Volume 41 Number 2

Practice Implications from the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline 2020

Laurent O. Chabal, Jennifer L. Prentice and Elizabeth A. Ayello

Keywords ostomy, education, stoma, culture, guideline, International Ostomy Guideline, IOG, ostomy care, peristomal skin complication, religion, stoma site, teaching

For referencing Chabal LO et al. Practice Implications from the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline 2020. WCET® Journal 2021;41(2):10-21

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.2.10-21

Abstract

The second edition of the WCET® International Ostomy Guideline (IOG) was launched in December 2020 as an update to the original guideline published in 2014. The purpose of this article is to introduce the 15 recommendations covering four key arenas (education, holistic aspects, and pre- and postoperative care) and summarise key concepts for clinicians to customise for translation into their practice. The article also includes information about the impact of the novel coronavirus 2019 on ostomy care.

Acknowledgments

The WCET® would like to thank all of the peer reviewers and organizations that provided comments and contributions to the International Ostomy Guideline 2020. Although the WCET® gratefully acknowledges the educational grant received from Hollister to support the IOG 2020 development, the guideline is the sole independent work of the WCET® and was not influenced in any way by the company who provided the unrestricted educational grant.

The authors, faculty, staff, and planners, including spouses/partners (if any), in any position to control the content of this CME/NCPD activity have disclosed that they have no financial relationships with, or financial interests in, any commercial companies relevant to this educational activity.

To earn CME credit, you must read the CME article and complete the quiz online, answering at least 7 of the 10 questions correctly. This continuing educational activity will expire for physicians on May 31, 2023, and for nurses June 3, 2023. All tests are now online only; take the test at http://cme.lww.com for physicians and www.NursingCenter.com/CE/ASWC for nurses. Complete NCPD/CME information is on the last page of this article.

© Advances in Skin & Wound Care and the World Council of Enterostomal Therapists.

Introduction

Guidelines are living, dynamic documents that need review and updating, typically every 5 years to keep up with new evidence. Therefore, in December 2020, the World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® (WCET®) published the second edition of its International Ostomy Guideline (IOG).1 The IOG 2020 builds on the initial IOG guideline published in 2014.2 Hundreds of references provided the basis for the literature search of articles published from May 2013 to December 2019. The guideline uses several internationally recognised terms to indicate providers who have specialised knowledge in ostomy care, including ET/stoma/ostomy nurses and clinicians.1 However, for the purposes of this article, the authors will use “ostomy clinicians” and “person with an ostomy” to be consistent.

Guideline development

A detailed description of the IOG 2020 guideline methodology can be found elsewhere.1 Briefly, the process included a search of the literature published in English from May 2013 to December 2019 by the authors of this article, who comprise the Guideline Development Panel. More than 340 articles were reviewed. For each article identified, a member of the panel would write a summary, and all three would then confirm or revise the ranking of the article evidence. The evidence was categorised and defined and compiled into a table that is included in the guideline and can be accessed on the WCET® website. The strength of recommendations were rated using an alphabetical system (A+, A, A−, etc). Feedback was sought from the global ostomy community, and 146 individuals and 45 organizations were invited to comment on the findings. Of these, 104 individuals and 22 organizations returned comments, which were used to finalise the guideline.

Guideline overview

Because the WCET® is an international association with members in more than 65 countries, there is a strong emphasis on diversity of culture, religion, and resource levels so that the IOG 2020 can be applied in both resource-abundant and resource-challenged countries. The forward was written by Dr Larry Purnell, author of the Purnell Model for Cultural Competence (unconsciously incompetent, consciously incompetent, consciously competent, unconsciously competent).3-5 As with the 2014 guideline, the WCET® members and International Delegates were invited to submit culture reports from their country, and 22 were received and incorporated into the guideline development.

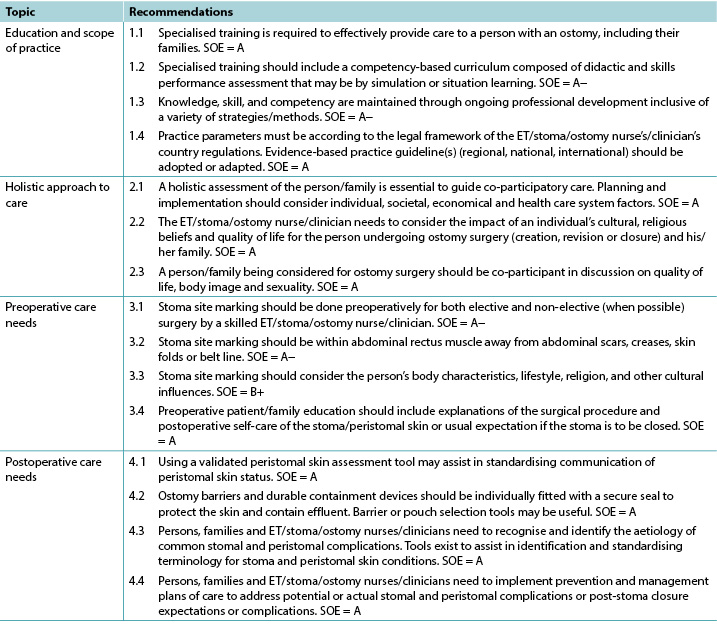

Because the IOG 2020 is intended to serve as a guide for clinicians in delivering care for persons with an ostomy, new to this edition is a section on guideline implementation. Also new is a recommendation for nursing education. A glossary of terms and helpful educational resources are also included in the various appendices. The 15 IOG 2020 recommendations are listed in Table 1. The recommendations have been translated into Chinese (Supplemental Table 1), French (Supplemental Table 2), Portuguese (Supplemental Table 3), and Spanish (Supplemental Table 4) and are also available on the WCET® website (www.wcetn.org).

Table 1 WCET® International OStomy Guideline 2020 Recommendations

©WCET® 2020, used with permission.

Abbreviations: ET, enterostomal therapy; SOE, strength of evidence.

Education

The evidence supports four IOG 2020 recommendations about education (Table 1). A person who has surgery resulting in the creation of an ostomy needs knowledge regarding their type of stoma, care strategies such as ostomy pouches, and the impact the ostomy will have on their lifestyle.6 Accordingly, the needs of these patients go beyond what may be taught in initial nursing education programs. Zimnicki and Pieper7 surveyed nursing students and found that just under half (47.8%) did not have experience in caring for a patient with an ostomy. For those who did, they felt most confident in pouch emptying.7 Findings by Cross and colleagues8 also support that staff nurses without specialised ostomy education felt more confident in emptying the ostomy pouch as opposed to other ostomy care skills. Duruk and Uçar9 in Turkey and Li and colleagues10 in China also reveal that staff nurses lack adequate knowledge about the care of patients with ostomies. Better ostomy care outcomes have been reported when patients are cared for by nurses who have had specialised ostomy education. This includes research in Spain by Coca and colleagues,11 Japan by Chikubu and Oike,12 and the UK by Jones.13

For over 40 years, the WCET® has promoted the importance of specialised ostomy education for nurses to better meet the needs of patients and their families.6 Other societies such as the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing Society in the US; Nurses Specialised in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada; and the Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK have also advocated for specialised nursing education. The suggested modifications include competence-based curricula and checklists of skills and professional performance necessary for the specialised nurse to provide appropriate care to patients with an ostomy and their families.14-17 Evidence-based practice requires that healthcare professionals keep abreast of new techniques, skills, and knowledge; lifelong learning is necessary.

