Volume 41 Number 3

The nursing assessment of pemphigus vulgaris ulcers

Mariana Takahashi Ferreira Costa, Luiza Keiko Matsuka Oyafuso, Mônica Antar Gamba and Kevin Y Woo

Keywords nursing, skin diseases, dermatology, vesiculobullous, acantholysis

For referencing Costa MTF et al. The nursing assessment of pemphigus vulgaris ulcers. WCET® Journal 2021;41(3):27-37

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.3.27-37

Submitted 16 March 2021

Accepted Accepted 18 July 2021

Abstract

Introduction Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is a severe autoimmune bullous dermatosis resulting in the formation of intraepidermal blisters affecting the skin and mucous membranes. Epidemiologic data shows an incidence of 0.1–0.5 per 100,000 inhabitants per year, and mortality at almost 5–10%.

Objective The objective of this integrative literature review was to examine the classification/terminology of PV ulcers according to the description of skin lesions.

Method This is an integrative review of primary studies, series/clinical reviews or validation studies that describe or evaluate PV ulcers. Search strategies included relevant papers that were published between 2011–2019 using terms such as pemphigus, skin ulcer, dermatology, diagnostic, nursing assessment. The studies were selected for analysis after application of eligibility criteria and exclusion by duplicity.

Results The initial search resulted in 2,934 publications; 14 articles were eligible for analysis. The synthesis of the studies was organised as follows – 57.14% series/clinical reviews, 50% written by physicians, 64.29% level of evidence 4. The terminology used to describe PV ulcers included skin/mucosal erythema, new erythema, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, oral lesions, epithelialisation scabs, blisters, bullae, erosions, eroded areas, erosive exudative lesions, dry erosive.

Conclusions Studies with better levels of evidence are needed on this issue in order to determine the best way to describe the lesions using the dermatological glossary for nursing assessment.

Introduction

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is a severe autoimmune bullous dermatosis in which the antibodies destroy the desmosomes, resulting in the formation of intraepidermal blisters that affect the skin and mucous membranes. PV occurs mainly between the 4th and 6th decades of life, affecting males and females with an incidence of 0.1–0.5 / 100,000 inhabitants / year and with a mortality rate of 5–10%. The disease distribution is universal, but most commonly affects people of Jewish ancestry–3.

In PV, autoantibodies act predominantly on desmoglein 3 (Dsg3) which is expressed predominantly in the deeper layers of the epidermis2,3. Identifying the layer on which acantholysis occurs is a factor that assists in the diagnosis of bullous dermatoses. For example, it is possible to differentiate PV from pemphigus foliaceus by the site where acantholysis occurs, since pemphigus foliaceus affects the granular layer whereas PV affects the spinous layer2,3. These manifestations involve the formation of blisters with consequent ulceration and skin damage which can be devastating, affecting social interaction and even loss of employment4.

The impact of disfigurement associated with PV on patients’ quality of life, self-image, family and social dynamics has been well documented4. In addition to cutaneous involvement, PV may involve mucosal tissue in the mouth, pharynx, larynx, nasal passage and ear canals (Figures 1 & 2). Areas affected by the disease can compromise normal breathing as well as the ability to speak and to eat to maintain adequate nutritional intake2,3.

Figure 1. Cutaneous lesions on trunk

Figure 2. Oral mucosa lesions

The classification of PV has been the object of studies in recent years. The Commitment Index of Skin and Mucous in Pemphigus Vulgaris uses four different parameters to score the disease clinical status: (a) the number of blisters or eroded areas; (b) the size of blisters or eroded areas; (c) evidence of the Nikolsky sign (where sliding the finger firmly with pressure over the skin separates normal-appearing epidermis, producing an erosion); and (d) mucousal involvement and sepsis. The total score may vary from 0–100, and the patients are classified as follows: Class I score 0–30; Class II 35–65; Class III 70–100, meaning that the higher the score, the more critical the status1.

Pemphigus classifications tools, the Pemphigus Disease Area Index (PDAI) and the Japanese Pemphigus Disease Severity Score (JPDSS), were compared by Shimizu et al.5. PDAI measures skin and mucosal involvement by size and number of blisters in each anatomical region, and the score ranges from 0–263. JPDSS uses parameters for scoring: (I) the ratio of affected area of skin to the body’s surface area; (II) the presence or absence of Nikolsky’s sign phenomenon; (III) the number of newly developed blisters per day; (IV) the presence or absence of oral lesions; and (V) the titer of pemphigus antibodies. Each parameter has a score ranging 0–3. In Shimizu et al.’s study5, the results show that PDAI more accurately reflects disease severity. The authors therefore propose the use of indexes to guide a uniform treatment according to grading criteria. Corticotherapy is the treatment of choice, and it can be associated with immunosuppressants if there is no improvement with isolated corticotherapy2,3.

Although considered a relatively rare disease, there is a need for nurses to recognise skin lesions associated with PV and communicate appropriate findings in order to help patients seek early treatment, evaluate disease progression, and monitor responses to treatment6. The purpose of this integrative review was to describe the taxonomy for the description and assessment of skin changes related to PV by nurses.

Method

This integrative review was conducted to identify, analyse and synthesise studies that use qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods in this theme7. We have chosen the method described by Mendes7 to guide the review which consisted of six stages: (1) formulation of the guiding question; (2) establishment of criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies and data collection (search in the literature); (3) categorisation of studies; (4) evaluation of studies included in the review; (5) analysis and interpretation of data; and (6) synthesis of the knowledge evidenced in the articles analysed (presentation of the results)7.

Formulation of the guiding question

The research question was – How are the lesions that characterise PV described in the literature in its definition and classification?

Establishment of criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies and data collection

The medical and nursing literature was searched from 2011–2019 in conjunction with a librarian to assist in answering the research question. Searches included Web of Science, LILACS, EMBASE, SCOPUS, PUBMED, BVS, CINAHL and COCHRANE with specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. To identify relevant publications, databases were searched using the following key terms – dermatology, pemphigus, skin ulcer, diagnostic and nursing assessment. The inclusion criteria included articles published in English, Spanish and Portuguese, peer-reviewed literature and consensus documents; the dates of publication were from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2019. Commentary and editorials were excluded.

Categorisation of studies

Selected studies were then categorised according to the six levels of evidence8:

• Level 1: evidence from meta-analysis of multiple controlled and randomised studies.

• Level 2: evidence from individual studies with experimental design.

• Level 3: evidence from quasi-experimental studies, time series or case-controls.

• Level 4: evidence from descriptive studies (non-experimental or qualitative approach).

• Level 5: evidence of case / experience reports.

• Level 6: evidence based on expert committee opinions, including interpretations of non-research based information, regulatory or legal opinions.

Evaluation of studies included in the review

This step included the evaluation of the studies as well as data extraction. A standardised data collection form was used to extract the following information: authors; professional category of authors; title of the article; journal; year of publication; level of evidence; goals; methodological design; sampling detail; synthesis of information; evaluation/assessment of skin ulcers in pemphigus; methodology used to validate the instrument; description of the instrument; terminology used to characterise ulcers; and results and conclusions.

Analysis and interpretation of data

The data evaluation stage included evaluating the quality of the primary sources using a specific methodological approach to determine the quality of the source. The data were evaluated and coded according to two criteria – the methodological rigour and the relevance to the topic of skin assessment. Studies were analysed and the rigour rated on a score from 0–4. The relevance to the topic was also scored and indicated, with 1 having no relevance to the topic and 2 indicating the article was relevant.

