Volume 41 Number 3

Complexity in care for an ostomate with surgical dehiscence after herniorrhaphy: a case study

Iraktânia Vitorino Diniz, Isabelle Pereira da Silva, Lorena Brito do O’, Isabelle Katherinne Fernandes Costa and Maria Júlia Guimarães Oliveira Soares

Keywords ostomy, nursing care, herniorrhaphy, postoperative complications, stomal therapist

For referencing Diniz IV et al. Complexity in care for an ostomate with surgical dehiscence after herniorrhaphy: a case study. WCET® Journal 2021;41(3):22-26

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.3.22-26

Submitted 13 December 2020

Accepted Accepted 18 July 2021

Abstract

Performing stoma surgery is often complex for the surgeon to undertake especially when the patient has pre-existing complications. Postoperatively, peristomal complications affect the adherence of the collection bag, and impair the self-care and wellbeing of the person with an ostomy, which increases the need for professionals trained in the management of peristomal skin complications. In addition, health professionals need to be able to educate the ostomate in self-care of the stoma or support them in managing peristomal complications. The aim of this case study is to report the management of a complex clinical case of a patient postoperatively following a herniorrhaphy and construction of a colostomy that resulted in surgical dehiscence and ensuing peristomal complications. The case study also highlights the clinical care advocated by the stomal therapist to manage these complications.

Introduction

About 100,000 surgical procedures to create stomas are performed each year in the United States of America (USA)1 and it is estimated that approximately 1 million people in the USA have an ostomy2. In Brazil, the data on ostomy surgery and stoma creation are uncertain; however, a high number of cases are estimated due to the annual increase in colorectal cancer, the main cause for surgery3.

Surgeons who perform ostomy surgery face challenges associated with modifying intestinal structures to create ileostomies or colostomies that alter intestinal transit times and thereby consistency of faecal output. Often there are associated complications in forming the stoma such as an obese abdomen4. Postoperatively, the primary problems reported are stoma and peristomal complications which can occur immediately or can be delayed complications; both reduce an ostomate’s quality of life5.

A study that analysed the incidence of complications after ostomy surgery found that 28.4% of participants developed some complication, and that the most common were superficial mucocutaneous separation (19.5%) and stoma retraction (3.2%)6. The syndrome of post-surgical complications in another study was 33.3%, of which 13.6% had retraction, 10.6% had parastomal hernia, and 28.8% had complications arising from the stoma – dermatitis (21.2%) and mucosal oedema (4.5%)7. Peristomal complications are the main complications that affect the collection bag’s adherence to the skin and impair the self-care and wellbeing of the ostomate since these can lead to leakage, irritant dermatitis, and other complications such as infection.

Thus, care both in the perioperative and postoperative rehabilitation processes are essential for the ostomate to adjust to living life with a stoma and achieve independence in self-care where possible. In this context, health professionals have an important role in the treatment of complications and in the health education process5.

The study complied with ethical standards in research, with approval of the project by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Paraíba, Brazil, under article 2,562,857. The participant signed the terms to consent to participate after clarifying the objectives and procedures of the case study.

The aim of this case study is to report the complex clinical case of a patient in the postoperative period following herniorrhaphy plus colostomy, and the management strategies of the stomal therapist.

Case Report

Presenting problem

The patient reported here was a female patient, aged 56 years old who was both obese and suffering from diabetes. In July 2018 she was admitted to the hospital complaining of severe abdominal pain with possible intestinal obstruction. On further examination, the laboratory tests and tomography showed a white blood cell count of 17,650, and a diagnosis of strangled inguinal hernia. She underwent an emergency exploratory laparotomy, herniorrhaphy, enterotomy and colostomy.

