Volume 43 Number 2

WHAM evidence summary: sugar dressing for wound healing and treating wound infection in resource limited settings

Emily Haesler

Keywords Traditional wound management, sugar dressing, sugar paste

For referencing Haesler E. WHAM evidence summary: sugar dressing for wound healing and treating wound infection in resource limited settings . WCET® Journal 2023;43(2):35-40

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.2.35-40

Clinical question

What is the best available evidence for sugar dressing improving wound healing and for reducing signs and symptoms of wound infection?

Summary

Granular/crystalized white sugar is readily accessible at low cost in most geographic regions. It has been used as a wound treatment for hundreds of years because it is sterile, non-toxic, absorbs fluid and has some antimicrobial properties1. Sugar is most often used in its granular form, packed into a wound cavity and secured with a wound dressing. Alternatively, it is ground into a powder, combined with glycerine or petroleum jelly and applied as a paste1, 2. There was no evidence comparing the effectiveness of sugar to modern dressings that promote moist wound healing. Level 1 evidence3, 4 at high risk of bias showed sugar dressing was associated with acceptable wound healing rates3, 4 and reduction in wound infection4, but might not be as effective as Edinburgh University Solution of Lime (EUSOL)3 or honey4, which are both commonly used in settings with limited resources. Level 35-7 and 48-15 evidence at moderate or high risk of bias provided evidence that sugar dressing might promote healing5, 6, 8, 9, 11-15, improve the wound bed tissue5, 9, 13-15, and reduce bacterial infection6, 12-15, wound pain5, and wound malodour7, 10.

Clinical practice recommendations

All recommendations should be applied with consideration to the wound, the person, the health professional and the clinical context.

|

Sugar dressing could be considered for use as a natural wound dressing to reduce signs and symptoms of infection and to promote healing when there is limited access to modern wound dressings (Grade B). |

Sources of evidence: search and appraisal

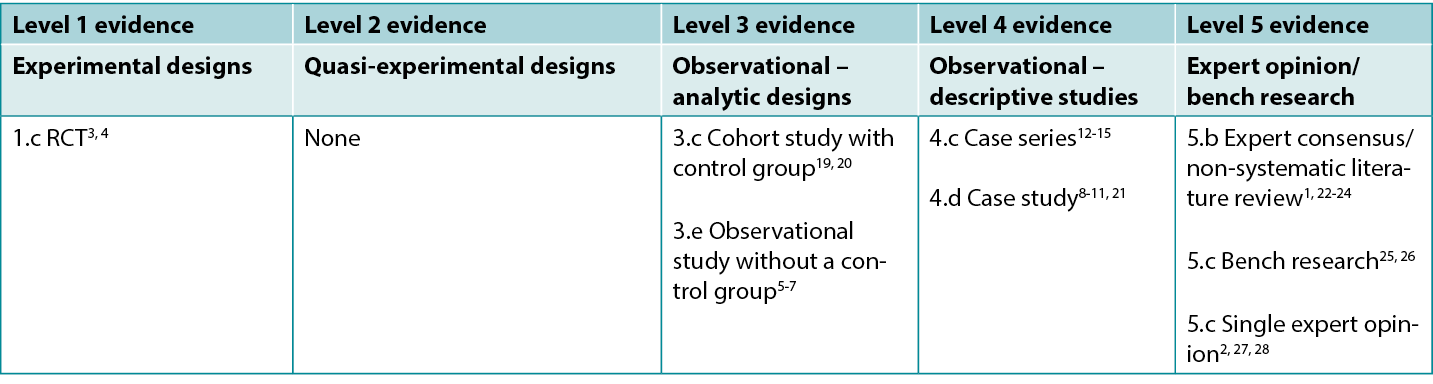

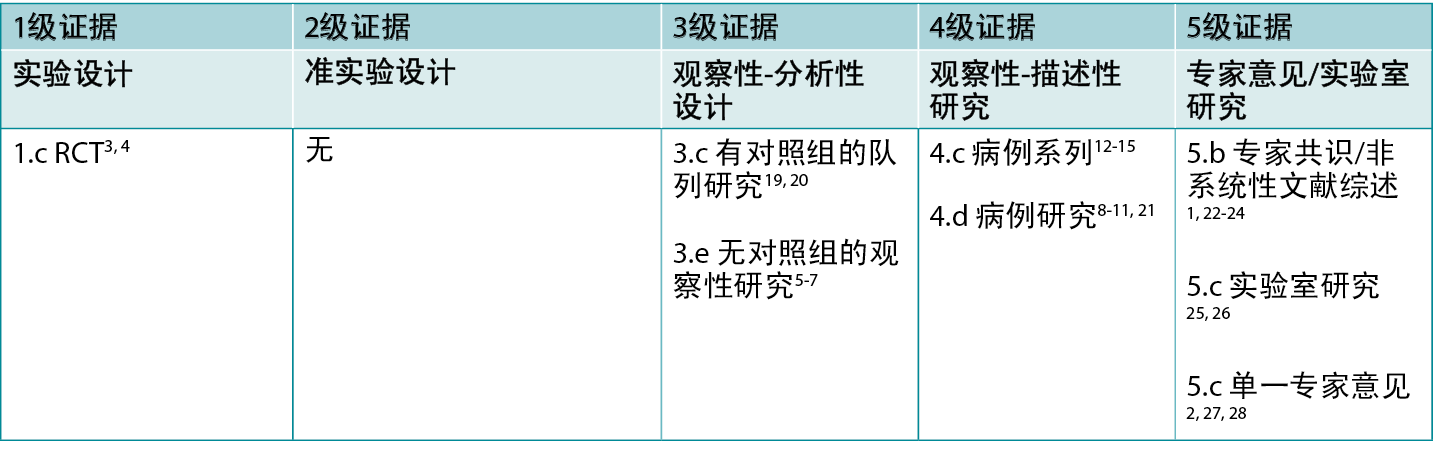

This summary was conducted using methods published by the Joanna Briggs Institute16-18. The summary is based on a systematic literature search combining search terms related to sugar dressing and wound healing. Searches were conducted for evidence reporting use of granulated sugar in human wounds published up to December 2022 in English in the following databases: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medline (Ovid), Google Scholar, Embase (Ovid), AMED and Health Internetwork Access to Research Initiative (Hinari, access via Research4Life) and Cochrane Library. Studies on other sugar sources (e.g., honey) or sugar combined with povidone-iodine (Knutson’s formula) were not eligible for inclusion (excepting when reported as a comparator). Levels of evidence for intervention studies are reported in Table 1.

