Volume 43 Number 1

Fact-finding survey of pressure and shear force at the heel using a three-axis tactile sensor

Yoko Murooka and Hidemi Nemoto Ishii

Keywords heel pressure injury, decompression, shear force, elevating the head of the bed

For referencing Murooka Y and Ishii HN. Fact-finding survey of pressure and shear force at the heel using a three-axis tactile sensor. WCET® Journal 2023;43(1):20-27

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.1.20-27

Submitted 28 March 2022

Accepted 31 August 2022

Abstract

Aims We investigated changes in pressure and shear force at the heel caused by elevating the head of the bed and after offloading pressure from the heel.

Methods Data on heel pressure and shear force were collected from 26 healthy individuals aged >30 years using a three-axis tactile sensor at each angle formed as the participants’ upper bodies were raised from a supine position. Data after pressure release of either the left or right foot were collected and compared.

Results The participants’ mean age was 45.1 (±11.1) years. Pressure and anteroposterior shear force on the heel increased with elevation. These increases were especially prominent when the angle of elevation was 30˚. In the subsequent 45˚ and 60˚ tilts, body pressure and shear force increased slightly but not significantly. Pressure and shear force were released by elevating the lower extremity each time the head of the bed was elevated. However, further elevations resulted in increased pressure and shear force, particularly lateral shear force. Pressure and shear force did not change significantly when the lower limbs were elevated.

Conclusion The recommended elevation of the bed head to no more than 30˚ yielded major changes. Elevating the leg relieved the heel of continuous pressure and shear force while increasing pressure and lateral shear force. Although leg elevation is an aspect of daily nursing care, it is important to investigate such nursing interventions using objective data.

Introduction

In addition to the relationship between pressure intensity and time, it is clear that frictional and shear forces occur as external forces to the living body. Shear forces obstruct blood flow in the tissue, resulting in tissue ischemia1. In Japan, pressure injuries tend to develop frequently in bedridden older adults with bony prominences. They are especially susceptible to friction and shear forces due to dryness and reduced elasticity of the skin2,3. Therefore, regular repositioning is recommended for reducing pressure and shear force on the skin4.

Preventing pressure injuries requires not only systemic reduction of body pressure but also local depressurisation and reduction of shear force. When the head of a patient’s bed is elevated, the sacrum and coccyx are subjected to severe pressure and shear force, with particular changes in pressure and shear force reported in the sacral region5. In clinical practice, these problems are addressed via depressurisation, which includes pressure redistribution devices and providing daily nursing care. Two such forms of nursing care for depressurisation when a patient’s bed is elevated or lowered are senuki (literally ‘back omission’) and ashinuki (literally ‘leg omission’). Senuki involves the caregiver lifting the patient’s upper body and inserting their hand between the bed and the patient’s back to separate the body from the bed when it is elevated, thereby eliminating the friction and shear force between the patient’s skin and their bedclothes. Ashinuki involves the caregiver elevating the patient’s legs to eliminate the shear force that would otherwise occur from the hip to the posterior surface of the thigh and heel when the bed is elevated or lowered6.

When a bed is elevated, factors such as the concentration of pressure in the buttocks and the sliding down of the body create shear force. Therefore, when elevating a patient’s bed, nurses provide various forms of care such as elevating the legs first, positioning the patient in multiple methods, such as inserting a cushion under their knees to prevent slippage, and elevating the patient’s upper body7–9. However, these nursing interventions were reported in studies that examined the sacrum; few studies have examined changes in pressure or shear force on the heel10,11.

In the supine position, the heel is subjected to continuous pressure, making it vulnerable to tissue injury and pressure injuries. Pressure injuries in the heel are reported to account for one-fourth of all pressure injuries in American hospitals and nursing homes12–15. The effects of bed elevation and other factors make the heel susceptible to friction16. To reduce this friction, preventive dressings are applied17.

The present study examined the pressure and shear force on the heel using a three-axis tactile sensor. Additionally, the aim was to confirm changes in the pressure and shear force on the heel after elevating the heads of patients’ beds, followed by elevating the patients’ lower limbs.

Research Methods

Study design

A quasi-experimental study.

Selection of the participants and period of study

Healthy volunteers aged >30 years were recruited from the researchers’ universities and hospitals. The participants’ number of clinical experiences did not matter in this study design. Posters for research cooperation were displayed on a bulletin board at the facilities to call for participation. The primary author made verbal and e-mail announcements for the same, and used documents to explain the research specifications to individuals who wished to participate. Individuals signed a consent form to confirm participation.

Inclusion criteria required that participants had no wounds on their heels. Temporary redness was considered reactive hyperaemia and such participants were included.

Sample size

When G*Power18 was used to analyse the sample size with an effect size of 0.8, α of 0.05, and a statistical power of 0.8, the sample size was calculated to be n=15. Due to the possibility of an insufficient measurement effect in some participants, we set the sample size as 20. The target number of 20 participants was set to 15 to account for dropouts during data collection. However, no participant met the exclusion criteria and all were included.

Data collection

Data were collected between October 2018 and March 2019.

Measurement environment

Commonly used bedding was selected for the measurements. However, for the convenience of reproducibility, no pillows were used. Other equipment included:

- Electric bed: Paramount bed KA-5000 (4-split type) (Paramount Bed Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

- Base mattress: Everfit KE-521Q (Paramount Bed Corporation, Tokyo, Japan); 10cm thick static mattress.

- Bed sheet: plain woven cotton sheet. The sheets were tucked in when the beds were made.

