Volume 40 Number 2

Therapeutic patient education; A multifaceted approach to healthcare

Laurence Lataillade and Laurent Chabal

Keywords Wound care, Therapeutic patient education, person-centred care, stomal therapy

For referencing Lataillade L and Chabal L . Therapeutic patient education; A multifaceted approach to healthcare. WCET® Journal 2020;40(2):35-42.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.2.35-42

Abstract

This contribution presents a literature review of therapeutic patient education (TPE) in addition to providing a summary of an oral presentation given by two wound care specialists at a European Congress. It relates this to models of care in nursing science and to other research that contributes to this approach at the core of healthcare practice.

Therapeutic patient education: an introduction to its practical application in patients with stomas and/or wounds

Up until 1970, educational approaches were rare and limited to a few isolated interventions such as the ‘manual for diabetics’. In 1972, Leona Miller, an American doctor, demonstrated the positive effects of patient education. Using a pedagogical approach, she enabled patients from under-resourced areas of Los Angeles living with diabetes to control their pathology and improve their independence by relying on less medication1.

In 1975, Professor Jean Philippe Assal, a diabetologist from Geneva, Switzerland, adopted this concept and created a department for the treatment and education of diabetes at Geneva University Hospitals. He created an innovative, interdisciplinary team consisting of nurses, physicians, dieticians, psychologists, caregivers, art therapists and physiotherapists, all with the goal of encouraging patient engagement in their learning2. The team was inspired by person-centred theories developed by Carl Rogers3, work by Kübler-Ross on the grief process4, contributions from Geneva on education science in adult learning, and work on the conceptions of learners of didactics and epistemology of science in Geneva.

Since then, therapeutic education of patients (TPE) has been developed for patients with different chronic diseases and disorders, such as asthma, pulmonary insufficiency, cancer, inflammatory bowel disease and, in particular, for patients with stomas and/or wounds. The aim of TPE is to assist patients and caregivers to better understand the nature of the disease a person has, the treatment strategies required and to help patients achieve a greater level of individual autonomy in how they manage and cope with their disease.

Definition of therapeutic patient education (TPE)

According to the World Health Organization (1998), TPE is education managed by healthcare providers trained in the education of patients, and is designed to enable a patient (or a group of patients and families) to manage the treatment of their condition and prevent avoidable complications, while maintaining or improving quality of life. Its principal purpose is to produce a therapeutic effect additional to that of all other interventions – pharmacological, physical therapy, etc. Therapeutic patient education is designed therefore to train patients in the skills of self-managing or adapting treatment to their particular chronic disease, and in coping processes and skills. It should also contribute to reducing the cost of long-term care to patients and to society. It is essential to the efficient self-management and to the quality of care of all long-term diseases or conditions, although acutely ill patients should not be excluded from its benefits.

Thus, “TPE should enable patients to acquire and maintain abilities that allow them to optimally manage their lives with their disease. It is therefore a continuous process that should be integrated into healthcare”5.

The premise of TPE as a healthcare approach is that it places the patient(s) or the caregiver(s) at the centre of the healthcare provider patient relationship, acknowledging them as an integral partner in healthcare processes6–8. The cornerstone of this approach is that the patient has knowledge, skills and experiences that must be valued, encouraged, stimulated and/or explored. As for health practitioners, they need to recognise and highlight the patient’s knowledge about themselves and capabilities, which requires the health practitioner to adapt their own position to care provision and education. Healthcare providers often tend to talk to patients about their disease rather than train them in daily management processes to assist patients to better manage their condition5. As Gottlieb explains9,10, it is more than a change in behaviour but a paradigmatic change that implores the practitioner to rely on the patient’s strengths rather than remedying their deficiencies and going further than Orem’s Model11 proposed.

TPE is a model of education and support for people living with one or more chronic diseases. The goal is to support the person being cared for by engaging them with their care by means of an educational program which makes sense for them and, in doing so, reduces the risk of complications12 and improves their quality of life. The tools of TPE promote a true collaboration between the patient and the healthcare practitioner. This requires a holistic, integrative and interdisciplinary approach13.

What is the objective of TPE? What position should practitioners adopt?

The goal for practitioners who employ TPE is to enable their patients to become independent in their care processes and to improve their quality of life. Nevertheless, patient goals are not always the same at every juncture. For example, the sudden arrival of the disease, such as a colonic cancer and the formation of a stoma, which is often a consequence thereof, have a major impact on the patient’s life. The ostomy patient goes through many emotional processes that are often profound and intense which sometimes overwhelms them completely.

Therapeutic patient education aims to support the patient in the stages and process of this emotional adjustment so that they can better adapt14 to and accommodate their disease and stoma in their day-to-day life. The goal is for the patient to acquire skills for managing their stoma and treatment as well as psychosocial skills to integrate their stoma into their daily life.

The challenge for practitioners is to reconcile these two types of learning in the TPE program while taking into account the difficulties encountered by the patient and their learning needs. A therapeutic relationship based on mutual trust and partnership is an indispensable condition for this educational process. In the framework of this alliance, the emphasis is placed on a relationship of moral equivalence between the patient and practitioner15.

The first educational stage within the TPE framework constitutes encouraging and making space for the patient to express themselves in order to reveal and agree on their particular needs which may not always be evident to either the patient or the health practitioner.

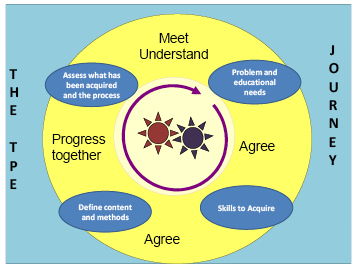

Figure 1. The TPE journey schema

In the TPE journey schema (the proposed Geneva TPE model), loosely translated from Lasserre Moutet et al.16 (Figure 1), the schema describes the following concepts:

- The two cog wheels in the middle represent the patient and the practitioner, both engaged in active movement. They both possess a specific knowledge base of their own. The practitioner possesses scientific knowledge, clinical skills and their clinical experience with other patients who have faced similar healthcare conditions; the patient possesses their individual lived experience with their disease and their treatment in addition to their own knowledge. Although this relationship is, by nature, asymmetric, it is nevertheless not ranked in terms of knowledge. The practitioner is a mediator who supports the patient in the process of transforming their knowledge to better understand their disease, consequences of the disease process and remedial medical interventions. For these gears to work, the rhythm must be adjusted. The first part of the TPE journey is especially important in upholding this engagement: the patient and practitioner must agree on the problem, revealing the reality of the situations that the patient encounters on a daily basis. For the practitioner, this involves developing a genuine interest in the patient and their life story with their disease.

- On the basis of this common understanding, educational needs, practical skills and competencies to be acquired by the patient will be elucidated in order for the patient to be able to overcome their difficulties or resolve their day-to-day problems.

- Once the goals are defined in conjunction with the patient, the strategies employed will lead the patient to encounter new ideas, to experience a new perspective on their situation, and to find alternatives to organise their daily life.

- Finally, the journey and the changes made will be evaluated jointly in order to make adjustments and continue the process.

This four-step approach can be carried out during one or more consultations.

What kind of therapeutic education should we use for patients with stomas?