Table 1: Levels of evidence for clinical studies

Background

Sugar has been used since the late 1600s as a wound cleanser and the early 1700s as a treatment to promote wound healing1, 22. It is readily accessible at a very low cost in most geographic regions. In its granular/crystalized form, sugar consists of glucose and fructose, bound together to form sucrose (a disaccharide)13, 26. Sugar is present as a monosaccharide in other natural treatments, including honey, saps and fruit22. In its crystalized form, sugar’s mechanism for wound healing is different than that of honey and fruits. Crystalized sugar is sometimes used in combination with povidone-iodine to treat wounds29-33, and is commercially marketed as a sugar-povidone-iodine paste in some countries. The evidence for sugar in other natural forms (e.g., honey) and in combination with povidone iodine is not reported in this evidence summary, excepting as a comparator to sugar dressing.

There are several mechanisms through which granular white sugar is presumed to promote wound healing. First, sugar is hygroscopic; that is, it absorbs moisture from the environment around it, contributing to reduction in wound exudate22, 28. This also leads to mechanical debridement through slough adherence to the sugar dressing for removal without damage to healthy tissue1, 3, 22. In addition, sugar’s hygroscopic property contributes to autolytic debridement13, and reduction of edema in the wound bed and surrounding tissues1, 13.

Sugar increases osmolality of the wound environment, which influences water level activity. This mechanism attracts lymphocytes and macrophages to the wound bed1, and can inhibit the growth of bacteria5, 7, 25, 26. Sugar also releases hydrogen peroxide at low, non-toxic levels, which further inhibits bacteria activity7, 13, 27. Invitro studies have demonstrated sugar’s activity against a range of bacteria, including S. aureus, P aeruginosa, S. faecalis, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and C. albicans5, 8, 25; and this was supported in an in-vivo study reported below4. In comparison to many other antiseptics, sugar has low toxicity and lowers the wound bed pH to around 5.0, which is more conducive to healing than an alkaline pH1, 7.

