Volume 43 Number 1

Self-treatment of abscesses by persons who inject intravenous drugs: a community-based quality improvement inquiry

Janet L Kuhnke, Sandra Jack-Malik, Sandi Maxwell, Janet Bickerton, Christine Porter, Nancy Kuta-George

Keywords quality improvement, abscesses, self-care treatment, persons who inject drugs

For referencing Kuhnke JL et al. Self-treatment of abscesses by persons who inject intravenous drugs: a community-based quality improvement inquiry. WCET® Journal 2023;43(1):28-34

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.1.28-34

Submitted 8 August 2022

Accepted 19 October 2022

Abstract

Objective This study had two objectives. First, to understand and then describe the experiences of persons who inject drugs (PWID) and who use self-care treatment(s) to deal with resulting skin and tissue abscesses. Next, to understand and describe their journeys to and experiences with formal healthcare service provision.

Methods Semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten adults who have experience with abscesses, engage in self-care treatment(s), and utilise formal healthcare services in Nova Scotia, Canada.

Results Participants lived with abscesses and utilised various self-treatment strategies, including support from friends. Participants engaged in progressive self-care treatment(s) as the abscesses worsened. They reluctantly made use of formal healthcare services. Finally, participants discussed the importance of education. Moreover, they shared their thoughts in terms of how service provision could be improved.

Conclusions Participants described their lives, including their journeys to intravenous drug use. They also described the self-care treatments they used to heal resulting abscesses. They used these self-care treatments because of a reluctance to utilise formal healthcare services. From a quality improvement perspective, participants outlined suggestions for: 1) expanding hours of service at the community wound care clinic and the centre; 2) permitting pharmacists to include prescribing topical and oral antibiotics; 3) promoting abscess prevention education for clients and healthcare providers; and 4) promising practices for the provision of respectful care during emergency care visits.

Introduction

Persons who inject drugs (PWID) intravenously normally aim to inject a vein using a hypodermic needle and syringe1. When they miss the vein (missed hit) it may lead to skin and soft tissue injuries (SSTIs), cellulitis and/or abscess formation in varied anatomical sites2–11. An abscess contains a collection of pus in the dermis or sub-dermis and is characterised by pain, tenderness, redness, inflammation and infection12. Larney et al13 reported a lifetime prevalence (6–69%) of SSTIs and abscesses for PWID. These are most often caused by bacterial infections (Staphylococcus aureus, Methicillin-resistant S. aureus) and may lead to the development of deep vein thrombosis, osteomyelitis, septicaemia and endocarditis, thereby increasing morbidity and mortality14–16.

Abscesses require prompt attention to minimise resulting complications. This attention often includes emergency visits and hospitalisations17–19. However, PWID avoid seeking formal healthcare services (e.g., community clinics, physician offices, emergency care teams) for a variety of reasons and therefore they often engage in self-care treatment(s)20–22. Reasons for their reluctance to utilise formal healthcare services include experiencing lengthy clinic and emergency wait times, being judged and feeling discriminated against by care providers and the resulting experience of being othered23, and being asked questions about their drug use24,25. In addition, PWID may delay accessing formal healthcare services due to a fear of drug withdrawal and inadequate pain management26. Reluctance to seek out and utilise formal healthcare services can result in self-care treatment(s), including attempts to lance and drain abscesses20–22.

Our goal was to understand and describe the experiences of PWID and who use self-care treatment(s) and to understand and describe their journeys to and experiences with formal healthcare service provision. We also wanted to listen to and record their recommendations for the improvement of services. This was a significant goal of the research because it has the potential to prevent and decrease the number of abscesses resulting in hospital visits and admissions and, ultimately, to decrease the number of related deaths and suffering.

Frameworks guiding this study

Informed by the harm reduction focus of Nova Scotia’s Opioid use and overdose framework27 and utilising a quality improvement approach28, we sought to engage in semi-structured interviews with PWID to understand their experiences and their recommendations for how to improve community-based abscess care. Freire guided this study and our approach when he wrote “... human existence cannot be silent, nor can it be nourished by false words, but only by true words, with which men and women transform the world”29(p88). Knowing much of the suffering and resulting deaths are preventable, our goal was to listen carefully and respectfully to participants, such that their voices become part of the solution.

Methods

The study was conducted in partnership with a harm reduction centre (the centre) and university researchers. Qualitative data were collected from PWID using semi-structured interviews30,31. Several visits to the centre occurred to develop trust with the centre’s team and potential participants32,33. The centre offers primary healthcare services to populations including those living with substance use disorder(s), those experiencing homelessness, and sex workers34,24. Funding for the study was provided by a Cape Breton University Research Dissemination Grant.

Participants

Participants included ten adults (PWID and 18+ years) who experienced abscess(es), engaged in self-care treatment(s), utilised formal healthcare services, and expressed an interest in the interview at the time of data collection.

Data collection

Adults accessing the centre were approached by the centre’s team to see if they wanted to participate. Interviews were conducted in a quiet space of the participants’ choice and snacks were offered. Interviews of 45–60 minutes using a semi-structured script occurred. After four were completed, we listened to the interviews (triangulation) to ensure the questions were respectfully resulting in useful data28. The interview questions explored participants’ knowledge of abscess risk, characteristics of an abscess, education of safe injection practices, including skin hygiene, and experiences when utilising healthcare services. We also invited participants to describe recommendations for improvement to the provision of abscess care. We regularly communicated the study progress with the team. Throughout the study we adhered to pandemic guidance35.

Research ethics

Approval for the study was granted by Cape Breton University. Adults who met the inclusion criteria received, discussed and were invited to ask and have answered their questions. A letter of information was provided and written informed consent was obtained. Data collected included gender, age, age of first abscess, products, medications used to self-treat, and when and to whom they reached out for formal healthcare. A CA$25 gift card was given to each participant after the interview was complete.

Data analysis

Data were recorded, secured, and transcribed verbatim30–32. We read and re-read the transcripts, seeking patterns and themes. From the analysis, four themes emerged: 1) lack of experiential knowledge; 2) progression of self-treatment strategies; 3) utilisation of formal healthcare; 4) education matters; do not rush. We discussed the themes to ensure we captured the essence of the participants’ stories. Findings are presented in a narrative format with participants’ quotes embedded; identifying characteristics were removed and comments were edited for clarity.

