Volume 40 Number 2

Therapeutic patient education; A multifaceted approach to healthcare

Laurence Lataillade and Laurent Chabal

Keywords Wound care, Therapeutic patient education, person-centred care, stomal therapy

For referencing Lataillade L and Chabal L . Therapeutic patient education; A multifaceted approach to healthcare. WCET® Journal 2020;40(2):35-42.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.2.35-42

Abstract

This contribution presents a literature review of therapeutic patient education (TPE) in addition to providing a summary of an oral presentation given by two wound care specialists at a European Congress. It relates this to models of care in nursing science and to other research that contributes to this approach at the core of healthcare practice.

Therapeutic patient education: an introduction to its practical application in patients with stomas and/or wounds

Up until 1970, educational approaches were rare and limited to a few isolated interventions such as the ‘manual for diabetics’. In 1972, Leona Miller, an American doctor, demonstrated the positive effects of patient education. Using a pedagogical approach, she enabled patients from under-resourced areas of Los Angeles living with diabetes to control their pathology and improve their independence by relying on less medication1.

In 1975, Professor Jean Philippe Assal, a diabetologist from Geneva, Switzerland, adopted this concept and created a department for the treatment and education of diabetes at Geneva University Hospitals. He created an innovative, interdisciplinary team consisting of nurses, physicians, dieticians, psychologists, caregivers, art therapists and physiotherapists, all with the goal of encouraging patient engagement in their learning2. The team was inspired by person-centred theories developed by Carl Rogers3, work by Kübler-Ross on the grief process4, contributions from Geneva on education science in adult learning, and work on the conceptions of learners of didactics and epistemology of science in Geneva.

Since then, therapeutic education of patients (TPE) has been developed for patients with different chronic diseases and disorders, such as asthma, pulmonary insufficiency, cancer, inflammatory bowel disease and, in particular, for patients with stomas and/or wounds. The aim of TPE is to assist patients and caregivers to better understand the nature of the disease a person has, the treatment strategies required and to help patients achieve a greater level of individual autonomy in how they manage and cope with their disease.

Definition of therapeutic patient education (TPE)

According to the World Health Organization (1998), TPE is education managed by healthcare providers trained in the education of patients, and is designed to enable a patient (or a group of patients and families) to manage the treatment of their condition and prevent avoidable complications, while maintaining or improving quality of life. Its principal purpose is to produce a therapeutic effect additional to that of all other interventions – pharmacological, physical therapy, etc. Therapeutic patient education is designed therefore to train patients in the skills of self-managing or adapting treatment to their particular chronic disease, and in coping processes and skills. It should also contribute to reducing the cost of long-term care to patients and to society. It is essential to the efficient self-management and to the quality of care of all long-term diseases or conditions, although acutely ill patients should not be excluded from its benefits.

Thus, “TPE should enable patients to acquire and maintain abilities that allow them to optimally manage their lives with their disease. It is therefore a continuous process that should be integrated into healthcare”5.

The premise of TPE as a healthcare approach is that it places the patient(s) or the caregiver(s) at the centre of the healthcare provider patient relationship, acknowledging them as an integral partner in healthcare processes6–8. The cornerstone of this approach is that the patient has knowledge, skills and experiences that must be valued, encouraged, stimulated and/or explored. As for health practitioners, they need to recognise and highlight the patient’s knowledge about themselves and capabilities, which requires the health practitioner to adapt their own position to care provision and education. Healthcare providers often tend to talk to patients about their disease rather than train them in daily management processes to assist patients to better manage their condition5. As Gottlieb explains9,10, it is more than a change in behaviour but a paradigmatic change that implores the practitioner to rely on the patient’s strengths rather than remedying their deficiencies and going further than Orem’s Model11 proposed.

TPE is a model of education and support for people living with one or more chronic diseases. The goal is to support the person being cared for by engaging them with their care by means of an educational program which makes sense for them and, in doing so, reduces the risk of complications12 and improves their quality of life. The tools of TPE promote a true collaboration between the patient and the healthcare practitioner. This requires a holistic, integrative and interdisciplinary approach13.

What is the objective of TPE? What position should practitioners adopt?

The goal for practitioners who employ TPE is to enable their patients to become independent in their care processes and to improve their quality of life. Nevertheless, patient goals are not always the same at every juncture. For example, the sudden arrival of the disease, such as a colonic cancer and the formation of a stoma, which is often a consequence thereof, have a major impact on the patient’s life. The ostomy patient goes through many emotional processes that are often profound and intense which sometimes overwhelms them completely.

Therapeutic patient education aims to support the patient in the stages and process of this emotional adjustment so that they can better adapt14 to and accommodate their disease and stoma in their day-to-day life. The goal is for the patient to acquire skills for managing their stoma and treatment as well as psychosocial skills to integrate their stoma into their daily life.

The challenge for practitioners is to reconcile these two types of learning in the TPE program while taking into account the difficulties encountered by the patient and their learning needs. A therapeutic relationship based on mutual trust and partnership is an indispensable condition for this educational process. In the framework of this alliance, the emphasis is placed on a relationship of moral equivalence between the patient and practitioner15.

The first educational stage within the TPE framework constitutes encouraging and making space for the patient to express themselves in order to reveal and agree on their particular needs which may not always be evident to either the patient or the health practitioner.

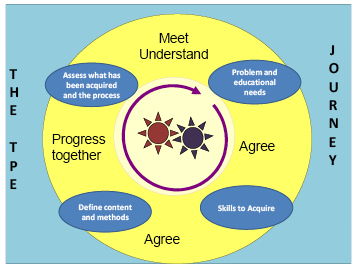

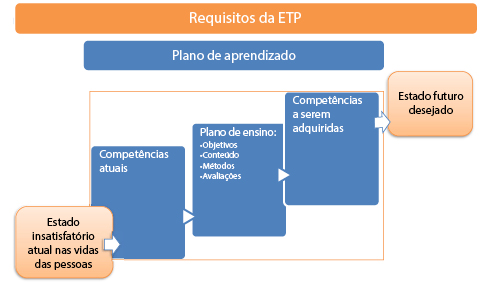

Figure 1. The TPE journey schema

In the TPE journey schema (the proposed Geneva TPE model), loosely translated from Lasserre Moutet et al.16 (Figure 1), the schema describes the following concepts:

- The two cog wheels in the middle represent the patient and the practitioner, both engaged in active movement. They both possess a specific knowledge base of their own. The practitioner possesses scientific knowledge, clinical skills and their clinical experience with other patients who have faced similar healthcare conditions; the patient possesses their individual lived experience with their disease and their treatment in addition to their own knowledge. Although this relationship is, by nature, asymmetric, it is nevertheless not ranked in terms of knowledge. The practitioner is a mediator who supports the patient in the process of transforming their knowledge to better understand their disease, consequences of the disease process and remedial medical interventions. For these gears to work, the rhythm must be adjusted. The first part of the TPE journey is especially important in upholding this engagement: the patient and practitioner must agree on the problem, revealing the reality of the situations that the patient encounters on a daily basis. For the practitioner, this involves developing a genuine interest in the patient and their life story with their disease.