Holistic aspects of care: culture and religion

The literature supports three highly ranked recommendations related to holistic care within the IOG 2020 (Table 1) and confirms the necessity of taking them into account when caring for individuals with an ostomy.

Ostomies can impact individuals in different domains such as day-to-day life, overall quality of life, social relationships, work, intimacy, and self-esteem. A holistic approach to care aims to acknowledge and address the patient’s need at a physiological, psychological, sociological, spiritual, and cultural level,18 especially when the patient’s situation is complex.19 Therefore, implementing a holistic approach to practice is crucial to address all of the potential issues.20

Many tools exist to assess patients’ quality of life, self-care adjustment, social adaptation, and/or psychological status.21,22 They provide important information to nurses in their clinical decisions making, although as always clinical judgment remains relevant. Because holistic care is multidimensional, using various methods will allow an integrative and global approach to caring for patients with ostomies.

The World Health Organization’s definition of health23 is still relevant today. An individual’s origins, beliefs, religion, culture, gender, and age will influence his/her interpretation of illness and diseases.24-26 For healthcare professionals, the need to understand these influences and their real impacts on the patient, family, and/or caregiver(s) is essential because it will provide key information to co-construct ostomy care.

Dr Larry Purnell’s Model for Cultural Competence3,4 can be readily applied to ostomy care.5 It can help nurses to deliver culturally competent care to patients with an ostomy. Integrating effective cultural competence will improve relationships among patients, families, and healthcare professionals,27 especially if patients and/or families are finding it difficult to cope.28

Specialised and nonspecialised nurses have a key role in patient, family, and caregiver education.29 They will, step by step, help support the development of specific skills and implementation of personalised adaptive strategies. Nurses’ advice and support can decrease ostomy-related complications,13,30,31 and listening to and addressing patient emotions will improve individuals’ self-care.32

Taking into account the International Charter of Ostomate Rights33 during provision of ostomy care will increase patients’ quality of life, because it supports patient empowerment and reinforces the partnerships among patients, families, caregivers, and healthcare professionals.

Section 6 of the IOG 2020 provides an international perspective on ostomy care. With contributions from 22 countries, this version is more inclusive than the previous one.2 It is the authors’ hope that it will help ostomy clinicians around the world when taking care of patients from another culture, background, or belief system and therefore give them better skills to address each individual’s needs.

Preoperative Care And Stoma Site Marking

As seen in Table 1, there are four recommendations that address preoperative care and stoma site marking. The literature emphasises preoperative education for patients who are about to undergo ostomy surgery, which includes preoperative site marking. Fewer complications are seen in persons who have their stoma sites marked before surgery.34,35

Because specialised nurses may not be available 24/7, patients who undergo unplanned/emergency surgery may not benefit from preoperative education and stoma site marking. Accordingly, the literature supports the training of physicians and nonspecialty nurses to do stoma site marking.34-37 Zimnicki36 completed a quality improvement project to train nonspecialised nurses in stoma site marking. This project significantly increased the number of patients who had preoperative stoma site marking and education.36

Stoma site marking is an important art and skill that is beyond the scope of this article to describe in detail. Major principles include observation of the patient’s abdomen while standing, sitting, bending over, and lying down (Figure 1).37-41 There are at least two techniques for identifying the ideal abdominal location.42-52 Those interested might consult the references42-60 as well as the WCET® webinar or pocket guide on stoma site marking (www.wcetn.org).52

Assess the abdomen in multiple positions when doing stoma siting

Figure 1 positions for stoma site marking ©2021 Ayello, used with permission.

Postoperative Care

The IOG 2020 lists four recommendations for postoperative care to assist ostomy clinicians to detect, prevent, or manage and thereby minimise the effect of any peristomal complications (Table 1).

Successful postoperative recovery following ostomy surgery is dependent on multiple factors from the perspective of both the ostomy clinician and person with an ostomy. All members of the care team, including the patient, must have a heightened awareness of preventive or remedial strategies for common problems that may occur with the formation of a new stoma, refashioning of an existing stoma, or stoma closure. The ability to recognise and effectively manage potential or actual postoperative ostomy and peristomal skin complications (PSCs) has inherent short- and long-term ramifications for the health, well-being, and independence of the persons with an ostomy61-63 and for health resource management.64-66

Postoperative ostomy complications may manifest as early or late presentations. Early complications such as mucocutaneous separation, retraction, stomal necrosis, parastomal abscess, or dermatitis may occur within 30 days of surgery. Later complications include parastomal hernias (PHs) and stomal prolapse, retraction, or stenosis.63,67,68

However, the most common postoperative complications are PSCs.69 Frequently cited causes of PSCs are leakage,70,71 no preoperative stoma siting,35 poor surgical construction techniques,72 ill-fitting appliances, and long wear time of appliances.71,73

Common PSCs include acute and chronic irritant contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis, the former arising from prolonged contact with feces or urine on the skin eventually causing erosion (Figure 2). Assessment of the abdomen, stoma, stoma appliance, and accessories in use as well as the patient’s ability to care for the stoma and correctly reapply his/her appliance is essential to determine the cause of leaks. Skin care, depending on the severity of irritation or denudation, may involve the use protective pectin-based powders or pastes, skin sealants (acrylate copolymer or cyanoacrylates wipes or sprays), and protective skin barriers. Adjustments to the type of appliance used and wear time may also be required ameliorate acute and prevent chronic irritant contact dermatitis.61,70,74

Figure 2 irritant dermatitis ©2021 Chabal, used with permission.

Allergic contact dermatitis results from an adverse reaction to substances within products applied to the skin during cleansing or skin protection used prior to appliance application or removal or that are part of the appliance itself.74,75 Compromised skin usually reflects the shape of the appliance if it is the allergen or the area where secondary skin care products have been used. Affected skin may have the appearance of a rash; be reddened, blistered, itchy, or painful; or exude hemoserous fluid (Figure 3). Patch testing small areas of skin well away from compromised skin and the stoma may be required to identify specific causative agents and/or assess the suitability of other skin barrier products used to gain a secure seal around the stoma.70,75

Figure 3 allergic contact dermatitis ©2021 Chabal, used with permission.

Parastomal hernias are a latent complication that also contributes to PSCs. Causes include surgical technique, the size and type of stoma, abdominal girth, and age and medical conditions such as prior hernias and diverticulitis fluid. Education of surgeons and prophylactic insertion of polypropylene mesh during surgery as well as postoperative patient education may decrease PH incidence (Figure 4).68,76,77 Further, providers must assess and measure the patient’s abdomen at the level of the stoma to choose the most appropriate support garment required to manage the degree of PH protrusion, prevent further exacerbation, and allow the stoma to continue to function normally.78 The ostomy appliance/pouch in use will also need to be frequently reassessed to address any changes in the size of the stoma.

Figure 4 parastomal hernia ©2021 Chabal, used with permission.

