Volume 26 Number 4

Exploring the impact of incontinence-associated dermatitis on wellbeing

Alicia Spacek, Ann Marie Dunk and Dominic Upton

Keywords Incontinence-associated dermatitis, wellbeing.

Abstract

Introduction: Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) is caused by chemical and physical irritation from excrement in contact with skin. Though IAD is a risk factor for pressure injury development and can occur simultaneously, inconsistencies and gaps within the literature remain.

Background: Psychosocial assessments are essential to holistic assessment of a person with a wound to ensure positive impacts are maximised and the negative influence on wound healing minimised. However, there has been little discussion on the psychosocial impacts of IAD on the patient, hence this literature review.

Methods: A systematic literature search was undertaken using CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE and PubMed databases to explore the link between wellbeing and IAD. A comprehensive search was employed and 12 articles were included in the review.

Results: The IAD literature focused on treatments briefly inferring impact to the patient, whilst omitting psychosocial assessments and patient involvement. The few mentions of IAD impact on patient wellbeing were generalised from the incontinence literature. Two articles recommended the need for patient involvement and exploring the impact of IAD.

Conclusion: Research is needed to investigate the psychosocial factors which impact on patients with IAD wounds, along with the role wellbeing may play in wound healing in adults with IAD.

Introduction

Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) is a form of moisture-associated skin damage (MASD) caused by persistent or chronic skin exposure to urine and/or faecal incontinence and moisture1-5. Excrement damages the outermost skin layer, the stratum corneum’s lipid barrier function, through increasing skin pH2-6. This results in greater moisture permeability and hyper-hydration from the skin surface down3,4. The resulting maceration weakens the skin structure, predisposing it to further chemical and physical injury, especially friction and shear2,4-6.

Though rates of IAD vary depending on the environment, prevalence and incidence rates are wide and range from 5.6% to 50%, and 3.4% to 25%, respectively across a variety of settings6. IAD can occur wherever skin contacts with excretory products, but is commonly found on the genitals, groin, sacrum, peri-anal/perineum, buttocks, thigh and abdomen2,6. Skin damage presentations range from intact red, oedematous skin, to a rash, and superficial skin loss, which can lead to complete denudation and even deep wounding2,4-6.

IAD risk increases from urinary incontinence, to double incontinence and is further elevated with loose stools, which are especially corrosive to skin4,7. Risk factors include critical illness, restricted mobility, cognitive impairment, decreased independence with activities of daily living, malnutrition, fever, medications, conditions which predispose to poor skin integrity and, of course, incontinence 2,6,7. Moreover, IAD not only predisposes patients to infection but is also a significant individual risk factor for pressure injury (PI) formation3,6-8-10. Though evidence grows, the numerous gaps in the literature require further review and understanding of the impact IAD has upon the patient. In this respect, clinicians' knowledge can be improved, as can the resultant care for those with IAD2,5.

Background

The World Health Organization acknowledges three overarching psychosocial factors being “physical, mental, and social”, which impact on the overall health and wellbeing of an individual11,p.1. These factors theme in both general and moreover in wound-specific quality of life (QoL) and wellbeing (WB) models due to the demonstrated positive and negative implications of these factors on wound healing11-16. Indeed, there is growing evidence of positive psychological or ‘protective’ factors offsetting the well-versed negative consequences or stressors on wounds13. Wound healing correlates with these three psychosocial factors and have important implications for enhancing patient wound care treatment and results12-16.

The focus on patient QoL and WB are especially noted in the Standards for Wound Prevention and Management published by Wounds Australia in 2016, which endorse this holistic and comprehensive patient approach inclusive of a variety of psychosocial assessments for “well-being, quality of life, social and wound impact … for specific health populations”17,p.19. However, the influence of psychosocial WB factors, along with an understanding of their relevance to the patient with IAD in equipping the clinician in the practice of holistic wound care is sadly lacking13,16,18. As such, a literature review was conducted to explore the impact of adult IAD on wellbeing.

