Abstract

Introduction: Successful cannulation of arteriovenous fistula (AVF) or arteriovenous graft (AVG) is an important concept in hemodialysis. Metal needles have been used for cannulation in dialysis for over 50 years. Plastic cannula for dialysis is currently being introduced into Australia.

Aims: To identify if the implementation of plastic cannula could decrease the amount of miscannulations and adverse events in AVFs at first cannulation.

Methods: Train all staff in the Barwon Health renal department in the new technique of plastic cannula insertion and implement a new protocol for cannulation of AVFs in the first two weeks of dialysis.

Results: The training process took 12 months longer than anticipated due to issues with ‘expert’ to ‘novice’ reservations from staff, but initial results are positive with the statewide key performance indicator of new patients using AVF at first dialysis rising from 50% in 2013 to 78% in 2015. Staff were significantly more successful cannulating with plastic cannula in patients who had AVF only (67% success) than those who had a CVC alternative (24% success).

Conclusions: Plastic cannulas offer a new and innovative way to cannulate AVFs and with time, expertise and training can be utilized to provide a successful cannulation program for patients starting hemodialysis with AVFs.

Keywords: Cannulation, Dialysis, Plastic cannula, Renal, Vascular

Reprinted from J Vasc Access 2016; advance online publication with permission of the Publisher.

INTRODUCTION

Successful cannulation of arteriovenous fistula (AVF) or arteriovenous graft (AVG) is an important concept in hemodialysis. It is imperative that cannulation is successful to decrease adverse events, such as extravasation of the vessel (either during cannulation or during the hemodialysis session) hematoma formation, long-term aneurysm formation or narrowing of the vessel due to intimal hyperplasia from scarring. Unsuccessful cannulation in the initial period after maturation can lead to deferred dialysis, hematoma formation, scarring, needle phobia, loss of cannulator confidence and costs related to sending patients home, or to diagnostic imaging to identify the issue or perhaps insertion of a central venous catheter (CVC). Over the past 50 years most countries have used metal cannulation needles, which stay in the access for four to six hours at a time. In the mid-2010s companies in Australia had noted Japan’s excellent vascular access outcomes using large-bore plastic cannulas to access their AVFs. Staff at Barwon Health renal department, Geelong, guided by the vascular health nurse, implemented a program of staff training and adopted a protocol related to the use of plastic cannulas for new AVFs in the first two weeks of hemodialysis. The aim of the study was to identify if the implementation of plastic cannulas could decrease the amount of miscannulations and adverse events in newly cannulated AVF.

BACKGROUND

Cannulation practices

Cannulation techniques of area puncture and rope ladder (1) have existed since the 1960s from when the Brescia-Cimino AVF was first created (2). The only significant change in cannulation techniques came in the form of the buttonhole, or constant site, cannulation technique in 1973 (3). Since then there have been many discussions comparing the three techniques (4). All have pros and cons but global guidelines suggest rope ladder is the preferred mode of cannulation to prolong the lifespan of the access and reduce adverse outcomes (5, 6). A recent study suggested that even when staff perceive they are implementing the rope ladder technique, approximately two-thirds of patients are identified as having area puncture sites (7). Cannulators can initiate the rope ladder technique but be hindered by things such as short segments of vessel, tortuosity of vessels, proximity to the ante-cubital fossa and presence of aneurysms (8).

These cannulation issues have sometimes been overcome by surgical or endovascular interventions to improve the length of useable vessel (9). There have been significant improvements in surgical techniques, endovascular techniques and understanding of the pathology and remodeling of the vessels during maturation (1, 10). Some improvements in cannulation practices have been 1) shorter or longer needle length for shallow or deep vessels (within limitations) and 2) use of point of care ultrasound for assessment and/or guided cannulation (11). Perhaps the biggest change to cannulation practices to date is the introduction of the plastic cannula for hemodialysis.

Plastic cannula for hemodialysis

The plastic cannula has been used in Japan for over 20 years on approximately 300,000 patients dialyzing thrice weekly with very little reported evidence of adverse outcomes (12). In Australia the Centre for Healthcare Related Infection Surveillance and Prevention and Tuberculosis Control has stated that metal needles should not be used for peripheral vascular access in the general hospital population (13). However, hemodialysis units have continued to use the metal needles despite this recommendation.