Findings

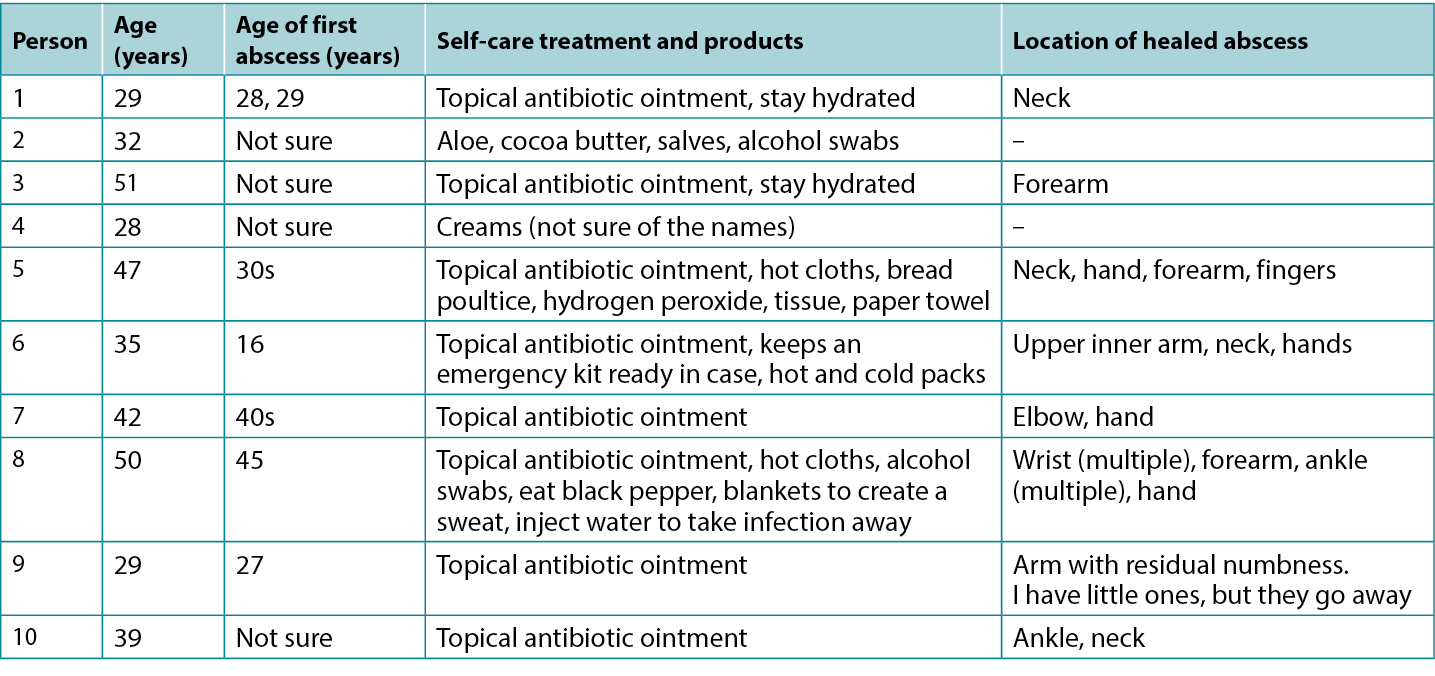

Ten participants, four women and six men, who experienced one or more abscess(es) participated (mean age 38.5 years; range 29–51 years). Five participants were unsure of the date of their first abscess, two identified a range of dates, and three knew the specific date as they included a critical hospital event. One participant had an active skin infection and seven showed the locations of one or more healed abscess sites (Table 1).

Table 1. Participants’ Description of self-care treatment(s)

Theme 1: lack of experiential knowledge

When first injecting drugs, participants described limited knowledge of skin infections, cellulitis and abscess(es). One participant shared “I thought I was the perfect user, I never thought I would get an abscess”. Another stated “I didn’t know what the redness was – the cellulitis; a nurse taught me. I did not know it had become an abscess as I still played sports”. Another participant knew the risks and thought abscesses were inevitable – “I knew you could get them wherever you inject!” Coming to understand the risks varied for participants:

The abscess, was so, so painful. I could not sleep, I was scared; I did not know what it was. My hand was blowing up! I could not work. It was not until someone told me my hand was infected that I panicked. I ended up going to the hospital.

The pill or dirt in the cocaine or whatever was added will build up in your system and cause an abscess, I learned this over time. The dirty needle and water made it worse. Your body pushes the foreign substance out, you have headaches, your tired, all your blood is going to the wound to try to heal it. The area is hot. It feels like it is dragging you toward death. I thought I was dying.

The pain was extreme and unbearable. I hid the wounds. I used to miss the vein if I was shaking and rushing to inject. Some pills like Ritalin, hydromorphone, Dilaudid, and Effexor were worse than others. I did not get them from cocaine. I had abscesses in my hands, wrists, ankles. My teeth got abscessed due to the infections, I lost all my teeth; I have dentures.

Theme 2: progression of self-treatment strategies

Participants described engaging in abscess self-care treatment(s) and identified additional steps taken if the abscess worsened. They also described extreme pain when pressing the abscess(es) with their fingers to pop or squeeze the abscess, or when using a pen knife, surgical blades or a big needle to lance, drain or draw out the infection from the infected area(s). These activities may take place in a kitchen, bathroom (e.g., work, public, home), or bedroom alone or with a friend. One participant described his self-care:

I use soap, water, or what I can find to clean it. I try to keep it covered. I use clean needles or blades to lance it myself. If it does not fill back up with stuff, I leave it alone. I have stuffed bread in them before, the bread turns green and takes the infection out. It helps. I have had quite a few, the last one was on my finger. It is fine now, but it was discoloured. These were not the nasty ones. I have had to clean abscesses on my hands and legs, but they were not so bad that I had to go to the hospital. When I have them bad, they physically drain me, literally like I am dragging around, exhausted.

Participants explained that self-care treatment(s) changed as the abscess worsened. For example:

If it was infected, I would get half a prescription of antibiotics from someone else. I drank water to flush out the infection. I kept a face cloth on top of the abscess to collect the drainage. It is important to clean your skin first with alcohol swabs to reduce the bacteria. I used antibiotic ointment on small abscesses unless the redness did not go away. I got free antibiotic pills, some people charge each other, but I do not, that’s mean. Sometimes I used a hot facecloth on the area. I drain the abscesses myself, I use aloe, a topical antibiotic, and if it gets worse, I try to get an oral antibiotic from a friend at no charge, it is not good to charge money you know, you could die. I try to get a three-day supply. At first, I did not know what to do. I started treating the abscess with hot water, then cold, then both. I bought a heat bag to put on it to draw out the infection. I told the nurses at the centre, and they drew a line around it. These are my six, three, and two-inch scars. See the length? They were bad ones.

Friends help me

One participant said that, when they have an abscess, they may tell a partner or friend. Participants stated partners or loyal friends would do the following – help incise and drain an abscess in any location, find topical and oral antibiotics and not charge them, and locate wound supplies. Friends would help organise or drive them to an appointment (e.g., doctor, nurse, nurse practitioner, clinic, emergency department). Participants shared the following:

There is a code on the street you know, abscesses can kill you, so you help each other. My friend had an abscess, I cleaned it for him with alcohol, it burned, it helped. If I need help with my abscesses he would help me too, we would, just get, like you know, a topical antibiotic from, like, from like, wherever… [pauses & smiles]. My friends will help if I ask. But I usually treat the abscess myself. With my first abscess I got a hot fever, so I wrapped myself in four blankets. Ate black pepper. I injected water to take it away, it does not last long. My blood went septic with a big abscess, my friend took me for care.

Increasing sense of urgency

Four participants described urgency related to a worsening abscess:

I would only wait a day before getting care from the nurses. I would not wait longer. I do not rely on anyone else to know how bad my skin is, that is my job. Abscesses can kill you. I get care right away. I got care for my wrist abscess from the community nursing team. I am prepared, I keep a kit ready for abscesses in case… people die. My last one in my elbow was so big I could fit a whole roll of gauze in the hole. The home care nurses helped me. I know I can come to the centre for care, they are amazing, I rely on them.

Another shared:

Supplies for abscesses are not easy to find, the pharmacies are expensive, I get what I need at no cost, this is serious stuff. It should be easier to get basic antibiotic prescriptions. Why is it so hard to get oral antibiotics? Why can’t a pharmacist order it? Why can’t nurses do this? I could die.

From these comments we began to understand self-care as part of a continuum of care and we understood PWID quickly experience how fast abscesses can become serious and the resulting need to seek out formal healthcare providers.

Theme 3: utilisation of formal healthcare

Participants preferred to receive abscess care at the community nursing wound clinic or the centre where they were respected. Participants expressed concern when interacting with emergency care teams (the three provinces mentioned were Alberta, Ontario and Nova Scotia) because it regularly evoked feelings of shame and being judged when asked assessment questions and planning abscess care (e.g., returning to emergency, hospitalisation). Their reluctance to access or remain in care once assessed was related to prior experiences. Participants shared:

It would take a lot for me to ask for help! I would have to be really sick to ask for help from the hospital! We really need a safe injection site, then the abscesses would not be happening. I would cut open my abscess myself ahead of going to the hospital. I would get oral antibiotics first from someone, then if it got worse, I would go to the hospital. It would be my last stop. There should be a priority for abscess care at the hospital. Why can’t I get care from a pharmacy or pharmacist? If you need intravenous antibiotics four times a day, and you can hardly make up your mind to plan to go back to the hospital… it is not a surprise that I did not go back. Many people do not have cars or parking money, so we do not go back! If you miss a dose, it is worse, as you must be readmitted and wait, wait, and wait.

