Volume 43 Number 1

Self-treatment of abscesses by persons who inject intravenous drugs: a community-based quality improvement inquiry

Janet L Kuhnke, Sandra Jack-Malik, Sandi Maxwell, Janet Bickerton, Christine Porter, Nancy Kuta-George

Keywords quality improvement, abscesses, self-care treatment, persons who inject drugs

For referencing Kuhnke JL et al. Self-treatment of abscesses by persons who inject intravenous drugs: a community-based quality improvement inquiry. WCET® Journal 2023;43(1):28-34

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.1.28-34

Submitted 8 August 2022

Accepted 19 October 2022

Abstract

Objective This study had two objectives. First, to understand and then describe the experiences of persons who inject drugs (PWID) and who use self-care treatment(s) to deal with resulting skin and tissue abscesses. Next, to understand and describe their journeys to and experiences with formal healthcare service provision.

Methods Semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten adults who have experience with abscesses, engage in self-care treatment(s), and utilise formal healthcare services in Nova Scotia, Canada.

Results Participants lived with abscesses and utilised various self-treatment strategies, including support from friends. Participants engaged in progressive self-care treatment(s) as the abscesses worsened. They reluctantly made use of formal healthcare services. Finally, participants discussed the importance of education. Moreover, they shared their thoughts in terms of how service provision could be improved.

Conclusions Participants described their lives, including their journeys to intravenous drug use. They also described the self-care treatments they used to heal resulting abscesses. They used these self-care treatments because of a reluctance to utilise formal healthcare services. From a quality improvement perspective, participants outlined suggestions for: 1) expanding hours of service at the community wound care clinic and the centre; 2) permitting pharmacists to include prescribing topical and oral antibiotics; 3) promoting abscess prevention education for clients and healthcare providers; and 4) promising practices for the provision of respectful care during emergency care visits.

Introduction

Persons who inject drugs (PWID) intravenously normally aim to inject a vein using a hypodermic needle and syringe1. When they miss the vein (missed hit) it may lead to skin and soft tissue injuries (SSTIs), cellulitis and/or abscess formation in varied anatomical sites2–11. An abscess contains a collection of pus in the dermis or sub-dermis and is characterised by pain, tenderness, redness, inflammation and infection12. Larney et al13 reported a lifetime prevalence (6–69%) of SSTIs and abscesses for PWID. These are most often caused by bacterial infections (Staphylococcus aureus, Methicillin-resistant S. aureus) and may lead to the development of deep vein thrombosis, osteomyelitis, septicaemia and endocarditis, thereby increasing morbidity and mortality14–16.

Abscesses require prompt attention to minimise resulting complications. This attention often includes emergency visits and hospitalisations17–19. However, PWID avoid seeking formal healthcare services (e.g., community clinics, physician offices, emergency care teams) for a variety of reasons and therefore they often engage in self-care treatment(s)20–22. Reasons for their reluctance to utilise formal healthcare services include experiencing lengthy clinic and emergency wait times, being judged and feeling discriminated against by care providers and the resulting experience of being othered23, and being asked questions about their drug use24,25. In addition, PWID may delay accessing formal healthcare services due to a fear of drug withdrawal and inadequate pain management26. Reluctance to seek out and utilise formal healthcare services can result in self-care treatment(s), including attempts to lance and drain abscesses20–22.

Our goal was to understand and describe the experiences of PWID and who use self-care treatment(s) and to understand and describe their journeys to and experiences with formal healthcare service provision. We also wanted to listen to and record their recommendations for the improvement of services. This was a significant goal of the research because it has the potential to prevent and decrease the number of abscesses resulting in hospital visits and admissions and, ultimately, to decrease the number of related deaths and suffering.

Frameworks guiding this study

Informed by the harm reduction focus of Nova Scotia’s Opioid use and overdose framework27 and utilising a quality improvement approach28, we sought to engage in semi-structured interviews with PWID to understand their experiences and their recommendations for how to improve community-based abscess care. Freire guided this study and our approach when he wrote “... human existence cannot be silent, nor can it be nourished by false words, but only by true words, with which men and women transform the world”29(p88). Knowing much of the suffering and resulting deaths are preventable, our goal was to listen carefully and respectfully to participants, such that their voices become part of the solution.

Methods

The study was conducted in partnership with a harm reduction centre (the centre) and university researchers. Qualitative data were collected from PWID using semi-structured interviews30,31. Several visits to the centre occurred to develop trust with the centre’s team and potential participants32,33. The centre offers primary healthcare services to populations including those living with substance use disorder(s), those experiencing homelessness, and sex workers34,24. Funding for the study was provided by a Cape Breton University Research Dissemination Grant.

Participants

Participants included ten adults (PWID and 18+ years) who experienced abscess(es), engaged in self-care treatment(s), utilised formal healthcare services, and expressed an interest in the interview at the time of data collection.

Data collection

Adults accessing the centre were approached by the centre’s team to see if they wanted to participate. Interviews were conducted in a quiet space of the participants’ choice and snacks were offered. Interviews of 45–60 minutes using a semi-structured script occurred. After four were completed, we listened to the interviews (triangulation) to ensure the questions were respectfully resulting in useful data28. The interview questions explored participants’ knowledge of abscess risk, characteristics of an abscess, education of safe injection practices, including skin hygiene, and experiences when utilising healthcare services. We also invited participants to describe recommendations for improvement to the provision of abscess care. We regularly communicated the study progress with the team. Throughout the study we adhered to pandemic guidance35.

Research ethics

Approval for the study was granted by Cape Breton University. Adults who met the inclusion criteria received, discussed and were invited to ask and have answered their questions. A letter of information was provided and written informed consent was obtained. Data collected included gender, age, age of first abscess, products, medications used to self-treat, and when and to whom they reached out for formal healthcare. A CA$25 gift card was given to each participant after the interview was complete.

Data analysis

Data were recorded, secured, and transcribed verbatim30–32. We read and re-read the transcripts, seeking patterns and themes. From the analysis, four themes emerged: 1) lack of experiential knowledge; 2) progression of self-treatment strategies; 3) utilisation of formal healthcare; 4) education matters; do not rush. We discussed the themes to ensure we captured the essence of the participants’ stories. Findings are presented in a narrative format with participants’ quotes embedded; identifying characteristics were removed and comments were edited for clarity.

