Volume 2 Issue 1

The impact of tunnelled vascular catheters on time to arteriovenous fistula creation

Hareeshan Nandakoban, Ananthakrishnapuram Aravindan, Tim Spicer, Govind Narayanan, Noemir Gonzalez, Michael Suranyi, Jeffrey K.W. Wong

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to examine the effect of the presence of tunnelled vascular catheter (TVC) on physician referral and surgeon review and operating patterns and ultimately time of creation of permanent haemodialysis (HD) access.

Methods: A retrospective analysis of TVC and arteriovenous fistulae (AVF) databases in 2010. Physician referral time and surgical time to operation were compared between patients commencing HD with TVC and a control group who commenced HD with AVF.

Results: The AVF group (n = 27) commenced HD with an AVF and TVC group (n = 49) commenced HD via a TVC. Time from physician referral to surgeon review in the AVF vs. TVC group was 29 vs. 35 days (p = 0.6). Time from surgeon review to access creation was 43 vs. 50 days (p = 0.4). However, in the TVC group, the time from TVC insertion to physician referral to a surgeon was an additional 109 ± 20 days. Subgroup analysis of 11 TVC patients (23%) presenting at end stage without AVF (crash starters) had a TVC to physician referral time of 103 ± 75 days, physician referral to surgeon review of 14.4 ± 4 days and surgeon review to AVF of 67 ± 23 days.

Conclusions: The presence of a TVC is associated with a significant delay (>3 months) before physicians make a referral for surgeon review. There was no surgeon-related delay to access creation related to the presence of a TVC.

Keywords: Arteriovenous fistula, Haemodialysis, Tunnelled vascular catheter

Reprinted from J Vasc Access 2016; 17 (1): 63-66 with permission of the Publisher.

INTRODUCTION

Haemodialysis (HD) is the most prevalent renal replacement therapy (RRT) in Australia and the absolute numbers are increasing every year (1). The type of incident modality of vascular access has been associated with varying morbidity and mortality and this has been seen both locally (2) and internationally (3, 11-13). The USRDS Morbidity and Mortality Study showed an increased relative risk of mortality of 1.7 (non-diabetic individuals) and 1.54 (diabetic individuals) in those dialysing with a tunnelled vascular catheter (TVC) compared with AVF (4). TVCs were associated with higher infection and cardiac causes of death (4). The importance of minimising patient exposure to TVC, especially in incident cases, has been highlighted in many studies like this and the CHOICE study (5).

The presence of a TVC for bridging access may potentially influence time for permanent access creation. TVCs are used when patients require HD and have no other permanent access available. Patients who have planned vascular access should commence HD with a mature arteriovenous fistula (AVF) or arteriovenous graft (AVG) created well before requiring their first dialysis session. Ideally, TVCs should be used for minimum periods as bridging access until permanent access (AVF/AVG) is ready for use. Delays in permanent access creation can occur at multiple time points in the care of a patient with end-stage kidney failure requiring dialysis.

We sought to examine the effect the presence of a TVC has on time for physician referral for vascular access surgical review; time to surgeon review and time to creation of an AVF.

METHODS

A retrospective analysis of the TVC and AVF database was performed from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2010 inclusive at a major public tertiary referral hospital renal service servicing four satellite dialysis centres. This database was managed by the vascular access clinical nurse specialist and overseen by a clinical nephrologist. Missing data from the central database or other data required for the audit were manually searched by the investigators by reviewing patient referral letters, surgical review letters and surgical operation reports available on the hospital’s electronic medical records (eMRs). The serum creatinine was retrospectively obtained by correlating the value from the hospital’s eMR and date of either TVC insertion or AVF surgery.

The timing for vascular access creation was dependent on the individual nephrologist and the surgery was coordinated through a single Access Nurse. In contrast, the TVC group included patients who needed immediate access for reasons, including failed AVF or PD technique, acute kidney injury and those with known chronic kidney disease and no dialysis access. The physician referral time and surgical time to operation were compared between patients commencing HD with a TVC (TVC Group) and a control group who commenced HD in the optimal manner with an AVF (AVF Group).

The date of TVC insertion was the date from first TVC insertion, or the date from a non-tunnelled catheter insertion that was converted to a tunnelled catheter, as the availability to TVC insertion is often limited by theatre time. The physician referral time was the date of the initial referral letter to the access surgeon. The surgical review date was date the patient was seen by the vascular surgeon as documented on correspondence letters. Missed or re-scheduled appointment information was not available. The date of access creation was the date of AVF surgery documented in electronic operation reports or follow-up correspondence from the vascular surgeon.

