Volume 42 Number 4

The meaning of diabetes for individuals who develop diabetic foot ulcer: a qualitative study informed by social constructivism and symbolic interactionism frameworks

Idevania G Costa and Pilar Camargo-Plazas

Keywords patient experience, self-management, diabetic foot, diabetes mellitus, meaning

For referencing Costa IG and Camargo-Plazas P. The meaning of diabetes for individuals who develop diabetic foot ulcer: a qualitative study informed by social constructivism and symbolic interactionism frameworks. WCET® Journal 2022;42(4):41-47

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.42.4.41-47

Submitted 28 June 2022

Accepted 7 September 2022

Abstract

Objective This qualitative inquiry explored the meaning associated with diabetes for people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes who developed diabetic foot ulcer (DFU).

Methodology This qualitative study used a social constructivism and symbolic interactionism (SI) framework to guide the study design. The participants for this study were 30 adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes and a DFU who met the research criteria and attended a wound care clinic in Ontario, Canada, between April and August 2017.

Results Qualitative content analysis revealed three major subcategories that represent the core category (the meaning of diabetes) along with participants’ perception of having diabetes and its particular complication – 1) diabetes is a life-long disease that you need to live with, 2) diabetes can damage your body, and 3) diabetes can kill you slowly.

Conclusions The complexity of self-care and the consequences of unregulated diabetes influenced participants’ perception, meaning, motivation, actions and reactions to diabetes. Understanding that each person with diabetes is unique and may experience or are affected by the disease in different ways helps healthcare providers (HCPs) to better understand how to address each individual’s unique and complex needs.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a serious metabolic disorder with increasing prevalence worldwide. It is caused by the absence or inability to produce insulin to adequately exert its effects on glycaemic control1. In Canada, preventing the disease as well as its proper management is considered a healthcare priority2, particularly because approximately 549 new cases of diabetes are diagnosed among Canadians each day3, where 90% of all diagnosed cases are type 2 diabetes, 9% are type 1 and the remaining 1% consists of other types of diabetes4.

Type 2 diabetes in particular is increasing the most due to factors such as rising levels of obesity, unhealthy diets and a sedentary lifestyle. However, levels of type 1 diabetes are also increasing. For example, in 2000, it was estimated that approximately 151 million adults worldwide had diabetes. Interestingly, in 2010, members of the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) projected that by 2025 about 438 million people would have diabetes5. However, the number is in fact greater; in 2021 more than half a billion (537 million) people were estimated to be living with diabetes, and that number is expected to increase to 643 million by 2030 and 783 million by 2045. The number of children and adolescents (i.e., up to 19 years old) with diabetes is also increasing annually. In 2021, it was estimated that more than 1.2 million children and adolescents under the age of 20 were living with type 1 diabetes5.

Living with and managing diabetes can be challenging and, without the right support, it may lead to serious consequences. If not managed and kept under control, diabetes increases the incidence of complications (e.g., retinopathy, nephropathy, peripheral neuropathy) which can be devastating for many individuals and affect the many spheres of their lives. In addition, uncontrolled diabetes can also lead to a heart attack or stroke; it is an ongoing battle and a person can never give up controlling diabetes if they want to avoid damage to their bodies6. To prevent diabetes complications, individuals need to be prepared to adapt and change their lifestyle. Those who have developed a deep perception of the illness, including how it works in the body, and who have a higher level of self-management ability coupled with enhanced social support systems and inner recourse, are in the best position to adjust their routine, lifestyle and live well with this complex condition7,8.

The daily choices made by individuals with diabetes have a direct effect on their health outcomes. The chronic nature of diabetes has reciprocal interactions with other dimensions of individual’ lives9. A major issue in diabetes is adjusting to and following a new regimen of self-care management with the acute and chronic aspects of the disease – this involves more than just the medical or physical management, but also the emotional perceptions of diabetes, actions and motivations to navigate life with diabetes8,9.

By exploring patients’ experiences of living with diabetes and the meaning/perception of illness, it is clear that the concepts of ‘control’ and a 'normal life’ come up frequently7. These concepts reflect their perception of the illness and their wish or need to take control and adapt their life to a ‘new’ normal life. The meaning of living with and managing diabetes can vary from person to person. Living with poorly controlled diabetes can lead to complications (e.g., kidney disease, blindness, foot ulceration and amputation) which are devastating for the individuals; this may change the way they see the disease and give meaning to it. Living with diabetes and its complications (e.g., diabetic foot ulcer, DFU) provide different meaning and perception of the illness. While it can be frustrating for some patients, others may experience introspection and existential questioning (e.g., why me God?)10.

As the condition progresses and complications begin to be noticed, one’s own ability to control the disease starts to be questioned. As a result, some individuals may display negative emotions or lower self-confidence about their self-management ability. Evidence shows that negative emotions such as anger, shame, guilt and denial can impact individuals’ ability to engage in the self-management practices (e.g., dietary habits and exercise) required to regulate diabetes11,12.

While the focus of most of the studies has been on the medical and biological aspect of diabetes management, a new approach is needed that focuses on understanding individuals’ psychosocial needs, stories and experience of living with diabetes while experiencing its complications. Understanding individuals’ experience about the impact of diabetes complications, such as DFU, and how they make meaning of diabetes after experiencing its complications provide a foundation for the design of a new approach to diabetes care; this was the main reason for developing this study. Little is known about the meanings associated with diabetes for individuals who face complications such as DFU. This study aimed to explore the meaning of living with diabetes and its particular complication (i.e., DFU) for individuals with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Research design

We used two frameworks – social constructivism informed by Charmaz13 and SI informed by Blumer14. When social constructivists align with SI, they view individuals in society as active subjects working collectively and sharing experience to reconstruct their world and realities15. When they use social constructivism as a framework, researchers need to be aware of the subjective meanings of participants’ experience toward certain objects or things. Because participants bring a variety of multiple meanings that lead researchers to examine several categories or ideas, researchers using social constructivism aim to rely as much as possible on participants’ views and experience of the situation being investigated16,17. On the other hand, researchers using this approach must recognise that their own experience and background contribute to shape their analysis and interpretation of data, as supported by Charmaz13.

