Volume 44 Number 2

Evaluating risk factors for development of a parastomal hernia: a retrospective matched case-control study

Lynette Cusack, Fiona Bolton, Kelly Vickers, Amelia Winter, Jennie Louise, Leigh Rushworth, Tammy Page, Amy Salter

Keywords Parastomal hernia, risk factors, stomas, stomal therapy nurses, retrospective matched case-control study

For referencing Cusack L, Bolton F, Vickers K, et al. Evaluating risk factors for development of a parastomal hernia: a retrospective matched case-control study. WCET® Journal 2024;44(2):20-28

DOI

10.33235/wcet.44.2.20-28

Submitted 6 February 2024

Accepted 14 May 2024

Abstract

Aim Identify risk factors most likely to contribute to parastomal hernia development.

Methods Retrospective matched case-control study using retrospective case note reviews. One public and one private South Australian hospital. Ostomates who underwent stoma formation surgery between 2018 and 2021, and did (‘cases’, n=50) or did not (‘controls’, n=50) develop parastomal hernia were matched by ostomy type. Potential parastomal hernia risk factors were identified from the literature and expert opinion to build a case note review tool. Case notes were selected by surgical date from 2018. Analyses were conducted in which univariable logistic regression investigated relationships between potential risk factors and parastomal hernia development. Exploratory subgroup analyses investigated whether relationships between risk factors and development of parastomal hernia differed according to ostomy type.

Results Patient characteristics were summarised descriptively and by hospital. Statistically significant evidence was found of links between development of parastomal hernia and higher BMI (OR for 5 kg/m2 increase: 1.74; 95% CI: 1.19, 2.76), post-operative infection (OR 2.68; 95% CI: 1.04, 7.33), multiple abdominal surgeries (OR 4.21; 95% CI: 1.18, 19.90), time since surgery (OR >30 months: 0.003; 95% CI: 0.0004, 0.02), and aperture size (OR for 1mm increase: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.02,1.24). Sufficient evidence was not found of expected relationships with factors such as smoking, chemotherapy and/or pelvic radiotherapy, lifestyle and activity factors.

Conclusions This study contributes to furthering the understanding of the relationships between known risk factors to inform stomal therapy nurses’ practice in the prevention of a parastomal hernia.

High body mass index, postoperative infection, multiple surgeries, wide diameter of the stoma, and time since surgery of less than 30 months increased the risk of parastomal hernia, other factors did not reach significance probably due to use of an underpowered sample.

Opportunities to repeat this study would further strengthen the necessary evidence of the most important risk factors.

Background

Several conditions may lead to the formation of an intestinal stoma, including bowel/rectal and bladder cancer and inflammatory bowel disease. A stoma is a surgically created opening on the abdomen allowing stool or urine to leave the body via a colostomy, urostomy, or ileostomy. Estimated ostomy numbers vary worldwide. Recent numbers in the United States are more than 725,000;1 European numbers are estimated at around 700,000;2 and Australian numbers are approximately 50,000.3 A parastomal hernia, when the intestines press outward through an abdominal wall defect in the vicinity of the stoma, is one of the most common complications experienced by people (Ostomates) who have had stoma formation surgery.4 While estimated rates of parastomal hernia development vary, many estimates suggest around 50% of people with a stoma will develop a potentially preventable parastomal hernia.4 Parastomal hernias are often painful and disruptive, impairing an Ostomate’s quality of life.5,6,7

A systematic review by Zelga et al,8 identified multiple risk factors that may contribute to developing a parastomal hernia including: body mass index (BMI); tobacco or alcohol misuse; presence of comorbid conditions (such as diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Several surgery-related factors were also identified including type of stoma (e.g. in the small or the large intestine, loop versus end stoma, surgeon’s expertise), position of the stoma on the abdomen and the setting in which the ostomy was created (emergency vs elective). Another factor identified in the literature is malnutrition causing poor healing of the stoma or wound.9 Finally, some research suggests parastomal herniation is more likely to occur in women than men.10

The purpose of this article is, firstly, to report the results on the most likely risk factors that would contribute to the development of a parastomal hernia to refine current parastomal hernia risk assessment tools; and secondly, to document the process of undertaking a retrospective matched case-control study. It is hoped that this will inform replication by future researchers to strengthen the available evidence and advance the understanding of the risks for developing a parastomal hernia. STROBE guidelines for reporting observational studies provided direction on reporting.11

Methods

Research Design

A retrospective matched case-control study by way of case note review was undertaken to identify risk factors that appear to have strongest association with development of parastomal hernia after surgery.

Setting

The case note review was conducted at two sites: one major metropolitan public hospital and one smaller private metropolitan hospital in South Australia where stoma surgery is undertaken. Experienced stomal therapy nurses are employed at both hospitals working closely with colorectal surgeons to provide support to Ostomates.

Participants

The retrospective case note review consisted of two participant groups of Ostomates who had stoma formation surgery between 2018–2021. Group 1 were ‘cases’: a selection of case notes of some, not all, Ostomates who developed a parastomal hernia within this time frame (after original surgery) (n=50). The second group were controls: a selection of case notes of Ostomates who did not develop a parastomal hernia between 2018–2021 (after original surgery) (n=50), and they were proportionally matched according to type of ostomy. The identification and reporting of parastomal hernias were informally diagnosed by stomal therapy nurses or by confirmed computed tomography scans following medical review for suspected parastomal hernia. Selection of case notes was sequential, starting with the earliest surgeries from 2018. An equal number of case and control notes was to be selected from each of the two hospitals, with the intention that each hospital provide 25 case and 25 control case notes. However, this was not able to be achieved due to availability of case notes on each site. Therefore, 99 case notes were analysed: 50 from the public hospital (25 cases and 25 controls), and 49 from the private hospital (23 case and 26 control).

