Volume 22 Number 1

Rare ulcer in a neonate: Experience using topical oxygen therapy based on the M.O.I.S.T. Principle

Chin Yen Lee, Yun Ying Ho, Mohanaprakash Arasappan, Yeang Wee Koay, Jacob Abraham

Keywords neonate, Haemoglobin spray, internal iliac artery thrombosis, ischaemic wound, topical oxygen therapy

DOI 10.35279/jowm202104.07

Abstract

Background Ischaemic wounds are notoriously difficult to treat, as poor perfusion often leads to chronic, non-healing wounds.

Aim This case study describes the successful treatment of an ischemic ulceration in a neonate using topical oxygen therapy (TOT).

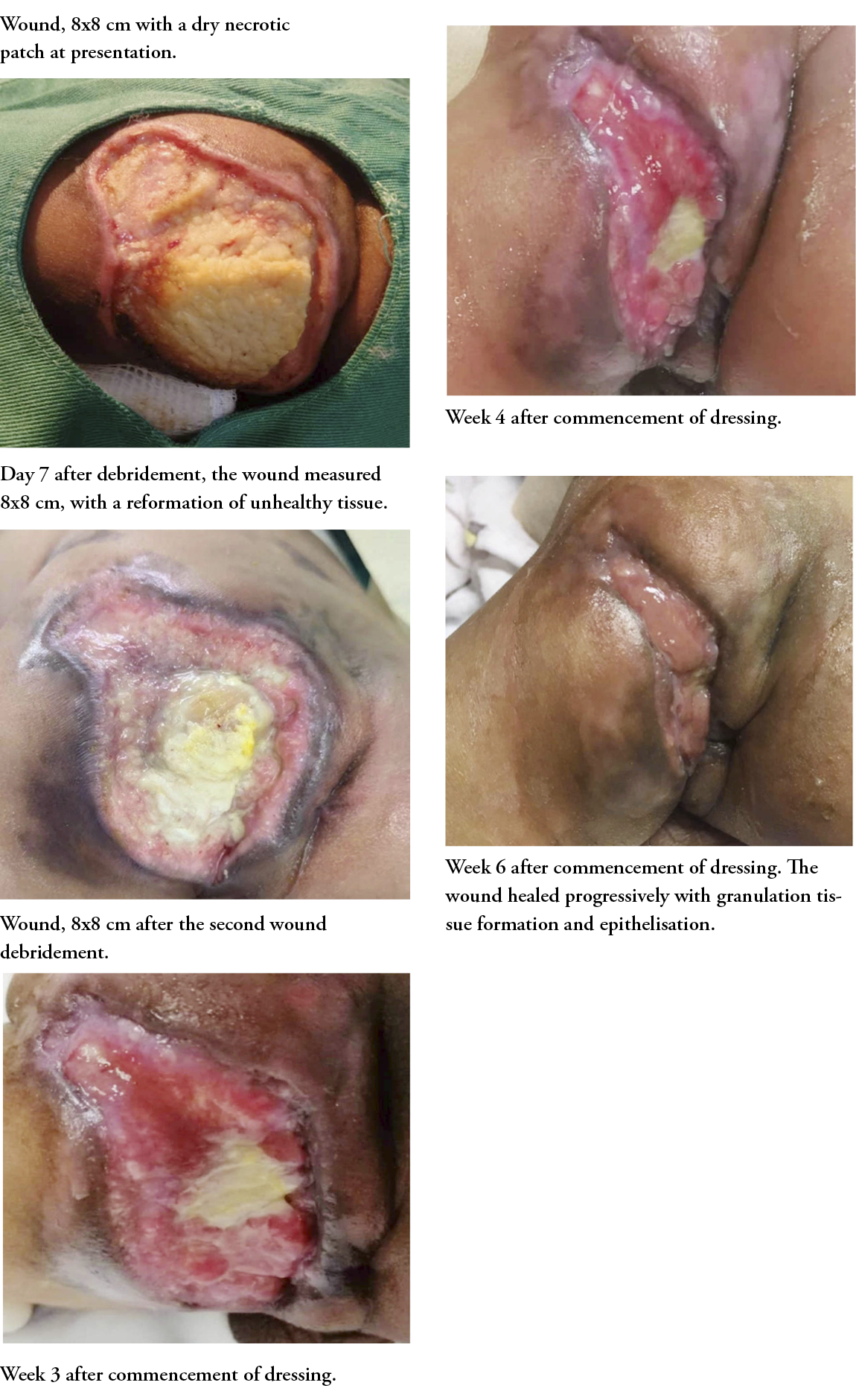

Methods A large necrotic ulceration quickly developed over the left gluteal area in a 2-week-old child and enlarged to cover the entire gluteal area in one week. The aetiology of the wound was ischaemic, due to internal iliac artery thrombosis after an umbilical vein catheterisation. The wound was initially managed using the standard of care and surgical debridement of the necrotic tissue with saline dressing; however, the condition worsened with the development of a new necrotic patch.

