Volume 43 Number 1

Fact-finding survey of pressure and shear force at the heel using a three-axis tactile sensor

Yoko Murooka and Hidemi Nemoto Ishii

Keywords heel pressure injury, decompression, shear force, elevating the head of the bed

For referencing Murooka Y and Ishii HN. Fact-finding survey of pressure and shear force at the heel using a three-axis tactile sensor. WCET® Journal 2023;43(1):20-27

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.1.20-27

Submitted 28 March 2022

Accepted 31 August 2022

Abstract

Aims We investigated changes in pressure and shear force at the heel caused by elevating the head of the bed and after offloading pressure from the heel.

Methods Data on heel pressure and shear force were collected from 26 healthy individuals aged >30 years using a three-axis tactile sensor at each angle formed as the participants’ upper bodies were raised from a supine position. Data after pressure release of either the left or right foot were collected and compared.

Results The participants’ mean age was 45.1 (±11.1) years. Pressure and anteroposterior shear force on the heel increased with elevation. These increases were especially prominent when the angle of elevation was 30˚. In the subsequent 45˚ and 60˚ tilts, body pressure and shear force increased slightly but not significantly. Pressure and shear force were released by elevating the lower extremity each time the head of the bed was elevated. However, further elevations resulted in increased pressure and shear force, particularly lateral shear force. Pressure and shear force did not change significantly when the lower limbs were elevated.

Conclusion The recommended elevation of the bed head to no more than 30˚ yielded major changes. Elevating the leg relieved the heel of continuous pressure and shear force while increasing pressure and lateral shear force. Although leg elevation is an aspect of daily nursing care, it is important to investigate such nursing interventions using objective data.

Introduction

In addition to the relationship between pressure intensity and time, it is clear that frictional and shear forces occur as external forces to the living body. Shear forces obstruct blood flow in the tissue, resulting in tissue ischemia1. In Japan, pressure injuries tend to develop frequently in bedridden older adults with bony prominences. They are especially susceptible to friction and shear forces due to dryness and reduced elasticity of the skin2,3. Therefore, regular repositioning is recommended for reducing pressure and shear force on the skin4.

Preventing pressure injuries requires not only systemic reduction of body pressure but also local depressurisation and reduction of shear force. When the head of a patient’s bed is elevated, the sacrum and coccyx are subjected to severe pressure and shear force, with particular changes in pressure and shear force reported in the sacral region5. In clinical practice, these problems are addressed via depressurisation, which includes pressure redistribution devices and providing daily nursing care. Two such forms of nursing care for depressurisation when a patient’s bed is elevated or lowered are senuki (literally ‘back omission’) and ashinuki (literally ‘leg omission’). Senuki involves the caregiver lifting the patient’s upper body and inserting their hand between the bed and the patient’s back to separate the body from the bed when it is elevated, thereby eliminating the friction and shear force between the patient’s skin and their bedclothes. Ashinuki involves the caregiver elevating the patient’s legs to eliminate the shear force that would otherwise occur from the hip to the posterior surface of the thigh and heel when the bed is elevated or lowered6.

When a bed is elevated, factors such as the concentration of pressure in the buttocks and the sliding down of the body create shear force. Therefore, when elevating a patient’s bed, nurses provide various forms of care such as elevating the legs first, positioning the patient in multiple methods, such as inserting a cushion under their knees to prevent slippage, and elevating the patient’s upper body7–9. However, these nursing interventions were reported in studies that examined the sacrum; few studies have examined changes in pressure or shear force on the heel10,11.

In the supine position, the heel is subjected to continuous pressure, making it vulnerable to tissue injury and pressure injuries. Pressure injuries in the heel are reported to account for one-fourth of all pressure injuries in American hospitals and nursing homes12–15. The effects of bed elevation and other factors make the heel susceptible to friction16. To reduce this friction, preventive dressings are applied17.

The present study examined the pressure and shear force on the heel using a three-axis tactile sensor. Additionally, the aim was to confirm changes in the pressure and shear force on the heel after elevating the heads of patients’ beds, followed by elevating the patients’ lower limbs.

Research Methods

Study design

A quasi-experimental study.

Selection of the participants and period of study

Healthy volunteers aged >30 years were recruited from the researchers’ universities and hospitals. The participants’ number of clinical experiences did not matter in this study design. Posters for research cooperation were displayed on a bulletin board at the facilities to call for participation. The primary author made verbal and e-mail announcements for the same, and used documents to explain the research specifications to individuals who wished to participate. Individuals signed a consent form to confirm participation.

Inclusion criteria required that participants had no wounds on their heels. Temporary redness was considered reactive hyperaemia and such participants were included.

Sample size

When G*Power18 was used to analyse the sample size with an effect size of 0.8, α of 0.05, and a statistical power of 0.8, the sample size was calculated to be n=15. Due to the possibility of an insufficient measurement effect in some participants, we set the sample size as 20. The target number of 20 participants was set to 15 to account for dropouts during data collection. However, no participant met the exclusion criteria and all were included.

Data collection

Data were collected between October 2018 and March 2019.

Measurement environment

Commonly used bedding was selected for the measurements. However, for the convenience of reproducibility, no pillows were used. Other equipment included:

- Electric bed: Paramount bed KA-5000 (4-split type) (Paramount Bed Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

- Base mattress: Everfit KE-521Q (Paramount Bed Corporation, Tokyo, Japan); 10cm thick static mattress.

- Bed sheet: plain woven cotton sheet. The sheets were tucked in when the beds were made.

