Volume 41 Number 3

Complexity in care for an ostomate with surgical dehiscence after herniorrhaphy: a case study

Iraktânia Vitorino Diniz, Isabelle Pereira da Silva, Lorena Brito do O’, Isabelle Katherinne Fernandes Costa and Maria Júlia Guimarães Oliveira Soares

Keywords ostomy, nursing care, herniorrhaphy, postoperative complications, stomal therapist

For referencing Diniz IV et al. Complexity in care for an ostomate with surgical dehiscence after herniorrhaphy: a case study. WCET® Journal 2021;41(3):22-26

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.3.22-26

Submitted 13 December 2020

Accepted Accepted 18 July 2021

Abstract

Performing stoma surgery is often complex for the surgeon to undertake especially when the patient has pre-existing complications. Postoperatively, peristomal complications affect the adherence of the collection bag, and impair the self-care and wellbeing of the person with an ostomy, which increases the need for professionals trained in the management of peristomal skin complications. In addition, health professionals need to be able to educate the ostomate in self-care of the stoma or support them in managing peristomal complications. The aim of this case study is to report the management of a complex clinical case of a patient postoperatively following a herniorrhaphy and construction of a colostomy that resulted in surgical dehiscence and ensuing peristomal complications. The case study also highlights the clinical care advocated by the stomal therapist to manage these complications.

Introduction

About 100,000 surgical procedures to create stomas are performed each year in the United States of America (USA)1 and it is estimated that approximately 1 million people in the USA have an ostomy2. In Brazil, the data on ostomy surgery and stoma creation are uncertain; however, a high number of cases are estimated due to the annual increase in colorectal cancer, the main cause for surgery3.

Surgeons who perform ostomy surgery face challenges associated with modifying intestinal structures to create ileostomies or colostomies that alter intestinal transit times and thereby consistency of faecal output. Often there are associated complications in forming the stoma such as an obese abdomen4. Postoperatively, the primary problems reported are stoma and peristomal complications which can occur immediately or can be delayed complications; both reduce an ostomate’s quality of life5.

A study that analysed the incidence of complications after ostomy surgery found that 28.4% of participants developed some complication, and that the most common were superficial mucocutaneous separation (19.5%) and stoma retraction (3.2%)6. The syndrome of post-surgical complications in another study was 33.3%, of which 13.6% had retraction, 10.6% had parastomal hernia, and 28.8% had complications arising from the stoma – dermatitis (21.2%) and mucosal oedema (4.5%)7. Peristomal complications are the main complications that affect the collection bag’s adherence to the skin and impair the self-care and wellbeing of the ostomate since these can lead to leakage, irritant dermatitis, and other complications such as infection.

Thus, care both in the perioperative and postoperative rehabilitation processes are essential for the ostomate to adjust to living life with a stoma and achieve independence in self-care where possible. In this context, health professionals have an important role in the treatment of complications and in the health education process5.

The study complied with ethical standards in research, with approval of the project by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Paraíba, Brazil, under article 2,562,857. The participant signed the terms to consent to participate after clarifying the objectives and procedures of the case study.

The aim of this case study is to report the complex clinical case of a patient in the postoperative period following herniorrhaphy plus colostomy, and the management strategies of the stomal therapist.

Case Report

Presenting problem

The patient reported here was a female patient, aged 56 years old who was both obese and suffering from diabetes. In July 2018 she was admitted to the hospital complaining of severe abdominal pain with possible intestinal obstruction. On further examination, the laboratory tests and tomography showed a white blood cell count of 17,650, and a diagnosis of strangled inguinal hernia. She underwent an emergency exploratory laparotomy, herniorrhaphy, enterotomy and colostomy.