Findings

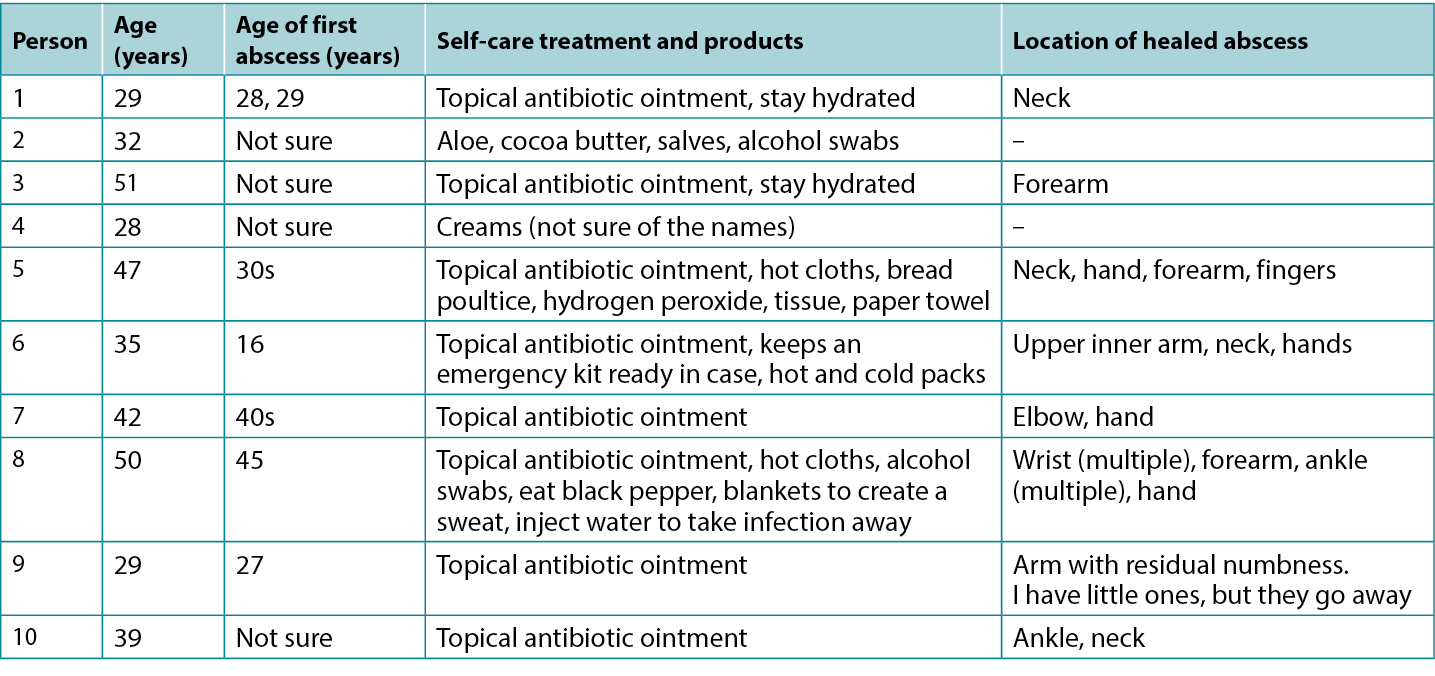

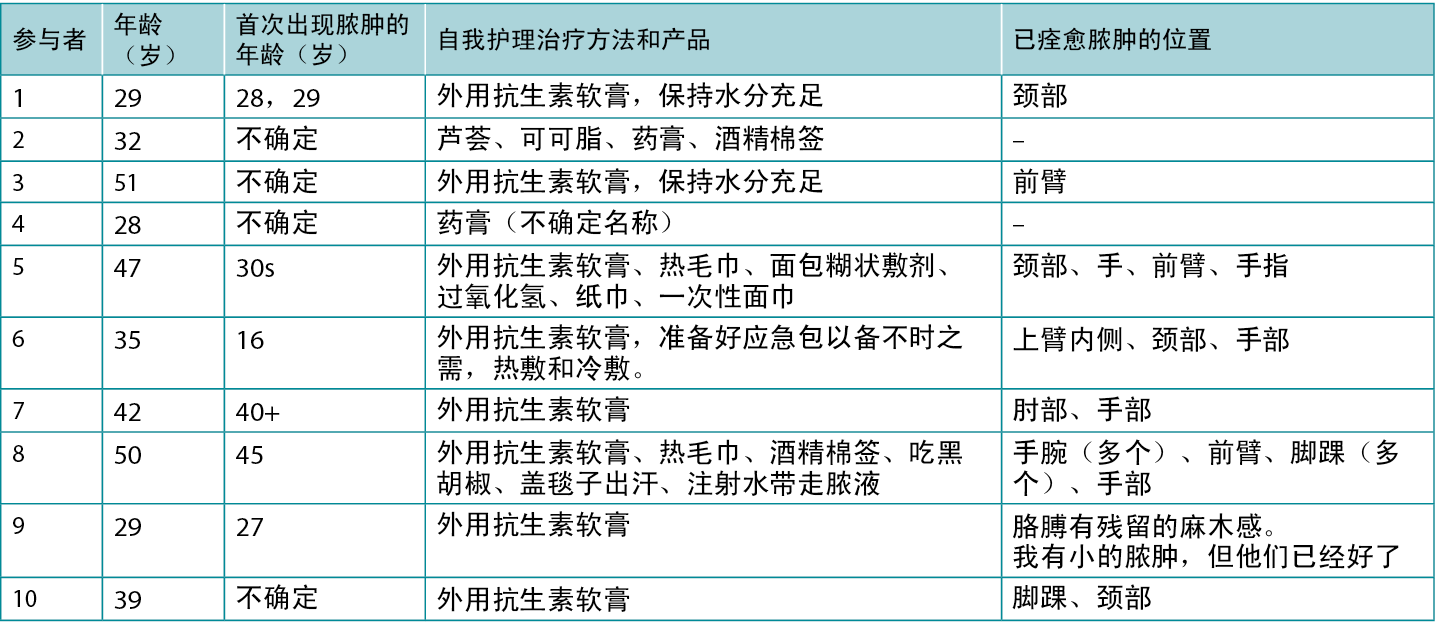

Ten participants, four women and six men, who experienced one or more abscess(es) participated (mean age 38.5 years; range 29–51 years). Five participants were unsure of the date of their first abscess, two identified a range of dates, and three knew the specific date as they included a critical hospital event. One participant had an active skin infection and seven showed the locations of one or more healed abscess sites (Table 1).

Table 1. Participants’ Description of self-care treatment(s)

Theme 1: lack of experiential knowledge

When first injecting drugs, participants described limited knowledge of skin infections, cellulitis and abscess(es). One participant shared “I thought I was the perfect user, I never thought I would get an abscess”. Another stated “I didn’t know what the redness was – the cellulitis; a nurse taught me. I did not know it had become an abscess as I still played sports”. Another participant knew the risks and thought abscesses were inevitable – “I knew you could get them wherever you inject!” Coming to understand the risks varied for participants:

The abscess, was so, so painful. I could not sleep, I was scared; I did not know what it was. My hand was blowing up! I could not work. It was not until someone told me my hand was infected that I panicked. I ended up going to the hospital.

The pill or dirt in the cocaine or whatever was added will build up in your system and cause an abscess, I learned this over time. The dirty needle and water made it worse. Your body pushes the foreign substance out, you have headaches, your tired, all your blood is going to the wound to try to heal it. The area is hot. It feels like it is dragging you toward death. I thought I was dying.

The pain was extreme and unbearable. I hid the wounds. I used to miss the vein if I was shaking and rushing to inject. Some pills like Ritalin, hydromorphone, Dilaudid, and Effexor were worse than others. I did not get them from cocaine. I had abscesses in my hands, wrists, ankles. My teeth got abscessed due to the infections, I lost all my teeth; I have dentures.

