Volume 26 Number 2

Solutions to the chronic wounds problem in Australia: a call to action

Rosana E Pacella, Ruth Tulleners, Qinglu Cheng, Ellen Burkett, Helen Edwards, Stephen Yelland, David Brain, John Bingley, Peter Lazzarini, Jason Warnock, Louise Barnsbee, Tamzin Pacella, Kevin Clark, Michele Smith, Ian Griffiths, Geoff Sussman, Jaap van Netten, Michelle Gibb, Jodie Gordon, Gillian Harvey, Donna Hickling, Xing Lee, Bernd Ploderer, Alison Vallejo, Sharon Whalley, and Nicholas Graves on behalf of the Chronic Wounds Solutions Collaborating Group.

Keywords Chronic wounds, Australia, evidence-based wound care, cost-effectiveness, awareness, recommendations, call to action.

Abstract

Background: Chronic wounds are a silent epidemic in Australia. They are an under-recognised public health issue, and their significant health and economic impact is underestimated. Evidence-based practice in wound care has significant health and economic benefits, yet there are still considerable evidence–practice gaps.

Methods: Stakeholders attended a national forum to refine and prioritise solutions to the chronic wounds problem in Australia. A survey was administered to identify key priorities and recommendations.

Results: Stakeholders agreed on 17 recommendations and strategies to improve the outcomes of Australians with chronic wounds. The identified priorities for immediate action were to raise awareness of the significance of chronic wounds, and to make chronic wounds a strategic priority for governments. The Chronic Wounds Solutions Collaborating Group was established to encourage, support and monitor action on the implementation of these recommendations.

Conclusions: Large health and economic gains can be achieved with modest investments in evidence-based strategies for the prevention and control of chronic wounds in Australia. We call for a critical and sustained national effort to prevent and treat chronic wounds in Australia. Urgent action is needed at all levels if Australia is to reduce the significant preventable burden of chronic wounds and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Chronic wounds are an under-recognised issue in Australia. They are under-considered in terms of research and public policy, receiving little attention and investment compared to other chronic conditions1. This apathy is unjustified given the associated disease and economic burdens. Chronic wounds severely reduce quality of life and capacity to work, and they increase social isolation2,3. They also impose substantial costs on patients and the health care system. The implementation of evidence-based wound care coincides with large health improvements4,5 and cost savings4-7, but research has demonstrated that the majority of Australians with chronic wounds do not receive evidence-based treatment4,8,9. Furthermore, as wound management is not recognised as a discrete health care field or a national health priority, securing impetus for change is challenging.

Box 1: Key messages

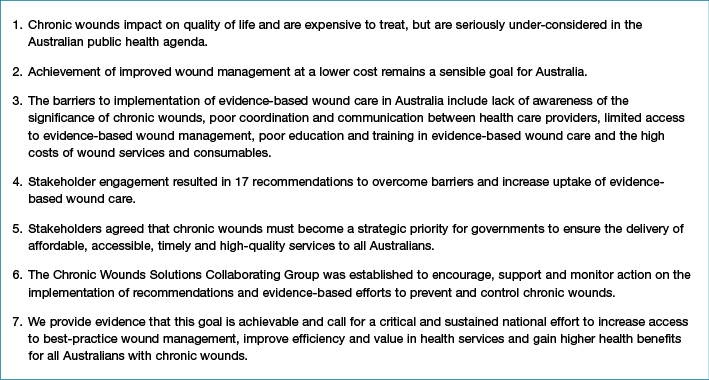

Wound management and funding in Australia is complex, involving a multitude of service providers with poor continuity of evidence-based prevention and treatment along the health service continuum4. Key barriers to the implementation of evidence-based wound care include: lack of awareness of the significance of chronic wounds, complex and uncoordinated services with poor communication between health care providers, poor access to wound services, poor education and training of healthcare professionals and the high costs of wound services and products10 (Figure 1). The poor implementation of evidence-based care means chronic wounds take longer to heal, require more intensive intervention, often result in hospitalisation through infection and other complications, and have high recurrence rates. They also represent a significant burden of avoidable costs1.

There is a lack of current, reliable data on the prevalence and costs of chronic wounds in Australia. Based on data from several high-income countries11, it is estimated that there are 420,000 cases of chronic wounds in hospital and residential care settings in Australia each year. Pressure injuries are the most common wound type, comprising 84% of all wounds, followed by venous leg ulcers (VLUs) (12%), diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) (3%) and arterial insufficiency ulcers (AUs) (1%)12. Regardless of wound type, the treatment costs are substantial. Chronic wounds are estimated to cost US$2.85 billion (about A$3.7 billion) annually, or approximately 2% of Australian national health care expenditure12. These recorded costs only include those incurred in hospitals and residential care settings, but not general practice and community nursing costs, indirect costs of lost productivity, the intangible costs of pain and suffering, and travel or other costs of consumables to individual patients1.

There are many studies which have demonstrated the effectiveness of different chronic wound treatment options and product-oriented interventions4,7,13-16. Evidence-based wound care has also been found to be cost-effective and even cost-saving17-21.

Unfortunately, in general, this has not resulted in a widespread or sustained change to practice in Australia. This research aimed to investigate solutions, through stakeholder engagement, to the current knowledge translation challenges.

Methods

Stakeholder Engagement Part 1 — Chronic Wounds Solutions Forum

Stakeholders were invited to attend the Chronic Wounds Solutions Forum held on 31 August 2017 in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. This national forum was organised by the Australian Centre for Health Services Innovation (AusHSI), with support from Queensland Government, Metro North Hospital and Health Service, Clinical Excellence Division, Brisbane North Primary Health Network, and the Wound Management Innovation Cooperative Research Centre (WMI CRC). Invited stakeholders included policy makers, chronic wound specialist clinicians, general practitioners, representatives of Primary Health Networks and Hospital and Health Services, consumers with previous or ongoing chronic wounds, private health insurers, consumer advocates, private sector and pharmaceutical industry representatives, health economists and university academics from across Australia.

