Volume 41 Number 3

The nursing assessment of pemphigus vulgaris ulcers

Mariana Takahashi Ferreira Costa, Luiza Keiko Matsuka Oyafuso, Mônica Antar Gamba and Kevin Y Woo

Keywords nursing, skin diseases, dermatology, vesiculobullous, acantholysis

For referencing Costa MTF et al. The nursing assessment of pemphigus vulgaris ulcers. WCET® Journal 2021;41(3):27-37

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.3.27-37

Submitted 16 March 2021

Accepted Accepted 18 July 2021

Abstract

Introduction Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is a severe autoimmune bullous dermatosis resulting in the formation of intraepidermal blisters affecting the skin and mucous membranes. Epidemiologic data shows an incidence of 0.1–0.5 per 100,000 inhabitants per year, and mortality at almost 5–10%.

Objective The objective of this integrative literature review was to examine the classification/terminology of PV ulcers according to the description of skin lesions.

Method This is an integrative review of primary studies, series/clinical reviews or validation studies that describe or evaluate PV ulcers. Search strategies included relevant papers that were published between 2011–2019 using terms such as pemphigus, skin ulcer, dermatology, diagnostic, nursing assessment. The studies were selected for analysis after application of eligibility criteria and exclusion by duplicity.

Results The initial search resulted in 2,934 publications; 14 articles were eligible for analysis. The synthesis of the studies was organised as follows – 57.14% series/clinical reviews, 50% written by physicians, 64.29% level of evidence 4. The terminology used to describe PV ulcers included skin/mucosal erythema, new erythema, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, oral lesions, epithelialisation scabs, blisters, bullae, erosions, eroded areas, erosive exudative lesions, dry erosive.

Conclusions Studies with better levels of evidence are needed on this issue in order to determine the best way to describe the lesions using the dermatological glossary for nursing assessment.

Introduction

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is a severe autoimmune bullous dermatosis in which the antibodies destroy the desmosomes, resulting in the formation of intraepidermal blisters that affect the skin and mucous membranes. PV occurs mainly between the 4th and 6th decades of life, affecting males and females with an incidence of 0.1–0.5 / 100,000 inhabitants / year and with a mortality rate of 5–10%. The disease distribution is universal, but most commonly affects people of Jewish ancestry–3.

In PV, autoantibodies act predominantly on desmoglein 3 (Dsg3) which is expressed predominantly in the deeper layers of the epidermis2,3. Identifying the layer on which acantholysis occurs is a factor that assists in the diagnosis of bullous dermatoses. For example, it is possible to differentiate PV from pemphigus foliaceus by the site where acantholysis occurs, since pemphigus foliaceus affects the granular layer whereas PV affects the spinous layer2,3. These manifestations involve the formation of blisters with consequent ulceration and skin damage which can be devastating, affecting social interaction and even loss of employment4.

The impact of disfigurement associated with PV on patients’ quality of life, self-image, family and social dynamics has been well documented4. In addition to cutaneous involvement, PV may involve mucosal tissue in the mouth, pharynx, larynx, nasal passage and ear canals (Figures 1 & 2). Areas affected by the disease can compromise normal breathing as well as the ability to speak and to eat to maintain adequate nutritional intake2,3.

Figure 1. Cutaneous lesions on trunk

Figure 2. Oral mucosa lesions

The classification of PV has been the object of studies in recent years. The Commitment Index of Skin and Mucous in Pemphigus Vulgaris uses four different parameters to score the disease clinical status: (a) the number of blisters or eroded areas; (b) the size of blisters or eroded areas; (c) evidence of the Nikolsky sign (where sliding the finger firmly with pressure over the skin separates normal-appearing epidermis, producing an erosion); and (d) mucousal involvement and sepsis. The total score may vary from 0–100, and the patients are classified as follows: Class I score 0–30; Class II 35–65; Class III 70–100, meaning that the higher the score, the more critical the status1.

Pemphigus classifications tools, the Pemphigus Disease Area Index (PDAI) and the Japanese Pemphigus Disease Severity Score (JPDSS), were compared by Shimizu et al.5. PDAI measures skin and mucosal involvement by size and number of blisters in each anatomical region, and the score ranges from 0–263. JPDSS uses parameters for scoring: (I) the ratio of affected area of skin to the body’s surface area; (II) the presence or absence of Nikolsky’s sign phenomenon; (III) the number of newly developed blisters per day; (IV) the presence or absence of oral lesions; and (V) the titer of pemphigus antibodies. Each parameter has a score ranging 0–3. In Shimizu et al.’s study5, the results show that PDAI more accurately reflects disease severity. The authors therefore propose the use of indexes to guide a uniform treatment according to grading criteria. Corticotherapy is the treatment of choice, and it can be associated with immunosuppressants if there is no improvement with isolated corticotherapy2,3.

Although considered a relatively rare disease, there is a need for nurses to recognise skin lesions associated with PV and communicate appropriate findings in order to help patients seek early treatment, evaluate disease progression, and monitor responses to treatment6. The purpose of this integrative review was to describe the taxonomy for the description and assessment of skin changes related to PV by nurses.

Method

This integrative review was conducted to identify, analyse and synthesise studies that use qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods in this theme7. We have chosen the method described by Mendes7 to guide the review which consisted of six stages: (1) formulation of the guiding question; (2) establishment of criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies and data collection (search in the literature); (3) categorisation of studies; (4) evaluation of studies included in the review; (5) analysis and interpretation of data; and (6) synthesis of the knowledge evidenced in the articles analysed (presentation of the results)7.

Formulation of the guiding question

The research question was – How are the lesions that characterise PV described in the literature in its definition and classification?

Establishment of criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies and data collection

The medical and nursing literature was searched from 2011–2019 in conjunction with a librarian to assist in answering the research question. Searches included Web of Science, LILACS, EMBASE, SCOPUS, PUBMED, BVS, CINAHL and COCHRANE with specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. To identify relevant publications, databases were searched using the following key terms – dermatology, pemphigus, skin ulcer, diagnostic and nursing assessment. The inclusion criteria included articles published in English, Spanish and Portuguese, peer-reviewed literature and consensus documents; the dates of publication were from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2019. Commentary and editorials were excluded.

Categorisation of studies

Selected studies were then categorised according to the six levels of evidence8:

• Level 1: evidence from meta-analysis of multiple controlled and randomised studies.

• Level 2: evidence from individual studies with experimental design.

• Level 3: evidence from quasi-experimental studies, time series or case-controls.

• Level 4: evidence from descriptive studies (non-experimental or qualitative approach).

• Level 5: evidence of case / experience reports.

• Level 6: evidence based on expert committee opinions, including interpretations of non-research based information, regulatory or legal opinions.

Evaluation of studies included in the review

This step included the evaluation of the studies as well as data extraction. A standardised data collection form was used to extract the following information: authors; professional category of authors; title of the article; journal; year of publication; level of evidence; goals; methodological design; sampling detail; synthesis of information; evaluation/assessment of skin ulcers in pemphigus; methodology used to validate the instrument; description of the instrument; terminology used to characterise ulcers; and results and conclusions.

Analysis and interpretation of data

The data evaluation stage included evaluating the quality of the primary sources using a specific methodological approach to determine the quality of the source. The data were evaluated and coded according to two criteria – the methodological rigour and the relevance to the topic of skin assessment. Studies were analysed and the rigour rated on a score from 0–4. The relevance to the topic was also scored and indicated, with 1 having no relevance to the topic and 2 indicating the article was relevant.

