Volume 29 Number 3

Hospital-acquired pressure injury prevention in people with a BMI of 30.0 or higher: a scoping review protocol

Victoria Marshall, Victoria Team and Carolina Weller

Keywords Body mass index, pressure injury, pressure ulcer, obesity, hospital

For referencing Marshall V et al. Hospital-acquired pressure injury prevention in people with a BMI of 30.0 or higher: a scoping review protocol. Wound Practice and Research 2021; 29(3):133-139.

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wpr.29.3.133-139

Submitted 10 June 2021

Accepted 2 July 2021

Abstract

Background Pressure injuries (PIs) are a significant healthcare burden and an international safety and quality care issue. Managing and preventing PIs in high body mass index (BMI) patients (those with a BMI of 30 or higher) requires a multifactorial approach and additional resources.

Aim This review will systematically search and synthesise available evidence of hospital-acquired pressure injury (HAPI) in patients with a high BMI, and map current best prevention practices and nurses’ experiences.

Methods and analysis The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews Checklist (PRISMA-ScR) will be used to guide this review. Literature in English from 2009 to May 2021 will be searched from databases including Ovid MEDLINE, EBSCO CINAHL Plus, JBI Evidence Synthesis, Scopus and Embase, as well as clinical registries, with qualitative and quantitative studies sourced. Data analysis will involve a numerical summary and thematic analysis. Findings will be presented through themes, tables and/or diagrams, with a descriptive format for qualitative studies.

Ethics and dissemination Ethics approval is not required as data will be sourced from publicly available materials. Findings will be disseminated through a peer-reviewed journal, conferences and social media. Consultation will be undertaken with patients and health professionals.

Article summary

Strengths and limitations

- This scoping review protocol is the first to map HAPI prevention in high BMI patients.

- The PRISMA-ScR checklist will be utilised to guide a systematic approach.

- A comprehensive search strategy and data extraction template is included.

- Studies published outside of the searched databases may be missed.

Introduction

Pressure injuries (PIs) may be referred to as pressure ulcers, pressure injury, bedsores or pressure sores. A PI is defined as “localised damage to the skin and/or underlying tissue, as a result of pressure or pressure in combination with shear”1. Hospital-acquired pressure injuries (HAPI) are PIs that develop during hospitalisation and are associated with worse health outcomes, reduced quality of life and significant healthcare costs2. The majority of HAPIs are preventable through interventions by healthcare workers, carers and patients3.

Body mass index (BMI) is a screening method for weight and is calculated by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by the square of height in metres. BMI categories have been developed by the World Health Organisation and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and a BMI over 30 is considered obese4. Obesity can be defined as “abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health”5. This review will use the term ‘high BMI’ and include adults aged 18 and over with a BMI of 30.0 or higher.

Skin changes are common in high BMI patients and may result in skin damage, impaired healing, and moisture lesions. Excess weight can cause changes to the lymphatic system, collagen function and micro and macro circulation. Heat retention and excessive sweating commonly occur in high BMI people and, in between skin folds, maceration and microorganism growth can result6. Heavy adipose tissue resting on areas of skin increases risk of friction and shear, skin tears, PIs and maceration7. Further patient-related contributing factors for PI development in high BMI individuals in acute care settings include poor flexion, mobility, and underlying health conditions. Healthcare-related factors include inadequate staffing and equipment8.

Studies investigating the association between a high BMI and HAPI in acute care are limited with contrasting reports. A U-shaped relationship where incidence of HAPI was highest in low and high BMI patients has been found in three studies2,9,10, while some research indicates body fat may have a protective effect on PI occurrence11. The odds of developing a medical or therapeutic device related PI have been found to be significantly increased with increased weight12. There is minimal information on the severity of PIs developed in high BMI patients, indicating the need for a systematic search to map available evidence of HAPI prevalence, severity, prevention practices, and nurses’ experiences in association with patients who have a BMI of 30.0 or higher.

Current best practice recommendations for high BMI patients to prevent development of HAPI involves a multifactorial approach including a risk assessment, nutritional management, providing redistribution support surfaces, appropriate equipment, prophylactic dressings, repositioning and skin care1,13–15. It is recommended clinical judgement and/or a risk assessment tool is used. The Waterlow Scale, Norton Scale, and the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk are the most used risk assessment tools in Australia and New Zealand intensive care units (ICUs)16; however, there is no evidence that these tools accurately predict risk or reduce HAPI occurrence17. No single risk assessment tool reflects all relevant PI risk factors and has not been validated for use in the high BMI population18.

Performing a skin assessment in high BMI patients has additional challenges and considerations. Patients with a high BMI can develop PIs between skin folds due to a combination of factors including trapped moisture in skin folds, pressure of skin folds on underlying skin, and friction and shear between skin surfaces1. Skin folds in high BMI patients can become macerated from moisture and need to be kept dry13. Skin needs to be cleaned at least twice daily, with non-soap and non-alcohol based cleansers, gently dried, and emollient applied to prevent dryness15. Deep skin folds can be kept dry by using soft cloths and drying products such as antifungal powder and moisture-wicking fabric with antimicrobial silver14.

A collaborative approach across different health disciplines including nurses, physiotherapists, dieticians and equipment coordinators is required to optimally care for high BMI patients and prevent HAPIs19. Patients need to be educated about PI prevention to promote shared decision making and participation, which may lead to increased patient satisfaction, safety and decreased length of stay20.

