Volume 42 Number 1

Wound bed preparation

R Gary Sibbald, James A Elliott, Reneeka Persaud-Jaimangal, Laurie Goodman, David G Armstrong, Catherine Harley, Sunita Coelho, Nancy Xi, Robyn Evans, Dieter O Mayer, Xiu Zhao, Jolene Heil, Bharat Kotru, Barbara Delmore, Kimberly LeBlanc, Elizabeth A Ayello, Hiske Smart, Gulnaz Tariq, Afsaneh Alavi and Ranjani Somayaji

Keywords debridement, Exudate, wound bed preparation, wound healing, Infection, Inflammation, Pain, healability, moisture management, paradigm, patient-centred care

For referencing Sibbald GR et al. Wound bed preparation. WCET® Journal 2022;42(1):16-28

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.42.1.16-28

Submitted November 2020

Accepted February 2021

Abstract

The wound bed preparation (WBP) model is a paradigm to optimise chronic wound treatment. This holistic approach examines the treatment of the cause and patient-centred concerns to determine if a wound is healable, a maintenance wound, or non-healable (palliative). For healable wounds (with adequate blood supply and a cause that can be corrected), moisture balance is indicated along with active debridement and control of local infection or abnormal inflammation. In maintenance and non-healable wounds, the emphasis changes to patient comfort, relieving pain, controlling odour, preventing infection by decreasing bacteria on the wound surface, conservative debridement of slough, and moisture management including exudate control.

In this fourth revision, the authors have re-formulated the WBP model into 10 statements. This article will focus on the literature in the last 5 years or new interpretations of older literature. This process is designed to facilitate knowledge translation in the clinical setting and improve patient outcomes at a lower cost to the healthcare system.

© R Gary Sibbald. Previously published in Advances in Skin & Wound Care April 2021 and published here with the kind permission of Gary Sibbald (see Editorial)

Introduction

Wound bed preparation (WBP) is a structured approach to wound healing. Now entering its third decade of widespread use, the WBP paradigm was first published in 2000, with periodic updates in 2003, 2006, 2011, 2015 and now 2021. This article lists 10 statements formulated from previous versions of the WBP model, reports the results of a survey of current wound care practitioners conducted to achieve consensus on those principles, and summarises related evidence supporting each statement. This latest iteration features the following key changes:

- The use of an audible handheld Doppler (AHHD) of dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial artery as an alternative to the traditional ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI) for the clinical assessment of adequate arterial supply to heal and ability to apply compression therapy safely.

- Updated approaches to topical and systemic pain management for persons with wounds.

- An update on the management of maintenance and non-healable wounds.

- New enablers to facilitate knowledge dissemination for the other eight components of WBP.

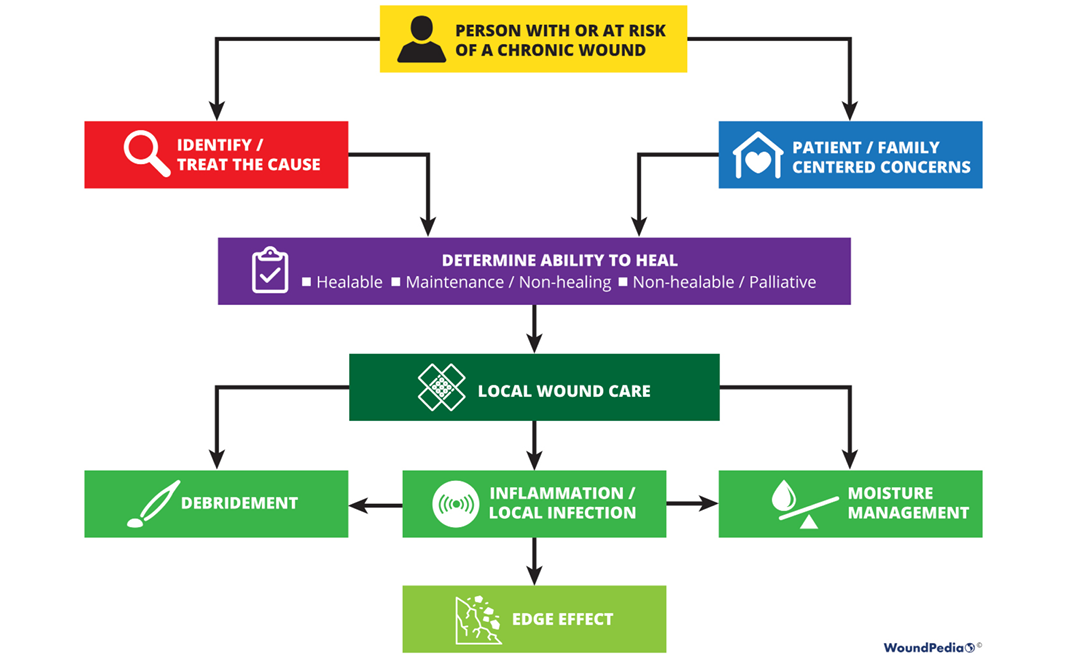

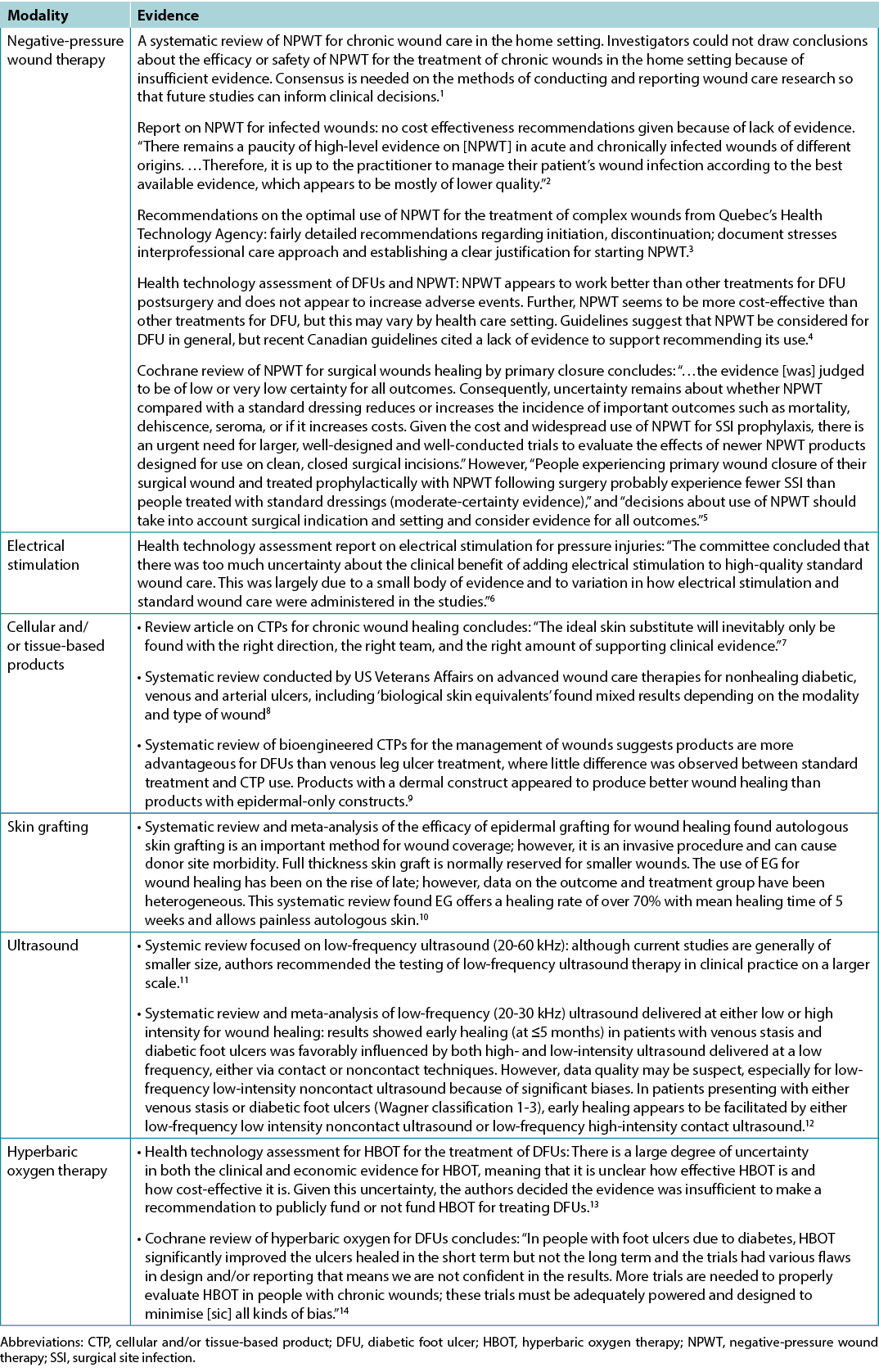

Sackett and colleagues1 define evidence-based medicine as “integrating individual clinical expertise and the best external evidence”. Specifically, the three pillars of evidence-based medicine include scientific evidence, expert knowledge and patient preference; these are incorporated into the 10 statements included in the WBP 2021 paradigm (Figure 1).

Figure 1. WBP paradigm 2021 (©WoundPedia 2021)

Engagement of stakeholders in the evaluation process has been suggested as a strategy to bridge the “translation gap”2. Wound healing experts and active wound care practitioners were involved in the evaluation process of the 10 statements to enhance dissemination3,4. Further, the authors conducted a comprehensive search of recent literature, findings from which are included throughout this document. Finally, WBP 2021 includes a set of enablers for translation of knowledge into practice. These enablers are tools intended for use at the point of care to enhance implementation of the WBP statements.

Methods

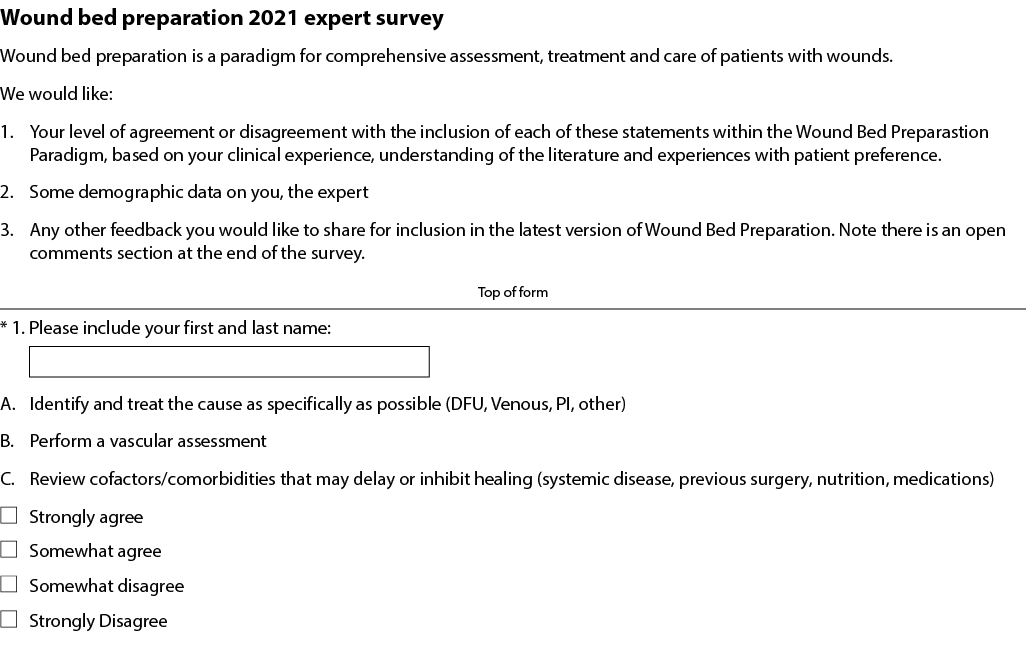

Ten statements were initially developed by the authors based on previous versions of the WBP paradigm and informed by a review of recent literature. These initial statements were used to create an online survey and a set of visual ‘enablers’ that added further detail to each statement. Some of the 10 statements were further subdivided into lettered substatements (1A, 1B, 1C etc). The survey was iteratively reviewed and assessed for face and content validity by a total of twenty developers and external wound care stakeholders over a 6-month period and finalised for send-out.

The survey (Supplementary Table 1, https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal) was sent to a purposive sample of wound healing key opinion leaders (KOLs). The authors chose at least one KOL from each continent and from each key wound healing profession – physicians, nurses and allied health practitioners. For each statement, respondents stated whether they strongly agreed, somewhat agreed, somewhat disagreed or strongly disagreed. The desired consensus level for statement acceptance was 80% of respondents somewhat agreeing or strongly agreeing with each statement. The survey was also sent to graduating classes of the International Interprofessional Wound Care Courses (IIWCC) in Abu Dhabi and Canada. The respondents were completing a year-long KOL training with a certificate of completion. Most (but not all) class members voluntarily participated.