In addition, we assessed the time from TVC insertion to physician referral for surgical review in the TVC group. A subgroup analysis of the same period was performed of those patients who presented end-stage renal failure with no access, known as the ‘crash starters’.

Statistical analysis was undertaken using SPSS Version 17. Independent sample t-test was used on baseline group data and time to access creation with a p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed data. All data were de-identified and stored in a secure password-protected database.

RESULTS

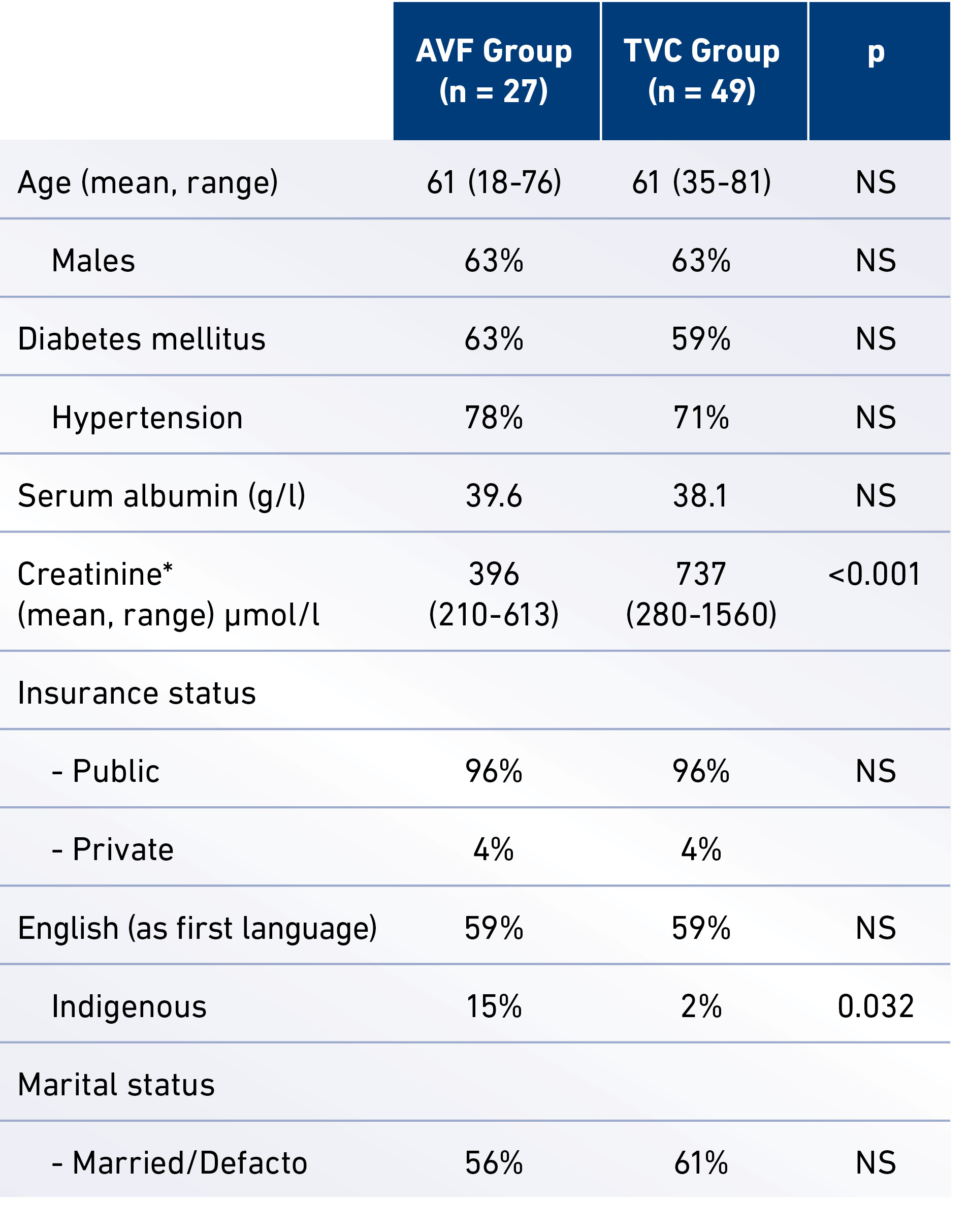

The AVF group had 27 patients and the TVC group had 49 patients. Baseline patient characteristics were similar between the two groups with respect to age, sex, serum albumin at time of first access creation, marital status (being single or a couple) and comorbidities of diabetes mellitus and hypertension (Tab. I). There was a male predominance (63%) with