Prophylactic soft, silicone foam dressings have been found effective in absorbing pressure and shear loads to prevent PI21. Freeing heels from pressure of a support surface by elevation with a pillow or foam cushion and daily skin assessment is necessary1.

High BMI patients may need a bariatric support surface. The weight limit of support surfaces should be checked and not exceeded, and surfaces be monitored for ‘bottoming out’ which occurs from excessive immersion from the individual, making the bed or chair base the only support22. There are no firm conclusions about which support surface is best for treating PIs due to low quality evidence23. Support surfaces that optimise pressure redistribution and microclimate control should be utilised for high BMI patients1. Microclimate control allows air to escape from the air cells, thereby managing skin heat and humidity16.

Repositioning a patient changes the area of increased interface pressure. Manual lifting should be avoided in high BMI patients for staff and patient safety24. Aids such as side rails or an overhead can assist patients to self-reposition. The pannus should be supported away from underlying tissue22. Some manufacturers have developed bed tilting mechanisms to reduce workload; however, comparing manual repositioning to bed tilting mechanisms found no difference in tissue interface pressures or comfort scores. When repositioning, air-assist technology should be used if available to decrease the patient load to 10% of actual weight24.

High BMI patients need their height and weight measured on admission to ensure appropriate equipment is obtained25. Appropriately sized beds ensure there is sufficient space for side to side movement13. Siderails and armrests inappropriately sized can contribute to HAPI at patient’s hips or torso26. Hospital units should have safe patient handling policies to ensure transfer and repositioning of high BMI patients does not cause injuries to staff or patients. These guidelines should include equipment weight limits, the number of staff required according to the patient’s weight, and protocols to address staff and patient injuries14.

Optimal nutritional status is associated with preventing and healing PIs. Undernutrition and obesity are often linked; these patients can be protein-deficient and lack essential vitamins and minerals required for wound healing15. Ness e al.9 found malnourished high BMI patients had 11 times the odds of well-nourished high BMI patients for developing a PI.

Current literature reports nurses’ experiences of HAPI and high BMI patients are impacted by numerous factors including equipment, staffing levels, paperwork, nurse and patient education, and attitudes. A common theme was increased nurse effort needed to care for high BMI patients and absence of appropriate equipment27.

In addition, healthcare professionals’ negative attitudes towards high BMI patients can result in actions or a lack of actions which can impact a patient’s health and care they receive14. Weight bias amongst healthcare professionals can impair communication and patient satisfaction. It has been found most health professions have negative stereotypes of high BMI people as being lazy, non-compliant, lacking wil power, and having poor personal hygiene28.

Rationale

The association between a high BMI and PI incidence in acute care has been recognised9, as has the need for additional care approaches for HAPI prevention in high BMI patients1. However, there is minimal recent research relating to preventing HAPIs for high BMI patients. We are not aware of any research that has been conducted regarding BMI influence on incidence and severity of HAPI. This scoping review will address issues associated with quality and safety, cost, and patient and clinician knowledge gaps relating to high BMI patients and HAPI prevention.

The European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP), and the Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA) have documented in their latest PI prevention and management guidelines that there is limited research available in the high BMI population1.

Australia’s public health crisis related to high BMI generates a significant concern with the number of people with a high BMI rising. Preventing HAPI is a priority in healthcare and is a focus of the National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS): Comprehensive Care Standard. High BMI patients can have longer hospital stays, increased likelihood of intensive care admission, and greater risk of readmission to hospital within 28 days of discharge29.

HAPIs place a high economic burden in healthcare. A single HAPI case can incur an average cost of A$22,466 per case in Australia9. PI treatment costs 2.5 times more than its prevention. The Queensland government has applied financial penalties for each reported case of healthcare-acquired Stag 3 (A$30,000) and Stag 4 (A$50,000) PIs30.

However, Chaboyer e al.20 reported just over a third of 799 patients received education on PI prevention strategies. Team e al.31 investigated 212 hospital websites and found more than half lacked educational materials for patients, carers and families to prevent and manage PIs.

Furthermore, multiple studies have found nurses lack knowledge in PI prevention32–37; this can negatively affect nurses’ attitudes towards HAPI prevention36. Healthcare professionals have a responsibility to provide evidenced-based quality care which requires continuing professional development including accurate, up-to-date knowledge on PI prevention to prevent HAPI36. However, the lack of educational material and limited clinician knowledge impacts on the healthcare professional’s ability to provide evidenced-based quality care, highlighting the need for further research in high BMI patients and HAPI prevention.

To improve quality of care for the high BMI population and address the current educational gap, research is needed to clarify best practices in HAPI prevention in high BMI patients, identify the occurrence and severity of HAPI in high BMI patients, and discover nurses’ experiences with this group. Reducing incidence of PIs can lead to decreasing healthcare costs and reduce the negative impacts for patients, families, carers and hospital workers. This scoping review will assist in guiding the development of an online module for healthcare professionals in HAPI prevention in high BMI patients.

Aim

The aim of this scoping review is to explore the current research examining best practices for HAPI prevention in high BMI patients. We also plan to identify nurses’ experiences in preventing and/or managing HAPIs in high BMI patients, and whether there is an association between a high BMI and occurrence and severity of HAPI.