- On the basis of this common understanding, educational needs, practical skills and competencies to be acquired by the patient will be elucidated in order for the patient to be able to overcome their difficulties or resolve their day-to-day problems.

- Once the goals are defined in conjunction with the patient, the strategies employed will lead the patient to encounter new ideas, to experience a new perspective on their situation, and to find alternatives to organise their daily life.

- Finally, the journey and the changes made will be evaluated jointly in order to make adjustments and continue the process.

This four-step approach can be carried out during one or more consultations.

What kind of therapeutic education should we use for patients with stomas?

Patients with stomas are confronted with physical changes and, often, a chronic disease17,18 which restricts their ability to envision a new reality for their life. One of the key roles of the stomal therapy nurse is to help the patient engage in suitable learning that will allow them to adapt, step by step, to a new life balance.

Whether the stoma is temporary or permanent, it is a shock and affects every aspect of the patient’s life: social and professional life, emotional and family life, personal identity and self-esteem. In situations where the stoma is temporary, it is often seen as a major obstacle in the person’s life for the period of time with which they live with the stoma. Once the intestine is reconnected, some patients dread that they will need a new stoma, which is indeed a possibility.

With the goal of patient independence with respect to the management of their care needs or, when this is not possible for the ostomy patient, for caregivers, stomal therapy nurses integrate TPE as a continuous process of comprehension of the patient’s lived experience and create a partnership, teaching and informing the patient throughout all stages of treatment – pre-operative, postoperative, rehabilitation, home care and short- or long-term follow-up.

This patient’s education focuses on different themes depending on the patient’s needs. For example, organisational aspects related to the stoma (care, changing the appliance, balanced digestion, food safety, etc.) which necessitate self-care. Some self-adjustment difficulties, such as a distorted self-image, low self-esteem and additional psycho-emotional implications19–21 and difficulty talking about the disease or stoma with their social circle, or resuming sexual activity, will most likely require the development of psychosocial coping skills and competencies to facilitate adaptation. The practitioner can thus apply their knowledge, clinical know-how and interpersonal skills to find appropriate teaching strategies for the patient or caregiver’s learning styles, all the while respecting/integrating patient’s limits, fears, and any resistance in order to lead them through each step of the process. Ultimately, successful integration of these processes will allow patients to perform their own self-care and adapt to their life with the ostomy and sometimes their chronic disease.

What stages do ostomy patients go through and how can we help them overcome them?

According to Selder22, the lived experience of a chronic disease is akin to a journey through a disturbed reality that is full of uncertainty and which, ultimately, leads to a restructuring of that reality.

In order to mobilise the patient’s resources, by working on their resilience23,24, consilience (coping skills)25 and empowerment26 skills, practitioners must take it upon themselves to meet the person and understand their representations, values and beliefs27,28 in order to incorporate them into their healthcare. These aspects, which are very much linked to the socio-cultural and religious context that the individual has assimilated, must also be considered in order to integrate them into the care provided to them29,30.

According to Bandura31,32, patients’ sense of self-efficacy relies on four aspects: personal mastery, modelling, social learning, and their physiological and emotional state. This generates three types of positive effects in patients with a good level of self-efficacy: the first relates to the choice of behaviours adopted, the second on the persistence of behaviours adopted, and the third on their great resilience in the face of unforeseen events and difficulties. Nurses who practise TPE will be able to mobilise, through their healthcare interventions, these four aspects of TPE for the purpose of inducing these three types of effects in the patient.

According to Diclemente et al.33, behavioural life changes can only be carried out in stages. In stomal therapy, these patient-centred approaches begin in the pre-operative stage where explanations are provided to the patient (and family where possible) on the potential need for the stoma, the surgical procedure and postoperative care (WCET® recommendation 3.1.2, SOE=B+29), even though the ostomy has not yet been confirmed. These recommendations have been adopted by the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society® (WOCN®)34.

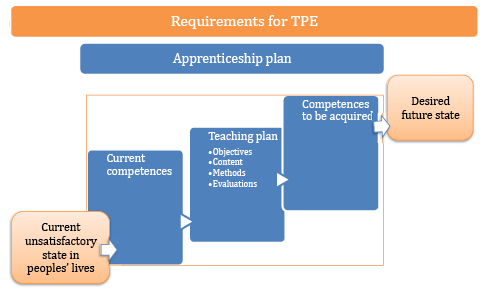

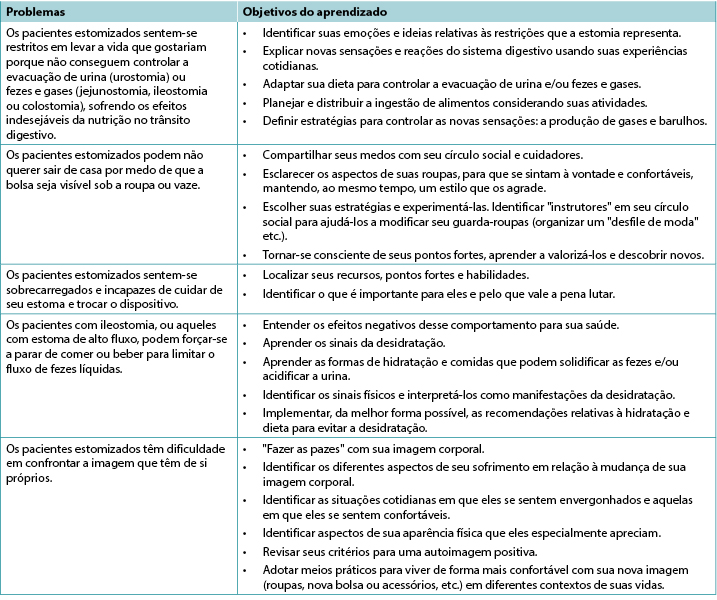

The schema, adapted and loosely translated from Martin and Savary35, describes the main steps of the learning process that need to be met and nurtured (Figure 2). Depending on the age of the patient, the knowledge, tools, and processes employed in adult education, TPE requirements may be necessary components to mobilise in order to attain them36,37. Other strategies will need to be adopted for younger populations, particularly with respect to adolescents38,39.

Figure 2. TPE requirements

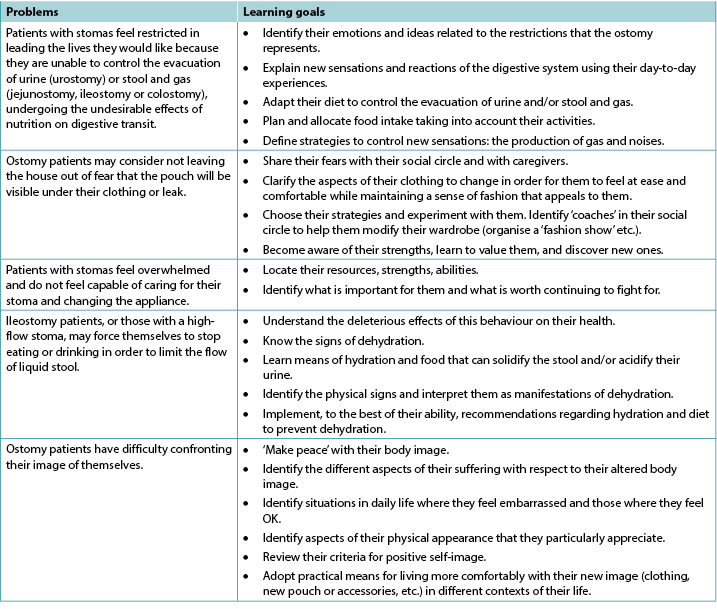

Examples of problems and goals in the therapeutic education of patients with stomas

These problems and instructional goals may apply for patients with incontinent ostomies, which are reflective of the most encountered scenarios (Table 1).