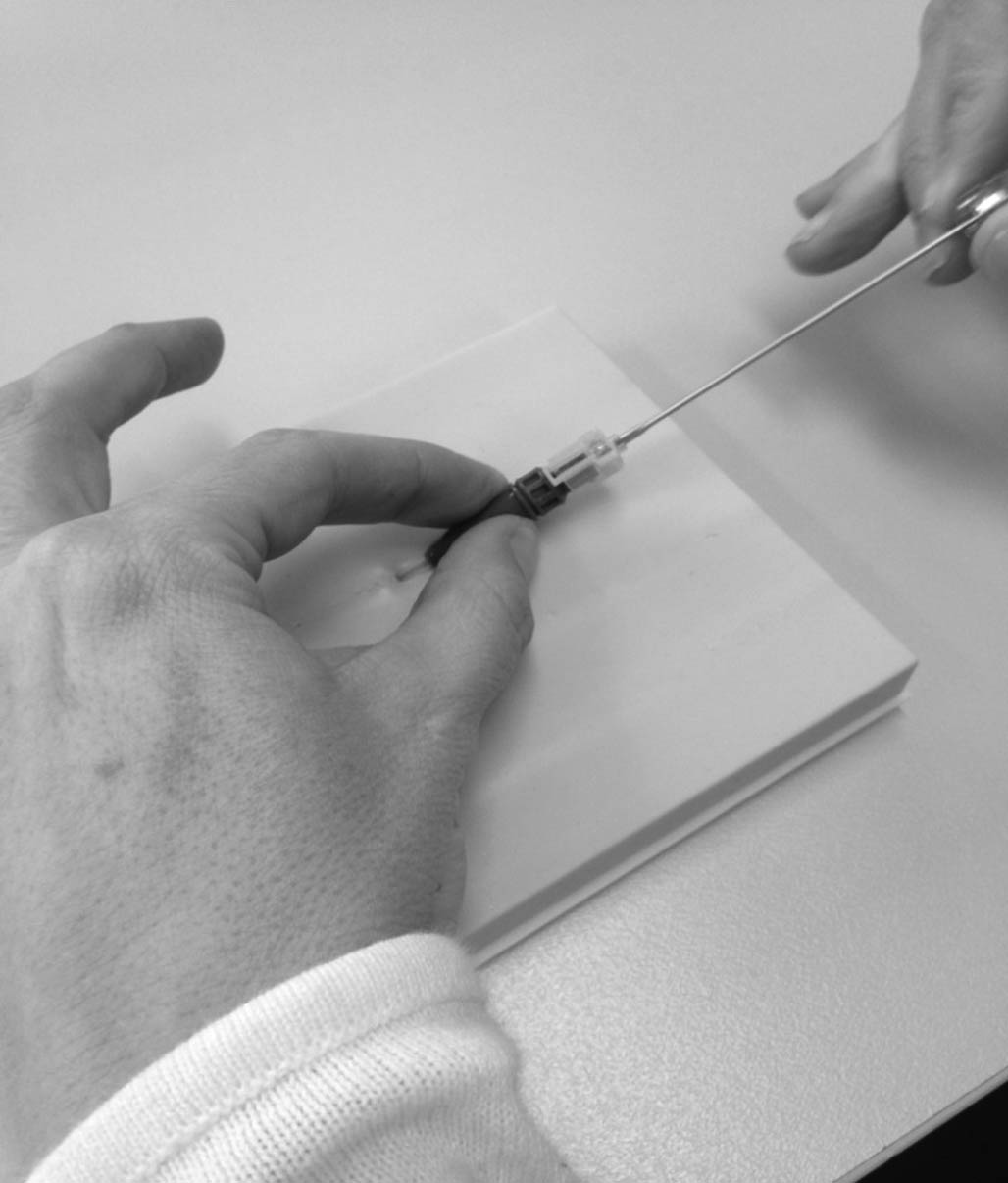

Since 2013, the plastic cannulas have started to be used in renal units in Australia (Fig. 1). Du Toit reported after a visit to Japan, that patients could be cannulated in the antecubital fossa, tortuous parts of the vessels, and that the patients were able to move their arms during dialysis without fear of extravasation (14). It was also noted that there was no risk of the plastic cannula piercing the side of the vessel either putting tape on or off. Patients could also push down on the plastic cannula during removal, a practice that cannot be done with metal needles due to the risk of slicing the vessel (14).

Figure 1. Plastic cannula

Grainer also reported success with the plastic cannula, detailing 120 cannulations, mostly under the guidance of ultrasound (15). The success was with patients who moved their arm and extravasated the vessel during hemodialysis and patients with immature AVFs (according to the rule of sixes (5)). Most of these ‘immature’ AVFs had access flows in excess of 600 mL/min but lacked the diameter of vessel required to meet the rules. In these cases, if metal needles were used (even under ultrasound guidance), there would often be an extravasation or back-walling of the vessel leading to a miscannulation (15).