Respectful care

Participants shared experiences of receiving respectful care and negotiating with the team.

My abscess was so infected I went for care. They were good to me. I needed care, I went to emergency, they treated me well. I was ashamed to go, I just knew I had to get there. I went alone. They let me have a cigarette, so I stayed.

I did not want to go to the hospital. People were initially judgemental. They asked me about being an intravenous drug user, then they backed up in the room. I did not like this. Yet, they did drain my hand. The care was okay… actually, it was good when the walls come down and you know you are accepted, care was good for me.

The hospital was okay. I just focused on the abscess. They treated me good, they were fair. The abscess smelled so bad when they cut it open. I have not experienced stigma at the hospital. They were good to me; I waited a few hours and it was okay. Everyone else was waiting for care too. You have to be kind and put out kindness, then they will be kind to you.

I went to emergency and the doctors and nurses treated me well. I went back twice a day, for three days and then I took a week of oral antibiotics. It saved my life, from the sepsis. I could have died (tears up). I was treated well in emergency, though I do hear negative stories. I was really scared, yet, I got good care from the team. I would tell people to go to emergency, after I treat the area myself.

I would never lance my abscess. I am too afraid. I got good care in ambulatory care, they used iodine and lots of packing, I think I got the good nurses. They were kind to me, that matters. I do not want to be looked down on by anyone as that upsets me.

I went for care, they were good to me. When I need antibiotics, I go and get them. I do not get them from people on the street. I do not want to take a chance on my life. People will sell you anything and call it an antibiotic. I know I get embarrassed when I ask for help, but that is me. I needed care.

During the pandemic, I received a virtual wound assessment and then I felt better. They taught me to mark the edges of the redness and told me that if it gets redder to go to emergency. Well, I went to emergency and got good care. My emergency visit was better as I did not go alone, having a support person with me was a huge help – then I did not leave.

We understand this theme as a counter to the narrative of avoiding hospital care. PWID understand there are times when hospital care is necessary. In addition, counter to stories that circulate among PWID, hospital care may be experienced as respectful.

Theme 4: education matters; do not rush

Participants expressed the importance of education related to the safe injection of drugs and skin hygiene. Each participant reflected on the person(s) who initially taught them how to inject drugs and practise skin hygiene. They described the risks of a missed hit, when they inadvertently injected into the fatty, subcutaneous or intramuscular layers, or when the drugs leaked into the skin. One participant learned how to inject from an internet video. Another learned from a former partner who taught him to use new filters and needles:

She taught me about cotton fever as I was doing it wrong. As well, I was using little veins with a big needle and got an abscess. No one taught me, I learned from other people using. I have only had one abscess from missing, and it made my upper arm and breast area swell. I could not sleep and could not use my arm and hand. Someone could show you a bad, bad, bad technique. You must see blood, then you push it in, the correct way matters. Education sessions should remind people to not rush, if they do not see blood, do not inject. People are rushing to inject, do not rush, no blood – no injecting, then you will not miss. Also, if you are not feeling good and you are relying on someone else to inject you, that is not good as the person may rush and miss.

Four participants expressed they learned how to safely inject from nurses at the centre. They readily described the importance of using clean equipment, cookers, needles and cleansing the skin with alcohol swabs. Three stated education classes should include correct injecting techniques, discussions of the risk of missing, and pictures of SSTIs and abscesses to compare their abscess to in order to determine the level of seriousness.

Discussion

This small quality improvement study28 was conducted at a harm reduction centre in partnership with university researchers. Purposeful recruiting from the centre’s clientele may have influenced findings because of the centre’s mandate32. Interview data revealed thick descriptions30,31. Findings demonstrate that PWID experience a learning curve related to injection and abscesses. Participants most often begin with self-care and utilise formal healthcare services when they experience urgency as the wound worsens. Participants’ answers demonstrate understanding of the risks, a desire to heal from and or prevent abscesses, and the human need to be treated respectfully. From a quality improvement perspective, they outlined improvements including suggestions for: 1) expanding hours of service at the community wound care clinic and the centre; 2) permitting pharmacists to include prescribing topical and oral antibiotics; 3) promoting abscess prevention education for clients and healthcare providers; and 4) promising practices for the provision of respectful care during emergency care visits.

Dechman and colleagues discussed the complex and unique journeys PWID experience24. PWID aim to inject drug(s) intravenously and do not plan to miss or inadvertently inject into the tissues (subcutaneous or intramuscular)2. Our findings showed participants, when first injecting, do not always know about SSTIs and abscess formation from bacterial or viral sources. However, over time they learn the seriousness of missing the vein (e.g., peripheral, femoral, neck). They also learn the risk associated with sharing or re-using equipment, the relationship to the development of collapsed and sclerosed veins, cellulitis, abscess(es), and serious infections. Participants were able to consistently describe early and late signs of abscesses21,36. Moreover, once participants knew they had an abscess, they began with self-care interventions. If improvement was not experienced, they accessed formal healthcare. These findings demonstrate PWID are knowledgeable, begin with self-care and when required will seek out formal care, regardless of the reticence. We understand this process as a meaningful continuum of care. They also described the importance of maintaining and growing the wound care nurse role in the Ally Centre and with the community nursing teams.

Need for acute care and resulting reticence

For participants there was reluctance to seek formal healthcare though they understand abscess(es) lead to sepsis, hospitalisation and death24. Participants want to be treated respectfully when engaging in acute care. Reluctance was related to perceptions of formal healthcare staff and fears of being disrespected. Participants want to be treated respectfully throughout the entire encounter. They also required access to reliable transportation and parking fees. Waiting at the hospital was not preferred, though having a friend and being able to go outside for a cigarette eased the waiting time. Participants recommend healthcare professionals receive education related to the compassionate and respectful care of PWID and living with skin and wound complications33.

Antibiotic stewardship

Antibiotic stewardship for PWID is of concern and challenging to address37,38. Participants discussed the need for pharmacists to be involved in prescribing antibiotics. Topical and oral antibiotics may be consumed as prescribed, shared with another person whose abscess is judged to be worse, given or sold to another, or kept secure for future use20–22. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends consistent education related to correct use of antibiotics39. For PWID this translates to accessible education materials (e.g., online, printed and workshops)21 and consistent and easy access to new equipment used to prepare and inject a drug(s)37,40.

Harvey and colleagues40 surveyed healthcare professionals’ knowledge about the prevention of infection in PWID. Professionals disclosed they received little to no education on harm reduction, were not comfortable counselling PWID, and lacked knowledge on where to refer PWID for education or supplies. To reduce PWID morbidity and mortality, Harvey et al developed the “Six moments of infection prevention in injection drug use provider educational tool”40(p.1). The toolkit emphasises a broad framework focused on infection prevention for PWID.

Participants in this study repeatedly shared they were willing to learn, and they wanted to be safe to avoid complications. They requested development of videos and a phone application (app) depicting mild cellulitis to complex abscesses. There are risks associated with the latter request, as solely relying on wound images as a diagnostic tool for mild, progressing and serious infections is not recommended36.

Conclusion

In this study, participants became knowledgeable about SSTIs and abscess development. Though they were aware of the risks of (mortality, morbidity), they remained reluctant to access formal healthcare. More research is needed to fully understand the maintenance and expanding of wound care services, including the role of pharmacists in the community. In addition, education for PWID was a consistent message, and PWID want consistent credible materials from which to learn. Finally, PWID want to know they will be respected when accessing healthcare services. Our experience of the interviews left us wondering how best to describe the humility, intelligence and kindness of the participants. They were thoughtful, and wanted to improve the experience for themselves and others.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants for sharing their stories and for their thoughtful recommendations.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Autotratamiento de abscesos por personas que se inyectan drogas intravenosas: una investigación comunitaria para la mejora de la calidad

Janet L Kuhnke, Sandra Jack-Malik, Sandi Maxwell, Janet Bickerton, Christine Porter, Nancy Kuta-George

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.1.28-34

Resumen

Objetivo Este estudio tenía dos objetivos. En primer lugar, comprender y luego describir las experiencias de las personas que se inyectan drogas (PWID) y que utilizan tratamiento(s) de autocuidado para hacer frente a los abscesos cutáneos y tisulares resultantes. A continuación, comprender y describir sus trayectorias y experiencias con la prestación de servicios sanitarios formales.

