Volume 43 Number 4

Patients’ experience in the unnecessary use of absorbent continence products: a small experiential qualitative study

Sandra Guerrero Gamboa, Angie Viviana Ariza Garzón

Keywords nursing, incontinence diapers, absorbent pads, life changing events, psychological wellbeing

For referencing Guerro Gamboa S & Ariza Garzón AV. Patients’ experience in the unnecessary use of absorbent continence products: a small experiential qualitative study. WCET® Journal 2023;43(4):13-19.

DOI

10.33235/wcet.43.4.13-19

Submitted 12 June 2023

Accepted 25 September 2023

Abstract

Objective To describe the lived experience of a small group of inpatients arising from the unnecessary use of absorbent continence products in a hospital in Bogotá, Colombia.

Method A qualitative and phenomenological study. Interviews were undertaken with consenting participants as well as participant observations until data saturation occurred. Subsequently, all data were transcribed and analysed based on Husserl’s Methodology to derive themes and categories of the phenomenon seen.

Subjects and setting A selective sample of seven continent people without previous use of absorbent continence products and with mild disability, according to the PULSES profile, were recruited from the internal medicine service of a high complexity hospital in Bogotá, Colombia.

Results As a result of the data analysis, five themes or categories arose: getting into an unknown world; looking for care; submitting to using an absorbent continence product; my body’s reaction to using an absorbent continence product; and adapting or trying to recover my independence.

Conclusions The lived experience of patients who were required to unnecessarily wear absorbent incontinence products while in hospital and the ensuing detrimental effect on their psychological and physical wellbeing are described. Health professionals, whilst under time and other constraints, need to understand the patients’ perspective and their desire to maintain independence with their elimination needs when in hospital. The unnecessary use of absorbent incontinence products is not best practice, is not economical healthcare, and it potentially has adverse effects on the environment.

Introduction

Absorbent pads or incontinence diapers are sanitary products that are used for personal hygiene in the presence of urinary or faecal incontinence. Correct use of these products contributes to the containment and absorption of urine and faeces1 by wicking fluids away from the skin2. Nevertheless, it is becoming apparent in some healthcare facilities that nurses are unjustifiably using these continence aids on continent people3. Even studies like Zisberg (2011) show the high tendency among hospital staff to use incontinence diapers in patients whose condition do not require such intervention4.

Diaper use in older adults is associated with multiple adverse outcomes. For example, studies have found that diaper use: negatively influences self-esteem and perceived quality of life4; may lead to urinary or faecal incontinence5; increases dependency to carry out day-to-day activities6; and leads to the appearance of moisture-associated skin injuries7–9 and pressure injuries or urinary tract infections10 that complicate the patients’ health status, or even cause their death11. The adverse effects impair the quality of the health system and generate financial impacts due to the additional costs and the increase in hospital stays for the treatment of the skin damage incurred3. Additionally, the use of absorbent pads generates waste that pollutes the ecosystem12,13, and they can also pose additional medical expenses for the patient and/or their family14,15. Furthermore, they generate an increased burden of care for health personnel and/or family members due to the time and effort spent on changing absorbent products, hygiene and skin care3.

Studies indicate that this practice is utilised due to a lack of assessment and nursing interventions, other than application of an incontinence pad16. A study by Zurcher et al. (2011) found that nursing records mentioned the use of absorbent products without documenting a prior assessment of urinary continence17. Other studies show that health personnel have beliefs that relate incontinence to ageing16 and the use of diapers as the only hygiene treatment for the elderly18. They also mention the low use of elimination intervention strategies such as scheduled urination in nursing homes, a strategy that has more benefits compared to diaper use since it maintains continence, and promotes mobility and independence15,19.

Although the literature describes many problems related to the wearing of unnecessary absorbent incontinence products, the effects associated with the quality of life and experiences of people have not been thoroughly studied. During her clinical duties, the researcher observed in diaper-wearing continent people feelings of revulsion, discomfort and dissatisfaction with the care provided. However, when examining the literature, few studies address these factors. One example is the study by Alves et al. (2013)18 that describes nurses’ perceptions of how users of diapers where there was no valid clinical indication for their use, evidenced mistrust, insecurity, stress, sadness and discomfort, among others. Study data is based only on the perception of nurses and does not document the patients’ perspective.

The rationale for the current study therefore was to further investigate, explain and share continent patients ‘lived experiences’ of having to wear incontinence diapers or absorbent pads when they wished to be toileted whilst being treated as inpatients within a high-complexity hospital in Bogotá, Colombia.

Methodology

Research methods

A qualitative research technique was used to interview patients about their feelings of having to use incontinence diapers or absorbent pads as opposed to being assisted to the toilet to maintain their current state of urinary or faecal continence. The following questions were asked of patients recruited to the study:

- How do you describe your experience when using a diaper?

- What feelings has the diaper use generated in you?

- What factors do you think influenced your experience regarding diaper use?

