Volume 41 Number 2

Practice Implications from the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline 2020

Laurent O. Chabal, Jennifer L. Prentice and Elizabeth A. Ayello

Keywords ostomy, education, stoma, culture, guideline, International Ostomy Guideline, IOG, ostomy care, peristomal skin complication, religion, stoma site, teaching

For referencing Chabal LO et al. Practice Implications from the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline 2020. WCET® Journal 2021;41(2):10-21

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.2.10-21

Abstract

The second edition of the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline (IOG) was launched in December 2020 as an update to the original guideline published in 2014. The purpose of this article is to introduce the 15 recommendations covering four key arenas (education, holistic aspects, and pre- and postoperative care) and summarise key concepts for clinicians to customise for translation into their practice. The article also includes information about the impact of the novel coronavirus 2019 on ostomy care.

Acknowledgments

The WCET® would like to thank all of the peer reviewers and organizations that provided comments and contributions to the International Ostomy Guideline 2020. Although the WCET® gratefully acknowledges the educational grant received from Hollister to support the IOG 2020 development, the guideline is the sole independent work of the WCET® and was not influenced in any way by the company who provided the unrestricted educational grant.

The authors, faculty, staff, and planners, including spouses/partners (if any), in any position to control the content of this CME/NCPD activity have disclosed that they have no financial relationships with, or financial interests in, any commercial companies relevant to this educational activity.

To earn CME credit, you must read the CME article and complete the quiz online, answering at least 7 of the 10 questions correctly. This continuing educational activity will expire for physicians on May 31, 2023, and for nurses June 3, 2023. All tests are now online only; take the test at http://cme.lww.com for physicians and www.NursingCenter.com/CE/ASWC for nurses. Complete NCPD/CME information is on the last page of this article.

© Advances in Skin & Wound Care and the World Council of Enterostomal Therapists.

Introduction

Guidelines are living, dynamic documents that need review and updating, typically every 5 years to keep up with new evidence. Therefore, in December 2020, the World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® (WCET®) published the second edition of its International Ostomy Guideline (IOG).1 The IOG 2020 builds on the initial IOG guideline published in 2014.2 Hundreds of references provided the basis for the literature search of articles published from May 2013 to December 2019. The guideline uses several internationally recognised terms to indicate providers who have specialised knowledge in ostomy care, including ET/stoma/ostomy nurses and clinicians.1 However, for the purposes of this article, the authors will use “ostomy clinicians” and “person with an ostomy” to be consistent.

Guideline development

A detailed description of the IOG 2020 guideline methodology can be found elsewhere.1 Briefly, the process included a search of the literature published in English from May 2013 to December 2019 by the authors of this article, who comprise the Guideline Development Panel. More than 340 articles were reviewed. For each article identified, a member of the panel would write a summary, and all three would then confirm or revise the ranking of the article evidence. The evidence was categorised and defined and compiled into a table that is included in the guideline and can be accessed on the WCET® website. The strength of recommendations were rated using an alphabetical system (A+, A, A−, etc). Feedback was sought from the global ostomy community, and 146 individuals and 45 organizations were invited to comment on the findings. Of these, 104 individuals and 22 organizations returned comments, which were used to finalise the guideline.

Guideline overview

Because the WCET® is an international association with members in more than 65 countries, there is a strong emphasis on diversity of culture, religion, and resource levels so that the IOG 2020 can be applied in both resource-abundant and resource-challenged countries. The forward was written by Dr Larry Purnell, author of the Purnell Model for Cultural Competence (unconsciously incompetent, consciously incompetent, consciously competent, unconsciously competent).3-5 As with the 2014 guideline, the WCET® members and International Delegates were invited to submit culture reports from their country, and 22 were received and incorporated into the guideline development.

Because the IOG 2020 is intended to serve as a guide for clinicians in delivering care for persons with an ostomy, new to this edition is a section on guideline implementation. Also new is a recommendation for nursing education. A glossary of terms and helpful educational resources are also included in the various appendices. The 15 IOG 2020 recommendations are listed in Table 1. The recommendations have been translated into Chinese (Supplemental Table 1), French (Supplemental Table 2), Portuguese (Supplemental Table 3), and Spanish (Supplemental Table 4) and are also available on the WCET® website (www.wcetn.org).

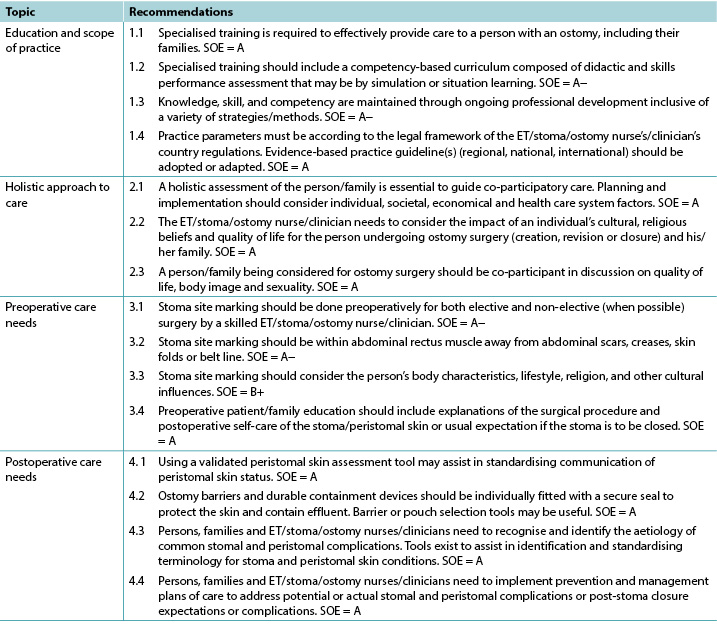

Table 1 WCET® International OStomy Guideline 2020 Recommendations

©WCET® 2020, used with permission.

Abbreviations: ET, enterostomal therapy; SOE, strength of evidence.

