Volume 40 Number 2

Therapeutic patient education; A multifaceted approach to healthcare

Laurence Lataillade and Laurent Chabal

Keywords Wound care, Therapeutic patient education, person-centred care, stomal therapy

For referencing Lataillade L and Chabal L . Therapeutic patient education; A multifaceted approach to healthcare. WCET® Journal 2020;40(2):35-42.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.2.35-42

Abstract

This contribution presents a literature review of therapeutic patient education (TPE) in addition to providing a summary of an oral presentation given by two wound care specialists at a European Congress. It relates this to models of care in nursing science and to other research that contributes to this approach at the core of healthcare practice.

Therapeutic patient education: an introduction to its practical application in patients with stomas and/or wounds

Up until 1970, educational approaches were rare and limited to a few isolated interventions such as the ‘manual for diabetics’. In 1972, Leona Miller, an American doctor, demonstrated the positive effects of patient education. Using a pedagogical approach, she enabled patients from under-resourced areas of Los Angeles living with diabetes to control their pathology and improve their independence by relying on less medication1.

In 1975, Professor Jean Philippe Assal, a diabetologist from Geneva, Switzerland, adopted this concept and created a department for the treatment and education of diabetes at Geneva University Hospitals. He created an innovative, interdisciplinary team consisting of nurses, physicians, dieticians, psychologists, caregivers, art therapists and physiotherapists, all with the goal of encouraging patient engagement in their learning2. The team was inspired by person-centred theories developed by Carl Rogers3, work by Kübler-Ross on the grief process4, contributions from Geneva on education science in adult learning, and work on the conceptions of learners of didactics and epistemology of science in Geneva.

Since then, therapeutic education of patients (TPE) has been developed for patients with different chronic diseases and disorders, such as asthma, pulmonary insufficiency, cancer, inflammatory bowel disease and, in particular, for patients with stomas and/or wounds. The aim of TPE is to assist patients and caregivers to better understand the nature of the disease a person has, the treatment strategies required and to help patients achieve a greater level of individual autonomy in how they manage and cope with their disease.

Definition of therapeutic patient education (TPE)

According to the World Health Organization (1998), TPE is education managed by healthcare providers trained in the education of patients, and is designed to enable a patient (or a group of patients and families) to manage the treatment of their condition and prevent avoidable complications, while maintaining or improving quality of life. Its principal purpose is to produce a therapeutic effect additional to that of all other interventions – pharmacological, physical therapy, etc. Therapeutic patient education is designed therefore to train patients in the skills of self-managing or adapting treatment to their particular chronic disease, and in coping processes and skills. It should also contribute to reducing the cost of long-term care to patients and to society. It is essential to the efficient self-management and to the quality of care of all long-term diseases or conditions, although acutely ill patients should not be excluded from its benefits.

Thus, “TPE should enable patients to acquire and maintain abilities that allow them to optimally manage their lives with their disease. It is therefore a continuous process that should be integrated into healthcare”5.

The premise of TPE as a healthcare approach is that it places the patient(s) or the caregiver(s) at the centre of the healthcare provider patient relationship, acknowledging them as an integral partner in healthcare processes6–8. The cornerstone of this approach is that the patient has knowledge, skills and experiences that must be valued, encouraged, stimulated and/or explored. As for health practitioners, they need to recognise and highlight the patient’s knowledge about themselves and capabilities, which requires the health practitioner to adapt their own position to care provision and education. Healthcare providers often tend to talk to patients about their disease rather than train them in daily management processes to assist patients to better manage their condition5. As Gottlieb explains9,10, it is more than a change in behaviour but a paradigmatic change that implores the practitioner to rely on the patient’s strengths rather than remedying their deficiencies and going further than Orem’s Model11 proposed.

TPE is a model of education and support for people living with one or more chronic diseases. The goal is to support the person being cared for by engaging them with their care by means of an educational program which makes sense for them and, in doing so, reduces the risk of complications12 and improves their quality of life. The tools of TPE promote a true collaboration between the patient and the healthcare practitioner. This requires a holistic, integrative and interdisciplinary approach13.

What is the objective of TPE? What position should practitioners adopt?

The goal for practitioners who employ TPE is to enable their patients to become independent in their care processes and to improve their quality of life. Nevertheless, patient goals are not always the same at every juncture. For example, the sudden arrival of the disease, such as a colonic cancer and the formation of a stoma, which is often a consequence thereof, have a major impact on the patient’s life. The ostomy patient goes through many emotional processes that are often profound and intense which sometimes overwhelms them completely.

Therapeutic patient education aims to support the patient in the stages and process of this emotional adjustment so that they can better adapt14 to and accommodate their disease and stoma in their day-to-day life. The goal is for the patient to acquire skills for managing their stoma and treatment as well as psychosocial skills to integrate their stoma into their daily life.

The challenge for practitioners is to reconcile these two types of learning in the TPE program while taking into account the difficulties encountered by the patient and their learning needs. A therapeutic relationship based on mutual trust and partnership is an indispensable condition for this educational process. In the framework of this alliance, the emphasis is placed on a relationship of moral equivalence between the patient and practitioner15.

The first educational stage within the TPE framework constitutes encouraging and making space for the patient to express themselves in order to reveal and agree on their particular needs which may not always be evident to either the patient or the health practitioner.

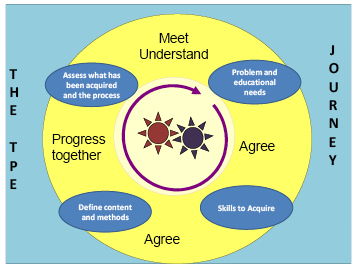

Figure 1. The TPE journey schema

In the TPE journey schema (the proposed Geneva TPE model), loosely translated from Lasserre Moutet et al.16 (Figure 1), the schema describes the following concepts:

- The two cog wheels in the middle represent the patient and the practitioner, both engaged in active movement. They both possess a specific knowledge base of their own. The practitioner possesses scientific knowledge, clinical skills and their clinical experience with other patients who have faced similar healthcare conditions; the patient possesses their individual lived experience with their disease and their treatment in addition to their own knowledge. Although this relationship is, by nature, asymmetric, it is nevertheless not ranked in terms of knowledge. The practitioner is a mediator who supports the patient in the process of transforming their knowledge to better understand their disease, consequences of the disease process and remedial medical interventions. For these gears to work, the rhythm must be adjusted. The first part of the TPE journey is especially important in upholding this engagement: the patient and practitioner must agree on the problem, revealing the reality of the situations that the patient encounters on a daily basis. For the practitioner, this involves developing a genuine interest in the patient and their life story with their disease.

- On the basis of this common understanding, educational needs, practical skills and competencies to be acquired by the patient will be elucidated in order for the patient to be able to overcome their difficulties or resolve their day-to-day problems.

- Once the goals are defined in conjunction with the patient, the strategies employed will lead the patient to encounter new ideas, to experience a new perspective on their situation, and to find alternatives to organise their daily life.

- Finally, the journey and the changes made will be evaluated jointly in order to make adjustments and continue the process.

This four-step approach can be carried out during one or more consultations.