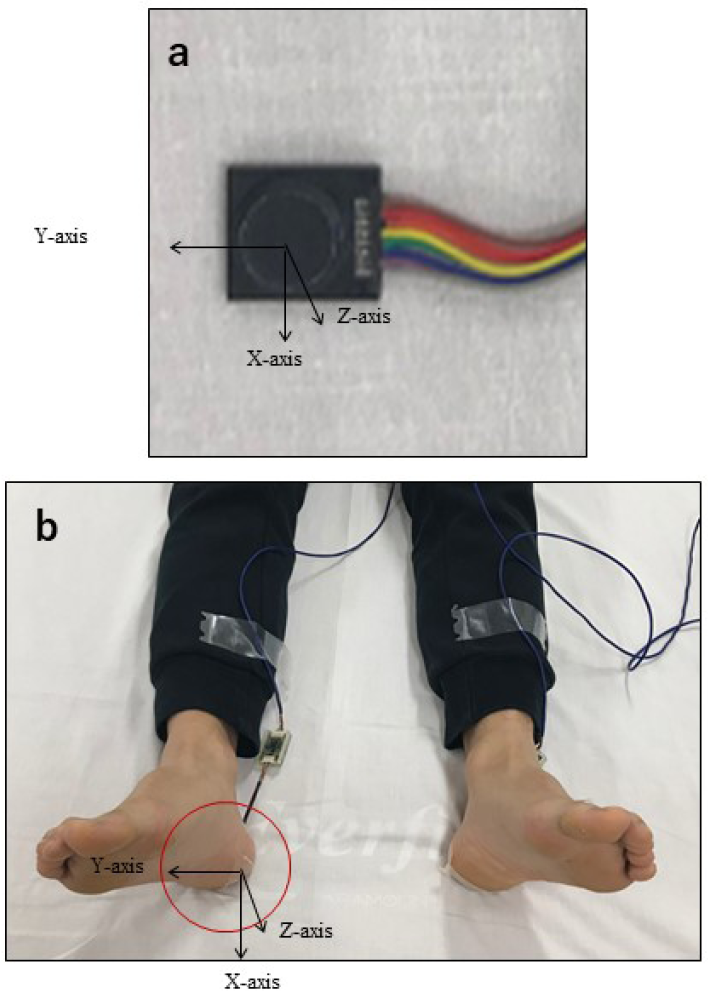

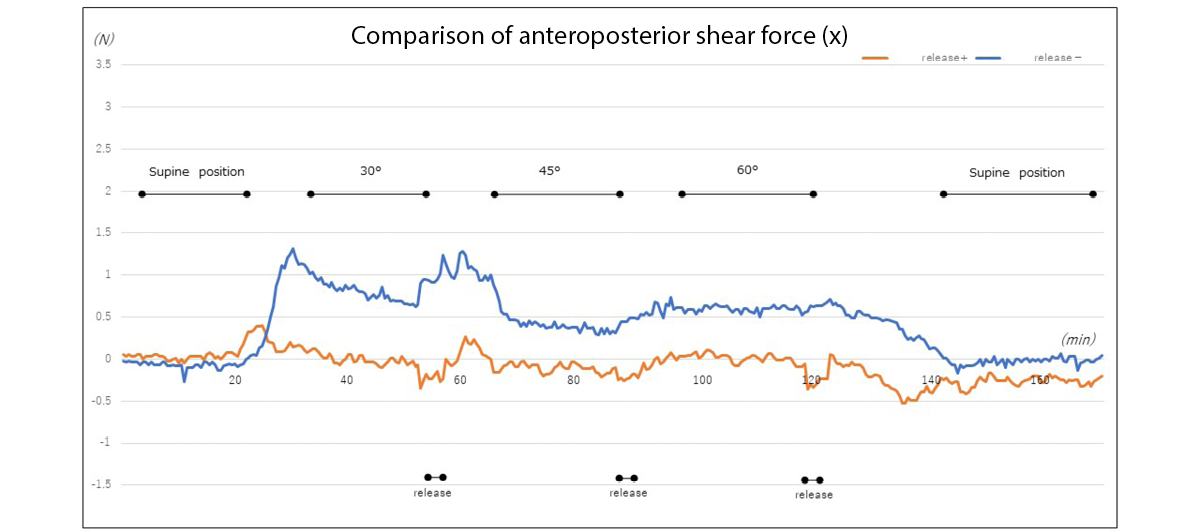

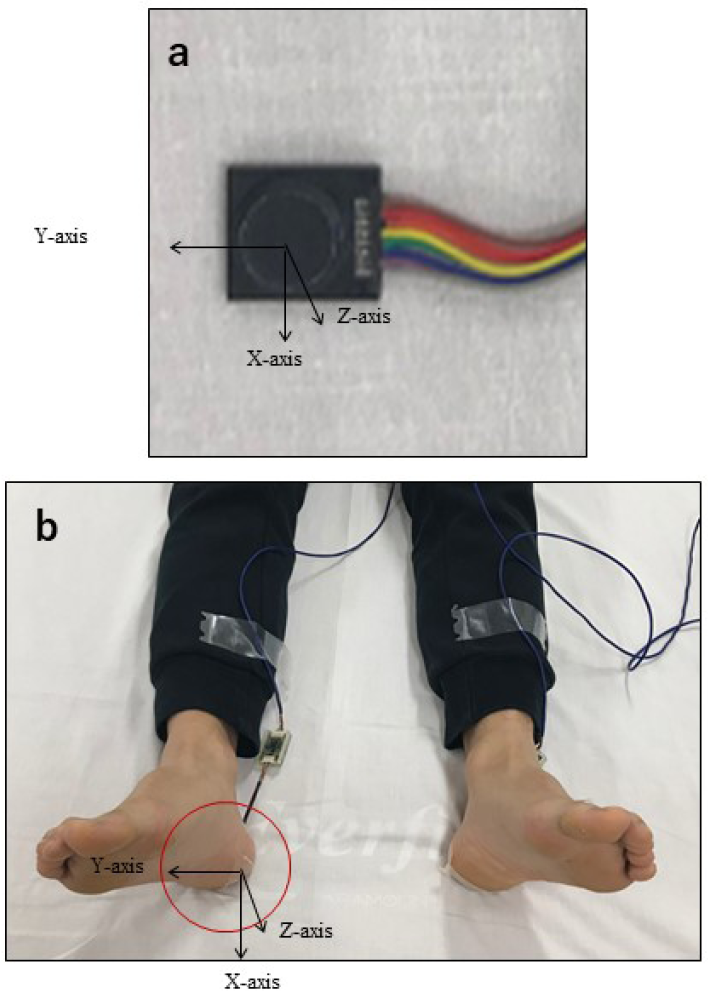

- Measuring device: Three-axis tactile sensor (ShokacChip™T08, Touchence Inc., Tokyo, Japan) 9mm × 9mm × 5mm. The x-, y- and z-axes of the three-axis sensor were set according to pressure, anteroposterior shear force, and lateral shear force, respectively (Figures 1a & b).

Figure 1. A tri-axial tactile sensor was attached to the skin contact area between the heel and the bed and was covered with a dressing. Three directions were measured – anteroposterior shear force (x-axis), lateral shear force (y-axis), and pressure (z-axis)

Measurement procedure

Two experiments were conducted. Experiment 1 measured the pressure and shear force on the heel. Experiment 2 measured the changes in heel pressure and shear force with and without lower limb elevation.

Experiment 1: Changes in heel pressure and shear force upon elevating the head of the bed

The participants slightly opened their lower limbs in a relaxed state and lay in a supine position with their anterior superior iliac spine aligned to the bending point of the bed. The three-axis sensor was applied to the central point of where the left or right heel touched the bed; the film dressing was applied from above (Figures 1a & b). The left or right heel was selected randomly, and the following series of data were collected:

1. After confirming that the participant’s body was still, data for the heel were collected over a 20-second period with the bed in a supine position.

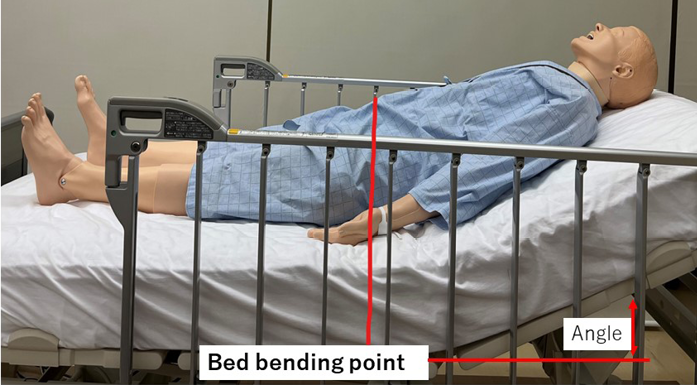

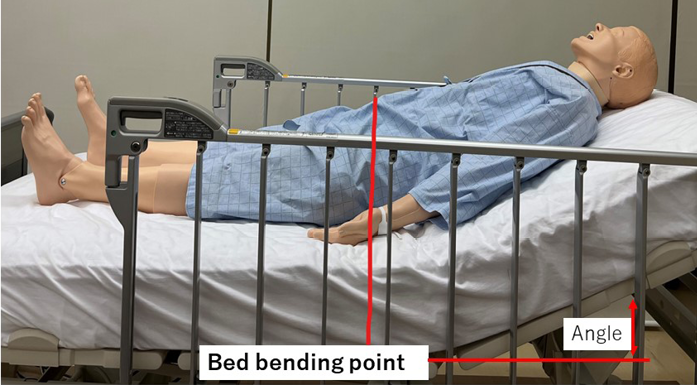

2. After 20 seconds, the participant’s upper body was elevated from the bending point of the bed to a 30˚ angle measured with a goniometer (Figure 2).

3. After the participant’s upper body was elevated, data for the heel were collected while the patient lay still for 20 seconds.

4. The participant’s upper body was then elevated to 45˚ and data were collected in the same manner.

5. After the data collection for the 60˚ elevation, the bed was lowered to a supine position and data were measured for 20 seconds, concluding the experiment.

Experiment 2: Changes in heel pressure and shear force with and without lower limb elevation

As in Experiment 1, the left or right lower limb was selected randomly, and the data collection steps 1−3 in Experiment 1 were repeated. In Experiment 2, the following interventions were carried out from that state.

4. After 20 seconds, either the participant’s left or right knee and ankle were held, lifted up from the hip, and kept still in that position for 5 seconds (Figure 3).

5. After the lower limb was lowered, it was immediately elevated to a 45˚ angle and data were collected for the heel while the participant remained still for 20 seconds.

6. Similar to Step 5 in Experiment 1, after the lower limb was lowered and the head of the bed was elevated to 60˚, the same measurement was performed.

7. Finally, the head of the bed was lowered to a supine position, data were collected for 20 seconds, and the experiment was concluded.

The researcher, a certified expert nurse in wound, ostomy, and continence, conducted Experiments 1 and 2 in this study.

Figure 2. Lying in bed (at the time of elevating the head of the bed)

Figure 3. Lifting the lower limbs

Data analysis

Data were analysed by estimating the average of the observation points at 18 seconds without considering the seconds before and after; the influence of the anteroposterior movement data of the 20 seconds measured for each angle of elevation was also taken into account. Calculations were made by averaging the observation points without the seconds before and after. At the start of the measurement, the initial data value was calibrated to zero and measured twice. The data obtained from the sensors were analysed along the x-axis (anteroposterior shear force), y-axis (lateral shear force), and z-axis (pressure). The pressure and shear force, with and without offloading pressure from the heel at each angle, were analysed using dedicated data software and two-way ANOVA was performed. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 for Windows (IBM Corp. Armonk, N.Y., USA), and the significance level was set at 5%.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Jikei University School of Medicine, Tokyo (9212). The participants were informed of the study orally and in writing, including instructions for the study. The participants’ health status was always observed during the data measurement. They were informed that the procedure would be stopped if they experienced distress. After data collection, we looked for any adverse conditions, such as skin indentation caused by the sensor being applied to the subject’s heel or epidermal peeling caused by the application of the dressing material.

Results

Subject attributes

The study was conducted with 26 participants (11 men and 15 women) with a mean age of 45.1 (±11.1) years and mean BMI of 22.2 (±3.2). No participant met the exclusion criteria, and no adverse events occurred.

Experiment 1: Changes in heel pressure and shear force upon elevating the head of the bed