Education

The evidence supports four IOG 2020 recommendations about education (Table 1). A person who has surgery resulting in the creation of an ostomy needs knowledge regarding their type of stoma, care strategies such as ostomy pouches, and the impact the ostomy will have on their lifestyle.6 Accordingly, the needs of these patients go beyond what may be taught in initial nursing education programs. Zimnicki and Pieper7 surveyed nursing students and found that just under half (47.8%) did not have experience in caring for a patient with an ostomy. For those who did, they felt most confident in pouch emptying.7 Findings by Cross and colleagues8 also support that staff nurses without specialised ostomy education felt more confident in emptying the ostomy pouch as opposed to other ostomy care skills. Duruk and Uçar9 in Turkey and Li and colleagues10 in China also reveal that staff nurses lack adequate knowledge about the care of patients with ostomies. Better ostomy care outcomes have been reported when patients are cared for by nurses who have had specialised ostomy education. This includes research in Spain by Coca and colleagues,11 Japan by Chikubu and Oike,12 and the UK by Jones.13

For over 40 years, the WCET® has promoted the importance of specialised ostomy education for nurses to better meet the needs of patients and their families.6 Other societies such as the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing Society in the US; Nurses Specialised in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada; and the Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK have also advocated for specialised nursing education. The suggested modifications include competence-based curricula and checklists of skills and professional performance necessary for the specialised nurse to provide appropriate care to patients with an ostomy and their families.14-17 Evidence-based practice requires that healthcare professionals keep abreast of new techniques, skills, and knowledge; lifelong learning is necessary.

Holistic aspects of care: culture and religion

The literature supports three highly ranked recommendations related to holistic care within the IOG 2020 (Table 1) and confirms the necessity of taking them into account when caring for individuals with an ostomy.

Ostomies can impact individuals in different domains such as day-to-day life, overall quality of life, social relationships, work, intimacy, and self-esteem. A holistic approach to care aims to acknowledge and address the patient’s need at a physiological, psychological, sociological, spiritual, and cultural level,18 especially when the patient’s situation is complex.19 Therefore, implementing a holistic approach to practice is crucial to address all of the potential issues.20

Many tools exist to assess patients’ quality of life, self-care adjustment, social adaptation, and/or psychological status.21,22 They provide important information to nurses in their clinical decisions making, although as always clinical judgment remains relevant. Because holistic care is multidimensional, using various methods will allow an integrative and global approach to caring for patients with ostomies.

The World Health Organization’s definition of health23 is still relevant today. An individual’s origins, beliefs, religion, culture, gender, and age will influence his/her interpretation of illness and diseases.24-26 For healthcare professionals, the need to understand these influences and their real impacts on the patient, family, and/or caregiver(s) is essential because it will provide key information to co-construct ostomy care.

Dr Larry Purnell’s Model for Cultural Competence3,4 can be readily applied to ostomy care.5 It can help nurses to deliver culturally competent care to patients with an ostomy. Integrating effective cultural competence will improve relationships among patients, families, and healthcare professionals,27 especially if patients and/or families are finding it difficult to cope.28

Specialised and nonspecialised nurses have a key role in patient, family, and caregiver education.29 They will, step by step, help support the development of specific skills and implementation of personalised adaptive strategies. Nurses’ advice and support can decrease ostomy-related complications,13,30,31 and listening to and addressing patient emotions will improve individuals’ self-care.32

Taking into account the International Charter of Ostomate Rights33 during provision of ostomy care will increase patients’ quality of life, because it supports patient empowerment and reinforces the partnerships among patients, families, caregivers, and healthcare professionals.

Section 6 of the IOG 2020 provides an international perspective on ostomy care. With contributions from 22 countries, this version is more inclusive than the previous one.2 It is the authors’ hope that it will help ostomy clinicians around the world when taking care of patients from another culture, background, or belief system and therefore give them better skills to address each individual’s needs.

Preoperative Care And Stoma Site Marking

As seen in Table 1, there are four recommendations that address preoperative care and stoma site marking. The literature emphasises preoperative education for patients who are about to undergo ostomy surgery, which includes preoperative site marking. Fewer complications are seen in persons who have their stoma sites marked before surgery.34,35

Because specialised nurses may not be available 24/7, patients who undergo unplanned/emergency surgery may not benefit from preoperative education and stoma site marking. Accordingly, the literature supports the training of physicians and nonspecialty nurses to do stoma site marking.34-37 Zimnicki36 completed a quality improvement project to train nonspecialised nurses in stoma site marking. This project significantly increased the number of patients who had preoperative stoma site marking and education.36

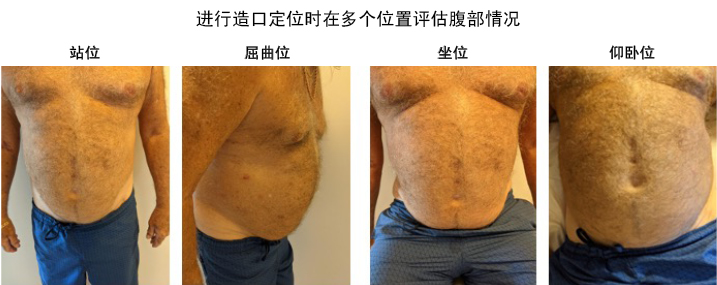

Stoma site marking is an important art and skill that is beyond the scope of this article to describe in detail. Major principles include observation of the patient’s abdomen while standing, sitting, bending over, and lying down (Figure 1).37-41 There are at least two techniques for identifying the ideal abdominal location.42-52 Those interested might consult the references42-60 as well as the WCET® webinar or pocket guide on stoma site marking (www.wcetn.org).52

Assess the abdomen in multiple positions when doing stoma siting

Figure 1 positions for stoma site marking ©2021 Ayello, used with permission.

Postoperative Care

The IOG 2020 lists four recommendations for postoperative care to assist ostomy clinicians to detect, prevent, or manage and thereby minimise the effect of any peristomal complications (Table 1).

Successful postoperative recovery following ostomy surgery is dependent on multiple factors from the perspective of both the ostomy clinician and person with an ostomy. All members of the care team, including the patient, must have a heightened awareness of preventive or remedial strategies for common problems that may occur with the formation of a new stoma, refashioning of an existing stoma, or stoma closure. The ability to recognise and effectively manage potential or actual postoperative ostomy and peristomal skin complications (PSCs) has inherent short- and long-term ramifications for the health, well-being, and independence of the persons with an ostomy61-63 and for health resource management.64-66

Postoperative ostomy complications may manifest as early or late presentations. Early complications such as mucocutaneous separation, retraction, stomal necrosis, parastomal abscess, or dermatitis may occur within 30 days of surgery. Later complications include parastomal hernias (PHs) and stomal prolapse, retraction, or stenosis.63,67,68

However, the most common postoperative complications are PSCs.69 Frequently cited causes of PSCs are leakage,70,71 no preoperative stoma siting,35 poor surgical construction techniques,72 ill-fitting appliances, and long wear time of appliances.71,73

Common PSCs include acute and chronic irritant contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis, the former arising from prolonged contact with feces or urine on the skin eventually causing erosion (Figure 2). Assessment of the abdomen, stoma, stoma appliance, and accessories in use as well as the patient’s ability to care for the stoma and correctly reapply his/her appliance is essential to determine the cause of leaks. Skin care, depending on the severity of irritation or denudation, may involve the use protective pectin-based powders or pastes, skin sealants (acrylate copolymer or cyanoacrylates wipes or sprays), and protective skin barriers. Adjustments to the type of appliance used and wear time may also be required ameliorate acute and prevent chronic irritant contact dermatitis.61,70,74

Figure 2 irritant dermatitis ©2021 Chabal, used with permission.