In this study, researchers use SI as first described by Blumer14 because participants’ interactions occur firstly in their minds and are symbolic before they transfer them to their reality. In SI, human beings act toward things such as disease on the basis of the meaning that things represent for them. Symbolic interactionism also assumes that interaction is inherently dynamic and interpretive and therefore addresses how people create, interpret, endorse and alter meanings and actions in their life13,18. The SI framework facilitated our understanding of the meaning of diabetes and its complications for people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Study participants

This study was comprised of 30 individuals with type 1 and type 2 diabetes who developed DFU, met research criteria, and attended a wound care clinic in Southeastern Ontario, Canada, between April and August 2017. Participants were approached face-to-face and identified through purposive sampling if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1) a confirmed medical diagnosis of a DFU for at least 2 months, which ensured enough experience to reflect on the process of taking care of DFU; 2) age 18 years or older; 3) able to speak and read in English comfortably and articulate their experience of having DFU; 4) no close connection with any of the researchers prior to this study; 5) willing to engage in active self-reflection and self-disclosure about their experience of living with and managing DFU; 6) accepted to participate in this research after understanding its purpose, benefits and risks and signing the consent form. Theoretical sampling was used to guide the simultaneous processes of data collection and analysis until saturation of each emerging category and concept was achieved. Ethics approval was obtained from the Queen’s University, Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (TRAQ File #6020520). Using pseudonyms ensured confidentiality.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection and analysis occurred simultaneously and included intensive semi-structured interviews, field notes and a research journal. One-on-one interviews were audiotaped and conducted in a private room by the first researcher (IGC) until saturation, which ensured that no new properties of the research themes emerged. The duration of each interview ranged from 36 minutes and 41 seconds to 1 hour and 42 minutes. The first author, who was a PhD student and wound care nurse at the time of the study, conducted and entered interviews into N-Vivo© (Version 11.4.1) after these had been transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist.

In our study, data collection and analysis occurred in a cyclic research process. This process began with initial coding (idea-by-idea) followed by focused coding. While the initial coding process generated 529 codes, the second stage, which comprised of focused coding, helped us to collapse redundant data into 250 codes. The result of this coding process, coupled with successive levels of abstraction through comparative analysis and memo-writing, led to the inductive generation of themes that described the meaning of diabetes for individuals with type 1 and type 2 diabetes who faced a diabetes complication such as DFU.

The coding process captured spontaneous reflection about the meaning of having and managing diabetes and DFU by asking open-ended questions such as: a) Tell me about the time you found out you had diabetes? b) How have diabetes affected your life? c) What does it mean to you to have diabetes? d) What does it mean to manage diabetes on a daily basis? What does diabetic foot ulcer mean to you? e) What does it mean to manage diabetic foot ulcer on a daily basis? The interview process also included the following probing questions: a) What have you learned from having diabetes/diabetic foot ulcer? b) How do you feel about it? c) Could you tell me more about it? d) Could you give me an example?

Theoretical sampling was conducted to ensure saturation and redundancy of each theme that occurred, which was seen after the completed interviews of 30 participants. While the first author (IGC) collected and coded the data, the second author and two experts in the coding process certified confirmability and participants certified and provided feedback on the findings. The experts conducted cross-coding to evaluate accuracy and whether the data supported findings, interpretations and conclusions. To ensure the usefulness and quality of this social constructivist approach, the authors followed the five criteria suggested by Charmaz13: 1) credibility; 2) originality); 3) confirmability/validity; 4) resonance; and 5) usefulness.

Results

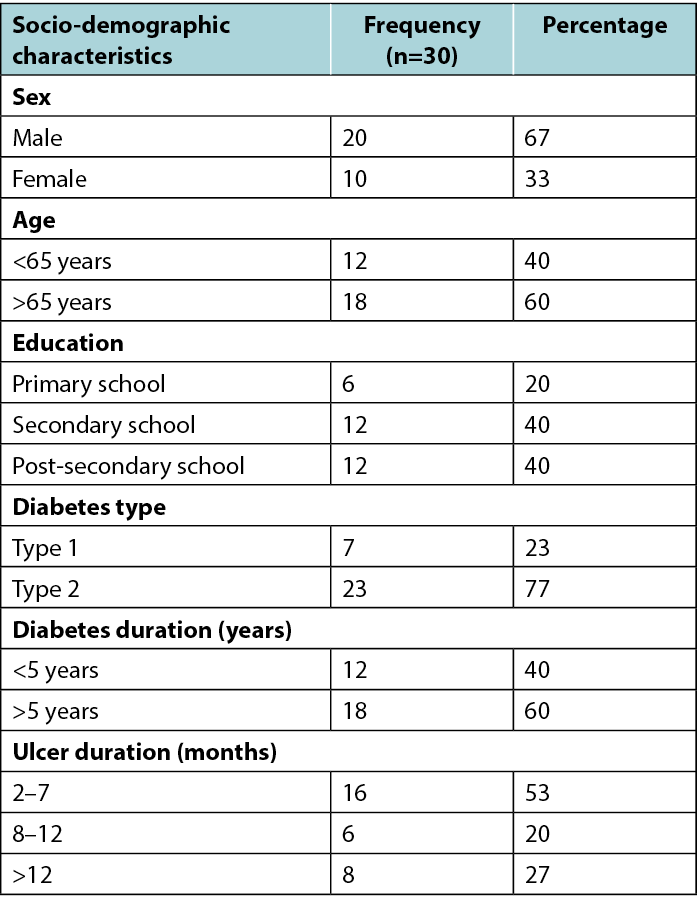

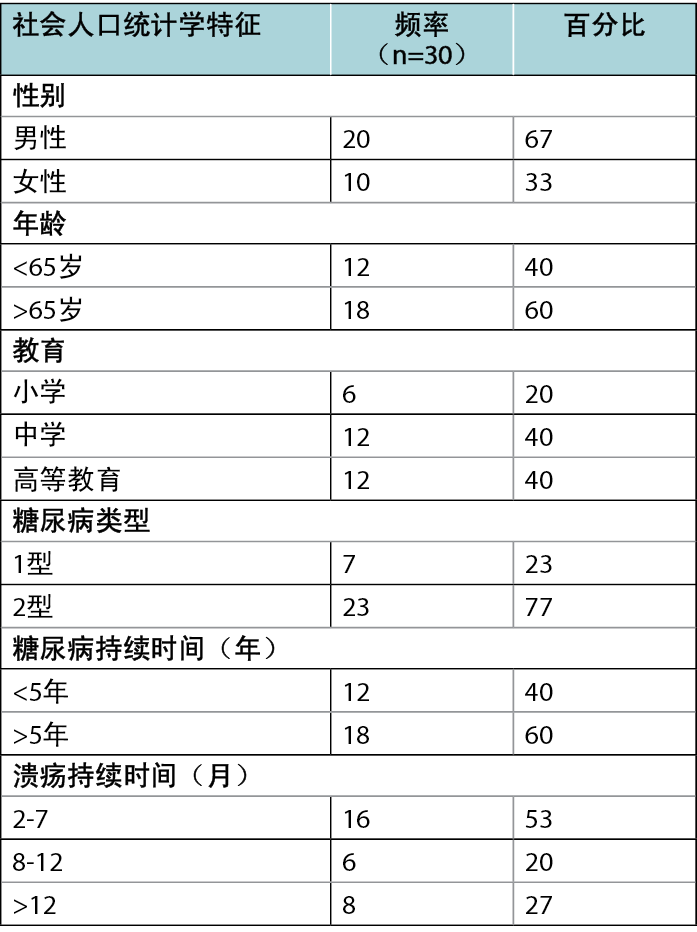

The majority of research participants (n=17) were aged 65 years or older, male (n=20), married (n=21), and living with their family (n=23). Nearly all (n=26) had completed high school and 12 had completed post-secondary education. Half the participants were retired, while seven were actively employed. Those unemployed were dependent on financial assistance from either family or government income support. Further information about participants’ demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics

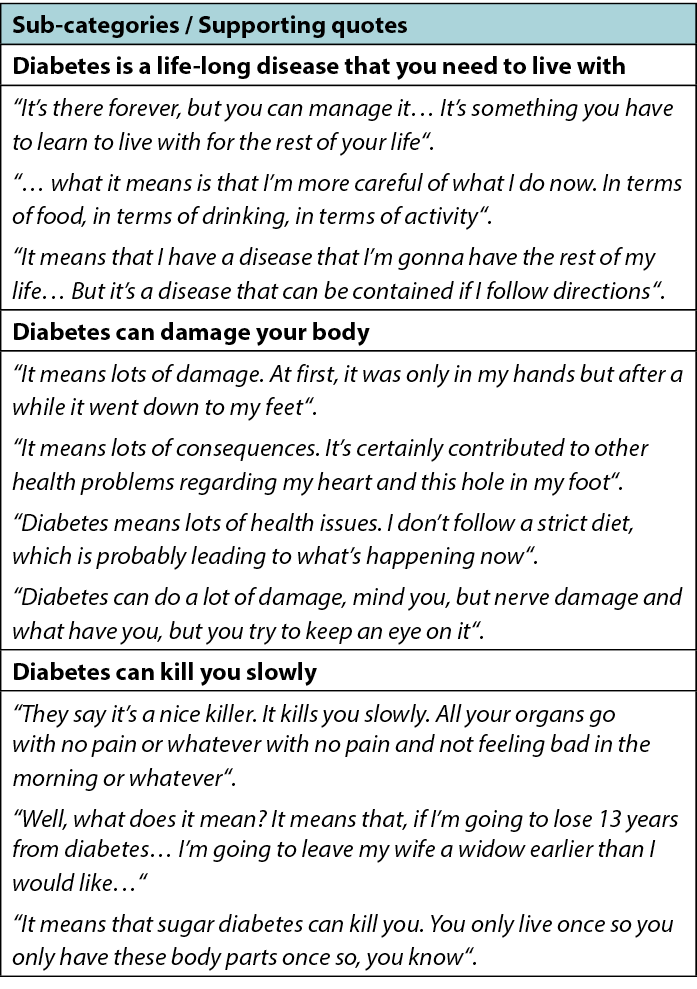

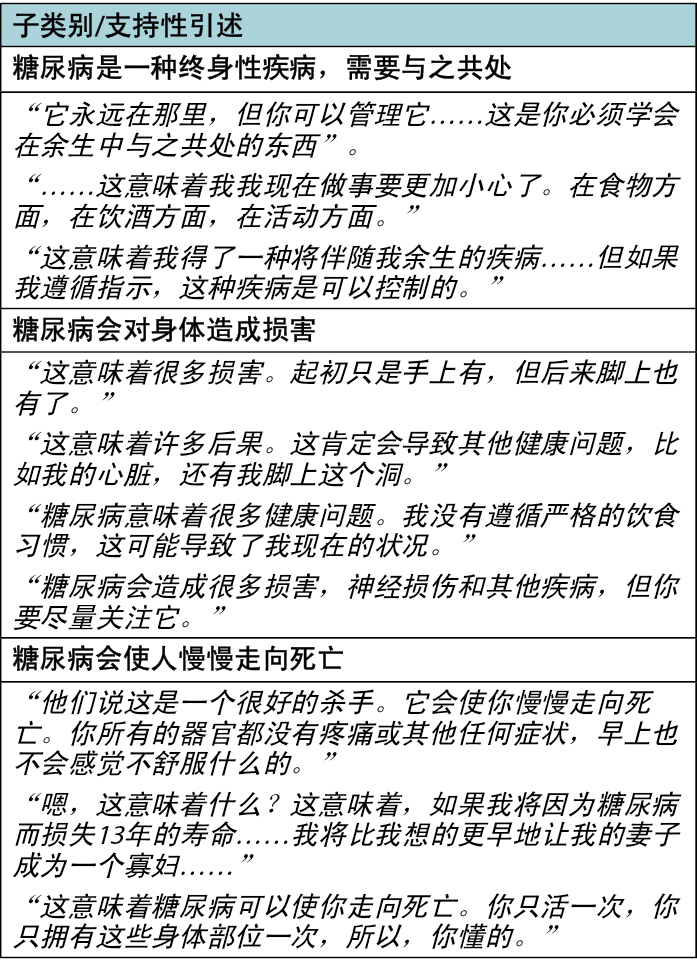

By learning about, living with, and managing diabetes for a long time, participants began to give meaning to their illness. The data implied that the three most important meanings of diabetes described by participants showed contrasting implications of the disease for their lives. These are: diabetes is a life-long disease that you need to live with; diabetes can damage your body; and diabetes can kill you slowly. Table 2 presents a summary, with its respective sub-categories and supporting quotes.

Table 2. Summary of the sub-categories and respective supporting quotes.

Diabetes is a life-long disease that you need to live with

Those participants who see diabetes as a life-long disease and part of life seemed to have accepted the need to learn how to live with it for the rest of their lives. For some participants, diabetes means that they need to be careful of everything they do such as controlling diet, being active, controlling blood sugar, and avoiding collapse, such as Grumper who pointed out:

But what it means is that I’m more careful of what I do now. In terms of food, in terms of drinking, in terms of activity. And I’m conscious of my... and times of weakness, I have to check and test my glucose and make sure that it’s not the cause. Sometimes it’s something else, I don’t know. But if it’s... if I need sugar, I need sugar. So that’s changed part of my life in the sense that I’m conscious of it all the time. I’m getting used to it, so it’s part of my life now. As long as I keep from collapsing, I’m okay.

Sometimes it is hard for individuals with diabetes to stay on track. During the interview Grumper shared that he has a weakness for sweet things or sometimes he forgets to follow a schedule of eating at certain times. The need to incorporate a rigorous balance between diet and exercise has affected his life and has caused him to constantly pay attention to his body to detect early signs and symptoms of hyper or hypoglycaemia. The challenge of managing diabetes relies on the ability of individuals to be in control of their daily living.

Furthermore, to incorporate diabetes into their daily living, some participants recognised through their own experience that it could be manageable if they adopted lifestyle changes. For example, Maverick experienced a relief of the burden of diabetes after losing weight, which led him to believe that although diabetes is an ongoing disease it also possible to be manageable:

It’s there forever, but you can manage it. Just because, when I lost a bunch of weight a couple years ago, even though I was able to go off insulin and cut my medication and all this and was virtually diabetes free, it still didn’t mean I wasn’t a diabetic. The minute you go back to the old eating habits and everything else or gain some weight, it’s still there. It’s something you have to learn to live with for the rest of your life.

Diabetes can damage your body

Many participants expressed awareness of the consequences of diabetes on their body. For James, diabetes “means lots of damage.” He has faced this damage in both his hands and feet:

It means lots of damage. At first, it was only in my hands but after a while it went down to my feet. Then a boil busted, whatever you want to call it, boil, blister, that blew up, more or less, inside my foot. It made a hole in my foot about that big.

