Volume 43 Number 2

Healing peristomal wounds around retracted stomas with negative-pressure wound therapy: a case series

Jarosław Cwaliński, Jacek Hermann, Tomasz Banasiewicz

Keywords ostomy, Wound care, Negative-pressure wound therapy, hydrofiber dressing, peristomal infection, peristomal leak, retraction

For referencing Cwaliński J, Hermann J & Banasiewicz T. Healing peristomal wounds around retracted stomas with negative-pressure wound therapy: a case series. WCET® Journal 2023;43(2):29-34

DOI

https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.2.29-34

Submitted 16 February 2022

Accepted 29 April 2022

Abstract

One method for treating a retracted stoma is a vacuum dressing that cleans the wound and protects against intestinal leakage. This case series describes the use of an integrated, single-use negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) dressing to treat retracted stomas as an alternative to other noninvasive remedies. The report includes seven patients who were hospitalized in the authors’ surgical department from 2019 to 2020. All patients developed severe peristomal infection that failed to respond to local treatment with proper ostomy appliances or specialist dressings. After cleaning each wound and removing necrotic lesions, the authors applied a single-use hydrofiber NPWT dressing to each patient. The dressing was changed every 2 to 5 days, depending on the effects of the therapy. The stoma orifice was covered with a bag with two-piece ostomy systems. The peristomal wound healed in all cases and leakage was eliminated. The mean time of treatment was 14 days (range, 10-21 days), and the vacuum dressings were changed an average of four times (range, 3-7). None of the patients required a stoma translocation or other additional surgery. Three patients received systemic IV antibiotic therapy to treat general infection. Single-use NPWT dressings protect peristomal wounds from bowel leakage and do not hinder the application of stoma bags. This system, similar to standard NPWT devices, effectively protects infected stomas from retraction.

Introduction

An ostomy is a communication between the lumen of a bowel loop and the abdominal wall; stoma creation is one of the most basic procedures of colorectal surgery. It is performed on the large or small bowel to treat malignant, inflammatory, or vascular diseases and following bowel injuries. Colorectal cancer is the most common indication, comprising up to 75% of cases.1,2 Ostomies are performed for almost 100,000 patients per year in the US, and the procedure reduces major morbidity and mortality.3

However, there is a relatively high rate of ostomy-related morbidity. The early complications, such as peristomal infection, skin irritation, ischemia, and retraction continue to challenge surgeons.2 Ostomy retraction causes continuous leakage of bowel contents into the subcutaneous tissue; this can be followed by severe necrosis and infection of the tissues surrounding the ostomy, with ostomy detachment occurring in some cases.4,5 Although most of the aforementioned complications are treated with proper ostomy appliances and specialist dressings, severe complications can require advanced modalities such as negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT), which offers effective, continuous evacuation of infectious effusion and pus. However, although ostomy salvage using standard NPWT devices has been described, to the authors’ knowledge there are no extant reports about single-use NPWT systems. Accordingly, this case series described the treatment of peristomal wounds and stoma retraction prevention with integrated single-use vacuum dressings.

Methods

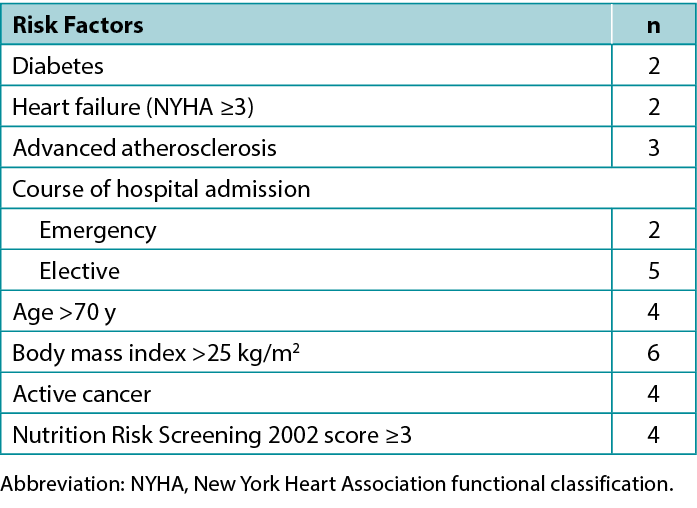

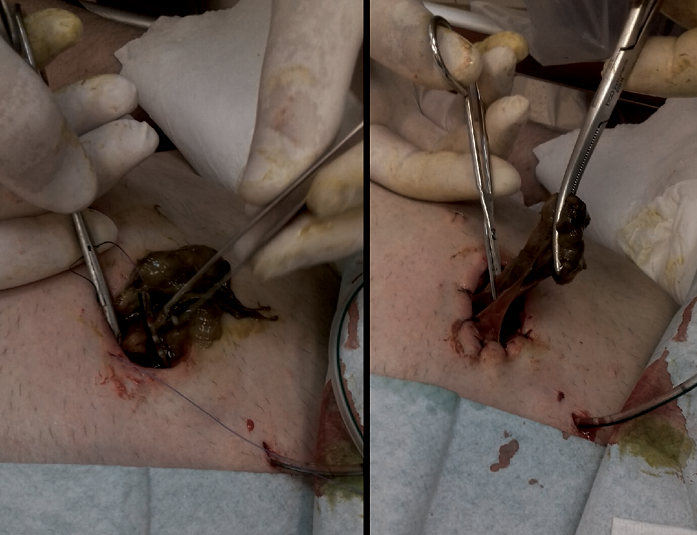

A preliminary and prospective study was carried out from 2019 to 2020 on a group of seven patients with early retracted ostomy and peristomal wounds. The series included four men and three women whose characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics (N = 7)

All of the patients had a moderate or severe peristomal infection that failed to respond to local treatment with proper ostomy appliances and specialist dressings. In addition, preoperative risk factors for healing dysfunction were observed in the study group, including emergency surgery, malnutrition, steroid use, active inflammatory bowel disease, and other comorbidities (Table 2). All patients received oral immunomodulatory nutrition beginning the second day after surgery, and four of the patients were also fed intravenously during the four postoperative days. Further, three patients required systemic antibiotic therapy due to septic complications.

Table 2. Preoperative risk factors for surgical site infection

Ethics and Consent

Negative-pressure wound therapy is widely approved for medical therapy and the aim of the study was to adapt this method to the treatment of stoma-related complications. Therefore, the ethics committee of the author’s institution concluded that there was no need to issue a separate consent for this study. However, due to this atypical application of single-use NPWT, the authors obtained informed consent for the therapy from each patient, as well as written approval to publish images and case details.