Table 1

In the case of patients with other, less common types of ostomy, like those with continent ostomies or nutritional support ostomies40,41, some of these items are still applicable and/or will need to be adapted to their particular situation; additional and more specific problems may apply. This is also the case for patients with enterocutaneous fistulae42.

In some situations, whether due to disgust, refusal, denial and/or disability (motor function, cerebral, psycho-emotional or psychiatric), the ostomy patient may not be able to undergo some or all of these processes of learning and empowerment43. This can be a short-term, medium-term or sometimes long-term problem. In these instances, recourse to a caregiver, whether a practitioner or a close relative, should be envisaged and organised. The educational process necessary for their empowerment must be carried out in a relatively similar manner with a view on promoting patient enabling to the maximum extent possible that allows the ostomy patient to return home. To the latter must be added supportive communication and management of and potential changes to interpersonal relationships and, potentially, to intimate relationships between the patients and their partners. Such changes can be generated by applying the principles of TPE, and this type of care and will need to be regularly re-evaluated and taken into consideration with a holistic approach to the patient and their respective situations.

These processes are even more complicated for patients who live alone at home, and even more so if they are elderly, as this can call their discharge home into question as well as their ability to remain at home. The need for strong communication relays and networks to be implemented in these circumstances recalls the advice offered within the 2012 American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) report45,46.

Lastly, the ostomy patient will occasionally find themselves with more than one stoma, all of which may be permanent (Figures 3 and 4). From our experience, these complex situations are more frequent than they were previously and are often related to malignant pathology.

Figure 3. Example of a person with a permanent left colostomy and a trans-ileal cutaneous ureterostomy (Bricker’s intervention) with purple urine bag syndrome47.

Figure 4. Example of a postoperative patient several days later with a temporary colostomy and a protective ileostomy. Digestive continuity would be restored in 9 months over two interventions, commencing with the downstream ostomy before the upstream ostomy, over an interval of a few weeks.

Insights and further information relating to patients with chronic wounds

Contrary to some preconceptions, stomal therapy is not solely concerned with the care of ostomy patients, even though the usage of the original term enterostomal therapist (ET)48 may lead to confusion. Indeed, the full Enterostomal Therapist Nursing Education Program (ETNEP)49 includes providing healthcare for people with wounds, people with continence disorders, those with enterocutaneous fistulae and, in some schools, for those with mastectomies. That said, wound care specialisation has become a specialist service unto itself and many ETs or stomal therapy nurses collaborate closely with wound specialists. It is important to note that these aspects of patient education are specified in the European curriculum for nurses specialising in wound care (Units 3 & 4)50–52.

In the literature, in reference to education provided to patients with wounds, knowledge has been described as a process of self-management, particularly among individuals living with a chronic disease such as a leg ulcer53. For education to be effective, the patient must acquire a perceived benefit from the changes that their involvement in the preventive activities proposed could generate. Physical, or emotional, benefits will reinforce the positive effects of the advice given54.

The benefit of using a multimedia teaching approach lies in the combination of methods for transmitting information. This helps resolve the problems encountered by the patient but also reinforces the information they are provided with55,56.

Numerous Cochrane Systematic Reviews have been carried out regarding patients with venous ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers and pressure injuries. They have revealed that:

- For patients with leg ulcers, there is not enough research available to assess strategies for supporting patients that would increase their adherence /compliance, despite the fact that compliance with compression is recognised as an important factor in preventing leg ulcer recurrence57.

- In relation to diabetic patients, there is not enough evidence to say that education – in the absence of other preventive measures – is sufficient to reduce the occurrence of foot lesions and foot/lower limb amputations58.

- Finally, as for pressure injuries, the authors have noted that the idea of patient involvement remains vague and includes a significant number of factors which vary and include a wide range of interventions and possible activities. At the same time, they clarify that this involvement in care, such as the respect of the rights of the patient, are important values which could play a role in their healthcare. This involvement could have the benefit of improving their motivation and knowledge in relation to their health. In addition, such involvement could entail an increase in their ability to manage their disease and to take care of themselves, thus improving their sense of security and enabling them to have better results when it comes to improving their health59.

As for patients with cancerous wounds, the European Oncology Nursing Society recommendations note the existence of scales for the evaluation of symptoms for the typology of these wounds, allowing for early detection of associated complications, as well as the reduction of care-related costs and of equipment used in healthcare, all the while improving patient involvement. Indeed, some of the tools described could be suggested to patients for them to use to assist with managing their condition60. In order for this to happen, education on their use will be necessary, despite the fact that these people may have lost confidence in themselves, their treatment, and their healthcare teams; even though their disease may have improved, their wounds still serve as visible stigmas of their disease.

Conclusion

Therapeutic education is the cornerstone of interventions conducted with individuals with chronic disease, or in chronic conditions, with the goal of health-related promotion, prevention and education. It is a fundamental activity that cuts across all the fields of the specialisation in stomal therapy. As every situation is unique, therapeutic education enables practitioners to develop skills in this area to improve the provision of care. It also incites us to innovate, be creative, adapt, and to think outside the box in order to find other interventional strategies; it also requires us to show humility, which may lead us to ask for help via our professional networks nationally and/or internationally.

According to Adams61, TPE remains a vast area of interventions in which the utility of educational interventions in improving healthcare impacts are still under discussion. However, the results of studies are still too limited to support their evidence. For other authors, the efficacy has, to date, been borne out by the research. For many hospitals, it is reportedly a cost-saving measure, as it enables shorter hospital stays and reduces the number of complications62–66.

Lastly, while the educational process starts at the hospital, it is followed up in both outpatient and home care services. In this sense, the implementation and maintenance of communication relays will be primordial in ensuring continuity of care, coherence and coordination of the processes undertaken as well as those of future stages that will be collaboratively decided upon. The involvement of family caregivers in these processes, with the consent of the patient and their relatives, is important. They serve as resources that cannot be neglected, even though their involvement may generate other issues that must be accounted for.

