Volume 42 Number 3

WHAM evidence summary: turmeric for treating radiation dermatitis

Emily Haesler

Keywords radiation dermatitis, turmeric, curcumin, curcuma longa, radiodermatitis

For referencing Haesler E. WHAM evidence summary: turmeric for treating radiation dermatitis. WCET® Journal 2022;42(3):34-37

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.42.3.34-37

Clinical question

What is the best available evidence for turmeric products for treating radiation dermatitis?

Summary

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) is a spice harvested in India and other Asian countries that has traditionally been used to treat many ailments, including skin conditions. It is recognised as having anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antiseptic effects that could play a role in reducing radiation dermatitis, which frequently occurs during radiotherapy because of morphological skin changes. Level 1 evidence1 suggested oral turmeric taken throughout the course of radiotherapy is associated with a delay in onset and severity of radiation dermatitis. Level 1 evidence2–4 reporting on topical turmeric preparations was mixed. Two small studies2,3 found that topical turmeric reduces onset and severity of radiation dermatitis, while a third, larger study4 found no difference in effect compared to other topical preparations. More research on the potential benefits from application of a turmeric-based product during radiotherapy is required.

Clinical practice recommendations

All recommendations should be applied with consideration to the wound, the person, the health professional and the clinical context.

|

Oral turmeric could be considered as an adjunct therapy to reduce the severity of radiation dermatitis in selected people receiving radiation therapy (Grade B). There is insufficient evidence to make a graded recommendation on the use of topical turmeric preparations to reduce the severity of radiation dermatitis |

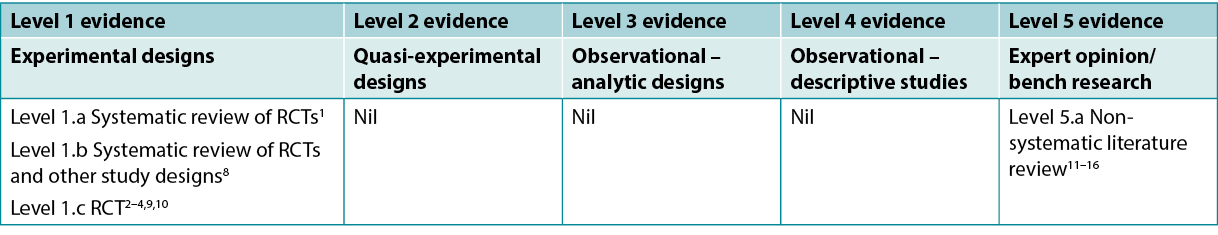

Sources of evidence: search and appraisal

This summary was conducted using methods published by the Joanna Briggs Institute5–7. The summary is based on a systematic literature search combining search terms related to turmeric/curcumin/curcuma longa and radiation dermatitis. Studies reporting turmeric for management of other wounds or skin conditions (e.g., psoriasis) were excluded. Searches were conducted in the CINAHL, PubMed® and Hinari databases and in the Cochrane Library for evidence conducted in humans published up to April 2022 in English. Levels of evidence for intervention studies are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Levels of evidence for clinical studies

Background

Turmeric (C. longa) is a spice prepared from a rhizome that is used as a traditional medicine in India and other Asian countries. Curcumin, which is the active chemical substance in turmeric17,18, is described as having anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiseptic and anti-cancer effects15,18–20.

Radiation dermatitis is a common side effect that affects up to 95% of people receiving radiotherapy for the management of breast cancer4,14,16. Radiotherapy can damage epithelial cells, decreasing the thickness of the epidermis and leading to increasing severity of signs and symptoms as radiotherapy continues, including warmth, pruritus, erythema, oedema, exudate, burning and pain21. It is theorised that curcumin may be effective in reducing the morphological changes that occur to the skin during radiation therapy by decreasing expression of inflammatory cytokines, growth factors and tumour necrosis factor2,12,14,15. Essentially, the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of curcumin are considered advantageous in protecting against the processes that lead to radiation dermatitis14.