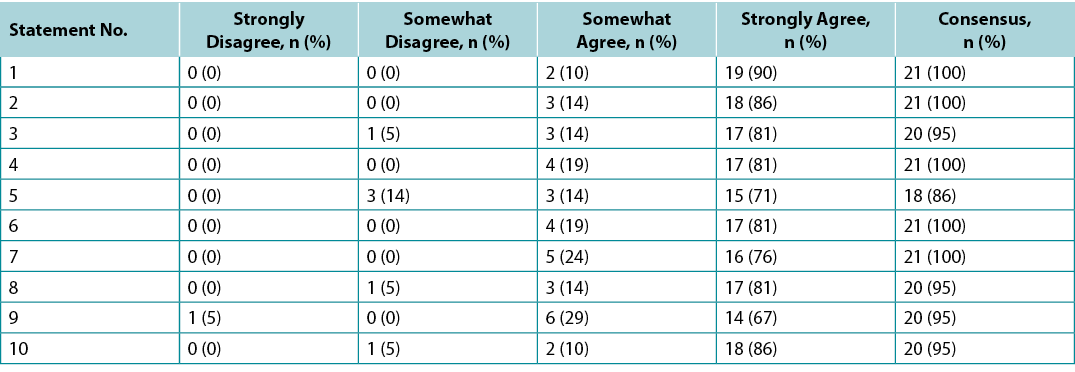

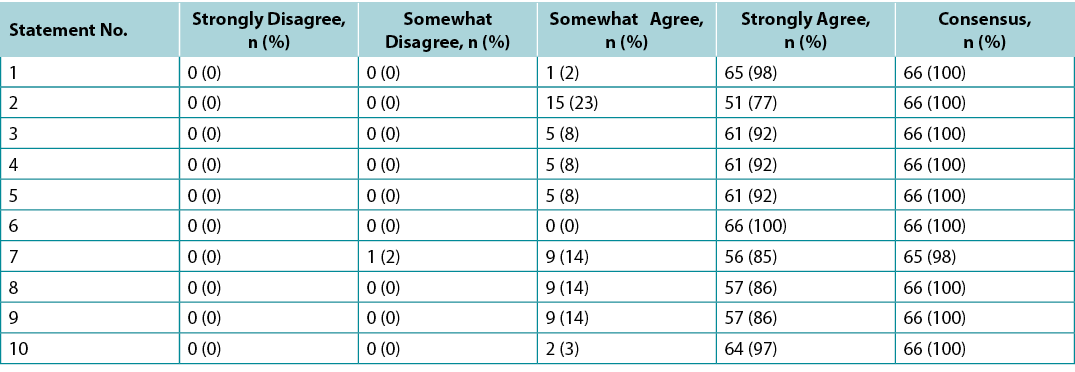

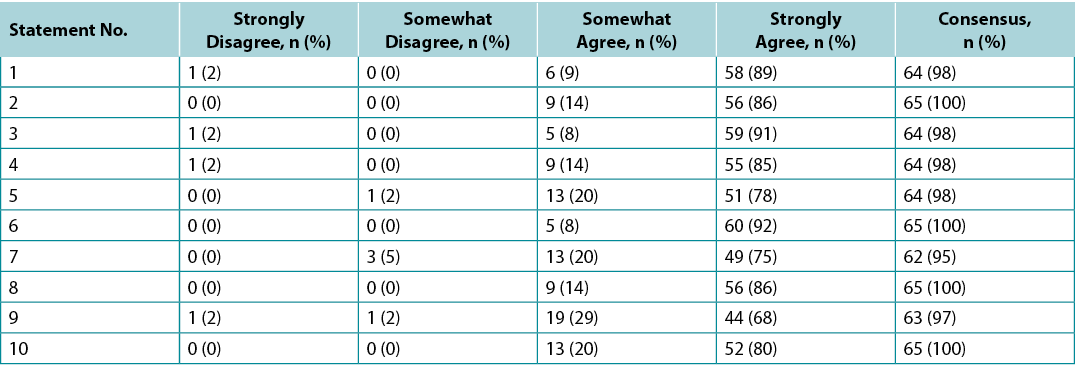

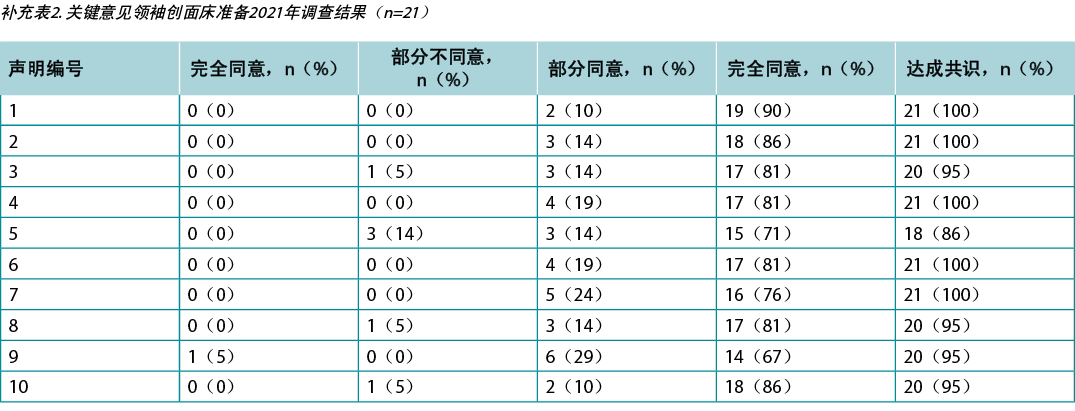

Results

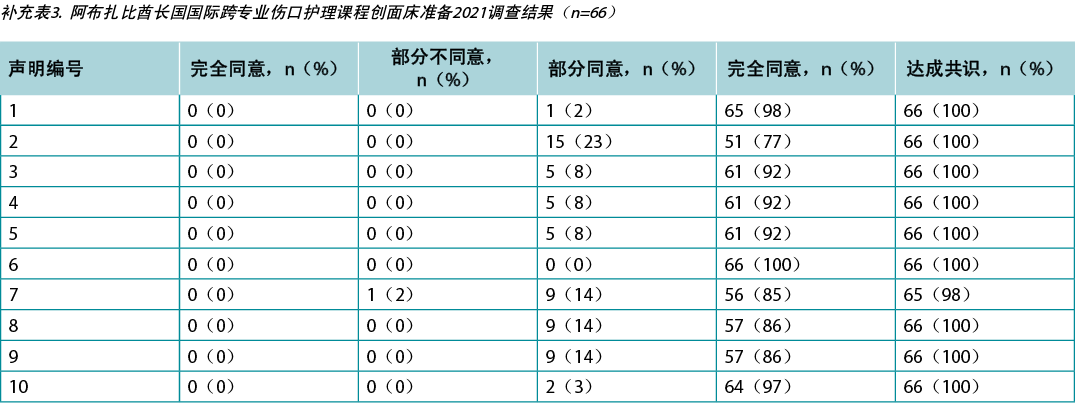

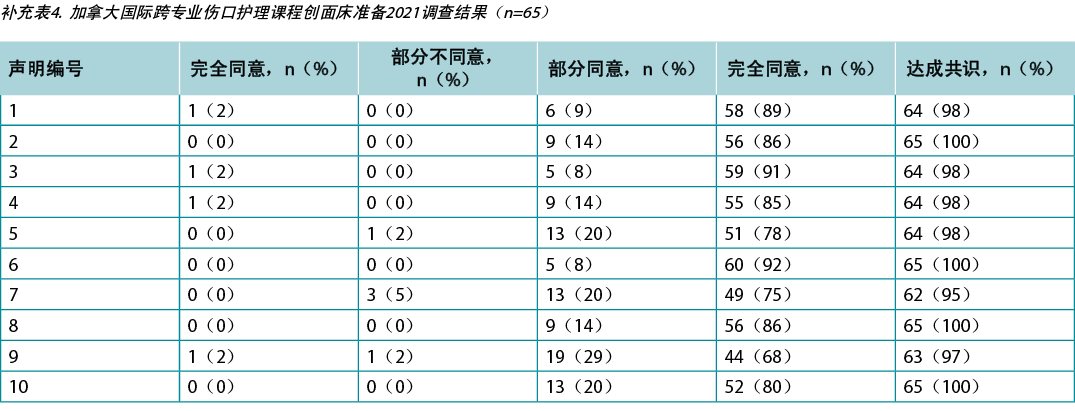

Surveys were requested from KOLs (n=21) and students of the IIWCC 2020 class of Abu Dhabi (n=66) and Canada (n=65). The 21 KOLs’ consensus for each statement was between 86–100% (Supplementary Table 2). The 2020 IIWCC class in Abu Dhabi demonstrated 98–100% consensus (Supplementary Table 3) and the class in Canada reached an 85–100% consensus (Supplementary Table 4, all tables at https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal). The most notable result, beyond the generally high level of consensus, was the comparatively low KOL agreement with Statement 5 (still 86%; discussed later) and the high agreement with all statements among the Abu Dhabi students. This could be because the students in Abu Dhabi (from several West Asian countries and a small number of students from Africa) had less wound care experience than the other groups.

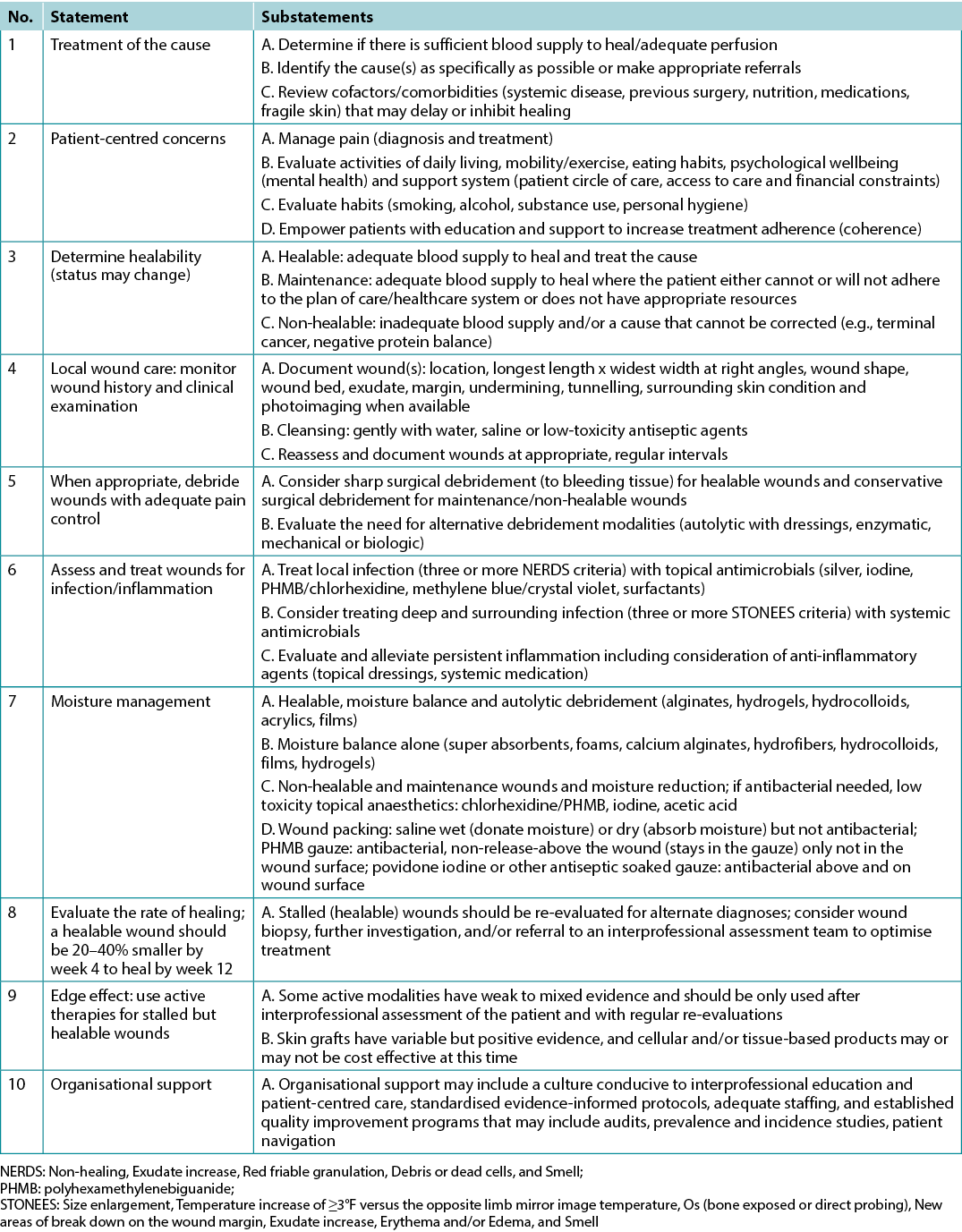

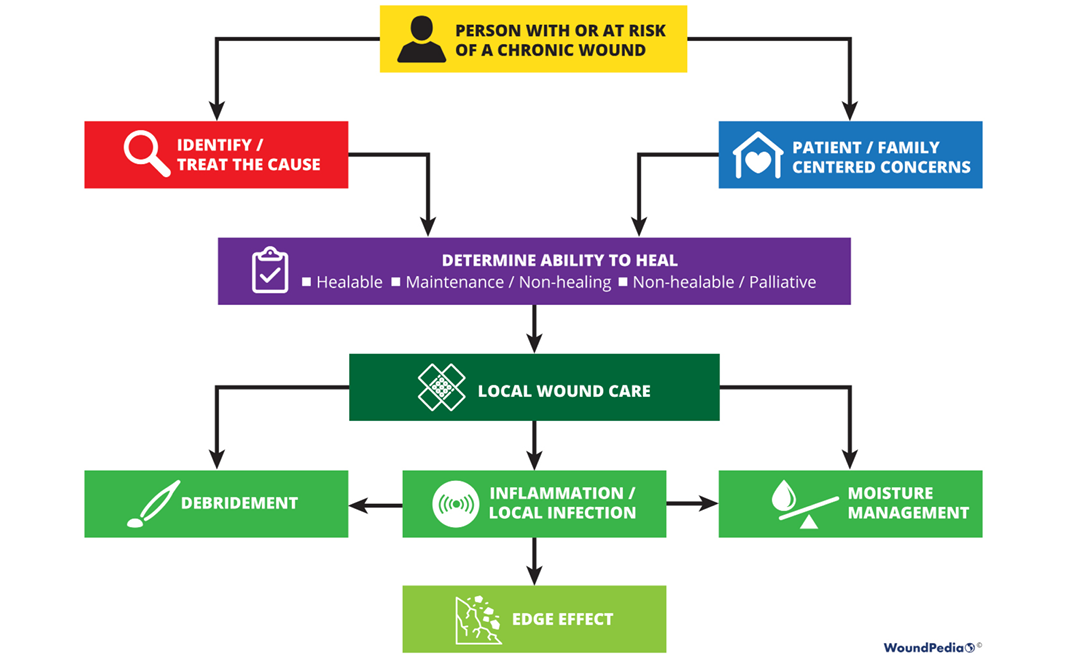

The final 10 statements are listed in Table 1. Each statement will now be expanded upon in more detail in a narrative summary and with accompanying visuals for translation to practice.

Table 1. WBP 2021 10 final statements

Statement 1 – Treatment of the cause

Optimal, timely diagnosis and treatment of the wound cause are the most important aspects of chronic wound care.

Substatement 1A – Determine if there is sufficient blood supply to heal/adequate perfusion

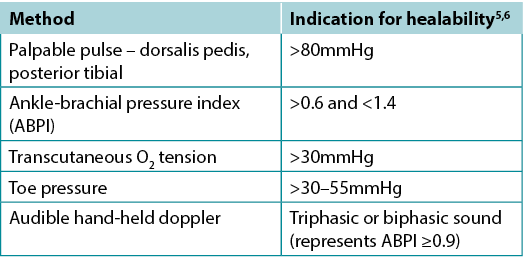

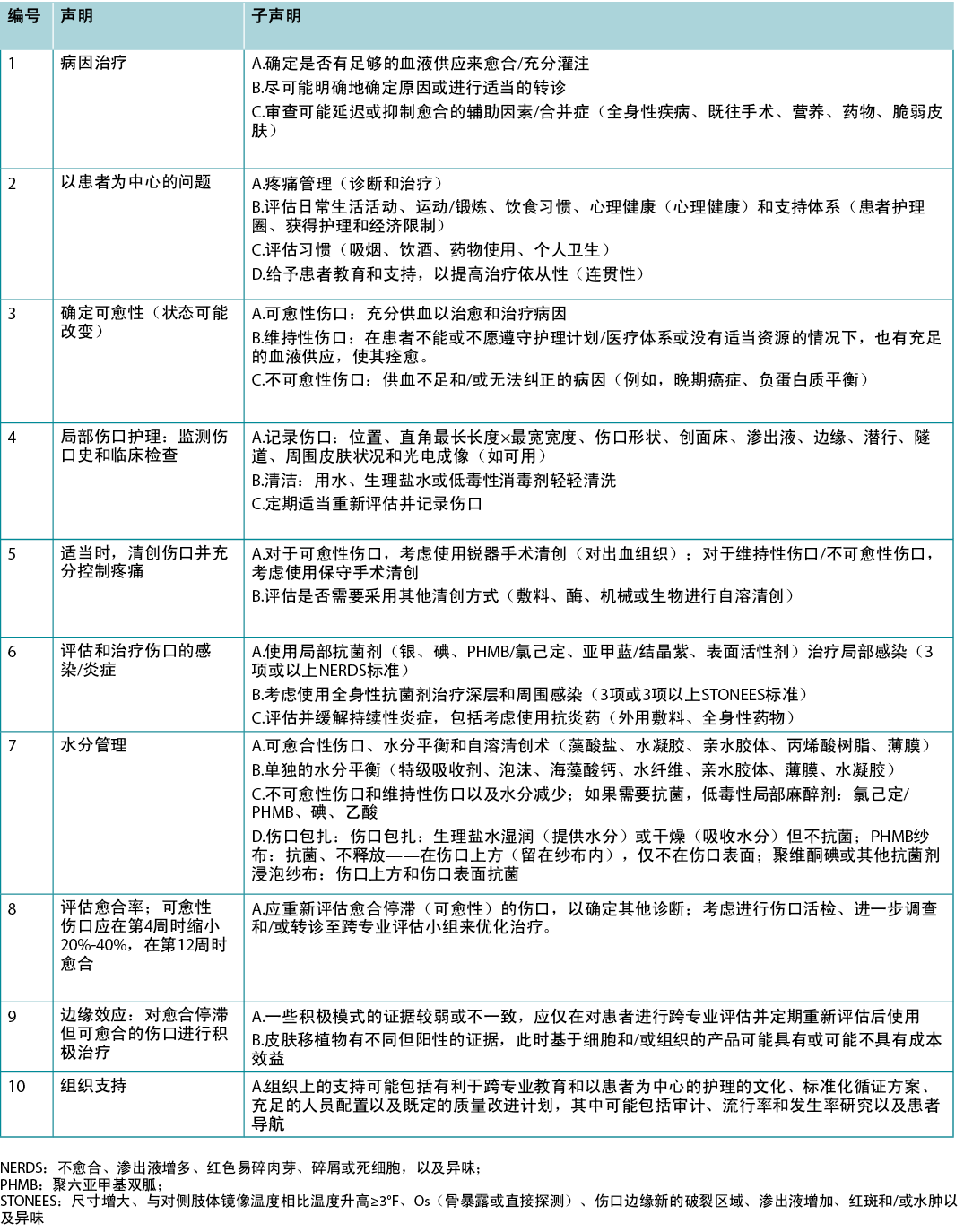

Clinicians should assess vascular supply for leg and foot ulcers to identify if there is adequate blood supply to heal. A palpable dorsalis pedis pulse usually indicates there is at least 80mmHg pressure in the foot (Table 2).

The ABPI is a ratio of the ankle systolic BP over the brachial systolic BP obtained using an 8-MHz portable Doppler. Approximately 8% of individuals may have an aberrant dorsalis pedis pulse, and the posterior tibial or peroneal pulse should be palpated as an alternative. The ABPI has been the standard for assessment of blood supply in the foot. A normal value is usually equal to or greater than 0.9 and less than 1.45,6; under 0.9 there may be some arterial disease, and over 1.4 the foot vessels are calcified and the value is inaccurate.

Ideally, the ABPI should be obtained after the patient has been recumbent for 20 minutes. A BP cuff is placed over the gaiter area of the lower leg. The clinician locates an audible arterial signal on the foot, and the cuff is inflated until the sound disappears. The cuff is deflated and, when the sound reappears, the systolic BP is recorded. The same procedure is repeated over the brachial artery.

Often oedema and inflammation (including congestive heart failure, acute or subacute lipodermatosclerosis or thrombophlebitis), along with infection, may result in pain. Acute pain may make occlusion of the lower leg artery impossible. In addition, up to 80% of persons with diabetes or 20% of older adults will have calcified vessels, providing an artificially high ABPI, rendering the test inaccurate. An alternative test is the AHHD evaluation. This test can be performed with the patient sitting or recumbent, and the BP cuff is not necessary around the gaiter area. An adequate amount of gel is placed over the dorsum of the foot and the audible waveform elicited (Table 2). A monophasic or absent audible signal indicates the need for a full vascular assessment. The presence of an audible multiphasic (biphasic/triphasic) wave indicates there is no significant peripheral vascular disease in the lower extremity, and compression therapy can be instituted. The foot should be checked for normal temperature and the absence of dependent rubor (dusky red colour) that blanches with elevation. This physical examination can be used to rule out an angiosomal defect (local or segmental artery occlusion). The dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial pulse should also be palpable.

Table 2. Vascular assessment methods (©WoundPedia 2021)

A 2015 study documented the results of AHHD readings performed on 379 legs in 200 patients which were compared with sequential lower-leg Doppler readings in a certified vascular laboratory7. The test is specific for excluding arterial disease (posterior tibial, 98.6%; dorsalis pedis, 97.8%) but is not sensitive for a diagnosis of arterial disease (posterior tibial, 37.5%; dorsalis pedis, 30.2%). This test is a reliable, simple, rapid, inexpensive bedside exclusion test for peripheral vascular disease among patients with or without diabetes. The results are independent of vascular calcification.

