Volume 23 Number 2

Measures that patients living in the community can take for the prevention and treatment of skin tears: A comprehensive review of the literature

Julie Deprez, Anika Fourie, Dimitri Beeckman

Keywords systematic review, prevention, skin tears, management, Community setting

DOI 10.35279/jowm2022.23.02.04

Abstract

Background Skin tears are acute injuries caused by the separation of the skin layers due to shear forces, friction or blunt trauma and are quite common. A crucial role in reducing the occurrence of skin tears and their severity lies in the promotion of skin health and the prevention of skin lesions, especially in individuals with sensitive skin.

Aim To find measures for the prevention and treatment of skin tears that patients can take in the community.

Review methods Four electronic databases were searched: PubMed, Embase, CINAHL (EBSCO interface) and Web of Science. The search string combined index terms and words related to skin tears, prevention and management. Studies reporting on the prevention and management of skin tears in adults were included. Articles published before 2011 were excluded. The quality of articles was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2019) for systematic reviews, the SIGN methodology checklist for randomised controlled trials and the AGREE II tool for consensus documents and best practice standards. Eight studies were included.

Results Articles reviewed provided numerous prevention and treatment measures: emollient therapy, bathing regimen, protective clothing, nutrition and hydration, polypharmacy, mobility and education.

Conclusion We found a limited body of knowledge, with studies contributing to best practices, prevention and management strategies and the prevalence of skin tears in older, community-dwelling adults.

Implications for clinical practice Elderly people living at home, especially those at high risk for skin tears, should be encouraged to participate in the prevention and treatment of skin tears.

INTRODUCTION

It is reported that skin tears are a common occurrence in the elderly,1,2 as a result of the changes that occur during the ageing process. In a rapidly ageing society, it will be important to consider the severity of these wounds, in order to meet the needs of the growing number of elderly people.3

Skin tears are acute injuries caused by the separation of the skin layers due to shear forces, friction or blunt trauma and are quite common.4,5 However, when left untreated, they can lead to complications and evolve into chronic wounds.6,7 Patients suffering from skin tears may experience pain, increased stress levels in both themselves and their relatives and the tears may lead to infections, or even the need for surgical mitigation.5 These wounds have been described using different terms, with ‘STs’ and ‘lacerations’ being the most common terms in the literature.8 The International Skin Tear Advisory Panel (ISTAP) advocates calling these injuries ‘skin tears’ and defines them as follows: ‘A traumatic wound caused by mechanical forces, including removal of adhesives. Severity may vary by depth (not extending through the subcutaneous layer)’.4,9

Skin tears are most commonly observed in older adults, among critically and chronically ill patients and in infants and children.6 Although skin tears can occur at any anatomic site, they are commonly sustained on the extremities, including the upper hand, lower limbs and on the dorsal aspect of the hands.10 Studies have shown that skin tears are very common wounds and occur in a variety of clinical situations.9 However, anecdotal evidence suggests that many skin tears in community settings go unreported.11 All studies reviewed in this study were conducted in Western Australia, and the prevalence of skin tears they reported on ranged from 5.5% to 19.5%. The lowest percentage of prevalence (5.5%) was found in a study of patients with wounds cared for at home.12 The second-highest prevalence rate was found in patients of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs who received in-home wound care; in that study, the authors found a significantly higher prevalence (19.5%).13 Because they are often considered minor or insignificant wounds, there is little interest in skin tears, which leads to underdiagnosis and a lack of understanding of their causes. This, in turn, contributes to more pain and suffering, longer healing times and higher treatment costs.14

A crucial element of reducing the occurrence of skin tears and their severity lies in the promotion of skin health and the prevention of skin lesions, especially in individuals with sensitive skin.15 Experts agree that the focus should be on prevention, before the treatment of skin breakdown or ‘skin cracking’ is necessary. Therefore, it is important that people who are at risk of developing skin tears be identified early.9,16 Patients and their families should be involved in developing and implementing prevention strategies, and nurses and caregivers should be trained on how to provide care without causing skin tears.7,11 It is important to encourage patients and their families to participate in the care process and to provide them with the education necessary to prevent skin tears.10,17 Considerations for the prevention and treatment of skin tears can be found in books, articles and the proceedings of consensus meetings.18 A more practical dissemination of information aimed at patients concerning the prevention and treatment of skin tears is also needed.