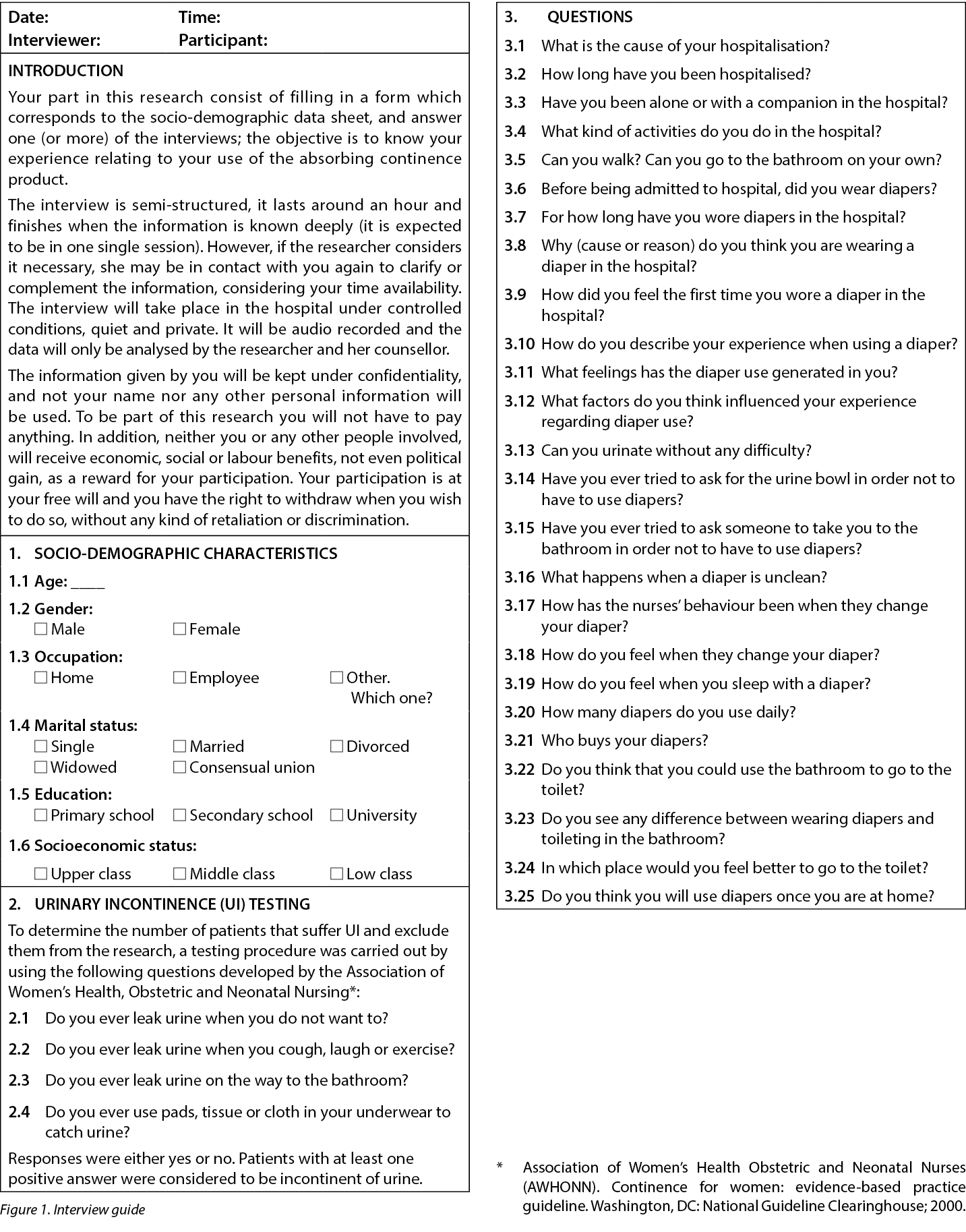

Data collection was carried out by pilot testing on two patients and was assessed using the Creswell criteria20 to confirm the operation of the interview guide (Figure 1) and the aspects that could be improved to incorporate them into the data collection process20.

The interviews were conducted by the researcher in a private place, and the data was collected via voice recordings and field notes that included information on non-verbal expressions20. During the session, the participant described their experience, additional questions were introduced to specify what they were reporting and, subsequently, the interview ended when data saturation was reached20.

Selection and recruitment criteria

Selection criteria included continent people without previous use of absorbent pads or incontinence diaper products and without disability or with a mild disability according to the PULSES profile.

Seven participants were selected and recruited from an internal medicine service of a high-complexity hospital in Bogotá, Colombia. Recruited patients were informed of the research study’s objectives, privacy and security measures and the option to withdraw at any moment without any compromise to clinical care provided. Written informed consent to participate in the study were obtained.

Sample size and data saturation

The sampling was theoretical (or purposeful) for the purpose of better understanding the issues central to the current study21. The interview was considered complete when the data collected described the phenomenon identified in the guiding questions and the total of interviews were adequate when data saturation occurred, that is to say, the data included enough information to replicate the study, no new information was being obtained in the interviews and further coding no longer deemed feasible22.

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed, stored and classified by a number to maintain patient anonymity. The tool used was ATLAS.ti program version 6.0 (2003–2010, ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin. Author: Dr Susanne Friese) for the organisation, coding and analysis of information23. Analysis was done according to Husserlian phenomenology since this allowed us to understand the lived experience of persons related to the phenomenon24. Fundamentally, this analysis directs nursing research away from personal preference, and directs it towards a purer return25, it allows us to know the phenomenon as it is lived by a person26 and produces an unbiased scientific knowledge that reinforces the principles and practices of nursing and contributes therefore to professional development27.

In the study, a constant immersion in the data was carried out in order to understand what is happening28. The researcher of this study constantly evaluated herself to neutralise preconceptions and not influence the object of study26. Based on participants’ statements, meaningful references, text excerpts or descriptors, and nominal codes, categories to describe the phenomenon were created. A second researcher was involved in validating data that was transcribed, contributing to the accuracy of the data process. Each resulting category was compared to the original descriptions for validation purposes.

Results

The study included seven continent people without a previous diagnosis of urinary or faecal incontinence and who had not previously used absorbent products or continence diapers. The average age of participants was around 74 years old and most were from a low socioeconomic background and had a low level of education. Upon further enquiry about reasons to use diapers, participants referred to having mobility difficulties to go to the bathroom, visual disability, dizziness, and alteration in lower extremities movements. All of them had a mild disability according to the PULSES profile and were able to go to the bathroom with assistance with walking or by using a walker device or a wheelchair.

From the data analysis, significant statements were identified, meanings were formulated and these were grouped in five common categories: getting into an unknown world; looking for care; submitting to using an absorbent continence product; my body’s reaction to using an absorbent continence product; and adapting or trying to recuperate my independence. Further descriptors and patient experiences under these categories are provided below.

Getting into an unknown world

This category expresses the transition the patient experienced when they were admitted as an inpatient to the hospital and how the admission affected their elimination pattern. At home, patients can go to the bathroom in an independent, private and peaceful way but the situation changes when they are admitted to hospital. Going to the bathroom while in hospital is difficult due to their health situation and that is why they seek the accompaniment of health personnel. However, as they do not find support in these people, the only option that they receive is to relieve themselves in the diapers.

A continent person with mobility problems attempting to go to the bathroom, secondary to visual impairment, reports:

While I was here, at the hospital, it was when I had to use the diaper… When I entered, they did not ask me if I wanted, they did it without asking, they told me: You need a diaper; you must wear it... and I said: Alright. Let’s do it... and since then I’ve been wearing the diaper. But it is better to go to the bathroom, it’s more hygienic, to go to the bathroom, I have to ask for help because I see shadows, sometimes they assist me, but other times they are busy with other patients and I have to wait – E6.

Looking for care

This category describes how these subjects tried to avoid diaper usage and decided to look for help to go to the bathroom. As provision of such assistance was not timely, and sometimes took hours, the patients’ capacity to contain urine or faecal elimination was limited, and a sense of urgency occurred. In the desire to contain elimination needs, they also expressed suffering, shame, resignation, discomfort, insomnia, abdominal pain and bloating. These sensations subsided after elimination. In this category a person describes:

I had a thrombosis. This whole side became paralyzed (points to the right side of the body), (...) I’m already using the walker... but still, I cannot go to the bathroom alone. The thing is that I’m afraid of falling… When I must go to the bathroom, I call them and tell them: take me to the bathroom! but sometimes they don’t have time... and (grunts)! (points to the abdomen and simulates pain). Last night, for instance, I had such horrible colic... it was because I asked them during two hours to come and take me to the bathroom and I was very hurried – E2.

Although patients tried to wait, eventually they reached a point where they could not resist the urge to eliminate. They then resigned themselves to excrete in the absorbent pad/incontinence diaper and experienced a momentary sense of relief.

Occasionally, the nursing team takes care of their urge to go to the bathroom on time. Someone mentions:

I have gone to the bathroom to relieve myself. Normally a nurse assists me. Yesterday, she took me to the bathroom, she helped me to sit and be comfortable... She is attentive; takes care of me; she always says: What do you want? What do I do? They all are very attentive; when they assist us, they do it with so much affection – E4.

Submitting to using an absorbent continence product

The category relates to those subjects who did not need to use diapers, but felt they ‘had’ to. They wanted to relieve themselves in the bathroom, but they did not receive any assistance despite insisting repeatedly to receive it. For that reason, they had to forgo their wants and decide to relieve themselves in absorbent pads/incontinence diapers. Over time, the patients stopped calling the nursing staff to be taken to the bathroom and they resigned themselves to wearing an absorbent pad/incontinence diaper. The patients feel at the mercy of the health personnel who have little time and are also experiencing a shortage of staff. As a result, this makes them feel restricted and vulnerable. The patients have made the following comments:

Well, I have to wear a diaper, but I don’t need it… wearing a diaper is uncomfortable, but this is what I had to do. Regardless, I like to go to the bathroom and try to find someone who helps me, they just don’t assist me – E1.