Theme 2: progression of self-treatment strategies

Participants described engaging in abscess self-care treatment(s) and identified additional steps taken if the abscess worsened. They also described extreme pain when pressing the abscess(es) with their fingers to pop or squeeze the abscess, or when using a pen knife, surgical blades or a big needle to lance, drain or draw out the infection from the infected area(s). These activities may take place in a kitchen, bathroom (e.g., work, public, home), or bedroom alone or with a friend. One participant described his self-care:

I use soap, water, or what I can find to clean it. I try to keep it covered. I use clean needles or blades to lance it myself. If it does not fill back up with stuff, I leave it alone. I have stuffed bread in them before, the bread turns green and takes the infection out. It helps. I have had quite a few, the last one was on my finger. It is fine now, but it was discoloured. These were not the nasty ones. I have had to clean abscesses on my hands and legs, but they were not so bad that I had to go to the hospital. When I have them bad, they physically drain me, literally like I am dragging around, exhausted.

Participants explained that self-care treatment(s) changed as the abscess worsened. For example:

If it was infected, I would get half a prescription of antibiotics from someone else. I drank water to flush out the infection. I kept a face cloth on top of the abscess to collect the drainage. It is important to clean your skin first with alcohol swabs to reduce the bacteria. I used antibiotic ointment on small abscesses unless the redness did not go away. I got free antibiotic pills, some people charge each other, but I do not, that’s mean. Sometimes I used a hot facecloth on the area. I drain the abscesses myself, I use aloe, a topical antibiotic, and if it gets worse, I try to get an oral antibiotic from a friend at no charge, it is not good to charge money you know, you could die. I try to get a three-day supply. At first, I did not know what to do. I started treating the abscess with hot water, then cold, then both. I bought a heat bag to put on it to draw out the infection. I told the nurses at the centre, and they drew a line around it. These are my six, three, and two-inch scars. See the length? They were bad ones.

Friends help me

One participant said that, when they have an abscess, they may tell a partner or friend. Participants stated partners or loyal friends would do the following – help incise and drain an abscess in any location, find topical and oral antibiotics and not charge them, and locate wound supplies. Friends would help organise or drive them to an appointment (e.g., doctor, nurse, nurse practitioner, clinic, emergency department). Participants shared the following:

There is a code on the street you know, abscesses can kill you, so you help each other. My friend had an abscess, I cleaned it for him with alcohol, it burned, it helped. If I need help with my abscesses he would help me too, we would, just get, like you know, a topical antibiotic from, like, from like, wherever… [pauses & smiles]. My friends will help if I ask. But I usually treat the abscess myself. With my first abscess I got a hot fever, so I wrapped myself in four blankets. Ate black pepper. I injected water to take it away, it does not last long. My blood went septic with a big abscess, my friend took me for care.

Increasing sense of urgency

Four participants described urgency related to a worsening abscess:

I would only wait a day before getting care from the nurses. I would not wait longer. I do not rely on anyone else to know how bad my skin is, that is my job. Abscesses can kill you. I get care right away. I got care for my wrist abscess from the community nursing team. I am prepared, I keep a kit ready for abscesses in case… people die. My last one in my elbow was so big I could fit a whole roll of gauze in the hole. The home care nurses helped me. I know I can come to the centre for care, they are amazing, I rely on them.

Another shared:

Supplies for abscesses are not easy to find, the pharmacies are expensive, I get what I need at no cost, this is serious stuff. It should be easier to get basic antibiotic prescriptions. Why is it so hard to get oral antibiotics? Why can’t a pharmacist order it? Why can’t nurses do this? I could die.

From these comments we began to understand self-care as part of a continuum of care and we understood PWID quickly experience how fast abscesses can become serious and the resulting need to seek out formal healthcare providers.

Theme 3: utilisation of formal healthcare

Participants preferred to receive abscess care at the community nursing wound clinic or the centre where they were respected. Participants expressed concern when interacting with emergency care teams (the three provinces mentioned were Alberta, Ontario and Nova Scotia) because it regularly evoked feelings of shame and being judged when asked assessment questions and planning abscess care (e.g., returning to emergency, hospitalisation). Their reluctance to access or remain in care once assessed was related to prior experiences. Participants shared:

It would take a lot for me to ask for help! I would have to be really sick to ask for help from the hospital! We really need a safe injection site, then the abscesses would not be happening. I would cut open my abscess myself ahead of going to the hospital. I would get oral antibiotics first from someone, then if it got worse, I would go to the hospital. It would be my last stop. There should be a priority for abscess care at the hospital. Why can’t I get care from a pharmacy or pharmacist? If you need intravenous antibiotics four times a day, and you can hardly make up your mind to plan to go back to the hospital… it is not a surprise that I did not go back. Many people do not have cars or parking money, so we do not go back! If you miss a dose, it is worse, as you must be readmitted and wait, wait, and wait.

Respectful care

Participants shared experiences of receiving respectful care and negotiating with the team.

My abscess was so infected I went for care. They were good to me. I needed care, I went to emergency, they treated me well. I was ashamed to go, I just knew I had to get there. I went alone. They let me have a cigarette, so I stayed.

I did not want to go to the hospital. People were initially judgemental. They asked me about being an intravenous drug user, then they backed up in the room. I did not like this. Yet, they did drain my hand. The care was okay… actually, it was good when the walls come down and you know you are accepted, care was good for me.

The hospital was okay. I just focused on the abscess. They treated me good, they were fair. The abscess smelled so bad when they cut it open. I have not experienced stigma at the hospital. They were good to me; I waited a few hours and it was okay. Everyone else was waiting for care too. You have to be kind and put out kindness, then they will be kind to you.

I went to emergency and the doctors and nurses treated me well. I went back twice a day, for three days and then I took a week of oral antibiotics. It saved my life, from the sepsis. I could have died (tears up). I was treated well in emergency, though I do hear negative stories. I was really scared, yet, I got good care from the team. I would tell people to go to emergency, after I treat the area myself.

I would never lance my abscess. I am too afraid. I got good care in ambulatory care, they used iodine and lots of packing, I think I got the good nurses. They were kind to me, that matters. I do not want to be looked down on by anyone as that upsets me.

I went for care, they were good to me. When I need antibiotics, I go and get them. I do not get them from people on the street. I do not want to take a chance on my life. People will sell you anything and call it an antibiotic. I know I get embarrassed when I ask for help, but that is me. I needed care.

During the pandemic, I received a virtual wound assessment and then I felt better. They taught me to mark the edges of the redness and told me that if it gets redder to go to emergency. Well, I went to emergency and got good care. My emergency visit was better as I did not go alone, having a support person with me was a huge help – then I did not leave.

We understand this theme as a counter to the narrative of avoiding hospital care. PWID understand there are times when hospital care is necessary. In addition, counter to stories that circulate among PWID, hospital care may be experienced as respectful.

