Volume 43 Number 2

Sternal wound management in pediatric cardiac surgical patients: implementation of wound care pathways incorporating principles of wound bed preparation paradigm and early-advanced therapy

Neerod Kumar, Muhammad Shafique, Raisy Thomas, Salvacion Pangilinan Cruz, Gulnaz Tariq, Laszlo Kiraly

Keywords cardiac, Wound care, Infection, surgery, management, pediatric, interprofessional, sternum

For referencing Kumar N et al. Sternal wound management in pediatric cardiac surgical patients: implementation of wound care pathways incorporating principles of wound bed preparation paradigm and early-advanced therapy. WCET® Journal 2023;43(2): 13-23

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.2.13-23

Submitted 6 June 2022

Accepted 9 August 2022

Abstract

Objective The information on sternal wound management in children after cardiac surgery is limited. The authors formulated a pediatric sternal wound care schematic incorporating concepts of interprofessional wound care and the wound bed preparation paradigm including negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) and surgical techniques to expedite and streamline wound care in children.

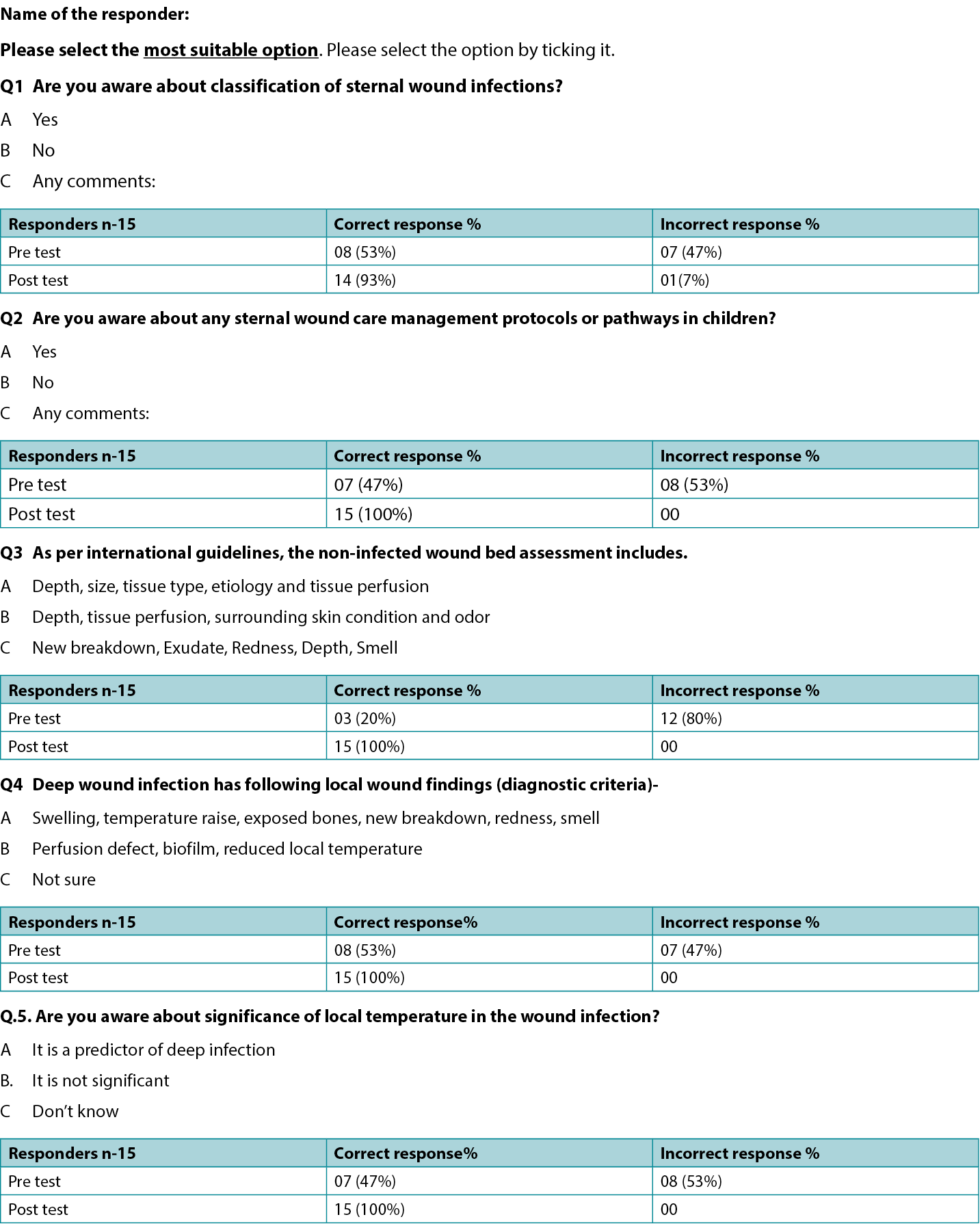

Methods Authors assessed knowledge about sternal wound care among nurses, surgeons, intensivists, and physicians in a pediatric cardiac surgical unit regarding the latest concepts such as wound bed preparation, NERDS and STONEES criteria for wound infection, and early use of NPWT or surgery. Management pathways for superficial and deep sternal wounds and a wound progress chart were prepared and introduced in practice after education and training.

Results The cardiac surgical unit team members demonstrated a lack of knowledge about the current concepts of wound care, although this improved after education. The newly proposed management pathway/algorithm for superficial and deep sternal wounds and a wound progress assessment chart was introduced into practice. Results in 16 observed patients were encouraging, leading to complete healing and no mortality.

Conclusions Managing pediatric sternal wounds after cardiac surgery can be streamlined through incorporation of evidence-based current wound care concepts. In addition, the early introduction of advanced care techniques with appropriate surgical closure further improves outcomes. A management pathway for pediatric sternal wounds is beneficial.

Introduction

Open heart surgery is usually done through the median sternotomy. The incision is associated with exposure of the thoracic soft tissues and the sternal bone. Pediatric patients are vulnerable to postoperative incision site dehiscence or infection (deep sternal infection 0.4% to 5.1%).1,2 The risk factors are prematurity, low weight, nutrition deficiencies, low resistance, comorbid conditions, genetic abnormalities, compromise of tissue vascularity, damage related to the surgical procedure, use of cardiopulmonary bypass, and perfusion issues. In addition, complexity of the procedures, repeat surgeries, and prolonged ventilation may delay wound healing. Wound dehiscence, infection (superficial or deep), and other related issues lead to a prolonged hospital stay, frequent dressing changes, a high cost of management, and high morbidity (50%).1,3 Moreover, this may bring adverse psychological impact on patients and their families. Because the wounds do not always follow the expected course of healing, an early detection and aggressive management of treatable issues is the key to success.

So far, literature on post-surgical sternal wounds have described sternal wound issues mainly in adult populations.1,3 However, in view of the lack of standardised guidelines for the management of such complications an individualised surgical approach and institutional preference is guiding the wound management.4 The issue is complicated when surgical site infection is confused with sternal dehiscence. Dehiscence may not always be associated with infection and therefore application of concepts of wound bed preparation, NERDS (Non-healing, Exudate, Red friable tissues, Debris, Smell) and STONEES (Size increasing, Temperature, Os [probes to bone], New breakdown, Edema/erythema, Exudate, Smell) criteria and interprofessional wound care in patients with sternal wound may need to be considered.5,6 The pediatric population with sternal wounds is a vulnerable group and therefore there is need to explore possibilities of effective and standardised wound care in children. The wound bed paradigm was described in nonsurgical adult patients but authors have attempted here to utilise the information for pediatric surgical population.

Methods

Problem Identification

The authors’ institution is a tertiary referral facility performing approximately 300 heart surgeries each year. The authors explored the available sternal wounds management guidelines and pathways in the pediatric population through a literature search. This also included assessment of local practice and knowledge of the wound care among the treating teams.

The team felt that there is a need for a wound care strategy based on the latest evidence-based information that includes components of wound care paradigm, patient centered concerns and incorporation of latest techniques that provides clear guidelines and streamline sternal wound care, uniformly.