Synthesis / presentation of results

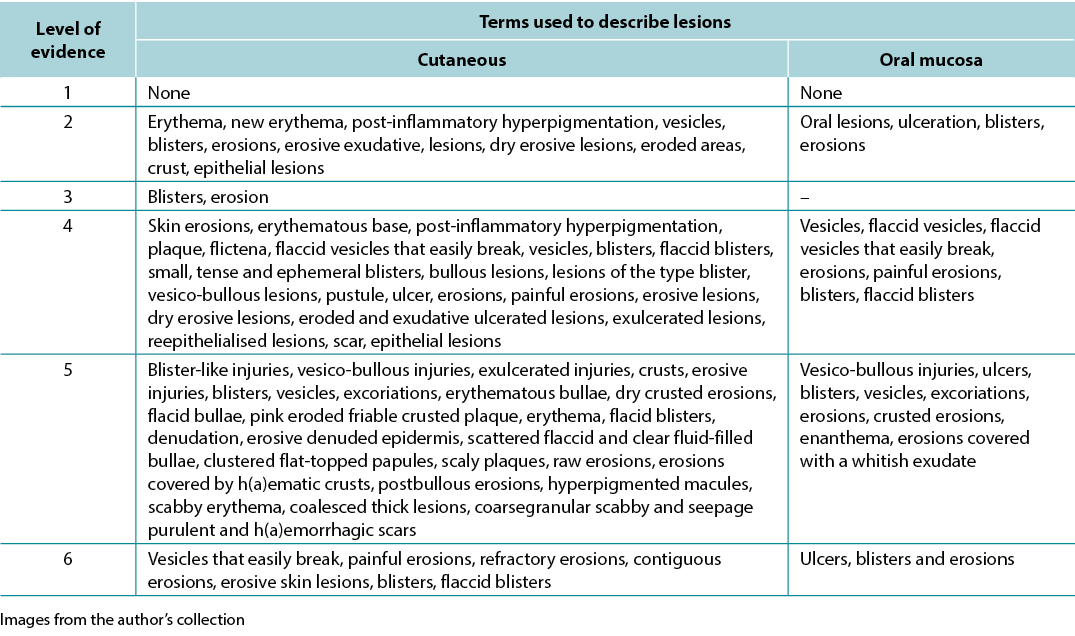

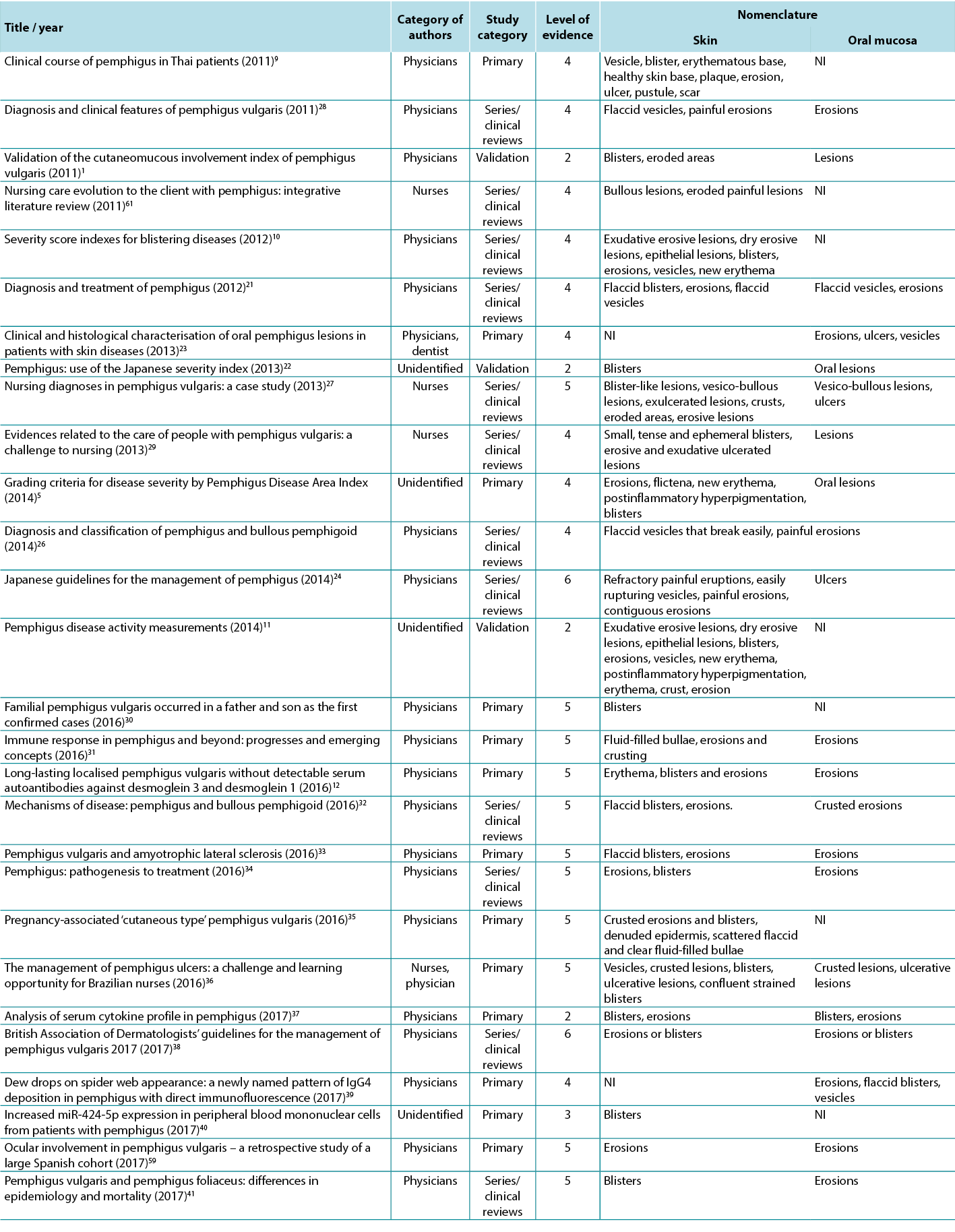

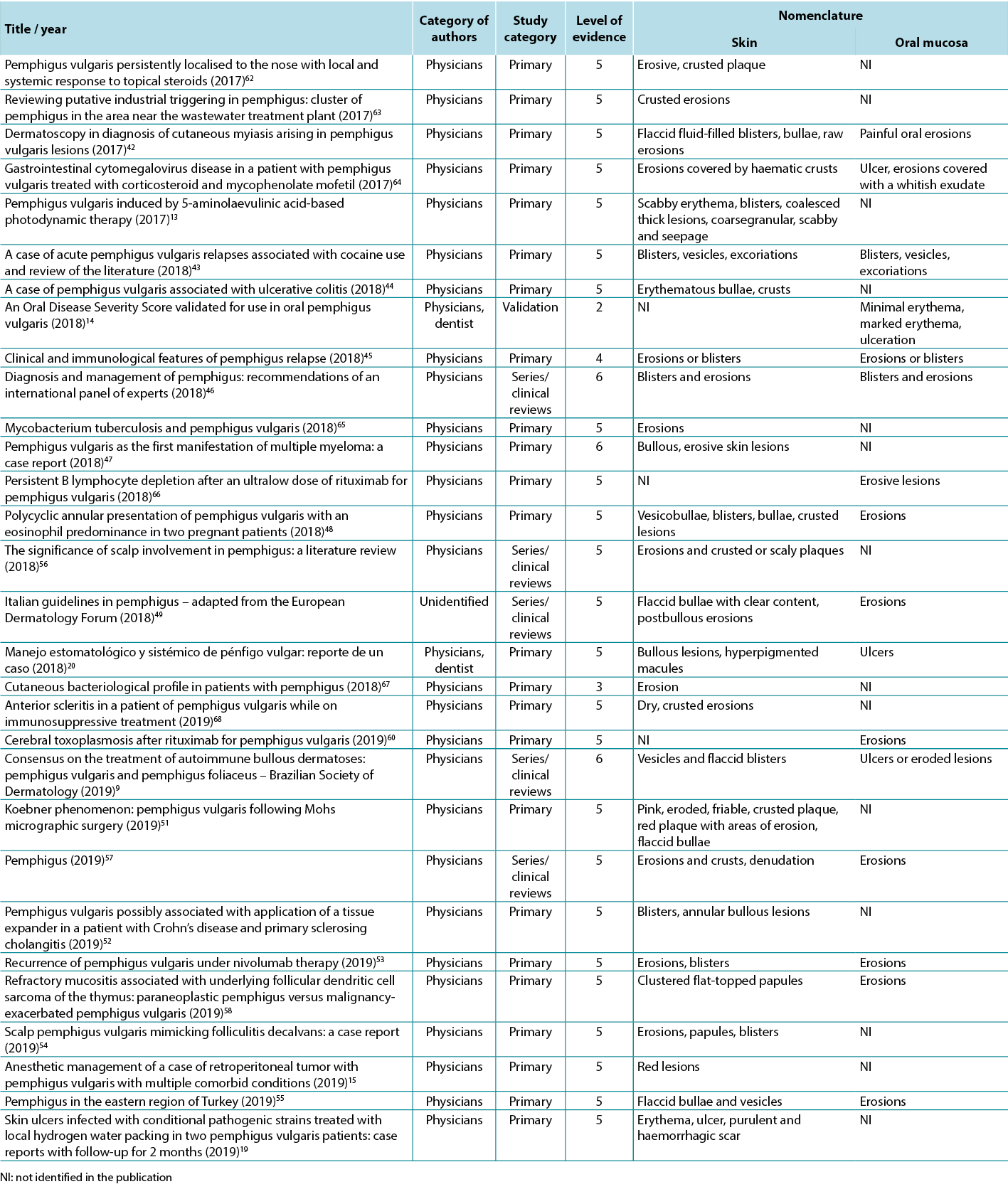

The data analysis for the qualitative studies were reviewed and were systematically categorised, analysed and synthesised, and placed into distinct themes, patterns and relationships using a matrix method. The synthesis of the studies was organised into three axis: (1) characteristics of scientific publications on PV; (2) terminology used to describe cutaneous lesions related to PV (Table 1); and (3) comparison of terminologies used in studies and dermatological description of skin lesions.

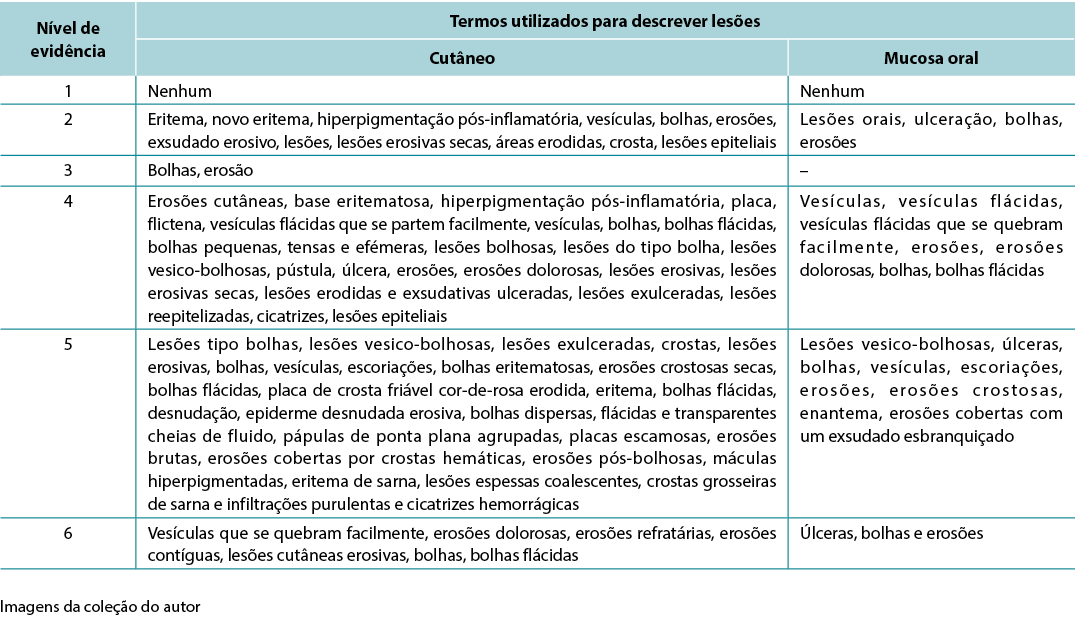

Table 1. Terms identified grouped by level of evidence of the studies

Ethical and legal aspects

The research project was submitted and approved by the Research Ethics Committee / UNIFESP: 0450/2015 and followed the ethical and legal precepts of research with human beings according to Resolution 196/96 of the National Health Council.