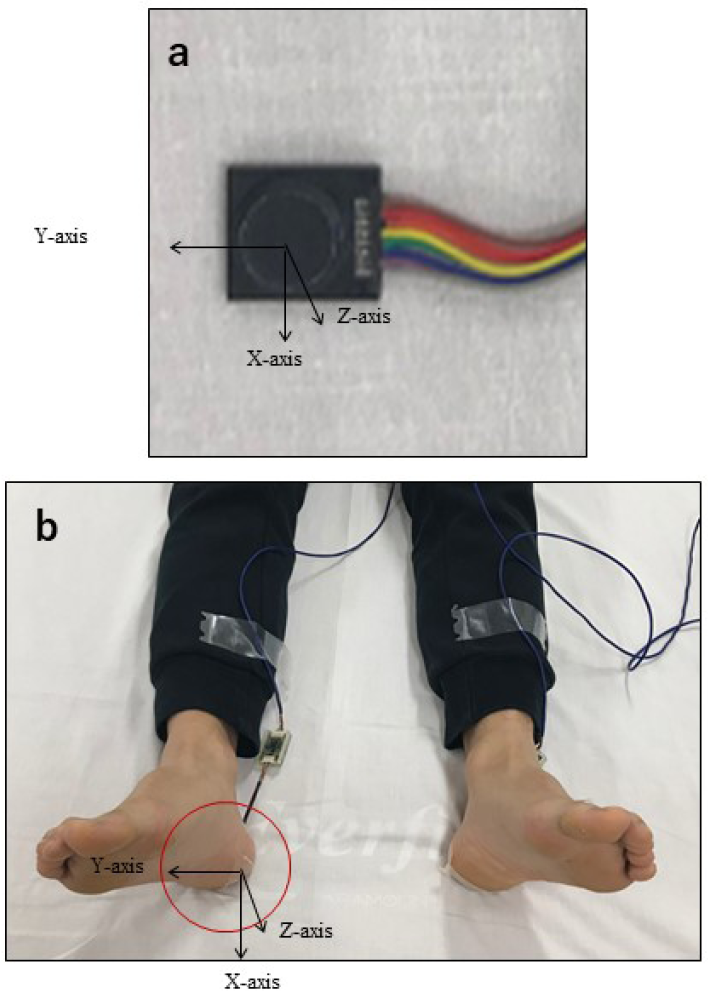

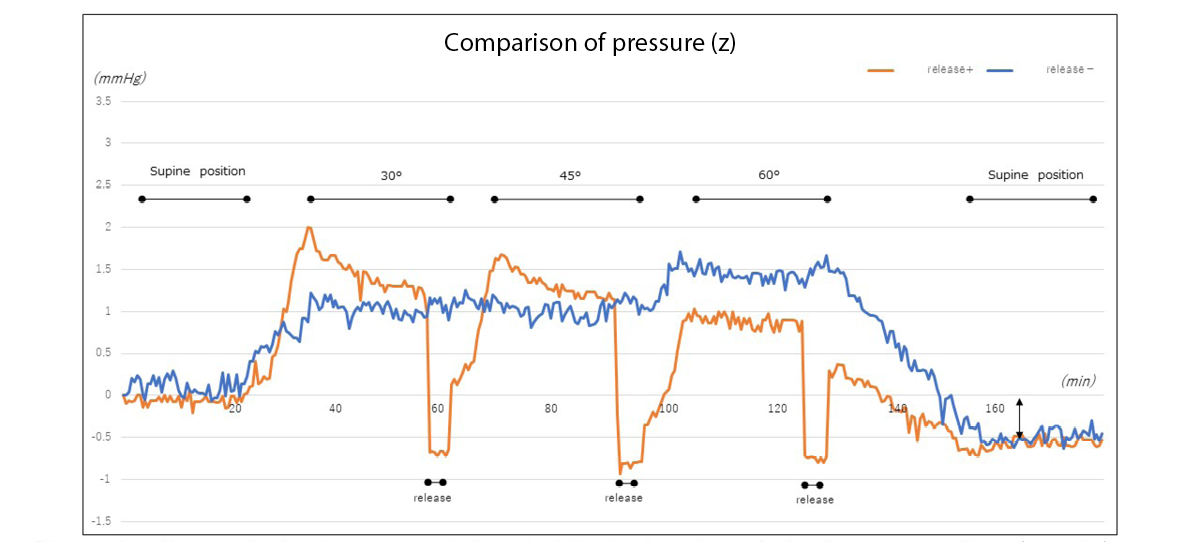

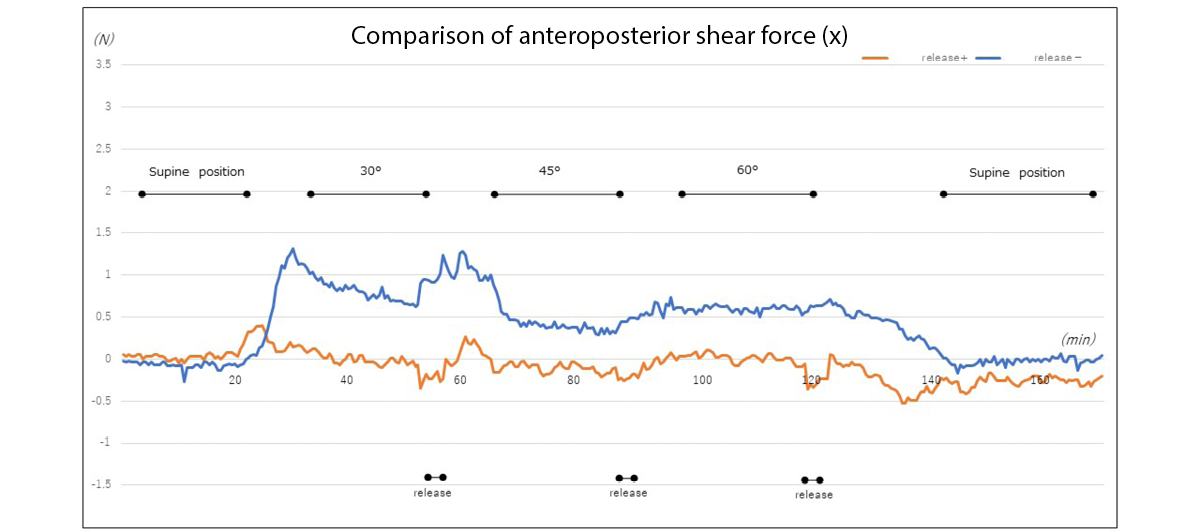

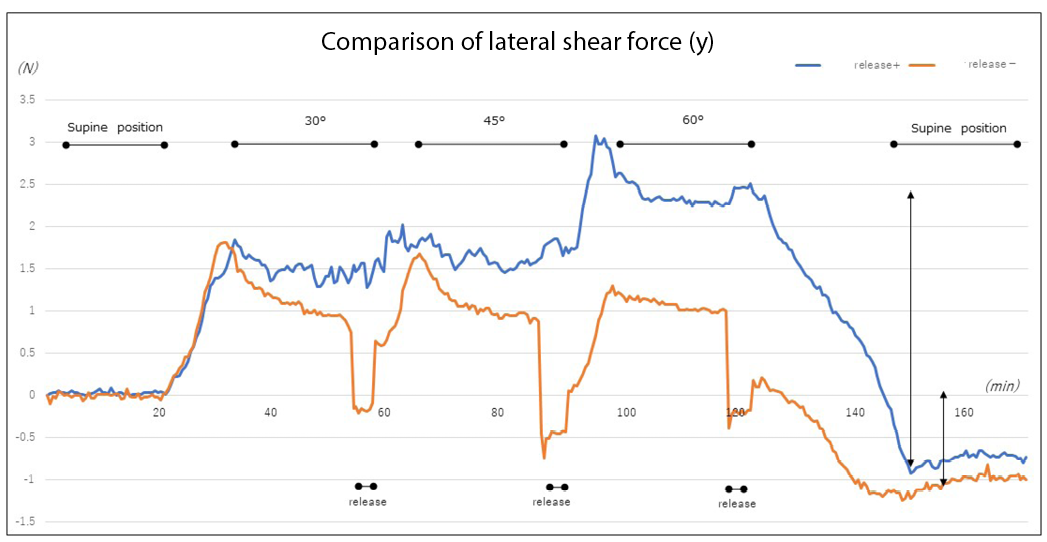

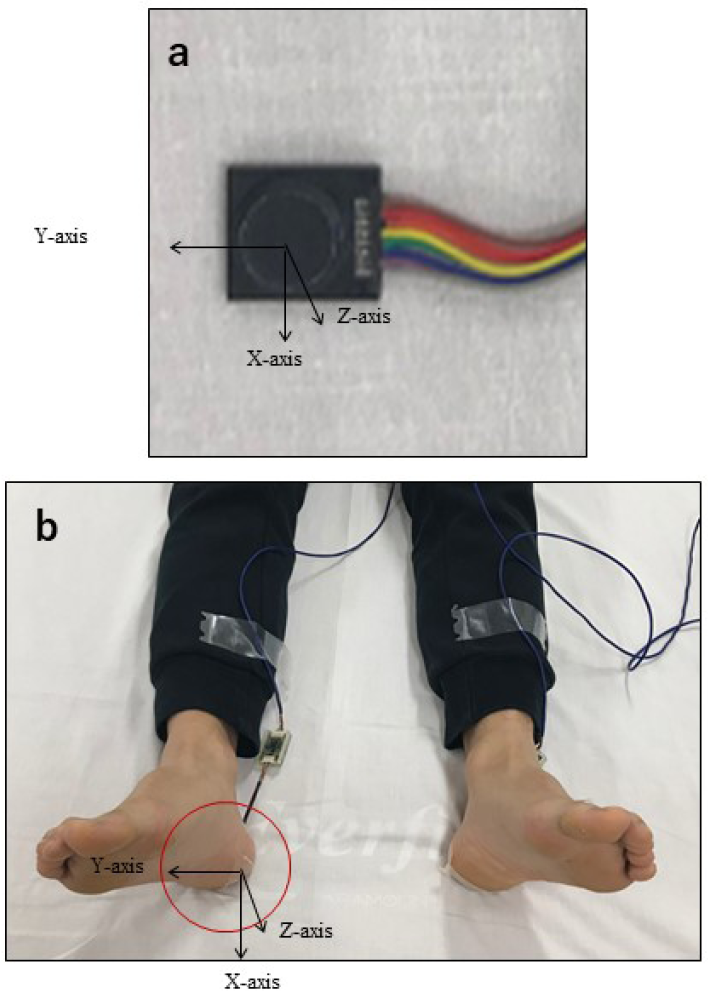

- Measuring device: Three-axis tactile sensor (ShokacChip™T08, Touchence Inc., Tokyo, Japan) 9mm × 9mm × 5mm. The x-, y- and z-axes of the three-axis sensor were set according to pressure, anteroposterior shear force, and lateral shear force, respectively (Figures 1a & b).

Figure 1. A tri-axial tactile sensor was attached to the skin contact area between the heel and the bed and was covered with a dressing. Three directions were measured – anteroposterior shear force (x-axis), lateral shear force (y-axis), and pressure (z-axis)

Measurement procedure

Two experiments were conducted. Experiment 1 measured the pressure and shear force on the heel. Experiment 2 measured the changes in heel pressure and shear force with and without lower limb elevation.

Experiment 1: Changes in heel pressure and shear force upon elevating the head of the bed

The participants slightly opened their lower limbs in a relaxed state and lay in a supine position with their anterior superior iliac spine aligned to the bending point of the bed. The three-axis sensor was applied to the central point of where the left or right heel touched the bed; the film dressing was applied from above (Figures 1a & b). The left or right heel was selected randomly, and the following series of data were collected:

1. After confirming that the participant’s body was still, data for the heel were collected over a 20-second period with the bed in a supine position.

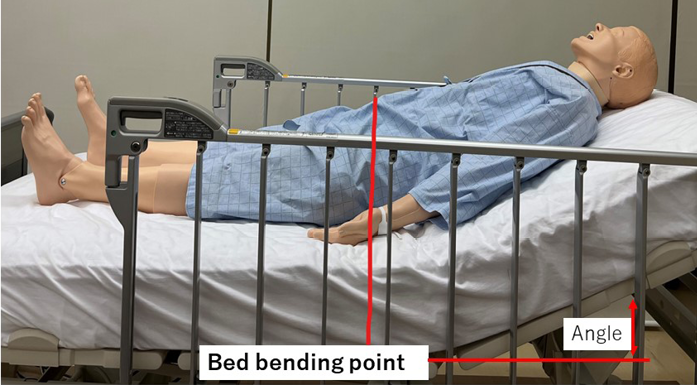

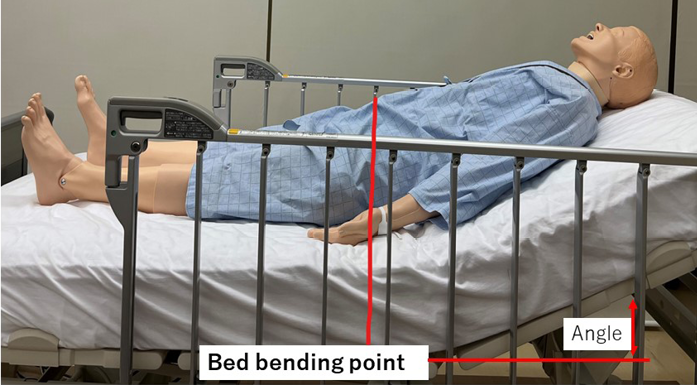

2. After 20 seconds, the participant’s upper body was elevated from the bending point of the bed to a 30˚ angle measured with a goniometer (Figure 2).

3. After the participant’s upper body was elevated, data for the heel were collected while the patient lay still for 20 seconds.

4. The participant’s upper body was then elevated to 45˚ and data were collected in the same manner.

5. After the data collection for the 60˚ elevation, the bed was lowered to a supine position and data were measured for 20 seconds, concluding the experiment.

Experiment 2: Changes in heel pressure and shear force with and without lower limb elevation

As in Experiment 1, the left or right lower limb was selected randomly, and the data collection steps 1−3 in Experiment 1 were repeated. In Experiment 2, the following interventions were carried out from that state.

4. After 20 seconds, either the participant’s left or right knee and ankle were held, lifted up from the hip, and kept still in that position for 5 seconds (Figure 3).

5. After the lower limb was lowered, it was immediately elevated to a 45˚ angle and data were collected for the heel while the participant remained still for 20 seconds.

6. Similar to Step 5 in Experiment 1, after the lower limb was lowered and the head of the bed was elevated to 60˚, the same measurement was performed.

7. Finally, the head of the bed was lowered to a supine position, data were collected for 20 seconds, and the experiment was concluded.

The researcher, a certified expert nurse in wound, ostomy, and continence, conducted Experiments 1 and 2 in this study.