Planning and Implementation

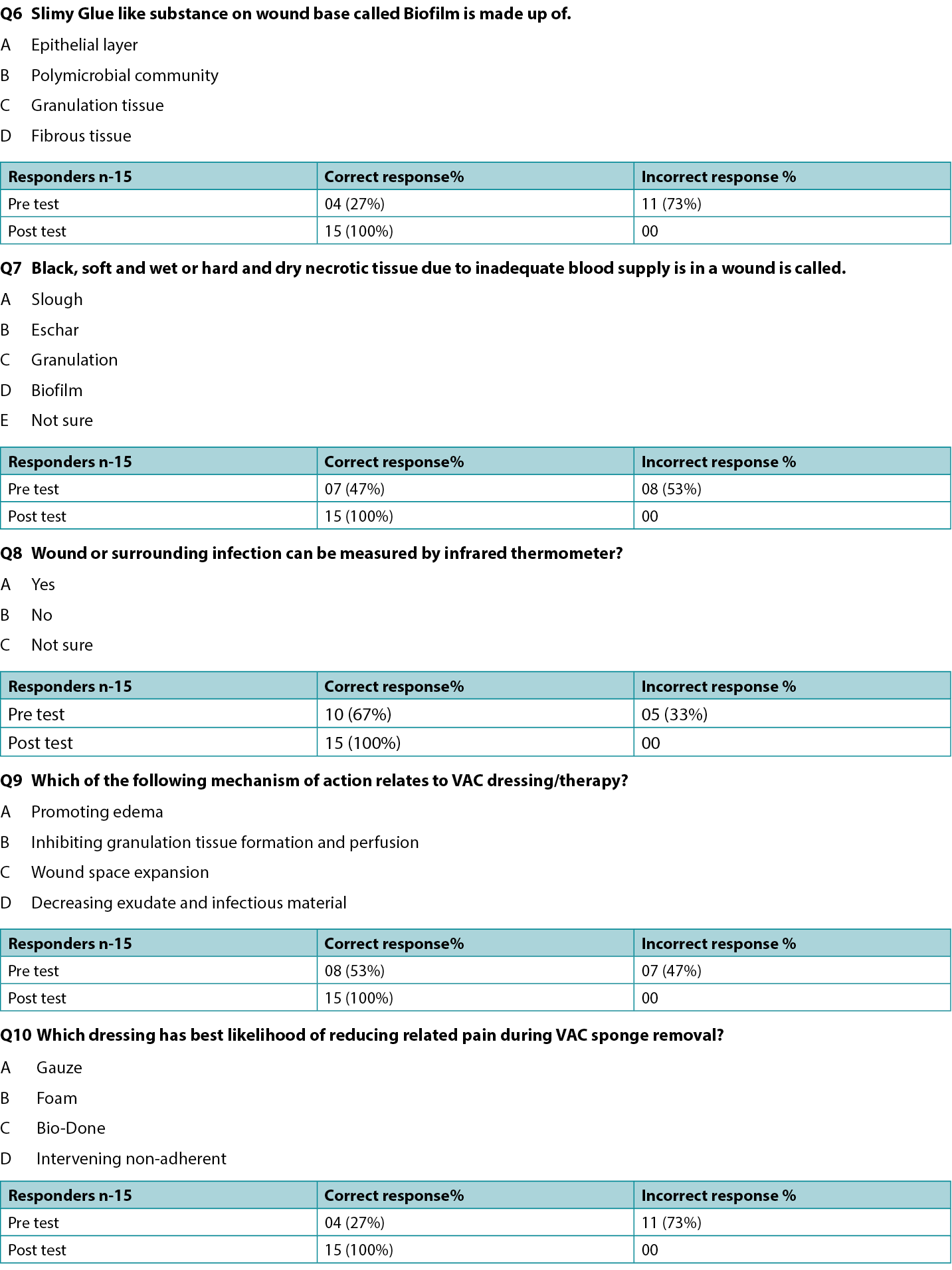

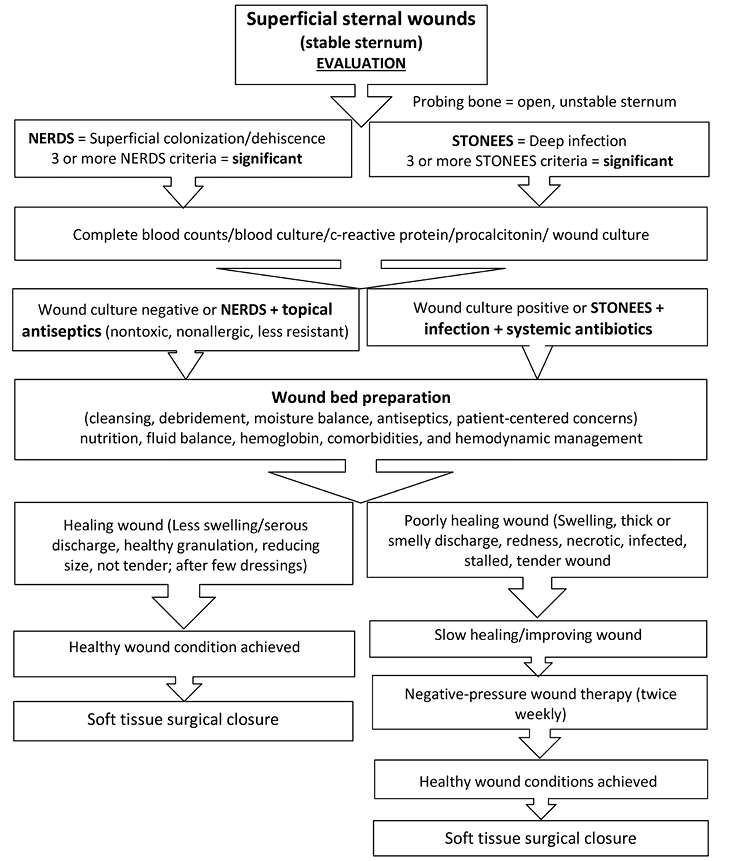

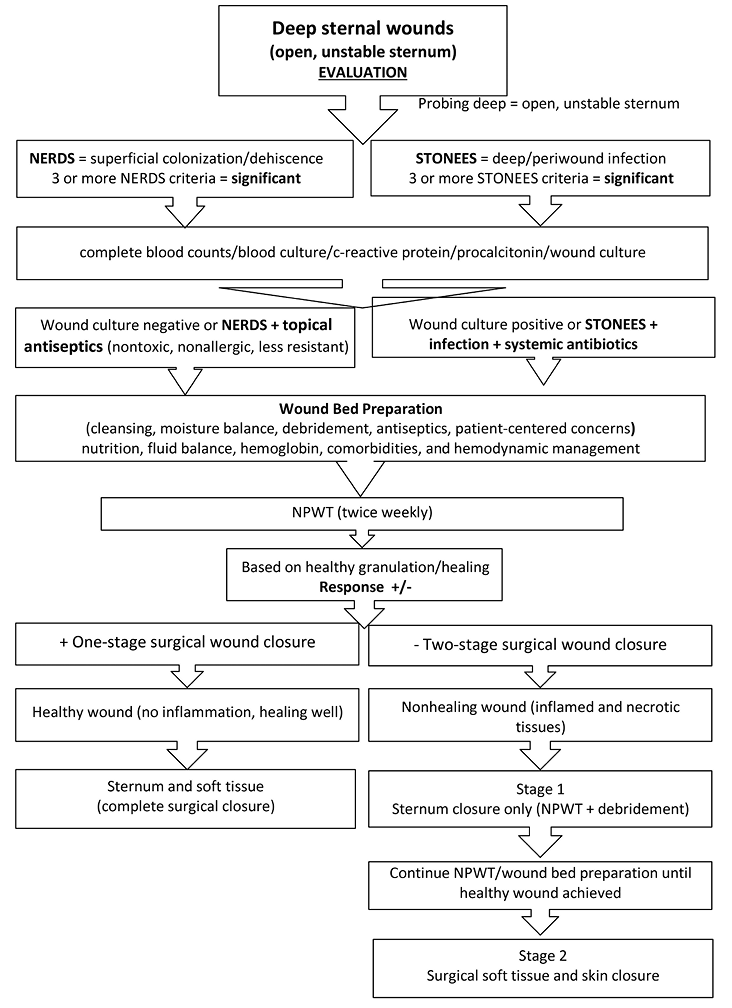

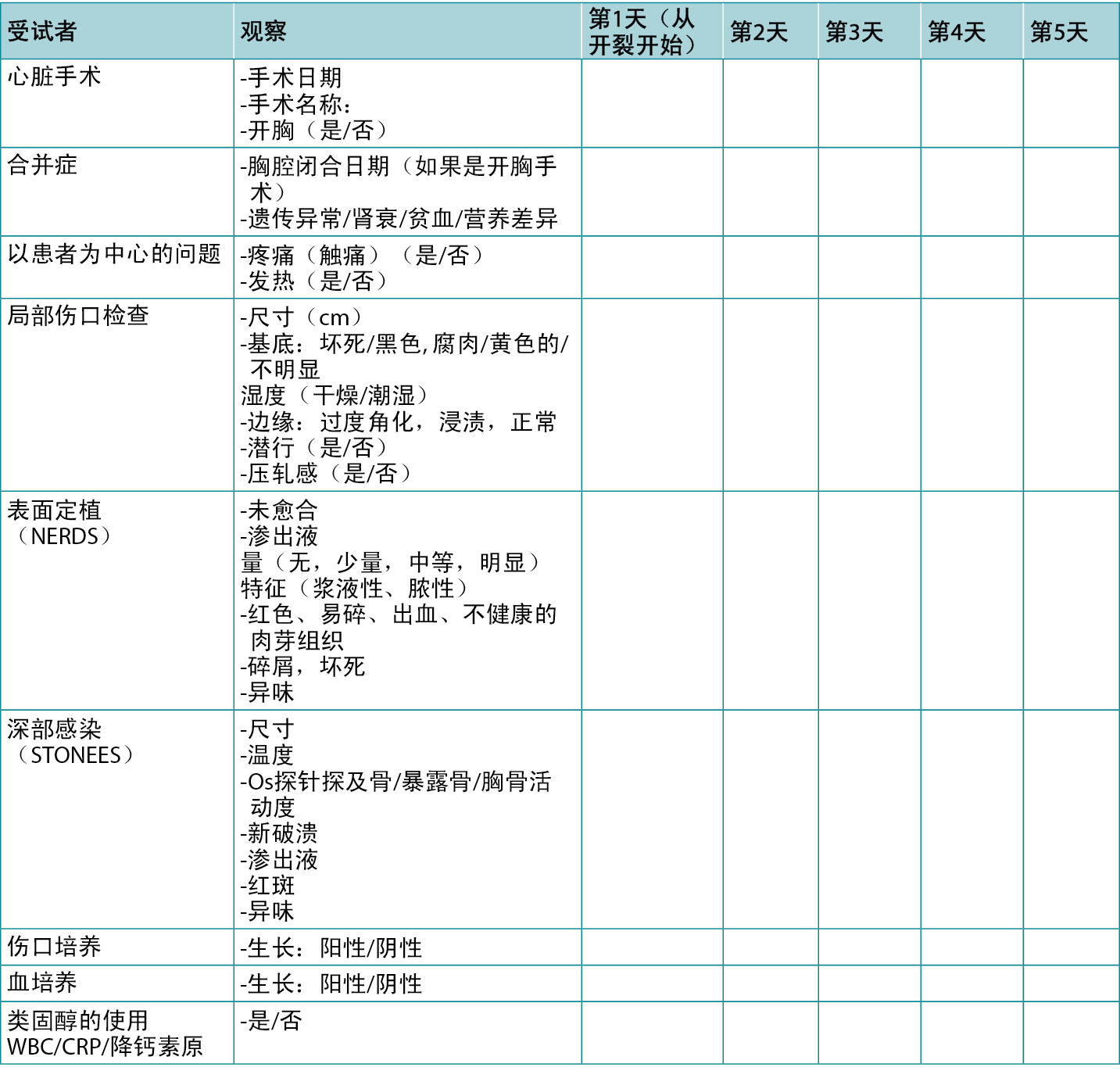

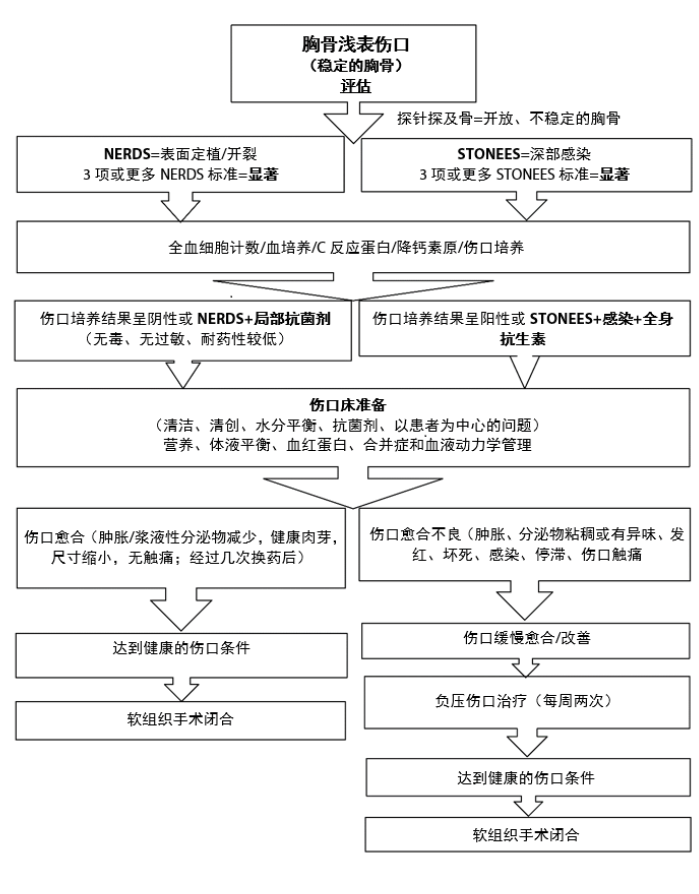

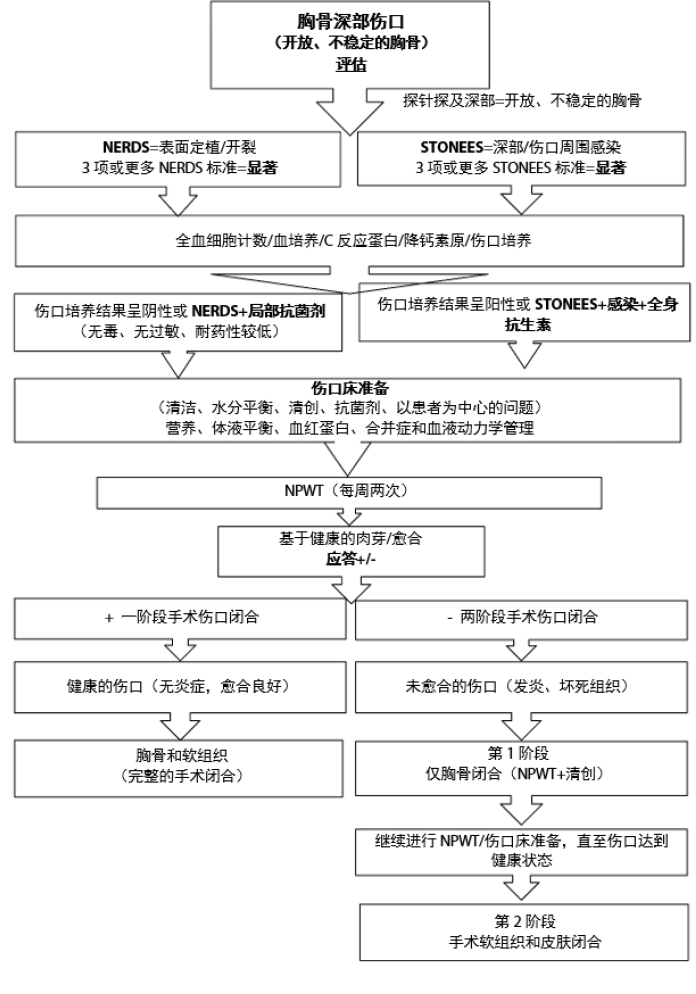

The planning required discussion with the surgical, nursing, and intensive care team to devise a universal pathway and management protocol so that the practice of sternal wound management could be standardised. Based on the review of literature, experience, established practices in other international centers and learning from the International Interprofessional Wound Care Course (IIWCC), the authors proposed wound assessment chart (Table 1) and two enablers depicting algorithms/pathways (Figures 1 and 2). The authors believed that the sternal wound healing process can be streamlined using algorithmic treatment method for early detection of infection, assessing depth of wound and the sternal stability in combination with early use of negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) and surgical intervention for a favorable outcome.

Table 1. Wound progress chart: cardiac surgery

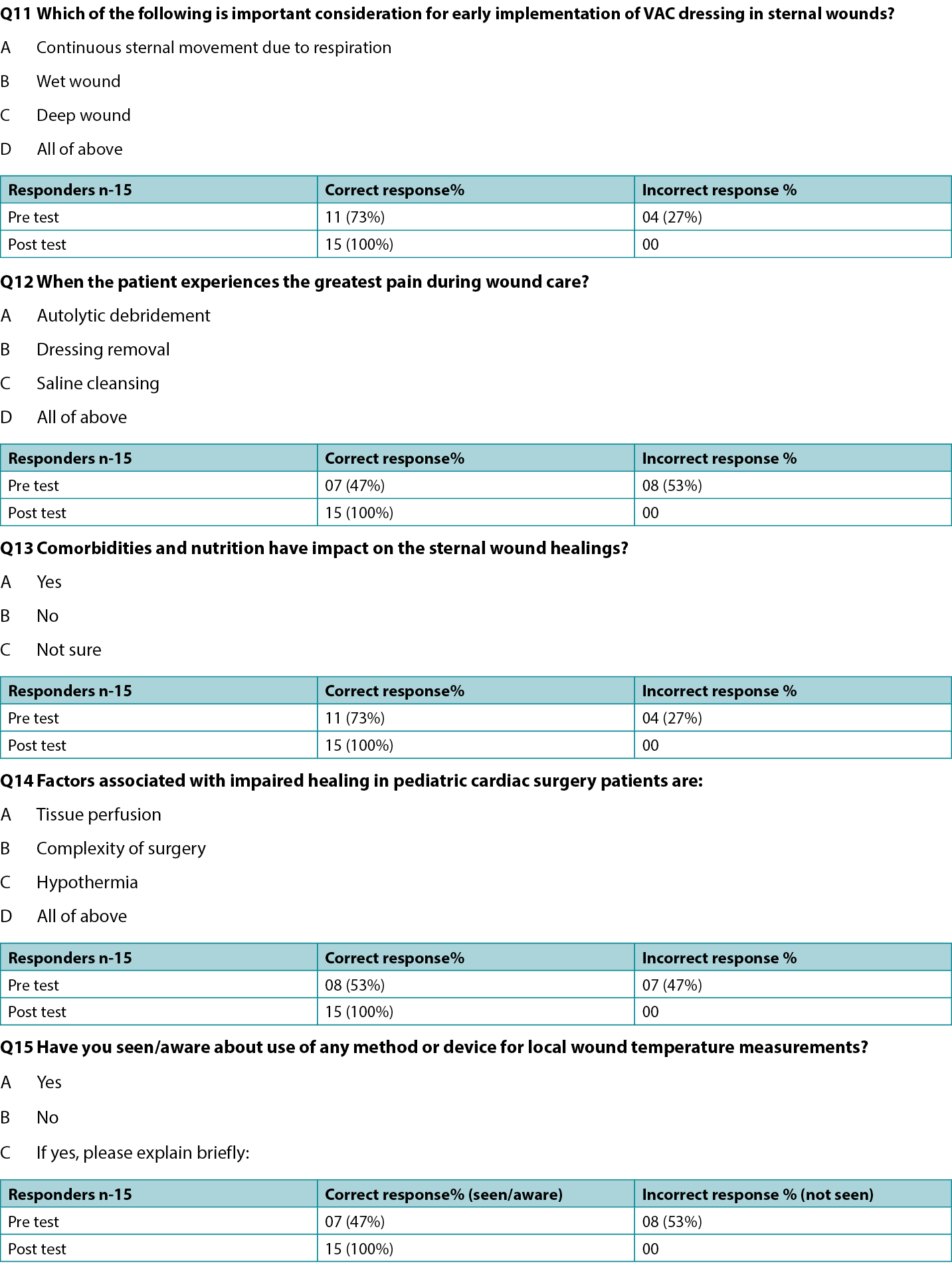

Figure 1. Superficial sternal wound management pathway

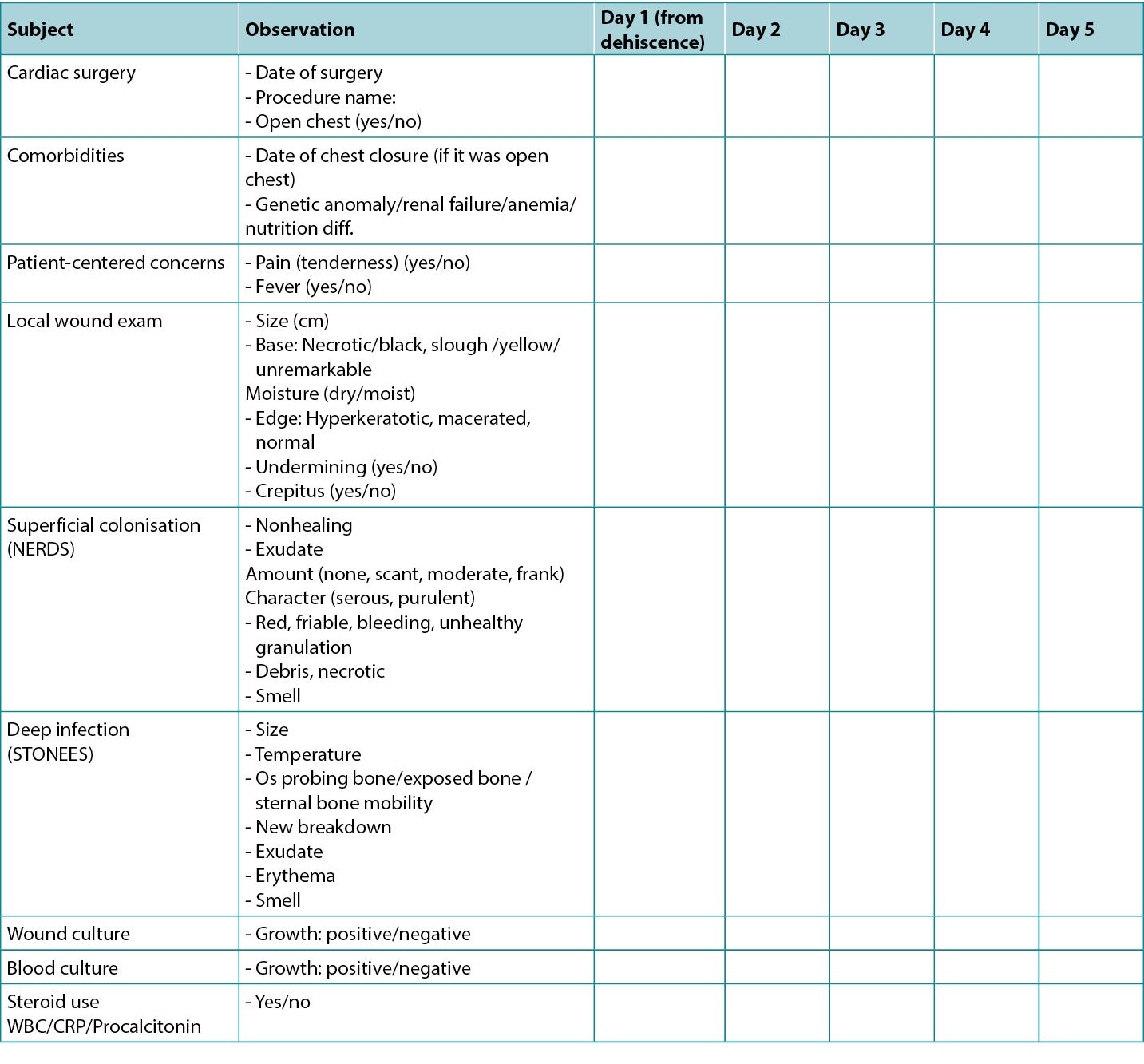

Figure 2. Deep sternal wound management pathway

Abbreviation: NPWT, negative-pressure wound therapy

Materials and Resources

Human Resources. Each member was assigned clear roles and responsibilities emphasising strong collaboration amongst each other. As per the plan, the patients were primarily assessed by the wound care nurse. The surgeon examined the patient for debridement, NPWT or closure of the wounds. The physician was responsible for comprehensive assessment of medical comorbidities. In addition, a plan of wound care, choice of dressing, antiseptics, need for antibiotics were decided by the physician and the wound care nurse. Intensive, postoperative, and critical care was provided by the intensive care staff. The primary cardiac anomaly or issues were treated by the pediatric cardiologists. Further, a dietitian managed nutrition status. Finally, any multisystemic comorbidity was managed by the respective medical or surgical discipline as and when required.

Tools Utilised

- Wound progress assessment chart (Table 1) and two enablers showing algorithms/pathways for wound management (Figures 1 and 2).

- Education: presentations/discussions within the group

- Existing medications/materials for wound care.

- Surgical procedures/equipment.

- Results of pre and post-implementation survey of the participating staff through questionnaire on existing and improved knowledge following education through lectures and group discussions (Supplemental Table, http://links.lww.com/NSW/A##).