The aim of the forum was to provide an opportunity for key stakeholders to bring together their knowledge and expertise to: firstly, explore the identified barriers to evidence-based wound management and the delivery of wound services in Australia, and secondly, discuss solutions to the chronic wounds problem. The forum consisted of didactic presentations of identified barriers10 from the perspective of select national experts, followed by active participation and sharing of ideas using the World Café method22. A panel of experts summarised the recommendations arising from the forum with input from the larger group of participants. This discussion was recorded through non-identifiable notes. Content generated throughout the forum, including the presentations and panel discussion, was also captured by a graphic recording artist.

Stakeholder Engagement Part 2 — Online survey to identify priority recommendations

Stakeholders were contacted by email approximately two months after attending the forum, and asked to complete an online survey. Data were collected through the online platform SurveyMonkey23, using a secure account. Settings within the survey tool were configured to ensure that personal information, beyond the questions in the survey, was not recorded, thus ensuring that all responses remained anonymous. The aim of the survey was to identify priorities for action to overcome barriers and increase uptake of evidence-based wound management, in the areas of education, access and financial support for wound services and products. The survey consisted of ranking questions asking survey respondents to compare a list of different recommendations to one another as follows: “Please rank each of the following items in order of importance with #1 being the most important recommendation to #6 being the least important.”

Stakeholder Engagement Part 3 — Establishment of The Chronic Wounds Solutions Collaborating Group

The Chronic Wounds Solutions Collaborating Group emerged from a partnership between the chronic wound stakeholders, experts and consumers attending the Chronic Wounds Solutions forum and was modelled on the success of the Chronic Disease Action Group24, adopting their framework and call to action to encourage, support and monitor the implementation of evidence-based efforts. The group consists of the participants who attended the forum and agreed to join the group, along with external researchers, academics and experts who are closely involved in the project.

Approval for this research was obtained from the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval Number: 1700000960).

Results

An image depicting the visual recording of the Chronic Wounds Solutions Forum is shown in Figure 2. A total of 121 stakeholders were invited to attend the forum, with 87 of these invitees attending on the day. As forum participants were those at the forefront of Australian wound management, they were able to provide useful information from a variety of perspectives and make recommendations to benefit patients and improve health service delivery. When drafting the 17 key recommendations arising from discussion at the forum (Table 1), the focus was on capturing what participants considered attainable and achievable. The recommendations were designed to incite action and encourage uptake. We acknowledge that many of these recommendations are interconnected and could address more than one barrier.

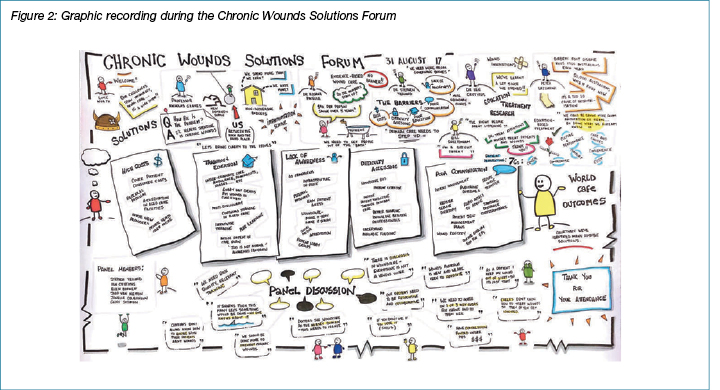

Table 1: Recommendations arising from Chronic Wounds Solutions Forum

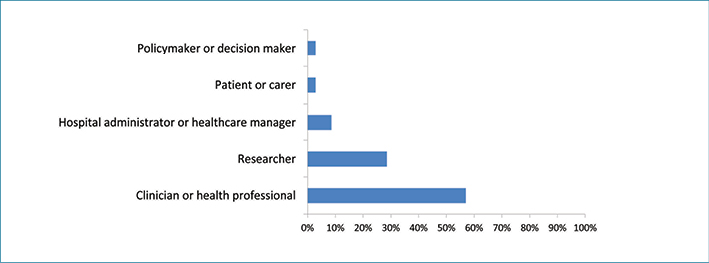

Out of the 87 forum participants contacted by email, 38 completed the online survey with a response rate of 43.68%. Figure 3 displays the breakdown of respondents. Most respondents who completed the online survey were clinicians or health care providers (57.14%), followed by researchers (28.57%), hospital administrators (8.57%), policy and decision makers (2.86%), and patients or carers (2.86%).

Figure 3: Respondents to stakeholder survey

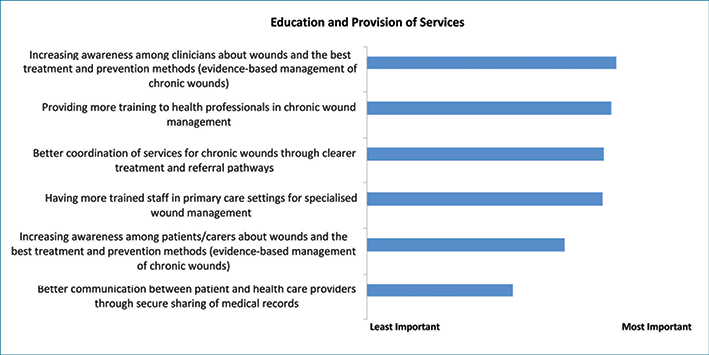

Figures 4 and 5 display the results of the online survey. When asked to prioritise recommendations regarding education and provision of services, stakeholders identified increasing awareness among clinicians about chronic wounds and their management as the highest priority for action.