Figure 2. Lying in bed (at the time of elevating the head of the bed)

Figure 3. Lifting the lower limbs

Data analysis

Data were analysed by estimating the average of the observation points at 18 seconds without considering the seconds before and after; the influence of the anteroposterior movement data of the 20 seconds measured for each angle of elevation was also taken into account. Calculations were made by averaging the observation points without the seconds before and after. At the start of the measurement, the initial data value was calibrated to zero and measured twice. The data obtained from the sensors were analysed along the x-axis (anteroposterior shear force), y-axis (lateral shear force), and z-axis (pressure). The pressure and shear force, with and without offloading pressure from the heel at each angle, were analysed using dedicated data software and two-way ANOVA was performed. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 for Windows (IBM Corp. Armonk, N.Y., USA), and the significance level was set at 5%.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Jikei University School of Medicine, Tokyo (9212). The participants were informed of the study orally and in writing, including instructions for the study. The participants’ health status was always observed during the data measurement. They were informed that the procedure would be stopped if they experienced distress. After data collection, we looked for any adverse conditions, such as skin indentation caused by the sensor being applied to the subject’s heel or epidermal peeling caused by the application of the dressing material.

Results

Subject attributes

The study was conducted with 26 participants (11 men and 15 women) with a mean age of 45.1 (±11.1) years and mean BMI of 22.2 (±3.2). No participant met the exclusion criteria, and no adverse events occurred.

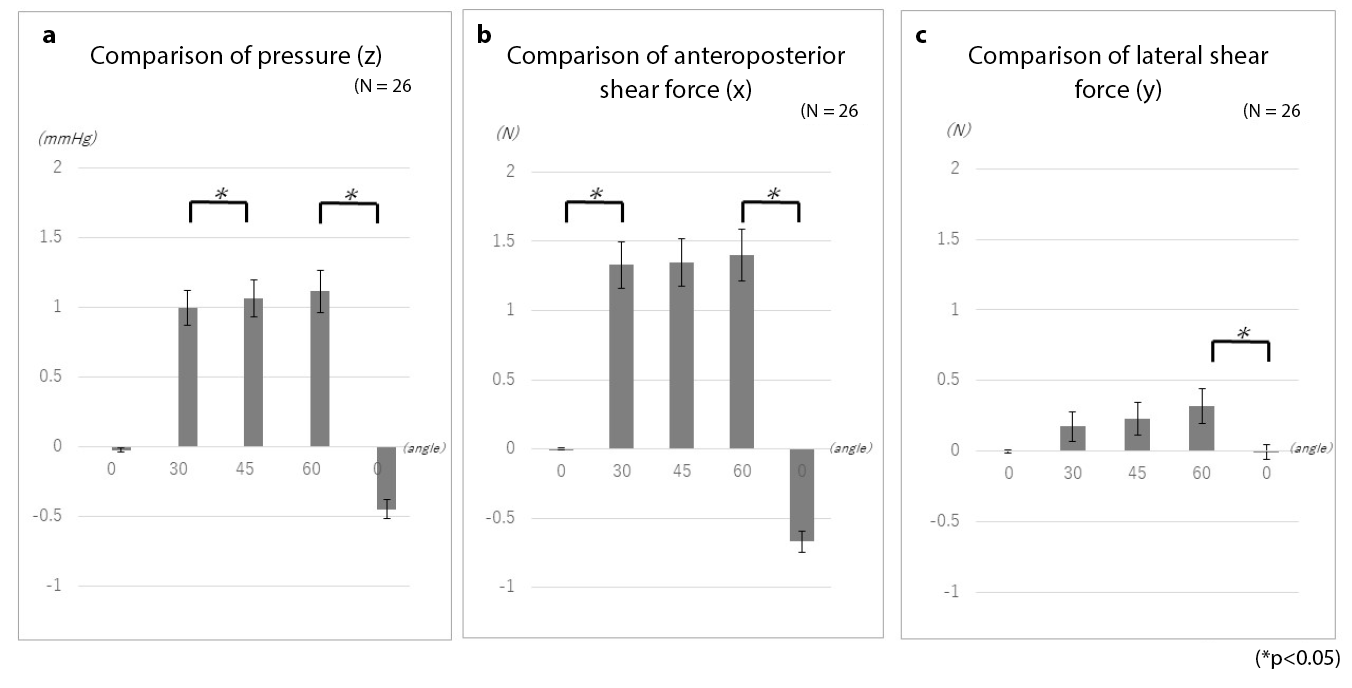

Experiment 1: Changes in heel pressure and shear force upon elevating the head of the bed

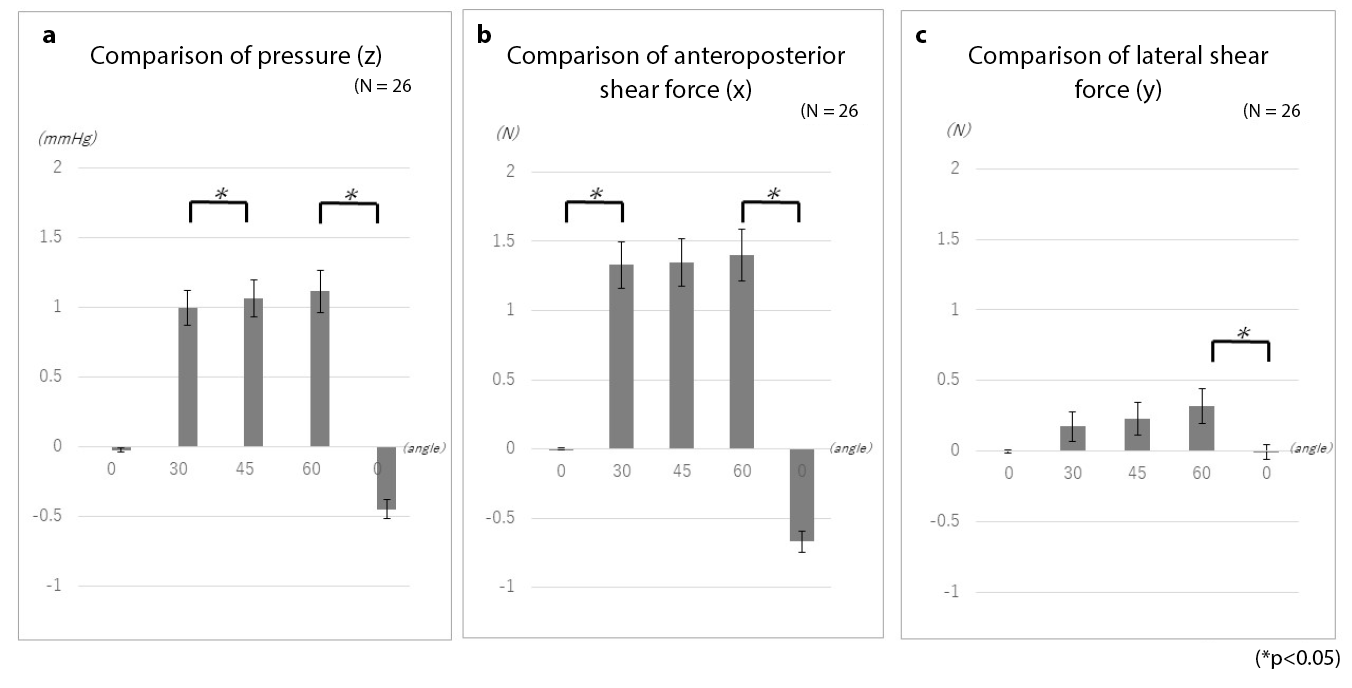

The change in pressure at the heel tended to increase and maintain its value as the head of the bed was raised (Figure 4a). In particular, the pressure increased significantly when the head of the bed was raised from the supine position to 30˚. Subsequently, the pressure values were maintained for the elevation angles of 45˚ and 60˚; no significant increase was observed. However, a significant difference was observed when the angle was changed from 60˚ to the supine position. The pressure initially dropped, but did not return to the starting pressure, which further decreased.

The shear force in the front–back direction tended to increase with the elevation angle. Similar to the pressure values found, the value increased significantly at the 30˚ angle of elevation, and a significant difference was observed. After 45˚, the anteroposterior shear force was maintained but did not increase significantly when the angle was raised from the supine position to 60˚. However, when the angle was changed from 60˚ to the supine position, shear force in the opposite direction was added and a significant difference was observed (Figure 4b).

Although the lateral shear force increased as the head of the bed was elevated, it did not change as greatly as the anteroposterior shear force. A significant difference was observed when the bed was lowered from a 60˚ angle to a supine position. However, the large changes that occurred in the anteroposterior shear force did not occur in the case of lateral shear force (Figure 4c).

Figure 4. Changes in heel pressure and shear force while elevating the head of the bed

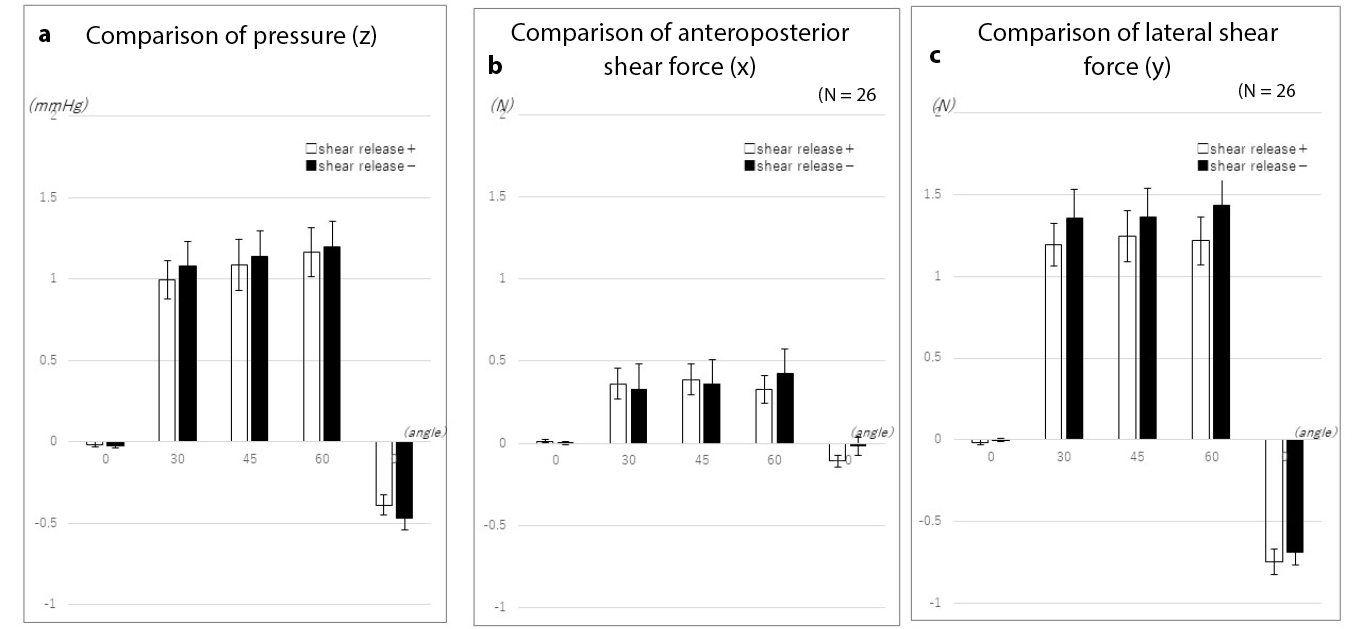

Experiment 2: Changes in heel pressure and shear force with and without lower limb elevation