Clinical evidence

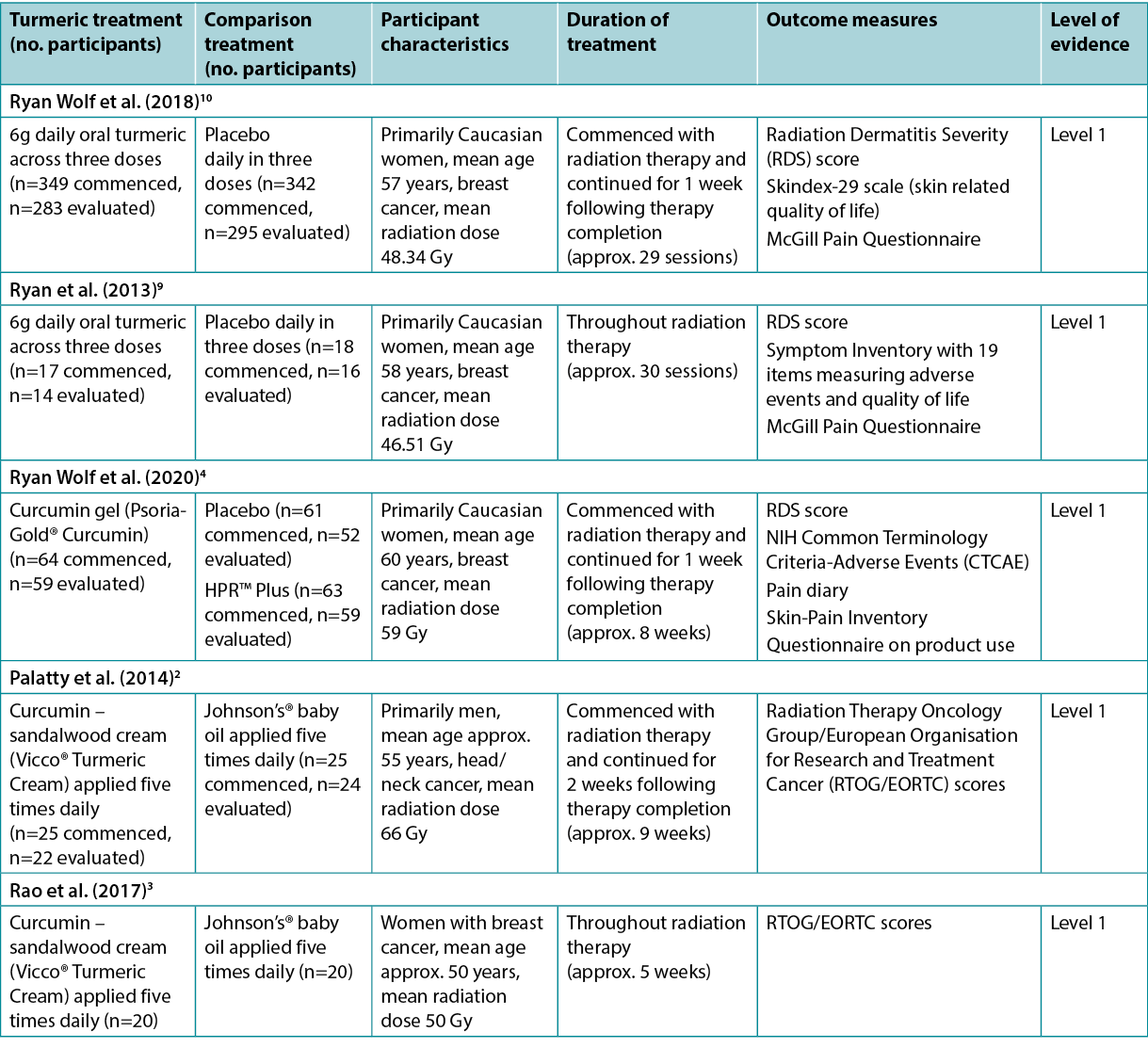

The evidence on turmeric products used to treat radiation dermatitis is summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of the evidence

Oral turmeric to treat radiation dermatitis

A meta-analysis1 at low risk of bias reported the use of oral curcumin for people receiving radiotherapy. This meta-analysis was conducted to inform an evidence-based clinical guideline22 and included two randomised clinical trials (RCTs)9,10 (n=716). In both the RCTs, people with breast cancer received either 6g curcumin daily (across three doses) or placebo, commencing at the start of radiotherapy and concluding 1 week after radiotherapy finished. There was a reduced risk of experiencing Grade 2 or higher radiation dermatitis associated with oral curcumin (risk ratio [RR]=0.64, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.42 to 0.96, absolute risk reduction [ARR]=48 fewer cases per 1,000), but the mean difference in Radiation Dermatitis Severity (RDS) score was low (0.8 lower)1 and the RDS score was not statistically significantly different between groups at the end of treatment (p=0.55)22. The evidence was of low certainty and the withdrawal rate was high (curcumin group 18% versus control group 14%)22. The guideline developers made no recommendation on curcumin primarily due to potential interaction with medications, lack of cost-effectiveness data, and small anticipated desirable effects22 (Level 1).These studies were also reported in other reviews8,12–16 that were at higher risk of bias but that reached similar conclusions that oral curcumin was associated with some positive outcomes (Level 1 and 5).