The training of healthcare professionals, particularly nurses, in the application of TPE will reinforce their expertise and efficiency67 in patient education, with the knowledge that every situation will push them to find new strategies and skills to overcome the challenges faced.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The wound section was partially based on notes taken during the University Conference Model (UCM) session68 on the subject. This session took place at the 2017 Congress of the European Wound Management Association (EWMA) in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and was presented by Julie Jordan O’Brien, Clinical Nurse Specialist Tissue Viability and Véronique Urbaniak, Advanced Practice Nurse69.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Educação terapêutica do paciente; Uma abordagem multifacetada da saúde

Laurence Lataillade and Laurent Chabal

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.2.35-42

Resumo

Esta contribuição apresenta uma revisão de literatura da educação terapêutica do paciente (ETP), além de fornecer um resumo da apresentação oral de dois especialistas em tratamento de feridas em um congresso europeu. Ela relaciona isso aos modelos de cuidado na ciência da enfermagem e a outras pesquisas que contribuem para essa abordagem no cerne da prática em saúde.

Educação terapêutica do paciente: uma introdução a sua aplicação prática em pacientes com estomas e/ou feridas

Até 1970, as abordagens educacionais eram raras e limitadas a algumas intervenções isoladas, tais como o "manual para diabéticos". Em 1972, Leona Milles, uma médica americana, demonstrou os efeitos positivos da educação de pacientes. Usando uma abordagem pedagógica, ela permitiu que pacientes de áreas menos privilegiadas de Los Angeles que viviam com diabetes controlassem sua patologia e melhorassem sua independência, dependendo menos de medicamentos1.

Em 1975, o professor Jean Philippe Assal, um especialista em diabetes de Genebra, Suíça, adotou esse conceito e criou um departamento para a educação e tratamento da diabetes nos hospitais universitários de Genebra. Ele criou uma equipe inovadora e interdisciplinar, composta por enfermeiros, médicos, nutricionistas, psicólogos, cuidadores, arteterapeutas e fisioterapeutas, todos com o mesmo objetivo de incentivar a participação do paciente na aprendizagem2. A equipe foi inspirada pelas teorias centradas no indivíduo de Carl Rogers3, pelo trabalho de Kübler-Ross sobre o processo de luto4, pelas contribuições de Genebra sobre a ciência da educação de adultos e pelo trabalho sobre as concepções dos aprendizes de didática e epistemologia da ciência em Genebra.

Desde então, a educação terapêutica do paciente (ETP) têm sido desenvolvida para pacientes com diferentes doenças e distúrbios crônicos, como asma, insuficiência pulmonar, câncer, doença inflamatória intestinal e, em particular, para pacientes com estomas e/ou feridas. O objetivo da ETP é ajudar os pacientes e cuidadores a entender melhor a natureza da doença que a pessoa possui e as estratégias de tratamento necessárias e auxiliar os pacientes a atingirem um maior nível de autonomia em como eles gerenciam e lidam com a doença.

Definição de educação terapêutica do paciente (ETP)

De acordo com a Organização Mundial da Saúde (1998), ETP é a educação gerenciada por profissionais de saúde treinados na educação de pacientes e destina-se a permitir que um paciente (ou um grupo de pacientes e famílias) gerencie o tratamento de sua condição e previna complicações evitáveis, mantendo ou melhorando a qualidade de vida. Seu objetivo principal é produzir um efeito terapêutico adicional ao de todas as outras intervenções - farmacológica, fisioterapia, etc. A educação terapêutica do paciente destina-se, portanto, a treinar os pacientes nas habilidades de autogerenciar ou adaptar o tratamento à sua doença crônica específica e nos processos e habilidades para lidar com a doença. Também deve contribuir para reduzir o custo dos cuidados de longo prazo para os pacientes e para a sociedade. Ela é essencial para o autogerenciamento eficiente e para a qualidade do atendimento prestado para todas as doenças ou condições de longo prazo, embora pacientes com doenças graves não devam ser excluídos de seus benefícios.

Portanto, "a ETP deve permitir que os pacientes adquiram e mantenham habilidades que lhes permitam gerenciar de forma ideal suas vidas com a doença. É, portanto, um processo contínuo que deve ser integrado aos cuidados de saúde”5.

A premissa da ETP como uma abordagem de assistência à saúde é que ela coloca os pacientes ou os cuidadores no centro do relacionamento do profissional de saúde com o paciente, reconhecendo-o como um parceiro integral nos processos de cuidados de saúde6–8. O alicerce dessa abordagem é que o paciente possui conhecimentos, habilidades e experiências que devem ser valorizadas, incentivadas, estimuladas e/ou exploradas. Quanto aos profissionais de saúde, eles precisam reconhecer e destacar o conhecimento dos pacientes sobre si mesmos e suas capacidades, o que exige que o profissional de saúde adapte sua própria posição em relação à prestação de cuidados e educação. Os profissionais de saúde geralmente tendem a falar com os pacientes sobre suas doenças, em vez de treiná-los nos processos diários de gerenciamento para ajudar os pacientes a gerenciar melhor suas condições5. Conforme Gottlieb explica9,10, é mais que uma mudança de comportamento, mas sim uma mudança pragmática que pede ao médico que confie nos pontos fortes do paciente em vez de remediar seus pontos fracos e que vai além do que o Modelo de Orem11 propôs.

A ETP é um modelo de educação e apoio para pessoas vivendo com uma ou mais doenças crônicas. O objetivo é apoiar a pessoa em tratamento, envolvendo-a em seus cuidados por meio de um programa educacional que faça sentido para ela e, ao fazê-lo, reduzir o risco de complicações12 e melhorar sua qualidade de vida. As ferramentas da ETP promovem uma verdadeira colaboração entre o paciente e o profissional de saúde. Isso requer uma abordagem holística, integradora e interdisciplinar13.

Qual é o objetivo da ETP? Qual posição os profissionais de saúde devem adotar?

O objetivo para os profissionais de saúde que empregam a ETP é permitir que seus pacientes se tornem independentes em seus processos de cuidados e melhorar a qualidade de vida deles. No entanto, os objetivos dos pacientes nem sempre são os mesmos em todas as ocasiões. Por exemplo, a chegada repentina da doença, como um câncer de cólon e a formação de um estoma, que geralmente é uma consequência disso, tem um grande impacto na vida do paciente. O paciente de estomia passa por muitos processos emocionais que são muitas vezes profundos e intensos e que às vezes os dominam completamente.

A educação terapêutica do paciente visa apoiar o paciente nos estágios e processos desse ajuste emocional para que eles possam se adaptar14 melhor e acomodar sua doença e estoma em suas rotinas. O objetivo é permitir que o paciente adquira as habilidades para gerenciar seu estoma e seu tratamento, assim como as habilidades psicossociais para integrar seu estoma em sua rotina.

O desafio para os profissionais de saúde é reconciliar esses dois tipos de aprendizagem no programa da ETP, ao mesmo tempo em que leva em consideração as dificuldades encontradas pelo paciente e sua necessidade de aprendizagem. Um relacionamento terapêutico baseado na confiança mútua e parceria é uma condição indispensável para esse processo educacional. No âmbito dessa aliança, a ênfase é colocada em uma relação de equivalência moral entre o paciente e o profissional15.

O primeiro estágio educacional dentro da estrutura da ETP constitui encorajar e abrir espaço para o paciente se expressar, a fim de revelar e concordar com suas necessidades particulares, que nem sempre são evidentes para o paciente ou para o profissional de saúde.

