Volume 23 Number 3

Implementing seating guidelines into clinical practice and policy: A critical reflection and novel theory

Ray Samuriwo, Melanie Stephens, Carol Bartley, Nikki Stubbs

Keywords guidelines, pressure ulcers, implementation, liminal spaces, seating, trajectory

DOI 10.35279/jowm2022.23.03.05

Abstract

Introduction A significant proportion of healthcare that is delivered is wasteful, harmful and not evidence-based. There are many wound care-related guidelines, but their implementation in practice is variable. The Society of Tissue Viability (SoTV) published updated seating guidelines in 2017, but there is a lack of theoretical and conceptual clarity about how these guidelines are being used to inform clinical practice. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to generate a theory that can be used to incorporate the SoTV seating guidelines into policy and clinical practice.

Methods We critically reflected on data from an evaluation study using a systems thinking approach and informed by implementation and safety science using the wider literature and our expertise to generate a guideline-implementation theory.

Discussion Factors that facilitate or hinder the incorporation of the SoTV guidelines into policy and practice were characterised. We conceptualised the implementation of these guidelines into policy and practice into a Translation or Implementation into Policy or Practice (TIPP) theory with distinct stages, which we called ‘liminal spaces’. Knowledge of the guidelines, and the agency or authority to effect change, are key factors in the translation of these guidelines into clinical practice.

Conclusion Our theory is that there are liminal spaces in the implementation trajectory of these guidelines into practice, and these have their own characteristics. This theory provides a framework that can be used to underpin guidelines’ strategies for embedding skin and wound care guidelines into policy and clinical practice to improve patient care.

INTRODUCTION

The Society of Tissue Viability Study (SoTV), formerly known as the Tissue Viability Society (TVS), published the second iteration of its seating guidelines in 2017 to provide advice on how best to prevent pressure ulcers in people who spend a lot of their time seated or are chair-bound (1, 2). A subsequent survey evaluation (3) in 2021 reported that the implementation of these guidelines into clinical practice and policy was limited. Unfortunately, this finding is consistent with wider evidence on guideline implementation in healthcare.

More than one third of healthcare is inconsistent with best practice guidelines and is wasteful or harmful (4, 5). Over the last two decades, there have been concerted and strenuous efforts to improve the quality and safety of patient care through the publication of a wide range of guidelines and initiatives to translate research evidence into practice (4–6). However, the challenges of embedding evidence into practice are somewhat intractable, as only 60% of healthcare is consistent with the guidelines; 10% of care is harmful; and the remaining 30% of care is suboptimal, wasteful or of limited value (4, 5). Guidelines seek to inform key aspects of care organisation, service delivery, policy, practice or governance to ensure the consistent delivery of safe, high-quality, person-centred care that attains the best possible patient outcomes (6–8).

Interventions to maintain skin integrity and promote wound healing are a central tenet of high-quality healthcare that enhances patients’ safety, quality of life and wellbeing (9–12). Consequently, there are many national and international wound care guidelines (10, 13–16), but the translation of these guidelines into policy and practice is variable (16–18). The variations in the translation of healthcare-related guidelines, such as those for wound care, have been attributed to a variety of individual, contextual, organisational and system-related factors (6, 16–19). Similar issues were also reported by participants in a recent survey evaluation (3) as impediments to the implementation of the SoTV guidelines into clinical practice.

Healthcare is delivered in complex, rapidly evolving systems with contingent, emergent and uncertain elements (4, 20–24) that invariably affect the translation of guidelines into practice. Differences in the use of guidelines in clinical practice may be due to the complex systems in which healthcare is delivered (4, 20, 21, 23, 24). These differences may reflect prudent adaptations to meet the needs of a specific patient or client group (6), but they may also be a harbinger for unwarranted variations in the quality of patient care. The SoTV survey evaluation (3) had 39 participants, which limits the extent to which its findings can be applied more widely, but it highlighted some facilitators and barriers to the implementation of these seating guidelines into practice.

The main recommendations from this study were that future SoTV guidelines should incorporate strategies and interventions with clear objectives that can be used to facilitate translation and implementation into practice. The SoTV seating guidelines have been downloaded more than 6,000 times, as of this writing, so there is an urgent need for conceptual clarity about how they can be used effectively to underpin safe, high-quality skin care for patients through policy and clinical practice. In this paper, we critically reflect on the data from this survey using the wider literature to generate a theory that can be used to integrate the SoTV seating guidelines into clinical practice and policy.

METHODS

We undertook a critical reflection of data gathered in the SoTV seating guidelines survey evaluation informed by Driscoll’s reflective model (25) and the wider wound healing, implementation and translation literature. Our reflection also drew upon our experiences as a diverse group of healthcare professionals involved in the evidence synthesis and consultation project that created the SoTV seating guidelines (1, 2) and their subsequent evaluation (3). The first stage in Driscoll’s reflective approach is to state what the issue is, so that it can be understood in its proper context. The next step is to consider the issue in greater detail, with a particular emphasis on what has been learned. In this second stage, we adopted a theoretical framework to enable us to reflect critically on the data from the survey and the wider literature. The use of a theoretical framework to underpin our reflection was apt, as we sought to generate conceptual and theoretical insights that could be used to underpin the subsequent implementation of the SoTV seating guidelines into clinical practice and policy. This approach was also consistent with the Driscollian reflective approach (25), which culminates in clarity about what, if anything, needs to be done differently in the future with regards to the issue at hand.

Theoretical framework

Knowledge translation or implementation into practice can be conceptualised and understood in different ways (21, 26). One view is that the translation of knowledge into policy and practice is a linear process with distinct gaps that need to be overcome to enact change (4, 5, 21). An alternative, nuanced systems thinking view considers knowledge translation to be a recursive, dynamic process that takes place in complex health and social care systems (4, 5, 20, 21, 27, 28). We adopted the latter view (4, 5, 21, 27, 28), in which knowledge translation is best understood through systems thinking informed by pertinent elements of implementation and complexity science. This systems-informed outlook (5, 21, 27) is appropriate, in our view, because it recognises the multifaceted interactions or connections among different agents, individuals and factors during the translation of knowledge into practice. In other words, we used a systems thinking approach to underpin our reflection because it best reflects the nature, and reality, of clinical practice.