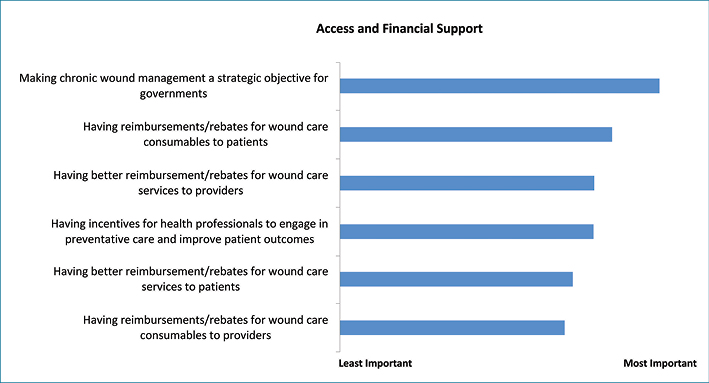

With regard to financial barriers and access to services, stakeholders identified making chronic wounds management a strategic objective for governments as the highest priority, followed by adequate reimbursement for patients for wound care products, and better incentives for healthcare professionals to engage in preventative care and improve patient outcomes.

Figure 4: Results of stakeholder survey — Education and Provision of Services in chronic wound care

Figure 5: Results of stakeholder survey — Access and Financial Support

Discussion

Through this process of stakeholder engagement, we were able to determine consensus as to where to prioritise action, forming the basis of key recommendations. Evidence-based care for all Australians with chronic wounds relies on the availability of resources, political and community support and improved cohesion of state and national health systems. We also need an approach that draws on evidence from high-quality research. Achievement of the recommendations should ultimately lead to improved health outcomes for all Australians with chronic wounds. Suggested strategies to achieve the recommendations listed in Table 1 draw on successful existing local and international initiatives for chronic wounds and other chronic diseases, discussed in more detail below.

Advocacy and awareness

Chronic wounds should be one of Australia’s National Health Priority Areas

Stakeholders agreed that there is a critical need to raise awareness of the significance of chronic wounds and for improved wound management at a lower cost to be made a strategic objective for government. There is also a need to raise awareness of the important links between chronic wounds and the Australian National Health Priority Areas, and to recognise chronic wound management as a National Health Priority Area in its own right25. This has the potential to secure increased support from policy-makers and research funders25, as has already occurred for other National Health Priority areas, such as diabetes26,27.

Launch public health campaign

Australia has been a world leader in several public health campaigns, resulting in raised awareness, behaviour changes and reductions in associated mortality and morbidity. Examples include the ‘Reduce the Risks’ sudden infant death syndrome campaign28,29, the ‘FAST’ stroke awareness campaign30-32, various anti-smoking campaigns33-35, and the ‘Slip! Slop! Slap!’ sun safety campaign36. This last campaign proved particularly effective, with programs currently operating in each state and territory of Australia by respective Cancer Councils, all using common principles but tailored to jurisdictional priorities37. The campaign has achieved a steady decline in the incidence of invasive melanoma36 and is estimated to have resulted in a net cost saving of A$92 million nationwide37,38.

The success of this campaign may be attributed to the evolving nature of the messages it presented. Initially the importance of sun safety was not understood by members of the community39; similarly, the impact of chronic wounds is not currently well understood. Until there is widespread concern and interest in chronic wounds, there will be limited efforts to resolve the problem39. Chronic wounds mass media campaigns should target the broader population and as the campaign evolves, the focus of the message should too, as with the ‘Slip! Slop! Slap!’ campaign36.

Additionally, the Australian public’s perception of the Cancer Council’s credibility had a positive impact on the reception of the ‘Slip! Slop! Slap!’ campaign. It has also given weight to the advice, training and resources which are used to communicate the campaign’s key message39. This creates a strong argument for a chronic wounds awareness campaign to be delivered by a reputable national governing body such as Wounds Australia, with a focus on evidence-based guidance and research building on the annual 'Wound Awareness Week' campaign.

Improved national leadership

Although the Australian Government has made an important first step in raising the profile of chronic wounds by funding the WMI CRC, much remains to be done in this area. National leadership and a strong political will are prerequisites for the collaborative implementation of evidence-based wound care, but these are still missing in Australia. We also need non-governmental national organisations such as Wounds Australia to intensify leadership.

Intensify and improve education and training in wound management

There is an urgent need for improvements in the education and training of healthcare professionals to increase the uptake of evidence-based practice. Forum participants agreed that an overhaul of education and training in a variety of sectors was required. Wound management should be a part of the routine training for healthcare professionals and incorporated into the national curriculum for all Australian medical, nursing and allied health schools, with ongoing comprehensive and accessible education available to all health care providers1. Monash University is currently the only University in the Southern Hemisphere that has postgraduate courses to master's level on wound care.

Education and training should also be provided to consumers; however, a recent Australian study found only 6% of chronic wound patients had training in self-management40. Education is necessary to allow patients the option of self-management, resulting in better outcomes and a reduced strain on funding40.

Increasing evidence-based practice training and upskilling that is affordable and accessible

Where innovative wound management upskilling programs have been implemented in Australia, there have been improvements in health care providers’ knowledge, confidence and skills41-44. One such program, focussed on DFUs, achieved significant improved knowledge, skill and competency among health care providers42, key factors in improving evidence-based clinical practice45. It also resulted in reductions in diabetes-related amputation rates46. Internationally, telehealth programs are used to create local content experts in primary care clinics in rural or remote areas47-49. A range of education modes should be available to meet the needs of all levels of providers in all settings including unregulated workers particularly in the residential aged care or remote setting, such as developed by the ‘Champions for Skin Integrity Program’50. Workforce capabilities growth, including plans for growth and recognition of wound care as a specialty, research opportunities, and skills sharing with community partners — as currently demonstrated by the University of the Sunshine Coast partnership with Blue Care wound services — is also recommended.

Incentivise the undertaking of further training and upskilling by primary health care workers

Healthcare professionals often rely on continuing professional development (CPD) to upskill, and for some it is a compulsory aspect of continued registration with their accrediting bodies51,52. However, with so many competing chronic diseases, wound care is not high on the CPD agenda. There is a need to assign CPD points to accredited wound management programs. Models that have proven to be effective for other chronic diseases could be replicated; these require practitioners to complete accredited activities in order to access Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) items53. Related recommendations are discussed in ‘Accreditation/Credentialling’.

