Volume 43 Number 4

Patients’ experience in the unnecessary use of absorbent continence products: a small experiential qualitative study

Sandra Guerrero Gamboa, Angie Viviana Ariza Garzón

Keywords nursing, incontinence diapers, absorbent pads, life changing events, psychological wellbeing

For referencing Guerro Gamboa S & Ariza Garzón AV. Patients’ experience in the unnecessary use of absorbent continence products: a small experiential qualitative study. WCET® Journal 2023;43(4):13-19.

DOI

10.33235/wcet.43.4.13-19

Submitted 12 June 2023

Accepted 25 September 2023

Abstract

Objective To describe the lived experience of a small group of inpatients arising from the unnecessary use of absorbent continence products in a hospital in Bogotá, Colombia.

Method A qualitative and phenomenological study. Interviews were undertaken with consenting participants as well as participant observations until data saturation occurred. Subsequently, all data were transcribed and analysed based on Husserl’s Methodology to derive themes and categories of the phenomenon seen.

Subjects and setting A selective sample of seven continent people without previous use of absorbent continence products and with mild disability, according to the PULSES profile, were recruited from the internal medicine service of a high complexity hospital in Bogotá, Colombia.

Results As a result of the data analysis, five themes or categories arose: getting into an unknown world; looking for care; submitting to using an absorbent continence product; my body’s reaction to using an absorbent continence product; and adapting or trying to recover my independence.

Conclusions The lived experience of patients who were required to unnecessarily wear absorbent incontinence products while in hospital and the ensuing detrimental effect on their psychological and physical wellbeing are described. Health professionals, whilst under time and other constraints, need to understand the patients’ perspective and their desire to maintain independence with their elimination needs when in hospital. The unnecessary use of absorbent incontinence products is not best practice, is not economical healthcare, and it potentially has adverse effects on the environment.

Introduction

Absorbent pads or incontinence diapers are sanitary products that are used for personal hygiene in the presence of urinary or faecal incontinence. Correct use of these products contributes to the containment and absorption of urine and faeces1 by wicking fluids away from the skin2. Nevertheless, it is becoming apparent in some healthcare facilities that nurses are unjustifiably using these continence aids on continent people3. Even studies like Zisberg (2011) show the high tendency among hospital staff to use incontinence diapers in patients whose condition do not require such intervention4.

Diaper use in older adults is associated with multiple adverse outcomes. For example, studies have found that diaper use: negatively influences self-esteem and perceived quality of life4; may lead to urinary or faecal incontinence5; increases dependency to carry out day-to-day activities6; and leads to the appearance of moisture-associated skin injuries7–9 and pressure injuries or urinary tract infections10 that complicate the patients’ health status, or even cause their death11. The adverse effects impair the quality of the health system and generate financial impacts due to the additional costs and the increase in hospital stays for the treatment of the skin damage incurred3. Additionally, the use of absorbent pads generates waste that pollutes the ecosystem12,13, and they can also pose additional medical expenses for the patient and/or their family14,15. Furthermore, they generate an increased burden of care for health personnel and/or family members due to the time and effort spent on changing absorbent products, hygiene and skin care3.

Studies indicate that this practice is utilised due to a lack of assessment and nursing interventions, other than application of an incontinence pad16. A study by Zurcher et al. (2011) found that nursing records mentioned the use of absorbent products without documenting a prior assessment of urinary continence17. Other studies show that health personnel have beliefs that relate incontinence to ageing16 and the use of diapers as the only hygiene treatment for the elderly18. They also mention the low use of elimination intervention strategies such as scheduled urination in nursing homes, a strategy that has more benefits compared to diaper use since it maintains continence, and promotes mobility and independence15,19.

Although the literature describes many problems related to the wearing of unnecessary absorbent incontinence products, the effects associated with the quality of life and experiences of people have not been thoroughly studied. During her clinical duties, the researcher observed in diaper-wearing continent people feelings of revulsion, discomfort and dissatisfaction with the care provided. However, when examining the literature, few studies address these factors. One example is the study by Alves et al. (2013)18 that describes nurses’ perceptions of how users of diapers where there was no valid clinical indication for their use, evidenced mistrust, insecurity, stress, sadness and discomfort, among others. Study data is based only on the perception of nurses and does not document the patients’ perspective.

The rationale for the current study therefore was to further investigate, explain and share continent patients ‘lived experiences’ of having to wear incontinence diapers or absorbent pads when they wished to be toileted whilst being treated as inpatients within a high-complexity hospital in Bogotá, Colombia.

Methodology

Research methods

A qualitative research technique was used to interview patients about their feelings of having to use incontinence diapers or absorbent pads as opposed to being assisted to the toilet to maintain their current state of urinary or faecal continence. The following questions were asked of patients recruited to the study:

- How do you describe your experience when using a diaper?

- What feelings has the diaper use generated in you?

- What factors do you think influenced your experience regarding diaper use?