Healthcare is delivered in complex adaptive systems throughout the patient trajectory, which results in some aspects of care delivery being uncertain and emergent (20, 29, 30). The elements of healthcare that are emergent and uncertain as a result of the contingencies that arise in practice (30) can be codified, convoluted or linked. Consequently, healthcare delivery is predicated on a combination of formal processes and structures, such as policies, and emergent elements, such as negotiations and adaptation throughout the patient care trajectory. Emergent aspects of healthcare organisation often exist outside of formal management structures and tend to be overlooked in managerial narratives and improvement efforts (20, 30). These are often tacit and sometimes referred to as ‘fugitive knowledge’ or ‘soft intelligence’ because they exist outside of formal knowledge systems and structures (31). There is a growing consensus that healthcare improvement efforts can only be effective when there is due awareness and recognition of the emergent, negotiated and tacit aspects that are inherent in the complexity of clinical practice (20). Therefore, in our reflection, we adopted a systems thinking approach that incorporated relevant aspects of implementation and complexity science.

The issue

The main issue upon which we reflected was the limited implementation of the SoTV seating guidelines, as noted in our survey evaluation study (3). We revisited the primary data provided by the 39 participants in this study to better understand their accounts in relation to the wider guideline implementation literature and theories. The views expressed by our participants fell into two broad categories relating to how these guidelines were being integrated into policy and practice, and the issues that affected their implementation. To give a comprehensive account of the issue as reported by the participants, we present a selection of direct quotes that best typify the sentiments expressed, accompanied by our reflective narrative. In the accompanying text, we give due prominence to minority perspectives and unique narratives in the statements made by participants. Although we set out the issue as we understand it in two subheadings, we acknowledge that many of the elements highlighted in the quotes presented here may interact in different ways with regards to the implementation of the SoTV seating guidelines in local policies and practices.

Implementation into policy and practice

Most survey participants (n=27) indicated that they had either had or intended to incorporate the SoTV seating guidelines into policy (n=11) or practice (n=16) (3). These participants described how they did this in their everyday clinical practice, education and training, and used them as a resource or tool for disseminating best practices. Those who reported using these seating guidelines to inform their clinical practice highlighted the various ways in which their approach to patient care had changed. The seating guidelines were said to have provided the impetus for them to work collaboratively with other healthcare professionals, change their own practices and those of others. The changes to personal practice included changes to assessment for seating, the use of seating equipment and the documentation of care given. Changes to wider practices included the adoption of a more holistic approach to assessment, prescription and the recording of seating:

‘I now involve OT (occupational therapy) with seating assessment of patients.’

‘A patient was admitted, and I was able to conduct an assessment and prescribe an appropriate cushion.’

‘I changed my practice, cascaded (the guidelines), and advise staff (about seating) on a 1:1 basis.’

‘Patients are assessed for the “correct fit” of the chair, and the documentation states which assessments have been made, and which chair has been allocated.’

Many of the participants (n=26) were tissue viability nurses (TVNs) who described how the SoTV seating guidelines had been incorporated into education and training for all healthcare professionals and a wide range of undergraduate students. The seating guidelines were also said to be used as an educational resource to support clinical decision-making by staff and during continuing professional development. The participants also revealed that the SoTV seating guidelines were used during trainings to make staff more aware of the different options available regarding the provision and supply of equipment:

‘I introduced elements (of the guidelines) to our pressure ulcer training programme.’

‘(The guidelines are used in) education for therapy staff and as a resource…available for rolling in service training programme for new staff.’

‘(The guidelines are used) to support advice provided to teams, care homes, to evidence practical demonstrations and to update staff.’

‘(The guidelines are) highlighted to AHP (allied healthcare professions) and nursing undergraduates in universities as a resource.’

A few participants (n=5) reported that they used the SoTV seating guidelines as a resource or tool for disseminating best practices in their clinical setting. These people recalled that the guidelines had been disseminated in different contexts in the form of leaflets and posters about seating in relation to pressure ulcer prevention and management. They reported that the process of disseminating the guidelines fostered the development of productive relationships with other members of the multidisciplinary team, as they had a shared collaborative focus on improving the quality of patient care. Disseminating the guidelines via posters, leaflets and training also contributed to changes in quality assurance processes, such as root cause analyses and audits of best practices in relation to seating:

‘We introduced, promoted and utilise a Trust “Sitting in Hospital” leaflet, which is available in all clinical areas or via intranet for staff to access.’

‘We worked with our Wheelchair Service Team to develop posters & training. The team are now receiving earlier referrals & contributing to Root Cause Analysis, enabling further learning about the complexities of seating.’

‘New guidelines were developed which incorporated the TVS Seating Guidelines. Audits were completed to assess compliance.’

Issues affecting implementation

Several people in the survey (n=14) noted different issues that affected the implementation of the SoTV seating guidelines in their local policies or practices. The factors cited as barriers included a lack of awareness about the guidelines, not having read the guidelines, local or individual factors and a lack of clarity about the responsibility or strategy for implementation. Nine participants revealed that they were not aware of these guidelines, but some of them stated that they intended to read the guidelines and consider how to implement them in clinical practice. Another two participants indicated that they were new in their post, or lacked the resources to incorporate the guidelines into practice:

‘Unfortunately, this is the first time I have been made aware of these guidelines, but I will speak with my team to see how best we can implement and enforce these guidelines through our policies and procedures.’

‘(I am) …very new to the service and trying to understand the literature available to help my practice.’

‘(We)…do not have resources to provide a large variety of chairs for every size of patient.’

Six people mentioned issues relating to a lack of clarity or strategy about the implementation of the SoTV seating guidelines. Most of them (n=4) maintained that the responsibility for implementing these guidelines was outside the scope of their roles and/or responsibilities. However, the other two cited a lack of wider awareness of the guidelines, due to a lack of engagement with the SoTV or a lack of engagement in the policy-making process:

‘I do not make decisions on policies for our service.’

‘Our OTs do all the seating assessments and I’m sure will be aware of all the relevant guidance.’

‘Very few members of the specialist team I work in are members of the TVS, and even fewer regularly read the up-to-date guidance due to this.’

‘The trust document was not written by ourselves [sic.], and we were not given the opportunity to comment!!’

Nine participants said that they had not implemented the SoTV seating guidelines into policy or practice yet, but had devised plans to do so. These participants set out a diverse range of plans for implementing these guidelines into practice related to adapting policy (n=8), the use of interdisciplinary education and training (n=8), developing information leaflets (n=3), creating posters (n=2), updating clinical guidelines (n=1), underpinning the continuous professional development of staff (n=1) and educating friends and family (n=1).