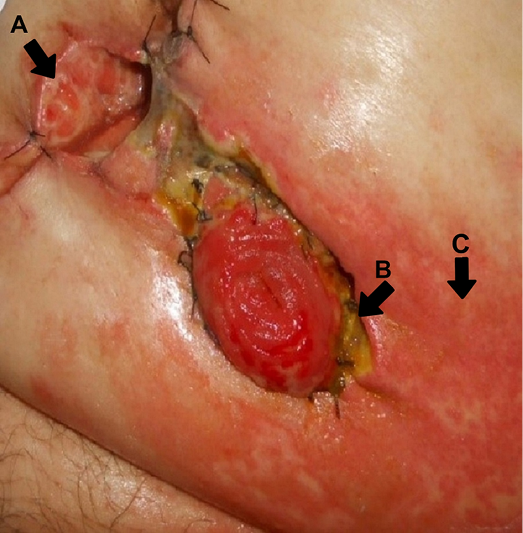

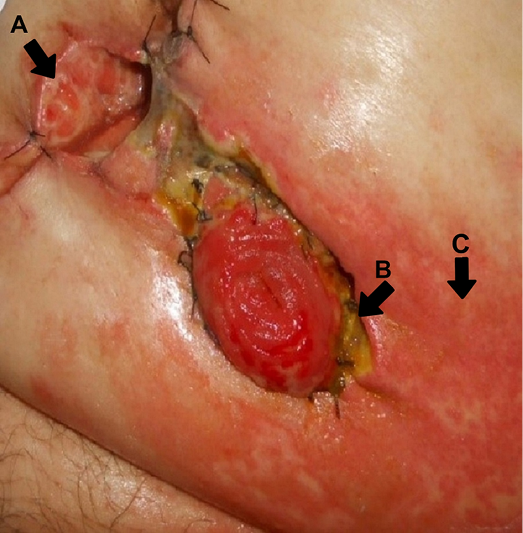

On 15 July 2018, Day 3 postoperatively, the patient developed purulent drainage from an opening in the middle of the surgical incision adjacent to the colostomy stoma. The abdomen was also distended, indicating the need to remove alternate sutures below the level of the umbilicus to alleviate the tension on the suture line adjacent to and to the right of the suture line. Suture removal subsequently led to the development of surgical dehiscence (Figure 1A). In addition, mucocutaneous detachment of the stoma from the abdomen occurred from the medial edge of the suture line and upper margins of the stoma (Figure 1B). Further, extensive peristomal dermatitis occurred which spread outward in a 10cm radius from the right side of the colostomy (Figure 1C). The peristomal dermatitis was caused by the semi-liquid stool from the colostomy coming into contact with intact skin due to poor adhesion of the ostomy appliance due to leakage of stool from around the stoma as a result of the combined effects of the surgical dehiscence and mucocutaneous separation.

Figure 1. A: surgical wound dehiscence; B: mucocutaneous detachment of the stoma; C: peristomal dermatitis

Stomal therapy and nursing interventions

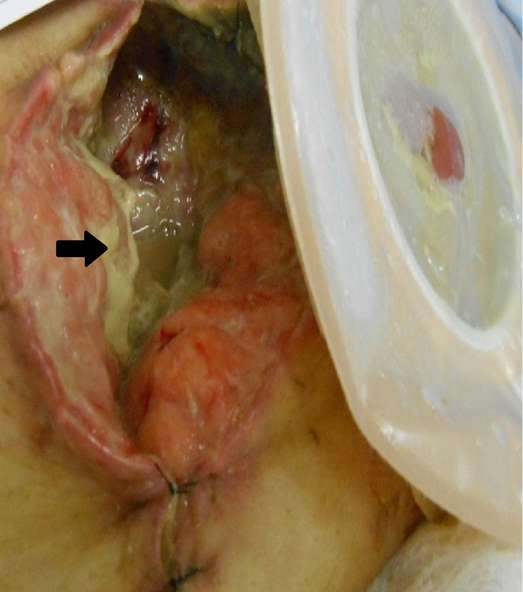

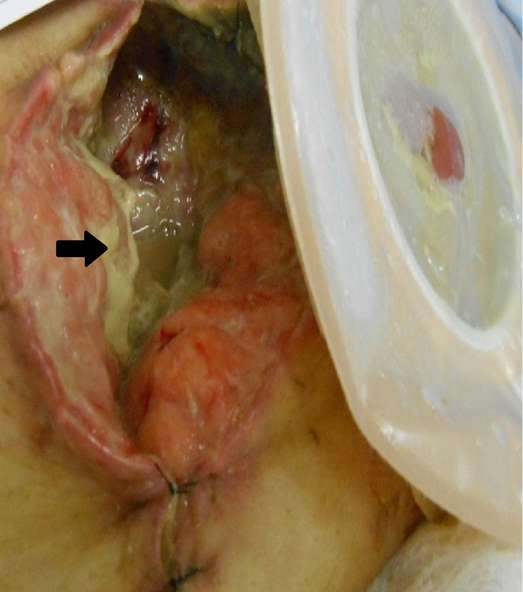

Wound, skin and stoma hygiene were performed with 0.9% saline solution. To manage and facilitate repair of the surgical wound dehiscence a calcium alginate was inserted into the wound bed. A protective piece of hydrocolloid sheet was placed over the calcium alginate and areas of dermatitis to provide a stable base upon which to apply the base plate (or flange) of a 2‑piece colostomy appliance. After 2 days, the dressing and colostomy appliance needed to be removed due to further wound dehiscence, wound necrosis and subsequent leakage (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Surgical dehiscence with presence of liquefactive necrosis and fibrin in the wound

On 17 July 2018, Day 5 postoperatively, the area of surgical dehiscence had expanded, measuring 8x7x5cm with the presence of infection and purulent exudate (Figure 2).This required a change in management strategy. In this case, the stomal therapist advocated the use of a hydropolymer dressing with silver (silver dressing) for antimicrobial control and absorption of exudate. The silver dressing was placed in the wound cavity. To ensure the stoma was isolated from the wound and to provide a good seal around the stoma to prevent leakage, stomahesive powder was applied to the areas of wet dermatitis proximal to the stoma. Stomahesive paste and hydrocolloid strips were used to fill in and cover wound beds created by the mucocutaneous separations and mould around the stoma to form a dry surface on which to place a convex base plate (2‑piece colostomy bag system) to further assist with stoma retraction; this would also encourage wound healing.

Due to the patient’s obesity and abdominal distension, it was difficult to secure adherence of the ostomy appliance, and on 20 July 2018, Day 7 postoperatively, the degree of incisional surgical dehiscence markedly increased, measuring 27x18x4cm. Within the wound cavity, not only was there obvious drainage of faecal fluid, there was opaque fibrinous tissue, with areas of liquefaction necrosis averaging 30% of the wound’s surface (Figure 2). To cope with physical changes to the abdominal wound and stoma, amendments to the dressing regimen were made as follows.

