Volume 28 Number 2

WHAM Evidence Summary: Low friction fabric for preventing pressure injuries

Emily Haesler

For referencing Haesler E. Evidence Summary: Low friction fabric for preventing pressure injuries. Wound Practice and Research 2020; 28(2):97-98.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wpr.28.2.97-98

Clinical question

What is the best available evidence for using low friction fabrics to prevent pressure injuries (PIs) in all populations?

Summary

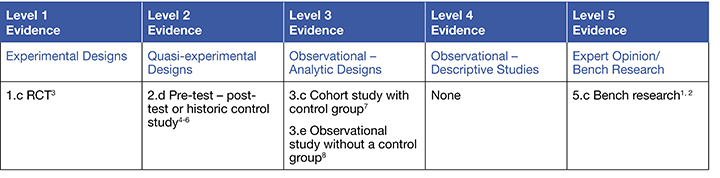

Bench research provides Level 51, 2 evidence that moisture, temperature and humidity influence the coefficient of friction between the skin and fabrics, and that performance differs between fabrics. Evidence from one randomized controlled trial (RCT),3 provided Level 1 evidence supporting use of a low friction fabric in conjunction with an incontinence product for older individuals to reduce the incidence of PIs. Level 24-6 and Level 37, 8 evidence suggested that low friction fabrics can be used in a range of care settings (e.g. medical, surgical and intensive care) for individuals at high and lower risk of PIs to reduce the risk of developing a new PI. This evidence supported a Grade B recommendation (a weak recommendation).9

Clinical practice recommendations

All recommendations should be applied with consideration to the patient, the health professional and the clinical context.

Low friction fabrics could be used to prevent pressure injuries in individuals with a moderate to high pressure injury risk (Grade B).

Sources of evidence

This summary was conducted using methods published by the Joanna Briggs Institute.9-11 The summary is based on a literature search combining search terms related to PIs and low friction fabric/linen. Searches were conducted in CINAHL, Medline, the Cochrane Library and Google Scholar for evidence published up to December 2019 in English. Levels of evidence for intervention studies are reported in the table below.

Background

Any item placed close to the skin can influence the microclimate (particularly skin temperature and moisture).1, 2, 8 This includes bedding, gowns, bootees and other fabric products. Low friction fabrics (also referred to as synthetic fibre, silk-like fabric or specialty linen4) have a range of features that differ from standard hospital linen (cotton or cotton-polyester blend).4, 5, 7 Features of low friction fabrics that might contribute to prevention of PIs include:

- Yarn material and weave designs that reduce friction and shear4, 5 by lowering the force required to overcome the grip (coefficient of friction) between the individual and the support surface.6, 7

- Ability to dry faster and/or wick moisture away from skin, reducing the impact of moisture.4, 5, 8

- Ability to remain cooler for longer, reducing the impact of warmer temperature.4

Evidence

- An RCT at moderate risk of bias conducted in high level aged care (n = 46 participants) found a significantly lower incidence of PIs at 20 weeks associated with silk-like linen compared to cotton blend linen (hazard ratio[HR] = 0.31, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.12 to 0.78). The results were also significant for Stage II or greater PIs (HR = 0.23, 95% CI 0.078 to 0.69, p=0.0084). Use of different incontinence products between the groups may have contributed to results3 (Level 1).

- In a prospective study at moderate risk of bias, the incidence of new PIs was significantly lower for a group receiving low friction fabric gowns and bed linen compared with a group receiving cotton-blend fabrics (4.6% versus 12.3%, p = 0.01). Participants were medical renal patients at high risk for PIs. The same study, repeated in surgical intensive care units (ICUs) with participants at high PI risk, also showed significant reduction in PI incidence associated with low friction fabric (0% versus 7.5%, p = 0.01) 6 (Level 2).

- In a retrospective before-after study at moderate risk of bias (n = 768 participants), a group receiving low friction fabric gowns and bed linen experienced significantly a lower incidence of Stage I (5.6% versus 2.3%, p<0.001) and Stage II PIs (5.95% versus 0.8%, p<0.001) than a control group receiving regular clothing and bedding. Individuals were recruited from a range of clinical areas and likely represented people with both low and high risk of PIs5 (Level 2).