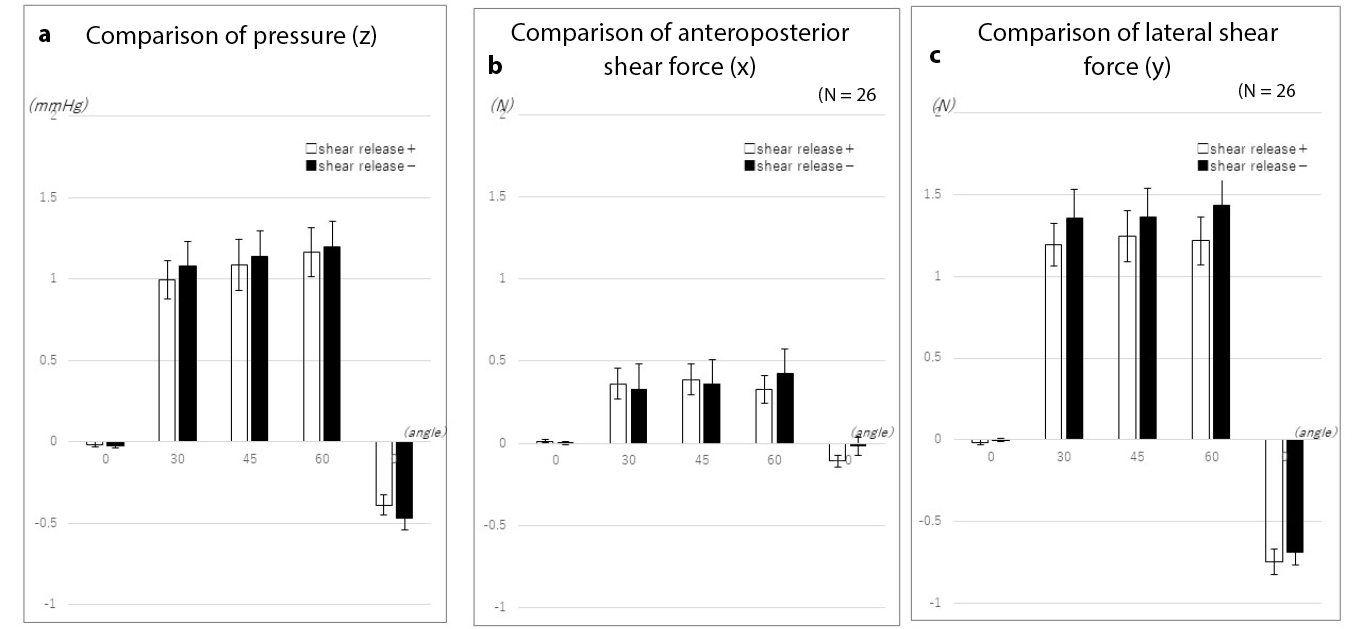

Examinations of the changes in pressure with and without elevation of the lower limbs showed no significant differences in pressure, anteroposterior shear force, or lateral shear force (Figure 5). However, as with the measurements taken with simple elevation of the head of the bed, even when pressure and shear force were offloaded, elevating the head of the bed led to the reapplication of external force. Moreover, while the anteroposterior shear force was large when only the head of the bed was elevated, the lateral shear force increased upon lower limb elevation. An example of elevating the head of the bed is presented here to explain these changes.

Figure 5. Changes in heel pressure and shear force with and without lower limb elevation

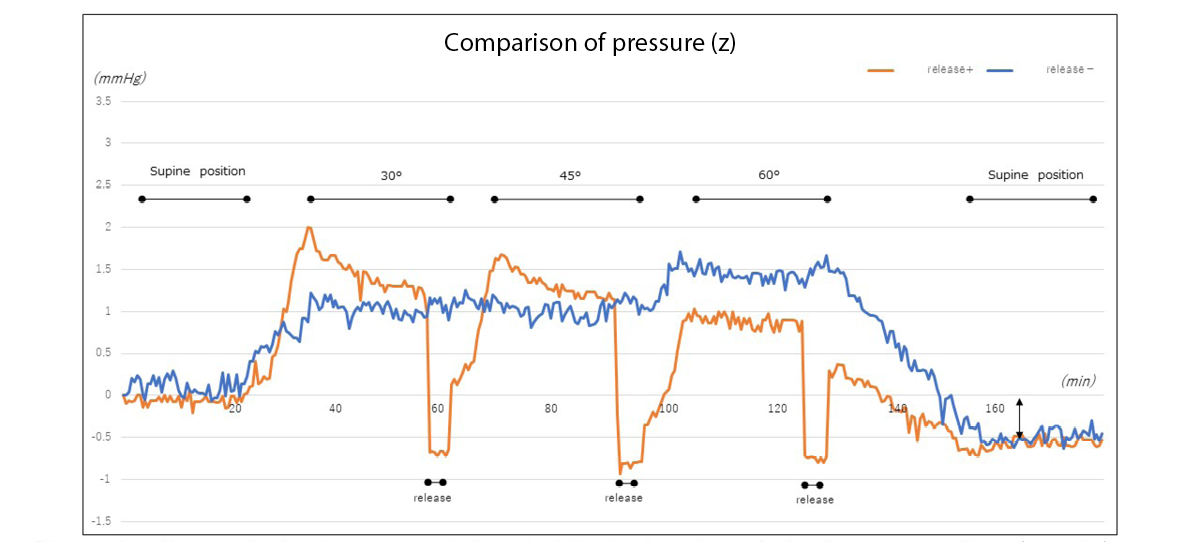

When the head of the bed was elevated to 30˚, elevation of the lower limbs temporarily offloaded the pressure on the heel. While further bed elevation once again increased pressure on the heel, lower limb elevation tended to inhibit subsequent increases in pressure (Figure 6a).

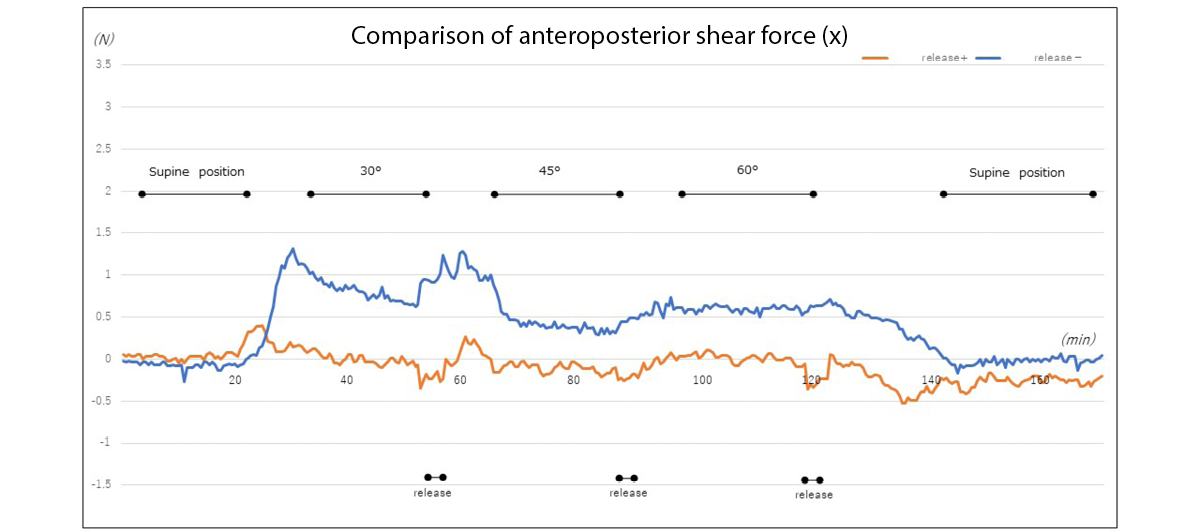

When the lower limbs were not elevated, the anteroposterior shear force increased slightly when the bed head was elevated to 30˚. On the other hand, when the lower limbs were elevated, no significant change occurred (Figure 6b).