Again, a monophasic Doppler result or absent pulses should trigger segmental lower leg duplex Doppler studies of the arterial blood supply. In some cases, venous studies may be warranted, especially if there is a possibility of surgical or other venous intervention. This test can avoid delays in applying compression therapy when traditional ABPI studies are not possible (lack of access to a Doppler, pain, non-compressible vessels or time constraints).

For ulcers elsewhere on the body, there is a need for adequate perfusion; check the temperature of the surrounding skin. Examine the regional skin for dependent rubor of the arm or leg distally. On the central body, check the area for oedema or necrosis along with circulation time (a white area from a depressed finger on the skin should return in 3 seconds or less; otherwise, there may be compromise). Compromised circulation may indicate a maintenance or non-healable wound until the underlying defect is corrected.

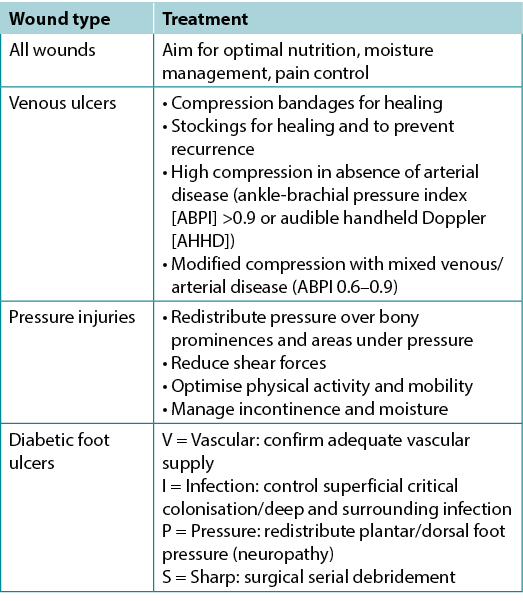

Substatement 1B – Identify the cause(s) as specifically as possible or make appropriate referrals

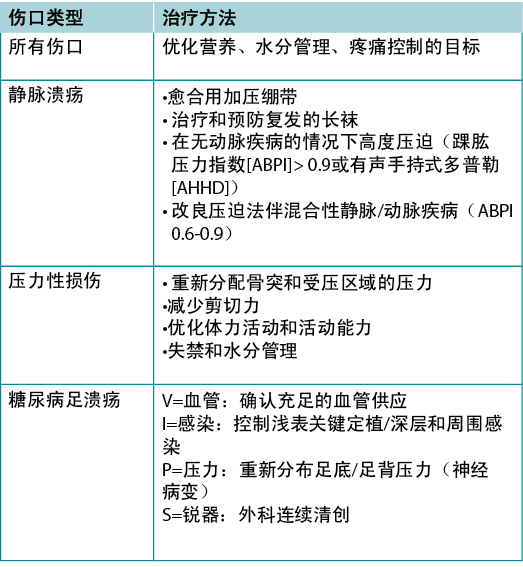

Often the cause of a non-healing wound is an “inadequate diagnosis”4. Practitioners must identify the wound cause as precisely as possible, considering vascular leg ulcers (venous, mixed, arterial, lymphatic or combinations), diabetic foot ulcers (neuropathic, ischaemic or mixed) and pressure injuries (which must be distinguished from moisture-associated skin damage); each has specific management considerations (Table 3). Other diagnoses include inflammatory ulcers (pyoderma gangrenosum, vasculitis), malignant ulcers (primary skin, other secondary malignancies), trauma/previous surgeries, medications, and congenital or acquired coexisting diseases. Some coexisting conditions put skin at risk. As skin ages, it becomes thinner. Photo damage and hereditary (e.g., epidermolysis bullosa, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) or acquired (e.g., bullous pemphigoid, toxic epidermal necrolysis) dermatologic disease increase susceptibility to trauma, including skin tears. Further, areas of moisture-associated skin damage may be more susceptible to pressure injuries or infection.

Table 3. Treatment of wound cause by type (©WoundPedia 2021)

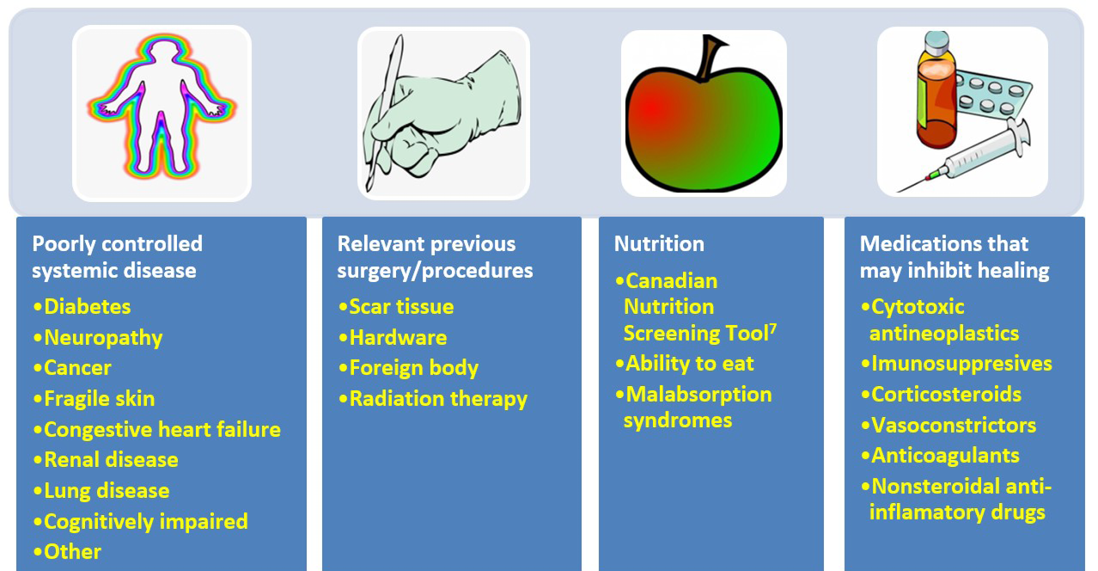

Substatement 1C – Review cofactors/comorbidities (systemic disease, previous surgery, nutrition, medications, fragile skin) that may delay or inhibit healing

Addressing modifiable cofactors is important for all persons with chronic wounds (Figure 2). Appropriate referrals for optimal management can often facilitate wound healing.

Figure 2. Cofactors and comorbidities to review for wound healing (©WoundPedia 2021)

Nutrition assessment can be facilitated with the validated two-question Canadian Nutritional Screening Tool8:

- Have you lost weight in the past 6 months without trying to lose this weight? (If the patient reports a weight loss but gained it back, consider it as no weight loss).

- Have you been eating less than usual for more than a week?

This tool has many advantages; no blood tests or diagnostic procedures are required, it is simple and rapid to administer and it is reliable9. Any healthcare professional can quickly identify a potential nutrition deficiency and the need for referral to a dietitian.

Statement 2 – Patient-centred concerns

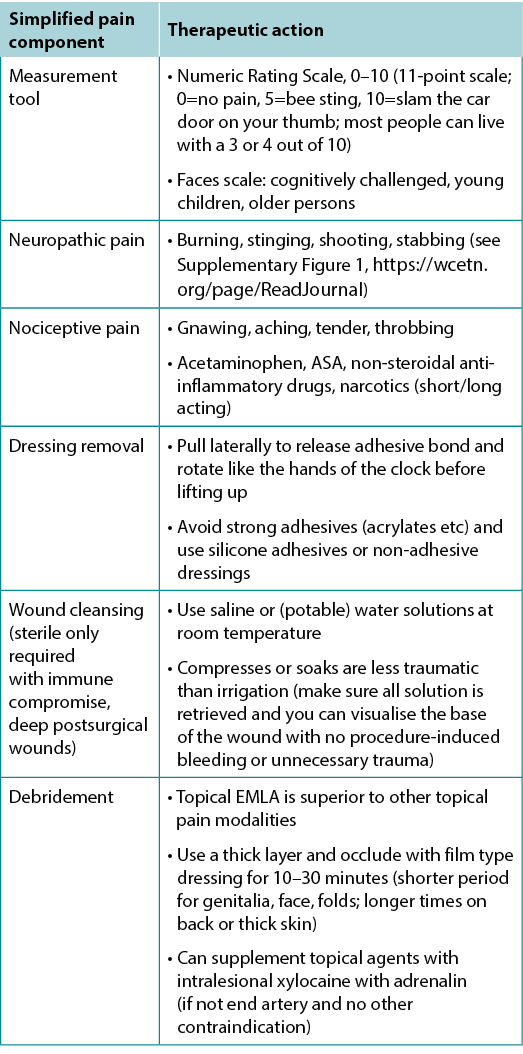

Substatement 2A – Manage pain (diagnosis and treatment)

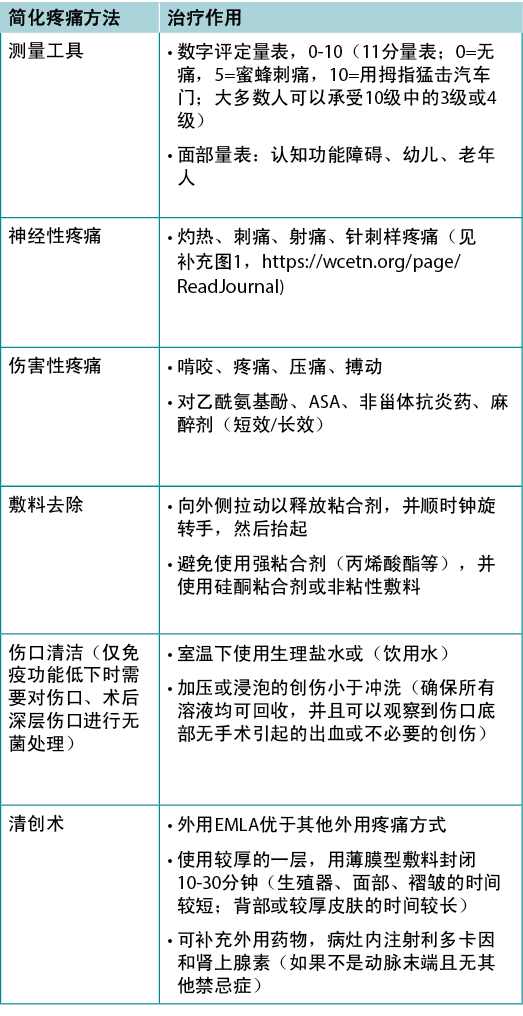

Pain is often the foremost concern of patients, whereas it is rarely the top concern of healthcare providers. Pain must also be quantified. The numeric rating scale (0–10) is typically used (Table 4). Reported pain levels of 5 or greater require intervention.

Table 4. Management of wound-related pain (©WoundPedia 2021)

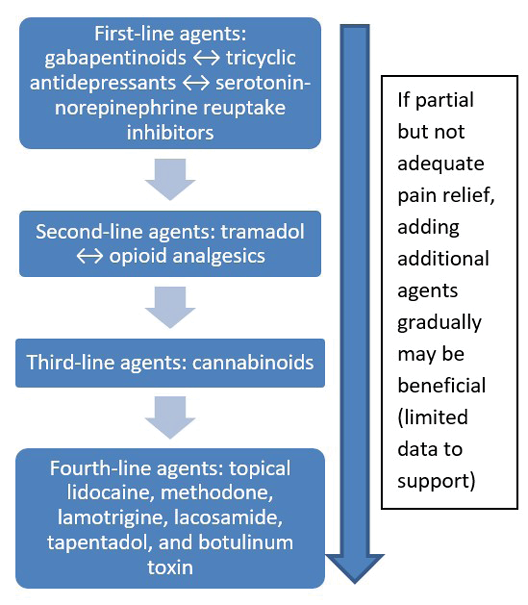

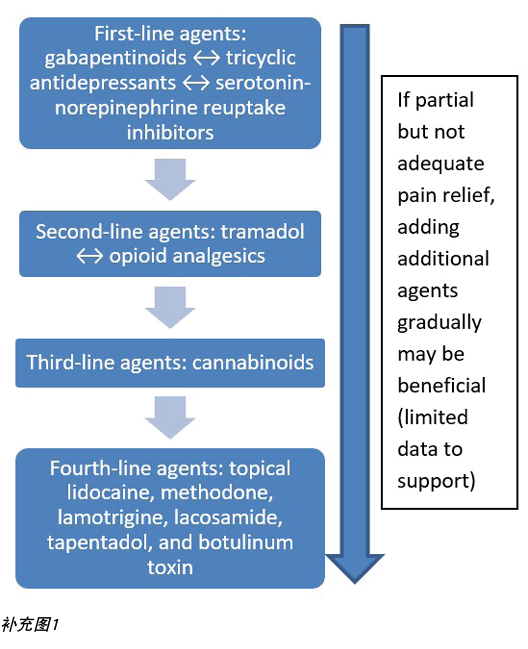

There are two major types of pain – nociceptive and neuropathic (Supplementary Figure 1, https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal). Nociceptive pain is related to injury, is stimulus dependent and is typically associated with aching, gnawing, tender or throbbing sensations. Neuropathic pain is often spontaneous and described as burning, shooting, stinging or stabbing. Each type has a different physiologic basis, necessitating different pharmacologic treatment.

A recent systematic review on topical analgesics associated with pain in chronic leg ulcers demonstrated a topical cream (eutectic mixture of local anaesthetics) was superior to other formulations for people living with chronic leg ulcers10. There are other topical modalities that may be associated with pain relief and strategies, including the use of silicone adhesives to replace other, more traumatic, acrylic adhesives at dressing removal.

Inadequate pain control can occur during many components of local wound care11. For painful dressing changes, oral medication must be administered at an appropriate time prior to the change. Between dressing changes, pain is often linked to the cause of the wound or its complications; consider non-pharmacologic measures (music therapy, meditation, acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, homeopathy, naturopathy and spiritual healing).

In summary, a patient’s rights in terms of pain involve the six Cs – every patient deserves to be Checked, the Cause determined, the Consequences of treatment explained (with adverse effects), adequate Control, the ability to Call timeouts during procedures and Comfort. Finally, providers must remember that pain management not documented is equivalent to no pain management.

Substatement 2B – Evaluate activities of daily living, mobility/exercise, eating habits, psychological wellbeing (mental health) and support system (patient circle of care, access to care and financial constraints)

Patient-centred concerns often involve inadequate support structures. They can also involve a lack of healthcare system agency impairing access to appropriate healthcare. Personal mental health may impair the patient’s ability to cope with the management of a chronic wound, and he or she may require help. There is a need for social workers, discharge coordinators and clinical psychologists to support systems in the community.

Substatement 2C – Evaluate habits (smoking, alcohol, substance use, personal hygiene)

Every cigarette will decrease local oxygenation 30% for an hour12. Cigarettes and other tobacco products can be a major factor preventing healing of chronic wounds or act as a proinflammatory stimulus for persons with hidradenitis suppurativa. Opiate use alone (especially >10mg/d) was associated with an increase in wound size and reduced likelihood of healing in a 2017 study of 450 patients13.

Substatement 2D – Empower patients with education and support to increase treatment adherence (coherence)

Aujoulat et al14 examined patient empowerment in relation to chronic disease education. They determined that: “the goals and outcomes… should neither be predefined by the healthcare professions, nor restricted to some disease and treatment related outcomes but should be discussed and negotiated with every patient according to his/her own particular situation and life priorities”14.

Moore et al.15 outlined four steps to increase patient involvement in their care:

1. Seek patient views/understanding of their condition.

2. Identify fears/concerns.

3. Establish what is important for the patient.

4. Assess willingness for involvement in their care.

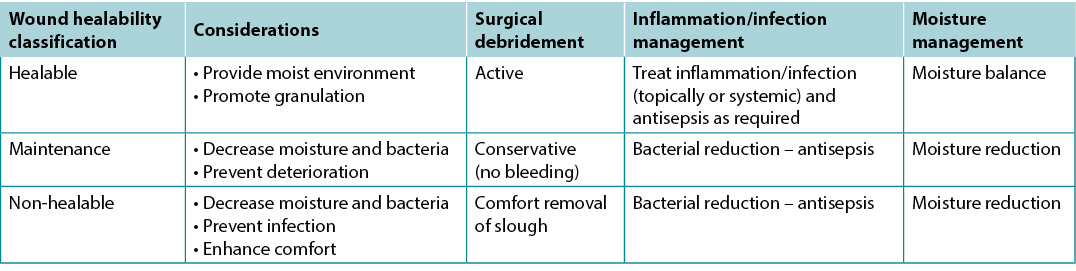

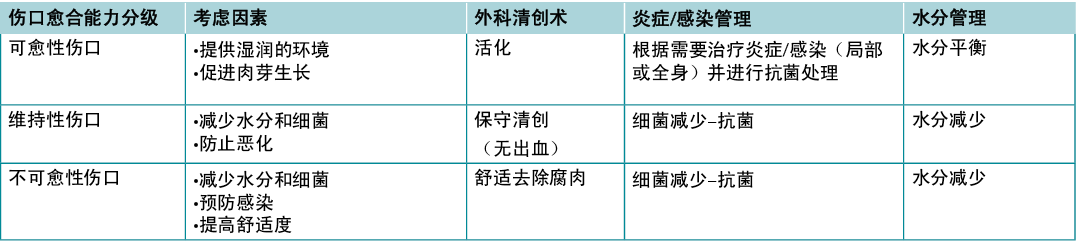

Statement 3 – Determine healability

One of the first steps providers must take after diagnosis is to determine healability, with the knowledge that the wound status may change. Generally, chronic wounds fall into one of three categories – healable, maintenance and non-healable. Local wound care strategies will vary by classification (Table 5).