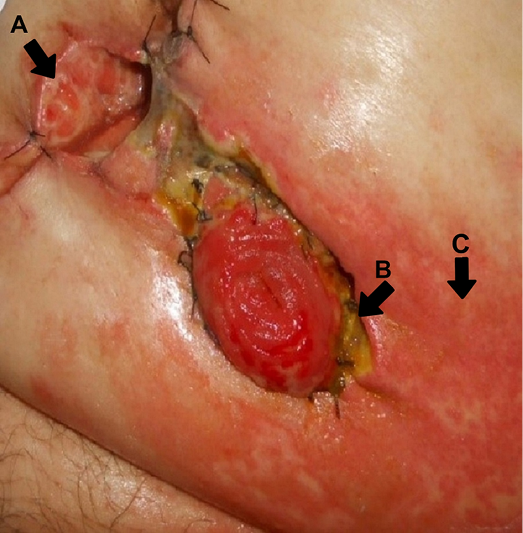

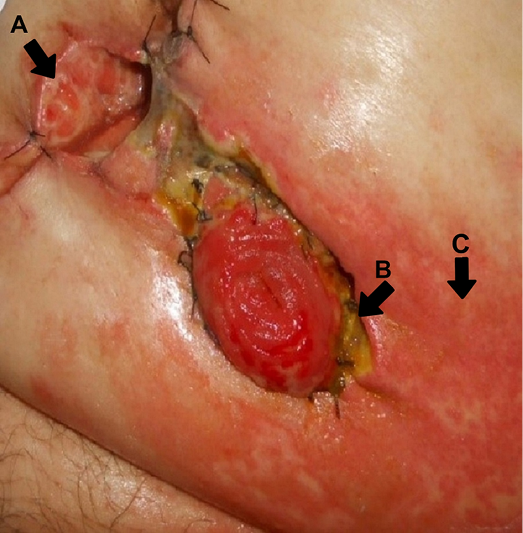

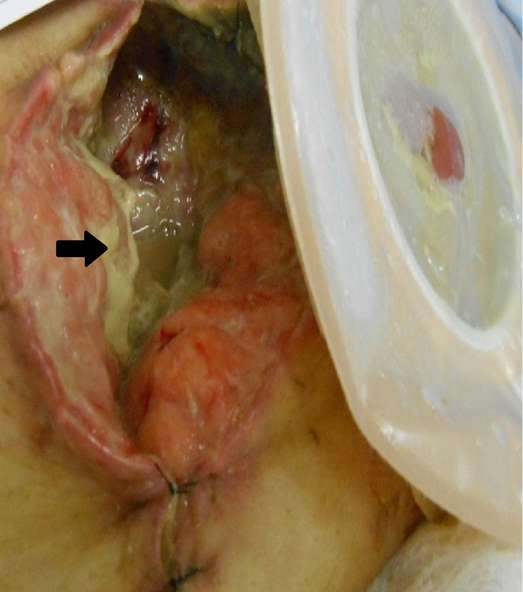

On 15 July 2018, Day 3 postoperatively, the patient developed purulent drainage from an opening in the middle of the surgical incision adjacent to the colostomy stoma. The abdomen was also distended, indicating the need to remove alternate sutures below the level of the umbilicus to alleviate the tension on the suture line adjacent to and to the right of the suture line. Suture removal subsequently led to the development of surgical dehiscence (Figure 1A). In addition, mucocutaneous detachment of the stoma from the abdomen occurred from the medial edge of the suture line and upper margins of the stoma (Figure 1B). Further, extensive peristomal dermatitis occurred which spread outward in a 10cm radius from the right side of the colostomy (Figure 1C). The peristomal dermatitis was caused by the semi-liquid stool from the colostomy coming into contact with intact skin due to poor adhesion of the ostomy appliance due to leakage of stool from around the stoma as a result of the combined effects of the surgical dehiscence and mucocutaneous separation.

Figure 1. A: surgical wound dehiscence; B: mucocutaneous detachment of the stoma; C: peristomal dermatitis