Métodos Se realizaron entrevistas semiestructuradas a diez adultos con experiencia en abscesos, que practican tratamientos de autocuidado y utilizan servicios sanitarios formales en Nueva Escocia (Canadá).

Resultados Los participantes vivían con abscesos y utilizaban diversas estrategias de autotratamiento, incluido el apoyo de amigos. Los participantes aplicaron tratamientos progresivos de autocuidado a medida que empeoraban los abscesos. Eran reticentes al uso de los servicios sanitarios oficiales. Por último, los participantes debatieron la importancia de la educación. Además, compartieron sus ideas sobre cómo mejorar la prestación de servicios.

Conclusiones Los participantes describieron sus vidas, incluida su trayectoria hacia el consumo de drogas intravenosas. También describieron los tratamientos de autocuidado que utilizaron para curar los abscesos resultantes. Recurrían a estos tratamientos de autocuidado por su reticencia a utilizar los servicios sanitarios formales. Desde la perspectiva de la mejora de la calidad, los participantes esbozaron sugerencias para: 1) ampliar las horas de servicio en la clínica comunitaria de atención de heridas y en el centro; 2) permitir que los farmacéuticos incluyan la prescripción de antibióticos tópicos y orales; 3) promover la educación en prevención de abscesos para clientes y proveedores de atención sanitaria; y 4) prácticas prometedoras para la prestación de una atención respetuosa durante las visitas de atención de emergencia.

Introducción

Las personas que se inyectan drogas por vía intravenosa (PWID) normalmente intentan inyectarse en una vena utilizando una aguja hipodérmica y una jeringuilla1. Cuando no alcanzan la vena (golpe fallido), pueden provocar lesiones en la piel y los tejidos blandos (SSTI), celulitis y/o formación de abscesos en diversas localizaciones anatómicas2-11. Un absceso contiene una acumulación de pus en la dermis o la subdermis y se caracteriza por dolor, sensibilidad, enrojecimiento, inflamación e infección12. Larney et al13 informaron de una prevalencia a lo largo de la vida (6-69%) de las SSTI y abscesos para las PWID. Éstas suelen estar causadas por infecciones bacterianas (Staphylococcus aureus, S. aureus resistente a la meticilina) y pueden conducir al desarrollo de trombosis venosa profunda, osteomielitis, septicemia y endocarditis, aumentando así la morbilidad y la mortalidad14-16.

Los abscesos requieren una atención rápida para minimizar las complicaciones resultantes. Esta atención suele incluir visitas a urgencias y hospitalizaciones17-19. Sin embargo, las PWID evitan acudir a los servicios sanitarios formales (p. ej., centros de salud, consultorios médicos, equipos de atención de urgencias) por diversas razones, por lo que a menudo recurren a tratamientos de autocuidado20-22. Entre los motivos de su reticencia a utilizar los servicios sanitarios formales se encuentran los largos tiempos de espera en las clínicas y en urgencias, el hecho de ser juzgados y sentirse discriminados por los profesionales sanitarios, con la consiguiente experiencia de sentirse marginados23, y ser preguntados sobre su consumo de drogas24,25. Además, las PWID pueden retrasar el acceso a los servicios sanitarios formales por miedo a la abstinencia de drogas y a un tratamiento inadecuado del dolor26. La reticencia para buscar y utilizar servicios sanitarios formales puede dar lugar a tratamientos de autocuidado, incluidos los intentos de extirpar y drenar los abscesos20-22.

Nuestro objetivo era comprender y describir las experiencias de las PWID que viven con el VIH y que utilizan tratamientos de autocuidado, así como comprender y describir su recorrido y sus experiencias con la prestación de servicios sanitarios formales. También queríamos escuchar y registrar sus recomendaciones para mejorar los servicios. Este era un objetivo importante de la investigación porque tiene el potencial de prevenir y disminuir el número de abscesos que dan lugar a visitas e ingresos hospitalarios y, en última instancia, disminuir el número de muertes y sufrimientos relacionados.

Marcos que guían este estudio

Basándonos en el enfoque de reducción de daños del marco de uso y sobredosis de opiáceos de Nueva Escocia27 y utilizando un enfoque de mejora de la calidad28, intentamos realizar entrevistas semiestructuradas con las PWID para comprender sus experiencias y sus recomendaciones sobre cómo mejorar la atención comunitaria de los abscesos. Freire orientó este estudio y nuestro enfoque cuando escribió "... la existencia humana no puede ser silenciosa, ni puede nutrirse de palabras falsas, sino sólo de palabras verdaderas, con las que hombres y mujeres transforman el mundo "29(p88). Sabiendo que gran parte del sufrimiento y las muertes resultantes son evitables, nuestro objetivo era escuchar atenta y respetuosamente a los participantes, de modo que sus voces se convirtieran en parte de la solución.

Métodos

El estudio se realizó en colaboración con un centro de reducción de daños (el centro) e investigadores universitarios. Se recogieron datos cualitativos de las PWID mediante entrevistas semiestructuradas30,31. Se realizaron varias visitas al centro para desarrollar la confianza con el equipo del centro y los posibles participantes32,33. El centro ofrece servicios de atención primaria a poblaciones como las que padecen trastornos por consumo de sustancias, las personas sin hogar y los profesionales del sexo34,24. La financiación del estudio corrió a cargo de una beca de difusión de la investigación de la Universidad Cape Breton.

Participantes

Participaron diez adultos (PWID y mayores de 18 años) que experimentaron absceso(s), se sometieron a tratamiento(s) de autocuidado, utilizaron servicios sanitarios formales y expresaron su interés en la entrevista en el momento de la recogida de datos.

Recogida de datos

El equipo del centro se puso en contacto con los adultos que accedían a él para ver si querían participar. Las entrevistas se realizaron en un espacio tranquilo elegido por los participantes y se les ofreció un refrigerio. Se realizaron entrevistas de 45-60 minutos utilizando un guión semiestructurado. Una vez completadas las cuatro, escuchamos las entrevistas (triangulación) para asegurarnos de que las preguntas se formulaban con respeto y daban lugar a datos útiles28. Las preguntas de la entrevista exploraron los conocimientos de los participantes sobre el riesgo de absceso, las características de un absceso, la educación sobre prácticas seguras de inyección, incluida la higiene de la piel, y las experiencias al utilizar los servicios sanitarios. También se invitó a los participantes a que describieran recomendaciones para mejorar la atención a los abscesos. Comunicamos periódicamente al equipo los avances del estudio. A lo largo de todo el estudio nos adherimos a las directrices sobre pandemias35.

Ética de la investigación

El estudio fue aprobado por la Universidad de Cape Breton. Los adultos que cumplían los criterios de inclusión recibieron, debatieron y fueron invitados a preguntar y a que se respondiera a sus preguntas. Se facilitó una carta informativa y se obtuvo el consentimiento informado por escrito. Los datos recogidos incluían sexo, edad, edad del primer absceso, productos, medicamentos utilizados para autotratarse, y cuándo y a quién acudieron para recibir atención sanitaria formal. Se entregó una tarjeta regalo de 25 dólares canadienses a cada participante una vez finalizada la entrevista.

Analisis de datos

Los datos se grabaron, se aseguraron y se transcribieron literalmente30-32. Leemos y releemos las transcripciones en busca de patrones y temas. Del análisis surgieron cuatro temas: 1) falta de conocimiento experiencial; 2) progresión de las estrategias de autotratamiento; 3) utilización de la asistencia sanitaria formal; 4) la educación importa; no hay que precipitarse. Debatimos los temas para asegurarnos de captar la esencia de las historias de los participantes. Los resultados se presentan en formato narrativo con las citas de los participantes incluidos; se eliminaron las características identificativas y se editaron los comentarios para mayor claridad.