Patients with stomas are confronted with physical changes and, often, a chronic disease17,18 which restricts their ability to envision a new reality for their life. One of the key roles of the stomal therapy nurse is to help the patient engage in suitable learning that will allow them to adapt, step by step, to a new life balance.

Whether the stoma is temporary or permanent, it is a shock and affects every aspect of the patient’s life: social and professional life, emotional and family life, personal identity and self-esteem. In situations where the stoma is temporary, it is often seen as a major obstacle in the person’s life for the period of time with which they live with the stoma. Once the intestine is reconnected, some patients dread that they will need a new stoma, which is indeed a possibility.

With the goal of patient independence with respect to the management of their care needs or, when this is not possible for the ostomy patient, for caregivers, stomal therapy nurses integrate TPE as a continuous process of comprehension of the patient’s lived experience and create a partnership, teaching and informing the patient throughout all stages of treatment – pre-operative, postoperative, rehabilitation, home care and short- or long-term follow-up.

This patient’s education focuses on different themes depending on the patient’s needs. For example, organisational aspects related to the stoma (care, changing the appliance, balanced digestion, food safety, etc.) which necessitate self-care. Some self-adjustment difficulties, such as a distorted self-image, low self-esteem and additional psycho-emotional implications19–21 and difficulty talking about the disease or stoma with their social circle, or resuming sexual activity, will most likely require the development of psychosocial coping skills and competencies to facilitate adaptation. The practitioner can thus apply their knowledge, clinical know-how and interpersonal skills to find appropriate teaching strategies for the patient or caregiver’s learning styles, all the while respecting/integrating patient’s limits, fears, and any resistance in order to lead them through each step of the process. Ultimately, successful integration of these processes will allow patients to perform their own self-care and adapt to their life with the ostomy and sometimes their chronic disease.

What stages do ostomy patients go through and how can we help them overcome them?

According to Selder22, the lived experience of a chronic disease is akin to a journey through a disturbed reality that is full of uncertainty and which, ultimately, leads to a restructuring of that reality.

In order to mobilise the patient’s resources, by working on their resilience23,24, consilience (coping skills)25 and empowerment26 skills, practitioners must take it upon themselves to meet the person and understand their representations, values and beliefs27,28 in order to incorporate them into their healthcare. These aspects, which are very much linked to the socio-cultural and religious context that the individual has assimilated, must also be considered in order to integrate them into the care provided to them29,30.

According to Bandura31,32, patients’ sense of self-efficacy relies on four aspects: personal mastery, modelling, social learning, and their physiological and emotional state. This generates three types of positive effects in patients with a good level of self-efficacy: the first relates to the choice of behaviours adopted, the second on the persistence of behaviours adopted, and the third on their great resilience in the face of unforeseen events and difficulties. Nurses who practise TPE will be able to mobilise, through their healthcare interventions, these four aspects of TPE for the purpose of inducing these three types of effects in the patient.

According to Diclemente et al.33, behavioural life changes can only be carried out in stages. In stomal therapy, these patient-centred approaches begin in the pre-operative stage where explanations are provided to the patient (and family where possible) on the potential need for the stoma, the surgical procedure and postoperative care (WCET® recommendation 3.1.2, SOE=B+29), even though the ostomy has not yet been confirmed. These recommendations have been adopted by the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society® (WOCN®)34.

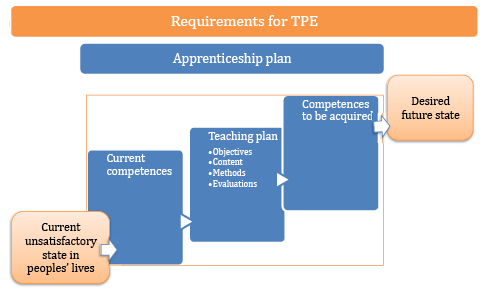

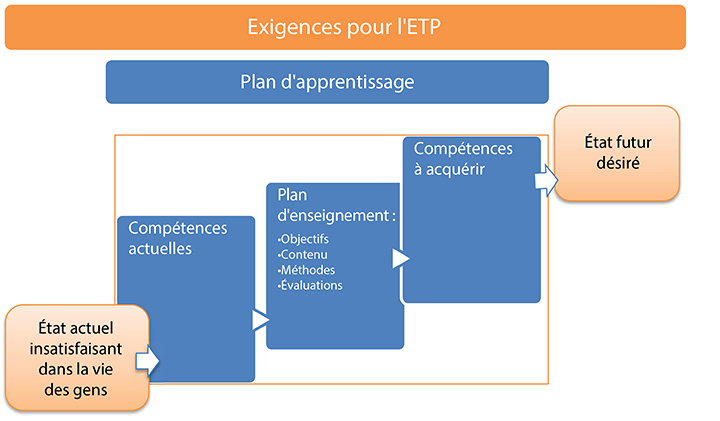

The schema, adapted and loosely translated from Martin and Savary35, describes the main steps of the learning process that need to be met and nurtured (Figure 2). Depending on the age of the patient, the knowledge, tools, and processes employed in adult education, TPE requirements may be necessary components to mobilise in order to attain them36,37. Other strategies will need to be adopted for younger populations, particularly with respect to adolescents38,39.

Figure 2. TPE requirements

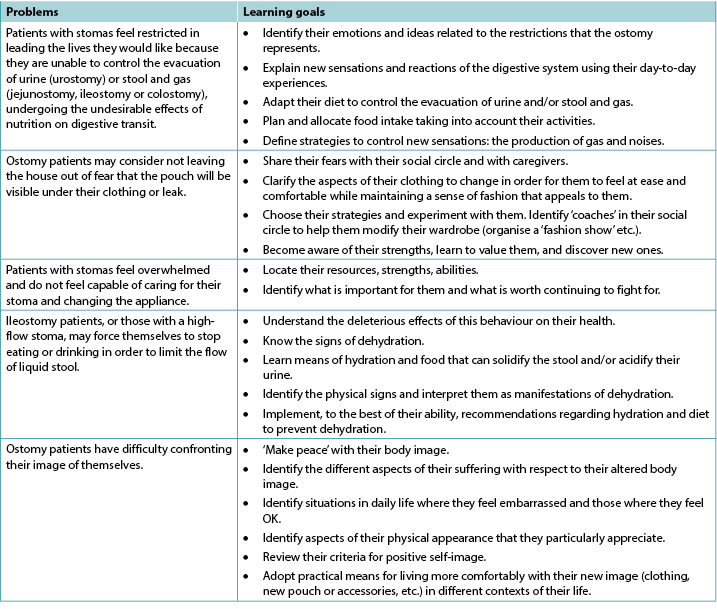

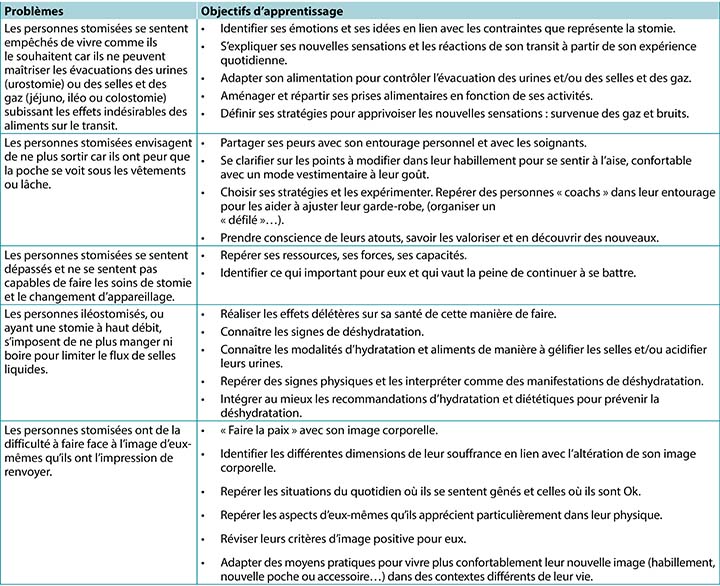

Examples of problems and goals in the therapeutic education of patients with stomas