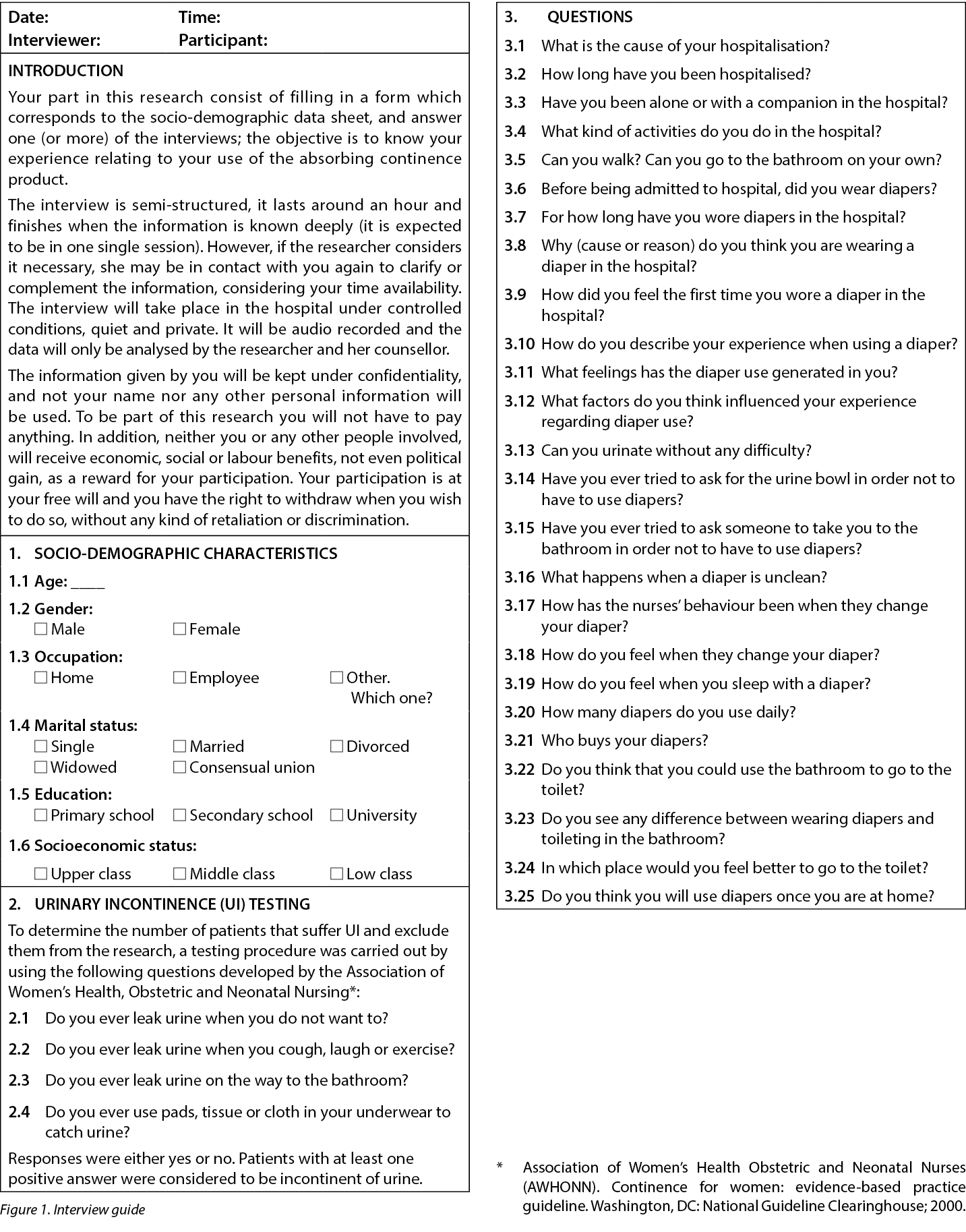

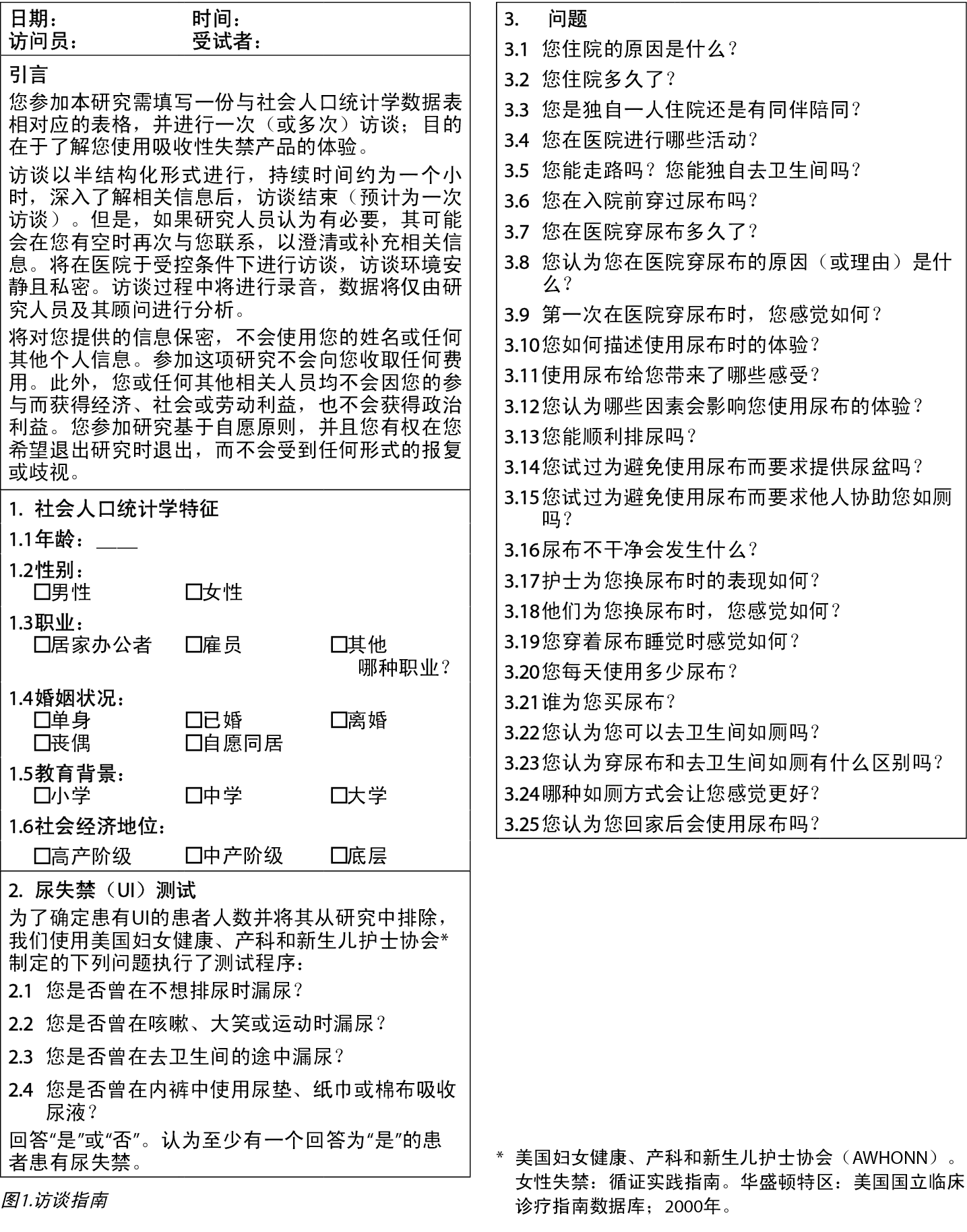

Data collection was carried out by pilot testing on two patients and was assessed using the Creswell criteria20 to confirm the operation of the interview guide (Figure 1) and the aspects that could be improved to incorporate them into the data collection process20.

The interviews were conducted by the researcher in a private place, and the data was collected via voice recordings and field notes that included information on non-verbal expressions20. During the session, the participant described their experience, additional questions were introduced to specify what they were reporting and, subsequently, the interview ended when data saturation was reached20.

Selection and recruitment criteria

Selection criteria included continent people without previous use of absorbent pads or incontinence diaper products and without disability or with a mild disability according to the PULSES profile.