For some participants, the consequences of diabetes were beyond a hole in their foot; it affected many parts of the body such as the kidneys, eyes and heart. For example, Butch had experienced many health issues and recognised that his uncontrolled diabetes led him to them:

Diabetes means lots of health issues. I don’t follow a strict diet, which is probably leading to what’s happening now with the rest of me. It affected my eyes and my kidneys and I am going to have to do dialysis for the rest of my life.

Diabetes can kill you slowly

Some participants compared diabetes to a death sentence. For instance, Junior admitted that diabetes means he is going to die earlier than he wished. He also disclosed that it is mostly because he did not adopt changes in his lifestyle and did not quit smoking to live well and longer with diabetes:

Well, what does it mean? It means that, if I’m going to lose thirteen years from diabetes, I’m grossly overweight as you can see, so I’m losing time from that. I smoke two packs a day, so I’m losing time from that. It means to me I’m on borrowed time right now, but we’re all going to pass. I’m okay with the reality. I’m the one that brought this on. I’m the one that started smoking, and because of my diabetes and some other factors, I can no longer exercise, so I can no longer help to maintain my weight. It’s all a contributing factor to probably I’m going to leave my wife a widow earlier than I would like, but so be it. I’ve accepted that, and she’s accepted that. We’re realistic people. Don’t like it, but it’s going to happen, so there it is.

Calling diabetes a death sentence led participants to think that diabetes makes death inevitable. Butch, for instance, shared with me that he was always drinking alcohol and partying because he wanted to enjoy his life before dying from diabetes. However, he is now suffering from many consequences of diabetes and blames his lack of understanding and denial to take control of it from the beginning. On the other hand, Junior considers himself a loser to diabetes because he did not adopt a new lifestyle and continued smoking. His foot damage has also prevented him from being active and therefore losing weight to control diabetes. He seems to view his situation as a lost cause and hence has accepted the fact that he is going to die earlier than he wished.

Discussion

In this study, participants developed their own meaning of diabetes, which was influenced by personal beliefs, family history, and their day-to-day experience of living with diabetes and its complications. The study’s findings demonstrated that variations existed regarding the extent to which participants moved along the continuum of acceptance, as well as the extent to which they actively engaged in the process of learning about, making meaning of, and taking action toward engagement in managing diabetes. For instance, the silent nature of diabetes caught many participants off guard, as they were mostly unaware of the signs and symptoms of diabetes, and of the possibility that they might have the condition. Once diagnosed, learning to live with and managing diabetes occurred progressively, but also represented a challenge for most participants.

Our study’s findings uncovered that the meaning of living with diabetes may be different for individuals facing diabetes complications. Facing the poor outcome of diabetes led participants to experience damage to their body (e.g., foot deformity, calluses, wounds, amputation, eye and kidney problems), and see diabetes as a threat to their mental health and quality of life. These participants connected the meaning of diabetes to the effects of the disease on their body and mind. For example, they saw diabetes as a death sentence or a condition that “kills you slowly”. These findings align with previous qualitative and quantitative studies that explored the meaning of diabetes among individuals who faced the burden of diabetes. These studies described that the meaning of diabetes was strongly associated with both physical and mental components of quality of life19–21.

While “watching what you eat” became a crucial component in the management of diabetes, “taking care of your foot” was an essential component in the prevention of one of the most devastating consequences of unregulated diabetes. In our study, knowing how to choose the right diet and the right shoes became fundamental for participants to feel in control of the disease. Authors of a previous study that explored individuals’ experience of living with and implementing diabetes self-management practices stated that the concept of control prevailed and permeated all categories of the study. An example is from participants’ struggle to adapt to a daily management regime through their ability to achieve a balance between living with a progressive chronic condition and adapting to a so-called normal life7.

Authors of a previous study reported that even for those individuals aware that they need to “watch what they eat”, their major apprehension was how to get the diet right22. Changing lifestyle presents a challenge for older adults to incorporate in their everyday life and makes the management of diabetes a difficult task to follow, but they are aware of the need to deal with it the best way that they can and know how6. In our study, some participants self-labelled themselves “a bad diabetic” because they were not able to sustain the lifestyle change required to regulate diabetes. For example, they would not follow a consistent diet and incorporate physical exercise into their daily routine. Similarly, participants of a previous study also had difficulty in maintaining a consistent lifestyle. Inconsistency in maintaining a recommended regime reflects the lack of or limited knowledge about the disease, and the challenge to adjust their lives to the complexities of required daily tasks7. In fact, in our study most participants did not have access to diabetes education and none of them were provided with education about self-care of their feet.

Both our study and previous studies demonstrated the consequences of not sustaining a recommended regimen or lifestyle both in terms of clinical (e.g., hypo or hyperglycaemia), physical (e.g., DFU, blindness) and psychological outcomes (e.g., guilt, anxiety and frustration) as some participants in this study reflected7,23. One may ask, if Maverick was conscious about the benefits of his engagement in self-management of diabetes, why he was not able to sustain it? The simple answer is that the management of a long-term condition such as diabetes is also a “lifelong battle” that requires considerable mental determination and commitment of self to adjust to a new psychosocial lifestyle24,25. In fact, the permanent changes required to adopt and adapt to a new lifestyle and regimen that comes with the demands of diabetes must be understood from psychological, spiritual and behavioural aspects of the disease12. Participants in our study perceived diabetes as a disease that they will have to deal with for the rest of their lives; they understood that lifestyle changes may not be easy to adopt, but are important to make if they want to be able to live well with diabetes and prevent serious consequences. Similarly, participants in a previous qualitative study developed in Indonesia also shared that diabetes is a disease that has no cure yet, caused lifelong stress and worry, and led to many changes in their bodies26.

After facing the consequences of diabetes such as DFU or amputation, participants in our study felt guilty, regretted not taking care of diabetes from the beginning, and somberly accepted their condition. Perhaps individuals who had spent a lifetime trying to manage diabetes to the best of their ability but ended up with complications might believe that they had done everything possible to keep their lives going with diabetes. Such a situation seemed to have led seniors with diabetes to relax self-management because, believing it beyond their control, they started to normalise their condition, an outcome similar to findings in a previous study about lay perception of diabetes in Indonesia26. In alignment with our findings, authors of previous studies in Indonesia and the United States reported that participants believed that diabetes was beyond their control and did not seem motivated to fight this battle; therefore, they accepted the limitations and challenges produced by the disease10.

In fact, motivation is an essential component to maintain for the person engaged in a life-long self-management task, but what motivates one person may be different from what motivates another, especially for those who are ageing with multiple chronic conditions and experiencing diabetes complications in addition to these27. On the other hand, the long-term risk of developing diabetes complications does not seem to be an usual motivation for individuals with diabetes to change lifestyle; instead, they are most often motivated by perceived short-term improvements28. For example, if the person has seen relatives or close friends with complications from diabetes, they may think it is a waste of time to manage and deal with it5 or they may become aware and engage in lifestyle changes to avoid ending up in a similar situation. Therefore, further research is needed to explore the motivation factor as a component for lifestyle change in people with diabetes.