What kind of therapeutic education should we use for patients with stomas?

Patients with stomas are confronted with physical changes and, often, a chronic disease17,18 which restricts their ability to envision a new reality for their life. One of the key roles of the stomal therapy nurse is to help the patient engage in suitable learning that will allow them to adapt, step by step, to a new life balance.

Whether the stoma is temporary or permanent, it is a shock and affects every aspect of the patient’s life: social and professional life, emotional and family life, personal identity and self-esteem. In situations where the stoma is temporary, it is often seen as a major obstacle in the person’s life for the period of time with which they live with the stoma. Once the intestine is reconnected, some patients dread that they will need a new stoma, which is indeed a possibility.

With the goal of patient independence with respect to the management of their care needs or, when this is not possible for the ostomy patient, for caregivers, stomal therapy nurses integrate TPE as a continuous process of comprehension of the patient’s lived experience and create a partnership, teaching and informing the patient throughout all stages of treatment – pre-operative, postoperative, rehabilitation, home care and short- or long-term follow-up.

This patient’s education focuses on different themes depending on the patient’s needs. For example, organisational aspects related to the stoma (care, changing the appliance, balanced digestion, food safety, etc.) which necessitate self-care. Some self-adjustment difficulties, such as a distorted self-image, low self-esteem and additional psycho-emotional implications19–21 and difficulty talking about the disease or stoma with their social circle, or resuming sexual activity, will most likely require the development of psychosocial coping skills and competencies to facilitate adaptation. The practitioner can thus apply their knowledge, clinical know-how and interpersonal skills to find appropriate teaching strategies for the patient or caregiver’s learning styles, all the while respecting/integrating patient’s limits, fears, and any resistance in order to lead them through each step of the process. Ultimately, successful integration of these processes will allow patients to perform their own self-care and adapt to their life with the ostomy and sometimes their chronic disease.

What stages do ostomy patients go through and how can we help them overcome them?

According to Selder22, the lived experience of a chronic disease is akin to a journey through a disturbed reality that is full of uncertainty and which, ultimately, leads to a restructuring of that reality.

In order to mobilise the patient’s resources, by working on their resilience23,24, consilience (coping skills)25 and empowerment26 skills, practitioners must take it upon themselves to meet the person and understand their representations, values and beliefs27,28 in order to incorporate them into their healthcare. These aspects, which are very much linked to the socio-cultural and religious context that the individual has assimilated, must also be considered in order to integrate them into the care provided to them29,30.

According to Bandura31,32, patients’ sense of self-efficacy relies on four aspects: personal mastery, modelling, social learning, and their physiological and emotional state. This generates three types of positive effects in patients with a good level of self-efficacy: the first relates to the choice of behaviours adopted, the second on the persistence of behaviours adopted, and the third on their great resilience in the face of unforeseen events and difficulties. Nurses who practise TPE will be able to mobilise, through their healthcare interventions, these four aspects of TPE for the purpose of inducing these three types of effects in the patient.

According to Diclemente et al.33, behavioural life changes can only be carried out in stages. In stomal therapy, these patient-centred approaches begin in the pre-operative stage where explanations are provided to the patient (and family where possible) on the potential need for the stoma, the surgical procedure and postoperative care (WCET® recommendation 3.1.2, SOE=B+29), even though the ostomy has not yet been confirmed. These recommendations have been adopted by the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society® (WOCN®)34.

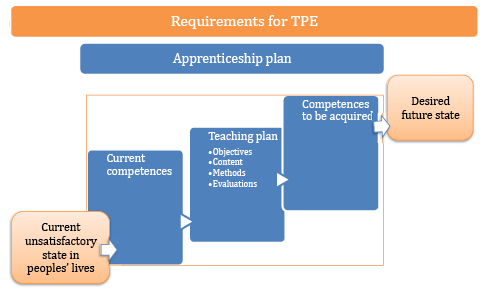

The schema, adapted and loosely translated from Martin and Savary35, describes the main steps of the learning process that need to be met and nurtured (Figure 2). Depending on the age of the patient, the knowledge, tools, and processes employed in adult education, TPE requirements may be necessary components to mobilise in order to attain them36,37. Other strategies will need to be adopted for younger populations, particularly with respect to adolescents38,39.

Figure 2. TPE requirements

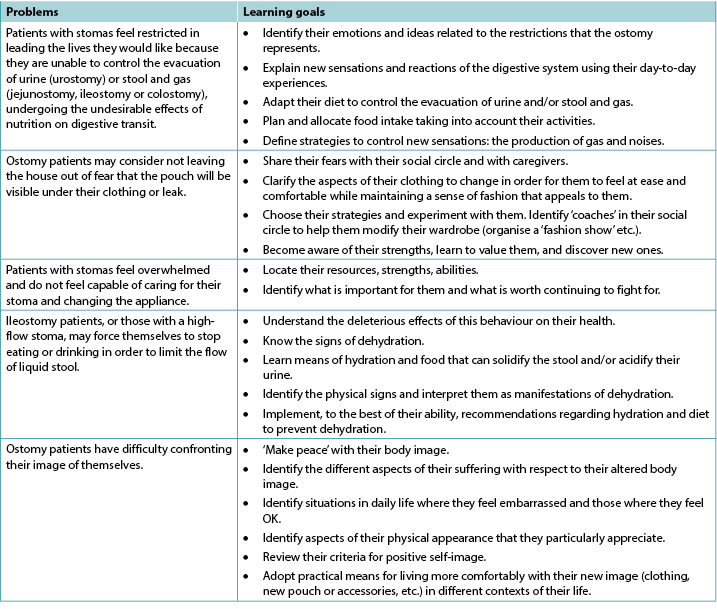

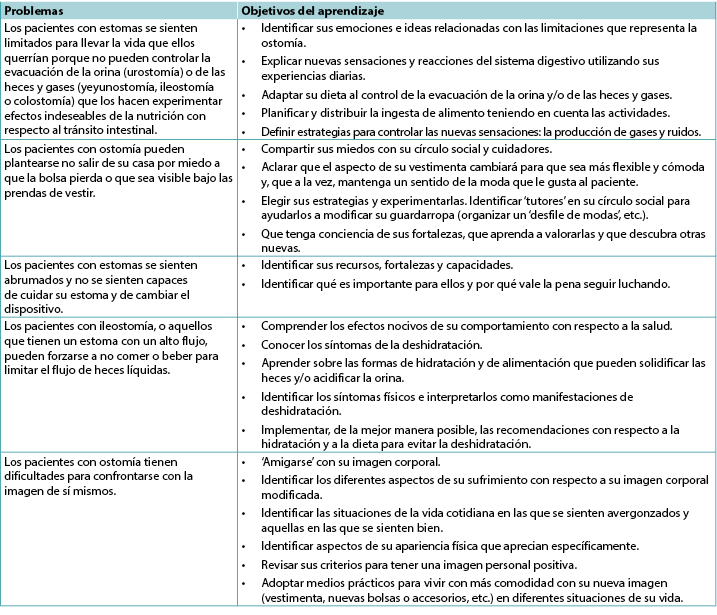

Examples of problems and goals in the therapeutic education of patients with stomas

These problems and instructional goals may apply for patients with incontinent ostomies, which are reflective of the most encountered scenarios (Table 1).