Seven participants were selected and recruited from an internal medicine service of a high-complexity hospital in Bogotá, Colombia. Recruited patients were informed of the research study’s objectives, privacy and security measures and the option to withdraw at any moment without any compromise to clinical care provided. Written informed consent to participate in the study were obtained.

Sample size and data saturation

The sampling was theoretical (or purposeful) for the purpose of better understanding the issues central to the current study21. The interview was considered complete when the data collected described the phenomenon identified in the guiding questions and the total of interviews were adequate when data saturation occurred, that is to say, the data included enough information to replicate the study, no new information was being obtained in the interviews and further coding no longer deemed feasible22.

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed, stored and classified by a number to maintain patient anonymity. The tool used was ATLAS.ti program version 6.0 (2003–2010, ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin. Author: Dr Susanne Friese) for the organisation, coding and analysis of information23. Analysis was done according to Husserlian phenomenology since this allowed us to understand the lived experience of persons related to the phenomenon24. Fundamentally, this analysis directs nursing research away from personal preference, and directs it towards a purer return25, it allows us to know the phenomenon as it is lived by a person26 and produces an unbiased scientific knowledge that reinforces the principles and practices of nursing and contributes therefore to professional development27.

In the study, a constant immersion in the data was carried out in order to understand what is happening28. The researcher of this study constantly evaluated herself to neutralise preconceptions and not influence the object of study26. Based on participants’ statements, meaningful references, text excerpts or descriptors, and nominal codes, categories to describe the phenomenon were created. A second researcher was involved in validating data that was transcribed, contributing to the accuracy of the data process. Each resulting category was compared to the original descriptions for validation purposes.

Results

The study included seven continent people without a previous diagnosis of urinary or faecal incontinence and who had not previously used absorbent products or continence diapers. The average age of participants was around 74 years old and most were from a low socioeconomic background and had a low level of education. Upon further enquiry about reasons to use diapers, participants referred to having mobility difficulties to go to the bathroom, visual disability, dizziness, and alteration in lower extremities movements. All of them had a mild disability according to the PULSES profile and were able to go to the bathroom with assistance with walking or by using a walker device or a wheelchair.

From the data analysis, significant statements were identified, meanings were formulated and these were grouped in five common categories: getting into an unknown world; looking for care; submitting to using an absorbent continence product; my body’s reaction to using an absorbent continence product; and adapting or trying to recuperate my independence. Further descriptors and patient experiences under these categories are provided below.

Getting into an unknown world

This category expresses the transition the patient experienced when they were admitted as an inpatient to the hospital and how the admission affected their elimination pattern. At home, patients can go to the bathroom in an independent, private and peaceful way but the situation changes when they are admitted to hospital. Going to the bathroom while in hospital is difficult due to their health situation and that is why they seek the accompaniment of health personnel. However, as they do not find support in these people, the only option that they receive is to relieve themselves in the diapers.

A continent person with mobility problems attempting to go to the bathroom, secondary to visual impairment, reports:

While I was here, at the hospital, it was when I had to use the diaper… When I entered, they did not ask me if I wanted, they did it without asking, they told me: You need a diaper; you must wear it... and I said: Alright. Let’s do it... and since then I’ve been wearing the diaper. But it is better to go to the bathroom, it’s more hygienic, to go to the bathroom, I have to ask for help because I see shadows, sometimes they assist me, but other times they are busy with other patients and I have to wait – E6.

Looking for care

This category describes how these subjects tried to avoid diaper usage and decided to look for help to go to the bathroom. As provision of such assistance was not timely, and sometimes took hours, the patients’ capacity to contain urine or faecal elimination was limited, and a sense of urgency occurred. In the desire to contain elimination needs, they also expressed suffering, shame, resignation, discomfort, insomnia, abdominal pain and bloating. These sensations subsided after elimination. In this category a person describes:

I had a thrombosis. This whole side became paralyzed (points to the right side of the body), (...) I’m already using the walker... but still, I cannot go to the bathroom alone. The thing is that I’m afraid of falling… When I must go to the bathroom, I call them and tell them: take me to the bathroom! but sometimes they don’t have time... and (grunts)! (points to the abdomen and simulates pain). Last night, for instance, I had such horrible colic... it was because I asked them during two hours to come and take me to the bathroom and I was very hurried – E2.

Although patients tried to wait, eventually they reached a point where they could not resist the urge to eliminate. They then resigned themselves to excrete in the absorbent pad/incontinence diaper and experienced a momentary sense of relief.

Occasionally, the nursing team takes care of their urge to go to the bathroom on time. Someone mentions:

I have gone to the bathroom to relieve myself. Normally a nurse assists me. Yesterday, she took me to the bathroom, she helped me to sit and be comfortable... She is attentive; takes care of me; she always says: What do you want? What do I do? They all are very attentive; when they assist us, they do it with so much affection – E4.

Submitting to using an absorbent continence product

The category relates to those subjects who did not need to use diapers, but felt they ‘had’ to. They wanted to relieve themselves in the bathroom, but they did not receive any assistance despite insisting repeatedly to receive it. For that reason, they had to forgo their wants and decide to relieve themselves in absorbent pads/incontinence diapers. Over time, the patients stopped calling the nursing staff to be taken to the bathroom and they resigned themselves to wearing an absorbent pad/incontinence diaper. The patients feel at the mercy of the health personnel who have little time and are also experiencing a shortage of staff. As a result, this makes them feel restricted and vulnerable. The patients have made the following comments:

Well, I have to wear a diaper, but I don’t need it… wearing a diaper is uncomfortable, but this is what I had to do. Regardless, I like to go to the bathroom and try to find someone who helps me, they just don’t assist me – E1.

I feel like an impediment to wear a diaper; it doesn’t feel good… I feel dependent on the will of the people – E6.

My body’s reaction to using an absorbent continence product

This category describes the patients’ expressed and unpleasant feelings about wearing an absorbent continence product. They used terms such as: moisture; warmth, load; burning sensation; dirt, chafe or discomfort; and even the loss of sleep. Furthermore, they worried about expenses incurred by their families when they had to buy absorbent pads or incontinence diapers. Another issue they worried about was skin injuries due to diaper change delay. People made these comments about this category:

When I wear a diaper, I feel dirty… too warm; you try to sweat. Further, the diaper makes me feel annoyed, cold, wet; I feel bad. That’s why I take it off or I tell the nurse to change it for me. I can last for hours with the diaper wet... and sometimes that produces some kind of peeling, scorching… that is annoying – E6.