Topical turmeric to treat radiation dermatitis

An RCT4 (n=191) at low risk of bias compared curcumin gel (4% concentration) to HPR™ Plus (described as a white lotion, FDA-approved medical device) to a placebo gel for reducing the severity of radiation dermatitis in people with breast cancer. The topical preparations were applied three times daily from the base of the neck to underneath the breast fold, including the side of the breast and under the arm, commencing with the start of radiotherapy and continuing until 1 week after therapy ceased. There were no statistically significant differences in mean RDS scores (curcumin 2.68 versus HPR™ Plus 2.64 versus placebo 2.63, p=0.929) or rate of moist desquamation (curcumin 25.42% versus HPR™ Plus 20.34% versus placebo 22.64%, p=0.805)4. This study had overall low rates of radiation dermatitis, and some potential benefits of turmeric therapy were reported in sub-analyses, but the study was not designed to measure these effects (Level 1).

An RCT2 (n=50) at moderate risk of bias compared the effect of a topical turmeric–sandalwood cream (16% turmeric extract) to a control (baby oil) for treating radiation dermatitis in people with head and neck cancer. The treatment for both groups was applied five times daily, from the first day of radiotherapy until 2 weeks after therapy concluded (approximately 9 weeks). After 2 weeks, no participants had experienced radiation dermatitis. From week 3 to week 7 the incidence of radiation dermatitis increased in both groups, with statistically significantly lower rates in the turmeric-based cream group in week 3 (12% versus 41.67%, p<0.045) and week 4 (37.5% versus 75%, p<0.028). Severity of radiation dermatitis evaluated using the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group/European Organisation for Research and Treatment Cancer (RTOG/EORTC) score was statistically significantly lower for the turmeric-based cream group from week 3 until conclusion of the study (p<0.05 for all). Grade 3 radiation dermatitis occurred less often in the turmeric-based cream group (9.5% versus 37.5%, p<0.01) and no participants in the study experienced Grade 4 radiation dermatitis2 (Level 1).

A more recent RCT3 (n=50) at moderate risk of bias conducted by the same research team2 explored topical turmeric–sandalwood cream (16% turmeric extract) for women with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy. The comparator was baby oil, and the treatment regimen was the same as in the study above2. At the end of the second week of radiotherapy, the turmeric-based cream group had a statistically significantly lower rate of radiation dermatitis (32% versus 75%, p=0.0025). In both groups, rates of radiation dermatitis increased throughout the trial, but were statistically significantly lower in the turmeric-based cream group at every weekly measurement (p<0.05 for all)3 (Level 1).

Considerations for use

- Patient-reported outcomes, including pain and skin-related quality of life, were not statistically significantly different compared to a placebo for people taking oral curcumin10 or for people using topical curcumin4.

- Few adverse events have been reported in the literature8–10,12,13. Some evidence indicates curcumin can increase oxalate levels in the kidneys, contributing to development of kidney stones11. Potential to exacerbate gallstone symptoms has also been reported8.

- Curcumin has low bioavailability, which means it is poorly absorbed and used by the body8,10,12,13 and excreted rapidly8,16. Ongoing research is attempting to develop delivery mechanisms (e.g., encapsulation within nanoparticle carriers and developing water-soluble formulations) that will increase its clinical utility10,16.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest in accordance with International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) standards.

About wham collaborative evidence summaries

The WHAM Collaborative evidence summaries are consistent with methodology published in Munn, Lockwood and Moola23.

Methods are outlined in resources published by the Joanna Briggs Institute5–7 and on the WHAM Collaborative website: http://WHAMwounds.com. WHAM evidence summaries undergo peer review by an international, multidisciplinary Expert Reference Group. WHAM evidence summaries provide a summary of the best available evidence on specific topics and make suggestions that can be used to inform clinical practice. Evidence contained within this summary should be evaluated by appropriately trained professionals with expertise in wound prevention and management, and the evidence should be considered in the context of the individual, the professional, the clinical setting and other relevant clinical information.

