Volume 44 Number 3

The world is no longer flat

Colleen Drolshagen, Renee Malandrino, Jessica Simmons, George Skountrianos, Wil Walker

Keywords peristomal skin complications, evidence, convexity, soft convexity, compressibility, ostomy care.

For referencing Drolshagen C, et al. The world is no longer flat. WCET® Journal Supplement. 2024;44(3)Sup:s6-10.

DOI 10.33235/wcet.44.3.sup.s6-10

Abstract

Evidence supporting clinical decision-making in the specialty of ostomy care regarding prescriptive product use has been sparse. Many clinical decisions in ostomy care have been based on either clinician experience, or from teachings and beliefs that have evolved over many years but are not based in evidence. There is now a rich and varied tapestry of evidence supporting clinicians regarding the use of convexity earlier in the patient’s journey, particularly of the more compressible types (soft) convexity products.

This article reviews the recent evidence concerning the use of more compressible barriers in ostomy care, a relatively newer addition to the clinician’s armamentarium, for managing patients. It provides an analysis of the data that supports using these products, sooner rather than later, in achieving a more secure skin seal, and improving patient outcomes compared with using flat skin barriers.

Introduction

In the beginning, clinicians may have relied on their education, mentors, word of mouth and habit to help shape how they care for those living with an ostomy. Now, clinicians can rely on a plethora of evidence to guide and support their practice. Prevention and treatment of peristomal skin complications (PSCs), has always been a major focus of the stoma care nurse as PSCs can impact a person’s quality of life, prolong hospital stays and have an economic burden for both the patient and the healthcare system. The newer evidence supporting the use of convex skin barriers with characteristics making these barriers compressible and flexible earlier in the patient’s journey to help prevent and manage PSCs is now readily available. Section 2 of this supplement described the development of these characteristics with descriptors and how they interplay to help achieve a reliable skin seal. In this article, we present clinical evidence highlighting the beneficial use of soft convexity and its impact on peristomal skin health, quality of life, and the economic and clinical burden of the management of PSCs. This evidence underscores the support for early adoption of soft convexity in the patient’s journey.

The challenge

Despite improved surgical techniques (such as robotic laparoscopic surgery), pre-operative stoma site marking, best practice guidelines from global professional ostomy nursing organisations (such as WOCN Society, ASCN etc.), industry product innovations (such as infused skin barriers), and new product improvements (such as softer, more compressible, convex skin barriers); one might assume the number of PSCs should be decreasing. However, in a multinational survey of 4235 people with ostomies in 13 countries, 73% of 4227 reported experiencing a peristomal skin complications (PSCs) in the past six months with only 31% of the respondents seeking help from a stoma care nurse or healthcare professional.1 This is concerning, as individuals with ostomies are trying to cope and manage their peristomal skin problems as part of their day-to-day life.

Onset of PSCs and risk factors

PSCs can be caused by peristomal irritant contact dermatitis, where there is prolonged exposure of the skin to ostomy effluent.2 The onset of PSCs immediately after surgery is reported to occur between 21 and 64 days.3,4 This contact dermatitis is categorised as Peristomal Moisture Associated Dermatitis (PMASD). Rates of PSCs following ostomy surgery have also been reported in the ranges of 10–70%.5

The etiology of PSCs is multifactorial, involving aspects related to the stoma and surgical procedure, the topography around the stoma site, and individual patient characteristics. An understanding of these risk factors is essential for the prevention and effective management of these complications. Ileostomies are known to be linked to a higher incidence of PSCs, primarily due to the irritating nature of liquid fecal effluent on the skin.2 Additionally, emergency stoma procedures, especially those conducted without pre-operative marking of the ostomy site, heighten the risk of PSCs due to potential issues with stoma placement and appliance fit, which can lead to effluent skin exposure.2 Obesity not only potentially impacts the profile of the stoma, leading to flat or retracted stomas, but also affects the peristomal topography.

The risk of developing PSCs is significantly amplified by the presence of creases and fat folds around the stoma, which can undermine the ostomy system’s seal, causing leakage and skin irritation.16 Factors such as gender, body mass index (BMI), age, and underlying health conditions also influence the likelihood of experiencing PSCs.2 Females and individuals with obesity face a greater risk, while the risk interestingly diminishes with age, indicating a higher vulnerability among younger patients.2

Certain comorbidities can predispose a person with an ostomy to experience a PSC. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is associated with immune or autoimmune disorders and diabetes is a risk factor for early post-operative peristomal dermatitis.4 Patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy further elevate the risk by compromising skin integrity and healing.2 Bacterial or fungal infections and sensitivities to ostomy products are additional contributors to PSC development.4 The duration of stoma ownership can impact the risk for peristomal skin complications PSCs, which suggests that patients with a longer history of living with a stoma are less likely to experience severe PSCs.16 The likely reason behind this is the improvement in stoma management skills over time. This improvement underscores the importance of using a proactive approach with ostomy barrier selection to help prevent PSCs early on after stoma creation. Such an approach aims to reduce the risk of PSCs effectively. Tailoring prevention and treatment strategies to each patient’s specific needs, considering their stoma type and profile, peristomal topography, and individual risk factors, is crucial. By being cognisant of these diverse contributing factors, healthcare providers can offer better support to stoma patients, potentially lowering the occurrence and severity of PSCs, thereby enhancing their overall quality of life.

The impact on Quality of Life (QOL)

Damage to the peristomal skin can affect the overall wellbeing and QOL of people with stomas.6 It can also influence adaptation to living with a stoma, increase the technicalities of stoma care, and impact their psychological adjustment to body changes.7 Nichols and Inglese explored the quality of life burden of peristomal skin complications in the population of people with ostomies.8 QoL was assessed with the Short Form Health Survey–36 Questions, Version 2 (SF–36v2) which is a validated tool designed to measure overall health status and quality of life across eight domains representing physical function and mental health. The authors investigated the relationship between PSC severity (mild, moderate, and severe) and the Physical Component Summary (PCS) of the SF-36v2 which provided a summary measure of an individual’s overall physical health status (such as physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, and general health perceptions). Over 2200 individuals with ostomies were surveyed: 1230 males with an average age of 65 years and 1030 females with an average age of 62 years. The majority of patients had an ileostomy (44%), followed by colostomy (40%), urostomy (13%), and multiple or unknown stomas (3%). Median stoma durations ranged from 28–62 months. The authors found that individuals with severe PSCs have significantly lower QoL than those with healthy intact skin (score of 66 vs 81, respectively, where zero represents absolute poorest QoL and 100 absolute best). The authors also found that individuals with greater physical limitations (i.e. lower PCS scores) were more likely to have lower (poorer) QoL. Their findings highlight that successful PSC treatment not only offers clinical benefits, but also QoL benefits..