Now I am burned… because they took too long to change my diaper; I burn completely, that’s why they are putting ointment on – E7.

I feel that wearing a diaper alters my sleep. I feel uncomfortable and I can’t rest properly because of the dampness – E4.

I think buying diapers affects me financially… Sometimes my husband has no money for diapers, and he has to borrow some money, then he comes and buys them – E2.

Adapting or trying to recover my independence

The category refers to how either patients adopted to the habit of relieving themselves in the absorbent pad or incontinence products without a clinical diagnosis of incontinence or other physical or reason to do so, just because there is no nursing assistance to enable them to go to the toilet. Other people persisted in avoiding the use of incontinent devices and tried to recover their independence by doing activities that helped them to mobilise or even going by themselves to the bathroom, increasing falls and injury risks. Some people mentioned:

I don’t feel bad for wearing a diaper, one gets used to it… now I ask that they put the diaper on me… I like to go to the bathroom, but I ask to be placed (in the diaper) due laziness! – E6.

So when I go to the bathroom at least I walk a little bit, and also I kind of feel life as before. I want to go back to my old life, go to the bathroom, normal – E5.

I tried to go to the bathroom alone because sometimes assistants are busy with other patients. I always hit against walls because I do not see. Yesterday I went to the bathroom... they didn’t even notice it – E6.

Discussion

This small selective sample size qualitative study describes patients’ experience of having to use absorbent pads/incontinence diapers without a valid clinical indication for their use as a shocking experience. In this study the patients felt obliged to use these types of devices because they had no other option, which generated negative consequences on a physical and personal level that could have been avoided.

Studies like Zisberg (2011) show the high tendency among hospital staff to use incontinence diapers in patients whose condition does not require such intervention4. This is due to the shortage of personnel, the lack of time to build better patient care planning16, and the delegation of care to technical personnel without adequate supervision18. Within the hospital in which this study was held, a similar situation was found – nursing staff delegate the task of needs relating to elimination to the technician or ancillary staff and do not supervise the type of people who are being provided with diapers.

However, regardless of whether patients are continent or have the possibility of going to the bathroom with assistance, it is becoming increasingly common for health personnel to routinely use diapers for hygiene purposes in the elderly18 or people with functional disabilities15. This occurs because health personnel do not assess continence, they associate urinary incontinence with ageing18,29, and they believe that people with functional disabilities need to wear diapers15.

This study also observed that at home patients can go to the bathroom in an independent manner; however, this situation changes when they are admitted to hospital since the only option they are given is to relieve themselves in a diaper. This is not best practice since continent people should use the bathroom. According to studies, even semi-dependent patients should not use a diaper to relieve themselves. On the contrary, they need to go to the bathroom to help stimulate their mobility and independence15,30.

In this study the patients who felt an urge to go to the bathroom and needed nursing assistance to do so tried to resist the use of absorbent pads/incontinence diapers. However, as the hours went by without any nursing assistance, they had no other option but to give way and relieve themselves within the diapers. In the desire to contain elimination needs, they also expressed suffering, shame, resignation, discomfort, insomnia, abdominal pain and bloating. These sensations subsided after elimination. When searching the literature, no studies were found that describe in detail this resistance of continent patients to the use of a diaper. For this reason, the current study allowed a greater insight into patient experiences.

Furthermore, as outlined above, although patients tried to wait, eventually they reached a point where they could not resist the urge to eliminate. They then resigned themselves to excrete in the absorbent pad/incontinence diaper and experienced unpleasant sensations. They described discomfort and unpleasantness from being in prolonged contact with their faeces or urine. The feelings verbalised were ones of restlessness, frustration, hopelessness and in particular the loss of independence. They also felt uncomfortable with the sensation of humidity, heat and pressure in addition to effects on their skin such as burning and pain from dermatitis associated with incontinence. When examining the literature, few studies address these factors; however, some results are similar. One study is by Alves et al. (2013) that describes nurses’ perceptions of diaper users where there is no validated clinical indication for their use. The findings are distrust, insecurity, stress, sadness and discomfort, in addition to the loss of identity, dependency or fragility due the use of diapers18. In another study on the perception of hospitalised elderly people, they mention the feeling of discomfort, low self-esteem, revulsion, itching, pain, inefficiency, heat and motor restriction6.

After being exposed to these sensations, some patients adopt the habit of relieving themselves in the absorbent pad or incontinence products. The study of Zisberg (2011) says that, even among continent patients, diaper use may be “addictive,” at least in the short term, which may explain the behaviour of these patients4. On the other hand, other people persisted in avoiding the use of incontinent devices and tried to recover their independence by doing activities that helped them to mobilise or even going by themselves to the bathroom, increasing falls and injury risks.

The literature has similar results; however, there is little research, and this allows the current study to provide a greater insight into the patients’ experiences of being forced into using diapers unnecessarily. This practice exposes patients to potential skin damage and psychological trauma that can mean a problematic or longer recovery time31. People who are continent of urine seek nursing assistance to go to the bathroom and maintain their level of independence. However, this study found that on most occasions they do not get support from these people and the only option that they receive is to relieve themselves in the diapers.

In these cases, the absorbent pad is used unnecessarily and can be replaced by other methods. According to Jonasson et al. (2016), there is a need to move towards a more person-centred approach as far as possible16, using methods such as scheduled assistance when going to the bathroom to help to strengthen mobility, improve autonomy and independence30,32, and maintain health and wellbeing16.

For these methods to be implemented by hospital staff, a change in practice is necessary. A study by Bernard et al. (2020) outlines how nurse educator and administration support can contribute to reduce diapers use to improve the patient care experience. Nurse educators can teach proper toileting, explain how to assess the patients’ continence and how to use the patients’ toileting schedules, and select appropriate collection/containment devices. Also, administrative support contributes to the implementation of programs and protocols on best practices in continence care, restricts the use of absorbent pads, increases the availability of optional urinary/faecal containment devices and provides tools to support toileting, such as adequate facilities and nurses and physiotherapists trained in continence management33.

Conclusions

The results of the study show that the Colombian health system does not always respond efficiently to the clinical needs of patients with mild disabilities to maintain independence with urinary and faecal continence. The provision of assistance nursing was not timely and forced patients to wear diapers unnecessarily and involuntarily, which undermined self-confidence, patient safety, and caused physical and psychological consequences. There were also economic implications that affect the family and health institutions with the increase in treatment costs. This study shows how health institutions do not always consider physical and social functionality and the preference of users regarding their elimination needs, thereby generating dissatisfaction, discomfort, vulnerability and loss of dependency.