Surgical Technique

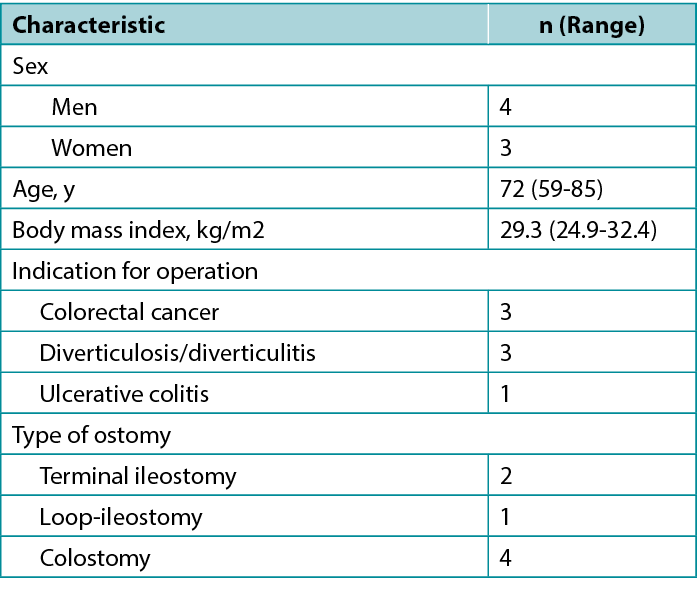

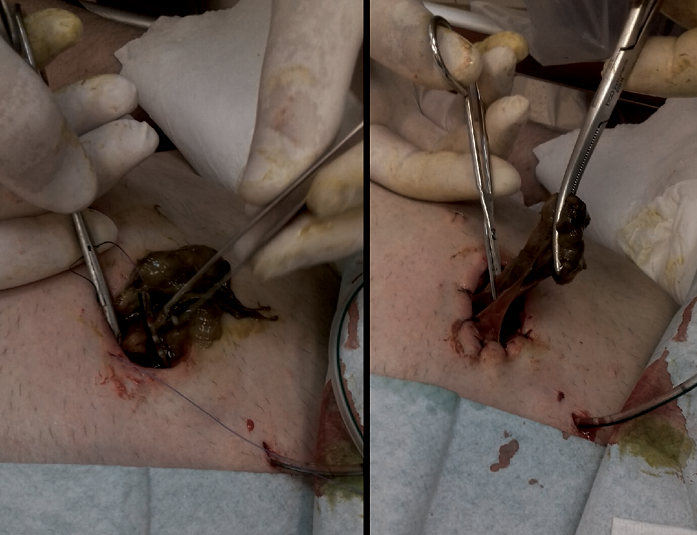

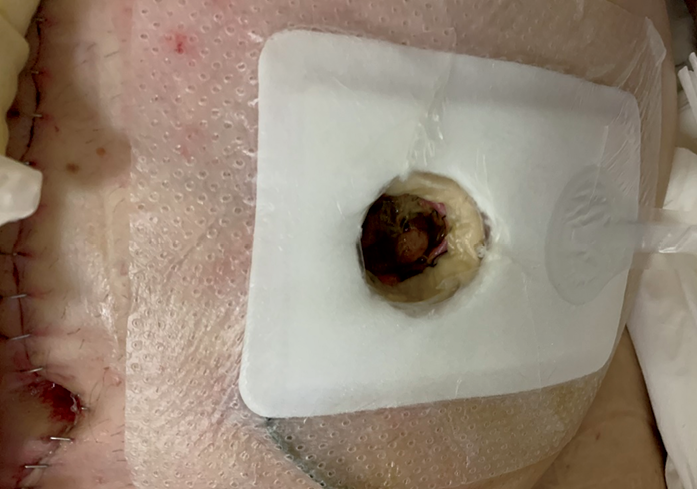

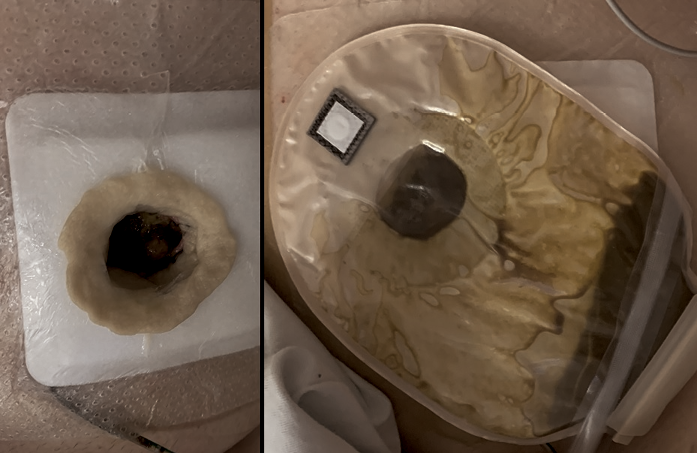

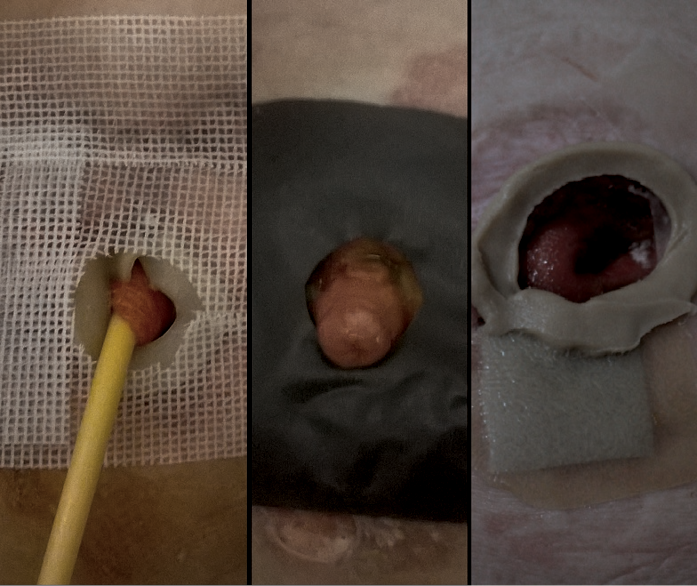

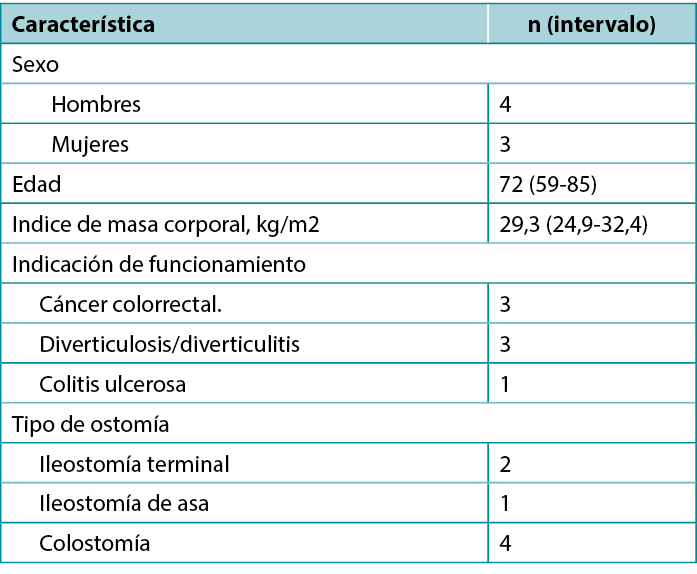

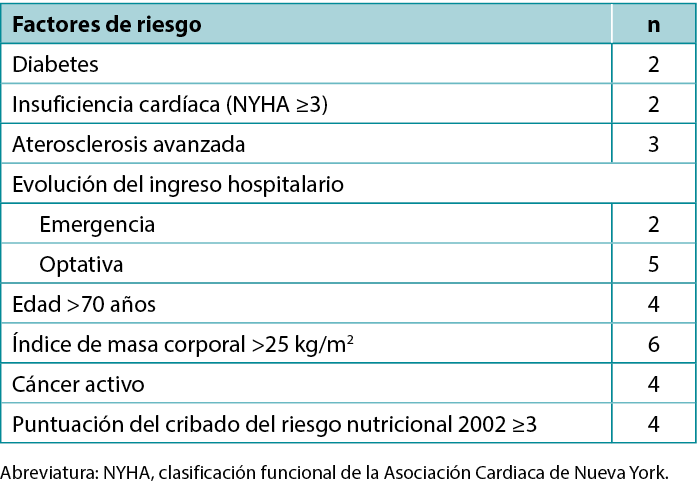

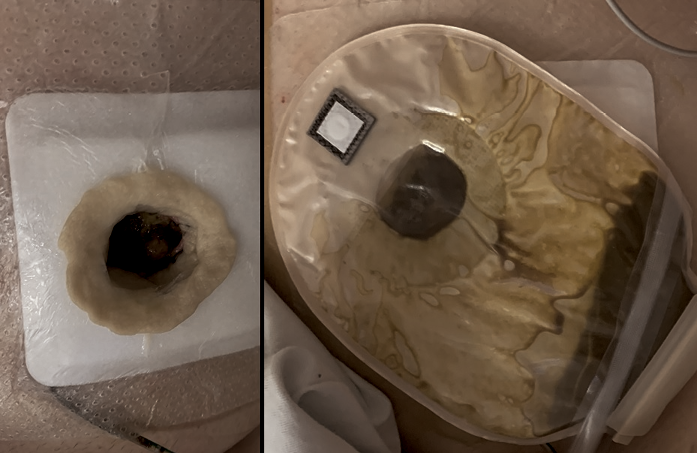

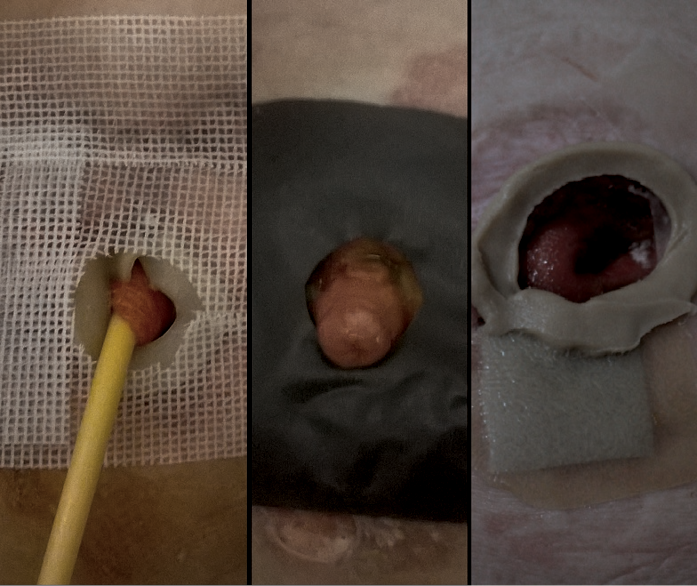

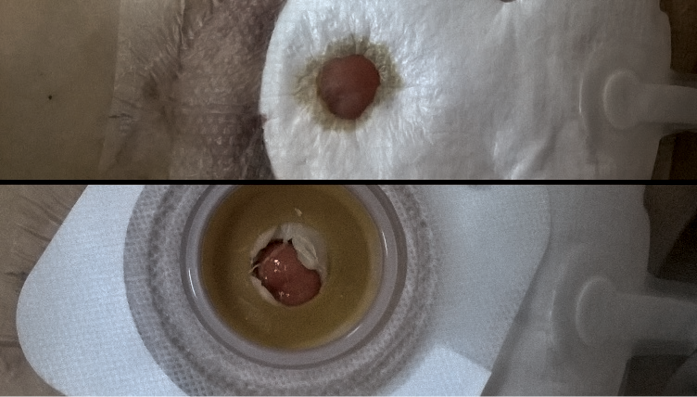

First, the authors debrided the infected wound surrounding the retracted ostomy and, if necessary, placed a drain derived from a separate cut given any persistent leakage of the bowel contents into the surgical site (Figure 1). Next, they washed the wound and surrounding skin with disinfectant and applied a carboxymethylated cellulose fiber dressing measuring 15 × 10 cm or 10 × 10 cm (Avelle NPWT System, ConvaTec; or PICO NPWT System, Smith & Nephew; Figure 2). A hole was cut in the dressing to fit the ostomy as well as the wound. The adherence and tightness of the dressings were enhanced with adhesive foil strips placed on the margins (Figure 2). In the next step, a hydrocolloid stoma paste was applied to increase adhesion of the ostomy bag or plate edges (Figure 3). The stoma paste also used to improve the system seal and create a barrier between the stoma contents and the hydrofiber filling of the NPWT dressing. In addition, deep peristomal wound recesses with residual necrosis were filled with silver alginate dressing or silicone open-weave gauze (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Stabilization of retracted ostomy with necrectomy and bowel-to-skin sutures

Figure 2. Peristomal wound after single-use negative pressure wound therapy dressing application

Figure 3. Ostomy bag application during the treatment of a retracted stoma with a negative-pressure wound therapy dressing

Stoma paste fills the space between the edge of the tissues and the dressing (left) ensuring better adhesion of the pouch and protecting against leakage (right)

Figure 4.Peristomal wound with silver alginate dressing or silicone open-weave gauze