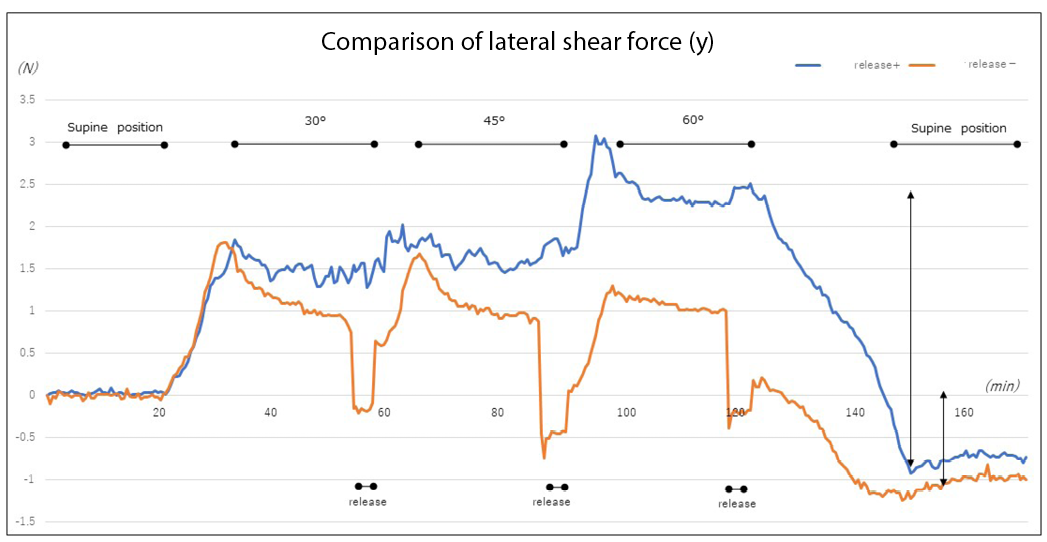

Similarly, the lateral shear force increased without elevation of the lower limb when the head of the bed was elevated to 30˚. On further elevation of the head of the bed, the lateral shear force increased in the absence of lower limb elevation. The greatest change occurred when the bed returned to the supine position. When the lower limb was elevated, the lateral shear force was temporarily offloaded. However, elevating the head of the bed again created lateral shear force. Although the difference in lateral shear force when the bed returned to the supine position was smaller than the difference observed without elevation of the lower limb, the results demonstrated the occurrence of lateral shear force associated with temporary offloading of force (Figure 6c).

Figure 6a. Changes in heel pressure with and without elevation of the lower extremity (example)

Figure 6b. Changes in anteroposterior shear force at the heel with and without elevation of the lower limb (example)

Figure 6c. Changes in lateral shear force at the heel with and without elevation of the lower limb (example)

Discussion

The experimental results revealed that the pressure and shear force at the heel increased with elevating the head of the bed. In particular, the rate of change in the values was large at the 30˚ angle of elevation. As previously reported, this is attributed to the effect of the centre of gravity shifting and upper body sliding down due to head elevation17–19. From the viewpoint of preventing pressure injury in the buttocks, it is desirable that the angle of elevating the head of the bed be 30˚ or less20. Although the 30˚ rule”(30˚ lateral supine, elevating the head of the bed by 30˚) has been widely used in positioning to prevent pressure injury, it has also been reported to delay healing in patients with pressure injury in the buttocks21. Therefore, the 4th edition of the Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers states that positioning other than the 30˚ side-lying and 30˚ supine positions may be performed22.

The heel is a common site of pressure injuries. Even if a visual assessment identifies no problems, tissue injury occurs, leading to deep tissue injury (DTI) due to changes inside the tissue. When pressure injuries are detected by a physician, the skin is often discoloured and injured, with DTI having already occurred16. As the heel is known to have a lower concentration of melanocytes, tissue response to stress and tissue injury are difficult to detect based on changes in skin colour23. In addition, while the epidermis may be thick in the lateral aspect of the sole of the heel, the skin of the posterior heel is relatively thin. In older adults and patients with fragile skin, capillary density is low and mass is reduced throughout the soft tissue in the posterior heel, adversely affecting the linkage between the epidermis and skin junctions24, conceivably increasing the risk of pressure injuries. Similar results were observed among the present study’s participants, despite having a mean BMI of 22.2 (±3.2) and standard body type. The participants’ BMI led to changes in mass throughout the soft tissue in the posterior heel. Conceivably, BMI and heel bone geometry also affected the linkage between the epidermis and skin junctions, suggesting an effect on pressure and shear force as well.

The present experiments demonstrated that powerful pressure and shear force occur when the head of a hospital bed is elevated to the recommended angle of 30˚. In the initial measurement, the head of the bed was elevated with the participant’s superior anterior iliac spine aligned with the bending point of the bed to prevent the body from sliding down. However, because the knees are not elevated and the heels are not supported, continuous strain on soft tissue leads to tissue injury25 and multiple thrombosis26, often causing DTI. In fact, this strain was shown to act as the anteroposterior and lateral shear forces due to elevation of the head of the hospital bed, elevation of the lower limbs, and other acts of nursing care. Although the lower limbs are elevated as a form of preventive care, we learned that this elevation does not entirely eliminate external force. This finding suggests the need for further preventive measures based on objective data.

The application of polyurethane foam/soft silicon foam to the heel has been reported to reduce friction and shear force on the heel, resulting in prevention of pressure injuries27,28. The skin of elder adults is dry, resulting in friction even when they sleep on bedsheets. The application of moisturiser, particularly the use of ceramide-containing formulations, to moisturise dry skin daily is reported to be an effective nursing intervention29; therefore, this intervention is also important to incorporate. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel guidelines also recommend the use of sheets made of silk or other similar material instead of cotton or cotton blends to reduce friction and shear force30.

Considering the advancements in body pressure redistribution devices, repositioning at conventional 2-hour intervals is reported to not differ from repositioning at 3- or 4-hour intervals31. When a patient’s body is repositioned (or their posture is maintained), it is supported with cushions and pillows. Although this study used four-section hospital beds, data in the present experiments were collected for the heel with only participants’ upper bodies being elevated and without elevation of the lower limb. However, with a bed that permits elevation of the lower limbs, conventional positioning requires elevation of the lower extremity side of the bed to prevent posture collapse and reduce pressure on the buttocks associated with the sliding down of the upper body; elimination of external force through means such as lower limb elevation may thus be required. Patients’ bodies are repositioned to regularly change their recumbent position and shift the external force that would otherwise continue to act on the same site.

However, while voluntary movement is also important, it is sometimes difficult for patients who have trouble moving on their own. In Japan, studies are being conducted on ‘small changes’, a body pressure dispersal method involving the use of a small pillow. ‘Small changes’ refers to a method in which a small pillow is moved at regular intervals to the shoulder, hip or lower extremity on one side of the body to change the site on which pressure acts and thus redistribute pressure. This method has been reported to reduce the incidence of pressure injuries32,33. Furthermore, an air mattress equipped with such a small change system has been developed, with a study having reported on its efficacy in preventing pressure injuries34.

Along with the measures described above to prevent pressure injuries in the heel, ultrasonography is also being used to detect pressure injuries at an early stage without relying on visual assessment35. Acquiring more basic data, such as that obtained in the present experiment, may be necessary.

More comments are needed on what is currently known about nursing interventions such as repositioning, frequency of repositioning to reduce pressure, shear force and friction, and the use of a knee-break or knee elevation capability of beds or simple devices such as pillows, etc to alleviate heel pressure shear and friction.

Limitations of the study and future challenges

In this study, the target age group was relatively young. Their skin structure in the heel region differs from that of older adults, who are more prone to pressure injury, and there are limitations when comparing with patients who are more prone to pressure injury. The mattress used was a urethane mattress, which is used to prevent pressure injury; hence, the effects of using other materials, such as an air mattress, need to be examined in the future.

Based on these results, we intend to consider more clinically-relevant positioning and pressure redistribution methods in the future. Additionally, we would like to check the changes occurring in not only the heel region but also the sacral region and other bone protrusion sites and collect data to provide evidence for nursing practice.

Conclusions

When elevation was performed, the pressure and shear force on the heel increased significantly at 30˚. The elevation of the lower limbs led to an offloading of continuous pressure and shear force on the heel, although the differences were not significant. However, we noted the pressure and shear force that occurred while elevating the head of the bed and determined that elevation of the lower limbs, a typical act of nursing care, does not prevent the application of shear force. Further examination with more objective data will be conducted to examine preventive nursing interventions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the study participants for their cooperation. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Jikei University School of Medicine, Tokyo (9212).

Funding

This study received a research grant from the School of Nursing, the Jikei University School of Medicine. However, they were not involved in any aspect of the study content, including study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; they only provided funding.

Pesquisa de descoberta de factos relacionados com a pressão e a força de cisalhamento no calcanhar usando um sensor táctil de três eixos

Yoko Murooka and Hidemi Nemoto Ishii

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.1.20-27

Sumário

Objetivos Investigamos as alterações na pressão e na força de cisalhamento no calcanhar causadas pela elevação da cabeceira da cama e após o alívio da pressão do calcanhar.

Métodos Os dados sobre a pressão do calcanhar e a força de cisalhamento foram recolhidos a partir de 26 indivíduos saudáveis com idade >30 anos utilizando um sensor táctil de três eixos em cada ângulo formado à medida que os corpos superiores dos participantes eram levantados de uma posição supina. Os dados foram recolhidos e comparados após a libertação de pressão do pé esquerdo ou direito.

Resultados A idade média dos participantes foi de 45,1 (±11,1) anos. A pressão e a força de cisalhamento ântero-posterior sobre o calcanhar aumentaram com a elevação. Estes aumentos eram especialmente proeminentes quando o ângulo de elevação era 30˚. Nas inclinações subsequentes 45˚ e 60˚, a pressão corporal e a força de cisalhamento aumentaram ligeiramente mas não significativamente. A pressão e a força de cisalhamento eram libertadas elevando a extremidade inferior de cada vez que a cabeceira da cama era elevada. No entanto, outras elevações resultaram num aumento da pressão e da força de cisalhamento, particularmente a força de cisalhamento lateral. A pressão e a força de cisalhamento não mudaram significativamente quando os membros inferiores foram elevados.

Conclusão A elevação recomendada da cabeceira da cama para não mais do que 30˚produziu grandes mudanças. A elevação da perna aliviou o calcanhar da pressão contínua e da força de cisalhamento, enquanto aumentava a pressão e a força de cisalhamento lateral. Embora a elevação das pernas seja uma componente diária dos cuidados de enfermagem, é importante investigar tais intervenções de enfermagem utilizando dados objetivos.

Introdução

Para além da relação entre a intensidade da pressão e o tempo, é evidente que as forças friccionais e de cisalhamento ocorrem como forças externas a um corpo vivo. As forças de cisalhamento obstruem o fluxo sanguíneo no tecido, resultando em isquemia do tecido1. No Japão, as lesões por pressão tendem frequentemente a desenvolver-se em idosos acamados e com proeminências ósseas. Eles são especialmente suscetíveis à fricção e às forças de cisalhamento, devido à secura e à reduzida elasticidade da pele2,3. Por este motivo, recomenda-se um reposicionamento regular para reduzir a pressão e a força de cisalhamento na pele4.