Topical oxygen therapy (TOT) was applied using the M.O.I.S.T. concept. After the second surgical debridement, TOT in the form of haemoglobin spray was administered on alternate days and a moist dressing was applied.

Results / Findings The wound healed progressively, with granulation tissue formation and epithelisation after 6 weeks.

Conclusions Wound management in neonates is extremely challenging, due to their relatively small physical size and the preference for less invasive management strategies.

Implications for clinical practice TOT has proven to be an easily accessible, efficacious, non-invasive and cost-effective method for treating ischaemic wounds in neonates.

BACKGROUND

Adequate oxygenation is one of the keys for achieving wound healing. Oxygen plays a pivotal role throughout the process of normal wound healing, namely for controlling inflammation and proliferation and tissue remodelling.1 During the inflammatory stage of the wound-healing process, the respiratory burst of activated phagocytes consumes oxygen to produce reactive oxygen species. A similar process happens when a wound becomes infected. Besides that, oxygen is vital for activating the transcription factors that promote angiogenesis stimulated by lactate production by the NADPH oxidase of phagocytes. The rate of connective tissue formation is also heavily dependent on oxygen availability for fibroblast proliferation and collagen maturation.2

Many chronic wounds develop when the partial pressure of oxygen is below the critical hypoxic threshold level. Hypoxia can be caused by damaged vasculature, such as trauma, cardio-embolic or atherosclerotic processes, or other systemic conditions that lead to shock and poor perfusion. Diffusive constraints due to oedema and oxygen consumption by bacterial biofilm can also contribute to hypoxic wounds.2 Ischemic wounds are notoriously difficult to treat and often become chronic and non-healing.3 This leads to a vicious cycle, as neutrophil accumulation in chronic wounds due to ongoing tissue damage and debris further depletes oxygen in the wound bed, hence impeding wound healing.2

Providing supplemental oxygen to wounds has been shown to deliver nutrients and immunoglobulin, mobilise bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells and modulate redox-sensitive gene expression to accelerate wound healing and reduce rates of infection; this has traditionally been provided in the form of systemic hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). HBOT is defined as 100% oxygen delivered systemically at 2 to 3 times the atmospheric pressure to raise the partial pressure of oxygen systemically from 10 to 15 times the normal value, thus creating an oxygen diffusion gradient into hypoxic tissue to maintain transcutaneous oxygen levels (tcPO2) of 30 mmHg or greater, the optimal level for developing normal granulation.4 HBOT is also known to stimulate fibroblast proliferation and differentiation, promote collagen formation and cross-linking, encourage neovascularisation, reduce oedema and enhance leucocytes’ microbial-killing abilities.5