Aim

This literature review aimed to answer the following research question: ‘What actions can patients in the community take to prevent and treat skin tears?’

METHODS

Design

A systematic review was performed to synthesise measures of prevention and management of skin tears in patients living in the community.

Search method

The following electronic databases were systematically searched in November 2021: PubMed, Embase, CINAHL (EBSCO interface) and Web of Science. There were no time or language constraints imposed. The search strategy included search terms for the concepts ‘skin tears’, ‘prevention’ and ‘management’, and indexing terms. The Boolean operator ‘OR’ was used to combine search terms for the same concept. The Boolean operator ‘AND’ was used to combine the concepts. The International Skin Tear Advisory Panel (ISTAP) website (http://www.skintears.org/) was then searched to find clinical practice guidelines and best practice standards for the prevention and treatment of skin tears. Retrieved records were imported into EndNote v.20 reference management software (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA). Duplicates were removed using the duplicate search function and by manually going through the list.

Study selection

The reviewer screened the articles based on their titles and abstracts. The full texts of the remaining articles were reviewed individually by the reviewer for eligibility. If the full text of an article was not available in English or Dutch, it was excluded. Additional relevant studies were identified by citing and quoting references from the included studies. Studies that reported on the prevention and treatment of skin tears in adults, regardless of geography, medical setting, ethnicity or racial background were included. To cover a broad range of strategies for the prevention and treatment of skin tears, the following types of articles were included: (1) (systematic) reviews; (2) clinical practice guidelines, consensus documents and best practice standards; (3) intervention studies; and (4) case studies. Editorials and commentaries were excluded. To ensure that the included prevention and treatment strategies applied to current health care settings, articles published before 2011 were excluded.

Data extraction

The included articles were methodologically divided among (1) clinical practice guidelines, consensus documents and best practice standards; (2) intervention studies; and (3) reviews. The reviewer extracted the data (using data extraction tables). Data extraction included: (1) for clinical practice guidelines, consensus documents and best practice standards and reviews: source, topic and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of skin tears; and (2) for intervention studies: authors, year of publication, topic/research question, sample, interventions and main results. No meta-analysis was possible because of the expected heterogeneity in the identified studies’ design, interventions and outcome measures. A narrative approach was used to summarise the findings.

Quality assessment

The included articles were assessed for methodical quality by the reviewer using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (2019) for systematic reviews, the SIGN methodology checklist for randomised controlled trials and the AGREE II tool for consensus documents and best practice standards. The purpose of this review was to highlight a wide range of strategies for the prevention and treatment of skin tears. For this reason, the included studies were not exempted from the quality assessment.