Clinical evidence on sugar dressing

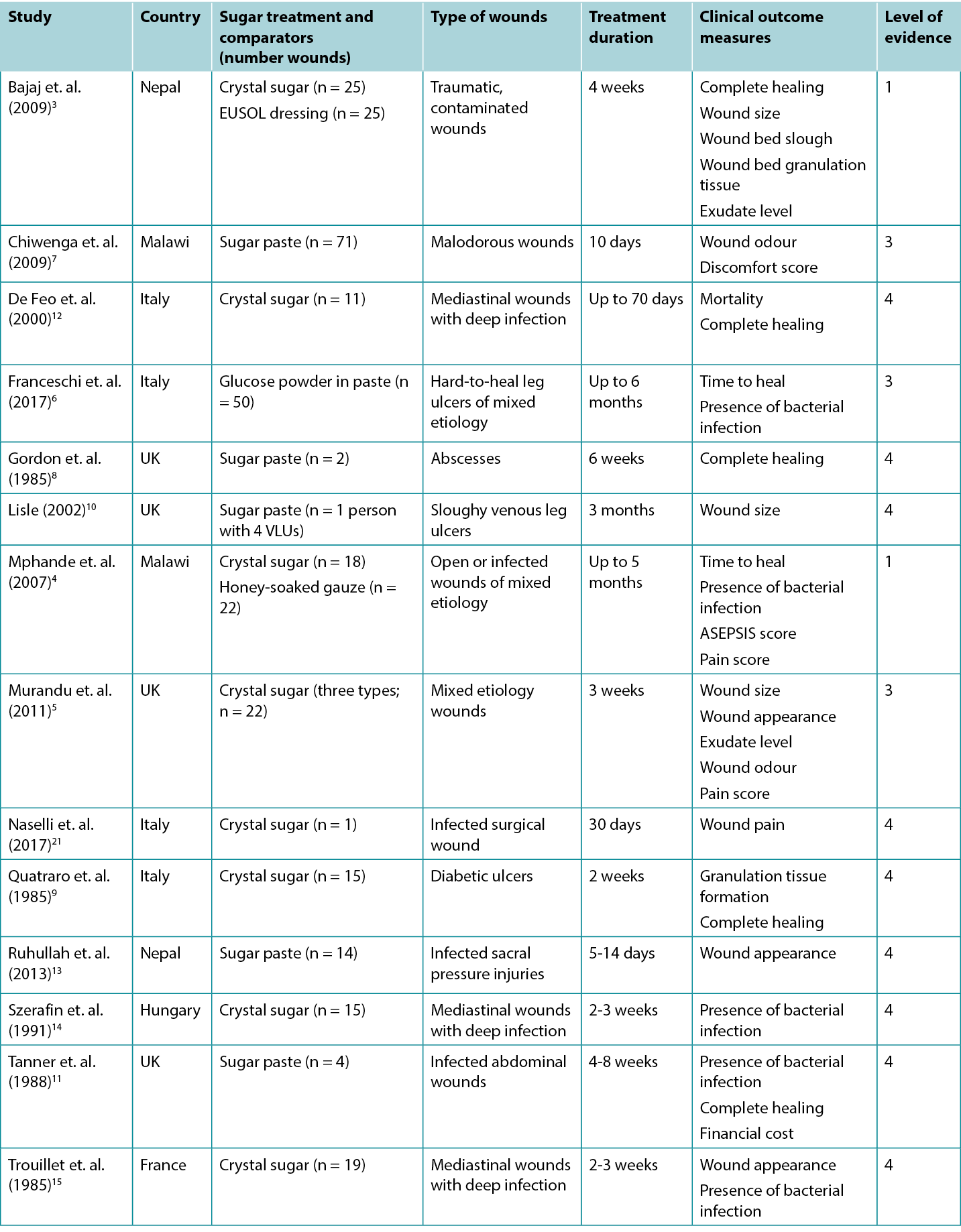

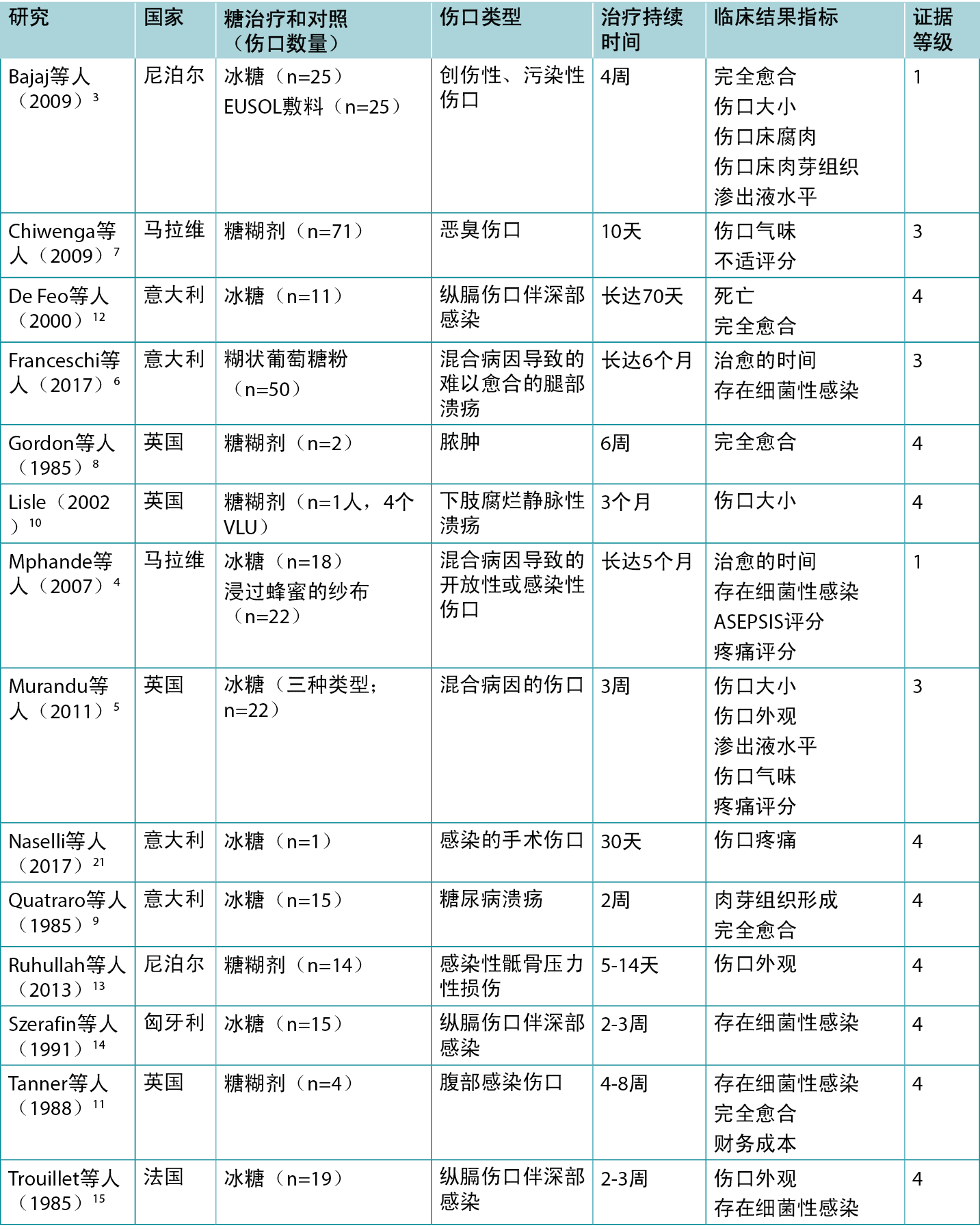

Studies reporting clinical outcomes for treatment with sugar dressings are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Summary of the evidence for traditional sugar dressing/paste

Sugar dressing for promoting wound healing

An RCT3 (n = 50 wounds) that was at high risk of bias compared sugar dressing to EUSOL dressing for treating traumatic, contaminated wounds associated with bone injuries. EUSOL is a traditional hypolochlorite made from chlorinated lime and boric acid34. In both groups the wounds were lavaged with normal saline. The sugar group received granulated white sugar plus a gauze dressing. The EUSOL group received a 30-minute EUSOL soak followed by packing with EUSOL gauze. Both groups received concurrent systemic antibiotics based on culture and sensitivity of organisms in the wounds. After four weeks both groups had good healing rates, but the EUSOL group showed superiority (77% healed versus 66% healed, p < 0.05). The EUSOL group had a 1.23 times higher likelihood of achieving healing within four weeks. The EUSOL group also had superior outcomes on other measures including wound size and wound bed tissue type3 (Level 1).

A second RCT4 (n = 40) that was at high risk of bias compared sugar dressing to a honey dressing in open or infected wounds in children and adults. Debris was removed using saline and gauze, then wounds were either packed with granulated sugar or with honey-soaked gauze. Dressings were initially performed daily, increasing to weekly based on wound condition. After two weeks of treatment, the median healing rate was higher in the honey group (3.8 cm2/week versus 2.2 cm2/week, p = not reported). Median time to complete healing was shorter in the honey group (31.5 days [range 14 – 98] versus 56 days [range 21 – 133]). Both treatments were considered effective. Honey was reported as superior; however, no statistical analysis was reported to support this conclusion4 (Level 1).

In a proof-of-concept study at high risk of bias5, 22 wounds of mixed etiology were treated with a sugar dressing for three weeks. At baseline, the wounds had sloughy/necrotic tissue and moderate to heavy exudate levels. Wounds were cleansed, packed with granulated sugar and an absorbent pad applied, either daily or twice daily. There was progressive improvement in wound bed appearance for all the wounds over the short study period, and a reduction in mean wound area (baseline mean: 34.7 cm2 [range 6–144]; 3-week mean: 28.9 cm2 (range 4.63 – 142.4])5 (Level 3).

Several case studies8-11 at high risk of bias reported successful healing of hard-to-heal wounds with various sugar preparations. In one8, two people with complex abscesses that had previously failed to heal with surgical debridement and EUSOL gauze packing achieved complete healing within six weeks of commencing treatment with sugar paste (powdered sugar combined with polyethylene glycol and hydrogen peroxide)8. Quatraro et. al. (1985)9 reported that packing diabetic ulcers (n = 15) with sugar replaced every 3 to 4 hours was associated with rapid wound bed granulation (5 to 6 days) and complete healing within 12 days9. Another case report10 described the use of sugar paste replaced daily to reduce wound malodour and heal multiple, sloughy, partial thickness leg ulcers in one person. Finally, Tanner et. al. (1988)11 reported four cases in which sugar paste was applied to infected abdominal wounds to achieve healing within 4 to 8 weeks. In this report, thicker sugar paste was applied directly to open wound beds, and a thinner sugar paste (with increased volume of polyethylene glycol and hydrogen peroxide) was installed into abscess cavities with a syringe and catheter11 (Level 4).

Sugar dressing for signs and symptoms of wound infection

In an observational study6 (n = 50) at high risk of bias, hard-to-heal leg ulcers were selected for trial of a 60% sugar powder and 40% petroleum jelly paste preparation. At baseline, wound swabs were taken, with results showing bacterial presence in 100% of ulcers. Treatment was wound cleansing with tap water (no debridement performed), weekly application of the sugar paste, bandaging and etiological-based management (e.g., compression therapy or conservative hemodynamic correction of venous insufficiency [CHIVA]). A second wound swab was performed at 30 to 40 days; 100% of ulcers were bacteria-free. Complete healing rate was 96%, with a mean healing time of 109 days6 (Level 3).