Method

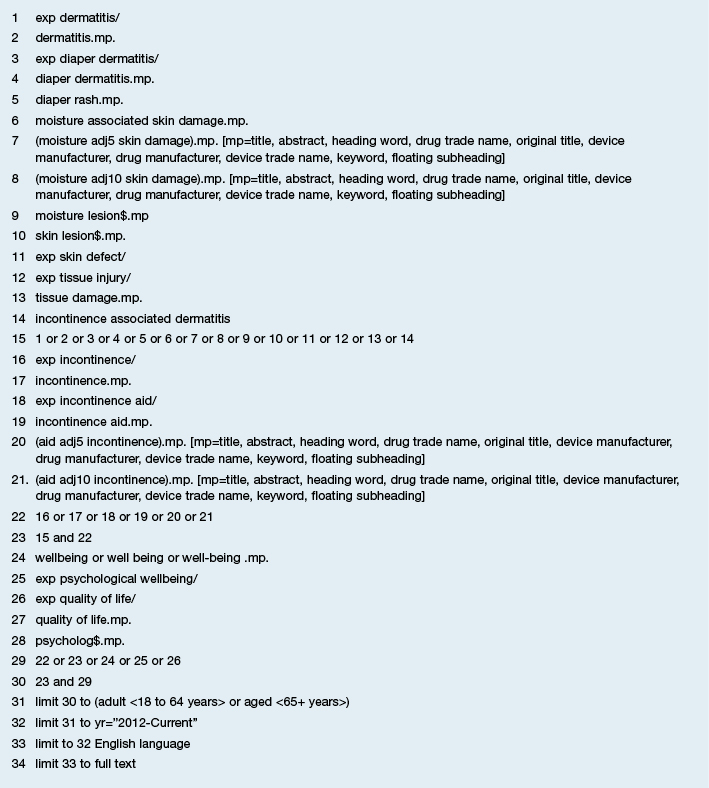

In 2017, a literature search was undertaken using Embase (EBSCOhost), Medline (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), and PubMED databases. A comprehensive search strategy was employed utilising both Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords (Figure 1). The IAD search terms were then searched with incontinence and psychology-related terms using the Boolean “AND” function. The search was limited to adults 18 years and above, published from 2012 to 2017, written in English and limited to full text articles. Titles and abstracts were sorted to ensure relevancy to both incontinence and the associated skin damage, which resulted in a final 25 papers. Articles were then excluded if they did not mention quality of life, wellbeing or psychological factors in context to the patient with IAD. PEARL searching included one article which met the inclusion from the Wounds International website. Finally, a total of 12 articles met this criteria and were included in the literature review.

Figure 1: Search strategy

Results

Physical wellbeing

Emotional responses to the physical symptoms of wounding are demonstrated to impact on the physical healing of a wound13,15,16. In spite of this, all of the IAD articles focused predominately on the physical consequences of the wound such as diagnosis, treatment and pain, but excluded the patient perspective and emotional reaction to these factors. Many of the studies narrated the physical impact of IAD18-21. Pain was the most common physical symptom listed18-20,22-25, as well as discomfort descriptors18,23-25, and resulting sleep disturbance6,18. In addition, pain was noted as an individual risk factor for IAD6. The lack of original research contribution by these articles to explore and support the physical experience of the patient with IAD makes them of little contribution to this review.

Despite this, only one study demonstrated pain assessment within the methodology through a longitudinal study design comparing IAD and PIs prevalence and related factors22. The study by Long et al. included questioning of patients for responses to pain-related symptoms, without mention of a validated pain assessment tool22. Further, questioning on a list of negative symptoms, namely “tingling, itching, burning and pain” in specific sites of their body, required only yes/no answers from the patients and assumed these were the only negative sensations of IAD22,p.319. This demonstrated poor appreciation of the subjective experience of patients with IAD and PIs. Another observational study by Clarke-O’Neill et al., which also used a non-validated IAD assessment tool, examined the effect of four different incontinence pads on skin outcomes25. The results showed no difference in skin injuries on patients, despite the differing incontinence aids used and also noted difficulties in diagnosing IAD due to the presence of multiple other skin discrepancies, which could be associated to the assessment tool25. It was remarkable that within the initial literature review in discussing that “the participant’s overall opinion rating is perhaps the most important” in incontinence aid research was highlighted, but the study failed to incorporate this measure into the study design25,p.662.

