Volume 2 Issue 1

The impact of a dedicated renal vascular access nurse on haemodialysis access outcomes

Yanella Martinez-Smith, Shelley Tranter

Abstract

A dedicated renal vascular access nurse (VAN) role was introduced in a large dialysis service in 2005. To evaluate the impact of the role, vascular access outcomes for arteriovenous fistula (AVF) at first dialysis, vascular catheter use, and access thrombosis and infection rates were benchmarked to national and international guidelines.

At the end of 2014, a retrospective audit was conducted on the vascular access outcomes data. The percentage of patients with a functioning AVF on dialysis commencement was 61% compared to 46% nationally. Prevalent data reveal that 92% of patients were using an AVF or AV graft for haemodialysis, surpassing the national benchmark of 85%. The AVF thrombosis rate was 0.09 episodes/patient year compared to the recommended rate of <0.25 episodes/patient year at risk. The recommended vascular catheter-related bacteraemia rate of <1.5 episodes/1000 catheter days was surpassed at 0.29 episodes/1000 catheter days, with one catheter-related infection for a total of 93 catheters in situ. There were no infections reported for AVFs and AV grafts.

The introduction of the renal VAN position has resulted in a steady improvement in vascular access outcomes over the past decade for patients in this dialysis service.

Keywords: Vascular access, nurse, haemodialysis.

INTRODUCTION

Ensuring adequate and long-term vascular access is key to the success of the chronic haemodialysis process. Unfortunately, there is an increased demand for dialysis, especially in the frail elderly and in those who have one or more co-morbidities affecting their chances of having a vascular access created and ready for use when required. In addition, making sure a patient’s arteriovenous fistula (AVF) or graft (AVG) is created in time for haemodialysis is an important part of predialysis preparation; however, making sure it continues to remain viable and able to support optimal dialysis is just as important. In an effort to streamline renal vascular access processes and improve outcomes for the patients in our dialysis service, the renal vascular access nurse (VAN) position was created in 2005. Funding for the first two years of the position was provided by an unrestricted grant from a pharmaceutical company but it is now funded as part of the Renal Service.

The last decade has seen the emergence of the dedicated vascular access role in most large dialysis services. The functions and responsibilities of the role vary, but the main purpose of implementing a specialist nurse in the role is to improve vascular access outcomes1.

There has been little literature on the impact of the renal VAN, sometimes referred to as the renal access coordinator (RAC). In one paper a RAC details the components of her role but does not provide the reader with any clear outcomes from the introduction of the position2. A more comprehensive overview of a renal vascular access manager position was discussed in regard to improving outcomes across a large dialysis service in the United States (US)3. The implementation of a renal vascular access manager with detailed vascular access protocols improved the AVF rate for prevalent (existing) patients from 50% to 65% over a two-year period, but did not improve AVF use or decrease catheter use at first dialysis for incident (new) patients. Similarly, the introduction of a vascular access manager has improved the overall percentage of patients with an AVF in another US chronic dialysis unit4. A multifactorial initiative which included the introduction of a renal VAN significantly increased the proportion of patients starting dialysis with an AVF by improving the coordination of the surgical list1.

The results of a review of available evidence on the impact of renal vascular coordinators found that there was insufficient data to make firm conclusions about the impact of the role. Findings suggest an association between renal access coordinators and improved patient outcomes. These improved patient outcomes were apparent in an increase in incident and prevalent AVFs and a decrease in the incidence and prevalence of vascular catheters5.

In our service, with the dedicated renal VAN role overseeing the management of both new and established AVFs, there has been a renewed level of importance placed on vascular access. This paper highlights the vascular access outcomes for our dialysis service, emphasising the impact of the renal VAN position.

METHOD

A retrospective audit of vascular access outcomes was conducted at the end of 2014. Vascular access data has been collected since the inception of the renal VAN role and analysis allows benchmarking against historical dialysis service outcomes and national and international benchmarks where they exist. The Ethics Committee gave approval to conduct the audits as a quality activity.

At the end of 2014 there were 48 satellite haemodialysis patients, 130 hospital-based patients and 45 home haemodialysis patients. In addition, there were 42 patients at different stages of trajectory on the Predialysis Haemodialysis Pathway.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data which was entered onto an Excel spreadsheet and analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 226.

