as the WHO, your country’s leading health agency, and your national nurses’ association(s); and finally

- ask for help in times of stress and ask for guidance to engage in a self-care plan by turning to trusted co-workers, friends to ask for support9.

Conclusion

Self-care is the greatest gift you can give to yourself while working in any nursing role during the pandemic. Staying healthy – spiritually, mentally, physically and emotionally – is important in sustaining one’s well-being and ability to provide effective safe care. Identify areas of self-care that can be improved. Develop a reasonable and achievable plan to support your self-care. We are together in providing care to clients during a pandemic. Be supportive and be kind.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

伤口、造口和失禁护理专科护士:2019冠状病 毒病(COVID-19)大流行期间的自我护理

Janet L Kuhnke, Cathy Harley and Tracy Lillington

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.1.12-15

摘要

在大流行期间持续工作的伤口、造口和失禁护理专科护士(NSWOC)需要实施自我护理。所有领域(临床实践、教育、领导力、政策、研究和服务)的护士都深刻体会到COVID-19所带来的重负,在实施自我护理活动时,他们才能同时提供最好的患者护理。近期评价在大流行期间工作人员的心理健康和幸福感的COVID-19研究,结果令人担忧,因为大流行引起的需求给工作人员带来了重担。心理健康、幸福感以及皮肤和眼部护理至关重要。本文从加拿大的角度进行阐述。

引言

最近几周,我阅读了Ramalho及其同事1撰写的一篇2020年的文章并且进行了反复阅读,这篇文章深深地打动了我。他们在文中强有力地指出:

专业医护人员,尤其是护理人员,以其英勇表现、奋斗精神和关爱他人的自我奉献行为而闻名于世。但是,在大流行时期,自我护理至关重要,因为只有保护了专业医护人员的健康,才能通力协作,为社会提供有效护理(第8页)。

本文旨在提醒我们关注大流行中人性的一面,以及医疗工作者和护士有意实施自我护理的重要性。加拿大护士工会联盟建立了一个2020“缅怀”网站,以纪念在工作岗位上因抗击COVID-19而死亡的加拿大医疗行业工作人员2。在撰写本文时,网站上列出了40名医护人员的姓名。

背景

加拿大政府定期为提供加拿大人、护士、专业医护人员和医疗工作者关于COVID-19的最新统计数据。所提供的广泛信息对全国范围内预防和管理大流行的工作至关重要3。到目前为止,累计共有801057例确诊患者,其中45711例患者正在接受治疗,共有20702例患者死亡,死亡患者之中的73%是来自长期护理和养老院环境中的患者3。各省和地区则建立了网站和公报,向公众传达COVID-19的最新情况、评估和可用的检测中心信息,以及疫苗供应和注射率的进展。

大流行期间的护理工作

在这个充满挑战的时期,护理工作的贡献和技术专长有目共睹4。为患者及其家属提供护理是一项艰巨的工作,可能会造成创伤。Fernandez及其同事表示,在应对这次大流行时,护士发挥了关键作用,其中包括保持自我护理5。护士及其所在的工作单位一直受到提醒,需要他们提供仁心护理,特别是在危机期间。Crane和Ward则提醒护士,自我疗愈和自我护理有助于保持身体、情感、心理和精神健康之间的平衡6。护士的自我护理涉及所有领域,包括临床实践、教育、领导力、政策、研究和服务;每个领域都深刻体会到COVID-19所带来的重负。对于一些护士而言,进行自我护理可能是一个挑战,因为他们要管理家庭、学校和不断变化的实践环境的需求。对于伤口、造口和失禁护理专科护士(NSWOC)而言,情况更是如此。在大流行爆发的最初几个月中,NSWOC和伤口临床医生作出了响应并进行了调整,从面对面的伤口、造口和失禁门诊转移到了虚拟平台;然而,患者并未将一些门诊视为一项必要的服务,这增加了提供皮肤和伤口护理服务的需求7。

国际护士理事会指出,在大流行期间提供护理时,一些护士经历了情感上、身体上和言语上的攻击8。为此,加拿大护士协会为护士开发了支持性资源和视频,主题包括心理健康、弱势群体、伦理和在大流行期间工作时保持健康9