An intervention review by Beeckman et al. demonstrated rigorous methodology in reviewing the small number of research articles which met the inclusion criteria for IAD prevention and treatment10. The authors acknowledged a small amount of low to moderate evidence to support skin care methods being due to numerous factors10. A number of the patient-specific outcomes had no data found, inclusive of treatment satisfaction, pain from IAD and pain associated with treatment methods. The authors further called for the development of a universal list of outcomes which are important for patients that will additionally guide researchers in future studies. Thus a patient-centred approach to future IAD study design measuring subjective IAD patient experiences is required.

The Beeckman et al. paper about the global expert panel provides a comprehensive review of IAD, in the absence of any thorough care guideline on IAD6. The document is strengthened by the in-depth and supported discussions of current knowledge and identification of gaps to promote IAD research6. Noted within were clinician difficulties differentiating IAD from PI and other MASD and that IAD and PI can co-exist, with diagnosis relying on clinician education and accurate wound assessment and treatment6. Further noted were low validity and reliability of results, limiting credibility of the evidence for the treatment and management with further research and consolidation of knowledge required6. This gives clear cause for patients to potentially feel uneasy or stressed over IAD and the treatments and warrants investigation into their subjective experience with IAD.

Social wellbeing

Social factors are evidenced to impact on wound healing rates13,15,26. However, the IAD literature provides overall little evidence into the social consequences of IAD, despite IAD patients being found in a variety of social settings6,10,22,25. Negative patient feelings are reported, such as low self-esteem23, embarrassment20,23-24, being alone18 and shame20. Social evasion is stated to result due to the stigmatisation of having IAD20,23. References for the impact of social factors on IAD are sourced largely from the incontinence literature6,23-24, or are wholly unsupported23,27. Thus, the social factors are at best a generalisation to patients who have both injured skin as well as incontinence. There was no research amongst the IAD population examining the social implication of the condition, on their person or their family and friends, in either a QoL or WB focus. Additionally, although the gap of social impact of IAD was identified in one article21, no specific recommendations to explore social experience and IAD were made by the authors, further highlighting the need for better appreciation of the patient perspective, comprehension of the social experience of patients with IAD to tailor holistic wound care to patient needs.

On the other hand, Edwards et al. conducted a rigorous randomised control trial on community patients with venous leg ulcers, which saw patients distributed between the Lindsay leg club intervention group, which provided a social support group with other patients with venous leg ulcers, and the control group26. Consistent treatment controls as well as numerous validated and reliable psychosocial and pain assessment tools were used in the data collection, further verifying the results observed26. Statistically significant improvements were noted in the intervention arm for pain, morale and healing rates, amongst others, supporting the efficacy of positive social factors improving wound healing outcomes26.

Mental wellbeing

Individual psychological factors such as poor mental health, depression or stress are demonstrated to impact negatively on skin injury healing rates16,28. Broad statements within the IAD literature were found on the impact on patient psychological health6,10,19,27, but only one mentioned the impact on patient mental state20. Bianchi and Segovia-Gomez stated faecal incontinence and the consequential skin injury as having a detrimental psychological impact on the patient’s “dignity, causing embarrassment and stigma” as well as anxiety20,p.18. Feelings of depression and distress are broadly applied statements as consequences of IAD19,22, and again were derived solely from the incontinence literature18,23. Other feelings of frustration, anger and even helplessness are further suggested by authors, with no evidence to corroborate these negative patient emotions23. All these broad statements are not verified as the intervention review demonstrated no findings on the impact of IAD on patient psychology10. Thus, there is no direct evidence within the IAD literature to determine the impact of IAD on the mental status of the patient.