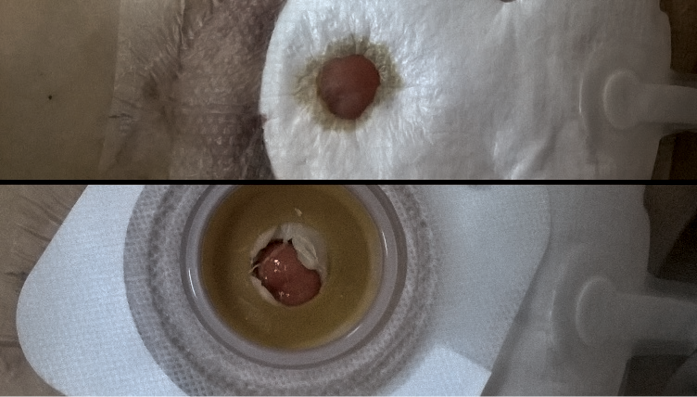

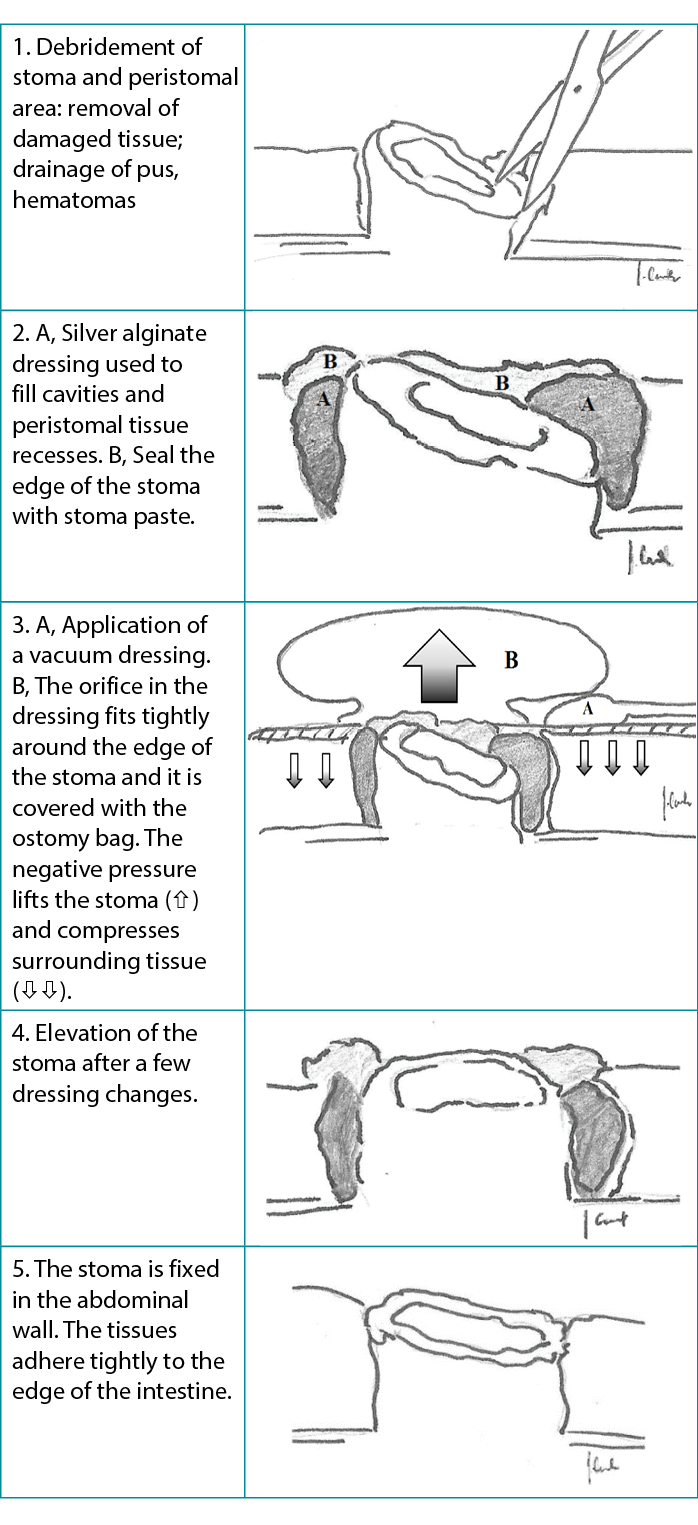

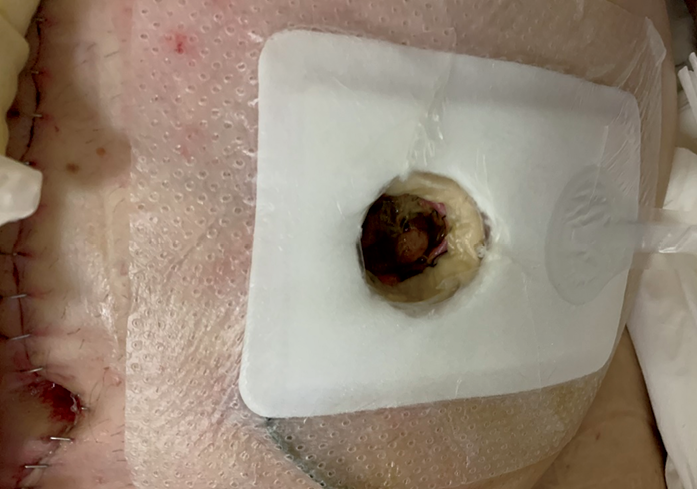

Finally, the port of a negative-pressure generator was attached to the dressing and a stable negative pressure of 80 mm Hg was maintained during the therapy. At each dressing change, any bowel leakage into the wound was controlled and eliminated as needed (Figure 5). The dressings were changed at the beginning of every second day with the use of a one-piece stoma bag. Subsequently, dressings were left in place for 3 to 5 days using two-piece ostomy systems (Figure 6). A summary diagram of the procedure is presented in the Table 3.

Figure 5. Ostomy on day 4 of treatment after second change of vacuum drainage with no bowel contents leakage