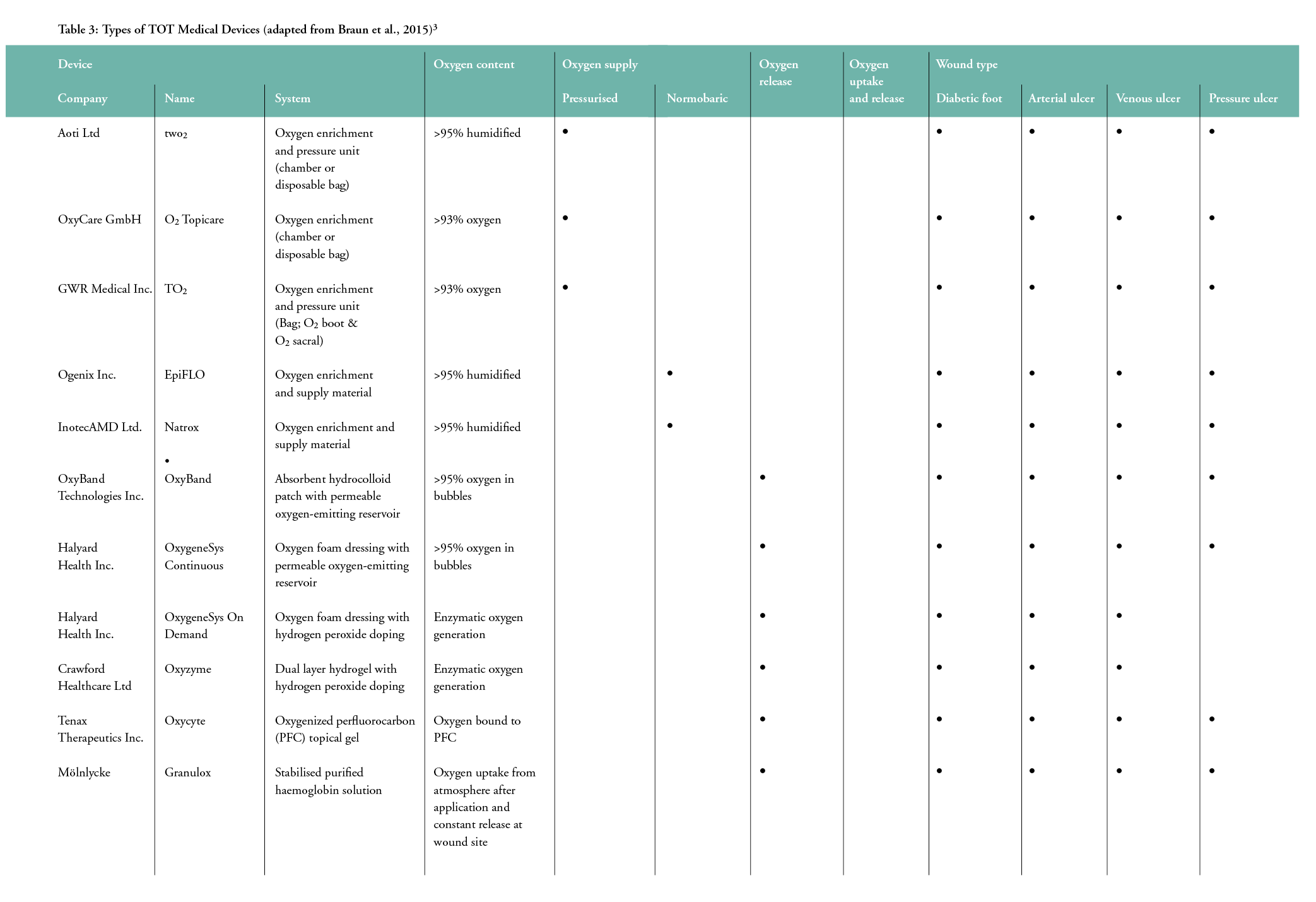

Recently, topical oxygen therapy (TOT) has emerged as a more promising alternative for delivering oxygen topically to wounds, as HBOT is limited by cost, availability and the risk of systemic oxygen toxicity. TOT is only effective when the oxygen delivered can diffuse through the tissue into oxygen-deficient cells. There are four main categories of TOT: (1) topical pressurised oxygen therapy (TPOT), (2) topical continuous oxygen therapy (TCOT), (3) wound dressings that release oxygen and (4) topical oxygen emulsion. A sustained increase in the level of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been shown in recent studies to be useful with TOT for promoting chronic wound closure in arterial and venous wounds and in pressure injuries.6

AIM

This case study illustrates the successful treatment of an ischemic ulceration in a neonate using TOT combined with the modern M.O.I.S.T. wound care concept. Wound care in the neonatal population is rudimentary and lacks evidence-based recommendations, so care protocols are largely adapted from adult guidelines.