In contrast, the wound literature provides further proof of the mental impact of wounding on patients. Walburn et al. conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis, providing quantifiable results from 17 of 22 studies on varying wound types and supports that stress over extended periods of time negatively hinders wound healing16. The enormous practical and statistical relevance of these findings was likened similarly to the proven impact diabetes has on wound healing outcomes16. They concluded that future research needs to focus on factors which mediate and moderate stress to further establish an understanding between wound healing and the stress response16. This supports the legitimacy and momentum of wellbeing in wound healing science and the relevance to wound types that remain yet to be explored, such as IAD.

Quality of life

Numerous articles identified IAD impacting on patient QoL by linage to the incontinence literature6,18,22,23,25. These results thus are generalised to IAD patients, making application to those with IAD indirect at best and difficult to apply as there was little mention of skin injury. Secondly, IAD can result from an acute or chronic incontinence6,20 and thus makes the negative psycho-social experiences of patients with most commonly chronic incontinence less applicable to the IAD population. Of interest, only two studies attempted to assess IAD patient QoL10,29. Whilst one study remains yet to report study protocol findings29, most notably the intervention review showed there was no available data to justify any influence on QoL from IAD or its treatments, despite it being suggested in the literature reviewed in this paper10. Furthermore, only two articles recommended the need for exploration into patient experience6,10, and only one article actually used wound psychology literature alongside that of incontinence to substantiate the negative consequences of IAD on the person21. The advantage of this article in acknowledging the incontinence and wound research is that it more fully encompasses the IAD factors of incontinence and wounding. Research is required that examines both the positive and negative aspects to the patient IAD experience.