These problems and instructional goals may apply for patients with incontinent ostomies, which are reflective of the most encountered scenarios (Table 1).

Table 1

In the case of patients with other, less common types of ostomy, like those with continent ostomies or nutritional support ostomies40,41, some of these items are still applicable and/or will need to be adapted to their particular situation; additional and more specific problems may apply. This is also the case for patients with enterocutaneous fistulae42.

In some situations, whether due to disgust, refusal, denial and/or disability (motor function, cerebral, psycho-emotional or psychiatric), the ostomy patient may not be able to undergo some or all of these processes of learning and empowerment43. This can be a short-term, medium-term or sometimes long-term problem. In these instances, recourse to a caregiver, whether a practitioner or a close relative, should be envisaged and organised. The educational process necessary for their empowerment must be carried out in a relatively similar manner with a view on promoting patient enabling to the maximum extent possible that allows the ostomy patient to return home. To the latter must be added supportive communication and management of and potential changes to interpersonal relationships and, potentially, to intimate relationships between the patients and their partners. Such changes can be generated by applying the principles of TPE, and this type of care and will need to be regularly re-evaluated and taken into consideration with a holistic approach to the patient and their respective situations.

These processes are even more complicated for patients who live alone at home, and even more so if they are elderly, as this can call their discharge home into question as well as their ability to remain at home. The need for strong communication relays and networks to be implemented in these circumstances recalls the advice offered within the 2012 American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) report45,46.

Lastly, the ostomy patient will occasionally find themselves with more than one stoma, all of which may be permanent (Figures 3 and 4). From our experience, these complex situations are more frequent than they were previously and are often related to malignant pathology.

Figure 3. Example of a person with a permanent left colostomy and a trans-ileal cutaneous ureterostomy (Bricker’s intervention) with purple urine bag syndrome47.

Figure 4. Example of a postoperative patient several days later with a temporary colostomy and a protective ileostomy. Digestive continuity would be restored in 9 months over two interventions, commencing with the downstream ostomy before the upstream ostomy, over an interval of a few weeks.

Insights and further information relating to patients with chronic wounds

Contrary to some preconceptions, stomal therapy is not solely concerned with the care of ostomy patients, even though the usage of the original term enterostomal therapist (ET)48 may lead to confusion. Indeed, the full Enterostomal Therapist Nursing Education Program (ETNEP)49 includes providing healthcare for people with wounds, people with continence disorders, those with enterocutaneous fistulae and, in some schools, for those with mastectomies. That said, wound care specialisation has become a specialist service unto itself and many ETs or stomal therapy nurses collaborate closely with wound specialists. It is important to note that these aspects of patient education are specified in the European curriculum for nurses specialising in wound care (Units 3 & 4)50–52.

In the literature, in reference to education provided to patients with wounds, knowledge has been described as a process of self-management, particularly among individuals living with a chronic disease such as a leg ulcer53. For education to be effective, the patient must acquire a perceived benefit from the changes that their involvement in the preventive activities proposed could generate. Physical, or emotional, benefits will reinforce the positive effects of the advice given54.

The benefit of using a multimedia teaching approach lies in the combination of methods for transmitting information. This helps resolve the problems encountered by the patient but also reinforces the information they are provided with55,56.

Numerous Cochrane Systematic Reviews have been carried out regarding patients with venous ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers and pressure injuries. They have revealed that:

- For patients with leg ulcers, there is not enough research available to assess strategies for supporting patients that would increase their adherence /compliance, despite the fact that compliance with compression is recognised as an important factor in preventing leg ulcer recurrence57.

- In relation to diabetic patients, there is not enough evidence to say that education – in the absence of other preventive measures – is sufficient to reduce the occurrence of foot lesions and foot/lower limb amputations58.

- Finally, as for pressure injuries, the authors have noted that the idea of patient involvement remains vague and includes a significant number of factors which vary and include a wide range of interventions and possible activities. At the same time, they clarify that this involvement in care, such as the respect of the rights of the patient, are important values which could play a role in their healthcare. This involvement could have the benefit of improving their motivation and knowledge in relation to their health. In addition, such involvement could entail an increase in their ability to manage their disease and to take care of themselves, thus improving their sense of security and enabling them to have better results when it comes to improving their health59.

As for patients with cancerous wounds, the European Oncology Nursing Society recommendations note the existence of scales for the evaluation of symptoms for the typology of these wounds, allowing for early detection of associated complications, as well as the reduction of care-related costs and of equipment used in healthcare, all the while improving patient involvement. Indeed, some of the tools described could be suggested to patients for them to use to assist with managing their condition60. In order for this to happen, education on their use will be necessary, despite the fact that these people may have lost confidence in themselves, their treatment, and their healthcare teams; even though their disease may have improved, their wounds still serve as visible stigmas of their disease.

Conclusion

Therapeutic education is the cornerstone of interventions conducted with individuals with chronic disease, or in chronic conditions, with the goal of health-related promotion, prevention and education. It is a fundamental activity that cuts across all the fields of the specialisation in stomal therapy. As every situation is unique, therapeutic education enables practitioners to develop skills in this area to improve the provision of care. It also incites us to innovate, be creative, adapt, and to think outside the box in order to find other interventional strategies; it also requires us to show humility, which may lead us to ask for help via our professional networks nationally and/or internationally.

According to Adams61, TPE remains a vast area of interventions in which the utility of educational interventions in improving healthcare impacts are still under discussion. However, the results of studies are still too limited to support their evidence. For other authors, the efficacy has, to date, been borne out by the research. For many hospitals, it is reportedly a cost-saving measure, as it enables shorter hospital stays and reduces the number of complications62–66.

Lastly, while the educational process starts at the hospital, it is followed up in both outpatient and home care services. In this sense, the implementation and maintenance of communication relays will be primordial in ensuring continuity of care, coherence and coordination of the processes undertaken as well as those of future stages that will be collaboratively decided upon. The involvement of family caregivers in these processes, with the consent of the patient and their relatives, is important. They serve as resources that cannot be neglected, even though their involvement may generate other issues that must be accounted for.