Theme 4: education matters; do not rush

Participants expressed the importance of education related to the safe injection of drugs and skin hygiene. Each participant reflected on the person(s) who initially taught them how to inject drugs and practise skin hygiene. They described the risks of a missed hit, when they inadvertently injected into the fatty, subcutaneous or intramuscular layers, or when the drugs leaked into the skin. One participant learned how to inject from an internet video. Another learned from a former partner who taught him to use new filters and needles:

She taught me about cotton fever as I was doing it wrong. As well, I was using little veins with a big needle and got an abscess. No one taught me, I learned from other people using. I have only had one abscess from missing, and it made my upper arm and breast area swell. I could not sleep and could not use my arm and hand. Someone could show you a bad, bad, bad technique. You must see blood, then you push it in, the correct way matters. Education sessions should remind people to not rush, if they do not see blood, do not inject. People are rushing to inject, do not rush, no blood – no injecting, then you will not miss. Also, if you are not feeling good and you are relying on someone else to inject you, that is not good as the person may rush and miss.

Four participants expressed they learned how to safely inject from nurses at the centre. They readily described the importance of using clean equipment, cookers, needles and cleansing the skin with alcohol swabs. Three stated education classes should include correct injecting techniques, discussions of the risk of missing, and pictures of SSTIs and abscesses to compare their abscess to in order to determine the level of seriousness.

Discussion

This small quality improvement study28 was conducted at a harm reduction centre in partnership with university researchers. Purposeful recruiting from the centre’s clientele may have influenced findings because of the centre’s mandate32. Interview data revealed thick descriptions30,31. Findings demonstrate that PWID experience a learning curve related to injection and abscesses. Participants most often begin with self-care and utilise formal healthcare services when they experience urgency as the wound worsens. Participants’ answers demonstrate understanding of the risks, a desire to heal from and or prevent abscesses, and the human need to be treated respectfully. From a quality improvement perspective, they outlined improvements including suggestions for: 1) expanding hours of service at the community wound care clinic and the centre; 2) permitting pharmacists to include prescribing topical and oral antibiotics; 3) promoting abscess prevention education for clients and healthcare providers; and 4) promising practices for the provision of respectful care during emergency care visits.

Dechman and colleagues discussed the complex and unique journeys PWID experience24. PWID aim to inject drug(s) intravenously and do not plan to miss or inadvertently inject into the tissues (subcutaneous or intramuscular)2. Our findings showed participants, when first injecting, do not always know about SSTIs and abscess formation from bacterial or viral sources. However, over time they learn the seriousness of missing the vein (e.g., peripheral, femoral, neck). They also learn the risk associated with sharing or re-using equipment, the relationship to the development of collapsed and sclerosed veins, cellulitis, abscess(es), and serious infections. Participants were able to consistently describe early and late signs of abscesses21,36. Moreover, once participants knew they had an abscess, they began with self-care interventions. If improvement was not experienced, they accessed formal healthcare. These findings demonstrate PWID are knowledgeable, begin with self-care and when required will seek out formal care, regardless of the reticence. We understand this process as a meaningful continuum of care. They also described the importance of maintaining and growing the wound care nurse role in the Ally Centre and with the community nursing teams.

Need for acute care and resulting reticence

For participants there was reluctance to seek formal healthcare though they understand abscess(es) lead to sepsis, hospitalisation and death24. Participants want to be treated respectfully when engaging in acute care. Reluctance was related to perceptions of formal healthcare staff and fears of being disrespected. Participants want to be treated respectfully throughout the entire encounter. They also required access to reliable transportation and parking fees. Waiting at the hospital was not preferred, though having a friend and being able to go outside for a cigarette eased the waiting time. Participants recommend healthcare professionals receive education related to the compassionate and respectful care of PWID and living with skin and wound complications33.

Antibiotic stewardship

Antibiotic stewardship for PWID is of concern and challenging to address37,38. Participants discussed the need for pharmacists to be involved in prescribing antibiotics. Topical and oral antibiotics may be consumed as prescribed, shared with another person whose abscess is judged to be worse, given or sold to another, or kept secure for future use20–22. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends consistent education related to correct use of antibiotics39. For PWID this translates to accessible education materials (e.g., online, printed and workshops)21 and consistent and easy access to new equipment used to prepare and inject a drug(s)37,40.

Harvey and colleagues40 surveyed healthcare professionals’ knowledge about the prevention of infection in PWID. Professionals disclosed they received little to no education on harm reduction, were not comfortable counselling PWID, and lacked knowledge on where to refer PWID for education or supplies. To reduce PWID morbidity and mortality, Harvey et al developed the “Six moments of infection prevention in injection drug use provider educational tool”40(p.1). The toolkit emphasises a broad framework focused on infection prevention for PWID.

Participants in this study repeatedly shared they were willing to learn, and they wanted to be safe to avoid complications. They requested development of videos and a phone application (app) depicting mild cellulitis to complex abscesses. There are risks associated with the latter request, as solely relying on wound images as a diagnostic tool for mild, progressing and serious infections is not recommended36.

Conclusion

In this study, participants became knowledgeable about SSTIs and abscess development. Though they were aware of the risks of (mortality, morbidity), they remained reluctant to access formal healthcare. More research is needed to fully understand the maintenance and expanding of wound care services, including the role of pharmacists in the community. In addition, education for PWID was a consistent message, and PWID want consistent credible materials from which to learn. Finally, PWID want to know they will be respected when accessing healthcare services. Our experience of the interviews left us wondering how best to describe the humility, intelligence and kindness of the participants. They were thoughtful, and wanted to improve the experience for themselves and others.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants for sharing their stories and for their thoughtful recommendations.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

静脉注射吸毒者的脓肿自我治疗:基于社区的质量改进调查

Janet L Kuhnke, Sandra Jack-Malik, Sandi Maxwell, Janet Bickerton, Christine Porter, Nancy Kuta-George

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.1.28-34

摘要

目的 本研究有两个目的。首先,了解并描述注射吸毒者(PWID)使用自我护理治疗来处理由此产生的皮肤和组织脓肿的经历。其次,了解并描述他们获得正规医疗服务的过程和经历。

方法 在加拿大新斯科舍省,对10名有脓肿经历、进行了自我护理治疗和使用正规医疗服务的成年人进行了半结构式访谈。

结果 参与者患有脓肿,并采用各种自我治疗策略,包括来自朋友的支持。当脓肿恶化时,参与者进行了渐进式自我护理治疗。他们不情愿地使用了正规的医疗服务。最后,参与者讨论了教育的重要性。此外,他们还就如何改进医疗服务的提供分享了自己的想法。

结论 参与者描述了他们的生活,包括静脉注射毒品的经历。他们还描述了他们用来治愈由此产生的脓肿的自我护理方法。他们之所以使用这些自我护理的治疗方法,是因为他们不愿意使用正规的医疗服务。从质量改进的角度,参与者提出了以下建议:1)延长社区伤口护理诊所和中心的服务时间;2)允许药剂师开具外用和口服抗生素处方;3)促进对客户和医疗服务提供者的脓肿预防教育;以及4)希望在急诊看病的过程中能够受到尊重。

引言

静脉注射吸毒者(PWID)通常使用皮下注射针和注射器进行静脉注射1。当他们未扎进静脉(漏针),可能会导致皮肤软组织损伤(SSTI)、蜂窝组织炎和/或在不同解剖部位形成脓肿2-11。脓肿是真皮层或真皮下的脓液聚集,其特点是疼痛、压痛、发红、炎症和感染12。 Larney等人13报告了注射吸毒者SSTI和脓肿的终生患病率(6%-69%)。SSTI和脓肿最常由细菌感染(金黄色葡萄球菌、耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌)引起,并可能导致深静脉血栓形成、骨髓炎、败血症和心内膜炎的发生,从而増加发病率和死亡率14-16。

