Volume 29 Number 2

Caring for a child with Epidermolysis Bullosa: a scoping review on the family impacts and support needs

Colin J Ireland, Lemuel J Pelentsov, and Zlatko Kopecki

Keywords Family, Epidermolysis Bullosa, supportive care needs, parents, service delivery models

For referencing Ireland CJ et al. Caring for a child with Epidermolysis Bullosa: a scoping review on the family impacts and support needs. Wound Practice and Research 2021; 29(2):86-97.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wpr.29.2.86-97

Abstract

Aims Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB) is a rare genetic disorder characterised by recurrent skin blistering. Wound care and nursing are critical to everyday lives of EB patients. The aim of this review was to identify the support needs of parents of a child with EB and to assess the impact EB has on the family unit, irrespective of subtype of condition severity.

Methods We conducted a scoping review comprising 11 studies (2005–2021) to examine the research literature related to the support needs of parents with a child with EB, and the impact on family unit wellbeing.

Results Most common needs identified were emotional needs, followed by practical needs, social needs and physical needs. Many parents also reported a lack of informational and psychological support. Common findings included emotional stress, lack of respite and physical strain on caring responsibility, financial stress, guilt and impact on relationships and family unit.

Conclusions Few studies exist that explore the support needs of parents of a child with EB. More attention should be paid to the support needs of parents to provide adequate care to those diagnosed with EB as well as their families.

Introduction

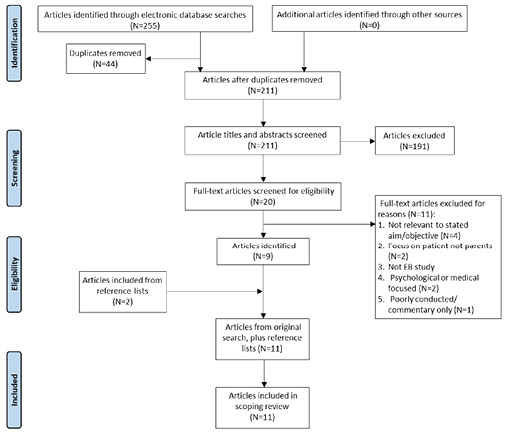

Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB) is a complex group of genetic disorders producing various degrees of recurrent skin blistering and epidermal detachment from the basement membrane in response to mechanical trauma1. The latest consensus reclassification of inherited EB and other disorders with skin fragility describes major classical types of EB including EB simplex (EBS), junctional EB (JEB), dystrophic EB (DEB) and Kindler EB (KEB)2. The clinical features for each of the four main types of EB are provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The four main Epidermolysis Bullosa types and associated clinical features.

EBS: EB simplex with generalised blistering and superficial bullae over the body and blistering on the foot

JEB: Junctional EB with extensive shoulder blistering and vesiculobullous erosions and milia formation on the forearm

DEB: Dystrophic EB with severe scarring and pseudosyndactyly of the hands and atrophic areas on the lower extremities

KEB: Kindler Syndrome with poikiloderma on the hands and erosions on the back

Images provided by DEBRA

In addition to the four major types there are over 30 different subtypes of EB and varying degrees of severity ranging from mild local skin involvement with minimal impact on quality of life and overall longevity to severe forms involving multiple organs with early postnatal death or chronic progression and painful and life-threatening complications3. Chronic skin blistering commonly leads to the development of skin cancer, a major cause of death in severe forms of EB, hence significantly impacting a patient’s quality of life and resulting in decreased life expectancy4. There is currently no cure for EB; however, concurrent advances in gene and stem cell therapies and significant focus on the design of symptom relief therapies over the last decade are converging towards multimodal combination therapies that hold the promise of clinically meaningful and lifelong improvement5.

The characteristics of severe EB demand higher than average levels of support compared to other children with chronic needs as disease management is focused on symptom control and extensive wound care6. Wound management and nursing are an important aspect of support for families with a child with EB; however, many health professionals do not adequately understand the impact EB has on the individuals and the family unit. Numerous studies have described the needs of patients with EB and support from nurses, and qualitatively and quantitatively assessed the impact of disease on a patient’s quality of life7–9. Additionally, many studies to date have acknowledged the impact of EB on caregiving parents, including the impacts on family size/planning and relationships10–13. The latest evidence-based psychosocial recommendations for the care of EB patients published in 2019 highlight the significant impacts the disease places on individuals with EB and their families, including all aspects of psychosocial life14. Additionally, this international guideline identified the research gap in better understanding the support needs of parents caring for a child with EB and the impact on the family unit14.

Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association (DEBRA) International is an umbrella patient advocacy and support organisation with member organisations in over 50 countries worldwide aimed to support best practices for EB care, increase professional knowledge of the condition, coordinate research efforts to better understand EB, find effective treatments and develop cures for all EB types. DEBRA groups in different countries have been critical in working with governments and healthcare systems to develop and implement the best models of care for patients and their families with EB, and implementing pivotal family support programs that aim to address the gap in the support offered by governments. However, there exists a wide difference in levels and range of support provided (for example, nursing support, access to dressings and medical and support needs, psychology programs, youth mental health programs, respite programs, family camps) for patients and their families with EB across different countries and sometimes even different regions or states in the same country15–17.

The objectives of the current review are three-fold:

- To identify the support needs of parents with a child with EB and the subsequent impacts EB has on the family unit irrespective of EB subtype of condition severity.

- To help inform future research on the impacts of EB on families, as well as help develop and revise future guidelines for care and development of an effective framework of support for patients and families with EB.

- To advance wound care practices by nurses and DEBRA groups in developing effective and tailored models of family support in their communities.

The novelty of this review includes development of the support care needs framework that can guide healthcare professionals (HCPs) in providing patient-centric support models for the person/child with EB and their family unit as a whole.

Methods

A scoping review was undertaken guided by the five-stage framework approach described by Arksey and O’Malley18, and subsequently enhanced and reinforced over the past few years19–21, in order to undertake a comprehensive literature search. The benefits of using the scoping review framework included: the ability to consider a broad array of literature including qualitative, quantitative and grey literature; and the capacity for a broad research question to be addressed in what is otherwise a limited area of focus within a specific rare disease18,20. A systematic process was used to ensure rigour and transparency. The results are reported following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines22.

Research question

What are the support needs of parents caring for a child with Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB)?

Search strategy

It was agreed that the search for relevant literature would be limited to peer-reviewed published articles to adequately address the stated research question. Electronic databases searched were Medline, Embase, PsychInfo, Health and Society, Scopus, as well as the search engine Google Scholar.

Key search terms and phrases were Epidermolysis Bullosa* or EB Simplex or Junctional EB or Dystrophic EB or Kindler Syndrome and parents or mothers or fathers or caregivers or carers or family* and emotional or support* or burden* or impact* or need or care or wellness or wellbeing or cope or coping. Searches were limited to articles written in English between January 2005 through to March 2021. Review articles were excluded to minimise duplication of reporting. As we were focusing on the needs of parents, articles were excluded if they appeared to focus on caregivers other than parents (mothers and fathers); studies that were considered too medically focussed or psychologically obscure were also excluded. This resulted in 255 potential articles which were imported to the full text screening software Covidence® for a title and abstract review. Authors independently reviewed all articles.

Study selection

Title and abstract screening were undertaken by authors, including both review of all articles independently and selection to exclude or include respectively. If there was any conflict, for example one excluded and one included, then these were reviewed together, and a consensus was reached. Following final agreeance on included articles, full texts were obtained and reviewed by all authors independently. Conflicts were reviewed as a team and the final decision to include or exclude was made. Remaining literature sources from each of the database searches were exported into the references and bibliographic management software program EndNote® for detailed examination and charting of relevant information to address the research question.

Charting of the data

The remaining full-text articles were then included in the extraction of information using a standardised data extraction form. The data extraction form included author, year, country, study aim, study design, method, sample size, main findings and critique. These were then reviewed by all authors for validation of domains and areas of support needs. Following this, all authors confirmed the support needs identified within each article and this was then added to the data extraction table as an additional column.