Stomal therapy and nursing interventions

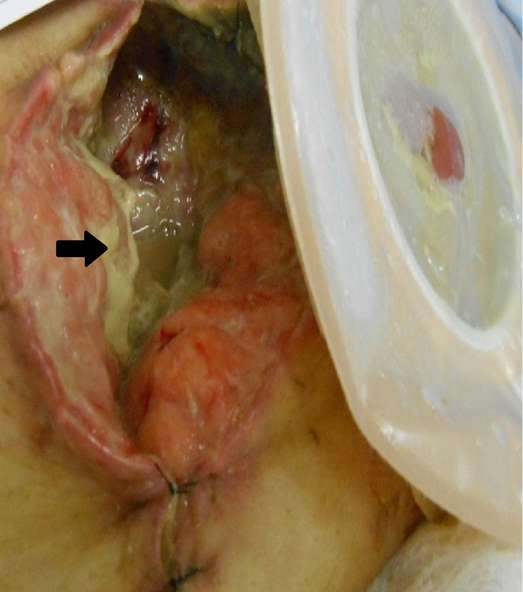

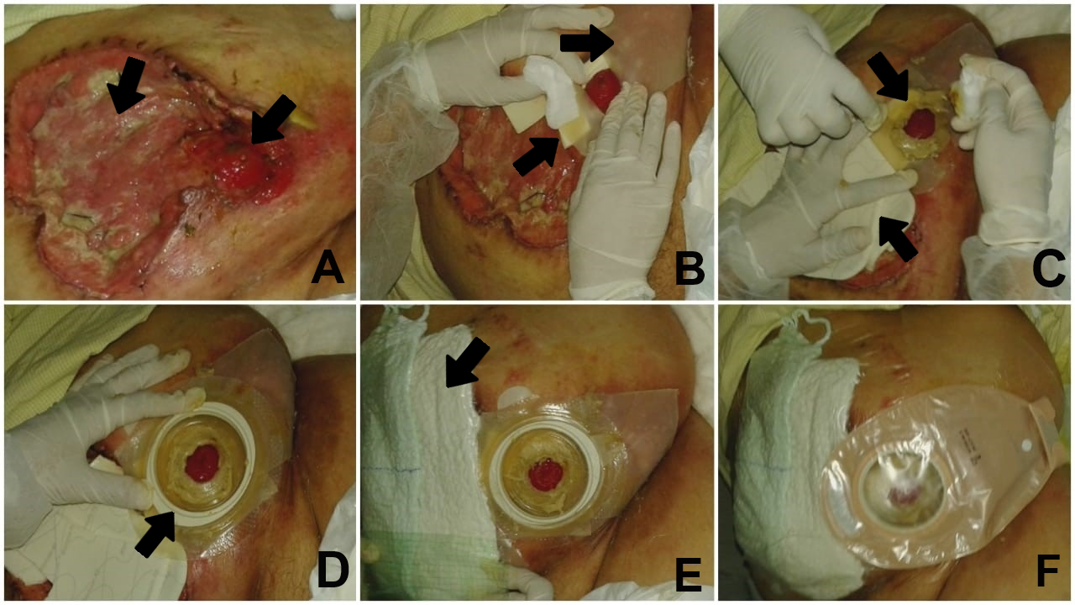

Wound, skin and stoma hygiene were performed with 0.9% saline solution. To manage and facilitate repair of the surgical wound dehiscence a calcium alginate was inserted into the wound bed. A protective piece of hydrocolloid sheet was placed over the calcium alginate and areas of dermatitis to provide a stable base upon which to apply the base plate (or flange) of a 2‑piece colostomy appliance. After 2 days, the dressing and colostomy appliance needed to be removed due to further wound dehiscence, wound necrosis and subsequent leakage (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Surgical dehiscence with presence of liquefactive necrosis and fibrin in the wound

On 17 July 2018, Day 5 postoperatively, the area of surgical dehiscence had expanded, measuring 8x7x5cm with the presence of infection and purulent exudate (Figure 2).This required a change in management strategy. In this case, the stomal therapist advocated the use of a hydropolymer dressing with silver (silver dressing) for antimicrobial control and absorption of exudate. The silver dressing was placed in the wound cavity. To ensure the stoma was isolated from the wound and to provide a good seal around the stoma to prevent leakage, stomahesive powder was applied to the areas of wet dermatitis proximal to the stoma. Stomahesive paste and hydrocolloid strips were used to fill in and cover wound beds created by the mucocutaneous separations and mould around the stoma to form a dry surface on which to place a convex base plate (2‑piece colostomy bag system) to further assist with stoma retraction; this would also encourage wound healing.

Due to the patient’s obesity and abdominal distension, it was difficult to secure adherence of the ostomy appliance, and on 20 July 2018, Day 7 postoperatively, the degree of incisional surgical dehiscence markedly increased, measuring 27x18x4cm. Within the wound cavity, not only was there obvious drainage of faecal fluid, there was opaque fibrinous tissue, with areas of liquefaction necrosis averaging 30% of the wound’s surface (Figure 2). To cope with physical changes to the abdominal wound and stoma, amendments to the dressing regimen were made as follows.