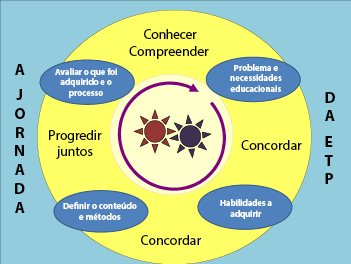

Figura 1. Esquema da jornada da ETP

No esquema da jornada da ETP (o modelo proposto de ETP de Genebra), traduzido livremente de Lasserre Moutet et al.16 (Figura 1), os seguintes conceitos são descritos:

- As duas rodas dentadas no centro representam o paciente e o profissional de saúde, ambos envolvidos em um movimento ativo. Ambos possuem uma base de conhecimento específica. O profissional de saúde possui o conhecimento científico, as habilidades clínicas e sua experiência clínica com outros pacientes que enfrentaram condições de saúde semelhantes; o paciente possui sua experiência de vida individual com sua doença e seu tratamento, além de seu próprio conhecimento. Embora essa relação seja, por natureza, assimétrica, mesmo assim ela não é classificada em termos de conhecimento. O profissional de saúde é um mediador que apoia o paciente no processo de transformação de seu conhecimento para uma melhor compreensão de sua doença, das consequências do processo da doença e das intervenções médicas remediais. Para essas engrenagens funcionarem, o ritmo deve ser ajustado. A primeira etapa da jornada da ETP é especialmente importante na manutenção desse envolvimento: o paciente e o profissional devem concordar com o problema, revelando a realidade das situações que o paciente encontra diariamente. Para o profissional de saúde, isso envolve o desenvolvimento de um interesse genuíno no paciente e em sua história de vida com a doença.

- Com base nesse entendimento comum, serão elucidadas as necessidades educacionais, as habilidades práticas e as competências a serem adquiridas pelo paciente, para que ele possa superar suas dificuldades ou resolver seus problemas cotidianos.

- Uma vez que os objetivos sejam definidos em conjunto com o paciente, as estratégias empregadas levarão o paciente a encontrar novas ideias, experimentar uma nova perspectiva sobre sua situação e encontrar alternativas para organizar sua vida cotidiana.

- Finalmente, a jornada e as mudanças feitas serão avaliadas em conjunto para fazer os ajustes e continuar o processo.

Essa abordagem de quatro etapas pode ser feita durante uma ou mais consultas.

Qual tipo de educação terapêutica devemos usar com pacientes estomizados?

Os pacientes estomizados são confrontados com mudanças físicas e, muitas vezes, uma doença crônica17,18 que restringe suas habilidades de visualizar uma nova realidade para suas vidas. Um dos papeis principais do enfermeiro estomaterapeuta é ajudar o paciente a se envolver em um aprendizado adequado que lhe permita se adaptar, passo a passo, a um novo equilíbrio na vida.

Independentemente de o estoma ser temporário ou permanente, ele é um choque e afeta todos os aspectos da vida do paciente: vida social e profissional, vida emocional e familiar, identidade pessoal e autoestima. Nas situações em que o estoma é temporário, ele é muitas vezes visto como um grande obstáculo na vida da pessoa durante o período em que ela vive com o estoma. Quando o intestino é reconectado, alguns pacientes temem que precisem de outro estoma, o que de fato é uma possibilidade.

Com o objetivo da independência do paciente em relação ao gerenciamento de seus cuidados ou, quando isso não é possível para o paciente estomizado, para os cuidadores, os enfermeiros estomaterapeutas integram a ETP como um processo contínuo de compreensão da experiência de vida do paciente e criam uma parceria, ensinando e informando o paciente durante todos os estágios do tratamento - pré-operatório, pós-operatório, reabilitação, cuidado domiciliar e acompanhamento a curto e longo prazo.

A educação desse paciente se concentra em diferentes temas, dependendo das necessidades do paciente. Por exemplo, os aspectos organizacionais relacionados ao estoma (cuidado, troca do aparelho, digestão balanceada, segurança alimentar, etc.) que requerem o autocuidado. Algumas dificuldades de autoajuste, tais como autoimagem distorcida, baixa autoestima e implicações psicoemocionais adicionais19–21 e a dificuldade em conversar sobre a doença ou o estoma em seu círculo social, ou em retomar as atividades sexuais, provavelmente exigirão o desenvolvimento de habilidades e competências de enfrentamento da doença para facilitar a adaptação. Assim, o profissional pode aplicar seu conhecimento, sabedoria clínica e habilidades interpessoais para encontrar estratégias de ensino apropriadas para os estilos de aprendizado do paciente ou do cuidador, respeitando/integrando os limites, medos e qualquer resistência do paciente, a fim de guiá-lo em cada etapa do processo. Por fim, a integração bem-sucedida desses processos permitirá que o paciente realize seu próprio autocuidado e se adapte à sua vida com a estomia e, às vezes, com sua doença crônica.

Por quais estágios os pacientes de estomia passam e como podemos ajudá-los a superá-los?

De acordo com Selder22, a experiência de vida com uma doença crônica é semelhante a uma jornada por uma realidade perturbada, cheia de incertezas e que, por fim, leva a uma reestruturação dessa realidade.

De modo a mobilizar os recursos do paciente, trabalhando em suas habilidades de resiliência23,24, consiliência (habilidades de enfrentamento)25 e empoderamento26, os profissionais de saúde devem se encarregar de conhecer o indivíduo e entender suas representações, valores e crenças27,28 para incorporá-las aos seus cuidados de saúde. Esses aspectos, que estão muito conectados ao contexto sociocultural e religioso que o indivíduo assimilou, também devem ser considerados para sua integração aos cuidados prestados ao paciente29,30.

De acordo com Bandura31,32, o senso de autoeficácia dos pacientes se baseia em quatro aspectos: domínio pessoal, modelagem, aprendizado social e seu estado fisiológico e emocional. Isso gera três tipos de efeitos positivos em pacientes com um bom nível de autoeficácia: o primeiro diz respeito à escolha dos comportamentos adotados, o segundo à persistência dos comportamentos adotados e o terceiro à sua grande resiliência diante de imprevistos e dificuldades. Os enfermeiros que praticam a ETP poderão mobilizar, por meio de suas intervenções de saúde, esses quatro aspectos da ETP para induzir esses três tipos de efeitos no paciente.

De acordo com Diclemente et al.33, as mudanças comportamentais na vida só podem ser realizadas em etapas. Na estomaterapia, essas abordagens centradas no indivíduo começam no pré-operatório, onde as explicações são dadas aos pacientes (e suas famílias, quando possível) sobre a eventual necessidade do estoma, o procedimento cirúrgico e os cuidados pós-operativos (recomendação 3.1.2 do WCET®, Evidência=B+29), embora a estomia ainda não tenha sido confirmada. Essas recomendações foram adotadas pela Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society® [Sociedade de Enfermeiros de Feridas, Estomia e Continência] (WOCN®)34.