Another observational study7 (n = 71) at high risk of bias explored sugar paste to manage wound odour and pain. Malodorous wounds selected for treatment had a mean baseline odour score of 5.45 that reduced to 2.94 at ten days of treatment (score rated from 1 to 10, where 10 was worst odour). Patient-rated discomfort reduced from a mean of 6.73 to 3.87 (score from 1 to 10, where 10 was worst pain)7 (Level 3).

A case series12 (n = 11) at high risk of bias reported outcomes for mediastinal wound infection following cardiac surgery when treated with sugar dressing. On detection of wound infection, surgical exploration, debridement and povidone iodine irrigation were performed, and the wound was surgically closed. However, wound infection did not resolve for any participants. The sternal wound was re-opened, and sugar dressing was performed up to four times daily until complete healing or flap reconstruction. Mean time to resolution of infection (based on microbiological assessment) after sugar dressing commenced was 11.22 ± 1.6 days. Mean duration of sugar dressing was 44 ± 27.8 days12 (Level 4). In a later report19, 20 at moderate risk of bias, the researchers compared this cohort to two other cohorts with mediastinal wound infection following cardiac surgery that received different treatments based on a range of standardized protocols at the time of their admission. Mortality rates were significantly better for sugar dressing versus conservative treatment/closed irrigation (30.6% versus 2.4%, p < 0.05), but mortality was higher for people treated with sugar dressing versus negative pressure wound therapy (1.8% versus 2.4%, p < 0.05)19. However, all the people in this study were critically ill and it was not evident that the type of dressing influenced mortality outcomes (Level 3). Other small case series at high risk of bias13-15 achieved similar clinical outcomes in both surgical wounds14, 15 and chronic wounds13 using sugar dressing14, 15 or paste13 to resolve local wound infection, debride the wound bed and promote granulation in preparation for surgical repair (Level 4).

The RCT4 comparing sugar to honey dressings evaluated signs and symptoms of infection with microbiological assessment, ASEPSIS score and pain assessment (categorically described as no pain, moderate pain or severe pain). Both groups showed similar reduction in signs and symptoms of wound infection. After one week of treatment, the percent of wounds treated with sugar that returned positive cultures reduced from baseline (52% to 39%). The median ASEPSIS score for sugar-treated wounds showed a reduction in the first three weeks (8.3 points/week) and the percent of people describing severe pain during dressing changes or with movement also reduced4 (Level 1).

In the short proof-of-concept study described above, Murandu et. al. (2011)5 reported resolution of signs and symptoms of infection (i.e., exudate, malodour and wound pain). Malodour completely resolved by seven days of treatment in all 11 wounds that were assessed as malodorous at baseline. All 22 wounds had moderate-to-heavy exudate levels at baseline; exudate decreased in the first week and was absent or minimal for all wounds by trial end. Pain requiring opiates was reported by five people at baseline, and this resolved within three days of treatment5 (Level 3).