Synthesis / presentation of results

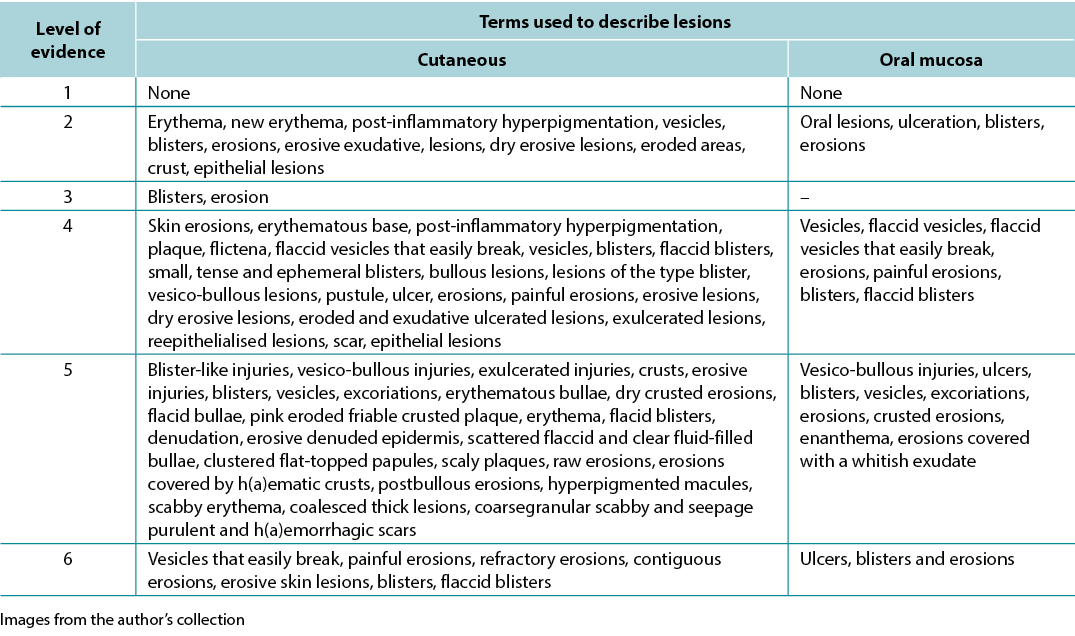

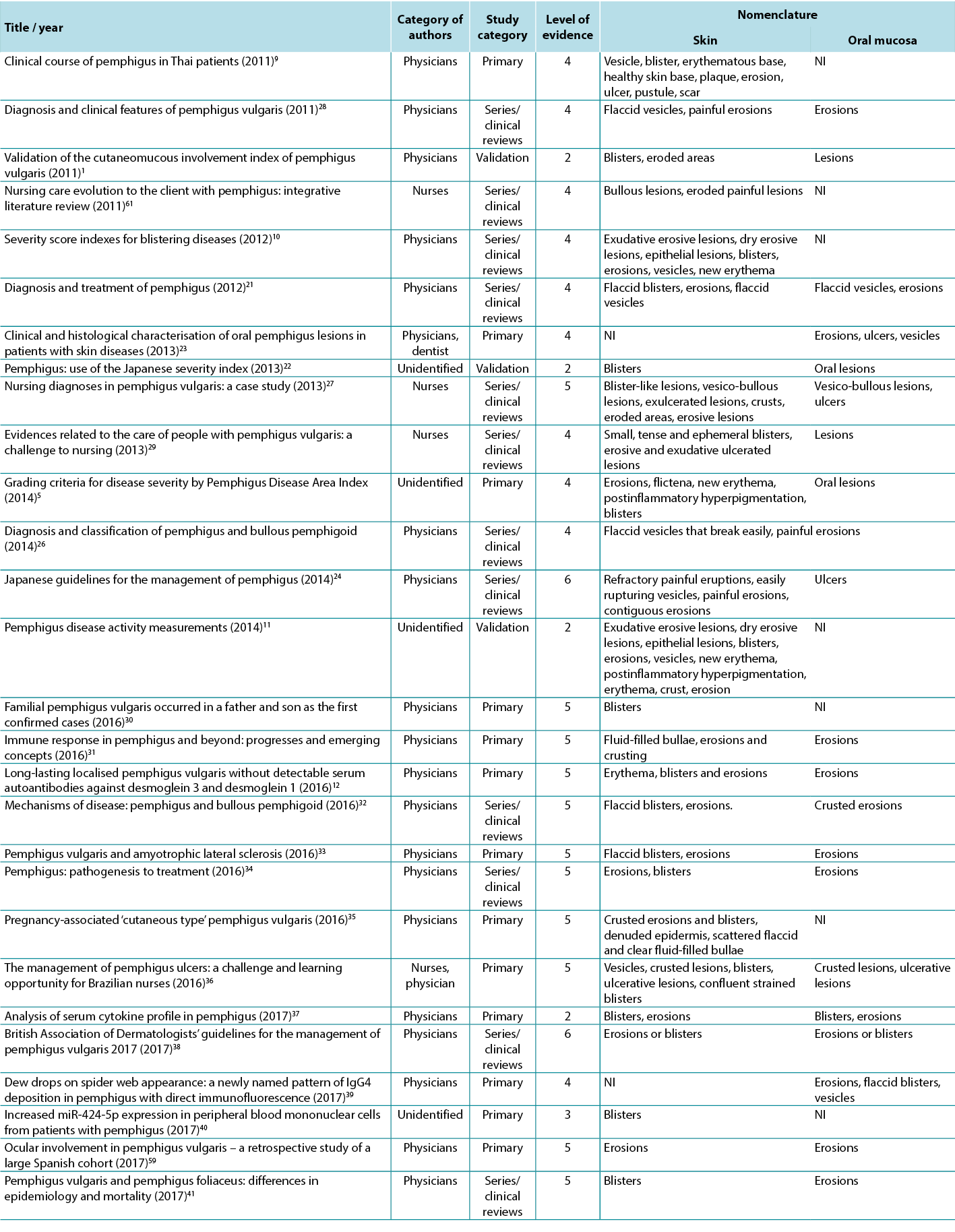

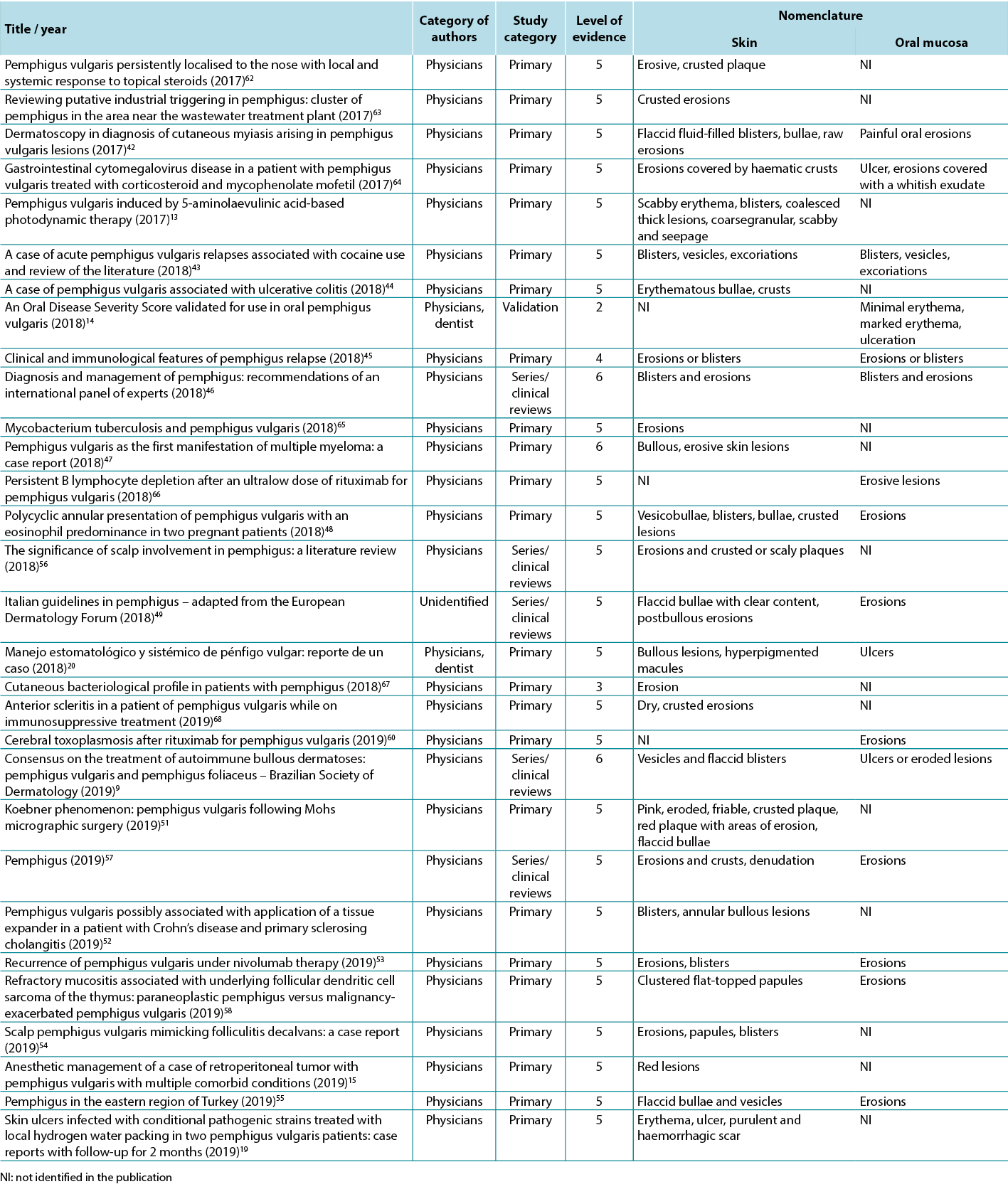

The data analysis for the qualitative studies were reviewed and were systematically categorised, analysed and synthesised, and placed into distinct themes, patterns and relationships using a matrix method. The synthesis of the studies was organised into three axis: (1) characteristics of scientific publications on PV; (2) terminology used to describe cutaneous lesions related to PV (Table 1); and (3) comparison of terminologies used in studies and dermatological description of skin lesions.