The vascular health nurse at the renal department at Barwon Health identified similar issues, so it was decided that the staff would be trained in the use of the plastic cannula over an estimated period of six months. After the initial training period it was hypothesized that the patient population most likely to benefit from the plastic cannula would be patients with AVFs in the first two weeks of cannulation. Whilst the plastic cannula could be of benefit to all patients, the cost restraints of the product meant their use needed to be prioritized to a sub-population of the unit.

METHODS

The implementation

Plastic cannulas were first observed in Australia in 2013 where possible benefits touted were: a reduced risk of infiltration, reduced trauma to tissue and vein and the ability to cannulate difficult and tortuous sections of the AVF. Although there was no evidence in the literature to support their use at that stage, the concept was sensible and had to offer patients a better alternative to metal needles. These benefits warranted further investigation and it was proposed that the cannula could be used on all patients starting hemodialysis with AVFs for a period of two weeks (six hemodialysis sessions) to see if there was a decrease the incidence of miscannulation or adverse events. The proposal was put to management, justifying the use by using some rudimentary figures, but qualifying that spending AUS$46.80 on plastic cannula for a two-week period could perhaps save the insertion of a AUS$509.40 CVC (plus on costs). Before implementing this proposal the vascular health nurse had to train all the staff in the new technique.

Staff training

In-service training sessions were initially conducted by the vascular health nurse and a Covidien representative to introduce the new technique to the staff and allow opportunity for practice of the new technique on phantoms under guidance. These sessions were then followed up by a one-

on-one practical session with the vascular health nurse where staff had to attempt at least 10 successful cannulations on a practice cannulation arm. Following this, the staff were required to undertake three supervised successful cannulation sessions on mature AVFs. For example, each of these sessions had to be completed with both arterial and venous needles appropriately in situ and adequate pump speed and machine pressures within normal limits.

Technique

The technique for inserting the plastic cannula was very different to inserting a metal needle. There were no wings to hold on to and it was longer in length, resulting in the cannula being held further back, eliciting the feeling of less control of the needle (Fig. 2). When traditional metal needles initially puncture the vessel a pulsing flashback of blood is seen in the tubing to indicate success. However, with the plastic cannula the flashback of blood does not pulsate, making staff question their success. Once the vessel was punctured the cannula was introduced a few more millimeters so the bevel was completely in the vessel. Failure to do so led to miscannulation and the inability to slide the cannula over the introducer into the vessel. Once the bevel was inside the vessel, the adaptor was disconnected and the cannula slid into the vessel whilst simultaneously removing the introducer (Fig. 3), then taped and flushed with saline. The plastic cannula has an anti-reflux valve, so there is no danger of blood spilling out of the cannula during this process (Fig. 4). The attachment of the dialysis lines continued unchanged to previous practice. All patients had a pre-cannulation ultrasound performed by dialysis nurses with depth and diameter of vessel measured. Appropriate cannulation sites were then chosen and subcutaneous anesthetic was used if the patient requested.

Figure 2. Plastic cannula insertion technique

Figure 3. Removal of the introducer from the plastic cannula

Figure 4. Plastic cannula taped in situ

RESULTS

The initial training timeframe was hypothesized to be six months, whereas the training of all 40 staff to be proficient using the plastic cannula took 18 months. Some staff had initial reservations to the change to plastic cannula and were opposed to learning a new technique. This also meant that there were not enough staff trained initially across all shifts to maintain continuity, resulting in intermittent use of metal needles and CVCs (that were already in situ). There were also issues with staff who had been deemed competent via the training protocol but did not use plastic needles in mature AVFs regularly enough to keep up the new skill, then were not confident to use the cannula on a new AVF. The staff who did continue to insert plastic cannulas into mature AVFs regularly, adopted the practice and attempted the challenge of cannulating new fistulas successfully.

Miscannulation was not initially decreased due to inexperience of the cannulators. This was generally that the bevel was not all the way into the vessel before threading the cannula. One drawback of the cannula is that once it is in the vessel and the introducer has been removed, if the cannula cannot be flushed there is no recourse for manipulation of the cannula to encourage flow. The cannula needed to be removed and a new one inserted elsewhere in the vessel.