Hallazgos

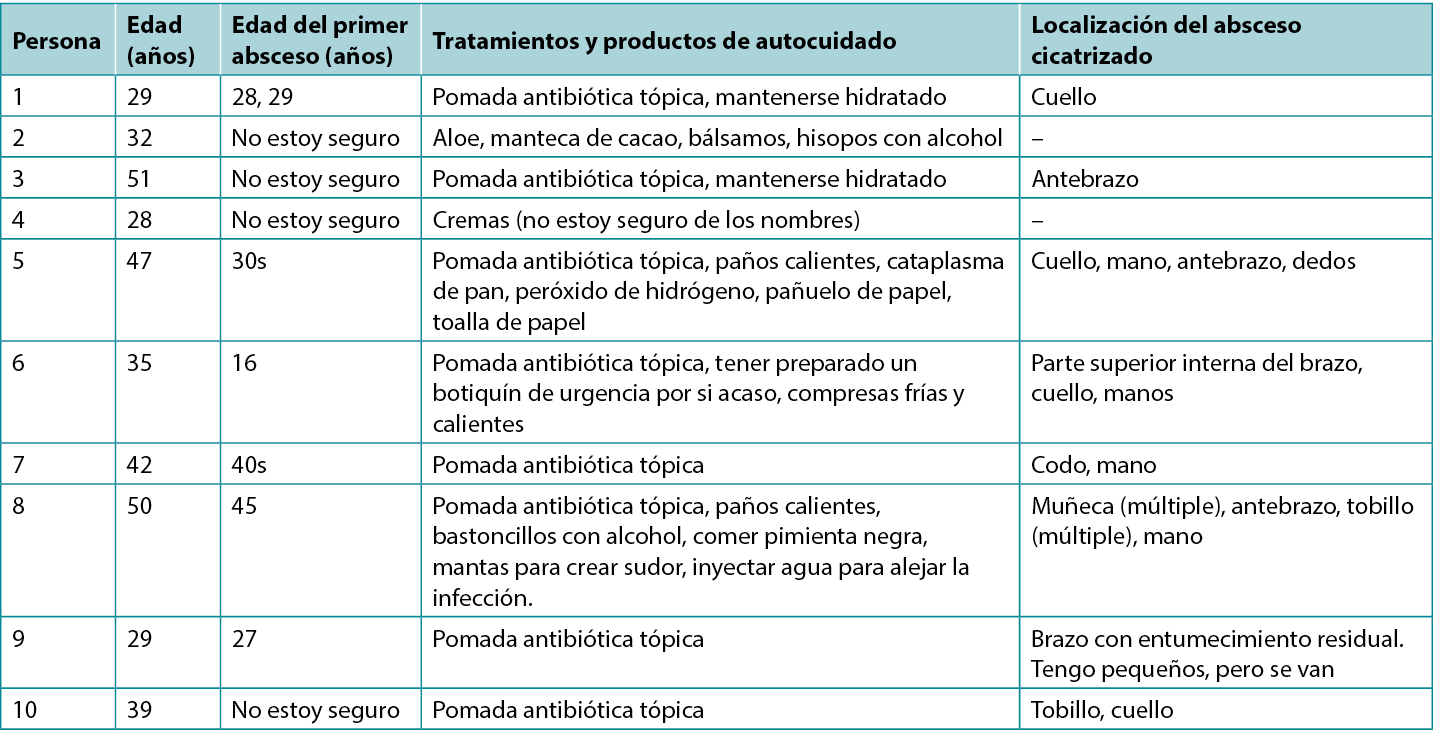

Participaron diez personas, cuatro mujeres y seis hombres, que habían padecido uno o más abscesos (edad media: 38,5 años; intervalo: 29-51 años). Cinco participantes no estaban seguros de la fecha de su primer absceso, dos identificaron un intervalo de fechas y tres conocían la fecha concreta, ya que incluían un acontecimiento hospitalario crítico. Un participante tenía una infección cutánea activa y siete mostraban la localización de uno o más abscesos cicatrizados (Tabla 1).

Tabla 1. Descripción de los tratamientos de autocuidado por parte de los participantes

Tema 1: falta de experiencia

Al inyectarse drogas por primera vez, los participantes describieron un conocimiento limitado de las infecciones cutáneas, la celulitis y los abscesos. Un participante dijo: "Creía que era el usuario perfecto, nunca pensé que me saldría un absceso". Otro declaró: "No sabía lo que era el enrojecimiento, la celulitis; me lo enseñó una enfermera. No sabía que se había convertido en un absceso porque seguía haciendo deporte". Otro participante conocía los riesgos y pensaba que los abscesos eran inevitables: "¡Sabía que te los puedes hacer donde te inyectes!" La comprensión de los riesgos varía según los participantes:

El absceso, era tan, tan doloroso. No podía dormir, tenía miedo; no sabía lo que era. ¡Mi mano estaba que explotaba! No podía trabajar. No fue hasta que alguien me dijo que mi mano estaba infectada cuando entré en pánico. Acabé yendo al hospital.

La píldora o la suciedad de la cocaína o lo que se haya añadido se acumulará en tu sistema y causará un absceso, lo aprendí con el tiempo. La aguja sucia y el agua lo empeoraron. Tu cuerpo expulsa la sustancia extraña, tienes dolores de cabeza, estás cansado, toda tu sangre se dirige a la herida para intentar curarla. La zona está caliente. Se siente como si te arrastrara hacia la muerte. Creí que me moría.

El dolor era extremo e insoportable. Escondí las heridas. Solía perderme la vena si temblaba y me apresuraba a inyectarme. Algunas pastillas como Ritalin, hidromorfona, Dilaudid y Effexor eran peores que otras. No los obtuve de la cocaína. Tenía abscesos en las manos, muñecas y tobillos. Las infecciones me provocaron abscesos dentales, perdí todos los dientes y llevo dentadura postiza.

Tema 2: progresión de las estrategias de autotratamiento

Los participantes describieron la realización de tratamiento(s) de autocuidado del absceso e identificaron las medidas adicionales adoptadas si el absceso empeoraba. También describieron un dolor extremo al presionar el absceso o abscesos con los dedos para reventarlos o apretarlos, o al utilizar una navaja, cuchillas quirúrgicas o una aguja grande para extirpar, drenar o extraer la infección de la zona o zonas infectadas. Estas actividades pueden tener lugar en la cocina, el cuarto de baño (por ejemplo, en el trabajo, en la vía pública o en casa) o el dormitorio, solo o con un amigo. Un participante describió su autocuidado:

Para limpiarlo uso jabón, agua o lo que encuentre. Intento mantenerlo cubierto. Yo mismo uso agujas o cuchillas limpias para extirparlo. Si no se vuelve a llenar de cosas, lo dejo. He metido pan en ellos antes, el pan se pone verde y quita la infección. Ayuda. He tenido bastantes, la última fue en el dedo. Ahora está bien, pero estaba descolorido. Estos no eran los desagradables. He tenido que limpiarme abscesos en las manos y las piernas, pero no eran tan graves como para tener que ir al hospital. Cuando los tengo malos, me agotan físicamente, literalmente como si me arrastrara, exhausto.

Los participantes explicaron que el tratamiento o tratamientos de autocuidado cambiaban a medida que el absceso empeoraba. Por ejemplo:

Si estuviera infectado, conseguiría media receta de antibióticos de otra persona. Bebí agua para eliminar la infección. Mantuve un paño facial encima del absceso para recoger el drenaje. Es importante limpiar primero la piel con bastoncillos con alcohol para reducir las bacterias. Utilicé pomada antibiótica en los pequeños abscesos a menos que el enrojecimiento no desapareciera. Me dieron pastillas antibióticas gratis, algunos las cobran, pero yo no, eso es mezquino. A veces usaba una toallita caliente en la zona. Yo mismo dreno los abscesos, uso aloe, un antibiótico tópico, y si empeora, intento conseguir un antibiótico oral de un amigo sin coste alguno, no es bueno cobrar dinero ya sabes, podrías morir. Trato de conseguir un suministro para tres días. Al principio, no sabía qué hacer. Empecé a tratar el absceso con agua caliente, luego fría y después con ambas. Compré una bolsa de calor para ponérselo y sacar la infección. Se lo conté a las enfermeras del centro y trazaron una línea alrededor. Estas son mis cicatrices de seis, tres y dos pulgadas. ¿Ves la longitud? Había malos.