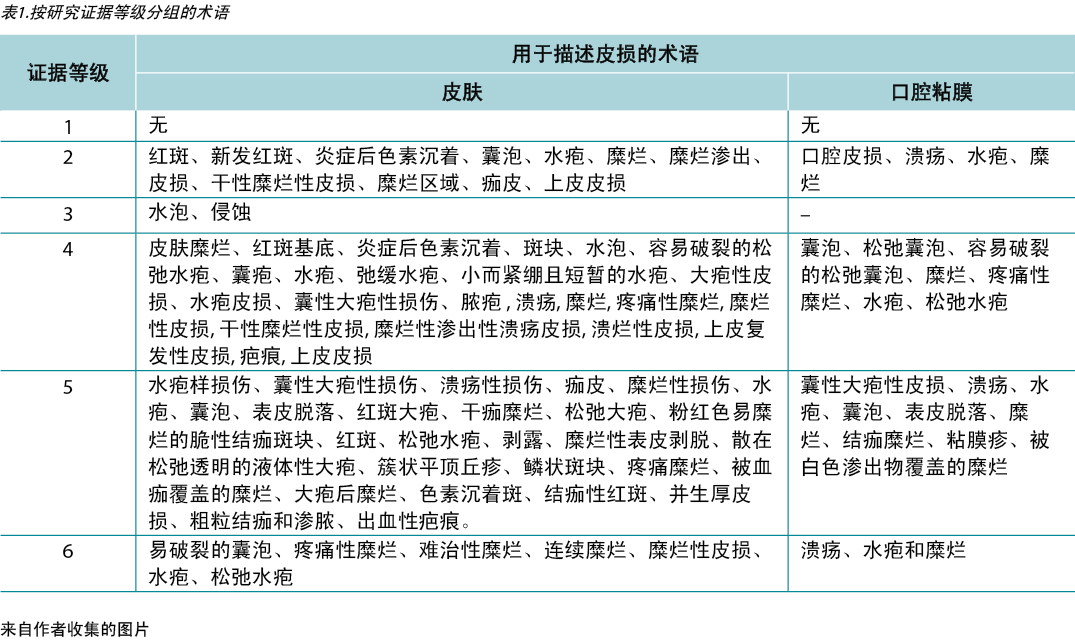

Table 1. Terms identified grouped by level of evidence of the studies

Ethical and legal aspects

The research project was submitted and approved by the Research Ethics Committee / UNIFESP: 0450/2015 and followed the ethical and legal precepts of research with human beings according to Resolution 196/96 of the National Health Council.

Results

The initial search identified 2934 articles; 356 articles were included from review of the titles. After review of the abstracts, another 258 papers were not suitable for review since they did not meet the inclusion criteria; specifically, the excluded papers did not address PV and lesion assessment. A total of 58 articles were then selected for the study after exclusion of 40 duplicates. Of the 58 articles, 37 (63.79%) were primary studies, 17 (29.31%) were series/clinical reviews and four (6.90%) were validation studies.

A variety of terms were used in the literature to describe PV-related lesions. These are summarised below.

Primary skin lesions

Flat spots or maculae

The first is flat skin lesions, including colour changes and blood-vascular stains. Nomenclature used were new erythema, erythema, minimal erythema, and marked erythema9–15. Erythema is defined as a red colour resulting from vasodilation that disappears by digital pressure or diascopy. Diascopy is a refinement in which a piece of clear glass or plastic is pressed against the skin while the observer looks directly at the lesion under pressure15,16.

Solid formations / oedematous elevations

Solid formations may include bullae and papulae (small superficial solid elevations of the skin) while oedematous elevations could be cutanaeous lesions, scales or pustulae (defined elevation of the skin containing purulent fluid). These clinical features might be associated with a positive Nikolsky sign17.

Pigment spots

Nomenclature used in this section were post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and hyperpigmented macules5,11,16, 18–20. Hyperchromia is defined as a spot of variable colour, caused by the increase of melanin or deposit of another pigment. The increase in melanin / melanodermic spots has a variable colour from light brown to dark bluish or black16,18.

Liquid content

Nomenclature used here were vesicles, blisters and bullous lesions1,5,9,10,12,13,20–55. Vesicles are defined as of circumscribed elevation, containing clear liquid, up to 1cm in size. The fluid, which is primitively clear (serous), may become cloudy (purulent) or red (haemorrhagic)16,18. A blister is defined as elevation containing clear liquid, greater than 1cm in size. The fluid, which is primitively clear, may become yellowish-red or reddish, forming a purulent or haemorrhagic blister16,18. The term bullous lesions is used to refer to any liquid collections.

Secondary skin lesions

Thickness changes

Nomenclature used here are epithelial lesions, denuded epidermis and scar9–11,13,19,22,35,51,54,56–58. A scar is defined as a flat, salient or depressed lesion, without grooves, pores and hairs, movable, adherent or retractable. It associates atrophy with fibrosis and dyschromia. It results from the repair of destructive process of the skin. It can be: atrophic (thin, pleated, papyraceous); pitted (small holes appear); or hypertrophic (nodular, elevated, vascular, with excessive fibrous proliferation, with a tendency to regress)16,18.

Tissue losses

Nomenclature used are erosions, eroded areas, erosive lesions, crust, ulceration, ulcer, ulcerative lesions, raw erosions and excoriations1,5,9–15,19–21,23–60. Erosion or exulceration is defined as superficial loss that affects only the epidermis. Crust is defined as a concretion of light yellow to greenish or dark red colour which forms in an area of tissue loss. It results from the desiccation of serosity (meliceric), pus (purulent) or blood (haemorrhagic), mixed with epithelial remains16,18.

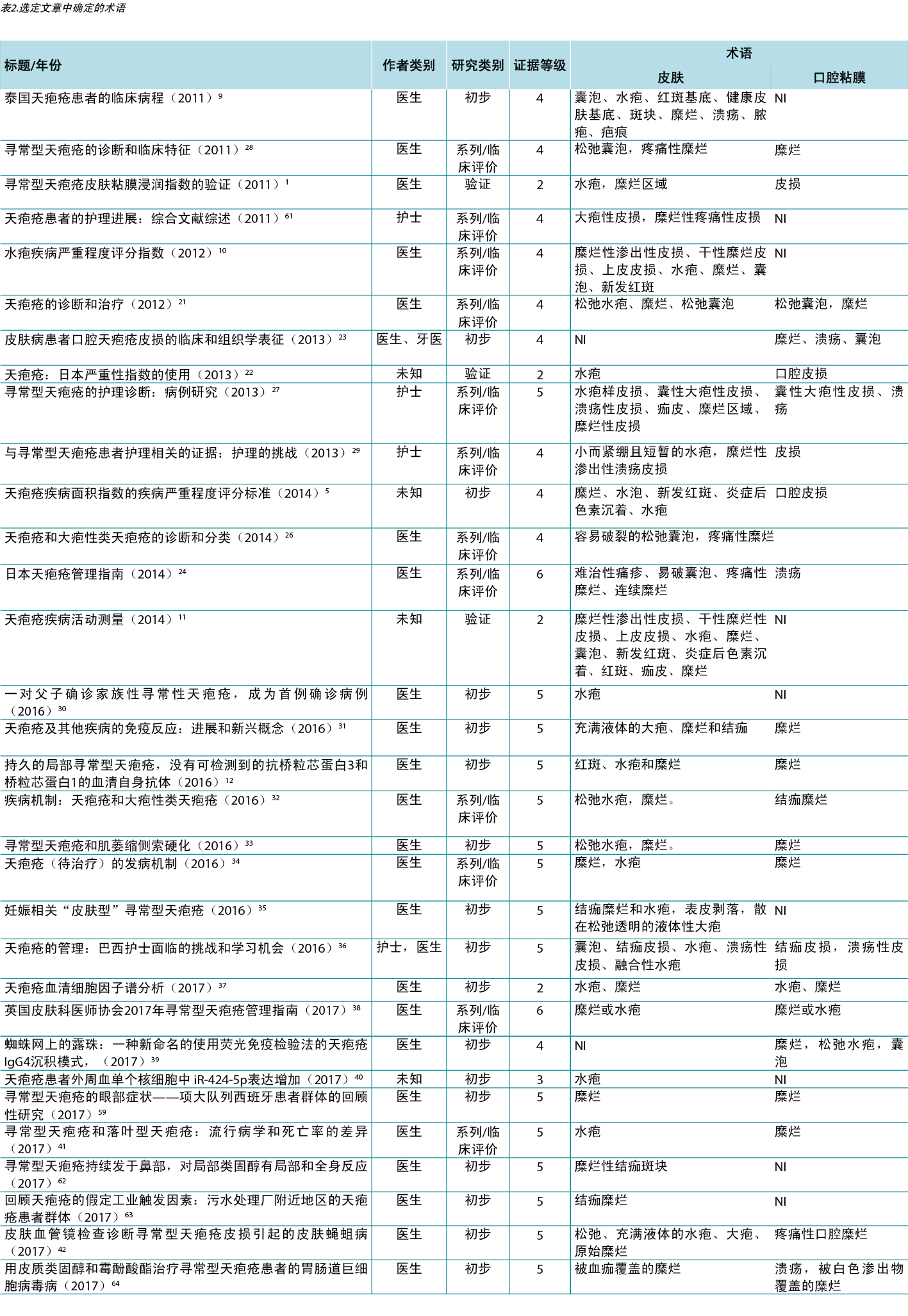

Therefore, in view of the integrative review, it was possible to identify studies describing the dermatological alterations of PV ulcers according to criteria established by dermatological glossaries. In order to illustrate the correlation of the identified terms and their corresponding study, the third analysis correlates the terms identified with the year, author category, study category and level of evidence, shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Terms identified in selected articles

Discussion

As evidenced by the results, studies in this area are scant and nurses have had little contribution. However, this is needed to highlight the consistency demonstrated between the terms used by authors and the terminology of elementary lesions.