Table 5. Summary of local wound care strategies; adapted from Sibbald et al16 (©WoundPedia 2021)

Substatement 3A – Healable: adequate blood supply to heal and treat the cause

A healable wound has enough blood supply to heal and the cause has been corrected. As a rule, approximately two-thirds of wounds in the community are healable.

Substatement 3B – Maintenance: adequate blood supply to heal where the patient either cannot or will not adhere to the plan of care/healthcare system or does not have appropriate resources

A quarter of wounds are maintenance wounds, either because of patient issues (e.g., refusal to wear compression bandages) and/or health system factors that prevent healing (e.g., cannot afford plantar pressure redistribution devices and the system will not supply the footwear).

Substatement 3C – Non-healable: inadequate blood supply and/or a cause that cannot be corrected (e.g., terminal cancer, negative protein balance)

Approximately 5–10% of wounds are non-healable, often because of inadequate blood supply that cannot be treated or corrected, advanced chronic disease, or the dying process. For patients with non-healable wounds, the paramount points of care to address are pain, infectious complications, exudate and odour control as well as activities of daily living.

Thirteen KOLs from the Wound Healing Society of South Africa conducted a recent systematic integrative review of non-healable and maintenance wounds17. This 13-member panel sourced 13 reviews, six best practice guidelines, three consensus studies and six original non-experimental studies. The three main conclusions were the need for patient-centred care, timely intervention by skilled healthcare providers, and an interprofessional referral pathway17.

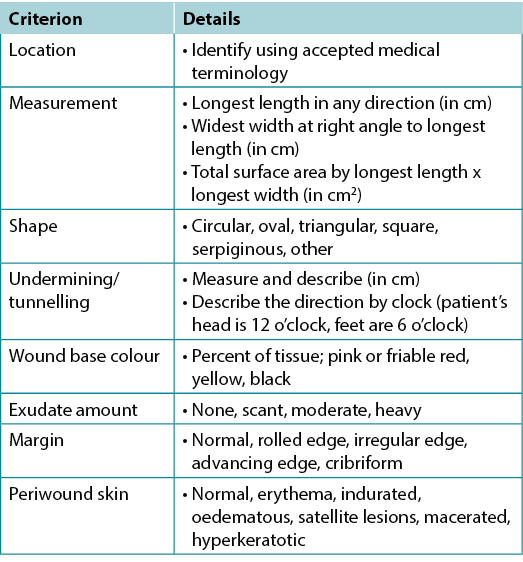

Statement 4 – Local wound care: monitor wound history and clinical examination

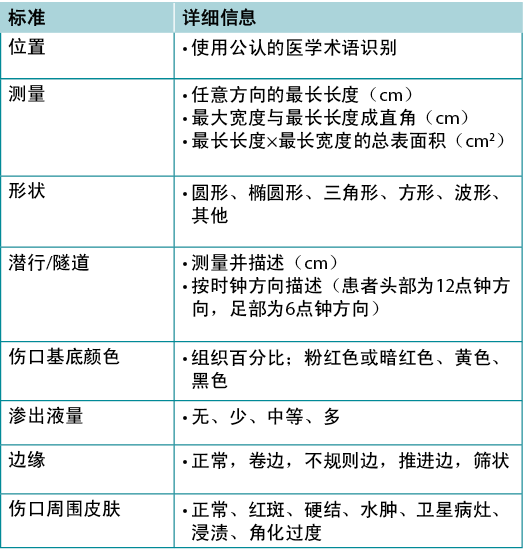

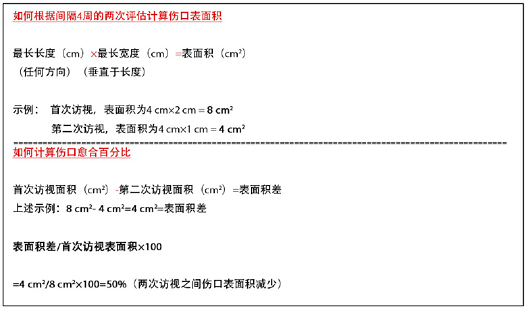

Substatement 4A – Document wound(s): location, longest length x widest width at right angles, wound shape, wound bed, exudate, margin, undermining, tunnelling, surrounding skin condition and photoimaging when available

Wound documentation is important (Table 6). Document the wound’s location and size; these authors recommend using the longest length and widest width perpendicular to one another, although head-to-toe alignment is also common. Pick the method of measurement that aligns with institutional policy; consistency is most important. Note and monitor undermining, tunnelling, tissue type in the wound bed, wound margins and periwound skin characteristics.

Table 6. Wound documentation (©WoundPedia 2021)

Substatement 4B – Cleansing: gently with water, saline or low-toxicity antiseptic agents

For healable wounds, local wound care may include sharp surgical debridement, treatment of infection (local infections, deep and surrounding infection) and moisture management. For non-healable wounds, optimal care may be aimed at conservative debridement of slough, bacterial reduction and moisture reduction. In these cases, antiseptic agents that may have some tissue toxicity may be preferable to allowing bacterial proliferation to cause further tissue damage leading to infection.

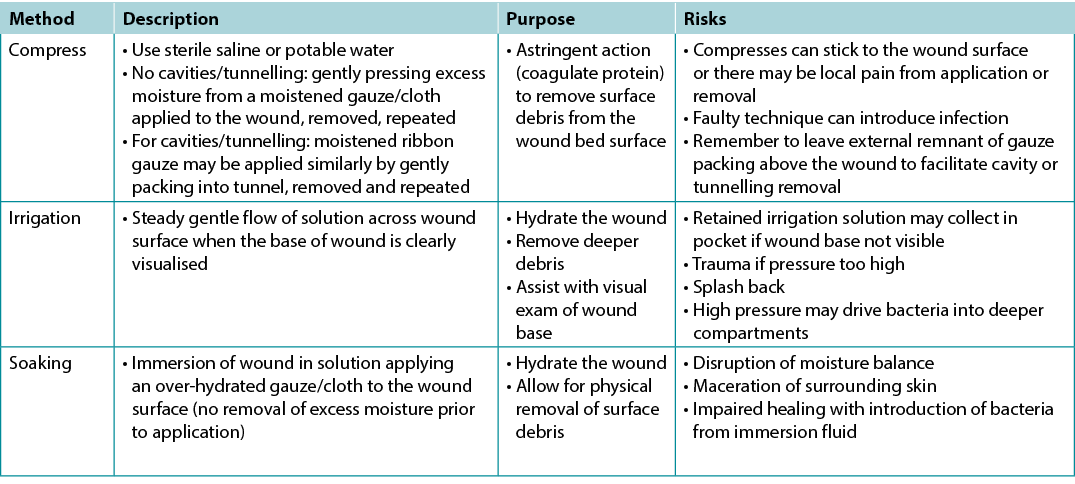

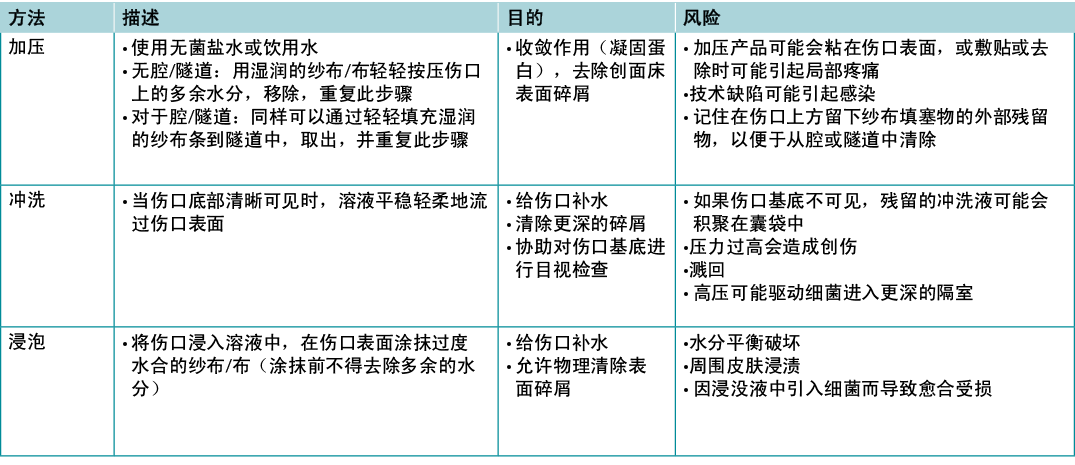

There is extraordinarily little high quality evidence on the topic of wound cleansing (Table 7); accordingly, it is hard to draw any conclusions so the topic of wound cleansing is one that requires further research19. When irrigating, note the amount of solution that was used going into and out of the wound bed. Caution should be used when the entire wound bed is not clearly visualised or intact. Be careful not to harm the wound bed through excess trauma.

Table 7. Methods of wound cleansing; adapted from Nicks et al18 (©WoundPedia 2021)

Substatement 4C – Reassess and document wounds at appropriate, regular intervals

Statement 5 – When appropriate, debride wounds with adequate pain control

Debridement is a way to remove slough, debris or foreign substances that may facilitate infection or act as a proinflammatory stimulus, prolonging the inflammatory stage of wound healing and delaying the proliferative reparative process. Sharp surgical debridement requires assessment of the blood supply to be sure it is adequate for healing. Before starting, providers who are considering even conservative debridement methods must ensure they have appropriate competency, scope of practice, the required equipment, and support in the event of bleeding, as well as alignment with their facility’s policies and procedures.

Although it did achieve consensus, the relatively lower agreement levels among KOLs for this statement were likely attributable to facility-related limitations on sharp debridement. This procedure requires clinical experience, appropriate scope of practice, and availability of equipment to perform the procedure and stop bleeding if required.

Substatement 5A – Consider sharp surgical debridement (to bleeding tissue) for healable wounds and conservative surgical debridement for maintenance/non-healable wounds

For healable wounds, this means sharp surgical debridement, autolytic debridement with dressings or enzymatic, biologic (medical maggots), or mechanical debridement. For non-healable and maintenance wounds, this means conservative surgical or other methods of non-viable slough removal.

Patient empowerment can be modelled on the 4-Step Clinical Decision Making Debridement Guide20 for a mutual agreement between patients and clinicians. First, ask whether the wound is capable of healing. If the answer is yes, select the appropriate method based on patient concerns and wound characteristics. Next, investigate which wound characteristics influence debridement choice, such as secondary infection, pain, wound size and exudate. Ascertain how selective a debridement method is needed; determine if there is any risk to healthy tissue when necrotic tissue is being debrided. Finally, consider the care setting. Some clinicians and/or types of resources may not be available in all care settings. Government regulation and facility policy may also be factors20.

Substatement 5B – Evaluate the need for alternative debridement modalities (autolytic with dressings, enzymatic, mechanical or biologic)

Autolytic debridement can be accomplished via calcium alginate, hydrogel and hydrocolloid dressings. This type of debridement is often relatively painless, but it may be slower than surgical methods. Enzymatic debridement (collagenase) is often used where surgical debridement or autolytic dressings are not available. It is a relatively slow method, and the treatment requires a prescription.

Mechanical debridement may be accomplished using advanced technologies such as ultrasound that require clean or sterile conditions with protection from bacterial contamination and airborne bacterial pathogens or particulate matter. Whirlpool systems may contaminate areas of emersed skin and may cause cross-contamination between patients. Saline wet-to-dry gauze is nursing time intensive, painful on dressing removal, and can remove healthy viable tissue from the wound surface.

Moya-López et al.21 recently published a review of maggot debridement therapy for chronic wounds. Maggot therapy can be faster than some other non-surgical debridement methods, and it is selective for devitalised tissue. The authors concluded that more data were needed by wound type, frequency of application and the efficacy of treatment. Maggots are not indicated for ischaemic wounds and when deep and surrounding infection has not been treated systemically.

Statement 6 – Assess and treat wounds for infection/inflammation

Wound infections have two compartments – one superficial and the other deep10,12. Wounds can be thought of as a bowl of soup; the thin layer on the surface of a wound is analogous to the superficial compartment, and the sides and bottom of the soup bowl are equivalent to the surrounding and deep components of a chronic wound.

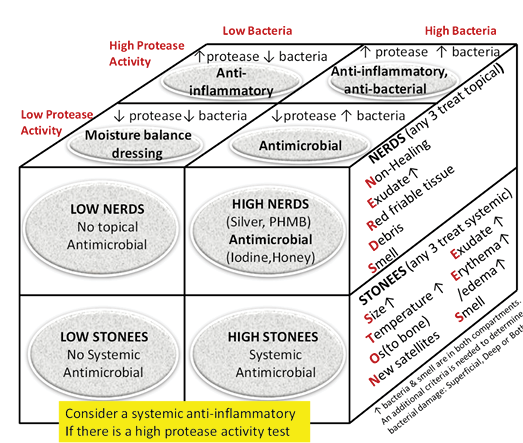

Substatement 6A – Treat local infection (three or more NERDS criteria) with topical antimicrobials (silver, iodine, polyhexamethylenebiguanide [PHMB]/chlorhexidine, methylene blue/crystal violet, surfactants)

The superficial compartment of a chronic wound is a thin layer of cells that can be treated topically. Any three or more NERDS (Nonhealing, Exudate increase, Red friable granulation, Debris or dead cells, and Smell) criteria are signs of local infection, for which topical antimicrobials may be indicated. If the wound is healable and the cause treated, it should take 4 weeks or less to improve. Clinicians should know that treating the superficial wound compartment requires dressings to release antimicrobial agents onto the surface of the wound. Non-release dressings will work above the wound surface but cannot penetrate the superficial compartment. This may prevent bacterial growth above the wound, but another agent may be needed to target the surface wound compartment. For example, antiseptic sprays such as chlorhexidine mouthwashes often have less available alcohol with decreased local burning and stinging compared with some presurgical antiseptics designed for intact skin. Some topical agents release silver or iodine in various concentrations to penetrate the surface compartment and treat local infection.

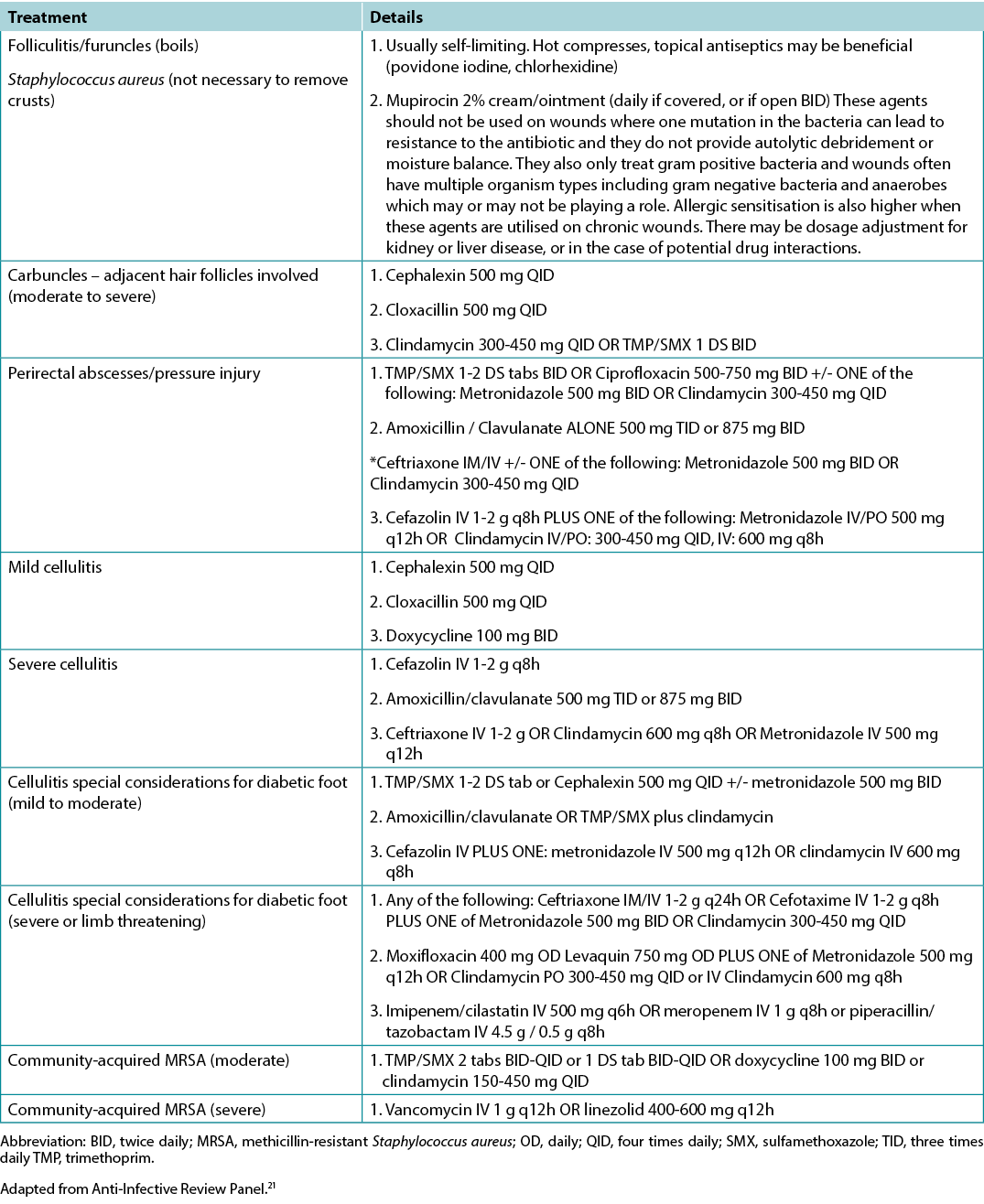

Substatement 6B – Consider treating deep and surrounding infection (three or more STONEES criteria) with systemic antimicrobials