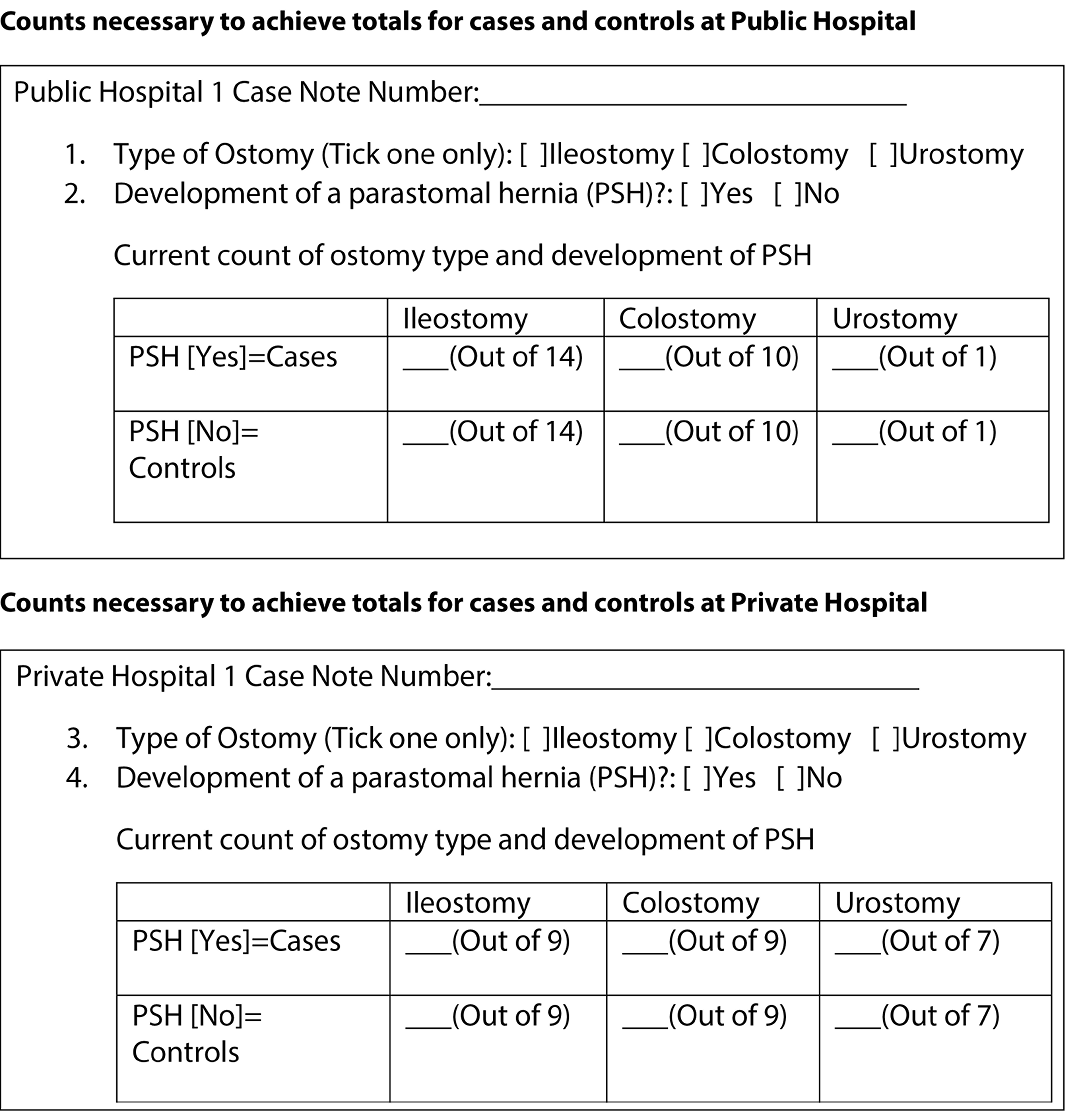

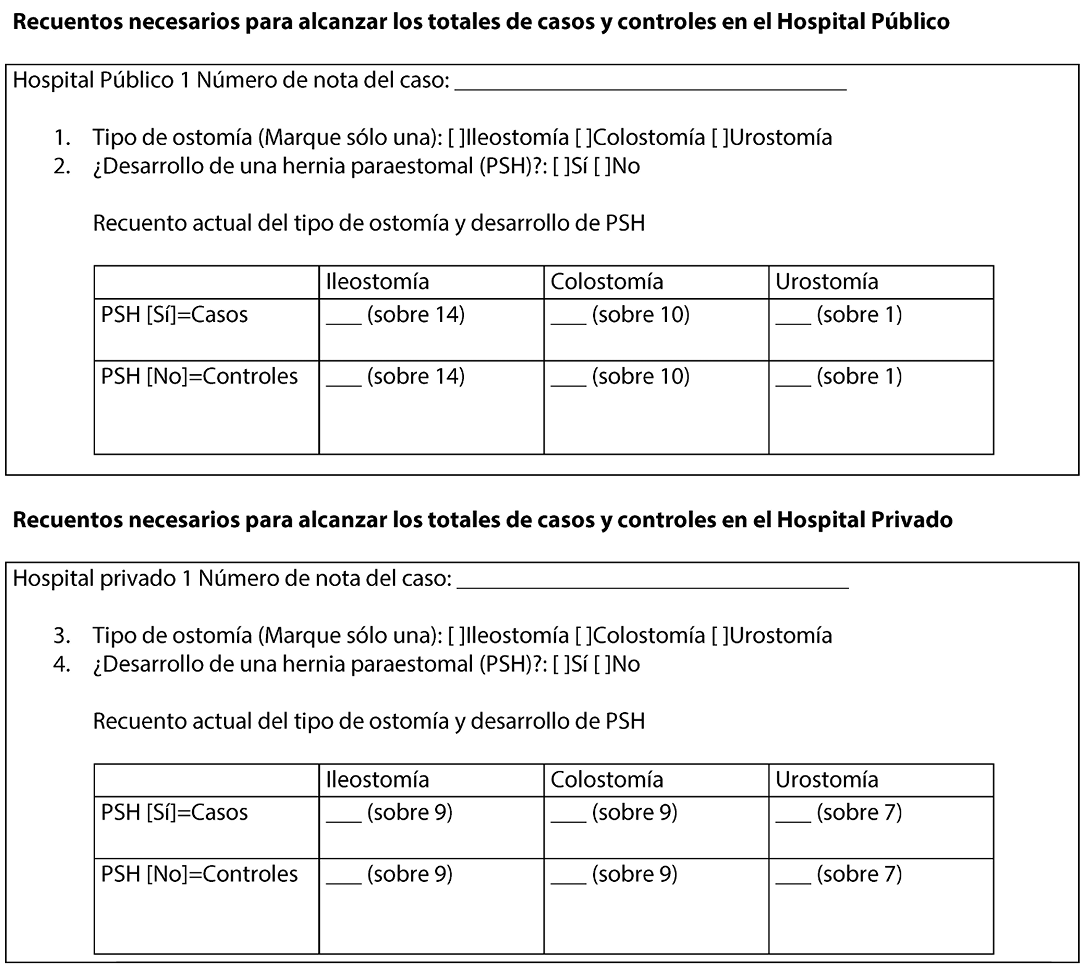

To ensure appropriate representation of ostomy type at each of the two hospitals (with different ostomy profiles), approximate observed proportions between 2018 and 2021 were purposively, or specifically, sampled. At the public hospital the proportion was 56% Ileostomy/40% Colostomy/4% Urostomy, while at the private hospital the proportion was 36% Ileostomy/36% Colostomy/28% Urostomy which corresponds with the percentage of ostomy surgery type at each respective hospital. To achieve these proportions, this meant (for example) ignoring notes from one ostomy type if the requisite quota for that type had already been met (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Format for determining sampling for each hospital based on Ostomy type and presence of parastomal hernia.

Review tool and data sources

The case note review tool was developed through identifying key risk factors for parastomal hernias from the literature, the Association of Stoma Care Nurses, United Kingdom Risk Assessment Tool,12 two previous Australian studies of stomal therapy nurses’ perceptions13 and the lived experiences of Ostomates.14 The multidisciplinary nature of the research team was critical in the development and appraisal of the review tool to ensure input of relevant academic and clinical experience including physiotherapy, stomal therapy, and psychology, as well as a robust understanding of the evidence base (from biostatisticians). To ensure inter-user reliability and consistency in data collection, the final review tool was piloted by four members of the research team, who held positions in each hospital, until 100% agreement was reached on the items within the review tool. Four case notes each from the case and control groups were piloted. These case notes were not included in the final review. Assessing activity levels proved difficult when piloting the tool. However, the decision to include the metabolic equivalent of task (frequently referred to as METs)15 made this more feasible. This tool was often used by anaesthetists and was therefore recorded in the patients’ preoperative anaesthetic assessment. Other minor changes were made to the review tools’ wording and items to improve clarity and relevance.

Data collection and Statistical methods

Using patient case note numbers (unit records), case notes for review were selected through sequential selection from a list from each hospital. The case note review tool was manually completed for each case note by the four researchers from the two hospitals involved, as both hospitals still used hardcopy case notes.

Data from the review forms were imported from Excel into R v4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) for cleaning and subsequent analysis, according to a pre-specified analysis plan. Patient characteristics were summarised descriptively both overall and by study centre. Univariable relationships between pre-specified potential risk factors and development of a parastomal hernia were analysed using logistic regression. For binary risk factors, estimates were reported as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for ‘yes’ vs ‘no’; for nominal or ordinal risk factors estimates were reported as OR and 95% CI for each subsequent level versus a reference level; and for continuous risk factors, estimates were reported as OR and 95% CI for a stipulated increase. All models were adjusted for type of ostomy (variable used for matching cases and controls), and some models were additionally adjusted for year of surgery. Exploratory subgroup analysis was also carried out to investigate whether relationships between risk factors and development of parastomal hernia differed according to type of ostomy. An interaction term between ostomy type and risk factor was included in the model, and separate estimates of risk (as OR) were obtained for each ostomy type.

Ethics

This project received approval from both the public and private hospitals Human Research Ethics Committees: Central Adelaide Local Health Network Ref 16705: St Andrews Hospital Number 138: University of Adelaide H-2020-231. The research team sought waiver of patient consent from each Ethics Committee, which was approved based on the assurance of anonymity and confidentiality by not reporting identifiable information about individuals. Strict processes of access and storage of case notes were followed according to each hospital’s policy during data collection.