Conclusion and implications

The complexity of care and the consequences of unregulated diabetes influenced participants’ perception, meaning, motivation, actions and reactions to diabetes. The challenge to take in the necessary health information and make lifestyle changes to prevent disease complications often interferes with patients’ perception of what it means to live with diabetes. To facilitate the uptake of individuals’ experience and perception or meaning of diabetes into clinical practice, it is essential that healthcare providers (HCPs) communicate with patients to understand the battle they are facing to live with and fight diabetes on a daily basis.

Understanding that each person with diabetes is unique and may be affected by the disease in different ways (physically and/or emotionally) helps HCPs to better understand how to address each individual’s unique and complex needs. It is crucial to expand research and care practice to focus on more than just the physical aspect of diabetes as a disease. Rather, HCPs would be better equipped to support individuals with diabetes when they are trained to focus on successful and cooperative management of the illness that encompasses the emotional, relational and psychosocial aspects of this complex condition.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs Deborah Tregunno, Elizabeth VanDenKerkhof and Dana Edge for their contributions in the thesis preparation that generated this paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Financial support was provided by the Canadian Frailty Network to complete the many steps of this study.

Author contributions

IGC is the principal investigator and was responsible for the conception of the project, funding acquisition, data collection and analysis, and drafted the first and final versions of this manuscript. PCP contributed with the design of research methodology, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the final version to be published.

糖尿病足溃疡患者眼中糖尿病的含义:一项基于社会建构主义和符号互动论框架的定性研究

Idevania G Costa and Pilar Camargo-Plazas

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.42.4.41-47

摘要

目的 本定性调查探讨了患有糖尿病足溃疡(DFU)的1型和2型糖尿病患者眼中的糖尿病的含义。

方法 本定性研究采用社会建构主义和符号互动论(SI)框架来指导研究设计。本研究的参与者是30名患有1型或2型糖尿病以及DFU的成人患者,他们符合研究标准并于2017年4月至8月期间在加拿大安大略省的一家伤口护理诊所就诊。

结果 定性内容分析揭示了代表核心类别(糖尿病的含义)的三个主要子类别以及参与者对患有糖尿病及其特殊并发症的看法Å\Å\1)糖尿病是一种终身性疾病,需要与之共处,2)糖尿病会对身体造成损害,3)糖尿病会使人慢慢走向死亡。

结论 自我护理的复杂性和不受节制的糖尿病的后果影响了参与者对糖尿病的看法、意义、动机、行动和反应。每个糖尿病患者都是独一无二的,可能以不同的方式经历或受到疾病的影响,了解这一点有助于医疗服务提供者(HCP)更好地理解如何解决每个人独特而复杂的需求。

引言

糖尿病是一种严重的代谢性疾病,在全球范围内患病率不断上升。它是由缺乏或无法产生胰岛素来充分发挥其对血糖控制的作用而引起的1。在加拿大,预防这种疾病及其适当的管理被认为是医疗优先事项2,特别是因为在加拿大人中每天大约诊断出549例新发糖尿病病例3,其中90%的诊断病例为2型糖尿病,9%为1型糖尿病,其余1%为其他类型糖尿病4。

由于肥胖水平上升、不健康饮食和久坐不动的生活方式等因素,2型糖尿病的发病率尤其上升。然而,1型糖尿病的发病率也在増加。例如,在2000年,据估计全球约有1.51亿成年人患有糖尿病。有趣的是,2010年,国际糖尿病联合会(IDF)的成员预测,到2025年将有4.38亿人患有糖尿病5。然而这一数字实际上更大;2021年,估计有超过5亿(5.37亿)人患有糖尿病,预计到2030年,这一数字将増加到6.43亿,到2045年将増加到7.83亿。儿童和青少年(即不超过19岁)糖尿病患者的数量也在逐年増加。2021年,据估计有超过120万20岁以下的儿童和青少年患有1型糖尿病5。

患有糖尿病并对其进行管理可能具有挑战性,如果没有正确的支持,可能会导致严重的后果。如果不加以管理和控制,糖尿病会増加并发症(例如视网膜病变、肾病、周围神经病变)的发生率,这对许多人来说可能是毁灭性的,并影响他们生活的许多方面。此外,糖尿病如果不加以控制也会导致心脏病发作或卒中;这是一场持续的战斗,如果想避免对身体的损害,就永远不能放弃控制糖尿病6。为了预防糖尿病并发症,个人需要做好适应和改变生活方式的准备。对疾病有深刻认识(包括它在体内的运作方式)的人,以及具有高水平的自我管理能力及増强的社会支持系统和内心强大的人,能够很好地调整他们的日常生活方式,并在这种复杂的情况下生活得很好7,8。

糖尿病患者的日常选择直接影响他们的健康结果。糖尿病的慢性性质与个人生活的其他方面相互影响9。糖尿病的一个主要问题是根据疾病的急性和慢性方面调整和遵循新的自我护理管理方案Å\Å\这不仅涉及医疗或身体管理,还涉及糖尿病的情绪认知、糖尿病患者的行动和生活动力8,9。

通过探索糖尿病患者的生活经历和疾病的含义/感知,很明显“控制”和“正常生活”的概念经常出现7。这些概念反映了他们对疾病的看法,以及他们希望或需要控制自己的生活并使其适应“新的”正常生活。患有糖尿病和管理糖尿病的含义可能因人而异。糖尿病控制不佳可能导致并发症(例如肾病、失明、足部溃疡和截肢),这对个人来说是毁灭性的;这可能会改变他们看待疾病并赋予其含义的方式。与糖尿病及其并发症(如糖尿病足溃疡、DFU)共处带来了不同的疾病含义和感知。虽然一些患者可能会感到沮丧,但另一些患者可能会进行内省和存在主义质疑(例如,天哪为什么是

我?)10。

随着病情的发展和并发症开始被注意到,一个人对疾病的控制能力开始受到质疑。因此,一些人可能对其自我管理能力表现出负面情绪或对自己的自我管理能力缺乏自信。证据表明,愤怒、羞耻、内疚和否认等负面情绪会影响个人参与调节糖尿病所需的自我管理实践(如饮食习惯和锻炼)的能力11,12。

虽然大多数研究的重点都集中在糖尿病管理的医学和生物学方面,但仍需一种新的方法,重点了解个人的社会心理需求、糖尿病患者在经历并发症时的生活故事和经验。了解个人对糖尿病并发症(如DFU)影响的经验,以及他们在经历并发症后如何理解糖尿病的含义,为设计糖尿病护理的新方法奠定了基础;这是开展这项研究的主要原因。对于面临DFU等并发症的个体而言,并不太清楚糖尿病意味着什么。本研究旨在探索对1型和2型糖尿病患者而言患有糖尿病及其特定并发症(即DFU)意味着什么。