Accreditation/credentialling

The use of highly trained wound specialists has been fundamental to the successful implementation of evidence-based chronic wound care54-56. The credentialling of wound specialists aims to ensure the quality of education, improves consistency across practice and promotes continuous quality improvement57. It also contributes to a clearer definition of the profession, with individuals meeting certain requirements before they are permitted to practise. Patients accessing credentialled healthcare professionals can feel confident the clinician is competent58.

There is a large number of professional organisations whose collaboration will be essential in accreditation and credentialling. However, we need a single accrediting body to be responsible for accreditation and setting wound care standards, or at the very least enable consistent collaboration between existing bodies. In the United States, the American Board of Wound Management (ABWM) performs credentialling for clinicians specialising in wound care59. While ABWM accreditation is not compulsory, it does create a high standard of care, and guarantees that knowledge of best practice care is continually assessed in line with current research. Such accreditation must be performed by the peak body (or bodies) in the area of practice.

Access to wound care products and services (improving physical access and financial support)

Concerns about access to wound products and services stem from two main issues — barriers to the physical access to service providers and products, and the financial barriers surrounding the need for costly ongoing care.

Improving physical access

Static and mobile wound management clinics are needed. There is a need to implement standard models of wound care nationwide, and to promote wound management in primary health care settings as a priority. Improving education, skills and financial incentives in primary care can prevent wounds, increase recognition of complications and reduce hospitalisations; indeed, one study showed that primary care could reduce the incidence of VLUs by 50% in 10 years60. Transdisciplinary outpatient clinics can improve wound healing rates at a reduced cost to the health care system61, and secondary-level wound specialty clinics would fill referral gaps in the community1. For those patients experiencing difficulties in accessing specialist care, telemedicine — including digital imaging wound assessment62-65 — may be particularly appropriate and effective66.

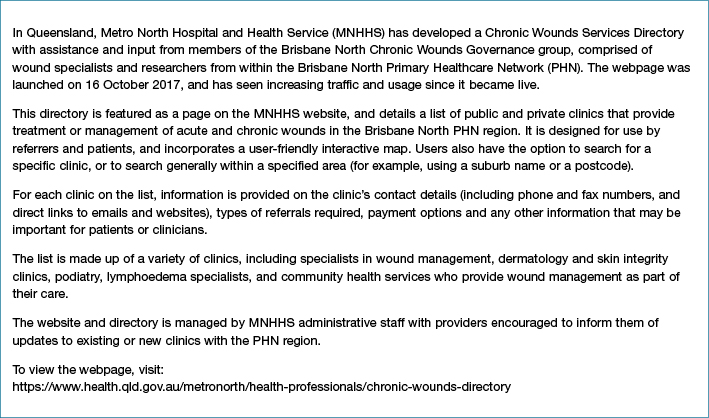

Mobile wound clinics and clinicians can also deliver wound management expertise to support residential aged care facilities, peripheral hospitals and regional/remote communities. For example: the Mobile Wound Care Program in Victoria67 recorded significant decreases in time to wound healing and treatment costs. The participating organisations also saw skills development with consequent improved workforce capacity to manage chronic wounds68. An online chronic wounds specialist services directory, such as the one developed by MNHHS (Box 2), is a user-friendly option for referrers and patients to locate information on local wound specialists including payment options.

Box 2: Chronic Wounds Directory

Financial support

The lack of reimbursement for wound management products means that people with chronic wounds outside of residential aged care facilities and the acute hospital system incur high personal out-of-pocket costs69. For many, the lack of access to affordable products could compromise care decisions. Given the strong evidence that guideline-based wound care is cost-saving and improves health outcomes in Australia, subsidising evidence-based treatments via government funding was identified as an important priority. Stakeholders recommended that a subsidy should be implemented through the MBS for the total cost of evidence-based wound care70,71.

With regard to VLU management in particular, specific MBS item numbers for the prescription of compression bandaging and for the time component of the wound management procedure are needed. In addition, new item numbers are needed to recognise wound management practitioners working in primary care, to reduce avoidable hospital presentations and admissions. Economic modelling estimated that the cost savings to the Australian government through reduced health service utilisation as a result of improved healing of venous leg ulcers, and ulcers and hospitalisations avoided, would be about A$1.2 billion over five years20.

Financial support remains a challenge, however, when health care budgets are already constrained. Health purchasers must identify opportunities for disinvestment in low-value care to redirect savings towards high-value services. A major obstacle is that health care spending has strong political implications. Innovative funding models — such as those developed for other chronic diseases, where a portion of tobacco taxation is used to fund effective prevention programs — are also needed to support government funding in the area of chronic wounds.

Another challenge is that we are seeking investment by the Australian government in primary health care while savings are perceived to be accrued predominantly in the acute sector. We recognise a need for a cohesive health system with better collaboration, with the vision that investing in primary care and prevention avoids downstream costs. We also need to incentivise cost-effective care and prevention within the MBS, moving from a fee-for-service to a more proactive service that incentivises positive patient outcomes.

Transdisciplinary, patient-centred care

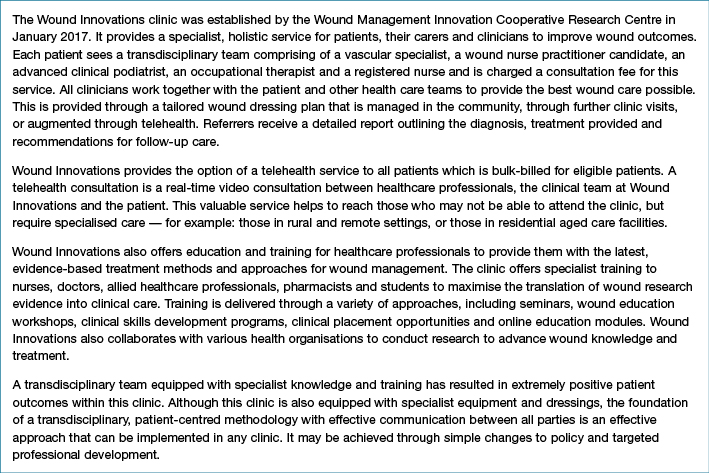

Stakeholders agreed that there was a need for improved coordination and communication between health care providers, patients and carers. There is evidence that when practitioners from different disciplines come together with a shared, patient-focussed goal, enhanced clinical outcomes can be achieved72. There are a range of professions that could be included in a patient’s wound care journey73. With such an approach, the team is interdependent and team members from different professions share responsibility and accountability for attaining positive patient outcomes72. An example of a fee for service wound clinic providing transdisciplinary, patient-centred care is provided in Box 3.