A prevenção de lesões por pressão requer não apenas uma redução sistémica da pressão corporal, mas também uma despressurização local e a redução da força de cisalhamento. Quando a cabeceira da cama de um paciente é elevada, o sacro e o cóccix são submetidos a uma forte pressão e a forças de cisalhamento, com alterações específicas na pressão e força de cisalhamento relatadas na região sacral5. Na prática clínica, estes problemas são abordados por meio da despressurização, que inclui dispositivos de redistribuição de pressão e a prestação de cuidados diários de enfermagem. Quando a cama de um doente é elevada ou baixada, duas dessas formas de cuidados de enfermagem para despressurização são a senuki (literalmente 'omissão nas costas') e a ashinuki (literalmente 'omissão nas pernas'). Senuki significa o cuidador levantar a parte superior do corpo do paciente e inserir a mão entre a cama e as costas do paciente para separar o corpo da cama quando ele é elevado, eliminando assim a fricção e a força de cisalhamento entre a pele do paciente e a sua roupa de cama. Ashinuki significa o cuidador elevar as pernas do paciente para eliminar a força de cisalhamento que de outra forma ocorreria desde a anca até à superfície posterior da coxa e calcanhar quando a cama é elevada ou baixada6.

Quando uma cama é elevada, fatores como a concentração de pressão nas nádegas e o deslizamento do corpo para baixo criam força de cisalhamento. Portanto, ao elevar a cama de um paciente, os enfermeiros fornecem várias formas de cuidados, tais como elevar primeiro as pernas, posicionar o paciente utilizando vários métodos, tais como inserir uma almofada debaixo dos joelhos para evitar o deslizamento e elevar a parte superior do corpo do paciente7-9. No entanto, estas intervenções de enfermagem foram relatadas em estudos que examinaram o sacro; poucos forma os estudos que examinaram alterações na pressão ou na força de cisalhamento no calcanhar10,11.

Na posição supina, o calcanhar é sujeito a uma pressão contínua, tornando-o vulnerável a lesões teciduais e de pressão. As lesões por pressão no calcanhar são relatadas como sendo responsáveis por um quarto de todas as lesões por pressão nos hospitais e lares americanos12-15. Os efeitos da elevação do leito e de outros fatores tornam o calcanhar suscetível à fricção16. Para reduzir esta fricção, são aplicados pensos preventivos17.

O presente estudo examinou a pressão e a força de cisalhamento no calcanhar utilizando um sensor táctil de três eixos. Além disso, o objetivo era o de confirmar alterações na pressão e na força de cisalhamento no calcanhar após a elevação da cabeceira das camas dos pacientes, seguida da elevação dos membros inferiores dos pacientes.

Métodos de Investigação

Desenho do estudo

Um estudo quase-experimental.

Seleção dos participantes e período de estudo

Foram recrutados voluntários saudáveis com idade >30 anos nas universidades e hospitais dos investigadores. O número de experiências clínicas dos participantes não foi considerado importante no desenho deste estudo. Cartazes para a cooperação na investigação foram afixados num quadro de avisos nas instalações de forma a solicitar a participação. O autor principal fez anúncios verbais e eletrónicos para divulgar o mesmo, e utilizou documentos para explicar as especificações da pesquisa a indivíduos que desejavam participar. Os indivíduos assinaram um termo de consentimento para confirmar a participação.

Os critérios de inclusão exigiam que os participantes não apresentassem feridas nos calcanhares. Vermelhidão temporária foi considerada hiperemia reativa e esses participantes foram incluídos.

Tamanho da amostra

Quando G*Power18 foi utilizado para analisar o tamanho da amostra com um efeito de tamanho de 0,8, α de 0,05 e um poder estatístico de 0,8, o tamanho da amostra foi calculado como sendo n=15. Devido à possibilidade de um efeito de medição insuficiente em alguns dos participantes, definimos o tamanho da amostra como sendo 20. O número objetivo de 20 participantes foi fixado em 15 para contabilizar as desistências durante a recolha de dados. Contudo, nenhum participante cumpriu os critérios de exclusão e todos foram incluídos.

Recolha de dados

Os dados foram recolhidos entre Outubro de 2018 e Março de 2019.

Ambiente de medição

A roupa de cama mais comummente utilizada foi selecionada para as medições. No entanto, para conveniência de reprodutibilidade, não foram utilizadas almofadas. Outro equipamento incluído:

- Cama elétrica: Cama Paramount KA-5000 (tipo 4-split) (Paramount Bed Corporation, Tóquio, Japão).

- Colchão de base: Everfit KE-521Q (Paramount Bed Corporation, Tóquio, Japão); colchão estático de 10cm de espessura.

- Lençol de cama: lençol de algodão de tecido liso. Os lençóis foram dobrados quando as camas foram feitas.

- Dispositivo de medição: Sensor táctil de três eixos (ShokacChip™ T08, Touchence Inc., Tóquio, Japão) 9 mm × 9 mm × 5 mm. Os eixos x, y e z do sensor de três eixos foram definidos de acordo com a pressão, força de cisalhamento ântero-posterior e força de cisalhamento lateral, respetivamente (Figuras 1a & b).

Figura 1. Um sensor táctil tri-axial foi fixado à área de contacto com a pele entre o calcanhar e a cama e foi coberto com um penso. Foram medidas três direções - força de cisalhamento ântero-posterior (eixo x), força de cisalhamento lateral (eixo y) e pressão (eixo z)

Procedimento de medição

Foram conduzidas duas experiências. A Experiência 1 mediu a pressão e a força de cisalhamento no calcanhar. A Experiência 2 mediu as alterações na pressão do calcanhar e a força de cisalhamento com e sem elevação dos membros inferiores.

Experiência 1: Alterações na pressão do calcanhar e na força de cisalhamento ao elevar a cabeceira da cama

Os participantes abriram ligeiramente os seus membros inferiores num estado relaxado e colocaram-se numa posição supina com a sua coluna ilíaca superior anterior alinhada com o ponto de flexão da cama. O sensor de três eixos foi aplicado no ponto central de onde o calcanhar esquerdo ou direito tocava a cama; o penso de filme foi aplicado por cima (Figuras 1a e b). O calcanhar esquerdo ou direito foi selecionado aleatoriamente e as seguintes séries de dados foram recolhidas:

1. Depois de confirmar que o corpo do participante estava imóvel, os dados para o calcanhar foram recolhidos durante um período de 20 segundos com a cama em posição supina.

2. Após 20 segundos, a parte superior do corpo do participante foi elevada do ponto de flexão da cama para um ângulo 30˚, medido com um goniómetro (Figura 2).

3. Após a elevação da parte superior do corpo do participante, os dados para o calcanhar foram recolhidos, enquanto o paciente permaneceu imóvel durante 20 segundos.

4. A parte superior do corpo do participante foi então elevada a 45˚ e os dados foram recolhidos da mesma forma.

5. Após a recolha de dados para a elevação de 60˚, a cama foi baixada para uma posição supina e os dados foram medidos durante 20 segundos, concluindo-se a experiência.

Experiência 2: Alterações na pressão do calcanhar e na força de cisalhamento, com e sem elevação dos membros inferiores

Tal como na Experiência 1, o membro inferior esquerdo ou direito foi selecionado aleatoriamente e foram repetidos os passos de recolha de dados 1-3 da Experiência 1. Na Experiência 2, a partir desse estado foram realizadas as seguintes intervenções.

4. Após 20 segundos, o joelho e o tornozelo esquerdo ou direito do participante foram segurados, levantados da anca e mantidos nessa posição durante 5 segundos (Figura 3).

5. Após a descida do membro inferior, este foi imediatamente elevado a um ângulo 45˚ , tendo sido recolhidos dados para o calcanhar enquanto o participante permaneceu imóvel durante 20 segundos.

6. Semelhante ao Passo 5 da Experiência 1, depois de o membro inferior ter sido rebaixado e a cabeceira da cama ter sido elevada a 60˚, a mesma medição foi realizada.

7. Por fim, a cabeceira da cama foi baixada para uma posição supina, os dados foram recolhidos durante 20 segundos e a experiência foi concluída.

O investigador, um enfermeiro especialista certificado em feridas, ostomia e continência realizaram as Experiências 1 e 2 neste estudo.

Figura 2. Deitado na cama (no momento da elevação da cabeceira da cama)

Figura 3. Levantamento dos membros inferiores

Análise dos dados

Os dados foram analisados estimando a média dos pontos de observação em 18 segundos sem considerar os segundos antes e depois; foi também tida em consideração a influência dos dados do movimento ântero-posterior dos 20 segundos medidos para cada ângulo de elevação. Os cálculos foram efetuados considerando a média dos pontos de observação sem os segundos antes e depois. No início da medição, o valor inicial dos dados foi calibrado para zero e medido duas vezes. Os dados obtidos a partir dos sensores foram analisados ao longo do eixo x (força de cisalhamento ântero-posterior), eixo y (força de cisalhamento lateral) e eixo z (pressão). A pressão e a força de cisalhamento, com e sem pressão de descarga do calcanhar em cada um dos ângulos, foram analisadas utilizando um software de dados dedicado e foi realizada uma ANOVA bidirecional. Todas as análises estatísticas foram realizadas usando SPSS 23.0 para Windows (IBM Corp. Armonk, N.Y., EUA) e o nível de significância foi estabelecido em 5%.

Considerações éticas

O estudo foi aprovado pelo Comité de Revisão Ética da Escola de Medicina da Universidade de Jikei, Tóquio (9212). Os participantes foram informados do estudo oralmente e por escrito, incluindo as instruções para o estudo. O estado de saúde dos participantes foi sempre observado durante a medição dos dados. Foram informados de que o procedimento seria interrompido se sentissem desconforto. Após a recolha de dados, foram investigadas quaisquer condições adversas, tais como indentação da pele causada pela aplicação do sensor no calcanhar do participante ou descamação epidérmica causada pela aplicação do material do penso.

Resultados

Atributos do assunto

O estudo foi realizado com 26 participantes (11 homens e 15 mulheres) com uma idade média de 45,1 (±11,1) anos e um IMC médio de 22,2 (±3,2) anos. Nenhum participante preencheu os critérios de exclusão e não ocorreram acontecimentos adversos.