I feel like an impediment to wear a diaper; it doesn’t feel good… I feel dependent on the will of the people – E6.

My body’s reaction to using an absorbent continence product

This category describes the patients’ expressed and unpleasant feelings about wearing an absorbent continence product. They used terms such as: moisture; warmth, load; burning sensation; dirt, chafe or discomfort; and even the loss of sleep. Furthermore, they worried about expenses incurred by their families when they had to buy absorbent pads or incontinence diapers. Another issue they worried about was skin injuries due to diaper change delay. People made these comments about this category:

When I wear a diaper, I feel dirty… too warm; you try to sweat. Further, the diaper makes me feel annoyed, cold, wet; I feel bad. That’s why I take it off or I tell the nurse to change it for me. I can last for hours with the diaper wet... and sometimes that produces some kind of peeling, scorching… that is annoying – E6.

Now I am burned… because they took too long to change my diaper; I burn completely, that’s why they are putting ointment on – E7.

I feel that wearing a diaper alters my sleep. I feel uncomfortable and I can’t rest properly because of the dampness – E4.

I think buying diapers affects me financially… Sometimes my husband has no money for diapers, and he has to borrow some money, then he comes and buys them – E2.

Adapting or trying to recover my independence

The category refers to how either patients adopted to the habit of relieving themselves in the absorbent pad or incontinence products without a clinical diagnosis of incontinence or other physical or reason to do so, just because there is no nursing assistance to enable them to go to the toilet. Other people persisted in avoiding the use of incontinent devices and tried to recover their independence by doing activities that helped them to mobilise or even going by themselves to the bathroom, increasing falls and injury risks. Some people mentioned:

I don’t feel bad for wearing a diaper, one gets used to it… now I ask that they put the diaper on me… I like to go to the bathroom, but I ask to be placed (in the diaper) due laziness! – E6.

So when I go to the bathroom at least I walk a little bit, and also I kind of feel life as before. I want to go back to my old life, go to the bathroom, normal – E5.

I tried to go to the bathroom alone because sometimes assistants are busy with other patients. I always hit against walls because I do not see. Yesterday I went to the bathroom... they didn’t even notice it – E6.

Discussion

This small selective sample size qualitative study describes patients’ experience of having to use absorbent pads/incontinence diapers without a valid clinical indication for their use as a shocking experience. In this study the patients felt obliged to use these types of devices because they had no other option, which generated negative consequences on a physical and personal level that could have been avoided.

Studies like Zisberg (2011) show the high tendency among hospital staff to use incontinence diapers in patients whose condition does not require such intervention4. This is due to the shortage of personnel, the lack of time to build better patient care planning16, and the delegation of care to technical personnel without adequate supervision18. Within the hospital in which this study was held, a similar situation was found – nursing staff delegate the task of needs relating to elimination to the technician or ancillary staff and do not supervise the type of people who are being provided with diapers.

However, regardless of whether patients are continent or have the possibility of going to the bathroom with assistance, it is becoming increasingly common for health personnel to routinely use diapers for hygiene purposes in the elderly18 or people with functional disabilities15. This occurs because health personnel do not assess continence, they associate urinary incontinence with ageing18,29, and they believe that people with functional disabilities need to wear diapers15.

This study also observed that at home patients can go to the bathroom in an independent manner; however, this situation changes when they are admitted to hospital since the only option they are given is to relieve themselves in a diaper. This is not best practice since continent people should use the bathroom. According to studies, even semi-dependent patients should not use a diaper to relieve themselves. On the contrary, they need to go to the bathroom to help stimulate their mobility and independence15,30.

In this study the patients who felt an urge to go to the bathroom and needed nursing assistance to do so tried to resist the use of absorbent pads/incontinence diapers. However, as the hours went by without any nursing assistance, they had no other option but to give way and relieve themselves within the diapers. In the desire to contain elimination needs, they also expressed suffering, shame, resignation, discomfort, insomnia, abdominal pain and bloating. These sensations subsided after elimination. When searching the literature, no studies were found that describe in detail this resistance of continent patients to the use of a diaper. For this reason, the current study allowed a greater insight into patient experiences.

Furthermore, as outlined above, although patients tried to wait, eventually they reached a point where they could not resist the urge to eliminate. They then resigned themselves to excrete in the absorbent pad/incontinence diaper and experienced unpleasant sensations. They described discomfort and unpleasantness from being in prolonged contact with their faeces or urine. The feelings verbalised were ones of restlessness, frustration, hopelessness and in particular the loss of independence. They also felt uncomfortable with the sensation of humidity, heat and pressure in addition to effects on their skin such as burning and pain from dermatitis associated with incontinence. When examining the literature, few studies address these factors; however, some results are similar. One study is by Alves et al. (2013) that describes nurses’ perceptions of diaper users where there is no validated clinical indication for their use. The findings are distrust, insecurity, stress, sadness and discomfort, in addition to the loss of identity, dependency or fragility due the use of diapers18. In another study on the perception of hospitalised elderly people, they mention the feeling of discomfort, low self-esteem, revulsion, itching, pain, inefficiency, heat and motor restriction6.

After being exposed to these sensations, some patients adopt the habit of relieving themselves in the absorbent pad or incontinence products. The study of Zisberg (2011) says that, even among continent patients, diaper use may be “addictive,” at least in the short term, which may explain the behaviour of these patients4. On the other hand, other people persisted in avoiding the use of incontinent devices and tried to recover their independence by doing activities that helped them to mobilise or even going by themselves to the bathroom, increasing falls and injury risks.

The literature has similar results; however, there is little research, and this allows the current study to provide a greater insight into the patients’ experiences of being forced into using diapers unnecessarily. This practice exposes patients to potential skin damage and psychological trauma that can mean a problematic or longer recovery time31. People who are continent of urine seek nursing assistance to go to the bathroom and maintain their level of independence. However, this study found that on most occasions they do not get support from these people and the only option that they receive is to relieve themselves in the diapers.

In these cases, the absorbent pad is used unnecessarily and can be replaced by other methods. According to Jonasson et al. (2016), there is a need to move towards a more person-centred approach as far as possible16, using methods such as scheduled assistance when going to the bathroom to help to strengthen mobility, improve autonomy and independence30,32, and maintain health and wellbeing16.

For these methods to be implemented by hospital staff, a change in practice is necessary. A study by Bernard et al. (2020) outlines how nurse educator and administration support can contribute to reduce diapers use to improve the patient care experience. Nurse educators can teach proper toileting, explain how to assess the patients’ continence and how to use the patients’ toileting schedules, and select appropriate collection/containment devices. Also, administrative support contributes to the implementation of programs and protocols on best practices in continence care, restricts the use of absorbent pads, increases the availability of optional urinary/faecal containment devices and provides tools to support toileting, such as adequate facilities and nurses and physiotherapists trained in continence management33.