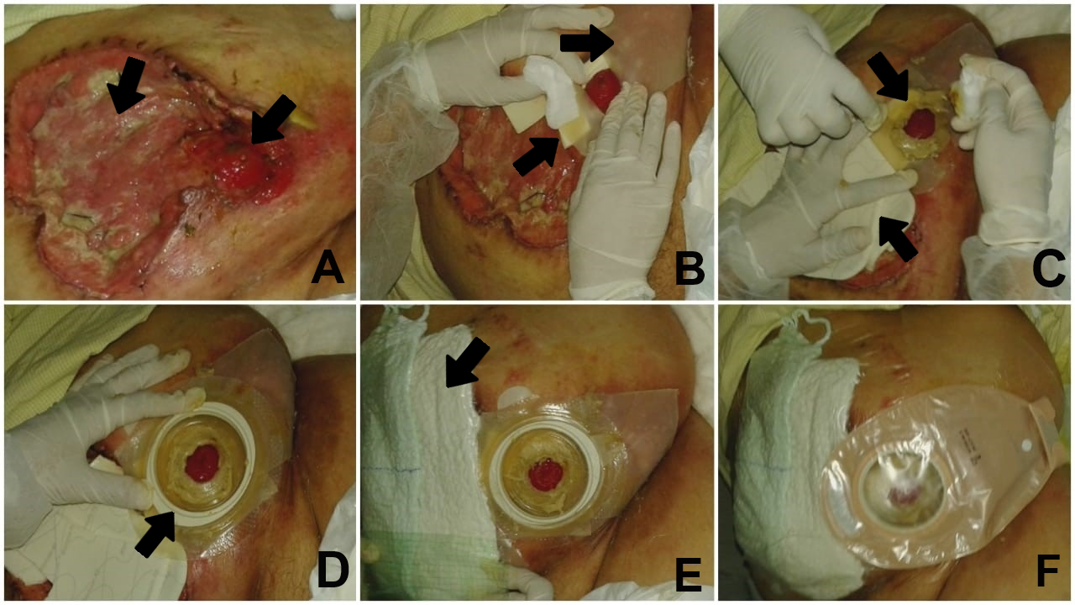

The wound was cleaned with 0.9% saline and 0.2% polyhexanide because, in the hospital in question, it is routine to use 0.9% saline solution and polyhexanide solution for cleaning. Saline solution was used to clean and remove excess dirt and the polyhexanide solution to clean a wound area due to its antiseptic properties. After cleaning, excess fluid was irrigated from the wound cavity using a number 8 nelaton catheter and 10cc syringe. To absorb wound exudate, the calcium alginate was placed as the primary dressing or contact layer in all areas of the surgical wound dehiscence wound bed, including all entrances to any sinus tracts/tunnels on view. The secondary dressing used for antimicrobial control was a hydropolymer with non-adhesive silver. Finally, a tertiary coverage of gauze combine was applied and externally fixaed with a polyurethane film (Figure 3 A–F).

Figure 3. A: ostomy within the cavity of surgical dehiscence; B: isolation of the ostomy using protective sheets and hydrocolloid strips; C: use of stomahesive paste around the stoma and calcium alginate in the wound cavity; D: application of the base plate; E: secondary dressing with silver foam and tertiary dressing with gauze combine and polyurethane film; F: completed dressing

The above wound dressing regimen was agreed upon by a multidisciplinary team including the responsible surgeon, the advising stomal therapist and nursing staff. The dressing was undertaken by the stomal therapist or nursing staff and nurse technicians. In addition to the wound care provided, it was necessary to continue to isolate the colostomy and peristomal skin complications present. Therefore, the colostomy was isolated by reconstructing the peristomal area with hydrocolloid strips and the ostomy paste. To further cover and protect the area of peristomal dermatitis from faecal fluid, a 20x20cm stomahesive sheet was used, in which an opening for the stoma was cut out and fixed around the stoma. A drainable transparent 2‑piece ostomy appliance with a convex base was applied over the protective sheet.

The patient was followed up for another 15 days. Although showing good evidence of wound healing and continued adherence of the wound dressings and ostomy appliance, the patient unfortunately died on 5 August 2018 due to her comorbid conditions and sepsis.

Discussion

In this case study, following emergency surgery the patient presented with suppuration from the suture line on Day 3 postoperatively. Post-removal of several abdominal sutures, the abdominal wound further dehisced along with simultaneous mucocutaneous separation of the stoma. These complications are deemed early surgical complications, all of which may occur due to tissue tension and comorbidities that impair healing, as well as due to infectious processes1.

Regarding emergency abdominal surgery, a higher prevalence of complications in the early postoperative period (36–66%), especially surgery involving construction of a stoma, are described. The expertise of the surgeon in creating a stoma is also a factor8. Surgical site infection, peristomal dermatitis and peristomal hernia are the main complications9–13.

It is also worth highlighting that diabetes and obesity as important factors related to mucocutaneous detachment and surgical dehiscence6. Obesity is a factor associated with difficult stoma construction and delayed postoperative recovery due to the challenges of resecting sufficient bowel to exteriorise the bowel through the abdominal wall to create a stoma. Obese individuals are more susceptible to wound dehiscence, surgical site infection and delayed wound healing due to raised intra-abdominal pressure, reduced perfusion of the tissues, and chronic inflammation of white adipose tissue that weakens tensile strength of the skin8,14,15. The association between diabetes and delayed wound healing are also well documented. All phases of wound healing are affected by diabetes, with prolonged inflammation thought to impede maturation of granulation tissue and the development of tensile strength within a wound arising from impaired blood vessels and resultant ischaemia1,16.