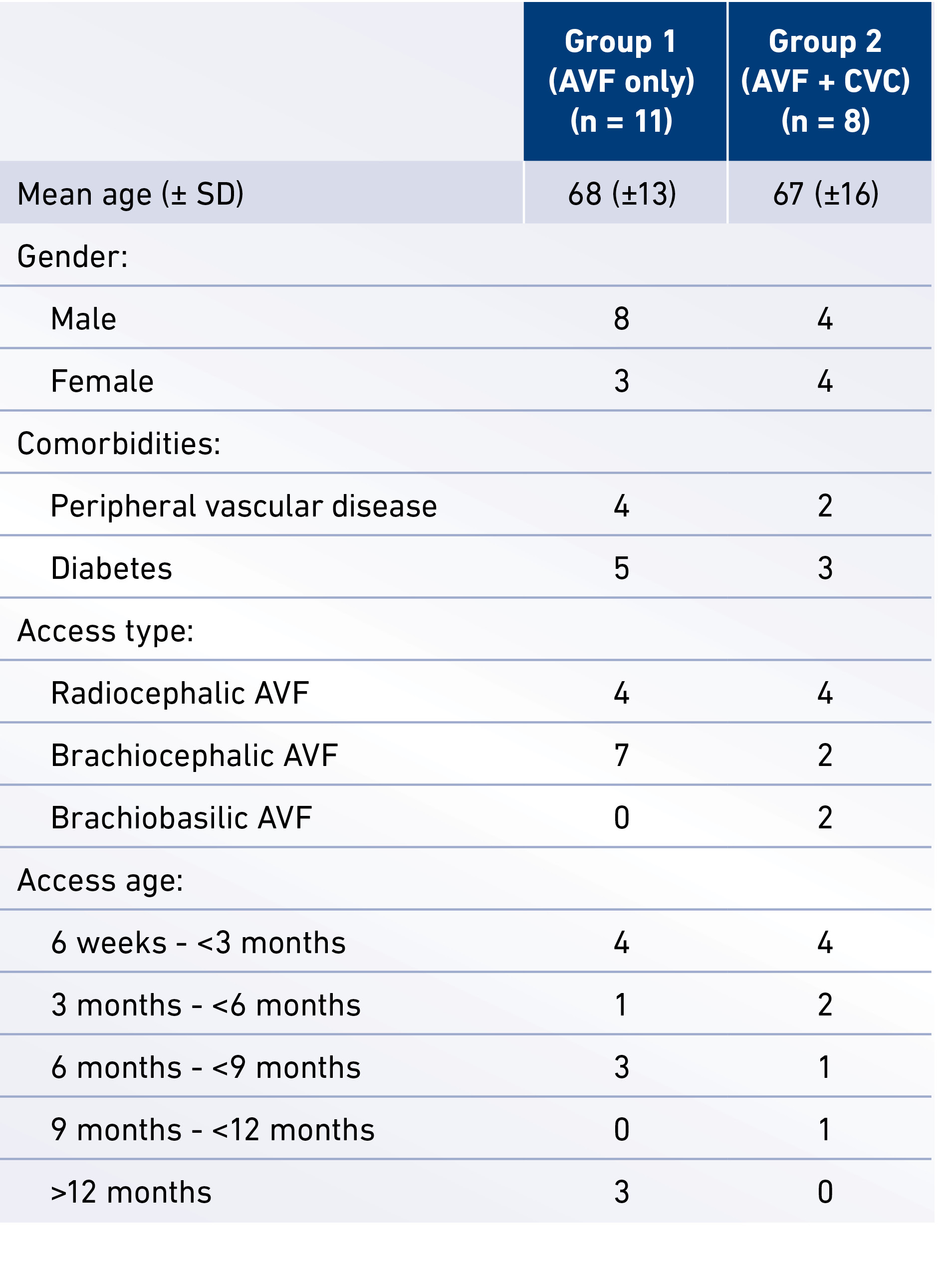

Over 15 months, the plastic cannula has been used on 18 patients; 11 incident patients with AVFs only and eight patients who initially started hemodialysis with a CVC (prior to the introduction of plastic cannula) but later had an AVF created (Tab. I). Staff were successful with plastic cannula insertion most of the time (67%) when the patient did not have a CVC in situ. This accuracy decreased (24%) when the patient had a CVC in situ, which was an easy alternative to cannulation using a new technique (Tab. II). Hematoma formation from miscannulations was not accurately recorded by staff therefore not included in these results. There was no difference in cannulation success related to type of AVF or age of the AVF.

