Volume 41 Number 2

Practice Implications from the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline 2020

Laurent O. Chabal, Jennifer L. Prentice and Elizabeth A. Ayello

Keywords ostomy, education, stoma, culture, guideline, International Ostomy Guideline, IOG, ostomy care, peristomal skin complication, religion, stoma site, teaching

For referencing Chabal LO et al. Practice Implications from the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline 2020. WCET® Journal 2021;41(2):10-21

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.2.10-21

Abstract

The second edition of the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline (IOG) was launched in December 2020 as an update to the original guideline published in 2014. The purpose of this article is to introduce the 15 recommendations covering four key arenas (education, holistic aspects, and pre- and postoperative care) and summarise key concepts for clinicians to customise for translation into their practice. The article also includes information about the impact of the novel coronavirus 2019 on ostomy care.

Acknowledgments

The WCET® would like to thank all of the peer reviewers and organizations that provided comments and contributions to the International Ostomy Guideline 2020. Although the WCET® gratefully acknowledges the educational grant received from Hollister to support the IOG 2020 development, the guideline is the sole independent work of the WCET® and was not influenced in any way by the company who provided the unrestricted educational grant.

The authors, faculty, staff, and planners, including spouses/partners (if any), in any position to control the content of this CME/NCPD activity have disclosed that they have no financial relationships with, or financial interests in, any commercial companies relevant to this educational activity.

To earn CME credit, you must read the CME article and complete the quiz online, answering at least 7 of the 10 questions correctly. This continuing educational activity will expire for physicians on May 31, 2023, and for nurses June 3, 2023. All tests are now online only; take the test at http://cme.lww.com for physicians and www.NursingCenter.com/CE/ASWC for nurses. Complete NCPD/CME information is on the last page of this article.

© Advances in Skin & Wound Care and the World Council of Enterostomal Therapists.

Introduction

Guidelines are living, dynamic documents that need review and updating, typically every 5 years to keep up with new evidence. Therefore, in December 2020, the World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® (WCET®) published the second edition of its International Ostomy Guideline (IOG).1 The IOG 2020 builds on the initial IOG guideline published in 2014.2 Hundreds of references provided the basis for the literature search of articles published from May 2013 to December 2019. The guideline uses several internationally recognised terms to indicate providers who have specialised knowledge in ostomy care, including ET/stoma/ostomy nurses and clinicians.1 However, for the purposes of this article, the authors will use “ostomy clinicians” and “person with an ostomy” to be consistent.

Guideline development

A detailed description of the IOG 2020 guideline methodology can be found elsewhere.1 Briefly, the process included a search of the literature published in English from May 2013 to December 2019 by the authors of this article, who comprise the Guideline Development Panel. More than 340 articles were reviewed. For each article identified, a member of the panel would write a summary, and all three would then confirm or revise the ranking of the article evidence. The evidence was categorised and defined and compiled into a table that is included in the guideline and can be accessed on the WCET® website. The strength of recommendations were rated using an alphabetical system (A+, A, A−, etc). Feedback was sought from the global ostomy community, and 146 individuals and 45 organizations were invited to comment on the findings. Of these, 104 individuals and 22 organizations returned comments, which were used to finalise the guideline.

Guideline overview

Because the WCET® is an international association with members in more than 65 countries, there is a strong emphasis on diversity of culture, religion, and resource levels so that the IOG 2020 can be applied in both resource-abundant and resource-challenged countries. The forward was written by Dr Larry Purnell, author of the Purnell Model for Cultural Competence (unconsciously incompetent, consciously incompetent, consciously competent, unconsciously competent).3-5 As with the 2014 guideline, the WCET® members and International Delegates were invited to submit culture reports from their country, and 22 were received and incorporated into the guideline development.

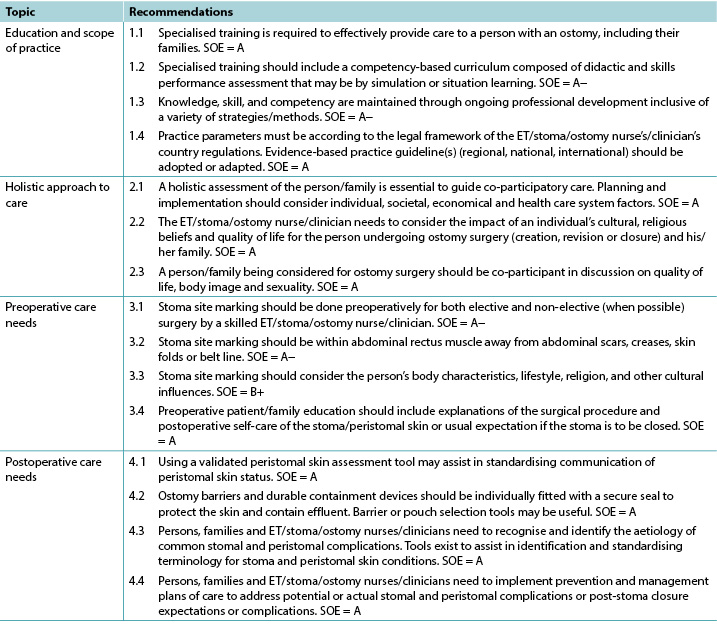

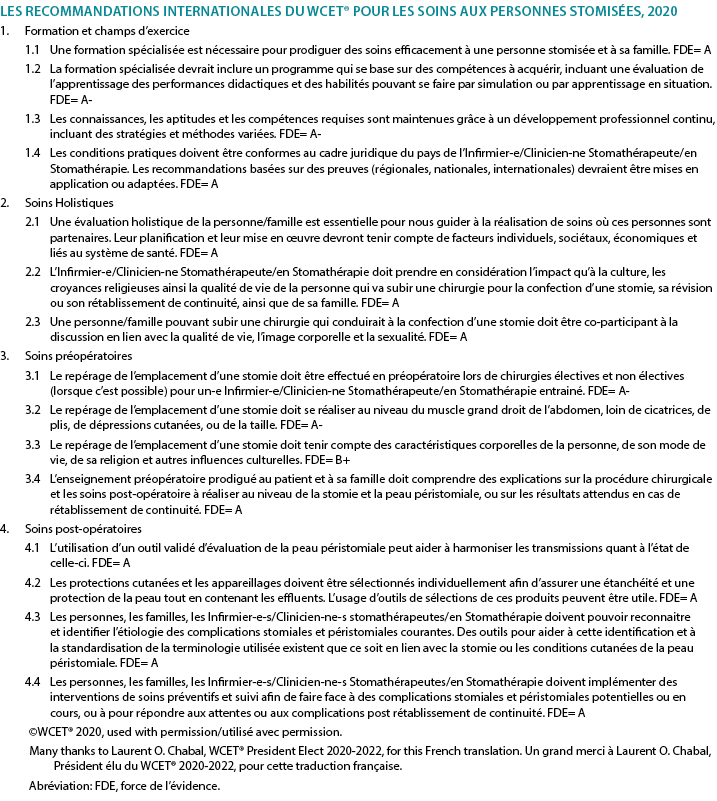

Because the IOG 2020 is intended to serve as a guide for clinicians in delivering care for persons with an ostomy, new to this edition is a section on guideline implementation. Also new is a recommendation for nursing education. A glossary of terms and helpful educational resources are also included in the various appendices. The 15 IOG 2020 recommendations are listed in Table 1. The recommendations have been translated into Chinese (Supplemental Table 1), French (Supplemental Table 2), Portuguese (Supplemental Table 3), and Spanish (Supplemental Table 4) and are also available on the WCET® website (www.wcetn.org).