Allergic contact dermatitis results from an adverse reaction to substances within products applied to the skin during cleansing or skin protection used prior to appliance application or removal or that are part of the appliance itself.74,75 Compromised skin usually reflects the shape of the appliance if it is the allergen or the area where secondary skin care products have been used. Affected skin may have the appearance of a rash; be reddened, blistered, itchy, or painful; or exude hemoserous fluid (Figure 3). Patch testing small areas of skin well away from compromised skin and the stoma may be required to identify specific causative agents and/or assess the suitability of other skin barrier products used to gain a secure seal around the stoma.70,75

Figure 3 allergic contact dermatitis ©2021 Chabal, used with permission.

Parastomal hernias are a latent complication that also contributes to PSCs. Causes include surgical technique, the size and type of stoma, abdominal girth, and age and medical conditions such as prior hernias and diverticulitis fluid. Education of surgeons and prophylactic insertion of polypropylene mesh during surgery as well as postoperative patient education may decrease PH incidence (Figure 4).68,76,77 Further, providers must assess and measure the patient’s abdomen at the level of the stoma to choose the most appropriate support garment required to manage the degree of PH protrusion, prevent further exacerbation, and allow the stoma to continue to function normally.78 The ostomy appliance/pouch in use will also need to be frequently reassessed to address any changes in the size of the stoma.

Figure 4 parastomal hernia ©2021 Chabal, used with permission.

The IOG 2020 cites numerous tools that ostomy clinicians can use to effectively identify and classify PSCs79,80,81 and select appropriate skin barriers and appliances to manage PSCs.62,82

Finally, of increasing importance to improve the postoperative quality of life of individuals with an ostomy, reduce ostomy complications and associated readmissions, and enhance interprofessional practice are the use of early or enhanced recovery programs after surgery,83,84 ongoing education and discharge monitoring programs,68,85 and telehealth modalities for counseling and remote consultation.86,87

Guideline implementation

For clinical guidelines to result in positive outcomes for the intended patient populations, the proposed recommendations need to be adopted into daily practice. Multiple strategies are required to facilitate adoption,88,89 and guidelines should be reviewed and adapted for specific clinical contexts.90 Prior thought, therefore, is required regarding how guidelines will be disseminated and implemented. Potential barriers to guideline implementation may include a lack of resources, competing health agendas, or a perceived lack of interest in ostomy care as a medical/nursing subspecialty with no “champion” to advocate for and facilitate implementation. Last, guidelines may be seen as too prescriptive. The section on guideline implementation within the IOG 2020 provides advice, and readers are directed to the full guideline for more information.

Impact of Covid-19 on ostomy care

The review of the evidence for the IOG 2020 preceded the advent the novel coronavirus 2019. During the pandemic, there have been anecdotal reports of ostomy clinicians being reassigned to care for other patients. The extent and impact of this have yet to be researched. In the meantime, virtual visits may provide a safe alternative to in-person care for patients and providers.91 A study by White and colleagues92 reported on the feasibility of virtual visits for persons with new ostomies; 90% of patients felt that these visits were helpful in managing their ostomy.92 However, another study found that only 32% of the respondents knew that telehealth was an option.93 Further, 71% “did not think [their issue] was serious enough to seek assistance from a healthcare professional,”93 although 57% reported some peristomal skin occurrence during the pandemic.93 In descending order, the types of skin issues reported were redness or rash (79%), itching (38%), open skin (21%), bleeding (19%), and other concerns (7%).93

Conclusions

The IOG 2020 aims to provide clinicians with an evidence framework upon which to base their practice. The 15 IOG 2020 recommendations are applicable in countries where resources are abundant (nurses and healthcare professionals trained in ostomy care with manufactured appliances/pouches), as well as in countries with limited resources (nonspecialised nurses, healthcare professionals, and laypersons who create ostomy equipment from available local resources to contain the ostomy effluent). Specialised knowledge is needed to assist persons with an ostomy in learning how to apply, empty, and change their appliance/pouch, but living with an ostomy is more than that. All aspects of the patient need to be considered.

Holistic patient care should be individualised and address diet, activities of daily living, sexual life, prayer, work, medications, body image, and other patient-centered concerns. Preoperative stoma siting has been linked to better postoperative outcomes. Early identification and intervention for PSCs requires adequate teaching, as well as awareness of when to seek professional help. Nurses who have specialised knowledge in ostomy care can improve quality of life for persons with an ostomy, including those who experience PSCs.95 It is the authors’ hope that the IOG 2020 will enhance care outcomes and rehabilitation for this population.

Practice pearls

- Patients who are cared for by healthcare professionals with specialised ostomy knowledge experience better care outcomes.

- There are clinical tools to assist with peristomal skin assessment and appliance requirements.

- Pre- and postoperative patient and family education needs to be holistic and individualised.

- Patients who undergo presurgical stoma siting experience fewer complications.

- The most common PSC is leakage leading to irritant dermatitis.

- Telehealth and remote consultation might be advantageous in providing adjunct guidance to people with ostomies.

2020版WCET®《国际造口指南》的实践意义

Laurent O. Chabal, Jennifer L. Prentice and Elizabeth A. Ayello

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.2.10-21

摘要

第二版WCET®《国际造口指南》(IOG)于2020年12月推出,是对2014年发布的原版指南的更新。本文旨在介绍涵盖四个关键领域(教育、整体方面、术前护理和术后护理)的15项建议,并总结关键概念,供临床医生根据具体情况转化为实践操作。本文还包括关于2019新型冠状病毒对造口护理影响的信息。

致谢

WCET®衷心感谢所有为2020版《国际造口指南》提供意见和做出贡献的同行评审人和组织。WCET®衷心感谢Hollister为支持IOG 2020的编写而提供的教育资助,但该指南是WCET®单独完成的独立作品,未受到提供无限制教育资助的公司的任何影响。

作者、教职员、工作人员和计划人员(包括配偶/伴侣[如有])等有任何立场控制本CME/NCPD活动内容的人士均已披露,他们与本教育活动相关的任何商业公司均没有财务关系或财务利益。

如果要获得CME学分,您必须阅读CME文章并完成在线测验,并正确回答10个问题中的至少7个问题。这项持续教育活动将于2023年5月31日对医生截止,对护士则于2023年6月3日截止。现在所有的测验均仅能在线完成,医生和护士可分别在http://cme.lww.com和www.NursingCenter.com/CE/ASWC进行测验。完整的NCPD/CME信息在本文的最后一页提供。

