Volume 41 Number 4

Use of hydrocolloid protective sheets to protect skin against direct contact from body secretions

Nur Madalinah Tan, Josephine Ong, Feng Ying, Ong Ling and Catherine Loo

Keywords IAD, hydrocolloid, protective sheet, MASD, denuded

For referencing Tan NM et al. Use of hydrocolloid protective sheets to protect skin against direct contact from body secretions. WCET® Journal 2021;41(4):18-21

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.4.18-21

Submitted 26 April 2021

Accepted 18 July 2021

Abstract

Hydrocolloid protective sheets provide a moist favourable environment for wound healing and act as a barrier against exogenous bacteria. They do not adhere to the wound, only to the surrounding skin, and can provide more a more rapid wound healing environment, keeping newly healed skin intact and preventing breakdown of tissue. Hydrocolloid protective sheets do not traumatise the skin upon removal, reducing pain, and require fewer dressing changes as they may be left in place for several days at a time. They come in different sizes which can be custom-cut to fit the wound. Their use can also reduce the cost of care, length of stay in hospital and amount of care rendered by WOC nurses. The three case studies in this article describe how stomal therapy nurses approached the nursing management of denuded skin using hydrocolloid protective sheets on peristomal skin, the buttocks and perineal regions.

Introduction

MASD (moisture-associated skin damage) is caused by prolonged exposure to different sources of moisture. These include perspiration, urine output, faecal output, wound exudate, mucus, saliva, other secretions, and their contents. When excessive moisture, including its chemical content and mechanical factors such as friction and presence of pathogenic organisms, leads to inflammation of the skin, with or without erosion or secondary cutaneous infection, MASD occurs1.

Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) is one common form of MASD. IAD is a type of irritant dermatitis found in patients with faecal and/or urinary incontinence. It is also known as perineal dermatitis or nappy/diaper rash. Sometimes it is associated with bullae, erosion or a secondary cutaneous infection2,3.

Stomal prolapse, where the intestine telescopes through the stoma, is a common postoperative complication and is often associated with loop colostomies. Common reasons for stomal prolapse are surgical technique, obesity, increased abdominal pressure, and creation of the stoma outside of the abdominus rectus muscle. Prolapsed stomas can contribute to leakage around the stoma, leading to significant skin irritation or IAD4,5.

Persistent exposure to large amounts of moisture will cause the skin to soften, swell, and become very wrinkled1,3. This will damage the skin and reduce skin barrier function, leading to skin erosion, causing the patient to suffer pain, trauma, emotional stress, and financial strain1,4,6. Patients will generally report experiencing pain, burning or itching because of skin damage; this may also involve frequent trips to visit nurses or long-term stays in hospital. Activities of daily living may also be affected, and there may be financial constraints due to not being able to work and the high cost of expenses and travelling6.

The general principles to prevent and treat MASD and IAD are to use a structured skincare regimen using products to remove excess moisture from the skin, and therefore protecting the skin from infection and managing the source of moisture3. As such, patients at high risk for developing MASD and IAD require complications to be minimised when exhibiting symptoms by monitoring the wound area routinely for changes in skin condition, managing exudate with appropriate dressings for proper absorbency, and applying a skin barrier or skin protectant to the peristomal / periwound skin when appropriate1,2,7,8. The management of stomal prolapses is based on individual patient assessment and many include local reduction of the prolapse, surgical revision, re-evaluation of the ostomy appliance to fit the size and shape of the stoma, and the use of a hernia support belt encompassing a prolapse strap4.

Hydrocolloid protective sheets contain CMC (carboxymethyl-cellulose), pectin or gelatin combined with adhesive and tackifiers applied to polyurethane foam or film carrier to create an absorbent, self-adhesive sheet9. This provides an occlusive bacterial and viral barrier, reducing the risk of cross infection, lowering the wound pH, reducing bacteria proliferation, maintaining moisture at the wound bed, enhancing epithelisation and lower levels of pain, and preventing desiccation of the wound bed, therefore providing a moist wound healing environment9.

Hydrocolloid protective sheets can be used on a wide range of low to moderate exudating wounds and on a variety of wound shapes and sizes. They are simple to apply and can be used under the stoma wafer or directly on the denuded skin in the perineal, groin and sacral regions. They absorb moisture, minimising the risk of skin to be denuded, therefore further reducing contact with effluent and allowing the skin to heal if there is a previous skin issue. They are also good for skins that have irritation and allergies9. These sheets come in two sizes in my organisation and are not to be used for extended wear. They can also be used over other things like barrier rings and ostomy powder.