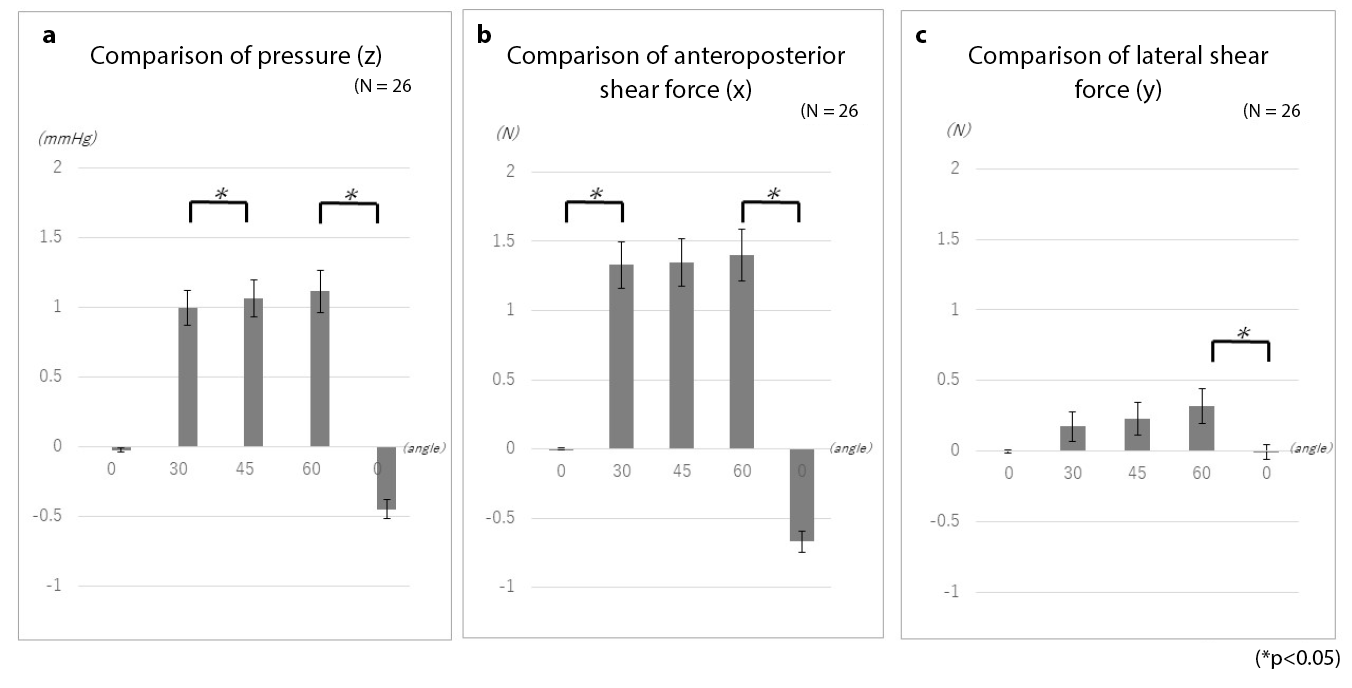

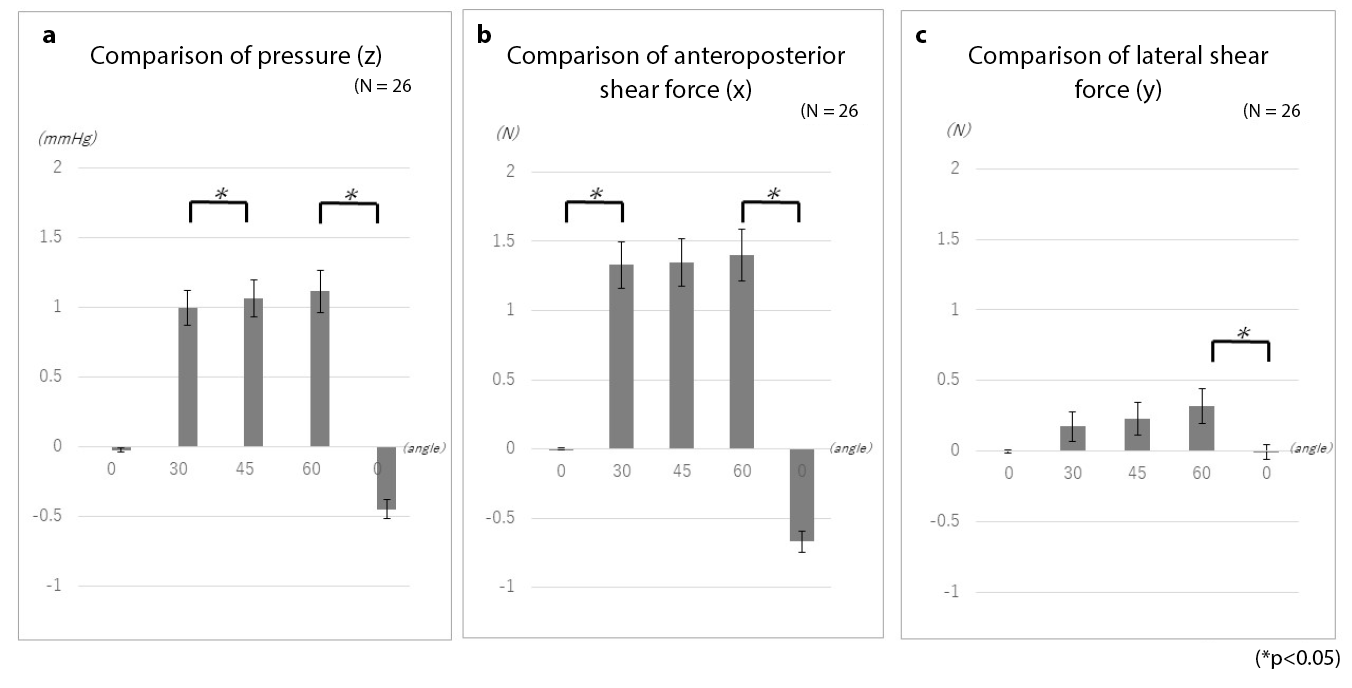

The change in pressure at the heel tended to increase and maintain its value as the head of the bed was raised (Figure 4a). In particular, the pressure increased significantly when the head of the bed was raised from the supine position to 30˚. Subsequently, the pressure values were maintained for the elevation angles of 45˚ and 60˚; no significant increase was observed. However, a significant difference was observed when the angle was changed from 60˚ to the supine position. The pressure initially dropped, but did not return to the starting pressure, which further decreased.

The shear force in the front–back direction tended to increase with the elevation angle. Similar to the pressure values found, the value increased significantly at the 30˚ angle of elevation, and a significant difference was observed. After 45˚, the anteroposterior shear force was maintained but did not increase significantly when the angle was raised from the supine position to 60˚. However, when the angle was changed from 60˚ to the supine position, shear force in the opposite direction was added and a significant difference was observed (Figure 4b).

Although the lateral shear force increased as the head of the bed was elevated, it did not change as greatly as the anteroposterior shear force. A significant difference was observed when the bed was lowered from a 60˚ angle to a supine position. However, the large changes that occurred in the anteroposterior shear force did not occur in the case of lateral shear force (Figure 4c).

Figure 4. Changes in heel pressure and shear force while elevating the head of the bed

Experiment 2: Changes in heel pressure and shear force with and without lower limb elevation