Ethical Considerations

A written ethical approval of the study proposal was obtained from the Chief of the Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Department on behalf of the facility’s institutional review board. In addition, each patient’s parents were asked to provide written informed consents for treatment, photography, and the use of data for research and publication purposes by signing the institutional consent form, which has been kept in each patient’s file as per the hospital policy for confidentiality.

Implementation

During the IIWCC first-residential education session, the authors realised that there is often a difference in the knowledge of a specialised wound care professional and a nonspecialised cardiac surgery unit personnel. The authors realised the gap in their unit’s wound care practice resulted in inconsistent planning and decision making for the management of complex pediatric sternal wounds. Therefore, need for devising local standardised wound care guidelines based on latest evidence was strongly felt.

After discussions, it was decided to go ahead to print the final proposed pathways as an official document to be included for reference and practice. A review of literature on the sternal wound management was done in order to find an evidence-based practice to be implemented in the unit with special emphasis on wound bed preparation paradigm and NERDS/STONEES criteria for superficial colonisation and deep/periwound infection along with advanced wound care strategies.5,6 Usually, the sternal wounds are classified as per the nature of infection, depth of the wound or the time of onset from the surgery.7,8 The investigators defined the wound as superficial, if the extent of dehiscence or infection was limited to the skin or subcutaneous layer or a deep wound, where the muscle or bone was involved including mobile (unstable) sternal segments.7,8 In the authors’ opinion, the surgical management of sternal wound can be planned and managed efficiently, if the depth and the mobility of the sternum is taken into consideration early and addressed accordingly.

The wound assessment chart (Table 1) and two pathways (Figures 1 and 2) for sternal wound management were prepared. The Os (probing bone) criteria of the mnemonic STONEES was replaced by “unstable/mobile” or “completely exposed sternum” in this study. The treating unit members were assessed using a questionnaire on their existing knowledge about the wound bed preparation and pediatric sternal wound care. Education to the existing staff was provided with an emphasis on components of the wound care paradigm. A post education survey was conducted using a questionnaire to verify effectiveness and understanding of proposed wound care concepts within the team (Supplemental Table). The group started to work on the project by implementing the proposed strategies daily. Patient clinical data was recorded regularly.

Results

Process Evaluation

Our project did not require many resources because all logistics and patients were in one unit. An infrared handheld thermometer was introduced into practice, which is proven to be a cheap, easy to use, and cost effective means of detecting periwound temperature. With the available resources, it was appropriate to design a wound care assessment chart (Table 1) that incorporated NERDS/STONEES and specific clinical wound characteristics that indicate sternal wound healing progress in children.

The authors educated relevant staff about the importance of sternal wound screening as per prepared wound assessment chart and to follow the proposed superficial and deep sternal wound management pathways. With further practice and education, the whole team started following the proposed practice uniformly. A pre-implementation evaluation of existing wound care knowledge and practice was performed through a questionnaire. After education sessions, a post-implementation evaluation was performed. The evaluation results showed that majority of participants have acquired the necessary knowledge and understanding.

Once a wound dehiscence, discharge, or infection was suspected, daily progress was recorded in the wound assessment chart until a decision was made regarding type of wound care and plan to be followed as per proposed wound care algorithm.

Qualitative Outcomes

- Feedback taken from the charge nurse wound care, staff nurses and wound care team including pre and postimplementation survey.

- All were satisfied with improvement in quality of wound care. However, it would require further data to show the impact of these pathways and protocol on sternal wound management over the long term.

- Patient data related to the wound management as an example from respective group of patients in the form of photograph.

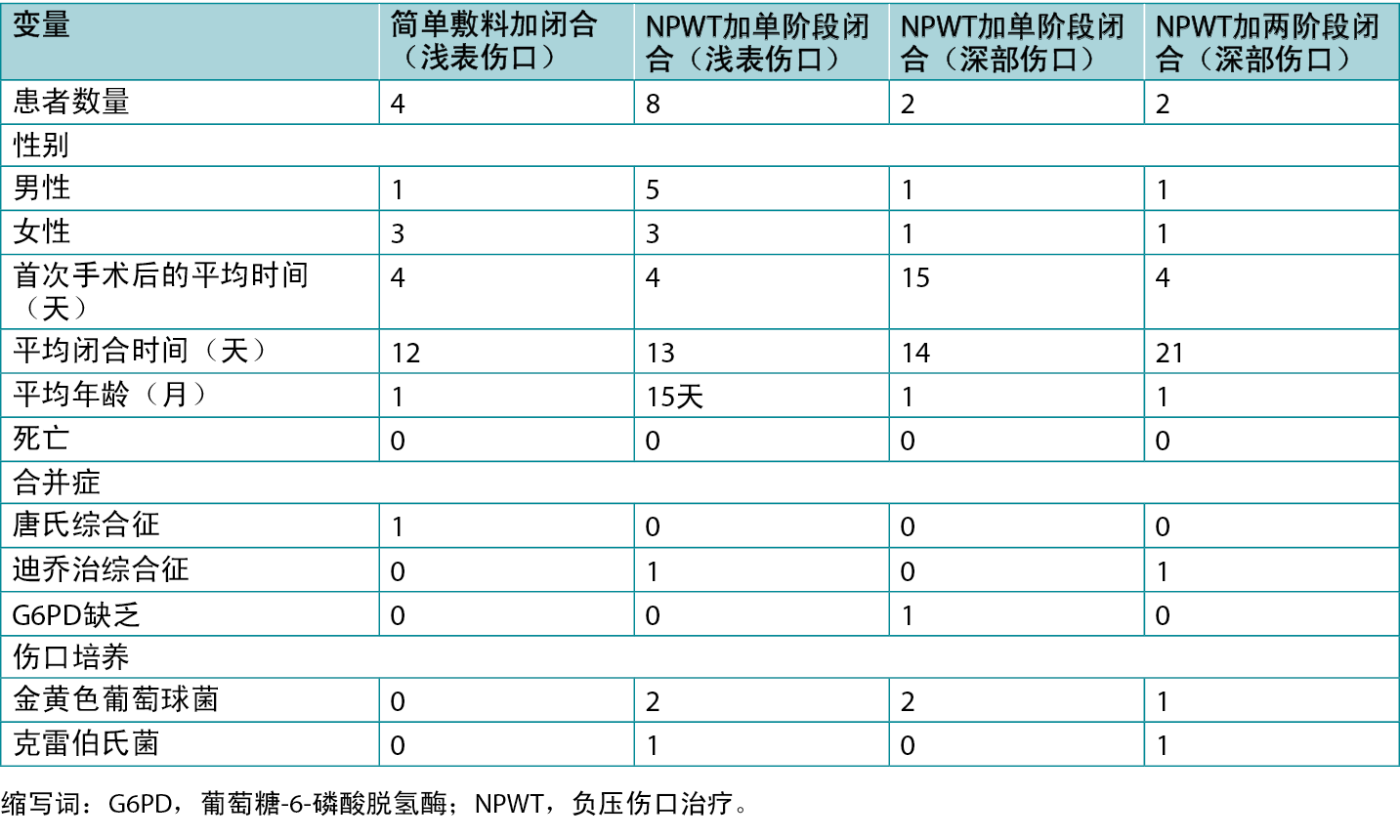

Quantitative Outcomes

The authors recruited patients from June 2020 to December 2020; a total of 16 patients were evaluated for postcardiac surgical wound issues (Table 2). Of these, four had simple wound dehiscence during the first week after surgery. Wound bed preparation was started and these superficial wounds were managed with cleansing, debridement, and dressings. The soft tissue closure was achieved in all the patients by day 12 (average). There was no mortality.