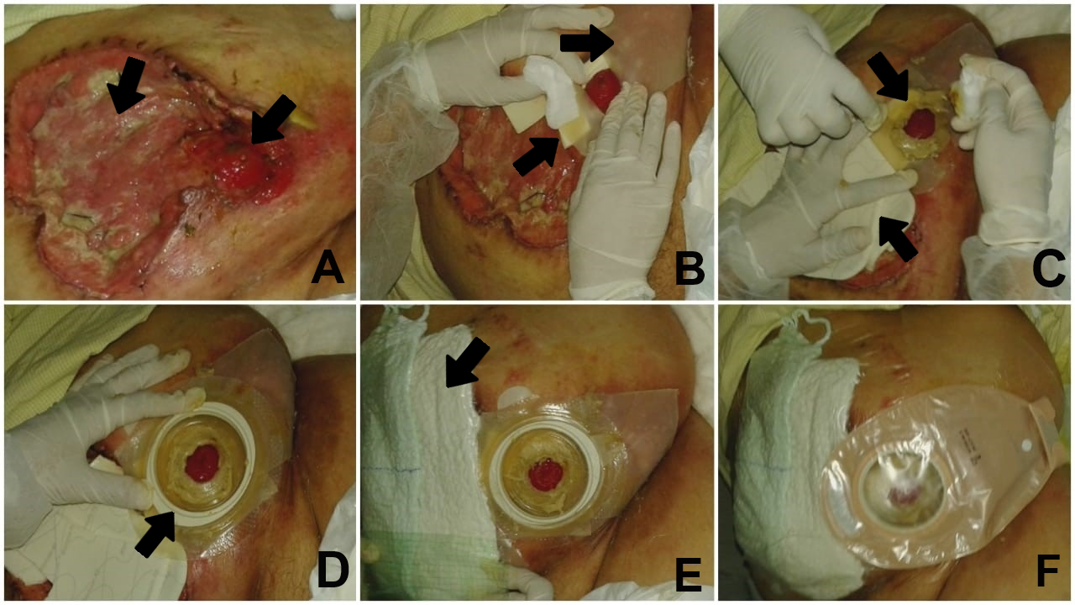

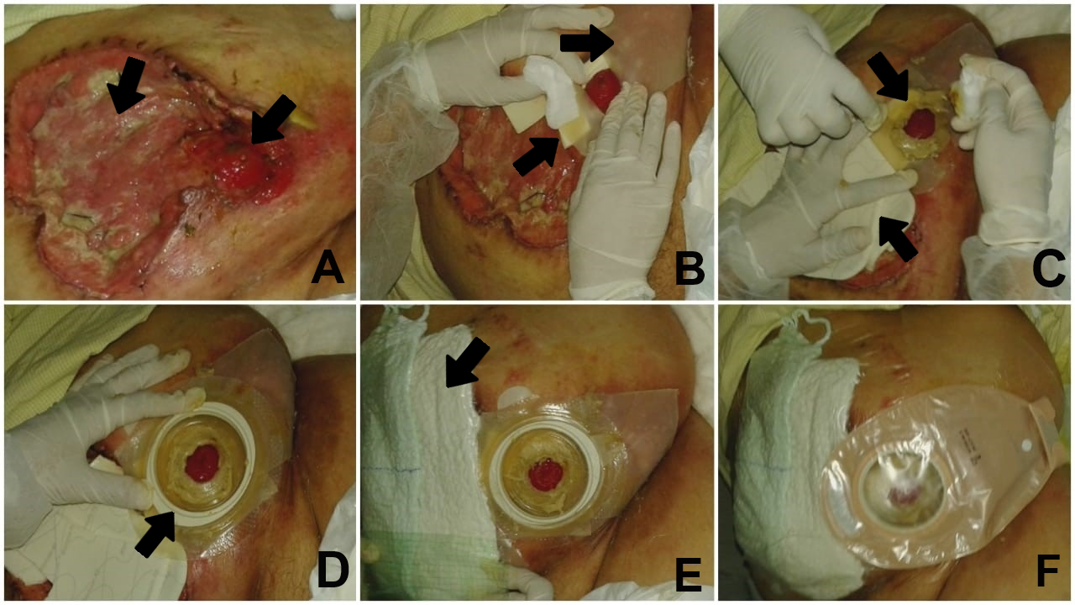

The wound was cleaned with 0.9% saline and 0.2% polyhexanide because, in the hospital in question, it is routine to use 0.9% saline solution and polyhexanide solution for cleaning. Saline solution was used to clean and remove excess dirt and the polyhexanide solution to clean a wound area due to its antiseptic properties. After cleaning, excess fluid was irrigated from the wound cavity using a number 8 nelaton catheter and 10cc syringe. To absorb wound exudate, the calcium alginate was placed as the primary dressing or contact layer in all areas of the surgical wound dehiscence wound bed, including all entrances to any sinus tracts/tunnels on view. The secondary dressing used for antimicrobial control was a hydropolymer with non-adhesive silver. Finally, a tertiary coverage of gauze combine was applied and externally fixaed with a polyurethane film (Figure 3 A–F).