Copyright ©2021 Wound Healing and Management Collaboration, Curtin Health Innovations Research Institute, Curtin University, WA, Australia.

WHAM证据总结:使用姜黄治疗放射性皮炎

Emily Haesler

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.42.3.34-37

临床问题

姜黄产品用于治疗放射性皮炎的最佳可用证据是什么?

总结

姜黄(Turmeric,学名Curcuma longa)是产于印度和其他亚洲国家的一种香料,传统上被用来治疗许多疾病,包括皮肤病。它被认为具有抗炎、抗氧化和抗菌作用,可以在减少放射性皮炎方面发挥作用,放射性皮炎在放疗期间由于皮肤的形态变化而经常发生。1级证据1表明,在整个放射治疗过程中口服姜黄与放射性皮炎的发生延迟和严重程度相关。关于外用姜黄制剂的1级证据2-4报告参差不齐。两项小型研究2,3发现,外用姜黄可降低放射性皮炎的发生率和严重程度,而第三项规模较大的研究4发现,与其他外用制剂相比,效果无差异。因此需要对放射治疗期间应用姜黄产品的潜在获益进行更多研究。

临床实践建议

采用所有建议时,应考虑伤口、患者、专业医护人员和临床环境。

|

口服姜黄可以考虑作为一种辅助治疗,以降低接受放射治疗的特定人群的放射性皮炎的严重程度(B级)。 尚无足够的证据对使用外用姜黄制剂来降低放射性皮炎的严重程度作出分级建议。 |

证据来源检索和评价

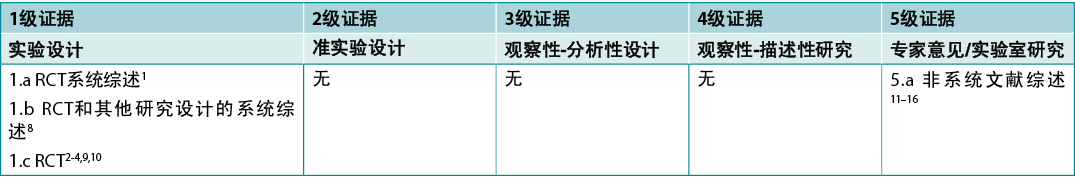

本总结是采用乔安娜·布里格斯研究所公布的方法进行的5-7。本总结基于系统性文献检索,结合了姜黄/姜黄素和放射性皮炎相关的检索词。报告姜黄用于治疗其他伤口或皮肤病(如银屑病)的研究被排除在外。在CINAHL、

PubMed®、Hinari数据库和Cochrane图书馆中检索了截至2022年4月以英文发表的人类证据。干预性研究的证据水平见表1。

表1.临床研究的证据水平

背景

姜黄是一种由根茎制成的香料,在印度和其他亚洲国家被用作传统药物。姜黄素是姜黄17,18中的活性化学物质,被描述为具有抗炎、抗氧化、抗菌和抗癌作用15,18–20。

放射性皮炎是一种常见的副作用,多达95%接受放射治疗的乳腺癌患者受此影响4,14,16。放射治疗会损伤上皮细胞,使表皮厚度减少,并随着放疗的持续进行,导致体征和症状越来越严重,包括发热、瘙痒、红斑、水肿、渗出、灼痛和疼痛21。理论上,姜黄素可能通过减少炎性细胞因子、生长因子和肿瘤坏死因子的表达,有效减少放射治疗期间皮肤发生的形态变化2,12,14,15。从本质上讲,姜黄素的抗炎和抗氧化特性被认为有利于防止放射性皮炎的发生14。