The IOG 2020 cites numerous tools that ostomy clinicians can use to effectively identify and classify PSCs79,80,81 and select appropriate skin barriers and appliances to manage PSCs.62,82

Finally, of increasing importance to improve the postoperative quality of life of individuals with an ostomy, reduce ostomy complications and associated readmissions, and enhance interprofessional practice are the use of early or enhanced recovery programs after surgery,83,84 ongoing education and discharge monitoring programs,68,85 and telehealth modalities for counseling and remote consultation.86,87

Guideline implementation

For clinical guidelines to result in positive outcomes for the intended patient populations, the proposed recommendations need to be adopted into daily practice. Multiple strategies are required to facilitate adoption,88,89 and guidelines should be reviewed and adapted for specific clinical contexts.90 Prior thought, therefore, is required regarding how guidelines will be disseminated and implemented. Potential barriers to guideline implementation may include a lack of resources, competing health agendas, or a perceived lack of interest in ostomy care as a medical/nursing subspecialty with no “champion” to advocate for and facilitate implementation. Last, guidelines may be seen as too prescriptive. The section on guideline implementation within the IOG 2020 provides advice, and readers are directed to the full guideline for more information.

Impact of Covid-19 on ostomy care

The review of the evidence for the IOG 2020 preceded the advent the novel coronavirus 2019. During the pandemic, there have been anecdotal reports of ostomy clinicians being reassigned to care for other patients. The extent and impact of this have yet to be researched. In the meantime, virtual visits may provide a safe alternative to in-person care for patients and providers.91 A study by White and colleagues92 reported on the feasibility of virtual visits for persons with new ostomies; 90% of patients felt that these visits were helpful in managing their ostomy.92 However, another study found that only 32% of the respondents knew that telehealth was an option.93 Further, 71% “did not think [their issue] was serious enough to seek assistance from a healthcare professional,”93 although 57% reported some peristomal skin occurrence during the pandemic.93 In descending order, the types of skin issues reported were redness or rash (79%), itching (38%), open skin (21%), bleeding (19%), and other concerns (7%).93

Conclusions

The IOG 2020 aims to provide clinicians with an evidence framework upon which to base their practice. The 15 IOG 2020 recommendations are applicable in countries where resources are abundant (nurses and healthcare professionals trained in ostomy care with manufactured appliances/pouches), as well as in countries with limited resources (nonspecialised nurses, healthcare professionals, and laypersons who create ostomy equipment from available local resources to contain the ostomy effluent). Specialised knowledge is needed to assist persons with an ostomy in learning how to apply, empty, and change their appliance/pouch, but living with an ostomy is more than that. All aspects of the patient need to be considered.

Holistic patient care should be individualised and address diet, activities of daily living, sexual life, prayer, work, medications, body image, and other patient-centered concerns. Preoperative stoma siting has been linked to better postoperative outcomes. Early identification and intervention for PSCs requires adequate teaching, as well as awareness of when to seek professional help. Nurses who have specialised knowledge in ostomy care can improve quality of life for persons with an ostomy, including those who experience PSCs.95 It is the authors’ hope that the IOG 2020 will enhance care outcomes and rehabilitation for this population.

Practice pearls

- Patients who are cared for by healthcare professionals with specialised ostomy knowledge experience better care outcomes.

- There are clinical tools to assist with peristomal skin assessment and appliance requirements.

- Pre- and postoperative patient and family education needs to be holistic and individualised.

- Patients who undergo presurgical stoma siting experience fewer complications.

- The most common PSC is leakage leading to irritant dermatitis.

- Telehealth and remote consultation might be advantageous in providing adjunct guidance to people with ostomies.

Implicaciones prácticas de la Guía Internacional de Ostomía WCET® 2020

Laurent O. Chabal, Jennifer L. Prentice and Elizabeth A. Ayello

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.2.10-21

Resumen

La segunda edición de la Guía Internacional de Ostomía (IOG) WCET® se lanzó en diciembre de 2020 como una actualización de la directriz original publicada en 2014. El objetivo de este artículo es presentar las 15 recomendaciones que abarcan cuatro ámbitos clave (educación, aspectos holísticos y cuidados pre y postoperatorios) y resumir los conceptos clave para que los clínicos los personalicen para trasladarlos a su práctica. El artículo también incluye información sobre el impacto del nuevo coronavirus 2019 en el cuidado de la ostomía.

Agradecimientos

El WCET® desea agradecer a todos los revisores y organizaciones que aportaron comentarios y contribuciones a la Guía Internacional de Ostomía 2020. Aunque el WCET® agradece la subvención educativa recibida de Hollister para apoyar el desarrollo de la IOG 2020, la directriz es el único trabajo independiente del WCET® y no fue influenciado de ninguna manera por la compañía que proporcionó la subvención educativa sin restricciones.

Los autores, el profesorado, el personal y los planificadores, incluidos los cónyuges/parejas (si los hay), que estén en condiciones de controlar el contenido de esta actividad de CME/NCPD han declarado que no tienen relaciones ni intereses financieros en ninguna empresa comercial relacionada con esta actividad educativa.

Para obtener créditos CME, debe leer el artículo CME y completar el cuestionario en línea, respondiendo correctamente al menos a 7 de las 10 preguntas. Esta actividad de formación continua expirará para los médicos el 31 de mayo de 2023, y para los enfermeros el 3 de junio de 2023. Todas las pruebas son ahora sólo en línea; haga la prueba en http://cme.lww.com para médicos y en www.NursingCenter.com/CE/ASWC para enfermeros. La información completa sobre NCPD/CME se encuentra en la última página de este artículo.

© Avances en la atención de la piel y heridas y el Consejo Mundial de Terapeutas Enterostomales

Introduccion

Las directrices son documentos vivos y dinámicos que necesitan ser revisados y actualizados, normalmente cada 5 años, para mantenerse al día con las nuevas pruebas. Por lo tanto, en diciembre de 2020, el Consejo Mundial de Terapeutas Enterostomales® (WCET®) publicó la segunda edición de su Guía Internacional de Ostomía (IOG).1 La IOG 2020 se basa en la directriz inicial de la IOG publicada en 2014.2 Cientos de referencias proporcionaron la base para la búsqueda de artículos publicados desde mayo de 2013 hasta diciembre de 2019. La directriz utiliza varios términos reconocidos internacionalmente para indicar a los proveedores que tienen conocimientos especializados en el cuidado de la ostomía, incluidos los enfermeros y clínicos de TE/estoma/ostomía.1 Sin embargo, a efectos de este artículo, los autores utilizarán “clínicos de ostomía” y “persona con ostomía” para ser coherentes.