The training of healthcare professionals, particularly nurses, in the application of TPE will reinforce their expertise and efficiency67 in patient education, with the knowledge that every situation will push them to find new strategies and skills to overcome the challenges faced.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The wound section was partially based on notes taken during the University Conference Model (UCM) session68 on the subject. This session took place at the 2017 Congress of the European Wound Management Association (EWMA) in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and was presented by Julie Jordan O’Brien, Clinical Nurse Specialist Tissue Viability and Véronique Urbaniak, Advanced Practice Nurse69.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

L’éducation thérapeutique du patient, une approche soignante aux multiples enjeux

Laurence Lataillade and Laurent Chabal

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.2.35-42

Résumé

Cet article propose une revue de la littérature en lien avec l’éducation thérapeutique du patient (ETP) ainsi qu’un résumé de communication orale réalisé lors d’un congrès Européen par deux spécialistes en soins de plaies. Il fait le lien avec des modèles de soins en Science Infirmière et aux autres travaux contributifs à cette approche au cœur de la pratique soignante.

L’éducation thérapeutique du patient : une introduction à son application pratique auprès des personnes stomisées et/ou souffrant de plaies

Jusqu’en 1970 les approches éducatives sont rares et limitées à quelques démarches isolées types « manuel pour diabétiques ». C’est Leona Miller, une médecin américaine, qui, en 1972, démontre l’effet positif d’une éducation du malade. A l’aide d’une approche pédagogique, elle permet à des personnes atteintes de diabète issus de milieux défavorisés de Los Angeles de contrôler leur pathologie et à gagner en autonomie en consommant moins de médicaments1.

En 1975, l’idée de la démarche est reprise par le Professeur Jean Philippe Assal, médecin diabétologue à Genève en Suisse. Il crée au sein des Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève une unité de traitement et d’enseignement du diabète. Il innove en constituant une équipe interdisciplinaire, infirmier-e-s, médecins, diététicien-ne-s, psychologues, aide-soignant-e-s, art-thérapeutes et physiothérapeutes, tous acteurs pour favoriser l’engagement du patient dans son apprentissage2. Cette équipe s’inspire des théories de la relation centrée sur la personne de Carl Rogers3, des travaux de Kübler-Ross sur le vécu du deuil4, les apports des sciences de l’éducation de Genève sur le processus d’apprentissage des adultes ainsi que les travaux sur les conceptions des apprenants de didactique et d’épistémologie des sciences de Genève.

Depuis lors, l’éducation thérapeutique auprès de la personne soignée (abrégée ETP) s’est développée auprès de personnes atteintes de différentes maladies et affections chroniques, comme l’asthme, l’insuffisance pulmonaire, la cancérologie, les maladies inflammatoires chroniques de l’intestin (MICI) et notamment auprès des patients porteurs de stomies, et/ou de plaies. L’ETP a pour but d’aider les patients et les soignants à mieux comprendre la nature de la maladie d’une personne, les stratégies de traitement nécessaires et d’aider les patients à atteindre un plus haut niveau d’autonomie individuelle dans la façon dont ils gèrent et affrontent leur maladie.

Définition de l’ETP selon l’Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (1998)

Selon l’Organisation mondiale de la santé (1998), l’ETP est une éducation gérée par des prestataires de soins de santé formés à l’éducation des patients, et conçue pour permettre à un patient (ou à un groupe de patients et de familles) de gérer le traitement de son état et de prévenir les complications évitables, tout en maintenant ou en améliorant sa qualité de vie. Son objectif principal est de produire un effet thérapeutique complémentaire à celui de toutes les autres interventions - pharmacologiques, physiothérapie, etc. L’éducation thérapeutique du patient est donc conçue pour former le patient aux compétences d’autogestion ou d’adaptation du traitement à sa maladie chronique particulière, et aux processus et compétences d’adaptation. Elle devrait également contribuer à réduire le coût des soins de longue durée pour les patients et la société. Elle est essentielle à l’autogestion efficace et à la qualité des soins de toutes les maladies ou affections de longue durée, bien que les patients gravement malades devraient également pouvoir en bénéficier.

Ainsi, « (…) L’ETP doit permettre aux malades d’acquérir et de maintenir des compétences qui leur permettent de gérer de manière optimale leur traitement afin d’arriver à un équilibre entre leur vie et leur maladie.

C’est donc un processus continu qui fait partie intégrante des soins. (…) »5.

C’est une approche soignante qui met la personne soignée ou un proche aidant au centre de la relation patient/prestataire de soins de santé, comme étant un partenaire de soins reconnu à part entière6-8. Elle part du principe que la personne soignée a des connaissances, des habilités et des expériences qu’il faut valoriser, encourager, stimuler et/ou rechercher. Quant au soignant, il reconnait et donne de la valeur aux savoirs du patient : ceci demande de sa part un changement de posture. Les prestataires de soins de santé ont souvent tendance à parler aux patients de leur maladie au lieu de les former aux processus de gestion quotidiens pour aider les patients à mieux gérer leur état5. Comme le décrit Gottlieb9,10, plus qu’un changement de posture c’est un changement de paradigme qui invite le soignant de se baser sur les forces de la personne soignée plutôt que d’essayer de pallier à ses manques.

L’ETP est un modèle d’éducation et d’accompagnement des personnes vivant avec une ou plusieurs maladies chroniques. Sa finalité est de soutenir l’engagement de la personne soignée dans ses soins grâce à un projet d’apprentissage qui fait sens pour lui, afin de diminuer le risque des complications11 et d’améliorer sa qualité de vie. Ses outils favorisent la construction d’une véritable collaboration entre personne soignée et soignant. Elle nécessite une approche globale, intégrée et interdisciplinaire12.

Que vise l’ETP ? Quelle posture pour les soignants ?

Les soignants qui pratiquent l’ETP ont pour objectif l’autonomie du patient pour leurs soins et l’amélioration de sa qualité de vie.

Cependant les objectifs des personnes soignées ne sont pas toujours tout à fait au même endroit, au même moment. L’irruption de la maladie et de la stomie qui en est souvent la conséquence ont un impact majeur dans la vie de celui-ci. La personne stomisée vit un processus émotionnel souvent intense qui parfois l’envahit totalement.

L’éducation thérapeutique vise à l’accompagner dans les étapes de ce processus afin qu’elle puisse faire une place raisonnable à sa maladie et à sa stomie dans sa vie quotidienne. Le but est qu’elle puisse acquérir des compétences pour gérer sa stomie, son traitement ainsi que des compétences psychosociales pour intégrer la stomie dans sa vie quotidienne.

Le défi des soignants est de concilier habilement ces deux types apprentissages dans le projet éducatif en s’accordant avec le patient sur ses difficultés éprouvées et ses besoins d’apprentissage. Une relation thérapeutique basée sur le partenariat est une condition indispensable à cette démarche éducative. Dans le cadre de cette alliance, l’accent est mis sur une relation d’équivalence morale entre personne soignée et soignant13.

Le premier temps éducatif est de favoriser et d’accueillir la parole de la personne en soins pour discerner et convenir avec elle de ses besoins particuliers pas toujours manifestes.