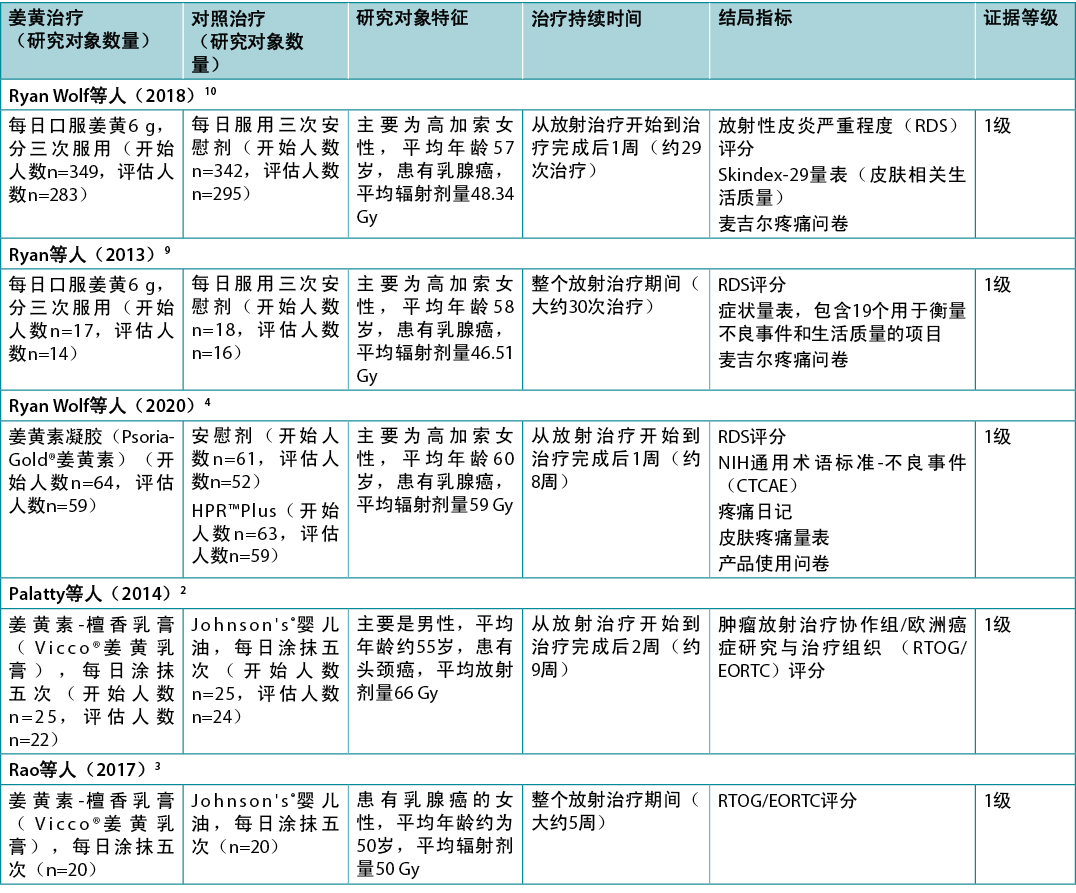

临床证据

表2中总结了关于姜黄产品用于治疗放射性皮炎的证据。

表2.证据总结

口服姜黄治疗放射性皮炎

一项低偏倚风险的荟萃分析1报告了接受放射治疗的人使用口服姜黄素的情况。这项荟萃分析旨在为循证临床指南22提供参考,其中包括两项随机临床试验(RCT)9,10(n=716)。在这两项随机临床试验中,乳腺癌患者每天接受6克姜黄素(分三次服用)或安慰剂,从放疗开始时开始,到放疗结束后1周结束。与口服姜黄素相关的2级或更高级别的放射性皮炎的风险降低(风险比[RR]=0.64,95%置信区间[CI]=0.42至0.96,绝对风险降低[ARR]=每千例减少48例),但放射性皮炎严重程度(RDS)评分的平均差异较低(降低0.8)1,治疗结束时各组间的RDS评分无统计学显著差异(P=0.55)22。证据的确定性低,而且退出率高(姜黄素组18%,对照组14%)22。指南制定者未对姜黄素提出建议,主要原因是与药物有潜在的相互作用,缺乏成本效益数据,以及预期的理想效果较小22(1

级)。这些研究在其他偏倚风险较高的综述中也有报告8,12-16,但得出的结论相似,即口服姜黄素与一些积极结局相关(1级和5级)。

外用姜黄治疗放射性皮炎

一项低偏倚风险的RCT4(n=191)比较了姜黄素凝胶(4%浓度)与HPR˛ Plus(描述为白色乳液,经FDA批准的医疗设备)与安慰剂凝胶,以降低乳腺癌患者放射性皮炎的严重程度。外用制剂从颈部底部到乳房皱襞下方,包括乳房侧面和手臂下方,每天涂抹三次,从放射治疗开始持续到治疗停止后1周。平均RDS评分(姜黄素2.68,HPR˛ Plus 2.64,