an average age of 61 years. As expected, the most significant difference of note was the higher mean serum creatinine at the time of TVC insertion of 738 µmol/l than that in the AVF group of 396 µmol/l. Funding for healthcare was 96% public through Medicare in both groups. Indigenous Australians were more likely to start dialysis with an AVF in this group than with a TVC; this result was significant; however, overall numbers were small (15 vs. 2%, p<0.05).

Table I. Patient characteristics

*Serum Cr recorded at the time of first access creation (either AVF surgery or TVC insertion).

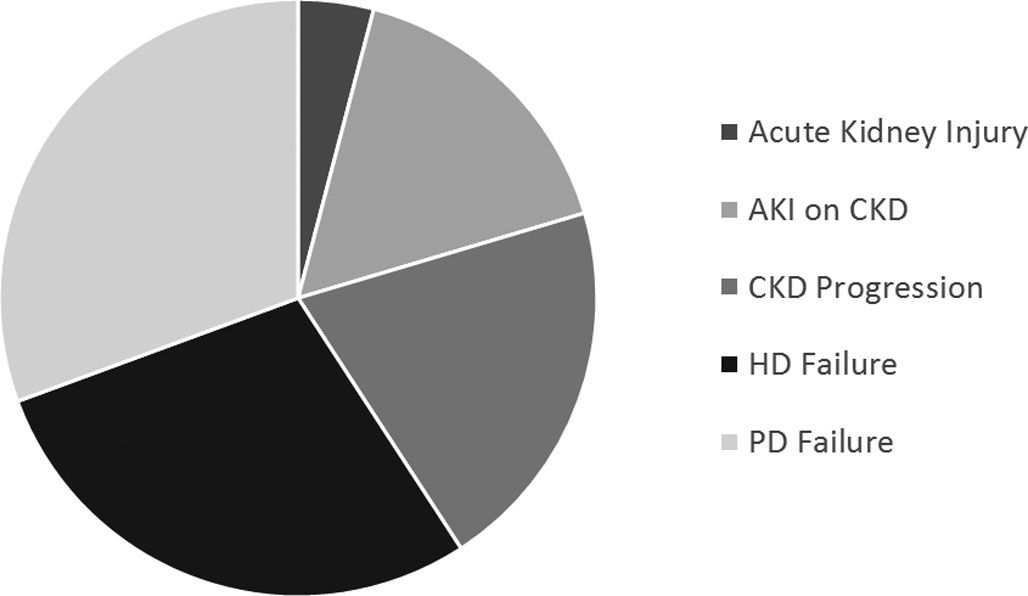

Failure of peritoneal dialysis technique and HD access (AVF or AVG failure) were the most common reasons for TVC insertions accounting for 60% of all catheters in that year. The crash starters (CKD progression) accounted for around one-fifth of TVC insertions (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Reasons for TVC Insertion.