方法

研究设计

我们使用了两个框架Å\Å\Charmaz13的社会建构主义和Blumer14的SI。当社会建构主义者与SI相一致时,他们将社会中的个人视为积极的主体,共同工作并分享经验,以重建他们的世界和现实15。当他们使用社会建构主义作为框架时,研究人员需要意识到参与者对某些对象或事物的经验的主观含义。参与者带来了多种多样的含义,导致研究人员检查多个类别或想法,使用社会建构主义的研究人员旨在尽可能多地依赖参与者对所调查情况的看法和经验16,17。另一方面,使用这种方法的研究人员必须认识到,他们自己的经验和背景有助于塑造他们对数据的分析和解释,这一点得到了Charmaz的支持13。

在这项研究中,研究人员使用了Blumer14首先提出的SI,因为参与者的互动首先发生在他们的脑海中,在他们将其转移到现实之前是象征性的。在SI中,人类基于疾病等事情对其而言的含义采取行动。符号互动论还假设互动本质上是动态的和解释性的,因此涉及人们如何在生活中创造、解释、认可和改变含义和行动13,18。SI框架有助于我们理解糖尿病及其并发症对1型和2型糖尿病患者而言的含义。

研究参与者

本研究包括2017年4月至8月在加拿大安大略省东南部的一家伤口护理诊所就诊的30名出现DFU、符合研究标准的1型和2型糖尿病患者。如果参与者符合以下纳入标准,则进行面对面接洽,并通过立意抽样来确定:1)确诊DFU至少2个月,确保有足够的经验来反思DFU的护理过程;2)年满18岁;3)能够流利地用英语说话和阅读,并清楚地表达他们的DFU经历;4)在本研究之前,与任何研究人员均无密切联系;5)愿意主动自我反思和自我透露他们患DFU和管理DFU的经验;6)在了解研究目的、获益和风险后同意参加本研究并签署知情同意书。理论抽样用于指导数据收集和分析的同步过程,直到每个新出现的类别和概念达到饱和。研究获得了女王大学健康科学和附属教学医院研究伦理委员会的伦理批准(TRAQ文件编号6020520)。使用化名确保了机密性。

数据收集和分析

数据收集和分析同时进行,包括密集的半结构式访谈、现场笔记和一份研究日志。由第一研究者(IGC)在私人房间内进行一对一访谈并录音,直至饱和,这确保了研究主题没有新的属性出现。每次访谈的持续时间为36分41秒至1小时42分钟不等。第一作者在研究期间是一名博士生和伤口护理护士,她进行了采访,并在专业转录员逐字转录访谈内容后,将其录入N-Vivo˝(版本11.4.1)。

在我们的研究中,数据收集和分析是一个循环的研究过程。这个过程从初始编码 (逐个想法)开始,然后是集中编码。虽然初始编码过程生成了529个代码,但第二阶段的集中编码帮助我们将冗余数据分解为250个代码。这个编码过程的结果,加上通过比较分析和备忘录编写得到的连续抽象层次,归纳生成了主题,这些主题描述了糖尿病对面临糖尿病并发症(如DFU)的1型和2型糖尿病患者而言的含义。

编码过程通过提出以下开放式问题来捕捉对患有和管理糖尿病和DFU的含义的自发反思,例如:a)请告诉我您发现您患有糖尿病的时间?b)糖尿病对您的生活有何影响?c)患有糖尿病对您来说意味着什么?d)日常管理糖尿病意味着什么?糖尿病足溃疡对您意味着什么?e)日常管理糖尿病足溃疡意味着什么?访谈过程还包括以下探索性问题:a)您从患有糖尿病/糖尿病足溃疡中学到了什么?b)您的感受如何?c)您能告诉我关于它的更多信息吗?d)您能给我举个例子吗?

进行了理论抽样,以确保出现的每个主题的饱和以及冗余,这是在30名参与者完成访谈后进行的。在第一作者(IGC)收集并编码数据的同事,但第二作者和编码过程中的两名专家证明了可验性,参与者证明并提供了关于结果的反馈。专家们进行了交叉编码,以评价准确性以及数据是否支持结果、解释和结论。为了确保这种社会建构主义方法的有用性和质量,作者遵循了Charmaz13建议的五个标准:1)可信度;2)独创性;3)可验性/效度;4)共鸣;5)有用性。

结果

大多数研究参与者(n=17)的年龄在65岁或以上,男性(n=20),已婚(n=21),与家人一起生活(n=23)。几乎所有参与者(n=26)都完成了高中教育,12人完成了高等教育。一半的参与者已退休,而7人仍在职。失业者依赖家庭或政府收入补助提供的经济援助。有关参与者人口统计特征的更多信息,请参见表1。

表1.社会人口统计学特征

通过学习、与糖尿病共处和长期管理糖尿病,参与者开始给他们的疾病赋予含义。数据表明,参与者描述的糖尿病的三个最重要的含义显示了该疾病对他们生活的不同影响。它们是:糖尿病是一种终身性疾病,需要与之共处;糖尿病会对身体造成损害;糖尿病会使人慢慢走向死亡。表2列出了总结及其各自的子类别和支持性引述。

表2.子类别总结及其支持性引述。

糖尿病是一种终身性疾病,需要与之共处

将糖尿病视为终身性疾病和生活一部分的参与者似乎接受了需要学习如何在余生与之共处。对于一些参与者来说,糖尿病意味着他们做任何事都需要小心谨慎,例如控制饮食、多活动、控制血糖、避免虚脱,比如Grumper指出:

但这意味着我对现在所做的事情要更加小心谨慎。在食物方面,在饮酒方面,在活动方面。我意识到自己的ÅcÅc和虚弱的时候,我必须检查和测试我的葡萄糖,确保这不是原因。有时是别的原因,我不知道。但如果ÅcÅc如果我需要糖,我就需要糖。所以这就是我生活有所改变的部分,我一直都有意识到这一点。我已经习惯了,所以这就是我生活的一部分。只要我不虚脱,我就没事。

有时,糖尿病患者很难坚持下去。在采访中,Grumper分享了他爱吃甜食,有时他也会忘记在某些时间遵循时间表进食。需要在饮食和运动之间保持严格的平衡影响了他的生活,并使他不断关注自己的身体,以发现高血糖或低血糖的早期体征和症状。管理糖尿病的挑战取决于个人控制其日常生活的能力。

此外,为了将糖尿病纳入日常生活中,一些参与者通过自己的经验认识到,如果他们改变生活方式,糖尿病是可以控制的。例如,Maverick在减肥后减轻了糖尿病的负担,这使他相信,尽管糖尿病是一种持续性疾病,但有可能是可控的:

它永远存在,但你可以管理它。因为,当我几年前减重很多后,即使我能够停用胰岛素并减少用药,而且几乎没有糖尿病症状,但这仍然并不意味着我不是糖尿病患者。一旦回到旧的饮食习惯和其他习惯或体重増加了一些,它仍然存在。这是你必须学会在余生中与之共处的事情。

糖尿病会对身体造成损害

许多参与者表示意识到了糖尿病对他们身体的影响。对James来说,糖尿病“意味着很多损害”。他的手和脚都受到了这种损害:

这意味着很多损害。起初只是手上有,但后来脚上也有了。然后,一个疖破了,不管你想怎么称呼它,疖,水疱,反正它在我的脚里炸开了。它在我的脚上开了一个洞,大概这么大。

对于一些参与者来说,糖尿病的后果不仅仅是他们脚上的一个洞;它影响了身体的许多部位,如肾脏、眼睛和心脏。例如,Butch经历过许多健康问题,并认识是由于未控制糖尿病而导致了这些问题:

糖尿病意味着很多健康问题。我没有遵循严格的饮食习惯,这可能导致了我现在的状况。它影响了我的眼睛和肾脏,我今后的日子里都将不得不做透析。

糖尿病会使人慢慢走向死亡

一些参与者将糖尿病比作死刑。例如,Junior承认,糖尿病意味着死亡会比他希望的来得更早。他还透露,这主要是因为他没有改变生活方式,没有戒烟以在患糖尿病的同时活得更好更久:

嗯,这意味着什么?这意味着,我要因为糖尿病而失去13年的寿命,正如你所看到的,我严重超重,所以我会因此失去时间。我每天抽两包烟,所以我也因此失去了时间。这对我来说意味着我现在的时间是借来的,但我们都会过去的。我接受现实。是我自己造成这种情况的。是我自己开始吸烟的,而且因为我的糖尿病和其他一些因素,我不能再运动了,所以我不能再帮助维持我的体重。这都可能是我让我妻子比我想象中更早成为寡妇的一个因素,但就这样吧。我接受了,她也接受了。我们是现实的人。虽然不喜欢,但它会发生的,所以就是这样。

将糖尿病称为死刑使参与者认为糖尿病使死亡不可避免。以Butch为例,他告诉我,他总是喝酒、参加聚会,因为他想在死于糖尿病之前享受生活。然而,他现在正承受糖尿病的诸多后果,并归咎于自己缺乏理解并拒绝从一开始就对其采取控制。另一方面,Junior认为自己是糖尿病的失败者,因为他没有采取新的生活方式,而是继续吸烟。他的足部损伤也使他无法活动,因此无法减肥来控制糖尿病。他似乎认为他的处境是注定要失败的,因此接受了他会比他希望的更早死亡的事实。

讨论

在这项研究中,参与者形成了自己对糖尿病的理解,这受到个人信仰、家族史和他们与糖尿病及其并发症共处的日常经验的影响。研究结果表明,参与者在接受程度以及他们积极参与学习、理解和采取行动管理糖尿病的过程的程度方面存在差异。例如,糖尿病的隐匿性质使许多参与者措手不及,因为他们大多不知道糖尿病的体征和症状,也不知道自己可能会患有这种疾病。一旦确诊,就要逐渐学习与糖尿病共处和管理糖尿病,但这对大多数参与者来说也是一个挑战。

我们的研究结果表明,对于面临糖尿病并发症的个体而言,与糖尿病共处的含义可能不同。面对糖尿病的不良后果,参与者的身体受到了损害(例如足部畸形、胼胝、伤口、截肢、眼睛和肾脏问题),并将糖尿病视为对其心理健康和生活质量的威胁。这些参与者将糖尿病的含义与疾病对他们身心的影响联系起来。例如,他们将糖尿病视为死刑或“使人慢慢走向死亡”的疾病。这些发现与之前的定性和定量研究一致,这些研究探索了糖尿病在面临糖尿病负担的个体中的含义。这些研究表明,糖尿病的含义与生活质量的身体和心理因素密切相关19-21。

虽然“注意饮食”成为糖尿病管理的关键组成部分,但“照顾好脚部”是预防不受控制的糖尿病最具破坏性后果之一的必要组成部分。在我们的研究中,知道如何选择正确的饮食和合适的鞋子成为参与者感到疾病得到控制的基础。之前一项研究探讨了个体与糖尿病共处和实施糖尿病自我管理实践的经验,作者指出,控制的概念普遍存在并渗透到研究的所有类别中。一个例子是,参与者通过他们与进行性慢性疾病共处和适应所谓的正常生活之间达到平衡的能力来努力适应日常管理机制7。

之前一项研究的作者报告说,即使对于那些意识到自己需要“注意饮食”的人,他们的主要担心也是如何正确饮食22。改变生活方式对老年人融入日常生活提出了挑战,并使糖尿病管理成为一项艰巨的任务,但他们意识到需要以他们能做到的最好的方式来处理,并且知道如何处理6。在我们的研究中,一些参与者将自己标记为“差劲的糖尿病患者”,因为他们无法维持调节糖尿病所需的生活方式改变。例如,他们不会遵循一致的饮食习惯,也不会将体育锻炼纳入他们的日常生活中。同样,之前一项研究的参与者也难以保持一致的生活方式。在维持建议的养生计划方面的不一致反映了对这种疾病缺乏了解或了解有限,以及难以使他们的生活适应所需日常任务的复杂性7。事实上,在我们的研究中,大多数参与者无法获得糖尿病相关的教育,也没有人向他们提供关于足部自我护理的教育。

我们的研究和以前的研究都证明了在临床(例如低血糖或高血糖)、身体(例如DFU、失明)和心理结果(例如内疚、焦虑和沮丧)方面不维持推荐的养生计划或生活方式的后果,本研究的一些参与者也反映出这一结果7,23。有人可能会问,如果Maverick意识到他参与糖尿病自我管理的益处,为什么他不能坚持下去?简单的答案是,糖尿病等长期疾病的管理也是一场“终生战斗”,需要相当大的精神决心和自我的承诺来适应新的社会心理生活方式24,25。事实上,这必须从疾病的心理、精神和行为层面来理解采用和适应糖尿病带来的新生活方式和养生计划所需的永久性变化12。我们研究的参与者认为糖尿病是一种他们在余生中不得不面对疾病;他们明白生活方式可能不容易改变,但如果他们想在患有糖尿病的情况下生活地很好并预防严重后果,那么改变生活方式很重要。同样,之前在印度尼西亚开展的一项定性研究的参与者也表示,糖尿病是一种目前尚不能被治愈的疾病,会引起终生的压力和担忧,并导致他们身体发生许多变化26。

在面临DFU或截肢等糖尿病的后果后,我们研究的参与者感到内疚,后悔没有从一开始好好注意糖尿病,并严肃接受自己的病情。也许那些花了一生的时间试图尽最大能力管理糖尿病但最终出现并发症的人可能会认为,他们已经尽了一切努力来维持自己的糖尿病生活。这种情况似乎导致患有糖尿病的老年人放松自我管理,因为他们认为自我管理超出了他们的控制范围,因此他们开始使自己的病情正常化,这一结果与之前一项关于印度尼西亚非专业人员对糖尿病认知的研究结果相似26。与我们的研究结果一致,之前在印度尼西亚和美国进行的研究的作者报告称,参与者认为糖尿病超出了他们的控制范围,似乎没有动力与与之斗争;因此,他们接受了疾病带来的限制和挑战10。