The sheets can be used in addition to a crusting or layering skin protection method which also uses skin barrier powder and a skin barrier spray. The skin barrier powder helps to absorb moisture and dries the wound as well as provides a seal. The skin barrier spray is then used to seal the powder to the skin before the protective sheets are placed over the top. This action must be repeated three times to be effective. This method was taught by the WOCN curriculum and passed down to peers4.

Case studies

Case study 1

Patient overview

A 61-year-old Chinese male patient underwent relook laparotomy, washout, decompression of small bowel and double barrel ileocolostomy creation on 11 February 2019. The patient and wife were taught how to manage the changing of the wafer during his stay in hospital and his outpatient visits to the colorectal nurse. He also had two home visits to ensure his competency in ostomy care.

From July to October 2019 the patient visited the outpatient clinic for a prolapsed stoma (distal loop prolapsed approximately 10cm, proximal loop prolapsed approximately 3cm) which was reducible to skin level. The patient was advised to use a hernia support belt to minimise the frequency of incidents of the stoma prolapsing. The peristomal skin was still intact.

The long-term operative plan was for stoma reversal in October but during his visit to the surgeon it was noted the ostomy appliance had obviously been leaking for sometime. The patient was re-referred to the colorectal nurse for review of the leaking appliance and treatment of denuded skin before his surgery.

Problem

On review, the patient was using a poorly fitted two-piece system and severe leakage was observed, yet, while the patient reported frequent leakage, he said he was able to manage. However, on assessment, it was observed to be more severe than described. He claimed that he was unable to change his appliance promptly as he did not bring a spare appliance during his clinic visit (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Case study 1: Day 1, 1 October 2019 (photos@Madalinah 2020)

Nursing intervention

During his first visit, the skin was cleansed with a non-rinse skin cleanser to restore the pH balance of the skin. The stoma was reduced to relieve tension and facilitate pouching and management. Ostomy powder was applied to absorb moisture and a skin barrier spray was used for enhanced skin protection. The patient expressed that he was comfortable with using a two-piece system despite being advised that the plastic flange may injure his stoma. A protective skin barrier was applied over the denuded skin ensuring a margin 1/3 above and 2/3 below the abdomen. The patient was advised to continue using the hernia support belt. On Day 4 there were signs of skin epithelisation (Figure 2). By Day 8, the skin was fully epithelised (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Case study 1: Day 4, 4 October 2019 (photos@Madalinah 2020)

Figure 3. Case study 1: Day 8, 8 October 2019 (photos@Madalinah 2020)

Case study 2

Patient overview

A 70-year-old female was admitted for IAD with denuded skin over her right lower buttock, perianal to bilateral labial majora. She was non-communicative; her son was her main caregiver. The patient was bed-bound, on nasogastric tube feeding and had an in-dwelling catheter.

Problem

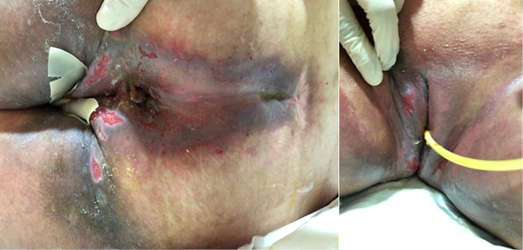

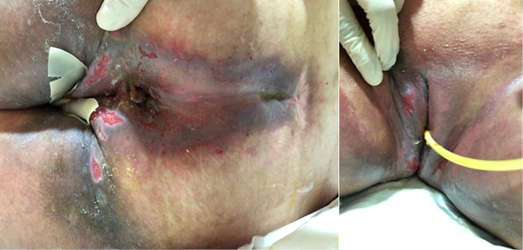

The patient was referred on 24 September 2019 (Day 1). On assessment it was noted there were healed scars from previous episodes of impaired skin integrity. At that time, the tissue was erythematous and weeping and her skin temperature was warm to touch (Figure 4). The patient was observed to be teary and agitated.