RESULTS

A total of 165 records were found via the systematic

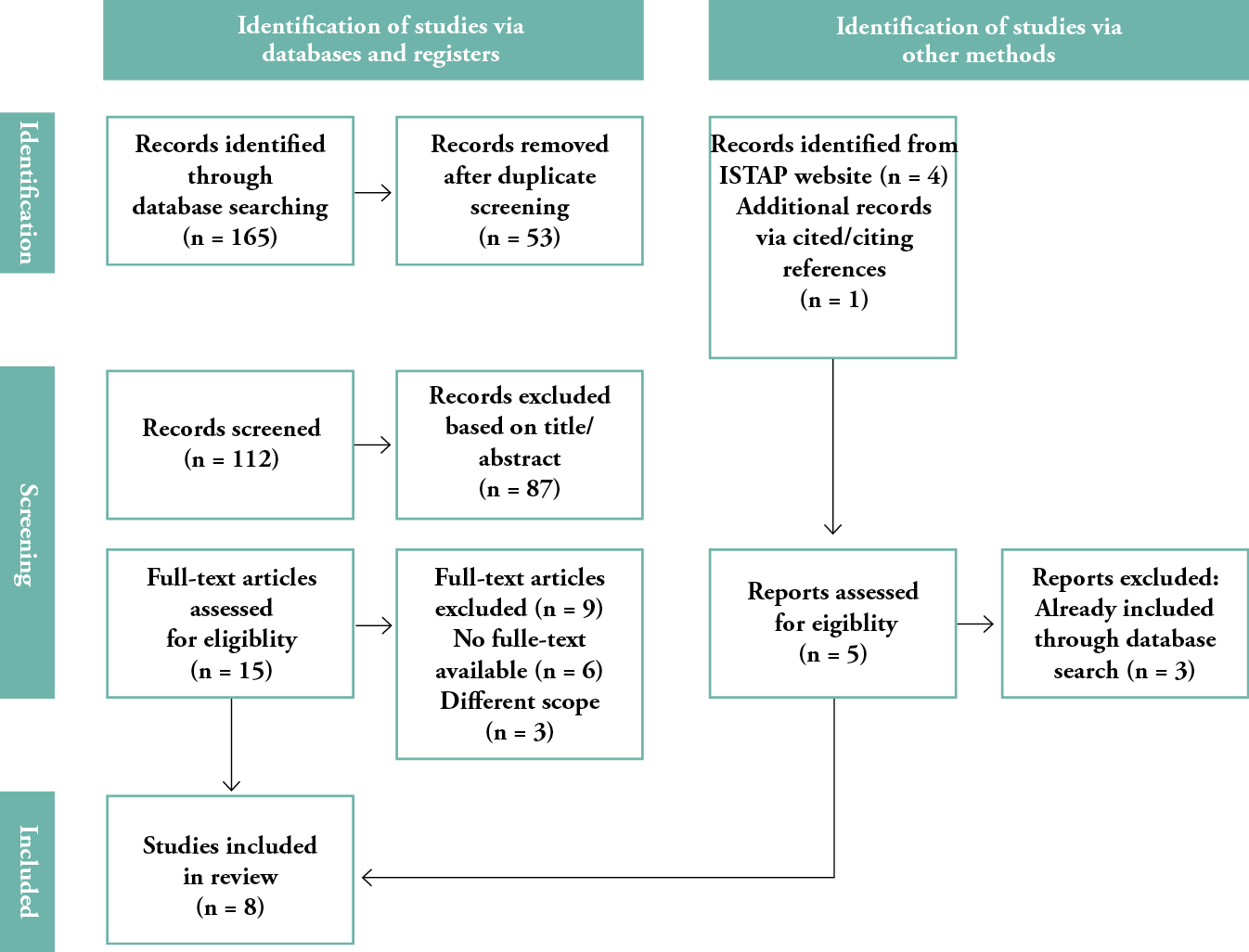

database search (24 from PubMed, 34 from Embase, 75 from CINAHL (EBSCO interface) and 32 from Web of Science). Four records were identified by searching the ISTAP website, and one additional record was identified via cited references. In total, 112 records were screened by title and abstract, of which 97 were excluded; 28 were published before 2011, and 69 did not address the prevention and treatment of skin tears in adults. After title and abstract screening, 15 records were identified as eligible for full text screening. Of these, nine were excluded; three did not address the prevention and treatment of skin tears in adults, and the full text was not available for six articles. After removing duplicates, screening records and conducting additional searches, eight studies were included in the review. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA19 flow diagram summarising the review process. Included in the study were: clinical practice guidelines, consensus documents and best practice standards (n = 3), clustered randomised controlled trials (n = 1), pre-post study (n = 1) and reviews (n = 3).

Figure 1: The PRISMA19 flow diagram summarising the review process

PREVENTATIVE MEASURES

When examining, planning and implementing care for skin tears, prevention should be the goal whenever possible. The idea is that skin health can be maintained, and damage averted, by addressing modifiable risk factors.9