Table 1 WCET® International OStomy Guideline 2020 Recommendations

©WCET® 2020, used with permission.

Abbreviations: ET, enterostomal therapy; SOE, strength of evidence.

Education

The evidence supports four IOG 2020 recommendations about education (Table 1). A person who has surgery resulting in the creation of an ostomy needs knowledge regarding their type of stoma, care strategies such as ostomy pouches, and the impact the ostomy will have on their lifestyle.6 Accordingly, the needs of these patients go beyond what may be taught in initial nursing education programs. Zimnicki and Pieper7 surveyed nursing students and found that just under half (47.8%) did not have experience in caring for a patient with an ostomy. For those who did, they felt most confident in pouch emptying.7 Findings by Cross and colleagues8 also support that staff nurses without specialised ostomy education felt more confident in emptying the ostomy pouch as opposed to other ostomy care skills. Duruk and Uçar9 in Turkey and Li and colleagues10 in China also reveal that staff nurses lack adequate knowledge about the care of patients with ostomies. Better ostomy care outcomes have been reported when patients are cared for by nurses who have had specialised ostomy education. This includes research in Spain by Coca and colleagues,11 Japan by Chikubu and Oike,12 and the UK by Jones.13

For over 40 years, the WCET® has promoted the importance of specialised ostomy education for nurses to better meet the needs of patients and their families.6 Other societies such as the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing Society in the US; Nurses Specialised in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada; and the Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK have also advocated for specialised nursing education. The suggested modifications include competence-based curricula and checklists of skills and professional performance necessary for the specialised nurse to provide appropriate care to patients with an ostomy and their families.14-17 Evidence-based practice requires that healthcare professionals keep abreast of new techniques, skills, and knowledge; lifelong learning is necessary.

Holistic aspects of care: culture and religion

The literature supports three highly ranked recommendations related to holistic care within the IOG 2020 (Table 1) and confirms the necessity of taking them into account when caring for individuals with an ostomy.

Ostomies can impact individuals in different domains such as day-to-day life, overall quality of life, social relationships, work, intimacy, and self-esteem. A holistic approach to care aims to acknowledge and address the patient’s need at a physiological, psychological, sociological, spiritual, and cultural level,18 especially when the patient’s situation is complex.19 Therefore, implementing a holistic approach to practice is crucial to address all of the potential issues.20

Many tools exist to assess patients’ quality of life, self-care adjustment, social adaptation, and/or psychological status.21,22 They provide important information to nurses in their clinical decisions making, although as always clinical judgment remains relevant. Because holistic care is multidimensional, using various methods will allow an integrative and global approach to caring for patients with ostomies.

The World Health Organization’s definition of health23 is still relevant today. An individual’s origins, beliefs, religion, culture, gender, and age will influence his/her interpretation of illness and diseases.24-26 For healthcare professionals, the need to understand these influences and their real impacts on the patient, family, and/or caregiver(s) is essential because it will provide key information to co-construct ostomy care.

Dr Larry Purnell’s Model for Cultural Competence3,4 can be readily applied to ostomy care.5 It can help nurses to deliver culturally competent care to patients with an ostomy. Integrating effective cultural competence will improve relationships among patients, families, and healthcare professionals,27 especially if patients and/or families are finding it difficult to cope.28

Specialised and nonspecialised nurses have a key role in patient, family, and caregiver education.29 They will, step by step, help support the development of specific skills and implementation of personalised adaptive strategies. Nurses’ advice and support can decrease ostomy-related complications,13,30,31 and listening to and addressing patient emotions will improve individuals’ self-care.32

Taking into account the International Charter of Ostomate Rights33 during provision of ostomy care will increase patients’ quality of life, because it supports patient empowerment and reinforces the partnerships among patients, families, caregivers, and healthcare professionals.

Section 6 of the IOG 2020 provides an international perspective on ostomy care. With contributions from 22 countries, this version is more inclusive than the previous one.2 It is the authors’ hope that it will help ostomy clinicians around the world when taking care of patients from another culture, background, or belief system and therefore give them better skills to address each individual’s needs.

Preoperative Care And Stoma Site Marking

As seen in Table 1, there are four recommendations that address preoperative care and stoma site marking. The literature emphasises preoperative education for patients who are about to undergo ostomy surgery, which includes preoperative site marking. Fewer complications are seen in persons who have their stoma sites marked before surgery.34,35

Because specialised nurses may not be available 24/7, patients who undergo unplanned/emergency surgery may not benefit from preoperative education and stoma site marking. Accordingly, the literature supports the training of physicians and nonspecialty nurses to do stoma site marking.34-37 Zimnicki36 completed a quality improvement project to train nonspecialised nurses in stoma site marking. This project significantly increased the number of patients who had preoperative stoma site marking and education.36

Stoma site marking is an important art and skill that is beyond the scope of this article to describe in detail. Major principles include observation of the patient’s abdomen while standing, sitting, bending over, and lying down (Figure 1).37-41 There are at least two techniques for identifying the ideal abdominal location.42-52 Those interested might consult the references42-60 as well as the WCET® webinar or pocket guide on stoma site marking (www.wcetn.org).52

Assess the abdomen in multiple positions when doing stoma siting

Figure 1 positions for stoma site marking ©2021 Ayello, used with permission.

Postoperative Care

The IOG 2020 lists four recommendations for postoperative care to assist ostomy clinicians to detect, prevent, or manage and thereby minimise the effect of any peristomal complications (Table 1).

Successful postoperative recovery following ostomy surgery is dependent on multiple factors from the perspective of both the ostomy clinician and person with an ostomy. All members of the care team, including the patient, must have a heightened awareness of preventive or remedial strategies for common problems that may occur with the formation of a new stoma, refashioning of an existing stoma, or stoma closure. The ability to recognise and effectively manage potential or actual postoperative ostomy and peristomal skin complications (PSCs) has inherent short- and long-term ramifications for the health, well-being, and independence of the persons with an ostomy61-63 and for health resource management.64-66

Postoperative ostomy complications may manifest as early or late presentations. Early complications such as mucocutaneous separation, retraction, stomal necrosis, parastomal abscess, or dermatitis may occur within 30 days of surgery. Later complications include parastomal hernias (PHs) and stomal prolapse, retraction, or stenosis.63,67,68

However, the most common postoperative complications are PSCs.69 Frequently cited causes of PSCs are leakage,70,71 no preoperative stoma siting,35 poor surgical construction techniques,72 ill-fitting appliances, and long wear time of appliances.71,73

Common PSCs include acute and chronic irritant contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis, the former arising from prolonged contact with feces or urine on the skin eventually causing erosion (Figure 2). Assessment of the abdomen, stoma, stoma appliance, and accessories in use as well as the patient’s ability to care for the stoma and correctly reapply his/her appliance is essential to determine the cause of leaks. Skin care, depending on the severity of irritation or denudation, may involve the use protective pectin-based powders or pastes, skin sealants (acrylate copolymer or cyanoacrylates wipes or sprays), and protective skin barriers. Adjustments to the type of appliance used and wear time may also be required ameliorate acute and prevent chronic irritant contact dermatitis.61,70,74

Figure 2 irritant dermatitis ©2021 Chabal, used with permission.