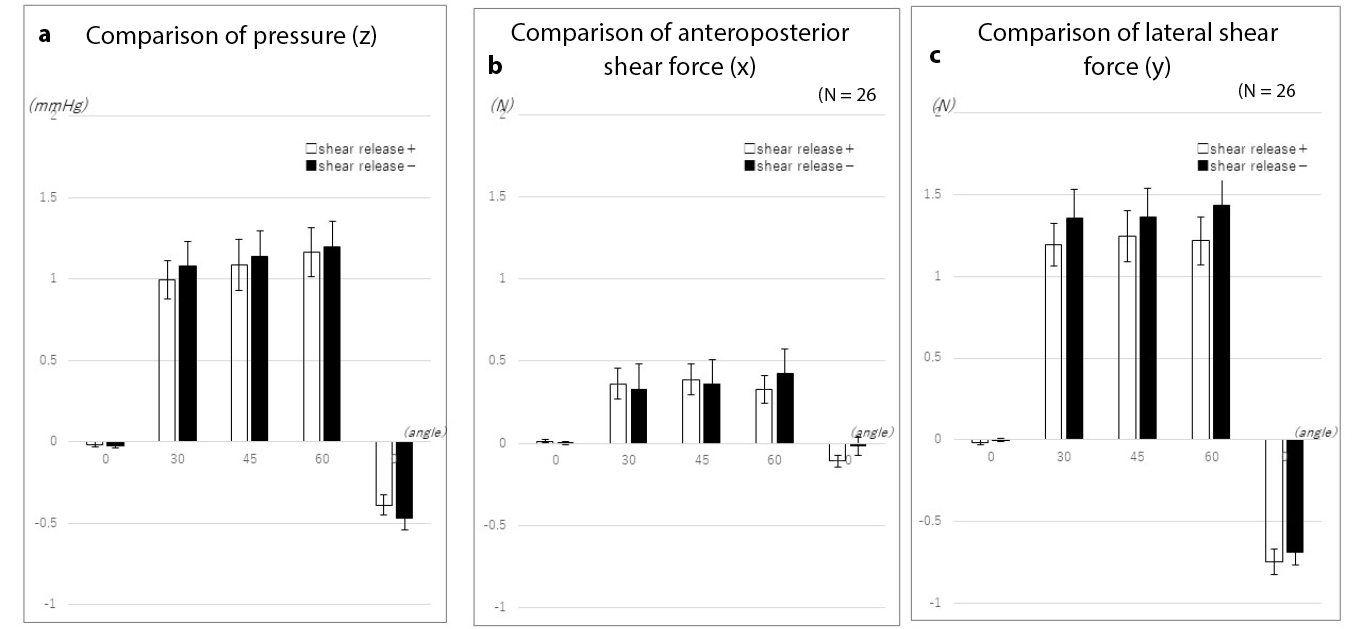

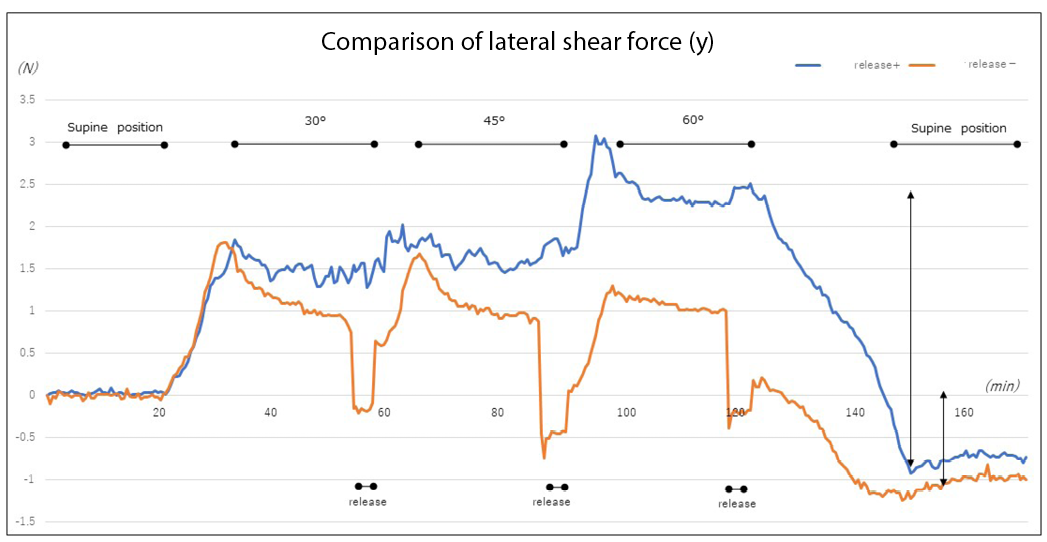

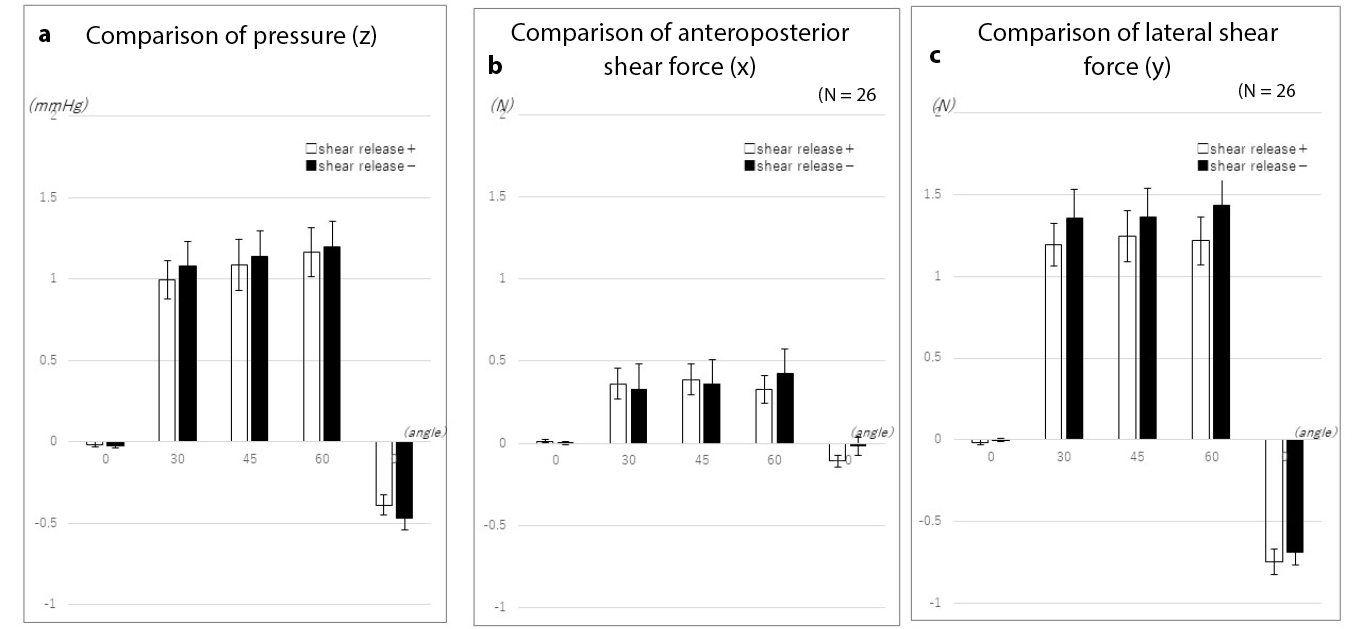

Examinations of the changes in pressure with and without elevation of the lower limbs showed no significant differences in pressure, anteroposterior shear force, or lateral shear force (Figure 5). However, as with the measurements taken with simple elevation of the head of the bed, even when pressure and shear force were offloaded, elevating the head of the bed led to the reapplication of external force. Moreover, while the anteroposterior shear force was large when only the head of the bed was elevated, the lateral shear force increased upon lower limb elevation. An example of elevating the head of the bed is presented here to explain these changes.

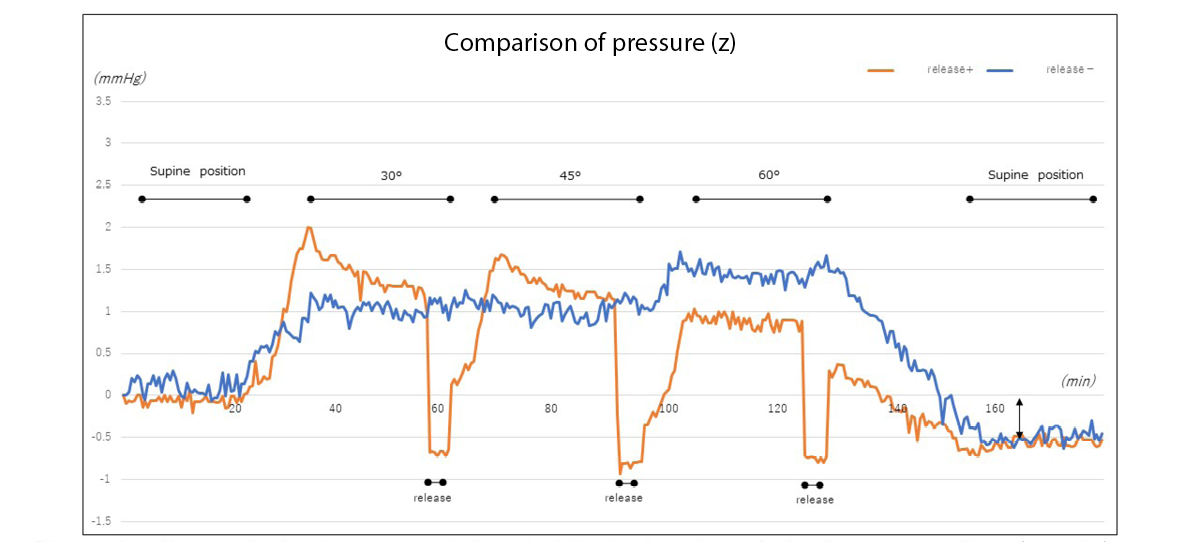

Figure 5. Changes in heel pressure and shear force with and without lower limb elevation

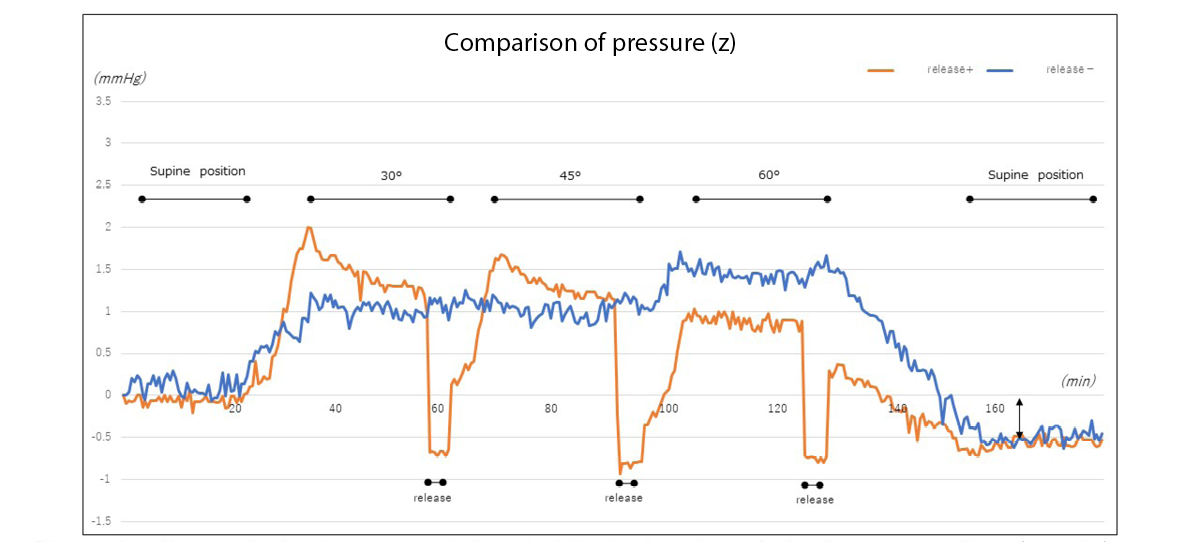

When the head of the bed was elevated to 30˚, elevation of the lower limbs temporarily offloaded the pressure on the heel. While further bed elevation once again increased pressure on the heel, lower limb elevation tended to inhibit subsequent increases in pressure (Figure 6a).

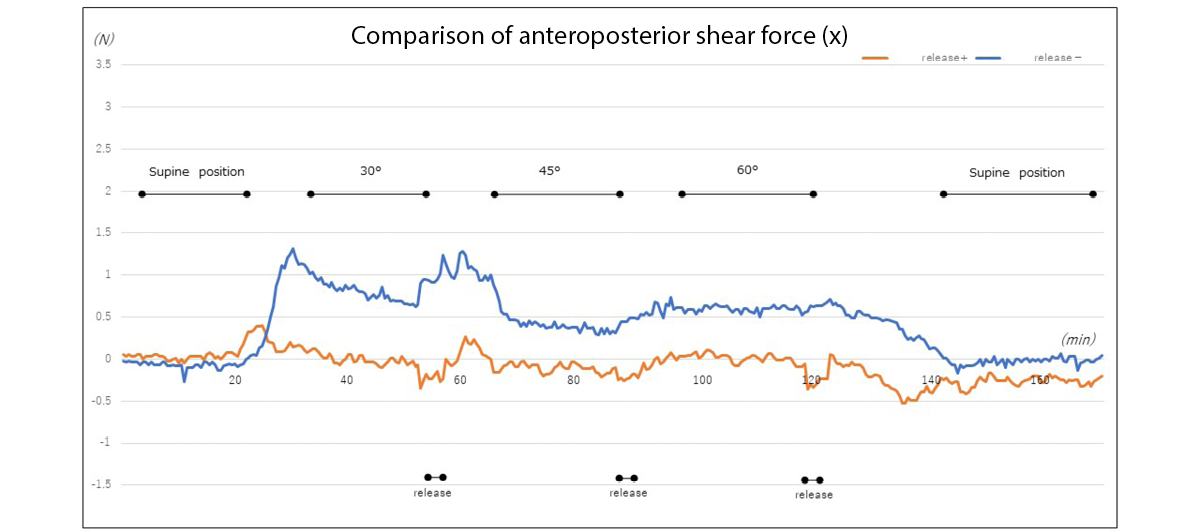

When the lower limbs were not elevated, the anteroposterior shear force increased slightly when the bed head was elevated to 30˚. On the other hand, when the lower limbs were elevated, no significant change occurred (Figure 6b).

