Volume 29 Number 3

Partnering with patients and the public as co-researchers in wounds research

Georgia A Tobiano, Jill L Campbell, Megan E Rattray and Wendy P Chaboyer

Keywords patient participation, consumer advocacy, patient and public engagement, stakeholder participation, wounds and injuries

For referencing Tobiano GA et al. Partnering with patients and the public as co-researchers in wounds research. Wound Practice and Research 2021; 29(3):158-162.

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wpr.29.3. 158-162

Submitted 4 June 2021

Accepted 14 July 2021

Abstract

Patient and public engagement (PPE) in research is increasingly being mandated by research funding bodies and policy makers. PPE is an approach where research is conducted with or by patients or the public, making them part of the research team. In this review article we summarise benefits of PPE, the state of patient engagement in wound care, current gaps in PPE in wounds research, and challenges surrounding PPE partnerships. Finally, we provide an example of how to prepare for a research project with PPE. In this example we demonstrate how frameworks can guide development of strategies to build good partnerships with patient and/or members of the public as co-researchers.

Introduction

Over the last 10 years, involving patients and the public in research has become universally recognised as best practice by policy makers, funding bodies, healthcare professionals and, most importantly, public organisations and patients1–4. In Australia, patient and public engagement (PPE), also known as consumer and community involvement (CCI), is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and the Consumers Health Forum of Australia4–6. Further, international journals such as the BMJ have introduced mandatory criteria at manuscript submission for reporting if and how PPE was utilised in the study7. PPE in research is defined as research being carried out “with” or “by” patients and members or the public rather than “to”, “about” or “for” them4. It can and should span the lifecycle of the research project, from planning the research to dissemination4.

Benefits of PPE

It is accepted that patients and the public enhance the quality of research, and they have a right and responsibility to do so3,4. Specific benefits of PPE for the public include research that is relevant to patient problems, community needs and priorities, increased public awareness and support for research, and discovery of new knowledge that leads to improved patient care2,3,8,9. Further, the public’s confidence in research is improved through transparency and accountability in the conduct of the research and the use of public research money4. Researchers benefit because their work has increased community relevance beyond academia given the research is grounded in the public’s perspectives and lived experiences2,3,8,9.

Patient engagement in wound care

Early and instrumental PPE frameworks identify opportunities for patient engagement on a continuum, ranging from participation in direct care through to policy making10. The peak body for wound prevention and management in Australia (i.e. Wounds Australia) supports PPE in direct care with the inclusion of a collaborative practice standard in the Standards for wound prevention and management publication11. As a result, there is increasing recognition by clinicians that patients should be included as vital members of their wound management teams12. The development of the International pressure injury clinical guideline is an example of PPE in policy development. This guideline was informed by an international survey of over 1,200 patients and carers to identify patient priorities, needs, goals and education with regard to pressure injury prevention and treatment13.

PPE has now transformed, with patients and the public participating as co-researchers. A recent Australian study exemplifies PPE in wound care research14. The researchers aimed to develop, trial and evaluate a Champions for Skin Integrity program to improve evidence-based wound care, reduce the prevalence of wounds, and improve skin integrity in aged care facilities14. Residents and families were involved in the research process by: i) participating in focus groups that identified current practices and beliefs, skin and wound care preferences and preferred information sharing methods; and ii) providing feedback to researchers throughout development and implementation of the program14. This approach increased the implementation of evidence-based wound care prevention and treatment strategies and significantly reduced the number of residents who developed a wound (53% to 43%), demonstrating the direct benefits of PPE to skin integrity and wound care outcomes14. Considering funding and resources for wound care research is limited and competitive, adopting PPE is essential to develop relevant and competitive research programs that have the potential to meet patient and public needs, priorities and expectations.

Gaps in PPE in wound care research

Despite recognition of the need for PPE in research, a gap remains in implementation and reporting. Muir and colleagues15 published a scoping review aimed to identify patient involvement in surgical wound care research and the quality of reporting of that research. They uncovered three themes in the data. The first theme was “patient involvement in modifying and refining research processes”. It was described as patient involvement in specific elements of the research such as developing and refining patient information leaflets, questionnaires, interview guides, protocols and manuscripts15. The second theme was “connecting and balancing expert and patient views”. In this theme the tensions between patients and researchers were described, which led to conflict with the possibility of impeding the research. The final theme was “sharing personal insight”, where patients were valued as an expert source of information due to their unique perspective15. The authors concluded that PPE involvement in surgical wound care research was limited and was not reflected throughout the whole research process, the patients and public involved lacked diversity, and there was suboptimal reporting of PPE15. The opportunities and gaps reported by this team15 can be used as guideposts to support the way forward for researchers, funders and key stakeholders in improving PPE involvement in wound care research. To our knowledge, no review has been conducted on PPE in chronic wound research, an important next step for researchers.