Post-surgery, peristomal skin conditions are the most common problem, varying from 10–70% of the cases17,18. Peristomal dermatitis can occur early or later in life around the skin of people with ostomies. This complication generates suffering, pain and difficulty in self-care, particularly where there is inadequate access to ostomy appliances and adjuvant skin care products19. The ostomy appliance and dressing remained intact without any leakage for 3 days (72 hours). This was a positive result and reduced secondary injury in continuously removing and replacing the dressing and ostomy appliance.

A comprehensive nursing assessment of patients in the peri and postoperative phases assists with identifying those patients at risk of compromised surgical recovery. This involves assessing the patient’s abdomen for shape, the integrity or stability of the surgical wound, the location and construction of the stoma, and the presence of scars that may minimise complications.

Assigning a nursing diagnosis facilitates implementation of nursing interventions specific to the individual patient and their care needs20. In cases where complications do occur, such as that described within our case study, prompt stomal therapy nursing interventions are necessary to manage the skin deficits that have occurred, with a variety of ostomy and skin accessory products available to the stomal therapist such as such as adhesive pastes and powder for ostomies, ostomy skin barriers and seals, as well as choosing an appropriate type of ostomy base plate and bag1. In addition, nurses need to understand the principles of caring for people with complex wounds and stomas and the importance of a multidisciplinary health team involvement; more nurses need to be skilled in this field of expertise21–23. There are also guidelines that address the importance of peristomal skin care, stoma care and appliance selection and how to prevent and manage early and late post-surgical ostomy complications. Adherence to advice within clinical practice guidelines on the aforementioned factors improves patient assessment, assists with early collaborative interventions and management of complications and, overall, improves patients’ quality of life and health service outcomes13,17,24.

Conclusion

The patient discussed here presented with postoperative complications of surgical dehiscence, mucocutaneous detachment of the stoma, and peristomal dermatitis following a herniorrhaphy and colostomy formation. These complications required the creative strategies of the stomal therapist to provide complex wound and ostomy care that involved the correct application and use of ostomy equipment and skin care accessories to minimise risk of wound contamination from faecal fluid, optimise the wound healing processes, and maintain patient comfort.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

疝修补术后出现手术伤口裂开的造口患者护理复杂性:病例研究

Iraktânia Vitorino Diniz, Isabelle Pereira da Silva, Lorena Brito do O’, Isabelle Katherinne Fernandes Costa and Maria Júlia Guimarães Oliveira Soares

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.3.22-26

摘要

对于外科医生来说,尤其是当患者有预先存在的并发症时,造口手术通常较为复杂。术后,造口周围并发症会影响造口袋的附着力,妨碍造口患者的自我护理和健康,由此增加了对接受过造口周围皮肤并发症管理培训的专业人员的需求。此外,医疗保健专业人员需要能够教授造口患者自我护理造口,或帮助他们处理造口周围并发症。本病例研究的目的在于报告一个复杂的临床病例,该病例在疝修补术和结肠造口术后导致手术伤口裂开和继发性造口周围并发症。本病例研究还强调了造口治疗师提倡的临床护理方式,以治疗这些并发症。

引言

在美国(USA)1,每年进行约10万例造口手术,据估计,USA约有100万人拥有造口2。在巴西,造口手术和造口产生的数据不明确;但由于结肠直肠癌发生率(造口术的主要原因)每年都在增加,估计病例数量较高3。

改变肠道结构以建立回肠造口或结肠造口是造口术外科医生面临的一项挑战,这些造口手术可改变肠道运输时间,从而保持排便一致性。通常来说,例如在肥胖腹部形成造口,会出现相关并发症4。术后,报告的主要问题是造口和造口周围并发症,这些并发症可当即发生,也可延迟发生;两者都会降低造口患者的生活质量5。

一项分析造口手术后并发症发生率的研究发现,28.4%的受试者出现了一些并发症,最常见的是表面皮肤粘膜分离(19.5%)和造口回缩(3.2%)6。另一项研究的术后并发症综合征为 33.3%,其中13.6%有回缩,10.6%有造口旁疝,28.8%有造口并发症-皮炎(21.2%)和粘膜水肿(4.5%)7。造口周围并发症是影响造口袋对皮肤的粘附并妨碍造口患者的自我护理和健康的主要并发症,因为这些会导致渗漏、刺激性皮炎和其他并发症,例如感染。

因此,围手术期和术后康复过程中的护理对于造口患者适应有造口的生活并在可能的情况下实现自我护理的独立性至关重要。在这种情况下,医疗保健专业人员在并发症的治疗和健康教育过程中发挥着重要作用5。