Another factor that may affect the implementation of the SoTV seating guidelines is the perspectives of individuals. One person expressed the view that these guidelines were an unclear discussion, suggesting that they did not merit incorporation into policy and practice. This was an opinion that contradicted the view of the majority of people in the survey (3). Most participants asserted that the guidelines were detailed, well-written with due consideration of the patient/service user perspective and disseminated in a variety of useful formats:

‘(The guidelines are) a discussion and are not clear.’

‘I am impressed that they (the guidelines) are developed from the service user perspective and are provided in a variety of formats i.e., video, paper, leaflet… (which) helps with educating patients and students/other staff.’

Discussion and the lessons learned

Reflecting on the data from the survey evaluation study (3) has shown us the importance of having theory-informed strategies and interventions with clear objectives that can be used to implement guidelines into practice. Therefore, we synthesised a theory based on the results of this study, the wider literature and our varied expertise as clinicians, researchers and academics. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that a theory has been devised in this manner, with the express objective of underpinning the implementation of wound care guidelines into practice. It must be noted that our reflection and conceptualisation is partly based on data from a limited number of participants (n=39) in one study. Nonetheless, we feel that this critical reflection provides novel and important insight into the clinical implementation of the SoTV seating guidelines, which may have wider relevance for the implementation of wound care-related guidelines.

The lessons from our critical reflection highlight some of the ways in which the reported variability in the implementation of wound care-related guidelines (16–18) can be addressed. Improving the implementation of guidelines in practice is vital, given their focus on informing key aspects of care organisation, service delivery, policy, practice or governance to embed the consistent delivery of safe, high-quality, person-centred care and attain the best possible patient outcomes (7, 8). Our view is that the process of translating SoTV seating guidelines into policy and practice is best understood as one with different stages, each of which is subject to the interplay of different factors.