Desarrollo de directrices

Una descripción detallada de la metodología de las directrices de la IOG 2020 puede encontrarse en otro lugar.1 Brevemente, el proceso incluyó una búsqueda de la literatura publicada en inglés desde mayo de 2013 hasta diciembre de 2019 por parte de los autores de este artículo, que conforman el Panel de Desarrollo de Directrices. Se revisaron más de 340 artículos. Para cada artículo identificado, un miembro del panel escribiría un resumen, y los tres confirmarían o revisarían la clasificación de las pruebas del artículo. Las pruebas se clasificaron y definieron y se recopilaron en una tabla que se incluye en la directriz y a la que se puede acceder en el sitio web WCET®. La fuerza de las recomendaciones se calificó mediante un sistema alfabético (A+, A, A-, etc.). Se buscó la opinión de la comunidad mundial de ostomía, y se invitó a 146 personas y 45 organizaciones a comentar los resultados. De ellos, 104 personas y 22 organizaciones enviaron comentarios, que se utilizaron para finalizar la directriz.

Resumen de la directriz

Dado que el WCET® es una asociación internacional con miembros en más de 65 países, se hace hincapié en la diversidad de culturas, religiones y niveles de recursos, de modo que la IOG 2020 pueda aplicarse tanto en países con abundantes recursos como en los que tienen dificultades. El prólogo fue escrito por el Dr. Larry Purnell, autor del Modelo Purnell para la Competencia Cultural (inconscientemente incompetente, conscientemente incompetente, conscientemente competente, inconscientemente competente).3-5 Al igual que con la directriz de 2014, se invitó a los miembros del WCET® y a los delegados internacionales a presentar informes culturales de su país, y se recibieron 22, que se incorporaron al desarrollo de la directriz.

Dado que la IOG 2020 pretende servir de guía para los clínicos en la prestación de cuidados a personas con una ostomía, la novedad de esta edición es una sección sobre la aplicación de las directrices. También es nueva una recomendación para la enseñanza de la enfermería. También se incluye un glosario de términos y recursos educativos útiles en los distintos apéndices. Las 15 recomendaciones de la IOG 2020 se enumeran en el Tabla 1. Las recomendaciones se han traducido al chino (Tabla Suplementaria 1), al francés (Tabla Suplementaria 2), al portugués (Tabla Suplementaria 3) y al español (Tabla Suplementaria 4) y también están disponibles en el sitio web WCET® (www.wcetn.org).

Tabla 1 Recomendaciones de la Guía Internacional de Ostomía WCET® 2020

Educación

Las pruebas apoyan cuatro recomendaciones de la IOG 2020 sobre educación (Tabla 1). Una persona que se somete a una intervención quirúrgica que da lugar a la creación de una ostomía necesita conocimientos sobre su tipo de estoma, las estrategias de cuidado, como las bolsas de ostomía, y el impacto que tendrá la ostomía en su estilo de vida.6 En consecuencia, las necesidades de estos pacientes van más allá de lo que se puede enseñar en los programas de formación inicial de enfermería. Zimnicki y Pieper7 encuestaron a estudiantes de enfermería y descubrieron que algo menos de la mitad (47,8%) no tenía experiencia en el cuidado de un paciente con una ostomía. Los que lo hicieron, se sintieron más seguros en el vaciado de la bolsa.7 Los hallazgos de Cross y sus colegas8 también apoyan que el personal de enfermería sin formación especializada en ostomía se sentía más seguro en el vaciado de la bolsa de ostomía en comparación con otras habilidades del cuidado de la ostomía. Duruk y Uçar9 en Turquía y Li y sus colegas10 en China también revelan que el personal de enfermería carece de conocimientos adecuados sobre el cuidado de los pacientes con ostomías. Se han observado mejores resultados en el cuidado de la ostomía cuando los pacientes son atendidos por personal de enfermería con formación especializada en ostomías. Esto incluye investigaciones realizadas en España por Coca y sus colegas,11 en Japón por Chikubu y Oike,12 y en el Reino Unido por Jones.13

Durante más de 40 años, el WCET® ha promovido la importancia de la formación especializada en ostomías para los enfermeros con el fin de satisfacer mejor las necesidades de los pacientes y sus familias.6 Otras sociedades, como la Wound Ostomy and Continence Nursing Society de EE.UU., la Nurses Specialised in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada y la Association of Stoma Care Nurses del Reino Unido, también han abogado por una formación de enfermería especializada. Las modificaciones sugeridas incluyen planes de estudios basados en la competencia y listas de comprobación de las habilidades y el rendimiento profesional necesarios para que el enfermero especializado proporcione los cuidados adecuados a los pacientes con una ostomía y a sus familias.14-17 La práctica basada en la evidencia requiere que los profesionales sanitarios se mantengan al día de las nuevas técnicas, habilidades y conocimientos; es necesario el aprendizaje permanente.

Aspectos holísticos de la atención: cultura y religión

La literatura respalda tres recomendaciones altamente clasificadas relacionadas con el cuidado holístico dentro de la IOG 2020 (Tabla 1) y confirma la necesidad de tenerlas en cuenta cuando se atiende a personas con una ostomía.

Las ostomías pueden afectar a las personas en diferentes ámbitos, como la vida cotidiana, la calidad de vida en general, las relaciones sociales, el trabajo, la intimidad y la autoestima. Un enfoque holístico de la atención pretende reconocer y abordar la necesidad del paciente a nivel fisiológico, psicológico, sociológico, espiritual y cultural,18 especialmente cuando la situación del paciente es compleja.19 Por lo tanto, la aplicación de un enfoque holístico en la práctica es crucial para abordar todos los posibles problemas.20

Existen muchas herramientas para evaluar la calidad de vida de los pacientes, la adaptación al autocuidado, la adaptación social y/o el estado psicológico.21,22 Proporcionan información importante a los enfermeros en su toma de decisiones clínicas, aunque como siempre el juicio clínico sigue siendo relevante. Dado que la atención holística es multidimensional, el uso de varios métodos permitirá un enfoque integrador y global de la atención a los pacientes con ostomías.

La definición de salud de la Organización Mundial de la Salud23 sigue siendo pertinente hoy en día. Los orígenes, las creencias, la religión, la cultura, el género y la edad de un individuo influirán en su interpretación de la enfermedad y las dolencias.24-26 Para los profesionales sanitarios, la necesidad de comprender estas influencias y sus impactos reales en el paciente, la familia y/o el/los cuidador/es es esencial porque proporcionará información clave para co-construir el cuidado de la ostomía.

El modelo de competencia cultural del Dr. Larry Purnell3,4 puede aplicarse fácilmente al cuidado de la ostomía.5 Puede ayudar al personal de enfermería a proporcionar cuidados culturalmente competentes a los pacientes con una ostomía. La integración de una competencia cultural efectiva mejorará las relaciones entre los pacientes, las familias y los profesionales sanitarios,27 especialmente si los pacientes y/o las familias tienen dificultades para afrontar la situación.28

Los enfermeros esecializados y no especializados tienen un papel clave en la educación del paciente, la familia y los cuidadores.29 Ellos, paso a paso, ayudarán a apoyar el desarrollo de habilidades específicas y la implementación de estrategias de adaptación personalizadas. Los consejos y el apoyo de los enfermeros pueden reducir las complicaciones relacionadas con la ostomía,13,30,31 y escuchar y abordar las emociones de los pacientes mejorará el autocuidado de las personas.32

Tener en cuenta la Carta Internacional de los Derechos de los Ostomizados33 durante la prestación del cuidado de la ostomía aumentará la calidad de vida de los pacientes, ya que apoya el empoderamiento del paciente y refuerza las asociaciones entre pacientes, familias, cuidadores y profesionales sanitarios.