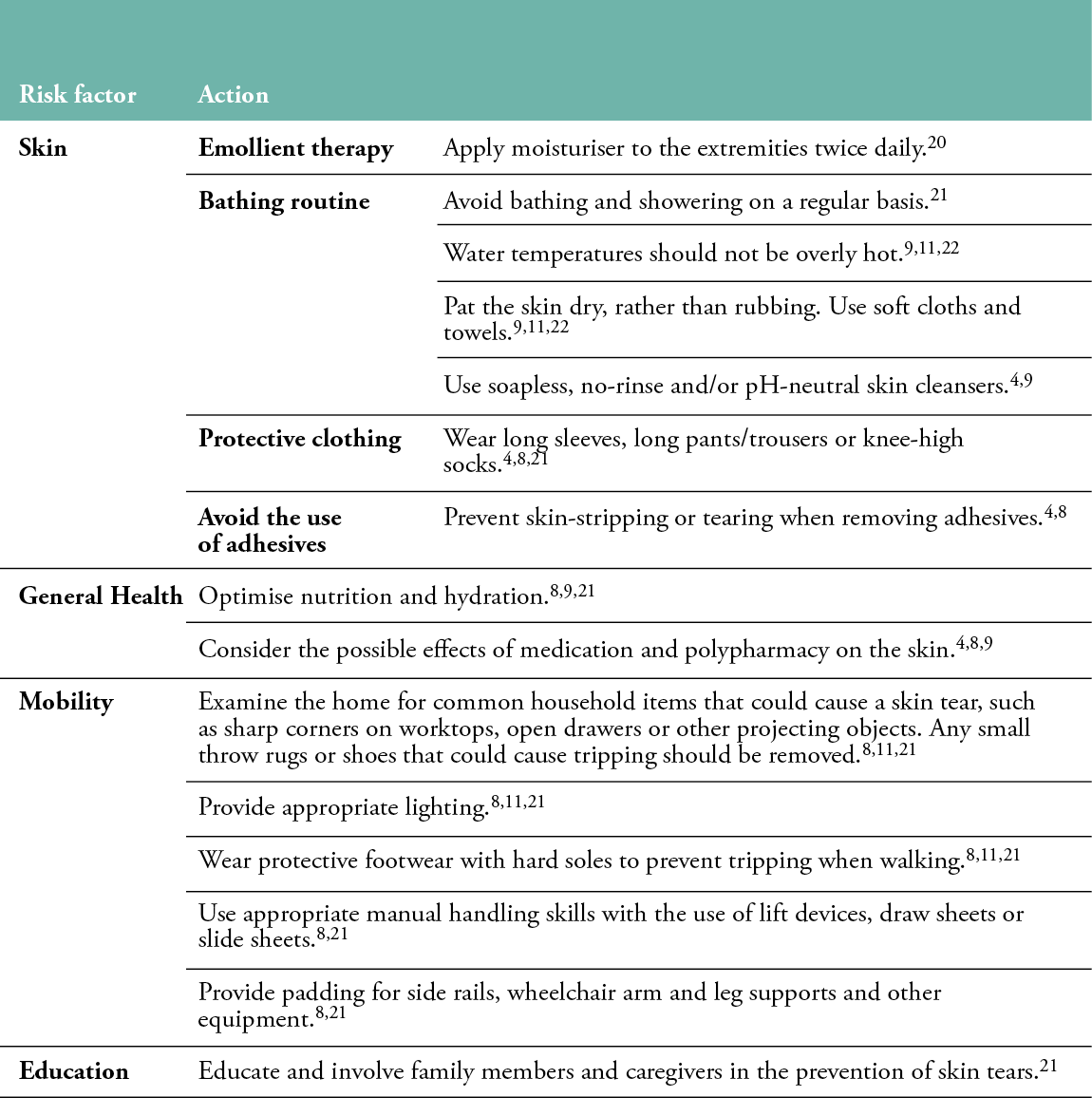

Skin

The body’s natural aging process affects the skin. It becomes more fragile, and therefore more susceptible to damage, such as skin tears. Keeping the skin in the best possible condition is one of the most important elements of prevention.8,9 For people with aged skin, emollient therapy should be considered an essential aspect of their skincare regimen.9 According to a study by Carville, Leslie, Osseiran-Moisson, Newall and Lewin 20, twice-daily application of moisturiser to the extremities of elderly care facility residents (n = 420 in the intervention group; n = 564 in the control group) reduced the incidence of skin tear occurrence by more than 50%, compared with ‘usual’ skin care methods in 14 aged care facilities in Western Australia. The average monthly incidence rate in the intervention group was 5.76 per 1,000 occupied bed days (450 skin tears in six months), compared with 10.57 per 1,000 occupied bed days (946 skin tears in six months) in the control group (P = 0.004).20