Protocol development

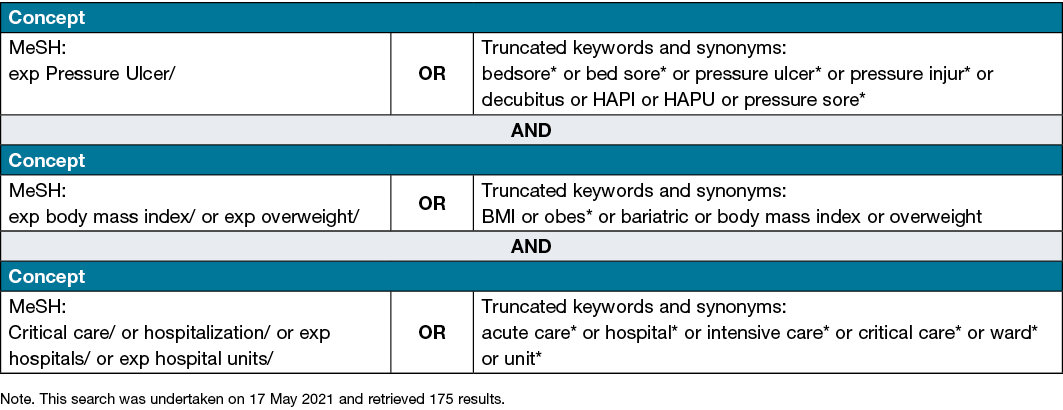

The review will be guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Appendi A). The six framework stages originally developed by Arksey and O’Malley38 and further enhanced by Levac e al.39 will outline the methods for this scoping review.

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

Primary research question:

(a) What are the best practices for HAPI prevention in people with a BMI of 30 or higher?

Sub-questions include:

(b) What are nurses’ experiences in preventing and/or managing HAPIs in people with a BMI of 30.0 or higher?

(c) Is there an association between a BMI of 30.0 or higher and occurrence and severity of HAPI?

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

This search strategy was developed by guidance from a librarian and will be sensitive and extensive. Electronic bibliographic databases to be searched include Ovid MEDLINE, EBSCO CINAHL Plus, JBI Evidence Synthesis, Scopus and Embase. Clinical trial registries will be searched as will grey literature through Google Scholar and Open Grey. The JBI recommends a three-phase search strategy be used40.

- Phase 1: The search will initially be conducted through two relevant databases, Ovid MEDLINE and CINAHL. The title, abstracts and index terms of retrieved studies will be analysed for descriptive text words.

- Phase 2: Keywords and terms identified in Phas 1 will be searched in included databases to retrieve a comprehensive and specific search.

- Phase 3: The reference lists of all relevant studies will be manually searched for additional studies.

Evidence published from 2009 onwards will be considered for inclusion. The first international clinical practice guideline for PI prevention and treatment was developed in 2009 by the NPIAP and the EPUAP41. Given best practice guidelines have been in place since 2009, studies published prior to this will not be included. Clinical practice guidelines include recommendations for optimal patient care which are gathered by a systematic review of evidence. Studies published only in the English language will be considered as the practical use of a translator will be challenging to incorporate in the timeframe proposed.

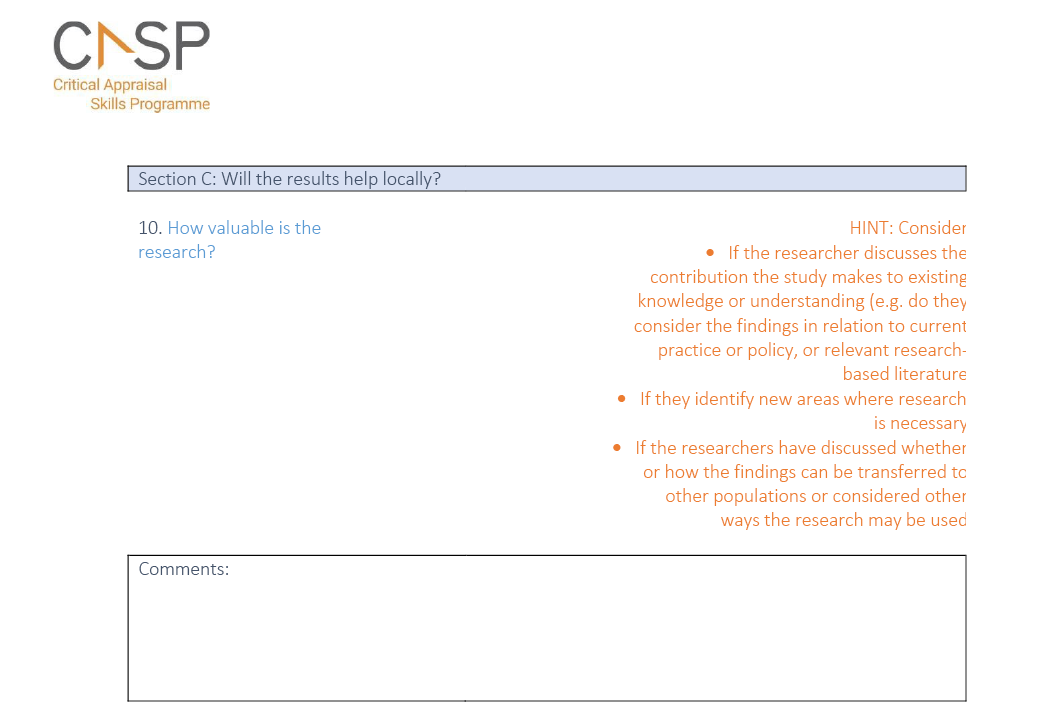

Searching using only terms in titles and abstracts can result in relevant articles being missed42. Searching with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) will be used to increase precision and efficiency. Excerpta Medica Thesaurus (Emtree terms) will be used in Embase; this contains highly specific terms and produces considerable coverage and recall42 therefore is an important factor for choosing this database.