The economic burden

Several studies point to the increasing cost of managing PSCs. The economic burden of experiencing PSCs was studied at two large US hospital systems.4,17 Both studies found that people with ostomies who developed PSCs had longer hospital stays (4–8 days longer) and were more likely to be readmitted within 120 days post-surgery (14–20% greater rate of readmission). Furthermore, patients with PSCs incurred greater cumulative health care costs over the 120 day post-surgery period compared with those who did not develop PSCs ($8000–$80,000). Martins et al., in the United Kingdom reported a range from GBP £106.29 to GBP £618.69 to treat mild to severe PSCs.9 Similarly, Meisner et al., in France, estimated the episodic treatment costs of severe cases of PSCs to be 2–5 times greater compared to mild cases (ranging from EUR €18.63 to EUR €195.82).10

The impact on the clinicians’ time

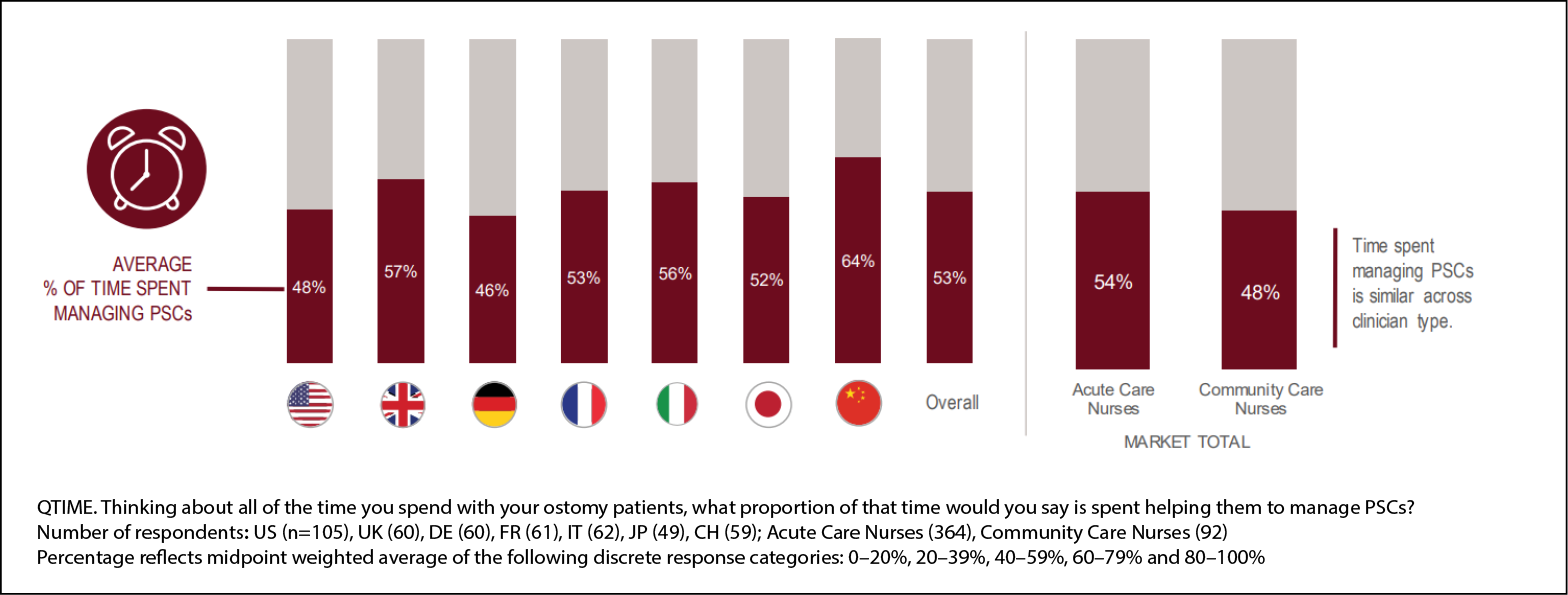

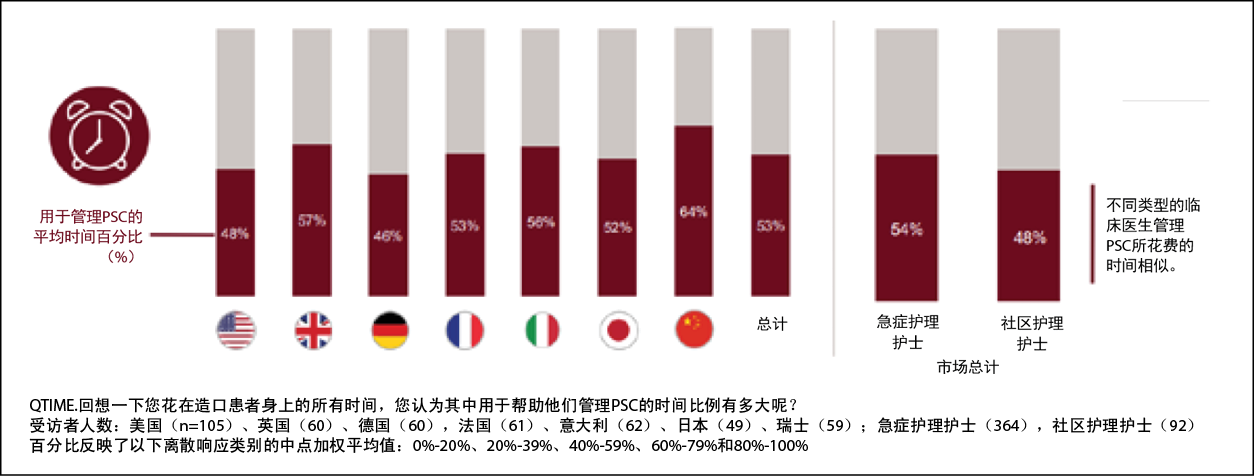

Managing PSCs can also contribute to an increasing workload for stoma care nurses. In a global survey of 456 nurses working within stoma care from seven different countries, it was found that 53% of nursing time with ostomy patients was spent managing PSCs (see Figure 1). This finding was consistent across acute care and community nurses.11 The remainder of stoma care nurses’ time was occupied with typical responsibilities including patient and staff education, pre-operative counseling, stoma marking, selection of appropriate products and discharge planning.