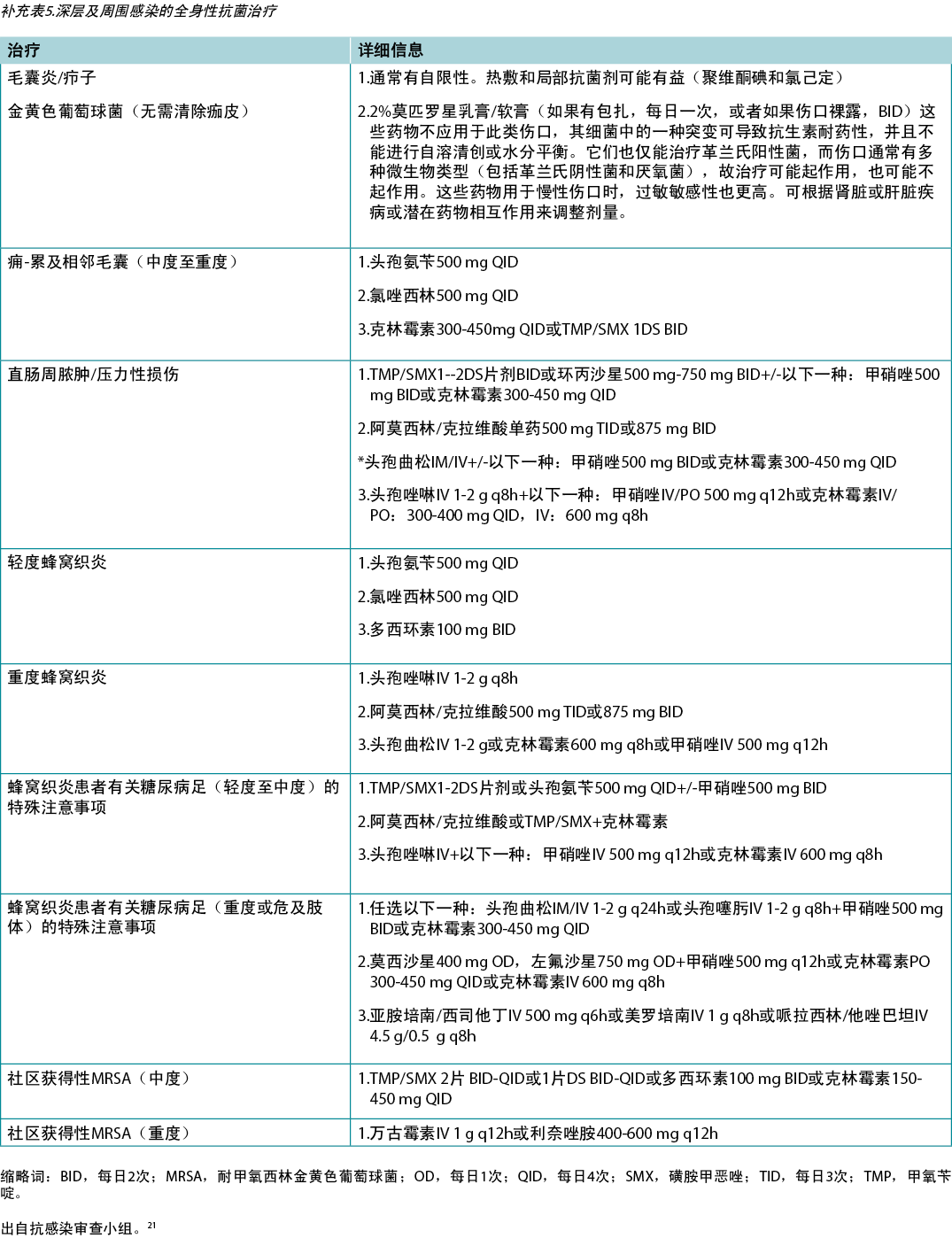

Topical antimicrobial agents penetrate only a few millimetres; deep and surrounding infections may require systemic antimicrobials (Supplementary Table 5, https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal). Four of the seven STONEES criteria represent the wounds’ surrounding features (the sides of the soup bowl) – increased Size, elevated Temperature of 3°F over a mirror image of the surrounding wound skin, New or satellite areas of involvement and a surrounding cellulitis (Erythema or Edema). Cellulitis is not always present when chronic wounds are associated with deep and surrounding infection, and erythema is not easily recognised in skin of colour or the presence of oedema. The three remaining STONEES signs in the wound bed include probing to bone (Os [Latin for bone]), increased Exudate and Smell.

Substatement 6C – Evaluate and alleviate persistent inflammation including consideration of anti-inflammatory agents (topical dressings, systemic medication)

Factors other than infectious organisms can play a role in a persistent inflammatory response. These factors include invading cells (neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes), immune complexes (vasculitis), granulomatous inflammation (sarcoidosis, etc) and others; consider these factors when picking a topical or systemic therapy. There are some topical antimicrobials that are proinflammatory, such as iodine. There are other agents that may be anti-inflammatory, including silver, and some that are neutral, such as PHMB gauze/foam and gentian violet/methylene blue foam.

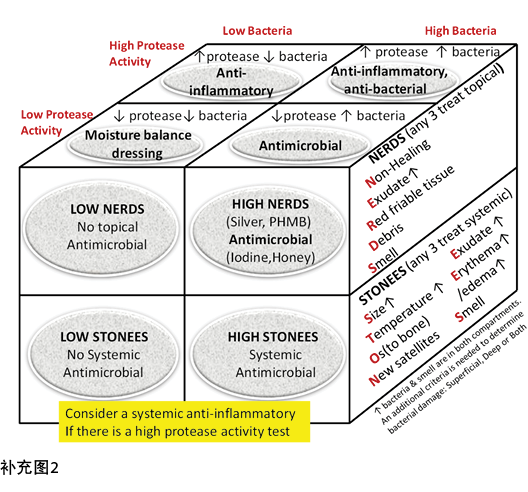

Inflammation can also lead to delayed wound healing in both compartments. Protease tests are not always available in the clinical setting and may only measure surface rather than deep changes. Some of the signs of infection may also be part of the clinical presentation for persistent inflammation. The Sibbald Cube (Supplementary Figure 2 (https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal) outlines where high proteases in wounds with and without infection may prevent healing in both the superficial and deep compartments. Recently published data indicate biomarkers may predict the healing trajectory of venous leg ulcers22. The right therapy at the right time could more effectively control proteases, bacterial contamination, debridement and moisture control with optimal timing of growth factors, matrix constructs and cellular components.

In regard to topical therapies, silver- and honey-based products have reported anti-inflammatory effects. These agents should only be used with local infection and inflammation for short periods of time. Systemically, several antibacterial agents have anti-inflammatory action. Commonly recommended antimicrobials (some with anti-inflammatory effects) for wounds and related skin infections are listed in Supplementary Table 5 (https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal).

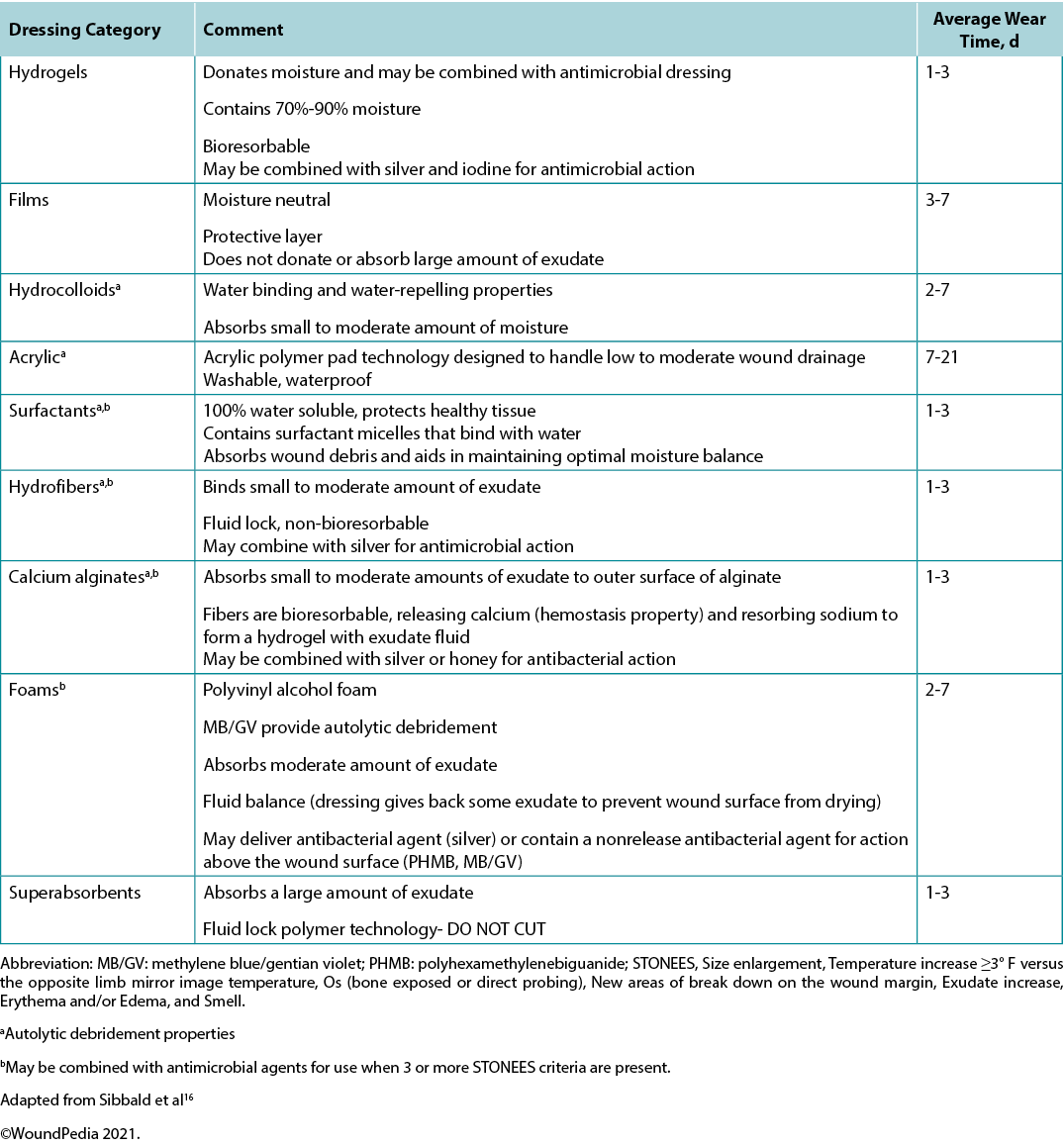

Statement 7 – Moisture management

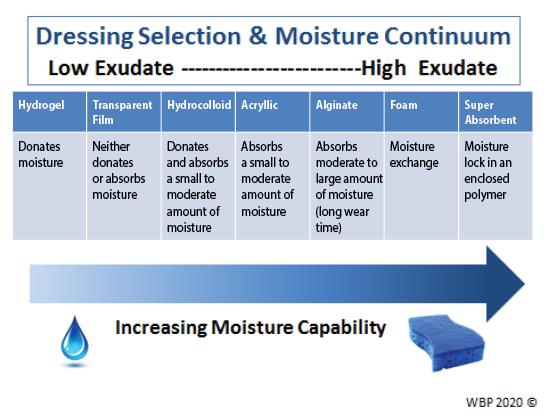

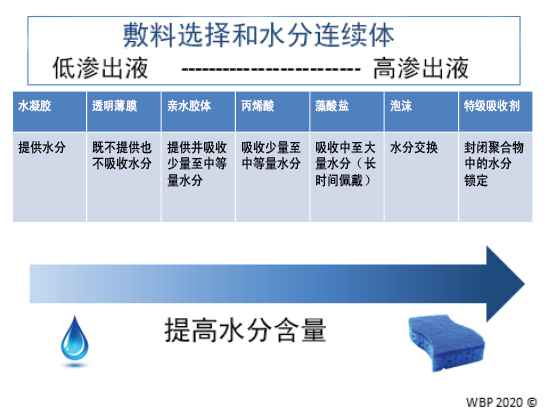

Providers must select an appropriate dressing to match the wound characteristics and individual patient needs (Figure 3). Ideal moisture management depends on a wound’s healability.

Figure 3. Optimising moisture management; adapted from Sibbald et al16 (©WoundPedia 2021)

Substatement 7A – Healable, moisture balance and autolytic debridement (alginates, hydrogels, hydrocolloids, acrylics, films)

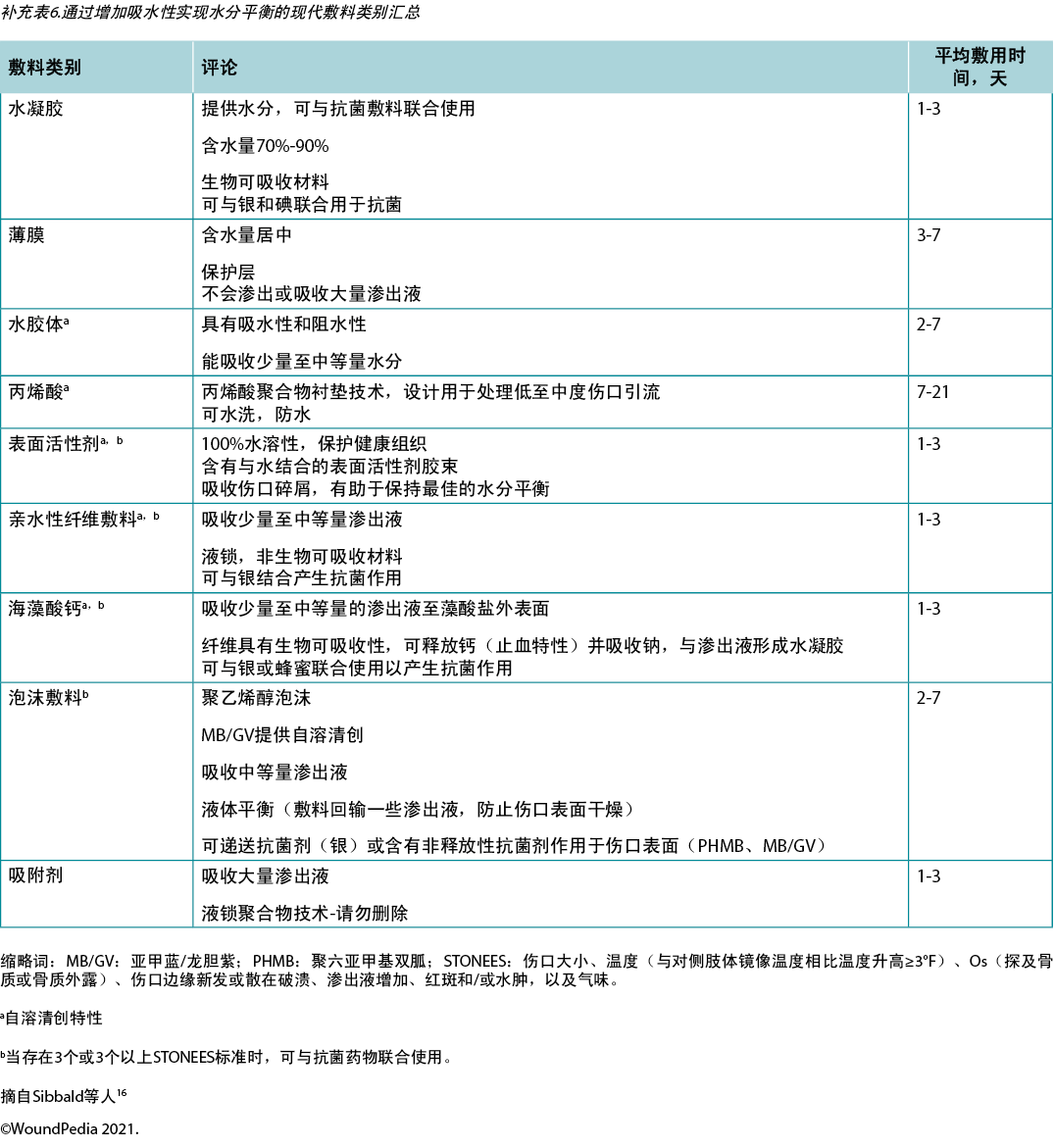

In healable wounds, moisture balance can be achieved by choosing the appropriate dressing from the moisture continuum in the enabler (Supplementary Table 6, https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal) that lists dressings for low to highly exudative wounds.