La sección 6 de la IOG 2020 ofrece una perspectiva internacional sobre los cuidados de ostomía. Con contribuciones de 22 países, esta versión es más inclusiva que la anterior.2 Los autores esperan que ayude a los clínicos de ostomía de todo el mundo cuando atiendan a pacientes de otra cultura, origen o sistema de creencias y, por tanto, les proporcione mejores habilidades para atender las necesidades de cada individuo.

Cuidados preoperatorios y marcado del sitio del estoma

Como se ve en la Tabla 1, hay cuatro recomendaciones que abordan los cuidados preoperatorios y el marcado del sitio del estoma. La bibliografía hace hincapié en la educación preoperatoria de los pacientes que van a someterse a una cirugía de ostomía, que incluye el marcado preoperatorio del lugar. Se observan menos complicaciones en las personas que tienen sus sitios del estoma marcados antes de la cirugía.34,35

Dado que el personal de enfermería especializado puede no estar disponible las 24 horas del día ,7 días a la semana , los pacientes que se someten a una intervención quirúrgica no planificada/urgente pueden no beneficiarse de la educación preoperatoria y del marcado del sitio del estoma. En consecuencia, la bibliografía respalda la formación de médicos y enfermeros no especializados para realizar el marcado del sitio del estoma.34-37 Zimnicki36 llevó a cabo un proyecto de mejora de la calidad para formar a enfermeros no especializados en el marcado del sitio del estoma. Este proyecto aumentó significativamente el número de pacientes que se sometieron al marcado y educación preoperatoria del sitio del estoma.36

El marcado del sitio del estoma es un arte y una habilidad importantes que está más allá del alcance de este artículo para describir en detalle. Los principios más importantes incluyen la observación del abdomen del paciente de pie, sentado, agachado y tumbado (figura 1).37-41 Existen al menos dos técnicas para identificar la localización abdominal ideal.42-52 Los interesados pueden consultar las referencias42-60, así como el seminario web WCET® o la guía de bolsillo sobre el marcado del sitio del estoma (www.wcetn.org).52

Figura 1 posiciones para el marcado del sitio del estoma ©2021 Ayello, utilizado con permiso.

Cuidados postoperatorios

La IOG 2020 enumera cuatro recomendaciones para los cuidados postoperatorios con el fin de ayudar a los clínicos especialistas en ostomías a detectar, prevenir o gestionar y, por tanto, minimizar el efecto de cualquier complicación periestomal (Tabla 1).

El éxito de la recuperación postoperatoria tras la cirugía de ostomía depende de múltiples factores, tanto desde la perspectiva del clínico como de la persona ostomizada. Todos los miembros del equipo asistencial, incluido el paciente, deben tener una mayor conciencia de las estrategias preventivas o correctivas para los problemas comunes que pueden ocurrir con la formación de un nuevo estoma, la remodelación de un estoma existente o el cierre del estoma. La capacidad de reconocer y gestionar eficazmente las complicaciones postoperatorias potenciales o reales de la ostomía y las complicaciones cutáneas periestómicas (PSCs) tiene ramificaciones inherentes a corto y largo plazo para la salud, el bienestar y la independencia de las personas con una ostomía61-63 y para la gestión de los recursos sanitarios.64-66

Las complicaciones postoperatorias de la ostomía pueden manifestarse como presentaciones tempranas o tardías. Las complicaciones tempranas, como la separación mucocutánea, la retracción, la necrosis estomal, el absceso paraestomal o la dermatitis, pueden aparecer en los 30 días siguientes a la cirugía. Entre las complicaciones posteriores se encuentran las hernias paraestomales (PHs) y el prolapso, la retracción o la estenosis.63,67,68

Sin embargo, las complicaciones postoperatorias más comunes son las PSC.69 Las causas citadas con frecuencia de las PSC son las fugas,70,71 la falta de ubicación preoperatoria del estoma,35 las técnicas de construcción quirúrgica deficientes,72 los aparatos mal ajustados y el largo tiempo de uso de los aparatos.71,73

Entre las PSC más comunes se encuentran la dermatitis de contacto irritante aguda y crónica y la dermatitis de contacto alérgica, la primera de las cuales surge del contacto prolongado con heces u orina en la piel que acaba provocando una erosión (Figura 2). La evaluación del abdomen, el estoma, el aparato de estoma y los accesorios en uso, así como la capacidad del paciente para cuidar el estoma y reaplicar correctamente su aparato, es esencial para determinar la causa de las fugas. El cuidado de la piel, dependiendo de la gravedad de la irritación o la denudación, puede implicar el uso de polvos o pastas protectoras a base de pectina, selladores de la piel (toallitas o sprays de copolímero de acrilato o cianoacrilatos) y barreras cutáneas protectoras. También puede ser necesario ajustar el tipo de aparato utilizado y el tiempo de uso para mejorar la dermatitis de contacto irritante aguda y prevenir la crónica.61,70,74

Figura 2 dermatitis irritante ©2021 Chabal, utilizado con permiso.

La dermatitis alérgica de contacto es el resultado de una reacción adversa a las sustancias de los productos aplicados a la piel durante la limpieza o la protección de la piel utilizados antes de la aplicación o retirada del aparato o de partes que forman parte del mismo.74,75 La piel comprometida suele reflejar la forma del aparato si es el alérgeno o la zona en la que se han utilizado productos secundarios para el cuidado de la piel. La piel afectada puede tener el aspecto de una erupción, estar enrojecida, con ampollas, con picor o dolor, o exudar líquido hemático (Figura 3). Puede ser necesario realizar pruebas de parche en pequeñas zonas de la piel bien alejadas de la piel comprometida y del estoma para identificar agentes causales específicos y/o evaluar la idoneidad de otros productos de barrera cutánea utilizados para conseguir un sellado seguro alrededor del estoma.70,75

Figura 3 Dermatitis alérgica de contacto ©2021 Chabal, utilizado con permiso.

Las hernias paraestomales son una complicación latente que también contribuye a las PSC. Las causas incluyen la técnica quirúrgica, el tamaño y el tipo de estoma, el perímetro abdominal y la edad y las condiciones médicas, como las hernias anteriores y el líquido de la diverticulitis. La educación de los cirujanos y la inserción profiláctica de la malla de polipropileno durante la cirugía, así como la educación postoperatoria del paciente, pueden disminuir la incidencia de la HP (Figura 4).68,76,77 Además, los proveedores deben evaluar y medir el abdomen del paciente a nivel del estoma para elegir la prenda de soporte más adecuada para controlar el grado de protrusión de la HP, prevenir una mayor exacerbación y permitir que el estoma siga funcionando normalmente.78 El aparato/bolsa de ostomía en uso también necesitará ser reevaluado con frecuencia para abordar cualquier cambio en el tamaño del estoma.

Figura 4 hernia parastomal ©2021 Chabal, utilizado con permiso.