In this sense, phenomenological studies such as this one are a window for reflection and a path to achieve a better quality of care34. Health professionals, whilst under time and other constraints, need to understand the patients’ perspective and maintain independence regarding their elimination needs when in hospital. That is why individualised holistic care16 is needed to offer care beyond the usual care procedures, considering the priorities and elimination needs of patients.

Limitations

This research study had a very small theoretical sample size. Therefore, the results of the study should not be generalised to all health facilities. More research is needed on this phenomenon.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the study participants for their cooperation.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics statement

This study was endorsed by the Faculty of Nursing Ethics Committee, National University of Colombia: approval (021-18) and the Research Ethics Committee in health facility, approval (119/18).

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

关于非必要使用吸收性失禁产品的患者体验:一项小型体验式定性研究

Sandra Guerrero Gamboa, Angie Viviana Ariza Garzón

DOI: 10.33235/wcet.43.4.13-19

摘要

目的 描述哥伦比亚波哥大一家医院中非必要使用吸收性失禁产品为一小组住院患者带来的生活体验。

方法 定性和现象学研究。在征得受试者同意后进行了访谈,并对受试者进行了观察,直至数据饱和。随后,根据胡塞尔方法论对所有数据进行了转录和分析,得出所见现象的主题和类别。

受试者和环境 从哥伦比亚波哥大一家高复杂度医院的内科服务部门招募了7例既往未使用过吸收性失禁产品且根据PULSES评分量表处于轻度残疾状态的失禁患者,作为选择性样本。

结果 经过数据分析,得出了五个主题或类别,具体如下:进入未知世界;寻求护理;接受使用吸收性失禁产品;身体对使用吸收性失禁产品的反应;以及适应或尝试恢复独立性。

结论 描述了要求在住院期间非必要使用吸收性失禁产品的患者的生活体验及其继而对患者心理和身体健康产生的不利影响。医疗保健专业人员在时间和其他方面受限的情况下,需要了解患者的观点及其在住院期间保持排泄需求方面独立的愿望。非必要使用吸收性失禁产品并非最佳实践,也并非具有经济效益的医疗保健,其可能对环境产生不利影响。

引言

吸水垫或失禁尿布属于卫生用品,用于在存在尿失禁或大便失禁的情况下保持个人卫生。正确使用此类产品有助于吸收皮肤上的液体2,进而承接和吸收尿液及粪便1。然而,在一些医疗机构中,护士不合理地对失禁患者使用这些辅助工具的现象越来越明显3。Zisberg(2011)等人进行的研究也表明,医院工作人员非常倾向于对病情无需此类干预的患者使用失禁尿布4。

老年人使用尿布与多种不良结局相关。例如,研究发现,使用尿布会造成以下后果:对自尊和感知生活质量产生负面影响4;可能导致尿失禁或大便失禁5;増加开展日常活动的依赖性6;导致出现潮湿相关皮肤损伤7-9和压力性损伤或尿路感染10,使患者健康状况更为复杂,甚至导致患者死亡11。这些负面影响会损害卫生系统的质量,并因治疗皮肤损伤而产生的额外费用和住院时间延长而造成财务方面的影响3。此外,使用吸水垫还会产生污染生态系统的废物12,13,并导致患者和/或其家人负担额外的医疗费用14,15。而且,还需在更换吸收性产品、进行卫生和皮肤护理方面花费时间和精力,进一步増加了医务人员和/或家庭成员的护理负担3。

研究表明,采取这种做法的原因在于除了使用失禁垫之外,缺乏评估和护理干预16。Zurcher等人(2011)进行的研究显示,护理记录中提到了使用吸收性产品,但未记录既往进行的尿失禁评估17。其他研究表明,医务人员认为失禁与年龄相关16,并将使用尿布作为老年人的唯一卫生处理方法18。他们还提到,养老院很少采用计划排尿等排泄干预策略,这一策略与使用尿布相比具有更多益处,因为其可保持自制,并提高活动能力和独立性15,19。

虽然文献描述了许多与非必要使用吸收性失禁产品相关的问题,但与患者生活质量和体验相关的影响尚未得到深入研究。在临床工作中,研究人员观察到使用尿布的失禁患者对所提供护理的厌恶、不适和不满。然而,在查阅文献时,很少有研究涉及这些因素。例如,Alves等人(2013)进行的研究18描述了护士对无有效临床应用指征的尿布使用者的认知,结果表明此类患者表现出不信任、不安全感、压力、悲伤和不适等。研究数据仅基于护士的认知,不记录患者的观点。

因此,本研究的基本原理是进一步研究、解释和分享失禁患者在哥伦比亚波哥大一家高复杂度医院接受住院治疗期间如厕时必须使用失禁尿布或吸水垫的Åg生活体验Åh。

方法

研究方法

采用定性研究技术对患者进行访谈,了解他们对于必须使用失禁尿布或吸水垫而不是由他人协助如厕以维持当前尿失禁或大便失禁状态的感觉。对这项研究招募的患者提出了以下问题:

- 您如何描述使用尿布时的体验?

- 您对使用尿布有什么感觉?

- 您认为哪些因素会影响您使用尿布的体验?

通过对2例患者进行试点测试来收集数据,并使用Creswell标准20进行评估,以确认访谈指南的操作(图1)和可改进的方面,进而将这些方面纳入数据收集过程20。

由研究人员在私人场所进行访谈,通过录音和现场笔记(包括非口头表达的信息)收集数

据20。在访谈期间,受试者描述了他们的体验,并提出了其他问题,以具体说明他们报告的内容,随后,当数据饱和时,访谈结束20。

选择和招募标准

选择标准包括既往未使用过吸水垫或失禁尿布产品且根据PULSES评分量表无残疾或处于轻度残疾状态的失禁患者。

从哥伦比亚波哥大一家高复杂度医院的内科服务部门选择并招募了7例受试者。已告知招募的患者研究目的、隐私和安全措施以及在不影响所提供临床护理的情况下随时退出研究的选择。获得了受试者同意参加研究的书面知情同意书。

样本量和数据饱和

抽样具有理论性(或目的性),旨在更好地理解本研究的核心问题21。当收集的数据描述了指导性问题中确定的现象时,认为已完成访谈,并且当数据饱和时,访谈总数充足,换言之,数据包括足够的信息来重复该研究,在访谈中未获得新信息,并且认为进一步编码不再可