安慰剂2.63,p=0.929)或湿性脱屑率(姜黄素25.42%,HPR˛ Plus 20.34%,安慰剂

22.64%,p=0.805)无统计学显著差异4。这项研究的放射性皮炎发生率总体较低,在子分析中报告了姜黄治疗的一些潜在获益,但该研究并非旨在衡量这些效果(1级)。

一项中等偏倚风险的RCT2(n=50)比较了外用姜黄-檀香乳膏(16%姜黄提取物)与对照组(婴儿油)在治疗头颈癌患者放射性皮炎方面的效果。两组的治疗都是每天五次,从放射治疗的第一天开始到治疗结束后2周(大约9周)。2周后,没有研究对象出现放射性皮炎。从第3周到第7周,两组的放射性皮炎发生率均有所増加,在第3周(12%与41.67%,P<0.045)和第4周(37.5%与

75%,P<0.028),姜黄乳膏组的发生率在统计学上显著降低。从第3周到研究结束,使用肿瘤放射治疗协作组/欧洲癌症研究与治疗组织(RTOG/EORTC)评分评估的放射性皮炎严重程度,姜黄乳膏组在统计学上显著降低(所有P<0.05)。姜黄乳膏组中3级放射性皮炎的发生率较低(9.5%与37.5%,P<0.01),研究中没有研究对象出现4级放射性皮炎2(1级)。

同一研究小组2最近进行的一项中等偏倚风险的RCT3(n=50)探讨了针对接受放射治疗的乳腺癌女性外用的姜黄-檀香乳膏(16%姜黄提取物)。对照是婴儿油,治疗方案与上述研究相同2。在放疗第二周结束时,姜黄乳膏组的放射性皮炎发生率在统计学上显著较低(32%与75%,P=0.0025)。在整个试验过程中,两组的放射性皮炎发生率均有所上升,但在每周的测量中,姜黄乳膏组的发生率在统计学上显著较低(所有P<0.05)3(1级)。

使用注意事项

- 患者报告的结局,包括疼痛和与皮肤相关的生活质量,与口服姜黄素10或使用外用姜黄素4的人的安慰剂相比,没有统计学上的显著差异。

- 文献中很少报告不良事件8–10,12,13。有证据显示,姜黄素可以増加肾脏中的草酸盐水平,从而导致肾结石的形成11。也有报告称,有可能加剧胆结石症状8。

- 姜黄素的生物利用率很低,这意味着它很难被人体吸收和利用8,10,12,13,并迅速排出体外8,16。正在进行的研究试图开发递送机制(例如,封装在纳米颗粒载中和开发水溶性制剂),这将増加其临床效用10,16。

利益冲突

根据国际医学期刊编辑委员会(ICMJE)的标准,作者声明无利益冲突。

关于WHAM的协作证据总结

WHAM的协作证据总结与Munn、Lockwood和Moola23发表的方法一致。

Joanna Briggs Institute5-7和WHAM合作网站(http://WHAMwounds.com)发布的资源列出了这些方法。WHAM证据总结经过国际多学科专家参考小组的同行评审。WHAM证据总结提供了关于特定主题的最佳可用证据的总结,并提出了可用于指导临床实践的建议。本总结中包含的证据应由经过适当培训的具有伤口预防和管理专业知识的专业人士进行评价,并应根据个人、专业人士、临床环境以及其他相关临床信息考虑证据。

版权所有˝2021澳大利亚西澳州科廷大学科廷健康创新研究所伤口愈合与管理协作组织

Author(s)

Emily Haesler

PhD Post Grad Dip Adv Nurs (Gerontics) BNurs Fellow Wounds Australia

Adjunct Professor Wound Healing and Management Collaborative, Curtin Health Innovation Research Institute, Curtin University, WA

References

- Ginex PK, Backler C, Croson E, Horrell LN, Moriarty KA, Maloney C, Vrabel M, Morgan RL. Radiodermatitis in patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum 2020;47(6):E225-E36.

- Palatty PL, Azmidah A, Rao S, Jayachander D, Thilakchand KR, Rai MP, Haniadka R, Simon P, Ravi R, Jimmy R, D’Souza P F, Fayad R, Baliga MS. Topical application of a sandal wood oil and turmeric based cream prevents radiodermatitis in head and neck cancer patients undergoing external beam radiotherapy: a pilot study. Br J Radiol 2014;87(1038):20130490.