© 《皮肤与伤口护理进展》和世界造口治疗师委员会(World Council of Enterostomal Therapists)。

引言

指南是需要进行审查和更新的动态活文件,通常需每五年更新一次,以跟上新证据的发展。因此,世界造口治疗师委员®(WCET®)于2020年12月出版了第二版《国际造口指南》(IOG)。1IOG 2020是以2014年出版的原版IOG指南为基础编写而成。

2许多参考文献为2013年5月至2019年12月发表文章的文献检索提供了基础。本指南使用数个国际公认的术语来表示拥有造口护理专业知识的医护人员,包括ET/造口/造口护士和临床医生。1 但就本文而言,作者将使用“造口临床医生”和“造口患者”以保持一致。

制定指南

关于IOG 2020指南方法的详细描述可在别处找到。1简而言之,该过程包括由本文作者组成的指南制定小组对2013年5月至2019年12月期间以英文发表的文献进行检索。共审查了340多篇文章。每确定的一篇文章,将由一名小组成员撰写一篇总结,然后所有三名成员将确认或修改文章的证据等级。我们对证据进行了分类和定义,并编制成一个表格,其包含在指南中,可在WCET®网站上查阅。采用字母系统(A+、A、A-等)对推荐强度进行评级。我们向全球造口群体征求反馈意见,并邀请146名个人和45个组织针对调查结果提出意见。其中,104名个人和22个组织回复了其意见,这些意见被用于指南的定稿过程中。

指南概述

WCET®是一个国际协会,其会员遍布65个以上国家,十分强调文化、宗教和资源水平的多样性,因此IOG 2020在资源丰富和资源短缺的国家均具有适用性。序言是由Purnell文化能力模型(无意识无能力、有意识无能力、有意识有能力、无意识有能力)的作者Larry Purnell博士所撰写。3-5与2014版指南一样,WCET®会员和国际代表受邀提交其国家的文化报告,我们共收到22份报告并将其纳入指南的制定过程中。

IOG 2020旨在用作临床医生为造口患者提供护理的指南,因此本版指南新增了关于指南实施的部分。本版指南也新增了对护理教育的建议。各附录中还包括术语表和有用的教育资源。IOG 2020的15项建议如表1所示。这些建议已被翻译成中文(补充表1)、法语(补充表2)、葡萄牙语(补充表3)和西班牙语(补充表4),也可在WCET®网站(www.wcetn.org)获取。

教育

证据支持IOG 2020关于教育的4项建议(表1)。因接受手术而造成造口的患者需要了解自己的造口类型、护理策略(如造口袋),以及造口对其生活方式的影响。6因此,这些患者需求超出了最初护理教育项目中可能教授的内容。Zimnicki和Pieper7调查了护士生,发现只有不到一半(47.8%)的护士生没有护理造口患者的经验。对于有护理造口患者经验的护士生而言,他们对排空造口袋最有信心。7Cross及其同事8的研究结果也支持未接受过专业造口教育的护理人员对排空造口袋比对其他造口护理技能更有信心。土耳其的Duruk和Uçar9以及中国的Li和同事10也表示,护理人员缺少护理造口患者的足够知识。据报告,当患者由接受过专业造口教育的护士进行护理时,其造口护理结果更佳。这包括西班牙的Coca及其同事,11日本的Chikubu和Oike,12以及英国的Jones的研究。13

40多年来,WCET®一直倡导对护士进行专业造口教育的重要性,旨在更好地满足患者及其家属的需求。6其他协会(如美国伤口造口和失禁护理协会;加拿大伤口、造口和失禁护理专科护士;以及英国造口护理护士协会)也都在倡导进行专业护理教育。建议的修改内容包括提供专科护士为造口患者及其家属提供适当护理所需的基于能力的课程以及技能和专业能力检查表。14-17循证实践要求专业医护人员了解新技术、技能和知识的最新情况;终身学习是必要的。

整体护理方面:文化和宗教

文献支持IOG 2020中与整体护理相关的三项高等级建议(表1),并证实了在护理造口患者时考虑这些建议的必要性。

造口会在不同领域对个人产生影响,如日常生活、整体生活质量、社会关系、工作、亲密关系和自尊。整体护理方法旨在认识和解决患者在生理、心理、社会学、精神和文化层面的需求,18尤其是当患者的情况复杂时。19因此,在实践中实施整体方法对于解决所有的潜在问题至关重要。20

有许多工具可用于评估患者的生活质量、自我护理调整、社会适应和/或心理状态。21,22 这些工具在护士做出临床决策时可提供重要信息,但临床判断始终是不可或缺的。因为整体护理是多维度的,使用各种方法将使护理造口患者的方法具有综合性和全球性。

世界卫生组织对健康23的定义在今天仍具有重要意义。一个人的出身、信仰、宗教、文化、性别和年龄会影响其对疾病的解释。24-26对于专业医护人员而言,理解这些影响及其对患者、家属和/或照护者的实际影响至关重要,因为这将为共同构建造口护理体系提供关键信息。

Larry Purnell博士的文化能力模型3,4可很容易地应用于造口护理之中。5它可以帮助护士为造口患者提供多元文化护理。整合行之有效的文化能力将改善患者、家属和专业医护人员之间的关系,27特别是在患者和/或家属认为造口难以处理的情况下。28

专科护士和非专科护士在患者、家属和照护者教育方面发挥着关键作用。29他们将逐步帮助支持特定技能的发展和个性化适应性策略的实施。护士的建议和支持可以减少与造口有关的并发症,13,30,31倾听和安抚患者的情绪将改善个人的自我护理。32

在提供造口护理期间,对《国际造口患者权利宪章》33 加以考虑将提高患者的生活质量,因为它支持赋予患者权力,并加强患者、家属、照护者和专业医护人员之间的伙伴关系。

IOG 2020的第6部分提供了关于造口护理的国际视角。由于纳入了来自22个国家的文稿,该版本比之前的版本更具包容性。2作者希望该版本能帮助提高医生技能,从而有助于世界各地的造口临床医生照顾来自其他文化、背景或信仰体系的患者,满足每例患者的需求。

术前护理和造口部位标记

如表1所示,有四项建议涉及术前护理和造口部位标记。文献强调了对即将接受造口手术的患者进行术前教育,其中包括术前部位标记。研究发现,在手术前标记造口部位的患者所出现的并发症较少。34,35

由于专科护士可能无法提供全天候服务,接受计划外/急诊手术的患者可能无法从术前教育和造口部位标记中获益。因此,文献支持对医生和非专科护士进行造口部位标记的培训。34-37Zimnicki36完成了一个针对非专科护士进行造口部位标记培训的质量改进项目。该项目显著增加了术前接受造口部位标记和教育的患者数量。36