Table 1

In the case of patients with other, less common types of ostomy, like those with continent ostomies or nutritional support ostomies40,41, some of these items are still applicable and/or will need to be adapted to their particular situation; additional and more specific problems may apply. This is also the case for patients with enterocutaneous fistulae42.

In some situations, whether due to disgust, refusal, denial and/or disability (motor function, cerebral, psycho-emotional or psychiatric), the ostomy patient may not be able to undergo some or all of these processes of learning and empowerment43. This can be a short-term, medium-term or sometimes long-term problem. In these instances, recourse to a caregiver, whether a practitioner or a close relative, should be envisaged and organised. The educational process necessary for their empowerment must be carried out in a relatively similar manner with a view on promoting patient enabling to the maximum extent possible that allows the ostomy patient to return home. To the latter must be added supportive communication and management of and potential changes to interpersonal relationships and, potentially, to intimate relationships between the patients and their partners. Such changes can be generated by applying the principles of TPE, and this type of care and will need to be regularly re-evaluated and taken into consideration with a holistic approach to the patient and their respective situations.

These processes are even more complicated for patients who live alone at home, and even more so if they are elderly, as this can call their discharge home into question as well as their ability to remain at home. The need for strong communication relays and networks to be implemented in these circumstances recalls the advice offered within the 2012 American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) report45,46.

Lastly, the ostomy patient will occasionally find themselves with more than one stoma, all of which may be permanent (Figures 3 and 4). From our experience, these complex situations are more frequent than they were previously and are often related to malignant pathology.

Figure 3. Example of a person with a permanent left colostomy and a trans-ileal cutaneous ureterostomy (Bricker’s intervention) with purple urine bag syndrome47.

Figure 4. Example of a postoperative patient several days later with a temporary colostomy and a protective ileostomy. Digestive continuity would be restored in 9 months over two interventions, commencing with the downstream ostomy before the upstream ostomy, over an interval of a few weeks.

Insights and further information relating to patients with chronic wounds

Contrary to some preconceptions, stomal therapy is not solely concerned with the care of ostomy patients, even though the usage of the original term enterostomal therapist (ET)48 may lead to confusion. Indeed, the full Enterostomal Therapist Nursing Education Program (ETNEP)49 includes providing healthcare for people with wounds, people with continence disorders, those with enterocutaneous fistulae and, in some schools, for those with mastectomies. That said, wound care specialisation has become a specialist service unto itself and many ETs or stomal therapy nurses collaborate closely with wound specialists. It is important to note that these aspects of patient education are specified in the European curriculum for nurses specialising in wound care (Units 3 & 4)50–52.

In the literature, in reference to education provided to patients with wounds, knowledge has been described as a process of self-management, particularly among individuals living with a chronic disease such as a leg ulcer53. For education to be effective, the patient must acquire a perceived benefit from the changes that their involvement in the preventive activities proposed could generate. Physical, or emotional, benefits will reinforce the positive effects of the advice given54.

The benefit of using a multimedia teaching approach lies in the combination of methods for transmitting information. This helps resolve the problems encountered by the patient but also reinforces the information they are provided with55,56.

Numerous Cochrane Systematic Reviews have been carried out regarding patients with venous ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers and pressure injuries. They have revealed that:

- For patients with leg ulcers, there is not enough research available to assess strategies for supporting patients that would increase their adherence /compliance, despite the fact that compliance with compression is recognised as an important factor in preventing leg ulcer recurrence57.

- In relation to diabetic patients, there is not enough evidence to say that education – in the absence of other preventive measures – is sufficient to reduce the occurrence of foot lesions and foot/lower limb amputations58.

- Finally, as for pressure injuries, the authors have noted that the idea of patient involvement remains vague and includes a significant number of factors which vary and include a wide range of interventions and possible activities. At the same time, they clarify that this involvement in care, such as the respect of the rights of the patient, are important values which could play a role in their healthcare. This involvement could have the benefit of improving their motivation and knowledge in relation to their health. In addition, such involvement could entail an increase in their ability to manage their disease and to take care of themselves, thus improving their sense of security and enabling them to have better results when it comes to improving their health59.

As for patients with cancerous wounds, the European Oncology Nursing Society recommendations note the existence of scales for the evaluation of symptoms for the typology of these wounds, allowing for early detection of associated complications, as well as the reduction of care-related costs and of equipment used in healthcare, all the while improving patient involvement. Indeed, some of the tools described could be suggested to patients for them to use to assist with managing their condition60. In order for this to happen, education on their use will be necessary, despite the fact that these people may have lost confidence in themselves, their treatment, and their healthcare teams; even though their disease may have improved, their wounds still serve as visible stigmas of their disease.

Conclusion

Therapeutic education is the cornerstone of interventions conducted with individuals with chronic disease, or in chronic conditions, with the goal of health-related promotion, prevention and education. It is a fundamental activity that cuts across all the fields of the specialisation in stomal therapy. As every situation is unique, therapeutic education enables practitioners to develop skills in this area to improve the provision of care. It also incites us to innovate, be creative, adapt, and to think outside the box in order to find other interventional strategies; it also requires us to show humility, which may lead us to ask for help via our professional networks nationally and/or internationally.

According to Adams61, TPE remains a vast area of interventions in which the utility of educational interventions in improving healthcare impacts are still under discussion. However, the results of studies are still too limited to support their evidence. For other authors, the efficacy has, to date, been borne out by the research. For many hospitals, it is reportedly a cost-saving measure, as it enables shorter hospital stays and reduces the number of complications62–66.

Lastly, while the educational process starts at the hospital, it is followed up in both outpatient and home care services. In this sense, the implementation and maintenance of communication relays will be primordial in ensuring continuity of care, coherence and coordination of the processes undertaken as well as those of future stages that will be collaboratively decided upon. The involvement of family caregivers in these processes, with the consent of the patient and their relatives, is important. They serve as resources that cannot be neglected, even though their involvement may generate other issues that must be accounted for.

The training of healthcare professionals, particularly nurses, in the application of TPE will reinforce their expertise and efficiency67 in patient education, with the knowledge that every situation will push them to find new strategies and skills to overcome the challenges faced.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The wound section was partially based on notes taken during the University Conference Model (UCM) session68 on the subject. This session took place at the 2017 Congress of the European Wound Management Association (EWMA) in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and was presented by Julie Jordan O’Brien, Clinical Nurse Specialist Tissue Viability and Véronique Urbaniak, Advanced Practice Nurse69.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Educación terapéutica del paciente: abordaje multifacético para la asistencia sanitaria

Laurence Lataillade and Laurent Chabal

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.40.2.35-42

RESUMEN

Esta colaboración presenta una revisión de bibliografía con respecto a la educación terapéutica del paciente (ETP) además de brindar el resumen de una presentación oral realizada por dos especialistas sobre el cuidado de las heridas en un Congreso Europeo. Dicha colaboración se relaciona con modelos de atención en la ciencia de la enfermería y con otra investigación que contribuye a este abordaje que es la esencia de la práctica de la asistencia sanitaria.