Box 3: Wound Innovations Clinic

The patient should be an active participant in all decisions about their care. In addition to costs, major contributors to patient non-adherence include a lack of understanding of wounds aetiology, pain and discomfort, aesthetic and cosmetic factors (such as unattractive and burdensome products), inability to bathe frequently, psychological issues, and poor relationships with health care providers74. Acknowledgement of these concerns can help tailor a plan that addresses them, thereby empowering the patient with a feeling of control72.

In a transdisciplinary approach the use of a ‘wound navigator’, or team leader who acts as an advocate for the patient, is important75. This person — often, the patient’s primary physician or initial practitioner — takes responsibility for the coordination of care services based on the patient's needs and treatment aims72. Organised interdisciplinary communication is essential; this may come in the form of in-clinic service provision, or via the development of electronic databases such as the Australian Government’s ‘My Health Record’ (My HR)76.

A relevant example of ongoing efforts to improve patient pathway access through policy change is the Metro South Health 'Value Based Wound Care — Chronic Venous Ulcer' project. This project aims to develop a framework for the provision of consistent evidence-based service delivery, clear referral pathways across Metro South Health, and policies and procedures to ensure uniform documentation, digital photography and follow-up of chronic wound and discharge planning. Although still in the planning stages, the development of an efficient and effective interface between general practice, community wound care services and acute services is expected to improve the coordination and navigation of services, and reduce hospital presentations and admissions. The primary driver for these changes is to improve patient outcomes and satisfaction, while also improving fiscal and clinical efficiency.

Surveillance and research needs

There is an urgent need for an improved understanding of the size of the chronic wounds problem and the population affected. Researchers and health policy makers often rely on outdated statistics on the prevalence of chronic wounds in Australia, but with population ageing and the obesity epidemic77-79, prevalence has probably increased in recent years. The effective implementation and evaluation of evidence-based chronic wound prevention and management strategies depend on the availability of reliable and comparable information.

Conducting a national wound prevalence survey that clearly identifies the magnitude of the problem is imperative. The development and rollout of a national wound registry, similar to the model developed for the Welsh Wound Registry and the United States Wound Registry, would provide a comprehensive electronic data collection system, and an opportunity for identifying the national scope of the wound burden and healing and cost outcomes1,80. It could also validly predict the likelihood of wound healing, facilitate comparative effectiveness research to identify patients needing advanced therapeutics, and inform future clinical trials80,81. However, for this to be achieved in the Australian context it would be necessary to overcome barriers to collaboration between sectors because of jurisdictional funding issues, sensitivities around the sharing of data, establishment costs and the challenge of service sustainability.

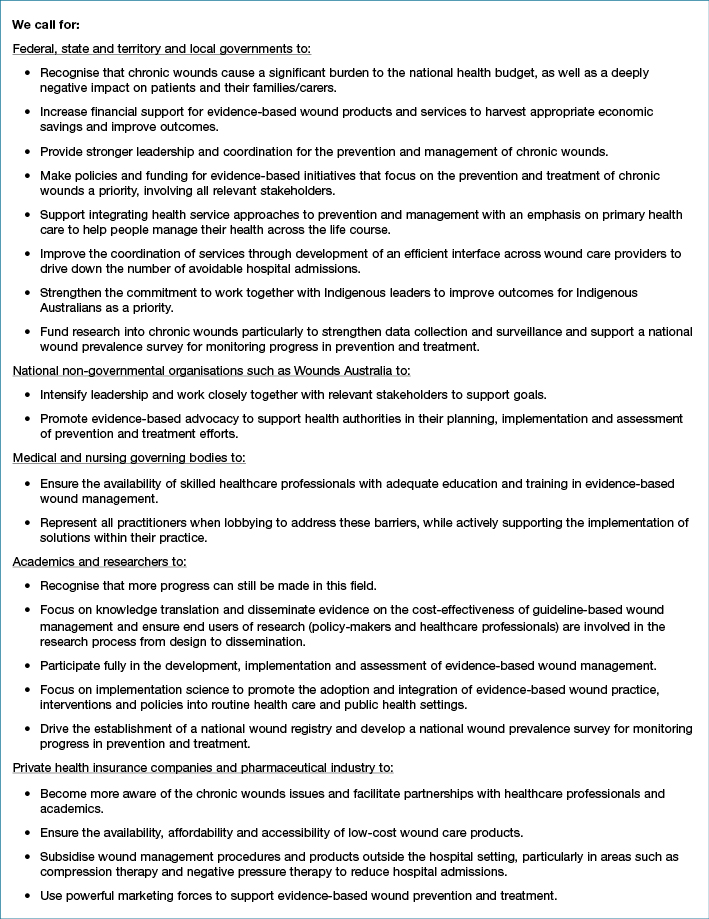

Chronic Wounds Solutions Collaborating Group call to action

We call for urgent and strengthened action from all stakeholders to respond to the chronic wound problem in Australia based on all the available evidence, and including the recommendations presented in this paper. Our call to action is summarised in Box 4.

Box 4: Chronic Wounds Solutions Collaborating Group Call to Action

Box 4 (continued): Chronic Wounds Solutions Collaborating Group Call to Action

Conclusion

This paper calls for a critical and sustained national effort to prevent and treat chronic wounds in Australia. Large health and economic gains can be achieved with modest investments in evidence-based strategies for the prevention and control of chronic wounds in Australia. This paper presents 17 stakeholder-driven recommendations to reduce the economic burden and improve clinical outcomes for patients with chronic wounds. All recommendations are interdependent — no single recommendation is strong enough on its own, and all need to be implemented to support sustainable improvements in wound care and patient outcomes across the care continuum.