Boolean operator ‘OR’ will be used to group synonyms and ‘AND’ to group components together (Table 1). Truncation/wildcard symbols and phrases requiring double quotes will be tailored to each database. The asterisk ‘*’ will be used at the end of words to retrieve suffix variations for all databases.

Table 1. Ovid MEDLINE search strategy

Each search will be checked for errors, such as missing Boolean operator ‘OR’ which could reduce search results. Clues for errors may be found in the number of search results, being higher or lower than expected42. If irrelevant results are found due to certain keywords, the search will be modified.

Stage 3: Study selection

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria are deliberately broad, given the preliminary search identified limited literature on this topic. The inclusion criteria are outlined below relating to participants, concepts, contexts, study types and reported outcomes.

- Participants: Patients aged 18 and over with a BMI of 30 or higher. People with a BMI over 30 are classified as obese5.

- Concepts: The concept to be explored includes best practices in HAPI prevention in high BMI patients, nurses’ experiences with HAPI prevention in high BMI patients, and if there is an association between incidence and severity of HAPIs in high BMI patients.

- Contexts: Acute care settings have specifically been chosen due to the limited research currently available and acute care settings in Australia account for 39% of healthcare spending43. Acute care settings including critical care and operative areas. Critical care areas such as ICUs will be included due to the burden of PIs in ICU worldwide as found in the Decubitus in intensive care units study44.

- Study types: Quantitative and qualitative research will be sourced. All studies will be considered regardless of design. Abstracts found need to have the full text available.

- Reported outcomes: Literature relating to best preventative practices currently used for high BMI patients in acute care settings including risk assessment tools, clinical judgement, support surfaces, dressings, equipment, repositioning, and nutrition. Nurses’ experiences with high BMI patients and HAPI prevention in acute care settings regarding availability of equipment, healthcare personnel, and safety issues relating to repositioning. Nurses’ knowledge and skills with HAPI in high BMI individuals will expectantly be identified. Studies relating to incidence and severity of PIs developed in high BMI individuals in acute care areas will be explored.

Exclusion criteria

- Patients with a BMI under 30.

- Incontinence-associated dermatitis; this skin condition can often be misclassified as a PI3.

- Patients admitted to hospital with a community-acquired PI will not be included in incidence and severity; however, preventative strategies used in the acute care setting to prevent deterioration of the PI will be included.

- Non-acute or critical care settings such as rehabilitation, home care or nursing homes will be excluded. Multiple studies have investigated nurses’ experiences with high BMI patients in nursing homes27,45, but limited studies investigate nurses’ experiences with this group in acute care setting and in association with HAPI.

A two-stage process will be used to screen and select studies.

- Stage 1: Initial screening will check titles and abstracts of retrieved articles against the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies which meet inclusion criteria and include at least one outcome measure of interest will be retained. All potential studies will be stored in a separate EndNote library.

- Stage 2: Full texts of all potential studies will be sourced, and eligibility assessed using the inclusion criteria.

The studies will be assessed by two independent reviewers; if disagreement occurs within a study, a third reviewer may be called for their opinion. Disagreements and resolutions will be recorded.

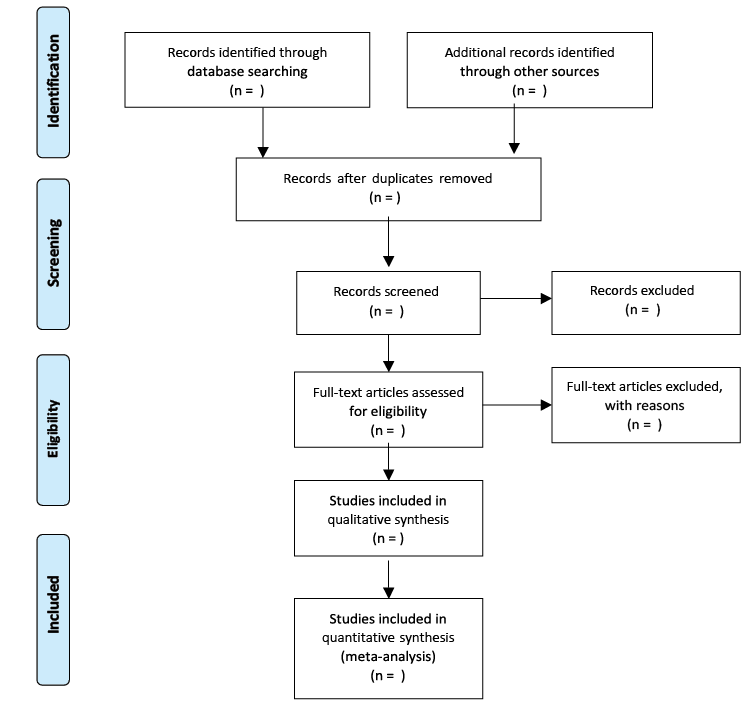

A checklist specifying the inclusion criteria will ensure screening articles will be done efficiently and prevent ineligible studies from progressing46. The PRISMA 2009 flow diagram (Appendi B) will be used to outline the retrieved, assessed, excluded and included study numbers.