造口部位标记是一项重要的技术和技能,不在本文详细描述的范围之内。主要原则包括在患者站立、坐下、屈曲和躺下时观察患者的腹部(图1)。37-41至少有两种技术可用于确定理想的腹部位置。42-52感兴趣者可查阅有关造口部位标记的参考文献42-60以及WCET®网络研讨会或口袋指南(www.wcetn.org)。52

图1 造口部位标记位置 ©2021 Ayello,经许可使用。

术后护理

IOG 2020列出了四项术后护理建议,以协助造口临床医生检测、预防或管理造口周围并发症,从而将任何造口周围并发症的影响降至最低(表1)。

表1 2020版WCET®国际造口指南建议

WCET® 国际造口指南推荐意见

1. 教育和实践范围

1.1 需经过专业培训才能有效地为造口患者及其家人提供护理。SOE= A

1.2 专业培训内容应设置基于胜任力的课程,包括教学和技能表现评估,可以通过模拟或情景教学。SOE= A-

1.3 通过持续的专业发展(包括各种策略/方法)来保持知识、技能和胜任力水平。SOE= A-

1.4 实践范围必须符合造口治疗师/造口/造口术护士或临床医师所在的国家/地区的法律法规。循证实践指南(地区,国家,国际)应被运用或适应。SOE= A

2. 整体方法

2.1 对患者/家庭的整体评估对于指导共同参与式护理至关重要。计划和实施应考虑个体、社会、经济和医疗环境因素 。SOE= A

2.2 造口治疗师/造口/造口术护士或临床医生需要考虑文化、宗教信仰和生活质量对实施造口手术患者(创建、改道或关闭)及其家人的影响。 SOE= A

2.3 考虑接受造口手术的患者/家庭应该共同参与讨论其对生活质量、身体形象和性的影响。SOE= A

3. 术前护理需求

3.1 无论择期和非择期手术,(当可能时)术前应由掌握相应技术的造口治疗师/造口/造口术护士或临床医生进行造口定位。SOE= A-

3.2 造口定位的位置应在腹直肌内,远离腹部疤痕、皱纹、皮肤褶皱或腰带处。SOE= A-

3.3 造口定位的位置应考虑患者的身体特征、生活方式、宗教和其他文化影响。SOE= B+

3.4 术前患者/家庭教育应包括手术过程的解释、术后造口/造口周围皮肤的自我护理,或对临时造口患者解释造口预期闭合的相关情况。SOE= A

4. 术后护理需求

4.1 使用经过验证的造口周围皮肤评估工具有助于对造口周围皮肤状态的标准化描述。SOE= A

4.2 造口底盘和耐用收集装置等产品应均配有安全的密封装置,以保护皮肤,防止容纳物流出。造口底盘或造口袋选择工具可能为选择提供帮助。 SOE= A

4.3 个人、家庭和造口治疗师/造口/造口术护士或临床医生需要认识和辨别常见造口和造口周围并发症的病因。现有的工具可以帮助识别和进行造口和造口周围皮肤状况的标准化术语描述。 SOE= A

4.4 个人、家庭和造口治疗师/造口/造口术护士或临床医生需要实施预防和护理计划,以解决潜在或现有的造口和造口周围并发症或造口术后闭合预期相关情况或并发症。SOE= A

©WCET® 2020, used with permission.

Many thanks to Julie Yajuan Weng, WCET® Education Committee Chairperson 2020-2024, for this Chinese translation.

Abbreviation: SOE, 证据强度.

从造口临床医生和造口患者的角度来看,造口手术后术后恢复的成功与否取决于多种因素。护理团队的所有成员(包括患者)必须提高对新造口形成、现有造口形状改变或造口闭合常见问题的预防或治疗策略的认识。识别和有效管理潜在或实际术后造口和造口周围皮肤并发症(PSC)的能力对造口患者61-63的健康、幸福感和独立性以及卫生资源管理具有内在的短期和长期影响。64-66

术后造口并发症可能会出现早期或晚期表现。早期并发症如皮肤黏膜分离、回缩、造口坏死、造口旁脓肿或皮炎可能在手术后30天内发生。晚期并发症包括造口旁疝(PH)和造口脱垂、回缩或狭窄。63,67,68

但最常见的术后并发症是PSC。69PSC的常见原因是渗漏、70,71术前无造口位置定位、35手术建造技术不佳、72装置不合适,以及装置佩戴时间长。71,73

常见的PSC包括急性和慢性刺激性接触性皮炎和过敏性接触性皮炎,前者是由于长期接触皮肤上的排泄物或尿液最终导致糜烂(图2)。评估腹部、造口、造口装置和所使用的附件以及患者护理造口和正确重新使用其装置的能力,对于确定渗漏原因至关重要。根据刺激或脱皮的严重程度,皮肤护理可能包括使用保护性果胶基粉末或糊剂、皮肤封闭剂(丙烯酸聚合物或氰基丙烯酸酯湿巾或喷雾),以及保护性皮肤屏障产品。为改善急性刺激性接触性皮炎和预防慢性刺激性接触性皮炎,可能也需要调整使用的装置类型和佩戴时间。61,70,74

图2 刺激性皮炎 ©2021 Chabal,经许可使用。

过敏性接触性皮炎是对在清洁过程中对涂抹在皮肤上的产品中的物质,或对在涂抹或取下装置前使用的皮肤保护产品,或对装置本身的一部分而产生的不良反应。74,75如果装置是过敏原或是使用过第二次皮肤护理产品的区域,则受损皮肤通常会显示出装置的形状。受损皮肤可能出现皮疹;发红、起泡、发痒或疼痛;或渗出含血液体(图3)。 为确定特定的病原体和/或评估用于获得造口周围安全密封的其他皮肤屏障产品的适用性,可能需要对距离受损皮肤和造口较远的小面积皮肤进行皮肤接触试验。70,75

图3 过敏性接触皮炎 ©2021 Chabal,经许可使用。

造口旁疝是一种潜在的并发症,也是导致PSC的原因。原因包括手术技术、造口大小和类型、腹围、年龄和医疗状况(如既往的疝和憩室炎液)。对外科医生进行培训,在手术中预防性地插入聚丙烯补片以及术后对患者进行教育可降低PH的发生率(图4)。68,76,77此外,医护人员必须评估和测量患者腹部的造口水平,以选择控制PH隆起程度所需的最合适的支撑服,防止进一步恶化,并使造口继续保持正常状况。78为处理造口大小发生的任何变化,使用中的造口装置/造口袋也需要经常重新评估。