- Rao S, Hegde SK, Baliga-Rao MP, Lobo J, Palatty PL, George T, Baliga MS. Sandalwood oil and turmeric-based cream prevents ionizing radiation-induced dermatitis in breast cancer patients: clinical study. Medicines (Basel) 2017;4(3).

- Ryan Wolf J, Gewandter JS, Bautista J, Heckler CE, Strasser J, Dyk P, Anderson T, Gross H, Speer T, Dolohanty L, Bylund K, Pentland AP, Morrow GR. Utility of topical agents for radiation dermatitis and pain: a randomized clinical trial. Supp Care Cancer 2020;28(7):3303–11.

- Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual; 2017. Available from: https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/The Joanna Briggs Institute.

- Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. New JBI grades of recommendation. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2013.

- The Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. Supporting document for the Joanna Briggs Institute levels of evidence and grades of recommendation. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2014. Available from:www.joannabriggs.org

- Vaughn AR, Branum A, Sivamani RK. Effects of turmeric (Curcuma longa) on skin health: a systematic review of the clinical evidence. Phytother Res 2016;30(8):1243–64.

- Ryan JL, Heckler CE, Ling M, Katz A, Williams JP, Pentland AP, Morrow GR. Curcumin for radiation dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of thirty breast cancer patients. Radiat Res 2013;180(1):34–43.

- Ryan Wolf J, Heckler CE, Guido JJ, Peoples AR, Gewandter JS, Ling M, Vinciguerra VP, Anderson T, Evans L, Wade J, Pentland AP, Morrow GR. Oral curcumin for radiation dermatitis: a URCC NCORP study of 686 breast cancer patients. Supp Care Cancer 2018;26(12):1543–52.

- Watts R. Evidence summary: turmeric (curcumin) in wound management limited resources communities. Wound Pract Res 2017;25(3):158–9.

- Akbari S, Kariznavi E, Jannati M, Elyasi S, Tayarani-Najaran Z. Curcumin as a preventive or therapeutic measure for chemotherapy and radiotherapy induced adverse reaction: a comprehensive review. Food Chem Toxicol 2020;145:111699.

- Karaboga Arslan AK, Uzunhisarcıklı E, Yerer MB, Bishayee A. The golden spice curcumin in cancer: a perspective on finalized clinical trials during the last 10 years. J Cancer Res Ther 2022;18(1):19–26.

- Farhood B, Mortezaee K, Goradel NH, Khanlarkhani N, Salehi E, Nashtaei MS, Najafi M, Sahebkar A. Curcumin as an anti-inflammatory agent: implications to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. J Cell Physiol 2019;234(5):5728–40.

- Verma V. Relationship and interactions of curcumin with radiation therapy. World J Clin Oncol 2016;7(3):275–83.

- Zoi V, Galani V, Tsekeris P, Kyritsis AP, Alexiou GA. Radiosensitization and radioprotection by curcumin in glioblastoma and other cancers. Biomed 2022;10(2):312.

- Akbik D, Ghadiri M, Chrzanowski W, Rohanizadeh R. Curcumin as a wound healing agent. Life Sci (1973) 2014;116(1):1–7.

- Mohanty C, Sahoo SK. Curcumin and its topical formulations for wound healing applications. Drug Discov Today 2017;22(10):1582–92.

- Maheshwari RK, Singh AK, Gaddipati J, Srimal RC. Multiple biological activities of curcumin: a short review. Life Sci (1973) 2006;78(18):2081–7.

- Ahangari N, Kargozar S, Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Baino F, Pasdar A, Sahebkar A, Ferns GAA, Kim HW, Mozafari M. Curcumin in tissue engineering: a traditional remedy for modern medicine. Biofactor 2019;45(2):135–51.

- Haesler, E. Wound dressings for treating of radiation dermatitis: a WHAM evidence summary. Wound Pract Res 2021;29(3):176–9.

- Gosselin T, Ginex PK, Backler C, Bruce SD, Hutton A, Marquez CM, Shaftic AM, Suarez LV, Moriarty KA, Maloney C, Vrabel M, Morgan RL. ONS guidelines™ for cancer treatment-related radiodermatitis. Oncol Nurs Forum 2020;47(6):654–70.

- Munn Z, Lockwood C, Moola S. The development and use of evidence summaries for point of care information systems: a streamlined rapid review approach. Worldview Evid Based Nurs 2015;12(3):131–8.