Figure 1. Nearly 50% of clinicians’ time with their patients is spent on managing PSCs11

The evidence

The benefits of using more compressible (soft) convex barriers as part of ostomy care were investigated across four global product evaluations.12 All patients included in these evaluations were asked to use this type of convex skin barrier instead of the flat ostomy barriers they typically wore. For each patient, clinicians collected baseline demographic information prior to use including ostomy type, stoma duration, and typical ostomy product use.

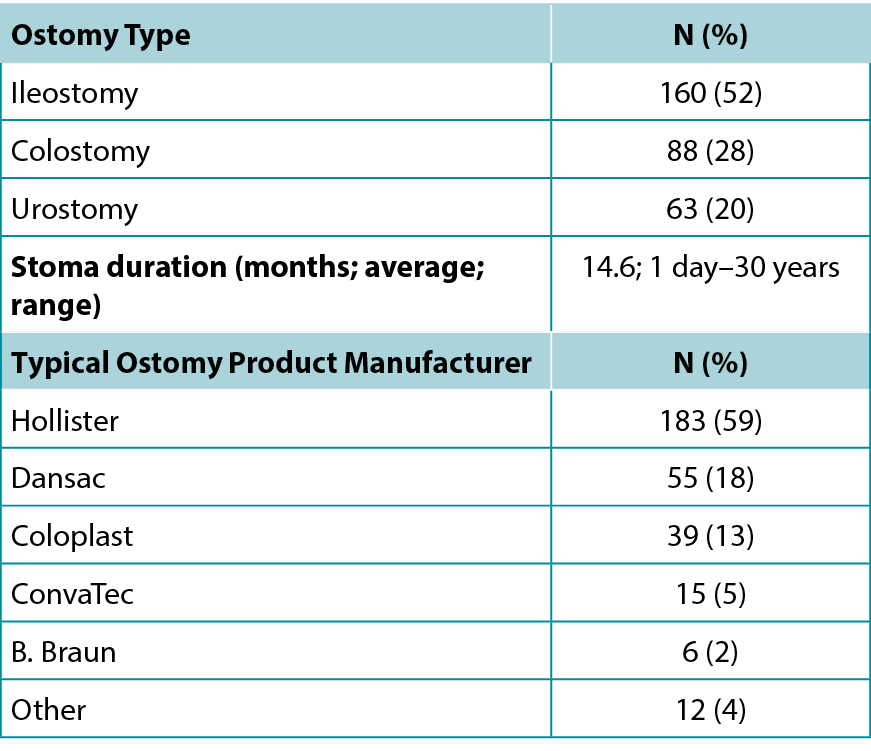

In this study, approximately 300 patients residing in over ten countries participated across four product evaluations. Nearly half of the patients were living with an ileostomy (52%), followed by individuals with a colostomy (28%), and urostomy (20%). Stoma duration ranged from 1 day to 30 years with an average of 15 months. Prior to using the more compressible convex skin barriers, patients used a wide range of flat ostomy systems from various manufacturers (including Hollister, Coloplast, Dansac, and ConvaTec). Table 1 provides a demographic summary of these variables.

Table 1: Demographic summary of patients

Clinicians were not provided any instruction as to which patients could use these barriers, including duration with ostomy prior to use, nor were they given instruction as to product wear-time, as well as which (if any) ostomy accessories to prescribe. Patient management was left entirely to clinician discretion and their standard of care. Furthermore, there were no restrictions on the state of peristomal skin (i.e., all peristomal skin conditions were eligible to participate). Lastly, all ostomy product manufacturers could participate. Accordingly, these product evaluations represent a very diverse and real-world population in which the impact of the more compressible skin barriers on ostomy care was assessed.

Of primary interest in the evaluation was the condition of peristomal skin prior to and following the use of convex skin barriers. Peristomal skin condition was assessed via two methods: Firstly, using an ostomy skin assessment tool that measured: discolouration, erosion and tissue overgrowth (DET).9 The DET assessment score is a validated clinician reported measurement. The score ranges from zero (no PSC) to 15 (severe PSC). The DET score can further be classified into PSC categories as follows: No PSC (score of 0), Mild PSC (score between 1 and 3), Moderate PSC (score between 4 and 6), and Severe PSC (score of 7 or greater).9 Secondly, clinicians were asked to rate the condition of the peristomal skin after using the more compressible skin barriers on a 5-point Likert scale from “much worse” to “greatly improved”. Due to the differing objectives of the four product evaluations, DET assessment was available for only two of the four evaluations; however, the Likert scale assessment was captured across all four.

Secondary outcomes of interest included changes in ostomy product utilisation, clinician satisfaction with various attributes of the more compressible barriers, and clinician likelihood to recommend continued use of these skin barriers to their patients. Wear-time prior to and following use of convex barriers was captured for two product evaluations. To estimate ostomy pouch utilisation, pre-evaluation and post-evaluation wear-times were converted to daily pouch utilisation. Daily usage was calculated by converting product wear-time into daily use (for example, wear-time of one day was recorded as use of one barrier per day, wear-time of two days was recorded as half a barrier per day, etc.). Patients who changed their pouches more than once daily were assumed to use two pouches per day. Patients who changed their pouches every seven days or longer were assumed to have a wear time of 10 days (i.e., to use of one tenth of a barrier per day). As a final step, for ease of interpretation, daily usage was converted to monthly usage (assuming 30 days per month).

As the focus of this article is to discuss the benefits of using more compressible convex skin barriers as part of ostomy care, results from all four product evaluations have been aggregated where possible. For the instances where outcomes were not available across all product evaluations (namely, DET score and ostomy product utilisation), this has been noted. Product evaluation data has been summarised using standard descriptive statistics (i.e., average, minimum, and maximum for numeric outcomes; counts and percentages for categorical outcomes). Statistical testing of changes in DET scores was performed via a paired t-test.