图4 造口旁疝 ©2021 Chabal,经许可使用。

IOG 2020引用了许多造口临床医生可用来有效识别和分类PSC79,80,81并选择适当的皮肤屏障产品和装置管理PSC的工具。62,82

最后,为改善造口患者的术后生活质量,减少造口并发症和相关的再入院,以及加强跨专业的实践,在术后使用早期或强化恢复项目、83,84持续教育和出院后监测项目,68,85以及采用可用于咨询和远程咨询的远程医疗模式的重要性日益凸显。86,87

指南实施

为使临床指南能够为预期的患者人群带来积极的结果,需要在日常实践中采用拟议的建议。需要多种策略来促进指南的采用,88,89且应根据具体的临床环境审查和调整指南。90因此,我们需要事先考虑如何传播和实施指南。实施指南的潜在障碍可能包括缺乏资源,存在竞争性的健康议程,或人们认为造口护理是一个没有“拥护者”来倡导和促进实施的医学/护理附属专业,因此对其缺乏兴趣。最后,指南可能被认为规定性太强。IOG 2020中关于指南实施的部分提供了建议,读者可直接阅读完整指南以获取更多信息。

COVID-19对造口护理的影响

对IOG 2020证据的审查早于2019新型冠状病毒的出现。在大流行期间,有传闻称造口临床医生被重新分配到其他患者的护理工作中。这种情况的程度和影响还有待研究。同时,虚拟就诊可能为患者和医护人员提供一种替代现场护理的安全方式。91White及其同事92的一项研究报告了对新造口患者进行虚拟就诊的可行性;90%的患者认为这些就诊有助于管理造口。92但另一项研究发现,只有32%的受访者知道远程医疗是一个选择。93此外,71%的患者“认为[他们的问题]没有严重到需要寻求专业医护人员的帮助”,93但57%的患者报告称在大流行期间发生了一些造口周围皮肤问题。93报告的皮肤问题类型按降序排列为发红或皮疹(79%)、瘙痒(38%)、刺破皮肤(21%)、出血(19%)和其他问题(7%)。93

结论

IOG 2020旨在为临床医生提供一个循证框架,以此作为其实践的基础。IOG 2020的15项建议适用于资源丰富的国家(护士和专业医护人员接受过造口护理培训,使用制造的装置/造口袋),也适用于资源有限的国家(非专科护士、专业医护人员和非专业人员使用当地现有资源制造的造口设备控制造口渗出液)。需要专业知识来帮助造口患者学习如何使用、排空和更换其装置/造口袋,但造口患者生活中遇到的问题不仅限于此,因此需要考虑患者的所有方面。

整体患者护理应是个性化的,涉及饮食、日常生活活动、性生活、祈祷、工作、药物、身体形象和其他以患者为中心的问题。术前造口定位与更好的术后结果有关。对PSC的早期识别和干预措施需要充分的教学,以及对何时寻求专业帮助的认识。拥有造口护理专业知识的护士可以提高造口患者的生活质量,包括出现PSC的患者。95作者希望IOG 2020能改善这一人群的护理结果和康复情况。

实践要点

• 由拥有专业造口知识的专业医护人员护理的患者会有更佳的护理结果。

• 有临床工具可帮助进行造口周围皮肤评估和满足装置要求。

• 术前和术后需要整体和个性化的患者和家属教育。

• 接受术前造口定位的患者所出现的并发症较少。

• 最常见的PSC是渗漏导致的刺激性皮炎。

• 远程医疗和远程咨询可能有助于为造口患者提供辅助指导。

Author(s)

Laurent O. Chabal*

BSc (CBP), RN, OncPall (Cert), Dip (WH), ET, EAWT

Specialised Stoma Nurse, Ensemble Hospitalier de la Côte—Morges’ Hospital; Lecturer, Geneva School of Health Sciences, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Western Switzerland; and President Elect, WCET® 2020-2022

Jennifer L. Prentice

PhD, RN, STN, FAWMA

WCET® Journal Editor; Nurse Specialist Wound Skin Ostomy Service Hall & Prior Health and Aged Care Group, Perth, Western Australia

Elizabeth A. Ayello

PhD, MS, BSN, ETN, RN, CWON, MAPCWA, FAAN

Co-Editor in Chief, Advances in Skin and Wound Care;

President, Ayello, Harris & Associates, Copake, New York;

WCET® President, 2018-2022; WCET® Executive Journal Editor Emerita, Perth, Western Australia; and Faculty Emerita, Excelsior College School of Nursing, Albany, New York

* Corresponding author

References

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® International Ostomy Guideline. Chabal LO, Prentice JL, Ayello EA, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET®; 2020.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® International Ostomy Guideline. Zulkowski K, Ayello EA, Stelton S, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET®; 2014.

- Purnell L. Transcultural health care: a culturally competent approach. Philadelphia: F A Davis Co; 2013.

- Purnell L. Guide to culturally competent health care. Philadelphia: F A Davis Co; 2014.

- Purnell L. The Purnell Model applied to ostomy and wound care. WCET J 2014;34(3):11-8.

- Gill-Thompson SJ. Forward to second edition. In: Erwin-Toth P, Krasner DL, eds. Enterostomal Therapy Nursing. Growth & Evolution of a Nursing Specialty Worldwide. A Festschrift for Norma N. Gill-Thompson ET. 2nd ed. Perth, Western Australia: Cambridge Publishing; 2020;10-1.

- Zimnicki K, Pieper B. Assessment of prelicensure undergraduate baccalaureate nursing students: ostomy knowledge, skill experiences, and confidence in care. Ostomy Wound Manage 2018;64(8):35-42.

- Cross HH, Roe CA, Wang D. Staff nurse confidence in their skills and knowledge and barriers to caring for patients with ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41(6):560-5.

- Duruk N, Uçar H. Staff nurses’ knowledge and perceived responsibilities for delivering care to patients with intestinal ostomies. A cross-sectional study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;40(6):618-22.

- Li, Deng B, Xu L, Song X, Li X. Practice and training needs of staff nurses caring for patients with intestinal ostomies in primary and secondary hospital in China. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(5):408-12.

- Coca C, Fernández de Larrinoa I, Serrano R, García-Llana H. The impact of specialty practice nursing care on health-related quality of life in persons with ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(3):257-63.

- Chikubu M, Oike M. Wound, ostomy and continence nurses competency model: a qualitative study in Japan. J Nurs Healthc 2017;2(1):1-7.