Figure 3. A: ostomy within the cavity of surgical dehiscence; B: isolation of the ostomy using protective sheets and hydrocolloid strips; C: use of stomahesive paste around the stoma and calcium alginate in the wound cavity; D: application of the base plate; E: secondary dressing with silver foam and tertiary dressing with gauze combine and polyurethane film; F: completed dressing

The above wound dressing regimen was agreed upon by a multidisciplinary team including the responsible surgeon, the advising stomal therapist and nursing staff. The dressing was undertaken by the stomal therapist or nursing staff and nurse technicians. In addition to the wound care provided, it was necessary to continue to isolate the colostomy and peristomal skin complications present. Therefore, the colostomy was isolated by reconstructing the peristomal area with hydrocolloid strips and the ostomy paste. To further cover and protect the area of peristomal dermatitis from faecal fluid, a 20x20cm stomahesive sheet was used, in which an opening for the stoma was cut out and fixed around the stoma. A drainable transparent 2‑piece ostomy appliance with a convex base was applied over the protective sheet.

The patient was followed up for another 15 days. Although showing good evidence of wound healing and continued adherence of the wound dressings and ostomy appliance, the patient unfortunately died on 5 August 2018 due to her comorbid conditions and sepsis.

Discussion

In this case study, following emergency surgery the patient presented with suppuration from the suture line on Day 3 postoperatively. Post-removal of several abdominal sutures, the abdominal wound further dehisced along with simultaneous mucocutaneous separation of the stoma. These complications are deemed early surgical complications, all of which may occur due to tissue tension and comorbidities that impair healing, as well as due to infectious processes1.

Regarding emergency abdominal surgery, a higher prevalence of complications in the early postoperative period (36–66%), especially surgery involving construction of a stoma, are described. The expertise of the surgeon in creating a stoma is also a factor8. Surgical site infection, peristomal dermatitis and peristomal hernia are the main complications9–13.

It is also worth highlighting that diabetes and obesity as important factors related to mucocutaneous detachment and surgical dehiscence6. Obesity is a factor associated with difficult stoma construction and delayed postoperative recovery due to the challenges of resecting sufficient bowel to exteriorise the bowel through the abdominal wall to create a stoma. Obese individuals are more susceptible to wound dehiscence, surgical site infection and delayed wound healing due to raised intra-abdominal pressure, reduced perfusion of the tissues, and chronic inflammation of white adipose tissue that weakens tensile strength of the skin8,14,15. The association between diabetes and delayed wound healing are also well documented. All phases of wound healing are affected by diabetes, with prolonged inflammation thought to impede maturation of granulation tissue and the development of tensile strength within a wound arising from impaired blood vessels and resultant ischaemia1,16.

Post-surgery, peristomal skin conditions are the most common problem, varying from 10–70% of the cases17,18. Peristomal dermatitis can occur early or later in life around the skin of people with ostomies. This complication generates suffering, pain and difficulty in self-care, particularly where there is inadequate access to ostomy appliances and adjuvant skin care products19. The ostomy appliance and dressing remained intact without any leakage for 3 days (72 hours). This was a positive result and reduced secondary injury in continuously removing and replacing the dressing and ostomy appliance.

A comprehensive nursing assessment of patients in the peri and postoperative phases assists with identifying those patients at risk of compromised surgical recovery. This involves assessing the patient’s abdomen for shape, the integrity or stability of the surgical wound, the location and construction of the stoma, and the presence of scars that may minimise complications.

Assigning a nursing diagnosis facilitates implementation of nursing interventions specific to the individual patient and their care needs20. In cases where complications do occur, such as that described within our case study, prompt stomal therapy nursing interventions are necessary to manage the skin deficits that have occurred, with a variety of ostomy and skin accessory products available to the stomal therapist such as such as adhesive pastes and powder for ostomies, ostomy skin barriers and seals, as well as choosing an appropriate type of ostomy base plate and bag1. In addition, nurses need to understand the principles of caring for people with complex wounds and stomas and the importance of a multidisciplinary health team involvement; more nurses need to be skilled in this field of expertise21–23. There are also guidelines that address the importance of peristomal skin care, stoma care and appliance selection and how to prevent and manage early and late post-surgical ostomy complications. Adherence to advice within clinical practice guidelines on the aforementioned factors improves patient assessment, assists with early collaborative interventions and management of complications and, overall, improves patients’ quality of life and health service outcomes13,17,24.

Conclusion

The patient discussed here presented with postoperative complications of surgical dehiscence, mucocutaneous detachment of the stoma, and peristomal dermatitis following a herniorrhaphy and colostomy formation. These complications required the creative strategies of the stomal therapist to provide complex wound and ostomy care that involved the correct application and use of ostomy equipment and skin care accessories to minimise risk of wound contamination from faecal fluid, optimise the wound healing processes, and maintain patient comfort.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Complexité des soins prodigués à un stomisé présentant une déhiscence chirurgicale après une herniorrhaphie : une étude de cas

Iraktânia Vitorino Diniz, Isabelle Pereira da Silva, Lorena Brito do O’, Isabelle Katherinne Fernandes Costa and Maria Júlia Guimarães Oliveira Soares

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.41.3.22-26

Résumé

La réalisation d'une opération de stomie est souvent complexe pour le chirurgien, surtout lorsque le patient présente des complications préexistantes. En postopératoire, les complications péristomiales affectent l'adhérence de la poche de collecte et nuisent à l'autonomie et au bien-être de la personne stomisée, ce qui accroît le besoin de professionnels formés à la prise en charge des complications cutanées péristomiales. En outre, les professionnels de santé doivent être en mesure d'apprendre à la personne stomisée à prendre soin elle-même de sa stomie ou de l'aider à gérer les complications péristomiales. L'objectif de cette étude de cas est de rapporter la gestion du cas clinique complexe d'un patient en postopératoire après une herniorraphie et la construction d'une colostomie qui a entraîné une déhiscence chirurgicale puis des complications péristomiales. L'étude de cas met également en évidence les soins cliniques préconisés par le stomathérapeute pour prendre en charge ces complications.