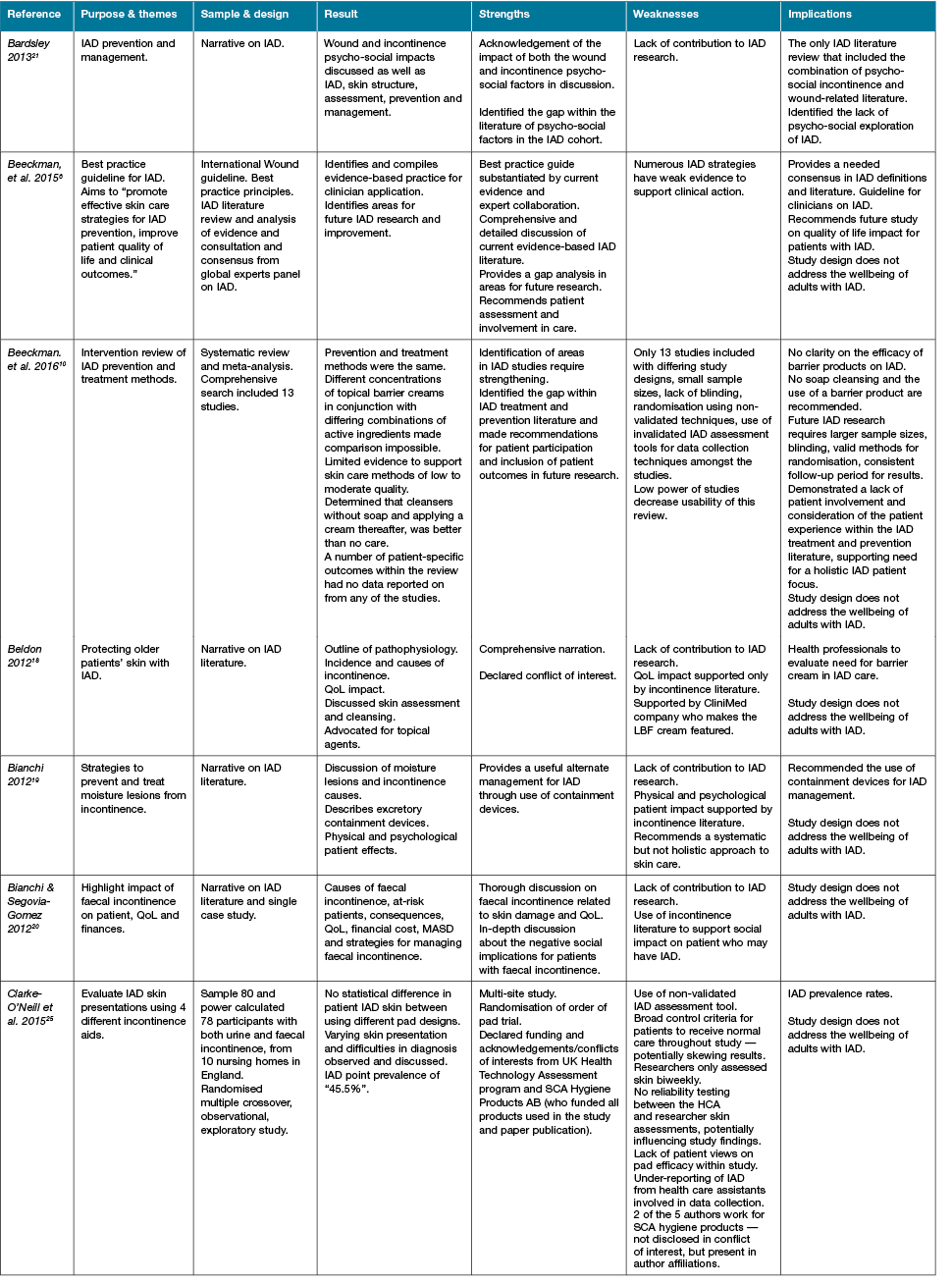

Table 1: Literature review

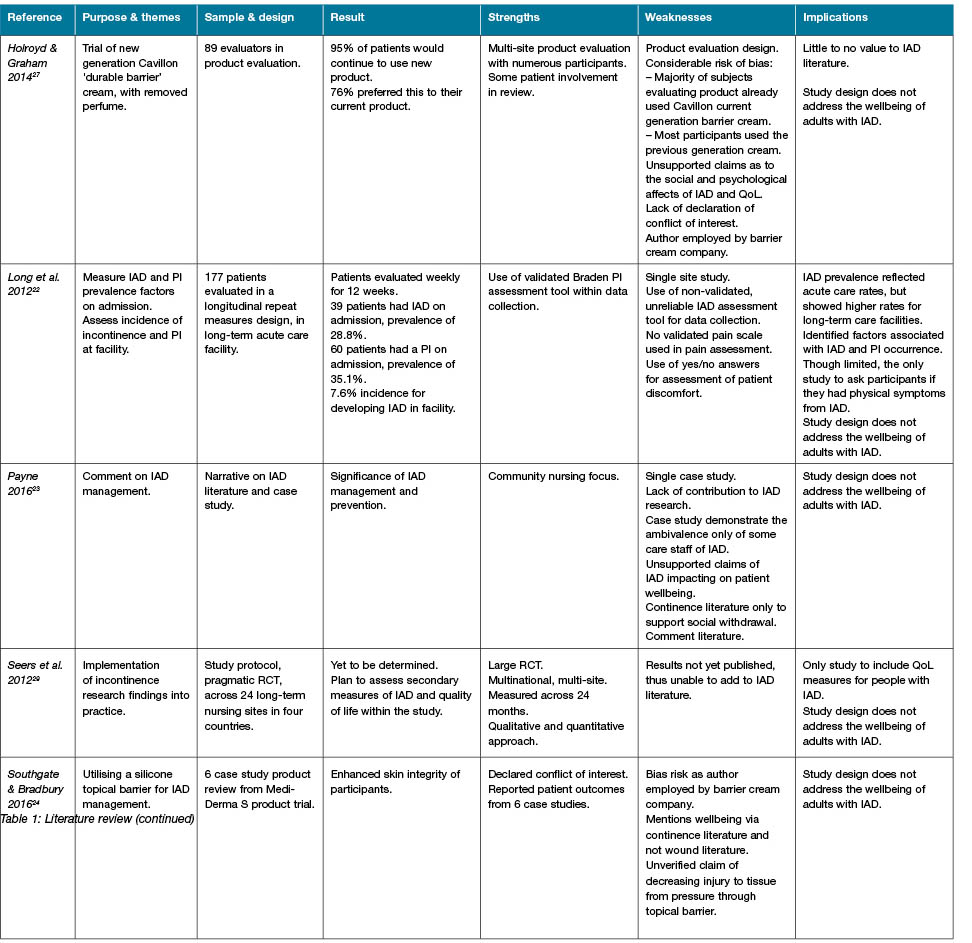

Table 1: Literature review (continued)