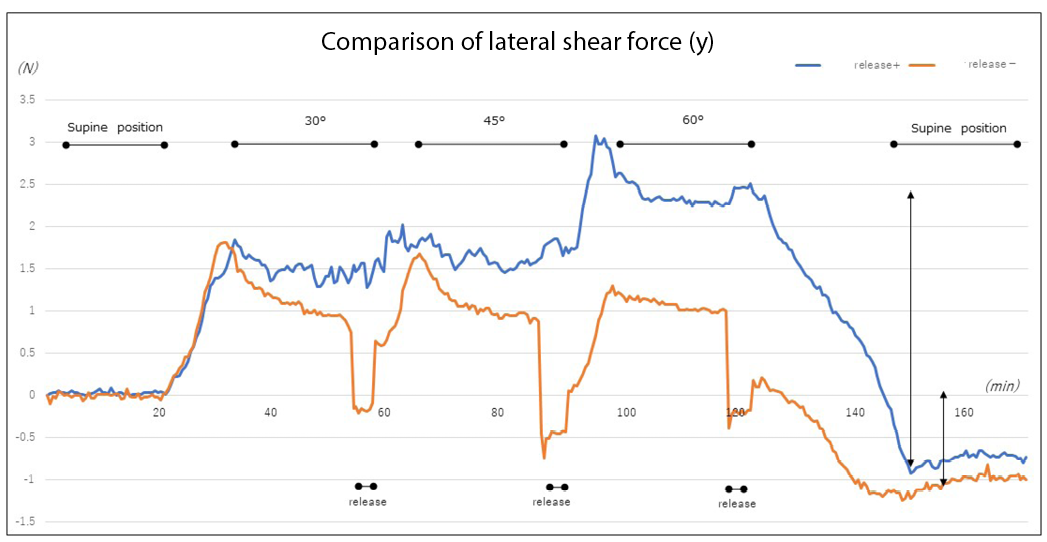

Similarly, the lateral shear force increased without elevation of the lower limb when the head of the bed was elevated to 30˚. On further elevation of the head of the bed, the lateral shear force increased in the absence of lower limb elevation. The greatest change occurred when the bed returned to the supine position. When the lower limb was elevated, the lateral shear force was temporarily offloaded. However, elevating the head of the bed again created lateral shear force. Although the difference in lateral shear force when the bed returned to the supine position was smaller than the difference observed without elevation of the lower limb, the results demonstrated the occurrence of lateral shear force associated with temporary offloading of force (Figure 6c).

Figure 6a. Changes in heel pressure with and without elevation of the lower extremity (example)

Figure 6b. Changes in anteroposterior shear force at the heel with and without elevation of the lower limb (example)

Figure 6c. Changes in lateral shear force at the heel with and without elevation of the lower limb (example)

Discussion

The experimental results revealed that the pressure and shear force at the heel increased with elevating the head of the bed. In particular, the rate of change in the values was large at the 30˚ angle of elevation. As previously reported, this is attributed to the effect of the centre of gravity shifting and upper body sliding down due to head elevation17–19. From the viewpoint of preventing pressure injury in the buttocks, it is desirable that the angle of elevating the head of the bed be 30˚ or less20. Although the 30˚ rule”(30˚ lateral supine, elevating the head of the bed by 30˚) has been widely used in positioning to prevent pressure injury, it has also been reported to delay healing in patients with pressure injury in the buttocks21. Therefore, the 4th edition of the Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers states that positioning other than the 30˚ side-lying and 30˚ supine positions may be performed22.

The heel is a common site of pressure injuries. Even if a visual assessment identifies no problems, tissue injury occurs, leading to deep tissue injury (DTI) due to changes inside the tissue. When pressure injuries are detected by a physician, the skin is often discoloured and injured, with DTI having already occurred16. As the heel is known to have a lower concentration of melanocytes, tissue response to stress and tissue injury are difficult to detect based on changes in skin colour23. In addition, while the epidermis may be thick in the lateral aspect of the sole of the heel, the skin of the posterior heel is relatively thin. In older adults and patients with fragile skin, capillary density is low and mass is reduced throughout the soft tissue in the posterior heel, adversely affecting the linkage between the epidermis and skin junctions24, conceivably increasing the risk of pressure injuries. Similar results were observed among the present study’s participants, despite having a mean BMI of 22.2 (±3.2) and standard body type. The participants’ BMI led to changes in mass throughout the soft tissue in the posterior heel. Conceivably, BMI and heel bone geometry also affected the linkage between the epidermis and skin junctions, suggesting an effect on pressure and shear force as well.

The present experiments demonstrated that powerful pressure and shear force occur when the head of a hospital bed is elevated to the recommended angle of 30˚. In the initial measurement, the head of the bed was elevated with the participant’s superior anterior iliac spine aligned with the bending point of the bed to prevent the body from sliding down. However, because the knees are not elevated and the heels are not supported, continuous strain on soft tissue leads to tissue injury25 and multiple thrombosis26, often causing DTI. In fact, this strain was shown to act as the anteroposterior and lateral shear forces due to elevation of the head of the hospital bed, elevation of the lower limbs, and other acts of nursing care. Although the lower limbs are elevated as a form of preventive care, we learned that this elevation does not entirely eliminate external force. This finding suggests the need for further preventive measures based on objective data.

The application of polyurethane foam/soft silicon foam to the heel has been reported to reduce friction and shear force on the heel, resulting in prevention of pressure injuries27,28. The skin of elder adults is dry, resulting in friction even when they sleep on bedsheets. The application of moisturiser, particularly the use of ceramide-containing formulations, to moisturise dry skin daily is reported to be an effective nursing intervention29; therefore, this intervention is also important to incorporate. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel guidelines also recommend the use of sheets made of silk or other similar material instead of cotton or cotton blends to reduce friction and shear force30.

Considering the advancements in body pressure redistribution devices, repositioning at conventional 2-hour intervals is reported to not differ from repositioning at 3- or 4-hour intervals31. When a patient’s body is repositioned (or their posture is maintained), it is supported with cushions and pillows. Although this study used four-section hospital beds, data in the present experiments were collected for the heel with only participants’ upper bodies being elevated and without elevation of the lower limb. However, with a bed that permits elevation of the lower limbs, conventional positioning requires elevation of the lower extremity side of the bed to prevent posture collapse and reduce pressure on the buttocks associated with the sliding down of the upper body; elimination of external force through means such as lower limb elevation may thus be required. Patients’ bodies are repositioned to regularly change their recumbent position and shift the external force that would otherwise continue to act on the same site.

However, while voluntary movement is also important, it is sometimes difficult for patients who have trouble moving on their own. In Japan, studies are being conducted on ‘small changes’, a body pressure dispersal method involving the use of a small pillow. ‘Small changes’ refers to a method in which a small pillow is moved at regular intervals to the shoulder, hip or lower extremity on one side of the body to change the site on which pressure acts and thus redistribute pressure. This method has been reported to reduce the incidence of pressure injuries32,33. Furthermore, an air mattress equipped with such a small change system has been developed, with a study having reported on its efficacy in preventing pressure injuries34.

Along with the measures described above to prevent pressure injuries in the heel, ultrasonography is also being used to detect pressure injuries at an early stage without relying on visual assessment35. Acquiring more basic data, such as that obtained in the present experiment, may be necessary.

More comments are needed on what is currently known about nursing interventions such as repositioning, frequency of repositioning to reduce pressure, shear force and friction, and the use of a knee-break or knee elevation capability of beds or simple devices such as pillows, etc to alleviate heel pressure shear and friction.

Limitations of the study and future challenges

In this study, the target age group was relatively young. Their skin structure in the heel region differs from that of older adults, who are more prone to pressure injury, and there are limitations when comparing with patients who are more prone to pressure injury. The mattress used was a urethane mattress, which is used to prevent pressure injury; hence, the effects of using other materials, such as an air mattress, need to be examined in the future.

Based on these results, we intend to consider more clinically-relevant positioning and pressure redistribution methods in the future. Additionally, we would like to check the changes occurring in not only the heel region but also the sacral region and other bone protrusion sites and collect data to provide evidence for nursing practice.

Conclusions

When elevation was performed, the pressure and shear force on the heel increased significantly at 30˚. The elevation of the lower limbs led to an offloading of continuous pressure and shear force on the heel, although the differences were not significant. However, we noted the pressure and shear force that occurred while elevating the head of the bed and determined that elevation of the lower limbs, a typical act of nursing care, does not prevent the application of shear force. Further examination with more objective data will be conducted to examine preventive nursing interventions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the study participants for their cooperation. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Jikei University School of Medicine, Tokyo (9212).

Funding

This study received a research grant from the School of Nursing, the Jikei University School of Medicine. However, they were not involved in any aspect of the study content, including study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; they only provided funding.

Encuesta de investigación de la presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento en el talón mediante un sensor táctil de tres ejes

Yoko Murooka and Hidemi Nemoto Ishii

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.1.20-27

Resumen

Objetivos Investigamos los cambios en la presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento en el talón causados por la elevación de la cabecera de la cama y después de descargar la presión del talón.

Métodos Se recogieron datos sobre la presión del talón y la fuerza de cizallamiento de 26 individuos sanos de >30 años utilizando un sensor táctil de tres ejes en cada ángulo formado al elevar la parte superior del cuerpo de los participantes desde una posición supina. Se recogieron y compararon los datos tras la liberación de la presión del pie izquierdo o derecho.

Resultados La edad media de los participantes era de 45,1 (±11,1) años. La presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento anteroposterior en el talón aumentaban con la elevación. Estos aumentos eran especialmente destacados cuando el ángulo de elevación era de 30˚. En las inclinaciones posteriores de 45˚ y 60˚, la presión corporal y la fuerza de cizallamiento aumentaron ligeramente, pero no de forma significativa. La presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento se liberaban elevando la extremidad inferior cada vez que se elevaba la cabecera de la cama. Sin embargo, mayores elevaciones provocaron un aumento de la presión y de la fuerza de cizallamiento , en particular de la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral. La presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento no cambiaron significativamente cuando se elevaron las extremidades inferiores.

Conclusión La elevación recomendada de la cabecera de la cama a no más de 30˚ produjo cambios importantes. Elevar la pierna aliviaba el talón de la presión continua y la fuerza de cizallamiento, al tiempo que aumentaba la presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral. Aunque la elevación de las piernas es un aspecto de los cuidados diarios de enfermería, es importante investigar dichas intervenciones de enfermería utilizando datos objetivos.

Introducción

Además de la relación entre la intensidad de la presión y el tiempo, está claro que las fuerzas de fricción y cizallamiento se producen como fuerzas externas al cuerpo vivo. Las fuerzas de cizallamiento obstruyen el flujo sanguíneo en el tejido, lo que provoca isquemia tisular1. En Japón, las lesiones por presión tienden a desarrollarse con frecuencia en adultos mayores encamados con prominencias óseas. Son especialmente susceptibles a las fuerzas de fricción y cizallamiento debido a la sequedad y a la menor elasticidad de la piel2,3. Por lo tanto, se recomienda cambiar regularmente de posición para reducir la presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento sobre lapiel4.