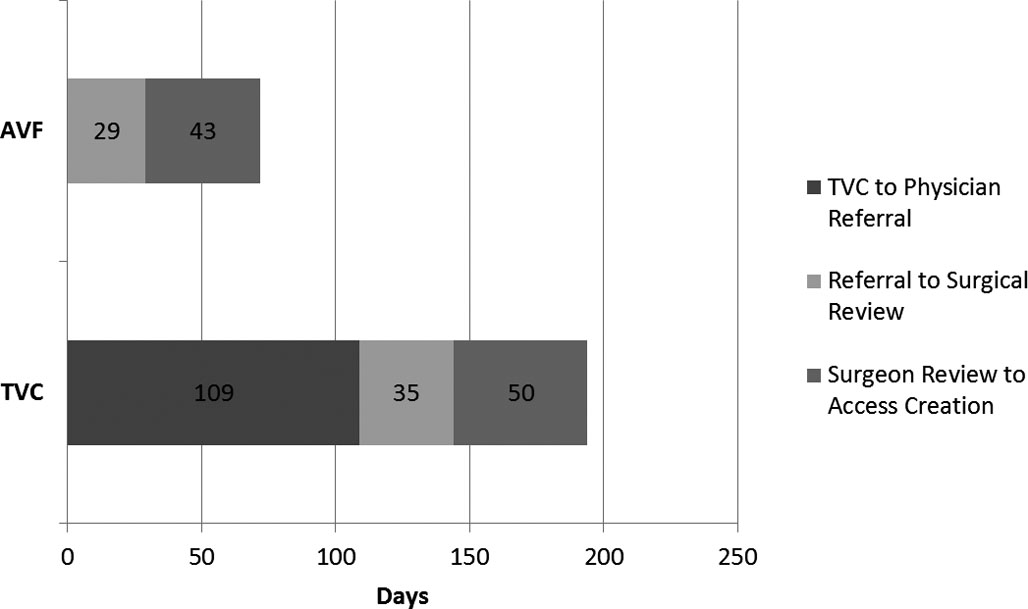

The mean time from physician referral to surgeon review in the AVF vs. TVC group was 29 vs. 35 days (p = 0.6). Mean time from surgeon review to access creation was 43 vs. 50 days

(p = 0.4). The total time from referral to AVF creation was numerically but not statistically higher in the TVC group at 85 vs. 72 days (Fig. 2). However, in the TVC group, the time from TVC insertion to physician referral to surgeon was an additional 109 ± 20 days (Fig. 2). Subgroup analysis of 11 TVC patients (23%) presenting at end stage without an AVF (crash starters) had a TVC to physician referral time of 103 ± 75 days, physician referral to surgeon review of 14.4 ± 4 days and surgeon review to AVF creation of 67 ± 23 days.

Fig. 2. Comparison of Times to AVF Creation (mean)

DISCUSSION

This retrospective cohort study demonstrated a significant delay of over 3 months (109 days) following TVC insertion before a physician makes the initial referral to a surgeon for permanent access. The hypothesis that a TVC may influence the surgeon’s practice and potentially delay creation was not seen. The results did not show any change in practice between the two groups with respect to the access surgeon’s time to review and prioritisation for AVF creation, all in the context of a study population demographically similar to those starting dialysis in Australia as per ANZDATA Registry 2011 with a mean age of 60.7 years and 61% being male (1).

This finding of delayed physician referral patterns is yet to be reported in the medical literature. The CHOICE study found that late referrals to nephrologist (<1 month prior to commencing dialysis) were highly likely (around 90%) to start with a TVC and the median duration was 202 days (6). Referral less than 12 months prior to dialysis start is an independent predictor of catheter use (OR 8.7) (7). This does not explain our local finding of nephrologist delays once a patient commences dialysis with a TVC.

International guidelines recommend AVF as the first choice for those patients commencing HD (8). The 2011 ANZDATA registry has shown that more patients started RRT with a tunnelled catheter (43%) than AVF or AVG combined (40%). Internationally, despite K/DOQI recommendations, the situation is no better with incident TVC use in Canada around 70% and the USA at 66%. The situation is preventable, as 79% of patients who commenced dialysis via a TVC had seen a nephrologist more than 4 months before (9). The DOPPS II Study showed that the mean time of ‘referral to surgical evaluation’ was highest at 25 days in Canada and lowest at 7 days in the USA. The mean time of ‘evaluation to surgery’ was 37 days in Canada and 9 days in the USA. This shows that despite Canada having the slowest time from referral to surgery of 62 days, the international results are superior to those seen in our centre (9).

Limited by the retrospective nature of this study, acute medical issues such as recent cardiovascular events and sepsis that prohibits elective surgery appear to account for some of this delay. Assessing for medical comorbidities and social factors did not show any difference between the two groups. Serum albumin was no different between groups to account for differences in nutritional state that could potentially delay a nephrologist to refer a patient for permanent access. English as first language and marital status was equally matched and unlikely to contribute to differences in time to referral for access creation. The health insurance status was predominantly all public funding and the same between both groups and this was not observed to alter the time to referral or surgery. We had a small number of Indigenous patients within both groups, and despite being a marginalised population, they were more likely to start dialysis with an AVF than with a TVC (15 vs. 2%). There are no protocols in the unit that dictate different strategies for managing Indigenous patients, but this may be a reflection of physician behaviour for a high-risk group in our dialysis population.

A subgroup analysis of the crash starter group found that they were seen more promptly by the surgeon in 14 days, but their overall time to access creation of around 81 days was no different compared with the AVF group. The total numbers in this subgroup analysis were however small to draw any significant conclusions.