Results

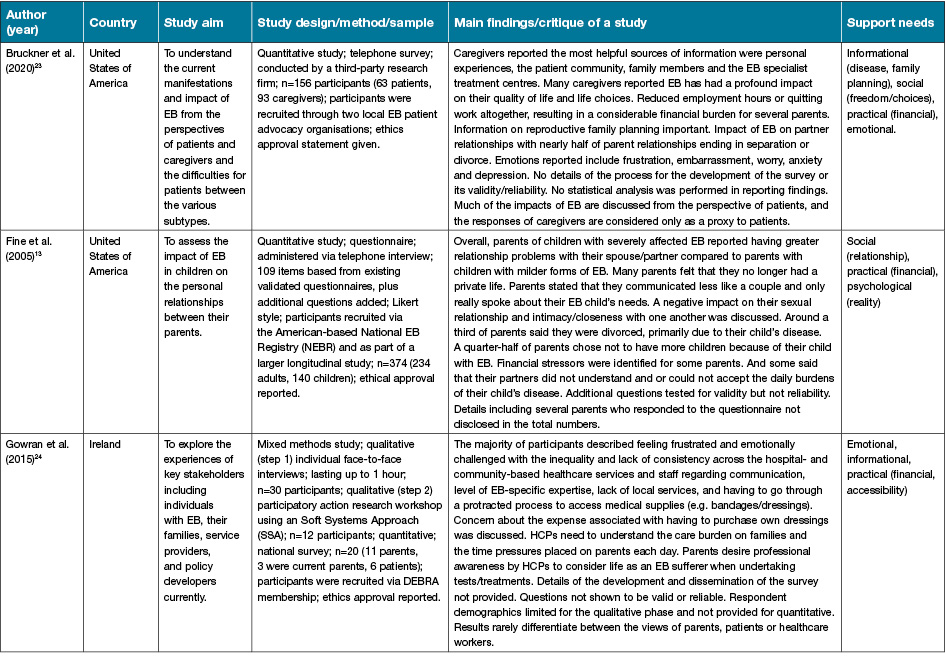

A total of 255 articles were identified during the initial search; 44 duplicates were removed. Following title and abstract and full-text screening, 11 studies were included in the final review, covering all subtypes of EB. Numbers of sources of evidence assessed for eligibility and included in this final review are summarised in Figure 2 in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines22.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram of search and selection

Out of the 11 studies which met the inclusion criteria, six used qualitative methods (interviews), three used quantitative (questionnaires), and two used a combination of both to gather information. All included studies reported on the perceptions of support needs from a caregiver perspective. While seven studies also reported on the support needs of patients, these details were not included in the reporting of results of this scoping review. Eight reported studies were conducted by support organisations and local community groups, and three were conducted by hospital and university dermatology departments. Eight studies characterised findings based on support need perceptions as viewed by the mother or father of the child, one study mentioned the inclusion of a family which had a healthy child in the family unit, and one study reported findings of the siblings.