Results

Process and Descriptive Statistics

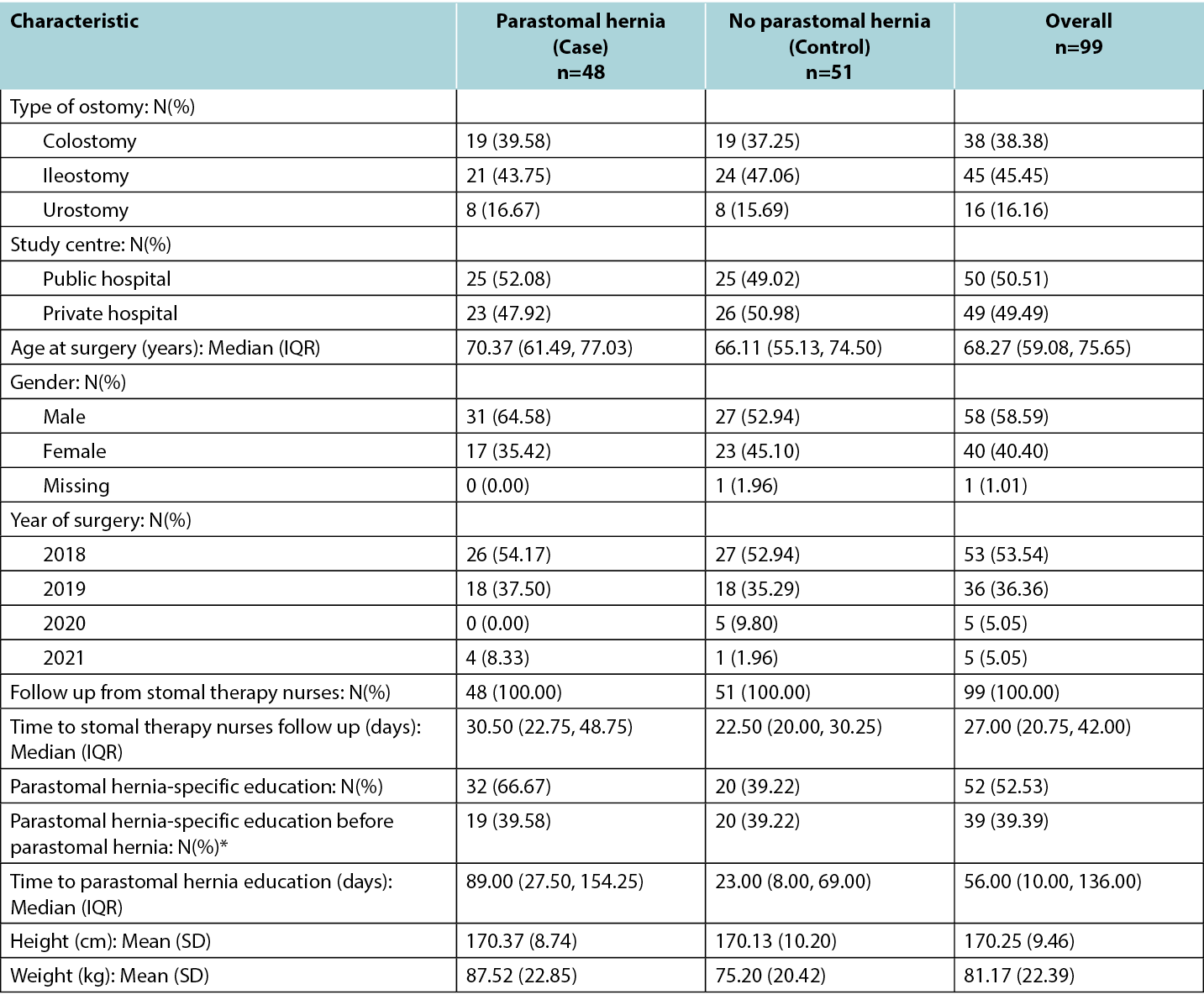

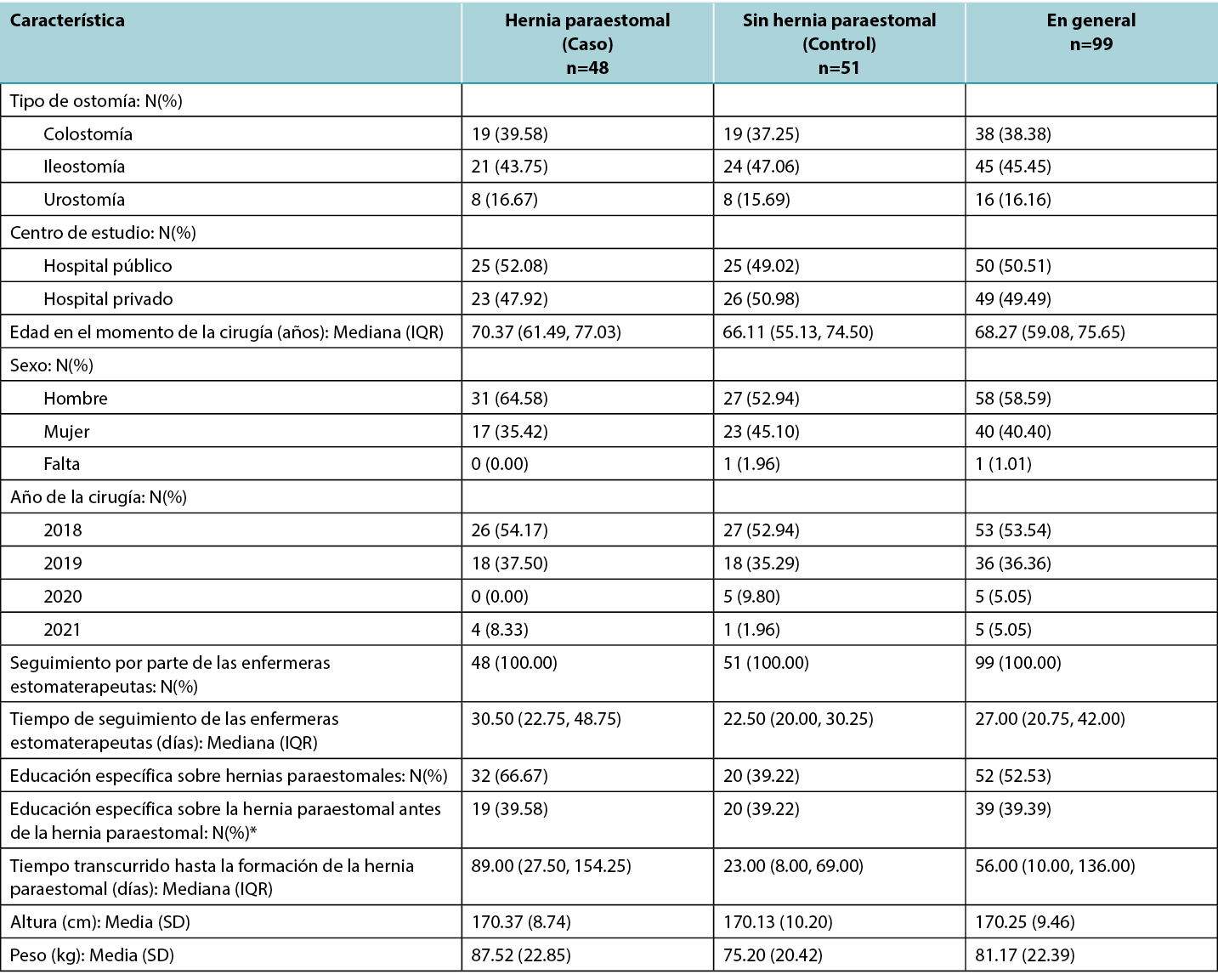

The approach for the matched case-control study was necessarily pragmatic, given that the number of case notes reviewed was limited by time available to the researchers and ability to access case notes within the hospital. As neither hospital had electronic records, original hard copy case notes were accessed. This process was very time consuming. Table 1 reports characteristics of included participants, by case/control status and overall. The numbers for cases (parastomal hernia) and controls (no parastomal hernia) are not precisely equal for each ostomy type. Patient characteristics differed slightly between cases and controls, with cases being slightly older (median age 70.37 years compared to 66.11 years for controls), more likely to be male (64.6% of cases compared to 52.9% of controls) and having a higher mean weight (87.5 kg compared to 75.2kg for controls). The rate of follow up from stomal therapy nurses was 100% in both groups, and the proportion of patients receiving parastomal hernia-specific education prior to development of a hernia was similar in cases (39.6%) and controls (39.2%).

Patient characteristics were similar between the two study centres (See Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of participants by case/control status and overall.