Stage 4: Charting the data

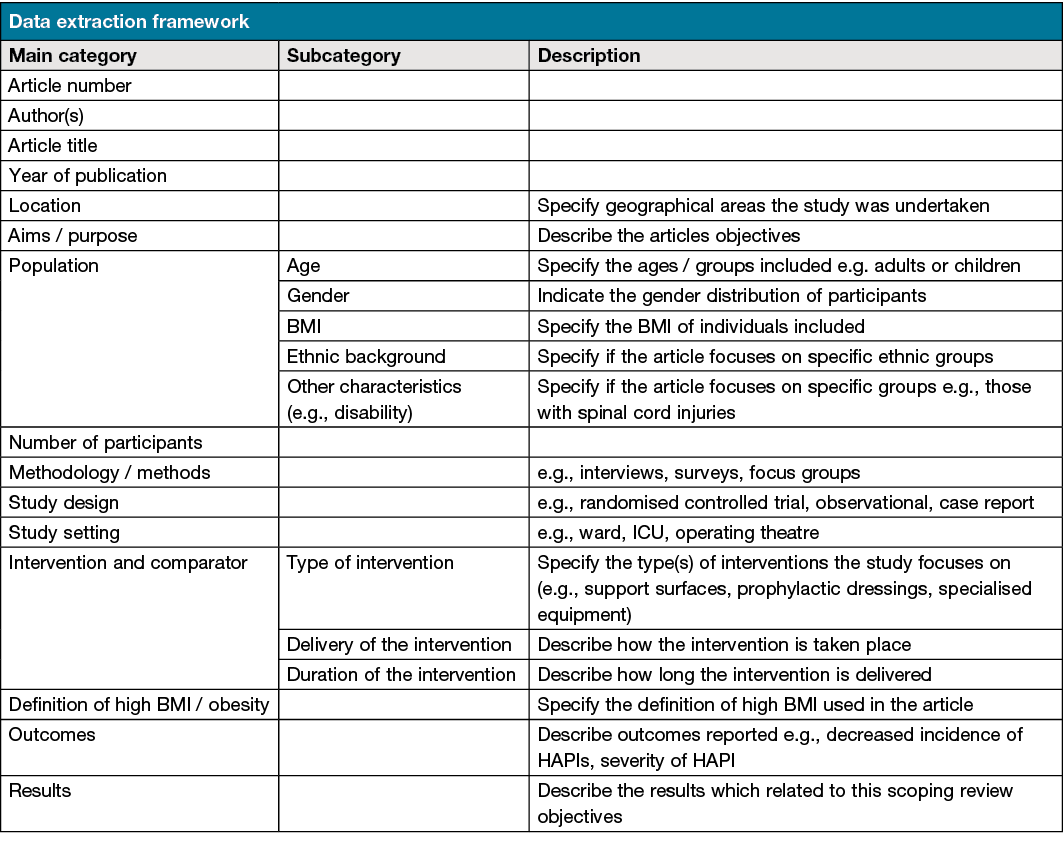

Covidence will be utilised to chart the data. Each included study will be assessed using a data extraction template which has been developed and is provided in Appendi C. This includes bibliographical information, objectives, interventions, methods and results relevant to this scoping review aim.

Two independent reviewers will undertake a pilot test on a sample of the included studies (10% of the total included studies) to ensure the coding framework is consistent. Each paper will be assigned an identifying number to provide a useful way to discuss a particular article in the research team without citing the full reference or becoming confused by the names of authors who may have published multiple papers47. If additional unforeseen data becomes apparent, the charting table will be updated accordingly. The reference management software EndNote will be used to import results and identify duplicate articles to be removed from the results pool.

Data will be presented into three different areas relating to each research question – best clinical practices in HAPI prevention in high BMI patients, nurses’ experiences in caring for high BMI patients and HAPI prevention, and occurrence and severity of HAPI in high BMI patients.