Introduction

Environ 100 000 interventions chirurgicales visant à créer des stomies sont réalisées chaque année aux États-Unis d'Amérique (USA)1 et on estime qu'environ 1 million de personnes aux USA ont une stomie2. Au Brésil, les données relatives à la chirurgie et à la création de stomies sont incertaines; cependant, on estime qu'un nombre élevé de cas est dû à l'augmentation annuelle du cancer colorectal, principale cause d'intervention chirurgicale3.

Les chirurgiens qui pratiquent la chirurgie stomiale sont confrontés aux défis associés à la modification des structures intestinales pour créer des iléostomies ou des colostomies qui modifient les temps de transit intestinal et, par conséquent, la cohérence de l'évacuation des matières fécales. Il existe souvent des complications associées à la formation de la stomie, comme un abdomen obèse4. En postopératoire, les principaux problèmes signalés sont les complications stomiales et péristomiales, qui peuvent survenir immédiatement ou se présenter des complications différées; les deux réduisant la qualité de vie de la personne stomisée5.

Une étude qui a analysé l'incidence des complications après une chirurgie de stomie a révélé que 28,4% des participants ont développé une complication, et que les plus courantes étaient la séparation muco-cutanée superficielle (19,5%) et la rétraction de la stomie (3,2%)6. Dans une autre étude, le syndrome de complications post-chirurgicales était de 33,3%, dont 13,6% de rétraction, 10,6% de hernie parastomale et 28,8% de complications liées à la stomie - dermatite (21,2%) et œdème muqueux (4,5%)7. Les complications péristomiales sont les principales complications qui affectent l'adhérence cutanée de la poche de collecte et nuisent à l'autonomie et au bien-être de la personne stomisée, car elles peuvent entraîner des fuites, des dermatites d'irritation et d'autres complications telles que des infections.

Ainsi, les soins prodigués dans le cadre des processus de réadaptation périopératoire et postopératoire sont essentiels pour que la personne stomisée s'adapte à la vie avec une stomie et parvienne, dans la mesure du possible, à l'autonomie en matière de soins. Dans ce contexte, les professionnels de la santé ont un rôle important à jouer dans le traitement des complications et dans le processus d'éducation sanitaire5.

L'étude était conforme aux normes éthiques de la recherche, avec l'approbation du projet par le Research Ethics Committee de l'Université fédérale de Paraíba (Brésil), en vertu de l'article 2 562 857. Le participant a signé les termes de son consentement à participer après clarification des objectifs et des procédures de l'étude de cas.

L'objectif de cette étude de cas est de rapporter le cas clinique complexe d'un patient en période postopératoire après une herniorrhaphie plus colostomie, et les stratégies de prise en charge du stomathérapeute.

Compte-rendu de cas

Présentation du problème

Le patient dont il est question ici était une femme âgée de 56 ans, à la fois obèse et souffrant de diabète. En juillet 2018, elle a été admise à l'hôpital en se plaignant de douleurs abdominales sévères avec une possible occlusion intestinale. Lors d'un examen plus approfondi, les tests de laboratoire et la tomographie ont révélé un taux de globules blancs de 17 650, et un diagnostic de hernie inguinale étranglée. Elle a subi en urgence une laparotomie exploratoire, une herniorrhaphie, une entérotomie et une colostomie.

Le 15 juillet 2018, jour postopératoire 3, la patiente a développé un drainage purulent à partir d'une ouverture au milieu de l'incision chirurgicale adjacente à la stomie de colostomie. L'abdomen était également distendu, ce qui indiquait la nécessité de retirer les sutures alternées en-dessous du niveau de l'ombilic pour alléger la tension sur la ligne de suture adjacente et à droite de la ligne de suture. Le retrait des sutures a ensuite conduit au développement d'une déhiscence chirurgicale (Figure 1A). En outre, un détachement muco-cutané de la stomie et de l'abdomen s'est produit à partir du berge médiale de la ligne de suture et des bords supérieurs de la stomie (Figure 1B). En outre, une dermatite péristomiale étendue est apparue, qui s'est étendue vers l'extérieur dans un rayon de 10 cm à partir du côté droit de la colostomie (Figure 1C). La dermatite péristomiale a été causée par les selles semi-liquides de la colostomie entrant en contact avec la peau intacte en raison de la mauvaise adhérence de l'appareillage de stomie due à une fuite de selles autour de la stomie résultant des effets combinés de la déhiscence chirurgicale et de la séparation muco-cutanée.