- A prospective study at high risk of bias found that although the incidence of PIs was not different between two ICU cohorts (both 6.6%) there was significantly greater reduction in PI incidence over time in a cohort (n = 1,647) receiving a low friction fabric on the bed compared to a cohort (n = 2,153) receiving cotton blend linen (7.71% versus 5.26%, p = 0.002). Both cohorts primarily included individuals with a low to moderate risk of pressure injuries4 (Level 2).

- A multivariate analysis at high risk of bias (n = 71 participants) showed that the type of sheet used (low friction fabric versus cotton) had an odds ratio of 0.11 (95% CI 0.012 to 1.032, p = 0.053) for development of a PI. The only other statistically significant variable was the Braden Scale score. The study was conducted in an environment with very high average mean room temperature and humidity, which increased perspiration8 (Level 3).

- A cohort study at high risk of bias reported a significant reduction in PI incidence in a cohort receiving low friction fabric undergarments and/or bootees (n = 204) compared to a cohort receiving regular garments (n = 165; 25% versus 41%, p=0.02). Both cohorts primarily included individuals with a moderate-high risk of heel or sacral PIs7 (Level 3).

Considerations for use

The following points should be considered when using low friction fabrics to prevent PIs:

- Raising the knee of the bed may prevent sliding. When seated on an ordinary chair without a support cushion, a towel can be placed between the low friction fabric and the chair surface to prevent sliding.4

- Education on use of low friction fabrics might increase acceptability of the product and promote correct use.4

- A cohort study conducted in ICUs in the US reported a low friction fabric was approximately 2.3 times more expensive to purchase than cotton blend fabric, but it lasted three times longer and was associated with almost $4 million (USD in 2015) lower costs due to reduction in hospital costs associated with facility-acquired PIs.4

- Low friction fabrics might require different laundering processes to standard hospital linen. The manufacturer’s instructions should be followed.3

Author(s)

Assoc. Prof. Emily Haesler

PhD

Wound Healing and Management Centre, Curtin University (WHAM@Curtin)

References

- Schario M, Tomova-Simitchieva T, Lichterfeld A, Herfert H, Dobos G, Lahmann N, Blume-Peytavi U, Kottner J. Effects of two different fabrics on skin barrier function under real pressure conditions. J Tissue Viability, 2017. May;26(2):150-5.

- Schwartz D, Magen YK, Levy A, Gefen A. Effects of humidity on skin friction against medical textiles as related to prevention of pressure injuries. Int Wound J, 2018. Dec;15(6):866-74.

- Twersky J, Montgomery T, Sloane R, Weiner M, Doyle S, Mathur K, Francis M, Schmader K. A randomized, controlled study to assess the effect of silk-like textiles and high-absorbency adult incontinence briefs on pressure ulcer prevention. Ostomy Wound Mange, 2012;58(12):18-24.

- Freeman R, Smith A, Dickinson S, Tschannen D, James S, Friedman C. Specialty linens and pressure injuries in high-risk patients in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care, 2017. Nov;26(6):474-81.

- Smith A, McNichol LL, Amos MA, Mueller G, Griffin T, Davis J, McPhail L, Montgomery TG. A retrospective, nonrandomized, before and after study of the effect of linens constructed of synthetic silk-like fabric on pressure ulcer incidence. Ostomy Wound Manage, 2013. Apr;59(4):28-34.

- Coladonato J, Smith A, Watson N, Brown AT, McNichol L, Clegg A, Griffin T, McPhail L, Montgomery TG. Prospective, nonrandomized controlled trials to compare the effect of a silk-like fabric to standard hospital linens on the rate of hospital-acquired pressure ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage, 2012;58(10):14-31.

- Smith G, Ingram A. Clinical and cost effectiveness evaluation of low friction and shear garments. J Wound Care, 2010;19(12):535-42.

- Yusuf S, Okuwa M, Shigeta Y, Dai M, Iuchi T, Sulaiman R, Usman A, Sukmawati K, Sugama J, Nakatani T, Sanada H. Microclimate and development of pressure ulcers and superficial skin changes. Int Wound J, 2015; 12(1): 40-6.

- Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. New JBI Grades of Recommendation. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2013.

- Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

- The Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party. Supporting Document for the Joanna Briggs Institute Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation. www.joannabriggs.org: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2014.