Conclusions

The results of the study show that the Colombian health system does not always respond efficiently to the clinical needs of patients with mild disabilities to maintain independence with urinary and faecal continence. The provision of assistance nursing was not timely and forced patients to wear diapers unnecessarily and involuntarily, which undermined self-confidence, patient safety, and caused physical and psychological consequences. There were also economic implications that affect the family and health institutions with the increase in treatment costs. This study shows how health institutions do not always consider physical and social functionality and the preference of users regarding their elimination needs, thereby generating dissatisfaction, discomfort, vulnerability and loss of dependency.

In this sense, phenomenological studies such as this one are a window for reflection and a path to achieve a better quality of care34. Health professionals, whilst under time and other constraints, need to understand the patients’ perspective and maintain independence regarding their elimination needs when in hospital. That is why individualised holistic care16 is needed to offer care beyond the usual care procedures, considering the priorities and elimination needs of patients.

Limitations

This research study had a very small theoretical sample size. Therefore, the results of the study should not be generalised to all health facilities. More research is needed on this phenomenon.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the study participants for their cooperation.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics statement

This study was endorsed by the Faculty of Nursing Ethics Committee, National University of Colombia: approval (021-18) and the Research Ethics Committee in health facility, approval (119/18).

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

La experiencia de los pacientes en el uso innecesario de productos absorbentes de continencia: un pequeño estudio cualitativo experiencial

Sandra Guerrero Gamboa, Angie Viviana Ariza Garzón

DOI: 10.33235/wcet.43.4.13-19

Resumen

Objetivo Describir la experiencia vivida por un pequeño grupo de pacientes hospitalizados derivada del uso innecesario de productos absorbentes de continencia en un hospital de Bogotá, Colombia.

Método Estudio cualitativo y fenomenológico. Se realizaron entrevistas con participantes que dieron su consentimiento, así como observaciones de los participantes hasta que se produjo la saturación de datos. Posteriormente, se transcribieron todos los datos y se analizaron basándose en la Metodología de Husserl para derivar temas y categorías del fenómeno observado.

Sujetos y entorno Se reclutó una muestra selectiva de siete personas continentes sin uso previo de productos absorbentes para continencia y con discapacidad leve, según el perfil PULSES, en el servicio de medicina interna de un hospital de alta complejidad de Bogotá, Colombia.

Resultados Como resultado del análisis de los datos, surgieron cinco temas o categorías: adentrarme en un mundo desconocido; buscar atención; someterme al uso de un producto absorbente de continencia; la reacción de mi cuerpo al uso de un producto absorbente de continencia; y adaptarme o intentar recuperar mi independencia.

Conclusiones Se describe la experiencia vivida por pacientes que tuvieron que llevar innecesariamente productos absorbentes para la incontinencia durante su estancia en el hospital y el consiguiente efecto perjudicial sobre su bienestar psicológico y físico. Los profesionales sanitarios, aunque con limitaciones de tiempo y de otro tipo, tienen que comprender la perspectiva de los pacientes y su deseo de mantener la independencia con sus necesidades de eliminación cuando están en el hospital. El uso innecesario de productos absorbentes para la incontinencia no es la mejor práctica, no es una asistencia sanitaria económica y tiene efectos potencialmente adversos sobre el medio ambiente.

Introducción

Los absorbentes o pañales de incontinencia son productos sanitarios que se utilizan para la higiene personal en presencia de incontinencia urinaria o fecal. El uso correcto de estos productos contribuye a la contención y absorción de la orina y las heces1 al evacuar los líquidos de la piel2. Sin embargo, en algunos centros sanitarios se está poniendo de manifiesto que las enfermeras utilizan injustificadamente estas ayudas para la continencia en personas continentes3. Incluso estudios como el de Zisberg (2011) muestran la alta tendencia entre el personal hospitalario a utilizar pañales de incontinencia en pacientes cuyo estado no requiere dicha intervención4.

El uso de pañales en adultos mayores se asocia con múltiples resultados adversos. Por ejemplo, los estudios han descubierto que el uso de pañales: influye negativamente en la autoestima y en la calidad de vida percibida4; puede provocar incontinencia urinaria o fecal5; aumenta la dependencia para realizar las actividades cotidianas6; y conlleva la aparición de lesiones cutáneas asociadas a la humedad7-9 y lesiones por presión o infecciones urinarias10 que complican el estado de salud de los pacientes, o incluso les causan la muerte11. Los efectos adversos perjudican la calidad del sistema sanitario y generan impactos financieros debido a los costes adicionales y al aumento de las estancias hospitalarias para el tratamiento de los daños cutáneos sufridos3. Además, el uso de absorbentes genera residuos que contaminan el ecosistema12,13, y también pueden suponer gastos médicos adicionales para el paciente y/o su familia14,15. Además, generan una mayor carga asistencial para el personal sanitario y/o los familiares debido al tiempo y el esfuerzo dedicados al cambio de absorbentes, la higiene y el cuidado de la piel3.

Los estudios indican que esta práctica se utiliza debido a la falta de evaluación e intervenciones de enfermería, aparte de la aplicación de un absorbente para la incontinencia16. Un estudio de Zurcher et al. (2011) encontraron que los registros de enfermería mencionaban el uso de productos absorbentes sin documentar una evaluación previa de la continencia urinaria17. Otros estudios muestran que el personal sanitario tiene creencias que relacionan la incontinencia con el envejecimiento16 y el uso de pañales como único tratamiento higiénico para los ancianos18. También mencionan el bajo uso de estrategias de intervención de eliminación como la micción programada en residencias de ancianos, una estrategia que tiene más beneficios en comparación con el uso de pañales, ya que mantiene la continencia y promueve la movilidad y la independencia15,19.

Aunque la bibliografía describe muchos problemas relacionados con el uso de productos absorbentes innecesarios para la incontinencia, no se han estudiado a fondo los efectos asociados a la calidad de vida y las experiencias de las personas. Durante sus tareas clínicas, la investigadora observó en las personas continentes portadoras de pañales sentimientos de repulsión, incomodidad e insatisfacción con los cuidados prestados. Sin embargo, al examinar la bibliografía, pocos estudios abordan estos factores. Un ejemplo es el estudio de Alves et al. (2013)18 que describe las percepciones de las enfermeras sobre cómo los usuarios de pañales cuando no existía una indicación clínica válida para su uso, evidenciaban desconfianza, inseguridad, estrés, tristeza y malestar, entre otros. Los datos del estudio se basan únicamente en la percepción de las enfermeras y no documentan la perspectiva de los pacientes.

Por lo tanto, la razón de ser del presente estudio era investigar, explicar y compartir las "experiencias vividas" por los pacientes continentes al tener que llevar pañales de incontinencia o absorbentes cuando deseaban ir al baño mientras recibían tratamiento como pacientes hospitalizados en un hospital de alta complejidad de Bogotá (Colombia).

Metodologia

Métodos de investigación

Se utilizó una técnica de investigación cualitativa para entrevistar a los pacientes sobre lo que sentían al tener que utilizar pañales de incontinencia o absorbentes en lugar de ser asistidos para ir al baño para mantener su estado actual de continencia urinaria o fecal. Se formularon las siguientes preguntas a los pacientes reclutados para el estudio:

- ¿Cómo describiría su experiencia al utilizar un pañal?

- ¿Qué sentimientos le ha generado el uso del pañal?

- ¿Qué factores cree que influyeron en su experiencia con respecto al uso de pañales?