Stage 5: Collating, summarising and reporting the results

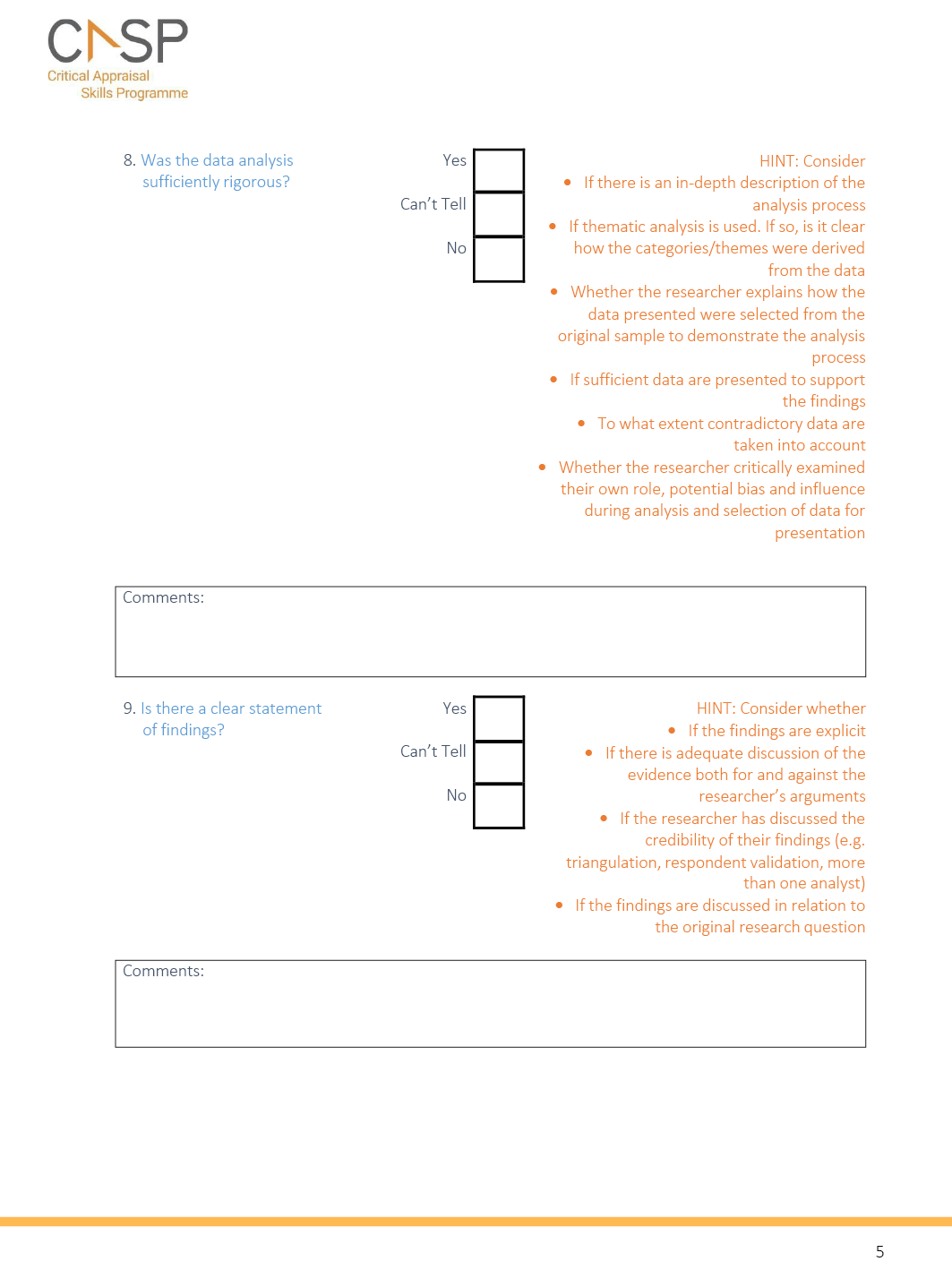

Retained studies will be examined to assess credibility, value and relevance to clinical practice. The quality and validity of included studies will be assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programmes (CASP) checklist, which will be used for qualitative studies (Appendi D) and for quantitative studies; each quantitative article’s study design will be matched to the appropriate quantitative CASP checklist.

As scoping review studies have been criticised for lacking detail about how results were achieved39, these findings will be reported in a rigorous manner as suggested in the three steps below:

- Step 1: Analysing the data involving a numerical summary and thematic analysis. Characteristics of included studies will be presented in a table that outlines the study type, study year, sample size, location and patient characteristics.

- Step 2: Depending on findings, results will be presented through themes, with a table of strengths and gaps identified. The data will be summarised using tables and/or diagrams, and a descriptive format will be used for qualitative studies included. Commonalities identified between studies will be synthesised and presented.

- Step 3: Results yielded aim to describe clinical practices specific to HAPI prevention in the high BMI population, if high BMI influences the incidence and severity of PIs, and nurses’ experiences of HAPI prevention in patients with a high BMI. We aim to identify research gaps in these areas and anticipate there will be, given the low search results initially retrieved.

Stage 6: Consultation: patient and public involvement

This scoping review is the initial part of a larger collaborative research project in developing an online module for health professionals on PI prevention and management in high BMI patients. By consulting with healthcare personnel, we hope to identify what is working well in this area as well as barriers and areas needed for improvement. At the beginning of this scoping review, seven to ten semi-structured interviews will be collected with nurses about experiences of caring for people with a high BMI and HAPI prevention. This consultation phase is part of our patient and public involvement strategy as we will work actively in partnership with patients and healthcare professionals to plan and design future PI prevention strategies. Health services, clinicians and patients will be informed of the findings of best preventative practices for HAPI in high BMI patients, nurses’ experiences of HAPI in high BMI patients, and whether there is an association between HAPI incidence and severity in high BMI patients to facilitate knowledge translation.

Ethics and dissemination

This scoping review methodology will be based upon data collected from publicly available materials; therefore, ethics approval will not be required. Fundamental ethical principles will be guided by the Declaration of Helsinki. If ethical insufficiencies are found from articles included, they will be mentioned. Informed consent and financial conflict of interest will be assessed in included studies. If ethical considerations are not sufficiently reported it may be necessary to contact the authors to obtain further information.

Through the consultation step outlined above, the research findings will be shared with relevant audiences involved in PI prevention and management, including health services, clinicians and patients, enabling the research findings to be translated into policy and practice. This scoping review will be published in a peer-reviewed journal to distribute the findings to the wider wound care and prevention community reaching global audiences. The link to the final review will be promoted through social media platforms including LinkedIn and Twitter.