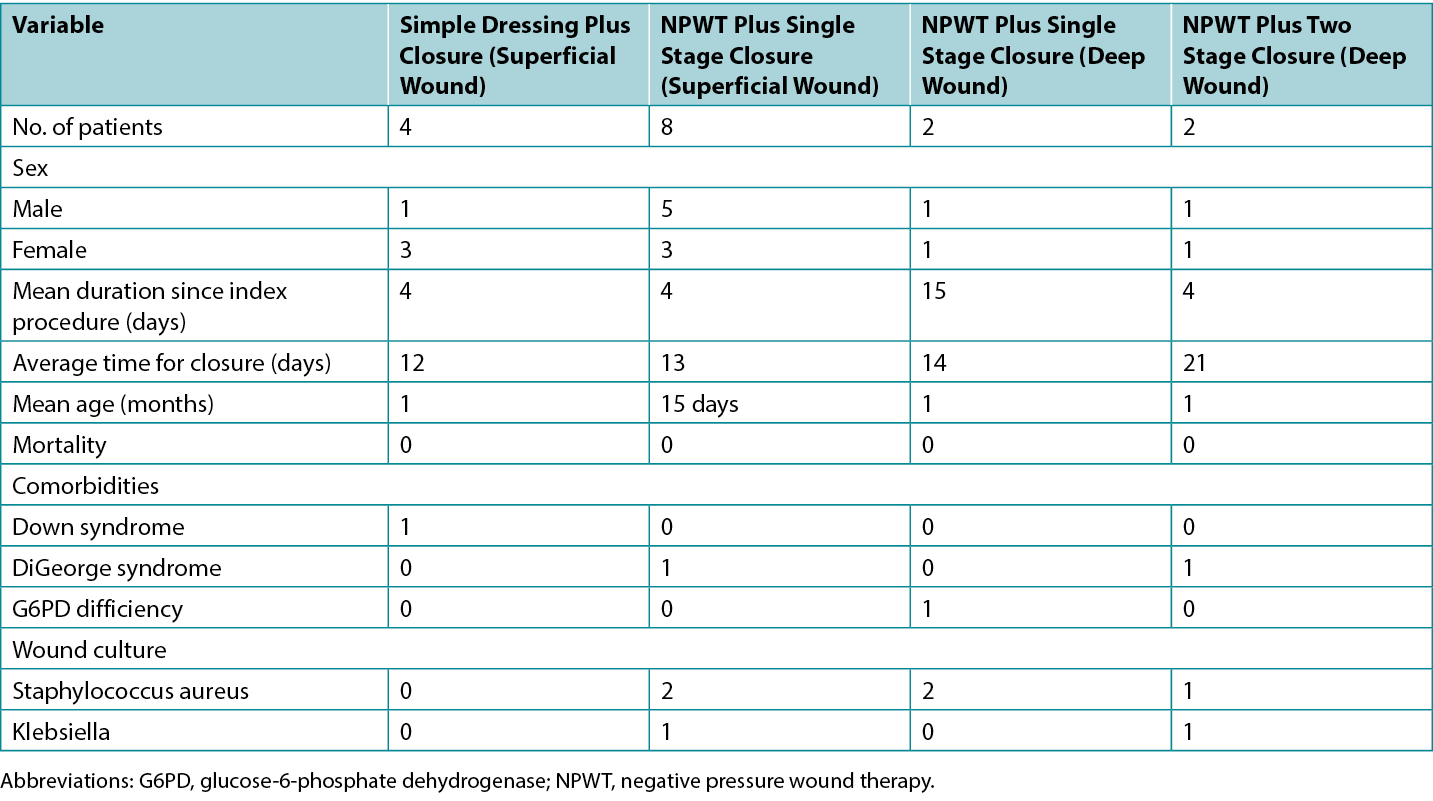

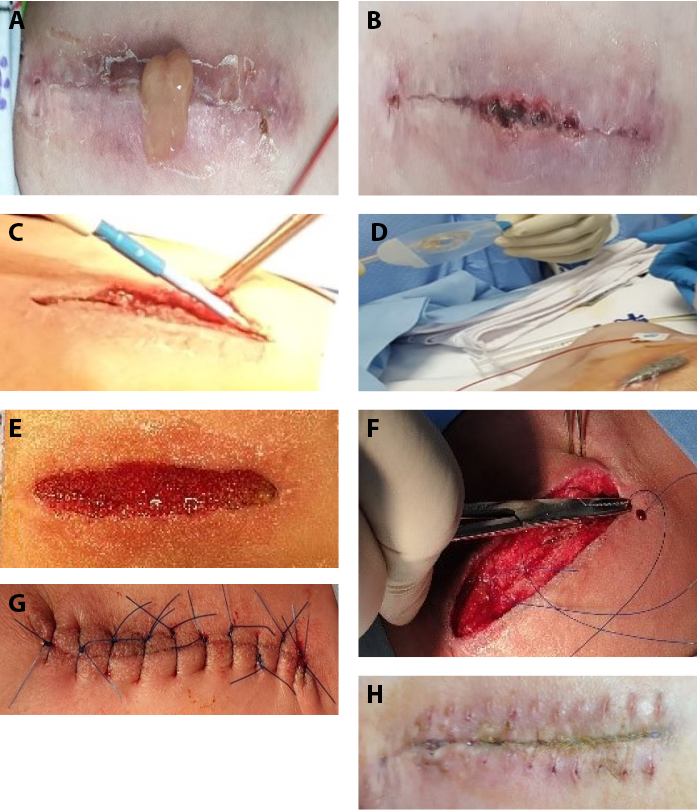

Table 2. Distribution of 16 observed cases: type of wounds and therapy

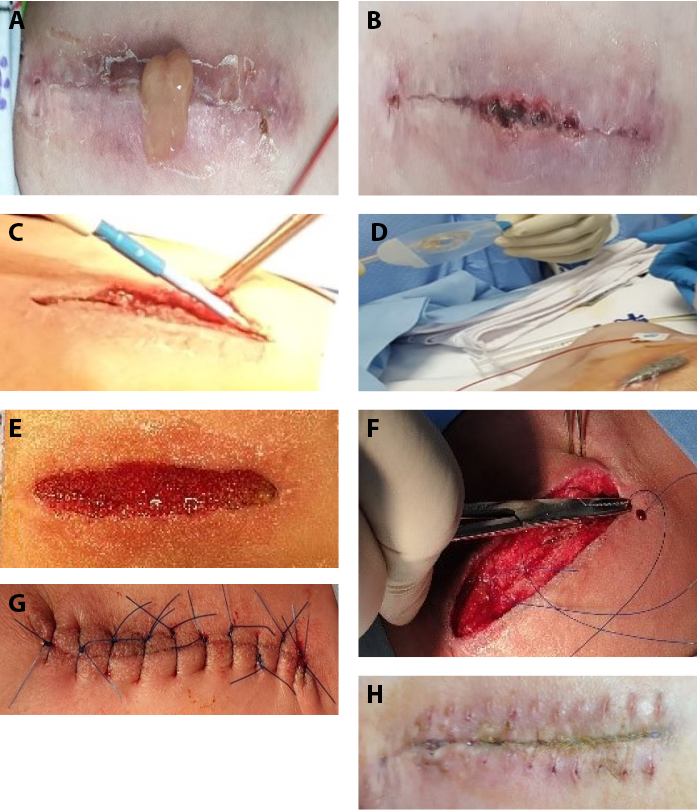

There were 8 patients with superficial wounds (stable sternum group) who developed wound gapping and seropurulent discharge 4 days after surgery (average). Wounds were explored and enlarged to clean, debride, and apply NPWT. The wound culture was positive for three patients (Staphylococcus aureus in two and Klebsiella species in one) who received antibiotics accordingly. The twice- weekly regimen of dressing change and debridement was applied resulting in single-stage closure of wound in all the patients on average 13 days from onset (Figure 3). There was no mortality.

Figure 3. Superficial wound with negative-pressure wound therapy (npwt) and one-stage wound closure

A and B, 6-month-old girl with cyanotic heart disease 5 days after open heart surgery. Incision-site inflammation and abscess. C, Drainage and debridement of sterile superficial purulent collection. D, NPWT. E, Wound with healthy granulation at day 8 after NPWT. F and G, Soft-tissue closure at day 11 after NPWT. H, Day 10 after soft tissue closure and stitch removal.

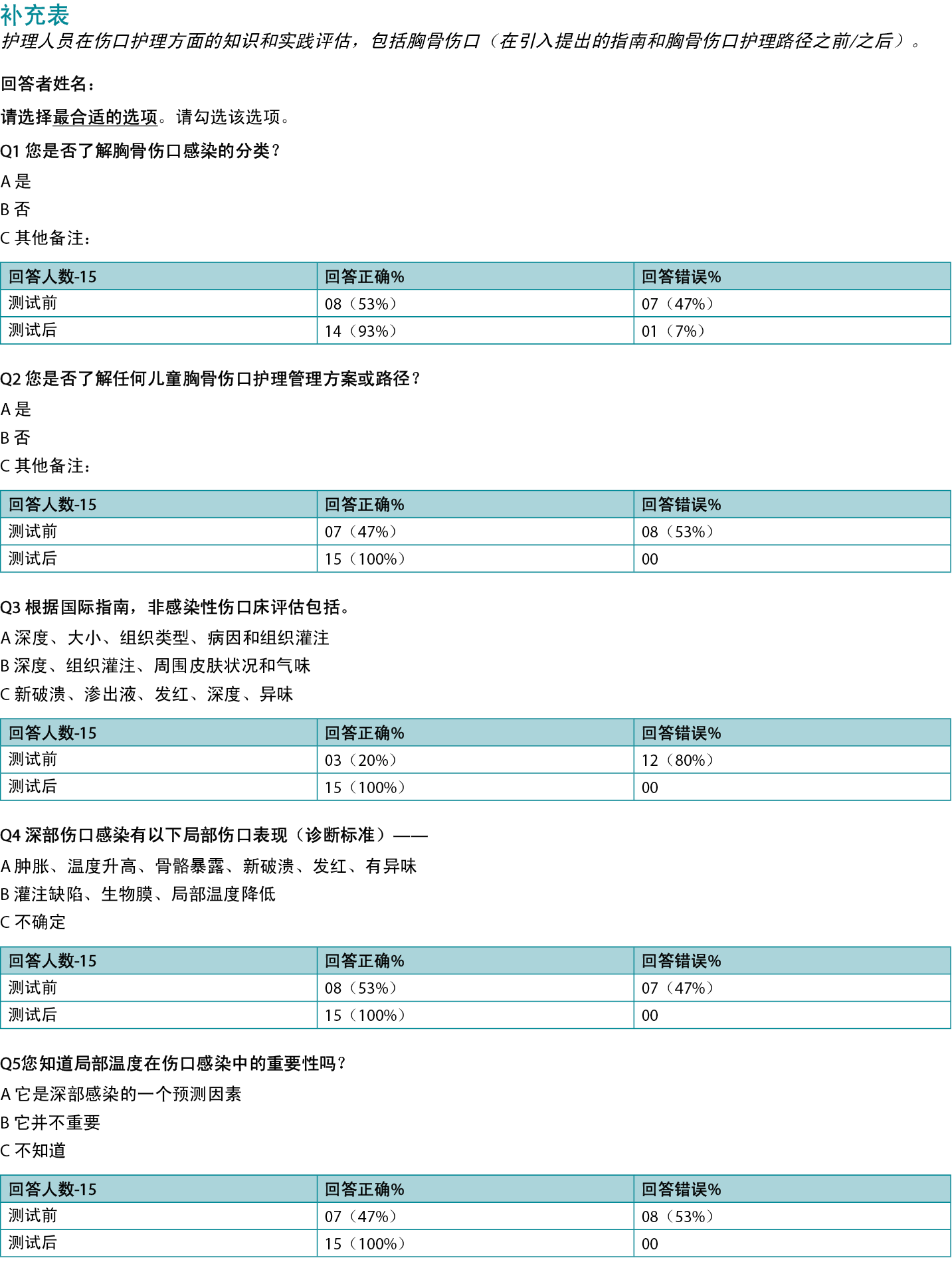

Four patients were treated for deep sternal wounds where the sternum was unstable and mobile. Two patients developed sinus and swelling over the sternum 1 month after the initial operation. The remaining two developed deep infection and wound dehiscence within the first week of surgery. The wound cultures were positive for all the patients (Staphylococcus in three and Klebsiella pneumoniae in one). The wounds were explored, debrided, and after obtaining a sample for culture, NPWT was started immediately in addition to systemic antibiotics. A twice weekly regimen of dressing change with cleansing and debridement resulted in single-stage (sternum with soft tissue) closure of the wounds in two patients by the end of 2 weeks. However, two patients with deep sternal wounds (instable sternum) had poor wound healing that required sternal closure first at the end of 2 weeks and then soft tissue closure at second stage by the end of third week, after continuation of wound care with NWPT (figure 4). K pneumoniae was present in one patient. There was no mortality in this group either.

Figure 4. Deep sternal wound with two-stage closure after negative-pressure wound therapy (npwt)

A and B, Incision site inflammation/swelling and drainage and debridement on postoperative day 8. C, NPWT. D, Day 9 after debridement and NPWT. E, Day 15 after NPWT. F and G, Sternal closure (stage 1) on day 17 of NPWT. H, Continuation of NPWT on the superficial tissues. I, Healing with granulation on day 23 of NPWT. J, Stage 2 soft tissue closure.

All the patients were given pediatric intensive care treatment that includes daily fluid balance, care of comorbid conditions, anemia, nutrition and prevention of pressure injuries. In addition, they were given oxygen, analgesia, and general anesthesia during the surgical procedures. Families were educated and counselled at all crucial times.

Discussion

The best approach in dealing with sternal wound in children after cardiac surgery is prevention of infection and care of the patient as a whole, considering all clinical factors interfering with the patient care and outcomes.2 Typically, CDC guidelines are used to diagnose sternal wound infections.9 This includes duration of onset of the signs or symptoms after surgical procedure (within 30 days) and presence of pus or a positive microbial culture. In addition, presence of pain, tenderness, fever, or erythema is considered, if surgeon has to reopen the incision site due to a suspected infected swelling.9 Clinicians must be aware that in pediatric populations, initially there may be only a wound dehiscence but in due course it may be complicated by other conditions. Poor skin condition, age, prematurity, chromosomal anomalies, complex surgical procedures, repeat surgeries, and poor perfusion are some of the common causes of wound dehiscence. Therefore, an evidence-based systematic approach to wound care including the principles of wound bed preparation, advanced wound care therapy, and use of appropriate surgical techniques tailored to the patients for early recovery is ideal for vulnerable populations with a dehisced sternal wound.4

There is a lack of information in the available literature regarding optimal sternal wound management (infected or not) in the pediatric population, especially those who undergo complex cardiac surgical procedure.4 Therefore, these initial observations and proposed management strategy may be helpful in improving outcomes and encourage other surgical units to follow similar practice. In addition, in the absence of CDC criteria of surgical site infection, a wound assessment from the onset of tissue dehiscence as per validated NERDS and STONEES criteria will not only help in detecting local evidence of critical colonisation or deep infection early to halt the process by taking advantage of the methods applied in the wound bed preparation.