Wellbeing

As evidenced, none of the article designs evaluated wellbeing in adults with IAD. Four of the five articles which mentioned wellbeing, did so in the introduction or summary and in broad statement applying only the negative patient consequences of IAD19,20,23. This confirms the incorrect application of the wellbeing definition and confusion with QoL13. The lack of consideration of the patient experience and participation throughout the IAD literature is in direct contradiction of the holistic focus and recommendations of wound clinician guidelines to involve the patient in their care12,14. Moreover, patient involvement has demonstrated improved patient outcomes12, and the resultant lack of patient participation is detrimental to the treatment and management techniques of IAD. IAD academic literature should demonstrate incorporating best practice, holistic care, inclusive of psychosocial assessments and role model this so as to promote best practice amongst wound clinicians caring for patients with IAD. Furthermore, exploration of wellbeing in IAD is required to optimise patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Despite evidence to support the significance of psychological factors on wound healing, the IAD literature remains focused on the wound and skin injury itself and inconsistently acknowledges vital gaps on the topic such as patient participation and patient-formulated outcome measures. The authors noted a lack of implementation of psychosocial assessments within study design, further demonstrating a poor holistic focus. Additionally, there was no direct evidence of the impact of psychosocial factors on QoL, let alone on IAD patient wellbeing. The evidential lack of insight into the negative as well as positive patient experience in IAD limits clinician understanding and guidance in delivering holistic patient-centred care to this vulnerable cohort. Future exploration into the IAD patient experience, emotional response and positive coping strategies to these challenges, in particular, are warranted, to enhance clinician understanding and patient outcomes.

Recommendations include greater patient involvement and holistic focus in IAD enquiry through the assessment of psychosocial factors in future research design. The discussion of psychosocial factors needs to be broadened to incorporate both incontinence and wound specialties for IAD applications. Finally, future exploration of the wellbeing of adults with incontinence-associated dermatitis is required.

Conflict of Interest

No author conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Author(s)

Alicia Spacek*

RN, BNurs

Nurse Educator, Neurology, Stroke & Infectious Diseases

Canberra Hospital, ACT Health, Australia

Email Alicia.spacek@act.gov.au

Ann Marie Dunk

RN, BHthSc (Nurs), MNurs(Research)

Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Canberra

Clinical Nurse Consultant, Tissue Viability Unit, Canberra Hospital, ACT Health, Australia

Dominic Upton

BSc (Hons), MSc, PhD, FBPsS, FHEA, CSsi

Dean, College of Health and Human Sciences, Charles Darwin University, NT, Australia

* Corresponding author

References

- Black JM, Gray M, Bliss DZ et al. MASD Part 2: Incontinence-associated dermatitis and intertriginous dermatitis: a consensus. J Wound, Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011;38(4):359–370.

- Beeckman D, Van Damme N, Van den Bussche K, De Meyer D. Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD): an update. Dermatol Nurs 2015;14(4):32–36.

- Beeckman D, Van Lancker A, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of incontinence- associated dermatitis, incontinence, and moisture as risk factors for pressure ulcer development. Res Nurs Health 2014;37:204–218. DOI: 10.1002/nur.21593.

- Woo KY, Beeckman D, Chakravarthy D. Management of moisture-associated skin damage: A scooping review. Adv Skin Wound Care 2017;30(11):494–491.

- Conley P, McKinsey D, Ross O, Ramsey A, Feeback J. Does skin care frequency affect the severity of incontinence-associated dermatitis in critically ill patients? Nursing 2014;44(12):27–32. DOI:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000456382.63520.24.

- Beeckman D, Campbell J, Campbell K et al. Proceedings of the Global IAD expert panel. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: moving prevention forward. Wounds Int 2015. Available from: https://www.woundsinternational.com/resources/details/incontinence-associated-dermatitis-moving-prevention-forward

- Beeckman D, Van den Bussche K, Alves P et al. Towards an international language for incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD): design and evaluation of psychometric properties of the Ghent Global IAD Categorisation Tool (GLOBIAD) in 30 countries. Br J Dermatol 2018. DOI:10.1111/bjd.16327.