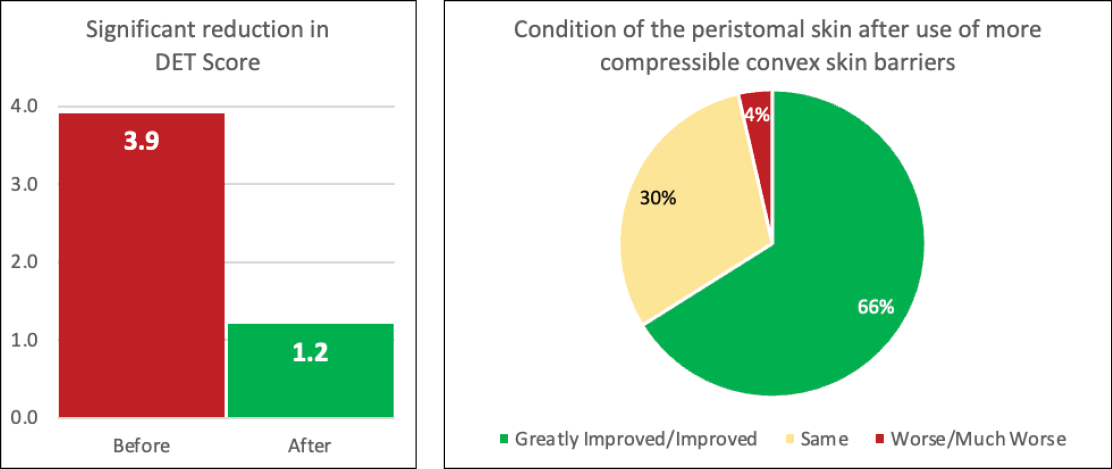

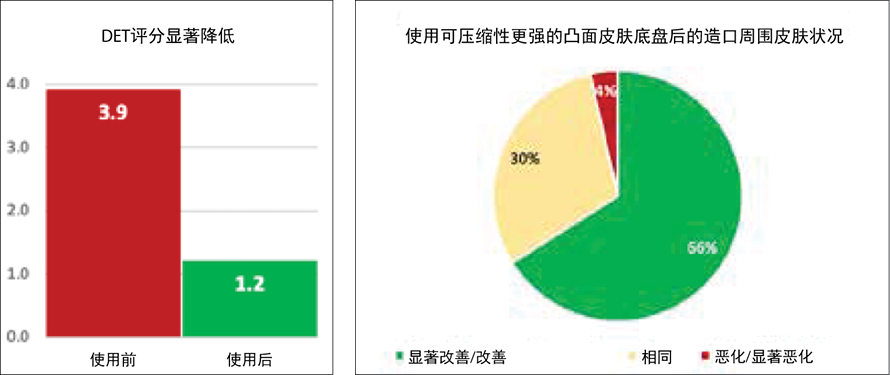

With respect to changes in PSC, use of the more compressible convex skin barriers as part of ostomy care resulted in significant improvements to the patients’ peristomal skin condition. In the two evaluations in which the DET tool was used, DET score significantly improved by 2.7 points (from 3.9 to 1.2, p<0.0001). Furthermore, clinicians were asked to rate the change in peristomal skin condition after use of convex skin barriers. Across all four evaluations, clinicians reported the peristomal skin improved or greatly improved for 66% of their patients, remained the same in 30% of patients, and only worsened for 3% of patients (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Significant improvement in peristomal skin condition after use of more compressible convex skin barriers

Significant benefits of using convex skin barriers with greater compressibility as part of ostomy care were also found in ostomy product utilisation. Patients were found to use significantly fewer skin barriers after switching from flat skin barriers. Monthly utilisation decreased from on average 34 flat skin barriers per month to 21 convex skin barriers per month (n=178; p<0.001). This reduction in utilisation was due to patients experiencing increased wear times with their more compressible convex skin barriers.