脓肿需要及时关注,从而尽量减少由此引起的并发症。这种关注往往包括急诊就诊和住院治疗17-19。然而,出于各种原因,PWID会避免寻求正规的医疗服务(如社区诊所、医生办公室、急救团队),因此他们经常进行自我护理治疗20-22。他们不愿使用正规医疗服务的原因包括:在诊所和急诊的等待时间过长,被医疗服务提供者评头论足和感觉受到其歧视,并由此受到排斥23,以及被问及有关吸毒的问题24,25。此外,由于担心药物戒断和疼痛管理不充分,PWID可能会推迟寻求正规的医疗服务26。不愿意寻求和使用正规的医疗服务可能致使其进行自我护理治疗,包括尝试穿刺引流脓肿20-22。

我们的目标是了解和描述PWID使用自我护理治疗的经历,并了解和描述他们获得正规医疗服务的过程和经历。我们还希望听取并记录他们对改进医疗服务的建议。这是本研究的一个重要目标,因为这有可能帮助预防脓肿和减少需要到医院就诊和入院治疗的脓肿数量,并最终减少相关的死亡和痛苦。

本研究的指导框架

根据新斯科舍省的阿片类药物使用和过量使用框架27的减害重点,并利用质量改进方法28,我们试图与PWID进行半结构式访谈,以了解他们的经历以及他们对如何改善社区脓肿护理的建议。弗莱雷(Freire)为本研究和我们的研究方法指引了方向,他写道:“ÅcÅc人类不可能在沉默中生存,滋养人类不可能靠错误的词,而只能靠真实的词。男男女女都用真实的词来改造世界”29(P88)。我们知道许多痛苦和由此导致的死亡是可以避免的,我们的目标是以尊重的态度认真倾听参与者的意见,使他们的声音成为解决方案的一部分。

方法

本研究与一个减少危害中心(该中心)和大学研究人员合作开展。使用半结构式访谈从PWID中收集定性数据30,31。为了与该中心的团队和潜在参与者建立相互信任,我们对该中心进行了几次访问32,33。该中心为包括物质使用障碍者、无家可归者和性工作者在内的人群提供初级医疗保健服务34,24。本研究的资金由布雷顿角大学研究传播补助金提供。

参与者

参与者包括10名成年人(PWID,18岁以上),他们经历过脓肿,进行了自我护理治疗,使用了正规医疗服务,并且在数据收集时表示对访谈感兴趣。

数据收集

该中心的团队与进入中心的成年人进行了接触,看他们是否愿意参加研究。访谈在参与者选择的安静空间进行,并提供点心。使用半结构化脚本进行了45-60分钟的访谈。在完成四次访谈后,我们听取了访谈内容(三角互证),以确保问题均可以获得有用的数据28。访谈问题探讨了参与者对脓肿风险的了解、脓肿的特点、安全注射操作的教育(包括皮肤卫生),以及使用医疗服务的经历。我们还邀请参与者描述对脓肿护理服务的改进建议。我们定期与团队沟通研究进展。在整个研究过程中,我们遵循了疫情指南35。

研究伦理

研究得到了布雷顿角大学的批准。符合纳入标准的成年人收到问题、进行了讨论并被邀请提出问题并得到回答。提供了一份信息函,并获得了书面知情同意书。收集的数据包括性别、年龄、首次发生脓肿的年龄、用于自我治疗的产品、药物,以及他们何时和向谁寻求正规医疗服务。访谈结束后,每位参与者都得到了一张25加拿大元的礼品卡。

数据分析

我们对数据进行了记录、保护和逐字转录30-32。我们反复阅读记录稿,寻找模式和主题。通过分析,得出四个主题:1)缺乏经验知识;2)自我治疗策略的进展;3)使用正规医疗服务;4)教育很重要;请勿操之过急。我们就这些主题开展了讨论,以确保抓住参与者故事的精髓。研究结果以叙述的形式呈现,并插入了参与者的引述;为了使内容清晰,删除了识别特征,并对评论进行了编辑。

结果

参与者共10名,其中4名女性,6名男性,均经历过一次或多次脓肿(平均年龄38.5岁;年龄范围29-51岁)。5名参与者不确定他们第一次出现脓肿的日期,2名参与者确定了日期范围,3名参与者因为情况严重曾到医院就诊,因此知道具体日期。1名参与者曾出现活动性皮肤感染,7名参与者展示了一个或多个脓肿愈合部位的位置(表1)。

表1.参与者对自我护理治疗的描述

主题1:缺乏经验知识

参与者描述了第一次注射毒品时,对皮肤感染、蜂窝组织炎和脓肿的了解有限。一位参与者分享说:“我认为我是完美的吸毒者,我从未想过我会长脓肿。”另一位参与者说:“我不知道发红是什么情况Å\Å\是蜂窝组织炎,一位护士告诉我的。我不知道它已经变成了脓肿,因为我仍然在进行体育运动。”另一位参与者知道风险,但认为脓肿是无法避免的Å\Å\“我知道无论在哪里注射都会长脓肿!”在了解风险方面,参与者的情况各不相同:

脓肿非常非常疼。我睡不着,感觉很害怕;我不知道那是什么。我的手快炸了!我无法工作。直到有人告诉我我的手被感染了,我才慌了神。最终我还是去了医院。

药片或可卡因中的污物或添加的任何东西都会在体内积聚,导致脓肿,这是我长期以来的经验。针头和水不卫生使情况变得更糟。身体会把这些异物排出体外,自己会感到头痛、疲倦,所有的血液都流向伤口,试图将其愈合。伤口周围很热。感觉就像被它拖着走向死亡。我以为我快死了。

疼痛到达了极点,难以忍受。我把伤口藏了起来。如果在颤抖时急于注射,就经常无法扎进静脉。利他林、氢吗啡酮、Dilaudid和Effexor等一些药片,更害人。我的脓肿不是因为可卡因。我的手、手腕、脚踝都长过脓肿。我的牙齿因为感染而发生脓肿,我的牙齿全部掉光了,所以装了假牙。

主题2:自我治疗策略的进展

参与者描述了脓肿自我护理治疗的情况,并指出了在脓肿恶化时采取的额外措施。他们还描述了通过手指按压来挤破或挤出脓肿时的极度疼痛,或使用笔刀、手术刀片或大针头将感染区刺破、引流或抽出脓液时的极度疼痛。这些活动可能在厨房、浴室(如工作场所、公共场所、家中)或卧室单独进行,或与朋友一起进行。一位参与者描述了他的自我护理:

我用肥皂、水或我能找到的任何东西来进行清洁。我会尽量把它盖住。我自己用干净的针头或刀片来把它刺破。如果里面没有重新充满脓液,我就不去管它。我以前在里面塞过面包,面包会变绿,并把脓液带出来。这样做有所帮助。我长过不少脓肿,最近一次是在我的手指上。现在已经好了,但皮肤变色了。这些还不是最讨厌的。我还不得不清理手上和腿上的脓肿,但它们没有严重到必须去医院的程度。当脓肿恶化,它们会使身体疲惫不堪,我感觉就像在拖着身体到处走,筋疲力尽。