行22。

数据分析

访谈内容均已抄录、储存并按编号分类,以保持患者的匿名性。组织、编码和信息分析使用的工具为ATLAS.ti程序版本6.0(2003-2010,

ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin;作者:Susanne Friese博士)23。根据胡塞尔现象学进行了分析,使我们能够了解与现象学相关的个人生活经验24。究其根本,该分析使护理研究脱离了个人偏好,并将其引向更纯粹的回归本质25,它使我们能够了解个人的生活现象26,并产生无偏倚的科学知识,加强护理原则和实践,最终促进专业发展27。

在研究过程中,对数据进行了持续的沉浸式研究,以了解正在发生的事情28。本研究的研究人员不断进行自我评估,以消除先入为主的观念,而不影响研究对象26。根据受试者的陈述、有意义的参考文献、文本摘录或描述符以及名义代码,创建了描述该现象的类别。第二名研究人员参与了转录数据的验证工作,从而提高数据处理的准确性。将每个由此产生的类别与原始描述进行比较,以便进行验证。

结果

该研究纳入了7例既往未诊断出患有尿失禁或大便失禁且既往未使用过吸收性产品或失禁尿布的失禁患者。受试者的平均年龄约为74岁,大多数的社会经济地位较低,受教育水平也较低。进一步询问使用尿布的原因时,受试者提到如厕时行动困难、视力残疾、头晕和下肢运动改变。根据PULSES评分量表,所有患者均处于轻度残疾状态,能够通过行走或在助行器或轮椅的辅助下如厕。

通过数据分析确定了重要陈述,形成了相应的含义,并将其归为五个常见类别,具体如下:进入未知世界;寻求护理;接受使用吸收性失禁产品;身体对使用吸收性失禁产品的反应;以及适应或尝试恢复独立性。下文详细描述了这些类别下的描述符和患者体验。

进入未知世界

该类别表示患者作为住院患者入院时所经历的转变,以及入院对其排泄模式的影响。在家中,患者能够以私人、和平的方式独立如厕,但入院后,这种情况就会发生变化。考虑到患者的健康状况,住院期间如厕较为困难,这也是他们寻求医务人员陪同的原因。然而,如果无法获得医务人员的支持,他们拥有的唯一选择便是使用尿布进行排泄。

一例试图如厕的行动不便失禁患者(继发于视觉损害)报告称:

当我在医院时,我必须使用尿布ÅcÅc在我入院时,他们并未了解我的意愿,在未经询问的情况下直接告诉我:你需要使用尿布;你必须穿上它ÅcÅc然后,我回答道:好的,就这么做ÅcÅc从那时起,我便一直穿着尿布。但去卫生间更加卫生,是更好的选择,但我要需要在医务人员的帮助下如厕,因为我看不清,有时他们会协助我,但有时他们忙于照顾其他患者,我就得等着-E6.

寻求护理

该类别描述了这些受试者如何尝试避免使用尿布,并决定寻求帮助以进行如厕。由于无法及时提供此类援助,有时甚至需要等待数小时,且患者控制尿液或粪便排泄的能力有限,因而产生急迫感。在希望控制排泄需求的过程中,他们还表达了痛苦、羞耻、顺从、不适、失眠、腹痛和腹胀的感觉。这些感觉在排泄后消退。在该类别中,一例患者描述道:

我患有血栓形成。整个身体一侧瘫痪(指向身体右侧),(ÅcÅc)我已经在使用助行器ÅcÅc但仍然无法独立如厕。主要原因是我害怕摔倒ÅcÅc当我必须如厕时,我给医务人员打电话,告诉他们:请协助我如厕!但有时他们没有时间和(咕哝声)!(指向腹部,模拟疼痛感觉)。例如,昨天晚上,我希望他们在两个小时内前来带我去卫生间,我非常急切,因此,我经历了此类可怕的肠绞痛-E2.

虽然患者尽力等待,但最终还是无法抵抗排泄冲动。于是,他们迫于无奈,只能使用吸收垫/失禁尿布进行排泄,并获得了短暂的解脱感。

偶尔,护理团队会及时帮助他们处理如厕冲动。有患者表示:

我已经去卫生间上过厕所了。通常是护士协助我。昨天,她带我去卫生间,扶我坐下,进行舒适的排泄ÅcÅc她很细心;照顾着我;总是询问:你想做什么?我该怎么做?所有医务人员都非常细心;在协助我们时,他们总是给予我们非常多的关爱-E4.

接受使用吸收性失禁产品

该类别与无需使用尿布但认为其Åg必须Åh使用的受试者相关。他们希望在洗手间如厕,然而,虽然一再坚持想要接受协助,但其并未得到任何辅助。因此,他们不得不放弃自己的欲望,决定使用吸水垫/失禁尿布进行排泄。随着时间的推移,患者不再呼叫护理人员协助他们如厕,而接受使用吸水垫/失禁尿布。医务人员空闲时间少,人手不足,患者感觉自己只能任其摆布。因此,这使他们感到受限和脆弱。患者做出以下评论:

唉,我必须穿尿布,但我并不需要ÅcÅc穿尿布很不舒服,但我必须这么做。无论如何,我还是喜欢去卫生间,并尝试找到一个可以协助我的人,他们就是不帮我-E1.

我感觉穿尿布是一种障碍;让人感觉不适ÅcÅc我感到对他人的意愿产生了依赖-E6.

身体对使用吸收性失禁产品的反应

该类别描述了患者对穿吸收性失禁产品表达的不愉快的感觉。他们使用的术语包括:潮湿;温热,负担;烧灼感;灰尘,擦痛或不适;甚至是睡眠不足。此外,他们还担心购买吸水垫或失禁尿布会给家庭带来开支。他们担心的另一个问题是延迟更换尿布导致的皮肤损伤。患者对这一类别发表了以下评论:

当我穿尿布时,我感觉很脏ÅcÅc太热了;你可能会出汗。此外,尿布让我感到恼怒、寒冷、潮湿;我感到很糟糕。所以我会把它取下来,或者告诉护士帮我更换它。我可以在尿布湿透的情况下坚持几个小时ÅcÅc有时这会导致脱皮、灼热ÅcÅc令人恼怒-E6.

现在我就有烧灼感ÅcÅc他们花费了太长时间来更换我的尿布;我有严重的烧灼感,因此他们为我涂上软膏-E7.

我觉得穿尿布会影响我的睡眠。由于潮湿,我感觉不适,无法正常休息-E4.

我认为买尿布会増加我的经济负担ÅcÅc有时,我丈夫没钱买尿布,他不得不借钱去买-E2.