Results

The initial search identified 2934 articles; 356 articles were included from review of the titles. After review of the abstracts, another 258 papers were not suitable for review since they did not meet the inclusion criteria; specifically, the excluded papers did not address PV and lesion assessment. A total of 58 articles were then selected for the study after exclusion of 40 duplicates. Of the 58 articles, 37 (63.79%) were primary studies, 17 (29.31%) were series/clinical reviews and four (6.90%) were validation studies.

A variety of terms were used in the literature to describe PV-related lesions. These are summarised below.

Primary skin lesions

Flat spots or maculae

The first is flat skin lesions, including colour changes and blood-vascular stains. Nomenclature used were new erythema, erythema, minimal erythema, and marked erythema9–15. Erythema is defined as a red colour resulting from vasodilation that disappears by digital pressure or diascopy. Diascopy is a refinement in which a piece of clear glass or plastic is pressed against the skin while the observer looks directly at the lesion under pressure15,16.

Solid formations / oedematous elevations

Solid formations may include bullae and papulae (small superficial solid elevations of the skin) while oedematous elevations could be cutanaeous lesions, scales or pustulae (defined elevation of the skin containing purulent fluid). These clinical features might be associated with a positive Nikolsky sign17.

Pigment spots

Nomenclature used in this section were post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and hyperpigmented macules5,11,16, 18–20. Hyperchromia is defined as a spot of variable colour, caused by the increase of melanin or deposit of another pigment. The increase in melanin / melanodermic spots has a variable colour from light brown to dark bluish or black16,18.

Liquid content

Nomenclature used here were vesicles, blisters and bullous lesions1,5,9,10,12,13,20–55. Vesicles are defined as of circumscribed elevation, containing clear liquid, up to 1cm in size. The fluid, which is primitively clear (serous), may become cloudy (purulent) or red (haemorrhagic)16,18. A blister is defined as elevation containing clear liquid, greater than 1cm in size. The fluid, which is primitively clear, may become yellowish-red or reddish, forming a purulent or haemorrhagic blister16,18. The term bullous lesions is used to refer to any liquid collections.

Secondary skin lesions

Thickness changes

Nomenclature used here are epithelial lesions, denuded epidermis and scar9–11,13,19,22,35,51,54,56–58. A scar is defined as a flat, salient or depressed lesion, without grooves, pores and hairs, movable, adherent or retractable. It associates atrophy with fibrosis and dyschromia. It results from the repair of destructive process of the skin. It can be: atrophic (thin, pleated, papyraceous); pitted (small holes appear); or hypertrophic (nodular, elevated, vascular, with excessive fibrous proliferation, with a tendency to regress)16,18.

Tissue losses

Nomenclature used are erosions, eroded areas, erosive lesions, crust, ulceration, ulcer, ulcerative lesions, raw erosions and excoriations1,5,9–15,19–21,23–60. Erosion or exulceration is defined as superficial loss that affects only the epidermis. Crust is defined as a concretion of light yellow to greenish or dark red colour which forms in an area of tissue loss. It results from the desiccation of serosity (meliceric), pus (purulent) or blood (haemorrhagic), mixed with epithelial remains16,18.

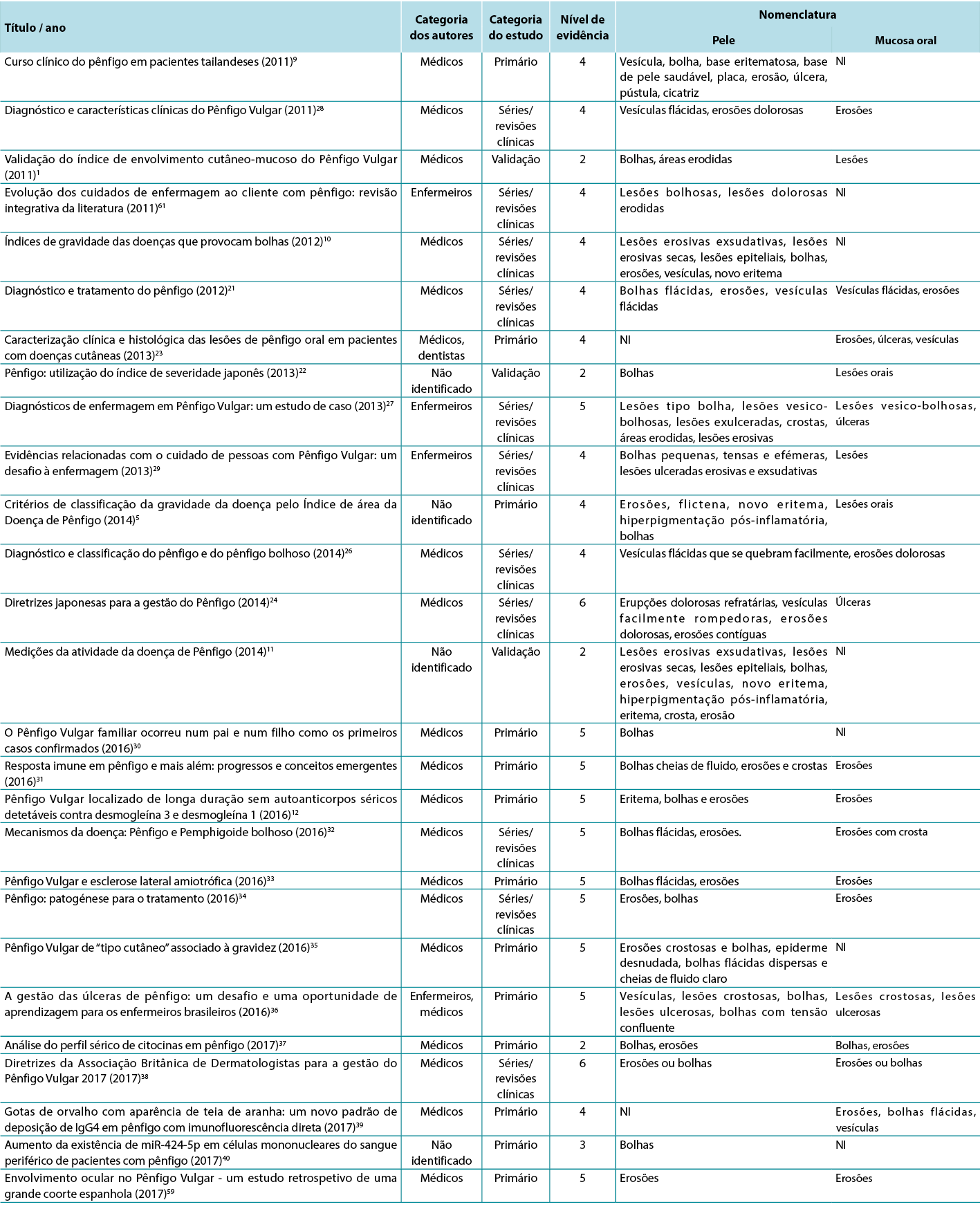

Therefore, in view of the integrative review, it was possible to identify studies describing the dermatological alterations of PV ulcers according to criteria established by dermatological glossaries. In order to illustrate the correlation of the identified terms and their corresponding study, the third analysis correlates the terms identified with the year, author category, study category and level of evidence, shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Terms identified in selected articles

Discussion

As evidenced by the results, studies in this area are scant and nurses have had little contribution. However, this is needed to highlight the consistency demonstrated between the terms used by authors and the terminology of elementary lesions.

To promote excellence in dermatological care it is necessary for nurses and health professionals to develop skills for the evaluation of cutaneous manifestations, especially skin lesions. The skin, as the largest organ of the human body, has protection as one of its numerous functions. Far beyond essentially dermatological affections, it can translate the person’s general condition, signalling the presence of systemic disorders and sometimes presenting manifestations that are recognised as cutaneous markers of certain pathologies. However, the paucity of studies in PV has led to poor description and evaluation of skin lesions in PV. This may result in delayed diagnosis and suboptimal care and treatment6,20,29,36.

In fact, this subject points to the need for further investigation to compose a framework of knowledge based on scientific evidence in this area, so that dermatology nurses may develop an accurate consideration of the assessment of skin manifestations, especially skin ulcers. These professionals publish little on this subject, which corroborates with the lack of formulation of new evidence for their topical care. This lack of evidence makes nursing assistance to these people less secure, since a theoretical framework is essential for evidence-based care given the specificity and complexity of caring for these patients16,25.

The main researchers in this area, Brandão and Santos4,6,25,29, investigate this issue from the point of view of integral care, with a social-poetic approach and a nursing diagnosis that support the comfort and relief of pain among those affected.

Through clinical observation, the authors of this study concluded that traditional topical care generates high rates of hospital stay, pain and discomfort. This clinical observation was the trigger to build evidence of the best evaluation tools and descriptors and base this on the use of topical therapies that optimise the potential of healing by managing cofactors such as pH, thermoregulation, humidity, microbial load and adherence of the dressing25,36.

It can be observed that when the nursing descriptor was used, the literature search resulted in a much smaller number of articles in comparison to those searches without this descriptor. Although dermatological nursing is a recognised specialty in Brazil, the descriptors ‘nursing in dermatology’ or ‘dermatologist nurse’ or ‘dermatological nursing’ do not exist. Therefore, in search of studies, the descriptors ‘nursing’ and ‘nursing assessment’ were used.