The patient’s bathing routine should also be observed. Regular bathing and showering should be avoided. As the skin becomes more susceptible to dryness, the risk of skin tears increases in the elderly, since the skin’s the natural hydration decreases due to decreased activity of the sebaceous and sweat glands. Bathing dries out the skin by removing the body’s natural oils from the surface.21 In addition to considering the frequency of bathing, the temperature of the water is also important. The water should not be too hot, and the skin should be patted dry, rather than rubbed. The use of soft cloths and towels that are not too hard on the skin are advised.9,11,22 Soap-free, non-rinse and/or pH-neutral skin cleansers are recommended.4,8

For additional skin protection, those at risk for skin tears may wear protective clothing, such as long sleeves, long pants/trousers or knee-high socks. Clothing that is too tight or restrictive of movement should be avoided.4,8,21 The use of adhesives on sensitive skin should also be avoided; non-traumatic paper/silicone tapes, non-adherent contact layers, non-adherent silicone foam dressings or other topical dressings specifically designed to care for sensitive skin are indicated, when dressings or tapes are required. This can prevent the skin from being pulled or torn when the product is removed.4,8 If tape must be used on the skin, it should be kept to a minimum. To facilitate removal of the tape, a tape remover can be used by applying counterpressure to the skin in the opposite direction while slowly unrolling the tape.21 Scratching or accidental pinching by long fingernails of the caregivers, family members or older adults themselves can also cause skin injuries. To decide whether fingernails and toenails need to be trimmed or filed, their length can be measured.4,8,11,21

General health

Nutrition and hydration

To improve skin health, support the healing of a current skin tear and prevent future skin tears, it is important to ensure adequate nutrition and hydration. Malnutrition can cause damaged tissue to heal more slowly, and it increases the risk of infection. Both obese and malnourished patients are susceptible to changes in tissue/body structure and function. Nutritionists can advise on the amounts and types of foods, such as dairy, meat, beans/legumes, nuts, eggs and soy products that are helpful for wound healing. Overall, it is recommended that older people eat four to six small meals per day and consider taking a daily multivitamin, after consulting with their physician.8,9,21

Polypharmacy

Polypharmacy (taking numerous medications that can lead to drug interactions, reactions or confusion) is common in the elderly. A wide range of medications can affect the skin, and corticosteroids are the most common among these, as steroids can play a role in skin cracking. Polypharmacy has also been associated with an increased risk of falls. Falls are highlighted in the consensus document by LeBlanc and Baranoski4 as another important risk factor for the development of skin tears.4,8,9

Cognitive impairment

Due to a lack of patient understanding, cognitive impairment can result in less adherence to preventative measures. Aggressive behavior and agitation associated with impaired cognition and dementia can also increase the risk of skin injury from blunt trauma and self-injury. In the elderly population, a lack of cognition or insight may increase the risk of skin tears. In this case, the primary focus should be on educating the patient’s family or caregivers.8,9,22

Mobility

Skin tears in the elderly are often caused by environmental factors. Those at risk for skin tears should identify any mobility-related problems associated with skin tears by working with their caregivers and the medical community and then take a coordinated approach to reduce these risks.8

The home can be examined for common household items that could cause a skin tear, such as sharp corners on countertops, open drawers or other protruding objects. Unnecessary bumps or knocks to the skin from solid objects can be minimised by proper lighting. Tables and stools with overhanging legs that older people can accidentally bump into as they move around the house should be avoided. Small rugs or shoes that could be tripped over should also be removed. Protective shoes with hard soles can be worn to avoid tripping hazards while walking.8,11,21

Skin tears often occur during everyday activities such as dressing, bathing and repositioning. Skin tears occur more often in people who are totally dependent on others for their care; for this reason, patients (and their families) should be aware of the importance of proper positioning, turning, lifting and transferring. Shear or friction injuries can be prevented or reduced by using appropriate aids such as hoists, pull sheets or slide sheets, during manual handling. Padding for side rails, arm and leg supports for wheelchairs and other assistive devices, can also be provided.8,21