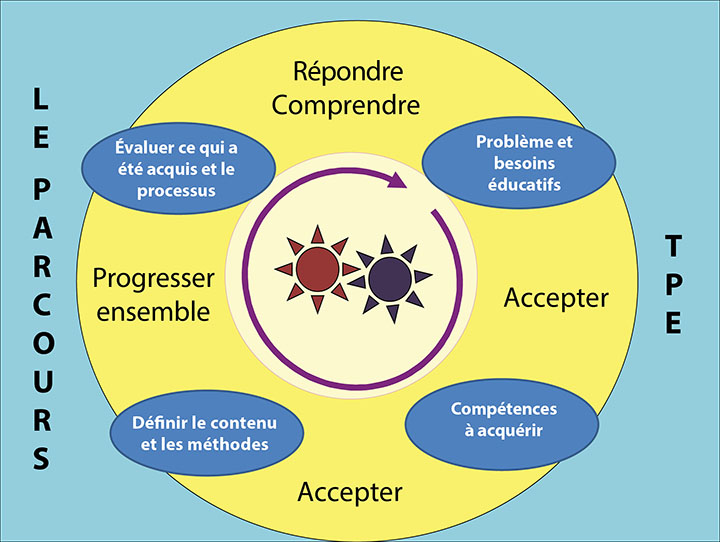

Figure 1. Le schema du parcours ETP

Dans le schéma de parcours ETP (le modèle ETP de Genève proposé), librement traduit de Lasserre Moutet et al.16 (Figure 1), le schéma décrit les concepts suivants :

- Les deux roues dentées au centre représentent le patient et le soignant, tous deux engagés, en mouvements actifs. Ils sont, l’un et l’autre, détenteurs d’un savoir spécifique propre. Le soignant est porteur de la connaissance scientifique et de son expérience clinique avec d’autres patients ; la personne malade est porteuse de son expérience singulière de la maladie et du traitement dans sa vie ainsi que de ses savoirs propres. Si cette rencontre est par nature asymétrique, elle n’est pour autant pas hiérarchisée au niveau des savoirs. Le soignant est un médiateur soutenant la personne dans son processus de transformation de ses connaissances pour mieux comprendre leur maladie, les conséquences du processus de la maladie et les interventions médicales correctives. Pour que cet engrenage fonctionne, le rythme est adapté. La première partie du parcours d’ETP est particulièrement importante pour soutenir cet engagement : patient et soignant s’accordent sur la problématique révélant la réalité des situations que la personne malade vit au quotidien. Pour le soignant cela implique de développer un authentique intérêt pour cette personne et son récit de vie avec la maladie.

- C’est sur la base de cette compréhension commune que des besoins éducatifs et compétences à acquérir par la personne soignée seront élucidés afin qu’elle puisse surmonter ses difficultés ou résoudre ses problèmes du quotidien.

- Une fois les objectifs co-définis avec le patient, les stratégies consisteront à amener le patient à se confronter à des idées nouvelles, à expérimenter un autre regard sur sa situation, à trouver des alternatives pour organiser autrement son quotidien.

- Finalement, le chemin parcouru et les changements réalisés seront évalués ensemble pour réajuster et pouvoir poursuivre la démarche.

Cette approche en 4 étapes peut se dérouler sur une ou plusieurs consultations.

Quelle éducation thérapeutique pour les personnes stomisées ?

La personne stomisée est confrontée à des changements corporels et souvent à une maladie chronique15,16 qui le contraignent à envisager une nouvelle réalité de vie. L’un des rôles principaux de l’infirmier-e stomathérapeute est d’aider cette personne à s’engager dans des apprentissages appropriés qui lui permettront peu à peu de s’adapter et de trouver un nouvel équilibre de vie17.

Qu’elle soit provisoire ou définitive, la stomie bouleverse et affecte la vie de la personne dans toutes ses dimensions : la vie sociale et professionnelle, la vie affective et familiale, l’identité de la personne et son estime de soi. Dans la situation où la stomie est provisoire, elle est souvent vécue comme un obstacle majeur dans la vie de la personne pendant cette période. Une fois le rétablissement de l’intestin effectué, certains redoutent de devoir nécessiter à nouveau la confection d’une stomie, ce qui effectivement peut arriver.

En visant l’autonomie de ces personnes dans la gestion de leurs soins ou celles de proches aidants lorsque cela n’est pas possible pour la personne stomisée, les infirmier-e-s stomathérapeutes intègrent l’ETP comme un processus continu de compréhension du vécu de la personne, de création d’un partenariat, d’apprentissage et d’informations du patient, tout au long des étapes du traitement (préopératoire, postopératoire, réadaptation, soins à domicile et suivi).

Ces apprentissages de la personne portent sur différentes thématiques en fonction de ses besoins : les aspects organisationnels liés à la stomie (soins, changement d’appareillage, équilibre du transit, hygiène alimentaire, etc), qui nécessitent la pratique d’auto-soins18. Des difficultés telles que l’altération de l’image de soi, de l’estime de soi tout comme d’autres implications psycho-émotionnelles19,20,21, la difficulté de parler de sa maladie et de sa stomie avec son entourage, la reprise de l’activité sexuelle, etc. demandent de développer des compétences psychosociales et d’adaptation. Le soignant met ainsi en œuvre des savoirs, savoirs faire et savoirs être pour trouver des stratégies pédagogiques adaptées aux stratégies d’apprentissage de la personne soignée/le proche aidant tout en respectant/intégrant les limites, les peurs, les résistances de cette personne en vue de l’amener par étapes à pouvoir réaliser à terme ses auto-soins et à s’adapter à sa réalité de vie avec la stomie et parfois sa maladie chronique.

Par quelles étapes passent la personne soignée et comment l’aider à les traverser ?

Selon Selder22, le vécu d’une maladie chronique s’apparente à un voyage à travers une réalité perturbée, semé d’incertitudes et conduisant finalement vers une restructuration de la réalité.

Afin de pouvoir mobiliser les ressources de la personne soignée en travaillant sur ses habiletés de résilience23,24, de consilience25 et d’empowerment26, les soignants se doivent d’aller rencontrer cette personne de ses représentations, ses valeurs et ses croyances27,28 en vue d’en tenir compte dans leur prise en soins. Ces dimensions, qui sont très en lien avec le contexte socio-culturel, religieux dans lequel s’inscrit la personne, sont aussi à prendre en compte en vue de les intégrer dans les soins prodigués29,30.

Selon Bandura31,32, le sentiment d’auto-efficacité des patients s’appuie sur quatre dimensions : la maitrise personnelle, l’apprentissage social, la persuasion par autrui et l’état physiologique et émotionnel. Il va générer trois types d’effets positifs chez un patient qui possède un bon niveau d’auto-efficacité : le premier quant aux choix des conduites à tenir, le second sur la persistance des comportements adoptés et le troisième sur sa plus grande résilience face aux imprévus et aux difficultés. L’infirmier-e qui pratique l’ETP va pouvoir mobiliser par ses interventions soignantes ces 4 dimensions en vue d’induire ces 3 types d’effets chez la personne soignée.