Among the nomenclatures used in the different levels of studies, we can observe that all use the dermatological glossary to describe the lesions, with only a small variation with detailed description of the tissue such as exudative erosions. Despite the scarcity of studies written by nurses, it was possible to observe that the terminology used did not differ between professional categories25,29,36.

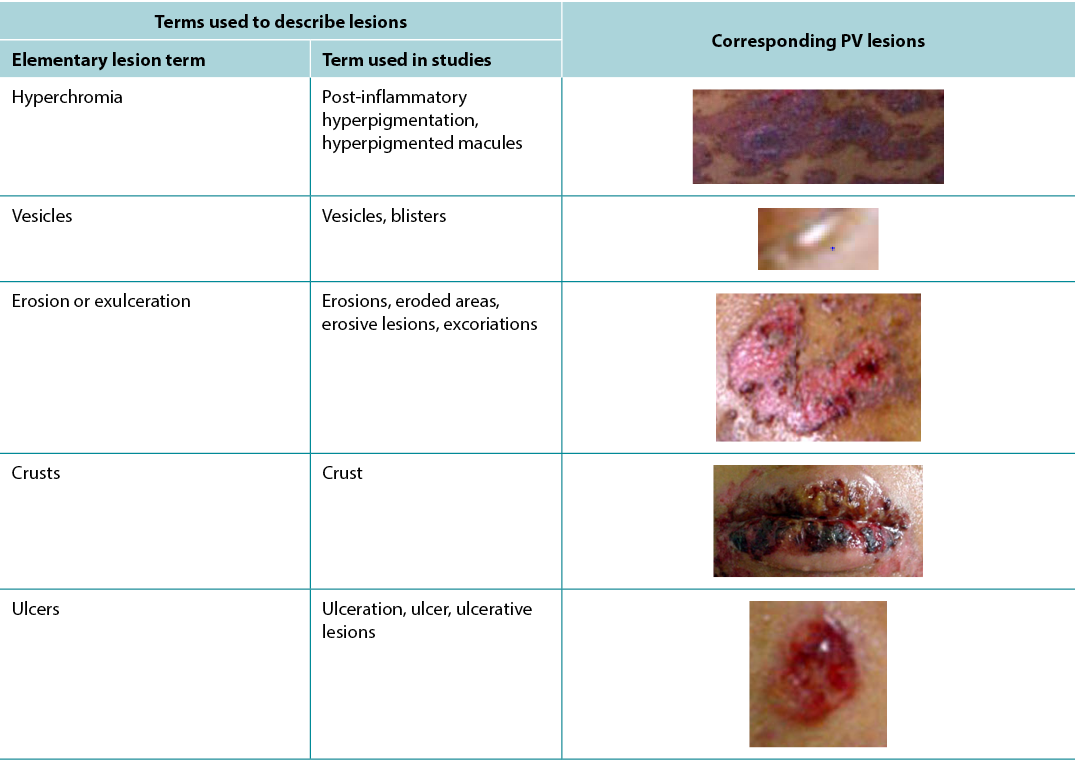

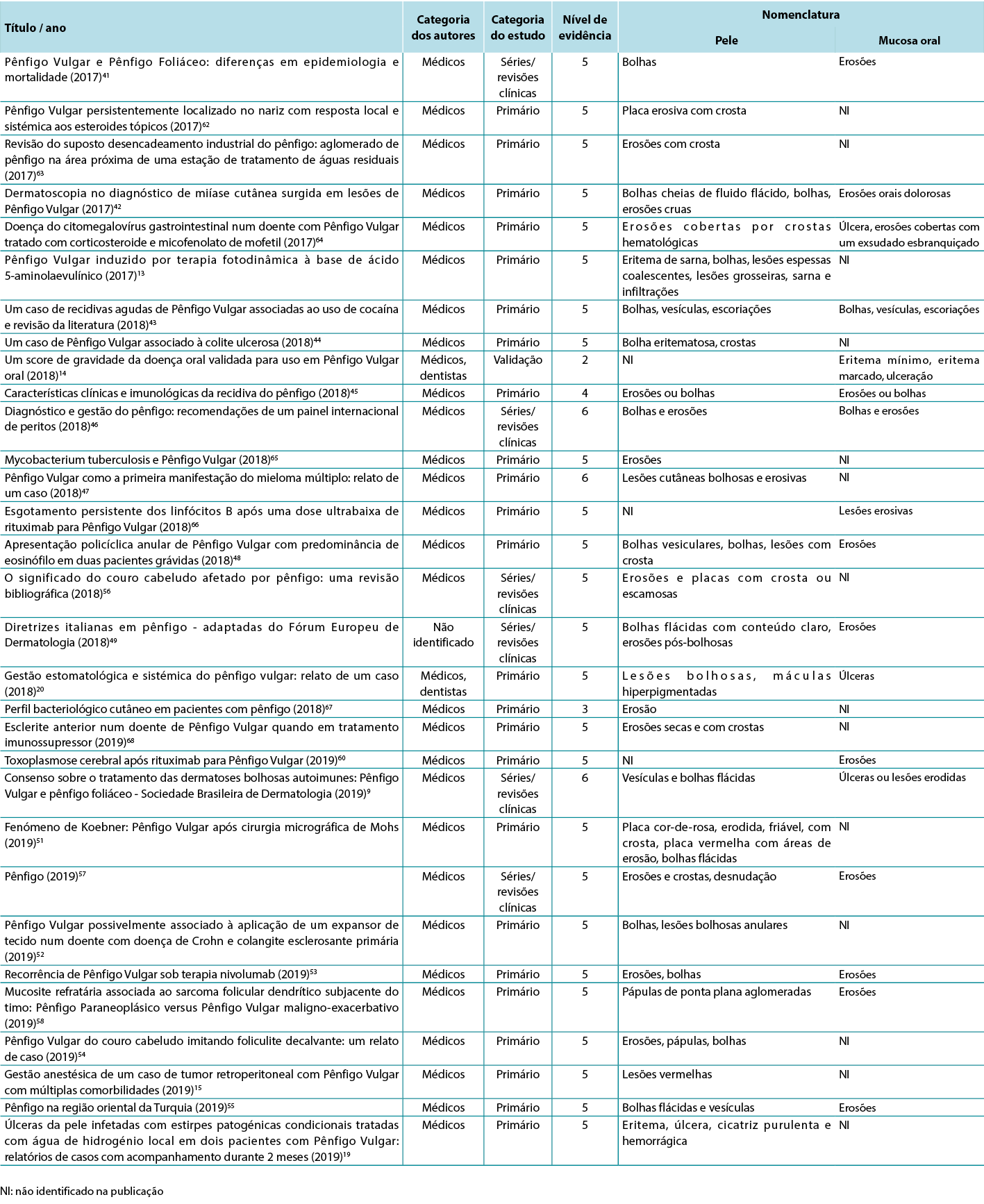

According to Sampaio and Rivitti3, skin lesion classification is like letters of the alphabet; just as letters compose words, through their combination they form morphological signs that allow us to “read” the cutaneous manifestations16,18. As shown in the results, the skin lesions, associated with complementary information, can help in the definition of diagnostic hypotheses, intervention decision and monitoring of healing evolution. The use of clinical descriptors to characterise skin lesions or ulcers standardises this information, making it more understandable for health professionals. In Table 3 examples of PV lesions related to the correspondent elementary skin lesion term are given.

Table 3. Elementary skin lesion terms and corresponding examples of PV lesion

Skin lesions are classified into six groups: colour changes; oedematous elevations; solid formations; liquid formations; thickness changes; and losses and repairs. This classification may be grouped into:

- Primary: flat spots or maculae (colour changes); solid (solid formations); oedematous elevations (rash, oedema); liquid content (liquid formations).

- Secondary: changes in consistency and thickness (changes in thickness); or loss of substance (tissue losses and repairs)16,18.

Diagnoses, interventions and nursing outcomes according to the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA), Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) and Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) for patients with PV were proposed by Pena et al.27. The analysis of the nursing diagnosis ‘impaired skin integrity’ and ‘impaired oral mucous membrane’ made it possible to perceive that the nurse assessment to arrive at this diagnosis does not require a specialised evaluation since the defining characteristics for such diagnoses involve only the rupture of the skin or mucosa, not requiring evaluation of thickness, tissue type or other characteristics assessed in a wound. In the proposed NOC outcome ‘healing’, in which one of the indicators used was granulation tissue, the knowledge about the tissue types that a wound can present is necessary. The proposed NIC intervention ‘wound care’ involves the decision about the intervention to be adopted, presupposing specific knowledge, skills and preparation in this area27. Considering the increasing performance of dermatology nursing as a specialty, these nomenclatures are becoming increasingly familiar to nurses.

As the nomenclature used to describe skin lesions becomes standard, whether secondary to PV or not, the interlocution between professionals tends to become more uniform, avoiding misunderstanding and resulting in safer patient care. However, in wound assessment there is still a great diversity in the terminology used to describe the skin damage, for example: slough and fibrin; wet necrosis and liquefaction necrosis; dry necrosis, ‘scar’ and pressure injury; granulation tissue, extra cellular matrix or viable tissue. This richness of terminologies causes doubt, within professionals consulting the records, often generating interpretations that differ from those of the person who registered them. In order to standardise the register of PV ulcers, we suggest the use of the elementary lesions terms – vesicles, blisters, erosions, ulcers and generalised crusts.