Conclusion

The findings will aid health professionals who care for people with a high BMI as well as high BMI patients admitted to acute care settings. This review may inform evidence-based practice strategies for HAPI prevention tailored specifically to high BMI patients, leading to improved care quality and knowledge. Findings from all available qualitative and quantitative studies in this scoping review will guide the development of an online module for health professionals on PI prevention in high BMI patients. The scoping review methodology will clarify key concepts outlined, identify gaps in current clinical practice with high BMI patients and HAPI prevention, and determine the coverage of literature on this topic.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge this protocol has been deposited in OSF repository DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/DA3H2. The authors wish to thank Cassandra Freeman, subject librarian for medicine, nursing and health sciences at Monash University, for her assistance in developing the search strategies.

CW and VT conceptualised the main ideas for this scoping review. VM worked with CF to develop the search strategy. All authors contributed to the framework for this protocol. VM produced the first draft with support from CW and VT. CW and VT provided critical feedback, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Author(s)

Victoria Marshall1 CCRN, BN, MN student

Victoria Team1 MD, MPH, DrPH

Carolina Weller1* RN, PhD

Email carolina.weller@monash.edu

1School of Nursing and Midwifery

Monash University, Level 5 Alfred Centre

99 Commercial Road, Melbourne VIC 3004 Australia

* Corresponding author

References

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP), and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA). Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: clinical practice guideline. In: Hasler E, editor. The international guideline. EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA; 2019.

- Kayser SA, VanGilder CA, Lachenbruch C. Predictors of superficial and severe hospital-acquired pressure injuries: a cross-sectional study using the International Pressure Ulcer Prevalence™ survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2019;89:46–52. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.09.003

- Barakat-Johnson M, Lai M, Wand T, White K. A qualitative study of the thoughts and experiences of hospital nurses providing pressure injury prevention and management. Collegian 2019;26(1):95–102. doi:10.1016/j.colegn.2018.04.005

- Zierle-Ghosh A, Jan A. Physiology, body mass index: StatPearls [Internet]; 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535456/.

- Chooi YC, Ding C, Magkos F. The epidemiology of obesity. Metabolism Clin Experiment 2019;92(1):6–10. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2018.09.005

- Earlam AS, Woods L. Obesity: Skin issues and skinfold management. Am Nurse J 2020. Available from: https://www.myamericannurse.com/obesity-skin-issues-and-skinfold-management/.

- Hirt PA, Castillo DE, Yosipovitch G, Keri JE. Skin changes in the obese patient. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;81(5):1037–57. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.070

- Baronoski S. Skin conditions frequently found in obese patient populations. Wound Source; 2018. Available from: www.woundsource.com/blog/skin-conditions-frequently-found-in-obese-patient-populations.

- Ness SJ, Hickling DF, Bell JJ, Collins PF. The pressures of obesity: the relationship between obesity, malnutrition and pressure injuries in hospital inpatients. Clin Nutr 2018;37(5):1569–74. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2017.08.014

- Peixoto CA, Ferreira MBG, Felix MMS, Pires PS, Barichello E, Barbosa MH. Risk assessment for perioperative pressure injuries. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 2019;27(e3117):1–11. doi:10.1590/1518-8345.2677-3117

- Grosschadl F, Bauer S. The relationship between obesity and nursing care problems in intensive care patients in Austria. Nurs Crit Care 2020.

- Coyer F, Barakat-Johnson M, Campbell J, Palmer J, Parke RL, Hammond NE, et al. Device-related pressure injuries in adult intensive care unit patients: an Australian and New Zealand point prevalence study. Aust Crit Care 2021:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.aucc.2020.12.011

- Alderden JG, Shibily F, Cowan L. Best practice in pressure injury prevention among critical care patients. Crit Care Nurs Clinic North Am 2020;32(4):489–500. doi:10.1016/j.cnc.2020.08.001

- Berrios LA. The ABCDs of managing morbidly obese patients in intensive care units. Crit Care Nurse 2016;36(5):17–26. doi:10.4037/ccn2016671

- Lloyd-Jones M. Series 5, chronic wounds; part 4h. Pressure ulcer care of the obese patient. Br J Healthcare Assist 2021;15(1). doi:10.12968/bjha.2021.15.1.22

- Yarad E, O’Connor A, Meyer J, Tinker M, Knowles S, Li Y, e al. Prevalence of pressure injuries and the management of support surfaces (mattresses) in adult intensive care patients: a multicentre point prevalence study in Australia and New Zealand. Aust Critical Care 2021;34(1):60–6. doi:10.1016/j.aucc.2020.04.153

- Latimer S. Pressure injury prevention and the role of the patient: a mixed methods study. School Nurs Midwifery 2016:227. doi:10.25904/1912/1193

- Beitz JM. Providing quality skin and wound care for the bariatric patient: an overview of clinical challenges. Ostomy Wound Manage 2014;60(1):12–21.

- Temple G, Gallagher S, Doms J, Tonks M, Mercer D, Ford D. Bariatric readiness: economic and clinical implications. Bariatric Times 2017;14(8):10–6.

- Chaboyer W, Bucknall T, Gillespie B, Thalib L, McInnes E, Considine J, e al. Adherence to evidence-based pressure injury prevention guidelines in routine clinical practice: a longitudinal study. Int Wound J 2017;14(6):1290–8. doi:10.1111/iwj.12798

- Yoshimura M, Ohura N, Santamaria N, Watanabe Y, Akizuki T, Gefen A. High body mass index is a strong predictor of intraoperative acquired pressure injury in spinal surgery patients when prophylactic film dressings are applied: a retrospective analysis prior to the BOSS trial. Int Wound J 2020;17(3):660–9. doi:10.1111/iwj.13287

- Haesler E. Evidence summary: prevention of pressure injuries in individuals with overweight or obesity. Wound Practice & Res 2018;26(3):158–61.