RESULTS

1. Fistula at first dialysis

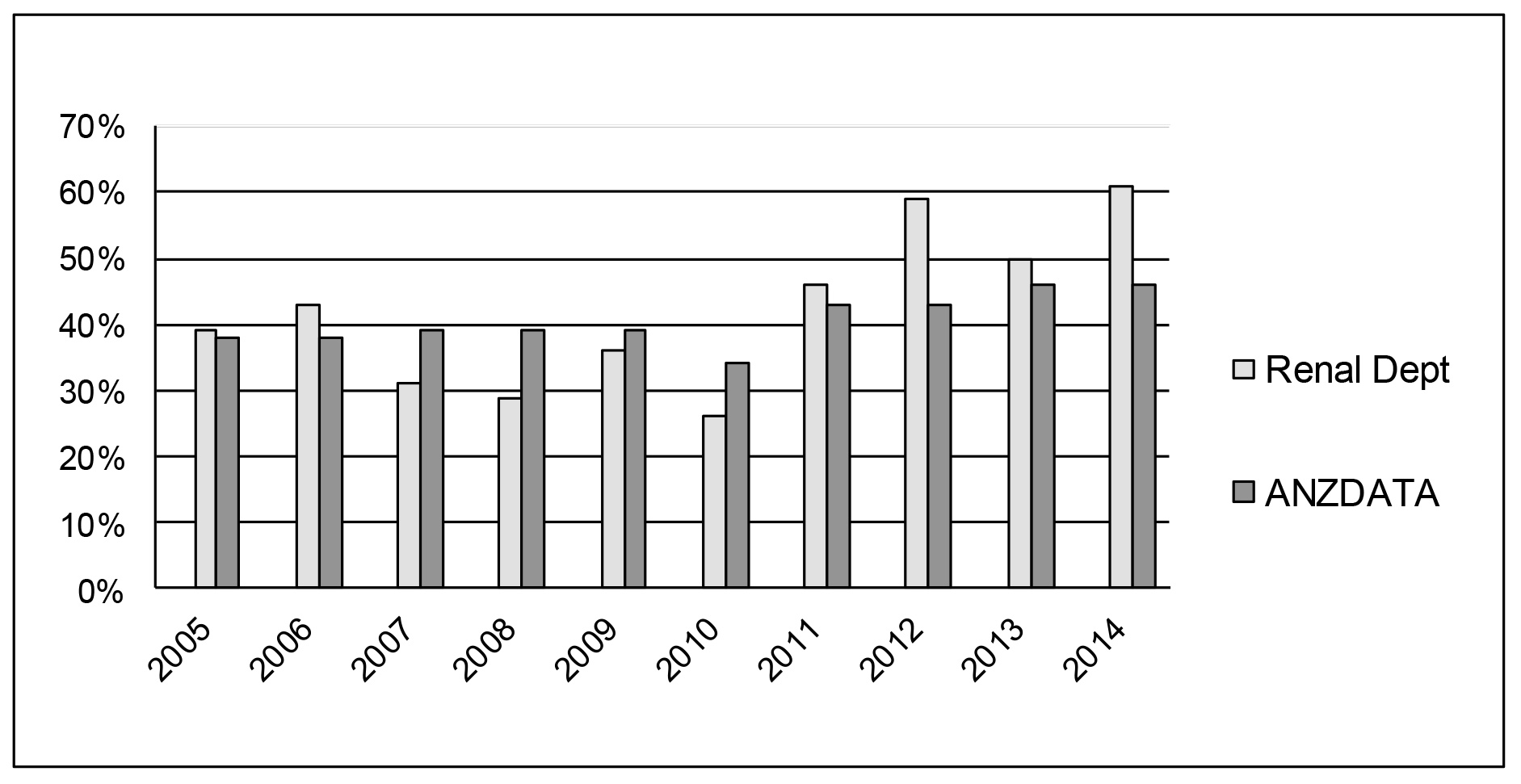

It is well recognised that all chronic haemodialysis patients should commence treatment with a functioning AVF or AVG7,8. The national average reported by the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) Registry for people commencing dialysis with a functioning access is 46%9. In comparison, at the end of 2014, 61% of renal service patients had a functioning AV access at first dialysis. Reasons why new patients did not have a functioning AV access were late referral to the service and sudden deterioration in renal function. For the patients who started dialysis (peritoneal and haemodialysis) in 2014, 19% were late referrals to the service, which is comparable to ANZDATA, which reports a national average of 18% in 201410. Overall, there has been a steady improvement in the percentage of patients commencing haemodialysis with a functioning fistula/graft since 2005 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Improvement in functioning AVF at dialysis commencement with a comparison to the national average (ANZDATA)