The chronic character and the cutaneous manifestation of PV steal from the patient their right to confidentiality. Frequently, the lesions are associated with contagion, impacting on social and familiar relations, and perpetuating stigma and isolation4. For Brandão, nursing actions become productive as they aim to reach the patient’s holistic balance. Thus there is a constant search for alternatives that attend to the needs of people suffering from changes in skin integrity, and the development of technologies and techniques that promote healing in order to improve their quality of life4,27.

Conclusions

This study compared the terminology used to describe cutaneous ulcers in PV studies with the terminology used in describing elementary lesions. It also demonstrated that the publications authored by physicians were the most common ones, followed by those authored by nurses, and lacked uniformity in the description of the lesions.

This study demonstrated that the skin changes in PV can be classified as primary skin lesions (colour changes and liquid collections) or secondary skin lesions (changes in thickness and tissue loss). In view of the extensive dermatological glossary, lesions secondary to PV can be characterised as vesicles, blisters, erosions, ulcers and generalised crusts to support the practice of nursing in dermatology.

Lastly, it is concluded that studies with a higher level of evidence in this area are necessary in order to determine the best way to evaluate the lesions, as well as the nomenclature to be used for improved nursing care.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

A avaliação de enfermagem de úlceras de Pênfigo Vulgar

Mariana Takahashi Ferreira Costa, Luiza Keiko Matsuka Oyafuso, Mônica Antar Gamba and Kevin Y Woo

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.3.27-37

Resumo

Introdução O Pênfigo Vulgar (PV) é uma dermatose bolhosa auto-imune grave que resulta na formação de bolhas intra-epidérmicas que afetam a pele e as membranas mucosas. Os dados epidemiológicos mostram uma incidência de 0,1-0,5 por 100.000 habitantes por ano e uma mortalidade de quase 5-10%.

Objetivo O objetivo desta revisão integrativa da literatura era o de examinar a classificação/terminologia das úlceras PV de acordo com a descrição das lesões cutâneas.

Método Esta é uma revisão integrativa de estudos primários, revisões de séries/clínicas ou estudos de validação que descrevem ou avaliam as úlceras PV. As estratégias de pesquisa incluíram artigos relevantes que foram publicados no período entre 2011-2019 usando termos como pênfigo, úlcera de pele, dermatologia, diagnóstico, avaliação de enfermagem. Os estudos foram selecionados para análise após aplicação de critérios de elegibilidade e de exclusão por duplicidade.

Resultados A pesquisa inicial resultou em 2.934 publicações; 14 artigos foram elegíveis para análise. A síntese dos estudos foi organizada da seguinte forma - 57,14% séries/revisões clínicas, 50% escritas por médicos, 64,29% nível de evidência 4. A terminologia utilizada para descrever úlceras PV incluía eritema cutâneo/mucoso, novo eritema, hiperpigmentação pós-inflamatória, lesões orais, crostas epiteliais, bolhas, vesículas, erosões, áreas erodidas, lesões exsudativas erosivas, erosão seca.

Conclusões São necessários estudos sobre esta questão com melhores níveis de evidência, a fim de determinar a melhor forma de descrever as lesões utilizando o glossário dermatológico para avaliação de enfermagem.

Introdução

Pênfigo Vulgar (PV) é uma dermatose bolhosa auto-imune grave em que os anticorpos destroem os desmossomas, resultando na formação de bolhas intra-epidérmicas que afetam a pele e as membranas mucosas. O PV ocorre principalmente entre a 4ª e 6ª décadas de vida, afetando homens e mulheres com uma incidência de 0,1-0,5 / 100.000 habitantes / ano e com uma taxa de mortalidade de 5-10%. A distribuição da doença é universal, mas afeta mais frequentemente pessoas de ascendência judaica-3.

Em PV, os auto-anticorpos atuam predominantemente na desmogleína 3 (Dsg3), o que se expressa predominantemente nas camadas mais profundas da epiderme2,3. A identificação da camada em que ocorre a acantólise é um fator que ajuda no diagnóstico de dermatoses bolhosas. Por exemplo, é possível diferenciar o PV do pênfigo foliáceo pelo local onde ocorre a acantólise, uma vez que o pênfigo foliáceo afeta a camada granular enquanto que o PV afeta a camada espinhosa2,3. Estas manifestações envolvem a formação de bolhas, com a consequente ulceração e danos na pele que podem ser devastadores, afetando a interação social e mesmo a perda de emprego4.

O impacto da desfiguração associada à PV na qualidade de vida, autoimagem, dinâmica familiar e social dos pacientes tem sido bem documentado4. Para além do envolvimento cutâneo, a PV pode envolver tecido mucoso na boca, faringe, laringe, passagem nasal e canais auditivos (Figuras 1 & 2). As áreas afetadas pela doença podem comprometer a respiração normal, bem como a capacidade de falar e de comer para manter uma ingestão nutricional adequada2,3.

Figura 1. Lesões cutâneas no tronco

Figura 2. Lesões da mucosa oral

A classificação da PV tem sido objeto de estudos nos últimos anos. O Índice de Compromisso de Pele e Mucosa em Pênfigo Vulgar usa quatro parâmetros diferentes para pontuar o estado clínico da doença: (a) o número de bolhas ou áreas erodidas; (b) o tamanho das bolhas ou áreas erodidas; (c) evidência do signo Nikolsky (quando deslizar o dedo firmemente com pressão sobre a pele separa a epiderme de aspeto normal, produzindo uma erosão); e (d) envolvimento mucoso e septicemia. A pontuação total pode variar entre 0-100 e os pacientes são classificados da seguinte forma: Classe I pontuação 0-30; Classe II 35-65; Classe III 70-100, o que significa que quanto mais alta for a pontuação, mais crítico será o estado1.

Os instrumentos de classificação de Pênfigo, o Índice de área da Doença de Pênfigo (PDAI) e a Escala Japonesa de gravidade da Doença de Pênfigo (JPDSS), foram comparados por Shimizu et al.5. O PDAI mede o envolvimento da pele e mucosas pelo tamanho e número de bolhas em cada região anatómica e a pontuação varia entre 0-263. JPDSS utiliza parâmetros para a pontuação: (I) a razão entre a área de pele afetada e a área de superfície do corpo; (II) a presença ou ausência do fenómeno do sinal de Nikolsky; (III) o número de bolhas recentemente desenvolvidas por dia; (IV) a presença ou ausência de lesões orais; e (V) a quantidade de anticorpos de pênfigo. Cada parâmetro tem uma pontuação que varia entre 0-3. No estudo de Shimizu et al.5, os resultados mostram que o PDAI reflete com maior precisão a gravidade da doença. Os autores propõem, portanto, a utilização de índices para orientar um tratamento uniforme de acordo com os critérios de classificação. A corticoterapia é o tratamento escolhido e pode ser associada aos imunossupressores se não houver melhoria com a corticoterapia de forma isolada2,3.

Embora seja considerada uma doença relativamente rara, é necessário que as enfermeiras reconheçam as lesões cutâneas associadas à PV e comuniquem os resultados apropriados, a fim de ajudar os pacientes a procurar tratamento precoce, avaliar a progressão da doença e monitorizar as respostas ao tratamento6. O objetivo desta revisão integrativa é a de descrever a taxonomia para a descrição e avaliação pelos enfermeiros das alterações cutâneas relacionadas com a PV.

Método

Esta revisão integrativa foi conduzida para identificar, analisar e sintetizar estudos que, neste tema, utilizam métodos qualitativos, quantitativos e mistos7. Escolhemos o método descrito por Mendes7 para orientar a revisão, a qual consistiu em seis etapas: (1) formulação da pergunta orientadora; (2) estabelecimento de critérios para inclusão e exclusão de estudos e de recolha de dados (pesquisa na literatura); (3) categorização dos estudos; (4) avaliação dos estudos incluídos na revisão; (5) análise e interpretação dos dados; e (6) síntese dos conhecimentos evidenciados nos artigos analisados (apresentação dos resultados)7.

Formulação da pergunta orientadora

A questão da investigação foi - Como estão descritas na literatura as lesões que caracterizam a PV em termos da sua definição e classificação?

Estabelecimento de critérios para a inclusão e exclusão de estudos e recolha de dados

A literatura médica e de enfermagem foi pesquisada entre 2011-2019, em conjunto com um bibliotecário, para ajudar a responder à questão da investigação. As pesquisas incluíram Web of Science, LILACS, EMBASE, SCOPUS, PUBMED, BVS, CINAHL e COCHRANE com critérios específicos de inclusão e exclusão. Para identificar publicações relevantes, as bases de dados foram pesquisadas usando os seguintes termos-chave - dermatologia, pênfigo, úlcera de pele, diagnóstico e avaliação de enfermagem. Os critérios de inclusão incluíam artigos publicados em inglês, espanhol e português, literatura revista por pares e documentos de consenso; as datas de publicação foram de 1 de Janeiro de 2011 a 31 de Dezembro de 2019. Comentários e editoriais foram excluídos.

Categorização dos estudos

Estudos selecionados foram então categorizados de acordo com os seis níveis de evidência8:

• Nível 1: evidências de meta-análise de estudos múltiplos controlados e de estudos aleatórios.

• Nível 2: evidências de estudos individuais com desenho experimental.

• Nível 3: evidências de estudos quase-experimentais, séries cronológicas ou casos-controles.

• Nível 4: evidências de estudos descritivos (abordagem não experimental ou qualitativa).

• Nível 5: evidências de relatórios de casos/experiência.

• Nível 6: evidências baseadas em pareceres de comités de peritos, incluindo interpretações de informações não baseadas na investigação, pareceres regulamentares ou jurídicos.

Avaliação dos estudos incluídos na revisão

Esta etapa incluiu a avaliação dos estudos, bem como a extração de dados. Foi utilizado um formulário normalizado de recolha de dados para extrair a seguinte informação: autores; categoria profissional dos autores; título do artigo; revista; ano de publicação; nível de evidência; objetivos; desenho metodológico; detalhe da amostragem; síntese de informação; avaliação/classificação de úlceras de pele em pênfigo; metodologia utilizada para validar o instrumento; descrição do instrumento; terminologia utilizada para caracterizar as úlceras; resultados e conclusões.