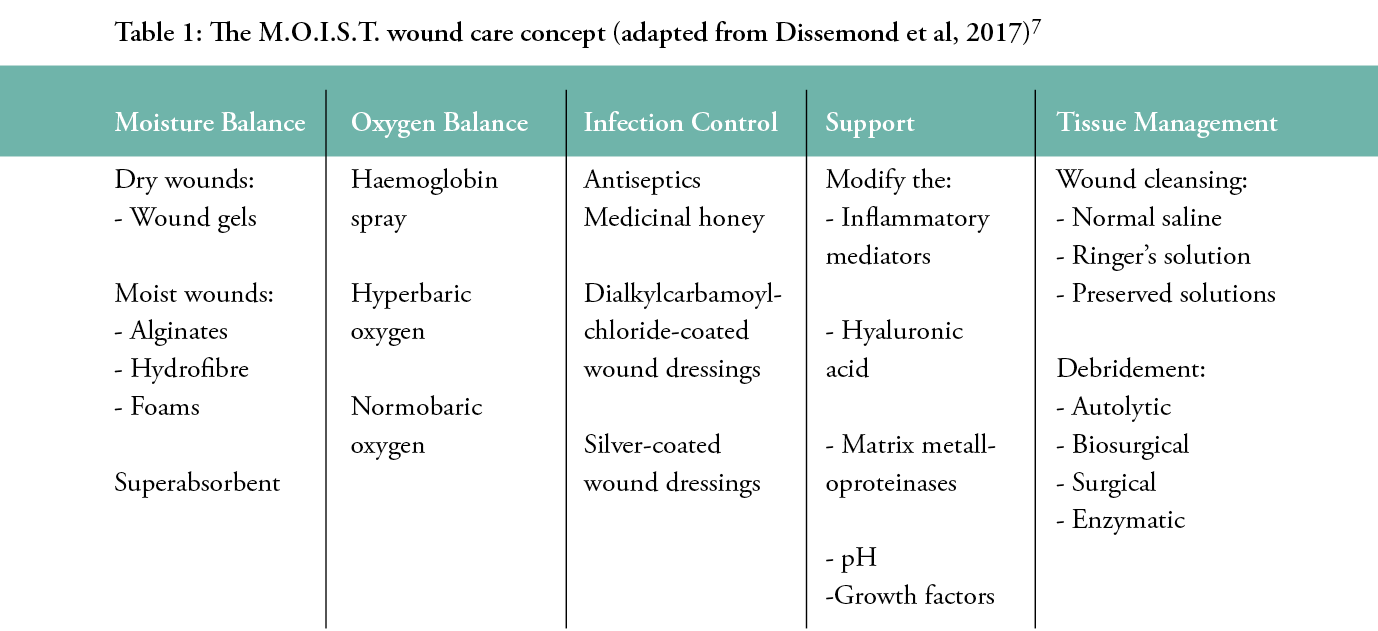

‘M.O.I.S.T.’ are the factors to consider when managing difficult-to-heal wounds. The acronym stands for Moisture balance, Oxygen balance, Infection control, Support and Tissue management.7 These factors form the basis for promoting moist wound healing.