Figure 6. One-piece bag applied to ostomy

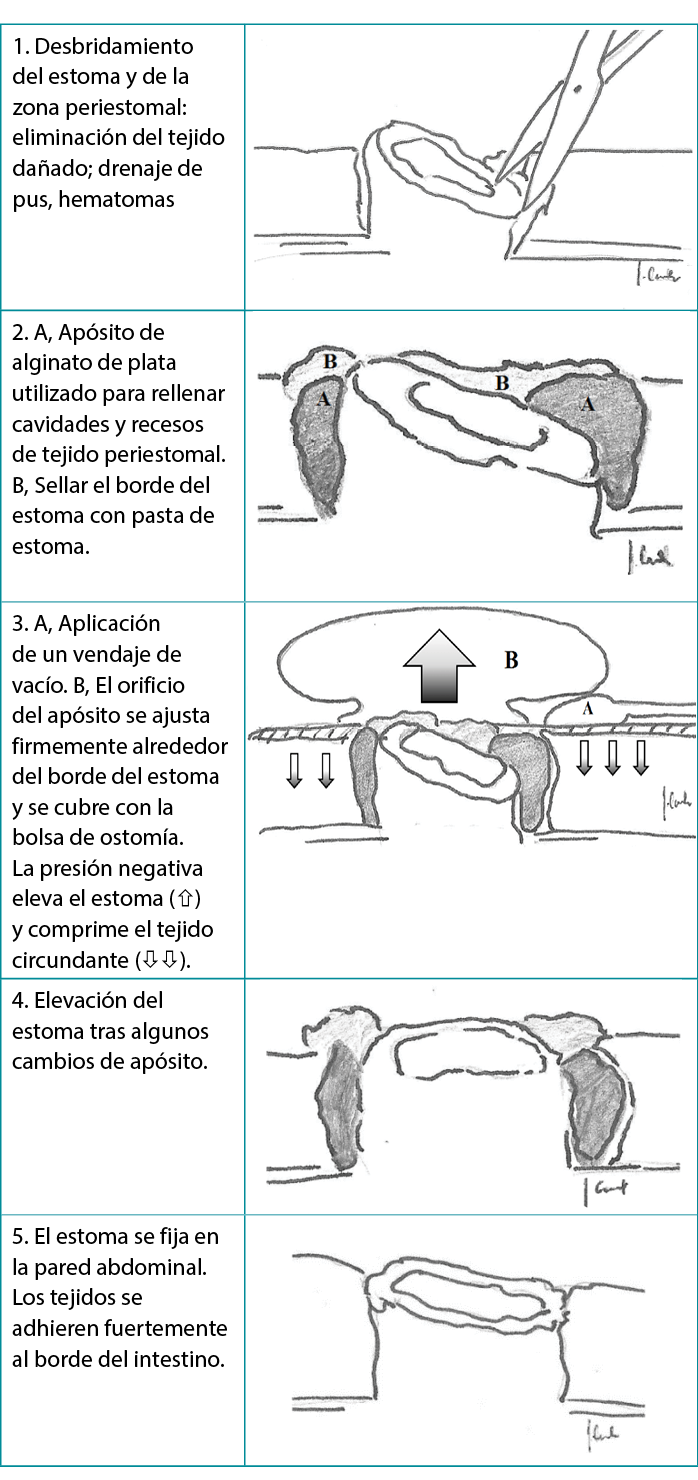

Table 3. Stoma healing: single-use negative-pressure wound therapy dressing removes necrotic tissue and prevents stoma erosion

Results

Patients’ deep, infected peristomal wounds healed and the ostomies were retained in their primary locations. None of the patients required secondary operations. The mean time of treatment was 14 days (range, 10-21 days), and the NPWT was changed an average of four times (range, 3-7). Figure 7 shows a representative treatment effect after four dressing changes. Regular ostomy appliances were used in six patients with terminal ostomy; additional sealing rings were necessary in one patient with loop ostomy. Two patients, one with colostomy and one with ileostomy, received appropriate systemic antibiotic therapy because of elevated inflammatory markers in the serum.

Figure 7. Effect on day 10 of treatment and after four dressing changes

Discussion

The incidence of overall stoma-related complications is reported to be between 10% and 70%.6,7 Hematoma formation, bleeding, ostomy edema, skin irritation with erosion or ulceration, ischemia with necrosis, and early ostomy retraction are the most common complications to occur within 30 days of any procedure, with frequencies ranging from 25% to 34%.1 Although most of these complications resolve spontaneously within a few days or require only conservative medical treatment, patients who develop major complications such as ischemia with necrosis or ostomy retraction usually require secondary surgery because of the threat of severe infection and gastrointestinal tract dysfunction.1,8 Proper surgical technique—displacing the bowel with no tension to the skin surface and suturing it to the pre-planned place—is the most effective way to prevent patients from experiencing complications.

Before elective procedures, a stoma nurse should prepare the location of the stoma, assessing the location of skin folds and scars and considering the patient’s lifestyle and occupation. Typically, the stoma site is designated in standing, lying, and sitting positions. The stoma nurse should also mark an alternative site in case of intraoperative difficulties.9

According to the surgical technique, the stoma should be positioned through the rectus abdominis muscle leaving sufficient gut margin above the skin surface. For an end ostomy, it should be 5 cm for the small intestine and 2 cm for the colon, which allows the stoma to contract to about 2 cm and 0.5 cm after a few months.10 Lack of proper pre-operative preparation may occur in emergency operations, where the rate of morbidity is increasing.11,12

A refractory ostomy may be cause for reoperation, which, in some cases, then increases the risk of additional complications. Avoiding reoperation is extremely important for some patient populations in particular, such as those with cachexia and/or cancer, for whom surgical site infections or other complications may prolong the length of stay and affect chemotherapy. In addition, avoiding reoperation enables the patient to maintain oral nutrition which improves nutrient absorption and the condition of the gut microbiome.12,13

Preventing the continuous leakage of bowel contents into peristomal subcutaneous tissue and enabling the unhindered outflow of bowel contents through the ostomy are the basic therapeutic targets in cases with ostomy complications.11,14 Those targets are met initially with modified stoma appliances in the form of rings, washers, and feet with a concave profile, the aims of which are shape adaptation and leveling the height of the ostomy.15 Vacuum-assisted therapy is recommended as an effective method to treat patients with severely retracted ostomy. Vacuum-assisted dressings consist of a polyurethane foam covered with adhesive foil. A stationary or portable electrical suction pump is attached to the dressing and a stable negative pressure of 50 to 200 mm Hg is maintained during therapy. The objectives of vacuum treatment are to remove tissue exudate, divert bowel contents, reduce edema, and improve blood supply.16,17 The polyurethane foam also removes devitalized and infected tissues and improves lymphatic drainage. Thus, after a few dressing changes, the wound contracts and it is covered with fresh granulation tissue.16,18 The antibacterial mode of action, mostly against Gram-negative bacteria, relies on direct elimination of bacterial cells, followed by local regulation of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic conditions, the effect of which is better antibiotic tissue penetration.19,20

Proper application of vacuum dressings on peristomal wounds with a retracted bowel remnant is challenging because bowel contents can be suctioned into a stoma bag through badly adherent layers of the dressing. It is a priority to isolate the stoma from the wound without secondary tissue damage caused by the vacuum dressing. Therefore, it is absolutely necessary to place an insulating layer between the intestine and the polyurethane foam and use an under pressure between 75 mm Hg and 125 mm Hg.21,22 Close vicinity of the suction port and stoma bag is another drawback of the application. Finally, a patient’s daily life activities may be limited by needing to carry a stationary or portable negative pressure electrical suction pump.23,24 Another important issue remains the long-term outpatient and home-based care with properly selected equipment and qualified personnel. Nurses caring for wounds can successfully carry out vacuum therapy after a few weeks of practical training.25

Applying single-use NPWT dressings can help avoid the aforementioned obstacles. Because single-use NPWT dressings are much thinner than regular polyurethane foam and all the layers (separating, absorbent, and insulating) are integrated into one pack, the dressing thoroughly fills the wound and properly adheres to the ostomy margins. Moreover, this type of vacuum therapy may be left in the wound for up to 7 days, on the condition that it retains its full capacity to absorb exudates. Typically, a portable pump included in the set generates a stable pressure of approximately 80 mm Hg as the surface of a wound decreases and the retracted ostomy is elevated.27,28 Because this system is lightweight, has a silent pump, and requires simple battery changes, it is accepted by patients in both ambulatory settings and at home. In the authors’ experience, telemedicine (eg, iWound; Polmedi) improves the safety of NPWT use in patients’ continued treatment at home.