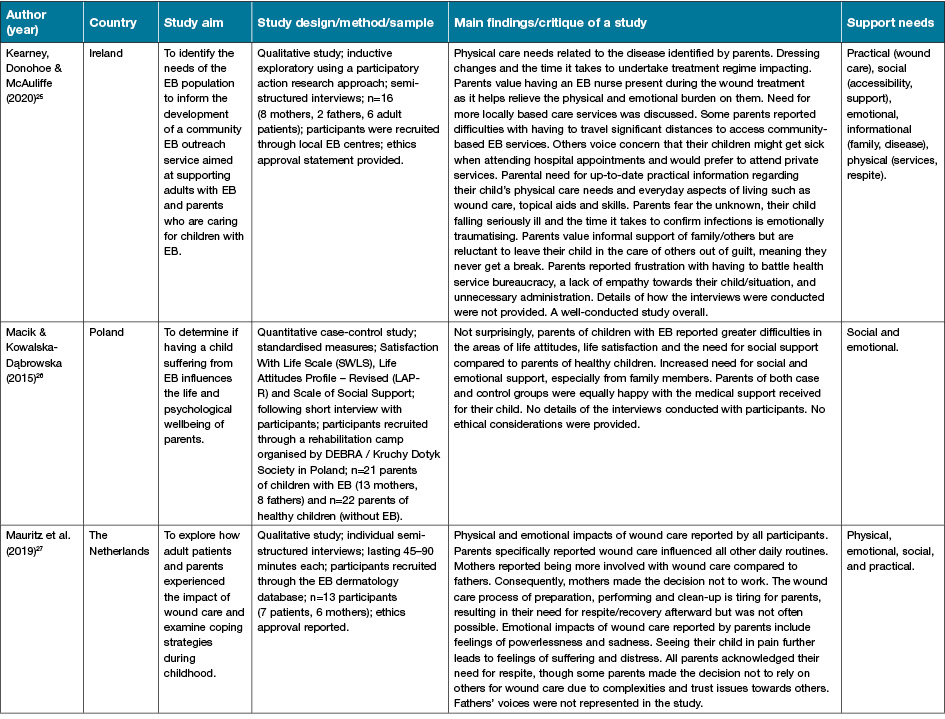

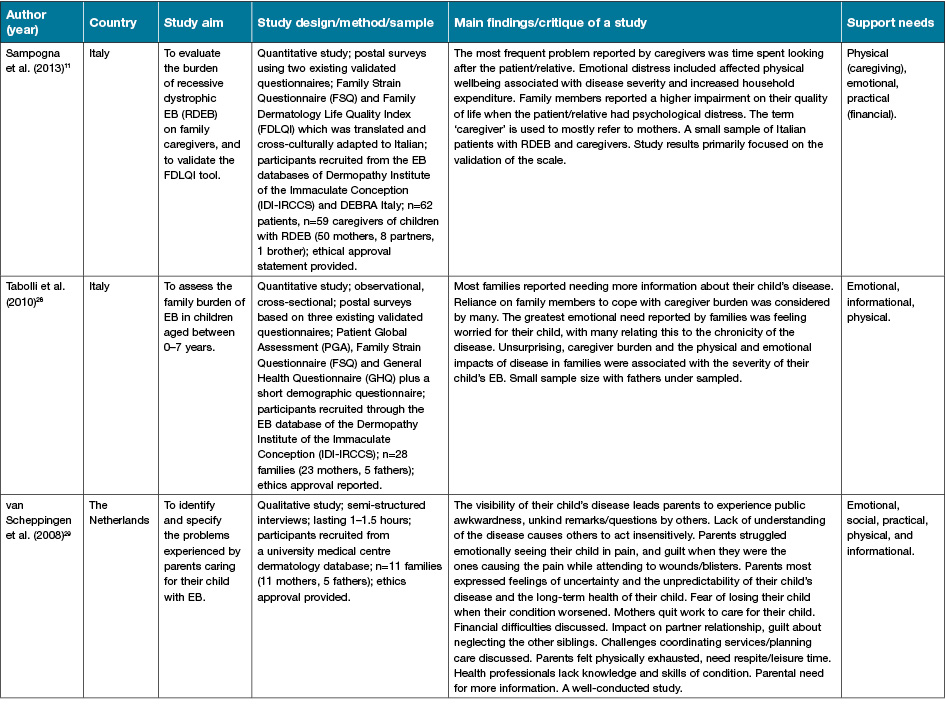

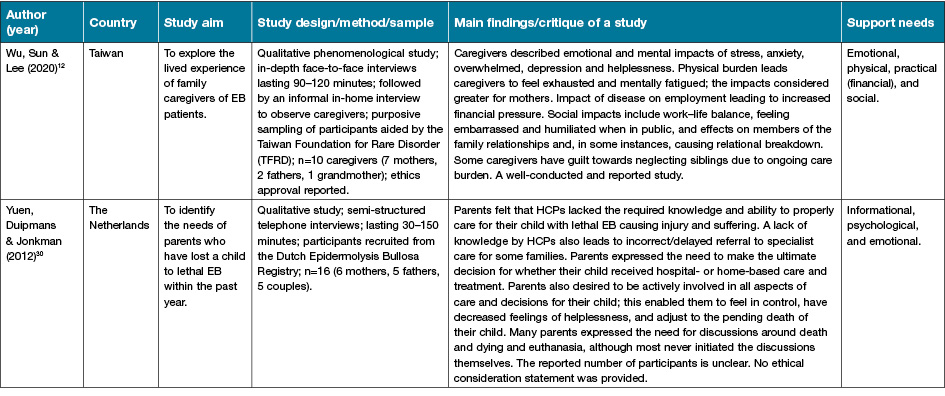

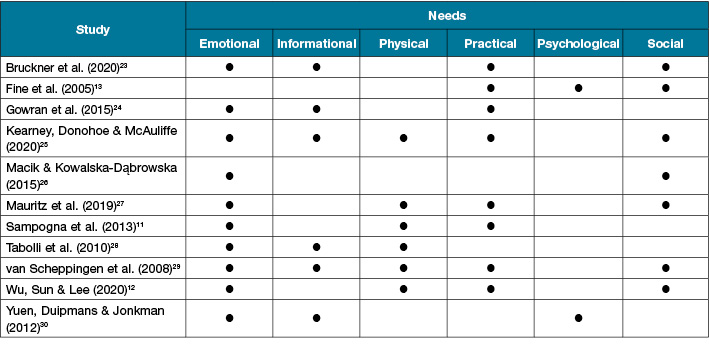

Six overarching support needs domains were identified – emotional needs, practical needs, social needs, physical needs, informational needs and psychological needs. The most common needs identified were emotional needs (n=10; 90%), followed by practical needs (n=8; 72%) and social needs (n=7; 63%) (Table 1). The majority of studies (n=10, 90%) reported on three or more supportive care need domains. Table 2 provides a synthesis of the domains of support needs discussed within the studies.

Table 1. Details of primary studies identified and reviewed

Table 2. Summary of support needs

Emotional needs

Emotional needs were the most identified support needs and overwhelmingly encompass many support need domains for parents caring for a child with EB. Parents described the most common emotions associated with their child’s EB to include frustration, embarrassment, worry, anxiousness and depression12,23–25. Many parents expressed difficulties in accepting their child’s condition and the daily burden that the disease demanded. The emotional impacts of the daily wound care routine place a significant toll on parents, mostly mothers, with feelings of powerlessness and sadness at seeing their child in pain and suffering27. This leads parents to feelings of guilt about being responsible and causing pain to their child during dressing changes23. The impacts of their child’s disease on the family unit were also reported by parents as having a negative effect on personal relationships with their spouse/partner and other family members13,29. The most significant ongoing emotional need reported by parents was feelings of guilt, with some parents also reporting guilt towards neglect of other siblings due to the ongoing care burden associated with looking after their child with EB29.