- McInnes E, Jammali-Blasi A, Bell-Syer SEM, Leung V. Support surfaces for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database System Rev 2018(10). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009490.pub2

- Pritts W. Confidently caring for critically ill overweight and obese adults. Nurs Critical Care 2020;15(1):16–22. doi:10.1097/01.CCN.0000612872.24708.cb

- Dambaugh LA, Ecklund MM. Progressive care of obese patients. Crit Care Nurse 2016;36(4):58–63. doi:10.4037/ccn2016510

- Holsworth C, Gallagher S. Managing care of critically ill bariatric patients. AACN Adv Crit Care 2017;28(3):275–83. doi:10.4037/aacnacc2017342

- Harris JA, Castle NG. Obesity and nursing home care in the United States: a systematic review. Gerontologist 2019;59(3):e196-e206. doi:10.1093/geront/gnx128

- Tanneberger A, Ciupitu-Plath C. Nurses’ weight bias in caring for obese patients: do weight controllability beliefs influence the provision of care to obese patients? Clin Nurs Res 2018;27(4):414–32. doi:10.1177/1054773816687443

- Fusco KL, Robertson HC, Galindo H, Hakendorf PH, Thompson CH. Clinical outcomes for the obese hospital inpatient: an observational study. SAGE Open Med 2017;5:1–6. doi:10.1177/2050312117700065

- Magid B, Murphy C, Lankiewicz J, Lawandi N, Poulton A. Pricing for safety and quality in healthcare: a discussion paper. Infection, Dis Health 2018;23(1):49–53. doi:10.1016/j.idh.2017.10.001

- Team V, Bouguettaya A, Richards C, Turnour L, Jones A, Teede H, et al. Patient education materials of pressure injury prevention in hospitals and health services in Victoria, Australia: availability and content analysis. Int Wound J 2020;17:370–9. doi:10.1111/jan.12208

- Dalvand S, Ebadi A, Geshlagh RG. Nurses’ knowledge on pressure injury prevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on the Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Assessment Tool. Clin, Cosmetic Investigat Dermatol 2018;11(1):613–20. doi:10.2147/CCID.S186381

- De Meyer D, Verhaeghe S, Van Hecke A, Beeckman D. Knowledge of nurses and nursing assistants about pressure ulcer prevention: a survey in 16 Belgian hospitals using the PUKAT 2.0 tool. J Tissue Viab 2019;28(2):59–69. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2019.03.002

- Fulbrook P, Lawrence P, Miles S. Australian nurses’ knowledge of pressure injury prevention and management: a cross-sectional survey. J WOCN 2019;46(2):106–12. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000508

- Halasz BG, Beresova A, Tkacova L, Magurova D, Lizakova L. Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards prevention of pressure ulcers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(4):1705. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041705

- Tirgani B, Mirshekari L, Forouzi MA. Pressure injury prevention: knowledge and attitudes on Iranian intensive care nurses. Adv Skin Wound Care 2018;34(4):1–8. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000530848.50085.ef

- Walker CA, Rahman A, Gipson-Jones TL, Harris CM. Hospitalists’ needs assessment and perceived barriers in wound care management: a quality improvement project. J WOCN 2019;46(2):98–105. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000512

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119619

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5(69):1–9. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI manual for evidence synthesis: 10.2.6 search strategy; 2020. Available from: https://wiki.jbi.global/display/MANUAL/10.2.6+Search+Strategy.

- Kottner J, Cuddigan J, Carville K, Balzer K, Berlowitz D, Law S, et al. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: the protocol for the second update of the international clinical practice guideline 2019. J Tissue Viability 2019;28(2):51–8. doi:10.1016/j.jtv.2019.01.001

- Bramer WM, Giustini D, Kleijnen J, Franco OH. Searching Embase and Medline using only major descriptors or title and abstract fields: a prospective exploratory study. Systematic Rev 2018;7(200):1–8. doi:10.1186/s13643-018-0864-9

- Rodgers K, Sim J, Clifton R. Systematic review of pressure injury prevalence in Australian and New Zealand hospitals. Collegian 2020;27(4):471–5. doi:10.1016/j.colegn.2020.08.012

- Labeau SO, Afonso E, Benbenishty J, Blackwood B, Boulander C, Brett SJ, et al. Prevalence, associated factors and outcomes of pressure injuries in adult intensive care unit patients: the DecubICUs study. Intensive Care Medicine. 2021;47(2): 160-9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06234-9

- Felix HC, Bradway C, Ali MM, Li X. Nursing home perspectives on the admission of morbidly obese patients from hospitals to nursing homes. J App Gerontol 2016;35(3):286–302. doi:10.1177/0733464814563606

- Hornberger B, Rangu S. Designing inclusion and exclusion criteria. ScholarlyCommons; 2020.

- Daudt HML, Van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13(48):1–9. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

Appendix A. PRISMA-ScR checklist

Appendix B. PRISMA 2009 flow diagram

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535

Appendix C. Data extraction framework template

Appendix D. CASP checklist