适应或尝试恢复独立性

该类别是指患者在临床未诊断为尿失禁或不存在其他生理状况或原因的情况下,仅因为没有护理人员协助其如厕,而习惯使用吸收垫或失禁产品进行排泄。其他患者坚持避免使用失禁装置,并且会进行帮助他们移动的活动,甚至是自行如厕,来尝试恢复独立性,而这会増加跌倒和受伤风险。一些患者表示:

我不觉得穿尿布有什么不好,总会习惯的ÅcÅc现在我要求他们给我穿上尿布ÅcÅc我喜欢去卫生间,但由于懒惰,我要求给我穿(尿布)!

-E6.

所以,当我去卫生间的时候,至少我会走一点路,感觉就像回到了以前的生活。我想回到我以前的生活,去卫生间正常如厕-E5.

有时医务人员忙于照顾其他患者,因此我尝试一个人去卫生间。但我总是撞到墙,因为我看不见。昨天我去了卫生间ÅcÅc他们甚至没有注意到-E6.

讨论

这项选择性样本量较小的定性研究描述了患者在无有效临床应用指征的情况下必须使用吸水垫/失禁尿布的体验,结果令人震惊。在本研究中,患者感觉他们没有其他选择,必须使用此类装置,这对他们的身体及其个人均造成了本可以避免的负面后果。

Zisberg(2011)等人进行的研究表明,医院工作人员非常倾向于对病情无需此类干预的患者使用失禁尿布4。造成上述情况的原因包括:人员短缺、缺乏时间来制定更好的患者护理计

划16,以及在未进行适当监督的情况下将护理工作委托给技术人员18。在参加这项研究的医院中,也发现了类似的情况Å\Å\护理人员将排泄需求相关任务委托给技术人员或辅助人员,而不对获得尿布的人员进行监督。

然而,无论患者是失禁还是有可能在协助下如厕,医务人员在老年人18或功能性残疾患者15中常规使用尿布进行卫生越来越普遍。这是因为医务人员不会对失禁进行评估,他们觉得尿失禁与年龄相关18,29,并认为功能性残疾患者需要穿尿布15。

本研究还发现,患者在家中可以独立如厕;但入院后,这种情况会发生变化,因为他们唯一的选择就是使用尿布进行排泄。这不是最佳做法,因为失禁患者应该使用卫生间。根据相关研究,即使是半依赖性患者也不应使用尿布进行排泄。相反,他们需要去卫生间,以促进他们的行动能力和独立性15,30。

在本研究中,有如厕冲动且需要护理人员协助的患者试图抗拒使用吸水垫/失禁尿布。然而,随着时间的推移,在没有任何护理人员协助的情况下,他们别无选择,只能接受使用尿布进行排泄。在希望控制排泄需求的过程中,他们还表达了痛苦、羞耻、顺从、不适、失眠、腹痛和腹胀的感觉。这些感觉在排泄后消退。在检索文献时,未发现任何详细描述失禁患者对使用尿布的抵触情绪的研究。因此,本研究使我们能够更深入地了解患者的体验。

此外,如上文所述,虽然患者尝试等待,但最终还是无法抵抗排泄冲动。然后,他们只好使用吸收垫/失禁尿布进行排泄,并产生了不愉快的感觉。患者描述了长期接触粪便或尿液带来的不适和不快。口头表述的感觉包括躁动、沮丧、绝望,尤其是感到丧失独立性。除了对皮肤的影响,如失禁相关皮炎引起的烧灼感和疼痛外,他们还对潮湿、高温和压力的感觉感到不适。在查阅文献时,很少有研究阐明这些因素;不过,一些研究结果相似。Alves等人(2013)进行的一项研究描述了护士对无经验证的临床使用指征的尿布使用者的认知。研究结果表明此类患者表现出不信任、不安全感、压力、悲伤和不适,此外,还表现出使用尿布导致的自我身份丧失、依赖或脆弱18。在另一项关于住院老年患者认知的研究中,他们提到了感觉不适、低自尊、厌恶、发痒、疼痛、低效、发热和运动受限6。

产生这些感觉后,一些患者会习惯于使用吸收垫或失禁产品进行排泄。Zisberg(2011)进行的研究指出,即使在失禁患者中,使用尿布也可能会Åg成瘾Åh,至少在短期内是如此,这或许可以解释这些患者的表现4。另一方面,其他患者则坚持避免使用失禁装置,并且会进行帮助他们移动的活动,甚至是自行如厕,来尝试恢复独立性,而这会増加跌倒和受伤风险。

文献中也有类似的结果;但是,相关研究较少,使得本研究能够更深入地了解患者被迫在非必要情况下使用尿布的体验。这种做法会给患者带来潜在的皮肤损伤和心理创伤,这可能意味着恢复过程中会遇到问题或恢复时间会延长31。尿失禁患者寻求护理人员协助如厕,保持其独立性水平。然而,这项研究发现,在大多数情况下,他们并没有获得护理人员的支持,唯一的选择就是使用尿布进行排泄。

在此类情况下,不必要地使用了吸收垫,并且可以用其他方法代替。Jonasson等人(2016)进行的研究显示,需要尽可能采用更加以人为本的方法16,使用计划如厕协助等方法,以帮助加强行动能力、提高自主性和独立性30,32,并保持健康和幸福感16。

如要促进医院工作人员采用这些方法,有必要改变当前的做法。Bernard等人(2020)进行的研究概述了护理教育工作者和行政支持在减少尿布使用方面作出的贡献,这有助于改善患者的护理体验。护理教育工作者可以教授正确的如厕方法,解释如何评估患者的失禁情况以及如何使用患者如厕时间表,并选择适当的收集/承接装置。此外,行政支持也有助于实施失禁护理最佳实践相关项目和方案,限制使用吸水垫,増加可选尿液/粪便承接器的可用性,并提供支持如厕的工具,如适当的设施和接受过失禁管理培训的护士和物理治疗师33。

结论

研究结果表明,哥伦比亚卫生系统并不总是能够高效满足轻度残疾患者的临床需求,使他们能够在尿失禁和粪便失禁方面保持独立性。无法及时提供协助护理,迫使患者在不必要的情况下非自愿使用尿布,这会损害患者的自信心和安全性,造成生理和心理后果。治疗费用的増加也会对家庭和卫生机构造成经济影响。本研究表明,卫生机构并不总是考虑使用者的生理和社会功能及其对排泄需求的偏好,导致使用者不满、不适、脆弱和依赖性丧失。

就此而言,与本研究类似的现象学研究是一扇反思之窗,也是提高护理质量的途径34。医疗保健专业人员在时间和其他方面受限的情况下,需了解患者的观点,并在帮助患者在住院期间保持排泄需求方面的独立性。这解释了为什么需进行个性化整体护理16,以提供常规护理程序之外的护理服务,同时考虑到患者的优先事项和排泄需求。

局限性

本研究的理论样本量非常小。因此,研究结果不应推广至所有卫生机构。该现象还需要进行进一步研究。

致谢

我们要感谢所有研究受试者的配合。

利益冲突声明

本研究无任何利益冲突需要声明。

伦理声明

本研究获得了哥伦比亚国立大学护理学院伦理委员会(021-18)和卫生机构研究伦理委员会的批准(119/18)。

资助

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Sandra Guerrero Gamboa

PhD MN ETN RN

Associate Professor, Faculty of Nursing, National University of Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

Angie Viviana Ariza Garzón*

MN RN

National University of Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

Email avarizag@unal.edu.co

* Corresponding author

References

- Qin Y. Medical textile materials. Woodhead Publishing; 2015.