Potential risk factors

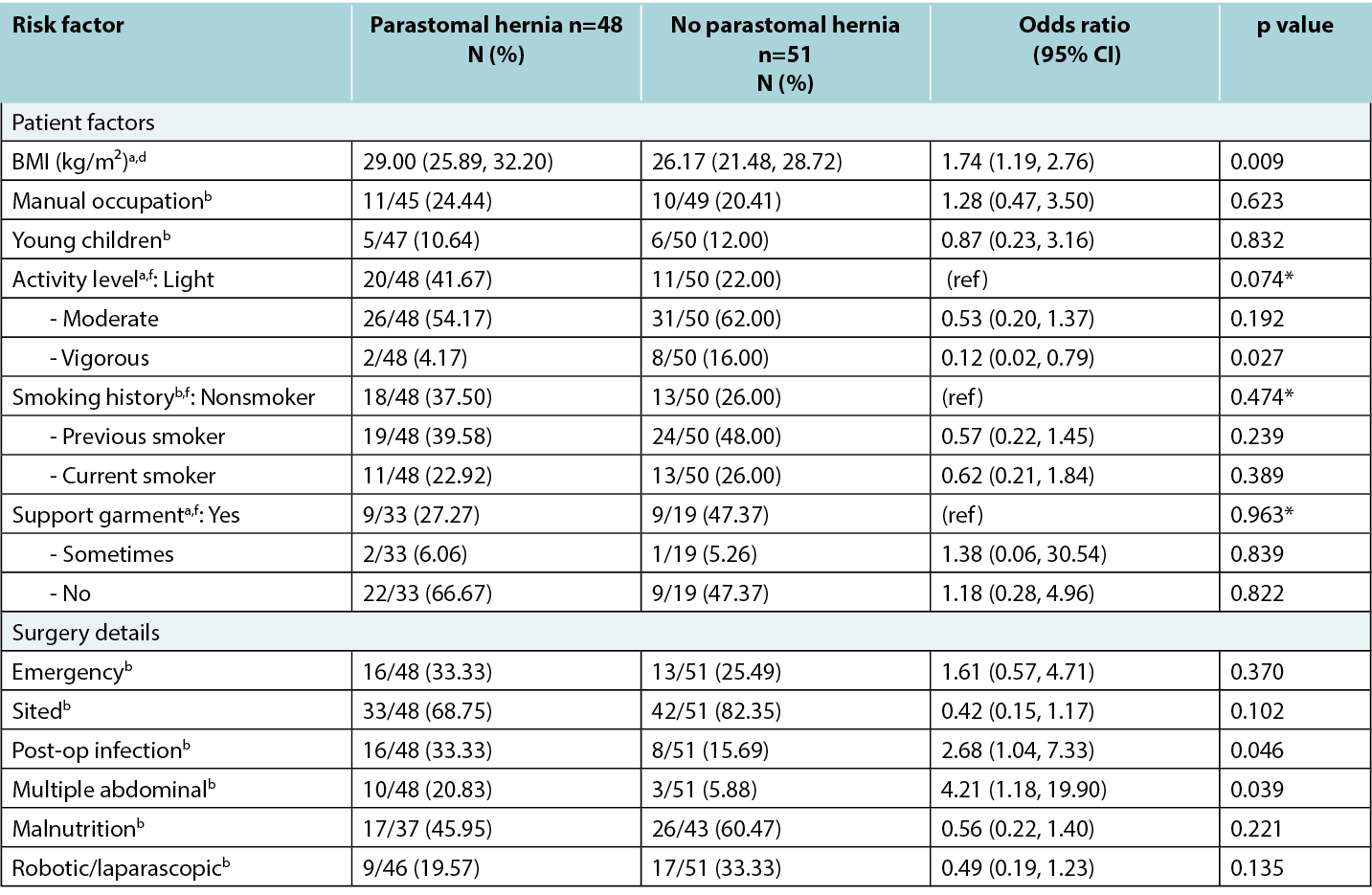

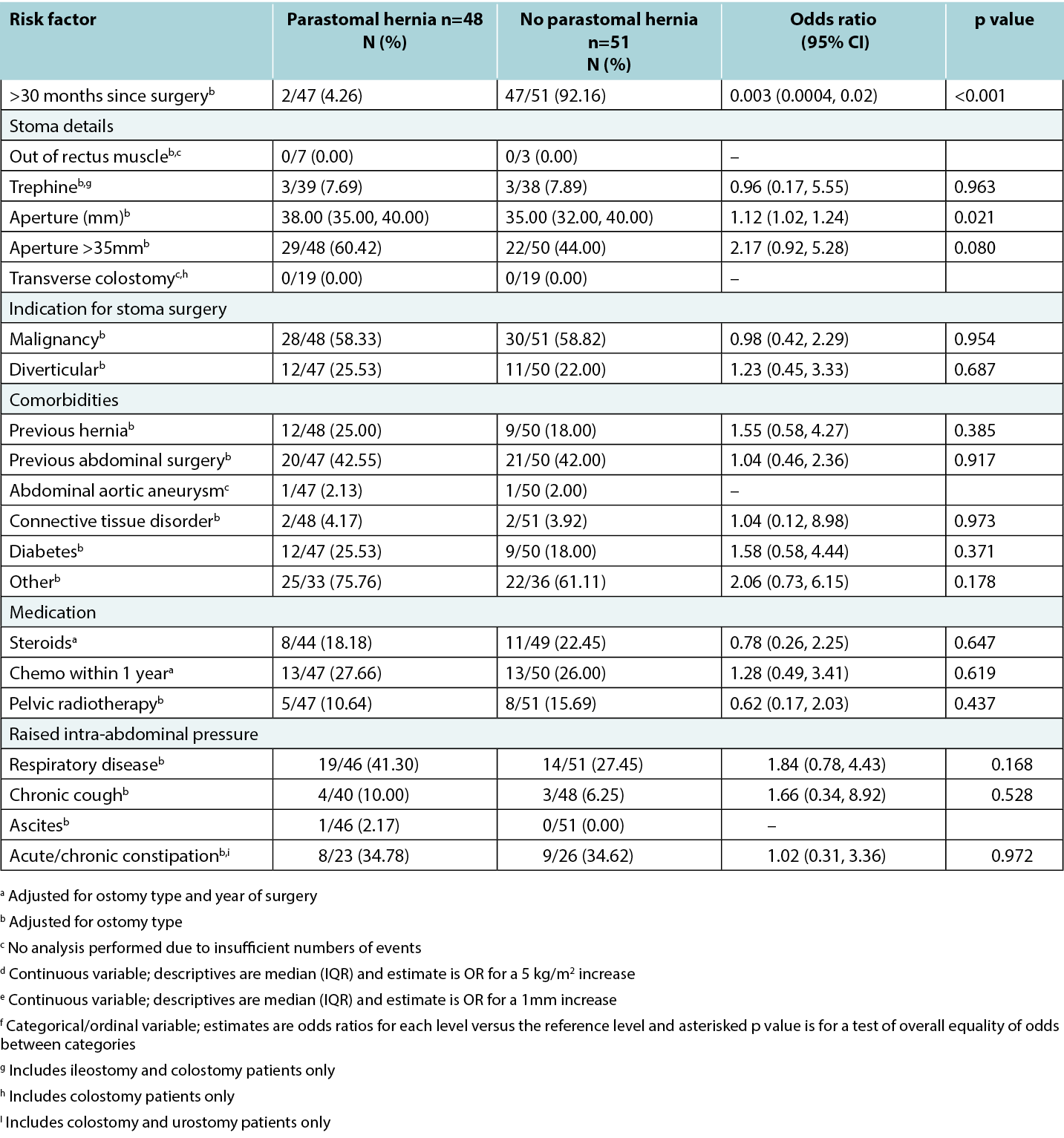

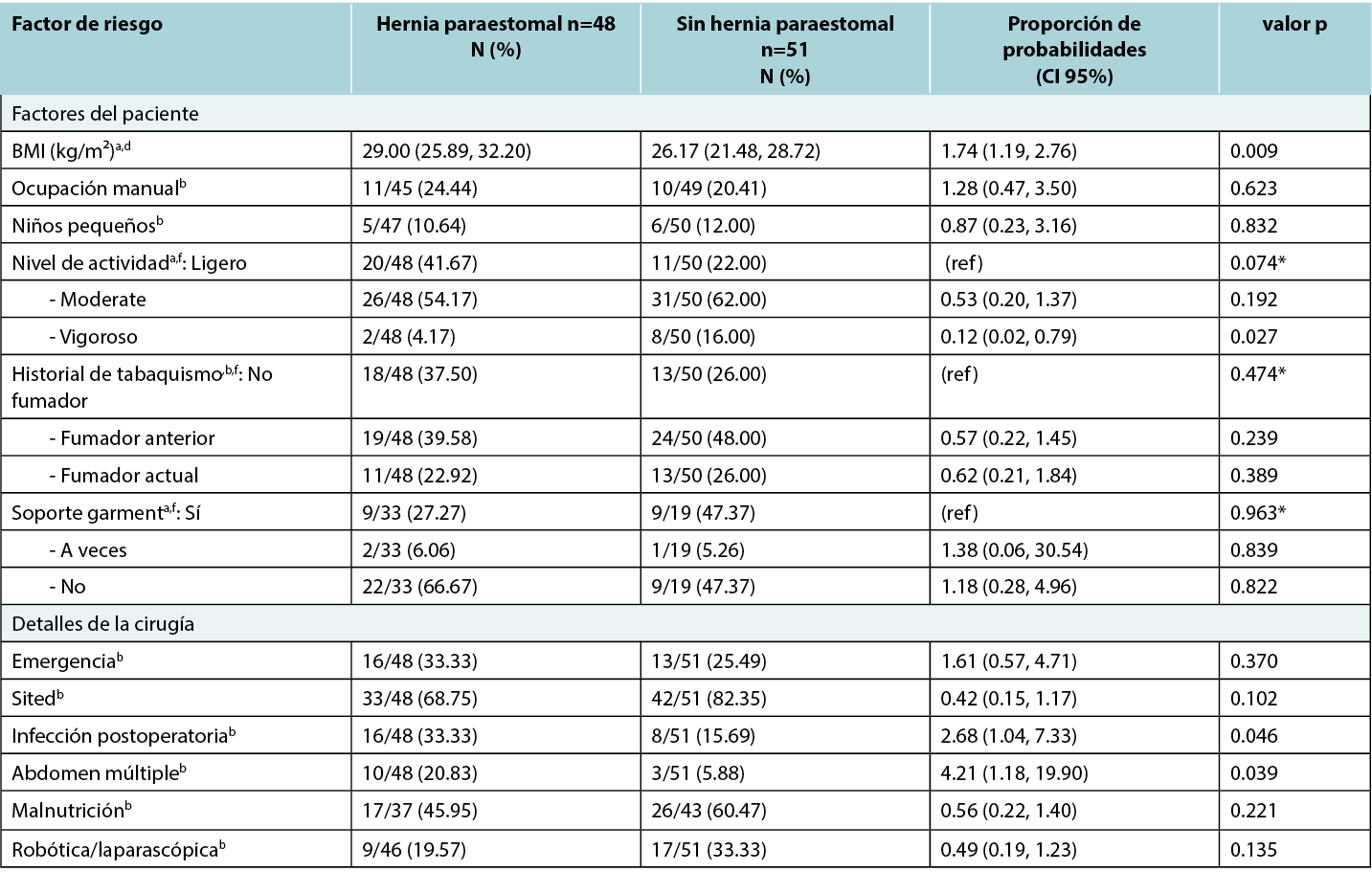

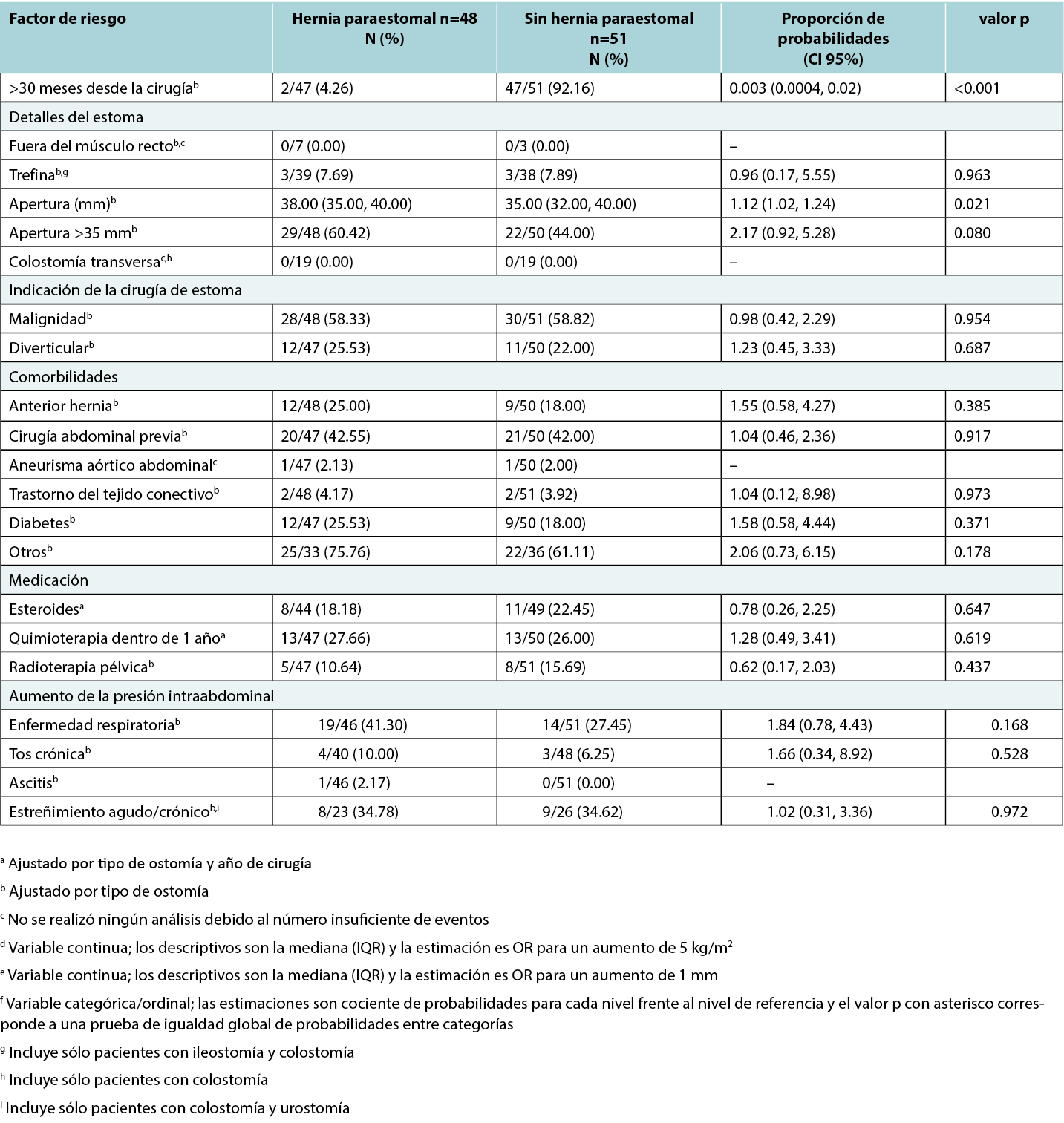

Table 2 reports results of univariable analyses of all risk factors. For most factors there was no evidence of an association with risk of developing parastomal hernia; however, there was evidence of an increased risk of parastomal hernia with higher BMI (OR for a 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI 1.74, 95% CI 1.19 to 2.76), and for increased aperture size (OR for 1mm increase in aperture size 1.12, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.24). The aperture size was identified from the patients’ case notes at first STN review post operatively (approx. day 1–3). The risk of parastomal hernia also decreased significantly at >30 months after surgery, with an odds ratio of 0.003 (95% CI: 0.0004 to 0.02). For other factors, there was some evidence that multiple abdominal surgery and post-operative infection increased the risk of parastomal hernia; however, due to relatively small numbers, the confidence intervals for the estimated odds ratios were too wide to be meaningful. Similarly, there was some evidence that higher levels of activity reduce the risk of parastomal hernia, with a statistically significant decrease in odds for those whose activity level was ‘vigorous’ compared to ‘light’. However, there were only small numbers of participants with this level of activity, limiting statistical power.

Table 2. Results of univariable analyses of all risk factors.