To promote excellence in dermatological care it is necessary for nurses and health professionals to develop skills for the evaluation of cutaneous manifestations, especially skin lesions. The skin, as the largest organ of the human body, has protection as one of its numerous functions. Far beyond essentially dermatological affections, it can translate the person’s general condition, signalling the presence of systemic disorders and sometimes presenting manifestations that are recognised as cutaneous markers of certain pathologies. However, the paucity of studies in PV has led to poor description and evaluation of skin lesions in PV. This may result in delayed diagnosis and suboptimal care and treatment6,20,29,36.

In fact, this subject points to the need for further investigation to compose a framework of knowledge based on scientific evidence in this area, so that dermatology nurses may develop an accurate consideration of the assessment of skin manifestations, especially skin ulcers. These professionals publish little on this subject, which corroborates with the lack of formulation of new evidence for their topical care. This lack of evidence makes nursing assistance to these people less secure, since a theoretical framework is essential for evidence-based care given the specificity and complexity of caring for these patients16,25.

The main researchers in this area, Brandão and Santos4,6,25,29, investigate this issue from the point of view of integral care, with a social-poetic approach and a nursing diagnosis that support the comfort and relief of pain among those affected.

Through clinical observation, the authors of this study concluded that traditional topical care generates high rates of hospital stay, pain and discomfort. This clinical observation was the trigger to build evidence of the best evaluation tools and descriptors and base this on the use of topical therapies that optimise the potential of healing by managing cofactors such as pH, thermoregulation, humidity, microbial load and adherence of the dressing25,36.

It can be observed that when the nursing descriptor was used, the literature search resulted in a much smaller number of articles in comparison to those searches without this descriptor. Although dermatological nursing is a recognised specialty in Brazil, the descriptors ‘nursing in dermatology’ or ‘dermatologist nurse’ or ‘dermatological nursing’ do not exist. Therefore, in search of studies, the descriptors ‘nursing’ and ‘nursing assessment’ were used.

Among the nomenclatures used in the different levels of studies, we can observe that all use the dermatological glossary to describe the lesions, with only a small variation with detailed description of the tissue such as exudative erosions. Despite the scarcity of studies written by nurses, it was possible to observe that the terminology used did not differ between professional categories25,29,36.