The majority of parents reported a range of emotional stresses as a result of perceived inequality and lack of consistency across both hospital- and community-based support healthcare services24. In part, parents did not feel well supported by HCPs in addressing their emotional needs and would have valued a higher level of care and understanding from them in this area29,30.

Compounding effects of emotional needs on parents caring for a child with EB were identified, influencing life choices and leading to a decreased life satisfaction; this was correlated with the severity of EB and stage of life (newborn vs childhood vs palliative care) and family support23,26,28. Parents often reported the need for respite from caring responsibilities; however, a barrier to this was their emotional trust issues around relying on others to take carriage of their child’s complex wound care regime in their absence27. Fear of the unknown was also identified as a significant emotional need each time their child fell ill or during the period it took to confirm an infection and/or receive diagnosis/treatment; these were significantly traumatising for parents, adding to the ongoing concern about care burden25. Interestingly, parents also reported the need for discussion around death and euthanasia of their child with EB, although they never initiated these discussions themselves30.

Practical needs

The most commonly reported practical need identified by parents was that of financial concerns. Largely, this was associated with issues around employment and income/earning capacity due to the high burden of care associated with their child’s disease. Some parents had to reduce working hours or terminate employment altogether in order to care for their child with EB29. The impact on employment was more pronounced by mothers who were often the main caregivers; however, the financial implications of EB on the family as a whole were a significant source of stress for both parents as fathers had an added burden of being the sole provider for the family11,24.

Compounding the parents’ financial concerns was the expense of having to purchase their child’s dressings; the protracted process they had to go through to acquire these was considered an unnecessary practical need for them24–26. Parents reported that wound care influenced all other daily life routines, making planning and organising family life extremely challenging27. Additionally, having to coordinate and navigate local health services and appointments, and planning care for their child with EB was a constant source of stress and concern for parents29. Parents reported constant challenges around not only the accessibility of wound care dressings but also in accessing local health services and this was further influenced by the provision of government-funded dressing schemes in certain countries or the metropolitan vs rural placement of the family24,25.

Parents felt that, in order for others to care for their child in their absence, this would require a significant amount of training and trust for parents to feel comfortable leaving their child in their care30. Together, the practical needs of parents caring for their child with EB highlighted the need for better support services for parents to allow them much-needed respite and time free from their caring responsibilities.

Social needs

Parents most frequently voiced the need for more support in caring for their child with EB, particularly from family members. Issues with relationships and a lack of support from family members were reported by parents to have affected their quality of life and freedom of life choices13,23,26,29. Access to a support group, such as DEBRA, was considered by parents as an important means of support and respite27. There was an overarching feeling of embarrassment and humiliation when in public and a feeling that others did not fully understand or appreciate the impacts that their child’s EB has on them and on their family unit25,29. These feelings were further compounded by the negative impact associated with a lack of work–life balance, adding additional strain on the family unit. This included effects on both partner relationship and relationships with other children where parents felt guilty about neglecting the other children12,29.

The daily burden of care and missed opportunities to spend quality time together often had a negative impact, with one study reporting nearly half of all parent relationships ending in separation or divorce23. Unsurprising, parents caring for a child with a severe form of EB reported having greater relationship problems with their spouse/partner compared with parents with children with milder EB forms. Many parents report not having an active social life. This further affected their communication/relationship with a partner which predominantly centred on either providing care or discussing the needs of the child with EB13. As a result, compounding impact also affected the sexual relationship and intimacy with each other, with a third of parents in one study saying they divorced primarily due to their child with EB while a quarter to half of parents in the same study reported not wanting to have more children as a result of their child with EB13.

Accessibility to support services was also an important factor affecting the social wellbeing of parents as some highlighted the need for more locally based services to access support and reported having to travel significant distances to access community-based EB services25.

Physical needs

Caring for a child with EB often left parents feeling physically and emotionally fatigued25,27. Parents reported this mainly related to all consuming aspects of providing wound care for their child with EB, the process of wound preparation, performing and cleaning-up following which was a very physically demanding responsibility, combined with the emotional aspects of seeing their child in pain and discomfort27. The physical needs of parents caring for their child with EB also extended to general caregiving, leaving parents emotionally distressed which attributed to their physical needs, especially mothers who acknowledged that they largely assumed the primary carer role11. Some parents had EB themselves and related the physical problems associated with it with that of their child, making caregiving even more physically challenging28. Parents cited feeling overwhelmed, exhausted and mentally fatigued, highlighting the greater need for better community support services providing respite12,29. They reported feeling as if they were never off duty, which exacerbated their exhaustion29.