Figure 4. Case study 2: Day 1, 24 September 2019 (photos@Ong Ling/Catherine 2020)

Nursing intervention

Normal saline 0.9% was used to cleanse the wound; ostomy powder and a skin barrier spray were used to protect the skin by the crusting method and a hydrocolloid protective sheet was used to then protect the skin. It was recommended to nurses on the ward that they continued to wash the vagina area at every nappy change for good perianal hygiene and to ensure frequent turning to offload pressure. Skin cleansing was done to the buttock and perineal areas using a non-rinse skin cleanser, crusting with ostomy powder, and a skin barrier spray. A hydrocolloid protective sheet was applied to the bilateral groin, bilateral labial majora and perianal area. On 27 September (Day 3), skin epithelisation was observed, and the skin temperature was cool to the touch (Figure 5). Further improvement could be seen on Day 6 (Figure 6); the patient was discharged on 4 October once the skin had fully epithelised over.

Figure 5. Case study 2: Day 3, 27 September 2019 (photos@Ong Ling/Catherine 2020)

Figure 6. Case study 2: Day 6, 30 September 2019 (photos@Ong Ling/Catherine 2020)

Case study 3

Patient overview

The patient was an 86-year-old Chinese female patient with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and cataracts; her maid was the main caregiver at home. She had had a laparoscopic appendicectomy and a robotic assisted laparoscopic ultra low anterior resection and defunctioning ileostomy created in May 2018. She was scheduled for a planned elective admission for laparoscopic Hartmann’s reversal on 24 February 2019; however, the patient had watery, non-bloody stool 3–4 times per day 2 weeks prior to admission.

Problem

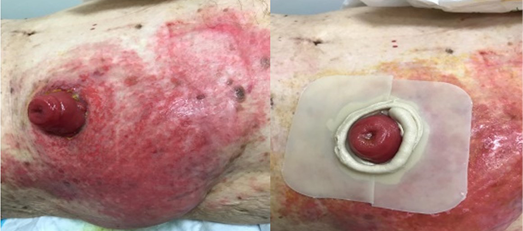

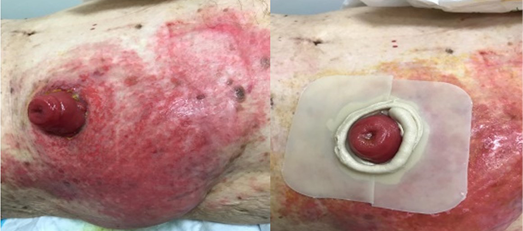

On assessment at the outpatient clinic, gross erythema over the left abdomen was noted; the skin was also weepy and denuded, the ostomy appliance was reinforced with TegadermTM, and the patient was also using nappies. The skin looked like a mixture of contact dermatitis and fungal infection (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Case study 3: Day 1, 10 February 2019 (photos@Madalinah 2020)

Nursing intervention

It was recommended by the stomal therapy nurses to discontinue the use of nappies and TegadermTM, and to cleanse the skin with non-rinse skin cleanser, paint with povidone iodine, protect with ostomy powder and skin barrier spray by the crusting method. A sheet of protective hydrocolloid was cut to the size and shape of the stoma and placed around the stoma to protect the immediate peri-stomal skin (Figure 7).

On 15 February 2019 (Day 5) the patient returned to the outpatient clinic for review; the skin was observed to have dried up with scabs, was cool to touch, and was not weeping. A protective hydrocolloid sheet was reapplied after the skin care regimen described above (Figure 8). On 22 February 2019 (Day 12), the patient’s skin had healed significantly with only light erythema present with no signs of previous scars within the healed tissue (Figure 9). During the remainder of her admission the protective hydrocolloid sheet was to protect the peristomal skin. The patient was discharged on 24 February 2019 and a protective sheet was still used to protect the skin until her elective admission.

Figure 8. Case study 3: Day 5, 15 February 2019 (photos@Madalinah 2020)

Figure 9. Case study 3: Day 12, 22 February 2019 (photos@Madalinah 2020)

Conclusion

The maintenance of skin integrity provides a foundation for long-term success in the rehabilitation of patients with skin issues. The use of hydrocolloid skin barriers provides a moist environment which allows the body enzymes to improve healing as they do not stick to the skin. The authors have had positive experiences using these, as shown by the three case studies shared here, but they are not favourable for wounds with heavy exudate or sinus tracts, or when infection is present. There are two sizes available in our hospital and they are self-adhering, making them easy to use for various body areas. However, the edges may curl or roll; that is why the authors use micropore tape as reinforcement. Frequency of change can vary from 3–7 days depending on the amount of exudate and on manufacturers’ guidelines. With ongoing use for selected patients, the authors are sure a positive result will be achieved showing similar benefits.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