Los amigos me ayudan

Un participante dijo que, cuando tiene un absceso, puede contárselo a su pareja o a un amigo. Los participantes afirmaron que sus parejas o amigos leales harían lo siguiente: ayudar a incidir y drenar un absceso en cualquier lugar, encontrar antibióticos tópicos y orales y no cobrarlos, y localizar material para heridas. Los amigos les ayudarían a organizar o llevarles a una cita (por ejemplo, con el médico, la enfermera, la clínica, el servicio de urgencias). Los participantes compartieron lo siguiente:

Hay un código en la calle, ya sabes, los abscesos pueden matarte, así que os ayudaís unos a otros. Mi amigo tenía un absceso, se lo limpié con alcohol, quemaba, ayudaba. Si necesito ayuda con mis abscesos, él también me ayudaría, conseguiríamos, ya sabes, un antibiótico tópico de, como ... [pausa y sonríe]. Mis amigos me ayudarán si se lo pido. Pero suelo tratar el absceso yo mismo. Con mi primer absceso tuve fiebre, así que me envolví en cuatro mantas. Comió pimienta negra. Me inyecté agua para quitarlo, no dura mucho. Mi sangre se infectó con un gran absceso, mi amigo me llevó para el cuidado.

Aumento de la sensación de urgencia

Cuatro participantes describieron una urgencia relacionada con el empeoramiento de un absceso:

Sólo esperaría un día antes de recibir atención de las enfermeras. Yo no esperaría más. No confío en nadie más para saber lo mal que está mi piel, ese es mi trabajo. Los abscesos pueden matarte. Me atienden enseguida. El equipo de enfermería comunitaria me atendió de un absceso en la muñeca. Estoy preparado, tengo un kit listo para abscesos en caso de que... la gente muere. El último que me hice en el codo era tan grande que cabía un rollo entero de gasa en el agujero. Las enfermeras de atención domiciliaria me ayudaron. Sé que puedo acudir al centro para que me cuiden, son increíbles, confío en ellos.

Otro compartió:

Los suministros para los abscesos no son fáciles de encontrar, las farmacias son caras, yo consigo lo que necesito sin coste alguno, esto es cosa seria. Debería ser más fácil obtener recetas básicas de antibióticos. ¿Por qué es tan difícil conseguir antibióticos orales? ¿Por qué no puede pedirlo un farmacéutico? ¿Por qué no pueden hacerlo las enfermeras? Podría morir.

A partir de estos comentarios, empezamos a entender el autocuidado como parte de una atención continua y comprendimos que las PWID experimentan pronto la rapidez con la que los abscesos pueden agravarse y la consiguiente necesidad de acudir a proveedores de atención sanitaria formal.

Tema 3: utilización de la asistencia sanitaria oficial

Los participantes preferían recibir la atención de abscesos en la clínica de heridas de la enfermería comunitaria o en el centro donde se les respetaba. Los participantes expresaron su preocupación cuando interactuaban con los equipos de atención de urgencias (las tres provincias mencionadas fueron Alberta, Ontario y Nueva Escocia), ya que les evocaba con frecuencia sentimientos de vergüenza y de ser juzgados cuando les hacían preguntas de evaluación y planificaban la atención del absceso (por ejemplo, volver a urgencias, hospitalización). Su reticencia para acceder a la asistencia o a permanecer en ella una vez evaluados estaba relacionada con experiencias anteriores. Los participantes compartieron:

Me costaría mucho pedir ayuda Tendría que estar muy enfermo para pedir ayuda al hospital Realmente necesitamos un lugar de inyección seguro, entonces los abscesos no estarían ocurriendo. Yo mismo abriría mi absceso antes de ir al hospital. Primero tomaba antibióticos por vía oral y, si empeoraba, iba al hospital. Sería mi última parada. Debe haber una prioridad para la atención de abscesos en el hospital. ¿Por qué no puedo ser atendido en una farmacia o por un farmacéutico? Si necesitas antibióticos intravenosos cuatro veces al día, y apenas puedes decidirte a planear volver al hospital... no es de extrañar que no volviera. Mucha gente no tiene coche ni dinero para aparcar, ¡así que no volvemos! Si se salta una dosis, es peor, ya que debe ser readmitido y esperar, esperar y esperar.

Atención respetuosa

Los participantes compartieron sus experiencias de recibir una atención respetuosa y negociar con el equipo.

Mi absceso estaba tan infectado que fui a que me atendieran. Fueron buenos conmigo. Necesitaba cuidados, fui a urgencias, me trataron bien. Me daba vergüenza ir, pero sabía que tenía que llegar. Fui solo. Me dejaron fumar un cigarrillo, así que me quedé.

No quería ir al hospital. Al principio, la gente me juzgaba. Me preguntaron si consumía drogas por vía intravenosa y retrocedieron en la sala. Esto no me ha gustado. Sin embargo, me drenaron la mano. El cuidado estuvo bien... en realidad, fue bueno cuando las paredes caen y sabes que te aceptan, el cuidado fue bueno para mí.

El hospital estaba bien. Sólo me concentré en el absceso. Me trataron bien, fueron justos. El absceso olía muy mal cuando lo abrieron. No he sufrido ningún estigma en el hospital. Se portaron bien conmigo; esperé unas horas y todo fue bien. Los demás también esperaban para ser atendidos. Tienes que ser amable y ofrecer amabilidad, entonces ellos serán amables contigo.

Fui a urgencias y los médicos y enfermeras me trataron bien. Volví dos veces al día, durante tres días y luego tomé una semana de antibióticos orales. Me salvó la vida, de la sepsis. Podría haber muerto (se le saltan las lágrimas). Me trataron bien en urgencias, aunque he oído historias negativas. Tenía mucho miedo, pero el equipo me atendió muy bien. Le diría a la gente que fuera a urgencias, después de tratar yo mismo la zona.

Nunca extirparía mi absceso. Tengo demasiado miedo. Recibí buenos cuidados en atención ambulatoria, usaban yodo y mucho empaque, creo que me tocaron buenas enfermeras. Fueron amables conmigo, eso importa. No quiero que nadie me menosprecie, porque eso me molesta.

Fui a que me atendieran, se portaron bien conmigo. Cuando necesito antibióticos, voy a por ellos. No me los da la gente de la calle. No quiero arriesgar mi vida. La gente te venderá cualquier cosa y la llamará antibiótico. Sé que me avergüenzo cuando pido ayuda, pero así soy yo. Necesitaba cuidados.

Durante la pandemia, recibí una evaluación virtual de la herida y entonces me sentí mejor. Me enseñaron a marcar los bordes del enrojecimiento y me dijeron que si se ponía más rojo fuera a urgencias. Fui a urgencias y me atendieron bien. Mi visita a urgencias fue mejor porque no fui sola, tener a una persona de apoyo conmigo fue de gran ayuda, por eso no me fui.

Entendemos este tema como una contraposición a la narrativa de evitar la atención hospitalaria. Las PWID entienden que hay momentos en los que la atención hospitalaria es necesaria. Además, en contra de las historias que circulan entre las PWID, la atención hospitalaria puede experimentarse como respetuosa.