Educación terapéutica del paciente: una introducción a su aplicación práctica en pacientes con estomas y/o heridas

Hasta 1970, los abordajes educativos eran raros y estaban limitados a unas pocas intervenciones aisladas, tales como el ‘manual para personas con diabetes’. En 1972, Leona Miller, una médica estadounidense, demostró los efectos positivos de la educación del paciente. Al usar un abordaje pedagógico, ella ayudó a los pacientes de Los Ángeles que vivían con diabetes y que pertenecían a áreas con menos recursos a controlar su patología y mejorar su independencia dependiendo menos de la medicación1.

En 1975, el profesor Jean Philippe Assal, diabetólogo de Ginebra, Suiza, adoptó este concepto y creó un departamento en los Hospitales Universitarios de Ginebra para tratamiento y educación. Creó un equipo innovador e interdisciplinario que consistía en personal de enfermería, médicos, dietistas, psicólogos, cuidadores, arteterapeutas y fisioterapeutas, todos con el objetivo de alentar la participación del paciente en su aprendizaje2. El equipo se inspiró en las teorías centradas en las personas y elaboradas por Carl Rogers3, en los trabajos de Kübler-Ross sobre el proceso de duelo4, en colaboraciones de Ginebra sobre la ciencia de la educación con respecto al aprendizaje del adulto y en el trabajo sobre las concepciones de los alumnos con respecto a la didáctica y la epistemología de la ciencia en Ginebra.

Desde entonces, la educación terapéutica del paciente (ETP) ha sido desarrollada para pacientes con diferentes enfermedades y trastornos crónicos, tales como asma, insuficiencia pulmonar, cáncer, enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal y, específicamente, para los pacientes con estomas y/o heridas. El objetivo de la ETP es ayudar a los pacientes y cuidadores a comprender mejor la naturaleza de la enfermedad que tiene una persona, las estrategias de tratamiento necesarias, y ayudar a las personas a lograr un mayor nivel de autonomía individual con respecto a cómo ellos manejan y enfrentan la enfermedad.

Definición de educación terapéutica del paciente (ETP)

Según la Organización Mundial de la Salud (1998), la ETP es la educación impartida por los prestadores de asistencia sanitaria formados en la educación de pacientes y diseñada para instrumentar a un paciente (o a un grupo de pacientes y familiares) para que pueda manejar el tratamiento de su enfermedad y evitar complicaciones que se pueden prevenir, conservando o mejorando la calidad de vida. Su objetivo principal es producir un efectos terapéutico adicional a todas las otras intervenciones, p. ej. tratamiento farmacológico, físico, etc. Por consiguiente, la educación terapéutica del paciente está diseñada para formar a los pacientes para que adquieran las habilidades de autogestión o adaptación del tratamiento a su enfermedad crónica específica y para que incorporen los procesos y habilidades. También deberá contribuir a reducir el costo de la atención a largo plazo de los pacientes y de la sociedad. Esto es esencial para la autogestión eficiente y para la calidad de la atención de todas las enfermedades y afecciones prolongadas, aunque no se deben excluir de dichos beneficios a los pacientes graves.

Por consiguiente, la “ETP debe lograr que los pacientes adquieran y mantengan la capacidad para que puedan convivir con la enfermedad de manera óptima. Por ende, se debe integrar un proceso continuo a la asistencia sanitaria”5.

La premisa de la ETP como abordaje de la asistencia sanitaria es colocar al(los) paciente(s) o a los cuidador(es) en el centro de la relación del paciente con el prestador de asistencia sanitaria, reconociéndolos como una parte integral en los procesos de la asistencia sanitaria6–8. El aspecto fundamental de este abordaje es que el paciente tenga el conocimiento, la habilidad y la experiencia que se debe valorar, alentar, estimular y/o explorar. En cuanto a los profesionales de la salud, ellos deben reconocer y destacar el conocimiento del paciente sobre sí mismo y de sus capacidades; por lo tanto, es necesario que el profesional de la salud adapte su propia posición para brindar cuidado y educación. A menudo, los prestadores de asistencia sanitaria tienden a hablar con los pacientes sobre su enfermedad en vez de formarlos en los procesos del tratamiento diario para ayudarlos a controlar mejor la enfermedad5. Según lo explica Gottlieb9,10, es más que un cambio en el comportamiento, es un cambio paradigmático que exhorta al médico a confiar en las fortalezas del paciente en vez de tratar que el paciente supere sus carencias e ir más allá del modelo propuesto por Orem11.

La ETP es un modelo de educación y apoyo para personas que conviven con una o más enfermedades crónicas. El objetivo es ayudar a las personas cuidadas a que participen de su cuidado por medio de un programa educativo que tenga sentido para ellos y, al hacerlo, se reduzcan los riesgos de complicaciones12 y se mejore la calidad de vida. Las herramientas de la ETP promueven una verdadera colaboración entre el paciente y el profesional de la salud. Esto requiere un abordaje holístico, integrador e interdisciplinario13.

Figura 1. El esquema de la trayectoria de la ETP

¿Cuál es el objetivo de la ETP? ¿Qué posición deben adoptar los profesionales de la salud?

El objetivo de los profesionales de la salud que emplean la ETP es lograr que los pacientes sean más independientes en los procesos de atención y que mejoren su calidad de vida. No obstante, los objetivos del paciente no siempre son los mismos en cada coyuntura. Por ejemplo, con la aparición abrupta de la enfermedad, tal como un cáncer de colon, y la formación de un estoma como consecuencia del cáncer, tiene un impacto importante sobre la vida del paciente. El paciente con ostomía atraviesa muchos procesos emocionales que, a menudo, son profundos e intensos, y que muchas veces los abruma por completo.

La educación terapéutica del paciente está destinada a apoyar al paciente en las etapas y procesos de esta adaptación emocional para que puedan adaptarse mejor14 y para que puedan adecuar su enfermedad y el estoma a la vida diaria. El objetivo para el paciente es adquirir habilidades para tratar el estoma y el tratamiento, así como también habilidades psicosociales para integrar el estoma a su vida cotidiana.

El desafío para los profesionales de la salud es conciliar estos dos tipos de aprendizajes en el programa de la ETP y, a la vez, tener en cuenta las dificultades con la que se enfrenta el paciente y sus necesidades de aprendizaje. Es condición indispensable para su proceso educativo una relación terapéutica basada en la confianza y en la colaboración mutua. En el marco de esta alianza, se pone énfasis en la relación de igualdad moral entre el paciente y el profesional de la salud15.

La primera etapa educativa dentro del marco de la ETP constituye en alentar y en darle espacio al paciente para que se exprese a fin de manifestar y acordar sobre sus necesidades específicas que no siempre son evidentes para el paciente o para el profesional de la salud.