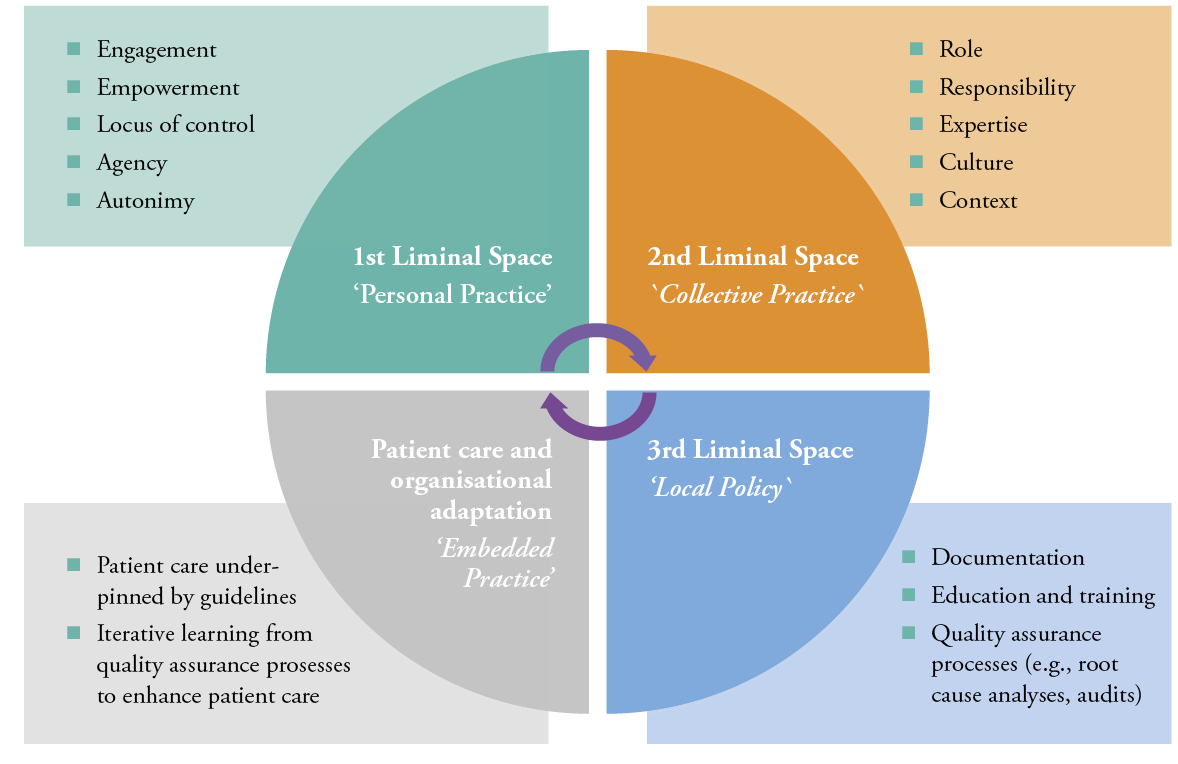

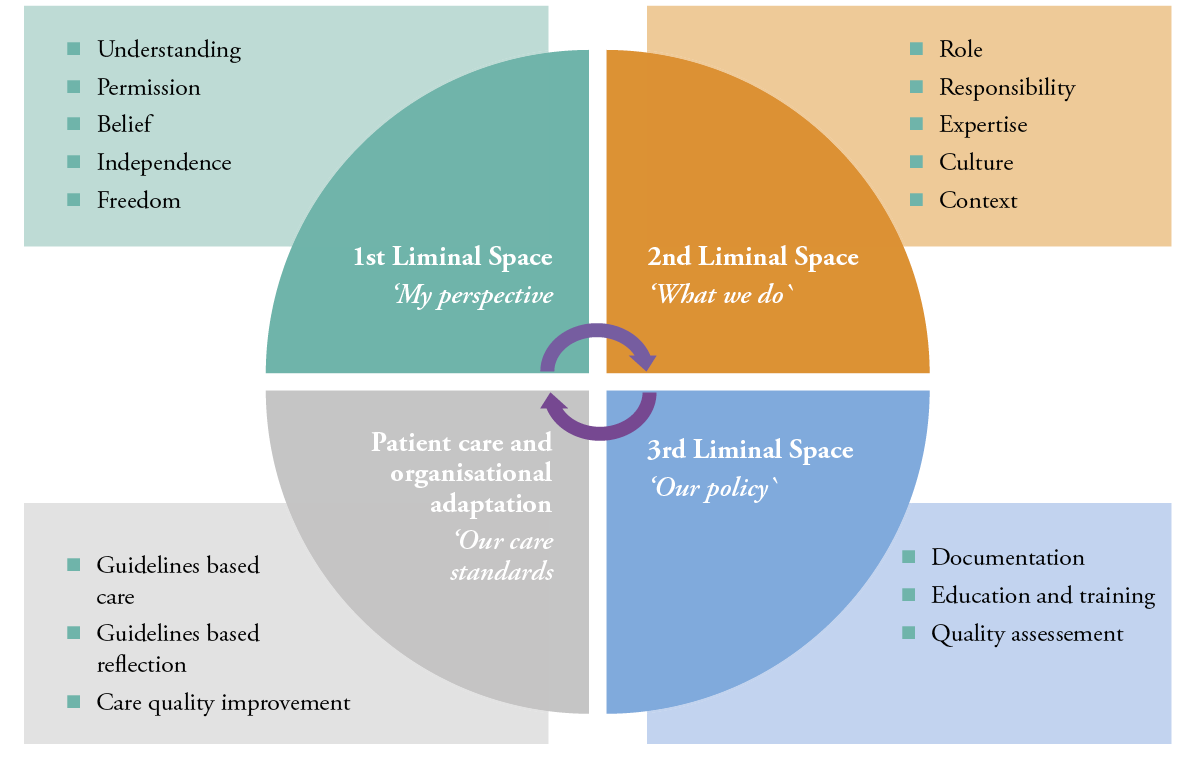

Our critical reflection using data from the survey evaluation, the wider literature and our experience enabled us to create a translation or implementation into policy or practice (TIPP) theory (Figures 1 and 2). We present this theory in both academic (Figure 1) and plain language (Figure 2) versions, so that it can be understood and used by the different groups of people who have a role to play in using the SoTV to underpin clinical practice.

Figure 1: Translation or Implementation into Policy and/or Practice (TIPP) theory, academic version

Stages of the guideline’s implementation trajectory into policy and practice

Figure 2: Translation or Implementation into Policy and/or Practice (TIPP) theory, plain language version

Stages of the guideline’s implementation trajectory into policy and practice

Our theory adds to the wider literature about factors that impinge, hinder or foster the translation of wound care-related guidelines in different contexts (15–18). Our results are also congruent with the view that implementing guidelines in practice is subject to the rapidly evolving, emergent, uncertain and contingent aspects of complex and adaptive healthcare systems (5, 20, 21, 23, 24, 27, 32). This paper and associated theory also provide some insight into the interplay of different individuals, agents, factors and perspectives with regards to the translation of the TVS seating guidelines into policy and practice with all its complexities. Initiatives to translate wound care guidelines into practice have been informed by a variety of perspectives, such as organisation- or theory-based approaches (18, 33). However, a systems thinking approach (4, 5, 21, 23), which recognises that there are complex interactions and connections among different individuals, perspectives, factors and agents in clinical practice, has seldom been used to inform the translation of wound care-related guidelines into policy or practice. We provide new insight, as our theory, based on critical reflection and informed by systems thinking, conceptualises the translation of the SoTV seating guidelines into policy and practice as a dynamic, recursive process. In our view, this process of knowledge translation appears to begin with changes to the individual practices of professionals, followed by changes to the collective practices of professionals, then revisions to local policy, culminating in embedded practice (Figures 1 and 2).

Our theoretical abstraction is congruent with the systems thinking conceptualisation of knowledge translation in which there are synapses of connectivity and interaction (2, 18) and formative feedback evaluation loops (1). This is because theory characterises the implementation trajectory of the SoTV guidelines as a series of interconnecting liminal spaces (34¬–36), consistent with the notions of synapses of connection and interaction and formative feedback evaluation loops, each of which has its own features (Figures 1 and 2). Liminal spaces are settings or situations in which a person or people go through a transition or transformation from one state of mind, way of thinking or identity that is bounded to another state of mind, way of thinking or identity with its own defined parameters (34, 35, 37). Liminal spaces exist in the theory practice gap in healthcare between the structured, ordered abstract aspects of healthcare, such as academia or technology, and the complex, emergent and uncertain nature of clinical practice (24, 36, 38). In our reflection, we extend the notion of liminal spaces described in the wider literature (24, 34–38) to different stages in the trajectory of SoTV seating guideline implementation, each with specific characteristics that are reflected in our concomitant theory. As far as we are aware, this is the first time that the translation of wound care-related guidelines into policy and/or practice has been conceptualised as an implementation trajectory with stages and liminal spaces. Consequently, our TIPP theory (Figures 1 and 2) extends contemporary knowledge about the characteristics and nature of the stages and liminal spaces in the implementation trajectory with regards to individual, collective and organisational practices. Our TIPP theory is consistent with elements in the wider literature on the translation into practice of wound care guidelines (15–18) and other aspects of healthcare (5, 21, 23, 27), but it merits further development and testing in subsequent research.

Incorporation into policy and practice

Our reflection focused on the variety of ways in which people may incorporate the seating guidelines into their practice or local policy. We brought to the fore different factors that appear to facilitate the translation of the seating guidelines into different spheres of practice. In what we conceptualise as the first liminal space, the participants in the SoTV evaluation study (3) described how the seating guidelines enabled them to seek greater interprofessional collaboration, a more holistic approach to care and a more comprehensive person-centred approach to patient assessment, care delivery and patient documentation. This suggests that these participants had translated these guidelines into policy and practice because they engaged with the guidelines in such a way that they felt empowered and had an appropriate locus of control, but also possessed sufficient agency and autonomy to change their practice or local policy. These results concerning what we describe as the first liminal space in the implementation trajectory are supported by other studies (16–19) and the literature (22). Individual factors, such as knowledge, competence, expertise and beliefs, have been shown to affect the integration of wound care and other healthcare-related guidelines in different settings (13–16). The notion of liminal spaces in the implementation trajectory of SoTV seating guidelines is also consistent with the notion of synapses of connection, interaction and formative feedback evaluation loops in the systems thinking approach to knowledge translation (4, 5, 22). This adds credence to our description of individual qualities, such as engagement, being integral to the translation of guidelines into practice in the first liminal space of the implementation trajectory.