Tema 4: la educación importa; no hay que precipitarse

Los participantes expresaron la importancia de la educación relacionada con la inyección segura de fármacos y la higiene de la piel. Cada participante reflexionó sobre la persona o personas que le enseñaron inicialmente a inyectarse drogas y a practicar la higiene de la piel. Describieron los riesgos de errar el tiro, cuando se inyectaban inadvertidamente en las capas grasas, subcutáneas o intramusculares, o cuando los fármacos se filtraban en la piel. Un participante aprendió a inyectarse gracias a un vídeo de Internet. Otro aprendió de un antiguo compañero que le enseñó a utilizar nuevos filtros y agujas:

Ella me enseñó lo que es la fiebre del algodón, ya que yo lo hacía mal. Además, estaba usando venitas con una aguja grande y me salió un absceso. Nadie me enseñó, aprendí de otras personas que utilizaban. Sólo he tenido un absceso por falta, y se me hinchó la parte superior del brazo y la zona del pecho. No podía dormir y no podía utilizar el brazo ni la mano. Alguien podría enseñarte una mala, mala, mala técnica. Tienes que ver la sangre, luego la empujas, la forma correcta importa. Las sesiones educativas deben recordar a la gente que no se precipite, que si no ve sangre, no se inyecte. La gente se apresura a inyectarse, no se apresure, no sangre - no se inyecte, entonces no fallará. Además, si no te encuentras bien y confías en otra persona para que te inyecte, eso no es bueno, ya que la persona puede precipitarse y fallar.

Cuatro participantes manifestaron que habían aprendido a inyectarse de forma segura gracias a las enfermeras del centro. Describieron con facilidad la importancia de utilizar equipos, cocinas y agujas limpios y de limpiar la piel con hisopos con alcohol. Las tres clases de educación declaradas deben incluir técnicas de inyección correctas, debates sobre el riesgo de pérdida y fotografías de SSTI y abscesos con las que comparar sus abscesos para determinar el nivel de gravedad.

Discusion

Este pequeño estudio de mejora de la calidad28 se realizó en un centro de reducción de daños en colaboración con investigadores universitarios. La selección intencionada de la clientela del centro puede haber influido en los resultados debido al mandato del centro32. Los datos de las entrevistas revelaron descripciones detalladas30,31. Los resultados demuestran que las PWID experimentan una curva de aprendizaje relacionada con la inyección y los abscesos. En la mayoría de los casos, los participantes comienzan con el autocuidado y recurren a los servicios sanitarios formales cuando experimentan una urgencia a medida que la herida empeora. Las respuestas de los participantes demuestran la comprensión de los riesgos, el deseo de curarse de los abscesos o de prevenirlos, y la necesidad humana de ser tratado con respeto. Desde la perspectiva de la mejora de la calidad, esbozaron mejoras que incluían sugerencias para: 1) ampliar las horas de servicio en la clínica comunitaria de atención de heridas y en el centro; 2) permitir que los farmacéuticos incluyan la prescripción de antibióticos tópicos y orales; 3) promover la educación en prevención de abscesos para clientes y proveedores de atención sanitaria; y 4) prácticas prometedoras para la prestación de una atención respetuosa durante las visitas de atención de emergencia.

Dechman y sus colegas hablaron de los viajes complejos y únicos que experimentan las PWID24. El objetivo de las PWID es inyectarse la(s) droga(s) por vía intravenosa y no piensan en omitir o en inyectarse inadvertidamente en los tejidos (subcutánea o intramuscular)2. Nuestros hallazgos mostraron que los participantes, cuando se inyectan por primera vez, no siempre conocen las SSTI y la formación de abscesos de origen bacteriano o vírico. Sin embargo, con el tiempo aprenden la gravedad de la omisión de la vena (por ejemplo, periférica, femoral, del cuello). También aprenden el riesgo asociado a compartir o reutilizar material, la relación con el desarrollo de venas colapsadas y esclerosadas, celulitis, abscesos e infecciones graves. Los participantes fueron capaces de describir de forma coherente los signos tempranos y tardíos de los abscesos21,36. Además, una vez que los participantes sabían que tenían un absceso, empezaban con las intervenciones de autocuidado. Si no experimentaban mejoría, accedían a la atención sanitaria formal. Estos resultados demuestran que las PWID están bien informadas, comienzan con el autocuidado y, cuando es necesario, buscan atención formal, independientemente de las reticencias. Entendemos este proceso como una continuidad asistencial significativa. También describieron la importancia de mantener y ampliar el papel de la enfermera especializada en el cuidado de heridas en el Centro Ally y con los equipos de enfermería de la comunidad.

Necesidad de cuidados intensivos y reticencias resultantes

Los participantes se mostraron reacios a buscar asistencia sanitaria oficial, aunque sabían que los abscesos provocan sepsis, hospitalización y muerte24. Los participantes quieren que se les trate con respeto cuando reciben cuidados intensivos. La reticencia estaba relacionada con la percepción del personal sanitario formal y el temor a que se le faltara al respeto. Los participantes quieren que se les trate con respeto durante todo el encuentro. También necesitaban acceso a un transporte fiable y tarifas de aparcamiento. No era preferible esperar en el hospital, aunque tener un amigo y poder salir a fumar un cigarrillo aliviaba el tiempo de espera. Los participantes recomiendan que los profesionales sanitarios reciban formación relacionada con el cuidado compasivo y respetuoso de las PWID y que viven con complicaciones de la piel y las heridas33.

Administración de antibióticos

La administración de antibióticos a las PWID es preocupante y difícil de abordar37,38. Los participantes debatieron la necesidad de que los farmacéuticos participen en la prescripción de antibióticos. Los antibióticos tópicos y orales pueden consumirse según prescripción, compartirse con otra persona cuyo absceso se considere peor, regalarse o venderse a otra, o guardarse para su uso futuro20-22. La Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) recomienda una educación coherente en relación con el uso correcto de los antibióticos39. Para las PWID, esto se traduce en materiales educativos accesibles (por ejemplo, en línea, impresos y talleres)21 y en un acceso fácil y constante a los nuevos equipos utilizados para preparar e inyectarse una droga37,40.

Harvey y sus colegas40 estudiaron los conocimientos de los profesionales sanitarios sobre la prevención de la infección en las PWID. Los profesionales revelaron que habían recibido poca o ninguna formación sobre reducción de daños, que no se sentían cómodos asesorando a las PWID y que no sabían adónde remitir a las PWID para que recibieran formación o suministros. Para reducir la morbilidad y la mortalidad de las PWID, Harvey et al desarrollaron la herramienta educativa "Seis momentos de la prevención de infecciones en el uso de drogas inyectables "40(p.1). El conjunto de herramientas hace hincapié en un marco amplio centrado en la prevención de infecciones para las PWID.

Los participantes en este estudio manifestaron en repetidas ocasiones que estaban dispuestos a aprender y que querían estar seguros para evitar complicaciones. Solicitaron el desarrollo de vídeos y de una aplicación para teléfonos móviles (app) que mostrara desde celulitis leves hasta abscesos complejos. Existen riesgos asociados a esta última petición, ya que no se recomienda confiar únicamente en las imágenes de la herida como herramienta de diagnóstico de infecciones leves, progresivas y graves36.

Conclusión

En este estudio, los participantes adquirieron conocimientos sobre las SSTI y el desarrollo de abscesos. Aunque eran conscientes de los riesgos (mortalidad, morbilidad), seguían siendo reacios a acceder a la atención sanitaria oficial. Se necesita más investigación para comprender plenamente el mantenimiento y la ampliación de los servicios de cuidado de heridas, incluido el papel de los farmacéuticos en la comunidad. Además, la educación para las PWID era un mensaje coherente, y las PWID quieren materiales coherentes y creíbles de los que aprender. Por último, las PWID quieren saber que serán respetadas cuando accedan a los servicios sanitarios. Nuestra experiencia de las entrevistas nos dejó preguntándonos cómo describir mejor la humildad, inteligencia y amabilidad de los participantes. Eran reflexivos y querían mejorar su experiencia y la de los demás.

Agradecimientos

Agradecemos a los participantes que hayan compartido sus historias y sus atentas recomendaciones.

Conflicto de intereses

Los autores declaran no tener conflictos de intereses.

Financiación

Los autores no recibieron financiación por este estudio.