2. Use of vascular catheters for haemodialysis

Tunnelled cuffed catheters (TCC) are used to provide temporary access for both acute and chronic haemodialysis patients, including those with a primary AVF still to mature8. The use of vascular catheters for haemodialysis has been associated with substantially higher rates of mortality, infection-related complications, central venous stenosis, hospitalisations, and costs11.

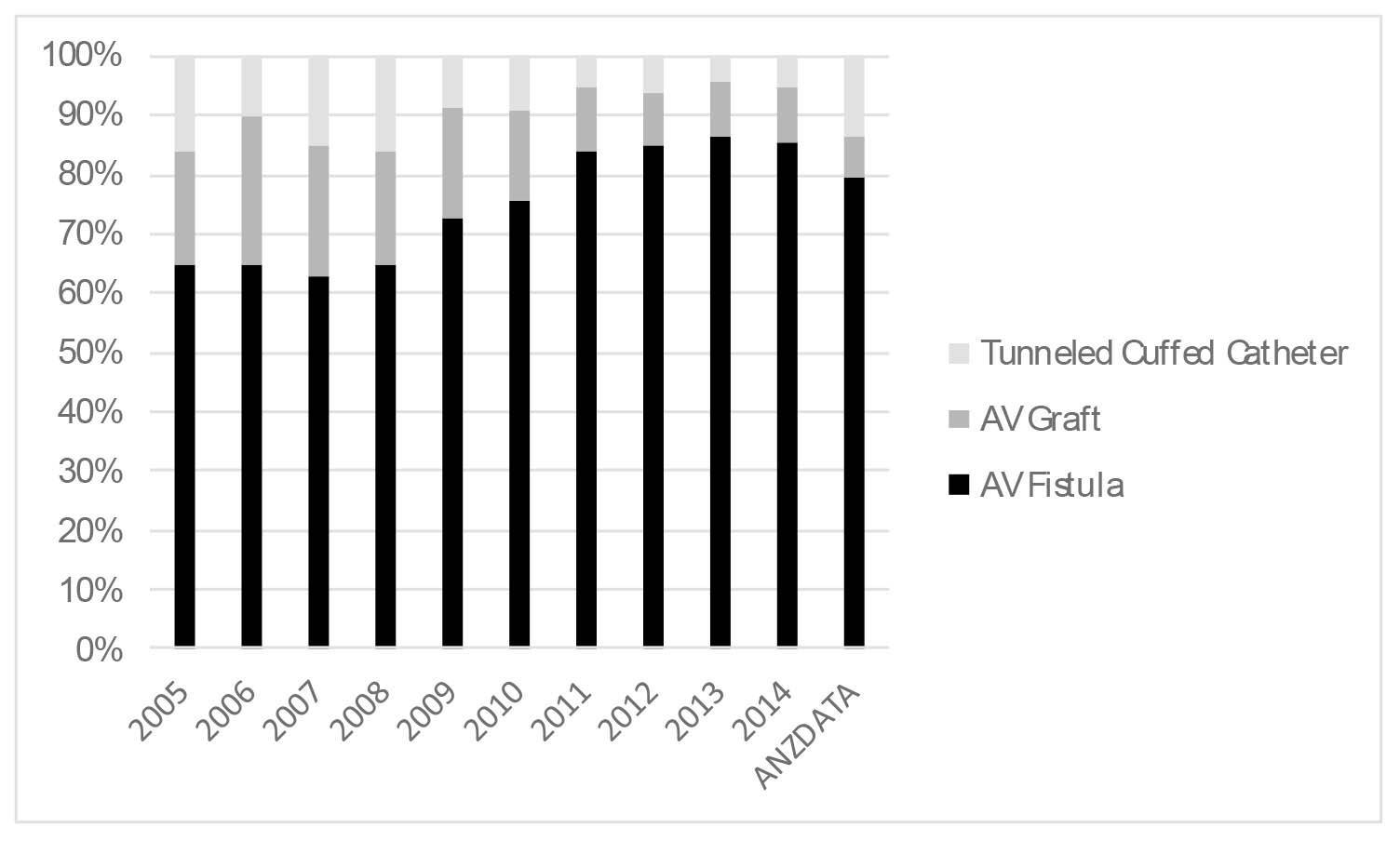

The American National Kidney Foundation Kidney Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF-K/DOQI) recommends that permanent vascular catheters should be used in <10% of patients8. Only 3% of the patients had a permanent vascular catheter at the end of 2014, which is substantially less than the NKF-K/DOQI benchmark. Prevalence data reveal that 92% of patients were using an AVF/AVG for haemodialysis, surpassing the national benchmark of 85%9 and NKF-K/DOQI of 40%8. There has been a steady downward trend in the use of TCCs in the dialysis service since 2005 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Type of access for prevalent patients 2005–2014 with comparison to national average (ANZDATA)

At the end of 2014, 39% of patients commenced haemodialysis with a TCC or non-tunnelled catheter, compared with the 2012 Australian benchmark of 57%12. There was a total of 8% usage of TCCs, which is less than the 2012 ANZDATA benchmark of 13%12.

3. Access thrombosis events

The NKF-K/DOQI Guidelines recommend a fistula thrombosis rate of <0.25 episodes/patient year at risk8. The fistula thrombosis rate for the dialysis service is 0.09 episodes/patient year. The recommended graft thrombosis rate is <0.5 episodes/patient year at risk8. The thrombosis rates for AVGs in our renal service surpass that set by NKF-K/DOQI at 0.84 episodes/patient year as our unit has fewer AVGs amongst its haemodialysis cohort.