Selon Diclemente et al33, les changements d’habitudes de vie ne peuvent se faire que par étapes. En stomathérapie, ces approches auprès et avec la personne soignée débutent dès le préopératoire où des explications sont fournies au patient (et à la famille si possible) sur le besoin potentiel d’une stomie, la procédure chirurgicale et les soins postopératoires (WCET® recommandation 3.1.2, SOB+29) alors que la stomie n’est encore qu’envisagée. Ces recommandations sont reprises par l’association Américaine des Infirmier-e-s Stomathérapeutes, le WOCN®34.

Le schéma adapté et librement traduit de Martin et Savary35 décrit les principales étapes de l’enseignement décrit comme un besoin à nourrir, remplir. (Voir Figure 2). Selon l’âge de la personne soignées des connaissances, outils et démarches mobilisés dans l’enseignement aux adultes seront des compléments nécessaires à mobiliser pour pouvoir les atteindre36,37. D’autres stratégies devront être adaptées pour des populations plus jeunes, notamment vis-à-vis d’adolescents38,39.

Figure 2. Exigences pour l’ETP

Exemples de problèmes et objectifs emblématiques de l’éducation thérapeutique des patients stomisés

Ces problématiques et objectifs d’apprentissage peuvent s’appliquer pour des personnes soignées porteur de stomie d’élimination incontinente, situations les plus communément rencontrées. (Voir Tableau 1).

Tableau 1

Dans les cas de patients porteur d’autres types de stomie moins fréquentes, comme les patients porteurs de stomie d’élimination continente ou de stomie d’alimentation40,41, même si certains de ces items sont transversaux et/ou devront être adaptés à leur situation particulière, d’autres problématiques complémentaires, plus spécifiques, pourront s’appliquer. Il en sera de même pour les personnes souffrant de fistule-s à abouchement cutané42.

Dans les cas de patients porteur d’autres types de stomie moins fréquentes, comme les patients porteurs de stomie d’élimination continente ou de stomie d’alimentation40,41, même si certains de ces items sont transversaux et/ou devront être adaptés à leur situation particulière, d’autres problématiques complémentaires, plus spécifiques, pourront s’appliquer. Il en sera de même pour les personnes souffrant de fistule-s à abouchement cutané42.

Dans un certain nombre de situations, que ce soit par dégout, refus, déni et/ou incapacité-s (motrices, cérébrales, psycho-émotionnelles ou psychiatrique), la personne stomisée ne sera pas en mesure d’entrer dans tout ou partie de ce processus d’apprentissage et d’autonomisation43,44. Et cela que ce soit à court, moyen et parfois à long terme. Dans ces situations, le relais à un proche aidant, qui pourrait-être un soignant ou un proche, devra s’imaginer et se mettre sur pied. Les démarches éducatives nécessaires à leur autonomisation devront être réalisées de façon relativement similaire dans la perspective de pouvoir permettre autant que possible à la personne stomisée de retourner à domicile. A celles-ci vont s’ajouter la gestion de l’accompagnement des changements potentiels de rapports interpersonnels et éventuellement intimes entre les protagonistes ; changements que ce type de soins pourra générer et qui seront à prendre à considération avec une approche systémique et globale de la situation.

Ces démarches seront encore complexifiées dans le cadre des personnes vivant seules à domicile, d’autre plus si elles sont âgées, puisque pouvant remettre en question leur maintien/retour à domicile. La nécessité des relais, réseaux à mettre sur pied dans ce type de situation fait ainsi écho aux contenus du rapport de l’agence américaine des personnes retraitées (AARP) réalisé en 201245,46.

Enfin, la personne stomisée va parfois se retrouver porteuse de plus d’une seule stomie, celles-ci pouvant toutes être définitives. (Voir figures 3 et 4). De notre expérience ces situations complexes sont plus fréquentes qu’avant et sont le plus souvent liées à une étiologie cancéreuse.

Figure 3. Exemple d’une personne porteuse d’une colostomie Gauche définitive et d’une urétérostomie cutanée trans-iléale (intervention dite de Bricker) avec un syndrome d’urines violettes47.

Figure 4. Exemple d’un patient à quelques jours post-opératoires, avec colostomie de repos et iléostomie de décharge. Le rétablissement de continuité digestive se fera 9 mois plus tard en deux temps, la stomie d’aval avant la stomie d’amont, à quelques semaines d’intervalle.

Eclairages et compléments en lien avec les patients souffrant de plaies chroniques

Contrairement à certaines idées reçues, la stomathérapie ne s’intéresse pas qu’aux soins aux personnes stomisées, même si l’usage du terme originel d’Entérostoma-Thérapeute (ET)48 peut prêter à confusion. En effet, la formation complète de stomathérapeute (ETNEP)49 comprend les soins aux personnes souffrants des plaies, aux personnes souffrant de troubles de la continence, de fistules à abouchement cutané et, dans certaines écoles, de soins aux personnes massectomisées.

Cela dit, la spécialisation Plaies est devenue une spécialisation à part entière et certain-e-s d’entre nous collaborent avec ces spécialistes. Il est important de relever que dans le curriculum Européen d’infirmier-e-s spécialisée en soins de plaies ces dimensions d’éducation au patient sont spécifiées (Units 3 & 4)50,51,52.

Le bénéfice d’utiliser une approche d’enseignement multimédia réside en la combinaison des méthodes pour transmettre l’information. Elle apporterait une aide pour résoudre des problèmes rencontrés par le patient mais aussi renforcerait l’information prodiguée55,56.

Quelles revues systématiques Cochrane ont été réalisées à propos de patients porteurs d’ulcère veineux, de plaies sur pied diabétique, de lésions de pression. Elles relèvent le fait que :

- Au sujet des patients porteurs d’ulcère de jambes, il y n’aurait pas assez de recherches disponibles visant à évaluer les stratégies d’accompagnement des patients qui pourraient augmenter leur adhérence/compliance. Et ce alors que la compliance à la compression est reconnue comme étant un facteur important à la prévention des récidives57.

- Concernant la personne diabétique, il n’y aurait pas assez d’évidence pour dire que l’enseignement, sans autre mesures préventives, serait suffisant pour réduire la survenue de lésions au niveau de leurs pieds et des amputations58.

- Enfin concernant les lésions de pression, les auteurs soulèvent que ce concept d’implication de la personne soignée reste vague et comprend un nombre important de facteurs qui sont variés et comprennent une large palette d’interventions et d’activités possibles. Dans le même temps, ils précisent que cette l’implication dans les soins comme le respect des droits du patient sont des valeurs importantes qui interviendraient dans le processus de leur santé. Cette implication aurait pour bénéfice d’augmenter leur motivation et leurs connaissances en lien avec leur santé. Cette implication induirait une augmentation de leur capacité à gérer la maladie et de s’occuper d’eux-mêmes, augmentant ainsi leur sentiment de sécurité et permettant d’obtenir de meilleurs résultats quant à l’amélioration de leur santé59.

Concernant les patients atteints de plaies cancéreuses, les recommandations européennes relèvent l’existence d’échelles d’évaluation des symptômes liées à cette typologie de plaies permettant le dépistage précoce de leurs complications associées, la réduction des coûts liées aux soins et au matériel utilisés pour les soins, tout en impliquant ces personnes soignées. En effet, certains de ces outils pourront leur être proposés et ils pourront les utiliser60. Afin que cela puisse se concrétiser, un enseignement à leur utilisation s’avèrera nécessaire et ce alors que ces personnes peuvent perdre confiance en eux, en leurs traitements et aux équipes soignantes alors que la maladie progresse ; leur/s plaie/s en étant le stigmate visible.