The accounts about the integration of the SoTV seating guidelines into education, training and clinical decision-making in the evaluation study (3) also provide insight into the qualities of the people who engaged with their implementation in what we conceptualise as the first liminal space. These accounts indicate that these individuals were manifesting qualities that we have ascribed to the first liminal space, such as agency and autonomy. In using the guidelines as an educational and decision-making resource, these people in the SoTV evaluation study appear to move into what in our view is the second liminal space, where they actively sought to enact changes to collective practice. The accounts of the people in the second liminal space point to the fact that they were in roles, or had responsibilities, that enabled them to use their expertise and understanding of the seating guidelines to change collective practice with due consideration of culture and context.

In this second liminal space, participants in the evaluation study (3) reported using the SoTV guidelines to underpin education and decision-making. These reports indicate that the guidelines were, in effect, being used as a boundary object (24, 28, 39–41) to facilitate a shared understanding of how best to deliver pressure ulcer-related care with due consideration of seating-related issues to students and other healthcare professionals. Boundary objects are documents, models or maps that are concrete enough to be understood, but also abstract enough to be interpreted appropriately by people from different disciplines and professional communities (28, 42–44). Boundary objects facilitate learning and the dissemination of knowledge to people from different disciplines who may identify with different professional communities (28, 45–47). This is because they are malleable enough to be adapted to suit the specific circumstances, parameters and limitations facing the people who use them, but sufficiently robust to retain a shared identity in different contexts (24, 28, 40, 41). The reported use of these guidelines (1, 2) as boundary objects in the form of leaflets and posters was appropriate, given that they were designed to be used to improve the quality and safety of pressure ulcer-related care for people who remain seated for extended periods of time.

The notion of using the SoTV seating guidelines as a boundary object that facilitates the transition from the second to the third liminal space in the implementation trajectory is supported by the accounts of a few participants in the evaluation study (3) who had disseminated the guidelines as leaflets or posters adapted to suit their local context and culture. Those who used the guidelines as a boundary object can also be referred to as ‘implementation champions’ (17, 48) or ‘boundary spanners’ (28) whose enthusiastic efforts sought to integrate the guidelines into practice with the aim of enhancing the quality of pressure ulcer-related care for seated patients. Boundary objects, especially those that are collectively co-produced with all key stakeholders, are adept at facilitating knowledge translation into practice, as they effectively make use of shared contextual insights (5, 28). Quality improvement initiatives have demonstrated that implementation champions or boundary spanners are central to guideline translation because they devise, enact and evaluate the requisite changes to policy and/or practice (17, 28, 48). This wider evidence supports our nascent characterisation of the first two liminal spaces in the implementation trajectory where an individual possesses the requisite nous and impetus to function, in effect, as a champion or boundary spanner who facilitates the transition of the guidelines into the third and fourth liminal spaces.

At what we describe as the juncture of the second and third liminal spaces, the participants in the evaluation study (3) talked about the dissemination of guidelines resulting in key policy and practice changes, such as improved interprofessional collaboration and revised quality assurance processes to embed the best possible patient care. In our opinion, the accounts of changes to practice and policy by these participants herald a transition into the third liminal space, where enduring changes to collective practice are made to embed the guidelines into policy and practice in the trajectory towards the fourth liminal space. In this fourth liminal space of patient care and organisational adaption in the implementation trajectory, guideline-based patient care seems to be delivered consistently and monitored through quality assurance processes with iterative learning to improve outcomes. We refer to the fourth stage in the dynamic recursive implementation trajectory as ‘patient care and organisational adaptation’, because the SoTV seating guidelines were described as being fully embedded in local policies, collective practices and care processes.

Issues affecting implementation

Some accounts from the evaluation study (3) about issues affecting the translation of the seating guidelines into practice bolstered our conceptualisation of an implementation trajectory with distinct liminal spaces. Several participants said they had not integrated these guidelines into their own practices or local policies due to a lack of knowledge, agency, autonomy, resources or responsibility. A person’s knowledge, competence, expertise and beliefs have a direct impact on their efforts to deliver healthcare that is consistent with the guidelines for best practices. The evidence from other studies (16–19) underscores our view that the individual qualities we have described in relation to the first and second liminal spaces in the implementation trajectory are key to the translation of the SoTV seating guidelines into practice. Sometimes, shortcomings in the translation of guidelines into practice, such as those caused by gaps in knowledge, are due to passive dissemination approaches that reach a limited audience, such as journal articles (49, 50). It may be argued that passive dissemination approaches like these make it challenging for clinicians to increase their knowledge of guidelines, as their focus is on patient care in clinical practice. In this instance, these seating guidelines (1, 2) were disseminated through the SoTV, an open access journal article, social media and three conference presentations.

Wider awareness of guidelines can also be hindered by individual or collective perceptions about the nature of the underpinning evidence, views about the credibility of recommendations or an insufficient focus on a specific illness or disease (19). One person in the evaluation study expressed the view that the SoTV seating guidelines were a ‘discussion’ that did not merit changing policy and/or practice. It may be tempting to consider this view as a discordant outlier, but it merits further consideration because it indicates the impact that perceptions of, and engagement with, guidelines have on their use in clinical practice. In our perspective, this view suggests that this person is in the first liminal space and is unlikely to move further along the implementation trajectory until they have a higher level of engagement or are convinced about the utility of the guidelines. This lone view from the evaluation study also highlights the importance of persuading individuals about the evidence underpinning guidelines and why they often recommend changes to policy and practice. This person’s opinion also seems to demonstrate a misunderstanding about the fact that these seating guidelines (1, 2) were developed using a robust methodology drawing upon the existing evidence base, expert opinion and patient/service user input to devise recommendations for best practices for the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers in people who are seated.

This sentiment about the credibility of the SoTV seating guidelines (3) warrants greater scrutiny, as there are accounts in the wider literature (51, 52) of clinicians who perceive guidelines to be a series of aspirational goals, or who have doubts about their utility and relevance to their practice or patient care. One ethnographic study found that clinicians with this outlook tended to skim-read guidelines and only consulted them in greater detail when confronted with an unusual situation. Instead, the majority of patient care delivered by clinicians with this measured view of guidelines was found to be based on tacit ‘mindlines’ about best practices (51). These mindlines were described as personal or collective narratives used by individual healthcare professionals based largely on personal experience and often shared with others within a specific context or community of practice. The mindlines study suggests that the respondent in the SoTV evaluation study (3) articulated an atypical but important insight into how these seating guidelines are understood and used in different contexts or communities of practice. Therefore, more needs to be done to increase awareness about the evidence underpinning the SoTV seating guidelines, the process by which they were developed and their relevance to clinical practice.