Figure 1. A : déhiscence de la plaie chirurgicale ; B : décollement muco-cutané de la stomie ; C : dermatite péristomiale

Traitement de la stomie et interventions infirmières

L'hygiène de la plaie, de la peau et de la stomie a été réalisée avec une solution saline à 0,9%. Pour gérer et faciliter la réparation de la déhiscence de la plaie chirurgicale, un alginate de calcium a été inséré dans le lit de la plaie. Un morceau de feuille hydrocolloïde a été placé sur l'alginate de calcium et les zones de dermatite pour fournir une base stable sur laquelle appliquer la plaque support (ou bride) d'un appareillage de colostomie en deux parties. Après 2 jours, le pansement et l'appareillage de colostomie ont dû être retirés en raison d'une déhiscence supplémentaire de la plaie, d'une nécrose de la plaie et d'une fuite subséquente (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Déhiscence chirurgicale avec présence de nécrose liquéfactive et de fibrine dans la plaie

Le 17 juillet 2018, jour postopératoire 5, la zone de déhiscence chirurgicale s'était étendue, mesurant 8x7x5cm avec la présence d'une infection et d'un exsudat purulent (Figure 2).Cela a nécessité un changement de stratégie de prise en charge. Dans ce cas, le stomathérapeute a préconisé l'utilisation d'un pansement hydropolymère à l'argent (pansement à l'argent) pour le contrôle antimicrobien et l'absorption de l'exsudat. Le pansement à l’ argent a été placé dans la cavité de la plaie. Pour s'assurer que la stomie était isolée de la plaie et pour assurer une bonne étanchéité autour de la stomie afin d'éviter les fuites, une poudre adhésive pour stomie a été appliquée sur les zones de dermatite humide proximales à la stomie. Une pâte adhésive pour stomie et des bandes hydrocolloïdes ont été utilisées pour remplir et couvrir le lit des plaies créées par les séparations muco-cutanées de façon à obtenir un moulage autour de la stomie afin de former une surface sèche sur laquelle placer une plaque support convexe (système de poche de colostomie en deux parties) pour aider davantage à la rétraction de la stomie; ceci favoriserait également la cicatrisation.

En raison de l'obésité et de la distension abdominale de la patiente, il était difficile d'assurer l'adhérence de l'appareillage de stomie, et le 20 juillet 2018, jour postopératoire 7, le degré de déhiscence chirurgicale incisionnelle a nettement augmenté, mesurant 27x18x4cm. La cavité de la plaie, présentait non seulement un drainage évident du liquide fécal, mais aussi un tissu fibrineux opaque, avec des zones de nécrose de liquéfaction représentant en moyenne 30% de la surface de la plaie (Figure 2). Pour faire face aux changements physiques de la plaie abdominale et de la stomie, des modifications ont été apportées au régime de pansement comme suit.

La plaie a été nettoyée avec du sérum physiologique à 0,9% et du polyhexanide à 0,2% car, dans l'hôpital en question, il est courant d'utiliser une solution saline à 0,9% et une solution de polyhexanide pour le nettoyage. La solution saline était utilisée pour nettoyer et enlever l'excès de saleté et la solution de polyhexanide pour nettoyer la zone d'une plaie en raison de ses propriétés antiseptiques. Après le nettoyage, l'excès de liquide a été drainé de la cavité de la plaie à l'aide d'un cathéter Nelaton numéro 8 et d'une seringue de 10cc. Pour absorber l'exsudat de la plaie, l'alginate de calcium a été placé comme pansement primaire ou comme couche de contact dans toutes les zones du lit de la plaie chirurgicale de déhiscence, y compris toutes les entrées de tous les canaux sinusaux visibles. Le pansement secondaire utilisé pour le contrôle antimicrobien était un hydropolymère à l'argent non adhésif. Enfin, une couverture tertiaire de gaze combinée a été appliquée et fixée à l'extérieur avec un film de polyuréthane (Figure 3 A-F).

Figure 3. A : stomie à l'intérieur de la cavité de déhiscence chirurgicale ; B : isolement de la stomie à l'aide de feuilles de protection et de bandes hydrocolloïdes ; C : utilisation de pâte adhésive autour de la stomie et d'alginate de calcium dans la cavité de la plaie ; D : application de la plaque support ; E : pansement secondaire avec une compresse à l’argent et pansement tertiaire avec de la gaze combinée et un film de polyuréthane ; F : pansement achevé

Le régime de pansement ci-dessus a été agréé par une équipe multidisciplinaire comprenant le chirurgien responsable, le stomathérapeute conseiller et le personnel infirmier. Le pansement était effectué par le stomathérapeute ou le personnel infirmier et les infirmières et les infirmiers techniciens. En plus des soins de la plaie, il était nécessaire de continuer à isoler la colostomie des complications cutanées péristomiales présentes. En conséquence, la colostomie a été isolée en reconstruisant la zone péristomiale à l’aide de bandes hydrocolloïdes et de pâte de stomie. Pour couvrir et protéger davantage la zone de dermatite péristomiale des fluides fécaux, une feuille adhésive pour stomie de 20x20cm a été utilisée, dans laquelle une ouverture pour la stomie a été découpée et fixée autour de la stomie. Un appareillage de stomie transparent drainable en 2 parties doté d’une base convexe a été appliqué sur la feuille de protection.

Le patient a été suivi pendant 15 jours supplémentaires. Bien que présentant de bons signes de cicatrisation de la plaie et une adhérence continue des pansements et de l'appareillage de stomie, la patiente est malheureusement décédée le 5 août 2018 en raison de ses comorbidités et d'une septicémie.