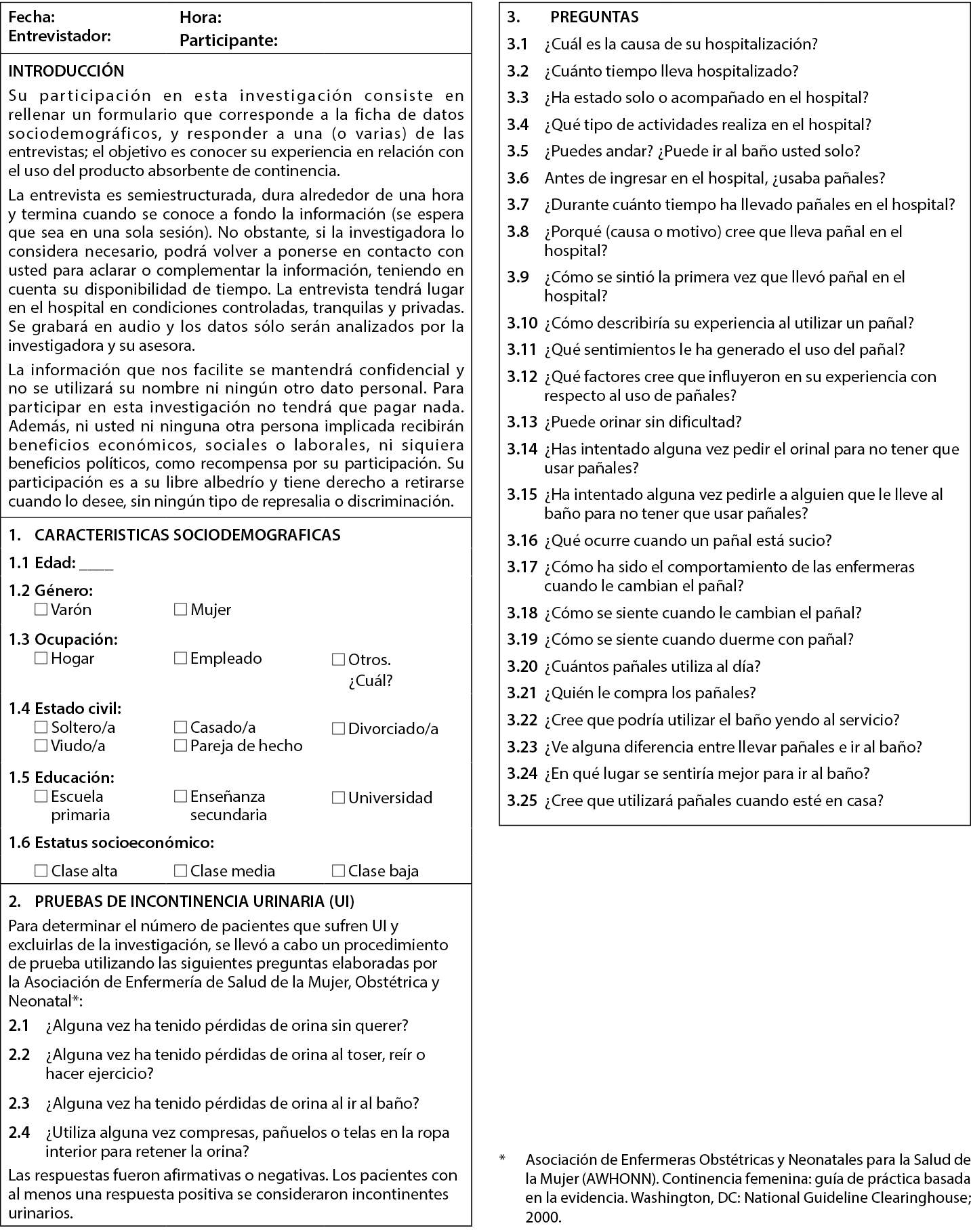

La recogida de datos se llevó a cabo mediante una prueba piloto en dos pacientes y se evaluó utilizando los criterios de Creswell20 para confirmar el funcionamiento de la guía de entrevista (Figura 1) y los aspectos que podían mejorarse para incorporarlos al proceso de recogida de datos20.

Las entrevistas fueron realizadas por el investigador en un lugar privado, y los datos se recogieron mediante grabaciones de voz y notas de campo que incluían información sobre expresiones no verbales20. Durante la sesión, el participante describía su experiencia, se introducían preguntas adicionales para especificar lo que relataba y, posteriormente, la entrevista finalizaba cuando se alcanzaba la saturación de datos20.

Figura 1. Guía para la entrevista

Criterios de selección y contratación

Los criterios de selección incluían personas continentes sin uso previo de absorbentes o pañales de incontinencia y sin discapacidad o con una discapacidad leve según el perfil PULSES.

Se seleccionaron y reclutaron siete participantes de un servicio de medicina interna de un hospital de alta complejidad de Bogotá, Colombia. Los pacientes reclutados fueron informados de los objetivos del estudio de investigación, de las medidas de privacidad y seguridad y de la opción de retirarse en cualquier momento sin que ello comprometiera la atención clínica prestada. Se obtuvo el consentimiento informado por escrito para participar en el estudio.

Tamaño de la muestra y saturación de datos

El muestreo fue teórico (o intencionado) con el fin de comprender mejor las cuestiones centrales del presente estudio21. La entrevista se consideró completa cuando los datos recogidos describían el fenómeno identificado en las preguntas orientadoras y el total de entrevistas era adecuado cuando se producía la saturación de datos, es decir, los datos incluían información suficiente para replicar el estudio, no se obtenía información nueva en las entrevistas y ya no se consideraba factible seguir codificando22.

Analisis de datos

Las entrevistas se transcribieron, almacenaron y clasificaron por un número para mantener el anonimato de los pacientes. La herramienta utilizada fue el programa ATLAS.ti versión 6.0 (2003-2010, ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlín. Autora: Dra. Susanne Friese) para la organización, codificación y análisis de la información23. El análisis se realizó según la fenomenología Husserliana, ya que permitía comprender la experiencia vivida por las personas relacionadas con el fenómeno24. Fundamentalmente, este análisis aleja la investigación de enfermería de la preferencia personal y la orienta hacia un rendimiento más puro25, permite conocer el fenómeno tal y como lo vive una persona26 y produce un conocimiento científico imparcial que refuerza los principios y las prácticas de la enfermería y contribuye, por tanto, al desarrollo profesional27.

En el estudio se realizó una inmersión constante en los datos para comprender lo que estaba ocurriendo28. La investigadora de este estudio se autoevaluó constantemente para neutralizar las ideas preconcebidas y no influir en el objeto de estudio26. A partir de las declaraciones de los participantes, las referencias significativas, los fragmentos de texto o descriptores y los códigos nominales, se crearon categorías para describir el fenómeno. Un segundo investigador participó en la validación de los datos transcritos, contribuyendo así a la exactitud del proceso. Cada categoría resultante se comparó con las descripciones originales a efectos de validación.

Resultados

En el estudio participaron siete personas continentes sin diagnóstico previo de incontinencia urinaria o fecal y que no habían utilizado anteriormente productos absorbentes ni pañales de continencia. La edad media de los participantes rondaba los 74 años y la mayoría procedía de un entorno socioeconómico bajo con un bajo nivel educativo. Al indagar más sobre las razones para usar pañales, los participantes refirieron tener dificultades de movilidad para ir al baño, discapacidad visual, mareos y alteración en los movimientos de las extremidades inferiores. Todos ellos tenían una discapacidad leve según el perfil PULSES y podían ir al baño con ayuda para caminar o utilizando un dispositivo andador o una silla de ruedas.