参与者解释说,随着脓肿恶化,自我护理治疗也发生了变化。例如:

如果感染了,我会从别人那里弄来一半处方剂量的抗生素。我喝水来清除感染。我在脓肿上放了一块面巾,用来收集引流液。先用酒精棉签清洁皮肤很重要,这样可以减少细菌。我在小脓肿上涂抹抗生素软膏,除非红肿消失不了。我有免费的抗生素药片,有些人会互相收费,但我不会,这很卑鄙。有时我会用热面巾擦拭脓肿区域。我自己给脓肿引流,也使用芦荟,一种外用抗生素。如果情况恶化,我会试着从朋友那里获得免费的口服抗生素。你懂的,收钱不好,毕竟是要命的事情。我会试图得到三天的药量。起初,我不知道该怎么做,就开始用热水治疗脓肿,然后用冷水,后来两种都用。我买了一个发热包放在上面,以排出脓液。我告诉了中心的护士,他们在脓肿周围画了一条线。这些是我六英寸、三英寸和两英寸的疤痕。看到他们的长度了吗?这些是都是相当严重的。

朋友给予我帮助

一名参与者说,当他们有脓肿时,他们可能会告诉伴侣或朋友。参与者表示,其伴侣或仗义的朋友会做以下事情Å\Å\帮助切开任何位置的脓肿并引流,找来外用和口服抗生素但并不收费,并找到伤口用品。朋友会帮忙安排或开车送他们去看病(例如,医生、护士、执业护师、诊所、急诊科)。参与者分享了以下内容:

这条街上有一个守则,脓肿可能会要了你的命,所以大家要互相帮助。我的朋友长了脓肿,我用酒精为他清洗,伤口很烫,很有效。如果我需要帮助处理我的脓肿,他也会帮助我,我们会,就像你知道的那样,从任何地方,获得外用抗生素ÅcÅc[停顿和微笑]。如果我开口,我的朋友们会帮忙的。但我通常自己治疗脓肿。第一次长脓肿时,我发烧了,所以我用四条毯子把自己裹起来,还吃了黒胡椒。我注射了水来排出脓肿,但并没有持续很久。我的血液化脓了,有一个大脓包,于是我的朋友带我去看医生。

日益増强的紧迫感

四名参与者描述了脓肿恶化带来的紧迫感:

我只会等一天,然后就找护士进行治疗。我不想再等了。我不指望别人知道我的皮肤有多糟糕,这是我自己的事情。脓肿会要了你的命。我要马上得到治疗。我手腕的脓肿得到了社区护理小组的治疗。我做好了准备,我准备了一个脓肿急救箱,以防有人死亡。我手肘上最新长的一个脓肿有一个大洞,大得可以放进一整卷纱布。家庭护理的护士们帮助了我。我知道我可以到中心来寻求治疗,他们很了不起,我非常依赖他们。

另一名参与者说:

脓肿的治疗用品不好找。药店很贵,我要的东西不花钱就能买到,这可是正经事。获得基本的抗生素处方应该变得更容易一些。为什么得到口服抗生素这么难?为什么药剂师不能订购抗生素?为什么护士们不能这样做?我可能会死的。

从这些评论中,我们开始了解到自我护理是连续护理的一部分,我们了解到PWID会迅速感受到脓肿变严重的速度有多快,并因此产生到正规医疗机构就诊的需要。

主题3:使用正规医疗服务

参与者更愿意在社区伤口护理诊所或他们受到尊重的中心接受脓肿护理。参与者表示在与急诊护理团队(提到的三个省份是阿尔伯塔省、安大略省和新斯科舍省)互动时会有顾虑,因为在被问及评估问题和计划脓肿治疗方案(如返回急诊、住院)时,经常会有羞耻感和被评判的感觉。他们在接受评估后不愿意接受或继续接受治疗,这与以前的经历有关。参与者说:

对我来说,要想寻求帮助,需要付出很多!只有病得很重时才会向医院求助!我们真的需要一个安全的注射部位,这样脓肿就不会发生。我会在去医院之前自己切开脓肿。我会先从别人那里获得口服抗生素,然后如果情况恶化,才会去医院。这将是我的最后一站。医院应该优先处理脓肿。为什么我不能从药房或药剂师那里得到治疗?如果每天需要静脉注射抗生素四次,而又很难下定决心去医院复诊ÅcÅc我没有去复诊也不足为奇。很多人没有车,或者没有钱付停车费,所以就没有去医院复诊!如果错过了一次用药,情况会更糟,因为必须重新入院,然后等待、等待、再等待。

治疗时受到尊重

与会者分享了受到尊重的治疗和与团队协商的经验。

我的脓肿感染很严重,我就去找人给我治疗。他们对我很好。我需要治疗,就去了急诊室,他们对我很好。我很不好意思去,我只知道我必须去那里。我是一个人去的。他们让我抽根烟,所以我留下来了。

我不想去医院。人们最初是有偏见的。他们问我是不是静脉注射吸毒者,然后他们在房间里后退了几步。我不喜欢这样。然而,他们确实给我手上的脓肿引了流。治疗得还可以ÅcÅc事实上,当打破隔阂,知道自己被接纳时,我感觉很好。治疗对我来说有好处。

医院的情况还不错。我只需要把注意力放在脓肿上。他们对我很好,很公平。脓肿被切开时,气味非常难闻。我在医院没有感觉有耻辱感。他们对我很好;我等了几个小时,但可以接受。其他人也在等待治疗。你必须待人友善,释放善意,然后别人就会善待你。

我去看急诊,医生和护士都对我很好。我每天复诊两次,连续三天,然后口服了一个星期的抗生素。它把我从脓毒症中救了出来。我差点就死了(泪流满面)。我在急诊时受到了很友善的对待,尽管也听到过一些负面的消息。我真的很害怕,但我得到了团队很好的治疗。在我自己处理这个区域后,我会告诉人们去看急诊。

我永远不会刺破我的脓肿。我太害怕了。我在门诊得到了很好的治疗,他们用了碘酒和包扎纱布,我想我遇到了好护士。他们对我很好,这很重要。我不希望被任何人看不起,因为这让我很不爽。

我去寻求治疗,他们对我很好。当我需要抗生素时,我就去买。我没有从街上的人那里得到抗生素。我不想拿我的生命冒险。有人会卖给你任何东西,并称其为抗生素。我知道在寻求帮助时我会感到尴尬,但这就是我的情况,我需要治疗。

在疫情期间,我接受了一次虚拟伤口评估,然后感觉好多了。他们教我在发红的皮肤边缘做标记,并告诉我,如果发红更严重,就去看急诊。我去看了急诊,得到了很好的治疗。我的急诊情况比较好,因为我不是一个人去的,有一个支持我的人陪同非常有帮助Å\Å\然后我没有离开。