En el esquema de la trayectoria con la ETP (el modelo de la ETP propuesto en Ginebra), con traducción libre de Lasserre Moutet y cols.16 (Figura 1), el esquema describe los siguientes conceptos:

- Las dos ruedas de engranaje del medio representan al paciente y al profesional de la salud, ambos participan en un movimiento activo. Ambos poseen una base de conocimiento específica propia. El profesional de la salud posee un conocimiento científico, habilidades clínicas y su experiencia clínica con otros pacientes que han enfrentado condiciones de asistencia sanitaria similares; el paciente posee su experiencia de vida personal con su enfermedad y con el tratamiento, además de su propio conocimiento. A pesar de que su relación es, por naturaleza, asimétrica, no obstante no se la clasifica en términos de conocimiento. El profesional de la salud es un mediador que ayuda al paciente en el proceso de transformar su conocimiento para comprender mejor la enfermedad, las consecuencias de la enfermedad y las intervenciones médicas preventivas. Para que estos engranajes funcionen, se debe adaptar el ritmo. La primera parte de la trayectoria con la ETP es especialmente importante para mantener su participación: el paciente y el profesional deben estar de acuerdo con respecto al problema, poniendo de manifiesto la realidad de las situaciones con las que el paciente se encuentra a diario. Para el profesional de la salud, esto implica desarrollar un interés genuino en el paciente y en su historia de vida con su enfermedad.

- Sobre la base de esta comprensión común, se elucidarán las necesidades educativas, las habilidades y competencias prácticas que el paciente debe adquirir a fin de que el paciente pueda sobrellevar las dificultades o resolver sus problemas diarios.

- Una vez que los objetivos están definidos en conjunto con el paciente, las estrategias empleadas ayudarán al paciente a encontrar nuevas ideas, a experimentar una nueva perspectiva de su situación y a encontrar alternativas para organizar su vida cotidiana.

- Finalmente, la trayectoria y los cambios realizados serán evaluados en conjunto para realizar ajustes y continuar con el proceso.

Este abordaje de cuatro pasos se puede llevar a cabo durante una o más consultas.

¿Qué clase de educación terapéutica debemos usar para los pacientes con estomas?

Los pacientes con estomas se enfrentan a cambios físicos y, a menudo, a una enfermedad crónica17,18 que les limita la capacidad de imaginar una nueva realidad para su vida. Uno de los papeles fundamentales de la enfermería especializada en el tratamiento estomal es ayudar al paciente para que participe en el aprendizaje adecuado que le permitirá adaptarse, paso a paso, a un nuevo equilibrio de vida.

Ya sea que el estoma sea temporario o permanente, es un impacto que afecta todos los aspectos de la vida del paciente: la vida social y profesional, la vida emocional y familiar, la identidad personal y la autoestima. En situaciones en las que el estoma es temporario, a menudo se lo ve como un obstáculo importante en la vida de la persona por el período durante el cual vive con el estoma. Una vez que se vuelve a conectar el intestino, algunos pacientes temen necesitar un nuevo estoma, hecho que, por cierto, es una posibilidad.

Con el objetivo de que el paciente tenga independencia con respecto al tratamiento de las necesidades de cuidado, o cuando esto no sea posible para el paciente con ostomía, para los cuidadores, el personal de enfermería especializado en el tratamiento estomal integra la ETP como un proceso continuo de comprensión de la experiencia vivida por el paciente, y genera una alianza al enseñarle e informarle al paciente sobre todas las etapas del tratamiento: preoperatorio, posoperatorio, rehabilitación, atención a domicilio y seguimiento a corto y largo plazo.

La educación del paciente se enfoca en diferentes temas según las necesidades del paciente. Por ejemplo, en los aspectos organizativos relacionados con el estoma (cuidado, cambio de dispositivo, digestión equilibrada, seguridad de los alimentos, etc.) que necesitan autocuidado. Es muy probable que algunas dificultades de autoajuste, tales como la imagen personal distorsionada, la baja autoestima y la implicancia psicoemocional adicional19–21, además de la dificultad para hablar de la enfermedad o del estoma con su círculo social, o para retomar la actividad sexual, requieran del desarrollo de habilidades y competencias para enfrentar el medio psicosocial y para facilitar la adaptación. Por consiguiente, el profesional de la salud puede aplicar su conocimiento, su saber cómo clínico y sus habilidades interpersonales para encontrar las estrategias de enseñanza adecuadas para el estilo de aprendizaje del paciente y del cuidador, siempre respetando e integrando los límites del paciente, los miedos y cualquier resistencia a fin de guiarlo en cada uno de los pasos del proceso. En última instancia, la integración con éxito de estos procesos ayudará a los pacientes a llevar a cabo su propio autocuidado y a adaptar su vida a la ostomía y, algunas veces, a su enfermedad crónica.

¿Qué etapas atraviesan los pacientes con ostomía y cómo podemos ayudarlos a sobrellevarlas?

Según Selder22, la experiencia de vida de una enfermedad crónica se parece a un viaje a través de una realidad alterada que está llena de incertidumbres y que, en última instancia, conduce a una reestructuración de esa realidad.

A fin de movilizar los recursos del paciente trabajando sobre su resiliencia23,24, consiliencia (habilidad para enfrentar problemas)25 y habilidades de empoderamiento26, los médicos tienen que encargarse de conocer a la persona y de comprender sus manifestaciones, valores y creencias27,28, a fin de incorporarlas a la asistencia sanitaria. Estos aspectos, que están muy vinculados con el contexto religioso y sociocultural que la persona ha asimilado, deben considerarse a fin de integrarlos al l cuidado que se les brinda29,30.

Según Bandura31,32, el sentido de autoeficacia del paciente se basa en cuatro aspectos: el dominio personal, la modelación, el aprendizaje social y su estado emocional y fisiológico. Esto genera tres tipos de efectos positivos en los pacientes con buen nivel de autoeficacia: el primero se relaciona con la elección del comportamiento adoptado, el segundo con la persistencia del comportamiento adoptado y el tercero con la gran resiliencia frente a eventos y dificultades imprevistos. El personal de enfermería que ejerce la ETP podrá movilizar -mediante sus intervenciones de asistencia sanitaria- estos cuatro aspectos de la ETP a fin de inducir estos tres tipos de efectos en el paciente.

Según Diclemente y cols.33, los cambios de vida conductuales solo se pueden llevar a cabo por etapas. En el tratamiento estomal, estos abordajes centrados en el paciente comienzan en la etapa preoperatoria, cuando se le dan las explicaciones al paciente (y a su familia, cuando sea posible) sobre la necesidad potencial de realizar el estoma, sobre el procedimiento quirúrgico y la atención posoperatoria (recomendación del WCET® 3.1.2, SOE=B+29), incluso cuando no se haya confirmado aún la ostomía. Estas recomendaciones han sido adoptadas por la Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society® (WOCN®, por sus siglas en inglés)34.

El esquema, adaptado y con traducción libre de Martin y Savary35, describe los pasos principales del proceso de aprendizaje que se deben cumplir y enseñar (Figura 2). Según la edad del paciente, el conocimiento, las herramientas y los procesos empleados en la educación del adulto, los requisitos de la ETP pueden ser componentes necesarios para movilizar con el objeto de alcanzarlos36,37. En poblaciones más jóvenes, se deberán adoptar otras estrategias, especialmente con respecto a los adolescentes38,39.