Challenges for PPE

Embedding meaningful PPE in wound care research is challenging. A true partnership or collaboration is central to the success of PPE in research2. However, this can be difficult to achieve. Breakdowns in the partnership between the patient or public and researcher are common6. Reasons for these breakdowns can be attributed to power imbalances between patients, the public and researchers, a lack of clarity in the roles and expectations leading to conflict, insufficient time spent building relationships, and tokenism that can occur when patients and the public are engaged superficially and/or the researchers see the relationship as ‘ticking a box’ rather than something more meaningful6,8. These partnership issues are compounded by the significant financial and human resources required for authentic PPE16. PPE takes time and training to ensure the patient/public and the researcher is ready for the complex relationship ahead17. Further, efforts are needed to find the right patient/member of the public for the project, ensuring diverse representation and engaging with hard-to-reach patients. Thus, it is unsurprising that PPE is not yet well-embedded in wound research.

How to build partnerships for PPE in research

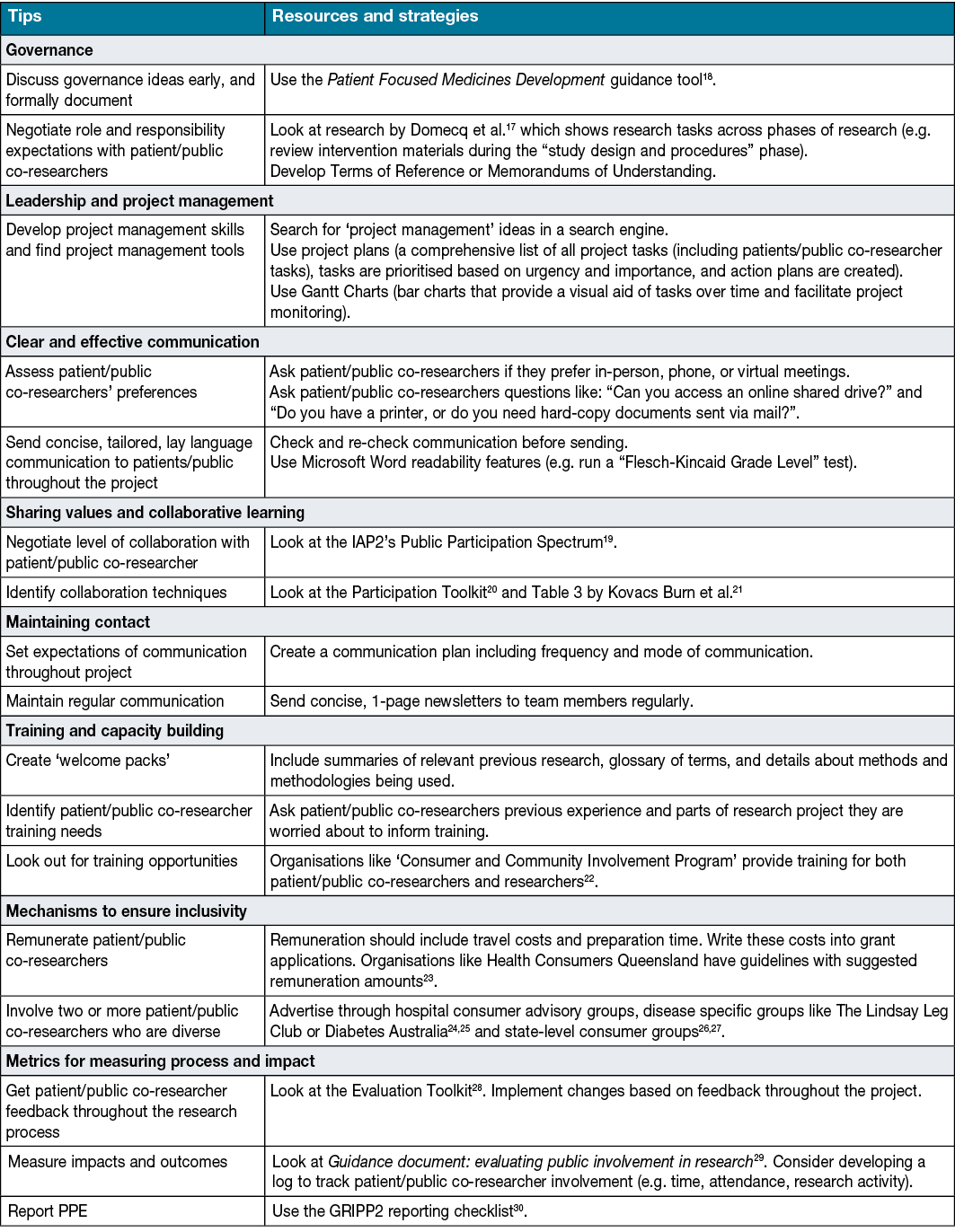

Many frameworks have been developed to provide researchers with guidance on how to build genuine partnerships with patients and the public during PPE in research. A recent systematic review identified 65 theoretically diverse frameworks for guiding, evaluating and reporting PPE in research2. Of these, 17 frameworks have been developed to guide partnerships between patients, the public and researchers2. Common partnership principles across these frameworks include governance, leadership and project management, clear and effective communication, sharing values and collaborative learning, maintaining contact, training and capacity building, mechanisms to ensure inclusivity and metrics for measuring process and impact (see Table 1)2.

Table 1. Examples of tips to promote partnerships during PPE research

However, we have found that concrete strategies to apply these principles to PPE research are unclear. Researchers have suggested customising these frameworks to your specific context to guide PPE research to address this deficit2. A useful approach our team has trialled is to use partnership frameworks prior to starting your study to brainstorm strategies for PPE. We suggest using a table such as Table 1 to list all the principles in the partnership framework. Next, identify other research and resources to develop strategies to promote good partnership.

Conclusion