- Jones S. Value of the Nurse Led Stoma Care Clinic. Cwm Taf Health Board, NHS Wales. 2015. www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/research-and-innovation/innovation-in-nursing/~/-/media/b6cd4703028a40809fa99e5a80b2fba6.ashx. Last accessed March 4, 2021.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. ETNEP/REP Recognition Process Guideline. 2017. https://wocet.memberclicks.net/assets/Education/ETNEP-REP/ETNEP%20REP%20Guidelines%20Dec%202017.pdf. Last accessed March 4, 2021.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. WCET Checklist for Stoma REP Content. 2020. www.wcetn.org/assets/Education/wcet-rep%20stoma%20care%20checklist-feb%2008.pdf. Last accessed March 4, 2021.

- Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, Guideline Development Task Force. WOCN Society clinical guideline: management of the adult patient with a fecal or urinary ostomy-an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2018;45(1):50-8.

- Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society Task Force. Wound, ostomy, and continence nursing: scope and standards of WOC practice, 2nd edition: an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2018;45(4):369-87.

- Wallace S. The Importance of holistic assessment—a nursing student perspective. Nuritinga 2013;12:24-30.

- Perez C. The importance of a holistic approach to stoma care: a case review. WCET J 2019;39(1):23-32.

- The importance of holistic nursing care: how to completely care for your patients. Practical Nursing. October 2020. www.practicalnursing.org/importance-holistic-nursing-care-how-completely-care-patients. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Knowles SR, Tribbick D, Connell WR, Castle D, Salzberg M, Kamm MA. Exploration of health status, illness perceptions, coping strategies, psychological morbidity, and quality of life in individuals with fecal ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(1):69-73.

- Vural F, Harputlu D, Karayurt O, et al. The impact of an ostomy on the sexual lives of persons with stomas—a phenomenological study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(4):381–4.

- World Health Organization. What is the WHO definition of health? www.who.int/about/who-we-are/frequently-asked-questions. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Baldwin CM, Grant M, Wendel C, et al. Gender differences in sleep disruption and fatigue on quality of life among persons with ostomies. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5(4):335-43.

- World Health Organization. Gender, equity and human rights. 2020. www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/indigenous-peoples/en. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Forest-Lalande L. Best-practice for stoma care in children and teenagers. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2019;17(S5):S12-3.

- Qader SAA, King ML. Transcultural adaptation of best practice guidelines for ostomy care: pointers and pitfalls. Middle East J Nurs 2015;9(2):3-12.

- Iqbal F, Kujan O, Bowley DM, Keighley MRB, Vaizey CJ. Quality of life after ostomy surgery in Muslim patients—a systematic review of the literature and suggestions for clinical practice. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(4):385-91.

- Merandy K. Factors related to adaptation to cystectomy with urinary diversion. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(5):499-508.

- de Gouveia Santos VLC, da Silva Augusto F, Gomboski G. Health-related quality of life in persons with ostomies managed in an outpatient care setting. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(2):158-64.

- Ercolano E, Grant M, McCorkle R, et al. Applying the chronic care model to support ostomy self-management: implications for oncology nursing practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2016;20(3):269-74.

- Xu FF, Yu Wh, Yu M, Wang SQ, Zhou GH. The correlation between stigma and adjustment in patients with a permanent colostomy in the midlands of China. WCET J 2019;39(1):24-39.

- International Ostomy Association. Charter of Ostomates Rights. www.ostomyinternational.org/about-us/charter.html. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Watson AJM, Nicol L, Donaldson S, Fraser C, Silversides A. Complications of stomas: their aetiology and management. Br J Community Nurs 2013;18(3):111-2, 114, 116.

- Baykara ZG, Demir SG, Ayise Karadag A, et al. A multicenter, retrospective study to evaluate the effect of preoperative stoma site marking on stomal and peristomal complications. Ostomy Wound Manage 2014;60(5):16-26.

- Zimnicki KM. Preoperative teaching and stoma marking in an inpatient population: a quality improvement process using a FOCUS-Plan-Do-Check-Act Model. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(2):165-9.

- WOCN Committee Members, ASCRS Committee Members. ASCRS and WOCN joint position statement on the value of preoperative stoma marking for patients undergoing fecal ostomy surgery. JWOCN 2007;34(6):627-8.

- Salvadalena G, Hendren S, McKenna L, et al. WOCN Society and ASCRS position statement on preoperative stoma site marking for patients undergoing colostomy or ileostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(3):249-52.

- Salvadalena G, Hendren S, McKenna L, et al. WOCN Society and AUA position statement on preoperative stoma site marking for patients undergoing urostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(3):253-6.

- Brooke J, El-GHaname A, Napier K, Sommerey L. Executive summary: Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada (NSWOCC) nursing best practice recommendations. Enterocutaneous fistula and enteroatmospheric fistula. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(4):306-8.

- Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada. Nursing Best Practice Recommendations: Enterocutaneous Fistulas (ECF) and Enteroatmospheric Fistulas (EAF). 2nd ed. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada; 2018.

- Serrano JLC, Manzanares EG, Rodriguez SL, et al. Nursing intervention: stoma marking. WCET J 2016;36(1):17-24.

- Fingren J, Lindholm E, Petersén C, Hallén AM, Carlsson E. A prospective, explorative study to assess adjustment 1 year after ostomy surgery among Swedish patients. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;64(6):12-22.

- Rust J. Complications arising from poor stoma siting. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2011;9(5):17-22.

- Watson JDB, Aden JK, Engel JE, Rasmussen TE, Glasgow SC. Risk factors for colostomy in military colorectal trauma: a review of 867 patients. Surgery 2014;155(6):1052-61.

- Banks N, Razor B. Preoperative stoma site assessment and marking. Am J Nurs 2003;103(3):64A-64C, 64E.

- Kozell, K, Frecea M, Thomas JT. Preoperative ostomy education and stoma site marking. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41(3):206-7.

- Readding LA. Stoma siting: what the community nurse needs to know. Br J Community Nurs 2003;8(11):502-11.

- Cronin E. Stoma siting: why and how to mark the abdomen in preparation for surgery. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2014;12(3):12-9.

- Chandler P, Carpenter J. Motivational interviewing: examining its role when siting patients for stoma surgery. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2015;13(9):25-30.

- Pengelly S, Reader J, Jones A, Roper K, Douie WJ, Lambert AW. Methods for siting emergency stomas in the absence of a stoma therapist. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2014;96:216-8.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. Guide to Stoma Site Marking. Crawshaw A, Ayello EA, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET; 2018.

- Mahjoubi B, Goodarzi K, Mohannad-Sadeghi H. Quality of life in stoma patients: appropriate and inappropriate stoma sites. World J Surg 2009;34:147-52.

- Person B, Ifargan R, Lachter J, Duek SD, Kluger Y, Assalia A. The impact of preoperative stoma site marking on the incidence of complications, quality of life, and patient’s independence. Dis Colon Rect 2012;55(7):783-7.