- De Sousa Lopes Reis Do Arco HM, Mendes da Costa A, Machado Gomes B, Anacleto N, Jorge da Silva RA, Peixe da Fonseca SC. Nursing interventions in dermatitis associated to incontinence integrative literature review. Enfermería Glob 2018;17(52):689–730.

- Palese A, Regattin L, Venuti F, et al. Incontinence pad use in patients admitted to medical wards: an Italian multicenter prospective cohort study. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs 2007;34(6):649–54.

- Zisberg A. Incontinence brief use in acute hospitalized patients with no prior incontinence. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs 2011;38(5):559–64.

- Zisberg A, Sinoff G, Gur-Yaish N, Admi H, Shadmi E. In-hospital use of continence aids and new-onset urinary incontinence in adults aged 70 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59(6):1099–1104.

- de Almeida Ferreira Alves L, Ferreira Santana R, da Silva Schulz R. Nursing staffs’ perceptions of the use of adult diapers in hospital. Rev Enferm UERJ 2014;22(3):371–75.

- Fader M, Clarke-O’Neill S, Cook D, Dean G, Brooks R, Cottenden A, Malone-Lee J. Management of night-time urinary incontinence in residential settings for older people: an investigation into the effects of different pad changing regimes on skin health. J Clin Nurs 2003;12(3):374–86.

- Brown D. Diapers and underpads. Part 1: skin integrity outcomes. Ostomy Wound Manage 1994;40:20–22.

- Fader M, Bain D, Cottenden A. Effects of absorbent incontinence pads on pressure management mattresses. J Adv Nurs 2004;48(6):569–74.

- Christini Silva T, Mazzo A, Rodrigues Santos RC, Jorge BM, Souza Júnior VD, Costa Mendes IA. Consequences of adult patients using disposable diapers: implications for nursing care. Aquichan 2015;15(1):21–30.

- Beeckman D, Van Lancker A, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of incontinence-associated dermatitis, incontinence, and moisture as risk factors for pressure ulcer development. Res Nurs Heal 2014;37(3):204–18.

- Thompson E, Rounsefell B, Lin F, Clarke W, O’Brien KR. Adult incontinence products are a larger and faster growing waste issue than disposable infant nappies (diapers) in Australia. Waste Manage 2022;152:30–7.

- Ntekpe ME, Okon E, Ndifreke E, Hussain S. Disposable diapers: impact of disposal methods on public health and the environment. Am J Med Pub Health 2020;1(2):1–7.

- Bitencourt G, Santana R. Evaluation scale for the use of adult diapers and absorbent products: methodological study. Online Braz J Nurs 2021;20:1–13.

- Bitencourt GR, Alves LAF, Santana RF. Practice of use of diapers in hospitalized adults and elderly: cross-sectional study. Rev Bras Enferm 2018;71(2):343–49.

- Jonasson L, Josefsson K. Staff experiences of the management of older adults with urinary incontinence. Health Aging Res 2016;5(16):1–11.

- Zurcher S, Saxer S, Schwendimann R. Urinary incontinence in hospitalised elderly patients: do nurses recognise and manage the problem? Nurs Res Prac 2011;1–5.

- Alves L, Santana R. Perceptions of the nursing team about the use of geriatric diapers in the hospital. Ciênc Cuid Saúde 2013;12(1):19–25.

- Roe B, Flanagan L, Jack B, et al. Systematic review of the management of incontinence and promotion of continence in older people in care homes: descriptive studies with urinary incontinence as primary focus. J Adv Nurs 2011;67(2):228–50

- Hernández Sampieri R, Fernández Collado C, Baptista Lucio M. Metodología de la investigación científica. 5th ed. Mexico: McGraw-Hill Interamericana; 2020.

- Coyne IT. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling: merging or clear boundaries? J Adv Nurs 1997;26(3):623–30.

- Fusch P, Lawrence N. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual Rep 2015;20(9):1408–16.

- San Martín Cantero D. Grounded theory and ATLAS.ti: methodological resources for educational research. Rev Electrónica Investigación Educativa 2014;16(1):104–122.

- Bahadur S. Phenomenology: a philosophy and method of inquiry. J Educ Educ Dev 2018;5(1):215–22.

- Schultz G, Cobb-Stevens R. Husserl’s theory of wholes and parts and the methodology of nursing research. Nurs Philos 2004;5(3):216–23.

- Neubauer B, Witkop C, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ 2019;8(2):90–7.

- Cuesta Benjumea C. Qualitative research and development of nursing knowledge. Texto Contexto Enferm 2010;19(4):762–68.

- Maher C, Hadfield M, Hutchings M, Eyto A. Ensuring rigor in qualitative data analysis: a design research approach to coding combining NVivo with traditional material methods. Int J Qual Method 2018;17:1–13.

- Rodriguez N, Sackley C, Badger F. Exploring the facets of continence care: a continence survey of care homes for older people in Birmingham. J Clin Nurs 2007;16(5):954–62.

- Jirovec M. The impact of daily exercise on the mobility, balance and urine control of cognitively impaired nursing home residents. Int J Nurs Stud 1991;28(2):145–51.

- Alligood R, Tomey M. Nursing theorists and their work. 7th ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2010.

- Schnelle J, Alessi C, Simmons S, Al-Samarrai N. Translating clinical research into practice: a randomised controlled trial of exercise and incontinence care with nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50(9):1476–83.

- Bernard L, Stephens M, Kuhnke J L. Prevention of incontinence-associated dermatitis linked with briefs use in acute care: a quality improvement project. NSWOC 2020;31(2):28–37.

- Palacios D, Corral I. The basics and development of a phenomenological research protocol in nursing. Enferm Intensiva 2010;21(2):68–73.