The most important factor in the management of sternal wounds is to prevent or identify infection. Infection is associated with high mortality, prolonged hospital stays, and high cost of the treatment.1,3,10 A cross-sectional validation study of using NERDS and STONEES to assess bacterial burden in the wounds in the adult general population concluded that any three criteria were found to provide sensitive and specific information about the amount of bacteria present in the wound when used by expert clinicians.5,6 The landmark study by Woo and Sibbald6 validated that by collating any three clinical signs exhibited in the assessed wounds, the sensitivity for NERDS increased to 73.3% (specificity 80.5) and to 90% (specificity 69.4) for STONEES. Therefore, a knowledge of NERDS and STONEES criteria is crucial during initial assessment of any sternal wound and may help in identifying critical colonisation or local infection. This component was incorporated in the proposed wound care pathways as first step to prevent or treat it at the earliest.

The authors found deficiencies in their unit regarding wound care knowledge. The systemic antibiotics were used when blood culture was positive or three STONEES criteria were present. In addition, many patients had comorbid conditions, congenital malformations, invasive procedures, or catheters during intensive care that required systemic antibiotics.

The next step included overall wound assessment considering wound bed preparation principles including patient-centered concerns. The incorporation of debridement, cleansing, and dressing materials as per the wound condition and correction of comorbidities such as pain management was addressed. This helped to stratify wounds, evaluate response to the treatment, and further plan wound management in terms of need and timing of appropriate advanced therapies.

In the last part of management pathway, the role of advanced techniques including surgical procedures was considered and implemented, which helped expedite wound healing.

The sternal area has little muscle or soft tissue cover, and so the area does not have a generous blood supply.1,2,4,9 In addition, the close proximity of bone to the skin facilitates entry of superficial infection to the deeper tissues. The area is under higher stress due to continuous respiratory movement.9 All of these factors not only make sternal wounds a difficult substrate to heal but justify the early use of advanced therapy or surgery.3 Among these strategies, NPWT has proven successful for use in pediatric cardiac surgical patients.11

Therefore, the proposed strategy recommends NPWT at an early stage to keep the area dry and relatively stable to promote healing. NPWT stimulates blood flow, granulation tissue and reduce inflammatory response. In addition, it maintains a moisture balance by countering the effect of friction and resultant inflammation. It also helps expedite rate of healing, reduces frequency of dressing, manpower and may affect hospitalisation time and cost.1,4,8,10,11 The twice weekly application of the NPWT was based on assumptions to keep the wound dry, evaluate the condition more frequently to intervene early debridement or closure and reduce the recovery time to achieve overall benefits related to the hospitalisation, cost, and logistics. In some situations, with deep infection or wet wounds, the need for dressing change may be variable and frequent.

In children, soft and friable tissues with future growth potential are limitations for implementation of invasive surgical options.1,2,4 Therefore, direct soft-tissue closure with a limited pectoralis major muscle advancement and staged sternal bone closure is recommended. The role of surgery in this decision-making was dependent upon the nature of the wound bed, presence of infection, sternal mobility, and depth of the wound. In deep wounds with an unstable sternum, the sternal closure was considered one-stage (all layers closed once healthy, healable tissue achieved). However, in case of more resistant wounds, a sternal closure was attempted as a first step to protect mediastinal tissues and provide stability. Once the superficial layer was found to be healthy, a second-stage soft tissue closure was done (two-stage closure). This staging helps to reduce wall tension and risk of further dehiscence.

In all of the patients, antibiotics were used according to the culture and sensitivity, or empirically when signs of local or systemic infection were seen. In addition, care of comorbid conditions, nutrition support, and parent counseling were also provided through an interprofessional approach.

Through proposed wound care pathways and education, the investigators not only improved the knowledge but also have introduced the wound care practice in a national center of excellence. The authors incorporated a strategy to educate and inform parents about prevention, care and management of issues related to cardiac surgery in children such as incisional pain, infection, wounds, rehabilitation, and psychological support that helps in holistic care of such patients.

Limitations

This project was limited to the introduction of wound care pathways and a change in the practice only as a first step. A small number of cases were recorded as observations or case studies. Ideally, these tools should be analysed in the long-term with larger patient populations. In addition, the role of infrared thermometry was introduced but was not used uniformly because it was a novel addition to the authors’ unit and it is difficult to compare two identical parts in the chest, unlike comparing limb temperatures. Therefore, authors compared the temperature over the sternal area and the abdominal wall as an alternative, but the reliability of these results was not evaluated.

Conclusions

The management of sternal wound after cardiac surgery in the pediatric population can be streamlined through incorporation of evidence-based guidelines and components of wound care paradigm through standardised management pathways based on interprofessional care concepts. This will help in avoiding individual preferences and practice in the treating units to compare the effectiveness and improvement in the long-term outcomes. In addition, early implementation of NPWT and appropriate use of surgical procedure expedite wound healing in children with postsurgical sternal wounds and that provide comprehensive benefit to the patient and the organisation. A long-term study is required to observe real impact of the proposed concepts and management pathways.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emadullah Raidullah, MD, Medical Practitioner, Internal Medicine; Atiq Ur Rehman, MD, Specialist, Internal Medicine; Ms Beji George, Staff Nurse; and the entire wound care team at their organisation for their help in patient management and preparation of the charts and manuscript. This study was conducted as a selective for the International Interprofessional Wound Care Course (IIWCC) Abu Dhabi 2021. The authors thank the faculty members of the IIWCC and their colleagues for their constructive advice, evaluation, and guidance. Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (www.ASWCjournal.com).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

小儿心脏外科患者的胸骨伤口管理:结合伤口床准备范式和早期-先进治疗原则的伤口护理路径的实施

Neerod Kumar, Muhammad Shafique, Raisy Thomas, Salvacion Pangilinan Cruz, Gulnaz Tariq, Laszlo Kiraly

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.2.13-23

摘要

目的 目前关于心脏手术后儿童胸骨伤口管理的研究较少。作者运用跨专业伤口护理的概念,结合包括负压伤口治疗(NPWT)和手术方法在内的伤口床准备范式,制定了儿科胸骨伤口护理方案,以加快和简化儿童的伤口护理。

方法 作者评估了小儿心脏外科的护士、外科医生、重症监护医生和医师对胸骨伤口护理的了解,包括伤口床准备、伤口感染的NERDS和STONEES标准以及NPWT或手术的早期应用等最新概念。在教育和培训之后,编写了胸骨浅表和深部伤口的管理路径和伤口进展表,并在实践中引入。

结果 心脏外科团队成员表现出对目前的伤口护理概念缺乏了解,但经过培训后这种情况有所改善。新提出的胸骨浅表和深部伤口的管理路径/算法以及伤口进展评估表已被引入实践中。16名受观察患者的结果令人鼓舞,患者均完全康复,未出现死亡。

结论 通过结合循证的当前伤口护理概念,可以简化心脏手术后的小儿胸骨伤口管理。此外,及早引入先进的护理技术,并进行适当的手术闭合,可以进一步改善结果。建立儿科胸骨伤口的管理路径大有裨益。

引言

开胸心脏手术通常通过正中胸骨切开术进行。切口与胸腔软组织和胸骨的暴露有关。儿童患者术后易出现切口部位开裂或感染(胸骨深部感染0.4%至5.1%)。1,2风险因素是早产、体重过轻、营养不足、抵抗力低下、合并症、遗传异常、组织血管受损、外科手术相关性损伤、体外心肺循环的使用和灌注问题。此外,手术的复杂性、重复手术和长时间的通气可能会延迟伤口愈合。伤口开裂、感染(浅表或深部)和其他相关问题会导致住院时间延长、换药频繁、管理成本高、发病率高(50%)。1,3此外,还可能会给患者及其家属带来不良的心理影响。由于伤口并不总是遵循预期的愈合过程,及早发现并积极处理可治疗的问题是成功的关键。

到目前为止,关于术后胸骨伤口的文献主要描述的是成人群体的胸骨伤口问题。1,3然而,鉴于缺乏管理此类并发症的标准化指南,个体化的手术方法和机构偏好正指导着伤口管理。4当手术部位感染与胸骨开裂混淆时,问题就会变复杂。伤口开裂不一定与感染有关,因此可能需要考虑在胸骨伤口患者中应用伤口床准备、NERDS(未愈合、渗出液、红色易碎组织、碎屑、异味)和STONEES(尺寸増加、温度、Os[探针探及骨]、新破溃、水肿/红斑、渗出液、气味)标准和跨专业伤口护理的概念5,6。有胸骨伤口的儿科人群是一个弱势群体,因此有必要讨论在儿童中进行有效和标准化伤口护理的可能性。伤口床范式是在非手术成人患者中描述的,但作者在此试图将信息用于儿科手术人群。

方法

问题识别

作者所在的机构是一家三级转诊机构,每年进行约300例心脏手术。作者通过文献检索,探讨了儿科人群中现有的胸骨伤口管理指南和路径。其中也包括对治疗团队的当地实践和伤口护理知识的评估。

研究小组认为,有必要根据最新的循证信息制定伤口护理策略,其中包括伤口护理范式、以患者为中心的关注点以及纳入最新技术,从而提供明确的指导方针,统一简化胸骨伤口护理。

计划和实施

该计划需要与外科、护理和重症监护团队进行讨论,设计通用的路径和管理方案,从而实现胸骨伤口管理实践的标准化。基于对文献、经验、其他国际中心既定实践的回顾以及国际跨专业伤口护理课程(IIWCC)的学习,作者提出了伤口评估表(表1)和描述算法/路径的两个实现程序(图1和图2)。作者认为,使用算法治疗方法可以简化胸骨伤口的愈合过程,在早期发现感染,评估伤口深度和胸骨稳定性,结合负压伤口治疗(NPWT)的早期使用和手术干预,可以获得良好的效果。

表1.伤口进展表:心脏手术

图1.胸骨浅表伤口管理路径

图2.胸骨深部伤口管理路径

缩写词:NPWT,负压伤口疗法

材料和资源

人力资源。每个成员都被分配了明确的角色和责任,强调彼此间的紧密合作。按照计划,患者主要由伤口护理护士进行评估。外科医生对患者进行了清创、NPWT或伤口闭合检查。内科医生负责对内科合并症进行全面评估。此外,伤口护理计划、敷料的选择、消毒剂、是否需要抗生素均由内科医生和伤口护理护士决定。重症监护、术后护理和危重病人护理由重症监护人员提供。原发性心脏异常或问题由小儿心脏科医生治疗。此外,一名营养师负责管理营养状况。最后,任何多系统合并症均根据需要由各自的内科或外科学科进行管理。

使用的工具

- 伤口进展评估表(表1)和两个显示伤口管理的算法/路径的实现程序(图1和图2)。

- 教育:小组内的演讲/讨论。

- 现有的伤口护理药物/材料。

- 手术程序/设备。

- 通过调查问卷对参与的工作人员进行实施前和实施后的结果调查,即现有知识和通过讲座和小组讨论进行教育提升后的知识(补充表,http://links.lww.com/NSW/A##)。

伦理事宜

该研究提案获得了代表机构审查委员会的小儿心脏外科主任的书面伦理批准。此外,每位患者的父母都被要求签署书面机构知情同意书,同意治疗、拍照以及将数据用于研究和出版目的,根据医院的保密政策,该同意书保存在每位患者的档案中。