We note with interest that the few participants in the evaluation study (3) who stated that the translation of these guidelines into practice was not their responsibility directly contradicted what is stated in the codes of professional practice (53, 54) for their disciplines. The responsibilities for healthcare professionals are also set out in these seating guidelines (1, 2). Translating guidelines into practice requires a multifaceted approach that gives due consideration to the variety of individuals, agents, factors and drivers that influence the delivery of care in the incessantly evolving context of healthcare (4–6, 17, 19, 21, 49, 52). Therefore, the challenges about the implementation of the SoTV seating guidelines reported in the evaluation study that fall into what we describe as the first and second liminal spaces point to the need for a more comprehensive dissemination approach to increase the levels of awareness, engagement and agency among those clinicians who are expected to use them to inform their practice.

Implementation strategy

A few participants in the evaluation study (3) mentioned the need for greater clarity or a more clearly defined strategy to enable them to translate the SoTV seating guidelines into policy and practice. These responses underscore issues relating to personal agency and responsibility that we relate to the first two liminal spaces. However, participants’ accounts also highlight the merit of integrating guidance on translation into policy and practice in future iterations of these guidelines, if they are to result in changes to patient care. In other words, these responses suggest that the provision of an implementation strategy alongside the guidelines may help to empower healthcare professionals who lack sufficient agency or responsibility to change policy or practice to improve patient care. The sentiment about the provision of guidance on implementation to empower healthcare professionals in practice has credence, as this iteration of the SoTV guidelines (22, 23) was not accompanied by specific information of this nature. It would be prudent, therefore, for the next iteration of the SoTV seating guidelines to be published with a detailed, proven implementation strategy suited to different contexts that is congruent with standards for best practice (16, 54, 55) in guideline translation.

Several participants in the evaluation study (3) who had yet to integrate the SoTV seating guidelines into practice described detailed plans about what they intended to do. A variety of approaches were set out to change their personal practice, collective practices and local policies. These views suggest that these participants had some of the qualities that we describe in relation to the first two liminal spaces in the guideline implementation trajectory. A central aspect of the proposed plans for implementation is related to the adaptation of the SoTV seating guidelines for use in the local context in different formats, such as leaflets, posters and revised policies. These narratives from the evaluation study reinforce the importance of adapting the SoTV guidelines into different formats that reflect the nature of care delivery in different contexts (51), such as boundary objects (27, 44–46), to expedite the implementation trajectory and process of change in clinical practice by bridging the gaps between the different liminal spaces.

Some participants in the study cited a lack of clinician engagement in the development of local policy and poor resource provision as barriers to the integration of the SoTV seating guidelines into practice. Empirical evidence from different settings (16, 27, 51) shows that organisational constraints, a lack of collaboration, poor resource provision and certain socio-cultural norms can preclude the implementation of guidelines in clinical practice. Wider evidence (22, 23) highlights potential strategies that could be used to overcome challenges in the translation of the SoTV seating guidelines include setting out with greater clarity the roles and responsibilities of individuals with regards to multidisciplinary collaboration (51, 56, 57), because they help shape social norms and implementation (58).

Strengths and limitations

Any consideration of our critical reflection must consider its strengths and limitations. This critical reflection was based, in part, on data from an evaluation study (3) with a self-selecting sample (n=39), most of whom described themselves as TVNs. This is a key consideration because it can be argued that TVNs have greater autonomy, agency and authority to incorporate these guidelines in policy and practice, compared to other people who might encounter them. Our conceptualisation of the results as indicative of an implementation trajectory with differing liminal spaces is aptly underpinned by empirical evidence, the wider literature, and a theory relating to wound care (16–19) and knowledge translation (5, 21, 23). However, this does not preclude the possibility of alternative and equally tenable conceptualisations of the data from the study and the wider literature. With this in mind, more research is needed to develop and test our theory concerning the implementation of other wound care-related guidelines. Such future research would help to establish the extent to which what we conceptualise as different liminal spaces in an iterative implementation trajectory which have distinct and shared characteristics.

CONCLUSION

Our critical reflection suggests that the translation of the SoTV seating guidelines into policy and practice occurs in an implementation trajectory with various liminal spaces. Individuals and groups must be supported to traverse the liminal spaces towards the superordinate objective of evidence-based, person-centred care and quality assurance processes. Each liminal space in the implementation trajectory of the SoTV seating guidelines set out in our theory is founded on specific accounts from the evaluation study (3). In addition, our theoretical abstraction of a seating guidelines implementation trajectory with differing liminal spaces is aptly underpinned by other empirical and theoretical evidence. This critical reflection, albeit limited in scope, is consistent with the wider literature and has generated some novel insights about the process of implementing the SoTV seating guidelines that point to the need for greater dynamism and ingenuity in the translation of wound care-related guidelines into practice.

This critical reflection merits particular consideration with regards to the implementation of other wound care-related guidelines (55–57). Guidelines are not ‘self-implementing’ (58) or ‘passively diffused’ (6), so their translation into policy and practice requires multifaceted approaches with due consideration of the complex interplay of individuals, factors and agents in different healthcare contexts (4–6, 17, 19, 21). A diverse range of empirical evidence (5, 6, 17, 18, 26, 27, 59) indicates it is prudent to develop, implement and evaluate complex interventions, underpinned by theory designed to embed guidelines, such as those for seating, into policy and practice. Our reflection adds to wider knowledge about the translation of wound care guidelines into practice. In particular, our paper suggests that efforts to enhance the quality and safety of wound care through guidelines should incorporate boundary objects (5, 24, 39–41), implementation champions or boundary spanners (17, 28, 48) and implementation drivers (18). This will serve to transcend what we characterise as liminal spaces in the implementation trajectory to embed evidence from wound care guidelines into policy and practice at the earliest opportunity. We encourage the SoTV and others with an interest in improving the quality and safety of wound care to reflect on the insights generated by this paper, our conceptualisation and recommendations to inform efforts to translate guidelines into practice.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

- The implementation of wound care guidelines needs to be underpinned by theory-informed strategies and interventions.

- The use of theories such as the translation or implementation into policy or practice (TIPP) theory can aid the implementation of guidelines into practice.

- Theory and the wider literature suggest that there is a wide range of strategies that can be used to implement guidelines in practice, such as boundary objects and implementation champions.