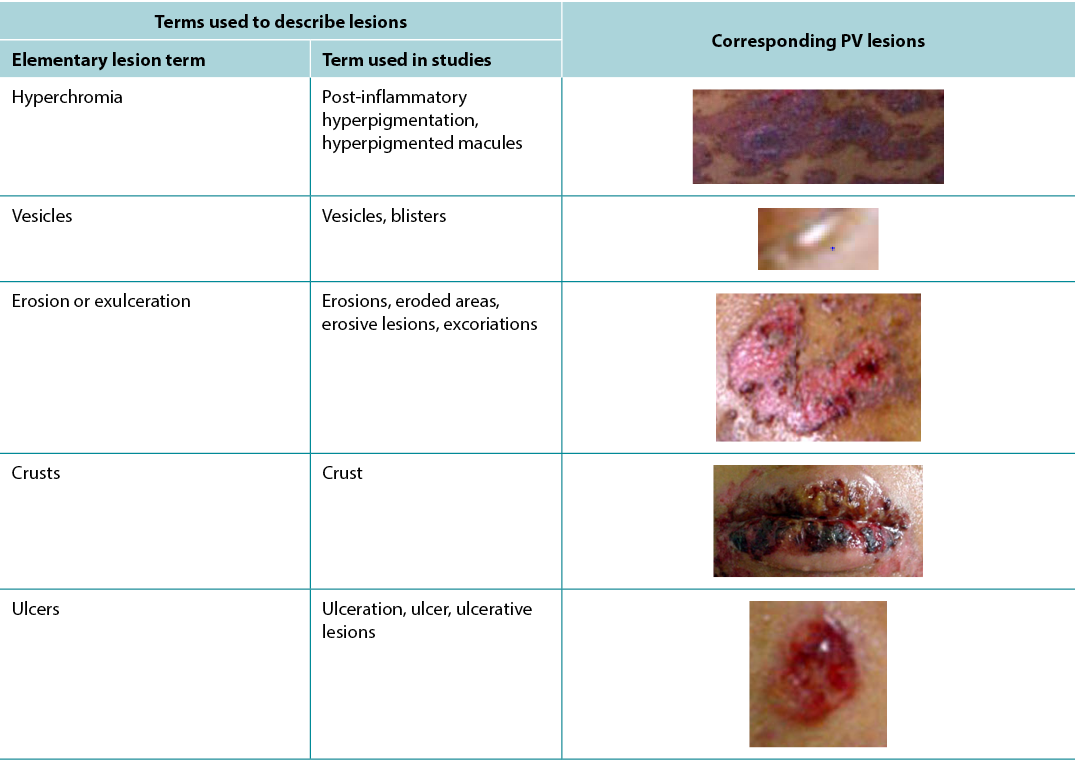

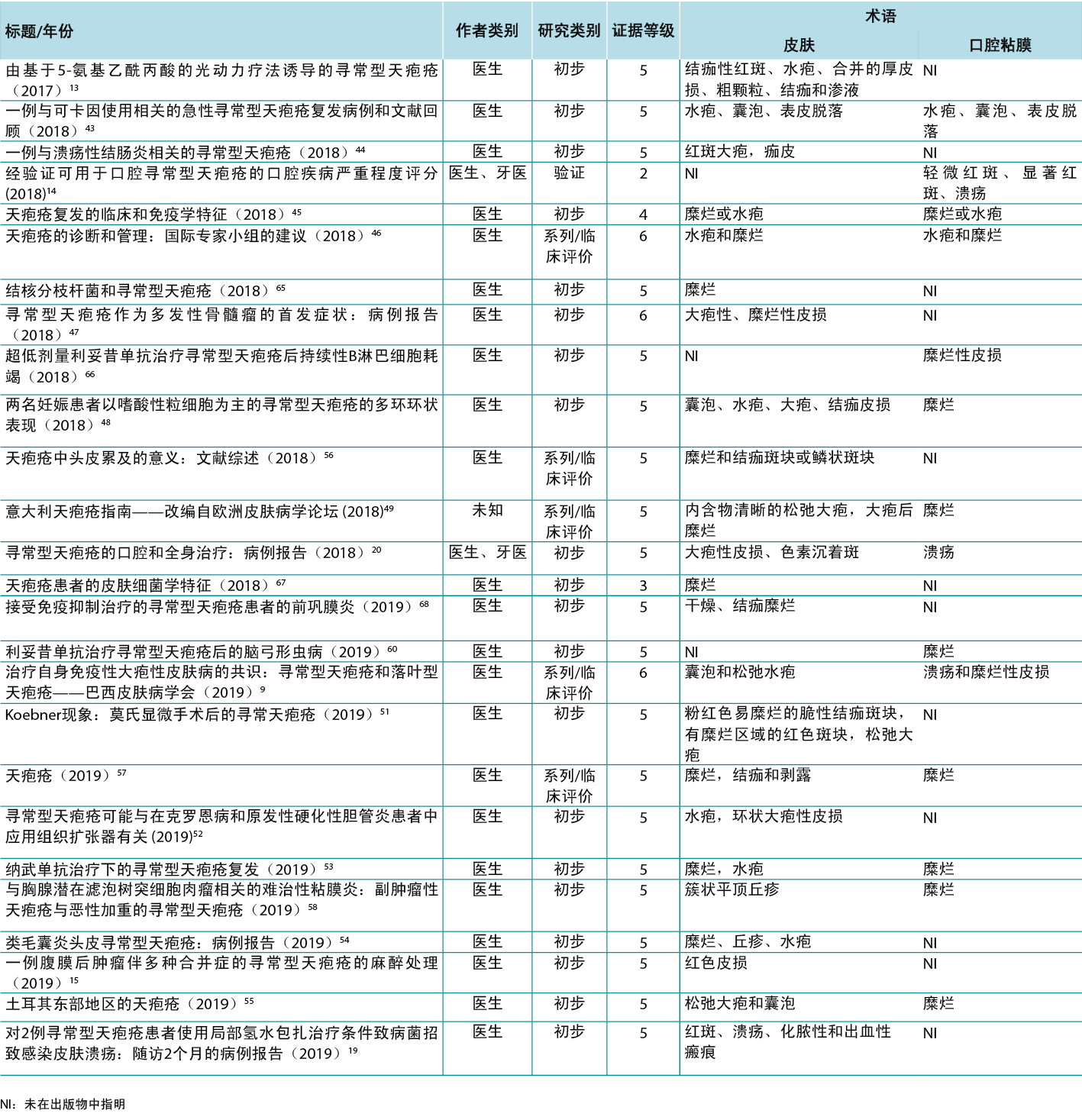

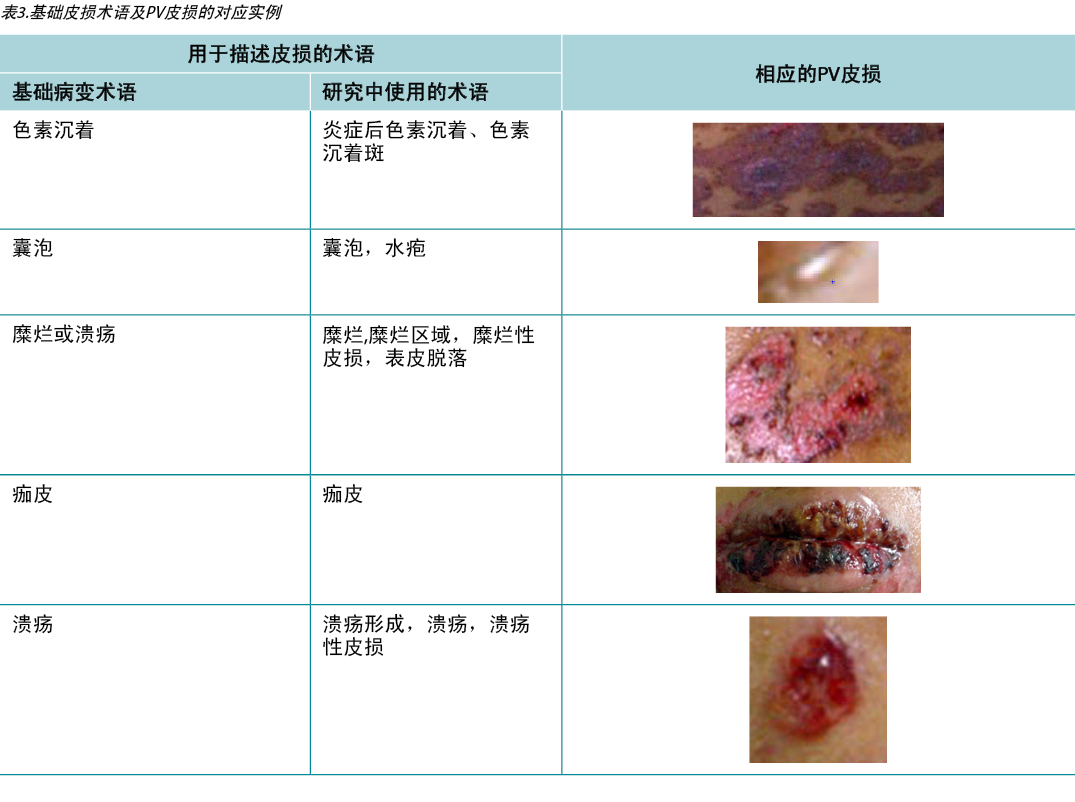

According to Sampaio and Rivitti3, skin lesion classification is like letters of the alphabet; just as letters compose words, through their combination they form morphological signs that allow us to “read” the cutaneous manifestations16,18. As shown in the results, the skin lesions, associated with complementary information, can help in the definition of diagnostic hypotheses, intervention decision and monitoring of healing evolution. The use of clinical descriptors to characterise skin lesions or ulcers standardises this information, making it more understandable for health professionals. In Table 3 examples of PV lesions related to the correspondent elementary skin lesion term are given.

Table 3. Elementary skin lesion terms and corresponding examples of PV lesion

Skin lesions are classified into six groups: colour changes; oedematous elevations; solid formations; liquid formations; thickness changes; and losses and repairs. This classification may be grouped into:

- Primary: flat spots or maculae (colour changes); solid (solid formations); oedematous elevations (rash, oedema); liquid content (liquid formations).

- Secondary: changes in consistency and thickness (changes in thickness); or loss of substance (tissue losses and repairs)16,18.

Diagnoses, interventions and nursing outcomes according to the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA), Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) and Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) for patients with PV were proposed by Pena et al.27. The analysis of the nursing diagnosis ‘impaired skin integrity’ and ‘impaired oral mucous membrane’ made it possible to perceive that the nurse assessment to arrive at this diagnosis does not require a specialised evaluation since the defining characteristics for such diagnoses involve only the rupture of the skin or mucosa, not requiring evaluation of thickness, tissue type or other characteristics assessed in a wound. In the proposed NOC outcome ‘healing’, in which one of the indicators used was granulation tissue, the knowledge about the tissue types that a wound can present is necessary. The proposed NIC intervention ‘wound care’ involves the decision about the intervention to be adopted, presupposing specific knowledge, skills and preparation in this area27. Considering the increasing performance of dermatology nursing as a specialty, these nomenclatures are becoming increasingly familiar to nurses.

As the nomenclature used to describe skin lesions becomes standard, whether secondary to PV or not, the interlocution between professionals tends to become more uniform, avoiding misunderstanding and resulting in safer patient care. However, in wound assessment there is still a great diversity in the terminology used to describe the skin damage, for example: slough and fibrin; wet necrosis and liquefaction necrosis; dry necrosis, ‘scar’ and pressure injury; granulation tissue, extra cellular matrix or viable tissue. This richness of terminologies causes doubt, within professionals consulting the records, often generating interpretations that differ from those of the person who registered them. In order to standardise the register of PV ulcers, we suggest the use of the elementary lesions terms – vesicles, blisters, erosions, ulcers and generalised crusts.

The chronic character and the cutaneous manifestation of PV steal from the patient their right to confidentiality. Frequently, the lesions are associated with contagion, impacting on social and familiar relations, and perpetuating stigma and isolation4. For Brandão, nursing actions become productive as they aim to reach the patient’s holistic balance. Thus there is a constant search for alternatives that attend to the needs of people suffering from changes in skin integrity, and the development of technologies and techniques that promote healing in order to improve their quality of life4,27.

Conclusions

This study compared the terminology used to describe cutaneous ulcers in PV studies with the terminology used in describing elementary lesions. It also demonstrated that the publications authored by physicians were the most common ones, followed by those authored by nurses, and lacked uniformity in the description of the lesions.

This study demonstrated that the skin changes in PV can be classified as primary skin lesions (colour changes and liquid collections) or secondary skin lesions (changes in thickness and tissue loss). In view of the extensive dermatological glossary, lesions secondary to PV can be characterised as vesicles, blisters, erosions, ulcers and generalised crusts to support the practice of nursing in dermatology.

Lastly, it is concluded that studies with a higher level of evidence in this area are necessary in order to determine the best way to evaluate the lesions, as well as the nomenclature to be used for improved nursing care.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

寻常型天疱疮溃疡的护理评估

Mariana Takahashi Ferreira Costa, Luiza Keiko Matsuka Oyafuso, Mônica Antar Gamba and Kevin Y Woo

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.3.27-37

摘要

引言 寻常型天疱疮(PV)是一种严重的自身免疫性大疱性皮肤病,会导致表皮内水疱形成,影响皮肤和粘膜。流行病学数据显示,每年每100,000名居民的发病率为0.1-0.5,死亡率约为5-10%。

目的 本综合文献综述的目的是根据皮损的描述检查PV溃疡的分类/术语。

方法 这是对描述或评估PV溃疡的初步研究、系列/临床评价研究或验证研究的综合综述。检索了使用天疱疮、皮肤溃疡、皮肤病学、诊断、护理评估等术语在2011-2019年间发表的相关论文。在应用资格标准并进行重复排除后选择研究进行分析。

结果 最初检索出2,934篇出版物;14篇文章符合分析条件。研究文献分为以下几类-系列/临床评价研究(57.14%)、由医生撰写(50%)、4级证据等级(64.29%)。用于描述PV溃疡的术语包括皮肤/粘膜红斑、新发红斑、炎症后色素沉着、口腔皮损、上皮结痂、水疱、大疱、糜烂、糜烂区域、糜烂性渗出性皮损、干性糜烂。

结论 在这个问题上需要更佳证据水平的研究,以确定使用皮肤病学术语表进行护理评估来描述皮损的最佳方式。

引言

寻常型天疱疮(PV)是一种严重的自身免疫性大疱性皮肤病,其中抗体破坏桥粒,导致形成影响皮肤和粘膜的表皮内水疱。PV主要发生在4-6岁的男性和女性之间,发病率为0.1-0.5/100,000居民/年,死亡率为5-10%。该疾病分布广泛,但最常影响犹太血统群体-3。

在PV中,自身抗体主要作用于桥粒芯蛋白3(Dsg3),其主要在表皮的深层表达2,3。确定发生棘层松解的层有助于诊断大疱性皮肤病。例如,可以通过棘层松解发生的部位将PV与落叶天疱疮区分开来,因为落叶天疱疮影响颗粒层,而PV影响棘层2,3。棘层松解表现会形成水疱,继而导致溃疡和皮肤损伤,是一种灾难性疾病,会影响社交互动,甚至让人失去工作4。

已有充分证据表明,与PV相关的毁容会影响患者生活质量、自我形象、家庭和社交活动4。除了皮肤受累外,PV还可能影响口腔、咽、喉、鼻道和耳道中的粘膜组织(图1和2)。受疾病影响的区域可能会影响正常呼吸、说话能力以及保持足够营养摄入的进食能力2,3。

图1.躯干皮损

图2.口腔粘膜皮损

PV分类是近年来的研究对象。寻常型天疱疮中皮肤和黏液的累及指数使用四个不同的参数来对疾病的临床状态进行评分:(a)水泡或糜烂区域的数量;(b)水泡或糜烂区域的大小;(c)Nikolsky征的证据(手指在皮肤上用力滑动分离正常表皮,造成糜烂);(d)粘膜受累和脓毒症。总分可能从0到100不等,患者分类如下:I类评分0-30;II类35-65;III级70-100,评分越高,表示状态越危急1。