Experiência 1: Alterações na pressão do calcanhar e na força de cisalhamento ao elevar a cabeceira da cama

A variação da pressão no calcanhar tendeu a aumentar e a manter o seu valor à medida que a cabeceira da cama foi levantada (Figura 4a). Em particular, a pressão aumentou significativamente quando a cabeceira da cama foi elevada da posição supina para 30˚. Posteriormente, os valores de pressão foram mantidos para os ângulos de elevação de 45˚ e de 60˚; não foi observado qualquer aumento significativo. No entanto, foi observada uma diferença significativa quando o ângulo foi alterado de 60˚ para a posição supina. A pressão inicialmente diminuiu, mas não regressou à pressão inicial, que diminuiu ainda mais.

A força de cisalhamento na direção frente-atrás tendeu a aumentar com o ângulo de elevação. De forma semelhante aos valores de pressão encontrados, o valor aumentou significativamente no ângulo de elevação 30˚, tendo sido observada uma diferença significativa. Após os 45˚, a força de cisalhamento ântero-posterior foi mantida, mas não aumentou significativamente quando o ângulo foi elevado da posição supina para 60˚. No entanto, quando o ângulo foi alterado de 60˚ para a posição supina, foi adicionada força de cisalhamento na direção oposta, tendo sido observada uma diferença significativa (Figura 4b).

Embora a força de cisalhamento lateral tenha aumentado à medida que a cabeceira da cama foi elevada, esta não se alterou tanto como a força de cisalhamento ântero-posterior. Foi observada uma diferença significativa quando a cama foi baixada de um ângulo de 60˚ para uma posição supina. No entanto, as grandes alterações que ocorreram na força de cisalhamento ântero-posterior não ocorreram no caso da força de cisalhamento lateral (Figura 4c).

Figura 4. Mudanças na pressão do calcanhar e na força de cisalhamento ao elevar a cabeceira da cama

Experiência 2: Alterações na pressão do calcanhar e na força de cisalhamento, com e sem elevação dos membros inferiores

Os exames das alterações de pressão com e sem elevação dos membros inferiores não mostraram diferenças significativas na pressão, na força de cisalhamento ântero-posterior, ou na força de cisalhamento lateral (Figura 5). No entanto, tal como nas medições feitas com a elevação simples da cabeceira da cama, mesmo quando a pressão e a força de cisalhamento foram descarregadas, a elevação da cabeceira da cama levou à reaplicação da força externa. Além disso, enquanto a força de cisalhamento ântero-posterior era grande quando unicamente a cabeceira da cama era elevada, a força de cisalhamento lateral aumentava na elevação dos membros inferiores. Um exemplo de elevação da cabeceira da cama é aqui apresentado para explicar estas mudanças.

Figura 5. Alterações na pressão do calcanhar e na força de cisalhamento, com e sem elevação dos membros inferiores

Quando a cabeceira da cama foi elevada a 30˚, a elevação dos membros inferiores descarregou temporariamente a pressão sobre o calcanhar. Enquanto que a elevação da cama mais uma vez aumentou a pressão sobre o calcanhar, a elevação dos membros inferiores tendeu a inibir os aumentos subsequentes na pressão (Figura 6a).

Quando os membros inferiores não foram elevados, a força de cisalhamento ântero-posterior aumentou ligeiramente quando a cabeceira da cama foi elevada a 30˚. Por outro lado, quando os membros inferiores foram elevados, não ocorreu uma alteração significativa (Figura 6b).

Da mesma forma, a força de cisalhamento lateral aumentou sem a elevação do membro inferior quando a cabeceira da cama foi elevada para 30˚. Na elevação adicional da cabeceira da cama, a força de cisalhamento lateral aumentou na ausência de elevação dos membros inferiores. A maior alteração ocorreu quando a cama voltou para a posição supina. Quando o membro inferior foi elevado, a força de cisalhamento lateral foi temporariamente descarregada. No entanto, elevar novamente a cabeceira da cama criou uma força de cisalhamento lateral. Embora a diferença de força de cisalhamento lateral quando a cama regressou à posição supina fosse menor do que a diferença observada sem a elevação do membro inferior, os resultados demonstraram a ocorrência de força de cisalhamento lateral associada à descarga temporária de força (Figura 6c).

Figura 6a. Alterações na pressão do calcanhar, com e sem elevação da extremidade inferior (exemplo)

Figure 6b. Alterações na força de cisalhamento ântero-posterior no calcanhar, com e sem elevação do membro inferior (exemplo)

Figure 6c. Alterações na força de cisalhamento lateral no calcanhar, com e sem elevação do membro inferior (exemplo)

Discussão

Os resultados experimentais revelaram que a pressão e a força de cisalhamento no calcanhar aumentaram com a elevação da cabeceira da cama. Em particular, a taxa de alteração dos valores foi elevada no ângulo de elevação 30˚. Tal como anteriormente relatado, isto é atribuído ao efeito do deslocamento do centro de gravidade e ao deslizamento para baixo da parte superior do corpo devido à elevação da cabeceira 17-19. Do ponto de vista da prevenção de lesões por pressão nas nádegas, é desejável que o ângulo de elevação da cabeceira da cama seja de 30˚ ou menor20. Embora a “regra 30˚"(30˚ lateral supina, elevando a cabeceira da cama em 30˚) tenha sido amplamente utilizada no posicionamento para evitar lesões por pressão, também tem sido relatado que esta abordagem atrasa a cicatrização em pacientes com lesões por pressão nos glúteos21. Portanto, a 4ª edição das Diretrizes para a Prevenção e Gestão das Úlceras de Pressão afirma que outros posicionamentos para além das posições laterais e supinas 30˚ podem ser realizados22.

O calcanhar é um local comum de lesões por pressão. Mesmo que uma avaliação visual não identifique problemas, podem ocorrer lesões nos tecidos, levando a lesões profundas nos tecidos (DTI) devido a alterações no interior dos tecidos. Quando lesões por pressão são detetadas por um médico, a pele apresenta-se frequentemente descolorada e lesionada, tendo o DTI já ocorrido16. Como o calcanhar é conhecido por ter uma menor concentração de melanócitos, a resposta dos tecidos ao stress e à lesão tecidual é difícil de detetar com base nas alterações da cor da pele23. Além disso, enquanto a epiderme pode ser espessa na face lateral da sola do calcanhar, a pele do calcanhar posterior é relativamente fina. Em adultos idosos e pacientes com pele frágil, a densidade capilar é baixa e a massa é reduzida em todo o tecido mole na região posterior do calcanhar, afetando negativamente a ligação entre a epiderme e as junções cutâneas24, aumentando de forma apreciável o risco de lesões por pressão. Resultados semelhantes foram observados entre os participantes do presente estudo, apesar de apresentarem um IMC médio de 22,2 (±3,2) e um tipo de corpo padrão. O IMC dos participantes levou a alterações na massa em todo o tecido mole na região posterior do calcanhar. É concebível que o IMC e a geometria do osso do calcanhar também tenham afetado a ligação entre a epiderme e as junções da pele, sugerindo um efeito também sobre a pressão e sobre a força de cisalhamento.

As presentes experiências demonstraram que a pressão forte e a força de cisalhamento ocorrem quando a cabeceira de uma cama hospitalar é elevada para o ângulo recomendado de 30˚. Na medição inicial, a cabeceira da cama foi elevada com a coluna ilíaca anterior superior do participante alinhada com o ponto de flexão da cama para evitar que o corpo deslizasse para baixo. No entanto, como os joelhos não estão elevados e os calcanhares não estão apoiados, a tensão contínua nos tecidos moles leva a lesões teciduais25 e à trombose múltipla26, causando frequentemente DTI. De facto, demonstrou-se que esta tensão atuava como força de cisalhamento ântero-posterior e lateral devido à elevação da cabeceira da cama hospitalar, à elevação dos membros inferiores e a outros atos de cuidados de enfermagem. Embora os membros inferiores sejam elevados como forma de cuidado preventivo, aprendemos que esta elevação não elimina totalmente a força externa. Esta descoberta sugere a necessidade de mais medidas preventivas com base em dados objetivos.

Foi relatado que a aplicação de espuma de poliuretano/espuma de silicone suave no calcanhar reduz o atrito e a força de cisalhamento no calcanhar, resultando na prevenção de lesões por pressão27,28. A pele dos adultos mais idosos é seca, resultando em fricção, mesmo quando dormem em lençóis. A aplicação de um hidratante, particularmente a utilização de formulações contendo ceramidas, para hidratar diariamente a pele seca é relatada como sendo uma intervenção de enfermagem eficaz29; por conseguinte, esta intervenção é também importante para ser incorporada. As diretrizes do Painel Consultivo Europeu sobre Úlceras de Pressão também recomendam a utilização de lençóis feitos de seda ou de outro material similar em vez de algodão ou de misturas de algodão, para reduzir a fricção e a força de cisalhamento30.

Considerando os avanços nos dispositivos de redistribuição da pressão corporal, é relatado que o reposicionamento em intervalos convencionais de 2 horas não difere do reposicionamento em intervalos de 3 ou 4 horas31. Quando o corpo de um paciente é reposicionado (ou a sua postura é mantida), ele é apoiado com almofadas e travesseiros. Embora este estudo tenha utilizado camas hospitalares de quatro secções, os dados nas experiências em causa foram recolhidos para o calcanhar, sendo apenas os corpos superiores dos participantes elevados e sem elevação do membro inferior. No entanto, utilizando-se uma cama que permite a elevação dos membros inferiores, o posicionamento convencional requer a elevação da extremidade inferior da cama para evitar o colapso da postura e reduzir a pressão sobre as nádegas associada ao deslizamento para baixo da parte superior do corpo; a eliminação da força externa através de meios como a elevação dos membros inferiores pode, portanto, ser necessária. Os corpos dos pacientes são reposicionados para mudarem regularmente a sua posição reclinada e assim deslocarem a força externa, que de outra forma continuaria a atuar no mesmo local.