该研究符合研究道德标准,经巴西帕拉伊巴联邦大学研究伦理委员会根据第2,562,857条批准。受试者在知悉病例研究的目的和程序后签署了知情同意书。

本病例研究的目的是报告疝修补联合结肠造口术后患者的复杂临床病例情况,以及造口治疗师的治疗策略。

病例报告

患者主诉

本文报告的患者是一名女性,56岁,肥胖,患有糖尿病。2018年7月,她因严重腹痛和潜在肠梗阻入院。进一步检查后,实验室检查和断层扫描显示白细胞计数为17,650,诊断为绞窄性腹股沟疝。她接受了紧急剖腹探查术、疝修补术、肠切开术和结肠造口术。

2018年7月15日,即术后第3天,患者从邻近结肠造口术的手术切口中间的开口处出现脓性液溢出。腹部也出现肿胀,表明需要去除脐水平以下的备用缝合线,以减轻缝合线附近和右侧缝合线上的张力。随后,缝线拆除导致手术伤口裂开(图1A)。此外,缝合线的内侧边缘和造口的上缘发生了造口与腹部的皮肤粘膜脱离(图1B)。此外,发生了大面积造口周围皮炎,从结肠造口右侧向外扩散10 cm半径(图1C)。造口周围皮炎是由造口中的半液体粪便与完整皮肤接触引起的,这是由于造口器械粘连不良,造口周围的粪便因手术伤口裂开和皮肤粘膜分离的综合作用而渗漏所致。

暠1.A:癎減왯죙역;B:芚왯튄륀瀾칟錮잼;C:芚왯鷺鍋튄懦

造口治疗及护理干预

使用0.9%的盐水对伤口、皮肤和造口进行卫生处理。为管理和促进手术伤口裂开的修复,将海藻酸钙覆盖创面上。在海藻酸钙和皮炎区域上覆盖一片水胶体敷料保护造口,以便构筑稳定的底盘基底,在基底上放置两件式结肠造口器具的底盘(或法兰)。2天后,由于伤口进一步裂开、伤口坏死和随后的渗漏,需要移除敷料和结肠造口器具(图2)。

2018年7月17日,术后第5天,手术伤口裂开区域扩大,大小为8x7x5 cm,存在感染和化脓性渗出液(图2)。这时需要改变管理策略。在这种情况下,造口治疗师提倡使用含银的氢化聚合物敷料(银敷料)以进行抗菌控制并吸收渗出液。将银敷料置于创腔内。为确保隔离造口与伤口并对造口周围进行良好密封以防止渗漏,在造口附近的湿性皮炎区域涂上造口粉。使用造口糊剂和水胶体条填充和覆盖由皮肤粘膜分离和造口周围霉菌导致的创面,以形成干燥的表面,在该表面放置凸形底盘(2件式结肠造口袋系统)以进一步治疗造口回缩;同时还可促进伤口愈合。

由于患者肥胖、腹胀,造口器械难以贴合,2018年7月20日,术后第7天,手术伤口裂开程度明显加重,达27x18x4 cm。创腔内不仅有明显的粪液溢出,还有不透明的纤维蛋白组织,液化坏死区平均占创面面积的30%(图2)。为了应对腹部伤口和造口的物理变化,对敷料方案进行了如下修改。

暠2.癎減왯죙역,왯코닸瞳捻뺏昑뻐价뵨駒郭뎔겜

伤口用0.9%生理盐水和0.2%聚己酰胺清洗,因为病患所在医院,一般使用0.9%生理盐水和聚己缩氨酸溶液清洗。使用盐溶液清洁和去除多余的污垢,聚己酸溶液因可抗菌,用于清洁伤口区域。清洁后,使用8号nelaton导管和10cc注射器从创腔中冲洗多余的液体。为吸收伤口渗出液,将海藻酸钙作为主要敷料或接触层放置在手术伤口裂开创面的所有区域,包括所有可见的窦道/管道开口。用于抗菌控制的辅助敷料是一种含非粘性银的氢化聚合物。最后,用三层组合纱布和聚氨酯薄膜进行外部固定(图 3 A-F)。

上述伤口敷料方案由包括负责外科医生、建议造口治疗师和护理人员在内的多学科团队商定。敷料由造口治疗师或护理人员和护士技术人员进行。除了伤口护理外,有必要继续隔离结肠造口和已有的造口周围皮肤并发症。因此,使用水胶体条和造口膏重建造口周围区域来隔离结肠造口。为了进一步覆盖和保护造口周围皮炎区域免受粪便污染,使用了20x20 cm的造口防漏片,在贴片上切出造口开口,并固定在造口周围。将带有凸面底座的可外排透明2件式造口器具贴在保护片上。