Shimizu等人5比较了天疱疮分类工具、天疱疮疾病面积指数(PDAI)和日本天疱疮疾病严重程度评分 (JPDSS)。PDAI通过每个解剖区域中水疱的大小和数量来测量皮肤和粘膜受累情况,评分范围为0-263。JPDSS使用参数进行评分:(I)皮肤受影响面积与体表面积之比;(II)有无Nikolsky征象;(III)每天新出现的水泡数; (IV)口腔有无皮损;(V)天疱疮抗体的滴度。每个参数都有一个范围为0-3的评分。在Shimizu等人的研究5中,结果表明PDAI更准确地反映了疾病的严重程度。因此,作者建议使用指标根据分级标准指导统一治疗。皮质疗法是首选的治疗方法,如果单独的皮质疗法没有改善,可以使用免疫抑制剂作为辅助2,3。

虽然PV被认为是一种相对罕见的疾病,但仍需护士识别与PV相关的皮肤损伤,交流适当的发现,以帮助患者寻求早期治疗,评估疾病进展,并监测治疗反应6。本综合评价的目的是描述护士说明和评估与PV相关的皮肤变化的分类法。

方法

进行此综合评价是为了识别、分析和整合在本主题中使用定性、定量和混合方法的研究7。我们选择了Mendes7描述的方法来指导评价。评价包括六个阶段:(1)制定指导性问题;(2)制定纳入和排除研究与数据收集的标准(在文献中检索);(3)对研究进行分类;(4)评估纳入评价的研究;(5)数据分析和说明;(6)整合所分析文章中所证明的知识(展示结果)7。

制定指导性问题

研究问题是:在PV定义和分类的文献中如何描述表征PV的皮损?

制定纳入和排除研究与数据收集的标准

与图书管理员一起检索了2011-2019年的医学和护理文献,以帮助回答研究问题。根据特定的纳入和排除标准,检索了Web of Science、LILACS、EMBASE、SCOPUS、PUBMED、BVS、CINAHL、COCHRANE等系统。为确定相关出版物,使用以下关键术语检索数据库-皮肤病学、天疱疮、皮肤溃疡、诊断和护理评估。纳入标准包括以英语、西班牙语和葡萄牙语发表的文章、同行评审的文献和共识文件;发布日期为2011年1月1日至2019年12月31日。排除了评论和社论。

对研究进行分类

接下来,根据六个证据级别对选定的研究进行分类8:

• 1级证据:来自多项对照和随机研究的荟萃分析的证据。

• 2级证据:来自具有实验设计的个别研究的证据。

• 3级证据:来自准实验研究、时间序列或病例对照的证据。

• 4级证据:来自描述性研究(非实验或定性方法)的证据。

• 5级证据:病例/经验报告的证据。

• 6级证据:基于专家委员会意见的证据,包括对非研究信息、监管或法律意见的说明。

评估纳入评价的研究

本步骤包括研究评估以及数据提取。使用标准化的数据收集表来提取以下信息:作者;专业作者类别;文章的标题;杂志;出版年份;证据水平;目标;方法论设计;采样细节;信息整合;评价/评估天疱疮皮肤溃疡;用于验证仪器的方法;仪器说明;用于表征溃疡的术语;结果和结论。

数据分析和说明

数据评估阶段会使用特定的方法论来评估初始资料的质量,以确定资料的质量。根据两个标准对数据进行评估和编码:方法的严谨性和与皮肤评估主题的相关性。对研究进行分析,按0-4分对研究严谨性进行了评分。对与主题的相关性也进行了评分和指示,1表示文章与主题无关,2表示与主题相关。

结果整合/展示

对定性研究的数据分析进行了评价,并进行了系统的分类、分析和整合,并使用矩阵法将其归于不同的主题、模式和关系中。整体上,研究分为以下三点:(1)PV科学出版物的特点;(2)用于描述与PV相关的皮损的术语(表 1);(3)研究中使用的术语和皮损的皮肤病学描述的比较。

道德和法律方面

研究项目由研究伦理委员会/UNIFESP:0450/2015提交并批准,并根据国家卫生委员会第196/96号决议,遵循了人类研究的伦理和法律规定。

结果

初步检索确定了2934篇文章;356篇文章审核标题后被收录。经摘要审核,另有258篇论文因不符合纳入标准,不适合进行评价;具体而言,排除的论文没有涉及PV和皮损评估。排除了40篇重复之后,总共选择了58篇文章进行研究。在58篇文章中,37篇(63.79%)涉及初步研究,17篇(29.31%)涉及系列/临床评价研究,4篇(6.90%)涉及验证研究。

文献中使用了多种术语来描述PV相关的皮损。术语总结如下。

原发性皮损

扁平斑点或黄斑

首先是扁平皮损,包括颜色变化和血管斑。使用的名称是新发红斑、红斑、轻微红斑和显著红斑9-15。红斑被定义为由血管舒张引起的红色,通过手指按压或玻片压诊法消失。玻片压诊法是一种改进方法,将一块透明玻璃或塑料压在皮肤上,同时观察者在压力下直接观察皮损15,16。

实性隆起/水肿性隆起

实性隆起可能包括大疱和丘疹(皮肤表面较小的实性隆起),而水肿性隆起可能为皮损、鳞屑或脓疱(定义的皮肤隆起处含有脓液)。这些临床特征可能与Nikolsky阳性征象17相关。

色素斑

本节中使用的命名是炎症后色素沉着和色素沉着斑5,11,16, 18–20。色素沉着被定义为颜色可变的斑点,由黑色素的增加或另一种色素的沉积引起。黑色素/黑素皮斑增加可从浅棕色变为深蓝色或黑色16,18。

液体内容物

这里使用的命名是囊泡、水疱和大疱性皮损1,5,9,10,12,13, 20–55。囊泡被定义为界限分明的隆起,含有透明液体,大小可达1 cm。原本清澈(浆液)的液体可能会变得混浊(化脓)或红色(出血)16,18。水泡被定义为包含透明液体的隆起,大于1 cm。液体原本是透明的,可能会变成黄红色或微红色,形成化脓性或出血性水疱16,18。术语“大疱性皮损”用于指代任何积液现象。

继发性皮损

厚度变化

这里使用的术语是上皮皮损、表皮剥离和疤痕9–11,13,19, 22,35,51,54,56–58。疤痕被定义为平坦、突出或凹陷的皮损,没有凹槽、毛孔和毛发,可移动、粘附或可伸缩。疤痕将萎缩症与纤维化和皮肤变色联系起来。它是皮肤对破坏过程进行修复的结果。疤痕可以表现为:萎缩性(薄、有褶皱、纸状);有麻点(出现小孔);或肥大(结节状、隆起、血管性、纤维过度增生,有消退趋势)16,18。

组织损失

使用的术语是糜烂、糜烂区域、糜烂性皮损、痂皮、溃疡、溃疡、溃疡性皮损、原始糜烂和表皮脱落1,5,9–15,19–21,23–60。糜烂或溃疡被定义为仅累及表皮的表皮受损。痂皮被定义为在组织损失区域形成的浅黄色至绿色或深红色的凝结物。它是由浆液(糖浆状)、脓液(化脓性)或血液(出血性)与上皮残留物混合后干燥而成16,18。

因此,在综合评价中,可以根据皮肤病学术语表建立的标准识别描述PV溃疡皮肤病学改变的研究。为了说明识别出的术语与其相应研究的相关性,第三次分析将识别出的术语与年份、作者类别、研究类别和证据水平相关联,如表2所示。

讨论

结果表明,这方面的研究稀少,护士贡献较小。但需要强调的是,作者使用的术语与基本皮损术语之间具有一致性。

为了促进皮肤病学护理卓越发展 ,护士和卫生专业人员必须培养评估皮肤表现,尤其是皮损方面的技能。皮肤作为人体最大的器官,保护作用是其众多功能之一。皮肤病可以传达人体的一般身体状况信息,发出罹患全身性疾病的信号,有时还能呈现某些临床表现(视作某些疾病的皮肤状况标志)。然而,PV研究的缺乏导致对PV皮损描述和评估欠佳。这可能会导致延误诊断、次优护理以及治疗6,20,29,36。

事实上,本主题表明,需要进一步调查,建立基于该领域科学证据的知识框架,以便皮肤科护士可以准确考虑评估皮肤表现,尤其是皮肤溃疡。这些专业人士在这个主题上发表的文章很少,这证实了他们在局部护理方面缺乏新的证据。缺乏证据导致对患者的护理援助不够安全,因为照顾这类患者的特殊性和复杂性,理论框架对于循证护理至关重要16,25。

本领域的主要研究人员Brandão和Santos4,6,25,29从整体护理的角度研究这个问题,采用社会诗意的方法和护理诊断来提高病患舒适度和缓解疼痛。

通过临床观察,这项研究的作者得出结论,传统的局部护理需要很长的住院时间,并有高强度的疼痛和不适感。这一临床观察结果为建立最佳评估工具和描述符的证据提供了契机,据此采用局部疗法,从而通过管理辅助因素(如pH值、体温调节、湿度、微生物负荷和敷料的粘附性)来增强愈合能力25,36。

可以观察到,当使用护理描述符时,与没有该描述符的检索相比,文献检索出的文章数量要少得多。尽管皮肤科护理在巴西是公认的专业,但不存在“皮肤科护理”或“皮肤科护士”或“皮肤病学护理”这样的描述词。因此,在检索研究时,使用了描述词“护理”和“护理评估”。