In some cases, potential risk factors could not be analysed due to small numbers; for example, only one participant had ascites and only two experienced abdominal aortic aneurysms. Stoma placed out of the rectus muscle had no recorded instances. Siting within the rectus sheath could not be ascertained from medical notes for the majority of participants since it was not clearly documented either before or after surgery. While the proportion of Ostomates using support garments was considerably higher in Ostomates without a parastomal hernia evidence of this relationship was not statistically significant. This may have been due to a large proportion of missing data, especially in the control group, decreasing the power to detect the nature of the relationship.

Subgroup analysis by ostomy type

Subgroup analysis did not reveal any evidence of differences between type of ostomy in the relationship between potential risk factors and development of parastomal hernia. It is prudent to be mindful, however, that this does not mean that no differences exist, as in many cases, the numbers were too small when broken down by ostomy type for analysis to be sensible.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify risk factors that appear to have strongest association with development of a parastomal hernia. It is anticipated that the results will help to refine current risk assessment tools and provide other clinicians and researchers working with Ostomates with a protocol to replicate and gather further evidence regarding parastomal hernia risk.

Completing the case note review

The process of the case note review is outlined in the methods section; however, some additional issues should be highlighted given the invitation to replicate. The review found that many patients had a long history of medical care and so it was not unusual to have a number (three to six) case note files reviewed for each patient which had not been factored into the allocation of time per patient review. Quality of information available within the patient case notes varied; while the reviewers were able to ascertain more precise information regarding body mass index and aperture size than anticipated, information regarding siting of stomas was not well documented. Additionally, documentation regarding discussion with patients on parastomal hernia prevention and support garment use was often only provided when patients had a parastomal hernia, leading to ascertainment bias; the reported results regarding support garment use are therefore possibly not a true reflection of the relationship with parastomal hernia.

The nature of the recording of two risk factors was enhanced during the review process. Following the UK risk assessment tool,12 obesity (BMI greater than 30) and stoma aperture size greater than 35mm had been added. However, documentation in the case notes allowed for the recording of these as continuous variables. Specifically, case notes included specific aperture size at first STN review post operative review, as well as height and weight of patients which allowed the reviewers to calculate specific body mass index. This is a strength of the study, as reporting aperture and body mass index as continuous variables allowed for higher statistical power and for specific odds ratios to be calculated, providing a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between body mass index and aperture size and parastomal hernia.

BMI

Results of this case note review indicate that patients with higher BMI or larger stoma aperture were more likely to develop a parastomal hernia. In particular, for every 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI, the chances of parastomal hernia increased 74%. This is a particularly important finding as the study’s population is known to have higher than average Body Mass Index, especially at the public hospital located in a lower socioeconomic area. A link between socioeconomic status and obesity has been established.16

Surgery related factors

Some evidence was also found regarding increase in parastomal hernia risk for patients with multiple abdominal surgeries and post-operative infection, however small numbers of patients with these risk factors affected the statistical power to determine risk. While previous literature,4,10,18,19,20,21 suggests increased parastomal hernia risk from some surgery-related factors (rectus muscle, trephine stoma; transverse colostomy) and ascites,22 these potential risk factors could not be examined due to insufficient data (i.e., the number of case notes with these features recorded was not high enough to calculate an odds ratio with sufficient power). Further, for every 1mm in increased aperture, the risk of hernia increased by 12%. This is consistent with previous literature reporting that for every millimetre increase in aperture size, the risk of parastomal hernia increased 10%.8 Additionally, a parastomal hernia is most likely to develop in the first 30 months post-surgery.

Smoking

Interestingly, while previous literature has suggested smoking to be a risk factor for parastomal hernia,12 no evidence of a relationship between smoking and parastomal hernia was found in this study. This was surprising given the tendency of smokers to cough, increasing intra-abdominal pressure and leading to abdominal straining.22 Overall, tobacco smokers are known to have poorer post-surgical outcomes, due to reduced oxygen and nutrient flow throughout the body, delaying healing.24 There is some suggestion that nicotine use may inhibit cell repair, however this has not been a focus of research within the context of parastomal hernia.17

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy

No evidence was found of a link between chemotherapy and radiotherapy within a year of surgery, and parastomal hernia development due to a weakening of muscles due to treatment. However, previous studies26 have shown a link. It is possible no effect was found in the recent study due to small sample size, and, therefore, this should be investigated further.

Overall, the significant findings of this study are in keeping with much of the previous literature,8,17,20,22 which reassures its relevance in the Australian setting and motivates the need for clarification on other potentially important factors that potentially require further study with more case notes.

Limitations

Consideration should be given to this study’s limitations. Firstly, while the pragmatic design was necessary given the clinical context of the research (busy metropolitan hospitals with non-digitised case notes), this did leave the study underpowered to detect potential risk for some factors, particularly co-morbidities and additional treatments, such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Future research could include prospective data collection of a powered sample from a multi-centric study with long follow-up of the risk factors for parastomal hernia.

Additionally, each hospital had its own protocols for documentation, assessment, and action. For example, one hospital has a pathway which directs staff to contact the diet aid or dietitian to assess a patient if their Body Mass Index is low, had lost significant weight unintentionally, or had poor appetite, while the other hospital employed a dietitian who undertook a comprehensive assessment, including routine blood tests e.g., iron, magnesium levels, regardless of BMI. Such differences in protocols may have affected the data.

The assessment of the heavy lifting risk factor was problematic as very little data was recorded in case notes, and any available notes were often ambiguous. This is not particularly surprising due to the subjective nature of the question. However, this meant occupational and recreational activities that required heavy lifting could not be adequately assessed as a risk factor.

Practices had changed over time at each of the hospitals. For example, in the case notes of one hospital, cases before 2021 generally made little reference to parastomal hernia education, however after 2021 this was consistently documented which again could impact the quality of the data collected.

Finally, reporting of the measurement of the stoma was undertaken from a pragmatic point of view as there is no consensus about when to measure the stoma post-operatively to determine the risk of parastomal hernia formation. It is understood that the stoma will change in size and shape post-operatively and generally be at a consistent size at 6 to 8 weeks. When a patient develops a parastomal hernia the stoma may change in size and shape.25 It was observed in the clinical setting at both hospital sites that patients were occasionally developing a parastomal hernia at or before 6 weeks post-operatively. Therefore, the decision was made to measure at the first review post-surgery for consistency. Hence the larger number of stomas over 35mm. The best time to measure an aperture with respect to understanding this as a risk factor is an area for future research.

While the matched case-control design of this study increases the chances of representative data, the issues outlined above mean the findings may not be generalisable more broadly to people with a stoma.

Conclusion

This study was the first of its kind in Australia to synthesise previous findings relating to parastomal hernia risk and to conduct a retrospective case note review to refine these risk factors. As parastomal hernias often impair an Ostomate’s quality of life,5 it is important to continue to understand the potential risk factors to better inform preventative management. By outlining the process of this study our hope is that it may guide future studies by clinicians and researchers in other health settings to enhance the necessary evidence of important risk factors.

High body mass index, postoperative infection, multiple surgeries, wide diameter of the stoma and time since surgery less than 30 months increased the risk of parastomal hernia, other factors did not reach significance probably due to use of an underpowered sample.

The research team found many issues of missing information, particularly related to patient factors, such as lifting and other lifestyle factors. It is recommended that tools to record activity (such as the metabolic equivalent of task15), and for lifting (the Dictionary of Occupational Title23) which are used in other settings and could be incorporated into stomal therapy nurses assessment process.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Divisional and Executive Nursing Directors of the two hospitals: (Northern Adelaide Local Health Network and St Andrews Hospital), South Australia, and Clinical Record Units for their assistance and support of this project.

We also acknoweldge the Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK (ASCN UK) Risk Assessment Tool which inspired us to undertake a series of research studies in Australia.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Statement

Central Adelaide Local Health Network Human Research Ethics Committee H-2020-231: St Andrews Hospital Number 138 and University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee Ref. 16705.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Adelaide. Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences.

Evaluación de los factores de riesgo para el desarrollo de una hernia paraestomal: un estudio retrospectivo de casos y controles emparejados

Lynette Cusack, Fiona Bolton, Kelly Vickers, Amelia Winter, Jennie Louise, Leigh Rushworth, Tammy Page, Amy Salter

DOI: 10.33235/wcet.44.2.20-28

Resumen

Objetivo Identificar los factores de riesgo que contribuyen con mayor probabilidad al desarrollo de una hernia paraestomal.

Métodos de estudio retrospectivo de casos y controles emparejados mediante revisiones retrospectivas de notas de casos. Un hospital público y otro privado de Australia Meridional. Los ostomizados que se sometieron a cirugía de formación de estoma entre 2018 y 2021, y desarrollaron ('casos', n=50) o no ('controles', n=50) hernia paraestomal fueron emparejados por tipo de ostomía. Se identificaron posibles factores de riesgo de hernia paraestomal a partir de la bibliografía y la opinión de expertos para crear una herramienta de revisión de casos clínicos. Las notas de casos se seleccionaron por fecha quirúrgica a partir de 2018. Se realizaron análisis en los que la regresión logística univariable investigó las relaciones entre los factores de riesgo potenciales y el desarrollo de hernia paraestomal. Los análisis exploratorios de subgrupos investigaron si las relaciones entre los factores de riesgo y el desarrollo de hernia paraestomal diferían según el tipo de ostomía.

Resultados Las características de los pacientes se resumieron de forma descriptiva y por hospitales. Se hallaron pruebas estadísticamente significativas de vínculos entre el desarrollo de hernia paraestomal y un mayor BMI (para un aumento de

5 kg/m2, OR: 1.74; 95% CI: 1.19, 2.76), infección postoperatoria (OR: 2.68; 95% CI: 1.04, 7.33), múltiples cirugías abdominales (OR: 4.21; 95% CI: 1.18, 19.90), tiempo transcurrido desde la cirugía (>30 meses, OR: 0.003; CI: 0.0004, 0.02) y tamaño de la abertura (para aumento de 1 mm, OR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.24). No se encontraron pruebas suficientes de las relaciones esperadas con factores como el tabaquismo, la quimioterapia y/o la radioterapia pélvica, el estilo de vida y los factores de actividad.

Conclusiones Este estudio contribuye a profundizar en la comprensión de las relaciones entre los factores de riesgo conocidos para informar la práctica de las enfermeras estomaterapeutas en la prevención de una hernia paraestomal.