Education

It is important to initiate and involve family members and caregivers in the prevention of skin tears.21 An evidence-based approach to educating patients and community workers was implemented in a three-phase study conducted in South Queensland, Australia.23 Eight care providers and 20 community care patients previously identified as at risk for skin tears, based on previous wound care pathways and episodes of skin tears, were included. First, evidence-based criteria were used to establish a baseline audit; these results were reflected upon in the second phase, and solutions to address the violations discovered in the baseline audit were developed and implemented. In the third phase, a follow-up audit was conducted to review the results of the actions implemented to improve practices and to identify future practice issues to be addressed in future audits. Compliance with each criterion improved, with some of the increases being quite significant. The criterion involving informing family members or caregivers about the prevention of future skin tears was rated as worsening. The difficulty of caregivers being present in the patient’s home during the scheduled caregiver visits was another barrier of note. The criteria that addressed the requirement for a validated categorization tool (STAR) and teaching patients prevention strategies to minimise future skin tears showed the best improvement. After implementation of the project, it appeared that patient and nurse education efforts were very useful in this regard.23

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Although the prevention of skin tears should remain the primary goal, if a skin tear does occur, use evidence-based practices for wound care.21

Control bleeding

To stop the bleeding, apply pressure and, if necessary, elevate the limb. If stopping the bleeding is the primary goal, a dressing can be used.8,11,22

Cleanse and debride

To prepare a wound for dressing, clean it to remove surface bacteria and necrotic material. To minimise further damage, the surrounding skin should be gently patted dry. The skin flap should be re-approximated, if it is suitable for use as a ‘dressing.’ Use a gloved finger, a moistened cotton ball, tweezers or a silicone strip to gently push the skin flap back into place.8,9,11,21

Monitor wound edges

Skin tears take an average of 14–21 days to heal, depending on the size and depth of the tear. If this is not the case, the wound should be re-examined to ensure that all known causes delaying healing have been addressed.8,22

Dressings

Dressings should be used to cover, protect and help the skin tear heal. There are numerous alternatives for dressings. The items available to the nurse, his or her clinical experience and the degree of skin damage caused by the skin tear should all be considered in the decision. Dressings for skin tears should absorb exudate (drainage), keep the wound moist, be painless to remove and remain in place for several, but no longer than seven, days.9,21

Table 1: Preventative measures

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to answer the research question: ‘What actions can patients in the community take to prevent and treat skin tears?’ Eight articles were included in this review. One limitation of this review is that the literature search, record selection and quality assessment were performed by only one researcher. Another disadvantage is the possibility of publication bias. Despite the inclusion of multiple databases, it is likely that some studies were overlooked. In addition, studies published in languages other than English or Dutch were excluded from the review, which may have influenced the results. Only a limited body of knowledge was found that included studies contributing to best practices, prevention and management strategies and the prevalence of skin tears aimed at older adults living at home. Randomised controlled trials were lacking; however, a number of guidelines and consensus statements on the prevention and management of skin tears have been published and can be used to guide patients in the home setting. All studies were based on assessments conducted by healthcare providers; however, in the community, it is usually caregivers, families and patients who prevent skin tears and provide their initial assessment and treatment. Therefore, the results of this review should be interpreted with caution.

Studies have shown that skin tears are very common wounds and occur in a variety of clinical settings.9 The reported incidence rate of skin tears in the community was based on those that occurred during the direct planned care period. Most skin tears treated in home care occur outside of staff visiting hours, so their prevalence cannot be accurately measured. In home care, the prevention of skin tears may be more important than treatment in most cases.23

It is usually a nurse who makes an informed decision about which dressing product is most appropriate for a skin tear, taking into account the client’s other medical conditions. In the community, however, it is often not a registered nurse who recognises and addresses a skin tear. This could be because many patients in the community do not use health-related services, and therefore do not receive regular visits from nurses. Non-healthcare workers visit the elderly at home and may not be able to identify skin tears, or the problem may not be discussed with staff and therefore go unnoticed. If simple wounds are left untreated or are treated improperly, they can fester or become infected, leading to long hospital stays, depending on the severity of the wound.23 Patients and caregivers should be encouraged to participate in the prevention and treatment of skin tears whenever possible. Patients and their families can be educated to be aware of their own surroundings and to recognise potential risks, such as loose rugs or inadequate lighting, as education is a key component in any successful prevention or treatment programme.24 They can be taught the importance of wearing protective clothing and made aware of the importance of proper positioning, turning, lifting and transferring.25 Patients can also incorporate emollient therapy into their daily routine by applying moisturiser twice daily. Patients who are educated about skin tears can assess their own risk and monitor their own skin. When a skin tear occurs, patients can provide first aid by stopping the bleeding, cleaning the wound, dabbing the wound dry instead of rubbing it and avoiding the use of adhesives.