Análise e interpretação dos dados

A fase de avaliação dos dados incluiu a avaliação da qualidade das fontes primárias utilizando uma abordagem metodológica específica para determinar a qualidade dessa mesma fonte. Os dados foram avaliados e codificados de acordo com dois critérios - o rigor metodológico e a relevância para o tema da avaliação da pele. Os estudos foram analisados e o rigor avaliado numa pontuação de 0-4. A relevância para o tópico também foi pontuada e indicada, sendo que 1 indicava que não tinha qualquer relevância para o tópico e 2 indicava que o artigo era relevante.

Síntese / apresentação dos resultados

A análise dos dados para os estudos qualitativos foi revista e foi sistematicamente categorizada, analisada e sintetizada e colocada em distintos temas, padrões e relações utilizando um método matricial. A síntese dos estudos foi organizada em três eixos: (1) características das publicações científicas sobre PV; (2) terminologia utilizada para descrever lesões cutâneas relacionadas com a PV (Quadro 1); e (3) comparação das terminologias utilizadas em estudos e descrição dermatológica de lesões cutâneas.

Quadro 1. Termos identificados agrupados por nível de evidência dos estudos

Aspetos éticos e jurídicos

O projeto de investigação foi submetido e aprovado pelo Comité de Ética na Investigação / UNIFESP: 0450/2015 seguiu os preceitos éticos e legais da investigação com seres humanos de acordo com a Resolução 196/96 do Conselho Nacional de Saúde.

Resultados

A pesquisa inicial identificou 2934 artigos; foram incluídos 356 artigos a partir da revisão dos títulos. Após revisão dos resumos, outros 258 trabalhos não foram adequados para revisão, uma vez que não cumpriam os critérios de inclusão; especificamente, os trabalhos excluídos não abordaram a PV e a avaliação das lesões. Um total de 58 artigos foram então selecionados para o estudo, após a exclusão de 40 duplicados. Dos 58 artigos, 37 (63,79%) eram estudos primários, 17 (29,31%) eram revisões séries/clínicas e quatro (6,90%) eram estudos de validação.

Foram utilizados vários termos na literatura para descrever lesões relacionadas com a PV. Estes estão resumidos abaixo.

Lesões cutâneas primárias

Manchas planas ou máculas

A primeira são lesões cutâneas planas, incluindo alterações de cor e manchas vasculares sanguíneas. As nomenclaturas utilizadas foram eritema novo, eritema, eritema mínimo e eritema marcado9-15. O eritema é definido como uma cor vermelha resultante da vasodilatação que desaparece por pressão digital ou diascopia. Diascopia é um refinamento em que um pedaço de vidro ou plástico transparente é pressionado contra a pele enquanto o observador olha diretamente para a lesão sob pressão15,16.

Formações sólidas / elevações edematosas

As formações sólidas podem incluir bolhas e pápulas (pequenas elevações sólidas superficiais da pele) enquanto as elevações edematosas podem ser lesões cutâneas, escamas ou pústulas (elevação definida da pele contendo fluido purulento). Estas características clínicas podem estar associadas a um sinal positivo de Nikolsky17.

Manchas de pigmentação

A nomenclatura utilizada nesta secção foi a hiperpigmentação pós-inflamatória e as máculas hiperpigmentadas5,11,16, 18-20. A hipercromia é definida como uma mancha de cor variável, causada pelo aumento de melanina ou depósito de outro pigmento. O aumento de melanina / manchas melanodérmicas tem uma cor variável, desde castanho claro a azulado escuro ou preto16,18.

Conteúdo líquido

A nomenclatura aqui utilizada foi vesículas, bolhas e lesões bolhosas1,5,9,10,12,13,20-55. As vesículas são definidas como sendo de elevação circunscrita, contendo líquido transparente, até 1cm de tamanho. O fluido, que é primitivamente claro (seroso), pode tornar-se nublado (purulento) ou vermelho (hemorrágico)16,18. Uma bolha é definida como uma elevação contendo líquido transparente, de tamanho superior a 1cm. O fluido, que é primitivamente claro, pode tornar-se vermelho-amarelado ou avermelhado, formando uma bolha purulenta ou hemorrágica16,18. O termo lesões bolhosas é utilizado para referência a qualquer coleção de líquidos.

Lesões cutâneas secundárias

Mudanças de espessura

A nomenclatura aqui utilizada foi lesões epiteliais, epiderme desnudada e cicatriz9-11,13,19,22,35,51,54,56-58. Uma cicatriz é definida como uma lesão plana, saliente ou deprimida, sem sulcos, poros e pelos, móvel, aderente ou retráctil. Associa a atrofia à fibrose e à discromia. Resulta da reparação do processo destrutivo da pele. Pode ser: atrófica (fina, pregueada, papirácea); sem caroço (aparecem pequenos orifícios); ou hipertrófica (nodular, elevada, vascular, com proliferação fibrosa excessiva, com tendência a regredir)16,18.

Perdas de tecidos

A nomenclatura utilizada foi erosões, áreas erodidas, lesões erosivas, crosta, ulceração, úlcera, lesões ulcerosas, erosões brutas e escoriações1,5,9–15,19–21,23–60. A erosão ou exulceração é definida como a perda superficial que afeta apenas a epiderme. A crosta é definida como uma concreção de cor amarelo claro a esverdeado ou vermelho escuro que se forma numa área de perda de tecido. Resulta da dessecação da serosidade (melicérico), pus (purulento) ou sangue (hemorrágico), misturado com restos epiteliais16,18.

Assim, tendo em vista a revisão integrativa, foi possível identificar estudos descrevendo as alterações dermatológicas das úlceras PV de acordo com critérios estabelecidos pelos glossários dermatológicos. A fim de ilustrar a correlação dos termos identificados e o respetivo estudo, a terceira análise correlaciona os termos identificados com o ano, categoria do autor, categoria do estudo e nível de evidência, mostrados no Quadro 2.

Quadro 2. Termos identificados em artigos selecionados

Discussão

Como é evidenciado pelos resultados, os estudos nesta área são escassos e os enfermeiros têm tido pouca contribuição. Contudo, isto é necessário para realçar a coerência demonstrada entre os termos utilizados pelos autores e a terminologia das lesões elementares.

Para promover a excelência nos cuidados dermatológicos é necessário que enfermeiros e profissionais de saúde desenvolvam competências para a avaliação de manifestações cutâneas, especialmente lesões cutâneas. A pele, como o maior órgão do corpo humano, tem a proteção como uma das suas numerosas funções. Muito além das afecções essencialmente dermatológicos, pode traduzir o estado geral da pessoa, assinalando a presença de perturbações sistémicas e apresentando por vezes manifestações que são reconhecidas como marcadores cutâneos de certas patologias. No entanto, a escassez de estudos em PV levou a uma deficiente descrição e avaliação das lesões cutâneas em PV. Isto pode resultar num diagnóstico atrasado e em cuidados e tratamentos não otimizados6,20,29,36.

De facto, este assunto aponta para a necessidade de mais investigação para compor um quadro de conhecimentos baseado em evidências científicas nesta área, de modo que os enfermeiros de dermatologia possam desenvolver um conhecimento preciso da avaliação das manifestações cutâneas, especialmente das úlceras cutâneas. Estes profissionais pouco publicam sobre este assunto, o que corrobora a falta de formulação de novas evidências para os seus cuidados sobre este tópico. Esta falta de evidências torna a assistência de enfermagem a estas pessoas menos segura, uma vez que um quadro teórico é essencial para os cuidados baseados em evidências, dada a especificidade e complexidade dos cuidados a prestar a estes pacientes16,25.

Os principais investigadores nesta área, Brandão e Santos4,6,25,29, investigam esta questão do ponto de vista dos cuidados integrais, com uma abordagem social-poética e um diagnóstico de enfermagem que apoia o conforto e o alívio da dor entre as pessoas afetadas.

Através da observação clínica, os autores deste estudo concluíram que os cuidados tópicos tradicionais geram altas taxas de estadia hospitalar, dor e desconforto. Esta observação clínica foi o gatilho para a construção de evidências das melhores ferramentas e descritores de avaliação, baseando-se na utilização de terapias tópicas que otimizam o potencial de cura através da gestão de cofatores tais como pH, termorregulação, humidade, carga microbiana e aderência do penso25,36.

Pode-se observar que quando o critério enfermagem foi utilizado, a pesquisa bibliográfica resultou num número muito menor de artigos, em comparação com aquelas pesquisas sem este critério. Embora a enfermagem dermatológica seja uma especialidade reconhecida no Brasil, os descritores 'enfermagem em dermatologia' ou 'enfermeiro dermatologista' ou 'enfermagem dermatológica' não existem. Portanto, na procura de estudos, foram utilizados os descritores 'enfermagem' e 'avaliação de enfermagem'.

Entre as nomenclaturas utilizadas nos diferentes níveis de estudos, podemos observar que todas utilizam o glossário dermatológico para descrever as lesões, com apenas uma pequena variação com descrição detalhada do tecido, como as erosões exsudativas. Apesar da escassez de estudos escritos por enfermeiros, foi possível observar que a terminologia utilizada não diferia entre as categorias profissionais25,29,36.

Segundo Sampaio e Rivitti3, a classificação das lesões cutâneas é como as letras do alfabeto; tal como as letras compõem palavras, esta classificação através da sua combinação forma sinais morfológicos que nos permitem "ler" as manifestações cutâneas16,18. Como demonstrado nos resultados, as lesões cutâneas, associadas a informações complementares, podem ajudar na definição de hipóteses de diagnóstico, decisão de intervenção e monitorização da evolução da cicatrização. A utilização de descritores clínicos para caracterizar lesões ou úlceras cutâneas normaliza esta informação, tornando-a mais compreensível para os profissionais de saúde. No Quadro 3 são dados exemplos de lesões PV relacionadas com o termo lesão cutânea elementar correspondente.