El índice de masa corporal elevado, la infección postoperatoria, las cirugías múltiples, el diámetro amplio del estoma y el tiempo transcurrido desde la cirugía inferior a 30 meses aumentaron el riesgo de hernia paraestomal; otros factores no alcanzaron significación probablemente debido al uso de una muestra con poca potencia.

La posibilidad de repetir este estudio reforzaría aún más las pruebas necesarias sobre los factores de riesgo más importantes.

Antecedentes

Son varias las afecciones que pueden provocar la formación de un estoma intestinal, como el cáncer de intestino/recto y vejiga y la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Un estoma es una abertura creada quirúrgicamente en el abdomen que permite que las heces o la orina salgan del cuerpo a través de una colostomía, urostomía o ileostomía. Las cifras estimadas de ostomías varían en todo el mundo. Las cifras recientes en Estados Unidos superan las 725,000 personas;1 Las cifras europeas se estiman en torno a 700,000;2 y las cifras australianas son de aproximadamente 50,000.3 Una hernia paraestomal, cuando los intestinos presionan hacia fuera a través de un defecto de la pared abdominal en las proximidades del estoma, es una de las complicaciones más comunes que experimentan las personas (ostomizados) que se han sometido a una cirugía de formación de estoma.4 Aunque las tasas estimadas de desarrollo de hernia paraestomal varían, muchas estimaciones sugieren que alrededor del 50% de las personas con estoma desarrollarán una hernia paraestomal potencialmente prevenible.4 Las hernias paraestomales suelen ser dolorosas y molestas, lo que afecta a la calidad de vida del ostomizado.5,6,7

Una revisión sistemática de Zelga et al,8 identificó múltiples factores de riesgo que pueden contribuir a desarrollar una hernia paraestomal, entre ellos: índice de masa corporal (BMI); consumo abusivo de tabaco o alcohol; presencia de afecciones comórbidas (como diabetes mellitus, cardiopatía coronaria, hipertensión y enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica). También se identificaron varios factores relacionados con la cirugía, como el tipo de estoma (por ejemplo, en el intestino delgado o en el grueso, estoma en asa frente a estoma terminal, experiencia del cirujano), la posición del estoma en el abdomen y el contexto en el que se creó la ostomía (de urgencia frente a electiva). Otro factor identificado en la bibliografía es la desnutrición que provoca una mala curación del estoma o de la herida.9 Por último, algunas investigaciones sugieren que la hernia paraestomal es más probable que se produzca en mujeres que en hombres.10

El propósito de este artículo es, en primer lugar, informar de los resultados sobre los factores de riesgo más probables que contribuirían al desarrollo de una hernia paraestomal para perfeccionar las actuales herramientas de evaluación del riesgo de hernia paraestomal; y, en segundo lugar, documentar el proceso de realización de un estudio retrospectivo de casos y controles emparejados. Se espera que esto sirva de base a futuros investigadores para reforzar las pruebas disponibles y avanzar en la comprensión de los riesgos de desarrollar una hernia paraestomal. Las directrices STROBE para la notificación de estudios observacionales proporcionaron orientación sobre la notificación.11

Métodos

Diseño de la investigación

Se llevó a cabo un estudio retrospectivo de casos y controles emparejados mediante la revisión de notas de casos para identificar los factores de riesgo que parecen tener una mayor asociación con el desarrollo de hernia paraestomal después de la cirugía.

Configuración

La revisión de casos clínicos se llevó a cabo en dos centros: un gran hospital público metropolitano y un hospital metropolitano privado más pequeño de Australia Meridional, donde se practica la cirugía de estoma. En ambos hospitales trabajan enfermeras experimentadas en estomaterapia que colaboran estrechamente con cirujanos colorrectales para prestar apoyo a los ostomizados.

Participantes

La revisión retrospectiva de notas de casos consistió en dos grupos participantes de ostomizados que se sometieron a cirugía de formación de estoma entre 2018-2021. El grupo 1 eran "casos": una selección de notas de casos de algunos ostomizados, no todos, que desarrollaron una hernia paraestomal en este periodo de tiempo (después de la cirugía original) (n=50). El segundo grupo fueron los controles: una selección de notas de casos de ostomizados que no desarrollaron una hernia paraestomal entre 2018-2021(después de la cirugía original) (n=50), y se emparejaron proporcionalmente según el tipo de ostomía. La identificación y notificación de las hernias paraestomales fueron diagnosticadas de manera informal por enfermeras estomaterapeutas o mediante tomografías computerizadas confirmadas tras la revisión médica por sospecha de hernia paraestomal. La selección de las notas de casos fue secuencial, comenzando con las cirugías más tempranas de 2018. Debía seleccionarse el mismo número de notas de casos y de controles de cada uno de los dos hospitales, con la intención de que cada hospital proporcionara 25 notas de casos y 25 de controles. No obstante, esto no pudo lograrse debido a la disponibilidad de notas de casos en cada centro. Por lo tanto, se analizaron 99 notas de casos: 50 del hospital público (25 casos y 25 controles) y 49 del hospital privado (23 casos y 26 controles).

Para garantizar una representación adecuada del tipo de ostomía en cada uno de los dos hospitales (con diferentes perfiles de ostomía), se tomaron muestras intencionadas, o específicas, de las proporciones observadas aproximadas entre 2018 y 2021. En el hospital público, la proporción fue de 56% de ileostomía/40% de colostomía/4% de urostomía, mientras que en el hospital privado la proporción fue de 36% de ileostomía/36% de colostomía/28% de urostomía, lo que se corresponde con el porcentaje del tipo de cirugía de ostomía en cada hospital respectivo. Para alcanzar estas proporciones, esto significaba (por ejemplo) ignorar las notas de un tipo de ostomía si ya se había alcanzado la cuota requerida para ese tipo (véase la figura 1).

Figura 1. Formato para determinar el muestreo de cada hospital en función del tipo de ostomía y la presencia de hernia paraestomal.

Revisar la herramienta y las fuentes de datos

La herramienta de revisión de notas de casos se desarrolló mediante la identificación de factores de riesgo clave para las hernias paraestomales a partir de la bibliografía, la Herramienta de evaluación de riesgos Asociación de enfermeras estomaterapeutas del Reino Unido,12 dos estudios australianos previos sobre las percepciones de las enfermeras estomaterapeutas 13 y las experiencias vividas por los ostomizados.14 La naturaleza multidisciplinar del equipo de investigación fue fundamental en el desarrollo y la valoración de la herramienta de revisión para garantizar la aportación de la experiencia académica y clínica pertinente, incluida la fisioterapia, la estomaterapia y la psicología, así como una sólida comprensión de la base de pruebas (por parte de los bioestadísticos). Para garantizar la fiabilidad entre usuarios y la coherencia en la recogida de datos, cuatro miembros del equipo de investigación, que ocupaban puestos en cada hospital, probaron la herramienta de revisión final hasta alcanzar un acuerdo del 100% sobre los puntos de la herramienta de revisión. Se pilotaron cuatro notas de casos de cada uno de los grupos de casos y de control. Estas notas de casos no se incluyeron en la revisión final. La evaluación de los niveles de actividad resultó difícil cuando se puso a prueba la herramienta. Sin embargo, la decisión de incluir el equivalente metabólico de la tarea (frecuentemente denominado MET)15 lo hizo más factible. Los anestesistas solían utilizar esta herramienta, por lo que se registraba en la evaluación anestésica preoperatoria de los pacientes. Se introdujeron otros cambios menores en la redacción y los puntos de las herramientas de revisión para mejorar su claridad y pertinencia.

Recogida de datos y métodos estadísticos

A partir de los números de las notas de casos de los pacientes (registros de unidad), se seleccionaron las notas de casos para su revisión mediante una selección secuencial de una lista de cada hospital. Los cuatro investigadores de los dos hospitales participantes cumplimentaron manualmente la herramienta de revisión de las notas de casos, ya que ambos hospitales seguían utilizando notas de casos impresas.

Los datos de los formularios de revisión se importaron de Excel a R v4 (R Fundación para el Cálculo Estadístico) para su limpieza y posterior análisis, según un plan de análisis preespecificado. Las características de los pacientes se resumieron descriptivamente tanto en general como por centro de estudio. Las relaciones univariables entre los factores de riesgo potenciales preespecificados y el desarrollo de una hernia paraestomal se analizaron mediante regresión logística. Para los factores de riesgo binarios, las estimaciones se presentaron como cociente de probabilidades (OR) e intervalos de confianza (CI) del 95% para "sí" frente a "no"; para los factores de riesgo nominales u ordinales, las estimaciones se presentaron como OR y CI del 95% para cada nivel posterior frente a un nivel de referencia; y para los factores de riesgo continuos, las estimaciones se presentaron como OR y CI del 95% para un aumento estipulado. Todos los modelos se ajustaron por tipo de ostomía (variable utilizada para emparejar casos y controles), y algunos modelos se ajustaron adicionalmente por año de cirugía. También se realizó un análisis exploratorio de subgrupos para investigar si las relaciones entre los factores de riesgo y el desarrollo de hernia paraestomal diferían según el tipo de ostomía. Se incluyó en el modelo un término de interacción entre el tipo de ostomía y el factor de riesgo, y se obtuvieron estimaciones separadas del riesgo (como OR) para cada tipo de ostomía.

Etica

Este proyecto recibió la aprobación de los Comités de Ética en Investigación Humana de los hospitales públicos y privados: Central Adelaida Red sanitaria local Ref 16705: St Andrews Hospital Número 138: Universidad de Adelaida H-2020-231. El equipo de investigación solicitó la dispensa del consentimiento del paciente a cada Comité de Ética, que fue aprobada basándose en la garantía de anonimato y confidencialidad al no comunicar información identificable sobre las personas. Durante la recogida de datos se siguieron procesos estrictos de acceso y almacenamiento de las notas de los casos de acuerdo con la política de cada hospital.