To ensure that the prevention strategies mentioned in this article are successful in preventing and/or reducing skin tears, patient involvement is required.7 Therefore, patients should be encouraged to participate in their care and provided with the necessary education to prevent skin cracking.10,17 Because caregivers, family members and patients are the first to notice a skin tear, it is important that they have access to best-practice education and tools. When treating a skin tear, determining the viability of the skin flap, selecting dressing products and techniques for dressing skin tears are also important considerations.23

CONCLUSION

When possible, elderly people living at home, especially those at high risk for skin tears, should be encouraged to participate in the prevention and treatment of skin tears. Patients and their families can be taught how to be aware of their surroundings and recognise potential risks. Patients can incorporate emollient therapy into their routine by applying moisturiser twice daily. Patients who are educated about skin tears can assess their own risk and monitor their own skin. The patient can provide first aid if a skin tear occurs. To do this, they must be involved in their care and given the necessary instructions to prevent skin tears.10,17 Because personal care workers, family members, and patients are the first to detect a skin tear, having access to best-practice education and resources is crucial.23 As education is a key component in any successful prevention or treatment programme,24 patients’ awareness of skin tears must be assessed in the future in order to identify educational needs and priorities among patients. Based on these educational needs, educational programmes for patients and their caregivers to prevent and treat skin tears can be developed and implemented. The effect of patient and caregiver education on the prevalence of skin tears in the general population would then need further research.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

Elderly people living at home, especially those at high risk for skin tears, should be encouraged to participate in the prevention and treatment of skin tears.

Further research

Whether or not patients lack the knowledge about skin tears to adequately participate in their care has not been confirmed or investigated in the literature. Therefore, future research is needed to assess patients’ knowledge of skin tears to determine their education needs and priorities. Based on these educational needs, programmes can be developed and implemented to train patients and their caregivers about the prevention and treatment of skin tears. Further research is also needed to determine the impact of patient and caregiver education on the prevalence of skin tears in the population.

Key messages

Skin tears are acute injuries caused by the separation of the skin layers due to shear forces, friction or blunt trauma and are quite common. A crucial role in reducing the occurrence of skin tears and their severity lies in the promotion of skin health and the prevention of skin lesions, especially in individuals with sensitive skin. This literature review aims to answer the following research question: ‘What actions can patients in the community take to prevent and treat skin tears?’ Articles reviewed provided numerous prevention and treatment measures, such as emollient therapy, bathing regimen, protective clothing, nutrition and hydration, polypharmacy, mobility and education.

Author(s)

Julie Deprez (RN, MSc)1, Anika Fourie (RN, IIWCC, MSc, PhD candidate)1, Dimitri Beeckman (RN, BSc, MSc, PGDip(Ed), PhD, FEANS)1-4

1 Skin Integrity Research Group (SKINT), University Centre for Nursing and Midwifery, Department of Public Health and Primary

Care, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

2 Swedish Centre for Skin and Wound Research (SCENTR), School of Health Sciences, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden

3 Research Unit of Plastic Surgery, Department of Clinical Research, Faculty of Health Sciences, Odense, Denmark

4 School of Nursing & Midwifery, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI), Dublin, Ireland

Correspondence: julie.deprez.0412@icloud.com

Conflict of interest: None

References

- O’Regan A. Skin tears: a review of the literature. World Counc Enteros Ther J. 2002;22(2):26-31.

- Carville K, Lewin G, Newall N, Haslehurst P, Michael R, Santamaria N, et al. STAR: a consensus for skin tear classification. Primary Intention: The Australian Journal of Wound Management. 2007;15(1):18-28.

- Koyano Y, Nakagami G, Iizaka S, Minematsu T, Noguchi H, Tamai N, et al. Exploring the prevalence of skin tears and skin properties related to skin tears in elderly patients at a long‐term medical facility in Japan. International wound journal. 2016;13(2):189-197.

- LeBlanc K, Baranoski S. Skin tears: state of the science: consensus statements for the prevention, prediction, assessment, and treatment of skin tears©. Advances in skin & wound care. 2011;24(9):2-15.