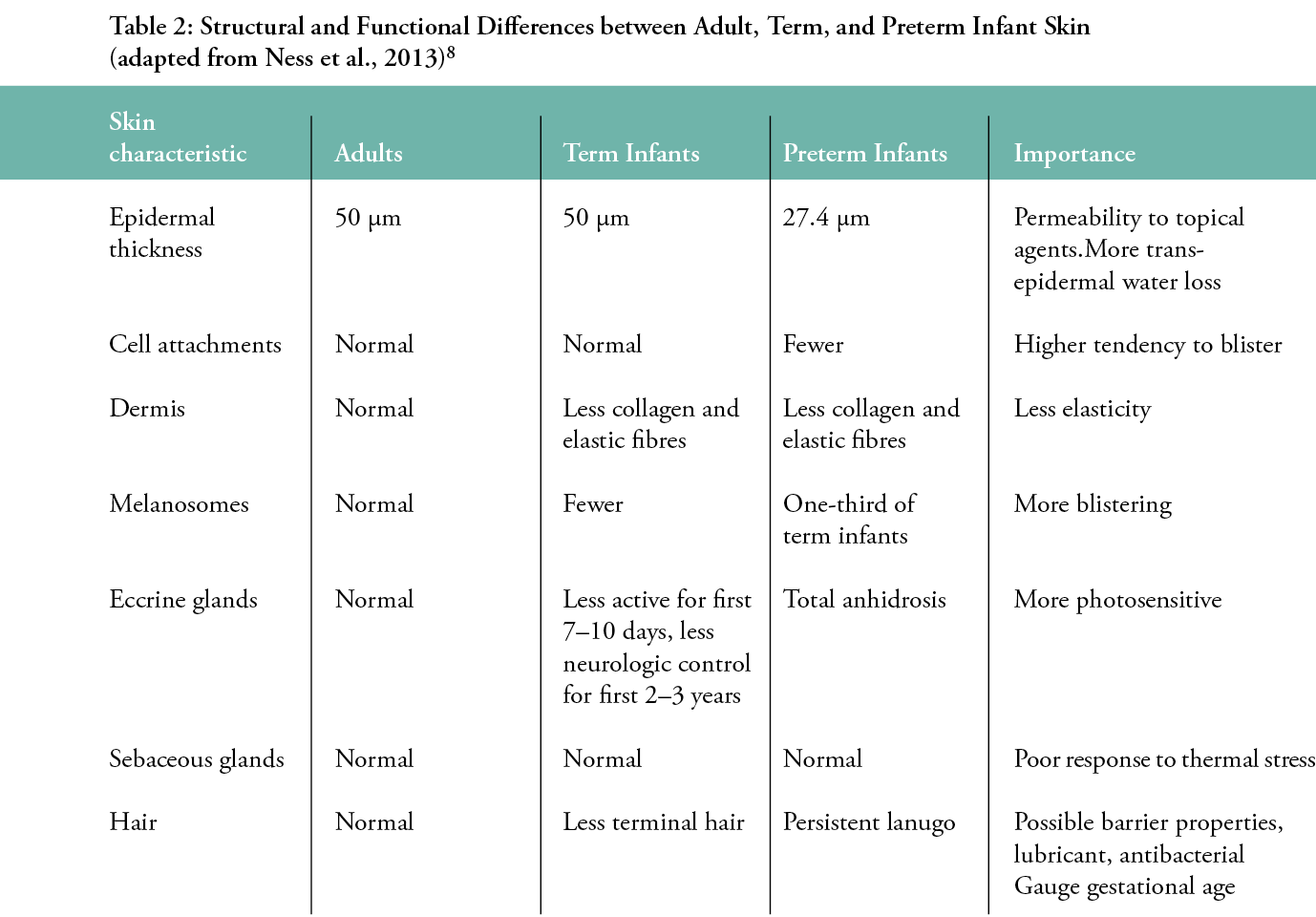

Wound care in pre- and full-term neonates may differ from adults, due to their immature skin structure, which makes them more susceptible to infection, the toxicity of topical medications or dressings, blister formation, changes in ambient temperature and trans-epidermal water and electrolyte loss. Percutaneous absorption of common wound care products containing alcohol, chlorhexidine, povidone-iodine and silver sulfadiazine can be harmful to the paediatric population. Frequent removal and reapplication of adhesives can result in full thickness skin tears and hypopigmentation, hence alternatives such as hydrocolloid dressings are often used to secure monitoring devices instead. The wound-healing process in children is faster than in adults, but often compromised by hemodynamic instability, wound infection, oedema and malnutrition. The recommended cleansing solution is a 1:1 dilution of normal saline with sterile water. Dressings should be protective, atraumatic to apply and remove and adherent in a humidified environment. The most commonly used dressings are transparent polyurethane films, foam dressings, soft silicone dressings, liquid barrier films, hydrogels and hydrocolloid dressings.8

METHODS

A 1-week-old child required an umbilical vein catheterisation, which was complicated by internal iliac artery thrombosis. A necrotic ulcer quickly developed and enlarged over the gluteal area in one week. Despite applying the standard of care and surgical debridement of the necrotic tissue with moist dressing, the wound condition worsened with the development of a new necrotic patch. After the second surgical debridement, TOT in the form of a haemoglobin spray was administered every other day with a moist dressing based on the modern M.O.I.S.T. approach. This topical haemoglobin spray is a liquid spray containing 10% purified haemoglobin applied as a thin layer over the wound bed and covered by a non-occlusive dressing. The effect can last up to 24 hours, with a minimum twice-weekly application. The haemoglobin acts as a carrier for oxygen in a solution, to bring oxygen and promote wound healing. When applied to the wound bed, this facilitates the diffusion of oxygen into the cells.9 A previous randomised control trial demonstrated a significant reduction in average venous leg wound size by 53% after 13 weeks of treatment. There is also evidence of its effectiveness in treating arterial and pressure ulcers, burns5 and delayed closure due to surgical site infection.3

RESULTS / FINDINGS

After the first wound debridement, another dry sloughy patch developed. No granulation tissue was seen. Subsequently, a second debridement was done to remove the unhealthy tissue. A moist dressing with topical haemoglobin spray was then applied with alternate-day dressing changes. Granulation tissue started forming after 2 weeks. The wound healed progressively with epithelisation after 6 weeks.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

Chronic, non-healing wounds carry huge implications in terms of morbidity and mortality, not to mention the significant healthcare resources involved. TOT has proven to be an easily accessible, efficacious, safe, non-invasive and cost-effective method for treating ischaemic wounds in a neonate.9 It also allows the patient to remain mobile while on treatment 24 hours per day.10 The main limitation of TOT’s efficacy is the effective penetration of oxygen into the cells, which requires a specialised delivery device, as illustrated in Table 3.3.