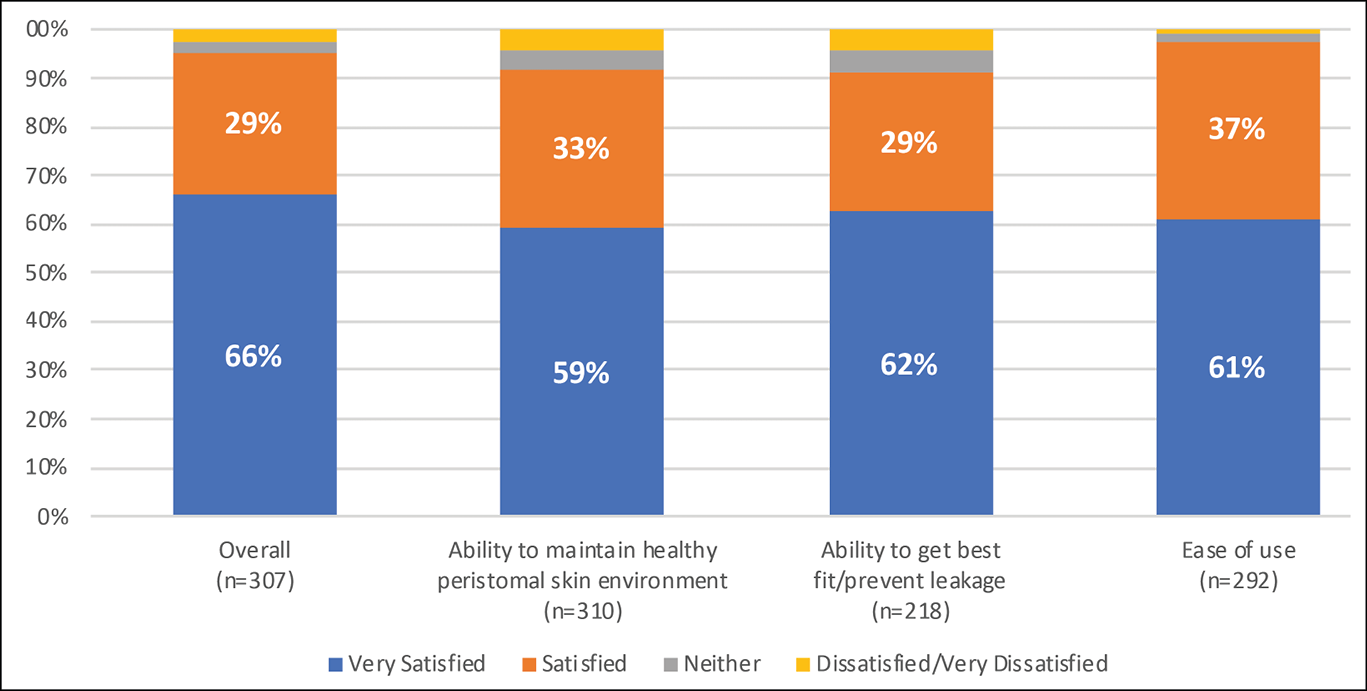

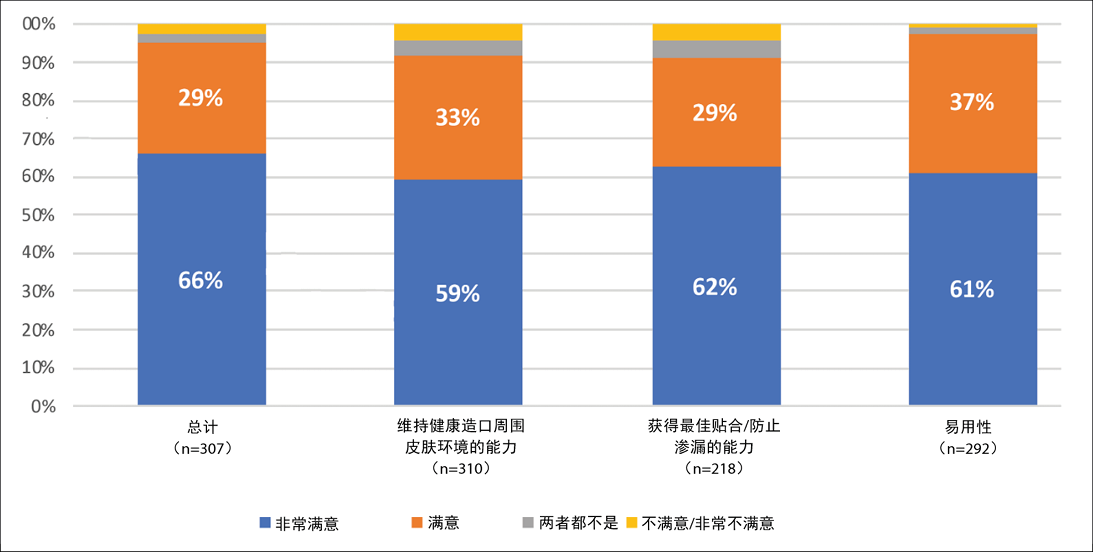

Clinician satisfaction with these skin barriers was also very positive with an overall satisfaction rate of 95%. Additionally, clinicians were satisfied with the convex barriers’ ability to maintain a healthy peristomal skin environment (92%), ability to get a best fit/prevent leakage (91%), and the barriers’ ease of use (98%) (see Figure 3). With respect to continued use, clinicians reported being likely or very likely to recommend continued use of the more compressible convex skin barriers for 89% of their patients.

In summary, these product evaluations suggest that using more compressible convex skin barriers as part of ostomy care provides significant benefit to patients in terms of improved peristomal skin health, reduced ostomy product utilisation, and positive clinician experience.

Figure 3. Very positive clinician satisfaction with more compressible convex skin barriers

The solution

In the ever-evolving landscape of healthcare, optimising patient comfort and well-being throughout the continuum of care is paramount. Since the introduction of more flexible and compressible convex product options – evidence continues to build supporting the use of convex products earlier in the patient’s journey and across various healthcare settings. From acute facilities to home health and beyond, the range of convex options offers advantages that positively impact patients and caregivers alike. As ostomy specialists, we should challenge ourselves to adopt new and innovative products and services along with the entire journey of the person with an ostomy: from the surgical table to living daily life with stoma.

Soft convexity refers to the use of compressible, flexible materials and designs in ostomy pouching systems and come in both one and two-piece options. Unlike their traditional rigid counterparts, this type of convex product adapts to the body’s contours, providing a snug yet comfortable fit. This adaptability plays a pivotal role in helping prevent leakage, achieving adequate flexible tension, and promoting skin integrity, particularly crucial for individuals with complex abdominal topography.

To help better define and standardise the different stages of the patient journey, Colwell and colleagues13 published a national consensus article and reached consensus on three post-operative time periods being: 1) the immediate postoperative period (0–8 days); 2) the postoperative period (9–30 days); and 3) the transition phase (31–180 days). In addition to defining these postoperative periods, Colwell and colleagues published a consensus statement that encourages and supports the use of convexity throughout any of these periods. The consensus statement reads “a convex pouching system can be safely used regardless of when the stoma was created.” It has been common practice in the past to avoid using convexity immediately after surgery due to the perceived risk of mucocutaneous separation. However, this concern has been without supportive evidence.14 With these new consensus statements, clinicians are encouraged to use flexible, more compressible convex products immediately out of the operating room to help improve the fit of the pouching system. Some clinicians are now opting to use these types of products within the operating room and removing flat products as the postoperative pouching system based on this newer evidence.15

Evidence continues to build, encouraging clinicians caring for people with ostomies to use more compressible convex products immediately after surgery, discharge to home with them, and encourage continued use while caring for themselves at home. Most abdominal topographies are not flat once the patient is at home and active, which poses the question, why should a flat barrier be the first go-to solution? Given the high prevalence of PSCs and their impact on QoL, the increased economic burden, and the clinicians’ additional time taken caring for patients with PSCs, we must continue to challenge current clinical practices and provide solutions to ensure healthy peristomal skin using evidence-based principles. Based on all the newer evidence, it does appear that the world is no longer flat.

Conflict of interest

The authors are employees of Hollister Incorporated.

Funding

Apart from being employees of Hollister, the authors received no funding for this paper.