Allergic contact dermatitis results from an adverse reaction to substances within products applied to the skin during cleansing or skin protection used prior to appliance application or removal or that are part of the appliance itself.74,75 Compromised skin usually reflects the shape of the appliance if it is the allergen or the area where secondary skin care products have been used. Affected skin may have the appearance of a rash; be reddened, blistered, itchy, or painful; or exude hemoserous fluid (Figure 3). Patch testing small areas of skin well away from compromised skin and the stoma may be required to identify specific causative agents and/or assess the suitability of other skin barrier products used to gain a secure seal around the stoma.70,75

Figure 3 allergic contact dermatitis ©2021 Chabal, used with permission.

Parastomal hernias are a latent complication that also contributes to PSCs. Causes include surgical technique, the size and type of stoma, abdominal girth, and age and medical conditions such as prior hernias and diverticulitis fluid. Education of surgeons and prophylactic insertion of polypropylene mesh during surgery as well as postoperative patient education may decrease PH incidence (Figure 4).68,76,77 Further, providers must assess and measure the patient’s abdomen at the level of the stoma to choose the most appropriate support garment required to manage the degree of PH protrusion, prevent further exacerbation, and allow the stoma to continue to function normally.78 The ostomy appliance/pouch in use will also need to be frequently reassessed to address any changes in the size of the stoma.

Figure 4 parastomal hernia ©2021 Chabal, used with permission.

The IOG 2020 cites numerous tools that ostomy clinicians can use to effectively identify and classify PSCs79,80,81 and select appropriate skin barriers and appliances to manage PSCs.62,82

Finally, of increasing importance to improve the postoperative quality of life of individuals with an ostomy, reduce ostomy complications and associated readmissions, and enhance interprofessional practice are the use of early or enhanced recovery programs after surgery,83,84 ongoing education and discharge monitoring programs,68,85 and telehealth modalities for counseling and remote consultation.86,87

Guideline implementation

For clinical guidelines to result in positive outcomes for the intended patient populations, the proposed recommendations need to be adopted into daily practice. Multiple strategies are required to facilitate adoption,88,89 and guidelines should be reviewed and adapted for specific clinical contexts.90 Prior thought, therefore, is required regarding how guidelines will be disseminated and implemented. Potential barriers to guideline implementation may include a lack of resources, competing health agendas, or a perceived lack of interest in ostomy care as a medical/nursing subspecialty with no “champion” to advocate for and facilitate implementation. Last, guidelines may be seen as too prescriptive. The section on guideline implementation within the IOG 2020 provides advice, and readers are directed to the full guideline for more information.

Impact of Covid-19 on ostomy care

The review of the evidence for the IOG 2020 preceded the advent the novel coronavirus 2019. During the pandemic, there have been anecdotal reports of ostomy clinicians being reassigned to care for other patients. The extent and impact of this have yet to be researched. In the meantime, virtual visits may provide a safe alternative to in-person care for patients and providers.91 A study by White and colleagues92 reported on the feasibility of virtual visits for persons with new ostomies; 90% of patients felt that these visits were helpful in managing their ostomy.92 However, another study found that only 32% of the respondents knew that telehealth was an option.93 Further, 71% “did not think [their issue] was serious enough to seek assistance from a healthcare professional,”93 although 57% reported some peristomal skin occurrence during the pandemic.93 In descending order, the types of skin issues reported were redness or rash (79%), itching (38%), open skin (21%), bleeding (19%), and other concerns (7%).93

Conclusions

The IOG 2020 aims to provide clinicians with an evidence framework upon which to base their practice. The 15 IOG 2020 recommendations are applicable in countries where resources are abundant (nurses and healthcare professionals trained in ostomy care with manufactured appliances/pouches), as well as in countries with limited resources (nonspecialised nurses, healthcare professionals, and laypersons who create ostomy equipment from available local resources to contain the ostomy effluent). Specialised knowledge is needed to assist persons with an ostomy in learning how to apply, empty, and change their appliance/pouch, but living with an ostomy is more than that. All aspects of the patient need to be considered.

Holistic patient care should be individualised and address diet, activities of daily living, sexual life, prayer, work, medications, body image, and other patient-centered concerns. Preoperative stoma siting has been linked to better postoperative outcomes. Early identification and intervention for PSCs requires adequate teaching, as well as awareness of when to seek professional help. Nurses who have specialised knowledge in ostomy care can improve quality of life for persons with an ostomy, including those who experience PSCs.95 It is the authors’ hope that the IOG 2020 will enhance care outcomes and rehabilitation for this population.

Practice pearls

- Patients who are cared for by healthcare professionals with specialised ostomy knowledge experience better care outcomes.

- There are clinical tools to assist with peristomal skin assessment and appliance requirements.

- Pre- and postoperative patient and family education needs to be holistic and individualised.

- Patients who undergo presurgical stoma siting experience fewer complications.

- The most common PSC is leakage leading to irritant dermatitis.

- Telehealth and remote consultation might be advantageous in providing adjunct guidance to people with ostomies.

Implications pratiques de la directive internationale sur les stomies WCET® 2020

Laurent O. Chabal, Jennifer L. Prentice and Elizabeth A. Ayello

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.2.10-21

Résumé

La deuxième édition de la directive internationale sur les stomies (IOG) WCET® a été lancée en décembre 2020 comme une mise à jour de la directive originale publiée en 2014. L’objectif de cet article est de présenter les 15 recommandations couvrant quatre domaines clés (formation, aspects holistiques et soins pré et postopératoires) et de résumer les concepts clés que les soignants doivent adapter pour les transposer dans leur pratique. L’article comprend également des informations sur l’impact du nouveau coronavirus 2019 sur les soins des stomies.

Remerciements

Le WCET® tient à remercier tous les pairs examinateurs et les organisations qui ont fourni des commentaires et des contributions à la directive internationale sur les stomies 2020. Bien que le WCET® reconnaisse avec gratitude la subvention éducative reçue de Hollister pour soutenir le développement de l’IOG 2020, la directive est le travail seul et indépendant du WCET® et n’a été influencée en aucune façon par l’entreprise qui a fourni la subvention éducative sans restriction.

Les auteurs, le corps professoral, le personnel et les organisateurs, y compris les conjoints/partenaires (le cas échéant), qui sont en position d’exercer un contrôle sur le contenu de cette activité de CME/NCPD ont déclaré qu’ils n’ont aucune relation financière avec des sociétés commerciales en rapport avec cette activité de formation, ni aucun intérêt financier dans ces sociétés.

Pour obtenir des crédits de CME, vous devez lire l’article de CME et répondre au quiz en ligne, en répondant correctement à au moins 7 des 10 questions. Cette activité de formation continue expirera le mercredi 31 mai 2023 pour les médecins et le samedi 3 juin 2023 pour les infirmières et infirmiers. Tous les tests sont désormais uniquement en ligne ; passez le test sur http://cme.lww.com pour les médecins et sur www.NursingCenter.com/CE/ASWC pour les infirmières et infirmiers. Les informations complètes sur le NCPD/CME se trouvent à la dernière page de cet article.

© Advances in Skin & Wound Care et le World Council of Enterostomal Therapists.