La prevención de las lesiones por presión requiere no sólo la reducción sistémica de la presión corporal, sino también la despresurización local y la reducción de la fuerza de cizallamiento. Cuando se eleva la cabecera de la cama de un paciente, el sacro y el cóccix se ven sometidos a una fuerte presión y fuerza de cizallamiento, con cambios particulares de presión y fuerza de cizallamiento registrados en la región sacra5. En la práctica clínica, estos problemas se abordan mediante la despresurización, que incluye dispositivos de redistribución de la presión y la prestación de cuidados diarios de enfermería. Dos de estas formas de cuidados de enfermería para la despresurización cuando se eleva o se baja la cama de un paciente son senuki (literalmente "omisión de la espalda") y ashinuki (literalmente "omisión de las piernas"). Senuki consiste en que el cuidador levante la parte superior del cuerpo del paciente e introduzca la mano entre la cama y la espalda del paciente para separar el cuerpo de la cama cuando esté elevada, eliminando así la fricción y la fuerza de cizallamiento entre la piel del paciente y su ropa de cama. El ashinuki consiste en que el cuidador eleve las piernas del paciente para eliminar la fuerza de cizallamiento que, de otro modo, se produciría desde la cadera hasta la superficie posterior del muslo y el talón al elevar o bajar la cama6.

Cuando se eleva una cama, factores como la concentración de presión en las nalgas y el deslizamiento hacia abajo del cuerpo crean una fuerza de cizallamiento. Por lo tanto, al elevar la cama de un paciente, las enfermeras proporcionan diversas formas de cuidado, como elevar primero las piernas, colocar al paciente en múltiples métodos, como insertar un cojín bajo sus rodillas para evitar deslizamientos, y elevar la parte superior del cuerpo del paciente7-9. Sin embargo, estas intervenciones de enfermería se comunicaron en estudios que examinaron el sacro; pocos estudios han examinado los cambios en la presión o la fuerza de cizallamiento en el talón10,11.

En posición supina, el talón está sometido a una presión continua, lo que lo hace vulnerable a lesiones tisulares y lesiones por presión. Según los informes, las lesiones por presión en el talón representan una cuarta parte de todas las lesiones por presión en los hospitales y residencias de ancianos estadounidenses12-15. Los efectos de la elevación de la cama y otros factores hacen que el talón sea susceptible a la fricción16. Para reducir esta fricción, se aplican apósitos preventivos17.

El presente estudio examinó la presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento en el talón utilizando un sensor táctil de tres ejes. Además, el objetivo era confirmar los cambios en la presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento en el talón tras elevar las cabeceras de las camas de los pacientes, seguido de la elevación de las extremidades inferiores de los pacientes.

Métodos de investigación

Diseño del estudio

Un estudio cuasiexperimental.

Selección de los participantes y periodo de estudio

Se reclutaron voluntarios sanos de más de 30 años en las universidades y hospitales de los investigadores. El número de experiencias clínicas de los participantes no importaba en el diseño de este estudio. En un tablón de anuncios de las instalaciones se expusieron carteles para la cooperación en la investigación con el fin de llamar a la participación. El autor principal hizo anuncios verbales y por correo electrónico de la misma, y utilizó documentos para explicar las especificaciones de la investigación a las personas que deseaban participar. Las personas firmaron un formulario de consentimiento para confirmar su participación.

Los criterios de inclusión exigían que los participantes no tuvieran heridas en los talones. El enrojecimiento temporal se consideró hiperemia reactiva y se incluyó a dichos participantes.

Tamaño de la muestra

Cuando se utilizó G*Power18 para analizar el tamaño de la muestra con un tamaño del efecto de 0,8, α de 0,05 y una potencia estadística de 0,8, se calculó que el tamaño de la muestra era n=15. Debido a la posibilidad de un efecto de medición insuficiente en algunos participantes, fijamos el tamaño de la muestra en 20. El número objetivo de 20 participantes se fijó en 15 para tener en cuenta los abandonos durante la recogida de datos. Sin embargo, ningún participante cumplió los criterios de exclusión y todos fueron incluidos.

Recogida de datos

Los datos se recopilaron entre octubre de 2018 y Marzo de 2019.

Entorno de medición

Para las mediciones se seleccionó ropa de cama de uso común. Sin embargo, para facilitar la reproducibilidad, no se utilizaron almohadas. Otros equipos incluidos:

- Cama eléctrica: Cama Paramount KA-5000 (tipo 4-split) (Paramount Bed Corporation, Tokio, Japón).

- Colchón base: Everfit KE-521Q (Paramount Bed Corporation, Tokio, Japón); colchón estático de 10 cm de grosor.

- Sábana bajera: sábana de algodón de tejido liso. Las sábanas estaban recogidas cuando se hacían las camas.

- Dispositivo de medición: Sensor táctil de tres ejes (ShokacChip™T08, Touchence Inc., Tokio, Japón) 9 mm × 9 mm × 5 mm. Los ejes x, y y z del sensor de tres ejes se ajustaron en función de la presión, la fuerza de cizallamiento anteroposterior y la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral, respectivamente (figuras 1a y b).

Figura 1. Se colocó un sensor táctil triaxial en la zona de contacto de la piel entre el talón y la cama y se cubrió con un apósito Se midieron tres direcciones: fuerza de cizallamiento anteroposterior (eje x), fuerza de cizallamiento lateral (eje y) y presión (eje z)

Procedimiento de medición

Se realizaron dos experimentos. El experimento 1 midió la presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento en el talón. El experimento 2 midió los cambios en la presión del talón y la fuerza de cizallamiento con y sin elevación de las extremidades inferiores.

Experimento 1: Cambios en la presión del talón y la fuerza de cizallamiento al elevar la cabecera de la cama

Los participantes abrieron ligeramente las extremidades inferiores en estado de relajación y se tumbaron en decúbito supino con la espina ilíaca anterosuperior alineada con el punto de flexión de la cama. El sensor de tres ejes se aplicó en el punto central donde el talón izquierdo o derecho tocaba la cama; el apósito de película se aplicó desde arriba (Figuras 1a y b). Se seleccionó al azar el talón izquierdo o derecho y se recogieron las siguientes series de datos:

1. Tras confirmar que el cuerpo del participante estaba quieto, se recogieron los datos del talón durante un periodo de 20 segundos con la cama en posición supina.

2. Tras 20 segundos, se elevó la parte superior del cuerpo del participante desde el punto de flexión de la cama hasta un ángulo de 30˚ medido con un goniómetro (Figura 2).

3. Tras elevar la parte superior del cuerpo del participante, se recogieron los datos del talón mientras el paciente permanecía inmóvil durante 20 segundos.

4. A continuación, se elevó la parte superior del cuerpo del participante a 45˚ y se recogieron los datos de la misma manera.

5. Tras la recogida de datos para la elevación de 60˚, se bajó la cama a posición supina y se midieron los datos durante 20 segundos, con lo que concluyó el experimento.

Experimento 2: Cambios en la presión del talón y la fuerza de cizallamiento con y sin elevación de la extremidad inferior

Como en el Experimento 1, se seleccionó aleatoriamente la extremidad inferior izquierda o derecha, y se repitieron los pasos 1-3 de recogida de datos del Experimento 1. En el Experimento 2, se realizaron las siguientes intervenciones a partir de ese estado.

4. Después de 20 segundos, se sujetaban la rodilla y el tobillo izquierdo o derecho del participante, se levantaban desde la cadera y se mantenían inmóviles en esa posición durante 5 segundos (Figura 3).

5. Tras bajar la extremidad inferior, se elevó inmediatamente hasta un ángulo de 45˚ y se recogieron los datos del talón mientras el participante permanecía quieto durante 20 segundos.

6. De forma similar al Paso 5 del Experimento 1, después de bajar la extremidad inferior y elevar la cabecera de la cama a 60˚, se realizó la misma medición.

7. Por último, se bajó la cabecera de la cama hasta la posición supina, se recogieron datos durante 20 segundos y se dio por concluido el experimento.

La investigadora, enfermera experta certificada en heridas, ostomía y continencia, llevó a cabo los experimentos 1 y 2 de este estudio.

Figura 2. Tumbado en la cama (en el momento de elevar la cabecera de la cama)

Figura 3. Elevación de los miembros inferiores

Analisis de datos

Los datos se analizaron estimando la media de los puntos de observación a los 18 segundos sin tener en cuenta los segundos anteriores y posteriores; también se tuvo en cuenta la influencia de los datos del movimiento anteroposterior de los 20 segundos medidos para cada ángulo de elevación Los cálculos se realizaron promediando los puntos de observación sin los segundos anteriores y posteriores. Al comienzo de la medición, el valor inicial de los datos se calibró a cero y se midió dos veces. Los datos obtenidos de los sensores se analizaron a lo largo de los ejes x (fuerza de cizallamiento anteroposterior), y (fuerza de cizallamiento lateral) y z (presión). La presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento, con y sin descarga de presión del talón en cada ángulo, se analizaron mediante un software de datos específico y se realizó un ANOVA de dos vías. Todos los análisis estadísticos se realizaron con el programa SPSS 23.0 para Windows (IBM Corp. Armonk, N.Y., EE. UU.), y el nivel de significación se fijó en el 5%.

Consideraciones éticas

El estudio fue aprobado por el Comité de Revisión Ética de la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Jikei de Tokio (9212). Los participantes fueron informados del estudio oralmente y por escrito, incluidas las instrucciones para el estudio. Siempre se observó el estado de salud de los participantes durante la medición de los datos. Se les informó de que el procedimiento se interrumpiría si experimentaban angustia. Tras la recogida de datos, se buscó cualquier condición adversa, como la indentación de la piel causada por la aplicación del sensor en el talón del sujeto o la descamación epidérmica causada por la aplicación del material de vendaje.

Resultados

Atributos temáticos

El estudio se realizó con 26 participantes (11 hombres y 15 mujeres) con una edad media de 45,1 (±11,1) años y un IMC medio de 22,2 (±3,2). Ningún participante cumplió los criterios de exclusión y no se produjeron acontecimientos adversos.