La IOG 2020 cita numerosas herramientas que los clínicos de ostomía pueden utilizar para identificar y clasificar eficazmente las PSC79,80,81 y seleccionar las barreras cutáneas y los aparatos adecuados para manejar las PSC.62,82

Por último, para mejorar la calidad de vida postoperatoria de las personas con una ostomía, reducir las complicaciones de la ostomía y los reingresos asociados, y mejorar la práctica interprofesional, es cada vez más importante el uso de programas de recuperación temprana o mejorada después de la cirugía,83,84 la educación continua y los programas de seguimiento al alta,68,85 y las modalidades de telesalud para el asesoramiento y la consulta a distancia.86,87

Aplicación de las directrices

Para que las directrices clínicas tengan resultados positivos para las poblaciones de pacientes a las que van dirigidas, es necesario que las recomendaciones propuestas se adopten en la práctica diaria. Se necesitan múltiples estrategias para facilitar la adopción88,89 y las directrices deben ser revisadas y adaptadas a contextos clínicos específicos.90 Por lo tanto, es necesario reflexionar previamente sobre cómo se difundirán y aplicarán las directrices. Los posibles obstáculos para la aplicación de las directrices pueden ser la falta de recursos, la existencia de agendas sanitarias contrapuestas o la percepción de una falta de interés en el cuidado de la ostomía como subespecialidad médica/de enfermería sin un “campeón” que defienda y facilite la aplicación. Por último, las directrices pueden considerarse demasiado prescriptivas. La sección sobre la aplicación de la directriz dentro de la IOG 2020 ofrece consejos, y los lectores son dirigidos a la directriz completa para obtener más información.

Impacto de la covid-19 en el cuidado de la ostomía

La revisión de las pruebas de la IOG 2020 precedió a la llegada del nuevo coronavirus 2019. Durante la pandemia, ha habido informes anecdóticos de clínicos de ostomía que han sido reasignados para atender a otros pacientes. Todavía no se ha investigado el alcance y el impacto de esta situación. Mientras tanto, las visitas virtuales pueden proporcionar una alternativa segura a la atención en persona para pacientes y proveedores.91 Un estudio realizado por White y sus colegas92 informó sobre la viabilidad de las visitas virtuales para personas con nuevas ostomías; el 90% de los pacientes consideraron que estas visitas eran útiles para el manejo de su ostomía.92 Sin embargo, otro estudio descubrió que sólo el 32% de los encuestados sabía que la telesalud era una opción.93 Además, el 71% “no creía que [su problema] fuera lo suficientemente grave como para buscar ayuda de un profesional sanitario”,93 aunque el 57% informó de alguna aparición de piel periestomal durante la pandemia.93 En orden descendente, los tipos de problemas de la piel notificados fueron enrojecimiento o sarpullido (79%), picor (38%), piel abierta (21%), sangrado (19%) y otros problemas (7%).93

Conclusiones

La IOG 2020 tiene como objetivo proporcionar a los clínicos un marco de evidencia en el que basar su práctica. Las 15 recomendaciones de la IOG 2020 son aplicables tanto en países donde los recursos son abundantes (enfermeras y profesionales sanitarios formados en el cuidado de la ostomía con aparatos/bolsas fabricados), como en países con recursos limitados (enfermeros no especializados, profesionales sanitarios y laicos que crean equipos de ostomía con los recursos locales disponibles para contener el efluente de la ostomía). Se necesitan conocimientos especializados para ayudar a las personas con una ostomía a aprender a colocar, vaciar y cambiar su aparato/bolsa, pero vivir con una ostomía es más que eso. Hay que tener en cuenta todos los aspectos del paciente.

La atención holística del paciente debe ser individualizada y abordar la dieta, las actividades de la vida diaria, la vida sexual, la oración, el trabajo, los medicamentos, la imagen corporal y otras preocupaciones centradas en el paciente. La ubicación preoperatoria del estoma se ha relacionado con mejores resultados postoperatorios. La identificación e intervención tempranas de las PSC requiere una enseñanza adecuada, así como saber cuándo buscar ayuda profesional. Los enfermeros con conocimientos especializados en el cuidado de las ostomías pueden mejorar la calidad de vida de las personas con una ostomía, incluidas las que experimentan PSC.95 Los autores esperan que la IOG 2020 mejore los resultados de los cuidados y la rehabilitación de esta población.

Lecciones practicas

- Los pacientes atendidos por profesionales sanitarios con conocimientos especializados en ostomías obtienen mejores resultados asistenciales.

- Existen herramientas clínicas que ayudan a evaluar la piel periestomal y los requisitos de los aparatos.

- La educación pre y postoperatoria del paciente y su familia debe ser integral e individualizada.

- Los pacientes que se someten a la colocación prequirúrgica del estoma experimentan menos complicaciones.

- La PSC más común es la fuga que conduce a la dermatitis irritante.

- La telesalud y la consulta a distancia podrían ser ventajosas para proporcionar orientación complementaria a las personas con ostomías.

Author(s)

Laurent O. Chabal*

BSc (CBP), RN, OncPall (Cert), Dip (WH), ET, EAWT

Specialised Stoma Nurse, Ensemble Hospitalier de la Côte—Morges’ Hospital; Lecturer, Geneva School of Health Sciences, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Western Switzerland; and President Elect, WCET® 2020-2022

Jennifer L. Prentice

PhD, RN, STN, FAWMA

WCET® Journal Editor; Nurse Specialist Wound Skin Ostomy Service Hall & Prior Health and Aged Care Group, Perth, Western Australia

Elizabeth A. Ayello

PhD, MS, BSN, ETN, RN, CWON, MAPCWA, FAAN

Co-Editor in Chief, Advances in Skin and Wound Care;

President, Ayello, Harris & Associates, Copake, New York;

WCET® President, 2018-2022; WCET® Executive Journal Editor Emerita, Perth, Western Australia; and Faculty Emerita, Excelsior College School of Nursing, Albany, New York

* Corresponding author

References

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® International Ostomy Guideline. Chabal LO, Prentice JL, Ayello EA, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET®; 2020.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists® International Ostomy Guideline. Zulkowski K, Ayello EA, Stelton S, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET®; 2014.

- Purnell L. Transcultural health care: a culturally competent approach. Philadelphia: F A Davis Co; 2013.

- Purnell L. Guide to culturally competent health care. Philadelphia: F A Davis Co; 2014.

- Purnell L. The Purnell Model applied to ostomy and wound care. WCET J 2014;34(3):11-8.

- Gill-Thompson SJ. Forward to second edition. In: Erwin-Toth P, Krasner DL, eds. Enterostomal Therapy Nursing. Growth & Evolution of a Nursing Specialty Worldwide. A Festschrift for Norma N. Gill-Thompson ET. 2nd ed. Perth, Western Australia: Cambridge Publishing; 2020;10-1.

- Zimnicki K, Pieper B. Assessment of prelicensure undergraduate baccalaureate nursing students: ostomy knowledge, skill experiences, and confidence in care. Ostomy Wound Manage 2018;64(8):35-42.

- Cross HH, Roe CA, Wang D. Staff nurse confidence in their skills and knowledge and barriers to caring for patients with ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41(6):560-5.

- Duruk N, Uçar H. Staff nurses’ knowledge and perceived responsibilities for delivering care to patients with intestinal ostomies. A cross-sectional study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;40(6):618-22.