Author(s)

Janet L Kuhnke*

RN BA BScN MS NSWOC

Cape Breton University – Nursing

1250 Grand Lake Road, Sydney, Nova Scotia B1P 6L2, Canada

Email janet_kuhnke@cbu.ca

Sandra Jack-Malik

PhD (Education)

School of Education & Health, Cape Breton University

Sandi Maxwell

BA Soc(Honours)

Research Assistant, Cape Breton University

Janet Bickerton

RN BN MEd (Co-Investigator-CI)

Health Services Coordinator, The Ally Centre of Cape Breton, Sydney, Nova Scotia

Christine Porter

The Ally Centre of Cape Breton, Sydney, Nova Scotia

Nancy Kuta-George

RN

Wound Care Clinic, Victorian Order of Nurses, Membertou,

Cape Breton, Nova Scotia

* Corresponding author

References

- Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. Needle exchange programs (NEPs) FAQs 2019. Available from: https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/ccsa-010055-2004.pdf

- Hope VD, Parry JV, Ncube F, Hickman M. Not in the vein: ’missed hits’, subcutaneous and intramuscular injection and associated harms among people who inject psychoactive drugs in Bristol, United Kingdom. Int J Drug Policy 2016;28:83–90.

- Asher AK, Zhong Y, Garfein RS, Cuevas-Mota J, Teshale E. Association of self-reported abscess with high-risk injection-related behaviors among young persons who inject drugs. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2019;30:142–150.

- Sanchez DP, Tookes H, Pastar I, Lev-Tov H. Wounds and skin and soft tissue infections in people who inject drugs and the utility of syringe service programs in their management. Adv Wound Care 2021;10:571–582.

- Ramakrishnan K, Salinas RC, Higuita NIA. Skin and soft tissue infections. Am Fam Physician 2015;92:474–488.

- Sahu KK, Tsitsilianos N, Mishra AK, Suramaethakul N, Abraham G. Neck abscesses secondary to pocket shot intravenous drug abuse. BJM Case Report 2020;13:1–2.

- Pastorino A, Tavarez MM. Incision and drainage. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Dellinger EP, Goldstein EJC, Borbach SL, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Disease Society of America. IDSA Guideline 2014;59:e1-e52.

- Stanway A. Skin infections in IV drug users 2002. Available from: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/skin-infections-in-iv-drug-users/

- Lavender TW, McCarron B. Acute infections in IDU. Royal College Physicians 2013;13:511–513.

- Maloney S, Keenan E, Geoghegan N. What are the risk factors for soft tissue abscess development among injection drug users? Nursing Times 2010;106. Available from: https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/substance-misuse/what-are-the-risk-factors-for-soft-tissue-abscess-development-among-injecting-drug-users-14-06-2010/

- Khalil PN, Huber-Wagner S, Altheim D, Burklein D, Siebeck M, Hallfeldt K, et al. Diagnostic and treatment options for skin and soft abscesses in injecting drug users with consideration of the natural history and concomitant risk factors. Eur J Med Res 2008;13:415–424.

- Larney S, Peacock A, Mathers BM, Hickman M, Degenhardt L. A systematic review of injecting-related injury and disease among people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;171:39–49.

- Hrycko A, Mateu-Gelabert P, Ciervo C, Linn-Walton R, Eckhardt B. Severe bacterial infections in people who inject drugs: the role of injection-related tissue damage. Harm Reduct J 2022;19:1–13.

- Lloyd-Smith E, Kerr T, Hogg RS, Li K, Nontamer JSG, Wood E. Prevalence and correlates of abscesses among a cohort of injection drug users. Harm Reduct J 2005;2:1–4.

- Leung NS, Padgett P, Robinson DA, Brown EL. Prevalence and behavioural risk factors of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization in community-based injection drug users. Epidemiol Infect 2015;143:2430–2439.

- Luktke H. Abscess incision/drainage. Rush University Medical Center; 2016.

- Tsybina P, Kassir S, Clark M. Skinner S. Hospital admissions and mortality due to complications of injection drug use in two hospitals in Regina, Canada: retrospective chart review. Harm Reduct J 2021;18:44. doi:10.1186/s12954-021-00492-6

- Tarusuk J, Zhang J, Lemyre A, Cholete F, Bryson M, Paquette D. National findings from the Tracks survey of people who inject drugs in Canada, Phase 4, 2017–2019. Can Commun Dis Rep 2020;46:138–148.

- Phillips KT, Stein MD. Risk practices associated with bacterial infections among injection drug users in Denver, Colorado. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2010;36:92–97.

- Gilbert AR, Hellman JL, Wilkes MS, Rees VW, Summers PJ. Self-care habits among people who inject drugs with skin and soft tissue infections: a qualitative analysis. Harm Reduc J 2019;16:1–11.

- Fink DS, Lindsay SP, Slymen DJ, Kral AH, Bluthemthal RN. Abscess and self-treatment among IDU at four California syringe exchanges and their surrounding communities. Subst Use Misuse 2013;48:523–531.

- Johnson JL, Bottorff JL, Browne AJ, Grewal S, Hilton BA, Clarke H. Othering and being othered in the context of health care services. Health Comm 2004;16:255–271.

- Dechman MK, Bickerton J, Porter C. Paths leading into and out of injection drug use. Ally Centre of Cape Breton, Cape Breton University; 2017. Available from: https://www.allycentreofcapebreton.com/images/Files/PathsLeadingIntoAndOutOfInjectionDrugUse-October-2017.pdf

- Koivi S, Piggott T. Approaching the health and marginalization of people who use opioids. In: Arya AN, Piggott T, editors. Under-served: health determinants of Indigenous, inner-city, and migrant populations in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Scholars; 2018;153-165.

- Summers PJ, Struve IA, Wilkes MS, Rees VW. Injection-site vein loss and soft tissue abscesses associate with black tar heroin injections: a cross sectional study of two distinct populations in USA. Int J Drug Policy 2017;3:21–27.

- Nova Scotia Government Department of Health and Wellness. Nova Scotia’s opioid use and overdose framework; 2017. Available from: https://novascotia.ca/opioid/nova-scotia-opioid-use-and-overdose-framework.pdf

- Patton MQ. Evaluation flash cards: embedding evaluative thinking in organizational culture. Otto Bremer Trust; 2018.

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Continuum; 2011.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research a practical guide for beginners. London: SAGE Publishing; 2013.

- Creswell JW. A concise introduction to mixed methods research. London: SAGE Publishing; 2015.

- Liamputtong P. Researching the vulnerable. Sage; 2007.

- Treloar C, Rance J, Yates K, Mao L. Trust and people who inject drugs: the perspectives of clients and staff of needle syringe programs. Int J Drug Policy 2016;27:138–45.

- Bickerton J. Ally Centre outreach street health pilot: final report 2022. Available from: https://www.allycentreofcapebreton.com/images/Files/Final-report-Outreach-Street-Health.pdf

- Government of Nova Scotia. Coronavirus (COVID-19) latest guidance; 2022. Available from: https://novascotia.ca/coronavirus/

- Li S, Renick P, Senkowsky J, Nair A, Tang L. Diagnostics for wound infections. Adv Wound Care 2021;10:317–327.

- Peckham AM, Chan MG. Antimicrobial stewardship can help prevent inject drug use-related infections. Contagion 2020;6(2)

- 18-19. Available from: https://www.contagionlive.com/view/antimicrobial-stewardship-can-help-prevent-injection-drug-use-related-infections

- Marks LR, Liang SY, Muthulingam D, Schwarz ES, Liss DB, Munigala S, Warren DK, Durkin MJ. Evaluation of Partial Oral Antibiotic Treatment for Persons Who Inject Drugs and Are Hospitalized With Invasive Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Dec 17;71(10):e650-e656. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa365. PMID: 32239136; PMCID: PMC7745005.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Antimicrobial stewardship interventions: a practical guide; 2021. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/340709/9789289054980-eng.pdf

- Harvey L, Boudreau J, Sliwinski SK, Strymish J, Gifford AL, Hyde J, et al. Six moments of infection prevention in injection drug use: an educational toolkit for clinicians. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022;6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8794071/