Considerations for use

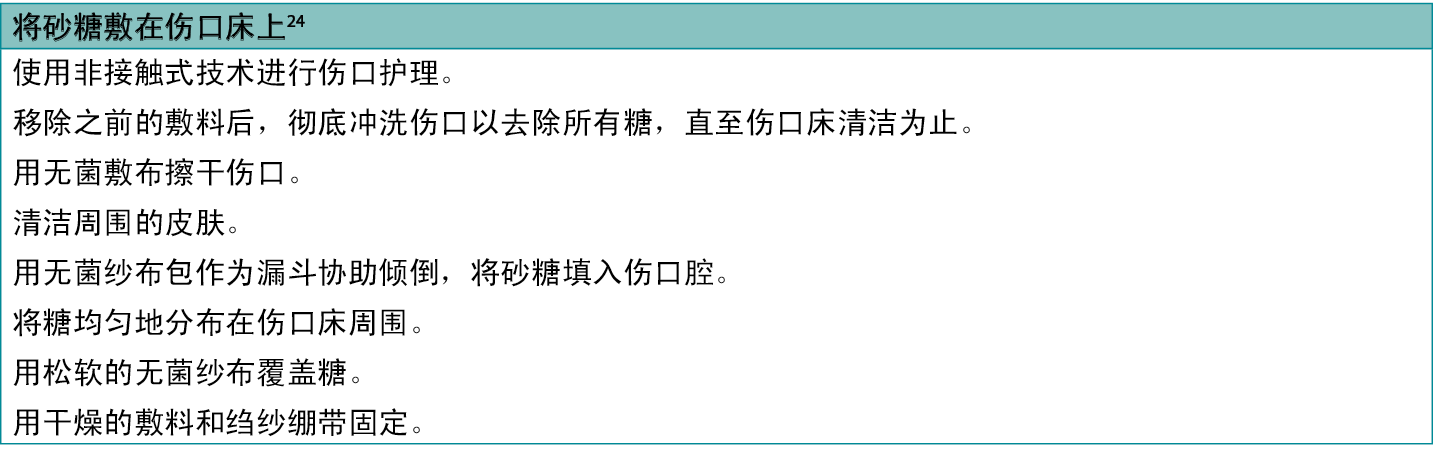

Preparation and use of sugar dressing

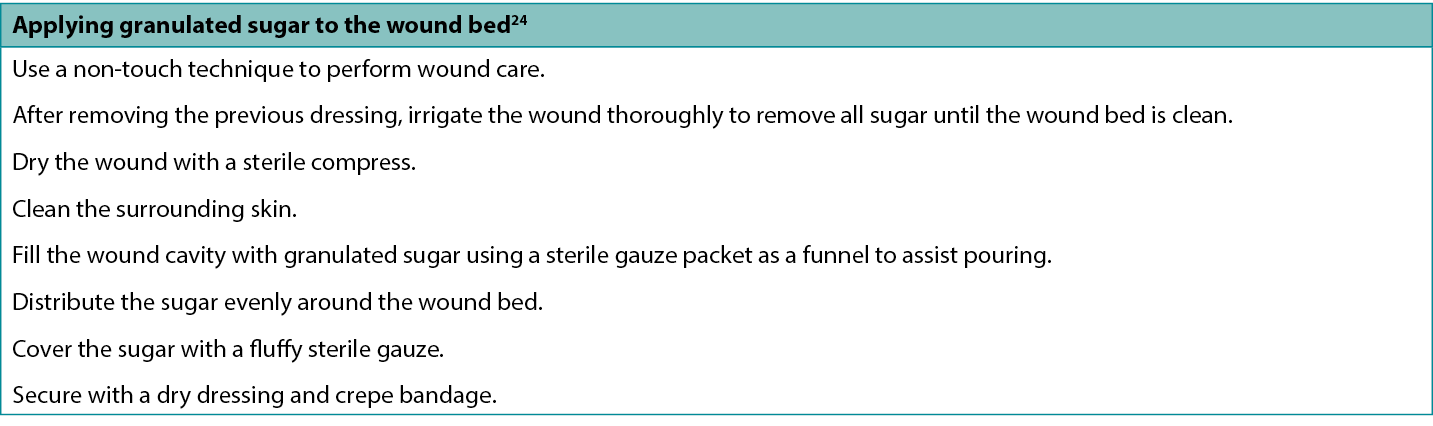

The studies included in this evidence summary used various methods to apply sugar to the wound. Some researchers5, 9, 15 packed granular white sugar directly into the wound cavity and retained it with gauze, absorbent pad, dry gauze or adhesive dressing (see Table 3 for an example of a recommended application method24). Muranda et. al. (2011)5 described using yellow paraffin to build a ‘ridge’ around wounds in awkward anatomical locations (e.g., heels) to further assist in retaining sugar in the wound. In these studies, packing sugar directly into the wound required replacement of the sugar dressing at least twice daily to maintain a well-packed wound cavity5, 9, 15, because sugar combines with wound exudate and drains from the wound7. Other researchers describe the addition of glycerin or petroleum jelly to make a sugar paste that could more easily be retained in the wound6-8, 13 and had a consistency that eased application7.

Table 3: One method for applying sugar to a wound

Adverse effects

- Some people reported a burning pain on application of sugar dressing that resolved quickly5, 7. Sugar has also been reported to cause itching of the peri-wound skin.24 These effects are thought to occur due to the drying effect sugar has on the wound bed and might be reduced by using a sugar paste in preference to granular sugar28.

- Evidence on the effect of topically applied sugar on blood sugar levels in people with diabetes is mixed. Sugar is a disaccharide (i.e., glucose and fructose combine to form sucrose) that is absorbed through the intestines, so theoretically it should not influence blood sugar levels when applied to a wound bed1, 23, 35. Some studies explored and confirmed that applying sugar to a wound does not influence blood sugar levels5, 15; however, there was one case report in which raised blood sugar level was observed1, 22, and in another study people with diabetes were given higher insulin doses20.

- There is one report of acute kidney failure associated with sugar paste23. In some of the reports12, 14, 15, people who had a wound treated with sugar dressing died; however, these people had serious disease and death was likely not related to the sugar dressing.

Other considerations

- White granulated sugar is considered sterile. Care should be taken to guarantee the product used is not contaminated and that sterility is maintained (e.g., if powdering the sugar).

- The evidence in this summary came from settings with limited access to wound care resources. Consider the medico-legal implications of using a sugar dressing in resource-rich settings.

- Optimal frequency of sugar dressing replacements is twice daily7, 13, 21, 26 to maintain sufficient osmolality and hydrogen peroxide production to sustain inhibition of bacteria22, 27. However, this is rarely possible in resource-limited settings7. Numerous studies reported wound dressing frequencies of up to 5 to 7 days4, 6, 7, 13, particularly after wound exudate reduces.

- Patient and health practitioner satisfaction levels were reported to be high in one study, and in this study feasibility of people performing their own sugar dressing in the community was demonstrated5.

- Sugar is reported to have a lower attraction to flies than honey, which may be a consideration when selecting a wound dressing in resource-limited settings28.

- Sugar paste was prepared by a hospital pharmacy from by using powdered, additive-free sugar combined with polyethylene glycol and hydrogen peroxide11, with ratio of ingredients varying based on the viscosity required for ease of application. Hydrogen peroxide is not recommended for use in cavity wounds and sterility might not be maintained when powdering the sugar.

- A cost comparison that considered cost of dressing materials and community nursing time for a four-month treatment regime in the 1980s in the UK reported a sugar paste dressing to be a cheaper option than gauze or paraffin gauze11.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest in accordance with International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) standards.

About WHAM evidence summaries

WHAM evidence summaries are consistent with methodology published in Munn Z, Lockwood C, Moola S. The development and use of evidence summaries for point of care information systems: A streamlined rapid review approach, Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2015;12(3):131-8.

Methods are outlined in resources published by the Joanna Briggs Institute16-18 and on the WHAM Collaborative website: http://WHAMwounds.com. WHAM evidence summaries undergo peer-review by an international, multidisciplinary Expert Reference Group. WHAM evidence summaries provide a summary of the best available evidence on specific topics and make suggestions that can be used to inform clinical practice. Evidence contained within this summary should be evaluated by appropriately trained professionals with expertise in wound prevention and management, and the evidence should be considered in the context of the individual, the professional, the clinical setting and other relevant clinical information.

Copyright © 2023 Wound Healing and Management Collaboration, Curtin Health Innovations Research Institute, Curtin University

证据总结:中低收入国家

Emily Haesler

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.2.35-40

临床问题

糖敷料改善伤口愈合和减少伤口感染体征和症状的最佳现有证据是什么?

概述

在大多数地理区域,颗粒/结晶白糖都很容易获得,并且价格低廉。数百年来,它一直被用作伤口治疗剂,因为它无菌、无毒、能吸收液体并有一定的抗菌特性1。糖最常以颗粒形式使用,填塞到伤口腔内,并用伤口敷料固定。另一种方法是将其磨成粉末,与甘油或凡士林混合,作为糊剂使用1, 2。尚无证据比较糖与现代敷料在促进湿润伤口愈合方面的有效性。具有较高偏倚风险的1级证据3, 4显示糖敷料与可接受的伤口愈合率3, 4和伤口感染减少4有关,但可能不如爱丁堡大学石灰溶液(EUSOL)3 或蜂蜜4有效,两者均常用于资源有限的环境。具有中度或高度偏倚风险的3级5-7和4级8-15证据提供了糖敷料可能会促进愈合5, 6, 8, 9, 11-15,改善伤口床组织5, 9, 13-15,并减少细菌性感染6, 12-15、伤口疼痛5和伤口恶臭7, 10的证据。

临床实践建议

采用任何建议时,应考虑伤口、患者、专业医护人员和临床环境。

| 在现代伤口敷料获取途径有限的情况下,可以考虑将糖敷料作为天然伤口敷料使用,以减少感染的体征和症状,促进伤口愈合(B级)。 |

证据来源检索和评价

本总结采用乔安娜·布里格斯研究所公布的方法进行16-18。本总结基于系统性文献检索,结合了与糖敷料和伤口愈合相关的检索词。在以下数据库中检索了截至2022年12月以英文报告的关于在人体伤口中使用砂糖的证据:护理与联合卫生文献累积索引(CINAHL)、Medline(Ovid)、谷歌学术、Embase(Ovid)、AMED和卫生互联网共享研究成果倡议(Hinari,通过Research4Life访问)和Cochrane图书馆。关于其他糖源(如蜂蜜)或糖与聚维酮碘(Knutson公式)结合的研究不符合纳入标准(作为对照物报告时除