Resultados

Proceso y estadísticas descriptivas

El enfoque del estudio de casos y controles emparejados fue necesariamente pragmático, dado que el número de notas de casos revisadas estaba limitado por el tiempo de que disponían los investigadores y la capacidad de acceder a las notas de casos dentro del hospital. Como ninguno de los dos hospitales disponía de registros electrónicos, se accedió a las notas originales de los casos en papel. Este proceso llevó mucho tiempo. En la Tabla 1 se presentan las características de los participantes incluidos, por estado de caso/control y en general. Las cifras de casos (hernia paraestomal) y controles (sin hernia paraestomal) no son exactamente iguales para cada tipo de ostomía. Las características de los pacientes diferían ligeramente entre los casos y los controles, siendo los casos ligeramente mayores (mediana de edad de 70.37 años frente a 66.11 años en los controles), con mayor probabilidad de ser varones (64.6% de los casos frente a 52.9% de los controles) y con un peso medio más elevado (87.5 kg frente a 75.2 kg en los controles). La tasa de seguimiento por parte de las enfermeras estomaterapeutas fue del 100% en ambos grupos, y la proporción de pacientes que recibieron educación específica sobre la hernia paraestomal antes del desarrollo de una hernia fue similar en los casos (39.6%) y en los controles (39.2%).

Las características de los pacientes fueron similares en los dos centros de estudio (véase la Tabla 1).

Tabla 1. Características de los participantes por estatus de caso/control y global.

Posibles factores de riesgo

En la tabla 2 se presentan los resultados de los análisis univariables de todos los factores de riesgo. Para la mayoría de los factores no hubo pruebas de una asociación con el riesgo de desarrollar hernia paraestomal; sin embargo, hubo pruebas de un mayor riesgo de hernia paraestomal con un mayor BMI (para un aumento de 5 kg/m2 en el BMI, OR: 1.74; 95% CI: 1.19 a 2.76), y para un mayor tamaño de la apertura (para un aumento de 1 mm en el tamaño de la apertura, OR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.02 a 1.24). El tamaño de la abertura se identificó a partir de las notas del caso de los pacientes en la primera revisión del STN tras la operación (aproximadamente entre el 1 y el 3er día). El riesgo de hernia paraestomal también disminuyó significativamente a los >30 meses de la cirugía, con un cociente de probabilidades de 0.003 (95% CI: 0.0004 a 0.02). En cuanto a otros factores, hubo algunas pruebas de que la cirugía abdominal múltiple y la infección postoperatoria aumentaban el riesgo de hernia paraestomal; sin embargo, debido a los números relativamente pequeños, los intervalos de confianza para los cocientes de probabilidades estimados eran demasiado amplios para ser significativos. Del mismo modo, hubo algunas pruebas de que los niveles más altos de actividad reducen el riesgo de hernia paraestomal, con una disminución estadísticamente significativa de las probabilidades para aquellos cuyo nivel de actividad era "vigoroso" en comparación con "ligero". Sin embargo, sólo había un pequeño número de participantes con este nivel de actividad, lo que limitaba la potencia estadística.

Tabla 2. Resultados de los análisis univariables de todos los factores de riesgo.

En algunos casos, los factores de riesgo potenciales no pudieron analizarse debido al reducido número de participantes; por ejemplo, sólo un participante tenía ascitis y sólo dos sufrían aneurismas aórticos abdominales. No se ha registrado ningún caso de estoma colocado fuera del músculo recto. En la mayoría de los casos no se pudo determinar la localización en la vaina del recto a partir de las notas médicas, ya que no estaba claramente documentada ni antes ni después de la intervención. Aunque la proporción de ostomizados que utilizaban prendas de soporte era considerablemente mayor en los ostomizados sin hernia paraestomal, las pruebas de esta relación no eran estadísticamente significativas. Esto puede deberse a la gran proporción de datos que faltan, especialmente en el grupo de control, lo que reduce la capacidad de detectar la naturaleza de la relación.

Análisis de subgrupos por tipo de ostomía

El análisis de subgrupos no reveló ninguna evidencia de diferencias entre el tipo de ostomía en la relación entre los factores de riesgo potenciales y el desarrollo de hernia paraestomal. Sin embargo, es prudente tener en cuenta que esto no significa que no existan diferencias, ya que en muchos casos, las cifras eran demasiado pequeñas cuando se desglosaban por tipo de ostomía para que el análisis fuera sensato.

Discusion

El objetivo de este estudio era identificar los factores de riesgo que parecen estar más relacionados con el desarrollo de una hernia paraestomal. Se prevé que los resultados ayudarán a perfeccionar las herramientas actuales de evaluación del riesgo y proporcionarán a otros clínicos e investigadores que trabajen con ostomizados un protocolo para reproducir y reunir más pruebas sobre el riesgo de hernia paraestomal.

Completar la revisión de las notas del caso

El proceso de revisión de las notas de casos se describe en la sección de métodos; sin embargo, cabe destacar algunas cuestiones adicionales, dada la invitación a la repetición. En la revisión se observó que muchos pacientes tenían un largo historial de atención médica, por lo que no era inusual que se revisaran varios expedientes (de tres a seis) por cada paciente, lo que no se había tenido en cuenta en la asignación de tiempo por revisión de paciente. La calidad de la información disponible en las notas de los casos de los pacientes variaba; aunque los revisores pudieron obtener información más precisa de lo previsto sobre el índice de masa corporal y el tamaño de la abertura, la información relativa a la localización de los estomas no estaba bien documentada. Además, la documentación relativa a la conversación con los pacientes sobre la prevención de la hernia paraestomal y el uso de prendas de sujeción a menudo sólo se facilitaba cuando los pacientes tenían una hernia paraestomal, lo que daba lugar a un sesgo de constatación; por lo tanto, los resultados comunicados sobre el uso de prendas de sujeción posiblemente no reflejen fielmente la relación con la hernia paraestomal.

La naturaleza del registro de dos factores de riesgo se mejoró durante el proceso de revisión. Siguiendo la herramienta de evaluación de riesgos del UK12, se añadieron la obesidad (BMI superior a 30) y el tamaño de la abertura del estoma superior a 35 mm. Sin embargo, la documentación de las notas del caso permitió registrarlas como variables continuas. En concreto, las notas de los casos incluían el tamaño específico de la abertura en la primera revisión del STN tras la revisión quirúrgica, así como la altura y el peso de los pacientes, lo que permitió a los revisores calcular el índice de masa corporal específico. Este es uno de los puntos fuertes del estudio, ya que la presentación de la apertura y el índice de masa corporal como variables continuas permitió una mayor potencia estadística y el cálculo de cocientes de probabilidades específicos, lo que proporcionó una comprensión más matizada de la relación entre el índice de masa corporal y el tamaño de la apertura y la hernia paraestomal.

BMI

Los resultados de esta revisión de casos indican que los pacientes con mayor BMI o mayor apertura del estoma tenían más probabilidades de desarrollar una hernia paraestomal. En concreto, por cada 5 kg/m2 de aumento del BMI, las probabilidades de hernia paraestomal aumentaban un 74%. Se trata de un hallazgo especialmente importante, ya que se sabe que la población del estudio presenta un Índice de Masa Corporal superior a la media, sobre todo en el hospital público situado en una zona socioeconómica baja. Se ha establecido una relación entre el estatus socioeconómico y la obesidad.16

Factores relacionados con la cirugía

También se encontraron algunas pruebas sobre el aumento del riesgo de hernia paraestomal en pacientes con múltiples cirugías abdominales e infección postoperatoria, aunque el pequeño número de pacientes con estos factores de riesgo afectó a la potencia estadística para determinar el riesgo. Aunque la bibliografía previa,4,10,18,19,20,21 sugiere un mayor riesgo de hernia paraestomal por algunos factores relacionados con la cirugía (músculo recto, estoma trepanado; colostomía transversa) y ascitis,22 estos posibles factores de riesgo no pudieron examinarse debido a la insuficiencia de datos (es decir, el número de notas de casos con estas características registradas no era lo suficientemente alto como para calcular una odds ratio con suficiente potencia). Además, por cada 1 mm de mayor apertura, el riesgo de hernia aumentaba en un 12%. Esto concuerda con la literatura previa que informa de que por cada milímetro de aumento en el tamaño de la apertura, el riesgo de hernia paraestomal aumentaba un 10%.8 Además, es más probable que se desarrolle una hernia paraestomal en los primeros 30 meses postoperatorios.

Fumar

Curiosamente, mientras que la literatura previa ha sugerido que el tabaquismo es un factor de riesgo para la hernia paraestomal,12 en este estudio no se hallaron pruebas de una relación entre el tabaquismo y la hernia paraestomal. Esto fue sorprendente dada la tendencia de los fumadores a toser, lo que aumenta la presión intraabdominal y provoca distensión abdominal.22 En general, se sabe que los fumadores de tabaco tienen peores resultados posquirúrgicos, debido a la reducción del flujo de oxígeno y nutrientes por todo el cuerpo, lo que retrasa la curación.24 Hay indicios de que el consumo de nicotina puede inhibir la reparación celular, pero esto no se ha investigado en el contexto de la hernia paraestomal.17

Quimioterapia y radioterapia

No se encontraron pruebas de una relación entre quimioterapia y radioterapia en el plazo de un año tras la cirugía, y el desarrollo de hernia paraestomal debido a un debilitamiento de los músculos debido al tratamiento. Sin embargo, estudios anteriores26 han demostrado la existencia de un vínculo. Es posible que no se encontrara ningún efecto en el estudio reciente debido al pequeño tamaño de la muestra y, por lo tanto, esto debería investigarse más a fondo.

En general, los hallazgos significativos de este estudio están en consonancia con gran parte de la bibliografía anterior,8,17,20,22 lo que reafirma su relevancia en el entorno australiano y motiva la necesidad de aclarar otros factores potencialmente importantes que podrían requerir un estudio más profundo con más notas de casos.

Limitaciones

Hay que tener en cuenta las limitaciones de este estudio. En primer lugar, aunque el diseño pragmático era necesario dado el contexto clínico de la investigación (hospitales metropolitanos de gran actividad con notas de casos no digitalizadas), esto hizo que el estudio no tuviera la potencia suficiente para detectar el riesgo potencial de algunos factores, en particular las comorbilidades y los tratamientos adicionales, como la quimioterapia o la radioterapia. La investigación futura podría incluir la recopilación prospectiva de datos de una muestra potenciada de un estudio multicéntrico con un seguimiento prolongado de los factores de riesgo de hernia paraestomal.