Experimento 1: Cambios en la presión del talón y la fuerza de cizallamiento al elevar la cabecera de la cama

El cambio de presión en el talón tendía a aumentar y mantener su valor a medida que se elevaba la cabecera de la cama (figura 4a). En particular, la presión aumentó significativamente cuando la cabecera de la cama se elevó desde la posición supina hasta 30˚. Posteriormente, los valores de presión se mantuvieron para los ángulos de elevación de 45˚ y 60˚; no se observó ningún aumento significativo. Sin embargo, se observó una diferencia significativa cuando se cambió el ángulo de 60˚ a la posición supina. La presión descendió inicialmente, pero no volvió a la presión inicial, que siguió disminuyendo.

La fuerza de cizallamiento en la dirección delante-detrás tendía a aumentar con el ángulo de elevación. De forma similar a los valores de presión encontrados, el valor aumentó significativamente en el ángulo de elevación de 30˚, observándose una diferencia significativa. Después de 45˚, la fuerza de cizallamiento anteroposterior se mantuvo y no aumentó significativamente cuando se elevó el ángulo desde la posición supina hasta 60˚. Sin embargo, cuando se cambió el ángulo de 60˚ a la posición supina, se añadió fuerza de cizallamiento en la dirección opuesta y se observó una diferencia significativa (Figura 4b).

Aunque la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral aumentó al elevar la cabecera de la cama, no varió tanto como la fuerza de cizallamiento anteroposterior. Se observó una diferencia significativa cuando se bajó la cama desde un ángulo de 60˚ hasta la posición supina. Sin embargo, los grandes cambios que se produjeron en la fuerza de cizallamiento anteroposterior no se produjeron en el caso de la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral (Figura 4c).

Figura 4. Cambios en la presión del talón y la fuerza de cizallamiento al elevar la cabecera de la cama

Experimento 2: Cambios en la presión del talón y la fuerza de cizallamiento con y sin elevación de la extremidad inferior

Los exámenes de los cambios en la presión con y sin elevación de las extremidades inferiores no mostraron diferencias significativas en la presión, la fuerza de cizallamiento anteroposterior o la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral (Figura 5). Sin embargo, al igual que en las mediciones realizadas con la simple elevación de la cabecera de la cama, incluso cuando se descargaban la presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento, la elevación de la cabecera de la cama provocaba la reaplicación de la fuerza externa. Además, mientras que la fuerza de cizallamiento anteroposterior era grande cuando sólo se elevaba la cabecera de la cama, la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral aumentaba al elevar las extremidades inferiores. A continuación se presenta un ejemplo de elevación de la cabecera de la cama para explicar estos cambios.

Figura 5. Cambios en la presión del talón y la fuerza de cizallamiento con y sin elevación de la extremidad inferior

Cuando la cabecera de la cama se elevó a 30˚, la elevación de las extremidades inferiores descargó temporalmente la presión sobre el talón. Aunque una mayor elevación de la cama volvió a aumentar la presión sobre el talón, la elevación de las extremidades inferiores tendió a inhibir los aumentos posteriores de la presión (Figura 6a).

Cuando las extremidades inferiores no estaban elevadas, la fuerza de cizallamiento anteroposterior aumentaba ligeramente cuando la cabecera de la cama se elevaba a 30˚. Por otro lado, cuando se elevaron las extremidades inferiores, no se produjo ningún cambio significativo (Figura 6b).

Del mismo modo, la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral aumentó sin elevación de la extremidad inferior cuando la cabecera de la cama se elevó a 30˚. Al elevar más la cabecera de la cama, la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral aumentaba en ausencia de elevación de las extremidades inferiores. El mayor cambio se produjo cuando la cama volvió a la posición supina. Cuando se elevaba la extremidad inferior, se descargaba temporalmente la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral. Sin embargo, la elevación de la cabecera de la cama volvió a crear una fuerza de cizallamiento lateral. Aunque la diferencia en la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral cuando la cama volvió a la posición supina fue menor que la diferencia observada sin elevación de la extremidad inferior, los resultados demostraron la aparición de la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral asociada a la descarga temporal de la fuerza (Figura 6c).

Figura 6a. Cambios en la presión del talón con y sin elevación de la extremidad inferior (ejemplo)

Figura 6b. Cambios en la fuerza de cizallamiento anteroposterior en el talón con y sin elevación de la extremidad inferior (ejemplo

Figura 6c. Cambios en la fuerza de cizallamiento lateral en el talón con y sin elevación de la extremidad inferior (ejemplo)

Discusion

Los resultados experimentales revelaron que la presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento en el talón aumentaban al elevar la cabecera de la cama. En particular, la tasa de cambio de los valores fue grande en el ángulo de elevación de 30˚. Como ya se ha informado anteriormente, esto se atribuye al efecto del desplazamiento del centro de gravedad y el deslizamiento hacia abajo de la parte superior del cuerpo debido a la elevación de la cabeza17-19. Desde el punto de vista de la prevención de lesiones por presión en las nalgas, es deseable que el ángulo de elevación de la cabecera de la cama sea de 30˚ o menos20. Aunque la "regla de los 30˚" (30˚ de decúbito supino lateral, elevando la cabecera de la cama 30˚) se ha utilizado ampliamente en el posicionamiento para prevenir las lesiones por presión, también se ha informado de que retrasa la curación en pacientes con lesiones por presión en las nalgas21. Por lo tanto, la 4ª edición de las Directrices para la prevención y el tratamiento de las úlceras por presión establece que se pueden realizar posicionamientos distintos a las posiciones de 30˚ en decúbito lateral y 30˚ en decúbito supino22.

El talón es un lugar habitual de lesiones por presión. Incluso si una evaluación visual no identifica ningún problema, se produce una lesión tisular que da lugar a una lesión tisular profunda (DTI) debido a cambios en el interior del tejido. Cuando el médico detecta lesiones por presión, la piel suele estar descolorida y lesionada, y ya se ha producido la DTI16. Como se sabe que el talón tiene una menor concentración de melanocitos, la respuesta del tejido al estrés y las lesiones tisulares son difíciles de detectar basándose en los cambios de color de la piel23. Además, mientras que la epidermis puede ser gruesa en la cara lateral de la planta del talón, la piel del talón posterior es relativamente fina. En los adultos mayores y en los pacientes con piel frágil, la densidad capilar es baja y la masa se reduce en todo el tejido blando de la parte posterior del talón, lo que afecta negativamente a la unión entre la epidermis y las uniones cutáneas24, aumentando posiblemente el riesgo de lesiones por presión. Se observaron resultados similares entre los participantes del presente estudio, a pesar de tener un IMC medio de 22,2 (±3,2) y un tipo de cuerpo estándar. El IMC de los participantes provocó cambios en la masa de todo el tejido blando de la parte posterior del talón. Es concebible que el IMC y la geometría del hueso del talón también afectaran a la unión entre la epidermis y las uniones cutáneas, lo que sugiere un efecto también sobre la presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento.

Los presentes experimentos demostraron que se produce una fuerte presión y fuerza de cizallamiento cuando la cabecera de una cama de hospital se eleva hasta el ángulo recomendado de 30˚. En la medición inicial, la cabecera de la cama se elevó con la espina ilíaca anterior superior del participante alineada con el punto de flexión de la cama para evitar que el cuerpo se deslizara hacia abajo. Sin embargo, como las rodillas no están elevadas y los talones no están apoyados, la tensión continua sobre los tejidos blandos provoca lesiones tisulares25 y trombosis múltiples26, que a menudo causan DTI. De hecho, se demostró que esta tensión actúa como las fuerzas de cizallamiento anteroposterior y lateral debidas a la elevación de la cabecera de la cama del hospital, la elevación de las extremidades inferiores y otros actos de los cuidados de enfermería. Aunque los miembros inferiores se elevan como forma de cuidado preventivo, aprendimos que esta elevación no elimina por completo la fuerza externa. Este hallazgo sugiere la necesidad de nuevas medidas preventivas basadas en datos objetivos.

Se ha descrito que la aplicación de espuma de poliuretano/espuma de silicona blanda en el talón reduce la fricción y la fuerza de cizallamiento en el talón, lo que resulta en la prevención de lesiones por presión27,28. La piel de los adultos mayores está seca, lo que provoca roces incluso cuando duermen sobre sábanas. La aplicación de cremas hidratantes, en particular el uso de fórmulas que contengan ceramidas, para hidratar la piel seca a diario se considera una intervención de enfermería eficaz29; por lo tanto, también es importante incorporar esta intervención. Las directrices del Grupo Consultivo Europeo sobre Úlceras por Presión también recomiendan el uso de sábanas de seda u otro material similar en lugar de algodón o mezclas de algodón para reducir la fricción y la fuerza de cizallamiento30.

Teniendo en cuenta los avances en los dispositivos de redistribución de la presión corporal, se ha informado de que el reposicionamiento a intervalos convencionales de 2 horas no difiere del reposicionamiento a intervalos de 3 ó 4horas31. Cuando se reposiciona el cuerpo de un paciente (o se mantiene su postura), se le apoya con cojines y almohadas. Aunque en este estudio se utilizaron camas de hospital de cuatro secciones, los datos de los presentes experimentos se recogieron para el talón con sólo la parte superior del cuerpo de los participantes elevada y sin elevación de la extremidad inferior. Sin embargo, con una cama que permite la elevación de las extremidades inferiores, el posicionamiento convencional requiere la elevación del lado de las extremidades inferiores de la cama para evitar el colapso postural y reducir la presión sobre las nalgas asociada con el deslizamiento hacia abajo de la parte superior del cuerpo; por lo tanto, puede ser necesaria la eliminación de la fuerza externa a través de medios tales como la elevación de las extremidades inferiores. Los cuerpos de los pacientes se reposicionan para cambiar regularmente su posición recostada y desplazar la fuerza externa que, de otro modo, seguiría actuando en el mismo sitio.