Informational needs

Parents considered the most helpful sources of information to include personal experiences of other parents, the patient community, family members, and accessing EB specialist centres23–25,28–30. Information on reproductive family planning was an important aspect raised by some parents23. Many parents describe feeling frustrated with inequality and lack of consistency across hospital- and community-based services, and information provided by HCPs, including lack of EB-specific expertise and knowledge among various health professionals24,25,29. Parents identified a requirement for better support in providing up-to-date information on their child’s physical care needs and everyday living aspects, including wound care, topical treatments and skills so that they could more adequately plan for the future25. The need for better informational support was most evident in the groups of parents caring for a newborn where a definitive diagnosis was pending, and parents caring for a child with lethal EB, resulting in delayed referrals to specialists in some cases30. In addition, parents also commented that they required accurate information regarding disease progression and were not prepared for the suffering at the end of life30.

Psychological needs

Psychological needs were discussed much less frequently in the studies compared to other domains, with only 18% of studies identifying parental psychological need as an important aspect of support for families with a child with EB. Psychological needs noted included parents’ perception of reality and their struggle to understand or accept the daily burden of their child’s disease13. The psychological needs of parents are related to the level of social and family support, relationship status and severity/progression of the child’s disease30. Many caregivers expressed that EB had a profound effect on their quality of life and life choices, including psychological/spiritual wellbeing23. Two studies identified the need for better coping strategies to manage the disease burden, depression and mental health wellbeing of parents23,28.

Discussion

This review of the literature is the first to comprehensively and systematically identify the documented support needs of parents caring for a child with EB, and to categorise these needs under six domains to identify areas of unmet need in parents.

It is important to acknowledge that support needs are dynamic and can alter over time because of factors such as the disease journey, the severity of disease, age and personal or environmental changes31. This was evident from several studies included in this scoping review, which are not necessarily unique to EB, where parents reported that socioeconomic factors, patient age, severity/stage of EB and access to medical resources and supports all negatively impact on their support needs in caring for their child with EB23,24. This is consistent with previous findings showing that support needs of parents and individuals living with a rare disease are dependent on the country/medical system32, while EB patient/family access to dressings and in-home nursing support can also be affected by families’ metropolitan versus rural location15,16.

From this review, we have identified that parents, irrespective of the severity of their child’s EB, share common support needs. Aspects relating to emotional needs were identified by parents focusing on stress and guilt but also the uncertainty and fear of the unknown. Largely, the emotional needs of parents were directly related to their child’s disease and the daily caregiver burden. However, it could be argued that emotional needs, if gone unmet, can influence other needs, including mental and psychological needs, often leading to the development of depression and mental health issues14. Therefore, facilitating the emotional support needs of parents caring for a child with EB should be an important consideration by HCPs. If parents are not coping emotionally, then their ability to care for their child with EB is challenged, placing themselves, their family unit and their sick child at further risk.

Interestingly, practical needs were the second most documented need in the current literature, with financial concerns being the most commonly identified aspect, as the cost of dressings in caring for the child with EB can place a significant burden on the family. The long-term sacrifice parents make in caring for their child with EB has been indicated in several studies as parenting a child with EB is a life-long commitment, including impact on work–life balance, physical/mental exhaustion and feelings of isolation13,24,26,27,29. These findings were in agreement with the recent report on the psychosocial recommendations for the care of children and adults with EB and their families published by DEBRA International14. All these factors were more predominantly observed in mothers of children with EB who are often the primary carers; data on fathers’ support needs are not often reported to date.

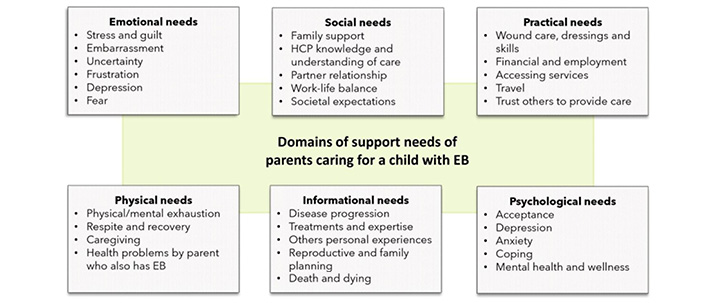

Social, physical, emotional and psychological needs are often compounding and interrelated, while there is also a close relationship between the practical and informational needs of parents caring for a child with EB focused mainly on access to EB-specific services and planning at different stages of disease progression29,30. This highlights the complex interrelationship of different support needs of parents caring for a child with EB, including the interplay between emotional, practical, social, physical and psychological needs.