Conclusion

L’éducation thérapeutique est la pierre angulaire des interventions réalisées auprès des personnes atteintes de maladie chronique, ou en situation de chronicité, dans la perspective de promotion, de prévention et d’éducation à leur santé. Elle est une activité fondamentale transversale aux champs de spécialisation de la stomathérapie. Chaque situation étant unique, elle permet au soignant de développer des compétences dans ce domaine en vue d’améliorer les soins qu’il/elle prodigue. Elle nous invite à l’innovation, à la créativité, à l’adaptation, à penser en dehors du cadre afin de rechercher d’autres stratégies interventionnelles et faire preuve d’humilité ; pouvant nous conduire à demander de l’aide via notre réseau interprofessionnel et/ou international.

Selon Adams61, l’ETP resterait un domaine d’interventions vaste où les visions sont encore discutées quant à l’utilité des interventions éducatives pour améliorer les impacts qu’elles auraient sur la santé. Les résultats des études seraient encore limités pour supporter leur évidence. Pour d’autres auteurs, son efficacité serait aujourd’hui prouvée par les recherches. Elle serait pour beaucoup de centres hospitaliers un moyen de faire des économies, car permettant de réduire les durées de séjours hospitalier et le nombre de complications62-66.

Enfin, si cette démarche éducative débute à l’hôpital, elle se poursuit tant dans les suivis ambulatoires qu’à domicile. Dans ce sens, les relais à mettre sur pied et à entretenir sont primordiaux pour garantir la poursuite dans la continuité, la cohérence et la coordination des démarches entreprises comme celles des étapes futures à co-construire. L’implication des proches aidants dans ces démarches, pour autant que la personne soignée et les proches concernés soient d’accord, est importante. Ils sont des ressources à ne pas négliger bien que leurs interventions vont générer d’autres enjeux à tenir en compte.

La formation des professionnels soignants, souvent infirmier-e, à ce type de démarche va renforcer leur expertise et efficience67, sachant que chaque situation les mettra au défi de trouver de nouvelles stratégies et habilités pour y parvenir.

Déclaration de Conflit d’intérêt

Les auteurs déclarent ne pas avoir de conflit d’intérêt.

La partie plaies a été en partie construite sur la base de notes prises lors d’une session University Conference Model (UCM)68 sur cette thématique. Cette session a eu lieu lors du congrès European Wound Management Association (EWMA) à Amsterdam en 2017, présentations réalisées par Mesdames Julie Jordan O’Brien, Clinical Nurse Specialist Tissue Viability ; et Véronique Urbaniak, Advanced Practice Nurse69.

Financement

Les auteurs n’ont reçu aucun financement pour cette étude.

Author(s)

Laurence Lataillade

Clinical Specialist Nurse and Stomatherapist, Geneva University Hospitals

Laurent Chabal*

Stomal Therapy Nurse and Lecturer, Geneva School of Health Sciences, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland. Haute École de Santé Genève, HES-SO Haute École Spécialisée de Suisse Occidentale, Vice-President of WCET® 2018–2020

* Corresponding author

References

- Miller LV, Goldstein J. More efficient care of diabetic patients in a county-hospital setting. N Engl J Med 1972;286:1388–1391.

- Lacroix A, Assal JP. Therapeutic education of patients – new approaches to chronic illness, 2nd ed. Paris: Maloine; 2003.

- Rogers C. Client-centered therapy, its current practice, implications and theory. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1951.

- Kübler-Ross E. On death and dying. London: Routledge; 1969.

- World Health Organization. Therapeutic patient education, continuing education programmes for health care providers. Report of a World Health Organization Working Group; 1998. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/145294/E63674.pdf

- Stewart M, Belle Brown J, Wayne Weston W, MacWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient-centered medicine: transforming the clinical method. Oxon: Radcliffe; 2003.

- Kronenfeld JJ. Access to care and factors that impact access, patients as partners in care and changing roles of health providers. Research in the sociology of health care. Bingley: Emerald Book; 2011.

- Dumez V, Pomey MP, Flora L, De Grande C. The patient-as-partner approach in health care. Academic Med: J Assoc Am Med Coll 2015;90(4):437–1.

- Gottlieb LN, Gottlieb B, Shamian J. Principles of strengths-based nursing leadership for strengths-based nursing care: a new paradigm for nursing and healthcare for the 21st century. Nursing Leadership 2012;25(2):38–50.

- Gottlieb LN. Strengths-based nursing care: health and healing for persons and family. New York: Springer; 2013.

- Orem DE. Nursing: concepts of practice. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book Inc; 1991.

- The Official Website of the Disabled Persons Protection Commission; 2018. Available from: http://www.mass.gov/dppc/abuse-prevention/types-of-prevention.html

- Finset A, editor. Patient education and counselling journal. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2019. Available from: https://www.journals.elsevier.com/patient-education-and-counseling/

- Roy, C. The Roy adaptation model. New Jersey: Pearson; 2009.

- Price P. How we can improve adherence? Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2016;32(S1):201–5.

- Lasserre Moutet A, Chambouleyron M, Barthassat V, Lataillade L, Lagger G, Golay A. Éducation thérapeutique séquentielle en MG. La Revue du Praticien Médecine Générale 2011;25(869):2–4.

- Ercolano E, Grand M, McCorkle R, Tallman NJ, Cobb MD, Wendel C, Krouse R. Applying the chronic care model to support ostomy self-management: implications for nursing practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2016;20(3):269–74.

- World Health Organization. Non-communicable diseases; 2020. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/noncommunicable_diseases/en/

- Price B. Explorations in body image care: Peplau and practice knowledge. J Psychiatric Mental Health Nurs 1998;5(3):179–186.

- Segal N. Consensuality: Didier Anzieu, gender and the sense of touch. New York: Rodopi BV; 2009.

- Anzieu D. The skin-ego. A new translation by Naomi Segal (The history of psychoanalysis series). Oxford: Routledge; 2016.

- Selder F. Life transition theory: the resolution of uncertainty. Nurs Health Care 1989;10(8):437–40, 9–51.

- Cyrulnik B, Seron C. Resilience: how your inner strength can set you free from the past. New York: TarcherPerigee; 2011.

- Scardillo J, Dunn KS, Piscotty R Jr. Exploring the relationship between resilience and ostomy adjustment in adults with permanent ostomy. J WOCN 2016;43(3): 274–279.

- Wilson EO. Consilience: the unity of knowledge. New York: Knopf; 1998.

- Zimmerman MA. Empowerment theory, psychological, organizational and community levels of analysis. In Rappaport J, Seidman E, editors. Handbook of community psychology. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2000. p. 43–63.

- Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Behav 1988;15(2):175–183.

- Knowles SR, Tribbick D, Connel WR, Castle D, Salzberg M, Kamm MA. Exploration of health status, illness perceptions, coping strategies, psychological morbidity, and quality of life in individuals with fecal ostomies. J WOCN 2017;44(1):69–73.