A partir del análisis de los datos, se identificaron afirmaciones significativas, se formularon significados y se agruparon en cinco categorías comunes: adentrarse en un mundo desconocido; buscar cuidados; someterse al uso de un producto absorbente de continencia; la reacción de mi cuerpo al uso de un producto absorbente de continencia; y adaptarse o intentar recuperar mi independencia. A continuación se ofrecen más descriptores y experiencias de los pacientes en estas categorías.

Adentrarse en un mundo desconocido

Esta categoría expresa la transición que experimentó el paciente cuando ingresó como paciente interno en el hospital y cómo afectó el ingreso a su pauta de eliminación. En casa, los pacientes pueden ir al baño de forma independiente, privada y tranquila, pero la situación cambia cuando ingresan en el hospital. Ir al baño mientras están en el hospital es difícil debido a su situación sanitaria y por eso buscan el acompañamiento del personal sanitario. Sin embargo, como no encuentran apoyo en estas personas, la única opción que reciben es hacer sus necesidades en los pañales.

Una persona continente con problemas de movilidad y discapacidad visual, que intenta ir al baño, informa:

Mientras estuve aquí, en el hospital, fue cuando tuve que usar el pañal... Cuando entré, no me preguntaron si quería, lo hicieron sin preguntar, me dijeron: Necesitas un pañal; debes usarlo... y yo dije: De acuerdo. Hagámoslo... y desde entonces llevo el pañal. Pero es mejor ir al baño, es más higiénico, para ir al baño, pero tengo que pedir ayuda porque veo sombras; a veces me atienden, pero otras veces están ocupados con otros pacientes y tengo que esperar – E6.

En busca de atención

Esta categoría describe cómo estos sujetos intentaron evitar el uso del pañal y decidieron buscar ayuda para ir al baño. Como la prestación de dicha asistencia no llegaba a tiempo y a veces tardaba horas, la capacidad de los pacientes para contener la orina o la eliminación fecal era limitada, y se producía una sensación de urgencia. En el deseo de contener las necesidades de eliminación, también expresaron sufrimiento, vergüenza, resignación, malestar, insomnio, dolor abdominal e hinchazón. Estas sensaciones remitieron tras la eliminación. En esta categoría se describe a una persona:

Tuve una trombosis. Todo este lado se paralizó (señala el lado derecho del cuerpo), (...) Ya estoy usando el andador... pero aún así, no puedo ir al baño sola. Lo que pasa es que tengo miedo de caerme... Cuando tengo que ir al baño, les llamo y les digo: ¡llévame al baño! pero a veces no tienen tiempo... ¡y (gruñidos)! (señala el abdomen y simula dolor). Anoche, por ejemplo, tuve unos cólicos tan horribles... fue porque les pedí durante dos horas que vinieran a llevarme al baño y estaba muy apurada – E2.

Aunque los pacientes intentaron esperar, finalmente llegaron a un punto en el que no pudieron resistir el impulso de eliminar. Entonces se resignaban a excretar en el absorbente/pañal de incontinencia y experimentaban una momentánea sensación de alivio.

De vez en cuando, el equipo de enfermería se ocupa de sus ganas de ir al baño a tiempo. Alguien lo menciona:

He ido al baño a hacer mis necesidades. Normalmente me asiste una enfermera. Ayer me llevó al baño, me ayudó a sentarme y a estar cómoda... Es atenta; cuida de mí; siempre dice: ¿Qué quieres? ¿Qué debo hacer? Todos son muy atentos; cuando nos atienden, lo hacen con mucho cariño – E4.

Someterse al uso de un producto absorbente de continencia

La categoría se refiere a los sujetos que no necesitaban usar pañales, pero sentían que "tenían" que hacerlo. Querían hacer sus necesidades en el baño, pero no recibieron ninguna ayuda a pesar de insistir repetidamente en recibirla. Por ello, tuvieron que renunciar a sus deseos y decidieron hacer sus necesidades con absorbentes/pañales de incontinencia. Con el tiempo, los pacientes dejaron de llamar al personal de enfermería para que los llevaran al baño y se resignaron a llevar un absorbente/pañal de incontinencia. Los pacientes se sienten a merced del personal sanitario, que dispone de poco tiempo y además sufre escasez de personal. Como consecuencia, se sienten limitados y vulnerables. Los pacientes han hecho los siguientes comentarios:

Bueno, tengo que llevar pañal, pero no lo necesito... llevar pañal es incómodo, pero es lo que tenía que hacer. A pesar de todo, me gusta ir al baño e intento encontrar a alguien que me ayude, pero no me ayudan – E1.

Siento como un impedimento para llevar pañal; no me siento bien... Me siento dependiente de la voluntad de la gente – E6.

La reacción de mi cuerpo al uso de un producto absorbente de continencia

Esta categoría describe los sentimientos expresados y desagradables de los pacientes sobre el uso de un producto absorbente de continencia. Utilizaban términos como: humedad; calor, carga; sensación de quemazón; suciedad, rozadura o incomodidad; e incluso la pérdida de sueño. Además, les preocupaban los gastos en que incurrían sus familias cuando tenían que comprar absorbentes o pañales de incontinencia. Otro problema que les preocupaba eran las lesiones cutáneas debidas al retraso en el cambio de pañal. La gente hizo estos comentarios sobre esta categoría:

Cuando llevo pañal, me siento sucia... demasiado caliente; intentas sudar. Además, el pañal me molesta, me da frío, me moja; me siento mal. Por eso me lo quito o le digo a la enfermera que me lo cambie. Puedo aguantar horas con el pañal mojado... y a veces eso produce algún tipo de descamación, quemazón... que es molesto – E6.

Ahora estoy quemada... porque han tardado mucho en cambiarme el pañal; me quemo del todo, por eso me están poniendo pomada – E7.

Siento que llevar pañal altera mi sueño. Me siento incómodo y no puedo descansar bien debido a la humedad – E4.

Creo que comprar pañales me afecta económicamente... A veces mi marido no tiene dinero para pañales, y tiene que pedir prestado algo de dinero, entonces viene y los compra – E2.

Adaptarme o intentar recuperar mi independencia

Esta categoría hace referencia a cómo los pacientes adoptan el hábito de hacer sus necesidades en el absorbente o en los productos para la incontinencia sin que exista un diagnóstico clínico de incontinencia u otra causa física o motivo para hacerlo, sólo porque no hay asistencia de enfermería que les permita ir al baño. Otras personas persistieron en evitar el uso de dispositivos para incontinencia e intentaron recuperar su independencia realizando actividades que les ayudaran a movilizarse o incluso yendo solas al baño, lo que aumentó el riesgo de caídas y lesiones. Algunas personas mencionaron:

No me siento mal por llevar pañal, uno se acostumbra... ahora pido que me pongan el pañal... ¡me gusta ir al baño, pero pido que me pongan (el pañal) por pereza! - E6.

Así que cuando voy al baño al menos camino un poco, y también siento la vida como antes. Quiero volver a mi antigua vida, ir al baño, normal – E5.

Intenté ir sola al baño porque a veces los asistentes estaban ocupados con otros pacientes. Siempre me doy contra las paredes porque no veo. Ayer fui al baño... ni se dieron cuenta – E6.