Substatement 7B – Moisture balance alone (super absorbents, foams, calcium alginates, hydrofibers, hydrocolloids, films, hydrogels)

Substatement 7C – Non-healable and maintenance wounds and moisture reduction; if antibacterial needed, low toxicity topical anaesthetics: chlorhexidine/PHMB, iodine, acetic acid

For individuals with maintenance or non-healable wounds, target moisture and bacteria reduction. Wounds need to be constantly reassessed for healing or deterioration and dressing choices may need to be altered based on presentation.

For these wounds, providers need to balance patient preference and comfort to avoid pain, as well as prevent overdrying of wounds. Tulle dressings are often most appropriate; they are a combination of gauze or fabric with a petrolatum or paraffin coating. They may also contain an antiseptic (e.g., chlorhexidine, iodine).

However, several dressings can optimise moisture management16. Chlorhexidine (0.5% in white paraffin impregnated into a tulle sheet) is active against Gram-positive and negative bacteria; PHMB is a non-release foam, gauze/packing ribbon formulation. Iodine dressings (either in cadexomer molecule or as povidone iodine) have a broad spectrum of activity, albeit decreased effectiveness in the presence of pus or exudate. Note that these dressings may be toxic with prolonged use over large areas (as povidone iodine). Finally, acetic acid (0.5–1%, e.g., diluted white vinegar) should be placed using gauze on the wound bed usually for about 5–10 minutes, often as a rotating compress. These dressings have a low pH and are effective against Pseudomonas species; however, they may select out other organisms16.

Substatement 7D – Wound packing: saline wet (donate moisture) or dry (absorb moisture) but not antibacterial; PHMB gauze: antibacterial, non-release-above the wound (stays in the gauze) only not in the wound surface; povidone iodine or other antiseptic soaked gauze: antibacterial above and on wound surface

Saline packing may be used in healable wounds without critical colonisation. It is not the purpose of these dressings to stick to the wound bed so that there will be trauma with dressing removal. If a dry saline gauze sticks to the wound bed, the gauze should be moistened before application and, if it sticks, moistened again prior to removal. Alternate dressings should then be chosen to maintain moist, interactive healing.

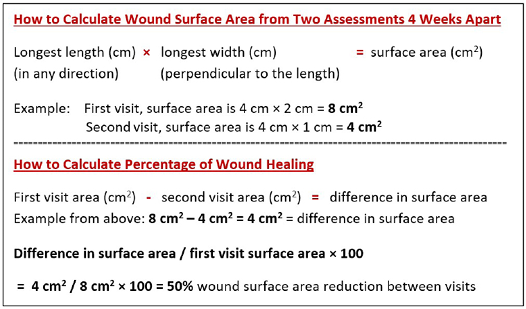

Statement 8 – Evaluate the rate of healing

If a wound is not at least 20–40% smaller by week 4, it is unlikely to heal by week 12 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. How to calculate wound surface area

Substatement 8A – Stalled (healable) wounds should be re-evaluated for alternate diagnoses; consider wound biopsy, further investigation, and/or referral to an inter-professional assessment team to optimise treatment

Healing trajectory can be assessed in the first 4–8 weeks to predict if a wound is likely to heal by week 12, provided there are no new complicating factors9. Stalled but healable wounds often need a comprehensive interprofessional assessment to optimise treatment and improve the healing trajectory. This may necessitate the reclassification of a wound to the maintenance or non-healable category.

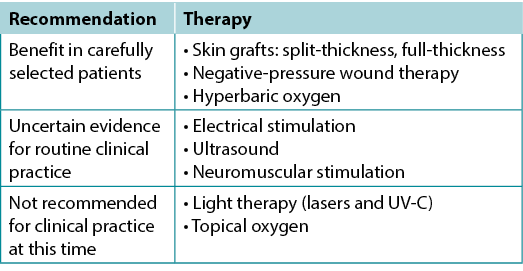

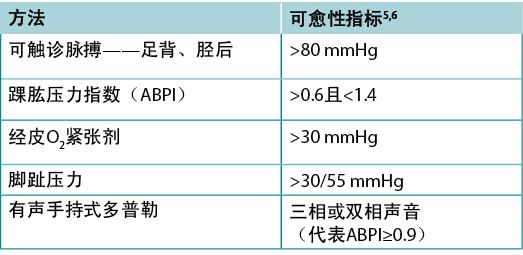

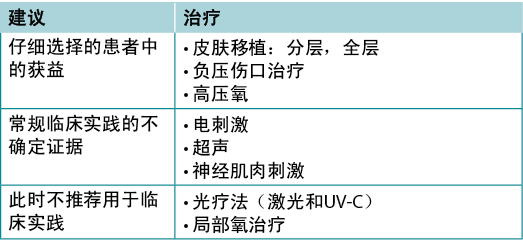

Statement 9 – Edge effect

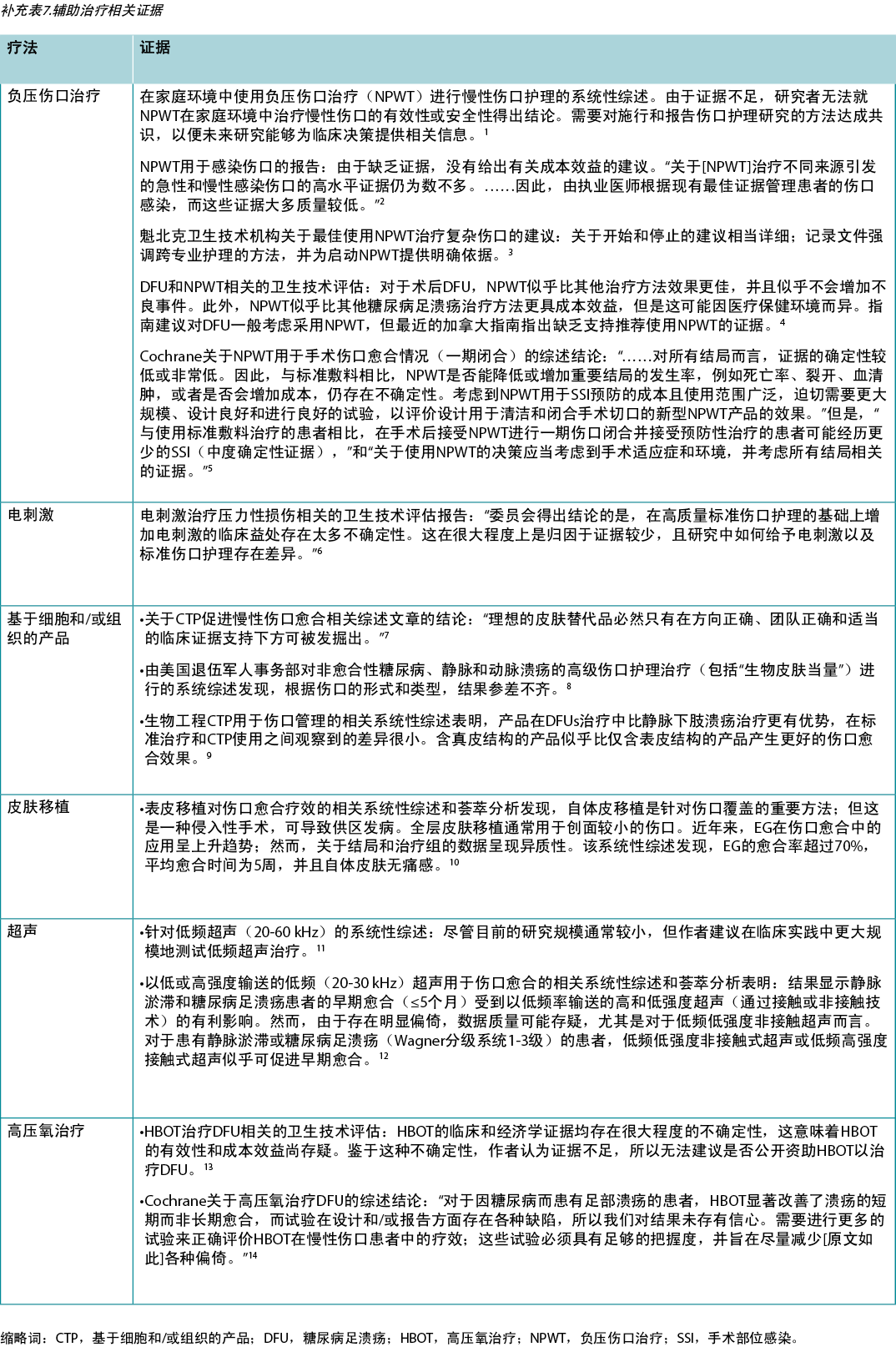

Use active therapies for stalled but healable wounds. See Supplementary Table 7 (https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal) for evidence on adjunctive therapies – negative-pressure wound therapy, electrical stimulation, cellular and/or tissue-based products, skin grafts, ultrasound and hyperbaric oxygen therapy (Table 8).

Table 8. Adjunctive therapies

Substatement 9A – Some active modalities have weak to mixed evidence and should be used only after inter-professional assessment of the patient and with regular re-evaluations

Substatement 9B – Skin grafts have variable but positive evidence, and cellular and/or tissue-based products may or may not be cost-effective at this time

Many active therapies have appeared and disappeared in the wound healing toolbox. Not only do these therapies need to stimulate healing, but also they must be cost-effective within the context of the local health system. Some of these therapies have better evidence for acute wounds than with chronic, non-healing wounds (e.g., negative-pressure wound therapy after diabetic foot surgery, split-thickness skin grafts), particularly where the cause is not or cannot be corrected. If an active therapy is selected, it is imperative that a consistent and accurate wound assessment be conducted so that wound progression in either direction may be determined and the therapy discontinued in a timely manner if the wound is not on a healing trajectory. More high-quality randomised controlled trials on these therapies are needed before definitive recommendations on their use can be made.

Statement 10 – Organisational support

Substatement 10A – Organisational support may include a culture conducive to interprofessional education and patient-centred care, standardised evidence-informed protocols, adequate staffing, and established quality improvement programs that may include audits, prevalence and incidence studies and patient navigation

Elements of an effective organisational plan for guideline implementation are as follows23:

- Assess organisational readiness and barriers to implementation, considering local circumstances.

- Involve all members (whether in a direct or indirect supportive function) in the implementation process.

- Provide ongoing educational opportunities to reinforce best practice.

- One or more qualified individual(s) should provide the support needed for the education and implementation process.

- Provide opportunities for reflection on personal and organisational experience in implementing guidelines.

Often the barriers to successful wound healing are related to the health system and not a lack of provider knowledge. Better coordination of care is needed across the continuum, from acute to chronic care, as well as standardisation of formularies and best practices. This could be accomplished through situational learning, changing healthcare systems to facilitate interprofessional assessment of complex patient problems, and breaking down barriers within and across healthcare organisations. This requires organisations to invest in resources for interprofessional education on wound care practices, as well as collection and regular review of wound care data outcomes in the form of an ongoing quality initiative.

Patients with chronic wounds often have limited resources and come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Using patient navigation models to facilitate referrals and link homecare providers with care coordinators to access system resources is one way forward24,25. However, this is only successful when team members are linked together as part of a coordinated interprofessional model. These health system changes can increase value.

The Porter model of healthcare links the voice of the patient with the provider, payer, policy maker and even the politician to provide value for the healthcare dollar26. For systems to change, policymakers and politicians must be aware of inconsistencies and inequities facing wound care patients and providers as the first step toward improving patient-centred wound care.

Conclusions

These 10 evidence-informed statements have received consensus from KOLs in repeated surveys. The provision of enablers is intended to assist with dissemination of the WBP paradigm into practice. A concerted effort has been made to emphasise the importance of early, proactive assessment of the wound healing trajectory. By intervening before wounds become chronic, there are benefits for the patient, providers, payors and policy makers. This is more important now than ever in the face of mounting healthcare costs and ageing populations.

Conflict of Interest

Dr LeBlanc has disclosed that she is a speaker for Hollister, Coloplast, 3M and Mölnlycke. Dr Ayello has disclosed that she has received educational/research grants from Sage/Stryker and Calmoseptine. Dr Sibbald has received grants from Mölnlycke, Calmoseptine and the Government of Ontario for Project ECHO Skin and Wound.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

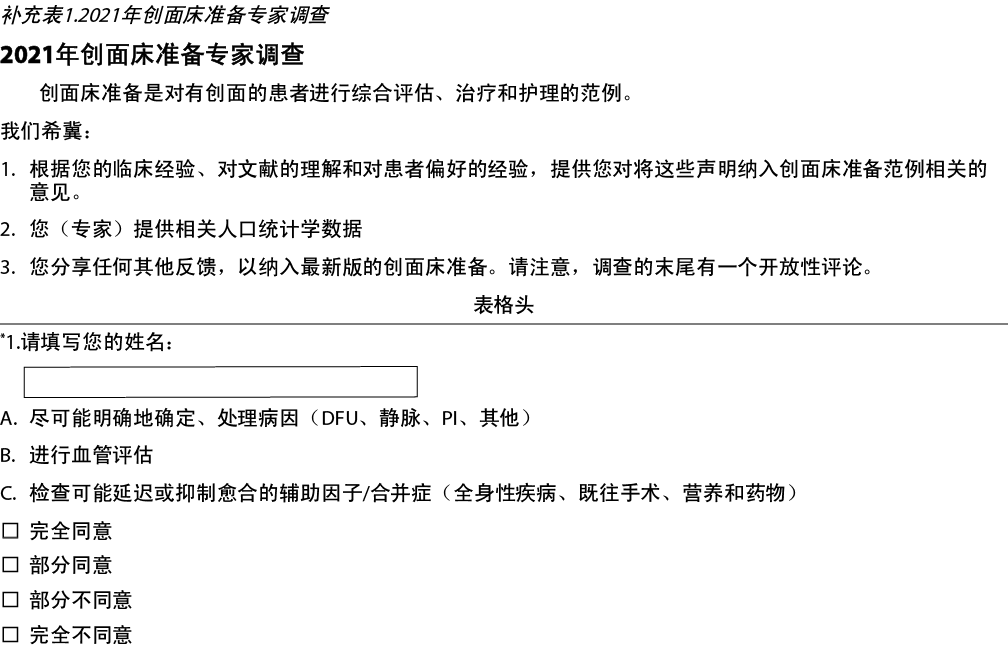

Supplementary Table 1. Wound bed preparation 2021 expert survey

Supplementary Table 2. key opinion leader wound bed preparation 2021 survey results (n = 21)

Supplementary Table 3. ABU Dhabi international interprofessional wound care course wound bed preparation 2021 survey results (n = 66)

Supplementary Table 4. Canada international interprofessional wound care course wound bed preparation 2021 survey results (n = 65)

Supplementary Table 5. Systemic antimicrobial therapy for deep and surrounding infection

Supplementary Table 6. Summary of Modern Dressing Categories for Moisture Balance by Increasing Absorbency

Supplementary Table 7. Evidence on adjunctive therapies

创面床准备

R Gary Sibbald, James A Elliott, Reneeka Persaud-Jaimangal, Laurie Goodman, David G Armstrong, Catherine Harley, Sunita Coelho, Nancy Xi, Robyn Evans, Dieter O Mayer, Xiu Zhao, Jolene Heil, Bharat Kotru, Barbara Delmore, Kimberly LeBlanc, Elizabeth A Ayello, Hiske Smart, Gulnaz Tariq, Afsaneh Alavi and Ranjani Somayaji

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.42.1.16-28

摘要

创面床准备(WBP)模型是优化慢性伤口治疗的范例。这种全面的方法通过研究病因治疗和以患者为中心的问题,确定伤口是可愈性伤口、维持性伤口还是不可愈性(姑息性)伤口。对于可愈性伤口(具有充足的血液供应且病因可以纠正),应在积极清创和控制局部感染或异常炎症的同时保持水分平衡。在维持性伤口和不可愈性伤口中,重点关注患者的舒适度、疼痛缓解、异味控制、通过减少伤口表面的细菌来预防感染、腐肉保守性清创以及包括渗出液控制的水分管理。

在第四次修订中,作者将WBP模型的内容重新表述为10项声明。本文的重点是最近5年的文献或对较早文献的新解释。该过程旨在促进临床环境中的知识转化,并以较低的医疗体系成本改善患者结局。

引言

创面床准备(WBP)是一种结构化的伤口愈合方法。现在进入其广泛应用的第三十年,WBP范例于2000年首次发布,并在2003年、2006年、2011年、2015年和2021年定期更新。本文列举了WBP模型既往版本中制定的10项声明,报告了针对这些原则达成共识而对当前伤口护理从业人员进行调查的结果,并总结了支持每项声明的相关证据。最新迭代具有以下主要变化:

· 使用有声手持多普勒(AHHD)测量足背或胫后动脉的方法作为传统踝肱压力指数(ABPI)测量的替代方法,用于临床评估足够的动脉供血以进行愈合和安全应用加压疗法的能力。

· 更新伤口患者局部和全身疼痛管理方法。

· 更新维持性伤口和不可愈性伤口的管理。

· 为WBP的其他八个组成部分的知识传播提供新推动因素。

Sackett及其同事1将循证医学定义为“整合个人的临床专长和最佳的外部证据”。具体而言,循证医学的三大支柱包括科学实证、专业意见和患者偏好;这些均纳入WBP 2021范例的10项声明中(图1)。

图1.WBP范例2021(©WoundPedia 2021)

让利益相关者参与评估过程的建议是一种弥合“转化差距”2的策略。伤口愈合专家和积极的伤口护理从业者参与了10项声明的评估过程,以加强传播3,4。此外,作者全面检索了最近的文献,检索结果贯穿于本文。最后,WBP 2021包括一组将知识转化为实践的推动因素。这些推动因素是旨在护理点使用,加强实施WBP声明的工具。