我们将这一主题理解为对避免医院治疗的叙述的一种反驳。PWID明白有时需要到医院治疗。此外,与在PWID之间流传的故事相反,医院的治疗过程可能会让人感觉受到尊重。

主题4:教育很重要;请勿操之过急

参与者表示,安全注射药物和皮肤卫生方面的教育非常重要。每个参与者都回顾了最初教他们如何注射药品和保持皮肤卫生的人。他们描述了漏针的风险,当他们不小心注射到脂肪层、皮下或肌肉层,或者药物渗入皮肤时。一名参与者通过互联网视频学习了如何注射。另一名参与者从前任伴侣那里学到了新的过滤器和针头的使用方法:

她教给我关于棉花热的知识,因为我做错了。还有,我用大针头扎小静脉,结果长了脓肿。没有人教我,我是从别人那里学会使用的。我只因漏针而得过一次脓肿,我的上臂和乳房部位因此而变得肿胀。我无法入睡,无法使用胳膊和手。有人会向你展示一种非常非常糟糕的技术。你必须看到血,然后再把它推进去,正确的方式很重要。教育应提醒人们不要操之过急,如果没有看到血,就不要注射。大家会急着注射。不要着急,没有血血Å\Å\就不注射,那么你就不会漏针。另外,如果你感觉不舒服,指望别人帮你注射,这不是好事,因为这个人可能会操之过急而漏针。

四名参与者表示他们从该中心的护士那里学会了如何安全注射。他们欣然描述了使用清洁的设备、炊具、针头和用酒精棉签清洁皮肤的重要性。三名参与者指出教育课程应包括正确的注射技术、关于漏针风险的讨论,以及SSTI和脓肿的图片,以便与自己的脓肿进行比较,从而确定严重程度。

讨论

这项小型质量改进研究28在在一个减少危害中心与大学研究人员合作进行的。由于该中心的职责,有目的地从该中心的客户中招募人员可能会影响到调查结果32。访谈数据显示了大量的描述30,31。研究结果表明,PWID经历了与注射和脓肿有关的学习曲线。参与者通常从自我护理开始,在因伤口恶化而感到紧迫性时,会使用正规的医疗服务。参与者的回答表明了他们对风险的理解、对治愈和/或预防脓肿的渴望,以及人们需要受到尊重的对待。从质量改进的角度,他们提出了改进措施,包括以下建议:1)延长社区伤口护理诊所和中心的服务时间;2)允许药剂师开具外用和口服抗生素处方;3)促进对客户和医疗服务提供者的脓肿预防教育;以及4)希望在急诊看病的过程中能够受到尊重。

Dechman及其同事讨论了PWID复杂而独特的经历24。 PWID的目标是静脉注射药物,不打算漏针或无意中注射到组织中(皮下组织或肌肉组织)2。我们的研究结果表明,参与者在首次注射时,并不总是了解因细菌或病毒造成的SSTI和脓肿形成。然而,随着时间的推移,他们了解到未扎进静脉(如外周静脉、股骨静脉、颈部静脉)的严重性。他们还了解与公用或重复使用设备相关的风险、与发生静脉塌陷和硬化、蜂窝组织炎、脓肿和严重感染的关系。参与者能够一致地描述脓肿的早期和晚期症状21,36。此外,参与者知道他们有脓肿后,就开始进行自我护理干预。如果没有改善,他们就会接受正规的医疗服务。这些发现表明,PWID是有一定知识的,从自我护理开始,在需要的时候会寻求正式的护理,无论是否面对沉默。我们将此过程理解为一个有意义的连续护理过程。他们还描述了在盟友中心和社区护理团队中保持和发展伤口护理护士的作用的重要性。

对急症治疗的需求和由此产生的沉默

对于参与者而言,尽管他们知道脓肿会导致脓毒症、住院治疗和死亡,但还是不愿意寻求正规的医疗服

务24。参与者希望在接受急症治疗时受到尊重。不愿就医的原因与对正规医护人员的看法和担心不被尊重有关。参与者希望在整个接触过程中得到尊重的对待。他们还需要获得可靠的交通方式以及停车费。在医院里等待并不是首选,尽管有朋友陪伴或者能够到外面抽支烟可以缩短等待时间。参与者建议医疗保健专业人员接受相关教育,为患有皮肤和伤口并发症的PWID提供有同理心和尊重的治疗33。

抗生素管理

PWID的抗生素管理值得关注,也难以解决37,38。参与者讨论了药剂师开具抗生素处方的必要性。外用和口服抗生素可按处方使用,与脓肿被判断为更严重的另一个人共用,给予或出售给他人,或妥善保管以备将来使用20-22。世界卫生组织(WHO)建议持续开展与正确使用抗生素有关的教育39。对PWID来说,这意味着可以获得教育材料(例如,在线材料、印刷材料和研讨会)21,以及持续并易于获得用于制备和注射药物的新设备37,40。

Harvey及其同事40调查了医疗保健专业人员对PWID预防感染的知识。专业人员透露,他们几乎没有接受过减少危害的教育,不愿意向PWID提供咨询,也不知道向PWID提供教育或用品的地方。为了降低PWID的发病率和死亡率,Harvey等人开发了“注射药物使用中预防感染的六个时刻”提供者教育工具40(p.1)。该工具包强调了一个广泛的框架,该框架侧重于PWID的感染预防。

本研究的参与者反复表示他们愿意学习,他们希望能安全地避免并发症。他们要求开发描述从轻度蜂窝组织炎到复杂脓肿的视频和手机应用。后者有风险,因为不建议仅将伤口图像作为轻度、进展中和严重感染的诊断工具36。

结论

在本研究中,参与者了解了SSTI和脓肿的发生。尽管他们意识到了(死亡、发病)的风险,但他们仍然不愿意接受正规的医疗服务。还需要更多的研究来充分了解伤口护理服务的维持和扩展,包括药剂师在社区中的作用。此外,对PWID的教育是一贯的信息,PWID希望有一致、可信的材料来学习。最后,PWID希望他们在获得医疗服务时能得到尊重。我们的采访经历让我们想知道如何最好地描述参与者的谦逊、智慧和善良。他们很有想法,希望改善自己和他人的体验。

致谢

我们感谢参与者分享他们的故事以及深思熟虑的建议。

利益冲突声明

作者声明无利益冲突。

资金支持

作者未因该项研究收到任何资助。

Author(s)

Janet L Kuhnke*

RN BA BScN MS NSWOC

Cape Breton University – Nursing

1250 Grand Lake Road, Sydney, Nova Scotia B1P 6L2, Canada

Email janet_kuhnke@cbu.ca

Sandra Jack-Malik

PhD (Education)

School of Education & Health, Cape Breton University

Sandi Maxwell

BA Soc(Honours)

Research Assistant, Cape Breton University

Janet Bickerton

RN BN MEd (Co-Investigator-CI)

Health Services Coordinator, The Ally Centre of Cape Breton, Sydney, Nova Scotia

Christine Porter

The Ally Centre of Cape Breton, Sydney, Nova Scotia

Nancy Kuta-George

RN

Wound Care Clinic, Victorian Order of Nurses, Membertou,

Cape Breton, Nova Scotia

* Corresponding author

References

- Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Needle exchange programs (NEPs) FAQs 2019. Available from: https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/ccsa-010055-2004.pdf

- Hope VD, Parry JV, Ncube F, Hickman M. Not in the vein: ’missed hits’, subcutaneous and intramuscular injection and associated harms among people who inject psychoactive drugs in Bristol, United Kingdom. Int J Drug Policy 2016;28:83–90.