告别平面时代

Colleen Drolshagen, Renee Malandrino, Jessica Simmons, George Skountrianos, Wil Walker

DOI: 10.33235/wcet.44.3.sup.s6-10

摘要

在造口护理专业中,支持有关处方产品使用的临床决策的证据相对匮乏。造口护理中的许多临床决策往往基于临床医生的经验,或是基于多年来形成却无证据支撑的教导与信念。目前,已有丰富多样的证据支持临床医生在患者早期阶段使用凸面装置,尤其是可压缩性较强的类型(软)凸面产品。

本文回顾了造口护理中使用更多可压缩底盘的最新证据,这对于临床医生管理患者而言是一个相对较新的手段。分析了支持这些产品早期使用以实现更牢固的皮肤密封并改善患者结局(相较于使用平面底盘)的数据。

引言

起初,临床医生或许会依赖其所接受的教育、导师指导、口碑以及习惯来塑造他们对造口患者的护理方式。如今,临床医生可以依靠大量的证据来指导并支持他们的实践。造口周围皮肤并发症(PSC)的预防和治疗一直是造口护理护士关注的重点,因为PSC会影响患者的生活质量、延长住院时间,并加重患者和医疗体系的经济负担。目前已有最新的证据支持在患者早期使用具有可压缩性和柔韧性特征的凸面皮肤底盘,以帮助预防和管理PSC。本増刊第2部分介绍了这些特征及描述词的发展情况,以及它们如何相互作用以帮助实现可靠的皮肤密封。在本文中,我们提供了临床证据,强调了软凸面装置的有益使用及其对造口周围皮肤健康、生活质量以及PSC管理的经济和临床负担的影响。这些证据着重强调了在患者治疗过程中尽早采用软凸面装置的必要性。

挑战

尽管手术技术不断改进(例如机器人腹腔镜手术),术前进行造口部位标记,全球专业造口护理组织(如WOCN协会、ASCN等)推出最佳实践指南,行业在产品方面不断创新(如注入皮肤底盘)以及新产品持续改进(如推出柔韧性、可压缩性更强的凸面皮肤底盘),人们或许会认为PSC的数量理应在减少。然而,在一项针对13个国家4235例造口术患者的跨国调查中,4227例患者里有73%报告在过去六个月内出现了造口周围皮肤并发症(PSC),而仅有31%的受访者向造口护理护士或医疗保健专业人员寻求帮助。1这表明,造口患者正在努力应对和管理他们日常生活中的造口周围皮肤问题。

PSC的发病和风险因素

PSC可由造口周围刺激性接触性皮炎引起,皮肤长时间接触造口排泄物。2据报道,术后立即出现PSC的时间为21至64天。3,4这种接触性皮炎被归类为造口周围潮湿相关性皮炎(PMASD)。据报道,造口术后PSC的发生率在10%-70%。5

PSC的病因呈现多因素特性,涉及造口及手术过程、造口周围的形态以及患者的个体特征等方面。了解这些风险因素对于预防和有效管理这些并发症至关重要。众所周知,回肠造口术的PSC发病率较高,这主要是由于液体粪便排泄物对皮肤具有刺激性。2此外,紧急造口手术,尤其是术前未对造口部位进行标记的手术,也会因造口放置和器具贴合的潜在问题导致皮肤接触排泄物,进而増加PSC的风险。2肥胖不仅可能影响造口的轮廓,导致造口扁平或内陷,还会影响造口周围的形态。

造口周围存在皱褶和脂肪褶皱,会破坏造口系统的密封性,造成渗漏和皮肤过敏,从而大大増加了PSC的发病风险。16性别、体重指数(BMI)、年龄和潜在的健康状况等因素也会影响发生PSC的可能性。2女性和肥胖患者面临的风险更大,而有趣的是,风险会随着年龄的増长而降低,这意味着年轻患者更容易发生PSC。2

某些合并症可能会导致造口患者经历PSC。造口周围坏疽性脓皮病与免疫或自身免疫性疾病存在关联,糖尿病是术后早期造口周围皮炎的一个危险因素。4接受化疗或放疗的患者的皮肤的完整性和愈合受到影响,导致患病风险进一步増加。2细菌或真菌感染以及对造口产品的敏感性也是引发PSC的原因之一。4拥有造口的时间长短会影响造口周围皮肤并发症PSC的风险,这表明造口生活史较长的患者发生重度PSC的可能性较小。16其背后的原因可能是随着时间的推移,患者的造口管理技能有所提升。这一改进凸显了积极选择造口底盘的重要性,有助于在造口创建后的早期预防PSC。这种方法旨在有效降低PSC的风险。考虑到造口类型和外形、造口周围形态以及个人风险因素,根据每位患者的具体需求定制预防和治疗策略至关重要。通过了解这些不同的诱发因素,医疗服务提供者可以为造口患者提供更好的支持,从而可能降低PSC的发生率和严重程度,进而提高他们的整体生活质量。

对生活质量(QOL)的影响

造口周围皮肤的损伤会影响造口患者的整体健康和QOL。6它还会影响患者对造口生活的适应程度,増加造口护理的技术难度,并影响他们对身体变化的心理调整。7Nichols和Inglese研究了造口术人群中造口周围皮肤并发症的生活质量负担。8QoL采用健康调查简表-36个问题,第2版(SF-36v2)进行评估,这是一种经过确认的工具,旨在衡量总体健康状况和生活质量,涵盖代表身体功能和精神健康的八个领域。作者对造口周围皮肤并发症(PSC)的严重程度(轻度、中度和重度)与SF-36v2量表中的躯体健康总评(PCS)之间的关系进行了研究。PCS是对个人整体身体健康状态(如身体功能、因身体健康问题而导致的角色限制、身体疼痛和一般健康感知)的总结性测量。对2200多例造口患者进行了调查:男性1230例,平均年龄65岁;女性1030例,平均年龄62岁。大多数患者接受了回肠造口术(44%),其次是结肠造口术(40%)、尿道造口术(13%)和多处或未知造口术(3%)。造口持续时间中位数为28-62个月。作者发现,患有重度PSC的个体的QoL明显低于皮肤健康完整的个体(评分:66 vs 81,其中0代表QoL最差,100代表QoL最佳)。作者还发现,身体受限程度越高(即PCS评分越低)的个体,其QoL越低(越差)。其研究结果表明,成功治疗PSC不仅能带来临床益处,还能提高QoL。

经济负担

一些研究表明,PSC的管理成本越来越高。我们在美国两家大型医院系统中研究了PSC所带来的经济负担。4,17两项研究均发现,患PSC的造口患者住院时间更长(4-8天),更有可能在术后120天内再次入院(再次入院率増加14%-20%)。此外,与未出现PSC的患者相比,出现PSC的患者在术后120天内的累计医疗费用更高($8000–$80,000)。据英国的Martins等人报告,治疗轻度至重度PSC的费用从GBP Åí106.29到GBP Åí618.69不等。9同样,法国的Meisner等人估计,与轻度病例相比,重度PSC病例的偶发治疗费用要高出2-5倍(从EUR €18.63到EUR €195.82不等)。10