方法

作者根据既往版本的WBP范例,并参考最近的文献综述,制定了最初的10项声明。这些初始声明用于创建在线调查和一系列可视“推动因素”,为每项声明添加更多详情。10项声明中有些进一步细分为字母编号子声明(1A、1B、1C等)。在6个月期间,共有20名开发人员和外部伤口护理利益相关者对该调查进行了反复审查和评估,以确定其表象和内容的有效性,并最终确定发表。

此外,还向伤口愈合关键意见领袖(KOL)发送该调查(补充表1,https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal)的特定模板。作者从每个洲和每个关键的伤口愈合专业的医生、护士和相关医疗执业者中至少选择了一名KOL。对于每项声明,受访者均表明了他们是强烈同意、有些同意、有些不同意或强烈不同意。对声明的预期认同水平为80%的受访者有些同意或强烈同意每项声明。此外,还向阿布扎比和加拿大的国际跨专业伤口护理课程(IIWCC)的毕业班学生发送了该调查。受访者正在完成为期一年的KOL培训,并获得了结业证书。大多数(但非全部)班级成员自愿参加该调查。

表1.WBP 2021 10项最终声明

结果

本研究要求对阿布扎比(n=66)和加拿大(n=650)的KOL(n=21)和IIWCC 2020级学生进行调查。每项声明的21个KOL的认同度在86%-100%之间(补充表2)。在阿布扎比开设的2020级IIWCC班级的认同度为98%-100%(补充表3),在加拿大的班级的认同度达到85%-100%(补充表4,所有表格均可参见https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal)。除了普遍较高的认同水平外,最值得注意的结果是KOL与声明5的认同度相对较低(仍为86%;稍后讨论),而阿布扎比学生对所有声明的认同度均较高。这可能是因为阿布扎比的学生(来自几个西亚国家和少数来自非洲的学生)比其他群体的伤口护理经验更少。

最终10项声明如表1所示。现在每项声明均将在叙述性总结中进行更详细的阐述,并随附视图,以便转化为实践。

声明1——病因治疗

最佳的、及时的诊断和伤口病因治疗是慢性伤口护理的最重要因素。

子声明1A——确定是否有足够的血液供应来愈合/充分灌注

临床医生应评估下肢和足部溃疡的血管供应,以确定是否有足够的血液供应来愈合。通常,明显的足背动脉搏动表明足部至少有80 mmHg的压力(表2)。

表2.血管评估方法(©WoundPedia 2021)

使用8 MHz便携式多普勒获得踝关节收缩压与肱动脉收缩压,ABPI是两者的比值。约8%的个体可能有异常的足背动脉搏动,应触诊胫后动脉或腓动脉搏动作为替代。ABPI已经成为评估足部供血的标准。正常值通常等于或大于0.9且小于1.45,6;0.9以下表明可能存在一些动脉疾病,超过1.4则表明足部血管钙化,数值不准确。

理想情况下,应在患者卧位20分钟后测量ABPI。将BP袖带放置在下肢步态区。临床医生在足部定位动脉有声信号,然后对袖带充气,直至声音消失。袖带放气,当声音再次出现时,记录收缩压。在肱动脉上重复相同的操作。

水肿和炎症(包括充血性心力衰竭、急性或亚急性脂肪皮肤硬化症或血栓性静脉炎)加上感染,通常可导致疼痛。急性疼痛可能导致下肢动脉无法闭塞。此外,高达80%的糖尿病患者或20%的老年人会出现血管钙化,造成人为的高ABPI,使检测不准确。替代试验是AHHD评估。可以在患者坐位或卧位进行该试验,无需在步态区周围使用BP袖带。将足量凝胶置于足背,描绘有声波形(表2)。单相或无有声信号表明需要进行全面的血管评估。出现有声多相(双相/三相)波表明下肢无明显外周血管疾病,可开始加压治疗。应检查足部的温度是否正常,以及是否存在因抬高而变白的依赖型红斑(暗红色)。该体格检查可用于排除血管小体缺陷(局部或节段性动脉闭塞)。此外,还应触诊足背或胫后动脉搏动。

一项2015年的研究记录了200例患者379条腿的AHHD读数结果,并与认证血管实验室的连续下肢多普勒读数进行了比较7。该试验对排除动脉疾病具有特异性(胫后动脉,98.6%;足背动脉,97.8%),但对动脉疾病的诊断不敏感(胫后动脉,37.5%;足背动脉,30.2%)。该试验是一种可靠、简单、快速、便宜的床边排除试验,用于检测伴或不伴糖尿病患者的外周血管疾病。结果与血管钙化无关。

同样,单相多普勒结果或无脉搏应触发节段性下肢双功能多普勒动脉供血研究。在某些情况下,可能需要进行静脉研究,尤其是在可能进行手术或其他静脉干预治疗的情况下。当无法开展传统ABPI研究时(如缺乏多普勒、疼痛、不可压缩血管或时间限制),该试验可以避免加压疗法的延迟。

对于身体其他部位的溃疡,需要充分灌注;检查周围皮肤的温度。检查手臂或腿部远端的局部皮肤是否有依赖型红斑。在中央躯体上,检查该区域是否有水肿或坏死,同时检查循环时间(手指压在皮肤上形成的白色区域应在3秒或更短时间内恢复;否则,可能存在损害)。循环受损可能表明维持性或不可愈性伤口,直至基础缺陷得到纠正。

子声明1B——尽可能明确地确定病因或进行适当转诊

通常,伤口不愈合的原因是“诊断不充分”4。执业医师必须尽可能准确识别伤口病因,考虑血管性下肢溃疡(静脉、混合、动脉、淋巴或组合)、糖尿病足溃疡(神经性、缺血性或混合性)和压力性损伤(必须与潮湿环境相关的皮肤损伤区分);每项均有特定的管理考虑(表3)。其他诊断包括炎症性溃疡(坏疽性脓皮病、血管炎)、恶性溃疡(原发性皮肤、其他继发性恶性肿瘤)、创伤/既往手术、药物以及先天性或获得性共存疾病。一些共存疾病使皮肤处于风险中。皮肤随着老化而变薄。光损伤和遗传性(如大疱性表皮松解、埃勒斯-当洛斯综合征)或获得性(如大疱性类天疱疮、中毒性表皮坏死松解症)皮肤病增加了对创伤的易感性,包括皮肤裂伤。此外,潮湿环境相关皮肤损伤区域可能更容易受到压力损伤或感染。

表3.按类型分类的伤口治疗(©WoundPedia 2021)

子声明1C——审查可能延迟或抑制愈合的辅助因素/合并症(全身性疾病、既往手术、营养、药物、脆弱皮肤)

解决可改变的辅助因素对所有慢性伤口患者都很重要(图2)。通常,为了最佳管理进行适当转诊有助于伤口愈合。

图2.审查伤口愈合的辅助因素和合并症(©WoundPedia 2021)

使用经确认的双问题加拿大营养筛查工具8可以促进营养评估:

1. 在过去6个月内,您是否在未尝试减肥的情况下发生体重下降?(如果患者报告体重减轻但又恢复了,则认为没有减轻)。

2. 您比平时吃得少的情况持续超过一周了吗?

该工具具有许多优点;不需要血液检查或诊断程序,给药简单快速,并且可靠9。任何医疗专业人员均可以快速确定潜在的营养不足,以及是否需要转诊给营养师。

声明2——以患者为中心的问题

子声明2A——疼痛管理(诊断和治疗)

疼痛通常是患者最关注的问题,但医疗保健提供者很少最关注该问题。因此,必须对疼痛也进行量化。通常使用数字评定量表(0-10)(表4)。若报告的疼痛水平为5级或以上,则需要干预。

表4.伤口相关的疼痛管理(©WoundPedia 2021)

疼痛主要分为两种类型——伤害性和神经性(补充图1,https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal)。伤害性疼痛与损伤有关,具有刺激依赖性,通常与疼痛、啃咬、压痛或搏动感有关。神经性疼痛通常为自发性,并描述为灼热、射痛、刺痛或针刺样疼痛。每种类型具有不同的生理基础,需要不同的药物治疗。

最近一项关于与慢性下肢溃疡疼痛相关的局部镇痛药的系统性综述表明,对于慢性下肢溃疡患者,局部乳膏(局部麻醉剂的共晶混合物)优于其他制剂10。此外,还有其他可能与缓解疼痛和策略有关的局部治疗方法,包括在去除敷料时使用硅酮粘合剂来取代其他创伤性更大的丙烯酸粘合剂。

在局部伤口护理的许多环节中可能出现疼痛控制不足的情况11。对于疼痛性敷料更换,必须在换药前的适当时间给予口服药物。在更换敷料时,疼痛通常与伤口病因或其并发症相关;应考虑非药物措施(音乐疗法、冥想、针灸、经皮电神经刺激、顺势疗法、自然疗法和精神疗法)。

总之,患者在疼痛方面的权利涉及到6个C——每例患者均应得到检查、确定病因、解释治疗后果(具有不良反应)、充分控制、程序期间叫停,以及舒适度。最后,医疗保健提供者必须谨记,未记录的疼痛管理等同于无疼痛管理。

子声明2B——评估日常生活活动、运动/锻炼、饮食习惯、心理健康(精神健康)和支持体系(患者护理圈、获得护理和经济限制)

以患者为中心的问题往往涉及支持结构不足,还可能涉及缺乏医疗体系机构,损害获得适当医疗服务的机会。个人心理健康可能会损害患者应对慢性伤口管理的能力,他或她可能需要帮助。同时,也需要社会工作者、出院协调员和临床心理学家来支持社区的系统。

子声明2C——评估习惯(吸烟、饮酒、药物使用、个人卫生)

每根香烟将使局部氧合降低30%,并持续1小时12。香烟和其他烟草产品可能是阻止慢性伤口愈合的主要因素,或作为化脓性汗腺炎患者的促炎刺激物。2017年,在一项涉及450例患者的研究中,单独使用阿片类药物(尤其是>10 mg/日)与伤口尺寸增加和愈合可能性降低有关13。

子声明2D——给予患者教育和支持,以提高治疗依从性(连贯性)

Aujoulat等人14研究了与慢性疾病教育有关的患者权利。他们确定:“目标和结局……既不应由医疗保健专业人员预先定义,也不应局限于某些疾病和治疗相关结局,而应根据每例患者的具体情况和生活重点与其讨论和协商”14。

Moore等人15概述了四个步骤,以增加患者参与护理:

1. 询问患者的观点/了解其病情。

2. 识别恐惧/担忧。

3. 确定对患者重要的因素。

4. 评估患者参与护理的意愿。

声明3——确定可愈性

医疗保健提供者在诊断后必须采取的第一步是确定可愈性,并了解伤口状态可能发生的变化。通常,慢性伤口分为三类——可愈性伤口、维持性伤口和不可愈性伤口。局部伤口护理策略将因分类而异(表5)。

表5.局部伤口护理策略总结;摘自Sibbald等人16(©WoundPedia 2021)

子声明3A——可愈性伤口:充足的血液供应来愈合并治疗病因

可愈性伤口有足够的血液供应来愈合,且病因已经得到纠正。通常,社区中大约三分之二的伤口为可愈性。

子声明3B——维持性伤口:在患者不能或不愿遵守护理计划/医疗保健体系或没有适当资源的情况下,也有充足的血液供应来愈合。

四分之一的伤口是维持性伤口,原因可能是患者的问题(例如,拒绝使用加压绷带)和/或健康系统因素妨碍愈合(例如,无法负担足底压力再分配装置,医疗系统无法为足底供应血液)。

子声明3C——不可愈性伤口:供血不足和/或无法纠正病因(例如,晚期癌症、负蛋白质平衡)

大约5%-10%伤口是不可愈性,通常因为无法治疗或纠正的供血不足、晚期慢性疾病或死亡过程。对于不可愈性伤口的患者,需要解决的首要问题是疼痛、感染并发症、渗出液和异味控制以及日常生活活动。

来自南非伤口愈合协会的13名KOL最近对不可愈性伤口和维持性伤口进行了系统综合审查17。该小组由13名成员组成,负责13项审查、6项最佳实践指南、3项共识研究和6项原始非实验性研究。研究获得的三个主要结论包括需要以患者为中心的护理、由熟练的医疗保健提供者及时干预和以及跨专业的转诊途径17。

声明4——局部伤口护理:监测伤口史和临床检查

子声明4A——记录伤口:位置、直角最长长度×最宽宽度、伤口形状、创面床、渗出液、边缘、潜行、隧道、周围皮肤状况和光电成像(如可用)

伤口记录很重要(表6)。记录伤口的位置和尺寸;尽管从头到脚对齐也很常见,但这些作者建议使用彼此垂直的最长长度和最宽宽度。选择符合机构政策的测量方法;连贯性最重要。注意并监测潜行、隧道、创面床的组织类型、伤口边缘和伤口周围皮肤特征。

表6.伤口记录(©WoundPedia 2021)

子声明4B——清洁:用水、生理盐水或低毒性消毒剂轻轻清洗

对于可愈性伤口,局部伤口护理可能包括锐器手术清创、感染治疗(局部感染、深部和周围感染)以及水分管理。对于不可愈性伤口,最佳护理方法可能集中于腐肉保守型清创、减少细菌和减少水分。在此类情况下,具有一些组织毒性的消毒剂可能比细菌增殖造成进一步的组织损伤导致的感染更可取。

关于伤口清洁的高质量证据非常少(表7);因此,很难得出任何结论,伤口清洁是一个需要进一步研究的主题19。冲洗时,记录进出创面床的溶液量。当整个创面床无法清晰可见或完整时,应谨慎使用。注意不要因过度创伤而损伤创面床。

表7.伤口清洁方法;摘自Nicks等人18(©WoundPedia 2021)

子声明4C——定期适当重新评估并记录伤口

声明5——适当时,清创伤口并充分控制疼痛

清创术是一种清除可能促进感染或作为促炎症刺激物腐肉、碎屑或异物的方法,可延长伤口愈合的炎症阶段,并延迟增殖修复过程。锐器手术清创需要评估供血,以确保其足以愈合。在开始之前,即使是考虑保守清创方法的提供者也必须确保具有适当的能力、实践经验、所需的设备和出血事件支持,以及与其机构的政策和程序一致。

尽管KOL之间确实达成了共识,但对该声明的认同度相对较低,这可能归因于与机构相关的锐器清创限制。该手术需要临床经验、适当的实践经验和设备的可用性来进行手术并在需要时止血。

子声明5A——对于可愈性伤口,考虑使用锐器手术清创(对出血组织);对于维持性伤口/不可愈性伤口,考虑使用保守手术清创

对于可愈性伤口,采用锐器手术清创、敷料或酶的自溶清创、生物(医用蛆虫)或机械清创。对于不愈性伤口和维持性伤口,采用保守手术或其他方法清除无活性腐肉。

患者权利可以仿照《4步临床决策清创指南20》,在患者和临床医生之间达成共识。首先,询问伤口是否能够愈合。如果回答“是”,请根据患者问题和伤口特征选择适当的方法。接下来,研究哪些伤口特征影响清创选择,如继发性感染、疼痛、伤口大小和渗出液。确定清创方法的选择性;当清除坏死组织时,确定是否对健康组织有任何风险。最后,考虑护理环境。一些临床医生和/或资源类型可能无法在所有护理环境中可用。政府监管和机构政策也可能是影响因素20。

子声明5B——评估是否需要采用其他清创方式(敷料、酶、机械或生物进行自溶清创)

自溶清创可通过海藻酸钙、水凝胶和亲水胶体敷料完成。这类清创往往相对无痛,但可能比手术方式慢。酶清创(胶原酶)通常用于手术清创或自溶敷料不可用的情况。这是一种相对缓慢的方法,而且治疗需要开具处方。

机械清创可以使用先进技术完成,例如超声,需要洁净或无菌条件,防止细菌污染和空气中的细菌病原体或颗粒物。漩涡系统可能污染浸入皮肤的区域,并可能造成患者之间的交叉污染。生理盐水湿-干纱布的护理时间密集,去除敷料时伴随疼痛,并且可以清除创面上的健康活性组织。

Moya-López等人21最近发表了一篇关于蛆虫清创治疗慢性伤口的综述。蛆虫疗法比其他一些非手术清创方法更快,并且对失活组织具有选择性。作者得出结论,伤口类型、应用频率和治疗有效性需要更多数据。蛆虫不适用于缺血性伤口以及深层和周围感染尚未得到系统治疗的情况。

声明6——评估和治疗伤口的感染/炎症

伤口感染有两个层次——一个是浅表感染,另一个是深层感染10,12。伤口可以视作一碗汤;表面的薄层类似于伤口的浅表,而汤碗的两侧和底部相当于慢性伤口的周围和深部。

子声明6A——使用局部抗菌剂(银、碘、聚六亚甲基双胍[PHMB]/氯己定、亚甲蓝/结晶紫、表面活性剂)治疗局部感染(3项或以上NERDS标准)

慢性伤口的浅表是一层可局部治疗的薄层细胞。任何三种或三种以上NERDS(不愈合、渗出液增加、红色易碎肉芽、碎屑或死细胞,以及异味)标准均为局部感染体征,可能需要局部抗菌剂治疗。如果伤口可愈合,并且针对病因进行了治疗,则需要4周或更短的时间来改善。临床医生应知道,治疗浅表伤口需要敷料将抗菌剂释放到伤口表面。非释放性敷料将在伤口表面以上起作用,但无法穿透浅表层。这可以防止伤口上方的细菌生长,但可能需要另一种药剂来靶向伤口表层。例如,与一些设计用于完整皮肤的术前抗菌剂相比,抗菌喷雾剂(如氯己定漱口水)的酒精含量通常较少,局部灼热和刺痛减少。一些外用药物释放不同浓度的银或碘,以穿透表层来治疗局部感染。