Figura 2. Requisitos de la ETP

Ejemplos de problemas y objetivos en la educación terapéutica de los pacientes con estomas

Estos problemas y objetivos instructivos se pueden aplicar a los pacientes con ostomías de incontinencia, que son los escenarios más comunes (Cuadro 1).

Cuadro 1

En el caso de pacientes con otras ostomías, tipos de ostomías menos comunes, como aquellos con ostomías continentes o de apoyo nutricional40,41, algunos de estos elementos aún se aplican y/o se deberán adaptar a su situación particular; además, pueden surgir problemas adicionales y más específicos. Este también es el caso de los pacientes con fístulas enterocutáneas42.

En algunas situaciones, ya sea debido a disgustos, negaciones, rechazos o discapacidad (función motora, cerebral, psicoemocional o psiquiátrica), es posible que el paciente con ostomía no se pueda someter a alguno, o a todos, estos procesos de aprendizaje y empoderamiento43. Esto puede ser un problema a corto plazo, a mediano plazo o, a veces, a largo plazo. En estas instancias, se debe contemplar y organizar la posibilidad de recurrir a un cuidador, ya sea un médico o un pariente cercano. El proceso educativo necesario para su empoderamiento se debe llevar a cabo de manera relativamente similar, con miras a fomentar, al mayor grado posible, la capacidad que le ayude al paciente con ostomía a regresar a su casa. A esto último se le debe agregar una comunicación de apoyo y de manejo de cambios potenciales en las relaciones interpersonales, así como también, potencialmente, en las relaciones íntimas entre pacientes y sus parejas. Dichos cambios se pueden generar aplicando los principios de la ETP; este tipo de atención deberá ser reevaluado con regularidad y se lo debe tener en cuenta desde un enfoque holístico para el paciente y para sus respectivas situaciones.

Estos procesos son incluso más complicados para los pacientes que viven solos en la casa, e incluso mucho más, si son mayores, dado que esto puede poner en duda darle el alta para que vuelva a su casa, así como también su capacidad para quedarse en ella. En estas circunstancias se debe transmitir e implementar un sistema de comunicación y de redes que recuerda el consejo brindado en el informe de 2012 emitido por la Asociación Estadounidense de Personas Jubiladas (AARP, por sus siglas en inglés)45,46.

Por último, el paciente con ostomía ocasionalmente se encontrará con más de un estoma, y todos pueden ser permanentes (Figuras 3 y 4). Según nuestra experiencia, estas situaciones complejas son más frecuentes de lo que eran anteriormente y, a menudo, se relacionan con una patología maligna.

Figura 3. Ejemplo de una persona con una colostomía permanente izquierda y una ureterostomía cutánea transileal (operación de Bricker) con síndrome de la bolsa de orina púrpura47.

Figura 4. Ejemplo de un paciente posoperatorio varios días después con una colostomía temporaria y una ileostomía protectora. La continuidad digestiva sería restaurada en 9 meses con dos intervenciones, comenzando con la ostomía descendente antes de la ostomía ascendente, con un intervalo de unas pocas semanas.

Opiniones y mayor información relacionada con los pacientes con heridas crónicas

Al contrario de algunos preconceptos, el tratamiento estomal no se refiere únicamente al cuidado de los pacientes con ostomía, a pesar de que el uso del término original de terapeutas enterostomales (TE)48 puede prestarse a confusión. Por cierto, el Programa de educación para el personal de enfermería como terapeutas enterostomales (ETNEP)49 incluye brindar asistencia sanitaria a personas con heridas, a personas con trastornos de incontinencia, a aquellas con fístulas enterocutáneas y, en algunas facultades, a personas con mastectomías. Habiendo dicho eso, la especialización del cuidado de heridas se ha convertido en un servicio especializado en sí mismo y muchos TE o personal de enfermería especializado en el tratamiento estomal colaboran estrechamente con los especialistas en heridas. Es importante destacar que estos aspectos de la educación del paciente están especificados en el curso europeo para el personal de enfermería especializado en el cuidado de las heridas (Unidades 3 y 4)50–52.

En la bibliografía, en referencia a la educación brindada a los pacientes con heridas, el conocimiento ha sido descrito como un proceso de autogestión, específicamente para personas que viven con una enfermedad crónica, tal como úlceras en la pierna53. Para que la educación sea eficaz, el paciente debe lograr percibir los beneficios a partir de los cambios que podría generar su participación en las actividades preventivas propuestas. Los beneficios físicos, o emocionales, reforzarán los efectos positivos del consejo dado54.

El beneficio de usar un abordaje de enseñanza de multimedia reside en la combinación de métodos para transmitir la información. Esto ayuda a resolver los problemas que encuentra el paciente, pero también refuerza la información que se les brinda55,56.

Se han llevado a cabo diversas revisiones sistemáticas Cochrane con respecto a pacientes con úlceras venosas, úlceras del pie diabético y lesiones por presión. Estas han revelado que:

- Para los pacientes con úlceras en la pierna, no hay suficiente investigación disponible para evaluar las estrategias para dar apoyo a los pacientes, hecho que podría aumentar el cumplimiento [del tratamiento], a pesar de que se reconoce al cumplimiento con la compresión como un factor importante para evitar la recurrencia de la úlcera en la pierna57.

- Con relación a los pacientes con diabetes, no hay suficientes pruebas para decir que la educación -en ausencia de otras medidas preventivas- es suficiente para reducir la ocurrencia de lesiones en el pie y la amputación de una extremidad inferior o de un pie58.

- Finalmente, en cuanto a las lesiones por presión, los autores han observado que la idea de la participación del paciente sigue siendo vaga e incluye un número significativo de factores que varían e incluyen una amplia gama de intervenciones y actividades posibles. Al mismo tiempo, ellos aclaran que esta participación en su atención, tal como el respeto de los derechos del paciente, son valores importantes que podrían desempeñar una función [importante] en su asistencia sanitaria. Esta participación podría tener el beneficio de mejorar su motivación y conocimiento con relación a su salud. Además, dicha participación podría implicar un aumento de la capacidad para tratar su enfermedad y para cuidarse a sí mismos, mejorando, por consiguiente, el sentido de la seguridad y ayudándolos a que obtengan mejores resultados a la hora de mejorar la salud59.

En cuanto a los pacientes con heridas cancerosas, las recomendaciones de la Sociedad Europea de Enfermería Oncológica destacan la existencia de escalas para la evaluación de los síntomas para detectar la tipología de estas heridas, lo que permite la detección precoz de complicaciones asociadas, así como también la reducción de costes relacionados con el cuidado y con el equipo utilizado en la asistencia sanitaria, a la vez que aumenta el compromiso del paciente. Por cierto, algunas de las herramientas descritas podrían sugerirse a los pacientes para que ellos las usen para ayudarlos a que traten su enfermedad60. A fin de que esto ocurra, será necesaria la educación sobre su uso, a pesar del hecho de que estas personas puedan haber perdido confianza en sí mismas, en su tratamiento y en los equipos de asistencia sanitaria; incluso cuando la enfermedad pueda haber tenido una buena evolución, sus heridas aún sirven como estigmas visibles de su enfermedad.