外)。表1报告了干预研究的证据等级。

表1:临床研究的证据水平

背景

自17世纪晚期以来,糖一直被用作伤口清洁剂,并在18世纪初被用作促进伤口愈合的治疗方法1, 22。在大多数地理区域,它都很容易获得,并且价格低廉。颗粒/结晶形式的糖由葡萄糖和果糖组成,它们结合在一起形成蔗糖(一种双糖)13, 26。糖以单糖的形式存在于其他自然疗法中,包括蜂蜜、树汁和水果22。在其结晶形式下,糖的伤口愈合机制与蜂蜜和水果不同。结晶糖有时与聚维酮碘一起用于治疗伤口29-33,并在一些国家以糖-聚维酮碘糊剂的形式进行商业销售。除了作为糖敷料的对照外,其他天然形式的糖(如蜂蜜)以及与聚维酮碘结合的糖的证据未在本证据总结中报告。

据推测,颗粒白糖有多种机制可以促进伤口愈合。首先,糖具有吸湿性;也就是说,它可以从周围环境中吸收水分,有助于减少伤口渗出液22, 28。这也导致了机械性清创,通过粘附在糖敷料上,在不损害健康组织的情况下进行清除1, 3, 22。此外,糖的吸湿性能有助于自溶性清创13,并减少伤口床和周围组织的水肿1, 13。

糖会増加伤口环境的渗透压,从而影响水位活动。这一机制将淋巴细胞和巨噬细胞吸引到伤口床1,并能抑制细菌的生长5, 7, 25, 26。糖还会释放低水平、无毒水平的过氧化氢,从而进一步抑制细菌活性7, 13, 27。体外研究已经证明糖对一系列细菌具有活性,包括金黄色葡萄球菌、铜绿假单胞菌、粪链球菌、大肠杆菌、肺炎克雷伯菌和白色念珠菌5, 8, 25;下文报告的体内研究支持了这一点4。与其他许多抗菌剂相比,糖的毒性很低,并将伤口床的pH值降低至5.0左右,这比碱性的pH值更有利于伤口愈合1, 7。

关于糖敷料的临床证据

表2总结了报告糖敷料治疗的临床结果的研究。

表2:传统糖敷料/糊剂的证据总结

糖敷料用于促进伤口愈合

一项具有高偏倚风险的RCT3(n=50个伤口)在治疗与骨损伤相关的创伤性、污染性伤口方面,对糖敷料和EUSOL敷料进行了比较。EUSOL是一种传统的次氯酸盐,由氯化石灰和硼酸制成34。两组患者的伤口均使用生理盐水冲洗。糖组给予颗粒白糖和纱布包扎。EUSOL组接受30分钟的EUSOL浸泡,然后用EUSOL纱布填塞。根据伤口中微生物的培养和药敏结果,两组同时接受全身性抗生素治疗。四周后,两组都有良好的愈合率,但EUSOL组显示出优效性(77%愈合 vs 66%愈合,P<0.05)。EUSOL组在四周内实现愈合的可能性高出1.23倍。EUSOL组在其他指标上也取得了较好的结果,包括伤口大小和伤口床组织类型3(1级)。

具有高偏倚风险的第二项RCT4(n=40)在儿童和成人的开放性或感染性伤口中比较了糖敷料和蜂蜜敷料。使用生理盐水和纱布清除碎屑,然后用砂糖或浸过蜂蜜的纱布填塞伤口。最初每天更换敷料,根据伤口情况増加到每周一次。治疗两周后,蜂蜜组的中位愈合率更高(3.8 cm2/周 vs 2.2 cm2/周,p =未报告)。蜂蜜组完全愈合的中位时间更短(31.5天[范围14-98] vs 56天[范围21-133])。两种治疗方法均被认为有效。蜂蜜被报告具有优效性;然而,没有统计分析报告支持这一结论4(1级)。

在一项具有高偏倚风险的概念验证研究中5,22个混合病因的伤口接受了为期三周的糖敷料包扎治疗。在基线时,伤口有腐肉/坏死的组织和中度至重度渗出。每天或每天两次对伤口进行清洗,用砂糖填塞,并使用吸水垫。在短暂的研究期间,所有伤口的伤口床外观均得到逐步改善,平均伤口面积也有所减少(基线平均值:34.7 cm2[范围6-144];3周平均值:28.9 cm2(范围4.63-142.4])5(3级)。

几项具有高偏倚风险的病例研究8-11报告了用各种糖制剂成功治愈难以愈合的伤口。在其中一项研究中8,两名患有复杂脓肿的患者之前通过手术清创和EUSOL纱布填塞未能愈合,在开始使用糖糊剂(糖粉与聚乙二醇和过氧化氢混合)治疗的六周内实现了完全愈合8。Quatraro等人(1985)9报告说,用糖填塞糖尿病溃疡(n=15)并每3至4小时更换一次,与伤口床肉芽快速形成(5至6天)和12天内完全愈合有关9。另一份病例报告10描述了一个人使用糖糊剂并每天更换,以此减少伤口恶臭,并治愈了多处、腐烂、部分厚度的腿部溃疡。最后,Tanner等人(1988)11报告了4个病例,将糖糊剂敷在感染的腹部伤口上,在4到8周内实现了愈合。在该报告中,较厚的糖糊剂直接敷在开放性伤口床上,较薄的糖糊剂(増加了聚乙二醇和过氧化氢的量)用注射器和导管装入脓肿腔中11(4级)。

糖敷料用于治疗伤口感染的体征和症状

在一项具有高偏倚风险的观察性研究6(n=50)中,选择了难以愈合的腿部溃疡进行60%糖粉和40%凡士林糊剂试验。在基线时,采集了伤口拭子,结果显示100%的溃疡中存在细菌。治疗方法是用自来水清洁伤口(不进行清创),每周敷糖糊剂、包扎并进行基于病因的管理(例如,加压疗法或静脉功能不全的保守血液动力学矫正[CHIVA])。在30至40天时进行了第二次伤口拭子检查;100%的溃疡均没有细菌。完全愈合率为96%,平均愈合时间为109天6

(3级)。

另一项具有高偏倚风险的观察性研究7 (n=71)探讨了用糖糊剂处理伤口气味和疼痛的方法。被选中进行治疗的恶臭伤口的平均基线气味评分为5.45,在治疗10天后降至2.94(评分从1到10,其中10分为最严重的气味)。患者评价的不适感从平均6.73降至3.87(评分从1到10,其中10分为最严重的疼痛)7(3级)。