Conclusions

The use of single-use NPWT dressings combined with properly balanced nutrition and antibiotic therapy is an effective method of treatment for patients with early stoma complications. Single-use NPWT systems are “skin-friendly,” because they do not damage the skin surrounding the ostomy and simultaneously heal the area affected by inflammation or infection. They are inexpensive and easy to use, even in home settings. The authors recommend this treatment method for the management of an early phase retracted ostomy with concomitant peristomal infection.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Curación de heridas periestomales alrededor de estomas retraídos con terapia de presión negativa para heridas: serie de casos

Jarosław Cwaliński, Jacek Hermann, Tomasz Banasiewicz

DOI: https://doi.org/10.33235/wcet.43.2.29-34

Resumen

Un método para tratar un estoma retraído es un apósito de vacío que limpia la herida y protege contra las fugas intestinales. Esta serie de casos describe el uso de un apósito integrado de un solo uso para terapia de presión negativa para heridas (NPWT) para tratar estomas retraídos como alternativa a otros remedios no invasivos. El informe incluye siete pacientes que fueron hospitalizados en el departamento quirúrgico de los autores entre 2019 y 2020. Todos los pacientes desarrollaron una infección periestomal grave que no respondió al tratamiento local con dispositivos de ostomía adecuados o apósitos especializados. Tras limpiar cada herida y eliminar las lesiones necróticas, los autores aplicaron a cada paciente un apósito NPWT de hidrofibra de un solo uso. El apósito se cambiaba cada 2 a 5 días, dependiendo de los efectos de la terapia. El orificio del estoma se cubrió con una bolsa con sistemas de ostomía de dos piezas. La herida periestomal cicatrizó en todos los casos y se eliminaron las fugas. La duración media del tratamiento fue de 14 días (intervalo, 10-21 días), y los apósitos de vacío se cambiaron una media de cuatro veces (intervalo, 3-7). Ninguno de los pacientes requirió una translocación de estoma u otra cirugía adicional. Tres pacientes recibieron terapia antibiótica sistémica IV para tratar la infección general. Los apósitos NPWT de un solo uso protegen las heridas periestomales de las fugas intestinales y no dificultan la aplicación de bolsas de estoma. Este sistema, similar a los dispositivos NPWT estándar, protege eficazmente los estomas infectados de la retracción.

Introducción

Una ostomía es una comunicación entre el lumen de un asa intestinal y la pared abdominal; la creación de un estoma es uno de los procedimientos más básicos de la cirugía colorrectal. Se realiza en el intestino grueso o delgado para tratar enfermedades malignas, inflamatorias o vasculares y tras lesiones intestinales. El cáncer colorrectal es la indicación más frecuente, con hasta un 75% de los casos.1,2 En EE. UU. se realizan ostomías a casi 100.000 pacientes al año, y el procedimiento reduce la morbilidad y la mortalidad importantes.3

Sin embargo, existe una tasa relativamente alta de morbilidad relacionada con la ostomía. Las complicaciones tempranas, como la infección periestomal, la irritación cutánea, la isquemia y la retracción, siguen siendo un reto para los cirujanos.2 La retracción de la ostomía provoca una fuga continua del contenido intestinal hacia el tejido subcutáneo; esto puede ir seguido de necrosis grave e infección de los tejidos que rodean la ostomía, con desprendimiento de la ostomía en algunos casos.4,5 Aunque la mayoría de las complicaciones mencionadas se tratan con dispositivos de ostomía adecuados y apósitos especializados, las complicaciones graves pueden requerir modalidades avanzadas como la terapia de presión negativa para heridas (NPWT), que ofrece una evacuación eficaz y continua del derrame infeccioso y el pus. Sin embargo, aunque se ha descrito la salvación de ostomías mediante dispositivos de NPWT estándar, hasta donde saben los autores no existen informes sobre sistemas de NPWT de un solo uso. En consecuencia, esta serie de casos describe el tratamiento de las heridas periestomales y la prevención de la retracción del estoma con apósitos de vacío integrados de un solo uso.

Métodos

Entre 2019 y 2020 se llevó a cabo un estudio preliminar y prospectivo en un grupo de siete pacientes con ostomía retraída temprana y heridas periestomales. La serie incluía a cuatro hombres y tres mujeres cuyas características se presentan en la Tabla 1.

Tabla 1. Características de los pacientes (N=7)

Todos los pacientes presentaban una infección periestomal moderada o grave que no respondía al tratamiento local con dispositivos de ostomía adecuados y apósitos especializados. Además, en el grupo de estudio se observaron factores de riesgo preoperatorios de disfunción de la cicatrización, como cirugía de urgencia, desnutrición, uso de esteroides, enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal activa y otras comorbilidades (Tabla 2). Todos los pacientes recibieron nutrición inmunomoduladora oral a partir del segundo día tras la cirugía, y cuatro de los pacientes también fueron alimentados por vía intravenosa durante los cuatro días postoperatorios. Además, tres pacientes precisaron tratamiento antibiótico sistémico debido a complicaciones sépticas.

Tabla 2. Factores de riesgo preoperatorios de infección del sitio quirúrgico

Ética y consentimiento

La terapia de presión negativa para heridas está ampliamente aprobada para el tratamiento médico y el objetivo del estudio era adaptar este método al tratamiento de las complicaciones relacionadas con el estoma. Por lo tanto, el comité de ética de la institución del autor concluyó que no era necesario emitir un consentimiento por separado para este estudio. Sin embargo, debido a esta aplicación atípica de la NPWT de un solo uso, los autores obtuvieron el consentimiento informado para la terapia de cada paciente, así como la aprobación por escrito para publicar imágenes y detalles de los casos.

Técnica quirúrgica

En primer lugar, los autores desbridaron la herida infectada que rodeaba la ostomía retraída y, en caso necesario, colocaron un drenaje derivado de un corte separado dada cualquier fuga persistente del contenido intestinal en el lecho quirúrgico (Figura 1). A continuación, lavaron la herida y la piel circundante con desinfectante y aplicaron un apósito de fibra de celulosa carboximetilada de 15 × 10 cm o 10 × 10 cm (Sistema Avelle NPWT , ConvaTec; o PICO NPWT, Smith & Nephew; Figura 2). Se hizo un orificio en el apósito para ajustarlo a la ostomía y a la herida. La adherencia y la estanqueidad de los apósitos se mejoraron con tiras de lámina adhesiva colocadas en los márgenes (Figura 2). En el siguiente paso, se aplicó una pasta de estoma hidrocoloide para aumentar la adherencia de los bordes de la bolsa o placa de ostomía (Figura 3). La pasta del estoma también se utiliza para mejorar el sellado del sistema y crear una barrera entre el contenido del estoma y el relleno de hidrofibra del apósito NPWT. Además, los recesos periestomales profundos de la herida con necrosis residual se rellenaron con apósito de alginato de plata o gasa de tejido abierto de silicona (Figura 4).