- Zulkowski K, Ayello EA, Stelton S, editors. WCET international ostomy guideline. Perth: Cambridge Publishing, WCET; 2014.

- Purnell L. The Purnell Model applied to ostomy and wound care. JWCET 2014;34(3):11–18.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol Rev 1977;84(2):191–215.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Psychological review. San Francisco: Freeman WH; 1997.

- Diclemente CC, Prochaska JO. Toward a comprehensive, transtheoretical model of change: stages of change and addictive behaviours. In Miller WR, Heather N, editors. Treating addictive behaviours. processes of change. New York: Springer; 1998. p. 3–24.

- Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society – Guideline Development Task Force. WOCN® Society clinical guideline management of the adult patient with a fecal or urinary ostomy – an executive summary. J WOCN 2018;45(1):50–58.

- Martin JP, Savary E. Formateur d’adultes: se professionnaliser, exercer au quotidien. 6th ed. Lyon: Chronique Sociale; 2013.

- Lataillade L, Chabal L. Therapeutic patient education (TPE) in wound and stoma care: a rich challenge. ECET Bologna, Italy [Oral presentation]; 2011.

- Merriam SB, Bierema LL. Adult learning: linking theory and practice. Indianapolis: Jossey-Bass; 2013.

- Mohr LD, Hamilton RJ. Adolescent perspectives following ostomy surgery, J WOCN 2016;43(5): 494–498.

- Williams J. Coping: teenagers undergoing stoma formation. BJN 2017;26(17):S6–S11.

- Stroud M, Duncan H, Nightingale J. Guidelines for enteral feeding in adult hospital patients. Gut 2003;52(7):vii1–vii12.

- Roveron G, Antonini M, Barbierato M, Calandrino V, Canese G, Chiurazzi LF, Coniglio G, Gentini G, Marchetti M, Minucci A, Nembrini L, Nari V, Trovato P, Ferrara F. Clinical practice guidelines for the nursing management of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and jejunostomy (PEG/PEJ) in adult patients. An executive summary. JWCON 2018;45(4):32–334

- Brown J, Hoeflok J, Martins L, McNaughton V, Nielsen EM, Thompson G, Westendrop C. Best practice recommendations for management of enterocutaneous fistulae (ECF). The Canadian Association for Enterostomal Therapy; 2009. Available from: https://nswoc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/caet-ecf-best-practices.pdf

- Jukes M. Learning disabilities: there must be a change in attitude. BJN 2004;13(22):1322.

- Wendorf JH. The state of learning disabilities: 507 facts, trends and emerging issues. 3rd ed. New York: National Center for Learning Disabilities, Inc; 2014.

- Reinhard SC, Levine C, Samis S. Home alone: family caregivers providing complex chronic care. AARP Public Policy Institute; 2012.

- Reinhard SC, Ryan E. From home alone to the CARE act: collaboration for family caregivers. AARP Public Policy Institute, Spotlight 28; 2017.

- Peters P, Merlo J, Beech N, Giles C, Boon B, Parker B, Dancer C, Munckhof W, Teng H.S. The purple urine bag syndrome: a visually striking side effect of a highly alkaline urinary tract infection. Can Urol Assoc J 2011;5(4):233–234.

- Erwin-Toth P, Krasner DL. Enterostomal therapy nursing. Growth & evolution of a nursing specialty worldwide. A Festschrift for Norma N. Gill-Thompson, ET. 2nd ed. Perth: Cambridge Publishing; 2012.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®, Education Committee; 2020. Available from: http://www.wcetn.org/the-wcet-education

- Pokorná A, Holloway S, Strohal R, Verheyen-Cronau I. Wound curriculum for nurses: post-registration qualification wound management – European qualification framework level 5. J Wound Care 2017;26(2):S9–12, S22–23.

- Prosbt S, Holloway S, Rowan S, Pokorná A. Wound curriculum for nurses: post-registration qualification wound management – European qualification framework level 6. J Wound Care 2019;28(2):S10–13, S27.

- European Wound Management Association. EQF level 7 curriculum for nurses; 2020. Available from: https://ewma.org/it/what-we-do/education/ewma-wound-curricula/eqf-level-7-curriculum-for-nurses-11060/

- Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Peel J, Baker DW. Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Educ Couns 2003;51(3):267–275.

- Van Hecke A, Beeckman D, Grypdonck M, Meuleneire F, Hermie L, Verheaghe S. Knowledge deficits and information-seeking behaviour in leg ulcer patients, an exploratory qualitative study. J WOCN 2013;40(4):381–387.

- Ciciriello S. Johnston RV, Osborne RH, Wicks I, Dekroo T, Clerehan R, O’Neill C, Buchbinder R. Multimedia education interventions for customers about prescribed and over-the-counter medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2013. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008416/full

- Moore Z, Bell T, Carville K, Fife C, Kapp S, Kusterer K, Moffatt C, Santamaria N, Searle R. International best practice statement: optimising patient involvement in wound management. London: Wounds International; 2016.

- Weller CD, Buchbinder R, Johnston RV. Intervention for helping people adhere to compression treatments for venous leg ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2013. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008378.pub2/abstract

- Dorrestelijn JA, Kriegsman DMW, Assendelft WJJ, Valk GD. Patient education for preventing diabetic foot ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2014. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001488.pub5/abstract

- O’Connor T, Moore ZEH, Dumville JC, Patton D. Patient and lay carer education fort preventing pressure ulceration in at-risk populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2015. Available from: http://www.cochrane.org/CD012006/WOUNDS_patient-and-lay-carer-education-preventing-pressure-ulceration-risk-populations

- Probst S, Grocott P, Graham T, Gethin G. EONS recommendations for the care of patients with malignant fungating wounds. London: European Oncology Nursing Society; 2015.

- Adams R. Improving health outcomes with better patient understanding and education. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2010;3:61–72.

- Lagger G, Pataky Z, Golay A. Efficacy of therapeutic patient education in chronic diseases and obesity. Patient Educ Couns 2010;79(3):283–286.

- Kindig D, Mullaly J. Comparative effectiveness – of what? Evaluating strategies to improve population health. JAMA 2010;304(8):901–902.

- Friedman AJ, Cosby R, Boyko S, Hatt on-Bauer J, Turnbull G. Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: a systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. J Canc Educ 2011;26(1):12–21.

- Jensen BT, Kiesbye B, Soendergaard I, Jensen JB, Ammitzboell Kristensen S. Efficacy of preoperative uro-stoma education on self-efficacy after radical cystectomy; secondary outcome of a prospective randomised controlled trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2017;28:41–46.

- Rojanasarot S. The impact of early involvement in a post-discharge support program for ostomy surgery patients on preventable healthcare utilization. J WOCN 2018;45(1):43–49.

- Knebel E, editor. Health professions education: a bridge to quality (quality chasm). Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

- European Wound Management Association; 2020. Available from: http://ewma.org/what-we-do/education/ewma-ucm/

- European Wound Management Association Conference; 2017. Available from: http://ewma.org/ewma-conference/2017-519/