Introduction

Les directives sont des documents vivants et dynamiques qui doivent être révisés et mis à jour, généralement tous les cinq ans, pour tenir compte des nouvelles données. C’est pourquoi, en décembre 2020, le World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® (WCET®) a publié la deuxième édition de sa directive internationale sur les stomies (IOG).1 L’IOG 2020 s’appuie sur la directive initiale IOG publiée en 2014. 2Des centaines de références ont servi de base à la recherche documentaire des articles publiés entre mai 2013 et décembre 2019. La directive utilise plusieurs termes reconnus internationalement pour désigner les prestataires qui ont des connaissances spécialisées dans le soin des stomies, notamment les infirmiers et infirmières stomathérapeutes ainsi que les médecins. 1 Toutefois, pour les besoins de cet article, les auteurs utiliseront les termes “soignants stomathérapeutes“ et

“personne stomisée“ par souci de cohérence.

Élaboration de la Directive

Une description détaillée de la méthodologie de la directive IOG 2020 peut être trouvée ailleurs.1 Brièvement, le processus comprenait une recherche de la littérature publiée en anglais de mai 2013 à décembre 2019 par les auteurs de cet article, qui composent le groupe d’élaboration de la directive. Plus de 340 articles ont été examinés. Pour chaque article identifié, un membre du panel rédige un résumé, puis tous les trois confirment ou révisent le classement des données de l’article. Les données ont été catégorisées, définies et compilées dans un tableau qui est inclus dans la directive et peut être consulté sur le site internet du WCET®. La solidité des recommandations a été évaluée en utilisant un système alphabétique (A+, A, A-, etc.). Les réactions de la communauté mondiale de stomathérapie ont été sollicitées, et 146 personnes ainsi que 45 organisations ont été invitées à commenter les résultats. Parmi ceux-ci, 104 personnes et 22 organisations ont renvoyé des commentaires, qui ont été utilisés pour finaliser la directive.

Aperçu de la Directive

Le WCET® étant une association internationale comptant des membres dans plus de 65 pays, un fort accent est mis sur la diversité des cultures, des religions et des niveaux de ressources, de sorte que l’IOG 2020 puisse être appliquée aussi bien dans les pays riches en ressources que dans les pays pauvres en ressources. L’avant-propos a été rédigé par le Dr Larry Purnell, auteur du modèle Purnell pour la compétence culturelle (inconsciemment incompétent, consciemment incompétent, consciemment compétent, inconsciemment compétent).3-5 Comme pour la directive 2014, les membres du WCET® et les délégués internationaux ont été invités à soumettre des rapports sur la culture de leur pays, et 22 ont été reçus et intégrés à l’élaboration de la directive.

Étant donné que l’IOG 2020 est destinée à servir de guide aux soignants pour la pratique des soins aux personnes stomisées, une nouvelle section sur la mise en œuvre de la directive a été ajoutée à cette édition. Une recommandation pour la formation des infirmiers et infirmières constitue également une nouveauté. Un glossaire des termes et des ressources pédagogiques utiles sont également inclus dans les différentes annexes. Les 15 recommandations de l’IOG 2020 sont énumérées dans le Tableau 1. Les recommandations ont été traduites en chinois (Tableau additionnel 1), en français (Tableau additionnel 2), en portugais (Tableau additionnel 3) et en espagnol (Tableau additionnel 4) et sont également disponibles sur le site internet du WCET® (www.wcetn.org).

Tableau 1 Recommandations de la directive internationale sur les stomies WCET® 2020

Formation

Les données appuient quatre recommandations de l’IOG 2020 sur la formation (Tableau 1). Une personne qui subit une intervention chirurgicale entraînant la création d’une stomie a besoin de connaissances concernant son type de stomie, les stratégies de soins telles que les poches de stomie, et l’impact que la stomie aura sur son mode de vie.6 Par conséquent, les besoins de ces patients vont au-delà de ce qui peut être enseigné dans les programmes de formation initiale en soins infirmiers. Zimnicki et Pieper7 ont mené une enquête auprès d’étudiants infirmiers et ont constaté qu’un peu moins de la moitié d’entre eux (47,8%) n’avaient pas d’expérience dans le soin de patients stomisés. Pour ceux qui en avaient, ils se sentaient plus confiants dans la vidange de la poche.7 Les résultats de Cross et de ses collègues8 confirment également que les infirmières et infirmiers sans formation spécialisée de stomathérapie se sentent plus confiants dans la vidange de la poche de stomie que dans les autres compétences en matière de soins de stomie. Duruk et Uçar9 en Turquie et Li et ses collègues10 en Chine révèlent également que les infirmiers et infirmières des équipes manquent de connaissances adéquates sur les soins aux patients stomisés. De meilleurs résultats en matière de soins de stomie ont été signalés lorsque les patients sont pris en charge par des infirmiers et infirmières ayant reçu une formation spécialisée de stomathérapie. Cela inclut les recherches menées en Espagne par Coca et ses collègues,11 au Japon par Chikubu et Oike,12 et au Royaume-Uni par Jones.13

Depuis plus de 40 ans, le WCET® fait valoir l’importance d’une formation spécialisée en stomathérapie pour les infirmières et infirmiers afin de mieux répondre aux besoins des patients et de leurs familles.6 D’autres organisations, telles que la Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing Society aux États-Unis, Nurses Specialised in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada et l’Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK, ont également plaidé en faveur d’une formation infirmière spécialisée. Les modifications suggérées comprennent des programmes d’études basés sur les compétences et des listes de contrôle des aptitudes et des performances professionnelles nécessaires à l’infirmière spécialisée pour fournir des soins appropriés aux patients stomisés et à leurs familles.14-17 La pratique fondée sur des données probantes exige que les professionnels de la santé se tiennent au courant des nouvelles techniques, compétences et connaissances ; la formation continue est nécessaire.

Les Aspects Holistiques Des Soins: Culture et Religion

La littérature soutient trois recommandations hautement classées liées aux soins holistiques dans le cadre de l’IOG 2020 (Tableau 1) et confirme la nécessité de les prendre en compte lors des soins aux personnes stomisées.

Les stomies peuvent avoir un impact sur les individus dans différents domaines tels que la vie quotidienne, la qualité de vie globale, les relations sociales, le travail, l’intimité et l’estime de soi. Une approche holistique des soins vise à reconnaître et à répondre aux besoins du patient sur les plans physiologique, psychologique, sociologique, spirituel et culturel,18 surtout lorsque la situation du patient est complexe.19 Par conséquent, la mise en œuvre d’une approche holistique de la pratique est cruciale pour aborder tous les problèmes potentiels.20

De nombreux outils existent pour évaluer la qualité de vie des patients, l’adaptation aux soins personnels, l’adaptation sociale et/ou l’état psychologique.21,22 Ils fournissent des informations importantes aux infirmiers et infirmières dans leur prise de décision clinique, même si, comme toujours, le jugement clinique reste pertinent. Les soins holistiques étant multidimensionnels, l’utilisation de diverses méthodes permettra une approche intégrative et globale de la prise en charge des patients stomisés.

La définition de la santé donnée par l’Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (OMS)23 est toujours d’actualité. Les origines, les croyances, la religion, la culture, le sexe et l’âge d’un individu influencent son interprétation de la maladie et des pathologies.24-26 Pour les professionnels de la santé, la nécessité de comprendre ces influences et leur impact réel sur le patient, la famille et/ou le ou les soignants est essentielle car elle fournira des informations clés pour co-construire les soins des stomies.