Further research

- Future research is needed to further test and develop the translation or implementation into policy or practice (TIPP) theory, especially with regards to its utility in embedding skin health and wound care-related guidelines into practice.

- There is an urgent need for studies that explore how theory-informed implementation interventions can be used to translate research evidence that underpins guidelines and evidence-based skin and wound-related care into clinical practice and policy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank everyone who took part in the survey that generated the data that we have reflected on and integrated into this paper. We would also like to acknowledge with thanks the advice and input of the Society of Tissue Viability Society (SoTV), formerly known as the Tissue Viability Society (TVS), Board of Trustees, who supported and facilitated the survey on which this paper is based.

Key messages

- Many guidelines seek to underpin evidence-based and person-centred wound care, but there is a lack of theoretical clarity about wound care guidelines’ implementation.

- We critically reflected on data from a recent study evaluating the implementation of the SoTV guidelines into clinical practice and policy within the wider literature.

- We have generated a wound care translation/implementation theory that can be used to integrate guidelines into practice.

Author(s)

Ray Samuriwo1, Melanie Stephens2, Carol Bartley3, Nikki Stubbs4

1Dr, PhD, School of Nursing and Healthcare Leadership, Faculty of Health Studies, University of Bradford, United Kingdom

2PhD, School of Health and Society, Mary Seacole Building, University of Salford, UK

3 MSc, Occupational Therapist Rehab for Independence Ltd, Lancashire, United Kingdom

4 MSc, Independent Nurse Consultant Tissue Viability NCS Wound Care Consulting Ltd

Correspondence: Ray Samuriwo, r.samuriwo@bradford.ac.uk

Conflict of interest

The Tissue Viability Society Board of Trustees supported the survey that generated the data used in this paper; however, the views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Tissue Viability Society Board of Trustees or the Tissue Viability Society.

No funding bodies had any role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Nikki Stubbs and

Dr Ray Samuriwo were, respectively, the Treasurer and Vice Chair of the Society of Tissue Viability Study (SoTV), formerly known as the Tissue Viability Society (TVS), when the original evaluation study was conducted in 2020. However, both of them wrote this paper in their personal capacity.

References

- Stephens M, Bartley CA. Understanding the association between pressure ulcers and sitting in adults what does it mean for me and my carers? Seating guidelines for people, carers and health & social care professionals. J Tissue Viability 2018; 27(1):59-73.

- Stephens M, Bartley C, Betteridge R, Samuriwo R. Developing the tissue viability seating guidelines. J Tissue Viability 2018; 27(1):74-9.

- Stephens M, Bartley C, Samuriwo R, Stubbs N. Evaluating the impact of the Tissue Viability Seating guidelines. J Tissue Viability 2021; 30(1):3-8.

- Braithwaite J, Glasziou P, Westbrook J. The three numbers you need to know about healthcare: The 60-30-10 challenge. BMC Med 2020; 18(1):102.

- Kitson A, Brook A, Harvey G, Jordan Z, Marshall R, O’Shea R, et al. Using complexity and network concepts to inform healthcare knowledge translation. Int J Health Policy Manag 2018; 7(3):231-43.

- Murad MH. Clinical practice guidelines: A primer on development and dissemination. Mayo Clin Proc 2017; 92(3):423-33.

- Gagliardi AR, Alhabib S. Members of the Guidelines International Network Implementation Working Group. Trends in guideline implementation: A scoping systematic review. Implement Sci 2015; 10(1):54.

- Shekelle PG, Woolf S, Grimshaw JM, Schünemann HJ, Eccles MP. Developing clinical practice guidelines: Reviewing, reporting, and publishing guidelines; updating guidelines; and the emerging issues of enhancing guideline implementability and accounting for comorbid conditions in guideline development. Implement Sci 2012; 7(1):62.

- IHI. How-to guide: Prevent pressure ulcers. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2011. Available at: www.ihi.org

- NPUAP, EPUAP, PPPIA. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: Clinical practice guideline. Osborne Park, Western Australia: Cambridge Media; 2014. Report No.: 0-9807396-5-9.

- Bus SA, van Netten JJ, Lavery LA, Monteiro-Soares M, Rasmussen A, Jubiz Y, et al. IWGDF guidance on the prevention of foot ulcers in at-risk patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2016; 32(S1):16-24.

- Game FL, Attinger C, Hartemann A, Hinchliffe RJ, Londahl M, Price PE, et al. IWGDF guidance on use of interventions to enhance the healing of chronic ulcers of the foot in diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2016; 32 Suppl 1:75-83.

- NICE. Pressure ulcers: Prevention and management of pressure ulcers. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2014.

- Bakker K, Apelqvist J, Lipsky BA, Van Netten JJ, Schaper NC. The 2015 IWGDF guidance documents on prevention and management of foot problems in diabetes: Development of an evidence-based global consensus. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2016; 32(S1):2-6.

- Ito T, Kukino R, Takahara M, Tanioka M, Nakamura Y, Asano Y, et al. The wound/burn guidelines – 5: Guidelines for the management of lower leg ulcers/varicose veins. J Dermatol 2016; 43(8):853-68.

- Weller CD, Richards C, Turnour L, Team V. Understanding factors influencing venous leg ulcer guideline implementation in Australian primary care. Int Wound J 2020; 17(3):804-18.

- Barker AL, Kamar J, Tyndall TJ, White L, Hutchinson A, Klopfer N, et al. Implementation of pressure ulcer prevention best practice recommendations in acute care: An observational study. Int Wound J 2013; 10(3):313-20.

- Scovil CY, Flett HM, McMillan LT, Delparte JJ, Leber DJ, Brown J, et al. The application of implementation science for pressure ulcer prevention best practices in an inpatient spinal cord injury rehabilitation program. J Spinal Cord Med 2014; 37(5):589-97.

- Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, Greiner W, Kraemer A. Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation-A scoping review. Healthcare. 2016; 4(3):36.

- Braithwaite J. Changing how we think about healthcare improvement. BMJ. 2018; 361:k2014.

- Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Long JC, Ellis LA, Herkes J. When complexity science meets implementation science: A theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med 2018; 16(1):63.

- Beauchemin M, Cohn E, Shelton RC. Implementation of clinical practice guidelines in the health care setting: A concept analysis. Adv Nurs Sci 2019; 42(4).

- Best A, Greenhalgh T, Lewis S, Saul JE, Carroll S, Bitz J. Large-system transformation in health care: A realist review. Milbank Q 2012; 90(3):421-56.