Sin embargo, aunque el movimiento voluntario también es importante, a veces resulta difícil para los pacientes que tienen problemas para moverse por sí mismos. En Japón se están realizando estudios sobre los "pequeños cambios", un método de dispersión de la presión corporal que implica el uso de una pequeña almohada. por "pequeños cambios" se entiende un método en el que se desplaza una pequeña almohada a intervalos regulares hasta el hombro, la cadera o la extremidad inferior de un lado del cuerpo para cambiar el lugar sobre el que actúa la presión y redistribuir así la presión. Se ha demostrado que este método reduce la incidencia de lesiones por presión32,33. Además, se ha desarrollado un colchón de aire equipado con un sistema de cambio tan pequeño, y un estudio ha informado sobre su eficacia para prevenir las lesiones por presión34.

Junto con las medidas descritas anteriormente para prevenir las lesiones por presión en el talón, también se está utilizando la ultrasonografía para detectar lesiones por presión en una fase temprana sin depender de la evaluación visual35. Puede ser necesario adquirir datos más básicos, como los obtenidos en el presente experimento.

Se necesitan más comentarios sobre lo que se sabe actualmente acerca de las intervenciones de enfermería, como el reposicionamiento, la frecuencia de los reposicionamientos para reducir la presión, la fuerza de cizallamiento y la fricción, y el uso de un reposapiernas o de la capacidad de elevación de las rodillas de las camas o de dispositivos sencillos como almohadas, etc. para aliviar la presión de cizallamiento y fricción de los talones.

Limitaciones del estudio y retos futuros

En este estudio, el grupo de edad objetivo era relativamente joven. Su estructura cutánea en la región del talón difiere de la de los adultos mayores, que son más propensos a sufrir lesiones por presión, y existen limitaciones a la hora de comparar con pacientes más propensos a sufrir lesiones por presión. El colchón utilizado era de uretano, que se emplea para prevenir las lesiones por presión; por tanto, en el futuro habrá que examinar los efectos del uso de otros materiales, como un colchón de aire.

Basándonos en estos resultados, pretendemos considerar en el futuro métodos de posicionamiento y redistribución de la presión más relevantes desde el punto de vista clínico. Además, nos gustaría comprobar los cambios que se producen no sólo en la región del talón, sino también en la región sacra y en otros lugares de protrusión ósea, y recopilar datos para aportar pruebas a la práctica enfermera.

Conclusiones

Cuando se realizó la elevación, la presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento en el talón aumentaron significativamente en 30˚. La elevación de las extremidades inferiores provocó una descarga de la presión continua y de la fuerza de cizallamiento en el talón, aunque las diferencias no fueron significativas. Sin embargo, observamos la presión y la fuerza de cizallamiento que se producían al elevar la cabecera de la cama y determinamos que la elevación de las extremidades inferiores, un acto típico de los cuidados de enfermería, no evita la aplicación de fuerza de cizallamiento. Se realizarán nuevos exámenes con datos más objetivos para analizar las intervenciones preventivas de enfermería.

Agradecimientos

Agradecemos a todos los participantes en el estudio por su colaboración. También queremos dar las gracias a Editage (www.editage.com) por la edición en inglés

Conflicto de intereses

No hay conflictos de intereses que declarar.

Declaración ética

El estudio fue aprobado por el Comité de Revisión Ética de la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Jikei de Tokio (9212).

Financiación

Este estudio recibió una beca de investigación de la Escuela de Enfermería de la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Jikei. Sin embargo, no participaron en ningún aspecto del contenido del estudio, incluidos el diseño del estudio, la recogida de datos, el análisis o la interpretación de los datos; sólo aportaron financiación.

Author(s)

Yoko Murooka*

RN, PhD, WOCN

Faculty of Nursing, Tokyo University of Information Sciences,

4–1 Onaridai, Wakaba-ku, Chiba, 265–8501 Japan

Email myoko0913@gmail.com

Hidemi Nemoto Ishii

RN, MSN, ET/WOCN

Wound & Ostomy Care Division, ALCARE Co. Ltd., Sumida-ku,

Tokyo, Japan

* Corresponding author

References

- Manorama A, Meyer R, Wiseman R, Bush T. Quantifying the effects of external shear loads on arterial and venous blood flow: implications for pressure ulcer development. Clin Biomech 2013;28(5):574–78.

- Leyva-Mendivil MF, Lengiewicz J, Page A, et al. Skin microstructure is a key contributor to its friction behaviour. Tribol Lett 2017;65(1):12.

- Vianna V, Broderick L, Cowan L. Pressure injury related to friction and shearing forces in older adults. J Dermatol & Skin Sci 2021;3(2):9–12.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: clinical practice guideline. The International Guideline. Emily Heasler, editor. EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA 2019.

- Mimura M, Okazaki H, Kajiwara T, et al. Variation of body pressure and shear force during bed manipulation (Part 1): effect of body shape and bed manipulation. J Jap Soc Bedsores 2007;9:11–20 (in Japanese).

- Ishikawa H, Hata M, Kondo Y. The effect of back-pulling during head-up and head-down. Asahikawa Red Cross Hosp Med J 2011;31–33 (in Japanese).

- Mori M, Endo A, Oshimoto Y. Fabrication of a cushion to reduce pressure on the buttocks during back elevation and a study of its effectiveness. J Jap Soc Bedsores 2010;12:509–12 (in Japanese).

- Y, Otsuka N, Ibe F, et al. Relationship of 45˚ head-side up and knee elevation and local pressure at the sacral region. Jap J PU 2009;11(1):40–6.

- Harada C, Shigematsu T, Hagisawa S. The effect of 10-degree leg elevation and 30-degree head elevation on body displacement and sacral interface pressures over a 2-hour period. J WOCN 2002:29(3):143–48.

- Lippoldt J, Pernicka E, Staudinger T. Interface pressure at different degrees of backrest elevation with various type of pressure-redistribution surfaces. Am J Crit Care 2014;23(2):119–26.

- Defloor T. The effect of position and mattress on interface pressure. Appl Nurs Res 2000;13(1):2–11.

- Anderwee K, Clark M, Dealey C, et al. Pressure ulcer prevalence in Europe: a pilot study. J Eval Clin Pract 2007;13(2):227–35.

- VanGilder C, Macfarlane GD, Meyer S. Results of nine international pressure ulcer prevalence surveys: 1989 to 2005. Ostomy Wound Manage 2008;54(2):40–54.

- VanGilder C, Amlung S, Harrison P, Meyer S. Results of the 2008–2009 International Pressure Ulcer Prevalence Survey and a 3-year, acute care, unit specific analysis. Ostomy Wound Manage 2009;55(11):39–45.

- VanGilder C, Lachenbruch C, Algrim-Boyle C, Meyer S. The International Pressure Ulcer Prevalence Survey 2006–2015: a 10-year pressure injury prevalence and demographic trend analysis by care setting. J WOCN 2017;44(1):20–8.

- Gefen A. Why is the heel particularly vulnerable to pressure ulcers? Br J Nurs 2017;26(Sup20):S62–S74.

- Nakagami G, Sanada H, Konya C, et al. Comparison of two pressure ulcer preventive dressings for reducing shear force on the heel. J WOCN 2006;33(3):267–72.

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91.

- Okubo Y, Kohase M, Ogawa KI. Influence of raising and lowering the back of the bed on the body. J Jap Soc Bedsores 2000;2:45–50 (in Japanese).

- Grey JE, Harding KG, Enoch S. Pressure ulcers. BMJ 2006;332:472–75.

- Okuwa M, Sugama J, Sanada H, et al. Measuring the pressure applied to the skin surrounding pressure ulcers while patients are nursed in the 30 degree Position. J Tissue Viab 2005;15(1):3–8.

- The Japanese Society of Pressure Ulcers Guideline Revision Committee. JSPU guidelines for the prevention and management of pressure ulcers (4th ed.). Jpn J PU 2015;17(4):487–557.

- McCreath HE, Bates-Jensen BM, Nakagami G, et al. Use of Munsell Color Charts to objectively measure skin color in nursing home residents at risk for pressure ulcer development. J Adv Nurs 2016;72(9):2077–85.

- Gefen A. Tissue changes in patients following spinal cord injury and implications for wheelchair cushions and tissue loading: a literature review. Ostomy Wound Manage 2014;60(2):34–45.

- Takahashi M, Shimomichi M, Ohura T. Effects of pressure and shear force on blood flow in the radial artery and skin capillaries. J Jap Soc Bedsores 2012;14:547–52 (in Japanese).

- Takeda T. An experimental study on the effects of friction and displacement on the occurrence of bedsore. J Jap Soc Bedsores 2001;3:38–43 (in Japanese).

- Santamaria N, Gerdtz M, Sage S, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of soft silicone multi-layered foam dressings in the prevention of sacral and heel pressure ulcers in trauma and critically ill patients: the border trial. Int Wound J 2013;12(3):302–8.

- Ferrer Solà M, Espaulella Panicot J, Altimires Roset J, et al. Comparison of efficacy of heel ulcer prevention between classic padded bandage and polyurethane heel in a medium-stay hospital: randomized controlled trial. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2013;48(1):3–8.

- Takeshi K, Yoshiki M, Makoto K. Clinical significance of the water retention and barrier function: improving capabilities of ceramide-containing formulations: a qualitative review. J Dermatol 2021;48(12):1807–16.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: quick reference guide. Available from: http://tinyurl.com/yck2mmr6

- Moore Z, Cowman S, Conroy RM. A randomized controlled clinical trial of repositioning, using the 30˚ tilt, for the prevention of pressure ulcers. J Clin Nurs 2011;20(17–18):2633–44.

- Brown MM, Boosinger J, Black J, et al. Nursing innovation for prevention of decubitus ulcers in long term care facilities. Plast Surg Nurs 1985;5:57–64.

- Smith AM, Malone JA. Preventing pressure ulcers in institutionalized elders: assessing the effects of small, unscheduled shifts in body position. Decubitus 1990;3:20–4.

- Dai M, Yamanaka T, Matsumoto M, et al. Effectiveness of the air mattress with small change system on pressure ulcer prevention: a pilot study in a long-term care facility. J Jap WOCM 2018;22(4):357–62.

- Nagase T, Koshima I, Maekawa T, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of an unusual peri-anal induration: a possible case of deep tissue injury. J Wound Care 2007;16(8):365–7.