Discussion

Dans cette étude de cas, après une opération chirurgicale en urgence, la patiente a présenté une suppuration de la ligne de suture au jour postopératoire 3. Après le retrait de plusieurs sutures abdominales, la plaie abdominale est devenue déhiscente avec une séparation muco-cutanée de la stomie simultanée. Ces complications sont considérées comme des complications chirurgicales précoces, qui peuvent toutes survenir en raison de la tension tissulaire et des comorbidités qui entravent la cicatrisation, ainsi qu'en raison de processus infectieux1.

En ce qui concerne la chirurgie abdominale d'urgence, une prévalence plus élevée de complications dans la période postopératoire précoce (36-66%), en particulier la chirurgie impliquant la construction d'une stomie, sont décrites. L'expertise du chirurgien dans la création d'une stomie est également un facteur8. L'infection du site chirurgical, la dermatite péristomiale et la hernie péristomiale sont les principales complications9-13.

Il convient également de souligner que le diabète et l'obésité sont des facteurs importants liés au décollement muco-cutané et à la déhiscence chirurgicale6. L'obésité est un facteur associé à une construction difficile de la stomie et à une récupération postopératoire retardée en raison des difficultés à réséquer suffisamment d'intestin pour l'extérioriser à travers la paroi abdominale afin de créer une stomie. Les personnes obèses sont plus susceptibles de subir une déhiscence de la plaie, une infection du site chirurgical et un retard de cicatrisation en raison d'une pression intra-abdominale élevée, d'une vascularisation réduite des tissus et d'une inflammation chronique du tissu adipeux blanc qui affaiblit la résistance à la traction de la peau8,14,15. L'association entre le diabète et le retard de cicatrisation est également bien documentée. Toutes les phases de la cicatrisation des plaies sont affectées par le diabète : on pense qu'une inflammation prolongée entrave la maturation du tissu de granulation et que le développement de la résistance à la traction dans une plaie résulte de l'altération des vaisseaux sanguins et de l'ischémie qui en résulte1,16.

Après une intervention chirurgicale, les affections cutanées péristomiales constituent le problème le plus courant, variant de 10 à 70% des cas17,18. La dermatite péristomiale peut survenir tôt ou tard sur la peau des personnes ayant une stomie. Cette complication génère de la souffrance, de la douleur et des difficultés dans l’autonomie des soins en particulier lorsque l'accès aux appareillages pour stomie et aux produits de soins cutanés adjuvants est insuffisant19. L'appareillage de stomie et le pansement sont restés intacts sans aucune fuite pendant 3 jours (72 heures). Il s'agit d'un résultat positif qui a permis de réduire les blessures secondaires liées au retrait et au remplacement continus du pansement et de l'appareillage de stomie.

Une évaluation infirmière complète des patients dans les phases péri et postopératoires permet d'identifier les patients à risque de rétablissement chirurgical compromis. Cela implique d'évaluer la forme de l'abdomen du patient, l'intégrité ou la stabilité de la plaie chirurgicale, l'emplacement et la construction de la stomie, ainsi que la présence de cicatrices susceptibles de minimiser les complications.

L'affectation d'un diagnostic infirmier facilite la mise en œuvre d'interventions infirmières spécifiques à chaque patient et à ses besoins en matière de soins20. Dans les cas où des complications surviennent, comme celle décrite dans notre étude de cas, des interventions infirmières de stomathérapie rapides sont nécessaires pour prendre en charge les déficits cutanés qui se sont produits, en utilisant la variété de produits et d'accessoires de stomie et cutanés à la disposition du stomathérapeute, tels que pâtes et poudres adhésives pour stomies, barrières cutanées et joints de stomie, ainsi qu’en choisissant un type approprié de plaque support et de poche de stomie1. En outre, les infirmières et infirmiers doivent comprendre les principes de la prise en charge des personnes souffrant de plaies et de stomies complexes et l'importance de l'implication d'une équipe soignante multidisciplinaire; davantage d'infirmières et infirmiers doivent être qualifiés dans ce domaine d'expertise21-23. Il existe également des directives qui traitent de l'importance des soins cutanés péristomiaux, des soins de la stomie et du choix de l'appareillage, ainsi que de la manière de prévenir et de prendre en charge les complications de stomie post-chirurgicales précoces et tardives. Le respect des recomandations fournies dans les directives de pratique clinique sur les facteurs susmentionnés améliore l'évaluation des patients, facilite les interventions collaboratives précoces et la prise en charge des complications et, globalement, améliore la qualité de vie des patients et les résultats des services de santé13,17,24.

Conclusion

La patiente dont il est question ici présentait des complications postopératoires de déhiscence chirurgicale, de décollement muco-cutané de la stomie et de dermatite péristomiale suite à une herniorraphie et à la formation d'une colostomie. Ces complications ont nécessité des stratégies créatives de la part du soignant stomathérapeute pour fournir des soins complexes de la plaie et de la stomie, impliquant le choix et l'utilisation correctes de l'équipement de stomie et des accessoires de soins cutanés, afin de minimiser le risque de contamination de la plaie par les fluidess fécaux, d'optimiser les processus de cicatrisation et de préserver le confort du patient.

Conflit d'intérêt

Les auteurs ne déclarent aucun conflit d'intérêt.

Financement

Les auteurs n'ont reçu aucun financement pour cette étude.