- Li, Deng B, Xu L, Song X, Li X. Practice and training needs of staff nurses caring for patients with intestinal ostomies in primary and secondary hospital in China. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(5):408-12.

- Coca C, Fernández de Larrinoa I, Serrano R, García-Llana H. The impact of specialty practice nursing care on health-related quality of life in persons with ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(3):257-63.

- Chikubu M, Oike M. Wound, ostomy and continence nurses competency model: a qualitative study in Japan. J Nurs Healthc 2017;2(1):1-7.

- Jones S. Value of the Nurse Led Stoma Care Clinic. Cwm Taf Health Board, NHS Wales. 2015. www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/research-and-innovation/innovation-in-nursing/~/-/media/b6cd4703028a40809fa99e5a80b2fba6.ashx. Last accessed March 4, 2021.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. ETNEP/REP Recognition Process Guideline. 2017. https://wocet.memberclicks.net/assets/Education/ETNEP-REP/ETNEP%20REP%20Guidelines%20Dec%202017.pdf. Last accessed March 4, 2021.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. WCET Checklist for Stoma REP Content. 2020. www.wcetn.org/assets/Education/wcet-rep%20stoma%20care%20checklist-feb%2008.pdf. Last accessed March 4, 2021.

- Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, Guideline Development Task Force. WOCN Society clinical guideline: management of the adult patient with a fecal or urinary ostomy-an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2018;45(1):50-8.

- Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society Task Force. Wound, ostomy, and continence nursing: scope and standards of WOC practice, 2nd edition: an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2018;45(4):369-87.

- Wallace S. The Importance of holistic assessment—a nursing student perspective. Nuritinga 2013;12:24-30.

- Perez C. The importance of a holistic approach to stoma care: a case review. WCET J 2019;39(1):23-32.

- The importance of holistic nursing care: how to completely care for your patients. Practical Nursing. October 2020. www.practicalnursing.org/importance-holistic-nursing-care-how-completely-care-patients. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Knowles SR, Tribbick D, Connell WR, Castle D, Salzberg M, Kamm MA. Exploration of health status, illness perceptions, coping strategies, psychological morbidity, and quality of life in individuals with fecal ostomies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(1):69-73.

- Vural F, Harputlu D, Karayurt O, et al. The impact of an ostomy on the sexual lives of persons with stomas—a phenomenological study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(4):381–4.

- World Health Organization. What is the WHO definition of health? www.who.int/about/who-we-are/frequently-asked-questions. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Baldwin CM, Grant M, Wendel C, et al. Gender differences in sleep disruption and fatigue on quality of life among persons with ostomies. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5(4):335-43.

- World Health Organization. Gender, equity and human rights. 2020. www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/indigenous-peoples/en. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Forest-Lalande L. Best-practice for stoma care in children and teenagers. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2019;17(S5):S12-3.

- Qader SAA, King ML. Transcultural adaptation of best practice guidelines for ostomy care: pointers and pitfalls. Middle East J Nurs 2015;9(2):3-12.

- Iqbal F, Kujan O, Bowley DM, Keighley MRB, Vaizey CJ. Quality of life after ostomy surgery in Muslim patients—a systematic review of the literature and suggestions for clinical practice. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(4):385-91.

- Merandy K. Factors related to adaptation to cystectomy with urinary diversion. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(5):499-508.

- de Gouveia Santos VLC, da Silva Augusto F, Gomboski G. Health-related quality of life in persons with ostomies managed in an outpatient care setting. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;43(2):158-64.

- Ercolano E, Grant M, McCorkle R, et al. Applying the chronic care model to support ostomy self-management: implications for oncology nursing practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2016;20(3):269-74.

- Xu FF, Yu Wh, Yu M, Wang SQ, Zhou GH. The correlation between stigma and adjustment in patients with a permanent colostomy in the midlands of China. WCET J 2019;39(1):24-39.

- International Ostomy Association. Charter of Ostomates Rights. www.ostomyinternational.org/about-us/charter.html. Last accessed March 2, 2021.

- Watson AJM, Nicol L, Donaldson S, Fraser C, Silversides A. Complications of stomas: their aetiology and management. Br J Community Nurs 2013;18(3):111-2, 114, 116.

- Baykara ZG, Demir SG, Ayise Karadag A, et al. A multicenter, retrospective study to evaluate the effect of preoperative stoma site marking on stomal and peristomal complications. Ostomy Wound Manage 2014;60(5):16-26.

- Zimnicki KM. Preoperative teaching and stoma marking in an inpatient population: a quality improvement process using a FOCUS-Plan-Do-Check-Act Model. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(2):165-9.

- WOCN Committee Members, ASCRS Committee Members. ASCRS and WOCN joint position statement on the value of preoperative stoma marking for patients undergoing fecal ostomy surgery. JWOCN 2007;34(6):627-8.

- Salvadalena G, Hendren S, McKenna L, et al. WOCN Society and ASCRS position statement on preoperative stoma site marking for patients undergoing colostomy or ileostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(3):249-52.

- Salvadalena G, Hendren S, McKenna L, et al. WOCN Society and AUA position statement on preoperative stoma site marking for patients undergoing urostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2015;42(3):253-6.

- Brooke J, El-GHaname A, Napier K, Sommerey L. Executive summary: Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada (NSWOCC) nursing best practice recommendations. Enterocutaneous fistula and enteroatmospheric fistula. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(4):306-8.

- Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada. Nursing Best Practice Recommendations: Enterocutaneous Fistulas (ECF) and Enteroatmospheric Fistulas (EAF). 2nd ed. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada; 2018.

- Serrano JLC, Manzanares EG, Rodriguez SL, et al. Nursing intervention: stoma marking. WCET J 2016;36(1):17-24.

- Fingren J, Lindholm E, Petersén C, Hallén AM, Carlsson E. A prospective, explorative study to assess adjustment 1 year after ostomy surgery among Swedish patients. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;64(6):12-22.

- Rust J. Complications arising from poor stoma siting. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2011;9(5):17-22.

- Watson JDB, Aden JK, Engel JE, Rasmussen TE, Glasgow SC. Risk factors for colostomy in military colorectal trauma: a review of 867 patients. Surgery 2014;155(6):1052-61.

- Banks N, Razor B. Preoperative stoma site assessment and marking. Am J Nurs 2003;103(3):64A-64C, 64E.

- Kozell, K, Frecea M, Thomas JT. Preoperative ostomy education and stoma site marking. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2014;41(3):206-7.

- Readding LA. Stoma siting: what the community nurse needs to know. Br J Community Nurs 2003;8(11):502-11.

- Cronin E. Stoma siting: why and how to mark the abdomen in preparation for surgery. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2014;12(3):12-9.

- Chandler P, Carpenter J. Motivational interviewing: examining its role when siting patients for stoma surgery. Gastrointestinal Nurs 2015;13(9):25-30.

- Pengelly S, Reader J, Jones A, Roper K, Douie WJ, Lambert AW. Methods for siting emergency stomas in the absence of a stoma therapist. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2014;96:216-8.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. Guide to Stoma Site Marking. Crawshaw A, Ayello EA, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET; 2018.