Le modèle de compétence culturelle du Dr Larry Purnell3,4 peut être facilement appliqué aux soins des stomies.5 Il peut aider les infirmiers et infirmières à fournir des soins culturellement compétents aux patients stomisés. L’intégration d’une compétence culturelle efficace améliorera les relations entre les patients, les familles et les professionnels de la santé,27 surtout si les patients et/ou les familles ont du mal à faire face à la situation.28

Les infirmiers et infirmières spécialisés et non spécialisés ont un rôle clé dans l’information du patient, de la famille et des soignants.29 Ils aideront, étape par étape, à soutenir le développement de compétences spécifiques et la mise en œuvre de stratégies d’adaptation personnalisées. Les conseils et le soutien des infirmiers et infirmières peuvent réduire les complications liées à la stomie,13,30,31 et le fait d’écouter et de prendre en compte les émotions des patients améliore les soins personnels des individus.32

La prise en compte de la Charte internationale des droits des stomisés33 lors de la prestation des soins aux stomisés améliorera la qualité de vie des patients, car elle favorise leur autonomisation et renforce la collaboration entre les patients, les familles, les soignants et les professionnels de la santé.

La section 6 de l’IOG 2020 offre une perspective internationale sur les soins de stomie. Avec les contributions de 22 pays, cette version est plus inclusive que la précédente.2 Les auteurs espèrent qu’elle aidera les soignants stomathérapeutes du monde entier lorsqu’ils prendront en charge des patients d’une autre culture, d’un autre milieu ou d’un autre système de croyances et qu’elle leur donnera ainsi de meilleures compétences pour répondre aux besoins de chaque individu.

Soins Préopératoires et Marquage du Site de la Stomie

Comme le montre le Tableau 1, quatre recommandations concernent les soins préopératoires et le marquage du site de la stomie. La littérature met l’accent sur l’information préopératoire des patients qui vont subir une chirurgie pour stomie, ce qui inclut le marquage préopératoire du site. Moins de complications sont observées chez les personnes dont les sites de stomie sont marqués avant l’opération.34,35

Les infirmiers et infirmières spécialisés n’étant pas toujours disponibles 24 heures sur 24 et 7 jours sur 7, les patients qui subissent une intervention chirurgicale non planifiée ou urgente peuvent ne pas bénéficier d’une information préopératoire et du marquage du site de la stomie. Par conséquent, la littérature soutient la formation des médecins et des infirmiers et infirmières non spécialisés au marquage du site de la stomie.34-37 Zimnicki36 a mené à bien un projet d’amélioration de la qualité pour former les infirmiers et infirmières non spécialisés au marquage du site de la stomie. Ce projet a permis d’augmenter de manière significative le nombre de patients ayant bénéficié d’un marquage préopératoire du site de la stomie et d’une information.36

Le marquage du site de la stomie est une technique et une compétence importantes dont la description détaillée dépasse le cadre de cet article. Les grands principes comprennent l’observation de l’abdomen du patient en position debout, assise, penchée et allongée (figure 1).37-41 Il existe au moins deux techniques pour identifier l’emplacement abdominal idéal.42-52 Les personnes intéressées peuvent consulter les références42-60 ainsi que le webinaire WCET® ou le guide de poche sur le marquage du site de la stomie (www.wcetn.org).52

Figure 1 positions pour le marquage du site de la stomie ©2021 Ayello, utilisé avec auorisation.

Soins Postopératoires

L’IOG 2020 énumère quatre recommandations pour les soins postopératoires afin d’aider les soignants stomathérapeutes à détecter, prévenir ou gérer et ainsi minimiser l’effet de toute complication péristomiale (Tableau 1).

La réussite du rétablissement postopératoire après une chirurgie pour stomie dépend de multiples facteurs, tant du point de vue du soignant stomathérapeute que de celui de la personne stomisée. Tous les membres de l’équipe soignante, y compris le patient, doivent avoir une conscience accrue des stratégies préventives ou correctives pour les problèmes courants qui peuvent survenir lors de la formation d’une nouvelle stomie, du remodelage d’une stomie existante ou de la fermeture d’une stomie. La capacité à reconnaître et à gérer efficacement les complications postopératoires potentielles ou existantes des stomies et les complications cutanées péristomiales (CCP) a des ramifications inhérentes à court et à long terme pour la santé, le bien-être et l’autonomie des personnes stomisées61-63 et pour la gestion des ressources de santé.64-66

Les complications postopératoires de la stomie peuvent se manifester de manière précoce ou tardive. Des complications précoces telles qu’une séparation muco-cutanée, une rétraction, une nécrose stomiale, un abcès parastomial ou une dermatite peuvent survenir dans les 30 jours suivant l’intervention. Les complications ultérieures comprennent les hernies parastomiales (HP) et les prolapsus, rétractions ou sténoses stomiales.63,67,68

Cependant, les complications postopératoires les plus courantes sont les CCP.69 Les causes fréquemment citées des CCP sont les fuites,70,71 l’absence de positionnement préopératoire de la stomie,35 les mauvaises techniques de construction chirurgicale,72 les appareillages mal ajustés et la longue durée de port des appareils.71,73

Les CCP les plus courantes comprennent la dermatite de contact irritante aiguë et chronique et la dermatite de contact allergique, la première résultant d’un contact prolongé avec des matières fécales ou de l’urine sur la peau pouvant provoquer une érosion (figure 2). L’évaluation de l’abdomen, de la stomie, de l’appareillage de stomie et des accessoires utilisés, ainsi que la capacité du patient à prendre soin de la stomie et à remettre correctement son appareillage en place sont essentielles pour déterminer la cause des fuites. Les soins de la peau, en fonction de la gravité de l’irritation ou de la dénudation, peuvent impliquer l’utilisation de poudres ou de pâtes protectrices à base de pectine, de produits d’étanchéité de la peau (lingettes ou sprays à base de copolymères d’acrylate ou de cyanoacrylates) et de barrières cutanées protectrices. Des ajustements au niveau du type d’appareillage utilisé et de la durée de port peuvent également être nécessaires pour améliorer l’état aigu et prévenir l’eczéma de contact irritant chronique.61,70,74

Figure 2 dermatite d’irritation ©2021 Chabal, utilisé avec autorisation.

La dermatite de contact allergique résulte d’une réaction indésirable à des substances contenues dans des produits appliqués sur la peau lors du nettoyage ou de la protection cutanée utilisés avant l’application ou le retrait de l’appareillage ou qui font partie de l’appareillage lui-même.74,75 La peau compromise reflète généralement la forme de l’appareillage s’il s’agit de l’allergène ou la zone où des produits de soins secondaires ont été utilisés. La peau affectée peut présenter l’aspect d’une éruption cutanée, être rougie, cloquée, démangée ou douloureuse, ou exsuder un liquide hémorragique (figure 3). Il peut être nécessaire de procéder à des tests épicutanés sur de petites zones de peau bien éloignées de la peau compromise et de la stomie afin d’identifier les agents causals spécifiques et/ou d’évaluer la pertinence d’autres produits de barrière cutanée utilisés pour obtenir une étanchéité sûre autour de la stomie.70,75

Figure 3 dermatite de contact allergique ©2021 Chabal, utilisé avec autorisation.