Author(s)

Iraktânia Vitorino Diniz*

Doctoral student, Federal University of Paraíba, Postgraduate Nursing, PPGEN, João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brazil

Golfo da Califórnia Street, 90, Cabedelo, Paraíba, Brazil

Email iraktania@hotmail.com

Isabelle Pereira da Silva

Master’s student, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Department of Nursing, Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil

Email isabelle_dasilva@hotmail.com

Lorena Brito do O’

Nursing student, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Department of Nursing, Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil

Email lorena_ito@hotmail.com

Isabelle Katherinne Fernandes Costa PhD

Teacher, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Department of Nursing, Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil

Email isabellekfc@yahoo.com.br

Maria Júlia Guimarães Oliveira Soares PhD

Teacher, Federal University of Paraíba, Postgraduate Nursing, PPGEN, João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brazil

Email mmjulieg@gmail.com

* Corresponding author

References

- Murken DR, Bleier JIS. Ostomy-related complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2019;32(3):176–182.

- United Ostomy Associations of America (UOAA). New ostomy patient guide. United States: The Phoenix/UOAA; 2020. Available from: https://www.ostomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/UOAA-New-Ostomy-Patient-Guide-2020-10.pdf

- National Cancer Institute (INCA). Types of cancer: bowel cancer. Ministry of Health; 2020. Available from: https://www.inca.gov.br/sites/ufu.sti.inca.local/files//media/document//cancer-in-brazil-vol4-2013.pdf

- Mota MS, Gomes GC, Petuco VM. Repercussions in the living process of people with stomas. Text Contexto Enferm 2016;25(1):e1260014.

- Maydick-Youngberg D. A descriptive study to explore the effect of peristomal skin complications on quality of life of adults with a permanent ostomy. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(5):10–23.

- Koc U, Karaman K, Gomceli I, Dalgic T, Ozer I, Ulas M, et al. A retrospective analysis of factors affecting early stoma complications. Ostomy Wound Manage 2017;63(1):28–32.

- Gálvez ACM, Sánchez FJ, Moreno CA, Fernández AJP, García RB, López MC, et al. Value-based healthcare in ostomies. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(16):5879.

- Moody D, Wallace A. Stories from the bedside: the challenges of nursing the obese patient with a stoma. WCET J 2013;33(4):26–30.

- Engida A, Ayelign T, Mahteme B, Aida T, Abreham B. Types and indications of colostomy and determinants of outcomes of patients after surgery. Ethiop J Health Sci 2016;26(2):117–20.

- Spiers J, Smith JA, Simpson P, Nicholls AR. The treatment experiences of people living with ileostomies: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. J Adv Nurs 2016 Nov;72(11):2662–2671.

- Ribeiro MSM, Ferreira MCM, Coelho SA, Mendonça GS. Clinical and demographic characteristics of intestinal stoma patients assisted by orthotics and prosthesis grant program of the Clinical Hospital of the Federal University of Uberlandia, Brazil. J Biosci 2016;32(4):1103–9.

- Aahlin EK, Tranø G, Johns N, Horn A, Søreide JA, Fearon KC, et al. Risk factors, complications and survival after upper abdominal surgery: a prospective cohort study. BMC Surg 2015;15(1):83.

- Chabal LO, Prentice JL, Ayello EA. WCET® International Ostomy Guideline. Perth, Australia: WCET®; 2020.

- Williamson K. Nursing people with bariatric care needs: more questions than answers. Wounds UK 2020;16(1):64–71.

- Colwell JC, Fichera A. Care of the obese patient with an ostomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2005;32(6):378–383.

- Patel S, Srivastava S, Singh MR, Singh D. Mechanistic insight into diabetic wounds: pathogenesis, molecular targets and treatment strategies to pace wound healing. Biomed Pharmacother 2019;112:108615.

- Domansky RC, Borges EL. Manual for the prevention of skin injuries: evidence-based recommendations. 2nd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Rubio; 2014.

- Stelton S. CE: Stoma and peristomal skin care: a clinical review. Am J Nurs 2019 Jun;119(6):38–45.

- Costa JM, Ramos RS, Santos MM, Silva DF, Gomes TF, Batista RQ. Intestinal stoma complications in patients in the postoperative period of rectal tumor resection. Current Nurs Mag 2017; special ed: 35–42.

- Santana RF, Passarelles DMA, Rembold SM, Souza PA, Lopes MVO, Melo UG. Nursing diagnosis risk of delayed surgical recovery: content validation. Rev Eletr Nurse 2018;20:v20a34.

- Beard PD, Bittencourt VLL, Kolankiewicz ACB, Loro MM. Care demands of ostomized cancer patients assisted in primary health care. Rev Enferm UFPE 2017;11(8):3122–9.

- Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, & Guideline Development Task Force. WOCN Society clinical guideline: management of the adult patient with a fecal or urinary ostomy: an executive summary. J WOCN 2018;45(1):50–58.

- Pinto IES, Queirós SMM, Queirós CDR, Silva CRR, Santos CSVB, Brito MAC. Risk factors associated with the development of complications of the elimination stoma and the peristomal skin. Rev Enf 2017;4(15):155–166.

- Marques GS, Nascimento DC, Rodrigues FR, Lima CMF, Jesus DF. The experience of people with intestinal ostomy in the support group at a university hospital. Rev Hosp Univ Pedro Ernesto 2016;15(2):113–21.