- Weeks KW, Coben D, O’Neill D, Jones A, Weeks A, Brown M, et al. Developing and integrating nursing competence through authentic technology-enhanced clinical simulation education: Pedagogies for reconceptualising the theory-practice gap. Nurse Educ Pract 2019; 37:29-38.

- Driscoll J, ed. Practising Clinical Supervision: A Reflective Approach for Healthcare Professionals. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2007.

- Birken SA, Powell BJ, Shea CM, Haines ER, Alexis Kirk M, Leeman J, et al. Criteria for selecting implementation science theories and frameworks: Results from an international survey. Implement Sci 2017; 12(1):124.

- Best A, Berland A, Herbert C, Bitz J, van Dijk Marlies W, Krause C, et al. Using systems thinking to support clinical system transformation. J Health Organ Manag 2016; 30(3):302-23.

- Melville-Richards LA, Rycroft-Malone J, Burton C, Wilkinson J. Making authentic: Exploring boundary objects and bricolage in knowledge mobilisation through National Health Service-university partnerships. Evid Policy 2019; xx(xx):1-23.

- Samuriwo R. Wounds Research Network (WReN) – A community of practice for improving wound care-related trials. J EWMA. 2019; 20(2):39-42.

- Allen D. Institutionalising emergent organisation in health and social care. J Health Organ Manag 2019: Published online ahead-of-print.

- Martin GP, Dixon-Woods M. Can we tell whether hospital care is safe? Br J Hosp Med 2014; 75(9):484-5.

- Allen D. Institutionalising emergent organisation in health and social care. J Health Organ Manag2019; 33(7/8):764-75.

- Cleary M, Visentin DC, West S, Andrews S, McLean L, Kornhaber R. Bringing research to the bedside: Knowledge translation in the mental health care of burns patients. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2018; 27(6):1869-76.

- Barrett RJ. The ‘schizophrenic’ and the liminal persona in modern society. Cult Med Psychiatry 1998; 22(4):465-94.

- Forss A, Tishelman C, Widmark C, Sachs L. Women’s experiences of cervical cellular changes: an unintentional transition from health to liminality? Sociol Health Illn 2004; 26(3):306-25.

- Lapum J, Fredericks S, Beanlands H, McCay E, Schwind J, Romaniuk D. A cyborg ontology in health care: Traversing into the liminal space between technology and person-centred practice. Nurs Philos 2012; 13(4):276-88.

- Rantatalo O, Lindberg O. Liminal practice and reflection in professional education: Police education and medical education. Stud Contin Educ 2018; 40(3):351-66.

- O’Callaghan A, Wearn A, Barrow M. Providing a liminal space: Threshold concepts for learning in palliative medicine. Med Teach 2020; 42(4):422-8.

- Bowker GC, Leigh. SS, eds. Sorting Things Out. Classification and its Consequences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2000.

- Mackintosh N, Sandall J. Overcoming gendered and professional hierarchies in order to facilitate escalation of care in emergency situations: The role of standardised communication protocols. Soc Sci Med 2010; 71(9):1683-6.

- Akkerman SF, Bakker A. Learning at the boundary: An introduction. Int J Educ Res2011; 50(1):1-5.

- Bakker A, Kent P, Hoyles C, Noss R. Designing for communication at work: A case for technology-enhanced boundary objects. Int J Educ Res 2011; 50(1):26-32.

- Fox NJ. Boundary objects, social meanings and the success of new technologies. Sociology. 2011; 45(1):70-85.

- Jensen S, Kushniruk A. Boundary objects in clinical simulation and design of eHealth. Health Informatics J 2016; 22(2):248-64.

- Carlile PR. A pragmatic view of knowledge and boundaries: Boundary objects in new product development. Organ Sci 2002; 13(4):442-55.

- Kerosuo H, Toiviainen H. Expansive learning across workplace boundaries. Int J Educ Res 2011; 50(1):48-54.

- Kimble C, Grenier C, Goglio-Primard K. Innovation and knowledge sharing across professional boundaries: Political interplay between boundary objects and brokers. International J Inf Manag 2010; 30(5):437-44.

- Eagle KA, Koelling TM, Montoye CK. Primer: Implementation of guideline-based programs for coronary care. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2006; 3(3):163-71.

- Feder G, Eccles M, Grol R, Griffiths C, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: Using clinical guidelines. BMJ 1999; 318(7185):728-30.

- Sheldon TA, Cullum N, Dawson D, Lankshear A, Lowson K, Watt I, et al. What’s the evidence that NICE guidance has been implemented? Results from a national evaluation using time series analysis, audit of patients’ notes, and interviews. BMJ 2004; 329(7473):999.

- Gabbay J, le May A. Evidence based guidelines or collectively constructed “mindlines?” Ethnographic study of knowledge management in primary care. BMJ 2004; 329(7473):1013-.

- Clay-Williams R, Hounsgaard J, Hollnagel E. Where the rubber meets the road: Using FRAM to align work-as-imagined with work-as-done when implementing clinical guidelines. Implement Sci 2015; 10(1):125.

- HCPC [Internet]. Standards of conduct, performance and ethics. London: Healthcare Professions Council; [2018]. Available at https://www.hcpc-uk.org/standards/standards-of-conduct-performance-and-ethics/

- NMC. The Code. Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses and midwives. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council; [2018]. Available at https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/read-the-code-online/

- Kottner J, Cuddigan J, Carville K, Balzer K, Berlowitz D, Law S, et al. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: The protocol for the second update of the international Clinical Practice Guideline 2019. J Tissue Viability 2019; 28(2):51-8.

- Barrois B, Nicolas B, Colin D, Fromy B, Barateau M, Gelis A, et al. French national guidelines for pressure ulcer (PU) prevention and care. Ann Physical Rehabil Med 2018; 61:e386.

- EPUAP, NPIAP, PPPIA. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries. 3rd ed.: Quick reference guide. Osborne Park, Western Australia: European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance; 2019. Report No.: ISBN 978-0-6480097-9-5.

- Grol R. Personal paper. Beliefs and evidence in changing clinical practice. BMJ 1997; 315(7105):418-21.

- Lin F, Marshall AP, Gillespie B, Li Y, O’Callaghan F, Morrissey S, et al. Evaluating the implementation of a multi-component intervention to prevent surgical site infection and promote evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2020; Article in press.