Quadro 3. Termos de lesão cutânea elementar e exemplos correspondentes de lesão PV

As lesões cutâneas são classificadas em seis grupos: alterações de cor; elevações edematosas; formações sólidas; formações líquidas; alterações de espessura; e perdas e reparações. Esta classificação pode ser agrupada em:

- Primário: manchas planas ou máculas (mudanças de cor); sólido (formações sólidas); elevações edematosas (erupção cutânea, edema); conteúdo líquido (formações líquidas).

- Secundário: alterações na consistência e espessura (alterações na espessura); ou perda de substância (perdas e reparações de tecidos)16,18.

Diagnósticos, intervenções e resultados de enfermagem de acordo com a North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA), Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) e Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) para pacientes com PV foram propostos por Pena et al.27. A análise do diagnóstico de enfermagem "integridade cutânea prejudicada" e "membrana mucosa oral prejudicada" permitiu perceber que a avaliação do enfermeiro para chegar a este diagnóstico não requer uma avaliação especializada, uma vez que as características que definem tais diagnósticos envolvem apenas a rutura da pele ou mucosa, não requerendo uma avaliação da espessura, tipo de tecido ou outras características avaliadas numa ferida. No resultado proposto do NOC, "cicatrização", no qual um dos indicadores utilizados foi o tecido de granulação, o conhecimento sobre os tipos de tecido que uma ferida pode apresentar é necessário. A intervenção NIC proposta 'tratamento de feridas' envolve a decisão sobre a intervenção a adotar, pressupondo conhecimentos específicos, competências e preparação nesta área27. Considerando o crescente desempenho da enfermagem dermatológica como especialidade, estas nomenclaturas estão a tornar-se cada vez mais familiares aos enfermeiros.

À medida que a nomenclatura utilizada para descrever lesões cutâneas se padroniza, secundária ou não à PV, a interlocução entre profissionais tende a tornar-se mais uniforme, evitando mal-entendidos e resultando em cuidados mais seguros ao paciente. Contudo, na avaliação de feridas existe ainda uma grande diversidade na terminologia utilizada para descrever os danos na pele, por exemplo: descamação e fibrina; necrose húmida e necrose de liquefação; necrose seca, "cicatriz" e lesão por pressão; tecido de granulação, matriz extracelular ou tecido viável. Esta riqueza de terminologias causa dúvidas, no seio dos profissionais que consultam as fichas, gerando muitas vezes interpretações diferentes das da pessoa que as registou. A fim de padronizar o registo de úlceras PV, sugerimos a utilização dos termos elementares em lesões - vesículas, bolhas, erosões, úlceras e crostas generalizadas.

O carácter crónico e a manifestação cutânea da PV roubam ao paciente o seu direito à confidencialidade. Frequentemente, as lesões estão associadas ao contágio, com impacto nas relações sociais e familiares e perpetuando o estigma e o isolamento4. Para Brandão, as ações de enfermagem tornam-se produtivas, uma vez que visam alcançar o equilíbrio holístico do paciente. Assim, há uma procura constante de alternativas que atendam às necessidades das pessoas que sofrem de alterações na integridade da pele e o desenvolvimento de tecnologias e técnicas que promovam a cura, a fim de melhorar a sua qualidade de vida4,27.

Conclusões

Este estudo comparou a terminologia utilizada para descrever úlceras cutâneas em estudos PV com a terminologia utilizada para descrever lesões elementares. Também demonstrou que as publicações da autoria de médicos eram as mais comuns, seguidas pelas de autoria de enfermeiros, não apresentando uniformidade na descrição das lesões.

Este estudo demonstrou que as alterações cutâneas em PV podem ser classificadas como lesões cutâneas primárias (alterações de cor e acumulação de líquidos) ou secundárias (alterações na espessura e perda de tecidos). Tendo em conta o extenso glossário dermatológico, as lesões secundárias à PV podem ser caracterizadas como vesículas, bolhas, erosões, úlceras e crostas generalizadas para apoiar a prática da enfermagem em dermatologia.

Finalmente, conclui-se que são necessários estudos com um nível de evidência mais elevado nesta área para determinar a melhor forma de avaliar as lesões, bem como a nomenclatura a ser utilizada de forma a melhorar os cuidados de enfermagem.

Conflitos de interesses

Os autores declaram não haver conflitos de interesses.

Financiamento

Os autores não receberam qualquer financiamento para este resumo de evidências.

Author(s)

Mariana Takahashi Ferreira Costa*

Master’s Degree student, School of Nursing, Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil

Nurse member of Group for Prevention and Treatment of Wounds, de Emílio Ribas Infectology Institute, State Secretary of Health, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Email marianatakahashicosta@hotmail.com

Luiza Keiko Matsuka Oyafuso

Supervisor of Health Technical Team, Emílio Ribas Infectology Institute, State Secretary of Health, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Assistant Professor, ABC University Foundation

Mônica Antar Gamba

Associate Professor, School of Nursing, Federal University of São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Coordinator of the Dermatology Nursing Specialization Course, Mentor Professor at the Nursing Postgraduation Program

Kevin Y Woo PhD RN FAPWCA

Assistant Professor, School of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

Adjunct Research Professor, MClSc program, School of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, Western University

Wound Care Consultant, West Park Healthcare Centre

Clinical Web Editor, Advances in Skin and Wound Care

* Corresponding author

References

- Souza SR, Azulay-Abulafia L, Nascimento LV. Validation of the cutaneomucosal involvement index of pemphigus vulgaris for the clinical evaluation of patients with pemphigus vulgaris. An Bras Dermatol 2011;86(2):284–91.

- Hanauer L, Azulay-Abulafia L, Azulay DR, Azulay RD. Buloses. In: Azulay RD. Dermatology. 7th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2017. p. 242–245.

- Sampaio SAP, Rivitti EA. Dermatology. 4th ed. São Paulo: Artes Médicas; 2018. p.300–316.

- Brandão ES, Santos I, Lanzillotti RS. Reduction of pain in clients with autoimmune bullous dermatoses: evaluation by fuzzy logic. Online Braz J Nurs 2016 Dec; 15(4):675–682. Available from: http://www.objnursing.uff.br/index.php/nursing/article/view/546

- Shimizu T, Takebayashi T, Sato Y, Niizeki H, Aoyama Y, et al. Grading criteria for disease severity by Pemphigus Disease Area Index. J Dermatol 2014;41:969–973.

- Brandão ES, Santos I, Lanzillotti RS. Nursing care to comfort people with immunobullous dermatoses: evaluation by fuzzy logic. Rev Enferm UERJ, Rio de Janeiro 2018; 26:e32877.

- Mendes KD, Silveira RC, Galvão CM. Integrative literature review: a research method to incorporate evidence in health care and nursing. Text & Cont Enferm 2008;17(4):758–64.

- Galvão CM, Sawada NO, Mendes IAC. The search for the best evidence. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2003;37:43–50.

- Kulthanan K, Chularojanamontri L, Tuchinda P, AL Sirikudta W, Pinkaew S. Clinical course of pemphigus in Thai patients. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2011;29:161–8.

- Daniel BS, Hertl M, Werth VP, Eming R, Murrell DF. Severity score indexes for blistering diseases. Clin Dermatol 2012;30:108–113.

- Rahbar Z, Daneshpazhooh M, Mirshams-Shahshahani M, Esmaili N, Heidari K, et al. Pemphigus disease activity measurements: pemphigus disease area index, autoimmune bullous skin disorder intensity score and pemphigus vulgaris activity score. JAMA Dermatol 2014;150(3):266–72.

- Yoshifuku A, Fujii K, Kawahira H, Katsue H, Baba A, et al. Long-lasting localized pemphigus vulgaris without detectable serum autoantibodies against desmoglein 3 and desmoglein 1. Indian J Dermatol 2016;61(4):427.

- Zhou Q, Wang P, Zhang L, Wang B, Shi L, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris induced by 5-aminolaevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2017;156–158.

- Ormond M, McParland H, Donaldson ANA, Andiappan M, Cook RJ, Escudier M, Shirlaw PJ. An Oral Disease Severity Score validated for use in oral pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 2018;179(4):872–881.

- Mishra S, Joshi S. Anesthetic management of a case of retroperitoneal tumor with pemphigus vulgaris with multiple comorbid conditions. Egyptian J Anaesthes 2016;32(1):151–153.

- Rivitti EA. Dermatologia. 4th ed. São Paulo: Artes Médicas; 2018. p. 109–118.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Ellebrecht CT, Takahashi H, Yamagami J, Zillikens D, Payne AS, Amagai M. Pemphigus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017 May 11;3:17026. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.26. PMID: 28492232; PMCID: PMC5901732.

- Azulay RD. Dermatology. 7th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2017. p. 52–64.

- Yang F, Chen Z, Chen SA, Zhu Q, Wang L, et al. Skin ulcers infected with conditional pathogenic strains treated with local hydrogen water packing in two pemphigus vulgaris patients: case reports with follow-up for 2 months. Dermatol Ther 2019 Sep;32(5):e13027. doi:10.1111/dth.13027. Epub 2019 Jul 28. PMID: 31323168.

- Carmona Lorduy M, Porto Puerta I, Berrocal Torres S, Camacho Chaljub F. Manejo estomatológico y sistémico de pénfigo vulgar: reporte de un caso. Rev Cienc Salud 2018;16(2):357–367.

- Tsuruta D, Ishii N, Hashimoto T. Diagnosis and treatment of pemphigus. Immunother 2012;4(7):735.