实施情况

在IIWCC首次住院教育会议上,作者意识到,专业伤口护理人员和非专业心脏外科人员在知识上往往存在着差异。作者意识到,他们所在科室的伤口护理实践中存在差距,导致对复杂的儿童胸骨伤口的管理计划和决策不一致。因此,我们强烈认为需要根据最新的证据制定当地标准化的伤口护理指南。

经过讨论,决定印刷最终的拟议路径,作为正式文件列入,以供参考和实践。我们对胸骨伤口管理的文献进行了回顾,以便找到一种循证的做法,在科室中实施,并特别强调伤口床准备范式、浅表定植和深部/伤口周围感染的NERDS/STONEES标准以及先进的伤口护理策略。5,6通常,胸骨伤口根据感染性质、伤口深度或手术开始时间进行分类。7,8如果裂开或感染的范围仅限于皮肤或皮下层,或累及肌肉或骨骼的深层伤口,包括可活动的(不稳定的)的胸骨段,则研究者将伤口定义为浅表伤口。7,8作者认为,如果在早期考虑胸骨的深度和活动度并进行相应处理,胸骨伤口的手术治疗是可以有效规划和处理的。

我们准备了伤口评估表(表1)和胸骨伤口管理的两个路径(图1和2)。在这项研究中,ÅgSTONEESÅh中的Os(探针探及骨)标准替换为Åg不稳定/可移动Åh或Åg胸骨完全暴露Åh。采用调查问卷的方式,评估了治疗科室成员关于伤口床准备和小儿胸骨伤口护理的现有知识。对现有的工作人员进行了教育,重点是伤口护理范式的组成部分。以调查问卷的形式进行了教育后的调查,以验证团队内部对拟议伤口护理概念的有效性和理解(补充表)。该小组开始通过每天执行拟议的策略来开展项目工作。定期记录患者的临床数据。

结果

过程评估

我们的项目不需要很多资源,因为所有的后勤和患者都在一个科室。在实践中引入了红外手持式测温仪,事实证明这是一种廉价、易用、经济有效的检测伤口周围温度的方法。利用现有的资源,可以设计一个伤口护理评估表(表1),其中包含NERDS/STONEES和表明儿童胸骨伤口愈合进展的具体临床伤口特征。

作者向相关工作人员介绍了按照准备好的伤口评估表进行胸骨伤口筛查的重要性,并且要求他们遵循提出的胸骨浅表和深部伤口管理路径。随着进一步的实践和培训,整个团队开始统一遵循所建议的做法。通过调查问卷对现有的伤口护理知识和实践进行了实施前的评估。培训课程结束后,进行了实施后评估。评估结果显示,大多数参与者都获得了必要的知识和理解。

一旦怀疑有伤口开裂、分泌物或感染,就在伤口评估表上记录每天的进展情况,直至决定伤口护理的类型,并根据提出的伤口护理算法制定计划。

定性结果

- 从伤口护理主管护士、科室护士和伤口护理小组获得反馈,包括实施前和实施后的调查。

- 所有人都对伤口护理质量的改善感到满意。然而,还需要进一步的数据来显示这些路径和方案对胸骨伤口管理的长期影响。

- 以照片的形式从各患者组中获得与伤口管理有关的患者数据作为示例。

定量结果

作者于2020年6月至2020年12月招募患者;共有16名患者接受了心脏手术后伤口问题的评估(表2)。其中4名患者在术后第一周出现单纯的伤口裂开。因此开始准备伤口床,并对这些浅表伤口进行清洁、清创和敷料包扎处理。所有患者在第12天(平均)实现了软组织闭合。无死亡病例。

表2.16个观察病例的分布:伤口类型和疗法

8名浅表伤口患者(稳定胸骨组)在术后4天(平均)出现伤口裂开和脓性分泌物。探查并扩大伤口,从而进行清洁、清创并应用NPWT。三名患者的伤口培养结果呈阳性(两名为金黄色葡萄球菌,一名为克雷伯氏菌),他们接受了相应的抗生素治疗。采用每周两次的换药和清创方案,所有患者的伤口平均在开始后13天实现了单阶段闭合(图3)。无死亡病例。

图3.采用负压伤口治疗(NPWT)和一阶段伤口闭合的浅表伤口

四名患者因胸骨深部伤口而接受治疗,胸骨不稳定且可移动。两名患者在初次手术后1个月出现胸骨上的窦道和肿胀。其余两名患者在手术后第一周内出现深部感染和伤口开裂。所有患者的伤口培养结果均为阳性(3例为葡萄球菌,1例为肺炎克雷伯菌)。对伤口进行探查、清创并获得培养样本后,使用全身性抗生素,并立即开始进行无创护理。每周换药两次,并进行清洁和清创,在2周后,两名患者的伤口实现了单阶段(胸骨与软组织)闭合。然而,两名胸骨深部伤口(胸骨不稳定)患者伤口愈合不佳,需要继续使用NWPT进行伤口护理,在第2周结束时首先进行胸骨闭合,然后在第3周结束时进行第二阶段的软组织闭合(图4)。一名患者存在肺炎克雷伯菌。本组也无死亡病例。

图4.负压伤口治疗(NPWT)后两阶段闭合的胸骨深部伤口

所有患者均接受了小儿重症监护治疗,包括日常体液平衡、合并症护理、贫血护理、营养补充和压力性损伤的预防。此外,在手术过程中给予吸氧、镇痛和全身麻醉。在所有关键时刻,都对其家属进行了教育和讨论。

讨论

处理儿童心脏手术后胸骨伤口的最佳方法是预防感染和对患者进行整体护理,同时考虑所有干扰患者护理和结果的临床因素。2通常情况下,CDC指南用于诊断胸骨伤口感染。9这包括手术后症状或体征出现的时间(30天内)以及出现脓液或微生物培养结果呈阳性。此外,如果外科医生因怀疑有感染性肿胀而必须重新打开切口部位,则应考虑是否存在疼痛、触痛、发热或红斑。9临床医生必须意识到,在儿科人群中,最初可能只有伤口开裂,但在适当的时候,可能会因其他情况而复杂化。皮肤状况不佳、年龄、早产、染色体异常、复杂的手术操作、重复手术和灌注不良是导致伤口开裂的一些常见原因。因此,循证的系统性伤口护理方法,包括伤口床准备原则、先进的伤口护理疗法,以及使用适合患者的适当手术方法以实现早期康复,对于胸骨伤口开裂的弱势人群来说是理想的选择。4

现有文献中缺乏关于儿科人群(尤其是接受复杂心脏外科手术的儿童)最佳胸骨伤口管理(感染或未感染)的信息。4因此,这些初步的观察以及提出的管理策略可能有助于改善结果,并鼓励其他外科遵循类似的实践。此外,在缺乏CDC手术部位感染标准的情况下,根据经过验证的NERDS和STONEES标准,从组织开裂开始对伤口进行评估,不仅有助于在早期发现局部严重定植或深部感染的迹象,而且可以利用伤口床准备的方法阻止这一过程。

胸骨伤口管理中最重要因素是预防或识别感染。感染与高死亡率、住院时间延长和高昂的治疗费用相关。1,3,10一项关于使用NERDS和STONEES评估成人一般人群伤口细菌负荷的横断面验证研究得出结论,当临床专家使用任何三个标准时,都能提供关于伤口中细菌数量的敏感性、特异性信息。5,6 Woo和Sibbald6进行的具有里程碑意义的研究证实,通过整理被评估伤口中表现出的任何三个临床症状,NERDS的敏感性増加到73.3%(特异性80.5%),STONEES的敏感性増加到90%(特异性69.4%)。因此,在初步评估任何胸骨伤口时,了解NERDS和STONEES标准至关重要,并且可能有助于识别严重的定植或局部感染。这一部分被纳入提出的伤口护理路径中,作为尽早预防或治疗的第一步。

作者发现本单位在伤口护理知识方面存在不足。当血培养结果呈阳性或存在三项STONEES指标时,就使用全身性抗生素。此外,许多患者在重症监护期间有合并症、先天性畸形、侵入性操作或导管,需要使用全身抗生素。

下一步包括考虑伤口床准备原则(包括以患者为中心的问题)的整体伤口评估。根据伤口情况采用清创、清洁和敷料材料,并纠正合并症,如疼痛处理。这有助于对伤口进行分层,评估对治疗的反应,并在适当的先进疗法的需求和时机进一步规划伤口管理。

在管理路径的最后部分,考虑并实施了包括外科手术在内的先进技术的作用,这有助于加快伤口愈合。

胸骨区域几乎没有肌肉或软组织覆盖,因此该区域没有充足的血液供应。1,2,4,9此外,骨骼与皮肤的距离很近,容易使浅表感染进入深部组织。由于持续的呼吸运动,该区域承受着更高的压力。9所有这些因素不仅使胸骨伤口难以愈合,而且证明在早期使用先进的治疗或手术具有合理性。3在这些策略中,NPWT已被证明可以成功用于小儿心脏手术患者。11

因此,提出的策略建议在早期阶段进行NPWT,以保持局部干燥和相对稳定,促进愈合。NPWT可刺激血流、肉芽组织并减轻炎症反应。此外,它还通过对抗摩擦和由此产生的炎症来保持水分平衡。它还有助于加快愈合速度,减少换药次数和人力,同时可能影响住院时间和费用。1,4,8,10,11每周应用两次NPWT是基于以下假设:保持伤口干燥,更频繁地评估伤口情况从而在早期进行清创或闭合,减少恢复时间,以实现与住院、成本和后勤有关的整体效益。在某些情况下,对于深部感染或潮湿的伤口,换药的需求可能是不固定的,而且很频繁。

在儿童中,具有未来生长潜力的柔软和脆弱组织限制了侵入性手术方案的实施。1,2,4因此,建议采用限制胸大肌前移和分阶段的胸骨闭合来直接闭合软组织。手术在这一决策中的作用取决于伤口床的性质、是否存在感染、胸骨活动度和伤口的深度。对于胸骨不稳定的深部伤口中,胸骨闭合被认为是一阶段闭合(一旦达到健康、可愈合的组织状态,所有的层都会闭合)。然而,如果出现较难愈合的伤口,则首先尝试进行胸骨闭合,以保护纵隔组织并提供稳定性。发现表层健康后,就进行第二阶段的软组织闭合(两阶段闭合)。这种分期有助于减少壁张力和进一步开裂的风险。

在所有患者中,根据培养结果和药敏结果使用抗生素,或者在看到局部或全身感染的迹象时,根据经验使用抗生素。此外,还通过跨专业方法提供合并症治疗、营养支持和家长咨询。

通过提出的伤口护理路径和教育,研究人员不仅提高了知识水平,还在国家卓越中心引入了伤口护理实践。作者制定了一项策略,对家长进行教育,让其了解与儿童心脏手术相关问题的预防、护理和管理,如切口疼痛、感染、伤口、康复和心理支持,这有助于对儿童心脏手术患者进行全面护理。

局限性

本项目仅限于引入伤口护理路径,改变实践只是第一步。少量案例被记录为观察结果或案例研究。理想情况下,这些工具应该针对更多的患者群体进行长期分析。此外,还介绍了红外测温仪的作用,但并未统一使用,因为它是作者单位新増加的设备,而且与比较肢体温度不同,很难比较胸部两个相同部位的温度。因此,作者比较了胸骨区和腹壁的温度作为替代方案,但没有评估这些结果的可靠度。