PPE is both essential and beneficial for high quality and impactful research, but there can be challenges enacting PPE. Given the time and resource implications of PPE, it is important to undertake planning early in the research project to ensure there is a good partnership between the patients or members of the public and the research team. There are many frameworks available to guide this planning; using a pre-agreed framework to brainstorm PPE strategies may be a useful way to address PPE challenges and ensure meaningful partnerships with patients and the public.

In wound care, patients are being recognised as rightful partners in their care, which we now see being extended to partnerships in research. Opportunities exist for researchers to increase and strengthen PPE in this emerging field. First, we identified that a review of PPE in chronic wounds research is required. Second, we suggest that future researchers include descriptions of ‘how’ they engaged patients/public in their wound research. Finally, if using frameworks to guide PPE, we recommend publishing these experiences to build rigour around this approach. Through documenting and sharing these experiences, support for PPE in wound care research will grow and evidence-based strategies to enact it will continue to emerge.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author(s)

Georgia A Tobiano* PhD

National Health and Medical Research Council Centre of Research Excellence in Wiser Wound Care, Menzies Health Institute, Griffith University

and Gold Coast University Hospital, Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service, Gold Coast Campus Building G01 Room 2.05A, Parklands Drive

Parklands, QLD 4222 Australia

Email g.tobiano@griffith.edu.au

Jill L Campbell1 PhD

Megan E Rattray PhD

Griffith University, QLD 4222 Australia

Wendy P Chaboyer1 PhD

1National Health and Medical Research Council Centre of Research Excellence in Wiser Wound Care, Menzies Health Institute, Griffith University

QLD 4222 Australia

* Corresponding author

References

- Gibson A, Britten N, Lynch J. Theoretical directions for an emancipatory concept of patient and public involvement. Health 2012;16:531–47.

- Greenhalgh T, Hinton L, Finlay T, et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co-design pilot. Health Expect 2019;22:785–801.

- Manafo E, Petermann L, Mason-Lai P, Vandall-Walker V. Patient engagement in Canada: a scoping review of the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of patient engagement in health research. Health Res Policy Syst 2018;16:e1-e11.

- NHMRC. Statement on consumer and community involvement in health and medical research. Report. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: NHMRC, 2016. Report No. 1.

- Consumers Health Forum of Australia. Putting consumers in control of their own health and care [Internet]. Deakin, Australian Capital Territory: Consumers Health Forum of Australia; ND [cited 2021 June 4]. Available from: https://chf.org.au/.