另对该患者进行了15天的随访。尽管显示伤口愈合良好,伤口敷料和造口器具持续粘附,该患者仍因合并症和败血症于2018年8月5日不幸死亡。

暠3.A:癎減왯죙역퓨코돨芚왯;B:賈痰괏빱튬뵨彊스竟係몰잼芚왯;C:芚왯鷺鍋賈痰芚왯季,눼퓨코賈痰베荳擧맥;D:瀾季뒀턍;E:벵陵텟칸랗늴뤽죕,莉북꼈뵨앱갚焦괌칟힛늴뤽죕;F:供냥뤽죕

讨论

在本病例研究中,患者在急诊手术后第3天出现缝合线化脓。去除几条腹部缝合线后,腹部伤口进一步裂开,同时造口的皮肤粘膜分离。这些并发症被认为是早期手术并发症,所有这些并发症都可能由损害愈合的组织张力和合并症以及感染过程引起1。

关于急诊腹部手术,术后早期并发症发生率较高(36-66%),尤其是涉及建立造口的手术。外科医生在建立造口方面的专业知识也是一个因素8。手术部位感染、造口周围皮炎和造口周围疝是主要的并发症9-13。

还值得强调的是,糖尿病和肥胖是与皮肤粘膜脱离和切口裂开相关的重要因素6。肥胖是与造口困难和术后恢复延迟相关的一个因素,因为难以切除足够的肠道以通过腹壁使肠道外露来建立造口。由于腹内压升高、组织灌注减少以及白色脂肪组织的慢性炎症会削弱皮肤的抗张强度,肥胖个体更容易出现伤口裂开、手术部位感染和伤口愈合延迟8,14,15。糖尿病与伤口愈合延迟之间的关联也有据可查。伤口愈合的所有阶段都受到糖尿病的影响,长期炎症被认为会阻碍肉芽组织的成熟,也会阻碍由于血管受损和由此导致的缺血而导致伤口内拉伸强度的发展1,16。

手术后,造口周围皮肤状况是最常见的问题,占病例的10-70%17,18。造口周围皮炎可能在生命早期或晚期发生在造口患者的皮肤周围。这种并发症会给患者自我护理带来折磨、痛苦和困难,尤其是在无法充分获得造口器具和辅助护肤产品的情况下19。造口器具和敷料在3天(72小时)内保持完好,没有任何渗漏。这是一个积极的结果,减少了连续移除以及更换敷料和造口器具的继发性损伤。

在围手术期和术后阶段对患者进行全面的护理评估有助于识别那些具有手术恢复风险的患者。评估包括患者腹部形状、手术伤口完整性或稳定性、造口的位置和构造,以及可以最大限度减少并发症的疤痕。

进行护理诊断有助于实施针对个体患者及其护理需求的护理干预措施20。在确实发生并发症的情况下,例如我们病例研究中描述的情况,需要及时的造口治疗护理干预来管理已经发生的皮肤缺损,造口治疗师可以使用各种造口和皮肤辅助产品,例如用于造口、造口皮肤屏障和密封的粘合剂和粉末,以及选择合适类型的造口底盘和造口袋1。此外,护士需要了解护理复杂伤口和造口患者的原则以及多学科医疗团队参与的重要性;需要更多护士掌握这一专业领域的技能21-23。一些指南也阐述了造口周围皮肤护理、造口护理和器具选择的重要性,以及如何预防和治疗手术后早期和晚期造口并发症。遵守临床实践指南中关于上述因素的建议可以改善患者评估,协助早期协同干预和并发症管理,在总体上改善患者的生活质量和卫生服务结果13,17,24。

结论

本文讨论了患者出现切口裂开、造口皮肤粘膜脱离以及疝修补术和结肠造口术形成后的造口周围皮炎等术后并发症。这些并发症需要造口治疗师的创造性策略来提供复杂的伤口和造口护理,包括正确应用和使用造口设备和皮肤护理产品,以最大限度地减少粪便污染伤口的风险,优化伤口愈合过程,保持患者舒适度。

利益冲突声明

作者声明不存在利益冲突。

资金支持

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Iraktânia Vitorino Diniz*

Doctoral student, Federal University of Paraíba, Postgraduate Nursing, PPGEN, João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brazil

Golfo da Califórnia Street, 90, Cabedelo, Paraíba, Brazil

Email iraktania@hotmail.com

Isabelle Pereira da Silva

Master’s student, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Department of Nursing, Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil

Email isabelle_dasilva@hotmail.com

Lorena Brito do O’

Nursing student, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Department of Nursing, Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil

Email lorena_ito@hotmail.com

Isabelle Katherinne Fernandes Costa PhD

Teacher, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Department of Nursing, Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil

Email isabellekfc@yahoo.com.br

Maria Júlia Guimarães Oliveira Soares PhD

Teacher, Federal University of Paraíba, Postgraduate Nursing, PPGEN, João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brazil

Email mmjulieg@gmail.com

* Corresponding author

References

- Murken DR, Bleier JIS. Ostomy-related complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2019;32(3):176–182.