对临床医生时间的影响

管理PSC也会増加造口护理护士的工作量。在对来自7个不同国家的456例造口护理护士进行的一项全球调查中发现,护理造口患者的时间中有53%花在了管理PSC上(见图1)。这一发现适用于急症护理和社区护理护士。11造口护理护士的其余时间用于履行典型职责,包括患者和员工教育、术前咨询、造口标记、选择合适的产品和出院计划。

图1.临床医生与患者接触的时间有近50%都花在了管理PSC上11

证据

四项全球产品评价研究了在造口护理中使用可压缩性(柔软)更强的凸面底盘的益处。12所有参与评价的患者都被要求使用这种凸面皮肤底盘,而不是他们通常使用的平面造口底盘。对于每例患者,临床医生在使用之前收集了基线人口统计学信息,包括造口类型、造口持续时间和典型造口产品使用情况。

在这项研究中,大约有300例居住在十多个国家的患者参与了四项产品评价。近一半的患者接受了回肠造口术(52%),其次是结肠造口术(28%)和尿道造口术(20%)。造口持续时间从1天到30年不等,平均为15个月。在使用可压缩性更强的凸面皮肤底盘之前,患者使用不同制造商(包括Hollister、Coloplast、Dansac和ConvaTec)生产的各种平面造口系统。表1提供了这些变量的人口统计学汇总结果。

表1:患者的人口统计学数据汇总

未向临床医生提供任何指导,说明哪些患者可以使用这些底盘,包括使用前造口的持续时间,也未就产品的佩戴时间以及开具哪些(如有)造口配件处方提供指导。患者的管理完全由临床医生自行决定,并按照他们的标准进行护理。此外,未对造口周围皮肤状态施加任何限制(即所有造口周围皮肤条件均可参与)。最后,所有造口产品制造商均可参与。因此,这些产品评价代表了一个非常多样化且真实的群体,在这个群体中评估了可压缩性更强的皮肤底盘对造口护理的影响。

评估的主要关注点是使用凸面皮肤底盘前后造口周围皮肤的状况。通过两种方法评估造口周围的皮肤状况:首先,使用造口皮肤评估工具测量:变色、糜烂和组织过度生长(DET)。9DET评估分数是经确认的临床医生报告的测量工具。评分范围为0(无PSC)至15(重度PSC)。DET评分可进一步划分为以下PSC类别:无PSC(0分)、轻度PSC(1-3分)、中度PSC(4-6分)和重度PSC(7分或更高)。9其次,要求临床医生对使用可压缩性更强的皮肤造口底盘后的造口周围皮肤状况进行评分,评分采用李克特5级评分法,从“显著恶化”到“显著改善”不等。由于四次产品评估的目标不同,四次评估中只有两次进行了DET评估;然而,李克特量表评估涵盖了所有四个方面。

次要结局包括造口产品使用量的变化、临床医生对可压缩性更强的底盘的各种特征的满意度,以及临床医生向其患者推荐继续使用这些皮肤底盘的可能性。在两项产品评估中,记录了使用凸面装置前后的佩戴时间。为了估算造口袋的使用量,将评估前和评估后的佩戴时间转换为造口袋的每日使用量。每日使用量的计算方法是将产品的佩戴时间换算成每日使用量(例如,一天的佩戴时间记录为每天使用一个底盘,两天的佩戴时间记录为每天使用半个底盘,诸如此类)。假定每天更换造口袋超过一次的患者每天使用两个造口袋。假定每七天或更长时间更换造口袋的患者的佩戴时间为10天(即每天使用十分之一的底盘)。最后,为便于解释,将每日使用量转换为每月使用量(假设每月使用30天)。

由于本文的重点是讨论使用可压缩性更强的凸面皮肤底盘作为造口护理的一部分所带来的益处,因此在可能的情况下对所有四种产品的评估结果进行了汇总。对于无法获得所有产品评估结局(即DET评分和造口产品使用量)的情况,已予以注明。产品评估数据采用标准的描述性统计(即数字结局采用平均值、最小值和最大值;分类结局采用计数和百分比)进行汇总。通过配对t检验对DET评分变化进行统计检验。

关于PSC的变化,使用可压缩性更强的凸面皮肤装置作为造口护理的一部分,显著改善了患者的造口周围皮肤状况。在使用DET工具的两次评估中,DET评分显著提高了2.7分(从3.9分提高到1.2分,p<0.0001)。此外,还要求临床医生对使用凸面皮肤底盘装置后造口周围皮肤状况的变化进行评分。在所有四次评估中,临床医生报告称66%的患者造口周围皮肤有所改善或大有好转,30%的患者保持不变,仅3%的患者造口周围皮肤状况恶化(见图2)。

图2.使用可压缩性更强的凸面皮肤底盘装置后,造口周围皮肤状况明显改善

在造口产品使用方面也发现,使用可压缩性更强的凸面皮肤底盘装置作为造口护理的一部分具有显著的益处。研究发现,患者在改用平面皮肤底盘后,皮肤底盘的使用量明显减少。每月使用量从平均每月34个平面皮肤底盘减少到21个凸面皮肤底盘(n=178;p<0.001)。使用量下降的原因是,患者使用更易压缩的凸面皮肤底盘装置的时间延长了。

临床医生对这些皮肤底盘的满意度也非常高,总体满意率达到95%。此外,临床医生对凸面装置维持健康造口周围皮肤环境的能力(92%)、获得最佳贴合/防止渗漏的能力(91%)以及底盘的易用性(98%)表示满意(见图3)。在继续使用方面,89%的临床医生表示有可能或非常有可能建议患者继续使用可压缩性更强的凸面皮肤底盘装置。

总之,这些产品评估表明,使用可压缩性更强的凸面皮肤底盘装置作为造口护理的一部分,在改善造口周围皮肤健康、减少造口产品使用量和临床医师的积极体验方面,可为患者带来显著益处。

图3.临床医生对可压缩性更强的凸面皮肤底盘装置非常满意

解决方案

在不断发展的医疗保健领域,在整个护理过程中优化患者的舒适度和福祉至关重要。自推出柔韧性、可压缩性更强的凸面装置产品以来,越来越多的证据表明,在患者就医的早期和各种医疗机构中使用凸面装置产品是可行的。从急症设施到家庭保健及其他领域,各种凸面装置都具有对患者和护理人员产生积极影响的优势。身为造口专业人士,我们理应挑战自我,在造口术患者的整个历程中采用新的创新产品与服务,自患者躺在手术台上的那一刻开始,持续贯穿到造口术后的日常生活当中。