- Asher AK, Zhong Y, Garfein RS, Cuevas-Mota J, Teshale E. Association of self-reported abscess with high-risk injection-related behaviors among young persons who inject drugs. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2019;30:142–150.

- Sanchez DP, Tookes H, Pastar I, Lev-Tov H. Wounds and skin and soft tissue infections in people who inject drugs and the utility of syringe service programs in their management. Adv Wound Care 2021;10:571–582.

- Ramakrishnan K, Salinas RC, Higuita NIA. Skin and soft tissue infections. Am Fam Physician 2015;92:474–488.

- Sahu KK, Tsitsilianos N, Mishra AK, Suramaethakul N, Abraham G. Neck abscesses secondary to pocket shot intravenous drug abuse. BJM Case Report 2020;13:1–2.

- Pastorino A, Tavarez MM. Incision and drainage. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Dellinger EP, Goldstein EJC, Borbach SL, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Disease Society of America. IDSA Guideline 2014;59:e1-e52.

- Stanway A. Skin infections in IV drug users 2002. Available from: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/skin-infections-in-iv-drug-users/

- Lavender TW, McCarron B. Acute infections in IDU. Royal College Physicians 2013;13:511–513.

- Maloney S, Keenan E, Geoghegan N. What are the risk factors for soft tissue abscess development among injection drug users? Nursing Times 2010;106. Available from: https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/substance-misuse/what-are-the-risk-factors-for-soft-tissue-abscess-development-among-injecting-drug-users-14-06-2010/

- Khalil PN, Huber-Wagner S, Altheim D, Burklein D, Siebeck M, Hallfeldt K, et al. Diagnostic and treatment options for skin and soft abscesses in injecting drug users with consideration of the natural history and concomitant risk factors. Eur J Med Res 2008;13:415–424.

- Larney S, Peacock A, Mathers BM, Hickman M, Degenhardt L. A systematic review of injecting-related injury and disease among people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;171:39–49.

- Hrycko A, Mateu-Gelabert P, Ciervo C, Linn-Walton R, Eckhardt B. Severe bacterial infections in people who inject drugs: the role of injection-related tissue damage. Harm Reduct J 2022;19:1–13.

- Lloyd-Smith E, Kerr T, Hogg RS, Li K, Nontamer JSG, Wood E. Prevalence and correlates of abscesses among a cohort of injection drug users. Harm Reduct J 2005;2:1–4.

- Leung NS, Padgett P, Robinson DA, Brown EL. Prevalence and behavioural risk factors of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization in community-based injection drug users. Epidemiol Infect 2015;143:2430–2439.

- Luktke H. Abscess incision/drainage. Rush University Medical Center; 2016.

- Tsybina P, Kassir S, Clark M. Skinner S. Hospital admissions and mortality due to complications of injection drug use in two hospitals in Regina, Canada: retrospective chart review. Harm Reduct J 2021;18:44. doi:10.1186/s12954-021-00492-6

- Tarusuk J, Zhang J, Lemyre A, Cholete F, Bryson M, Paquette D. National findings from the Tracks survey of people who inject drugs in Canada, Phase 4, 2017–2019. Can Commun Dis Rep 2020;46:138–148.

- Phillips KT, Stein MD. Risk practices associated with bacterial infections among injection drug users in Denver, Colorado. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2010;36:92–97.

- Gilbert AR, Hellman JL, Wilkes MS, Rees VW, Summers PJ. Self-care habits among people who inject drugs with skin and soft tissue infections: a qualitative analysis. Harm Reduc J 2019;16:1–11.

- Fink DS, Lindsay SP, Slymen DJ, Kral AH, Bluthemthal RN. Abscess and self-treatment among IDU at four California syringe exchanges and their surrounding communities. Subst Use Misuse 2013;48:523–531.

- Johnson JL, Bottorff JL, Browne AJ, Grewal S, Hilton BA, Clarke H. Othering and being othered in the context of health care services. Health Comm 2004;16:255–271.

- Dechman MK, Bickerton J, Porter C. Paths leading into and out of injection drug use. Ally Centre of Cape Breton, Cape Breton University; 2017. Available from: https://www.allycentreofcapebreton.com/images/Files/PathsLeadingIntoAndOutOfInjectionDrugUse-October-2017.pdf

- Koivi S, Piggott T. Approaching the health and marginalization of people who use opioids. In: Arya AN, Piggott T, editors. Under-served: health determinants of Indigenous, inner-city, and migrant populations in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Scholars; 2018;153-165.

- Summers PJ, Struve IA, Wilkes MS, Rees VW. Injection-site vein loss and soft tissue abscesses associate with black tar heroin injections: a cross sectional study of two distinct populations in USA. Int J Drug Policy 2017;3:21–27.

- Nova Scotia Government Department of Health and Wellness. Nova Scotia’s opioid use and overdose framework; 2017. Available from: https://novascotia.ca/opioid/nova-scotia-opioid-use-and-overdose-framework.pdf

- Patton MQ. Evaluation flash cards: embedding evaluative thinking in organizational culture. Otto Bremer Trust; 2018.

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Continuum; 2011.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research a practical guide for beginners. London: SAGE Publishing; 2013.

- Creswell JW. A concise introduction to mixed methods research. London: SAGE Publishing; 2015.

- Liamputtong P. Researching the vulnerable. Sage; 2007.

- Treloar C, Rance J, Yates K, Mao L. Trust and people who inject drugs: the perspectives of clients and staff of needle syringe programs. Int J Drug Policy 2016;27:138–45.

- Bickerton J. Ally Centre outreach street health pilot: final report 2022. Available from: https://www.allycentreofcapebreton.com/images/Files/Final-report-Outreach-Street-Health.pdf

- Government of Nova Scotia. Coronavirus (COVID-19) latest guidance; 2022. Available from: https://novascotia.ca/coronavirus/

- Li S, Renick P, Senkowsky J, Nair A, Tang L. Diagnostics for wound infections. Adv Wound Care 2021;10:317–327.

- Peckham AM, Chan MG. Antimicrobial stewardship can help prevent inject drug use-related infections. Contagion 2020;6(2)

- 18-19. Available from: https://www.contagionlive.com/view/antimicrobial-stewardship-can-help-prevent-injection-drug-use-related-infections

- Marks LR, Liang SY, Muthulingam D, Schwarz ES, Liss DB, Munigala S, Warren DK, Durkin MJ. Evaluation of Partial Oral Antibiotic Treatment for Persons Who Inject Drugs and Are Hospitalized With Invasive Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Dec 17;71(10):e650-e656. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa365. PMID: 32239136; PMCID: PMC7745005.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Antimicrobial stewardship interventions: a practical guide; 2021. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/340709/9789289054980-eng.pdf

- Harvey L, Boudreau J, Sliwinski SK, Strymish J, Gifford AL, Hyde J, et al. Six moments of infection prevention in injection drug use: an educational toolkit for clinicians. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022;6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8794071/