The limitations of this study apart from being retrospective are the small numbers and single centre, and as such, reasons for delay in AVF creation can only be hypothesised. It is a reflection of practice at this tertiary training hospital over a 1-year period. The control group is inherently different to the patients who need a TVC as a temporary access due to a multitude of reasons from failed HD/PD to the ‘crash starters’. Patient preference for TVC is a known issue and was not accounted for in the retrospective review (10).

Despite our centre having a vascular access nurse, the low incident AVF use and delay to referrals post-TVC insertion may be a result of less streamlined referrals for vascular access surgery and poorer internal prioritisation. The implementation of a vascular access coordinator with an algorithm to prioritise surgery has shown an increase in AVF creation

in a single centre (14) and reduced incident catheter and

total catheter days (15). Predialysis care plans will direct patients, vascular access nurses and nephrologists to plan early for a native AVF, or if unavoidable an AVF soon after TVC

insertion (7).

CONCLUSION

The presence of a TVC is associated with a significant delay (>3 months) before physicians make a referral for a vascular access surgeon review in our centre. We did not observe surgeon-related delay to access creation related to the presence of a TVC. Active surveillance and policy directed to minimise TVC use and exposure should be implemented to improve patient care.

DISCLOSURES

Financial support: The authors have no financial disclosures to make.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest.

Meeting presentation: This study was presented as a Poster at the Australia and New Zealand Society of Nephrology Annual Scientific Meeting in 2011.

Author(s)

Hareeshan Nandakoban, Ananthakrishnapuram Aravindan, Tim Spicer, Govind Narayanan, Noemir Gonzalez, Michael Suranyi, Jeffrey K.W. Wong Renal Unit, Liverpool Hospital, Sydney, New South Wales - Australia

References

- Polkinghorne K, Dent H, Gulyani A, Hurst K, McDonald S.

ANZDATA Registry 2011 Annual Report: Haemodialysis [Online published report cited 5/12/2012]. 2011;34(5):2-3. - Polkinghorne KR, McDonald SP, Atkins RC, Kerr PG. Vascular access and all-cause mortality: a propensity score analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(2):477-486.

- Xue JL, Dahl D, Ebben JP, Collins AJ. The association of initial

hemodialysis access type with mortality outcomes in elderly Medicare ESRD patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(5):1013-1019. - Dhingra RK, Young EW, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Leavey SF, Port FK. Type of vascular access and mortality in U.S. hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2001;60(4):1443-1451.

- Astor BC, Eustace JA, Powe NR, Klag MJ, Fink NE, Coresh J; CHOICE Study. Type of vascular access and survival among incident hemodialysis patients: the Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for ESRD (CHOICE) Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(5):1449-1455.

- Astor BC, Eustace JA, Powe NR, et al. Timing of nephrologist referral and arteriovenous access use: the CHOICE Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38(3):494-501.

- Lopez-Vargas PA, Craig JC, Gallagher MP, et al. Barriers to timely arteriovenous fistula creation: a study of providers and patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(6):873-882.

- Fluck RKM. Vascular access for haemodialysis. In: Summary of clinical practice guidelines for vascular access for haemodialysis. UK Renal Association: 2011, Available at: www.renal.org/guidelines. p. 1.

- Mendelssohn DC, Ethier J, Elder SJ, Saran R, Port FK, Pisoni

RL. Haemodialysis vascular access problems in Canada: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS II). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(3):721-728. - Fissell R, Hakim RM. Improving outcomes by changing hemodialysis practice patterns. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013;22(6):675-680.

- Bray BD, Boyd J, Daly C, et al; Scottish Renal Registry. Vascular access type and risk of mortality in a national prospective cohort of haemodialysis patients. QJM. 2012;105(11):

1097-1103. - Lukowsky LR, Kheifets L, Arah OA, Nissenson AR, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Patterns and predictors of early mortality in incident hemodialysis patients: new insights. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35(6):

548-558. - Pastan S, Soucie JM, McClellan WM. Vascular access and increased risk of death among hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62(2):620-626.

- Polkinghorne KR, Seneviratne M, Kerr PG. Effect of a vascular access nurse coordinator to reduce central venous catheter use in incident hemodialysis patients: a quality improvement report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(1):99-106.

- Owen JE, Walker RJ, Edgell L, et al. Implementation of a pre-dialysis clinical pathway for patients with chronic kidney disease. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18(2):145-151.