软凸面装置是指在造口装置中使用可压缩的柔性材料和设计,有一件式和两件式两种可供选择。与传统的同类硬质产品不同,这种凸面产品能够适应人体轮廓,提供贴合而舒适的佩戴体验。这种适应性在帮助防止渗漏、获得足够的柔性张力和促进皮肤完整性方面发挥着关键作用,这对于腹部形态复杂的人来说尤为重要。

为了帮助更好地定义和规范患者旅程的不同阶段,Colwell及其同事13发表了一篇全国性的共识文章,并就术后的三个时间段达成了共识:1)术后即刻(0-8天);2)术后阶段(9-30天);3)过渡阶段(31-180天)。除了定义这些术后时期外,Colwell及其同事还发表了一份共识声明,鼓励并支持在上述任何时期使用凸面装置。共识声明中写道:“无论造口是何时创建的,都可以安全地使用凸面造口装置”。由于认为存在皮肤黏膜分离的风险,过去通常的做法是避免在手术后立即使用凸面装置。然而,这种担忧并没有得到支持性的证据。14通过这些新的共识声明,我们鼓励临床医生在手术室外立即使用柔韧性、可压缩性更强的凸面产品,以帮助改善造口装置的贴合度。现在,一些临床医生选择在手术室内使用这类产品,并根据这些新证据从术后造口装置中摒弃了平面产品。15

不断积累的证据鼓励护理造口患者的临床医生在术后立即使用更多可压缩的凸面装置,出院回家时随身携带,并鼓励患者在家中自我护理时继续使用。一旦患者在家活动,大多数腹部形态都不平坦,这就提出了一个问题:为什么要把平面底盘作为首选解决方案?鉴于PSC的高发病率及其对QoL的影响、经济负担的増加以及临床医生照顾PSC患者所花费的额外时间,我们必须继续挑战当前的临床实践,并提供解决方案,利用循证原则确保造口周围皮肤的健康。所有较新的证据表明,我们即将告别平面时代。

利益冲突声明

作者为Hollister Incorporated的员工。

资助

作者除身为Hollister的员工外,并未因本文而获得任何其他资助。

Author(s)

Colleen Drolshagen1*

Principal Clinical Scientist, Global Clinical Affairs

Email colleen.drolshagen@hollister.com

Renee Malandrino1

Principal Clinical Scientist, Global Clinical Affairs

Jessica Simmons1

Senior Clinical Scientist, Global Clinical Affairs

George Skountrianos1

Health Economics Manager Value Demonstration,

Global Market Access

Wil Walker1

Clinical Resource Manager, US Ostomy Marketing

1Hollister Incorporated, Libertyville, Illinois, USA

* Corresponding author

References

- Voegeli D, Karlsmark T, Eddes EH, Hansen HD, Zeeberg R, Håkan-Bloch J, Hedegaard C. Factors influencing the incidence of peristomal skin complications: evidence from a multinational survey on living with a stoma. Gastrointestinal Nurs. 2020;18(Sup4), S31–S38.

- D’Ambrosio F, Pappalardo C, Scardigno A, Maida A, Ricciardi R, Calabro E. Peristomal complications in ileostomy and colostomy patients: What we need from a public health perspective. Int J Env Res and Pub Health. 2023;20(1):79.

- Ayik C, Ozden D, Cenan D. Ostomy complications, risk factors and applied nursing care: A retrospective descriptive study. Wound Manag Prevention. 2020;66(9):20–30. doi:10.25270/wmp.2020.9.2030.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad B, Inglese G, Eaves D, Oster G. Risk and economic burden of PSCs following surgery. JWOCN. 2019;46(2):

- 143–149.

- Colwell J, Ratliff C, Goldberg M, Baharestani M, Bliss D, Gray M, Kennedy-Evans K, Logan S. Black J. MASD part 3: Peristomal moisture-associated dermatitis and periwound moisture-associated dermatitis. JWOCN. 2011:38(5):541–553.

- Boyles A, Hunt S. Care and management of a stoma: Maintaining peristomal skin health. Br J Nurs. 2016:25(17): S14–S20.

- Burch J, Marsden J, Boyles A, Martin N, Voegli D, McDermott B, Maltby E. Keep it simple: peristomal skin health, quality of life and well-being. Best practices consensus document on skin health. Br J Nurs. 2021;60 (6 Supp 1):1–24.

- Nichols T, Goldstine J, Inglese G. A multinational evaluation assessing the relationship between peristomal skin health and health utility. Br J Nurs. 2019;28(5): Stoma supplement.

- Martins L, Ayello EA, Claessens I, et al. The ostomy skin tool: tracking peristomal skin changes. Br J Nurs. 2010;19(15):960, 932–934.

- Meisner S, Lehur PA, Morna B, Martins L, Jemec GBE. Peristomal skin complications are common, expensive and difficult to manage: A population based cost modeling study. PLoS.ONE;7(5):e37813.doi:10.1371/journl.pone.0037813

- Hollister Data on File, ref-02985, 2021. CL-000903.

- Hollister Data on File, ref-03805, 2024.

- Colwell J, Stoia Davis J, Emodi K, Fellows J, Mahoney M, McDade B, Porten S, Raskin E, Sims T, Norman H, Kelly MT, Gray M. Use of a convex pouching system in the postoperative period: A national consensus. J WOCN 2022;49(3):240–246.

- Hoeflok J, Kittscha J, Purnell P. Use of convexity in pouching: a comprehensive review. JWOCN. 2013;40(5):506–512.

- Hill R. Convexity today. WOCN WOC Talk. 2023. https://www.wocn.org/podcasts/bonus-ep-25-soft-convexity-in-the-operating-room/. Accessed April 2024.

- Salvadelena G, Colwell J, Skountrianos G, Pittman J. Lessons learned about peristomal skin complications: Secondary analysis of the ADVOCATE Trial. JWOCN. 2020;47(4): 357–363.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad BS, Inglese G, Lamerato L, Oster G. clinical and economic burden of peristomal skin complications in patients with recent ostomies. JWOCN. 2017;44(4):350–357.