Les hernies parastomiales sont une complication latente qui contribue également aux CCP. Les causes comprennent la technique chirurgicale, la taille et le type de stomie, la circonférence de l’abdomen, l’âge et les conditions médicales telles que les hernies antérieures et les diverticulites liquides. La formation des chirurgiens et l’insertion prophylactique d’un engrènement en polypropylène pendant l’opération ainsi que l’information postopératoire des patients peuvent réduire l’incidence des HP (Figure 4).68,76,77 De plus, les prestataires doivent évaluer et mesurer l’abdomen du patient au niveau de la stomie afin de choisir le vêtement de soutien le plus approprié requis pour gérer le degré de protrusion de la HP, prévenir toute exacerbation supplémentaire et permettre à la stomie de continuer à fonctionner normalement.78 L’appareilage de stomie et la poche utilisés devront également être fréquemment réévalués pour tenir compte de tout changement de taille de la stomie.

Figure 4 hernie parastomiale ©2021 Chabal, utilisé avec autorisation.

L’IOG 2020 cite de nombreux outils que les soignants stomathérapeutes peuvent utiliser pour identifier et classer efficacement les CCP79,80,81 et sélectionner barrières cutanées et appareillages appropriés pour gérer les CCP.62,82

Enfin, pour renforcer l’amélioration la qualité de vie postopératoire des personnes stomisées, réduire les complications liées à la stomie et les réadmissions associées, et améliorer la pratique interprofessionnelle, il convient d’utiliser des programmes de récupération précoce ou améliorée après la chirurgie,83,84 des programmes d’information suivie et de surveillance des sorties,68,85 ainsi que des modalités de télésanté pour le conseil et la consultation à distance.86,87

Mise En Œuvre de la Directive

Pour que les directives cliniques donnent des résultats positifs pour les populations de patients visées, les recommandations proposées doivent être adoptées dans la pratique quotidienne. De multiples stratégies sont nécessaires pour en faciliter l’adoption,88,89 et les directives doivent être revues et adaptées pour les contextes cliniques spécifiques.90 Il faut donc considérer la manière dont les directives seront diffusées et mises en œuvre. Les obstacles potentiels à la mise en œuvre d’une directive peuvent inclure un manque de ressources, des programmes de santé concurrents ou un manque d’intérêt perçu pour les soins des stomies en tant que sous-spécialité médicale ou infirmière sans “champion” pour défendre et faciliter la mise en œuvre. Enfin, les directives peuvent être considérées comme trop prescriptives. La section sur la mise en œuvre de la directive dans le cadre de l’IOG 2020 fournit des conseils, et les lecteurs sont dirigés vers la directive complète pour plus d’informations.

Impact Du Covid-19 Sur les Soins de Stomie

L’examen des données pour l’IOG 2020 a précédé l’arrivée du nouveau coronavirus 2019. Au cours de la pandémie, il y a eu d’anecdotiques cas rapportés de soignants stomathérapeutes qui ont été réaffectés pour s’occuper d’autres patients. L’étendue et l’impact de ce phénomène doivent encore faire l’objet de recherches. Entre-temps, les visites virtuelles peuvent constituer une alternative sûre aux soins en présentiel pour les patients et les prestataires.91 Une étude menée par White et ses collègues92 traite de la faisabilité des visites virtuelles pour les personnes ayant une nouvelle stomie ; 90% des patients ont estimé que ces visites étaient utiles pour gérer leur stomie.92 Toutefois, une autre étude a révélé que seulement 32% des répondants savaient que la télésanté était une option.93 De plus, 71% “ne pensaient pas que « leur problème » était suffisamment grave pour demander l’aide d’un professionnel de santé“,93 bien que 57% aient signalé des affections de la peau péristomiale pendant la pandémie.93 Par ordre décroissant, les types de problèmes cutanés signalés étaient les suivants: rougeur ou éruption (79%), démangeaisons (38%), lésion (21%), saignement (19%) et autres problèmes (7%).93

Conclusions

L’IOG 2020 vise à fournir aux soignants un cadre factuel sur lequel fonder leur pratique. Les 15 recommandations de l’IOG 2020 sont applicables dans les pays où les ressources sont abondantes (infirmiers et infirmières, professionnels de la santé formés aux soins des stomies avec des appareillages et poches manufacturés), ainsi que dans les pays aux ressources limitées (infirmiers et infirmières non spécialisés, professionnels de santé et profanes qui créent des équipements de stomie à partir des ressources locales disponibles pour contenir les effluents de stomie). Des connaissances spécialisées sont nécessaires pour aider les personnes stomisées à apprendre comment appliquer, vider et changer leur appareillage et poche, mais vivre avec une stomie, c’est bien plus que cela. Tous les aspects du patient doivent être pris en compte.

Les soins holistiques aux patients doivent être individualisés et porter sur l’alimentation, les activités de la vie quotidienne, la vie sexuelle, la prière, le travail, les médicaments, l’image corporelle et d’autres préoccupations centrées sur le patient. Le choix préopératoire de l’emplacement de la stomie a été associé à de meilleurs résultats postopératoires. L’identification et l’intervention précoces pour les CCP nécessitent une information adéquate, ainsi qu’une prise de conscience du moment où il faut demander une aide professionnelle. Les infirmiers et infirmières qui ont des connaissances spécialisées dans les soins des stomies peuvent améliorer la qualité de vie des personnes stomisées, y compris de celles qui subissent des CCP.95 Les auteurs espèrent que l’IOG 2020 améliorera les résultats des soins et la réadaptation pour cette population.

Joyaux De La Pratique

- Les patients qui sont pris en charge par des professionnels de la santé ayant des connaissances spécialisées en matière de stomie obtiennent de meilleurs résultats en matière de soins.

- Il existe des outils cliniques pour faciliter l’évaluation de la peau péristomiale et les besoins en appareillage.

- L’information pré et postopératoire du patient et de sa famille doit être holistique et individualisée.

- Les patients qui connaissent une localisation de stomie pré-chirurgicale connaissent moins de complications.

- La CCP la plus courante est une fuite entraînant une dermatite irritante.

- La télésanté et la consultation à distance pourraient être avantageuses pour fournir des conseils complémentaires aux personnes ayant une stomie.

Author(s)

Laurent O. Chabal*

BSc (CBP), RN, OncPall (Cert), Dip (WH), ET, EAWT

Specialised Stoma Nurse, Ensemble Hospitalier de la Côte—Morges’ Hospital; Lecturer, Geneva School of Health Sciences, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Western Switzerland; and President Elect, WCET® 2020-2022

Jennifer L. Prentice

PhD, RN, STN, FAWMA

WCET® Journal Editor; Nurse Specialist Wound Skin Ostomy Service Hall & Prior Health and Aged Care Group, Perth, Western Australia

Elizabeth A. Ayello

PhD, MS, BSN, ETN, RN, CWON, MAPCWA, FAAN

Co-Editor in Chief, Advances in Skin and Wound Care;

President, Ayello, Harris & Associates, Copake, New York;

WCET® President, 2018-2022; WCET® Executive Journal Editor Emerita, Perth, Western Australia; and Faculty Emerita, Excelsior College School of Nursing, Albany, New York

* Corresponding author

References

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® International Ostomy Guideline. Chabal LO, Prentice JL, Ayello EA, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET®; 2020.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® International Ostomy Guideline. Zulkowski K, Ayello EA, Stelton S, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET®; 2014.

- Purnell L. Transcultural health care: a culturally competent approach. Philadelphia: F A Davis Co; 2013.

- Purnell L. Guide to culturally competent health care. Philadelphia: F A Davis Co; 2014.

- Purnell L. The Purnell Model applied to ostomy and wound care. WCET J 2014;34(3):11-8.