- Benchikhi H, Nani S, Baybay H, et al. Pemphigus: use of the Japanese severity index in 56 Moroccan patients. Pan Afr Med J 2013;16:96.

- Suliman NM, Åstrøm AN, Ali RW, et al. Clinical and histological characterization of oral pemphigus lesions in patients with skin diseases: a cross sectional study from Sudan. BMC Oral Health 2013;13(1):66.

- Amagai M, Tanikawa A, Shimizu T, et al. Japanese guidelines for the management of pemphigus. J Dermatol 2014;41: 471–486.

- Brandão ES, Santos I, Lanzillotti RS, Ferreira AM, Gamba MA, et al. Nursing diagnoses in patients with immune-bullous dermatosis. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2016;24:e2766. doi:10.1590/1518-8345.0424.

- Kershenovich R, Hodak E, Mimouni D. Diagnosis and classification of pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:477–81.

- Pena SB, Guimarães HC, Bassoli SR, et al. Nursing diagnoses in pemphigus vulgaris: a case study. Int J Nurs Know 2013;24(3):176–179.

- Venugopal SS, Murrell DF. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus vulgaris. Dermatol Clin 2011;29:373–380.

- Brandão ES, Santos I. Evidences related to the care of people with pemphigus vulgaris: a challenge to nursing. Online Braz J Nurs 2013 Sept;12(1):162–77. Available from: http://www.objnursing.uff.br/index.php/nursing/article/view/3674/html.

- Eskiocak AH, Ozkesici B, Uzun S. Familial pemphigus vulgaris occurred in a father and son as the first confirmed cases. Case Rep Dermatol Med 2016;1653507. doi:10.1155/2016/1653507. Epub 2016 Jun 15. PMID: 27403352; PMCID: PMC4925942.

- Di Zenzo G, Amber KT, Sayar BS, Müller EJ, Borradori L. Immune response in pemphigus and beyond: progresses and emerging concepts. Semin Immunopathol 2016 Jan;38(1):57–74.

- Hammers CM, Stanley JR. Mechanisms of disease: pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. Annu Rev Pathol 2016;11:175–197.

- Mokhtari F, Matin M, Rajati F. Pemphigus vulgaris and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Res Med Sci 2016 Oct18;21:82.

- DiMarco, C. Pemphigus: pathogenesis to treatment. R I Med J 2016;99(12):28–31.

- Rangel, J. Pregnancy-associated ‘cutaneous type’ pemphigus vulgaris. Perm J 2016;20(1):e101-e102. doi:10.7812/TPP/15-059.

- Costa MTF, Oyafuso LKM, Costa IG, Gamba MA, Woo KY. The management of pemphigus ulcers: a challenge and learning opportunity for Brazilian nurses. WCET J 2016;36(2):14–20.

- Lee SH, Hong WJ, Kim SC. Analysis of serum cytokine profile in pemphigus. Ann Dermatol 2017;29(4), 438–445.

- Harman KE, Brown D, Exton LS, Groves RW, Hampton PJ, Mohd Mustapa MF, Buckley DA. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris 2017. Br J Dermatol 2017;177(5):1170–1201.

- Dmochowski M, Gornowicz-Porowska J, Bowszyc-Dmochowska M. Dew drops on spider web appearance: a newly named pattern of IgG4 deposition in pemphigus with direct immunofluorescence. Postȩpy Dermatol Alergol 2017;34(4):295.

- Wang M, Liang L, Li L, Han K, Li Q, Peng Y, Zeng K. Increased miR-424-5p expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with pemphigus. Mol Med Rep 2017;15(6):3479–3484.

- Kridin K, Zelber-Sagi S, Bergman R. Pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus: differences in epidemiology and mortality. Acta Derm Venereol 2017;97(8–9):1095–1099.

- Vinay K, Handa S, Khurana S, Agrawal S, De D. Dermatoscopy in diagnosis of cutaneous myiasis arising in pemphigus vulgaris lesions. Indian J Dermatol 2017;62(4):440.

- Jiménez-Zarazúa O, Guzmán-Ramírez A, Vélez-Ramírez LN, López-García JA, Casimiro-Guzmán L, Mondragón JD. A case of acute pemphigus vulgaris relapses associated with cocaine use and review of the literature. Dermatol Ther 2018;8(4):653–663.

- Seo JW, Park J, Lee J, Kim MY, Choi HJ, Jeong HJ, Kim WK. A case of pemphigus vulgaris associated with ulcerative colitis. Intest Res 2018;16(1):147.

- Ujiie I, Ujiie H, Iwata H, Shimizu H. Clinical and immunological features of pemphigus relapse. Br J Dermatol 2019 Jun;180(6):1498–1505. doi:10.1111/bjd.17591. Epub 2019 Mar 6. PMID: 30585310.

- Murrell D, Peña S, Joly P, Marinovic B, Hashimoto T, et al. Diagnosis and management of pemphigus: recommendations by an international panel of experts. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020 Mar;82(3):575–585.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.021. Epub 2018 Feb 10. PMID: 29438767; PMCID: PMC7313440.

- Sendrasoa FA, Ranaivo IM, Rakotoarisaona MF, Raharolahy O, Razanakoto NH, Andrianarison M, Rabenja FR. Pemphigus vulgaris as the first manifestation of multiple myeloma: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2018;12(1):255.

- Küçükoğlu R, Sun GP, Kılıç S. Polycyclic annular presentation of pemphigus vulgaris with an eosinophil predominance in two pregnant patients. Dermatol Online 2018;24(10).

- Feliciani C, Cozzani E, Marzano AV, Caproni M, Di Zenzo G, Calzavara-Pinton P, Lora V. Italian guidelines in pemphigus-adapted from the European Dermatology Forum (EDF) and European Academy of Dermatology and Venerology (EADV). G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2018;153(5):599–608.

- Porro A M, Hans Filho G, Santi CG. Consensus on the treatment of autoimmune bullous dermatoses: pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus: Brazilian Society of Dermatology. An Bras Dermatol 2019;94(2):20–32.

- Hattier G, Beggs S, Sahu J, Trufant J, Jones E. Koebner phenomenon: pemphigus vulgaris following Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Online J 2019;25(1).

- Badavanis G, Pasmatzi E, Kapranos N, Monastirli A, Constantinou P, Psaras G, Tsambaos D. Pemphigus vulgaris possibly associated with application of a tissue expander in a patient with Crohn’s disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 2019;28(4):173–176.

- Krammer S, Krammer C, Salzer S, Bağcı IS, French LE, Hartmann D. Recurrence of pemphigus vulgaris under nivolumab therapy. Front Med 2019;6:262.

- Bosseila M, Nabarawy EA, Latif MA, Doss S, ElKalioby M, Saleh MA. Scalp pemphigus vulgaris mimicking folliculitis decalvans: a case report. Dermatol Pract Concept 2019;9(3):215–17.

- Yavuz IH, Yavuz GO, Bayram I, Bilgili SG. Pemphigus in the eastern region of Turkey. Postȩpy Dermatol Alergol 2019;36(4):455–60.

- Sar-Pomian M, Rudnicka L, Olszewska M. The significance of scalp involvement in pemphigus: a literature review. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018: 6154397. doi:10,1155/2018/6154397

- Schmidt E, Kasperkiewic M, Joly P. Pemphigus. Lancet 2019;394(10201):882–894.

- Streifel AM, Wessman LL, Schultz BJ, Miller D, Pearson DR. Refractory mucositis associated with underlying follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the thymus: paraneoplastic pemphigus versus malignancy-exacerbated pemphigus vulgaris. JAAD Case Rep 2019;5(11):933.

- España A, Iranzo P, Herrero‐González J, Mascaro Jr JM, Suárez R. Ocular involvement in pemphigus vulgaris: a retrospective study of a large Spanish cohort. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2017;15(4):396–403.

- Lee EB, Ayoubi N, Albayram M, Kariyawasam V, Motaparthi K. Cerebral toxoplasmosis after rituximab for pemphigus vulgaris. JAAD Case Rep 2019;6(1):37–41. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.10.015. PMID: 31909136; PMCID: PMC6938870.

- Brandão E, Santos I, Carvalho M, Pereira SK. Nursing care evolution to the client with pemphigus: integrative literature review. Revista Enfermagem 2011;19:479–484.

- Zhang C, Goldscheider I, Ruzicka T, Sardy M. Pemphigus vulgaris persistently localized to the nose with local and systemic response to topical steroids. Acta Derm Venereol 2017;97(8–9):1136–1137.

- Pietkiewicz P, Gornowicz-Porowska J, Bartkiewicz P, Bowszyc-Dmochowska M, Dmochowski M. Reviewing putative industrial triggering in pemphigus: cluster of pemphigus in the area near the wastewater treatment plant. Postȩpy Dermatol Alergol 2017;34(3):185.

- Oliveira LB, Maruta CW, Miyamoto D, Salvadori FA, Santi CG, Aoki V, Duarte-Neto AN. Gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus disease in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris treated with corticosteroid and mycophenolate mofetil. Autops Case Reps 2017;7(1):23.

- Osipowicz K, Kowalewski C, Woźniak K. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and pemphigus vulgaris. Postȩpy Dermatol Alergol 2018;35(5):532.

- Lazzarotto A, Ferranti M, Meneguzzo A, Sacco G, Alaibac M. Persistent B lymphocyte depletion after an ultralow dose of rituximab for pemphigus vulgaris. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2018;28(5):347.

- Kiran KC, Madhukara J, Abraham A, Muralidharan S. Cutaneous bacteriological profile in patients with pemphigus. Indian J Dermatol 2018;63(4):301.

- Dube M, Takkar B, Asati D, Jain S. Anterior scleritis in a patient of pemphigus vulgaris while on immunosuppressive treatment. Indian J Dermatol 2019;64(6):499–500.