结论

通过基于跨专业护理理念的标准化管理路径,结合循证指南和伤口护理范式的组成部分,可以简化儿科人群心脏手术后胸骨伤口的管理。这将有助于避免个人偏好以及治疗单位的实践,以比较长期结果的有效性和改善。此外,在早期实施NPWT和适当使用外科手术可以加速儿童术后胸骨伤口的愈合,为患者和组织带来综合效益。需要进行长期研究,以观察所提出的概念和管理途径的实际影响。

致谢

作者感谢医学博士、内科执业医生Emadullah Raidullah,医学博士、内科专家Atiq Ur Rehman,科室护士Beji George女士以及单位的整个伤口护理团队在患者管理和图表及稿件准备方面的帮助。本研究作为2021年阿布扎比国际跨专业伤口护理课程(IIWCC)的选修项目进行。作者感谢IIWCC的教员及其同事提供的建设性意见、评估和指导。本论文提供了补充性数字化内容。直接URL引用见印刷文本,并在期刊网站(www.ASWCjournal.com)上本文的HTML和PDF版本中提供。

利益冲突声明

作者声明无利益冲突。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Neerod Kumar

Jha, MD

Pediatric Cardiac Surgeon, Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Muhammad Shafique

MD

Specialist, Internal Medicine, Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Raisy Thomas

BSc

Clinical Nurse Educator, Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Salvacion Pangilinan Cruz

MSc

Charge Nurse, Wound Care, Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Gulnaz Tariq

MSc

Nursing Officer, Wound Care Department, Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Laszlo Kiraly

MD

Pediatric Cardiac Surgeon, Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

* Corresponding author

References

- Shi YD, Qi FZ, Zhang Y. Treatment of sternal wound infections after open-heart surgery. Asian J Surg 2014;37:24-9.

- Woodward CS, Son M, Calhoon J, Michalek J, Husain SA. Sternal wound infections in pediatric congenital cardiac surgery: a survey of incidence and preventive practice. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:799-804.

- Choukairi F, Ring J, Thekkudan J, Enoch S. Management of sternal wound dehiscence. Wounds UK 2011;7(1):99-105.

- Rupprecht L, Schmid C. Deep sternal wound complications: an overview of old and new therapeutic options. Open J Cardiovasc Surg 2013;6:9-19.

- Woo KY, Sibbald RG. A cross-sectional validation study of using NERDS and STONEES to assess bacterial burden. Ostomy Wound Manage 2009;55(8):40-8.

- Sibbald RG, Goodman L, Reneeka P. Wound bed preparation 2012. J Cutaneous Med Surg 2013;17(4) Suppl:S12-S22.

- Arger J, Dantas DC, Arnoni RT, Farsky PS. A new classification of post-sternotomy dehiscence. Braz J Cardiovas Surg 2015;30(1):114-8.

- Sjogren J, Malmsjo M, Gustafsson R, Ingemansson R. Post sternotomy mediastinitis: a review of conventional surgical treatments, vacuum-assisted closure therapy and presentation of the Lund University Hospital mediastinitis algorithm. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg 2006;30(6):898-905.

- National Healthcare Safety Network. Surgical Site Infection (SSI) Event. January 2022. www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf. Last accessed September 21, 2022.

- Lindholm C, Searle R. Wound management for the 21st century: combination of effectiveness and efficiency. Int Wound J 2016;13 (suppl.S2):5-15.

- Gilod S, Orit SM, Gilat L, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure for the treatment of deep sternal wound infection after pediatric cardiac surgery. Ped Crit Care Med 2020;21(2):150-5.

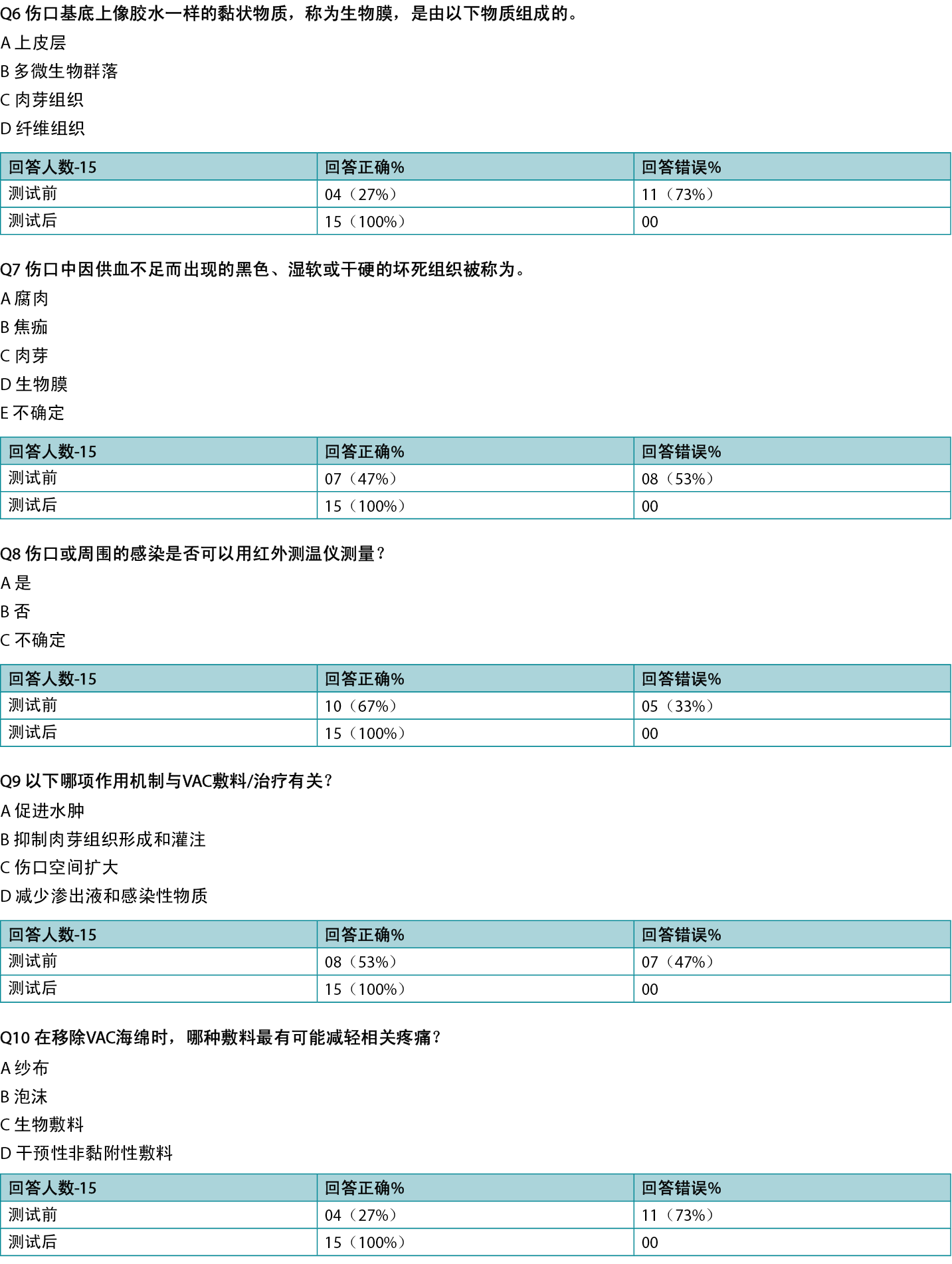

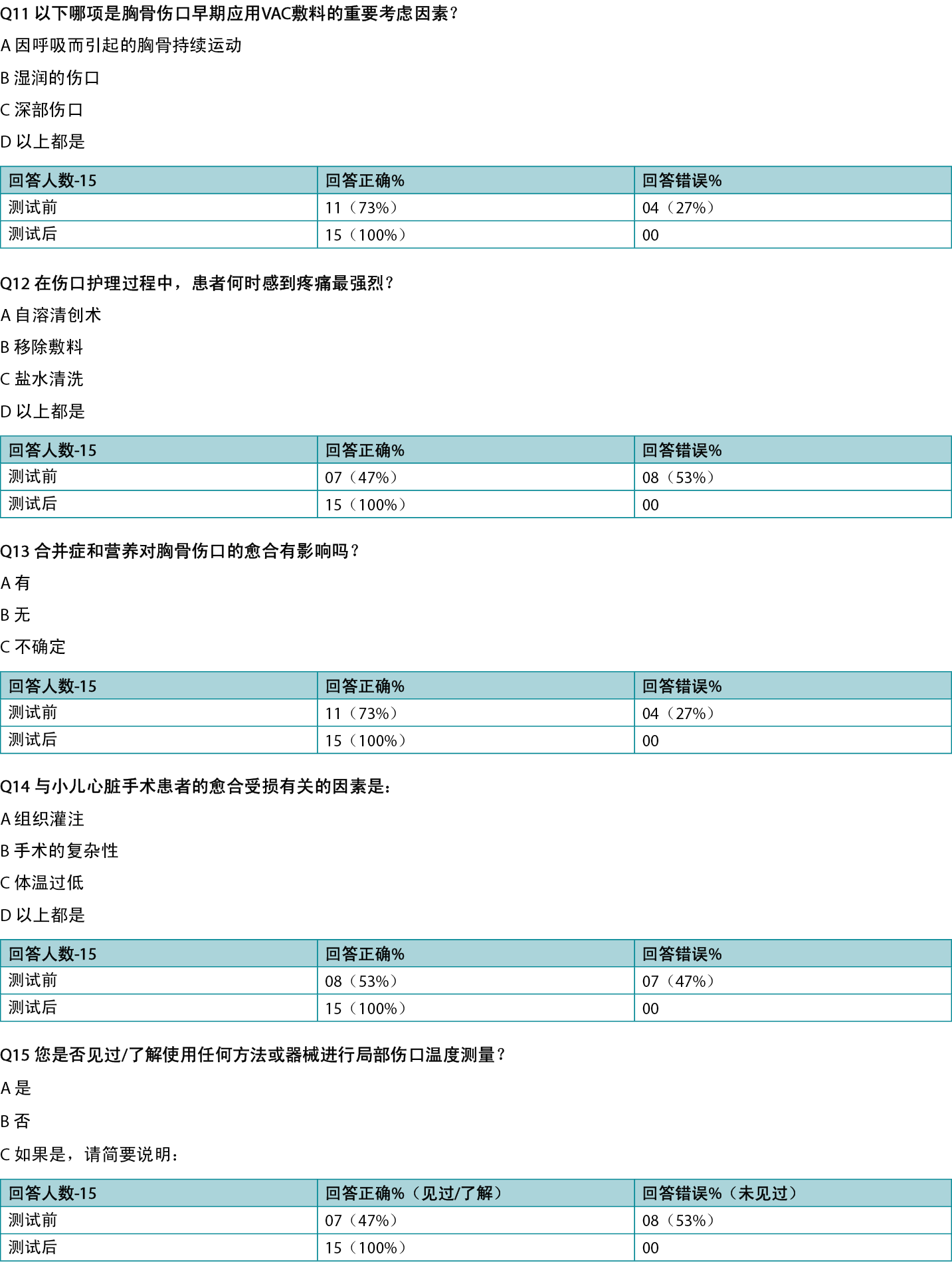

Supplemental Table

Assessment of knowledge and practice on wound care including sternal wounds in the nursing staff (before/after introduction of proposed guidelines and sternal wound care pathways)