使用水胶体保护贴以避免皮肤直接接触身体分泌物

Nur Madalinah Tan, Josephine Ong, Feng Ying, Ong Ling and Catherine Loo

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.4.18-21

摘要

水胶体保护贴为伤口愈合提供了湿润的有利环境,并可作为抵御外源性细菌的屏障。它们不会粘附在伤口上,只会粘附在周围皮肤上,可以提供更加快速的伤口愈合环境,使新愈合的皮肤保持完整,并防止组织破裂。去除水胶体保护贴时不会对皮肤造成损伤,可减少疼痛,且所需敷料次数较少,因为它们可以一次留置数天。它们有不同的尺寸,可以进行定制切割以适合伤口尺寸。使用水胶体保护贴还可降低护理成本,缩短住院时间,以及减少WOC护士提供的护理量。本文中的三个案例研究描述了造口治疗护士如何使用水胶体保护贴对造口周围皮肤、臀部和会阴区剥脱的皮肤进行护理管理。

引言

MASD(潮湿环境相关性皮损)是由于长期暴露于不同的水分来源而引起的。包括汗液、尿量、排便、伤口渗出液、粘液、唾液、其他分泌物及其内容物。当水分(包括其化学成分和机械因素(如摩擦和病原微生物的存在))过多时,会导致皮肤炎症(伴有或不伴有糜烂或继发性皮肤感染时),发生MASD1。

失禁相关皮炎(IAD)是MASD的一种常见形式。IAD是一种刺激性皮炎,见于大小便失禁患者。其还被称为会阴部皮炎或尿布疹。有时还伴有大疱、糜烂或继发性皮肤感染2,3。

造口脱垂(肠通过造口处突出)是一种常见的术后并发症,通常与环形结肠造口术相关。造口脱垂的常见原因是手术技术、肥胖、腹压升高以及在腹直肌外形成造口。脱垂的造口会导致造口周围渗漏,导致严重的皮肤刺激或IAD

4,5。

持续暴露在大量水分下会导致皮肤软化、肿胀,并产生大量皱纹1,3。这将损害皮肤,降低皮肤屏障功能,导致皮肤糜烂,导致患者遭受疼痛、创伤、情绪压力和经济负担1,4,6。患者通常报告称,因为皮肤损伤而出现疼痛、烧灼感或瘙痒;这也可能包括经常去访视护士或长期住院。日常生活活动也可能受到影响,并可能因无法工作以及高昂的开支和差旅费用而导致资金不足6。

预防和治疗MASD和IAD的一般原则是使用结构化的护肤方案,使用产品去除皮肤中多余的水分,从而保护皮肤免受感染并管理水分来源3。因此,发生MASD和IAD风险较高的患者在出现症状时,需要通过定期监测伤口部位的皮肤状况变化,使用适当的敷料处理渗出液,以达到适当的吸收效果,以及在适当时在造口周围/伤口周围皮肤使用皮肤屏障或皮肤防护剂1,2,7,8。尽量减少并发症。基于个体患者评估进行造口脱垂管理,许多情况下包括局部减少脱垂、手术修复、重新评估造口装置以适应造口的大小和形状,以及使用包含脱垂带的疝气支撑带4。

水胶体保护贴包含CMC(羧甲基纤维素)、果胶或明胶,与粘合剂和增粘剂相结合,应用于聚氨酯泡沫或膜形载体,形成一种易吸收的自粘贴9。这提供了一个封闭的细菌和病毒屏障,降低交叉感染的风险,降低伤口pH值,减少细菌增殖,保持伤口床水分,增强上皮化并降低疼痛水平,并防止伤口床干燥,因此提供了一个潮湿的伤口愈合环境9。

水胶体保护贴可用于各种低至中度渗出性伤口以及各种形状和大小的伤口。其用法简单,可以在造口片下使用,也可以直接在会阴、腹股沟和骶骨区剥脱的皮肤上使用。它们可吸收水分,将皮肤剥脱的风险降至最低,从而进一步减少与渗出液的接触,如果先前有皮肤问题,可以让皮肤愈合。同时也适用于出现刺激和过敏的皮肤9。在我们医院,这种敷料贴有两种尺寸,不能用于长期佩戴。它们也可以用于其他产品,如屏障环和造口护肤粉。

除了使用皮肤保护粉和皮肤保护喷剂的结痂或分层皮肤保护方法外,还可以使用这些敷料贴。皮肤保护粉有助于吸收水分,使伤口干燥,并进行密封。然后使用皮肤保护喷剂将粉末密封在皮肤上,再将保护贴覆盖在上面。此操作必须重复三次才会生效。这一方法由WOCN课程所教授,并传给与同行4。