- Gill-Thompson SJ. Forward to second edition. In: Erwin-Toth P, Krasner DL, eds. Enterostomal Therapy Nursing. Growth & Evolution of a Nursing Specialty Worldwide. A Festschrift for Norma N. Gill-Thompson ET. 2nd ed. Perth, Western Australia: Cambridge Publishing; 2020;10-1.

- Zimnicki K, Pieper B. Assessment of prelicensure undergraduate baccalaureate nursing students: ostomy knowledge, skill experiences, and confidence in care. Ostomy Wound Manage 2018;64(8):35-42.

- Cross HH, Roe CA, Wang D. Staff nurse confidence in their skills and knowledge and barriers to caring for patients with ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41(6):560-5.

- Duruk N, Uçar H. Staff nurses’ knowledge and perceived responsibilities for delivering care to patients with intestinal ostomies. A cross-sectional study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;40(6):618-22.

- Li, Deng B, Xu L, Song X, Li X. Practice and training needs of staff nurses caring for patients with intestinal ostomies in primary and secondary hospital in China. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(5):408-12.

- Coca C, Fernández de Larrinoa I, Serrano R, García-Llana H. The impact of specialty practice nursing care on health-related quality of life in persons with ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(3):257-63.

- Chikubu M, Oike M. Wound, ostomy and continence nurses competency model: a qualitative study in Japan. J Nurs Healthc 2017;2(1):1-7.

- Jones S. Value of the Nurse Led Stoma Care Clinic. Cwm Taf Health Board, NHS Wales. 2015. www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/research-and-innovation/innovation-in-nursing/~/-/media/b6cd4703028a40809fa99e5a80b2fba6.ashx. Last accessed March 4, 2021.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. ETNEP/REP Recognition Process Guideline. 2017. https://wocet.memberclicks.net/assets/Education/ETNEP-REP/ETNEP%20REP%20Guidelines%20Dec%202017.pdf. Last accessed March 4, 2021.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. WCET Checklist for Stoma REP Content. 2020. www.wcetn.org/assets/Education/wcet-rep%20stoma%20care%20checklist-feb%2008.pdf. Last accessed March 4, 2021.

- Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, Guideline Development Task Force. WOCN Society clinical guideline: management of the adult patient with a fecal or urinary ostomy-an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2018;45(1):50-8.

- Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society Task Force. Wound, ostomy, and continence nursing: scope and standards of WOC practice, 2nd edition: an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2018;45(4):369-87.

- Wallace S. The Importance of holistic assessment—a nursing student perspective. Nuritinga 2013;12:24-30.

- Perez C. The importance of a holistic approach to stoma care: a case review. WCET J 2019;39(1):23-32.

- The importance of holistic nursing care: how to completely care for your patients. Practical Nursing. October 2020. www.practicalnursing.org/importance-holistic-nursing-care-how-completely-care-patients. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Knowles SR, Tribbick D, Connell WR, Castle D, Salzberg M, Kamm MA. Exploration of health status, illness perceptions, coping strategies, psychological morbidity, and quality of life in individuals with fecal ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(1):69-73.

- Vural F, Harputlu D, Karayurt O, et al. The impact of an ostomy on the sexual lives of persons with stomas—a phenomenological study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(4):381–4.

- World Health Organization. What is the WHO definition of health? www.who.int/about/who-we-are/frequently-asked-questions. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Baldwin CM, Grant M, Wendel C, et al. Gender differences in sleep disruption and fatigue on quality of life among persons with ostomies. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5(4):335-43.

- World Health Organization. Gender, equity and human rights. 2020. www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/indigenous-peoples/en. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Forest-Lalande L. Best-practice for stoma care in children and teenagers. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2019;17(S5):S12-3.

- Qader SAA, King ML. Transcultural adaptation of best practice guidelines for ostomy care: pointers and pitfalls. Middle East J Nurs 2015;9(2):3-12.

- Iqbal F, Kujan O, Bowley DM, Keighley MRB, Vaizey CJ. Quality of life after ostomy surgery in Muslim patients—a systematic review of the literature and suggestions for clinical practice. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(4):385-91.

- Merandy K. Factors related to adaptation to cystectomy with urinary diversion. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(5):499-508.

- de Gouveia Santos VLC, da Silva Augusto F, Gomboski G. Health-related quality of life in persons with ostomies managed in an outpatient care setting. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(2):158-64.

- Ercolano E, Grant M, McCorkle R, et al. Applying the chronic care model to support ostomy self-management: implications for oncology nursing practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2016;20(3):269-74.

- Xu FF, Yu Wh, Yu M, Wang SQ, Zhou GH. The correlation between stigma and adjustment in patients with a permanent colostomy in the midlands of China. WCET J 2019;39(1):24-39.

- International Ostomy Association. Charter of Ostomates Rights. www.ostomyinternational.org/about-us/charter.html. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Watson AJM, Nicol L, Donaldson S, Fraser C, Silversides A. Complications of stomas: their aetiology and management. Br J Community Nurs 2013;18(3):111-2, 114, 116.

- Baykara ZG, Demir SG, Ayise Karadag A, et al. A multicenter, retrospective study to evaluate the effect of preoperative stoma site marking on stomal and peristomal complications. Ostomy Wound Manage 2014;60(5):16-26.

- Zimnicki KM. Preoperative teaching and stoma marking in an inpatient population: a quality improvement process using a FOCUS-Plan-Do-Check-Act Model. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(2):165-9.

- WOCN Committee Members, ASCRS Committee Members. ASCRS and WOCN joint position statement on the value of preoperative stoma marking for patients undergoing fecal ostomy surgery. JWOCN 2007;34(6):627-8.

- Salvadalena G, Hendren S, McKenna L, et al. WOCN Society and ASCRS position statement on preoperative stoma site marking for patients undergoing colostomy or ileostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(3):249-52.

- Salvadalena G, Hendren S, McKenna L, et al. WOCN Society and AUA position statement on preoperative stoma site marking for patients undergoing urostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(3):253-6.

- Brooke J, El-GHaname A, Napier K, Sommerey L. Executive summary: Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada (NSWOCC) nursing best practice recommendations. Enterocutaneous fistula and enteroatmospheric fistula. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(4):306-8.

- Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada. Nursing Best Practice Recommendations: Enterocutaneous Fistulas (ECF) and Enteroatmospheric Fistulas (EAF). 2nd ed. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada; 2018.

- Serrano JLC, Manzanares EG, Rodriguez SL, et al. Nursing intervention: stoma marking. WCET J 2016;36(1):17-24.

- Fingren J, Lindholm E, Petersén C, Hallén AM, Carlsson E. A prospective, explorative study to assess adjustment 1 year after ostomy surgery among Swedish patients. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;64(6):12-22.

- Rust J. Complications arising from poor stoma siting. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2011;9(5):17-22.

- Watson JDB, Aden JK, Engel JE, Rasmussen TE, Glasgow SC. Risk factors for colostomy in military colorectal trauma: a review of 867 patients. Surgery 2014;155(6):1052-61.

- Banks N, Razor B. Preoperative stoma site assessment and marking. Am J Nurs 2003;103(3):64A-64C, 64E.

- Kozell, K, Frecea M, Thomas JT. Preoperative ostomy education and stoma site marking. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41(3):206-7.

- Readding LA. Stoma siting: what the community nurse needs to know. Br J Community Nurs 2003;8(11):502-11.

- Cronin E. Stoma siting: why and how to mark the abdomen in preparation for surgery. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2014;12(3):12-9.