Ultimately, all of our recommendations are underpinned by an urgent need for an increased awareness of the significance of chronic wounds, and the imperative that chronic wounds management be made a strategic objective for government. However, we all share responsibility and urgent action is needed not only by federal, state and local governments, but also non-governmental organisations, medical and nursing governing bodies, industry, healthcare professionals, academics and the public to address these recommendations if Australia is to reduce the significant preventable national burden of chronic wounds and improve patient outcomes. We have established the Chronic Wounds Solutions Collaborating Group to encourage, support and monitor action on the implementation of these recommendations to prevent and control chronic wounds in Australia. We provide evidence that this goal is achievable and call for a critical and sustained national effort to increase access to best-practice wound management, improve efficiency and value in health services and gain higher health benefits for all Australians with chronic wounds.

Acknowledgements

This Chronic Wounds Solutions Forum was organised by the Australian Centre for Health Services Innovation (AusHSI), with support from Queensland Government, Metro North Hospital and Health Service, Clinical Excellence Division, Brisbane North Primary Health Network, and the Wound Management Innovation Cooperative Research Centre (WMI CRC). The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Australian Government’s Cooperative Research Centres Program. The Wound Management Innovation Cooperative Research Centre (WMI CRC) received funding from the Australian Government, Curtin University of Technology, Queensland University of Technology, Smith & Nephew Pty Limited, Southern Cross University, University of South Australia, Wounds Australia Ltd, Blue Care, the Department of Health South Australia, the Department of Health and Human Services Victoria, Ego Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd, Metropolitan Health Service/Wounds West, Queensland Health, Royal District Nursing Service Limited as part of the Bolton Clarke Group, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Silver Chain Group Ltd, 3M Australia Pty LT, KCI Medical Australia Pty Ltd, Capital Health Network Pty Ltd, Mölnlycke Health Care Pty Ltd, Paul Hartmann Pty Ltd, Swinburne University of Technology, The University of Queensland, University of Melbourne, University of Tasmania and The University of Western Australia. The funding sources played no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Contributors

RP, RT and QC prepared the first draft. RP, RT, TP finalised the draft based on comments from other authors and reviewer feedback. RP, NG, KC, IG, MS conceived of the study and provided overall guidance. RT performed final statistical analyses. All other authors reviewed results, provided guidance, and reviewed the manuscript.

Declarations of interest

RP, RT, LB, TP, QC, DB are employed by the Queensland University of Technology with grant funding from the Wound Management Innovation Cooperative Research Centre (WMI CRC). JB is the Clinical Director at the Wound Innovations Clinic. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author(s)

Rosana E Pacella1,2, Ruth Tulleners1,2, Qinglu Cheng1,2, Ellen Burkett3, Helen Edwards4, Stephen Yelland5, David Brain1,2, John Bingley6, Peter Lazzarini7,8, Jason Warnock8, Louise Barnsbee1,2, Tamzin Pacella1,2, Kevin Clark9, Michele Smith10, Ian Griffiths6, Geoff Sussman11,12, Jaap van Netten7, Michelle Gibb13, Jodie Gordon14, Gillian Harvey15, Donna Hickling8, Xing Lee1,2, Bernd Ploderer16, Alison Vallejo17, Sharon Whalley18, and Nicholas Graves1,2 on behalf of the Chronic Wounds Solutions Collaborating Group.

1. Australian Centre for Health Services Innovation (AusHSI), Queensland University of Technology, QLD, Australia

2. School of Public Health and Social Work, Queensland University of Technology, QLD, Australia

3. Princess Alexandra Hospital

4. Faculty of Health, Queensland University of Technology

5. Bundall Medical Centre, Bundall, QLD, Australia

6. Wound Management Innovation Cooperative Research Centre

7. Queensland University of Technology

8. The Prince Charles Hospital, Metro North Hospital and Health Service

9. Metro North Hospital and Health Service

10. Brisbane North Primary Healthcare Network

11. Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Science, Monash University

12. Wounds Australia

13. Wound Specialist Services

14. Redcliffe Hospital, Metro North Hospital and Health Service

15. University of Adelaide

16. School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Queensland University of Technology

17. Blue Care

18. Wound Innovations Clinic, Wound Management Innovation Cooperative Research Centre (WMI CRC)

References

- Norman R, Gibb M, Dyer A et al. Improved wound management at lower cost: A sensible goal for Australia. Int Wound J 2016;13(3):303–16.

- Phillips T, Stanton B, Provan A, Lew R. A study of the impact of leg ulcers on quality of life: financial, social and psychologic implications. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;31:49–53.

- Kapp S, Santamaria N. The financial and quality-of-life cost to patients living with a chronic wound in the community. Int Wound J 2017;14(6):1108–19.

- Edwards H, Finlayson K, Courtney M, Graves N, Gibb M, Parker C. Health service pathways for patients with chronic leg ulcers: identifying effective pathways for facilitation of evidence based wound care. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13(1):86.

- Graves N, Finlayson K, Gibb M, O’Reilly M, Edwards H. Modelling the economic benefits of gold standard care for chronic wounds in a community setting. Wound Practice & Research 2014;22(3):163–8.

- KPMG Commissioned by Australian Wound Management Association. An economic evaluation of compression therapy for venous leg ulcers [Internet] 2013 [cited 11 December 2017]. Available from: http://www.awma.com.au/publications/kpmg_report_brief_2013.pdf.

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). National evidence-based guideline: Prevention, identification and management of foot complications in diabetes (Part of the guidelines on management of type 2 diabetes). Melbourne: Baker IDI Heart & Diabetes Institute; 2011 [cited 4 December 2017]. Available from: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/subject/Diabetes.

- Kruger A, Raptis S, Fitridge R. Management practices of Australian surgeons in the treatment of venous ulcers. ANZ J Surg 2003;73(9):687–91.