Importantly, both emotional and informational needs identified highlighted that death, euthanasia and not being prepared for end of life are significant issues affecting parents of children with EB; this was in agreement with findings of the evidence-based psychosocial guidelines for care of children and adults with EB and their families14. Overall, the identified support needs are similar to those of other parents caring for a child with a rare disease where patient numbers are small, support is varied or lacking, and families are geographically scattered32. Importantly, the needs will vary vastly based on access to family support or in-home nursing care and the child’s age15.

Based on the findings of the cited literature, we propose a novel parent support needs framework (Figure 3) which considers the complexity and interrelationship of the different support needs identified here. This is a suggested framework; however, more research in this area is needed to validate the domains of support needs and finalise the framework.

Figure 3. Proposed domains of parent support needs

Limitations of the review

The review followed the seminal scoping study framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley18. A systematic process was used to ensure rigour and transparency following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines22. The authors engaged with each of the five stages of the scoping review process in an iterative manner and, where necessary, repeated steps to ensure the review of literature in this area was comprehensive. Nevertheless, there are some limitations with the current process that need to be acknowledged, including targeting the primary search to English language studies. We appreciate that there might be other published studies addressing the unmet support needs of parents caring for a child with EB in another language that were not included in this review. Importantly, to the topic of EB and support needs of parents, we also found that majority of studies reviewed the mothers’ voices more prominently; this may reflect the fact that mothers are mainly the primary caregivers, and hence more likely to engage in studies exploring aspects of need in them. While some studies acknowledged this and outlined the need for a better understanding of the support needs of fathers, others did not address this and still used the word ‘parent’ in the title to reflect the views of mothers. We acknowledge that the support needs of parents are not homogeneous.

Implications for further research and practice

Despite reviewing a large timeframe (16 years), the paucity of studies in this review reflects the lack of focus on support needs of parents caring for a child with EB, especially fathers. This is not entirely surprising considering the rare nature of EB disease; however, the review emphasises the lack of evidence and highlights the need for future research on this important area. The development of new supportive care models that address the six domains of support needs identified in this review is urgently needed in the community to better support parents caring for a child with EB. Additional qualitative research and integrative reviews of the qualitative and quantitative literature is required to better understand the needs of families. Such studies will allow identification of the most important support needs of families with a child with EB, allowing the development of a multifaceted framework of support for these families.

Conclusion

Six domains of support needs were identified in this review with emotional, social and practical needs being the most common for parents caring for a child with EB. The caregiving burden is disproportionally affecting the mothers of children with EB, and fathers support needs are less identified, with parents’ support needs not being homogeneous. We have proposed a novel parent support needs framework which could be used to guide future provisions of care for families. We hope that this review will help guide future research and development of support services in the community to allow support organisations like DEBRA and wound care HCPs to offer a better quality of life for parents and families with EB.

Author contributions

The authors confirm they had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis. All the authors gave final approval of this version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that the questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgments

Zlatko Kopecki is a Channel 7 Children’s Research Foundation Fellow in Childhood Wound Infections. The authors would like to acknowledge funding support from DEBRA International and in-kind support from DEBRA Australia.

Conflict of interest

Zlatko Kopecki is a Board member of DEBRA International and DEBRA Australia and a member of the Editorial Board of the Wound Practice and Research Journal.

Author(s)

Colin J Ireland PhD

Clinical and Health Sciences, University of South Australia, SA Australia

Lemuel J Pelentsov PhD

Clinical and Health Sciences, University of South Australia, SA Australia

Zlatko Kopecki* PhD

Clinical and Health Sciences, University of South Australia, SA Australia

Future Industries Institute, University of South Australia, Mawson Lakes Campus, Building X, Mawson Lakes, SA 5095, Australia

Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association (DEBRA) International and Australia

Email zlatko.kopecki@unisa.edu.au

* Corresponding author

References

- Kopecki Z, Murrell DF, Cowin A. Raising the roof on Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB): a focus on new therapies. Wound Pract Res 2009;17(2):76–82.

- Has C, Bauer JW, Bodemer C, Bolling MC, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Diem A, et al. Consensus reclassification of inherited Epidermolysis Bullosa and other disorders with skin fragility. Br J Dermatol 2020.

- Denyer J, Pillay E, Clapham J. Best practice guidelines for skin and wound care in Epidermolysis Bullosa. An international consensus. Wounds Int 2017.

- Fine JD, Johnson LB, Weiner M, Li KP, Suchindran C. Epidermolysis Bullosa and the risk of life-threatening cancers: the National EB Registry experience, 1986–2006. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60(2):203–11.

- Vanden Oever M, Twaroski K, Osborn MJ, Wagner JE, Tolar J. Inside out: regenerative medicine for recessive dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa. Pediatr Res 2018;83(1–2):318–24.