病例研究

病例研究1

患者概述

一例61岁的中国男性患者于2019年2月11日接受了重看开腹手术、洗脱、小肠减压和双管回肠结肠吻合术。在患者住院以及在门诊访视结直肠护士期间,指导该患者和其妻子如何更换晶片。他还进行了两次家访,以确保其具备造口护理能力。

2019年7月至10月,该患者因可缩小至皮肤水平的脱垂造口(远端环脱垂约10 cm,近端环脱垂约

3 cm)而到门诊就诊。建议该患者使用疝气支撑带,以尽量降低造口脱垂的频率。造口周围皮肤仍然完整。

长期手术计划为在10月进行造口还纳术,但在该患者访视外科医生时,发现造口装置出现渗漏显然已有一段时间。该患者在手术前被再次转诊到结直肠护士处,以检查装置渗漏情况并治疗剥脱的皮肤。

问题

经审查,该患者使用的是一个不合适的两件式系统,并观察到严重渗漏,然而尽管该患者报告称频繁渗漏,但其说其能够处理。然而在评估中观察到情况比描述的更加严重。他声称,由于其在就诊期间未携带备用装置,所以无法及时更换装置

(图1)。

图1.病例研究1:2019年10月1日第1天(照片@Madalinah 2020)

护理干预

在其第一次访视期间,使用免冲洗皮肤清洁剂清洁皮肤,以恢复皮肤的pH平衡。缩小造口以缓解张力,并促进造口和管理。使用造口护肤粉吸收水分,并使用皮肤保护喷剂增强皮肤保护。该患者表示,尽管被告知塑料法兰可能会损伤其造口,但他还是觉得使用两件式系统比较舒适。在剥脱的皮肤上涂上保护性皮肤屏障产品,确保覆盖腹部上方1/3和下方2/3的边缘。建议该患者继续使用疝气支撑带。第4天出现皮肤上皮化迹象(图2)。到第8天,皮肤完全上皮化(图3)。

图2.病例研究1:2019年10月4日第4天(照片@Madalinah 2020)

图3.病例研究1:2019年10月8日第8天(照片@Madalinah 2020)

病例研究2

患者概述

一例70岁的女性患者因IAD入院,其右下臀部、肛周至双侧大阴唇处皮肤剥脱。她不善于交流;其儿子是其主要护理者。该患者卧床不起,使用鼻胃管进食,并有一根留置尿管。

问题

该患者于2019年9月24日(第1天)转诊。经评估发现,存在因先前皮肤完整性受损而产生的愈合疤痕。当时,组织红肿并在渗液,患者皮肤温度很高(图4)。观察到该患者泪流满面,躁动不安。

图4.病例研究2:2019年9月24日第1天(照片@Ong Ling/Catherine 2020)

护理干预

使用0.9%生理盐水清洗伤口;使用造口护肤粉和皮肤保护喷剂通过结痂方法保护皮肤,然后使用水胶体保护贴保护皮肤。建议病房护士在每次更换尿布时继续清洗阴道部位,以保持肛周卫生良好,并确保患者经常翻身以减轻压力。使用免冲洗皮肤清洁剂对臀部和会阴区域进行皮肤清洁,用造口护肤粉和皮肤保护喷剂结痂。在双侧腹股沟、双侧大阴唇和肛周区域施用水胶体保护贴。9月27日(第3天),观察到皮肤上皮化,皮肤温度很低(图5)。在第6天可以看到已进一步改善(图6);患者于10月4日皮肤完全上皮化后出院。

图5.病例研究2:2019年9月27日第3天(照片@Ong Ling/Catherine 2020

图6.病例研究2:2019年9月30日第6天(照片@Ong Ling/Catherine 2020)

病例研究3

患者概述

该患者为一例86岁中国女性患者,既往有高血压、高脂血症和白内障病史;其女佣是家里的主要护理者。她于2018年5月进行了腹腔镜阑尾切除术和机器人直肠癌超低位前切除术以及预防性回肠造口术。她计划于2019年2月24日按计划择期入院接受腹腔镜下的Hartmann术;然而,患者在入院前2周每天出现3-4次水样、非血便。

问题

在门诊进行评估时,发现左腹部有严重红斑;同时皮肤渗液和剥脱,造口装置用TegadermTM加固,且该患者还在使用尿布。皮肤看似同时出现了接触性皮炎和真菌感染(图7)。

图7.病例研究3:2019年2月10日第1天(照片@Madalinah 2020)