- Gray M, Giuliano KK. Incontinence-associated dermatitis, characteristics and relationship to pressure injury. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2018;45(1):63–67. DOI: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000390.

- Gray M, Black JM, Baharestani MM et al. Moisture-associated skin damage overview and pathophysiology. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2011;38(3):233–241. DOI: 10.1097/WON.0b013e318215f798.

- Beeckman D, Van Damme N, Schoonhoven L et al. Interventions for preventing and treating incontinence-associated dermatitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;11:CD011627. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011627.pub2.

- World Health Organization. Measuring Quality of Life; 1997. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/68.pdf

- Gray D, Boyd J, Carville K et al. Effective wound management and wellbeing for clinicians, organisations and industry. Wounds Int 2012;2(2):21–25. Available from: https://www.woundsinternational.com/resources/details/effective-wound-management-and-wellbeing-for-clinicians-organisations-and-industry

- Upton D, Upton P. Psychology of Wounds and Wound Care in Clinical Practice. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015.

- International Consensus Document. Optimising wellbeing in people living with a wound. An expert working group review. Wounds Int 2012. Available from: https://www.woundsinternational.com/resources/details/international-consensus-optimising-wellbeing-in-people-living-with-a-wound

- Broadbent E, Koschwanez HE. The psychology of wound healing. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012;25:135–140. DOI:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32834e1424.

- Walburn J, Vedhara K, Hankins M, Rixon L, Weinman J. Psychological stress and wound healing in humans; A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2009;67:253–271. DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.04.002.

- Wounds Australia. Standards for Wound Prevention and Management. 3rd edn. Osborne Park, WA: Cambridge Media; 2016.

- Beldon P. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: protecting the older person. Br J Nurs 2012;21(7):402–407.

- Bianchi J. Causes and strategies for moisture lesions. Nurs Times 2012;108(5):20–22.

- Bianchi J, Segovia-Gomez T. The dangers of faecal incontinence in the at risk patient. Wounds Int 2012. Available from: https://www.woundsinternational.com/resources/details/expert-commentary-the-dangers-of-faecal-incontinence-in-the-at-risk-patient

- Bardsley A. Prevention and management of incontinence-associated dermatitis. Nurs Stand 2013;27(44):41–46.

- Long MA, Reed LU, Dunning K, Ying J. Incontinence-associated dermatitis in a long-term acute care facility. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2012;39(3):318–327. DOI: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3182486fd7.

- Payne D. Not just another rash: management of incontinence-associated dermatitis. Br J Community Nurs 2016;21(9):434–440. DOI:10.12968/bjcn.2016.21.9.434.

- Southgate G, Bradbury S. Management of Incontinence-associated dermatitis with a skin barrier protectant. Br J Nurs 2016;25(9):20–29.

- Clarke-O’Neill S, Farbort A, Lagerstedt ML, Cottenden A, Fader M. An exploratory study of skin problems experienced by uk nursing home residents using different pad designs. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(6):621–631. DOI: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000177.

- Edwards H, Courtney M, Finlayson K, Shuter P, Lindsay E. A randomised controlled trial of a community nursing intervention: improved quality of life and healing for clients with chronic leg ulcers. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:1541–1549. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02648.x.

- Holroyd S, Grahem K. Prevention and management of incontinence-associated dermatitis using a barrier cream. Br J Community Nurs 2014;19(12):32–38. DOI: 10.12968/bjcn.2014.19.Sup12.S32.

- Vedhara K, Miles NV, Wetherell MA et al. Coping style and depression influence the healing of diabetic foot ulcers: observational and mechanistic evidence. Diabetologia 2010;53:1590–1598. DOI: 10.1007/s00125-010-1743-7.

- Seers K, Cox K, Crichton NJ et al. FIRE (Facilitating Implementation of Research Evidence): a study protocol. Implement Sci 2012;7(25):1–11.