一项具有高偏倚风险的病例系列研究12 (n=11)报告了心脏手术后纵隔伤口感染使用糖敷料治疗的结果。发现伤口感染后,进行手术探查、清创和聚维酮碘冲洗,并通过手术闭合伤口。然而,任何受试者的伤口感染均未消退。重新打开胸骨伤口,每天进行最多四次糖敷料包扎,直至完全愈合或皮瓣重建。从开始使用糖敷料到感染消退的平均时间(基于微生物学评估)为11.22Å}1.6天。糖敷料包扎的平均时间为44Å}27.8天12(4级)。在后来的一份具有中等偏倚风险的报告中19, 20,研究人员将该队列与另外两个心脏手术后纵隔伤口感染的队列进行了比较,这两个队列在入院时根据一系列标准化方案接受了不同的治疗。糖敷料的死亡率数据显著优于保守治疗/封闭灌洗(30.6% vs 2.4%,P<0.05),但用糖敷料治疗的患者死亡率高于负压伤口治疗(1.8% vs 2.4%,P<0.05)19。然而,本研究中的所有患者均病情危重,敷料类型对死亡率结果的影响并不明显(3级)。其他具有高偏倚风险的小型病例系列研究13-15在手术伤口14, 15和慢性伤口13中取得了类似的临床结果,使用糖敷料14, 15或糊剂13来处理局部伤口感染、清创伤口床并促进肉芽形成,为手术修复做准备(4级)。

一项比较糖和蜂蜜敷料的RCT研究4评估了感染的体征和症状,包括微生物学评估、ASEPSIS评分和疼痛评估(分类描述为无痛、中度疼痛或严重疼痛)。两组伤口感染体征和症状的减轻程度相似。治疗一周后,用糖治疗的伤口中,培养物呈阳性的比例较基线有所下降(52%降至39%)。用糖处理的伤口的ASEPSIS评分中位数在前三周内有所下降(8.3分/周),在换药或运动时描述严重疼痛的人数比例也有所下降4(1级)。

在上述简短的概念验证研究中,Murandu等人(2011)5报告了感染体征和症状(即渗出液、恶臭和伤口疼痛)的消退。所有11个在基线时被评估为恶臭的伤口,经过7天的治疗,恶臭完全消失。所有22个伤口在基线时都有中度至重度渗出;渗出液在第一周减少,到试验结束时所有伤口均无渗出或渗出量很少。有5人在基线时报告需要服用阿片类药物的疼痛,治疗3天内得到缓解5(3级)。

使用注意事项

糖敷料的制备和使用

本证据总结中包含的研究使用了各种方法将糖敷在伤口上。一些研究人员5, 9, 15将颗粒状白糖直接装入伤口腔内,并用纱布、吸水垫、干纱布或粘性敷料进行保留(推荐应用方法的示例见表324)。Muranda等人(2011)5 描述了使用黄色石蜡在尴尬的解剖位置(如脚后跟)的伤口周围建立一个Åg脊Åh,以进一步帮助保留伤口中的糖。在这些研究中,将糖直接填塞到伤口需要每天至少更换两次糖敷料,以保持伤口腔填塞良好5, 9, 15,因为糖会与伤口渗出液结合并从伤口排出7。其他研究人员描述了添加甘油或凡士林来制成糖糊剂,可以更容易地保留在伤口中6-8, 13,

并具有易于使用的稠度7。

表3:将糖敷在伤口上的一种方法

不良反应

- 有些人报告说,使用糖敷料后会出现灼痛感,但很快就消退了5, 7。据报告,糖还会引起伤口周围皮肤瘙痒。24这些反应被认为是由于糖对伤口床的干燥作用而产生的,可以通过使用糖糊剂而不是颗粒状的糖来减少这种影响28。

- 关于外用糖对糖尿病患者血糖水平的影响,证据不一。糖是一种可通过肠道吸收的双糖(即葡萄糖和果糖结合形成蔗糖),因此理论上讲,将其应用于伤口床时,不会影响血糖水平1, 23, 35。一些研究探讨并证实,在伤口上使用糖并不影响血糖水平5, 15;但是,有一个病例报告观察到血糖水平升高1, 22,在另一项研究中,糖尿病患者接受了更高剂量的胰岛素20。

- 有一例与糖糊剂有关的急性肾衰竭报告23。在一些报告中12, 14, 15,用糖敷料填塞伤口的患者死亡;但是,这些患者有严重的疾病,死亡可能与糖敷料无关。

其他考虑因素

- 白砂糖被认为是无菌的。应注意保证所使用的产品不受污染,并保持无菌状态(例如,如果将糖制成粉末)。

- 本总结中的证据来自伤口护理资源可及性有限的环境。应考虑在资源丰富的环境中使用糖敷料的医学法律意义。

- 更换糖敷料的最佳频率是每天两次7, 13, 21, 26,从而保持足够的渗透压和过氧化氢的产生,以维持对细菌的抑制22, 27。然而,在资源有限的环境中,这一点几乎不可能实现7。众多研究报告称,伤口敷料包扎频率可间隔高达5至7天4, 6, 7, 13,特别是在伤口渗出液减少后。

- 在一项研究中,患者和医务人员的满意度很高,这项研究证明了人们在社区中自己进行糖敷料包扎的可行性5。

- 据报告,糖对苍蝇的吸引力比蜂蜜低,这可能是在资源有限的环境中选择伤口敷料时的一个考虑因素28。

- 医院药房通过使用粉末状、无添加剂的糖,结合聚乙二醇和过氧化氢11来制备糖糊剂,成分比例根据便于使用的粘度要求而变化。不建议在空腔伤口中使用过氧化氢,并且在将糖制成粉末时可能无法保持无菌状态。

- 20世纪80年代在英国进行的一项成本比较,考虑了四个月治疗方案的敷料成本和社区护理时间,报告称糖糊剂敷料比纱布或石蜡纱布更便宜11。

利益冲突

根据国际医学期刊编辑委员会(ICMJE)的标准,作者声明无利益冲突。

关于WHAM证据总结

WHAM证据总结采用的方法与以下文献中发表的方法一致:Munn Z, Lockwood C, Moola S. The development and use of evidence summaries for point of care information systems: A streamlined rapid review approach, Worldviews Evid Based Nurs.2015;12(3):131-8。

乔安娜·布里格斯研究所16-18和WHAM合作网站(http://WHAMwounds.com)发布的资源列出了这些方法。WHAM证据总结经过国际多学科专家参考小组的同行评审。WHAM证据总结提供了关于特定主题的最佳可用证据的总结,并提出了可用于指导临床实践的建议。本总结中包含的证据应由经过适当培训的具有伤口预防和管理专业知识的专业人士进行评价,并应根据个人、专业人士、临床环境以及其他相关临床信息考虑证据。

版权所有˝2023科廷大学科廷健康创新研究所伤口愈合和管理协作组织

Author(s)

Emily Haesler

PhD P Grad Dip Adv Nurs (Gerontics), BN, FWA

Adjunct Professor, Curtin University, Curtin Health Innovation Research Institute, Wound Healing and Management (WHAM) Collaborative

References

- Biswas A, Bharara M, Hurst C, Gruessner R, Armstrong D, Rilo H. Use of sugar on the healing of diabetic ulcers: A review. J Diabetes Sci Technol, 2010; 4: 1139 - 45.