子声明6B——考虑使用全身性抗菌剂治疗深层和周围感染(3项或3项以上STONEES标准)

外用抗菌药物仅穿透几毫米;深层和周围感染可能需要全身抗菌药物治疗(补充表5,https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal)。STONEES七项标准中的四项代表了伤口的周围特征(汤碗的两侧)——尺寸增大,温度比周围伤口皮肤的镜像温度高出3°F,新的或卫星病灶区域以及周围的蜂窝织炎(红斑或水肿)。当慢性伤口与深层和周围感染相关时,并非总是存在蜂窝织炎,并且在有色皮肤或存在水肿的情况下不易识别红斑。在创面床中,剩下的三个STONEES体征包括骨探测(Os是[拉丁语“骨”])、渗出液增加和异味。

子声明6C——评估并缓解持续性炎症,包括考虑使用抗炎药(外用敷料、全身性药物)

感染性微生物以外的因素可在持续性炎症反应中发挥作用。这些因素包括侵袭细胞(中性粒细胞、巨噬细胞、淋巴细胞)、免疫复合物(血管炎)、肉芽肿性炎症(结节病等)和其他;在选择局部或全身治疗时要考虑这些因素。一些局部抗菌剂具有促炎性,如碘。此外,还有其他可能抗炎的制剂,包括银,以及一些中性制剂,如PHMB纱布/泡沫和龙胆紫/亚甲蓝泡沫。

炎症也可导致浅表和深层伤口的愈合延迟。在临床环境中并非总是可用蛋白酶检测,可能只测量表面而非深层变化。一些感染体征也可能是持续性炎症临床表现的一部分。Sibbald Cube(补充图2(https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal)概述了有无感染的伤口中高蛋白酶可能阻碍伤口浅表和深层的愈合。最近发表的数据表明,生物标志物可以预测下肢静脉性溃疡的愈合轨迹22。在正确的时间进行正确的治疗(生长因子、基质结构和细胞成分的最佳时机)可以更有效地控制蛋白酶、细菌污染、清创和水分控制。

在局部治疗方面,含银和蜂蜜的产品有抗炎作用。这些药物只能短期用于局部感染和炎症。对于全身治疗,一些抗菌剂具有抗炎作用。常见的推荐用于伤口和相关皮肤感染的抗菌剂(有些具有抗炎作用)列于补充表5中(https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal)。

声明7——水分管理

医疗保健提供者必须选择适当的敷料,以匹配伤口特征和个体患者需求(图3)。理想的水分管理取决于伤口的可愈性。

图3.优化水分管理;改编自Sibbald等人16(©WoundPedia 2021)

子声明7A——可愈合性伤口、水分平衡和自溶清创术(藻酸盐、水凝胶、亲水胶体、丙烯酸树脂、薄膜)

在可愈性伤口中,可以通过从推动因素中的水分连续体中选择适当的敷料来实现水分平衡(补充表6,https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal),该表列出了用于从低到高渗出性伤口的敷料。

子声明7B——单独的水分平衡(特级吸收剂、泡沫、海藻酸钙、水纤维、亲水胶体、薄膜、水凝胶)

子声明7C——不可愈性伤口和维持性伤口以及水分减少;如果需要抗菌,低毒性局部麻醉剂:氯己定/PHMB、碘、乙酸

对于有维持性伤口或不可愈性伤口的个体,治疗目标是减少水分和细菌。需要不断重新评估伤口的愈合或恶化情况,可能需要根据表现改变敷料选择。

对于这些伤口,医疗保健提供者需要平衡患者偏好和舒适度,以避免疼痛,以及防止伤口过度干燥。薄纱敷料通常最合适;它们是纱布或织物与凡士林或石蜡涂层的组合。其中还可能含有抗菌剂(例如,氯己定、碘)。

然而,几种敷料可以优化水分管理16。氯己定(0.5%的白色石蜡浸渍在薄纱布中)对革兰氏阳性菌和阴性菌有活性;PHMB是一种非释放泡沫、纱布/包扎带制剂。碘敷料(卡地姆分子或聚维酮碘)具有广谱活性,尽管在存在脓液或渗出液的情况下有效性会有所降低。请注意,长期大面积使用这些敷料可能会产生毒性(如聚维酮碘)。最后,通常应使用纱布将乙酸(0.5%-1%,如稀释的白醋)置于创面上约5-10分钟,常作为旋转加压。这些敷料的pH值较低,对假单胞菌有效;但是,它们可能会选择输出其他微生物16。

子声明7D——伤口包扎:生理盐水湿润(提供水分)或干燥(吸收水分)但不抗菌;PHMB纱布:抗菌、不释放——在伤口上方(留在纱布内),仅不在伤口表面;聚维酮碘或其他抗菌剂浸泡纱布:伤口上方和伤口表面抗菌

生理盐水包扎可用于无严重定植的可愈性伤口。这些敷料的目的不是粘在创面床上,否则在移除敷料时则会有创伤。如果干燥的生理盐水纱布粘在创面床上,则应在使用前湿润纱布,如果纱布粘在一起,则应在去除前再次湿润纱布。然后应选择替代敷料来保持湿润、交互愈合。

声明8——评估愈合率

如果到第4周时伤口没有缩小至少20%-40%,则到第12周时就不太可能愈合(图4)。

图4.如何计算创面表面积

子声明8A——应重新评估愈合停滞(可愈性)的伤口,以确定其他诊断;考虑进行伤口活检、进一步调查和/或转诊至跨专业评估小组来优化治疗。

如果没有新的复杂因素,可以在前4-8周评估愈合轨迹,以预测伤口是否有可能在第12周时愈合9。愈合停滞但可愈合的伤口通常需要全面的跨专业评估,以优化治疗并改善愈合轨迹。这可能需要将伤口重新分类为维持性或不可愈性类别。

声明9——边缘效应

对愈合停滞但可愈合的伤口进行积极治疗。见补充表7(https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal)关于辅助治疗的证据——负压伤口治疗、电刺激、细胞和/或组织产品、皮肤移植物、超声和高压氧治疗(表8)。

表8.辅助治疗

子声明9A——一些积极模式的证据较弱或不一致,应仅在对患者进行跨专业评估并定期重新评估后使用

子声明9B——皮肤移植物不同但阳性的证据,此时基于细胞和/或组织的产品可能具有成本效益,也可能不具有成本效益

许多活性疗法在伤口愈合的工具箱中出现又消失了。这些疗法不仅需要刺激愈合,而且必须在当地卫生系统的背景下具有成本效益。其中一些疗法针对急性伤口的证据优于慢性不愈性伤口(例如,糖尿病足手术后的负压伤口治疗、分层皮肤移植物),尤其是在病因没有纠正或无法纠正的情况下。如果选择了活性治疗,则必须进行一致和准确的伤口评估,以便确定伤口在任一方向上的进展,并且如果伤口不在愈合轨迹上,则及时停止治疗。在对这些疗法提出明确的使用建议之前,需要对其进行更高质量的随机对照试验。

声明10——组织支持

子声明10A——组织上的支持可能包括有利于跨专业教育和以患者为中心的护理的文化、标准化循证方案、充足的人员配置以及既定的质量改进计划,其中可能包括审计、流行率和发生率研究以及患者导航

指导原则实施的有效组织计划要素如下23:

· 考虑当地情况,评估组织准备情况和实施障碍。

· 让所有成员(无论是直接还是间接支持职能)参与执行过程。

· 提供持续的教育机会,加强最佳实践。

· 一个或多个有资格的个人应提供教育和执行过程所需的支持。

· 提供机会反思个人和组织执行指导原则的经验。

伤口成功愈合的障碍通常与卫生系统有关,而非缺乏医疗保健提供者的知识。在从急性护理到长期护理的连续统一体中,需要更好地协调护理,以及处方集和最佳实践的标准化。这可以通过情境学习、改变医疗保健体系来促进复杂患者问题的跨专业评估以及打破医疗组织内部和之间的障碍来实现。这就要求机构投入资源来进行跨专业的伤口护理实践教育,并以持续质量倡议的形式收集和定期审查伤口护理数据结局。

慢性伤口患者的资源通常有限,来自较低阶层的社会经济背景。使用患者导航模式促进转诊并将家庭护理提供者与护理协调员联系起来,以获得系统资源是一种前进方向24,25。然而,只有当团队成员作为协调跨专业模式的一部分联系在一起时,才获得成功。这些卫生系统的变化可以增加价值。

Porter医疗保健模式将患者的声音与医疗保健提供者、付款人、政策制定者甚至政治家联系起来,为医疗费用赋予价值26。为了改变系体系,政策制定者和政治家必须意识到伤口护理患者和医疗保健提供者面临的不一致和不平等,这是改善以患者为中心的伤口护理的第一步。

结论

这10项循证声明在重复调查中获得了KOL的共识。提供推动因素旨在帮助将WBP范例传播到实践中。我们已经做出了一致的努力,强调早期主动评估伤口愈合轨迹的重要性。通过在伤口转为慢性之前进行干预,对患者、医疗保健提供者、付款人和政策制定者均有益处。面对不断增加的医疗费用和人口老龄化,这一点现在比以往任何时候都更为重要。

利益冲突声明

LeBlanc博士披露,她是Hollister、Coloplast、3M和Mölnlycke的发言人。Ayello博士披露,她已获得Sage/Stryker和Calmoseptine的教育/研究资助。Sibbald博士获得了Mölnlycke、Calmoseptine和安大略省政府对ECHO皮肤和伤口项目的资助。

资金支持

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

补充资料

补充表格和数字可以在登录会员区后,通过登录WCET®杂志的电子版https://wcetn.org/page/ReadJournal获得。

补充数据

Author(s)

R Gary Sibbald*

MD, DSc (Hons), MEd, BSc, FRCPC (Med Derm), FAAD, MAPWCA, JM, Professor of Medicine and Public Health, Director, International Interprofessional Wound Care Course and Masters of Science in Community Health, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada

James A Elliott

MMSc, Project Manager, ECHO Ontario Skin and Wound Care, Toronto Regional Wound Healing Clinic, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

Reneeka Persaud-Jaimangal

MD, MScCH, IIWCC, Clinical Coordinator, ECHO Ontario Skin and Wound Care, Toronto Regional Wound Healing Clinic, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

Laurie Goodman

MHScN, RN, IIWCC, Course Coordinator and Co-Director, WoundPedia, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

David G Armstrong

DPM, MD, PhD, Professor of Surgery and Director, Southwestern Academic Limb Salvage Alliance, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, USA

Catherine Harley

RN, EMBA, Chief Executive Officer, Nurses Specialised in Wound, Ostomy & Continence Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Sunita Coelho

BScN, RN, IIWCC, Toronto Regional Wound Healing Clinic, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

Nancy Xi

MD, CCFP, Family Physician, Trillium Health Partners, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

Robyn Evans

MD, MSc, Director, Wound Healing Clinic, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Dieter O Mayer

MD, FEBVS, FAPWCA, Department of Surgery, Cantonal Hospital of Fribourg, Switzerland

Xiu Zhao

MD, CCFP, Family Physician, Trillium Health Partners, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

Jolene Heil

BScN, CNS, IIWCC, MClSc, Advanced Practice Nurse, Providence Care, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

Bharat Kotru

PhD, IIWCC, Podiatrist, Max Super Speciality Hospital, Bathinda, Punjab, India

Barbara Delmore

PhD, RN, CWCN, MAPWCA, IIWCC, FAAN, Senior Nurse Scientist, Center for Innovations in the Advancement of Care, NYU Langone Health, New York, NY, USA

Kimberly LeBlanc

PhD, RN,NSWOC, WOCC(C), FCAN, Chair, Wound Ostomy Continence Institute, Nurses Specialised in Wound Ostomy Continence Care Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Elizabeth A Ayello

PhD, MS, BSN, RN, CWON, ETN, MAWPCA, FAAN, Professor Emeritus, Excelsior College of Nursing, Albany, New York, NY, USA; Senior Advisor, The John A. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, New York, NY, USA; President, Ayello, Harris, & Associates, New York, NY, USA

Hiske Smart

MA, RN, PG Dip (UK), IIWCC, Manager, Wound Care & Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Unit, King Hamad University Hospital, Muharraq, Kingdom of Bahrain

Gulnaz Tariq

MSc, RN, PG Dip (PAK), BSc, IIWCC, MSc (UK), Manager, Wound Care/Surgical Units, Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Afsaneh Alavi

MD, Senior Consultant, Department of Dermatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Ranjani Somayaji

BScPT, MD, MPH, FRCPC, Assistant Professor, Departments of Medicine; Microbiology, Immunology and Infectious Disease; and Community Health Sciences; Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada

References

- Sackett D, Rosenberg W, Gray J, Haynes R, WS R. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996;312(7023):71–2.

- Brownson RC, Eyler AA, Harris JK, Moore JB, Tabak RG. Getting the word out: new approaches for disseminating public health science. J Public Health Manage Pract 2018;24(2):102–11.

- Keown K, Van Eerd D, Irvin E. Stakeholder engagement opportunities in systematic reviews: knowledge transfer for policy and practice. J Continuing Educ Health Prof 2008;28(2):67–72.

- Minkler M, Salvatore A. Participatory approaches for study design and analysis in dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 192–212.

- Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2017;135(12):e726–79.

- Beaumier M, Murray BA, Despatis MA, et al. Best practice recommendations for the prevention and management of peripheral arterial ulcers. Toronto, ON: Wounds Canada; 2020. p. 1–75.

- Alavi A, Sibbald RG, Nabavizadeh R, Valaei F, Coutts P, Mayer D. Audible handheld Doppler ultrasound determines reliable and inexpensive exclusion of significant peripheral arterial disease. Vascular 2015;23(6):622–9.

- Canadian Nutrition Society, Canadian Malnutrition Task Force. Canadian Nutritional Screening Tool (CNST); 2014 [cited 2021 Jan 14]. Available from: http://nutritioncareincanada.ca/sites/default/uploads/files/CNST.pdf

- Laporte M, Keller HH, Payette H, et al. Validity and reliability of the new Canadian Nutrition Screening Tool in the ‘real-world’ hospital setting. Eur J Clin Nutr 2015;69(5):558–64.

- Purcell A, Buckley T, King J, Moyle W, Marshall A. Topical analgesic and local anesthetic agents for pain associated with chronic leg ulcers: a systematic review. Adv Skin Wound Care 2020;33(5): 240–51.

- Woo KY, Coutts PM, Price P, Harding K, Sibbald RG. A randomized crossover investigation of pain at dressing change comparing 2 foam dressings. Adv Skin Wound Care 2009;22(7):304–10.

- Jensen J, Goodson W, Hopf H, Hunt T. Cigarette smoking decreases tissue oxygen. Arch Surg 1991;126(9):1131–4.

- Shanmugam VK, Couch KS, McNish S, Amdur RL. Relationship between opioid treatment and rate of healing in chronic wounds: opioids in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2017;25(1):120–30.

- Aujoulat I, d’Hoore W, Deccache A. Patient empowerment in theory and practice: polysemy or cacophony? Patient Educ Couns 2007;66(1):13–20.

- Moore Z, Butcher G, Corbett LQ, et al. Exploring the concept of a team approach to wound care: managing wounds as a team. J Wound Care 2014;23 Suppl 5b:S1–S38.

- Sibbald RG, Elliott JA, Ayello EA, Somayaji R. Optimizing the moisture management tightrope with Wound Bed Preparation 2015. Adv Skin Wound Care 2015;28(10):466–76.

- Boersema GC, Smart H, Giaquinto-Cilliers MGC, et al. Management of nonhealable and maintenance wounds: a systematic integrative review and referral pathway. Adv Skin Wound Care 2021;34(1):11–22.

- Nicks BA, Ayello EA, Woo K, Nitzki-George D, Sibbald RG. Acute wound management: revisiting the approach to assessment, irrigation, and closure considerations. Int J Emerg Med 2010;3(4):399–407.

- Moulin D, Boulanger A, Clark A, et al. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain: revised consensus statement from the Canadian Pain Society. Pain Res Manage 2014;19(6):328–35.

- Sibbald R, Niezgoda J, Ayello E. Debridement. In: Baranoski S, Ayello EA, editors. Wound care essentials: practice principles. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2020.

- Moya-López J, Costela-Ruiz V, García-Recio E, Sherman RA, De Luna-Bertos E. Advantages of maggot debridement therapy for chronic wounds: a bibliographic review. Adv Skin Wound Care 2020;33(10):515–25.

- Stacey MC. Biomarker directed chronic wound therapy – a new treatment paradigm. J Tissue Viability 2020;29(3):180–3.

- Registered Nurses Association of Ontario. Assessment and management of foot ulcers for people with diabetes. 2nd ed. Toronto, ON: Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario; 2013.

- Freeman HP. The origin, evolution, and principles of patient navigation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21(10):1614–7.

- Freund KM. Implementation of evidence-based patient navigation programs. Acta Oncol 2017;56(2):123–7.

- Porter ME, Lee TH. The strategy that will fix health care. Harvard Business Review. 2013 [cited 2021 Jan 14]. Available from: https://hbr.org/2013/10/the-strategy-that-will-fix-health-care