- Woodward M. Wound management by aged care specialists. Primary Intention 2002;10:70.

- Pacella R; AusHSI chronic wounds team. Chronic Wounds in Australia Issues Paper. Brisbane: Australian Centre for Health Service Innovation (AusHSI), Metro North HHS, Brisbane North PHN and Wound Management Innovation CRC, 2017 [cited 20 November 2017]. Available from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/118020/.

- Graves N, Zheng H. The prevalence and incidence of chronic wounds: A literature review. Wound Practice & Research 2014;22(1):4–12, 4–9.

- Graves N, Zheng H. Modelling the direct health care costs of chronic wounds in Australia. Wound Practice & Research 2014;22(1):20–4, 6–33.

- de Carvalho M. Comparison of outcomes in patients with venous leg ulcers treated with compression therapy alone versus combination of surgery and compression therapy: A systematic review. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(1):42.

- Mauck K, Asi N, Elraiyah TA et al. Comparative systematic review and meta-analysis of compression modalities for the promotion of venous ulcer healing and reducing ulcer recurrence. J Vasc Surg 2014;60(S2):S71–S90.

- Nelson E, Bell-Syer, SEM. Compression for preventing recurrence of venous ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014(9):CD002303.

- O’Meara S, Cullum N, Nelson EA, Dumville JC. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:CD000265.

- Ragnarson Tennvall G, Apelqvist J. Prevention of diabetes-related foot ulcers and amputations: a cost-utility analysis based on Markov model simulations. Diabetologia 2001;44(11):2077–87.

- International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot. 2007 [cited 4 December 2017]. Available from: http://www.iwgdf.org.

- Ortegon M, Redekip W, Niessen L. Cost-effectiveness of prevention and treatment of the diabetic foot: A Markov analysis. Diabetes Care 2004;27(4):901–7.

- Cheng Q, Gibb M, Graves N, Finlayson K, Pacella RE. Cost-effectiveness analysis of guideline-based optimal care for venous leg ulcers in Australia. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):421.

- Padula W, Mishra M, Makic M, Sullivan P. Improving the quality of pressure ulcer care with prevention a cost-effectiveness analysis. Medical Care 2011;49(4):385–92.

- The World Café Community Foundation. The World Café 2018 [cited 25 January 2018]. Available from: http://www.theworldcafe.com/about-us/.

- SurveyMonkey Inc. San Mateo, California, USA2018 [cited 18 January 2018]. Available from: www.surveymonkey.com.

- Beaglehole R, Ebrahim S, Reddy S, Voûte J, Leeder S; Chronic Disease Action Group. Prevention of chronic diseases: a call to action. Lancet 2007;370(9605):2152–7.

- Kapp S, Santamaria N. Chronic wounds should be one of Australia’s National Health Priority Areas. Australian Health Review, 2015.

- Colagiuri S, Colagiuri R, Ward J. National Diabetes Strategy and Implementation Plan. Canberra: Diabetes Australia, 1998.

- National Health Priority Action Council (NHPAC). National Service Improvement Framework for Diabetes. Canberra: Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing, 2006.

- d’Espaignet E, Bulsara M, Woldenden L, Byard R, Stanley F. Trends in sudden infant death syndrome in Australia from 1980 to 2002. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 2008;4:83–90.

- Linacre S. Australia’s Babies: Australian Social Trends 2007 (Catalogue No. 4102.0). Canberra: Bureau of Statistics, 2007.

- Bray J, Johnson R, Trobbiani K, Mosley I, Lalor E, Cadilhac D. Australian public’s awareness of stroke warning signs improves after national multimedia campaigns. Stroke 2013;44(3540–3543).

- Bray J, Mosley I, Bailey M, Barger B, Bladin C. Stroke public awareness campaigns have increased ambulance dispatches for stroke in Melbourne, Australia. Stroke 2001;42:2154–7.

- Bray J, Straney L, Barger B, Finn J. Effect of public awareness campaigns on calls to ambulance across Australia. Stroke 2015;2015(46):1377–80.

- Dessaix A, Maag A, McKenzie J, Currow D. Factors influencing reductions in smoking among Australian adolescents. Public Health Research and Practice 2016;26(1):1–4.

- Wakefield M, Coomber K, Durkin S et al. Time series analysis of the impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence among Australian adults, 2001–2011. Bull World Health Organ 2014;92(6):413–22.

- Hurley S, Matthews J. Cost-effectiveness of the Australian national tobacco campaign. Tobacco Control 2008;16(6):379–84.

- Aitken J, Youlden D, Baade P, Soyer H, Green A, Smithers B. Generational shift in melanoma incidence and mortality in Queensland, Australia, 1995–2014. Int J Cancer 2017.

- Cancer Council Victoria. SunSmart program, 2017.

- Shih S, Carter R, Heward S, Sinclair C. Skin cancer has a large impact on our public hospitals but prevention programs continue to demonstrate strong economic credentials. Aust N Z J Public Health 2017;41(4):371–6.

- Montague M, Borland R, Sinclair C. Slip! Slop! Slap! and SunSmart, 1980–2000: Skin Cancer Control and 20 Years of Population-Based Campaigning. Health Education & Behaviour 2001;28(3):290–305.

- Kapp S, Santamaria N. How and why patients self-treat chronic wounds. Int Wound J 2017;14(6):1269–75.

- Lazzarini P, Mackenroth E, Rego P et al. Is simulation training effective in increasing podiatrists’ confidence in foot ulcer management? J Foot Ankle Res 2011;4(1):16.

- Lazzarini P, Ng V, Rego P, Kuys S, Jen S. Foot ulcer simulation training (FUST): Are podiatrists FUST with long-term clinical confidence? J Foot Ankle Res 2013;6(S1):22.

- Ng V, Lazzarini P, Rego P, Cornwell P. Is foot ulcer simulation training (FUST) really effective? Participants’ supervisors speak out. J Foot Ankle Res 2013;6:24.