Table I. Demographic data

AVF = arteriovenous fistula; CVC = central venous catheter

Table II. Cannulation results

AVF = arteriovenous fistula; CVC = central venous catheter

Statewide key performance indicators have been set by the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services to benchmark dialysis data across the state and include nine dialysis centers. One key performance indicator measures the percentage of patients who successfully used an AVF or AVG at first hemodialysis treatment (planned dialysis patients). In 2013, Barwon Health had 50% of planned hemodialysis patients successfully using AVF or AVG at first dialysis treatment. Plastic cannulas were introduced in March 2014 and at June 2015 this key performance indicator has risen to 78% (well over the state benchmark of 70%). Whilst this improvement cannot solely be attributed to the use of plastic cannulas it has certainly contributed to the increase in this key performance indicator.

DISCUSSION

The introduction of plastic cannulas for hemodialysis in Australia is a very exciting development. There have been no bigger changes to cannulation practices in hemodialysis. The majority of other areas within healthcare moved away from metal needles many decades ago. It was in the 1950s that damage such as infiltration, scarring and infection were identified in relation to the use of metal needles for peripheral venous access and it was “imperative that a more reliable, safer device to administer treatments was invented” (16). If this was the case prior to the beginning of cannulation for hemodialysis, it makes us wonder why cannulation of AVFs was begun and continued for so many decades using devices that were known to cause vessel damage in something that was considered the patient’s lifeline. Perhaps the plastic was initially not strong enough to enter the thickened lining with the introducer or perhaps large-bore cannulas were not produced or the cannula could not withstand the ‘sucking’ pressure of the pump? Perhaps no-one thought to try it, or maybe it all relates to cost? Whatever the reason, the good news is that the plastic cannulas are here now and there are some positive signs in these early stages of their use.

The introduction of change however can be a difficult path. Whilst the literature and previous experience of others (14, 15) was a contributing factor in the introduction of the plastic cannula, it took encouragement and perseverance from the vascular health nurse to convince and train all staff in the new technique. One of the things that may have impacted the long training time was the inexperience of the vascular health nurse in the new cannulation technique. Perhaps training the vascular health nurse to ‘expert’ level initially may have expedited the program. Most staff identified that the introduction of plastic cannulas was an exciting and innovative new development for vascular access; however, some of the experienced staff were resistant to their introduction. After many years of using metal needles the resistance was the difference in technique and the notion of no longer being ‘expert’ and reverting back to ‘novice’ status. It was particularly challenging when ‘novice’ renal nurses come from a background of peripheral cannulation in general wards and found the technique easy to implement. This allowed for a situation where the novice became expert quickly in relation to cannulation and the expert became novice. An interesting phenomenon that was difficult to overcome.

Although there was initially an increase in miscannulations, these were not as disastrous as with metal needles. When a miscannulation occurs with a metal needle it can be due to missing the vessel completely or infiltration of the vessel causing pain and hematoma formation around the vessel. The miscannulations with the plastic cannulas were mostly related to not progressing the needle far enough into the vessel before threading the plastic cannula, thus the plastic cannula either could not be threaded or it crumpled on insertion. This would require removal of the needle and restarting the cannulation process with a new cannula. The introducer is two gauges smaller than the cannula, much smaller than a metal needle. The hole in the vessel is therefore very small and there is minimal hematoma formation, which allows for more attempts to cannulate that particular AVF. For example, a new AVF cannulated with a metal needle has an infiltration, which causes a large hematoma. There is considerable area of that vessel that now cannot be punctured. This may decrease the ability to place two needles successfully but with the plastic cannula the hole is so small, even with miscannulation it is possible to attempt further cannulations, even in a newly matured AVF. Another interesting finding was that the staff were more likely to revert to the use of CVC if there was one in situ, rather than persevere with cannulation with the plastic cannula.

Other positives of the plastic cannulas are that they offer flexibility in cannulation sites, such as the antecubital fossa, that are inaccessible with metal needles. This allows staff to use the rope-ladder technique for cannulation more proficiently rather than continuing area puncturing practices. It is not as traumatic for the patient and there is less trauma to vessel and surrounding tissue and can be used on a vessel if there has been an extravasation with a metal needle.