- American Society of Colorectal Surgeons Committee, Wound Ostomy Continence Nurses Society® Committee. ASCRS and WOCN® joint position statement on the value of preoperative stoma marking for patients undergoing fecal ostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2007;34(6):627-8.

- AUA and WOCN® Society joint position statement on the value of preoperative stoma marking for patients undergoing creation of an incontinent urostomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009;36(3):267-8.

- Cronin E. What the patient needs to know before stoma siting: an overview. Br J Nurs 2012;21(22):1304, 1306-8.

- Millan M, Tegido M, Biondo S, Garcia-Granero E. Preoperative stoma siting and education by stomatherapists of colorectal cancer patients: a descriptive study in twelve Spanish colorectal surgical units. Colorectal Dis 2010;12(7 Online):e88-92.

- Batalla MGA. Patient factors, preoperative nursing Interventions, and quality of life of a new Filipino ostomates. WCET J 2016;36(3):30-8.

- Danielsen AK, Burcharth J, Rosenberg J. Patient education has a positive effect in patients with a stoma: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 2013;15(6):e276-83.

- Stelton S, Zulkowski K, Ayello EA. Practice implications for peristomal skin assessment and care from the 2014 World Council of Enterostomal Therapists International Ostomy Guideline. Adv Skin Wound Care 2015;28(6):275-84.

- Colwell JC, Bain KA, Hansen AS, Droste W, Vendelbo G, James-Reid S. International consensus results. Development of practice guidelines for assessment of peristomal body and stoma profiles, patient engagement, and patient follow-up. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(6):497-504.

- Maydick-Youngberg D. A descriptive study to explore the effect of peristomal skin complications on quality of life of adults with a permanent ostomy. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(5):10-23.

- Nichols TR, Inglese GW. The burden of peristomal skin complications on an ostomy population as assessed by health utility and their physical component: summary of the SF-36v2®. Value Health 2018;21(1):89-94.

- Neil N, Inglese G, Manson A, Townshend A. A cost-utility model of care for peristomal skin complications. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;34(1):62.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad BS, Inglese G, Eaves D, Oster G. Risk and economic burden of peristomal skin complications following ostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(2):143-9.

- Koc U, Karaman K, Gomceli I, et al. A retrospective analysis of factors affecting early stoma complications. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(1):28-32.

- Hendren S, Hammond K, Glasgow SC, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for ostomy surgery. J Dis Colon Rectum 2015;58:375-87.

- Roveron G. An analysis of the condition of the peristomal skin and quality of life in ostomates before and after using ostomy pouches with manuka honey. WCET J 2017;37(4):22-5.

- Stelton S. Stoma and peristomal skin care: a clinical review. Am J Nurs 2019;119(6):38-45.

- Recalla S, English K, Nazarali R, Mayo S, Miller D, Gray M. Ostomy care and management a systematic review. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;40(5):489-500.

- Carlsson E, Fingren J, Hallen A-M, Petersen C, Lindholm E. The prevalence of ostomy-related complications 1 year after ostomy surgery: a prospective, descriptive, clinical study. Ostomy Wound Manage 2016;62(10):34-48.

- Steinhagen E, Colwell J, Cannon LM. Intestinal stomas—postoperative stoma care and peristomal skin complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2017;30(3):184-92.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. WCET Ostomy Pocket Guide: Stoma and Peristomal Problem Solving. Ayello EA, Stelton S, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET, 2016.

- Cressey BD, Belum VR, Scheinman P, et al. Stoma care products represent a common and previously underreported source of peristomal contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 2017;76(1):27-33.

- Tabar F, Babazadeh S, Fasangari Z, Purnell P. Management of severely damaged peristomal skin due to MARSI. WCET J 2017;37(1):18.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad BS, Inglese G, Lamerato L, Oster G. Clinical and economic burden of peristomal skin complications in patients with recent ostomies. J Wound, Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(4):350.

- Association Stoma Care Nurses. ASCN Stoma Care National Clinical Guidelines. London, England: ASCN UK; 2016.

- Herlufsen P, Olsen AG, Carlsen B, et al. Study of peristomal skin disorders in patients with permanent stomas. Br J Nurs 2006;15(16):854-62.

- Ay A, Bulut H. Assessing the validity and reliability of the peristomal skin lesion assessment instrument adapted for use in Turkey. Ostomy Wound Manage 2015;61(8):26-34.

- Runkel N, Droste W, Reith B, et al. LSD score. A new classification system for peristomal skin lesions. Chirurg 2016;87:144-50.

- Buckle N. The dilemma of choice: introduction to a stoma assessment tool. GastroIntestinal Nurs 2013;11(4):26-32.

- Miller D, Pearsall E, Johnston D, et al. Executive summary: enhanced recovery after surgery best practice guideline for care of patients with a fecal diversion. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(1):74-7.

- Hardiman KM, Reames CD, McLeod MC, Regenbogen SE. A patient-autonomy-centered self-care checklist reduces hospital readmissions after ileostomy creation. Surgery 2016;160(5):1302-8.

- Harputlu D, Özsoy SA. A prospective, experimental study to assess the effectiveness of home care nursing on the healing of peristomal skin complications and quality of life. Ostomy Wound Manage 2018;64(10):18-30.

- Iraqi Parchami M, Ahmadi Z. Effect of telephone counseling (telenursing) on the quality of life of patients with colostomy. JCCNC 2016;2(2):123-30.

- Xiaorong H. Mobile internet application to enhance accessibility of enterostomal therapists in China: a platform for home care. WCET J 2016;36(2):35-8.

- Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM. Selecting, presenting, and delivering clinical guidelines: are there any “magic bullets”. Med J Aust 2004;180(6 Suppl):S52-4.

- Rauh S, Arnold D, Braga S, et al. Challenge of implementing clinical practice guidelines. Getting ESMO’s guidelines even closer to the bedside: introducing the ESMO Practising Oncologists’ checklists and knowledge and practice questions. ESMO Open 2018;3:e000385.

- Fletcher J, Kopp P. Relating guidelines and evidence to practice. Prof Nurse 2001;16:1055-9.

- Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa P, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. JAMIA 2020;27(7):1132-5.

- White T, Watts P, Morris M, Moss J. Virtual postoperative visits for new ostomates. CIN 2019;37(2):73-9.

- Spencer K, Haddad S, Malanddrino R. COVID-19: impact on ostomy and continence care. WCET J 2020;40(4):18-22.

- Russell S. Parastomal hernia: improving quality of life, restoring confidence and reducing fear. The importance of the role of the stoma nurse specialist. WCET J 2020;40(4):36-9.