护理干预

造口治疗护士建议停止使用尿布和TegadermTM,并使用免冲洗皮肤清洁剂清洁皮肤,用聚维酮碘涂抹,使用造口护肤粉和皮肤保护喷剂通过结痂方法保护皮肤.将一贴保护性水胶体切割成造口的大小和形状,并覆盖在造口周围,以保护紧邻的造口周围皮肤(图7)。

2019年2月15日(第5天),该患者返回门诊进行复查;观察到皮肤已经干涸结痂,摸起来很凉,未出现渗液。在进行上述皮肤护理方案后,再次施用水胶体保护贴(图8)。2019年2月22日(第12天),该患者皮肤已明显愈合,仅存在轻度红斑,愈合组织内没有先前疤痕的迹象(图9)。在其入院剩余时间里,使用保护性水胶体贴保护造口周围皮肤。该患者于2019年2月24日出院,在其择期入院前仍使用保护贴保护皮肤。

图8.病例研究3:2019年2月15日第5天(照片@Madalinah 2020)

图9.病例研究3:2019年2月22日第12天(照片@Madalinah 2020)

结论

维护皮肤完整性为皮肤问题患者的长期成功康复提供了基础。使用水胶体皮肤屏障提供了一个潮湿的环境,使身体的酶能够改善愈合,因为它们不会粘附在皮肤上。作者在使用这些产品方面有着积极的经验,如本文分享的三个病例研究所示,但这些产品不适用于出现大量渗出液或窦道的伤口,或存在感染时。我们医院有两种尺寸可供选择,它们是自粘性的,便于用于身体各个部位。但是边缘可能会卷曲或滚动;这就是作者使用微孔胶带加固的原因。更换频率可能在3-7天不等,取决于渗出液的量和制造商指南。随着受访患者持续使用,作者确信将取得积极的结果,显示出类似的受益。

利益冲突声明

作者声明无利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Nur Madalinah Tan* ET, RN, WOCNC Singapore

Colorectal Nurse, Specialty Nursing, Changi General Hospital, 2,

Simei Street 3, Singapore 529889

Email Madalinah_tan@cgh.com.sg

Josephine Ong RN

Colorectal Nurse, Specialty Nursing, Changi General Hospital, Singapore

Feng Ying RN

Hepatopancreatobiliary Nurse, Specialty Nursing, Changi General Hospital, Singapore

Ong Ling ET, RN

Wound Healing Society Singapore, Wound Care Nurse, Specialty Nursing, Changi General Hospital, Singapore

Catherine Loo ET, RN

Wound Care Nurse, Specialty Nursing, Changi General Hospital, Singapore

* Corresponding author

References

- Gray M, Black JM, Baharestani MM, Bliss DZ, Colwell JC, Goldberg M, Kennedy-Evans KL, Logan S, Ratliff CR. Moisture-associated skin damage: overview and pathophysiology. J WOCN 2011 May–Jun;38(3):233-41. doi:10.1097/WON.0b013e318215f798.

- Yates A. Incontinence-associated dermatitis 1: risk factors for skin damage. Nursing Times 2020;116:3,46–50.

- Ousey K, O’Connor L. Incontinence-associated dermatitis made easy. London: Wounds UK; 2017. Available from: www.wounds-uk.com

- Pitman. Stoma complications. In: Carmel JE, Colwell JC, Goldberg MT, editors. Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society core curriculum ostomy management. China: Wolters Kluwer; 2016. p. 191–200.

- Colwell JC, Ratcliff CR, Goldberg M, et al. MASD part 3: peristomal moisture-associated dermatitis and periwound moisture-associated dermatitis: a consensus. J WOCN 2011;38(5):541–53.

- Chabal LO, Prentice JL, Ayello EA. Practice implications from the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline 2020. Adv Skin Wound Care 2021;34:293–300. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000742888.02025.d6

- Beeckman D, Van den Bussche K, Alves P, Beele H, Ciprandi G, Coyer F, et al. The Ghent Global IAD Categorisation Tool (GLOBIAD). Skin Integrity Research Group (SKINT), Ghent University; 2017. Available from: https://users.ugent.be/~dibeeckm/globiadnl/nlv1.0.pdf

- Zulkowski K. Understanding moisture-associated skin damage, medical adhesive-related skin injuries, and skin tears. Adv Skin Wound Care 2017;30(8):372–38.

- Ousey K, Cook L, Young T, Fowler A. Hydrocolloids in practice made easy. Wounds UK 2012;8(1):1–6.