- Damien C, Reed L, Kinnear E, Lazzarini P. Evaluating the impact of high risk foot training on undergraduate podiatry students. J Foot Ankle Res 2013;O7.

- Lazzarini P, O’Rourke S, Russell A, Derhy P, Kamp M. Standardising practices improves clinical diabetic foot management: the Queensland Diabetic Foot Innovation Project, 2006–09. Aust Health Rev 2012;36(1):8–15.

- Lazzarini P, O’Rourke S, Russell A, Derhy P, Kamp M. Reduced incidence of foot-related hospitalisation and amputation amongst persons with diabetes in Queensland, Australia. PLoS One 2015;e0130609.

- Anderson D, Zlateva I, Davis B et al. Improving Pain Care with Project ECHO in Community Health Centers. Pain Med 2017;18:1882–9.

- Lopez M, Baker E, Milbourne A, Gowen Rea. Project ECHO: A Telementoring program for Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment in Low-Resource Settings. J Glob Oncol 2017;3(4):658–65.

- Colleran K, Harding E, Kipp B et al. Building capacity to reduce disparities in diabetes: Training community health workers using an integrated distance learning model. Diabetes Education 2012;38:386–96.

- Edwards H, Chang A, Finlayson K. Creating champions for skin integrity: final report. Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology, 2010.

- Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia. Registration standard: Continuing professional development, 2016.

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. QI & CPD Program: 2017–19 triennium handbook for general practitioners, 2016.

- General Practice Mental Health Standards Collaboration (GPMHSC). Mental health education standards 2014–2016: A handbook for GPs. Melbourne: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2013.

- Ghauri A, Taylor M, Deacon J et al. Influence of a specialized leg ulcer service on management and outcome. Br J Surg 2000;87:1048–56.

- Harrison M, Graham I, Lorimer K, Friedberg E, Pierscianowski T, Brandys T. Leg-ulcer care in the community, before and after implementation of an evidence-based service. Can Med Assoc J 2005;172:1447–52.

- Zulkowski K, Ayello EA, Wexler S. Certification and education: Do they affect pressure ulcer knowledge in nursing? Adv Skin Wound Care 2007;20(1):34–8.

- Blouin D, Tekian A. Accreditation of medical education programs: Moving from student outcomes to continuous quality improvement. Acad Med 2017.

- Boulet J, van Zanten M. Ensuring high-quality patient care: the role of accreditation, licensure, speciality certification and revalidation in medicine. Medical Education 2014;48:75–86.

- American Board of Wound Management. Certification Statistics, 2017.

- Yelland S. General practice and primary care: making a difference at the coalface of wound management in Australia. Wound Practice & Research 2014;22(2):104–7.

- Müller M, Morris K, Coleman K. Venous leg ulcer management: The Royal Brisbane Hospital leg ulcer clinic experience. Primary Intention 1999;7(4):162–6.

- Halstead LS, Dang T, Elrod M, Convit RJ, Rosen MJ, Woods S. Teleassessment compared with live assessment of pressure ulcers in a wound clinic: a pilot study. Adv Skin Wound Care 2003;16:91–6.

- Murphy RX, Bain MA, Wasser TE, Wilson E, Okunski WJ. The reliability of digital imaging in the remote assessment of wounds — Defining a standard. Ann Plast Surg 2006;56:431–6.

- Salmhofer W, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Gabler G et al. Wound teleconsultation in patients with chronic leg ulcers. Dermatology 2005;210(3):211–7.

- Lazzarini P, Clark D, Mann R, Perry V, Thomas D, Kuys S. Does the use of store-and-forward telehealth systems improve outcomes for clinicians managing diabetic foot ulcers? A pilot study. Wound Practice & Research 2010;18:164–72.

- Gray LC, Armfield NR, Smith AC. Telemedicine for wound care: Current practice and future potential. Wound Practice & Research 2010;18(4):158–63.

- Walker J, Cullen M, Chambers H, Mitchell E, Steers N, Khalil H. Identifying wound prevalence using the Mobile Wound Care program. Int Wound J 2014;11(3):319–25.

- Khalil H, Cullen M, Chambers H, Steers N, Mitchell E, Carroll M. Mobile Wound Care Project — Third year and final report. Victoria, Australia: School of Rural Health, Monash University, 2013.

- Smith E, McGuiness W. Managing venous leg ulcers in the community: personal financial cost to sufferers. Wound Practice & Research 2010;18(3):134–9.

- Bergin S, Alford J, Allard B et al. A limb lost every 3 hours: can Australia reduce lower limb amputations in people with diabetes? Med J Aust 2012;197:4.

- Lazzarini P, Gurr J, Rogers J, Schox A, Bergin S. Diabetes foot disease: the Cinderella of Australian diabetes management? J Foot Ankle Res 2012;5(1):24.

- Moore Z, Butcher G, Corbett L, McGuiness W, Snyder R, van Acker K. AAWC, AWMA, EWMA Position Paper: Managing Wounds as a Team. J Wound Care 2014;23(Sup5b):1–38.

- Gottrup F. A specialized wound-healing center concept: importance of a multidisciplinary department structure and surgical treatment facilities in the treatment of chronic wounds. Am J Surg 2004;187:38S–43S.

- Brown A. Implications of patient shared decision-making on wound care. Wound Care 2013;June:S26–S32.

- Abrahamyan L, Wong J, Pham B, al e. Structure and characteristics of community-based multidisciplinary wound care teams in Ontario: An environmental scan. Wound Repair Regen 2015;23:22–9.

- Australian Digital Health Agency. My Health Record Statistics, 2017.

- Anderson K, Hamm RL. Factors that impair wound healing. J Am Coll Clin Wound Spec 2012;4(4):84–91.

- Australian Government. A picture of overweight and obesity in Australia. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017.

- Australian Government. Older Australia at a glance. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2017.

- Horn S, Fife C, Smout R, Barrett R, Thomson B. Development of a wound healing index for patients with chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2013;21(6):823–32.

- Harding K. Wound registries — a new emerging evidence resource. Int Wound J 2011;8(4):325.