The general strategies used in paediatric wound management are fundamentally similar to those applicable to adults, based on identifying the wound’s aetiology, risk factors and managing moisture and treating infection. However, despite advancements in wound care, evidence-based practices in paediatric wound management still lag behind to their adult counterparts.11 Clinical decision-making for paediatric wounds is based on a combination of provider experience and references from a small number of published clinical practice guidelines.12 This rare case of ulceration over the gluteal region was managed according to the availability of local resources. TOT in the form of haemoglobin spray is a non-traumatic, non-invasive and an accessible therapy option for neonatal wound management.

CONCLUSIONS

Ischemic wounds often respond poorly to conventional wound care practices. HBOT is indicated in certain cases, but it is often limited by accessibility, cost and adverse effects. TOT is a promising alternative, but knowledge of its pathophysiology, efficacy and application are still in the infancy stage.

By contrast, wound management in neonates is extremely challenging, due to their relatively small physical size and preferences for less invasive management strategies. There is also an urgent need for more research and auditing in paediatric wound care, to allow evidence-based practices and the revamping of clinical guidelines specific to the paediatric population.

Key messages

This case study describes the successful treatment of an ischemic ulceration in a neonate using topical oxygen therapy, a non-invasive and easily available approach in resource-limited settings.

Author(s)

Chin Yen Lee1, Yun Ying Ho2, Mohanaprakash Arasappan3, Yeang Wee Koay3, Jacob Abraham1

1 Wound Care Unit, Department of Orthopaedics, Hospital Tengku Ampuan Afzan, Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia

2 Department of Internal Medicine, Hospital Tengku Ampuan Afzan, Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia

3 Department of Paediatric Surgery, Hospital Tengku Ampuan Afzan, Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia

Correspondence: drmaramihai@gmail.com

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- Feldmeier JJ, Hopf HW, Warriner III RA, Fife CE, Gesell LB, Bennett, MH. UHMS position statement: Topical oxygen for chronic wounds. Undersea Hyperb Med 2005; 32(3):157–68.

- Gottrup F, Dissemond J, Baines C, Frykberg R, Jensen PØ, Kot J, et al. Use of oxygen therapies in wound healing: Focus on topical and hyperbaric oxygen treatment. J Wound Care 2017; 26(5):1-43.

- Braun B, Deutschland L. Topical oxygen wound therapies for chronic wounds: A review. 2015. Topical oxygen wound therapies for chronic wounds: a review J. Dissemond, K. Kröger, M. Storck, A. Risse, and P. Engels Journal of Wound Care 2015 24:2, 53-63

- Sayadi LR, Banyard DA, Ziegler ME, Obagi Z, Prussak J, Klopfer MJ, et al. Topical oxygen therapy & micro/nanobubbles: A new modality for tissue oxygen delivery. Int Wound J 2018; 15(3):363–74.

- Davis SC, Cazzaniga AL, Ricotti C, Zalesky P, Hsu L-C, Creech J, et al. Topical oxygen emulsion: A novel wound therapy. Arch Dermatol 2007; 143(10):1252–6.

- Gordillo GM, Roy S, Khanna S, Schlanger R, Khandelwal S, Phillips G, et al. Topical oxygen therapy induces vascular endothelial growth factor expression and improves closure of clinically presented chronic wounds. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2008; 35(8):957–64.

- Dissemond J, Assenheimer B, Engels P, Gerber V, Kröger K, Kurz P, et al. M.O.I.S.T. – A concept for the topical treatment of chronic wounds. JDDG - J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2017; 15(4):443–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.13215

- Ness MJ, Davis DMR, Carey WA. Neonatal skin care: A concise review. Int J Dermatol2013; 52(1):14–22.

- Kröger K, Gäbel G, Juntermanns B. Assessment of acceptability and ease of use of haemoglobin spray (Granulox®) in the management of chronic wounds. Chronic Wound Care Manage Res 2020; 7:1–10.

- Kaufman H, Gurevich M, Tamir E, Keren E, Alexander L, Hayes P. Topical oxygen therapy stimulates healing in difficult, chronic wounds: A tertiary centre experience. J Wound Care 2018; 27(7):426–33.

- Baharestani MM. An overview of neonatal and pediatric wound care knowledge and considerations. Ostomy Wound Manag 2007; 53(6):34–6.

- King A, Stellar JJ, Blevins A, Shah KN. Dressings and products in pediatric wound care. Adv Wound Care 2014; 3(4):324–34.