Figura 1. Estabilización de la ostomía retraída con necrectomía y suturas intestino-piel

Figura 2. Herida periestomal tras la aplicación de un apósito de terapia de presión negativa para heridas de un solo uso

Figura 3. Aplicación de una bolsa de ostomía durante el tratamiento de un estoma retraído con un apósito de terapia de presión negativa para heridas

La pasta para estomas rellena el espacio entre el borde de los tejidos y el apósito (izquierda) asegurando una mejor adherencia de la bolsa y protegiendo contra las fugas (derecha)

Figura 4. Herida periestomal con apósito de alginato de plata o gasa de tejido abierto de silicona

Por último, se conectó el puerto de un generador de presión negativa al apósito y se mantuvo una presión negativa estable de 80 mm Hg durante la terapia. En cada cambio de apósito, se controlaba y eliminaba cualquier fuga intestinal en la herida según fuera necesario (Figura 5). Los apósitos se cambiaban al principio de cada dos días con el uso de una bolsa de estoma de una pieza. Posteriormente, los apósitos se dejaron colocados de 3 a 5 días utilizando sistemas de ostomía de dos piezas (Figura 6). En el Cuadro 3 se presenta un diagrama resumido del procedimiento.

Figura 5. Ostomía el día 4 de tratamiento después del segundo cambio de drenaje de vacío sin fuga de contenido intestinal

Figura 6. Bolsa de una pieza aplicada a la ostomía

Tabla 3. Cicatrización del estoma: el apósito terapéutico de presión negativa de un solo uso elimina el tejido necrótico y evita la erosión del estoma

Resultados

Las heridas periestomales profundas e infectadas de los pacientes se curaron y las ostomías se mantuvieron en sus ubicaciones primarias. Ninguno de los pacientes requirió operaciones secundarias. La duración media del tratamiento fue de 14 días (intervalo, 10-21 días), y la NPWT se cambió una media de cuatro veces (intervalo, 3-7). La figura 7 muestra un efecto representativo del tratamiento tras cuatro cambios de apósito. Se utilizaron aparatos de ostomía normales en seis pacientes con ostomía terminal; fueron necesarios anillos de sellado adicionales en un paciente con ostomía en asa. Dos pacientes, uno con colostomía y otro con ileostomía, recibieron tratamiento antibiótico sistémico adecuado debido a la elevación de los marcadores inflamatorios en el suero.

Figura 7. Efecto en el día 10 de tratamiento y tras cuatro cambios de apósito

Discusion

La incidencia de complicaciones generales relacionadas con el estoma oscila entre el 10% y el 70%.6,7 La formación de hematomas, las hemorragias, el edema de ostomía, la irritación cutánea con erosión o ulceración, la isquemia con necrosis y la retracción precoz de la ostomía son las complicaciones más frecuentes en los 30 días posteriores a cualquier intervención, con frecuencias que oscilan entre el 25% y el 34%.1 Aunque la mayoría de estas complicaciones se resuelven espontáneamente en unos pocos días o sólo requieren tratamiento médico conservador, los pacientes que desarrollan complicaciones importantes como isquemia con necrosis o retracción de la ostomía suelen requerir cirugía secundaria debido a la amenaza de infección grave y disfunción del tracto gastrointestinal.1,8 Una técnica quirúrgica adecuada -colocar el intestino sin tensión en la superficie de la piel y suturarlo en el lugar previsto- es la forma más eficaz de evitar que los pacientes sufran complicaciones.

Antes de los procedimientos electivos, una enfermera especializada en estomas debe preparar la ubicación del estoma, evaluando la localización de los pliegues cutáneos y las cicatrices y teniendo en cuenta el estilo de vida y la ocupación del paciente. Normalmente, el lugar del estoma se designa en las posiciones de pie, tumbado y sentado. La enfermera especializada en estomas también debe marcar un lugar alternativo en caso de dificultades intraoperatorias.9

De acuerdo con la técnica quirúrgica, el estoma debe colocarse a través del músculo recto abdominal dejando un margen intestinal suficiente por encima de la superficie cutánea. Para una ostomía terminal, debe ser de 5 cm para el intestino delgado y de 2 cm para el colon, lo que permite que el estoma se contraiga hasta unos 2 cm y 0,5 cm al cabo de unos meses.10 La falta de una preparación preoperatoria adecuada puede darse en operaciones de urgencia, en las que la tasa de morbilidad está aumentando.11,12

Una ostomía refractaria puede ser motivo de reintervención, lo que, en algunos casos, aumenta el riesgo de complicaciones adicionales. Evitar la reintervención es extremadamente importante para algunas poblaciones de pacientes en particular, como los que padecen caquexia y/o cáncer, para los que las infecciones del lecho quirúrgico u otras complicaciones pueden prolongar la estancia y afectar a la quimioterapia. Además, evitar la reintervención permite al paciente mantener la nutrición oral, lo que mejora la absorción de nutrientes y el estado del microbioma intestinal.12,13

Evitar la fuga continua del contenido intestinal al tejido subcutáneo periestomal y permitir la salida sin obstáculos del contenido intestinal a través de la ostomía son los objetivos terapéuticos básicos en los casos con complicaciones de ostomía.11,14 Estos objetivos se alcanzan inicialmente con dispositivos de estoma modificados en forma de anillos, arandelas y pies con un perfil cóncavo, cuyos objetivos son la adaptación de la forma y la nivelación de la altura de la ostomía.15 Se recomienda la terapia asistida por vacío como método eficaz para tratar a los pacientes con ostomía gravemente retraída. Los apósitos asistidos por vacío consisten en una espuma de poliuretano recubierta de una lámina adhesiva. Se acopla al apósito una bomba de succión eléctrica fija o portátil y se mantiene una presión negativa estable de 50 a 200 mm Hg durante la terapia. Los objetivos del tratamiento con vacío son eliminar el exudado tisular, desviar el contenido intestinal, reducir el edema y mejorar el riego sanguíneo.16,17 La espuma de poliuretano también elimina los tejidos desvitalizados e infectados y mejora el drenaje linfático. Así, tras unos pocos cambios de apósito, la herida se contrae y se cubre con tejido de granulación fresco.16, 18 El modo de acción antibacteriano, principalmente contra bacterias Gram-negativas, se basa en la eliminación directa de las células bacterianas, seguida de la regulación local de las condiciones farmacodinámicas y farmacocinéticas, cuyo efecto es una mejor penetración del antibiótico en el tejido.19,20

La aplicación correcta de apósitos de vacío en heridas periestomales con un remanente intestinal retraído supone un reto, ya que el contenido intestinal puede succionarse hacia una bolsa de estoma a través de las capas mal adheridas del apósito. Es prioritario aislar el estoma de la herida sin que se produzcan daños tisulares secundarios causados por el vendaje de vacío. Por lo tanto, es absolutamente necesario colocar una capa aislante entre el intestino y la espuma de poliuretano y utilizar una subpresión de entre 75 mm Hg y 125 mm Hg.21,22 La proximidad del puerto de succión y la bolsa del estoma es otro inconveniente de la aplicación. Por último, las actividades de la vida diaria del paciente pueden verse limitadas por la necesidad de transportar una bomba de aspiración eléctrica de presión negativa estacionaria o portátil.23, 24 Otra cuestión importante sigue siendo la atención ambulatoria y domiciliaria a largo plazo con equipos adecuadamente seleccionados y personal cualificado. Las enfermeras que atienden heridas pueden llevar a cabo con éxito la terapia de vacío tras unas semanas de formación práctica.25