Conclusión

La educación terapéutica es el pilar de las intervenciones realizadas en las personas con enfermedades crónicas o con afecciones crónicas con el objeto de promover, prevenir y educar en materia de salud. Es una actividad fundamental que abarca todos los campos de la especialización del tratamiento estomal. Dado que cada situación es única, la educación terapéutica les ayuda a los médicos a desarrollar habilidades en esta área para mejorar la prestación de la atención. También nos incita a innovar, a ser creativos, a adaptarnos, a abrir la mente a fin de buscar otras estrategias de intervención; también nos exige mostrar humildad, que nos permita pedir ayuda a nuestras redes profesionales a nivel nacional e internacional.

Según Adams61, la ETP sigue siendo una amplia área de intervenciones en la que aún está bajo discusión la utilidad de las intervenciones educativas para mejorar los impactos de la asistencia sanitaria. Sin embargo, los resultados de los estudios son aún demasiado limitados como para respaldar estas pruebas. Para otros autores, hasta la fecha, la eficacia está demostrada por investigación. Para muchos hospitales, supuestamente, es una medida para ahorrar costes, dado que permite estancias más cortas en el hospital y reduce la cantidad de complicaciones62–66.

Por último, si bien el proceso educativo comienza en el hospital, se realiza un seguimiento tanto de los servicios de asistencia a domicilio como del paciente ambulatorio. En este sentido, el sistema y la implementación de la comunicación será primordial para garantizar la continuidad de la atención, la coherencia y la coordinación de los procesos llevados a cabo, así como también las etapas futuras que se deben decidir de manera colaborativa. En estos procesos, es importante la participación de los cuidadores de la familia, con el consentimiento del paciente y de sus parientes. Sirven como recursos que no se pueden subestimar, a pesar de que su participación puede generar otros problemas que se deben tener en cuenta.

La formación de los profesionales de la salud, específicamente el personal de enfermería, para la aplicación de la ETP reforzará su experiencia y eficiencia67 con respecto a la educación del paciente, el conocimiento de cada situación los alentará a buscar nuevas estrategias y habilidades para superar los retos con los que se enfrentan.

Conflicto de intereses

Los autores declaran que no hay conflictos de intereses.

La sección con respecto a las heridas se basó parcialmente en las notas tomadas durante la sesión del modelo de conferencia universitario (UCM, por sus siglas en inglés)68 sobre el tema. Esta sesión se llevó a cabo en el Congreso de la Asociación Europea de Tratamiento de Heridas (EWMA, por sus siglas en inglés) de 2017 en Ámsterdam, Países Bajos, y fue presentada por Julie Jordan O’Brien, enfermera clínica especializada en viabilidad del tejido y Véronique Urbaniak, enfermería clínica especializada69.

Financiación

Los autores no recibieron financiación para este estudio.

Author(s)

Laurence Lataillade

Clinical Specialist Nurse and Stomatherapist, Geneva University Hospitals

Laurent Chabal*

Stomal Therapy Nurse and Lecturer, Geneva School of Health Sciences, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland. Haute École de Santé Genève, HES-SO Haute École Spécialisée de Suisse Occidentale, Vice-President of WCET® 2018–2020

* Corresponding author

References

- Miller LV, Goldstein J. More efficient care of diabetic patients in a county-hospital setting. N Engl J Med 1972;286:1388–1391.

- Lacroix A, Assal JP. Therapeutic education of patients – new approaches to chronic illness, 2nd ed. Paris: Maloine; 2003.

- Rogers C. Client-centered therapy, its current practice, implications and theory. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1951.

- Kübler-Ross E. On death and dying. London: Routledge; 1969.

- World Health Organization. Therapeutic patient education, continuing education programmes for health care providers. Report of a World Health Organization Working Group; 1998. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/145294/E63674.pdf

- Stewart M, Belle Brown J, Wayne Weston W, MacWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient-centered medicine: transforming the clinical method. Oxon: Radcliffe; 2003.

- Kronenfeld JJ. Access to care and factors that impact access, patients as partners in care and changing roles of health providers. Research in the sociology of health care. Bingley: Emerald Book; 2011.

- Dumez V, Pomey MP, Flora L, De Grande C. The patient-as-partner approach in health care. Academic Med: J Assoc Am Med Coll 2015;90(4):437–1.

- Gottlieb LN, Gottlieb B, Shamian J. Principles of strengths-based nursing leadership for strengths-based nursing care: a new paradigm for nursing and healthcare for the 21st century. Nursing Leadership 2012;25(2):38–50.

- Gottlieb LN. Strengths-based nursing care: health and healing for persons and family. New York: Springer; 2013.

- Orem DE. Nursing: concepts of practice. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book Inc; 1991.

- The Official Website of the Disabled Persons Protection Commission; 2018. Available from: http://www.mass.gov/dppc/abuse-prevention/types-of-prevention.html

- Finset A, editor. Patient education and counselling journal. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2019. Available from: https://www.journals.elsevier.com/patient-education-and-counseling/

- Roy, C. The Roy adaptation model. New Jersey: Pearson; 2009.

- Price P. How we can improve adherence? Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2016;32(S1):201–5.

- Lasserre Moutet A, Chambouleyron M, Barthassat V, Lataillade L, Lagger G, Golay A. Éducation thérapeutique séquentielle en MG. La Revue du Praticien Médecine Générale 2011;25(869):2–4.

- Ercolano E, Grand M, McCorkle R, Tallman NJ, Cobb MD, Wendel C, Krouse R. Applying the chronic care model to support ostomy self-management: implications for nursing practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2016;20(3):269–74.

- World Health Organization. Non-communicable diseases; 2020. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/noncommunicable_diseases/en/

- Price B. Explorations in body image care: Peplau and practice knowledge. J Psychiatric Mental Health Nurs 1998;5(3):179–186.

- Segal N. Consensuality: Didier Anzieu, gender and the sense of touch. New York: Rodopi BV; 2009.

- Anzieu D. The skin-ego. A new translation by Naomi Segal (The history of psychoanalysis series). Oxford: Routledge; 2016.

- Selder F. Life transition theory: the resolution of uncertainty. Nurs Health Care 1989;10(8):437–40, 9–51.

- Cyrulnik B, Seron C. Resilience: how your inner strength can set you free from the past. New York: TarcherPerigee; 2011.

- Scardillo J, Dunn KS, Piscotty R Jr. Exploring the relationship between resilience and ostomy adjustment in adults with permanent ostomy. J WOCN 2016;43(3): 274–279.

- Wilson EO. Consilience: the unity of knowledge. New York: Knopf; 1998.

- Zimmerman MA. Empowerment theory, psychological, organizational and community levels of analysis. In Rappaport J, Seidman E, editors. Handbook of community psychology. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2000. p. 43–63.

- Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Behav 1988;15(2):175–183.

- Knowles SR, Tribbick D, Connel WR, Castle D, Salzberg M, Kamm MA. Exploration of health status, illness perceptions, coping strategies, psychological morbidity, and quality of life in individuals with fecal ostomies. J WOCN 2017;44(1):69–73.