自我护理至关重要10,特别是护士需要继续应对不断增加的COVID-19病例数量和经历了惨痛损失的家庭和社群之时。许多护士之所以从事这一职业,是因为他们富有爱心和同情心,因此将满足患者的需要放在自己的需要之前6。然而,近期评价大流行期间工作人员的心理健康和幸福感的COVID-19研究,结果令人担忧。Rossi及其同事报告称,意大利参与应对大流行的医疗工作者承受着更高水平的压力和创伤性事件;这个群体表现出了负面的心理健康结果11。Liu及其同事报告称,COVID-19大流行期间在重症监护病房工作的专业医护人员尽忠职守、提供护理,但同时他们也身心俱疲。在这场危机中工作时,医护人员表现出了坚韧不拔和克服困难的“敬业奉献”精神12。此外,Lia等人在一项涉及34家医院的大型研究(n=1257)中报告,与不照护COVID-19患者的医护人员相比,照护COVID-19患者的医生和护士经历了导致抑郁、焦虑、失眠和痛苦的心理健康问题13。

个人眼部和皮肤护理

代表NSWOC的加拿大最佳团体—加拿大伤口、造口和失禁护理专科护士组织(NSWOCC)开发了一种个人防护装备(PPE)工具包,用于支持护士预防和管理皮肤损伤,从而促进自我护

理14,15。在大流行期间,长期使用强制性个人防护装备的情况有所增加14。因此,护士出现了面部压力性损伤16。这种对面部和头部皮肤的影响会导致不适,进一步降低医护人员对本就繁重的工作的热情;这可能导致焦虑。本文的第一作者在阅读COVID-19相关报道、观看了电视上的各种形象以及与同行交谈后,在反思之中速写出了“COVID-19中的面孔”(图1)。除了前文所述的情况外,为了降低污染风险而过于频繁的洗手会导致皮炎、糜烂、刺激和浸渍,这更加营造了在医疗环境中工作前景不乐观的情绪17。此外,护士长时间在电脑屏幕前进行远程医疗活动可能会容易出现眼疲劳18。

图1.“COVID-19中的面孔”。

COVID-19大流行所造成的危机也给NSWOC带来了重担,因为他们正在探索新的方法来提供安全有效的伤口、造口和失禁护理。这包括使用远程医疗来提供皮肤和伤口服务19。这带来了一些挑战,例如与患者及其家属建立通常发生在患者就诊期间的信任关系和融洽关系的能力、无法对伤口进行触诊,或不得不通过使用电话或虚拟平台为弱势群体更换造口装置提供支持。

在保持用眼安全方面,有研究提出了一些建议17。咨询您的健康或眼科专家,建立长时间使用电脑工作时的最佳护眼操作。例如:

• 为了防止视觉疲劳,应坚持20:20:20原则,即每使用屏幕20分钟,则看20英尺(6米)外的物体20秒。

• 如果您在线的时间超过2小时,建议休息15分钟;以及

• 与电脑屏幕保持50 cm以上的距离,并考虑使用抗疲劳眼镜、带防反光膜的镜片、防蓝光镜片和滴眼液17。

自我护理事项

世界卫生组织(WHO)将自我护理定义为一个广义的概念;WHO强调,在大流行期间护士进行自我护理活动尤为重要20。WHO提醒我们,在大流行期间持续工作时,感到压力和紧张是意料之中的事。因此WHO建议,在工作期间,充分休息、补充水分、饮食足量且健康、参加活动,并与值得信赖的同龄人和朋友保持联系,这些都至关重要。然而,有些护士可能会受到朋友和家属的回避,通常是因为害怕病毒21。

Clancy及其同事强调了在大流行期间保持护士和其他医护人员健康的重要性。他们指出医护人员和护士需要进行自我护理,以便减轻疲劳。尽管面临疾病、疲惫以及有可能将COVID-19病毒带回家并传染给家属的威胁,护士们仍然承受着压力继续工作。作为专业医护人员,我们有责任将自我护理纳入我们的专业实践中,这有助于我们为他人提供护理并保持自己的健康。我们必须努力照顾好自己的身体和心理健康。自我护理使我们能够保持动力、精力和对我们所服务的患者、家庭和社群的同理心。

加拿大心理健康协会提醒我们,在COVID-19大流行期间感到压力和焦虑是正常的22。此外,从伦理的角度看,护士有责任开展活动,保持个人的身体、心灵、精神和心理上的健康和幸福感6。

加拿大护士协会概述了几种在大流行期间保持健康的主要策略:

• 从身体和情感上照顾好自己的身体,避免摄入电子烟、酒精、咖啡因等物质;

• 保持健康的心态,写日记、阅读以及与他人分享想法和绘画;

• 与朋友、家人、邻居、主管和同行通过虚拟方式保持联系;

• 值得注意的是,建议对博客、新闻推送和“突发新闻”提醒设定界限,这些信息可能会令人生畏;