Discusion

Este estudio cualitativo de tamaño muestral pequeño y selectivo describe la experiencia de los pacientes de tener que utilizar absorbentes/pañales para la incontinencia sin una indicación clínica válida para su uso como una experiencia chocante. En este estudio los pacientes se sintieron obligados a utilizar este tipo de dispositivos porque no tenían otra opción, lo que generó consecuencias negativas a nivel físico y personal que podrían haberse evitado.

Estudios como el de Zisberg (2011) muestran la alta tendencia entre el personal hospitalario a utilizar pañales de incontinencia en pacientes cuyo estado no requiere dicha intervención4. Esto se debe a la escasez de personal, a la falta de tiempo para elaborar una mejor planificación de la atención al paciente16 y a la delegación de la atención en personal técnico sin la supervisión adecuada18. En el hospital en el que se llevó a cabo este estudio, se encontró una situación similar: el personal de enfermería delega la tarea de las necesidades relacionadas con la eliminación en el técnico o en el personal auxiliar y no supervisa el tipo de personas a las que se proporcionan pañales.

Sin embargo, independientemente de que los pacientes sean continentes o tengan la posibilidad de ir al baño con ayuda, cada vez es más frecuente que el personal sanitario utilice pañales de forma rutinaria con fines higiénicos en ancianos18 o personas con discapacidad funcional15. Esto ocurre porque el personal sanitario no evalúa la continencia, asocia la incontinencia urinaria con el envejecimiento18,29 y cree que las personas con discapacidad funcional necesitan llevar pañales15.

En este estudio también se observó que en casa los pacientes pueden ir al baño de forma independiente; sin embargo, esta situación cambia cuando ingresan en el hospital, ya que la única opción que se les da es hacer sus necesidades en un pañal. Esta no es la mejor práctica, ya que las personas continentes deben utilizar el baño. Según los estudios, ni siquiera los pacientes semidependientes deben utilizar un pañal para hacer sus necesidades. Por el contrario, necesitan ir al baño para estimular su movilidad e independencia15,30.

En este estudio, los pacientes que sentían ganas de ir al baño y necesitaban asistencia de enfermería para hacerlo intentaban resistirse al uso de absorbentes/pañales de incontinencia. Sin embargo, a medida que pasaban las horas sin ninguna asistencia de enfermería, no tenían otra opción que ceder y hacer sus necesidades dentro de los pañales. En el deseo de contener las necesidades de eliminación, también expresaron sufrimiento, vergüenza, resignación, malestar, insomnio, dolor abdominal e hinchazón. Estas sensaciones remitieron tras la eliminación. Al buscar en la literatura, no se encontraron estudios que describieran en detalle esta resistencia de los pacientes continentes al uso del pañal. Por este motivo, el presente estudio permitió conocer mejor las experiencias de los pacientes.

Además, como ya se ha señalado, aunque los pacientes intentaban esperar, al final llegaban a un punto en el que no podían resistir el impulso de eliminar. Entonces se resignaban a excretar en el absorbente/pañal de incontinencia y experimentaban sensaciones desagradables. Describieron incomodidad y malestar por estar en contacto prolongado con sus heces u orina. Los sentimientos verbalizados fueron de inquietud, frustración, desesperanza y, en particular, de pérdida de independencia. También se sentían incómodas con la sensación de humedad, calor y presión, además de los efectos sobre su piel, como ardor y dolor por la dermatitis asociada a la incontinencia. Al examinar la bibliografía, pocos estudios abordan estos factores; sin embargo, algunos resultados son similares. Un estudio es el de Alves et al. (2013) que describe las percepciones de las enfermeras sobre los usuarios de pañales cuando no existe una indicación clínica validada para su uso. Se constata desconfianza, inseguridad, estrés, tristeza y malestar, además de pérdida de identidad, dependencia o fragilidad por el uso de pañales18. En otro estudio sobre la percepción de los ancianos hospitalizados, mencionan la sensación de malestar, baja autoestima, repugnancia, picor, dolor, ineficacia, calor y restricción motora6.

Tras exponerse a estas sensaciones, algunos pacientes adoptan el hábito de aliviarse en el absorbente o en los productos para la incontinencia. El estudio de Zisberg (2011) afirma que, incluso entre los pacientes continentes, el uso de pañales puede ser "adictivo", al menos a corto plazo, lo que puede explicar el comportamiento de estos pacientes4. Por otro lado, otras personas persistían en evitar el uso de dispositivos para incontinentes e intentaban recuperar su independencia realizando actividades que les ayudaran a movilizarse o incluso yendo solas al baño, lo que aumentaba el riesgo de caídas y lesiones.

La bibliografía arroja resultados similares; sin embargo, la investigación es escasa, lo que permite que el presente estudio ofrezca un mayor conocimiento de las experiencias de los pacientes al verse obligados a utilizar pañales de forma innecesaria. Esta práctica expone a los pacientes a posibles daños cutáneos y traumas psicológicos que pueden suponer un tiempo de recuperación problemático o más largo31. Las personas continentes de orina buscan asistencia de enfermería para ir al baño y mantener su nivel de independencia. Sin embargo, este estudio descubrió que en la mayoría de las ocasiones no reciben apoyo de estas personas y la única opción que reciben es hacer sus necesidades en los pañales.

En estos casos, el absorbente se utiliza innecesariamente y puede sustituirse por otros métodos. Según Jonasson et al. (2016), es necesario avanzar hacia un enfoque más centrado en la persona en la medida de lo posible16, utilizando métodos como la asistencia programada al ir al baño para ayudar a reforzar la movilidad, mejorar la autonomía y la independencia30,32, y mantener la salud y el bienestar16.

Para que estos métodos sean aplicados por el personal hospitalario, es necesario un cambio de prácticas. Un estudio de Bernard et al. (2020) esboza cómo el apoyo del educador de enfermería y de la administración puede contribuir a reducir el uso de pañales para mejorar la experiencia asistencial del paciente. Los enfermeros educadores pueden enseñar a ir al baño correctamente, explicar cómo evaluar la continencia de los pacientes y cómo utilizar los horarios de aseo de los pacientes, y seleccionar los dispositivos de recogida/contención adecuados. Asimismo, el apoyo administrativo contribuye a la aplicación de programas y protocolos sobre buenas prácticas en el cuidado de la continencia, restringe el uso de absorbentes, aumenta la disponibilidad de dispositivos opcionales de contención urinaria/fecal y proporciona herramientas de apoyo para ir al baño, como instalaciones adecuadas y enfermeras y fisioterapeutas formados en el manejo de la continencia33.

Conclusiones

Los resultados del estudio muestran que el sistema de salud colombiano no siempre responde de manera eficiente a las necesidades clínicas de los pacientes con discapacidad leve para mantener la independencia con continencia urinaria y fecal. La prestación de asistencia de enfermería no llegó a tiempo y obligó a los pacientes a llevar pañales de forma innecesaria e involuntaria, lo que minó la confianza en sí mismos y la seguridad de los pacientes y les causó secuelas físicas y psicológicas. También hubo implicaciones económicas que afectan a la familia y a las instituciones sanitarias con el aumento de los costes del tratamiento. Este estudio muestra cómo las instituciones sanitarias no siempre tienen en cuenta la funcionalidad física y social y la preferencia de los usuarios en cuanto a sus necesidades de eliminación, lo que genera insatisfacción, incomodidad, vulnerabilidad y pérdida de dependencia.