La aplicación de apósitos NPWT de un solo uso puede ayudar a evitar los obstáculos mencionados. Como los apósitos NPWT de un solo uso son mucho más finos que la espuma de poliuretano normal y todas las capas (separadora, absorbente y aislante) están integradas en un solo paquete, el apósito rellena completamente la herida y se adhiere correctamente a los márgenes de la ostomía. Además, este tipo de terapia de vacío puede dejarse en la herida hasta 7 días, a condición de que conserve toda su capacidad de absorción de exudados. Normalmente, una bomba portátil incluida en el set genera una presión estable de aproximadamente 80 mm Hg a medida que disminuye la superficie de una herida y se eleva la ostomía retraída.27, 28 Dado que este sistema es ligero, tiene una bomba silenciosa y requiere cambios sencillos de batería, es aceptado por los pacientes tanto en entornos ambulatorios como en casa. Según la experiencia de los autores, la telemedicina (p. ej., iWound; Polmedi) mejora la seguridad del uso de la NPWT en el tratamiento continuado de los pacientes en su domicilio.

Conclusiones

El uso de apósitos NPWT de un solo uso combinados con una nutrición equilibrada y una terapia antibiótica es un método eficaz de tratamiento para los pacientes con complicaciones tempranas del estoma. Los sistemas NPWT de un solo uso son "respetuosos con la piel", ya que no dañan la piel que rodea la ostomía y, al mismo tiempo, curan la zona afectada por la inflamación o la infección. Son baratos y fáciles de usar, incluso en casa. Los autores recomiendan este método de tratamiento para el manejo de una ostomía retraída en fase temprana con infección periestomal concomitante.

Conflicto de intereses

Los autores declaran no tener conflictos de intereses.

Financiación

Los autores no recibieron financiación por este estudio.

Author(s)

Jarosław Cwaliński*

MD, PhD

Jacek Hermann

MD, PhD

Tomasz Banasiewicz

MD, PhD

* Corresponding author

In the Department of General, Endocrinological Surgery and Gastroenterological Oncology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poland, Jaroslaw Cwalinski, MD, PhD and Jacek Hermann, MD, PhD are Senior Assistants and Tomasz Banasiewicz, MD, PhD, is Professor and Head of Clinic.

References

- Ambe PC, Kurz NR, Nitschke C, Odeh SF, Möslein G, Zirngibl H. Intestinal ostomy. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2018; 16;115(11):182-7.

- Malik T, Lee MJ, Harikrishnan AB. The incidence of stoma related morbidity - a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2018;100(7):501-8.

- Goldberg M, Aukett LK, Carmel J, et al. Management of the patient with a fecal ostomy: best practice guideline for clinicians. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2010;37:596–8.

- Kann BR. Early stomal complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2008;21(1):23-30.

- Duchesne JC, Wang Y, Weintraub SL, Boyle M, Hunt JP. Stoma complications: a multivariate analysis. Am Surg 2002;68:961–6.

- Robertson I, Leung E, Hughes D, et al. Prospective analysis of stoma-related complications. Colorectal Dis 2005;7(3):279-85.

- Sheetz KH, Waits SA, Krell RW, et al. Complication rates of ostomy surgery are high and vary significantly between hospitals. Dis Colon Rectum 2014;57(5):632-7.

- Beraldo S, Titley G, Allan A. Use of w-plasty in stenotic stoma: a new solution for an old problem. Colorectal Dis 2006;8:715–6.

- Whitehead A, Cataldo PA. Technical considerations in stoma creation. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2017;30(3):162-71.

- WOCN Society, AUA, and ASCRS Position Statement on Preoperative Stoma Site Marking for Patients Undergoing Ostomy Surgery. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2021;48(6):533-6.

- Bass EM, Del Pino A, Tan A, Pearl RK, Orsay CP, Abcarian H. Does preoperative stoma marking and education by the enterostomal therapist affect outcome? Dis Colon Rectum 1997;40:440–2.

- Park JJ, Del Pino A, Orsay CP, et al. Stoma complications: the Cook County Hospital experience. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42(12):1575-80.

- Shellito PC. Complications of abdominal stoma surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41(12):1562-72.

- Kwiatt M, Kawata M. Avoidance and management of stomal complications. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2013;26(2):112-21.

- LeBlanc K, Whiteley I, McNichol L, Salvadalena G, Gray M. Peristomal medical adhesive-related skin injury: results of an international consensus meeting. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2019;46(2):125-136.

- Cwaliński J, Paszkowski J, Banasiewicz T. New perspectives in the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds. NPWTJ 2018;5(4):10-2.

- Banasiewicz T, Borejsza-Wysocki M, Meissner W, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy in patients with large postoperative wounds complicated by multiple fistulas. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2011;6(3):155–63.

- Hasan MY, Teo R, Nather A. Negative-pressure wound therapy for management of diabetic foot wounds: a review of the mechanism of action, clinical applications, and recent developments. Diabet Foot Ankle 2015;1,6:27618.

- Li T, Zhang L, Han LI, et al. Early application of negative pressure wound therapy to acute wounds contaminated with Staphylococcus aureus: an effective approach to preventing biofilm formation. Exp Ther Med 2016;11(3):769–76.

- Omar A, Wright JB, Schultz G, at al. Microbial biofilms and chronic wounds. Microorganisms 2017;5(1):9.

- Herrero Valiente L, García-Alcalá DG, Serrano Paz P, Rowan S. The challenges of managing a complex stoma with NPWT. J Wound Care 2012;21(3):120-3.

- Wright H, Kearney S, Zhou K, Woo K. Topical management of enterocutaneous and enteroatmospheric fistulas: a systematic review. Wound Manag Prev 2020;66(4):26-37.

- Herrero Valiente L, García-Alcalá DG, Serrano Paz P, Rowan S. The challenges of managing a complex stoma with NPWT. J Wound Care. 2012 Mar;21(3):120-3.

- Sun X, Wu S, Xie T, Zhang J. Combing a novel device and negative pressure wound therapy for managing the wound around a colostomy in the open abdomen: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(52):e9370.

- Mohamed E, Elmoniem AE, Elmowafi HM, Shebl AM. Effect of training program on performance of nurses caring for patient with negative pressure wound therapy. IOSR-JNHS 2019;8(1):31-5.

- Malmsjö M, Huddleston E, Martin R. Biological effects of a disposable, canisterless negative pressure wound therapy system. Eplasty 2014;2,14:e15.

- Ozkan B, Markal Ertas N, Bali U, Uysal CA. Clinical Experiences with Closed Incisional Negative Pressure Wound Treatment on Various Anatomic Locations. Cureus. 2020, 26;12(6):e8849.