- Bélisle-Pipon J-C, Rouleau G, Birko S. Early-career researchers’ views on ethical dimensions of patient engagement in research. BMC Med Ethics 2018;19:e1–e10.

- BMJ. Resources for authors [Internet]. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd: London, England; 2021 [cited 2021 June 1]. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-authors.

- Anderst A, Conroy K, Fairbrother G, Hallam L, McPhail A, Taylor V. Engaging consumers in health research: a narrative review. Aust Health Rev 2020;44:806–13.

- Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect 2014;17:637–50.

- Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff 2013;32:223–31.

- Wounds Australia. Standards for wound prevention and management. Standards. Osborne Park, Western Australia: Cambridge Media 2018. Report No. 3.

- Lindsay E, Renyi R, Wilkie P, et al. Patient-centred care: a call to action for wound management. J Wound Care 2017;26:662–77.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: clinical practice guideline: the international guideline. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury, Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance 2019. Report No. 3.

- Edwards HE, Chang AM, Gibb M, et al. Reduced prevalence and severity of wounds following implementation of the Champions for Skin Integrity model to facilitate uptake of evidence-based practice in aged care. J Clin Nurs 2017;26:4276–85.

- Muir R, Carlini JJ, Harbeck EL, et al. Patient involvement in surgical wound care research: a scoping review. Int Wound J 2020;17:1462–82.

- Adhikari B, Pell C, Cheah PY. Community engagement and ethical global health research. Global Bioethic 2020;31:1–12.

- Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:e1–e9.

- Patient Focused Medicines Development. The patient engagement quality guidance [Internet]. Brussels, Belgium: Patient Focused Medicines Development; 2021 [cited 2021 May 28]. Available from: https://patientfocusedmedicine.org/the-patient-engagement-quality-guidance-download/.

- International Association for Public Participation. Public participation spectrum [Internet]. Toowong, Queensland: International Association for Public Participation; 2019 [cited 2021 May 22]. Available from: https://www.iap2.org.au/resources/spectrum/.

- Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Participation toolkit [Internet]. Glasgow, Scotland: Healthcare Improvement Scotland; 2020 [cited 2021 June 1]. Available from: https://www.hisengage.scot/toolkit.aspx.

- Kovacs Burns K, Bellows M, Eigenseher C, Gallivan J. ‘Practical’ resources to support patient and family engagement in healthcare decisions: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:e1–e15.

- Consumer and Community Involvement Program. Training [Internet]. Nedlands, Western Australia: Consumer and Community Involvement Program; 2020 [cited 2021 May 28]. Available from: https://cciprogram.org/resources/training/.

- Health Consumers Queensland. Recruiting: paying consumers [Internet]. Brisbane, Queensland: Health Consumers Queensland; 2020 [cited 2021 June 2]. Available from: https://www.hcq.org.au/home-2/paying-consumers/.

- Diabetes Australia. Take part [Internet]. Turner, Australian Capital Territory: Diabetes Australia; 2021 [cited 2021 May 30]. Available from: https://www.diabetesaustralia.com.au/contact-us/.

- The Lindsay Leg Club Foundation. Leg club volunteers [Internet]. Ipswich, England: The Lindsay Leg Club Foundation; 2021 [cited 2021 May 30]. Available from: https://www.legclub.org/support-us/volunteers.

- Consumer and Community Involvement Program. Researcher services [Internet]. Nedlands, Western Australia: Consumer and Community Involvement Program; 2020 [cited 2021 May 28]. Available from: https://cciprogram.org/researcher-services/.

- Health Consumers Queensland. Recruiting consumers [Internet]. Brisbane, Queensland: Health Consumers Queensland; 2020 [cited 2021 May 20]. Available from: https://www.hcq.org.au/home-2/recruiting-consumers/.

- Centre of Excellence on Partnership with Patients and the Public. Evaluation Toolkit [Internet]. Montreal, Canada: Centre of Excellence on Partnership with Patients and the Public; ND [cited 2021 May 27]. Available from: https://ceppp.ca/en/collaborations/evaluation-toolkit/.

- Kok M. Guidance document: evaluating public involvment in research [Internet]. Bristol, England: UWE Bristol; 2018 [cited 2021 May 30]. Available from: http://www.phwe.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Guidance-on-evaluating-Public-Involvement-in-research.pdf.

- Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ 2017;358:e1-e7.