• 关注值得信赖的可靠COVID-19信息来源,如WHO、您所在国家的主要卫生机构和护士协会;以及最后

• 在有压力的时候寻求帮助,通过向值得信赖的同事、朋友寻求支持,获得实施自我护理计划的指导9。

结论

自我护理是您在大流行期间从事任何护理工作时可以送给自己的最佳礼物。保持精神、心理、身体和情感上的健康对于保持个人的幸福感和提供有效安全护理的能力极为重要。确定可以进行改善的自我护理领域。制定一个合理且可实现的计划来支持您的自我护理。在大流行期间,我们并肩同行,为患者提供护理。支持他人和善待他人。

利益冲突

作者声明没有利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Janet L Kuhnke*

RN, BA, BScN, MS, NSWOCC

Dr Psychology, Assistant Professor, Cape Breton University, Sydney, NS, Canada

Email janet_kuhnke@cbu.ca

Cathy Harley

eMBA, RN, IIWCC

Chief Executive Officer, NSWOCC, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Tracy Lillington

RN, BScN, MN, NSWOCC

Clinical Nurse Educator, Cape Breton University, Sydney, NS, Canada

* Corresponding author

References

- Ramalho A, de Souza Silva Freitas P, Nogueira PC. Medical device-related pressure injury in health care professionals in times of pandemic. WCET Journal 2020;40(2):7–8. doi:10.33235/wcet.402.7-8

- Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions. In memoriam: Canada’s health care workers who have died of COVID-19; 2021 Jan 12. Available from: https://nursesunions.ca/covid-memoriam/

- Government of Canada. COVID-19 signs, symptoms and severity of disease: a clinical guide; 2020 Sept 18. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/guidance-documents/signs-symptoms-severity.html

- Phillips J, Catrambone C. Nurses are playing a crucial role in this pandemic-as always [Blog]; 2020, May 4. Available from: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/nurses-are-playing-a-crucial-role-in-this-pandemic-mdash-as-always/

- Fernandez R, Lord H, Halcomb E, Moxham L, Middleton R, Alananzeh I, et al. Implications for COVID-19: a systematic review or nurses’ experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. Int J Nurs Stud 2020;111:1–8.

- Crane PJ, Ward SF. Self-healing and self-care for nurses. AORN J 2016;104(5):386–399.

- Kuhnke JL, Jack-Malik S, Botros M, Rosenthal S, McCallum C. Early days of COVID-19 and the experiences of Canadian wound care clinicians: preliminary findings. Wounds Canada Conference [Poster]; October 2020.

- International Council of Nurses. ICN calls for government action to stop attacks on nurses at a time when their mental health and wellbeing are already under threat because of COVID-19 pandemic; 2020 Apr 29. Available from: https://www.icn.ch/news/icn-calls-government-action-stop-attacks-nurses-time-when-their-mental-health-and-wellbeing

- Canadian Nurses Association. Resources and FAQs; 2020. Available from: https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/coronavirus-disease/faqs-and-resources

- Purdue University Global. The importance of self-care for nurses and how to put a plan in place; 2019. Available from: https://www.purdueglobal.edu/blog/nursing/self-care-for-nurses/

- Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, Di Lorenzo G, Di Marco A, Siracusano A, et al. Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA 2020:3(5):e2010185. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185

- Liu A, Luo D, Haase JE, Guo A, Wang AQ, Liu S, et al. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. The Lancet 2020;9:e790–798.

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA 2019;Mar:3(3):e203976. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

- LeBlanc K, Heerschap C, Butt B, Bresnai-Harris J, Wiesenfeld L. Prevention and management of personal protective equipment skin injury: update 2020. NSWOCC 2020:1–10. Available from: http://nswoc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PPE-Skin-Damage-Prevention_compressed-2.pdf

- Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Institute. PPE toolkit; 2020. Available from: https://nswoc.ca/ppe/

- Smart H, Opinion FB, Darwich I, Elnawasany MA, Kodange C. Preventing facial pressure injury for healthcare providers adhering to COIVD-19 personal protective equipment requirements. WCET 2020;40(3):9–18.

- Kantor J. Behavioural considerations and impact of personal protective equipment (PPE) use: early lessons from the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. J Am Acad Dermat 2020 March 11;82(5):1087–1088. Available from: https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(20)30391-1/fulltext

- Munsamy A, Chetty V. Digital eye syndrome – COVID-19 lockdown side-effect. Sth Af Med J 2020;110(7):569. doi:10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v110i7.14906

- Mahoney M. Telehealth, telemedicine and related technologic platforms: current practice and response to COVID-19 pandemic. JWOCN 2020;47(5):439–444.

- World Health Organization. Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak; 2020 Mar 12. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf

- Clancy D, Gaisser D, Wlasowicz GK. COVID-19 and mental health: self-care for nursing staff. Nursing 2020;50(9):60–63.

- Canadian Association of Mental Health. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic; 2020. Available from: https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-health-and-covid-19