事实上,对于进行终生自我管理任务的人来说,动机是维持自我管理的重要组成部分,但一个人的动机可能与另一个人的动机不同,尤其是对于除这些因素外还患有多种慢性疾病和发生糖尿病并发症的老年人27。另一方面,发生糖尿病并发症的长期风险似乎不是糖尿病患者改变生活方式的常见动机;相反,他们的动机往往是短期内的改善28。例如,如果一个人看过患有糖尿病并发症的亲属或密友,他们可能会认为管理和处理糖尿病很浪费时间5,或者他们也可能会意识到并改变生活方式,以避免出现类似情况。因此,需要进一步的研究来探索作为糖尿病患者生活方式改变组成部分的动机因素。

结论和意义

护理的复杂性和不受管制的糖尿病的后果影响了参与者对糖尿病的感知、理解、动机、行动和反应。吸收必要的健康信息并改变生活方式以预防疾病并发症的这一挑战往往会干扰患者对糖尿病生活的理解。为了促进将个人对糖尿病的经验和看法或理解引入临床实践,医疗服务提供者(HCP)需要与患者沟通,了解他们每天与糖尿病共处和对抗所面临的战斗。

每个糖尿病患者都是独一无二的,可能以不同的方式(身体和/或情绪)受到疾病的影响,了解这一点有助于HCP更好地理解如何满足每个人独特而复杂的需求。扩大研究和护理实践至关重要,要不只是关注糖尿病作为一种疾病对身体方面的影响。相反,当糖尿病患者接受培训以专注于成功和合作地管理疾病(包括这种复杂疾病的情绪、关系和社会心理方面)时,HCP将更好地为他们提供支持。

致谢

感谢Deborah Tregunno博士、Elizabeth VanDenKerkhof博士和Dana Edge博士为撰写本文所做的贡献。

利益冲突声明

作者声明无利益冲突。

资助

Canadian Frailty Network为完成本研究的许多步骤提供了资金支持。

作者贡献

IGC是主要研究者,负责项目的构思、资金获取、数据收集和分析,并起草了本稿件的第一版和最终版。PCP参与了研究方法的设计,并针对重要的知识内容对稿件进行了批判性修订。所有作者均审阅并批准了要发布的最终版本。

Author(s)

Idevania G Costa*

RN, NSWOC, PhD

Assistant Professor in the School of Nursing and Adjunct Professor in the Faculty of Health Science,

Lakehead University, 955 Oliver Rd, P7B 5E1 Thunder Bay, ON, Canada

Email igcosta@lakeheadu.ca

Pilar Camargo-Plazas

RN, PhD

Associate Professor, School of Nursing, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

* Corresponding author

References

- Petersmann A, Müller-Wieland D, Müller UA, Landgraf R, Nauck M, Freckmann G, et al. Definition, classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2019;27(S 01):S1–S7.

- Bilandzic A, Rosella L. The cost of diabetes in Canada over 10 years: applying attributable health care costs to a diabetes incidence prediction model. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2017;37(2):49–53.

- LeBlanc AG, Gao YJ, McRae L, Pelletier C. At-a-glance: twenty years of diabetes surveillance using the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2019;39(11):306–9.

- Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Diabetes Canada 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42(Suppl 1):S1-S325.

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes atlas (9th ed.); 2019. Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org/upload/resources/material/20200302_133351_IDFATLAS9e-final-web.pdf2019.

- Stiffler D, Cullen D, Luna G. Diabetes barriers and self-care management: the patient perspective. Clin Nurs Res 2014;23(6):601–26.

- Handley J, Pullon S, Gifford H. Living with type 2 diabetes: ‘Putting the person in the pilots’ seat’. Aust J Adv Nurs 2010;27(3):12–9.

- Costa IG, Tregunno D, Camargo-Plazas P. Patients’ journey toward engagement in self-management of diabetic foot ulcer in adults with types 1 and 2 diabetes: a constructivist grounded theory study. Can J Diabetes 2021;45(2):108–13.

- Houston-Barrett RA, Wilson CM. Couple’s relationship with diabetes: means and meanings for management success. J Marital Fam Ther 2014;40(1):92.

- George SR, Thomas SP. Lived experience of diabetes among older, rural people. J Adv Nurs 2010;66(5):1092–100.

- Hart PL, Grindel CG. Illness representations, emotional distress, coping strategies, and coping efficacy as predictors of patient outcomes in type 2 diabetes. J Nurs Healthcare Chronic Illness 2010;2(3):225–40.

- Sylvia E, Domian E. How adults with diabetes struggle to find the meaning of their disease. Clin Scholars Rev 2012;5(1):31–8.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Washington DC: Sage; 2014.

- Blumer H. Symbolic interactionism: perspective and method Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1969.

- Lincoln YS, Lynham SA, Guba EG. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011. p. 97–128.

- Creswel JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Washington DC: Sage; 2013.

- Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc.; 2018.

- Oliver C. The relationship between symbolic interactionism and interpretive description. Qual Health Res 2012;22(3):409–15.

- Arifin B, Probandari A, Purba AKR, Perwitasari DA, Schuiling-Veninga CCM, Atthobari J, et al. ‘Diabetes is a gift from God’: a qualitative study coping with diabetes distress by Indonesian outpatients. Qual Life Res 2020;29(1):109–25.

- McFarland KF, Rhoades DR, Campbell J, Finch WH. Meaning of illness and health outcomes in type 1 diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2001 Jul-Aug;7(4):250-5. doi: 10.4158/EP.7.4.250. PMID: 11497475.

- Pera PI. Living with diabetes: quality of care and quality of life. Patient Prefer Adherence 2011;5:65–72.

- Minet LKR, Lønvig E-M, Henriksen JE, Wagner L. The experience of living with diabetes following a self-management program based on motivational interviewing. Qual Health Res 2011;21(8):1115–26.

- Youngson A, Cole F, Wilby H, Cox D. The lived experience of diabetes: conceptualisation using a metaphor. Br J Occ Ther 2015;78(1):24–32.

- Unantenne N, Warren N, Canaway R, Manderson L. The strength to cope: spirituality and faith in chronic disease. J Relig Health 2013;52(4):1147–61.

- Suparee N, McGee P, Khan S, Pinyopasakul W. Life-long battle: Perceptions of type 2 diabetes in Thailand. Chronic Illn. 2015 Mar;11(1):56-68. doi: 10.1177/1742395314526761. Epub 2014 Mar 6. PMID: 24602925.

- Widayanti AW, Heydon S, Norris P, Green JA. Lay perceptions and illness experiences of people with type 2 diabetes in Indonesia: a qualitative study. Health Psychol Behav Med 2020;8(1):1–15.

- Costa IG, Tregunno D, Camargo-Plazas P. I cannot afford off-loading boots: perceptions of socioeconomic factors influencing engagement in self-management of diabetic foot ulcer. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2020;43(4):322–37.

- Rodriguez KM. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors affecting patient engagement in diabetes self-management: perspectives of a certified diabetes educator. Clin Ther 2013;35(2):170–8.