En este sentido, estudios fenomenológicos como éste son una ventana para la reflexión y un camino para lograr una mejor calidad asistencial34. Los profesionales sanitarios, aunque con limitaciones de tiempo y de otro tipo, tienen que entender la perspectiva de los pacientes y mantener la independencia respecto a sus necesidades de eliminación cuando están en el hospital. Por eso es necesaria una atención holística individualizada16 que ofrezca cuidados más allá de los procedimientos asistenciales habituales, teniendo en cuenta las prioridades y necesidades de eliminación de los pacientes.

Los límites

Este estudio de investigación tenía una muestra teórica muy pequeña. Por lo tanto, los resultados del estudio no deben generalizarse a todos los centros sanitarios. Es necesario investigar más sobre este fenómeno.

Agradecimientos

Agradecemos a todos los participantes en el estudio por su colaboración.

Conflicto de intereses

No hay conflictos de intereses que declarar.

Declaración ética

Este estudio fue avalado por el Comité de Ética de la Facultad de Enfermería de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia: aprobación (021-18) y por el Comité de Ética en Investigación de la institución de salud, aprobación (119/18).

Financiación

Los autores no recibieron financiación por este estudio.

Author(s)

Sandra Guerrero Gamboa

PhD MN ETN RN

Associate Professor, Faculty of Nursing, National University of Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

Angie Viviana Ariza Garzón*

MN RN

National University of Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

Email avarizag@unal.edu.co

* Corresponding author

References

- Qin Y. Medical textile materials. Woodhead Publishing; 2015.

- De Sousa Lopes Reis Do Arco HM, Mendes da Costa A, Machado Gomes B, Anacleto N, Jorge da Silva RA, Peixe da Fonseca SC. Nursing interventions in dermatitis associated to incontinence integrative literature review. Enfermería Glob 2018;17(52):689–730.

- Palese A, Regattin L, Venuti F, et al. Incontinence pad use in patients admitted to medical wards: an Italian multicenter prospective cohort study. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs 2007;34(6):649–54.

- Zisberg A. Incontinence brief use in acute hospitalized patients with no prior incontinence. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs 2011;38(5):559–64.

- Zisberg A, Sinoff G, Gur-Yaish N, Admi H, Shadmi E. In-hospital use of continence aids and new-onset urinary incontinence in adults aged 70 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59(6):1099–1104.

- de Almeida Ferreira Alves L, Ferreira Santana R, da Silva Schulz R. Nursing staffs’ perceptions of the use of adult diapers in hospital. Rev Enferm UERJ 2014;22(3):371–75.

- Fader M, Clarke-O’Neill S, Cook D, Dean G, Brooks R, Cottenden A, Malone-Lee J. Management of night-time urinary incontinence in residential settings for older people: an investigation into the effects of different pad changing regimes on skin health. J Clin Nurs 2003;12(3):374–86.

- Brown D. Diapers and underpads. Part 1: skin integrity outcomes. Ostomy Wound Manage 1994;40:20–22.

- Fader M, Bain D, Cottenden A. Effects of absorbent incontinence pads on pressure management mattresses. J Adv Nurs 2004;48(6):569–74.

- Christini Silva T, Mazzo A, Rodrigues Santos RC, Jorge BM, Souza Júnior VD, Costa Mendes IA. Consequences of adult patients using disposable diapers: implications for nursing care. Aquichan 2015;15(1):21–30.

- Beeckman D, Van Lancker A, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of incontinence-associated dermatitis, incontinence, and moisture as risk factors for pressure ulcer development. Res Nurs Heal 2014;37(3):204–18.

- Thompson E, Rounsefell B, Lin F, Clarke W, O’Brien KR. Adult incontinence products are a larger and faster growing waste issue than disposable infant nappies (diapers) in Australia. Waste Manage 2022;152:30–7.

- Ntekpe ME, Okon E, Ndifreke E, Hussain S. Disposable diapers: impact of disposal methods on public health and the environment. Am J Med Pub Health 2020;1(2):1–7.

- Bitencourt G, Santana R. Evaluation scale for the use of adult diapers and absorbent products: methodological study. Online Braz J Nurs 2021;20:1–13.

- Bitencourt GR, Alves LAF, Santana RF. Practice of use of diapers in hospitalized adults and elderly: cross-sectional study. Rev Bras Enferm 2018;71(2):343–49.

- Jonasson L, Josefsson K. Staff experiences of the management of older adults with urinary incontinence. Health Aging Res 2016;5(16):1–11.

- Zurcher S, Saxer S, Schwendimann R. Urinary incontinence in hospitalised elderly patients: do nurses recognise and manage the problem? Nurs Res Prac 2011;1–5.

- Alves L, Santana R. Perceptions of the nursing team about the use of geriatric diapers in the hospital. Ciênc Cuid Saúde 2013;12(1):19–25.

- Roe B, Flanagan L, Jack B, et al. Systematic review of the management of incontinence and promotion of continence in older people in care homes: descriptive studies with urinary incontinence as primary focus. J Adv Nurs 2011;67(2):228–50

- Hernández Sampieri R, Fernández Collado C, Baptista Lucio M. Metodología de la investigación científica. 5th ed. Mexico: McGraw-Hill Interamericana; 2020.

- Coyne IT. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling: merging or clear boundaries? J Adv Nurs 1997;26(3):623–30.

- Fusch P, Lawrence N. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual Rep 2015;20(9):1408–16.

- San Martín Cantero D. Grounded theory and ATLAS.ti: methodological resources for educational research. Rev Electrónica Investigación Educativa 2014;16(1):104–122.

- Bahadur S. Phenomenology: a philosophy and method of inquiry. J Educ Educ Dev 2018;5(1):215–22.

- Schultz G, Cobb-Stevens R. Husserl’s theory of wholes and parts and the methodology of nursing research. Nurs Philos 2004;5(3):216–23.

- Neubauer B, Witkop C, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ 2019;8(2):90–7.

- Cuesta Benjumea C. Qualitative research and development of nursing knowledge. Texto Contexto Enferm 2010;19(4):762–68.

- Maher C, Hadfield M, Hutchings M, Eyto A. Ensuring rigor in qualitative data analysis: a design research approach to coding combining NVivo with traditional material methods. Int J Qual Method 2018;17:1–13.

- Rodriguez N, Sackley C, Badger F. Exploring the facets of continence care: a continence survey of care homes for older people in Birmingham. J Clin Nurs 2007;16(5):954–62.

- Jirovec M. The impact of daily exercise on the mobility, balance and urine control of cognitively impaired nursing home residents. Int J Nurs Stud 1991;28(2):145–51.

- Alligood R, Tomey M. Nursing theorists and their work. 7th ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2010.

- Schnelle J, Alessi C, Simmons S, Al-Samarrai N. Translating clinical research into practice: a randomised controlled trial of exercise and incontinence care with nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50(9):1476–83.

- Bernard L, Stephens M, Kuhnke J L. Prevention of incontinence-associated dermatitis linked with briefs use in acute care: a quality improvement project. NSWOC 2020;31(2):28–37.

- Palacios D, Corral I. The basics and development of a phenomenological research protocol in nursing. Enferm Intensiva 2010;21(2):68–73.