在不同级别的研究使用的命名中,我们可以观察到,都使用皮肤病学术语表来描述皮损,只在对组织的详细描述方面存在细微差异,例如渗出性糜烂。尽管护士撰写的研究报告很少,但可以观察到所使用的术语在专业类别之间没有差异25,29,36。

Sampaio和Rivitti3认为,皮损分类就像字母表;像字母组成单词一样,通过它们的组合,形成形态学符号,使我们能够“阅读”皮肤表现16,18。如结果所示,为皮损添加补充信息,有助于定义诊断假设、干预决策和愈合演变的监测。使用临床描述词来表征皮损或溃疡,使这些信息标准化,让卫生专业人员更容易理解。在表3中给出了与相应的基本皮损术语相关的PV皮损的例子。

皮损分为六组:颜色变化;水肿性隆起;实性隆起;液性隆起;厚度变化;损伤和修复。具体分类如下:

• 原发性:扁平斑点或黄斑(颜色变化);肿块(实性隆起);水肿性隆起(皮疹,水肿);液体内容物(液性隆起)。

• 继发性:稠度和厚度的变化(厚度变化); 或皮下组织受损(组织损伤和修复)16,18。

Pena等人27根据北美护理诊断协会(NANDA)、护理干预分类(NIC)和护理结果分类(NOC)提出了PV患者的诊断、干预和护理结果。对护理诊断“皮肤完整性受损”和“口腔粘膜受损”的分析或可推断,得出该诊断的护士评估不需要专门的评估,因为此类诊断的定义特征仅涉及皮肤或粘膜破裂,不需要评估伤口的厚度、组织类型或其他特征。在提议的NOC结果“愈合”中,其中肉芽组织是使用的指标之一,因此需要了解伤口可能存在的组织类型。提议的NIC干预“伤口护理”包括以该领域的特定知识、技能和准备为前提而决定采用的干预措施27。皮肤科护理作为一门专业,实践日渐增加,护士们对这些术语也越来越熟悉。

随着用于描述皮损的术语变得标准,无论是否与PV相关,专业人员之间的对话变得更加统一,避免了误解,也使得患者护理更加安全。然而,在伤口评估中,用于描述皮肤损伤的术语仍然存在很大差异,例如:腐肉和纤维蛋白; 湿性坏死和液化性坏死;干性坏死、“疤痕”和压力性损伤;肉芽组织、细胞外基质或活体组织。这类丰富的术语会让查阅记录的专业人士感到疑惑,通常会产生与术语登记人不同的解释。为了规范PV溃疡的登记,我们建议使用基本皮损术语:囊泡、水疱、糜烂、溃疡和全身性痂皮。

PV的慢性特征和皮肤表现剥夺了患者的保密权。通常,皮损可能会传染,影响患者社会和家庭关系,长期处于羞耻和孤独之中4。对于Brandão来说,因为他们旨在达到患者的整体平衡,护理行动变得富有成效。因此,人们在不断寻找替代方法来满足皮肤完整性受损患者的需求,也在开发促进愈合的技术,以及可以提高患者生活质量的方法4,27。

结论

本研究将PV研究中用于描述皮肤溃疡的术语与用于描述基本皮损的术语进行了比较。本研究表明,医生发表的出版物最为常见,其次是护士,且出版物中对皮损的描述缺乏统一性。

本研究表明,PV的皮肤变化可分为原发性皮损(颜色变化和积液)或继发性皮损(厚度和组织损失的变化)。鉴于皮肤病学术语广泛,继发于PV的皮损可表征为囊泡、水疱、糜烂、溃疡和全身性痂皮,以支持皮肤病学护理实践。

最后,得出的结论是,为了确定评估皮损的最佳方法以及用于改善护理的命名,需要在该领域进行更高水平的证据研究。

利益冲突声明

作者声明不存在利益冲突。

资金支持

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Mariana Takahashi Ferreira Costa*

Master’s Degree student, School of Nursing, Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil

Nurse member of Group for Prevention and Treatment of Wounds, de Emílio Ribas Infectology Institute, State Secretary of Health, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Email marianatakahashicosta@hotmail.com

Luiza Keiko Matsuka Oyafuso

Supervisor of Health Technical Team, Emílio Ribas Infectology Institute, State Secretary of Health, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Assistant Professor, ABC University Foundation

Mônica Antar Gamba

Associate Professor, School of Nursing, Federal University of São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Coordinator of the Dermatology Nursing Specialization Course, Mentor Professor at the Nursing Postgraduation Program

Kevin Y Woo PhD RN FAPWCA

Assistant Professor, School of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

Adjunct Research Professor, MClSc program, School of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, Western University

Wound Care Consultant, West Park Healthcare Centre

Clinical Web Editor, Advances in Skin and Wound Care

* Corresponding author

References

- Souza SR, Azulay-Abulafia L, Nascimento LV. Validation of the cutaneomucosal involvement index of pemphigus vulgaris for the clinical evaluation of patients with pemphigus vulgaris. An Bras Dermatol 2011;86(2):284–91.

- Hanauer L, Azulay-Abulafia L, Azulay DR, Azulay RD. Buloses. In: Azulay RD. Dermatology. 7th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2017. p. 242–245.

- Sampaio SAP, Rivitti EA. Dermatology. 4th ed. São Paulo: Artes Médicas; 2018. p.300–316.

- Brandão ES, Santos I, Lanzillotti RS. Reduction of pain in clients with autoimmune bullous dermatoses: evaluation by fuzzy logic. Online Braz J Nurs 2016 Dec; 15(4):675–682. Available from: http://www.objnursing.uff.br/index.php/nursing/article/view/546

- Shimizu T, Takebayashi T, Sato Y, Niizeki H, Aoyama Y, et al. Grading criteria for disease severity by Pemphigus Disease Area Index. J Dermatol 2014;41:969–973.

- Brandão ES, Santos I, Lanzillotti RS. Nursing care to comfort people with immunobullous dermatoses: evaluation by fuzzy logic. Rev Enferm UERJ, Rio de Janeiro 2018; 26:e32877.

- Mendes KD, Silveira RC, Galvão CM. Integrative literature review: a research method to incorporate evidence in health care and nursing. Text & Cont Enferm 2008;17(4):758–64.

- Galvão CM, Sawada NO, Mendes IAC. The search for the best evidence. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2003;37:43–50.

- Kulthanan K, Chularojanamontri L, Tuchinda P, AL Sirikudta W, Pinkaew S. Clinical course of pemphigus in Thai patients. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2011;29:161–8.

- Daniel BS, Hertl M, Werth VP, Eming R, Murrell DF. Severity score indexes for blistering diseases. Clin Dermatol 2012;30:108–113.

- Rahbar Z, Daneshpazhooh M, Mirshams-Shahshahani M, Esmaili N, Heidari K, et al. Pemphigus disease activity measurements: pemphigus disease area index, autoimmune bullous skin disorder intensity score and pemphigus vulgaris activity score. JAMA Dermatol 2014;150(3):266–72.

- Yoshifuku A, Fujii K, Kawahira H, Katsue H, Baba A, et al. Long-lasting localized pemphigus vulgaris without detectable serum autoantibodies against desmoglein 3 and desmoglein 1. Indian J Dermatol 2016;61(4):427.

- Zhou Q, Wang P, Zhang L, Wang B, Shi L, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris induced by 5-aminolaevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2017;156–158.

- Ormond M, McParland H, Donaldson ANA, Andiappan M, Cook RJ, Escudier M, Shirlaw PJ. An Oral Disease Severity Score validated for use in oral pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 2018;179(4):872–881.

- Mishra S, Joshi S. Anesthetic management of a case of retroperitoneal tumor with pemphigus vulgaris with multiple comorbid conditions. Egyptian J Anaesthes 2016;32(1):151–153.

- Rivitti EA. Dermatologia. 4th ed. São Paulo: Artes Médicas; 2018. p. 109–118.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Ellebrecht CT, Takahashi H, Yamagami J, Zillikens D, Payne AS, Amagai M. Pemphigus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017 May 11;3:17026. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.26. PMID: 28492232; PMCID: PMC5901732.

- Azulay RD. Dermatology. 7th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2017. p. 52–64.

- Yang F, Chen Z, Chen SA, Zhu Q, Wang L, et al. Skin ulcers infected with conditional pathogenic strains treated with local hydrogen water packing in two pemphigus vulgaris patients: case reports with follow-up for 2 months. Dermatol Ther 2019 Sep;32(5):e13027. doi:10.1111/dth.13027. Epub 2019 Jul 28. PMID: 31323168.

- Carmona Lorduy M, Porto Puerta I, Berrocal Torres S, Camacho Chaljub F. Manejo estomatológico y sistémico de pénfigo vulgar: reporte de un caso. Rev Cienc Salud 2018;16(2):357–367.

- Tsuruta D, Ishii N, Hashimoto T. Diagnosis and treatment of pemphigus. Immunother 2012;4(7):735.

- Benchikhi H, Nani S, Baybay H, et al. Pemphigus: use of the Japanese severity index in 56 Moroccan patients. Pan Afr Med J 2013;16:96.

- Suliman NM, Åstrøm AN, Ali RW, et al. Clinical and histological characterization of oral pemphigus lesions in patients with skin diseases: a cross sectional study from Sudan. BMC Oral Health 2013;13(1):66.

- Amagai M, Tanikawa A, Shimizu T, et al. Japanese guidelines for the management of pemphigus. J Dermatol 2014;41: 471–486.