4. Access infections

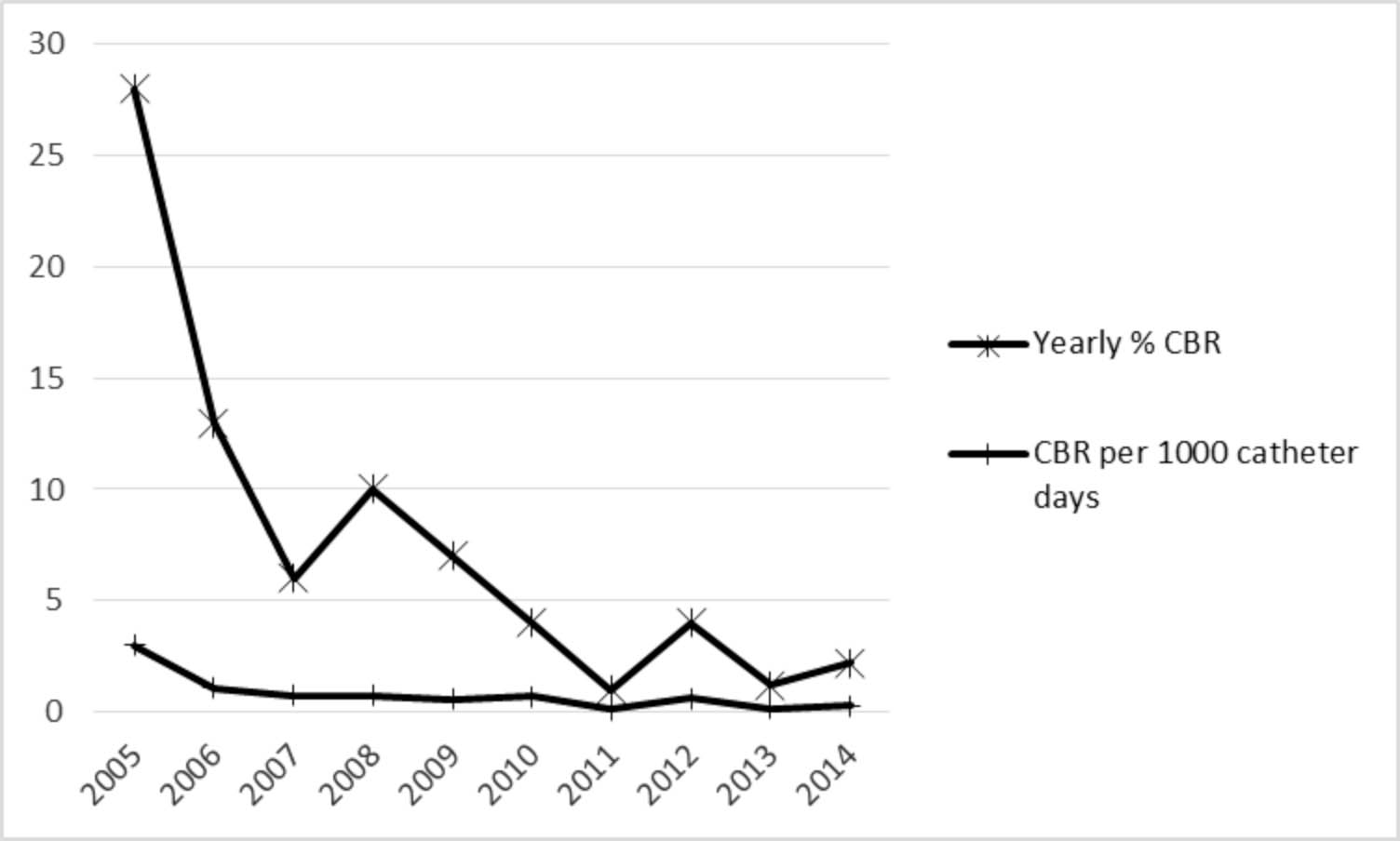

NKF-K/DOQI recommends a catheter-related bacteraemia (CRB) rate <1.5 episodes/1000 catheter days8. This benchmark for CRB was surpassed at 0.29 episodes/1000 catheter days in 2014, where there was one catheter-related infection for a total of 93 catheters in situ. There has been a downward trend in CBRs since 2005 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Catheter bacteraemia rates (CBR) 2005 to end 2014

NKF-K/DOQI recommends an infection rate <1% for AVFs and <10% for AVGs during the useful life of the access8. In 2014, there were no infections reported for AVFs or AVGs.

Discussion

The support from the renal VAN in the predialysis period has impacted on the improving results for functioning AV access at first dialysis. The renal VAN enacts the Predialysis Vascular Access Pathway by arranging duplex vascular mapping and allocating a vascular surgeon when the patient’s eGFR reaches 15mL/min/1.73m2. Once access surgery has been performed, the patient will be reviewed regularly in the renal VAN’s clinic until the access is mature and suitable for cannulation. Access maturation is monitored using a combination of physical assessment and bedside ultrasound. The patient is provided with essential education on access care and measures to encourage maturation. The nephrologist and vascular surgeon receive a comprehensive assessment including an ultrasound evaluation. Any irregularities such as failure to mature, stenosis or postoperative wound infection are referred on for action. The renal VAN liaises directly with the vascular surgeon if there are any concerns requiring urgent attention. The renal VAN clinic provides an opportunity for all patients to have an access review, at least 12-monthly.

The renal VAN’s efforts to improve AV access rates have led to a decrease in catheter use both for incident and prevalent patients. Contributing factors for reduced catheter usage are, firstly, the timely creation of access prior to first dialysis and, secondly, ongoing surveillance has led to the identification and correction of abnormalities early, resulting in less thrombosed AVF/AVGs and a reduced need for venous catheter insertions.

Educating haemodialysis staff members is a primary focus for the renal VAN as staff competence in access surveillance is critical to ensuring the timely identification of access dysfunction. Dialysis nurses complete a vascular access assessment tool monthly and when an access abnormality is identified nurses refer their concerns to the renal VAN for further review. The renal VAN conducts regular audits to ensure compliance with the vascular access assessment tool.

In regard to the infection-related access outcomes, the renal VAN has developed protocols to support the early detection and management of access infections. Close patient observation and vascular access assessment ensure that infections are identified early and treated. If access infection is confirmed, the renal VAN is responsible for identifying if there has been a breach in infection control measures and implementing actions to mitigate future risk. All access infections are reviewed by the renal department infection control committee on which there are representatives from the hospital infection control service.