- Mahjoubi B, Goodarzi K, Mohannad-Sadeghi H. Quality of life in stoma patients: appropriate and inappropriate stoma sites. World J Surg 2009;34:147-52.

- Person B, Ifargan R, Lachter J, Duek SD, Kluger Y, Assalia A. The impact of preoperative stoma site marking on the incidence of complications, quality of life, and patient’s independence. Dis Colon Rect 2012;55(7):783-7.

- American Society of Colorectal Surgeons Committee, Wound Ostomy Continence Nurses Society® Committee. ASCRS and WOCN® joint position statement on the value of preoperative stoma marking for patients undergoing fecal ostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2007;34(6):627-8.

- AUA and WOCN® Society joint position statement on the value of preoperative stoma marking for patients undergoing creation of an incontinent urostomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009;36(3):267-8.

- Cronin E. What the patient needs to know before stoma siting: an overview. Br J Nurs 2012;21(22):1304, 1306-8.

- Millan M, Tegido M, Biondo S, Garcia-Granero E. Preoperative stoma siting and education by stomatherapists of colorectal cancer patients: a descriptive study in twelve Spanish colorectal surgical units. Colorectal Dis 2010;12(7 Online):e88-92.

- Batalla MGA. Patient factors, preoperative nursing Interventions, and quality of life of a new Filipino ostomates. WCET J 2016;36(3):30-8.

- Danielsen AK, Burcharth J, Rosenberg J. Patient education has a positive effect in patients with a stoma: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 2013;15(6):e276-83.

- Stelton S, Zulkowski K, Ayello EA. Practice implications for peristomal skin assessment and care from the 2014 World Council of Enterostomal Therapists International Ostomy Guideline. Adv Skin Wound Care 2015;28(6):275-84.

- Colwell JC, Bain KA, Hansen AS, Droste W, Vendelbo G, James-Reid S. International consensus results. Development of practice guidelines for assessment of peristomal body and stoma profiles, patient engagement, and patient follow-up. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(6):497-504.

- Maydick-Youngberg D. A descriptive study to explore the effect of peristomal skin complications on quality of life of adults with a permanent ostomy. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(5):10-23.

- Nichols TR, Inglese GW. The burden of peristomal skin complications on an ostomy population as assessed by health utility and their physical component: summary of the SF-36v2®. Value Health 2018;21(1):89-94.

- Neil N, Inglese G, Manson A, Townshend A. A cost-utility model of care for peristomal skin complications. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2016;34(1):62.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad BS, Inglese G, Eaves D, Oster G. Risk and economic burden of peristomal skin complications following ostomy surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(2):143-9.

- Koc U, Karaman K, Gomceli I, et al. A retrospective analysis of factors affecting early stoma complications. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(1):28-32.

- Hendren S, Hammond K, Glasgow SC, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for ostomy surgery. J Dis Colon Rectum 2015;58:375-87.

- Roveron G. An analysis of the condition of the peristomal skin and quality of life in ostomates before and after using ostomy pouches with manuka honey. WCET J 2017;37(4):22-5.

- Stelton S. Stoma and peristomal skin care: a clinical review. Am J Nurs 2019;119(6):38-45.

- Recalla S, English K, Nazarali R, Mayo S, Miller D, Gray M. Ostomy care and management a systematic review. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;40(5):489-500.

- Carlsson E, Fingren J, Hallen A-M, Petersen C, Lindholm E. The prevalence of ostomy-related complications 1 year after ostomy surgery: a prospective, descriptive, clinical study. Ostomy Wound Manage 2016;62(10):34-48.

- Steinhagen E, Colwell J, Cannon LM. Intestinal stomas—postoperative stoma care and peristomal skin complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2017;30(3):184-92.

- World Council of Enterostomal Therapists®. WCET Ostomy Pocket Guide: Stoma and Peristomal Problem Solving. Ayello EA, Stelton S, eds. Perth, Western Australia: WCET, 2016.

- Cressey BD, Belum VR, Scheinman P, et al. Stoma care products represent a common and previously underreported source of peristomal contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 2017;76(1):27-33.

- Tabar F, Babazadeh S, Fasangari Z, Purnell P. Management of severely damaged peristomal skin due to MARSI. WCET J 2017;37(1):18.

- Taneja C, Netsch D, Rolstad BS, Inglese G, Lamerato L, Oster G. Clinical and economic burden of peristomal skin complications in patients with recent ostomies. J Wound, Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(4):350.

- Association Stoma Care Nurses. ASCN Stoma Care National Clinical Guidelines. London, England: ASCN UK; 2016.

- Herlufsen P, Olsen AG, Carlsen B, et al. Study of peristomal skin disorders in patients with permanent stomas. Br J Nurs 2006;15(16):854-62.

- Ay A, Bulut H. Assessing the validity and reliability of the peristomal skin lesion assessment instrument adapted for use in Turkey. Ostomy Wound Manage 2015;61(8):26-34.

- Runkel N, Droste W, Reith B, et al. LSD score. A new classification system for peristomal skin lesions. Chirurg 2016;87:144-50.

- Buckle N. The dilemma of choice: introduction to a stoma assessment tool. GastroIntestinal Nurs 2013;11(4):26-32.

- Miller D, Pearsall E, Johnston D, et al. Executive summary: enhanced recovery after surgery best practice guideline for care of patients with a fecal diversion. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(1):74-7.

- Hardiman KM, Reames CD, McLeod MC, Regenbogen SE. A patient-autonomy-centered self-care checklist reduces hospital readmissions after ileostomy creation. Surgery 2016;160(5):1302-8.

- Harputlu D, Özsoy SA. A prospective, experimental study to assess the effectiveness of home care nursing on the healing of peristomal skin complications and quality of life. Ostomy Wound Manage 2018;64(10):18-30.

- Iraqi Parchami M, Ahmadi Z. Effect of telephone counseling (telenursing) on the quality of life of patients with colostomy. JCCNC 2016;2(2):123-30.

- Xiaorong H. Mobile internet application to enhance accessibility of enterostomal therapists in China: a platform for home care. WCET J 2016;36(2):35-8.

- Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM. Selecting, presenting, and delivering clinical guidelines: are there any “magic bullets”. Med J Aust 2004;180(6 Suppl):S52-4.

- Rauh S, Arnold D, Braga S, et al. Challenge of implementing clinical practice guidelines. Getting ESMO’s guidelines even closer to the bedside: introducing the ESMO Practising Oncologists’ checklists and knowledge and practice questions. ESMO Open 2018;3:e000385.

- Fletcher J, Kopp P. Relating guidelines and evidence to practice. Prof Nurse 2001;16:1055-9.

- Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa P, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. JAMIA 2020;27(7):1132-5.

- White T, Watts P, Morris M, Moss J. Virtual postoperative visits for new ostomates. CIN 2019;37(2):73-9.

- Spencer K, Haddad S, Malanddrino R. COVID-19: impact on ostomy and continence care. WCET J 2020;40(4):18-22.

- Russell S. Parastomal hernia: improving quality of life, restoring confidence and reducing fear. The importance of the role of the stoma nurse specialist. WCET J 2020;40(4):36-9.