- Bitter CC, Erickson TB. Management of burn injuries in the wilderness: Lessons from low-resource settings. Wilderness Environ Med, 2016; 27(4): 519-25.

- Bajaj G, Karn NK, Shrestha BP, Kumar P, Singh MP. A randomised controlled trial comparing EUSOL and sugar as dressing agents in the treatment of traumatic wounds. Tropical Doctor, 2009; 39(1): 1-3.

- Mphande AN, Killowe C, Phalira S, Jones HW, Harrison WJ. Effects of honey and sugar dressings on wound healing. J Wound Care, 2007; 16(7): 317-9.

- Murandu M, Webber M, Simms M, Dealey C. Use of granulated sugar therapy in the management of sloughy or necrotic wounds: A pilot study. J Wound Care, 2011; 20(5): 206-16.

- Franceschi C, Bricchi M, Delfrate R. Anti-infective effects of sugar-vaseline mixture on leg ulcers. Veins and Lymphatics, 2017; 6(2).

- Chiwenga S, Dowlen H, Mannion S. Audit of the use of sugar dressings for the control of wound odour at Lilongwe Central Hospital, Malawi. Tropical Doctor, 2009; 39(1): 20-2.

- Gordon H, Middleton K, Seal D, Sullens K. Sugar and wound healing. Lancet, 1985; 2(8456): 663-5.

- Quatraro A, Minei A, Donzella C, Caretta F, Consoli G, Giugliano D. Sugar and wound healing. Lancet, 1985; 2(8456): 665.

- Lisle J. Use of sugar in the treatment of infected leg ulcers. Br J Community Nurs, 2002; 7(6 Suppl): 40, 2, 4, 6.

- Tanner A, Owen E, Seal D. Successful treatment of chronically infected wounds with sugar paste. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 1988; 7(4): 524-5.

- De Feo M, Gregorio R, Renzulli A, Ismeno G, Romano GP, Cotrufo M. Treatment of recurrent postoperative mediastinitis with granulated sugar. J Cardiovasc Surg, 2000; 41(5): 715-9.

- Ruhullah M, Sanjay S, Singh H, Sinha K, Irshad M, Abhishek B, Kaushal S, Shambhu S. Experience with the use of sugar paste dressing followed by reconstruction of sacral pressure sore with V-Y flap: A reliable solution for a major problem. Medical Practice and Reviews 2013; 4(4): 23-6.

- Szerafin T, Vaszily M, Péterffy A. Granulated sugar treatment of severe mediastinitis after open-heart surgery. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 1991; 25(1): 77-80.

- Trouillet JL, Chastre J, Fagon JY, Pierre J, Domart Y, Gibert C. Use of granulated sugar in treatment of open mediastinitis after cardiac surgery. Lancet, 1985; 2(8448): 180-4.

- Aromataris E, Munn Z (editors). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017.

- Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. New JBI Grades of Recommendation. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute, 2013.

- The Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. Supporting Document for the Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation. www.joannabriggs.org: The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2014.

- De Feo M, Vicchio M, Santè P, Cerasuolo F, Nappi G. Evolution in the treatment of mediastinitis: single-center experience. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann, 2011; 19(1): 39-43.

- De Feo M, Gregorio R, Della Corte A, Marra C, Amarelli C, Renzulli A, Utili R, Cotrufo M. Deep sternal wound infection: the role of early debridement surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg, 2001; 19(6): 811-6.

- Naselli A, Accame L, P. B, Loy A, Bandettini R, Garaventa A, Alberighi O, Castagnola E. Granulated sugar for adjuvant treatment of surgical wound infection due to multi-drug-resistant pathogens in a child with sarcoma: a case report and literature review. Le Infezioni in Medicina, 2017; 4(35): 358-61.

- Pieper B, Caliri M. Nontraditional wound care: A review of the evidence for the use of sugar, papaya/papain, and fatty Aacids. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs, 2003; 30: 175–83.

- Valls L, Altisen M, Poblador R, Alvarez A, Biosca R. Sugar paste for treatment of decubital ulcers. J Pharm Technol, 1996; 12: 289 - 90.

- International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). ICRC Nursing Guideline 3: Sugar Dressing. IN: ICRC Nursing Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: ICRC; 2021.

- Chirife J, Herszage L, Joseph A, Kohn ES. In vitro study of bacterial growth inhibition in concentrated sugar solutions: microbiological basis for the use of sugar in treating infected wounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1983; 23(5): 766-73.

- Middleton KR, Seal DV. Development of a semi-synthetic sugar paste for promoting healing of Iinfected wounds. In: Wadström T, Eliasson I, Holder I, Ljungh Å, editors. Pathogenesis of Wound and Biomaterial-Associated Infections. London: Springer London; 1990. p. 159-62.

- Molan P, Cooper R. Honey and sugar as a dressing for wounds and ulcers Tropical Doctor, 2000; 30(4): 249-50.

- Tovey F. Honey and sugar as a dressing for wounds and ulcers. Tropical Doctor, 2000; 30: 1.

- Di Stadio A, Gambacorta V, Cristi MC, Ralli M, Pindozzi S, Tassi L, Greco A, Lomurno G, Giampietro R. The use of povidone-iodine and sugar solution in surgical wound dehiscence in the head and neck following radio-chemotherapy. Int Wound J, 2019; 16(4): 909-15.

- Knutson RA, Merbitz LA, Creekmore MA, Snipes HG. Use of sugar and povidone-iodine to enhance wound healing: five year’s experience. South Med J, 1981; 74(11): 1329-35.

- Nakao H, Yamazaki M, Tsuboi R, Ogawa H. Mixture of sugar and povidone - Iodine stimulates wound healing by activating keratinocytes and fibroblast functions. Arch Dermatol Res, 2006; 298(4): 175-82.

- Shimamoto Y, Shimamoto H, Fujihata H. Topical application of sugar and povidone-iodine in the management of decubitus ulcers in aged patients. Hiroshima Journal of Medical Sciences, 1986; 35(2): 167-9.

- Topham J. Sugar paste and povidone-iodine in the treatment of wounds. J Wound Care, 1996; 5(8): 364-5.

- Haesler E, Carville K. WHAM evidence summary: traditional hypochlorite solutions. WCET® Journal, 2023; 43(1): 35-40.

- Bogdanov S, Jurendic T, Sieber R, Gallmann P. Honey for nutrition and health: a review. J Am Coll Nutr, 2008; 27(6): 677-89.