- Lopez V, Dunk AM, Cubit K, Parke J, Larkin D, Trudinger M, et al. Skin tear prevention and management among patients in the acute aged care and rehabilitation units in the Australian Capital Territory: a best practice implementation project. International Journal of Evidence‐Based Healthcare. 2011;9(4):429-434.

- LeBlanc K, Baranoski S, Holloway S, Langemo D, Regan M. A descriptive cross‐sectional international study to explore current practices in the assessment, prevention and treatment of skin tears. International wound journal. 2014;11(4):424-430.

- Campbell KE, Baronoski S, Gloeckner M, Holloway S, Idensohn P, Langemo D, et al. Skin tears: prediction, prevention, assessment and management. Nurse Prescribing. 2018;16(12):600-607.

- LeBlanc K, Baranoski S, Christensen D, Langemo D, Sammon MA, Edwards K, et al. International Skin Tear Advisory Panel: A Tool Kit to Aid in the Prevention, Assessment, and Treatment of Skin Tears Using a Simplified Classification System: ©. Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 2013;26(10):459-476. doi:10.1097/01.Asw.0000434056.04071.68

- LeBlanc K, Campbell K, Beeckman D, Dunk A, Harley C, Hevia H, et al. Best practice recommendations for the prevention and management of skin tears in aged skin. Wounds International. 2018; Retrieved from: https://woundsinternational.com

- Stephen-Haynes J, Carville K. Skin tears made easy. Wounds International. 2011;2(4):1-6.

- Benbow M. Assessment, prevention and management of skin tears. Nurs Older People. 2017;29(4):31-39.

- Carville K, Lewin G. Caring in the community: a wound prevalence survey. Primary Intention. 1998;6(2):54-62.

- Carville K, Smith J. A report on the effectiveness of comprehensive wound assessment and documentation in the community. Primary Intention: The Australian Journal of Wound Management. 2004;12(1):41-49.

- Strazzieri-Pulido KC, Peres GRP, Campanili TCGF, Santos VLCdG. Skin tear prevalence and associated factors: a systematic review. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP. 2015;49:0674-0680.

- Beeckman D, Campbell J, LeBlanc K, Harley C, Holloway S, Langemo D, et al. Best practice recommendations for holistic strategies to promote and maintain skin integrity. Wounds International. 2020; Retrieved from: https://woundsinternational.com

- LeBlanc K, Baranoski S. Skin tears: finally recognized. Advances in skin & wound care. 2017;30(2):62-63.

- LeBlanc K, Langemo D, Woo K, Campos HMH, Santos V, Holloway S. Skin tears: prevention and management. British journal of community nursing. 2019;24(Sup9):S12-S18.

- da Silva Torres F, Blanes L, Ferreira M. Development of a Manual for the Prevention and Treatment of Skin Tears. Wounds: a Compendium of Clinical Research and Practice. 2018;31(1):26-32.

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews. 2015;4(1):1-9.

- Carville K, Leslie G, Osseiran‐Moisson R, Newall N, Lewin G. The effectiveness of a twice‐daily skin‐moisturising regimen for reducing the incidence of skin tears. International wound journal. 2014;11(4):446-453.

- Holmes RF, Davidson MW, Thompson BJ, Kelechi TJ. Skin tears: care and management of the older adult at home. Home Healthc Nurse. Feb 2013;31(2):90-101; quiz 102-3. doi:10.1097/NHH.0b013e31827f458a

- Idensohn P, Beeckman D, Campbell KE, Gloeckner M, LeBlanc K, Langemo D, et al. Skin tears: a case-based and practical overview of prevention, assessment and management. Journal of Community Nursing. 2019;33(2):32-41.

- Beechey R, Priest L, Peters M, Moloney C. An evidence-based approach to the prevention and initial management of skin tears within the aged community setting: A best practice implementation project. Review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 2015;13(5):421-443. doi:10.11124/jbisrir-2015-2073

- Ratliff CR, Fletcher KR. Evidence to Support and Treatment. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2007;53(3):32-42.

- Baranoski S. How to prevent and manage skin tears. Advances in skin & wound care. 2003;16(5):268-270.