- United Ostomy Associations of America (UOAA). New ostomy patient guide. United States: The Phoenix/UOAA; 2020. Available from: https://www.ostomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/UOAA-New-Ostomy-Patient-Guide-2020-10.pdf

- National Cancer Institute (INCA). Types of cancer: bowel cancer. Ministry of Health; 2020. Available from: https://www.inca.gov.br/sites/ufu.sti.inca.local/files//media/document//cancer-in-brazil-vol4-2013.pdf

- Mota MS, Gomes GC, Petuco VM. Repercussions in the living process of people with stomas. Text Contexto Enferm 2016;25(1):e1260014.

- Maydick-Youngberg D. A descriptive study to explore the effect of peristomal skin complications on quality of life of adults with a permanent ostomy. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(5):10–23.

- Koc U, Karaman K, Gomceli I, Dalgic T, Ozer I, Ulas M, et al. A retrospective analysis of factors affecting early stoma complications. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(1):28–32.

- Gálvez ACM, Sánchez FJ, Moreno CA, Fernández AJP, García RB, López MC, et al. Value-based healthcare in ostomies. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(16):5879.

- Moody D, Wallace A. Stories from the bedside: the challenges of nursing the obese patient with a stoma. WCET J 2013;33(4):26–30.

- Engida A, Ayelign T, Mahteme B, Aida T, Abreham B. Types and indications of colostomy and determinants of outcomes of patients after surgery. Ethiop J Health Sci 2016;26(2):117–20.

- Spiers J, Smith JA, Simpson P, Nicholls AR. The treatment experiences of people living with ileostomies: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. J Adv Nurs 2016 Nov;72(11):2662–2671.

- Ribeiro MSM, Ferreira MCM, Coelho SA, Mendonça GS. Clinical and demographic characteristics of intestinal stoma patients assisted by orthotics and prosthesis grant program of the Clinical Hospital of the Federal University of Uberlandia, Brazil. J Biosci 2016;32(4):1103–9.

- Aahlin EK, Tranø G, Johns N, Horn A, Søreide JA, Fearon KC, et al. Risk factors, complications and survival after upper abdominal surgery: a prospective cohort study. BMC Surg 2015;15(1):83.

- Chabal LO, Prentice JL, Ayello EA. WCET® International Ostomy Guideline. Perth, Australia: WCET®; 2020.

- Williamson K. Nursing people with bariatric care needs: more questions than answers. Wounds UK 2020;16(1):64–71.

- Colwell JC, Fichera A. Care of the obese patient with an ostomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2005;32(6):378–383.

- Patel S, Srivastava S, Singh MR, Singh D. Mechanistic insight into diabetic wounds: pathogenesis, molecular targets and treatment strategies to pace wound healing. Biomed Pharmacother 2019;112:108615.

- Domansky RC, Borges EL. Manual for the prevention of skin injuries: evidence-based recommendations. 2nd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Rubio; 2014.

- Stelton S. CE: Stoma and peristomal skin care: a clinical review. Am J Nurs 2019 Jun;119(6):38–45.

- Costa JM, Ramos RS, Santos MM, Silva DF, Gomes TF, Batista RQ. Intestinal stoma complications in patients in the postoperative period of rectal tumor resection. Current Nurs Mag 2017; special ed: 35–42.

- Santana RF, Passarelles DMA, Rembold SM, Souza PA, Lopes MVO, Melo UG. Nursing diagnosis risk of delayed surgical recovery: content validation. Rev Eletr Nurse 2018;20:v20a34.

- Beard PD, Bittencourt VLL, Kolankiewicz ACB, Loro MM. Care demands of ostomized cancer patients assisted in primary health care. Rev Enferm UFPE 2017;11(8):3122–9.

- Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, & Guideline Development Task Force. WOCN Society clinical guideline: management of the adult patient with a fecal or urinary ostomy: an executive summary. J WOCN 2018;45(1):50–58.

- Pinto IES, Queirós SMM, Queirós CDR, Silva CRR, Santos CSVB, Brito MAC. Risk factors associated with the development of complications of the elimination stoma and the peristomal skin. Rev Enf 2017;4(15):155–166.

- Marques GS, Nascimento DC, Rodrigues FR, Lima CMF, Jesus DF. The experience of people with intestinal ostomy in the support group at a university hospital. Rev Hosp Univ Pedro Ernesto 2016;15(2):113–21.