O esquema, adaptado e traduzido livremente de Martin and Savary35, descreve os passos principais no processo de aprendizagem que precisam ser cumpridos e estimulados (Figura 2). Dependendo da idade do paciente e do conhecimento, ferramentas e processos utilizados na educação de adultos, os requisitos da ETP podem ser componentes necessários para atingí-los36,37. Outras estratégias deverão ser adotadas para a população mais jovem, especialmente em relação aos adolescentes38,39.

Figura 2. Requisitos da ETP

Exemplos de problemas e objetivos na educação terapêutica de pacientes estomizados

Esses problemas e objetivos instrutivos podem se aplicar a pacientes com estomias incontinentes, que refletem os cenários mais encontrados (Tabela 1).

Tabela 1

No caso de pacientes com outros tipos menos comuns de estomia, como estomias continentais ou estomias de suporte nutricional40,41, alguns desses itens ainda são aplicáveis e/ou precisam ser adaptados à sua situação específica; problemas adicionais e mais específicos podem ser aplicáveis. Esse também é o caso para pacientes com fístula enterocutânea42.

Em algumas situações, seja por nojo, recusa, negação e/ou deficiência (função motora, cerebral, psicoemocional ou psiquiátrica), pode ser que o paciente estomizado não seja capaz de passar por todos esses processos de aprendizado e empoderamento43. Isso pode ser um problema de curto, médio ou às vezes longo prazo. Nesses casos, o recurso a um cuidador, seja ele um profissional ou um parente próximo, deve ser previsto e organizado. O processo educativo necessário para seu empoderamento deve acontecer de uma maneira relativamente semelhante com o objetivo de promover a capacitação do paciente o máximo possível, de modo que o paciente estomizado possa voltar para casa. A isso, deve-se adicionar a comunicação de apoio e gerenciamento de possíveis mudanças nos relacionamentos interpessoais e, potencialmente, nos relacionamentos íntimos entre os pacientes e seus parceiros. Tais mudanças podem ocorrer aplicando-se os princípios da ETP, e esse tipo de atendimento deverá ser reavaliado regularmente e levado em consideração com uma abordagem holística do paciente e sua respectiva situação.

Esses processos são ainda mais complicados para pacientes que moram sozinhos, ou até mais para idosos, pois isso pode colocar em questão a residência para a alta e também sua capacidade de permanecer em casa. A necessidade de implementação de fortes redes e relés de comunicação nessas circunstâncias lembra o conselho oferecido no relatório de 2012 da American Association of Retired Persons [Associação Americana de Pessoas Aposentadas] (AARP)45,46.

Por fim, o paciente estomizado pode ocasionalmente precisar de mais de um estoma, todos os quais podem ser permanentes (Figuras 3 e 4). De acordo com nossa experiência, essas situações complexas são mais frequentes do que eram anteriormente e estão muitas vezes relacionadas à patologia maligna.

Perspectivas e informações adicionais relacionadas a pacientes com feridas crônicas

Ao contrário de alguns preconceitos, a estomaterapia não se preocupa apenas com o cuidado de pacientes estomizados, embora o uso do termo original estomaterapeuta (ET)48 possa levar a essa confusão. De fato, o Enterostomal Therapist Nursing Education Program [Programa de Educação em Enfermagem de Estomaterapia] (ETNEP)49 inclui o atendimento a pessoas com feridas, pessoas com distúrbios de incontinência, pessoas com fístulas enterocutâneas e, em algumas escolas, pessoas com mastectomias. Dito isso, a especialização em tratamento de feridas se tornou um serviço especialista por si só e muitos enfermeiros estomaterapeutas colaboram estreitamente com especialistas em feridas. É importante notar que esses aspectos da educação do paciente são especificados no currículo europeu para enfermeiros que se especializam em tratamento de feridas (Unidades 3 e 4)50–52.

Figura 3. Exemplo de uma pessoa com uma colostomia esquerda permanente e ureterostomia cutânea transileal (intervenção de Bricker) com síndrome da urina roxa na bolsa coletora47.

Figura 4. Exemplo de um paciente estomizado vários dias após a cirurgia com uma colostomia temporária e uma ileostomia protetiva. A continuidade digestiva seria restaurada em 9 meses em duas intervenções, começando com a estomia a jusante antes da estomia a montante, por um intervalo de algumas semanas.

Na literatura, em referência à educação fornecida a pacientes com feridas, o conhecimento tem sido descrito como um processo de autogerenciamento, especialmente entre indivíduos que vivem com uma doença crônica, como uma úlcera de perna53. Para a educação ser eficaz, o paciente deve adquirir um benefício percebido das mudanças que seu envolvimento nas atividades preventivas propostas podem gerar. Benefícios físicos ou emocionais reforçarão os efeitos positivos dos conselhos dados54.

O benefício do uso de uma abordagem de ensino multimídia reside na combinação de métodos para a transmissão de informações. Isso ajuda a resolver os problemas encontrados pelo paciente, mas também reforça a informação que lhes foi passada55,56.

Inúmeras revisões sistemáticas Cochrane foram realizadas em relação a pacientes com úlceras venosas, úlcera do pé diabético e lesões por pressão. Elas revelaram que:

- Para pacientes com úlceras de perna, não há pesquisas suficientes disponíveis para avaliar as estratégias de apoio aos pacientes que aumentem sua aderência/conformidade, apesar da conformidade com a compressão ser reconhecida como um fator importante na prevenção da recorrência da úlcera de perna57.

- Em relação aos pacientes diabéticos, não há evidências suficientes para dizer que a educação - na ausência de outras medidas preventivas - seja suficiente para reduzir a ocorrência de lesões no pé ou amputação do pé/membros inferiores58.

- Por fim, em relação às lesões por pressão, os autores notaram que a ideia do envolvimento do paciente continua vaga e inclui um número significativo de fatores que variam e incluem uma variedade de intervenções e atividades possíveis. Ao mesmo tempo, eles esclarecem que esse envolvimento nos cuidados, tais como respeito aos direitos do paciente, são valores importantes que podem desempenhar um papel em seus cuidados de saúde. Esse envolvimento poderia ter o benefício de melhorar a motivação do paciente e seu conhecimento em relação à sua própria saúde. Além disso, esse envolvimento poderia implicar um aumento na capacidade de gerenciar sua doença e cuidar de si mesmo, melhorando assim seu senso de segurança e permitindo-lhes obter melhores resultados quando se trata de melhorar sua saúde59.

Quanto aos pacientes com feridas cancerígenas, as recomendações da European Oncology Nursing Society [Sociedade Europeia de Enfermagem Oncológica] observam a existência de escalas para a avaliação dos sintomas da tipologia dessas feridas, permitindo uma detecção precoce de complicações relacionadas, bem como a redução dos custos relacionados ao tratamento e equipamento usado nos cuidados de saúde, aumentando o envolvimento do paciente. De fato, o uso de algumas das ferramentas descritas podem ser sugeridas aos pacientes para o gerencimento de suas condições60. Para que isso aconteça, é necessário que eles sejam educados quanto ao seu uso, apesar de que essas pessoas podem ter pedido a confiança em si mesmos, seus tratamentos e suas equipes de prestação de serviços de saúde; embora suas doenças possam ter melhorado, suas feridas ainda servem como estigmas visíveis de suas doenças.