- Brandão ES, Santos I, Lanzillotti RS, Ferreira AM, Gamba MA, et al. Nursing diagnoses in patients with immune-bullous dermatosis. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2016;24:e2766. doi:10.1590/1518-8345.0424.

- Kershenovich R, Hodak E, Mimouni D. Diagnosis and classification of pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:477–81.

- Pena SB, Guimarães HC, Bassoli SR, et al. Nursing diagnoses in pemphigus vulgaris: a case study. Int J Nurs Know 2013;24(3):176–179.

- Venugopal SS, Murrell DF. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus vulgaris. Dermatol Clin 2011;29:373–380.

- Brandão ES, Santos I. Evidences related to the care of people with pemphigus vulgaris: a challenge to nursing. Online Braz J Nurs 2013 Sept;12(1):162–77. Available from: http://www.objnursing.uff.br/index.php/nursing/article/view/3674/html.

- Eskiocak AH, Ozkesici B, Uzun S. Familial pemphigus vulgaris occurred in a father and son as the first confirmed cases. Case Rep Dermatol Med 2016;1653507. doi:10.1155/2016/1653507. Epub 2016 Jun 15. PMID: 27403352; PMCID: PMC4925942.

- Di Zenzo G, Amber KT, Sayar BS, Müller EJ, Borradori L. Immune response in pemphigus and beyond: progresses and emerging concepts. Semin Immunopathol 2016 Jan;38(1):57–74.

- Hammers CM, Stanley JR. Mechanisms of disease: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Annu Rev Pathol 2016;11:175–197.

- Mokhtari F, Matin M, Rajati F. Pemphigus vulgaris and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Res Med Sci 2016 Oct18;21:82.

- DiMarco, C. Pemphigus: pathogenesis to treatment. R I Med J 2016;99(12):28–31.

- Rangel, J. Pregnancy-associated ‘cutaneous type’ pemphigus vulgaris. Perm J 2016;20(1):e101-e102. doi:10.7812/TPP/15-059.

- Costa MTF, Oyafuso LKM, Costa IG, Gamba MA, Woo KY. The management of pemphigus ulcers: a challenge and learning opportunity for Brazilian nurses. WCET J 2016;36(2):14–20.

- Lee SH, Hong WJ, Kim SC. Analysis of serum cytokine profile in pemphigus. Ann Dermatol 2017;29(4), 438–445.

- Harman KE, Brown D, Exton LS, Groves RW, Hampton PJ, Mohd Mustapa MF, Buckley DA. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris 2017. Br J Dermatol 2017;177(5):1170–1201.

- Dmochowski M, Gornowicz-Porowska J, Bowszyc-Dmochowska M. Dew drops on spider web appearance: a newly named pattern of IgG4 deposition in pemphigus with direct immunofluorescence. Postȩpy Dermatol Alergol 2017;34(4):295.

- Wang M, Liang L, Li L, Han K, Li Q, Peng Y, Zeng K. Increased miR-424-5p expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with pemphigus. Mol Med Rep 2017;15(6):3479–3484.

- Kridin K, Zelber-Sagi S, Bergman R. Pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus: differences in epidemiology and mortality. Acta Derm Venereol 2017;97(8–9):1095–1099.

- Vinay K, Handa S, Khurana S, Agrawal S, De D. Dermatoscopy in diagnosis of cutaneous myiasis arising in pemphigus vulgaris lesions. Indian J Dermatol 2017;62(4):440.

- Jiménez-Zarazúa O, Guzmán-Ramírez A, Vélez-Ramírez LN, López-García JA, Casimiro-Guzmán L, Mondragón JD. A case of acute pemphigus vulgaris relapses associated with cocaine use and review of the literature. Dermatol Ther 2018;8(4):653–663.

- Seo JW, Park J, Lee J, Kim MY, Choi HJ, Jeong HJ, Kim WK. A case of pemphigus vulgaris associated with ulcerative colitis. Intest Res 2018;16(1):147.

- Ujiie I, Ujiie H, Iwata H, Shimizu H. Clinical and immunological features of pemphigus relapse. Br J Dermatol 2019 Jun;180(6):1498–1505. doi:10.1111/bjd.17591. Epub 2019 Mar 6. PMID: 30585310.

- Murrell D, Peña S, Joly P, Marinovic B, Hashimoto T, et al. Diagnosis and management of pemphigus: recommendations by an international panel of experts. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020 Mar;82(3):575–585.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.021. Epub 2018 Feb 10. PMID: 29438767; PMCID: PMC7313440.

- Sendrasoa FA, Ranaivo IM, Rakotoarisaona MF, Raharolahy O, Razanakoto NH, Andrianarison M, Rabenja FR. Pemphigus vulgaris as the first manifestation of multiple myeloma: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2018;12(1):255.

- Küçükoğlu R, Sun GP, Kılıç S. Polycyclic annular presentation of pemphigus vulgaris with an eosinophil predominance in two pregnant patients. Dermatol Online 2018;24(10).

- Feliciani C, Cozzani E, Marzano AV, Caproni M, Di Zenzo G, Calzavara-Pinton P, Lora V. Italian guidelines in pemphigus-adapted from the European Dermatology Forum (EDF) and European Academy of Dermatology and Venerology (EADV). G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2018;153(5):599–608.

- Porro A M, Hans Filho G, Santi CG. Consensus on the treatment of autoimmune bullous dermatoses: pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus: Brazilian Society of Dermatology. An Bras Dermatol 2019;94(2):20–32.

- Hattier G, Beggs S, Sahu J, Trufant J, Jones E. Koebner phenomenon: pemphigus vulgaris following Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Online J 2019;25(1).

- Badavanis G, Pasmatzi E, Kapranos N, Monastirli A, Constantinou P, Psaras G, Tsambaos D. Pemphigus vulgaris possibly associated with application of a tissue expander in a patient with Crohn’s disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 2019;28(4):173–176.

- Krammer S, Krammer C, Salzer S, Bağcı IS, French LE, Hartmann D. Recurrence of pemphigus vulgaris under nivolumab therapy. Front Med 2019;6:262.

- Bosseila M, Nabarawy EA, Latif MA, Doss S, ElKalioby M, Saleh MA. Scalp pemphigus vulgaris mimicking folliculitis decalvans: a case report. Dermatol Pract Concept 2019;9(3):215–17.

- Yavuz IH, Yavuz GO, Bayram I, Bilgili SG. Pemphigus in the eastern region of Turkey. Postȩpy Dermatol Alergol 2019;36(4):455–60.

- Sar-Pomian M, Rudnicka L, Olszewska M. The significance of scalp involvement in pemphigus: a literature review. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018: 6154397. doi:10,1155/2018/6154397

- Schmidt E, Kasperkiewic M, Joly P. Pemphigus. Lancet 2019;394(10201):882–894.

- Streifel AM, Wessman LL, Schultz BJ, Miller D, Pearson DR. Refractory mucositis associated with underlying follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the thymus: paraneoplastic pemphigus versus malignancy-exacerbated pemphigus vulgaris. JAAD Case Rep 2019;5(11):933.

- España A, Iranzo P, Herrero‐González J, Mascaro Jr JM, Suárez R. Ocular involvement in pemphigus vulgaris: a retrospective study of a large Spanish cohort. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2017;15(4):396–403.

- Lee EB, Ayoubi N, Albayram M, Kariyawasam V, Motaparthi K. Cerebral toxoplasmosis after rituximab for pemphigus vulgaris. JAAD Case Rep 2019;6(1):37–41. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.10.015. PMID: 31909136; PMCID: PMC6938870.

- Brandão E, Santos I, Carvalho M, Pereira SK. Nursing care evolution to the client with pemphigus: integrative literature review. Revista Enfermagem 2011;19:479–484.

- Zhang C, Goldscheider I, Ruzicka T, Sardy M. Pemphigus vulgaris persistently localized to the nose with local and systemic response to topical steroids. Acta Derm Venereol 2017;97(8–9):1136–1137.

- Pietkiewicz P, Gornowicz-Porowska J, Bartkiewicz P, Bowszyc-Dmochowska M, Dmochowski M. Reviewing putative industrial triggering in pemphigus: cluster of pemphigus in the area near the wastewater treatment plant. Postȩpy Dermatol Alergol 2017;34(3):185.

- Oliveira LB, Maruta CW, Miyamoto D, Salvadori FA, Santi CG, Aoki V, Duarte-Neto AN. Gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus disease in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris treated with corticosteroid and mycophenolate mofetil. Autops Case Reps 2017;7(1):23.

- Osipowicz K, Kowalewski C, Woźniak K. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and pemphigus vulgaris. Postȩpy Dermatol Alergol 2018;35(5):532.

- Lazzarotto A, Ferranti M, Meneguzzo A, Sacco G, Alaibac M. Persistent B lymphocyte depletion after an ultralow dose of rituximab for pemphigus vulgaris. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2018;28(5):347.

- Kiran KC, Madhukara J, Abraham A, Muralidharan S. Cutaneous bacteriological profile in patients with pemphigus. Indian J Dermatol 2018;63(4):301.

- Dube M, Takkar B, Asati D, Jain S. Anterior scleritis in a patient of pemphigus vulgaris while on immunosuppressive treatment. Indian J Dermatol 2019;64(6):499–500.