- Perez VA, Morel KD, Garzon MC, Lauren CT, Levin LE. Review of transition of care literature: Epidermolysis Bullosa, a paradigm for patients with complex dermatologic conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020.

- Danescu S, Salavastru C, Sendrea A, Tiplica S, Baican A, Ungureanu L, et al. Correlation between disease severity and quality of life in patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019;33(5):e217–e9.

- Frew JW, Murrell DF. Quality of life measurements in Epidermolysis Bullosa: tools for clinical research and patient care. Dermatol Clin 2010;28(1):185–90.

- Togo CCG, Zidorio APC, Goncalves VSS, Hubbard L, de Carvalho KMB, Dutra ES. Quality of life in people with Epidermolysis Bullosa: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 2020;29(7):1731–45.

- Dufresne H, Hadj-Rabia S, Bodemer C. Impact of a rare chronic genodermatosis on family daily life: the example of Epidermolysis Bullosa. Br J Dermatol 2018;179(5):1177–8.

- Sampogna F, Tabolli S, Di Pietro C, Castiglia D, Zambruno G, Abeni D. The evaluation of family impact of recessive dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa using the Italian version of the Family Dermatology Life Quality Index. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27(9):1151–5.

- Wu YH, Sun FK, Lee PY. Family caregivers’ lived experiences of caring for Epidermolysis Bullosa patients: a phenomenological study. J Clin Nurs 2020;29(9–10):1552–60.

- Fine JD, Johnson LB, Weiner M, Suchindran C. Impact of inherited Epidermolysis Bullosa on parental interpersonal relationships, marital status and family size. Br J Dermatol 2005;152(5):1009–14.

- Martin K, Geuens S, Asche JK, Bodan R, Browne F, Downe A, et al. Psychosocial recommendations for the care of children and adults with Epidermolysis Bullosa and their family: evidence based guidelines. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2019;14(1):133.

- Stevens LJ, McKenna S, Marty J, Cowin AJ, Kopecki Z. Understanding the outcomes of a home nursing programme for patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa: an Australian perspective. Int Wound J 2016;13(5):863–9.

- Stevens LJ. Access to wound dressings for patients living with Epidermolysis Bullosa – an Australian perspective. Int Wound J 2014;11(5):505–8.

- Harris AG, Todes-Taylor NR, Petrovic N, Murrell DF. The distribution of Epidermolysis Bullosa in Australia with a focus on rural and remote areas. Austr J Dermatol 2017;58(2):122–5.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8(1):19–32.

- Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67(12):1291–4.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69.

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 edition / Supplement – Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. 2015.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169(7):467–73.

- Bruckner AL, Losow M, Wisk J, Patel N, Reha A, Lagast H, et al. The challenges of living with and managing Epidermolysis Bullosa: insights from patients and caregivers. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2020;15(1):1.

- Gowran RJ, Kennan A, Marshall S, Mulcahy I, Ni Mhaille S, Beasley S, et al. Adopting a sustainable community of practice model when developing a service to support patients with Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB): a stakeholder-centered approach. Patient 2015;8(1):51–63.

- Kearney S, Donohoe A, McAuliffe E. Living with Epidermolysis Bullosa: daily challenges and health-care needs. Health Expect 2020;23(2):368–76.

- Macik D, Kowalska-Dąbrowska M. The need of social support, life attitudes and life satisfaction among parents of children suffering from Epidermolysis Bullosa. Przegl Dermatol 2015;102:211–20.

- Mauritz P, Jonkman MF, Visser SS, Finkenauer C, Duipmans JC, Hagedoorn M. Impact of painful wound care in Epidermolysis Bullosa during childhood: an interview study with adult patients and parents. Acta Derm Venereol 2019;99(9):783–8.

- Tabolli S, Pagliarello C, Uras C, Di Pietro C, Zambruno G, Castiglia D, et al. Family burden in Epidermolysis Bullosa is high independent of disease type/subtype. Acta Derm Venereol 2010;90(6):607–11.

- van Scheppingen C, Lettinga AT, Duipmans JC, Maathuis CG, Jonkman MF. Main problems experienced by children with Epidermolysis Bullosa: a qualitative study with semi-structured interviews. Acta Derm Venereol 2008;88(2):143–50.

- Yuen WY, Duipmans JC, Jonkman MF. The needs of parents with children suffering from lethal Epidermolysis Bullosa. Br J Dermatol 2012;167(3):613–8.

- Davies EL, Gordon AL, Pelentsov LJ, Hooper KJ, Esterman AJ. Needs of individuals recovering from a first episode of mental illness: a scoping review. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2018;27(5):1326–43.

- Pelentsov LJ, Laws TA, Esterman AJ. The supportive care needs of parents caring for a child with a rare disease: a scoping review. Disabil Health J 2015;8(4):475–91.