It is a long process to change over from the metal needles to plastic cannulas but with less miscannulations (long term) and fewer adverse outcomes for new AVFs in the first two weeks, it is worth it. Tips for those starting out; it is a huge learning curve for staff, keep in mind that this is the biggest change to cannulation practices for almost 60 years. It is a different technique, which takes practice and time to improve to reach cannulation success. It is important that the educator (person driving the implementation) persists and motivates staff to continue using cannulas after the initial training and three supervised cannulations are not enough to become proficient with the new technique. All staff need to be trained in order to offer continuity over all shifts on all days, otherwise there will be intermittent metal needles or CVC use. Encourage staff to continue to use plastic cannulas on mature fistulas weekly until they become proficient with the technique, which can take up to a month. Cost is a major factor in the use of these cannulas and at present it is not cost effective to use past the two- to three-week mark.

CONCLUSION

It is only the early stages of the implementation of the plastic cannula into the hemodialysis unit. Over the past 18 months it has been a difficult and challenging exercise but the outcomes of the implementation are now coming to fruition. It is now protocol with the hemodialysis unit that all new fistulas are cannulated with plastic cannulas for a minimum of six hemodialysis sessions and all 40 staff across four units, including in-center, satellite, and home training units are trained to insert plastic cannula. Staff have taken time to embrace their use but perseverance and determination from the vascular health nurse has proven that over time a change in cannulation practice can be a positive experience for both staff and patients. Plastic cannulas offer a new and innovative way to cannulate AVFs and with time, expertise and training can be utilized to provide a successful cannulation program for patients with new AVFs.

DISCLOSURES

Financial support: No grants or funding have been received for this study.

Conflict of interest: None of the authors has financial interest

related to this study to disclose.

Author(s)

Vicki Smith1, Monica Schoch2 1 Barwon Health Renal Department, Geelong, Victoria - Australia 2 Deakin University, Waterfront Campus, Geelong, Victoria - Australia

References

- Donnelly SM, Marticorena RM. When is a new fistula mature? The emerging science of fistula cannulation. Semin Nephrol. 2012;32(6):564-571.

- Brescia MJ, Cimino JE, Appel K, Hurwich BJ. Chronic hemodialysis using venipuncture and a surgically created arteriovenous fistula. N Engl J Med. 1966;275(20):1089-1092.

- Twardowski Z, Kubara H. Different sites versus constant sites of needle insertion into arteriovenous fistulas for treatment by repeated dialysis. Dial Transplant. 1979;8:978-980.

- Gallieni M, Brenna I, Brunini F, Mezzina N, Pasho S, Fornasieri A. Which cannulation technique for which patient. J Vasc Access. 2014;15(Suppl 7):S85-S90.

- National Kidney Foundation’s KDOQI 2006 Vascular Access Guidelines. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48(suppl 1):S177-S322.

- Polkinghorne KR, Chin GK, MacGinley RJ, et al. KHA-

CARI Guideline: vascular access - central venous catheters, arteriovenous fistulae and arteriovenous grafts. Nephrology (Carlton). 2013;18(11):701-705. - Parisotto MT, Schoder VU, Miriunis C, et al. Cannulation technique influences arteriovenous fistula and graft survival. Kidney Int. 2014;86(4):790-797.

- Besarab A, Kumbar L. Vascular access cannulation practices and outcomes. Kidney Int. 2014;86(4):671-673.

- Tordoir JH, van Loon MM, Peppelenbosch N, Bode AS,

Poeze M, van der Sande FM. Surgical techniques to improve cannulation of hemodialysis vascular access. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39(3):333-339. - Roy-Chaudhury P, Kruska L. Future directions for vascular access for hemodialysis. Semin Dial. 2015;28(2):107-113.

- Schoch M, Du Toit D, Marticorena RM, Sinclair PN. Utilizing point of care ultrasound in vascular access for haemodialysis. Renal Society of Australasia Journal. 2015;11(2):

78-82. - Nakai S, Iseki K, Itami N, et al. An overview of regular dialysis treatment in Japan (as of 31 December 2010). Ther Apher Dial. 2012;16(6):483-521.

- Centre for Healthcare Related Infection Surveillance and Prevention and Tuberculosis Control (CHRISP). Peripheral Intravenous Cannulation Guideline V2. 2013. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/publications/clinical-practice/guidelines-procedures/diseases-infection/governance/icare-pivc-guideline.pdf. Accessed January 04, 2016.

- Du Toit D. Haemodialysis needles: Why do we use metal fistula needles? Renal Society of Australasia Journal. 2013;9(3):138-140.

- Grainer F. Plastic (non-metal) fistula cannula: from concept to practice. Renal Society of Australasia Journal. 2014;10(1):44-46.

- Kelly L. Pig bladders and feather quills:a history of vascular access devices. Br J Nurs. 2014;23(19):S21-S24.