No entanto, apesar de o movimento voluntário ser também importante, por vezes é difícil para os pacientes que têm dificuldade em mover-se de forma autónoma. No Japão, estão a ser realizados estudos sobre 'pequenas alterações', que consistem num método de dispersão da pressão corporal que envolve a utilização de uma pequena almofada. pequenas alterações" refere-se a um método em que uma pequena almofada é deslocada a intervalos regulares para o ombro, anca ou para a extremidade inferior de um lado do corpo para alterar o local onde a pressão atua e assim redistribuir a pressão. Este método tem sido relatado como forma de reduzir a incidência de lesões por pressão32,33. Além disso, foi desenvolvido um colchão de ar equipado com um sistema de mudança tão pequeno, suportado por um estudo que relatou a sua eficácia na prevenção de lesões por pressão34.

Juntamente com as medidas acima descritas para prevenir lesões por pressão no calcanhar, a ecografia está também a ser utilizada para detetar lesões por pressão numa fase precoce, sem depender de uma avaliação visual35. A aquisição de dados mais básicos, tais como os obtidos na presente experiência, pode ser necessária.

São necessários mais comentários sobre o que é atualmente conhecido sobre intervenções de enfermagem, tais como o reposicionamento, a frequência de reposicionamento para reduzir a pressão, a força de cisalhamento e de fricção e a utilização da capacidade das camas para dobrar ou elevar o joelho ou de dispositivos simples como almofadas, etc., para aliviar a pressão de cisalhamento e a fricção do calcanhar.

Limitações do estudo e desafios futuros

Neste estudo, a faixa etária alvo era relativamente jovem. A sua estrutura cutânea na região dos calcanhares difere da dos adultos mais idosos, que são mais propensos a lesões por pressão, existindo limitações quando comparados com os pacientes mais propensos a lesões por pressão. Foi utilizado um colchão de uretano, o qual é utilizado para evitar lesões por pressão; por conseguinte, é necessário no futuro examinar os efeitos da utilização de outros materiais, tais como um colchão de ar.

Com base nestes resultados, pretendemos no futuro considerar métodos de posicionamento e de redistribuição de pressão mais clinicamente relevantes. Além disso, gostaríamos de verificar as alterações que ocorrem não apenas na região do calcanhar, mas também na região sacral e em outros locais de protrusão óssea e recolher dados para fornecer evidências para a prática de enfermagem.

Conclusões

Quando foi realizada a elevação, a pressão e a força de cisalhamento no calcanhar aumentaram significativamente aos 30˚. A elevação dos membros inferiores levou a uma descarga de pressão contínua e a uma força de cisalhamento no calcanhar, embora as diferenças não fossem significativas. No entanto, notámos que a pressão e a força de cisalhamento ocorreram ao elevar a cabeceira da cama e determinámos que a elevação dos membros inferiores, um ato típico em cuidados de enfermagem, não impede a aplicação da força de cisalhamento. Um exame mais aprofundado com dados mais objetivos será realizado, de forma a examinar as intervenções preventivas de enfermagem.

Agradecimentos

Gostaríamos de agradecer a todos os participantes no estudo pela sua cooperação. Gostaríamos também de agradecer à Editage (www.editage.com) pela edição em língua inglesa.

Conflito de Interesses

Não existem conflitos de interesse a declarar.

Declaração ética

O estudo foi aprovado pelo Comité de Revisão Ética da Escola de Medicina da Universidade de Jikei, Tóquio (9212).

Financiamento

Este estudo recebeu uma bolsa de investigação da Escola de Enfermagem, a Escola de Medicina da Universidade de Jikei. No entanto, não estiveram envolvidos em nenhum aspeto do conteúdo do estudo, incluindo a conceção do estudo, a recolha de dados e a análise ou interpretação dos dados; apenas forneceram financiamento.

Author(s)

Yoko Murooka*

RN, PhD, WOCN

Faculty of Nursing, Tokyo University of Information Sciences,

4–1 Onaridai, Wakaba-ku, Chiba, 265–8501 Japan

Email myoko0913@gmail.com

Hidemi Nemoto Ishii

RN, MSN, ET/WOCN

Wound & Ostomy Care Division, ALCARE Co. Ltd., Sumida-ku,

Tokyo, Japan

* Corresponding author

References

- Manorama A, Meyer R, Wiseman R, Bush T. Quantifying the effects of external shear loads on arterial and venous blood flow: implications for pressure ulcer development. Clin Biomech 2013;28(5):574–78.

- Leyva-Mendivil MF, Lengiewicz J, Page A, et al. Skin microstructure is a key contributor to its friction behaviour. Tribol Lett 2017;65(1):12.

- Vianna V, Broderick L, Cowan L. Pressure injury related to friction and shearing forces in older adults. J Dermatol & Skin Sci 2021;3(2):9–12.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: clinical practice guideline. The International Guideline. Emily Heasler, editor. EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA 2019.

- Mimura M, Okazaki H, Kajiwara T, et al. Variation of body pressure and shear force during bed manipulation (Part 1): effect of body shape and bed manipulation. J Jap Soc Bedsores 2007;9:11–20 (in Japanese).

- Ishikawa H, Hata M, Kondo Y. The effect of back-pulling during head-up and head-down. Asahikawa Red Cross Hosp Med J 2011;31–33 (in Japanese).

- Mori M, Endo A, Oshimoto Y. Fabrication of a cushion to reduce pressure on the buttocks during back elevation and a study of its effectiveness. J Jap Soc Bedsores 2010;12:509–12 (in Japanese).

- Y, Otsuka N, Ibe F, et al. Relationship of 45˚ head-side up and knee elevation and local pressure at the sacral region. Jap J PU 2009;11(1):40–6.

- Harada C, Shigematsu T, Hagisawa S. The effect of 10-degree leg elevation and 30-degree head elevation on body displacement and sacral interface pressures over a 2-hour period. J WOCN 2002:29(3):143–48.

- Lippoldt J, Pernicka E, Staudinger T. Interface pressure at different degrees of backrest elevation with various type of pressure-redistribution surfaces. Am J Crit Care 2014;23(2):119–26.

- Defloor T. The effect of position and mattress on interface pressure. Appl Nurs Res 2000;13(1):2–11.

- Anderwee K, Clark M, Dealey C, et al. Pressure ulcer prevalence in Europe: a pilot study. J Eval Clin Pract 2007;13(2):227–35.

- VanGilder C, Macfarlane GD, Meyer S. Results of nine international pressure ulcer prevalence surveys: 1989 to 2005. Ostomy Wound Manage 2008;54(2):40–54.

- VanGilder C, Amlung S, Harrison P, Meyer S. Results of the 2008–2009 International Pressure Ulcer Prevalence Survey and a 3-year, acute care, unit specific analysis. Ostomy Wound Manage 2009;55(11):39–45.

- VanGilder C, Lachenbruch C, Algrim-Boyle C, Meyer S. The International Pressure Ulcer Prevalence Survey 2006–2015: a 10-year pressure injury prevalence and demographic trend analysis by care setting. J WOCN 2017;44(1):20–8.

- Gefen A. Why is the heel particularly vulnerable to pressure ulcers? Br J Nurs 2017;26(Sup20):S62–S74.

- Nakagami G, Sanada H, Konya C, et al. Comparison of two pressure ulcer preventive dressings for reducing shear force on the heel. J WOCN 2006;33(3):267–72.

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91.

- Okubo Y, Kohase M, Ogawa KI. Influence of raising and lowering the back of the bed on the body. J Jap Soc Bedsores 2000;2:45–50 (in Japanese).

- Grey JE, Harding KG, Enoch S. Pressure ulcers. BMJ 2006;332:472–75.

- Okuwa M, Sugama J, Sanada H, et al. Measuring the pressure applied to the skin surrounding pressure ulcers while patients are nursed in the 30 degree Position. J Tissue Viab 2005;15(1):3–8.

- The Japanese Society of Pressure Ulcers Guideline Revision Committee. JSPU guidelines for the prevention and management of pressure ulcers (4th ed.). Jpn J PU 2015;17(4):487–557.

- McCreath HE, Bates-Jensen BM, Nakagami G, et al. Use of Munsell Color Charts to objectively measure skin color in nursing home residents at risk for pressure ulcer development. J Adv Nurs 2016;72(9):2077–85.

- Gefen A. Tissue changes in patients following spinal cord injury and implications for wheelchair cushions and tissue loading: a literature review. Ostomy Wound Manage 2014;60(2):34–45.

- Takahashi M, Shimomichi M, Ohura T. Effects of pressure and shear force on blood flow in the radial artery and skin capillaries. J Jap Soc Bedsores 2012;14:547–52 (in Japanese).

- Takeda T. An experimental study on the effects of friction and displacement on the occurrence of bedsore. J Jap Soc Bedsores 2001;3:38–43 (in Japanese).

- Santamaria N, Gerdtz M, Sage S, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of soft silicone multi-layered foam dressings in the prevention of sacral and heel pressure ulcers in trauma and critically ill patients: the border trial. Int Wound J 2013;12(3):302–8.

- Ferrer Solà M, Espaulella Panicot J, Altimires Roset J, et al. Comparison of efficacy of heel ulcer prevention between classic padded bandage and polyurethane heel in a medium-stay hospital: randomized controlled trial. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2013;48(1):3–8.

- Takeshi K, Yoshiki M, Makoto K. Clinical significance of the water retention and barrier function: improving capabilities of ceramide-containing formulations: a qualitative review. J Dermatol 2021;48(12):1807–16.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: quick reference guide. Available from: http://tinyurl.com/yck2mmr6

- Moore Z, Cowman S, Conroy RM. A randomized controlled clinical trial of repositioning, using the 30˚ tilt, for the prevention of pressure ulcers. J Clin Nurs 2011;20(17–18):2633–44.

- Brown MM, Boosinger J, Black J, et al. Nursing innovation for prevention of decubitus ulcers in long term care facilities. Plast Surg Nurs 1985;5:57–64.

- Smith AM, Malone JA. Preventing pressure ulcers in institutionalized elders: assessing the effects of small, unscheduled shifts in body position. Decubitus 1990;3:20–4.

- Dai M, Yamanaka T, Matsumoto M, et al. Effectiveness of the air mattress with small change system on pressure ulcer prevention: a pilot study in a long-term care facility. J Jap WOCM 2018;22(4):357–62.

- Nagase T, Koshima I, Maekawa T, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of an unusual peri-anal induration: a possible case of deep tissue injury. J Wound Care 2007;16(8):365–7.