Conclusão

A educação terapêutica é o alicerce das intervenções conduzidas em indivíduos com doença crônica, ou em condições crônicas, visando a promoção, prevenção e educação relacionadas à saúde. É uma atividade fundamental que abrange todos os campos da especialização em estomaterapia. Como cada situação é única, a educação terapêutica permite que os profissionais de saúde desenvolvam as habilidades nessa área para melhorar a prestação de serviços de saúde. Também nos incita a inovar, ter criatividade, se adaptar e pensar além do óbvio a fim de encontrar outras estratégias intervencionistas; também exige que mostremos humildade, o que pode nos levar a pedir ajuda através de nossas redes profissionais a nível nacional e/ou internacional.

De acordo com Adams61, a ETP continua sendo uma vasta área de intervenções em que a utilidade das intervenções educacionais para melhorar os impactos na saúde ainda está em discussão. No entanto, os resultados dos estudos ainda são muito limitados para apoiar sua evidência. Para outros autores, a eficácia tem sido, até o momento, comprovada pela pesquisa. Para muitos hospitais, ela é alegadamente uma medida de redução de custos, pois permite que as internações hospitalares sejam mais curtas e reduz o número de complicações62–66.

Por fim, embora o processo educacional comece no hospital, ele também é acompanhado tanto nos serviços ambulatoriais quanto nos serviços de atendimento domiciliar. Nesse sentido, a implementação e a manutenção dos relés de comunicação será primordial para garantir a continuidade do atendimento e a coerência e coordenação dos processos empreendidos e das etapas futuras que serão decididas conjuntamente. O envolvimento de cuidadores familiares nesses processos, com o consentimento do paciente e de seus parentes, é importante. Eles servem como recursos que não podem ser negligenciados, mesmo que seu envolvimento possa gerar outras questões que devem ser consideradas.

O treinamento dos profissionais de saúde, especialmente dos enfermeiros, na aplicação da ETP reforçará sua experiência e eficiência67 na educação dos pacientes, com o conhecimento de que cada situação os impulsionará a encontrar novas estratégias e habilidades para superar os desafios enfrentados.

Conflito de interesse

Os autores declaram não haver conflitos de interesse.

A seção sobre feridas foi parcialmente baseada em anotações feitas durante a sessão do University Conference Model [Modelo de Conferência Universitário] (UCM)68 sobre o assunto. A sessão aconteceu no congresso de 2017 da European Wound Management Association [Associação Europeia de Tratamento de Feridas] (EWMA) em Amsterdã, Países Baixos, e foi apresentada por Julie Jordan O’Brien, Enfermeira Clínica Especialista em Viabilidade Tecidual e Véronique Urbaniak, Enfermeira de Cuidados Avançados69.

Financiamento

Os autores não receberam financiamento para este estudo.

Author(s)

Laurence Lataillade

Clinical Specialist Nurse and Stomatherapist, Geneva University Hospitals

Laurent Chabal*

Stomal Therapy Nurse and Lecturer, Geneva School of Health Sciences, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland. Haute École de Santé Genève, HES-SO Haute École Spécialisée de Suisse Occidentale, Vice-President of WCET® 2018–2020

* Corresponding author

References

- Miller LV, Goldstein J. More efficient care of diabetic patients in a county-hospital setting. N Engl J Med 1972;286:1388–1391.

- Lacroix A, Assal JP. Therapeutic education of patients – new approaches to chronic illness, 2nd ed. Paris: Maloine; 2003.

- Rogers C. Client-centered therapy, its current practice, implications and theory. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1951.

- Kübler-Ross E. On death and dying. London: Routledge; 1969.

- World Health Organization. Therapeutic patient education, continuing education programmes for health care providers. Report of a World Health Organization Working Group; 1998. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/145294/E63674.pdf

- Stewart M, Belle Brown J, Wayne Weston W, MacWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient-centered medicine: transforming the clinical method. Oxon: Radcliffe; 2003.

- Kronenfeld JJ. Access to care and factors that impact access, patients as partners in care and changing roles of health providers. Research in the sociology of health care. Bingley: Emerald Book; 2011.

- Dumez V, Pomey MP, Flora L, De Grande C. The patient-as-partner approach in health care. Academic Med: J Assoc Am Med Coll 2015;90(4):437–1.

- Gottlieb LN, Gottlieb B, Shamian J. Principles of strengths-based nursing leadership for strengths-based nursing care: a new paradigm for nursing and healthcare for the 21st century. Nursing Leadership 2012;25(2):38–50.

- Gottlieb LN. Strengths-based nursing care: health and healing for persons and family. New York: Springer; 2013.

- Orem DE. Nursing: concepts of practice. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book Inc; 1991.

- The Official Website of the Disabled Persons Protection Commission; 2018. Available from: http://www.mass.gov/dppc/abuse-prevention/types-of-prevention.html

- Finset A, editor. Patient education and counselling journal. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2019. Available from: https://www.journals.elsevier.com/patient-education-and-counseling/

- Roy, C. The Roy adaptation model. New Jersey: Pearson; 2009.

- Price P. How we can improve adherence? Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2016;32(S1):201–5.

- Lasserre Moutet A, Chambouleyron M, Barthassat V, Lataillade L, Lagger G, Golay A. Éducation thérapeutique séquentielle en MG. La Revue du Praticien Médecine Générale 2011;25(869):2–4.

- Ercolano E, Grand M, McCorkle R, Tallman NJ, Cobb MD, Wendel C, Krouse R. Applying the chronic care model to support ostomy self-management: implications for nursing practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2016;20(3):269–74.

- World Health Organization. Non-communicable diseases; 2020. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/noncommunicable_diseases/en/

- Price B. Explorations in body image care: Peplau and practice knowledge. J Psychiatric Mental Health Nurs 1998;5(3):179–186.

- Segal N. Consensuality: Didier Anzieu, gender and the sense of touch. New York: Rodopi BV; 2009.

- Anzieu D. The skin-ego. A new translation by Naomi Segal (The history of psychoanalysis series). Oxford: Routledge; 2016.

- Selder F. Life transition theory: the resolution of uncertainty. Nurs Health Care 1989;10(8):437–40, 9–51.

- Cyrulnik B, Seron C. Resilience: how your inner strength can set you free from the past. New York: TarcherPerigee; 2011.

- Scardillo J, Dunn KS, Piscotty R Jr. Exploring the relationship between resilience and ostomy adjustment in adults with permanent ostomy. J WOCN 2016;43(3): 274–279.

- Wilson EO. Consilience: the unity of knowledge. New York: Knopf; 1998.

- Zimmerman MA. Empowerment theory, psychological, organizational and community levels of analysis. In Rappaport J, Seidman E, editors. Handbook of community psychology. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2000. p. 43–63.

- Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Behav 1988;15(2):175–183.

- Knowles SR, Tribbick D, Connel WR, Castle D, Salzberg M, Kamm MA. Exploration of health status, illness perceptions, coping strategies, psychological morbidity, and quality of life in individuals with fecal ostomies. J WOCN 2017;44(1):69–73.