There is little argument that good vascular access outcomes depend on a myriad of factors, including those related to the patient, such as his/her age, co-morbidities, mental and functional abilities, and vasculature. In addition, there are health care-related factors, such as access to renal and vascular services, adherence to protocols and guidelines, and dialysis staff skills and knowledge. There are also other factors beyond the control of the service, such as the late referral of patients. In essence, the role of the renal VAN is to align these variants in the best way possible to enhance outcomes for the AV access and, indeed, the patient. The major processes involve early and direct referral, monitoring and troubleshooting along the continuum of dialysis therapy and an emphasis on management based on best practice guidelines.

The renal VAN acts as an expert resource person and provides management for dialysis access on a continuum of care from the predialysis period, into the future and across a number of different access devices. The impact of the role is evidenced by the excellent outcomes and this success has been acknowledged through an upgrade to clinical nurse consultant level.

This paper has provided the experiences of one dialysis service, highlighting the impact that the introduction of the renal VAN position has made on vascular access outcomes. The introduction of a renal VAN with similar responsibilities would be a useful initiative in those units yet to adopt the role.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors acknowledge Amgen Australia Ltd for their initial unrestricted grant to fund the renal VAN position for two years.

Author(s)

* Yanella Martinez-Smith RN, MNursAP Renal Vascular Access Clinical Nurse Consultant, Renal Department, St George Hospital, Sydney, NSW, Australia Renal Care Centre, 9 South Street, Kogarah, NSW 2217, Australia Tel 02 9113 3818 Email Yanella.Martinez-Smith@health.nsw.gov.au Coralie Meek RN, MNsg Acting/Renal Vascular Access Clinical Nurse Consultant, Renal Department, St George Hospital, Sydney, NSW, Australia Email Coralie.meek@health.nsw.gov.au Shelley Tranter RN, DNsg Renal Clinical Nurse Consultant, Renal Department, St George Hospital, Sydney, NSW, Australia Honorary fellow, Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health, University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia Email Shelley.tranter@health.nsw.gov.au * Corresponding author

References

- Polkinghorne K, Seneviratne M & Kerr P. Effect of a vascular access nurse coordinator to reduce central venous catheter use in incident hemodialysis patients: A quality improvement report. Am J Kidney Dis 2009; 53(1):99–106.

- Dinwiddle L. Overview of the role of a vascular access nurse coordinator in the optimization of access care for patients requiring haemodialysis. Hong Kong Journal of Nephrology 2007; 9(2):99–103.

- Dwyer A, Shelton P, Brier M & Aronoff G. A vascular access coordinator improves the prevalent fistula rate. Semin Dial 2012; 25(2):239–43.

- Overbey A & Bell K. Impact of a nurse-driven vascular access management program on achieving and maintaining optimal vascular access for a chronic hemodialysis population. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2010; 17(2):209.

- Schoch M, Bennett P, Foilet R, Kent B & Au C. Renal access co-ordinators’ impact on haemodialysis patient outcomes and associated service delivery: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2014; 12(4):319–53.

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. 22.0 ed. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2013.

- Polkinghorne K, Chin G, MacGinley R, Owen A, Russell C, Talaulikar G et al. KHA-CARI Guideline: Vascular access — central venous catheters, arteriovenous fistulae and arteriovenous grafts. Nephrology 2013; 18:701–5.

- National Kidney Foundation. National Kidney Foundation KDOQI 2006 Vascular Access Guidelines 2006 [cited 2015, May 20]. Available from: http://www2.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/guideline_upHD_PD_VA/.

- ANZDATA Registry. ANZDATA Registry 37th Report, Chapter 4: Haemodialysis. Adelaide: Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, 2015.

- ANZDATA Registry. ANZDATA Registry 37th Report, Chapter 1: Incidence of end stage kidney disease. Adelaide: Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, 2015.

- Pisoni R, Zepel L, Port F & Robinson B. Trends in US vascular access use, patient preferences, and related practices: An update from the US DOPPS practice monitor with international comparisons. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 65(6):905–15.

- Polkinghorne K, Briggs N, Khanal N, Hurst K & Clayton P. ANZDATA Registry. 36th Report, Chapter 5: Haemodialysis. Adelaide: Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, 2013.