- Chandler P, Carpenter J. Motivational interviewing: examining its role when siting patients for stoma surgery. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2015;13(9):25-30.

- Pengelly S, Reader J, Jones A, Roper K, Douie WJ, Lambert AW. Methods for siting emergency stomas in the absence of a stoma therapist. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2014;96:216-8.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. Guide to Stoma Site Marking. Crawshaw A, Ayello EA, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET; 2018.

- Mahjoubi B, Goodarzi K, Mohannad-Sadeghi H. Quality of life in stoma patients: appropriate and inappropriate stoma sites. World J Surg 2009;34:147-52.

- Person B, Ifargan R, Lachter J, Duek SD, Kluger Y, Assalia A. The impact of preoperative stoma site marking on the incidence of complications, quality of life, and patient’s independence. Dis Colon Rect 2012;55(7):783-7.

- American Society of Colorectal Surgeons Committee, Wound Ostomy Continence Nurses Society® Committee. ASCRS and WOCN® joint position statement on the value of preoperative stoma marking for patients undergoing fecal ostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2007;34(6):627-8.

- AUA and WOCN® Society joint position statement on the value of preoperative stoma marking for patients undergoing creation of an incontinent urostomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009;36(3):267-8.

- Cronin E. What the patient needs to know before stoma siting: an overview. Br J Nurs 2012;21(22):1304, 1306-8.

- Millan M, Tegido M, Biondo S, Garcia-Granero E. Preoperative stoma siting and education by stomatherapists of colorectal cancer patients: a descriptive study in twelve Spanish colorectal surgical units. Colorectal Dis 2010;12(7 Online):e88-92.

- Batalla MGA. Patient factors, preoperative nursing Interventions, and quality of life of a new Filipino ostomates. WCET J 2016;36(3):30-8.

- Danielsen AK, Burcharth J, Rosenberg J. Patient education has a positive effect in patients with a stoma: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 2013;15(6):e276-83.

- Stelton S, Zulkowski K, Ayello EA. Practice implications for peristomal skin assessment and care from the 2014 World Council of Enterostomal Therapists International Ostomy Guideline. Adv Skin Wound Care 2015;28(6):275-84.

- Colwell JC, Bain KA, Hansen AS, Droste W, Vendelbo G, James-Reid S. International consensus results. Development of practice guidelines for assessment of peristomal body and stoma profiles, patient engagement, and patient follow-up. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(6):497-504.

- Maydick-Youngberg D. A descriptive study to explore the effect of peristomal skin complications on quality of life of adults with a permanent ostomy. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(5):10-23.

- Nichols TR, Inglese GW. The burden of peristomal skin complications on an ostomy population as assessed by health utility and their physical component: summary of the SF-36v2®. Value Health 2018;21(1):89-94.

- Neil N, Inglese G, Manson A, Townshend A. A cost-utility model of care for peristomal skin complications. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;34(1):62.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad BS, Inglese G, Eaves D, Oster G. Risk and economic burden of peristomal skin complications following ostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(2):143-9.

- Koc U, Karaman K, Gomceli I, et al. A retrospective analysis of factors affecting early stoma complications. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(1):28-32.

- Hendren S, Hammond K, Glasgow SC, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for ostomy surgery. J Dis Colon Rectum 2015;58:375-87.

- Roveron G. An analysis of the condition of the peristomal skin and quality of life in ostomates before and after using ostomy pouches with manuka honey. WCET J 2017;37(4):22-5.

- Stelton S. Stoma and peristomal skin care: a clinical review. Am J Nurs 2019;119(6):38-45.

- Recalla S, English K, Nazarali R, Mayo S, Miller D, Gray M. Ostomy care and management a systematic review. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;40(5):489-500.

- Carlsson E, Fingren J, Hallen A-M, Petersen C, Lindholm E. The prevalence of ostomy-related complications 1 year after ostomy surgery: a prospective, descriptive, clinical study. Ostomy Wound Manage 2016;62(10):34-48.

- Steinhagen E, Colwell J, Cannon LM. Intestinal stomas—postoperative stoma care and peristomal skin complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2017;30(3):184-92.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. WCET Ostomy Pocket Guide: Stoma and Peristomal Problem Solving. Ayello EA, Stelton S, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET, 2016.

- Cressey BD, Belum VR, Scheinman P, et al. Stoma care products represent a common and previously underreported source of peristomal contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 2017;76(1):27-33.

- Tabar F, Babazadeh S, Fasangari Z, Purnell P. Management of severely damaged peristomal skin due to MARSI. WCET J 2017;37(1):18.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad BS, Inglese G, Lamerato L, Oster G. Clinical and economic burden of peristomal skin complications in patients with recent ostomies. J Wound, Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(4):350.

- Association Stoma Care Nurses. ASCN Stoma Care National Clinical Guidelines. London, England: ASCN UK; 2016.

- Herlufsen P, Olsen AG, Carlsen B, et al. Study of peristomal skin disorders in patients with permanent stomas. Br J Nurs 2006;15(16):854-62.

- Ay A, Bulut H. Assessing the validity and reliability of the peristomal skin lesion assessment instrument adapted for use in Turkey. Ostomy Wound Manage 2015;61(8):26-34.

- Runkel N, Droste W, Reith B, et al. LSD score. A new classification system for peristomal skin lesions. Chirurg 2016;87:144-50.

- Buckle N. The dilemma of choice: introduction to a stoma assessment tool. GastroIntestinal Nurs 2013;11(4):26-32.

- Miller D, Pearsall E, Johnston D, et al. Executive summary: enhanced recovery after surgery best practice guideline for care of patients with a fecal diversion. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(1):74-7.

- Hardiman KM, Reames CD, McLeod MC, Regenbogen SE. A patient-autonomy-centered self-care checklist reduces hospital readmissions after ileostomy creation. Surgery 2016;160(5):1302-8.

- Harputlu D, Özsoy SA. A prospective, experimental study to assess the effectiveness of home care nursing on the healing of peristomal skin complications and quality of life. Ostomy Wound Manage 2018;64(10):18-30.

- Iraqi Parchami M, Ahmadi Z. Effect of telephone counseling (telenursing) on the quality of life of patients with colostomy. JCCNC 2016;2(2):123-30.

- Xiaorong H. Mobile internet application to enhance accessibility of enterostomal therapists in China: a platform for home care. WCET J 2016;36(2):35-8.

- Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM. Selecting, presenting, and delivering clinical guidelines: are there any “magic bullets”. Med J Aust 2004;180(6 Suppl):S52-4.

- Rauh S, Arnold D, Braga S, et al. Challenge of implementing clinical practice guidelines. Getting ESMO’s guidelines even closer to the bedside: introducing the ESMO Practising Oncologists’ checklists and knowledge and practice questions. ESMO Open 2018;3:e000385.

- Fletcher J, Kopp P. Relating guidelines and evidence to practice. Prof Nurse 2001;16:1055-9.

- Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa P, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. JAMIA 2020;27(7):1132-5.

- White T, Watts P, Morris M, Moss J. Virtual postoperative visits for new ostomates. CIN 2019;37(2):73-9.

- Spencer K, Haddad S, Malanddrino R. COVID-19: impact on ostomy and continence care. WCET J 2020;40(4):18-22.

- Russell S. Parastomal hernia: improving quality of life, restoring confidence and reducing fear. The importance of the role of the stoma nurse specialist. WCET J 2020;40(4):36-9.