Además, cada hospital tenía sus propios protocolos de documentación, evaluación y actuación. Por ejemplo, un hospital tiene una vía que indica al personal que se ponga en contacto con el asistente dietético o el dietista para evaluar a un paciente si su Índice de Masa Corporal es bajo, si ha perdido mucho peso de forma involuntaria o si tiene poco apetito, mientras que el otro hospital contrató a un dietista que realizó una evaluación exhaustiva, incluidos análisis de sangre rutinarios, por ejemplo, de los niveles de hierro y magnesio, independientemente del BMI. Estas diferencias en los protocolos pueden haber afectado a los datos.

La evaluación del factor de riesgo de levantamiento de objetos pesados fue problemática, ya que se registraron muy pocos datos en las notas de los casos, y las notas disponibles eran a menudo ambiguas. Esto no es especialmente sorprendente debido a la naturaleza subjetiva de la pregunta. Sin embargo, esto significaba que las actividades ocupacionales y recreativas que requerían levantar objetos pesados no podían evaluarse adecuadamente como factor de riesgo.

Las prácticas habían cambiado con el tiempo en cada uno de los hospitales. Por ejemplo, en las notas de casos de un hospital, los casos anteriores a 2021 apenas hacían referencia a la educación sobre hernias paraestomales, mientras que a partir de 2021 se documentaron sistemáticamente, lo que de nuevo podría afectar a la calidad de los datos recopilados.

Por último, el informe sobre la medición del estoma se realizó desde un punto de vista pragmático, ya que no existe consenso sobre cuándo medir el estoma en el postoperatorio para determinar el riesgo de formación de hernia paraestomal. Se entiende que el estoma cambiará de tamaño y forma en el postoperatorio y que, por lo general, tendrá un tamaño constante a las 6 u 8 semanas. Cuando un paciente desarrolla una hernia paraestomal, el estoma puede cambiar de tamaño y forma.25 Se observó en el entorno clínico de ambos hospitales que los pacientes desarrollaban ocasionalmente una hernia paraestomal a las 6 semanas del postoperatorio o antes. Por lo tanto, se tomó la decisión de medir en la primera revisión postoperatoria por consistencia. De ahí el mayor número de estomas de más de 35 mm. El mejor momento para medir una apertura con respecto a entender esto como un factor de riesgo es un área para futuras investigaciones.

Aunque el diseño de casos y controles emparejados de este estudio aumenta las posibilidades de que los datos sean representativos, los problemas señalados anteriormente implican que los resultados pueden no ser generalizables a las personas con estoma.

Conclusión

Este estudio fue el primero de este tipo en Australia en sintetizar los hallazgos previos relacionados con el riesgo de hernia paraestomal y en realizar una revisión retrospectiva de notas de casos para refinar estos factores de riesgo. Dado que las hernias parastomales suelen mermar la calidad de vida del ostomizado,5 es importante seguir conociendo los posibles factores de riesgo para informar mejor sobre la gestión preventiva. Al esbozar el proceso de este estudio, esperamos que pueda servir de guía para futuros estudios de clínicos e investigadores en otros entornos sanitarios, con el fin de aumentar las pruebas necesarias de factores de riesgo importantes.

El índice de masa corporal elevado, la infección postoperatoria, las cirugías múltiples, el diámetro amplio del estoma y el tiempo transcurrido desde la cirugía inferior a 30 meses aumentaron el riesgo de hernia paraestomal; otros factores no alcanzaron significación probablemente debido al uso de una muestra con escasa potencia.

El equipo de investigación encontró muchos problemas de falta de información, sobre todo relacionados con factores del paciente, como la elevación de peso y otros factores del estilo de vida. Se recomienda utilizar herramientas de registro de la actividad (como el equivalente metabólico de la tarea115) y para el levantamiento (el Diccionario de Títulos Ocupacionales23) que se utilizan en otros entornos y que podrían incorporarse al proceso de evaluación de las enfermeras de estomaterapia.

Agradecimientos

Gracias a los Directores de División y Ejecutivos de Enfermería de los dos hospitales: (Red Sanitaria Local de Adelaida Septentrional y Hospital Meridional St Andrews) y a las Unidades de Registros Clínicos por su ayuda y apoyo a este proyecto.

También queremos expresar nuestro reconocimiento a la herramienta de evaluación de riesgos de la Asociación de enfermeras estomaterapeutas del Reino Unido (ASCN UK), que nos inspiró para emprender una serie de estudios de investigación en Australia.

Conflicto de intereses

Los autores declaran no tener conflictos de intereses.

Declaración Etica

Comité Ético de Investigación Humana de la Red Local de Salud de Adelaida Central H-2020-231: Hospital St Andrews Número 138 y Comité de Ética en Investigación Humana de la Universidad de Adelaida Ref. 16705.

Financiación

Este trabajo ha contado con el apoyo de la Universidad de Adelaida. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas y de la Salud.

Author(s)

Lynette Cusack*

PhD

University of Adelaide, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences,

Northern Adelaide Local Health Network SA Health,

Lyell McEwin and Modbury Hospitals, Adelaide, Australia

Email lynette.cusack@adelaide.edu.au

Fiona Bolton

BNurs

St Andrews Hospital, Adelaide, Australia

Kelly Vickers

BNurs

Northern Adelaide Local Health Network SA Health,

Lyell McEwin and Modbury Hospitals, Adelaide, Australia

Amelia Winter

BPsychSci (Hons)

University of Adelaide, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences,

Adelaide, Australia

Jennie Louise

PhD Biostatistics

Biostatistics Unit, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide, Australia

Leigh Rushworth

MAdvClinPhysio (cardiorespiratory)

University of Adelaide, School of Allied Health Science and Practice, Adelaide, Australia

Tammy Page

PhD

University of Adelaide, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences,

St Andrews Hospital, Adelaide, Australia

Amy Salter

PhD Biostatistics

University of Adelaide, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences,

Adelaide, Australia

* Corresponding author

References

- United Ostomy Associations of America. Living with an Ostomy: FAQs 2022. https://www.ostomy.org/living-with-an-ostomy/

- Malik T, Lee MJ, Harikrishnan AB. The incidence of stoma related morbidity: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2018;100(7):501–8.

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. About the Stoma Appliance Scheme 2023. https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/stoma-appliance-scheme/about-the-stoma-appliance-scheme.

- Antoniou SA, Agresta F, Garcia Alamino JM, Berger D, Berrevoet F et al. European Hernia Society guidelines on prevention and treatment of parastomal hernias. Hernia. 2018;22:183–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1697-5

- van Dijk SM, Timmermans L, Deerenberg E, Lamme B, Kleinrensink G-J, Jeekel J, et al. Parastomal hernia: Impact on quality of life? World Journal of Surgery. 2015;39(10):2595–2601.

- Claessens I, Probert R, Tielemans C, Steen A, Nilsson C, Andersen BD, et al. The ostomy life study: the everyday challenges faced by people living with a stoma in a snapshot. Gastrointestinal Nursing. 2015;13(5):18–25.

- van Ramshorst GH, Eker HH, Hop WCJ, Jeekel J, Lange JF. Impact of incisional hernia on health-related quality of life and body image: a prospective cohort study. The American Journal of Surgery. 2012;204(2):144–150.

- Zelga P, Kluska P, Zelga M, Piasecka-Zelga J, Dziki A. Patient-related factors associated with stoma and peristomal complications following fecal ostomy surgery: a scoping review. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing. 2021;48(5):415–430.

- Sohn YJ, Moon SM, Shin US, Jee SH. Incidence and risk factors of parastomal hernia. Journal of the Korean Society of Coloproctology. 2012;28(5):241–246.

- Shiraishi T, Nishizawa Y, Ikeda K, Tsukada Y, Sasaki T, Ito M. Risk factors for parastomal hernia of loop stoma and relationships with other stoma complications in laparoscopic surgery era. BMC surgery. 2020;20(1):141 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00802-y

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of obser-vational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2008;61(4):344–349.

- Association of Stoma Care Nurses United Kingdom. Stoma care national guidelines: parastomal hernia prevention. 2016. https://ascnuk.com/_userfiles/pages/files/national_guidelines.pdf Accessed 6 June 2023.

- Perrin A. Vice Chairpersons Report 2023. Association of Stoma Care Nurses United Kingdom. 2023. https://ascnuk.com/_userfiles/pages//files/committeeroles/report//vice_chair_persons_report_2024.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2024.

- Cusack L, Salter A, Vickers K, Bolton F, Winter A, Rushworth L. Perceptions and experience on the use of support garments to prevent parastomal hernias: a national survey of Australian stomal therapy nurses. Journal of Stomal Therapy Australia. 2022;42(4):18–25.

- Winter A, Cusack L, Bolton F, Vickers K, Rushworth L, Salter A. Perceptions and attitudes of ostomates towards support garments for prevention and treatment of parastomal hernia: A qualitative study. Journal of Stomal Therapy Australia. 2022;42(3):19–24.

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S498-S516.

- Anekwe CV, Jarrell AR, Townsend MJ, Gaudier GI, Hiserodt JM, Stanford FC. Socioeconomics of obesity. Current obesity reports. 2020;9(3):272–279.

- McGrath A, Porrett T, Heyman B. Parastomal hernia: an exploration of the risk factors and the implications. British Journal of Nursing. 2006;15(6):317–321.

- Martin L, Foster G. Parastomal hernia. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1996;78(2):81–84.

- Aquina CT, Iannuzzi JC, Probst CP, Kelly KN, Noyes K, et al. Parastomal hernia: A growing problem with new solutions. Digestive Surgery. 2014;31:366–376. DOI: 10.1159/000369279

- Tivenius M, Nasvall P, Sandblom G. Parastomal hernias causing symptoms or requiring surgical repair after colorectal cancer surgery—a national population-based cohort study. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2019;34:1267–1272 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03292-4

- Manole TE, Daniel I, Alexandria B, Dan PN, Andronic O. Risk factors for the development of parastomal hernia: a narrative review. Saudi Journal of Medicine & Medical Sciences 11(3). 2023 July-September; 11(3):187–192. https:/doi 10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_235_22

- Bower C, Roth JS. Economics of abdominal wall reconstruction. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2013;93(5):1241–1253.

- Dazhen L, Long Z, Changhai Y. The effect of preoperative smoking and smoke cessation on wound healing and infection in post-surgery subjects: A meta-analysis. Int Wound J.2022;19:2101–2106 DOI: 10.1111/iwj.13815

- Osborne W, North J, Williams J. Using a risk assessment tool for parastomal hernia prevention. British Journal of Nursing. 2018; 27(5):15–19. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2018.27.5.S15