- Zulkowski K, Ayello EA, Stelton S, editors. WCET international ostomy guideline. Perth: Cambridge Publishing, WCET; 2014.

- Purnell L. The Purnell Model applied to ostomy and wound care. JWCET 2014;34(3):11–18.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol Rev 1977;84(2):191–215.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Psychological review. San Francisco: Freeman WH; 1997.

- Diclemente CC, Prochaska JO. Toward a comprehensive, transtheoretical model of change: stages of change and addictive behaviours. In Miller WR, Heather N, editors. Treating addictive behaviours. processes of change. New York: Springer; 1998. p. 3–24.

- Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society – Guideline Development Task Force. WOCN® Society clinical guideline management of the adult patient with a fecal or urinary ostomy – an executive summary. J WOCN 2018;45(1):50–58.

- Martin JP, Savary E. Formateur d’adultes: se professionnaliser, exercer au quotidien. 6th ed. Lyon: Chronique Sociale; 2013.

- Lataillade L, Chabal L. Therapeutic patient education (TPE) in wound and stoma care: a rich challenge. ECET Bologna, Italy [Oral presentation]; 2011.

- Merriam SB, Bierema LL. Adult learning: linking theory and practice. Indianapolis: Jossey-Bass; 2013.

- Mohr LD, Hamilton RJ. Adolescent perspectives following ostomy surgery, J WOCN 2016;43(5): 494–498.

- Williams J. Coping: teenagers undergoing stoma formation. BJN 2017;26(17):S6–S11.

- Stroud M, Duncan H, Nightingale J. Guidelines for enteral feeding in adult hospital patients. Gut 2003;52(7):vii1–vii12.

- Roveron G, Antonini M, Barbierato M, Calandrino V, Canese G, Chiurazzi LF, Coniglio G, Gentini G, Marchetti M, Minucci A, Nembrini L, Nari V, Trovato P, Ferrara F. Clinical practice guidelines for the nursing management of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and jejunostomy (PEG/PEJ) in adult patients. An executive summary. JWCON 2018;45(4):32–334

- Brown J, Hoeflok J, Martins L, McNaughton V, Nielsen EM, Thompson G, Westendrop C. Best practice recommendations for management of enterocutaneous fistulae (ECF). The Canadian Association for Enterostomal Therapy; 2009. Available from: https://nswoc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/caet-ecf-best-practices.pdf

- Jukes M. Learning disabilities: there must be a change in attitude. BJN 2004;13(22):1322.

- Wendorf JH. The state of learning disabilities: 507 facts, trends and emerging issues. 3rd ed. New York: National Center for Learning Disabilities, Inc; 2014.

- Reinhard SC, Levine C, Samis S. Home alone: family caregivers providing complex chronic care. AARP Public Policy Institute; 2012.

- Reinhard SC, Ryan E. From home alone to the CARE act: collaboration for family caregivers. AARP Public Policy Institute, Spotlight 28; 2017.

- Peters P, Merlo J, Beech N, Giles C, Boon B, Parker B, Dancer C, Munckhof W, Teng H.S. The purple urine bag syndrome: a visually striking side effect of a highly alkaline urinary tract infection. Can Urol Assoc J 2011;5(4):233–234.

- Erwin-Toth P, Krasner DL. Enterostomal therapy nursing. Growth & evolution of a nursing specialty worldwide. A Festschrift for Norma N. Gill-Thompson, ET. 2nd ed. Perth: Cambridge Publishing; 2012.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®, Education Committee; 2020. Available from: http://www.wcetn.org/the-wcet-education

- Pokorná A, Holloway S, Strohal R, Verheyen-Cronau I. Wound curriculum for nurses: post-registration qualification wound management – European qualification framework level 5. J Wound Care 2017;26(2):S9–12, S22–23.

- Prosbt S, Holloway S, Rowan S, Pokorná A. Wound curriculum for nurses: post-registration qualification wound management – European qualification framework level 6. J Wound Care 2019;28(2):S10–13, S27.

- European Wound Management Association. EQF level 7 curriculum for nurses; 2020. Available from: https://ewma.org/it/what-we-do/education/ewma-wound-curricula/eqf-level-7-curriculum-for-nurses-11060/

- Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Peel J, Baker DW. Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Educ Couns 2003;51(3):267–275.

- Van Hecke A, Beeckman D, Grypdonck M, Meuleneire F, Hermie L, Verheaghe S. Knowledge deficits and information-seeking behaviour in leg ulcer patients, an exploratory qualitative study. J WOCN 2013;40(4):381–387.

- Ciciriello S. Johnston RV, Osborne RH, Wicks I, Dekroo T, Clerehan R, O’Neill C, Buchbinder R. Multimedia education interventions for customers about prescribed and over-the-counter medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2013. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008416/full

- Moore Z, Bell T, Carville K, Fife C, Kapp S, Kusterer K, Moffatt C, Santamaria N, Searle R. International best practice statement: optimising patient involvement in wound management. London: Wounds International; 2016.

- Weller CD, Buchbinder R, Johnston RV. Intervention for helping people adhere to compression treatments for venous leg ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2013. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008378.pub2/abstract

- Dorrestelijn JA, Kriegsman DMW, Assendelft WJJ, Valk GD. Patient education for preventing diabetic foot ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2014. Available from: http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001488.pub5/abstract

- O’Connor T, Moore ZEH, Dumville JC, Patton D. Patient and lay carer education fort preventing pressure ulceration in at-risk populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2015. Available from: http://www.cochrane.org/CD012006/WOUNDS_patient-and-lay-carer-education-preventing-pressure-ulceration-risk-populations

- Probst S, Grocott P, Graham T, Gethin G. EONS recommendations for the care of patients with malignant fungating wounds. London: European Oncology Nursing Society; 2015.

- Adams R. Improving health outcomes with better patient understanding and education. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2010;3:61–72.

- Lagger G, Pataky Z, Golay A. Efficacy of therapeutic patient education in chronic diseases and obesity. Patient Educ Couns 2010;79(3):283–286.

- Kindig D, Mullaly J. Comparative effectiveness – of what? Evaluating strategies to improve population health. JAMA 2010;304(8):901–902.

- Friedman AJ, Cosby R, Boyko S, Hatt on-Bauer J, Turnbull G. Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: a systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. J Canc Educ 2011;26(1):12–21.

- Jensen BT, Kiesbye B, Soendergaard I, Jensen JB, Ammitzboell Kristensen S. Efficacy of preoperative uro-stoma education on self-efficacy after radical cystectomy; secondary outcome of a prospective randomised controlled trial. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2017;28:41–46.

- Rojanasarot S. The impact of early involvement in a post-discharge support program for ostomy surgery patients on preventable healthcare utilization. J WOCN 2018;45(1):43–49.

- Knebel E, editor. Health professions education: a bridge to quality (quality chasm). Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

- European Wound Management Association; 2020. Available from: http://ewma.org/what-we-do/education/ewma-ucm/

- European Wound Management Association Conference; 2017. Available from: http://ewma.org/ewma-conference/2017-519/