- Zulkowski K, Ayello EA, Stelton S, editors. WCET international ostomy guideline. Perth: Cambridge Publishing, WCET; 2014.

- Purnell L. The Purnell Model applied to ostomy and wound care. JWCET 2014;34(3):11–18.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol Rev 1977;84(2):191–215.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Psychological review. San Francisco: Freeman WH; 1997.

- Diclemente CC, Prochaska JO. Toward a comprehensive, transtheoretical model of change: stages of change and addictive behaviours. In Miller WR, Heather N, editors. Treating addictive behaviours. processes of change. New York: Springer; 1998. p. 3–24.

- Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society – Guideline Development Task Force. WOCN® Society clinical guideline management of the adult patient with a fecal or urinary ostomy – an executive summary. J WOCN 2018;45(1):50–58.

- Martin JP, Savary E. Formateur d’adultes: se professionnaliser, exercer au quotidien. 6th ed. Lyon: Chronique Sociale; 2013.

- Lataillade L, Chabal L. Therapeutic patient education (TPE) in wound and stoma care: a rich challenge. ECET Bologna, Italy [Oral presentation]; 2011.

- Merriam SB, Bierema LL. Adult learning: linking theory and practice. Indianapolis: Jossey-Bass; 2013.

- Mohr LD, Hamilton RJ. Adolescent perspectives following ostomy surgery, J WOCN 2016;43(5): 494–498.

- Williams J. Coping: teenagers undergoing stoma formation. BJN 2017;26(17):S6–S11.

- Stroud M, Duncan H, Nightingale J. Guidelines for enteral feeding in adult hospital patients. Gut 2003;52(7):vii1–vii12.

- Roveron G, Antonini M, Barbierato M, Calandrino V, Canese G, Chiurazzi LF, Coniglio G, Gentini G, Marchetti M, Minucci A, Nembrini L, Nari V, Trovato P, Ferrara F. Clinical practice guidelines for the nursing management of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and jejunostomy (PEG/PEJ) in adult patients. An executive summary. JWCON 2018;45(4):32–334

- Brown J, Hoeflok J, Martins L, McNaughton V, Nielsen EM, Thompson G, Westendrop C. Best practice recommendations for management of enterocutaneous fistulae (ECF). The Canadian Association for Enterostomal Therapy; 2009. Available from: https://nswoc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/caet-ecf-best-practices.pdf

- Jukes M. Learning disabilities: there must be a change in attitude. BJN 2004;13(22):1322.

- Wendorf JH. The state of learning disabilities: 507 facts, trends and emerging issues. 3rd ed. New York: National Center for Learning Disabilities, Inc; 2014.

- Reinhard SC, Levine C, Samis S. Home alone: family caregivers providing complex chronic care. AARP Public Policy Institute; 2012.

- Reinhard SC, Ryan E. From home alone to the CARE act: collaboration for family caregivers. AARP Public Policy Institute, Spotlight 28; 2017.

- Peters P, Merlo J, Beech N, Giles C, Boon B, Parker B, Dancer C, Munckhof W, Teng H.S. The purple urine bag syndrome: a visually striking side effect of a highly alkaline urinary tract infection. Can Urol Assoc J 2011;5(4):233–234.

- Erwin-Toth P, Krasner DL. Enterostomal therapy nursing. Growth & evolution of a nursing specialty worldwide. A Festschrift for Norma N. Gill-Thompson, ET. 2nd ed. Perth: Cambridge Publishing; 2012.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®, Education Committee; 2020. Available from: http://www.wcetn.org/the-wcet-education

- Pokorná A, Holloway S, Strohal R, Verheyen-Cronau I. Wound curriculum for nurses: post-registration qualification wound management – European qualification framework level 5. J Wound Care 2017;26(2):S9–12, S22–23.

- Prosbt S, Holloway S, Rowan S, Pokorná A. Wound curriculum for nurses: post-registration qualification wound management – European qualification framework level 6. J Wound Care 2019;28(2):S10–13, S27.

- European Wound Management Association. EQF level 7 curriculum for nurses; 2020. Available from: https://ewma.org/it/what-we-do/education/ewma-wound-curricula/eqf-level-7-curriculum-for-nurses-11060/

- Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Peel J, Baker DW. Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Educ Couns 2003;51(3):267–275.

- Van Hecke A, Beeckman D, Grypdonck M, Meuleneire F, Hermie L, Verheaghe S. Knowledge deficits and information-seeking behaviour in leg ulcer patients, an exploratory qualitative study. J WOCN 2013;40(4):381–387.

- Ciciriello S. Johnston RV, Osborne RH, Wicks I, Dekroo T, Clerehan R, O’Neill C, Buchbinder R. Multimedia education interventions for customers about prescribed and over-the-counter medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2013. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008416/full

- Moore Z, Bell T, Carville K, Fife C, Kapp S, Kusterer K, Moffatt C, Santamaria N, Searle R. International best practice statement: optimising patient involvement in wound management. London: Wounds International; 2016.

- Weller CD, Buchbinder R, Johnston RV. Intervention for helping people adhere to compression treatments for venous leg ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2013. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008378.pub2/abstract

- Dorrestelijn JA, Kriegsman DMW, Assendelft WJJ, Valk GD. Patient education for preventing diabetic foot ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2014. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001488.pub5/abstract

- O’Connor T, Moore ZEH, Dumville JC, Patton D. Patient and lay carer education fort preventing pressure ulceration in at-risk populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2015. Available from: http://www.cochrane.org/CD012006/WOUNDS_patient-and-lay-carer-education-preventing-pressure-ulceration-risk-populations

- Probst S, Grocott P, Graham T, Gethin G. EONS recommendations for the care of patients with malignant fungating wounds. London: European Oncology Nursing Society; 2015.

- Adams R. Improving health outcomes with better patient understanding and education. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2010;3:61–72.

- Lagger G, Pataky Z, Golay A. Efficacy of therapeutic patient education in chronic diseases and obesity. Patient Educ Couns 2010;79(3):283–286.

- Kindig D, Mullaly J. Comparative effectiveness – of what? Evaluating strategies to improve population health. JAMA 2010;304(8):901–902.

- Friedman AJ, Cosby R, Boyko S, Hatt on-Bauer J, Turnbull G. Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: a systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. J Canc Educ 2011;26(1):12–21.

- Jensen BT, Kiesbye B, Soendergaard I, Jensen JB, Ammitzboell Kristensen S. Efficacy of preoperative uro-stoma education on self-efficacy after radical cystectomy; secondary outcome of a prospective randomised controlled trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2017;28:41–46.

- Rojanasarot S. The impact of early involvement in a post-discharge support program for ostomy surgery patients on preventable healthcare utilization. J WOCN 2018;45(1):43–49.

- Knebel E, editor. Health professions education: a bridge to quality (quality chasm). Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

- European Wound Management Association; 2020. Available from: http://ewma.org/what-we-do/education/ewma-ucm/

- European Wound Management Association Conference; 2017. Available from: http://ewma.org/ewma-conference/2017-519/